U.S. President Donald Trump may have thought tariffs would push Canada toward greater integration with the U.S., but they have done the opposite. Canadians are avoiding American products, cancelling vacations and even selling their properties down south.

Some still hold out hope for negotiations with the Trump administration despite the continually changing goal posts, broken promises and threats to Canada’s sovereignty.

Others are convinced that Canada can win concessions by fighting back with counter-tariffs and other punitive measures despite the challenge of meaningfully affecting an economy more than 10 times the size of ours.

Canada may not be able to control what the U.S. does, but we can start to do the work needed to reduce the economic leverage the U.S. has over us. While buying Canadian can help, our internal market is not big enough to support our economy. Diversifying the countries we export to and the products we export will be critical.

This will not be easy. It will be particularly challenging for the people in the communities most affected by tariffs.

Governments can help these communities weather the short-term impacts while working to reorient local economies and, at the same time, build national resilience.

Canadians feel betrayed by a country that, for many of us, includes family members, friends and colleagues. Canada has signed multiple free trade agreements with the U.S. in good faith, allowing private companies on both sides of the border to pursue mutually beneficial transactions. The current situation also feels different from previous trade disputes, since President Trump is openly undermining our sovereignty.

Most Canadians do not want to be American and will do whatever it takes to defend our sovereignty.

Reducing the economic leverage the U.S. has over us will be critical. We have put most of our eggs in one basket with U.S. free trade, expecting our long-time ally to hold up its end of the bargain.

Since we can no longer count on the U.S., we need to find more eggs and more baskets. Even if the U.S. dropped its tariff threats tomorrow, our eyes will have been opened to the risks. Preserving Canada’s sovereignty means working with the private sector to reduce our dependence on the U.S.

But export diversification will be hard — like fighting against gravity. We live next door to the biggest economy in the world, and selling to the U.S. has been easy, convenient and lucrative.

In the short term, Canada’s economy could become smaller, and Canadians could have a lower standard of living. But in the medium to long term, changing both what we produce and who we produce it for could result in a stronger and more resilient economy – and country.

Canada sold $547 billion worth of goods to the U.S. in 2024 (see figure 1). That same year, we sold $173 billion to other countries. That means that 76 per cent of Canada’s goods exports went to the U.S. Rebalancing that equation so that the U.S.’s leverage is reduced is going to take a lot of work.

Figure 1. The baskets: 76 per cent of Canada’s goods exports went to the U.S. in 2024

Oil and gas, vehicles and auto parts make up our top exports to the U.S. (see figure 2). These exports account for a major share of Canada’s GDP and employment. In 2022, 74 per cent of oil and gas produced, and 54 per cent of transportation equipment manufactured in Canada went to the U.S.

Canada has already taken a major step toward exporting our oil and gas to other markets with the opening in 2024 of the expanded Trans Mountain oil pipeline, or TMX, that runs from Alberta to the West Coast and the Coastal GasLink pipeline that runs from northeast B.C. to the LNG Canada facility in Kitimat, which is set to begin shipping in 2025. However, the maximum capacity of TMX is only around 18 per cent of November 2024 Canadian crude oil production, with the potential to reach 23 per cent if changes are made, such as adding pump stations. There is also the possibility of building a northern leg of the TMX pipeline to ship oil to Kitimat, though there would likely still be fierce opposition to oil tankers in the Douglas Channel. The LNG Canada facility will have the capacity to process around 11 per cent of Canada’s natural gas production, and several other LNG facilities are planned that could dramatically increase Canada’s ability to export to non-U.S. markets.

Shifting auto manufacturing to non-U.S. markets is more challenging given the close integration of the Canadian and U.S. sectors. However, auto parts suppliers, such as Magna International, Linamar and Martinrea International, could potentially grow exports to other markets.

Figure 2. The eggs: Top 15 products Canada exported to the U.S. in 2024 and the corresponding imports of those products from the U.S. into Canada (CAD billions)

Selling Canada’s dominant sources of exports to other countries will not be enough to improve our resilience, as the oil, natural gas and auto sectors are also susceptible to global market disruption. For example, Canada could build multiple oil pipelines to its East and West Coasts only to face a decline in global oil demand as China, Europe and other countries move to electric transportation and clean energy. Electric vehicle battery technologies are also evolving, which could bring disruption to manufacturing plants focused on lithium-ion battery manufacturing. Resilience requires both diversifying whom Canada sells to and what it sells.

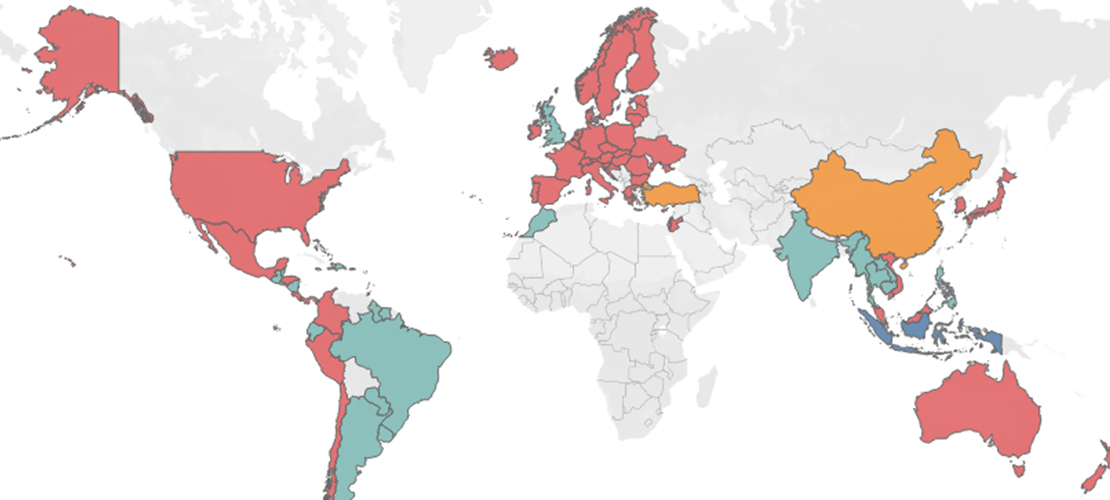

In looking at options for whom we sell to, a 2021 analysis by Export Development Canada provides some helpful insights. It identified substantial possible export opportunities for Canada, assuming that policy risks, free trade agreements and cultural proximity remain unchanged (which is obviously no longer the case). The total non-U.S. opportunities that Export Development Canada identified would add up to less than one-third of the value of current Canadian exports to the U.S. (see figure 3). Still, capturing those opportunities could double Canada’s exports to non-U.S. markets. But there are geopolitical considerations in non-U.S. markets as well, with China and India representing some of the largest opportunities.

There could be greater potential if Canada also diversifies and expands the goods we produce. Markets that have more growth certainty over the course of the century could be good bets. These include critical minerals, battery materials, agriculture and agri-food, uranium and potash.

Figure 3. Canadian export opportunities in 2030 for goods and services (USD billions)

Another good bet is that global defence spending will grow, including in Canada. Canadian companies could capture some of these opportunities, which often lead to civilian applications.

Technology is an additional area where there is room to better capture global market opportunities, including in clean technology, biotechnology and artificial intelligence.

And we should not forget about the potential for growth in service exports, where Canada has done a better job of diversification over the past decade.

Canada is the 10th largest economy in the world but ranks 37th in terms of population. We will not be able to maintain our standard of living without a significant focus on exports. That means that it is in our interest to champion unfettered, rules-based trade around the world. Trade agreements come with an understanding: each country benefits from a reduction in trade barriers and increased access to the others’ market. When Canadians are open to buying international goods, our market is more attractive for trade agreements. We do not want that to change.

For example, Canada is on the cusp of a comprehensive trade agreement with the European Union that offers enormous economic potential. With the agreement provisionally implemented in 2017, Canada’s exports to Europe increased by 31 per cent between 2016 and 2023. Our imports from Europe increased by 56 per cent over the same period. Ten European Union countries, including France and Italy, have yet to ratify the agreement. Strong Canadian demand for their products could help seal the deal.

When a country — such as the U.S. — threatens to violate existing trade agreements, it may be possible to benefit from a “buy Canadian” sentiment to shift consumption away from U.S. imports toward Canadian alternatives. It could be particularly helpful to Canadian companies that lose business from tariffs. The most significant impact would come from governments and large businesses shifting suppliers, but individual consumers can collectively have an impact too by shifting purchases of food, alcohol and household products.

Of course, it would be much easier to buy Canadian if we were to accelerate the reduction of interprovincial trade barriers. According to a 2019 International Monetary Fund report, Canada’s internal trade barriers are equivalent to a tariff of around 21 per cent. The Canadian Free Trade Agreement, launched in 2017, established several areas to tackle, including labour mobility, procurement, regulatory reconciliation and co-operation and trade in alcoholic beverages. There have been some notable successes, such as the agreement to harmonize energy efficiency requirements for appliances, but progress in other areas, such as alcoholic beverages, has been slow.

Following the threat of U.S. tariffs, Anita Anand, the federal minister responsible for internal trade, promised to accelerate the removal of internal trade barriers and recently announced the removal of almost half of the remaining federal exceptions to the internal trade agreement.

Buying Canadian can and will help, but we should not lose sight of the strategic importance of strong trade linkages with countries around the world.

IRPP research undertaken for our Community Transformations Project shows the importance of thinking not just about affected companies and their workers but also about communities.

Communities with a high concentration of employment in one sector can see significant impacts when a major employer suffers. There could be worker layoffs, cancelled contracts for suppliers and lower spending at local restaurants and businesses. Municipal governments can also struggle if tax revenues decline substantially, and non-profit service providers might see reduced donations at the same time as they experience an increase in demand for their services. Home prices can also drop, making it more difficult for families to afford to move.

The consequences for people in these communities are not just economic. Families can also face significant financial and mental stress.

This means that any plan to reorient Canada’s trade patterns needs to build in a range of community supports that cover economic, financial and social needs.

Rather than looking at the implications of specific tariff proposals, which are still in flux, we look at community susceptibility to U.S. tariffs using a similar approach to our analysis of susceptibility to the energy transition. We select sectors with significant exports to the U.S. and identify communities (or census divisions) with more than 5 per cent of their workforce employed in those sectors (see figure 4).

For example, communities with high concentrations of employment in oil and gas production include Fort McMurray and Cold Lake in Alberta and Fort Nelson in British Columbia. Communities with high concentrations of employment in auto manufacturing include Ingersoll and Windsor in Ontario. Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and Sept-Îles, Quebec have high concentrations of employment in steel and aluminum, respectively — sectors that could face tariffs of up to 50 per cent.

While the Trump administration has proposed a 10 per cent tariff on energy and minerals, lower than the 25 per cent he has threatened to place on manufactured goods, there is no guarantee that he will stick to that. It has become clear that any sector that depends on exports to the U.S. could be vulnerable to an unpredictable president.

Of course, impacts on these communities could be reduced if the U.S. decides to implement lower tariffs, if U.S. buyers struggle to find alternatives or if Canadian companies have ready access to alternative export markets.

The biggest impacts of the trade dispute may be felt as companies reduce investment in Canada, U.S. buyers adjust supply chains or businesses in Canada decide to relocate. Even if there is a reprieve from tariffs, the uncertainty could significantly dampen investment for some time.

Figure 4. Canadian communities with high concentrations of employment in sectors susceptible to the impacts of U.S. tariffs

If the U.S. tariffs are implemented, a certain amount of short-term harm will be unavoidable. But federal and provincial governments can help reduce the magnitude and duration through several key measures:

With the support of governments at all levels and the engagement of the private sector and communities, Canada can eventually emerge from the current turmoil with a stronger and more resilient economy that supports a high standard of living across the country for decades to come.

This commentary was written by Rachel Samson and Ricardo Chejfec. The manuscript was edited by Rosanna Tamburri and proofread by Paul Carlucci. Editorial co-ordination was by Étienne Tremblay, production was by Chantal Létourneau and art direction was by Anne Tremblay.

Rachel Samson is vice-president of research at the Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Ricardo Chejfec is lead data analyst at the Institute for Research on Public Policy.

To cite this document:

Samson, R., & Chejfec, R. (2025). More eggs, more baskets: Reducing Canada’s vulnerability to U.S. tariffs should start in the communities most affected. Institute for Research on Public Policy.