Global and Canadian efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and shift away from fossil fuels have created a central policy question: How can workers, sectors and regions adapt and develop the skills needed for a low-carbon future?

Some communities will feel the impacts sooner and more severely, particularly smaller, rural or remote areas with high concentrations of employment in exposed sectors and limited local economic diversification.

Although Canada offers a broad menu of supports for training, employment insurance and regional economic development, many programs are designed for the general population rather than tailored to the needs of susceptible communities. Targeted, place-based interventions that integrate economic and workforce development can help address this gap. Skills training and workforce development are critical levers for enabling effective and equitable transitions. This joint IRPP–Future Skills Centre research study reviews eight international initiatives — from Australia, Denmark, France, New Zealand, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States — that incorporate place-based approaches to skills training and workforce development designed to help workers stay in or close to their communities while gaining the skills they need for long-term employment. Viewed collectively, these case studies inform a comprehensive, unique-to-Canada framework for building workforce resilience in the net-zero transition. Each case highlights specific design choices, strategies, challenges and foundational elements that could be adapted to Canadian institutions and labour market realities.

For Canada, the lessons point to a practical path: identify susceptible communities using transparent indicators, and then governments can layer targeted strategic interventions — for example, training subsidies, infrastructure or economic development grants, targeted employer incentives and local employment services — in proportion to each community’s exposure and readiness. The forthcoming Sustainable Jobs Action Plan, mandated by the Canadian Sustainable Jobs Act, can incorporate these lessons by emphasizing robust co-ordination across orders of government and meaningful engagement with workers, unions, industry and Indigenous communities alongside investments in local capacity and policy certainty.

| ✔ Lesson 1 Consensus building and tripartite collaboration between government, industry and labour unions enable co-ordinated transition efforts. |

✔ Lesson 6 Participation of Indigenous Peoples and communities in transition planning and implementation is essential. |

| ✔ Lesson 2 Community involvement in transition planning builds local buy-in and resilience. |

✔ Lesson 7 Rural communities may require additional targeted supports to stabilize populations. |

| ✔ Lesson 3 Developing local, viable replacement industries before phasing out existing ones prevents community-level economic disruption. |

✔ Lesson 8 Mechanisms for continuous assessment and plan adaptation are essential to keeping strategies responsive. |

| ✔ Lesson 4 Proactively developing skills and leveraging transferable skills can smooth worker transitions. |

✔ Lesson 9 Workforce training harmonized with broader economic development plans is more effective. |

| ✔ Lesson 5 Robust targeted social supports mitigate transition risks for workers and communities. |

✔ Lesson 10 Technical, financial and administrative support is necessary to help communities with capacity constraints implement transition plans. |

Global and Canadian efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and shift away from fossil fuels have created a central policy question: How can workers, sectors and regions adapt and develop the skills needed for a low-carbon future?

As the energy system evolves, many local economies dependent on high-emitting employers, carbon-intensive sectors or exports of high-emissions goods to international markets that are undergoing transformation could experience disruption in the coming decades. There is an urgent need for co-ordinated transition strategies that build economic and workforce resilience (Chejfec et al., 2025; Samson et al., 2025).

When it comes to the low-carbon transition, not all regions or communities face the same degree of risk. Around 10 per cent of Canadians live in places susceptible to workforce disruption (Chejfec et al., 2025). These communities are, on average, smaller, more remote and less economically diverse than non-susceptible ones. Many rely on fossil fuel industries, such as coal, oil and gas, or emission-intensive manufacturing clusters, and a lack of capacity or resources may constrain their ability to pivot quickly to other economic opportunities. Moreover, the impacts extend beyond direct job losses to supply chains and consumer services reliant on the economic activity or spending generated by these susceptible industries. Workforce disruption can also come from major investments in areas of economic opportunity, such as when small businesses struggle to compete with larger employers for workers, when housing shortages drive up costs for lower wage workers or when the local population does not have the skills needed to take advantage of emerging employment opportunities.

Although Canada has a broad menu of supports available, including programs for training, employment insurance and regional economic development, these are often designed for the general population rather than tailored to the needs of susceptible communities. As a result, workers in these susceptible communities risk displacement and other transition-related workforce challenges. Targeted, place-based interventions that integrate economic and workforce development strategies can help address this. A broader range of supports is required to smooth transitions for workers and their communities, including flexible employment insurance, strategic economic development planning, adequate social services and appropriate incentives for employers, yet skills training and workforce development are critical levers for enabling effective and equitable transitions (Gordon & Callahan, 2023; Samson et al., 2025).

Interest in place-based policies has been growing due to their role in supporting communities through transition. Some scholars highlight the relevance of place-based approaches to pertinent policy domains, such as industrial policy, as they foster sustainable local and regional development (Bailey et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Pose & Wilkie, 2017), while others note their ability to support remote towns with resource-based economies (Darko & Halseth, 2023) as well as areas struggling with depopulation (Syssner, 2023).

Our research focuses on place-based skills training and workforce development, recognizing that local conditions shape both the urgency of labour market shifts and the design of effective learning opportunities. By tailoring skills-building programs to the specific economic realities, training and education infrastructure and capacity and resource endowments of each community, policymakers can help ensure that workers, sectors and regions remain competitive and resilient to the various disruptions that are likely to take place as Canada and the world move toward a net-zero economy.

The term “place-based policy” refers to government initiatives aimed at addressing the specific needs of particular geographic areas, such as communities, cities or regions. Unlike spatially blind policies, which apply generic solutions to all areas, place-based policies are explicitly designed to address the specific context and opportunities of a place or area (Beer, 2023; Beer et al., 2020).

Place-based policies often focus on improving economic performance by creating job opportunities, raising wages or enhancing local infrastructure (Neumark & Simpson, 2015). However, the scope of these policies can extend beyond economic goals, resulting in so-called soft infrastructure that takes the shape of stronger local networks and offers a greater sense of community cohesion (Beer, 2023, p. 29). These policies typically accept a longer-term perspective on challenges while acknowledging the connection and attachment that individuals and communities have to their sense of place (Beer, 2023).

Place-based policies can help individuals receive skills training that allows them to continue living and working in their community. Keeping youth and the working-age population in rural and remote communities can also support the vibrancy of these communities, maintaining consumers and workers for businesses and ensuring a strong tax base for local governments (Asquith & Mast, 2024). Central to place-based policy is the recognition that different places have unique characteristics and challenges that require tailored, localized interventions. The development of these policies often involves multiple stakeholders, including local governments, businesses and residents, in the identification and delivery of solutions (Beer et al., 2020). Place-based approaches also emphasize participatory decision-making and locally driven planning processes, ensuring that policy development reflects the lived experiences and priorities of community members. Some scholars have argued that these policies “embody an ethos about, and an approach to, the development of economies and society that acknowledges that the context of each and every city, region, and rural district offers opportunities for wellbeing” (Beer et al., 2020, p. 12). This approach ensures that no area, no matter how small or remote, is overlooked in efforts to foster economic and social development.

Canadian evidence shows that rural priorities and opportunities are often missing from broad, sector-oriented strategies. Local economic development rarely features in strategic agendas, and where it does, interventions are dated (Krawchenko et al., 2023). Distressed communities may lack the capacity to mobilize and co-ordinate actions internally; they may need upper-level governments to assume a substantial supporting role. Effective place-based policy design targets support and interventions to specific places (i.e., specific communities, cities or regions) and assesses the capacity of local actors and institutions to fully leverage these supports (Beer, 2023).

Our research adopts a working definition of place-based policy that encompasses both narrow and broad interpretations ranging from deeply localized initiatives embedded in community governance and participatory decision-making to broader strategies targeting region- or sector-specific outcomes (see Table A.1 in Appendix A).

In this study, we examine a range of international initiatives that incorporate place-based approaches to skills training and workforce development designed to help workers stay in or close to their communities while gaining the skills they need for long-term employment. With variations in design, stakeholder engagement, geography and specific objectives, we selected the case studies primarily for their relevance to the Canadian context. Viewed collectively, they each offer complementary pieces of the puzzle that, when assembled, inform a comprehensive unique-to-Canada framework for building workforce resilience in the net-zero transition.

Our key research questions comprise the following:

To inform Canada’s net-zero workforce transition, we sought a diverse set of case studies, each offering a specific piece of the puzzle.

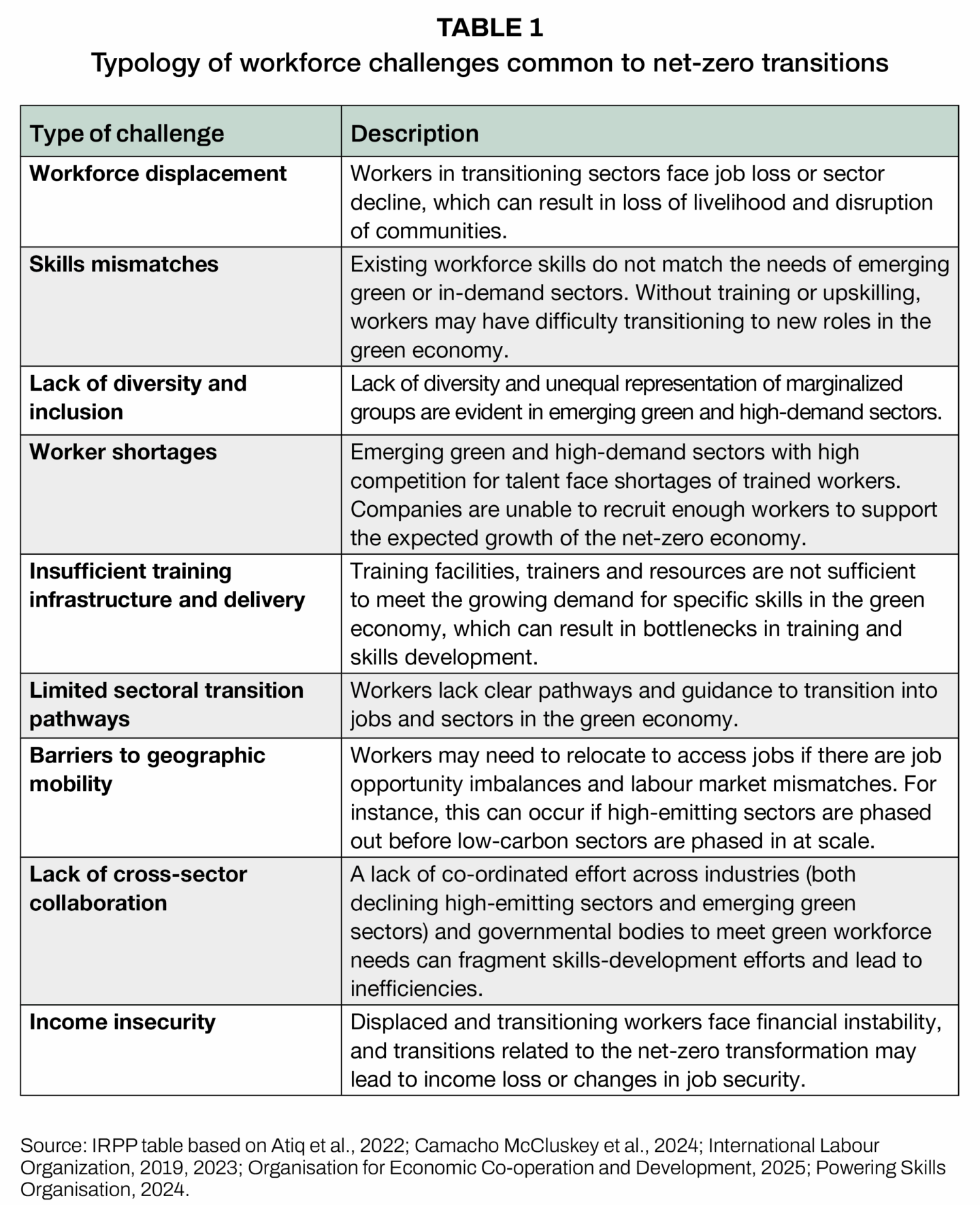

Taken together, these cases illuminate how various place-based programs and policies can be integrated into a comprehensive response that reflects Canadian realities. We recognize that place-based approaches — whether narrowly defined (i.e., deeply embedded in local governance with heavy reliance on community engagement) or broadly defined (i.e., targeting region- or sector-specific outcomes) — can help mitigate the key workforce challenges associated with decarbonization and the structural economic changes arising from global efforts to address climate change (see Table 1).

We selected eight initiatives spanning local to national scales, ranging from pilot-level efforts to well-established programs and employing a variety of policy instruments, governance approaches and funding mechanisms. Each case contributes distinctive insights into a subset of workforce challenges (e.g., creating transferable training models, strengthening social protections, leveraging community-based governance or forging innovative funding mechanisms). Collectively, these lessons could inform Canadian policymakers in the design of cohesive and comprehensive skills training and workforce development strategies that account for local and regional contexts, address multi-faceted equity considerations and advance net-zero commitments.

We began by compiling an initial list of potential initiatives and evaluated them against 11 criteria designed to capture both breadth and depth. These criteria included the initiative’s explicit or implicit links to net zero, place-based elements in design or implementation (broad and strict), the type of intervention (e.g., retraining, job matching, micro-credentialing), the evidence of innovative practices, the initiative’s alignment with Canadian workforce needs and the availability of measurable outcomes (see Table A.1 in Appendix A for the complete screening table). We paid particular attention to initiatives that address key workforce challenges identified in our typology, especially those most relevant to Canada’s transition context, and that offer transferable strategies or lessons.

This approach enabled us to home in on eight initiatives that align with net-zero goals and hold practical relevance and adaptability for Canadian policymakers and communities. We drew on government reports, peer-reviewed academic studies and institutional publications to populate a comparative spreadsheet for each initiative, noting the degree to which it fulfilled the various criteria. Additional materials reviewed included technical program manuals, legislative texts and summaries, government announcements and research and evaluation reports. We relied on publicly available secondary sources, conducting the review primarily in English but also consulting and translating relevant materials in other languages where necessary and feasible — for example, for the cases of Spain, France and Denmark. Given the recent nature of many place-based net-zero workforce initiatives, the primary limitations we faced were the uneven availability of quantitative and qualitative data across cases, the varied evaluation time frames and thin labour market outcomes.

Our structured international review, with a special focus on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, yielded the following eight cases (see Table A.2 in Appendix A for an overview):

Together, they provide a mixture of varying maturity, geographic scope, economic context (from industrial regions to rural areas) and institutional designs, ensuring a broad perspective on how different governments and stakeholders are tackling the workforce dimensions of net-zero transitions.

Beyond our formal selection criteria, each case study highlights distinct dimensions of place-based workforce development. The case of France exemplifies how portable, flexible national tools can be adapted to local and individual needs. The Michigan case study demonstrates the challenges posed by insufficient dedicated funding, limited co-ordination and the shifting policy priorities of changing administrations. The Australia example highlights proactive, targeted national planning backed by statutory authority to engage employers, and it underscores the role of industrial policy in facilitating net-zero transitions. The New Zealand case illustrates how community-led planning can broaden the focus of interventions beyond directly affected workers, and it highlights the importance of Indigenous engagement as well as the impacts of changes to climate policies. Denmark’s case study showcases the promise of leveraging local comparative advantages and skill transferability across sectors, supported by robust social supports and multi-stakeholder collaboration. The case of Spain highlights tripartite agreements and co-governance, as it pairs a national strategy with locally tailored Just Transition Agreements to sustain employment in depopulating areas through Job Banks, investment incentives and local restoration initiatives. The United Kingdom case study explores how devolved authority and funding at the local level address local skills needs in the auto sector while integrating broader community engagement to support the adoption of electric vehicles. Finally, the U.S. WORC Initiative shows how unique federal–state economic development agencies and a focus on distressed rural communities can prevent worker dislocation and population decline by supporting a wide range of community-led initiatives.

Some promising programs did not make the final selection for reasons of scope, comparability or limited data. Below, we note a few examples that we considered and explain why we did not include them in this study; we also highlight programs worthy of future attention.

We initially considered the U.S. Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization (POWER) Initiative, a federal grant program focused on communities transitioning from coal in Appalachia. However, we opted to profile the U.S. WORC Initiative instead because it addresses a wider array of rural economic challenges — beyond the decline of a single sector — and fosters adaptation to multiple forms of disruption (e.g., natural disasters, manufacturing closures). Given Canada’s vulnerability to varied economic stressors, a more generalizable framework (as seen in the latter initiative) may be especially relevant. Even so, the former initiative’s targeted coal-transition model offers valuable lessons in re-employment and community stabilization for single-sector regions, and it remains on our watch list.

South Korea’s bold National Strategy for a Great Transformation (featuring a Green New Deal, a Digital New Deal and a Stronger Safety Net) initially appeared promising. However, our limited ability to review Korean-language evaluations and other documents hindered our capacity to conduct an in-depth comparison. We further noted that recent research underscores the challenges to sustaining policy momentum for just transitions in South Korea (Lee et al., 2024). Given its scale and ambition, the Korean New Deal remains a program to watch as more evidence emerges, especially regarding its place-based components.

We limited our selection to three European Union (EU) cases — Denmark, France and Spain — partly to avoid redundancy. The EU’s overarching Just Transition Mechanism strongly influences many national approaches, from Germany’s transition away from coal to Italy’s transitioning regions. While these cases offer in-depth lessons on decarbonizing entrenched fossil fuel industries, their EU funding and governance structures share similar enabling conditions, and we wanted to avoid duplication across case studies. Policymakers interested in specialized phase-out processes — such as Germany’s coal exit or Italy’s transitioning steel sector — may find interesting insights in these unselected EU examples.

Across the eight case studies, several common factors emerged as key motivators for development of the initiatives.

Decarbonization goals and industrial transition

Across several case studies, including those in Spain, Denmark, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, countries are actively working toward their national and international climate commitments, including mandated net-zero and zero-emission-vehicle targets (Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities, 2020; His Majesty’s Government, 2021; International Energy Agency, 2023; Ministry for the Environment, 2020). Meeting these national emissions targets often requires phasing out carbon-intensive industries, such as coal mining, coal-fired power and oil and gas extraction (Ardern, 2018; del Río, 2017). In other cases, such as the one set in Michigan, industrial transitions in key industries, such as auto manufacturing, influenced workforce strategies (5 Lakes Energy et al., 2023).

Mitigating socio-economic impacts

In the absence of advanced planning, economic transformations can result in job losses, economic distress, social disruption and even outmigration in regions heavily reliant on transitioning industries. Several initiatives aim to mitigate these impacts and preserve local employment while sustaining the viability of the community. For example, the U.S. WORC Initiative supports sustainable employment in economically distressed areas so residents can stay in their communities (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.a). The Taranaki region in New Zealand relies on the comprehensive, long-term Taranaki 2050 Roadmap and 2025/26 Action Plan to sustainably diversify the local economy and ensure a healthy local community (Venture Taranaki, 2024). Spain’s JTS uses the Urgent Action Plan and co-governance agreements to stabilize local employment and rural populations in coal-dependent regions (Instituto para la Transición Justa [ITJ; “Just Transition Institute”], 2023).

Local vulnerabilities and regional disparities

Many regions featured in the case studies already face long-standing socio-economic challenges and pressures, such as lower employment rates, lower incomes, lower rates of training and qualifications, high rates of youth not in employment, education or training and insufficient economic diversification, all of which could be exacerbated through the net-zero transition in the absence of targeted policy interventions. Initiatives in the United Kingdom (e.g., the Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Training Centre), the United States (e.g., the WORC Initiative), New Zealand (e.g., the Taranaki 2050 Roadmap and 2025/26 Action Plan) and Spain (e.g., the Just Transition Agreements) are driven by the need to address these pre-existing vulnerabilities and persistent regional disparities.

Government strategies, legislation and dedicated bodies

High-level strategies, legislation and dedicated agencies often provide an overarching framework for the place-based actions that follow. Dedicated agencies and bodies range from Spain’s JTS and its autonomous ITJ to Australia’s NZEA, Michigan’s Community and Worker Economic Transition Office and regional commissions and authorities in the United States. In France, the CPF provides a national system for universal training entitlements that workers can draw on for a variety of re-skilling or up-skilling needs (Ministère du Travail, de la Santé, des Solidarités et des Familles [MTSSF; “Ministry of Work, Health, Solidarity and Families”], 2017). Legislation often underpins these efforts: in Spain, the 2019 JTS is anchored in the country’s Climate Change and Energy Transition Act (Government of Spain, 2021), and Australia’s NZEA is given legislated authority through the Net Zero Economy Authority Bill, passed in 2024 (Parliament of Australia, 2024).

Multi-stakeholder engagement

Recognizing the highly localized impacts of economic transitions, governments across the case studies sought extensive local stakeholder participation, which consistently enabled tailored interventions to leverage local assets and fit local needs. For example, Taranaki 2050 Roadmap (Venture Taranaki, 2019) involved extensive stakeholder participation and collaboration across government levels, unions, businesses, educational institutions and community members. Spain’s Just Transition Agreements (ITJ, 2020), Denmark’s Offshore Academy (Tänzler et al., 2024) and the Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Training Centre in Essex in the United Kingdom (Essex County Council, 2023) each relied on multi-stakeholder collaboration to effectively implement their place-based solutions.

Despite differences in program design, common skills training and workforce development strategies were deployed across the place-based initiatives in our compendium of case studies.

Skills development and training

The direct local provision of up-skilling, re-skilling, vocational training, certification programs and apprenticeships is a common strategy for helping workers transition into new jobs. Examples include local courses on hybrid and electric vehicle servicing and maintenance in Essex, U.K. (Essex County Council, 2023); local skills training for transitioning oil and gas workers to offshore wind jobs in Esbjerg, Denmark (Krawchenko, 2022); financial training credits for workers in France (MTSSF, 2017); requirements for companies to provide vocational training for affected workers as part of Spain’s Urgent Action Plan (ITJ, 2023); and diverse local workforce development initiatives funded through the U.S. WORC Initiative (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.a).

Employment support and job creation

Services like career counselling, job banks, re-employment services and job placement efforts support workers in finding new employment through the transition. Spain’s ITJ (2023) manages two local Job Banks that provide workers affected by closures with advisory services, individual career counselling and priority hiring for site-restoration activities. The U.S. WORC Initiative provides local projects with flexible funding to develop new employment opportunities and cover supportive services, such as counselling, transportation assistance and child care (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.a). Australia’s FMiA program offers industrial policy interventions, including investment and production tax subsidies and training and infrastructure grants, to support job creation in affected regions (Treasury, n.d., 2024). Local stakeholders in Taranaki, New Zealand, are actively working to de-risk and expand sectors such as food and fibre production to increase jobs in emerging, low-carbon industries (Venture Taranaki, 2024).

Economic diversification

Supporting the diversification of local economies by fostering the growth of new industries, including sustainable ones, creates alternative employment opportunities in transitioning regions. Spain’s Just Transition Agreements promote economic diversification in historically coal-dependent regions (Cirillo et al., 2024). In New Zealand, the Taranaki 2050 Roadmap emphasizes expanding new industries, including renewable energy, conservation, food and fibre and tourism, to replace oil and gas extraction (Venture Taranaki, 2019). Australia’s FMiA program provides fiscal support for targeted investments in green steel, hydrogen and renewable energy (Treasury, 2024). The U.S. WORC Initiative supports economic diversification by funding local projects that include training and employment pipelines in diverse sectors, such as health care, IT, manufacturing and clean energy (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.a).

Targeted support for vulnerable groups

Targeted supports for vulnerable groups, including women, youth and historically marginalized or disadvantaged populations who face higher barriers to employment or training, can improve their employment outcomes. Projects funded through Spain’s JTS receive additional incentives, such as social security contribution rebates for generating female employment (de Cabo Serrano et al., 2023). Denmark’s Offshore Academy supports workers on the edge of the labour market and targets the recruitment of women into the offshore energy sector (Esbjerg Havn, 2023; Port Esbjerg, 2022). France’s CPF provides higher levels of training credits for lower-skilled, lower-wage workers (MTSSF, 2017). New Zealand’s Taranaki 2050 Roadmap targets youth and Māori communities (Venture Taranaki, 2019), and Australia includes targeted initiatives to recruit women and Indigenous workers into sustainable industries (Australian Renewable Energy Agency, 2025; First Nations Clean Energy Network, 2024). Michigan Works programs target unemployed individuals, with some local agencies, such as the one in Detroit, expanding outreach to underserved and hard-to-serve populations, including youth in low-income neighbourhoods (Weems et al., 2024). The U.S. WORC Initiative targets rural communities experiencing economic distress, and applicants design projects that reach individuals from historically marginalized groups, including Black people, Indigenous Peoples, racialized people, LGBTQ2S+ individuals, women, veterans, people with disabilities and individuals without a college degree (U.S. Department of Labor, 2024).

Financial safeguards for transitioning workers

Some initiatives include measures to protect workers’ income stability through the transition, cover related costs or offset the costs of retraining. Denmark’s Offshore Academy leverages the national “flexicurity” system, which provides unemployment coverage for up to two years, and union agreements ensure Esbjerg port workers can receive up to six weeks of paid training each year (3F, n.d.; Danish Agency for Labour Market and Recruitment, 2024). Spain, through its JTS, offers early-retirement options and relocation assistance to older workers to cushion job losses in coal-dependent regions (ITJ, 2023). In the United Kingdom, local authorities in Essex subsidize training courses in hybrid and electric vehicle servicing and maintenance to lower cost barriers for both small local employers and workers (Local Government Association, 2022). The WORC Initiative grants fund supportive services, such as transportation, child care and counselling, lowering the economic hurdles that often accompany workforce transitions (U.S. Department of Labor, 2024).

Despite considerable commonalities across the compendium of our case studies, there is also substantial variation in how programs are delivered, governed and funded within a place-based framework.

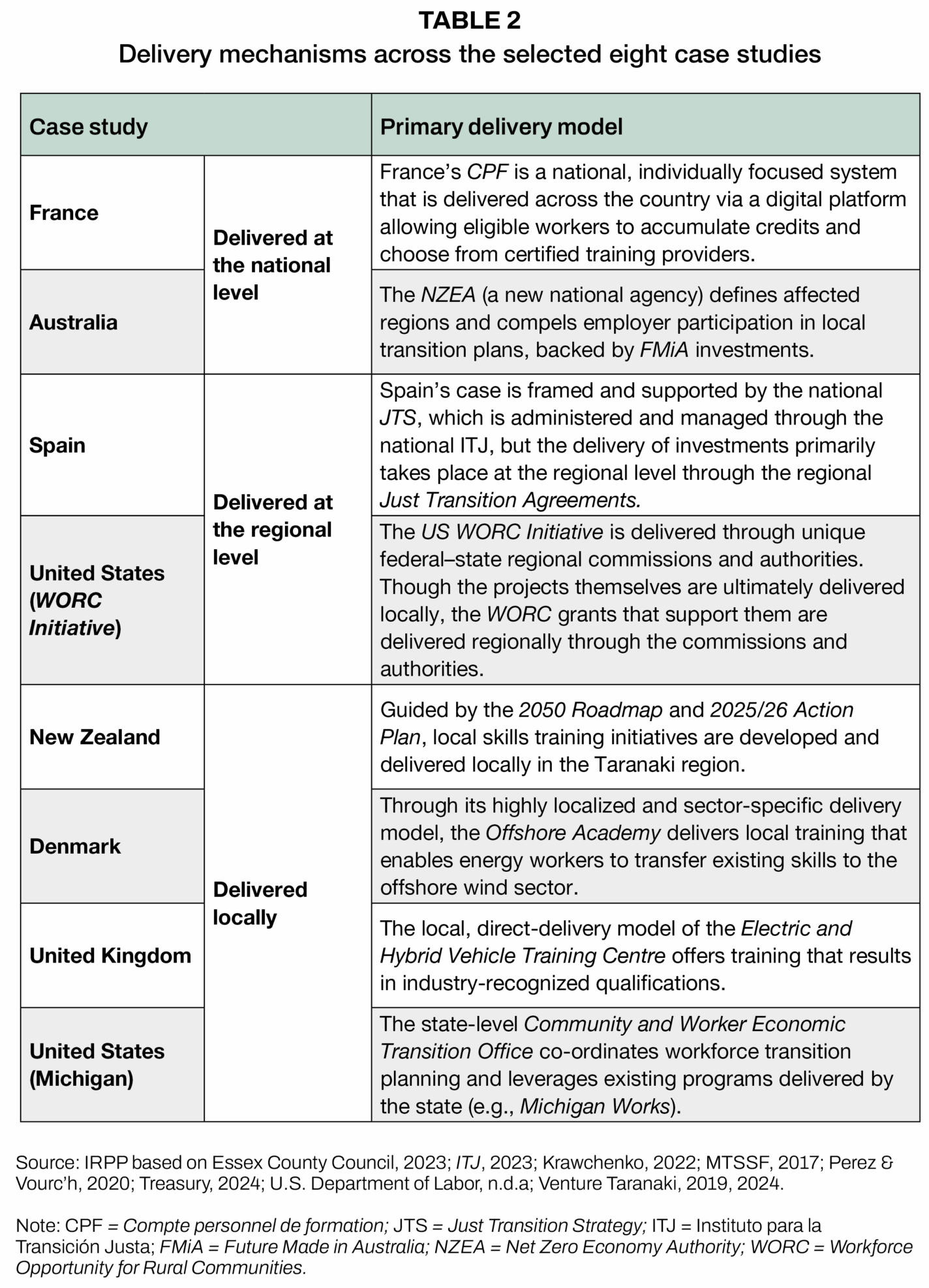

Program delivery

Variation in delivery mechanisms is often reflective of differences in design or the level at which the initiative is administered (see Table 2).

Governance

Governance structures can be visualized along a spectrum, with centralized national oversight with local adaptation at one end and predominantly community-led models at the other (see Figure 1). France offers a centralized example, with the CPF system governed nationally yet decentralized at the individual level so users can decide what training to pursue (MTSSF, 2017). Spain occupies a middle position extended to regional and local levels through co-governed Just Transition Agreements (ITJ, 2023). It uses a multi-level system led by the Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge and the autonomous ITJ. Australia established an independent statutory body — the federal NZEA — which designates affected regions and oversees transition plans (NZEA, n.d.). Michigan also created a state Community and Worker Economic Transition Office, though the office lacks dedicated funding or binding authority (Community and Worker Economic Transition Office, 2024).

Denmark’s Esbjerg model leans further toward local governance, with a partnership involving the municipally owned Port Esbjerg as well as trade unions and local learning institutions operating within national policy frameworks, including the national social-welfare state and flexicurity system (Kiernan, 2019). In New Zealand, the Taranaki region exemplifies community-led governance, with the Taranaki 2050 Roadmap — the main planning framework for the region’s transition — having emerged from a broad co-design process involving a wide range of community stakeholders (Venture Taranaki, 2019). The U.S. WORC Initiative blends federal oversight from the U.S. Department of Labor and administration via three regional commissions and authorities with bottom-up, community-developed projects that offer local workforce solutions (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.a). In Essex, U.K., the Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Training Centre is a local initiative resulting from a partnership involving county governments, a local college and local employers (Essex County Council, 2023).

Funding mechanisms

Funding sources and mechanisms range from national budgets to local initiatives and private investments (see Table 3).

Approaches to monitoring and evaluation as well as the availability of robust outcome data vary significantly across the case studies. Some initiatives have dedicated, structured monitoring and evaluation frameworks that incorporate a range of indicators, such as economic and well-being metrics (e.g., New Zealand’s Taranaki 2050 Roadmap). Others track simpler metrics, such as participant numbers (e.g., the Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Training Centre in Essex, U.K.) or the volume and distribution of successful grant applications and funded projects (e.g., the U.S. WORC Initiative, Spain’s JTS).

A common challenge is the limited availability of comprehensive labour market outcome data clearly capturing the effects of place-based net-zero policies or tracking workers’ adoption of new skills. This gap arises in part because many programs are relatively new and have not yet matured enough to produce measurable labour market impacts. Some initiatives are structured primarily around co-ordination, planning and early implementation rather than direct job placement (e.g., Australia’s NZEA and FMiA and the Michigan Community and Worker Economic Transition Office), with comprehensive, program-wide results not yet available. Others facilitate training more directly (e.g., the Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Training Centre in Essex, U.K., and Denmark’s Offshore Academy), but tracking how this translates into employment in green jobs, broader workforce transitions or community resilience is often difficult. For instance, France maintains detailed data on CPF training uptake but does not categorize outcomes by relevance to net-zero skills or employment transitions. Moreover, diverse interventions that are tailored and community specific may inherently limit cross-project comparability. For the U.S. WORC Initiative, for instance, the highly localized nature of place-based initiatives complicates the standardization and aggregation of outcome reporting to a broader scale.

Several common challenges and blind spots stood out that could hinder implementation or undermine long-term outcomes.

Policy uncertainty and reversals

Changes in government priorities or external pressures can lead to policy instability, such as the reversal of bans, adjustments to targets or changes to allocated funding, which can create uncertainty for long-term planning and investment. For example, the ban on offshore oil and gas exploration in New Zealand was recently repealed by a new government (Jones, 2024), and the United Kingdom recently proposed amendments to national electric-vehicle-sales targets in light of recent global uncertainty (His Majesty’s Government, 2025). In the United States, programs and investments related to the net-zero transition have been called into question as President Donald Trump’s administration has paused funding previously offered through the Inflation Reduction Act (Inflation Reduction Act Tracker, n.d.). Furthermore, in the United States, a recent budget proposal for fiscal year 2026 includes significant cuts to the Department of Labor and select regional commissions (Executive Office of the President, 2025), which may affect the WORC Initiative.

Lack of funding or resources

New initiatives and bodies (or agencies) created without dedicated funds often rely on existing resources, limiting effectiveness and staffing capacity. For instance, the Michigan Community and Worker Economic Transition Office lacks dedicated funding and struggled with staffing early on (Community and Worker Economic Transition Office, 2024). In New Zealand, the national Just Transitions Unit was shuttered despite its intended role in bridging funding gaps for local initiatives and projects (Gibson, 2024; Kiernan, 2019).

Pace of transition versus new industry growth

Traditional industries may decline faster than emerging ones can scale up, leaving transitioning workers without viable alternatives in the interim. In New Zealand, the local gas sector declined more rapidly than expected, while replacement industries grew more slowly and proved more costly and complex to develop (Venture Taranaki, 2024). This contrasts with the success of Denmark’s approach, which relied on an already developed and expanding wind sector to replace the economic activity, jobs and energy needs of the phase-out of the offshore oil and gas sector.

Place-based approaches are highly relevant to Canada’s net-zero transition due to the regional concentration of carbon-intensive industries and employment in the country (Chejfec et al., 2025).

Similar to several of the case studies in which fossil fuel employment is concentrated in specific communities, many Canadian communities are disproportionately reliant on sectors facing decline or transformation. Transition impacts and opportunities vary significantly across the country, and workforce exposure extends well beyond workers directly employed in affected sectors. The economic repercussions of closures and sector transitions can spread through entire communities when there is a high concentration of employment in a susceptible sector, and supply chains and consumer services tied to these industries are also affected (Chejfec et al., 2025). When economic disruption occurs at the community level, there can be knock-on effects in a range of areas, such as housing (Notowidigdo, 2020) and social cohesion (Wietzke, 2015).

Canadian policies can be tailored to the specific socio-economic conditions, workforce needs and potential growth sectors of different communities. Targeted place-based approaches could mitigate worker displacement and other risks associated with the transition, ensuring that workers move into quality local jobs rather than leave their home communities and regions.

In practice, this requires defining a transparent set of indicators, such as a community’s dependence on high-emitting industries, its share of supply-chain jobs and its unemployment trends as well as its fiscal, mobilization and co-ordination capacities, and then formally identifying the most susceptible communities. Recent research illustrates one such methodology, which combines sector-exposure metrics with local labour market indicators to map Canada’s most at-risk communities (Chejfec et al., 2025). Once these susceptible communities are identified, governments can layer targeted strategic interventions — such as training subsidies, infrastructure or economic development grants, targeted employer incentives and local employment services — in proportion to each community’s exposure and readiness (Jackson et al., 2025), mirroring the “lagging-region” and “just-transition” designations used in several of our case studies.

Our compendium of case studies offers a collection of both proven and experimental instruments that, when taken together, can inform a comprehensive, unique-to-Canada response to national net-zero workforce challenges. Each case illuminates a distinct piece of the puzzle, highlighting specific design choices, strategies, challenges and foundational elements that could be adapted to Canadian institutions and labour market realities.

Canada’s forthcoming Sustainable Jobs Action Plan, which the Canadian Sustainable Jobs Act (2024) mandates and which needs to be in place by the end of 2025, can incorporate lessons from these case studies. The action plans must outline federal strategies for promoting economic growth and sustainable jobs in Canada’s transition to net zero, including implementation measures that support skills development, data availability and gaps and key measures of intergovernmental co-operation that support the Canadian Sustainable Jobs Act. The act currently provides the legislative framework for this work, though a new government could choose to amend or repeal it, taking a different approach to transition planning. A successful and just transition requires more than national targets; it demands targeted, place-based strategies that address the specific challenges and opportunities in different regions. Any forthcoming action plans should emphasize robust co-ordination among federal, provincial, territorial and local governments alongside meaningful engagement with workers, unions, industry and Indigenous communities. Prioritizing policy certainty and investing in local capacity will be crucial for the plan’s effectiveness.

Each case study highlights specific lessons unique to place-based approaches in skills training and workforce development. Here, we have compiled some of those overarching insights, identifying key commonalities and differences, presenting illustrative evidence and discussing their relevance to the Canadian context.

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Co-ordination among federal, provincial/territorial and municipal governments can be complicated by siloed departments and top-down approaches that clash with local jurisdictions. Fostering broad social consensus for the Sustainable Jobs Action Plan through engagement and advising on areas for intergovernmental collaboration will be an essential function of the Sustainable Jobs Partnership Council (Canadian Sustainable Jobs Act, 2024). Ensuring that such dialogue leads to formal, resource-backed agreements will be critical for effective implementation.

Proactively establishing agreements between governments, Indigenous communities, industry and workers before closures — with clear funding commitments where appropriate, similar to Spain’s Just Transition Agreements — would be particularly beneficial for communities facing phase-outs of emissions-intensive industries, helping safeguard affected workers and communities. For instance, when the timeline of closures can be anticipated, as is the case with most coal mines and power plants (Environment and Natural Resources, 2024), tripartite agreements can bring stakeholders to the table to collaborate on solutions to ensure supports, such as skills training, career counselling and social services, are available to workers when they need them.

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Relevance to Canada

Canada’s education and training ecosystem is highly complex (Bonen & Oschinski, 2021), with a wide diversity of provincial and territorial supports currently in place through the Labour Market Development Agreements and the Workforce Development Agreements with the federal government. The federal government can proactively promote more bottom-up, community-led approaches to skills training when developing new programs and initiatives, including integrating community-led principles and approaches into the 2025 Sustainable Jobs Action Plan and into the Labour Market Development Agreements and Workforce Development Agreements through their renegotiations or amendments. This approach is particularly relevant in Indigenous communities, where supporting community principles and locally defined development priorities is fundamental. The federal government can also leverage the Sustainable Jobs Partnership Council to conduct community engagement at the local level in the most affected communities, ensuring that they have an opportunity to participate in transition planning.

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Relevance to Canada

By showing workers and citizens in carbon-intensive regions of Canada’s economy that concrete, targeted and effective levers will be used to minimize risks of involuntary dislocation, public concerns about decarbonization could be significantly assuaged. In many cases, the development of alternative industries will be specific to each place and region due to the recognition of local assets. For instance, in Nova Scotia, offshore wind may be a promising alternative to coal power for meeting regional electricity needs and generating local employment (Institute for Research on Public Policy, 2025a), while in other areas of the country, such as southern Saskatchewan, communities may pursue a mix of alternatives to coal power and mining, such as solar, geothermal, small modular nuclear reactors and critical minerals development (Institute for Research on Public Policy, 2025b).

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Relevance to Canada

By tapping into the transferability of existing skill sets and proactively offering accessible re-skilling and up-skilling programs, worker disruption can be minimized. When supporting communities through their workforce transitions, Canada should explore ways to leverage the congruencies of existing skills and emerging sectors. For example, Canadian coastal regions with shipbuilding, offshore oil and gas or other maritime experience could similarly adapt existing assets and skills to accelerate a transition to offshore wind. In the Prairies, conventional oil companies could use similar equipment and skill sets to extract lithium from deep brines underground. The challenge is finding an industry — or a suite of opportunities — that offers similar levels of employment and wages to those lost when local industries decline or close.

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Relevance to Canada

Canada can explore ways of adapting its own existing suite of social policy tools to proactively support transitioning workers and communities. This could include more flexible, generous and inclusive Employment Insurance benefits for people in communities facing a closure or the restructuring of a major employer, and it could include more support for mental health services, counselling and peer support in communities going through a transition.

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Relevance to Canada

Canadian parallels extend across the country where Indigenous communities are increasingly holding substantial ownership stakes in major natural resource and infrastructure projects or are relying on impact and benefit agreements (Canada Infrastructure Bank, n.d.; Conference Board of Canada, 2022; First Nations Major Projects Coalition, n.d.). Indigenous Peoples also have rights that need to be respected in the development of transition plans that could affect their traditional lands or ways of life. Comprehensive community planning, an asset-based approach spearheaded by First Nations in British Columbia, already guides local priorities in some areas — offering a model Canada could leverage and scale to ensure robust Indigenous engagement in community transitions (Samson et al., 2025). Ensuring co-design and shared decision-making can preserve cultural and identity values, protect livelihoods and harness Indigenous-led innovation.

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Relevance to Canada

Some susceptible Canadian communities could face risks of depopulation and an economic downturn if a primary industry closes. Offering place-based job creation during transitions, particularly during the closure and clean-up phases, and using tax credits, community benefit agreements and sponsored training programs to incentivize new industries to hire locally could mitigate out-migration. Targeted supports to sustain essential local community services, such as child care, health care and education, could further stabilize communities during transitions. Generating new sources of employment to replace declining industries often requires significant public and private investment. Strategies that combine short-term clean-up jobs with long-term investment in new industries that have significant growth potential would align with Canada’s commitment to leave no one behind, especially in regions facing a phase-out of coal power as a result of government policy (Corkal & Beedell, 2022).

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Relevance to Canada

For Canada — where provincial and federal policies and global market conditions can shift rapidly — continuous plan adaptation is essential. Embedding regular reviews, independent audits and community feedback loops into transition strategies can sustain momentum and credibility, especially in regions experiencing rapid market or policy changes. For example, in Ingersoll, Ontario, the largest local employer — the General Motors CAMI Assembly plant — recently transitioned from making internal combustion engine vehicles to assembling electric vans. However, with growing trade tensions between Canada and the United States and changing U.S. climate policy, the company decided to close the plant temporarily (Varley, 2025). Given ongoing uncertainty about timing and production volumes, Ingersoll will need a flexible economic development strategy that can adapt to evolving market conditions, which will likely require significant support from the provincial and federal governments (Institute for Research on Public Policy, 2025c).

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Relevance to Canada

Assuming continuity of the existing Sustainable Jobs Act framework, Canada’s forthcoming 2025 Sustainable Jobs Action Plan could similarly map congruencies between federal, provincial/territorial and regional economic development and workforce priorities to support the net-zero transition. Further, Canada’s Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) could do more to integrate regional workforce development and training opportunities into economic development programs. For instance, the RDAs could be key to achieving the country’s Innovation and Skills Plan. In the government’s progress tracker for the plan, five out of the six mentions of the RDAs address investment attraction or firm growth, but none of these mentions occur in the “People and Skills” section (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2020). Skills-related programming largely falls under the mandate of Employment and Social Development Canada and provincial/territorial governments; greater co-ordination between RDAs, Employment and Social Development Canada and provincial/territorial governments is needed to ensure that the RDAs’ business-growth supports and workforce development initiatives reinforce one another, rather than operate in silos.

Example evidence from compendium of studies

Relevance to Canada

In Canada, relevant bodies such as the Sustainable Jobs Secretariat, the Sustainable Jobs Partnership Council and the Net-Zero Advisory Body serve in advisory roles but have limited binding authority. While creating a new organization with the necessary legislative mandate and stable resources could streamline transition efforts, this might also be possible through better co-ordinating and directing existing organizations, such as RDAs and Community Futures organizations. In Spain, the ITJ’s role in identifying and co-ordinating funding offers a possible blueprint for how Canadian organizations might similarly tap into federal or provincial/territorial programs and private investments.

Taranaki 2050 Roadmap

https://www.taranaki.co.nz/assets/Uploads/Like-No-Other/Taranaki-2050-Roadmap.pdf

Taranaki 2025/26 Action Plan

https://www.venture.org.nz/assets/Tapuae-Roa-Action-Plan.pdf

The Compte personnel de formation

https://www.moncompteformation.gouv.fr/

Community and Worker Economic Transition Office

https://www.michigan.gov/leo/bureaus-agencies/economic-transition

Michigan Works

https://www.michiganworks.org/

Workforce Opportunity for Rural Communities (WORC) Initiative

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/dislocated-workers/grants/workforce-opportunity

Just Transition Strategy

https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/ministerio/planes-estrategias/transicion-justa/Just%20Transition%20Strategy_ENG.pdf

Job Banks

For workers in coal-fired power stations: https://www.transicionjusta.gob.es/en/bolsa-trabajo/ centrales-termicas.html

For surplus workers from the closures in the coal-mining sector: https://www.transicionjusta.gob.es/es/bolsa-trabajo/mineria-carbon.html

Instituto para la Transición Justa

https://www.transicionjusta.gob.es/

Net Zero Economy Authority

https://www.netzero.gov.au/

Future Made in Australia

https://treasury.gov.au/policy-topics/future-made-australia

Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Training Centre at Harlow College

https://www.harlow-college.ac.uk/study-options/category/automotive-studies-2019-21?f=1

Offshore Academy

https://portesbjerg.dk/en/news/new-offshore-training-programme-to-ensure-the-right-skill-sets-for-offshore-wind-adventure

3F. (n.d.). Collective agreements. Retrieved May 10, 2025, from https://www.3f.dk/english/ wages-and-sectors/collective-agreements

5 Lakes Energy, Michigan Energy Innovation Business Council, Evergreen Collaborative, & RMI. (2023, August 10). The Michigan Clean Energy framework: Assessing the economic and health benefits of policies to achieve Michigan’s climate goals. https://5lakesenergy.com/ wp-content/uploads/2023/08/5-Lakes-MEIBC-MI-Clean-Energy-Framework-report.pdf

Appalachian Regional Commission. (n.d.). Local development districts. Retrieved May 1, 2025, from https://www.arc.gov/map/local-development-districts/

Ardern, J. (2018, April 12). Planning for the future: No new offshore oil and gas exploration permits. New Zealand Government. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/planning-future-no-new-offshore-oil-and-gas-exploration-permits

Asquith, B. J., & Mast, E. (2024). The past, present, and future of long-run local population decline. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. https://doi.org/10.17848/pb2024-76

Atiq, M., Coutinho, A., Islam, A., & McNally, J. (2022, May). Jobs and skills in the transition to a net-zero economy: A foresight exercise. Smart Prosperity Institute. https://www.torontomu. ca/diversity/reports/Jobs_and_Skills_in_the_Transition_to_a_Net-Zero_Economy.pdf

Australian Renewable Energy Agency. (2025, March 7). Marching forward: The women leading the way in clean energy. https://arena.gov.au/blog/women-inspire-renewable-energy-sector/

Bailey, D., Pitelis, C., & Tomlinson, P. R. (2018). A place-based developmental regional industrial strategy for sustainable capture of co-created value. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 42(6), 1521–1542. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bey019

Beer, A. (2023, September 15). The governance of place-based policies now and in the future? Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/content/ dam/oecd/en/about/projects/cfe/place-based-policies-for-the-future/the-governance-of-place-based-policies-now-and-in-the-future.pdf

Beer, A., McKenzie, F., Blažek, J., Sotarauta, M., & Ayres, S. (2020). 1. What is place-based policy? Regional Studies Policy Impact Books, 2(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/257871 1X.2020.1783897

Bolter, K., Miller-Adams, M., Bartik, T. J., Hershbein, B. J., Huisman, K., Timmeney, B. F., Asquith, B. J., Pepin, G., Adams, L., Brown, J., Anderson, G., & Colosky, A. (2022).

Bridging research and practice to achieve community prosperity. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. https://research.upjohn.org/reports/278

Bonen, T., & Oschinski, M. (2021, January 6). Mapping Canada’s training ecosystem: Much needed and long overdue. Institute for Research on Public Policy. https://irpp.org/research-studies/mapping-canadas-training-ecosystem-much-needed-and-long-overdue/

Camacho McCluskey, K., Hanna, R., & Rhodes, A. (2024, October). Net-zero skills: Jobs, skills and training for the net-zero energy transition. Energy Futures Lab, Imperial College

London. https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/server/api/core/bitstreams/23fc4411-778c-48b7-b1b4-151607e1eea3/content

Canada Infrastructure Bank. (n.d.). Indigenous Community Infrastructure Initiative (ICII). https:// cib-bic.ca/en/indigenous-community-infrastructure/

Canadian Sustainable Jobs Act (S.C. 2024, c. 13). https://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/ acts/C-23.25/FullText.html

Chejfec, R., Samson, R., & Jackson, A. (2025, January). Supporting workers and communities on the road to net zero. A methodology for measuring community susceptibility (IRPP Study No. 95). Institute for Research on Public Policy. https://irpp.org/wp-content/ uploads/2025/01/Supporting-Workers-and-Communities-on-the-Road-to-Net Zero.pdf

Cirillo, V., Divella, M., Ferrulli, E., & Greco, L. (2024). Active labor market policies in the framework of Just Transition programs: The case of Italy, Spain, and Germany (ÖFSE Working Paper Series, No. 79). Austrian Foundation for Development Research. https://doi. org/10.60637/2024-wp79

Community & Worker Economic Transition Office. (2025). 2024 annual report. Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity, Government of Michigan. https://www.michigan.gov/ leo/-/media/Project/Websites/leo/Documents/Economic-Transition/Transition-Office-2024-Annual-Report-Accessible.pdf

Conference Board of Canada. (2022, February 7). Indigenous ownership: A new economic era.

https://www.conferenceboard.ca/in-fact/indigenous-ownership/

Corkal, V., & Beedell, E. (2022, January). Making good green jobs the law: How Canada can build on international best practice to advance just transition for all. International Institute for Sustainable Development. https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2022-01/green-jobs-advance-canada-just-transition.pdf

Danish Agency for Labour Market and Recruitment. (2024). Flexicurity. https://www.star.dk/en/ about-the-danish-agency-for-labour-market-and-recruitment/flexicurity

Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities. (2020). Climate Act, Act No. 965, 26 June 2020. https://www.en.kefm.dk/Media/1/B/Climate%20Act_Denmark%20-%20 WEBTILG%C3%86NGELIG-A.pdf

Darko, R., & Halseth, G. (2023). Mobilizing through local agency to support place-based economic transition: A case study of Tumbler Ridge, BC. The Extractive Industries and Society, 15: 101313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2023.101313

de Cabo Serrano, G., González Gago, E., & Rodríguez Lupiáñez, M. T. (2023, March). Women’s green entrepreneurship and women’s entrepreneurship in rural areas. Government of Spain, Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge. https://www.miteco. gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/ministerio/planes-estrategias/igualdad-de-genero/archivos-base/executive_summary_MITECO_women_entrepreneurship_green_rural_2023.pdf

del Río, P. (2017). Coal transition in Spain: An historical case study for the project “Coal Transitions: Research and Dialogue on the Future of Coal.” Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations & Climate Strategies. https://www.iddri.org/sites/ default/files/PDF/Publications/Catalogue%20Iddri/Rapport/201706-reportSpain-iddri-climatestrategies-coal_es_v04.pdf

Environment and Natural Resources. (2024). Powering Past Coal Alliance: Phasing out coal.

Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/ climatechange/canada-international-action/coal-phase-out.html

Esbjerg Havn. (2023). ESG rapport 2022 [ESG report 2022]. https://portesbjerg.dk/pdflibrary/ ESGrapport2022-Esbjerg-Havn.pdf

Essex County Council. (2023, March 10). £100k investment in new electric vehicle repair and maintenance courses at Harlow College. https://www.essex.gov.uk/news/2023/ps100k-investment-new-electric-vehicle-repair-and-maintenance-courses-harlow-college

European Commission. (2022, November 25). EU cohesion policy: €89 million for a just climate transition in Denmark. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/whats-new/newsroom/25-11-2022-eu-cohesion-policy-eur89-million-for-a-just-climate-transition-in-denmark_en

Executive Office of the President. (2025). Fiscal year 2026 discretionary budget request. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Fiscal-Year-2026-Discretionary-Budget-Request.pdf

First Nations Clean Energy Network. (2024). Clean Energy Jobs Pathway Initiative. https://www. firstnationscleanenergy.org.au/jobs_pathway_initiative

First Nations Major Projects Coalition. (n.d.). Stronger together. Retrieved March 26, 2025, from https://fnmpc.ca/

Gibson, E. (2024, October 30). Fossil fuel jobs unit closed because it didn’t align with government priorities. Radio New Zealand. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/environment/532284/ fossil-fuel-jobs-unit-closed-because-it-didn-t-align-with-government-priorities

Gordon, M., & Callahan, A. (2023, December). A sustainable jobs blueprint, part II: Putting workers and communities at the centre of Canada’s net zero energy economy. The Pembina Institute. https://www.pembina.org/reports/sj-blueprint-part-2.pdf

Government of Spain. (2021, May 21). Ley 7/2021, de 21 de mayo, de cambio climático y transición energética [Law 7/2021, of May 21, on climate change and energy transition]. Head of State. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2021/05/20/7

Harlow College. (2023, March 10). £100k Essex County Council investment in new electric vehicle repair and maintenance courses at Harlow College. https://www.harlow-college. ac.uk/about/news/831-100k-essex-county-council-investment-in-new-electric-vehicle-repair-and-maintenance-courses-at-harlow-college

His Majesty’s Government. (2021, October). Net Zero Strategy: Build back greener. https:// assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6194dfa4d3bf7f0555071b1b/net zero-strategy-beis.pdf

His Majesty’s Government. (2025, April 6). Backing British business: Prime minister unveils plan to support carmakers. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/backing-british-business-prime-minister-unveils-plan-to-support-carmakers

Inflation Reduction Act Tracker. (n.d.). Inflation Reduction Act tracker. Retrieved May 11, 2025, from https://iratracker.org/actions/

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. (2020). Tracking progress and results: The Innovation and Skills Plan. Government of Canada. https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/ innovation-better-canada/en/tracking-progress-and-results-innovation-and-skills-plan

Institute for Research on Public Policy. (2025a, March 25). Cape Breton: Region built on coal looks to renewable energy. Institute for Research on Public Policy. https://irpp.org/research-studies/region-built-on-coal-looks-to-renewable-energy/

Institute for Research on Public Policy. (2025b, January 14). Estevan: Saskatchewan’s energy city seeks to chart its own course. https://irpp.org/research-studies/saskatchewan-energy-city-chart-own-course/

Institute for Research on Public Policy. (2025c, January 14). Ingersoll: Ontario auto town grapples with the EV transition. https://irpp.org/research-studies/ontario-auto-town-grapples-with-ev-transition/

Instituto para la Transición Justa. (n.d.). Fondo de transición justa UE [EU Just Transition Fund]. Government of Spain, Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge. https://www.transicionjusta.gob.es/es/la-transicion-justa/fondo-de-transicion-justa-ue.html

Instituto para la Transición Justa. (2020). Just Transition Strategy. Government of Spain, Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge. https://www.miteco. gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/ministerio/planes-estrategias/transicion-justa/Just%20 Transition%20Strategy_ENG.pdf

Instituto para la Transición Justa. (2023, May). Spain, 4 years towards a just energy transition.

Government of Spain, Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge. https://www.transicionjusta.gob.es/content/dam/itj/files-1/Documents/Publicaciones%20 ES%20y%20EN/Spain_4%20years%20towards%20a%20just%20energy%20transition.pdf

International Energy Agency. (2023, August 3). Spain’s Just Transition Strategy. https://www. iea.org/policies/17830-spains-just-transition-strategy

International Labour Organization. (2019). Skills for a greener future: A global view. International Labour Office. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_emp/ documents/publication/wcms_732214.pdf

International Labour Organization. (2023, June). Just transition policy brief. https://www.ilo. org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_emp/@emp_ent/documents/publication/ wcms_886544.pdf

Jackson, A., Samson, R., & Chejfec, R. (2025). Resilient workers, resilient communities: The need for place-based skills development. Institute for Research on Public Policy. https:// irpp.org/research-studies/resilient-workers-resilient-communities/

Jackson, A., Yassin, S., & Gu, J. (2025a). From oil and gas to a diversified economy: Taranaki’s just transition roadmap in New Zealand. Future Skills Centre and Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Jackson, A., Yassin, S., & Gu, J. (2025b). Preparing the U.K.’s electric and hybrid vehicle workforce: Harlow College’s up-skilling approach in Essex. Future Skills Centre and Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Jackson, A., Yassin, S., & Gu, J. (2025c). The Workforce Opportunity for Rural Communities Initiative: Place-based workforce development in Appalachia, the Lower Mississippi Delta and the northern border regions of the United States. Future Skills Centre and Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Jackson, A., Yassin, S., & Pautonnier, V. (2025). From oil and gas to wind: Esbjerg’s Offshore Academy in Denmark. Future Skills Centre and Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Jensen, C. S. (2015). Employment relations, flexicurity, and risk: Explaining the risk profile of the Danish flexicurity model. In T. T. Bengtsson, M. Frederiksen, & J. E. Larsen (Eds.), The Danish welfare state (pp. 55–71). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link.springer.com/ chapter/10.1057/9781137527318_4

Jones, S. (2024, June 9). Government to reverse oil and gas exploration ban. Government of New Zealand. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-reverse-oil-and-gas-exploration-ban

Kiernan, S. (2019). A just transition for oil and gas regions? A comparative analysis of just transition policies in Denmark, New Zealand and Scotland [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Victoria. https://dspace.library.uvic.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/c560357a-b1d5-473f-a67c-22860c23e778/content

Krawchenko, T. (2022, July 18). Managing a just transition in Denmark. Canadian Climate Institute. https://climateinstitute.ca/publications/managing-a-just-transition-in-denmark/

Krawchenko, T., & Gordon, M. (2022). Just transitions for oil and gas regions and the role of regional development policies. Energies, 15(13), 4834. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15134834

Krawchenko, T., Hayes, B., Foster, K., & Markey, S. (2023). What are contemporary rural development policies? A pan-Canadian content analysis of government strategies, plans, and programs for rural areas. Canadian Public Policy, 49(3), 252–266. https://doi. org/10.3138/cpp.2022-060

Lee, H., Kang, M., & Lee, E. (2024). Lost in communication: The vanished momentum of just transition in South Korea. Energy Research & Social Science, 115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. erss.2024.103642

Local Government Association. (2022, September 1). Essex County Council: Electric vehicle training. https://www.local.gov.uk/case-studies/essex-county-council-electric-vehicle-training

Ministère du Travail, de la Santé, des Solidarités et des Familles [Ministry of Work, Health, Solidarity and Families]. (2017, November 2). Le compte personnel de formation (CPF) [The Personal Training Account (PTA)]. Government of France. https://travail-emploi.gouv.fr/le-compte-personnel-de-formation-cpf#anchor-navigation-659

Ministry for the Environment. (2020, June 6). Paris Agreement. New Zealand Government. https://environment.govt.nz/what-government-is-doing/international-action/about-the-paris-agreement/

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation. (2024, May 10). What we do. https://www.nrf.gov. au/what-we-do

Net Zero Economy Authority. (n.d.). Our work. Australian Government. Retrieved May 10, 2025, from, https://www.netzero.gov.au/our-work

Neumark, D., & Simpson, H. (2015). Chapter 18: Place-based policies. Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, 5, 1197–1287. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/ pii/B9780444595317000181?via%3Dihub

Notowidigdo, M. J. (2020). The incidence of local labor demand shocks. Journal of Labor Economics, 38(3), 687–725. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/ abs/10.1086/706048?journalCode=jole

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025, January). A fair net-zero transition: Labour market policies to meet climate targets [Policy brief]. https://www. oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/01/a-fair-net zero-transition_ ac8966ce/98a67eef-en.pdf

Parliament of Australia. (2024). Net Zero Economy Authority Bill 2024. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22legislation

Perez, C. (2019). Avec le Compte personnel de Formation: L’avènement d’une logique marchande et désintermédiée [The Personal Training Account: Advent of a market-based and disintermediated logic]. Savoirs: Revue internationale de recherches en éducation et formation des adultes, 50(2), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.3917/savo.050.0087

Perez, C., & Vourc’h, A. (2020, July 3). Individualising training access schemes: France – the Compte Personnel de Formation (Personal Training Account – CPF). (OECD Social,

Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 245). OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd. org/en/publications/individualising-training-access-schemes-france-the-compte-personnel-de-formation-personal-training-account-cpf_301041f1-en.html

Port Esbjerg. (2022). Port Esbjerg sustainability strategy: Health, safety and the environment.

https://portesbjerg.dk/downloads/baeredygtighedsbrochure_uk_22.pdf

Powering Skills Organisation. (2024). Workforce plan 2024. The new power generation: Challenges and opportunities within Australia’s energy sector (Version 14, with appendix). https://poweringskills.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Workforce-Plan-Report_2024_ Version-14-August-2024_with-appendix.pdf

Robson, J., & Bruno, J. (2025a). Aligning training with the transition: How France’s Personal Training Account supports workforce adaptability. Future Skills Centre and Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Robson, J., & Bruno, J. (2025b). Michigan’s Transition Office: Steering workforce development toward net zero. Future Skills Centre and Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Wilkie, C. (2017). Revamping local and regional development through place-based strategies. Cityscape, 19(1), 151–170. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26328304

Samson, R., Jackson, A., & Chejfec, R. (2025, January 14). Empowering community-led transformation strategies: Government-backed community development plans are most likely to succeed [Policy brief]. Institute for Research on Public Policy. https://irpp.org/ research-studies/empowering-community-led-transformation-strategies/

Segal, M. (2023, May 21). Denmark is getting off fossil fuels. Are there lessons for Canada?

CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/whatonearth/denmark-fossil-fuels-canada-1.6849212

Syssner, J. (2023, June 9). Place-based policy objectives and the provision of public goods in depopulating areas: Equality, adaptation, and economic sustainability. Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/dam/oecd/ en/about/projects/cfe/place-based-policies-for-the-future/place-based-policy-objectives-and-the-provision-of-public-goods-in-depopulating-areas-equality-adaptation-and-economic-sustainability.pdf

Stanford, J. (2025). Future Made in Australia and Net Zero Economy Authority: Transitioning carbon-intensive communities and charting a place-based low-carbon course. Future Skills Centre and Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Tänzler, D., Bernstein, T., & Hilliges, M. (2024, March). JET-P study: Compilation of the EU’s experience on just energy transition and recommendations for Indonesia. European Union Climate Dialogues. https://www.jetknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/JETP-Study-Compilation-EU-Just-Energy-Transition-Recommendation-for-Indonesia.pdf

Treasury. (n.d.). Future Made in Australia. Australian Government. Retrieved May 11, 2025, from https://treasury.gov.au/policy-topics/future-made-australia

Treasury. (2024). Budget 2024–25: A future made in Australia. Australian Government. https:// archive.budget.gov.au/2024-25/factsheets/download/factsheet-fmia.pdf

U.S. Department of Labor. (n.d.a). Workforce Opportunity for Rural Communities (WORC) Initiative. Employment and Training Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2025, from https:// www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/dislocated-workers/grants/workforce-opportunity

U.S. Department of Labor. (n.d.b). National Dislocated Worker Grants. Employment and Training Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2025, from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/ dislocated-workers

U.S. Department of Labor. (2024). Workforce Opportunity for Rural Communities (WORC) round 6: A grant initiative for the Appalachian, Delta, and Northern Border regions (Funding Opportunity Announcement No. FOA-ETA-24-08). Employment and Training Administration. https://mymccs.me.edu/ICS/icsfs/FOA-ETA-24-08.pdf?target=1cea12e8-4230-4518-a580-db94a1600b82

Varley, K. (2025, April 14). Ingersoll CAMI plant shutdown starts today. CTV. https://www. ctvnews.ca/london/article/ingersoll-cami-plant-shutdown-starts-today/

Venture Taranaki. (2019, July). Taranaki 2050 roadmap: Our just transition to a low-emissions economy. https://www.taranaki.co.nz/assets/Uploads/Like-No-Other/Taranaki-2050-Roadmap.pdf

Venture Taranaki. (2024, November). Tapuae Roa 2025/26 Action Plan update. https://www. venture.org.nz/assets/Tapuae-Roa-Action-Plan.pdf

Weems, T., Thompson, A., & Williams, D. L. (2024). The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA): Mid-cycle modification of four-year local plan for program years 2024 through 2027. City of Detroit, Mayor’s Workforce Development Board & Detroit at Work. https:// workforcedetroit.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/desc-local-plan-py-2024-through-2027. pdf

Whetu, J. (n.d.). Is a “just transition” possible for Māori? New Zealand Association for Impact Assessment. Retrieved May 11, 2025, from https://www.nzaia.org.nz/jameswhetu.html

Wietzke, F. B. (2015). Pathways from jobs to social cohesion. The World Bank Research Observer, 30(1), 95–123. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lku004

World Resources Institute. (2021, December 23). Spain’s national strategy to transition coal-dependent communities. https://www.wri.org/update/spains-national-strategy-transition-coal-dependent-communities

Yassin, S., Jackson, A., & Male, H. (2025). Spain’s Just Transition Strategy, Urgent Action Plan and Just Transition Agreements: Guiding coal-dependent regions through decarbonization. Future Skills Centre and Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Shaimaa Yassin is a senior research director at the Institute for Research on Public Policy, where she leads the Toward a More Equitable Canada research program and the IRPP’s role as a research and knowledge mobilization partner of the Affordability Action Council, of which she is also a member. She also contributes to IRPP’s Community Transformations Project. A labour economist by training, she holds a PhD in economics from the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and a MSc in empirical and theoretical economics from the Paris School of Economics. Shaimaa has an extensive record of publications, including peer-reviewed journal articles and books. She previously served as senior director at the Community Economic Development and Employability Corporation (CEDEC) in Montreal and has consulted for several governments and organizations such as the World Bank, Chaire “Sécurisation des Parcours Professionnels” in France, and the Economic Research Forum in Egypt. She was also a research fellow in the economics department of several academic institutions, namely McGill University (Swiss National Science Foundation Fellow), the University of Lausanne and the University of Neuchâtel.

Abigail Jackson is a research associate at the Institute for Research on Public Policy, where she has worked on a number of initiatives, including the Toward a More Equitable Canada research program and the Community Transformations Project. Abigail served on the secretariat of the Affordability Action Council and contributed to the research and writing of five policy briefs related to housing, transportation and food in the context of climate and affordability challenges. In 2023, she received the Jack Layton Prize for a Better Canada. Previously, Abigail worked at Habitat for Humanity, administering programs related to energy efficiency, affordable housing and community development. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in business and international political economy from the University of Puget Sound and a Master of Public Policy from McGill University.

To cite this document:

Yassin, S., Jackson, A. (2025). Learning from Place-Based Approaches on the Road to Net Zero. Future Skills Centre and Institute for Research on Public Policy

The authors gratefully acknowledge Jiaxin Gu’s, Valentin Pautonnier’s and Hannah Male’s research assistance; Rachel Samson’s insightful review and helpful comments; Jim Stanford’s, Jennifer Robson’s and Julia Bruno’s authorship of select case studies; Tamara Krawchenko’s, Megan Gordon’s and Sophie Kiernan’s insights and input; and the Future Skills Centre team’s helpful review comments, particularly those of Alexander Stephens. Paul Carlucci copy-edited the manuscript.

The Future Skills Centre (FSC) is a forward-thinking centre for research and collaboration dedicated to driving innovation in skills development so that everyone in Canada can be prepared for the future of work. We partner with policymakers, researchers, practitioners, employers and labour, and post-secondary institutions to solve pressing labour market challenges and ensure that everyone can benefit from relevant lifelong learning opportunities. We are founded by a consortium whose members are Toronto Metropolitan University, Blueprint, and The Conference Board of Canada, and are funded by the Government of Canada’s Future Skills Program.