Every year, 30,000 agricultural migrant workers arrive in Canada as part of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP), the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program and the Low Skill Pilot Project. Although the TFWP is intended to address short-term labour demands, most of these workers return to the same communities year after year, sometimes for more than 25 years. As a result, growing numbers of migrant farm workers are permanently temporary.

The increased presence of temporary workers will most certainly have an impact on Canadian communities and workplaces for years to come. Is there a way to conceptualize integration in the context of these migration patterns? How does the TFWP fit into Canada’s multicultural landscape and its goals of integration and social cohesion? In this study, Jenna Hennebry draws on experience with agricultural workers to address some of these questions.

The author uses empirical data, interviews and research on the situation in Ontario, the province with the largest number of agricultural migrants, to examine the degree of integration of migrant farm workers. She finds that their inclusion in the communities where they live and work is poor, despite laudable efforts by nongovernmental organizations, community groups and unions – notably the United Food and Commercial Workers Canada union, which has sponsored some unique transnational initiatives.

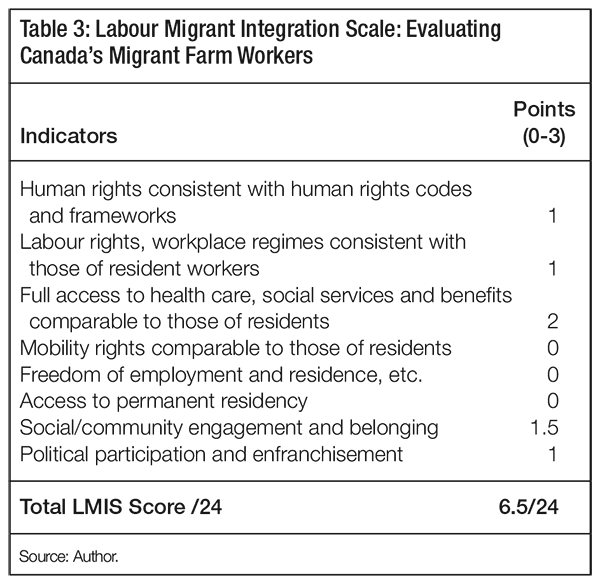

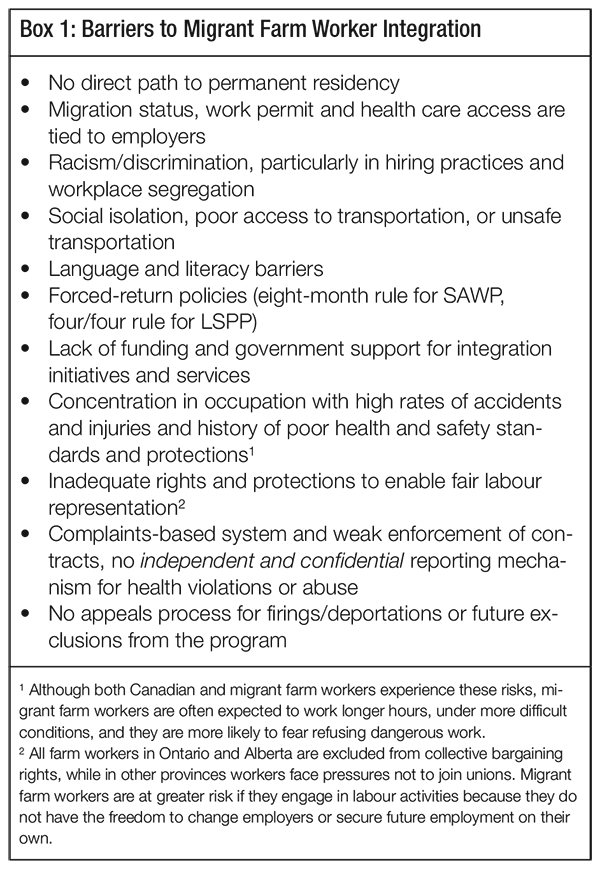

Building on this analysis, Hennebry discusses new ways of conceptualizing and evaluating integration as the concept applies to temporary labour migration. She proposes the Labour Migrant Integration Scale, which she developed for this study, as a tool for evaluating the results of temporary labour migration programs with respect to factors such as human and labour rights, access to social and medical services, and social/community engagement and belonging. Despite Canada’s long experience in agricultural labour migration, our programs do not measure up. Temporary migrants face significant impediments to labour market and social integration, including work permits that are tied to employers, weak enforcement of contracts, language barriers and social isolation, especially for the large share of these workers who live in employer-provided housing.

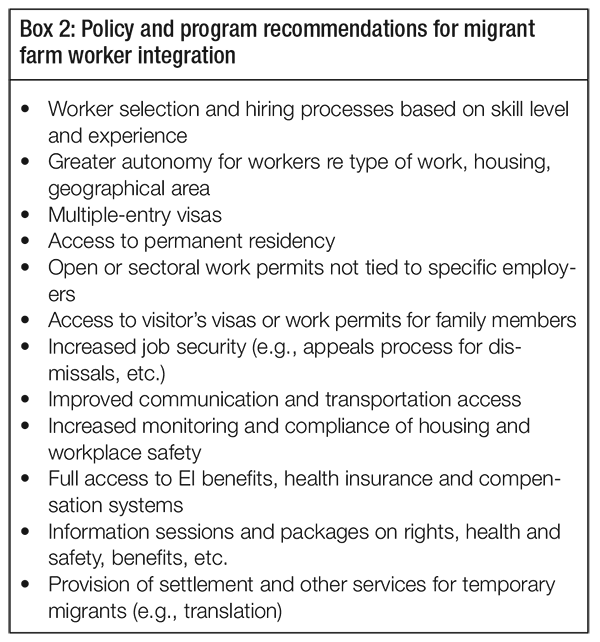

Hennebry ends with recommendations for improving policy and practice in the management of temporary labour migration in agriculture, including greater autonomy for workers in choosing where they work and live, regulation of the recruitment process, wider use of information sessions on health and safety, and access to certain settlement services such as basic language training. Recognizing the interjurisdictional challenges and transnational nuances of temporary migration, she also calls for more rigorous application of existing laws and regulations.

Canada has had a specific program for migrant farm workers, the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, for more than 45 years. Many workers also enter under the more recent Low Skill Pilot Project. Although these are programs for temporary migration, the majority of agricultural labour migrants have come to the same communities annually for eight months of the year, sometimes for more than 25 years, living and working alongside Canadians. Many of them are, in essence, permanently temporary.

Although there is a considerable literature on immigrant integration, it has largely focused on permanent immigrants (e.g., Biles, Burstein, and Frideres 2008; Frideres 2008; Li 2003; Reitz et al. 2009). Early theories typically claimed that the extent of immigrant integration could be measured by factors such as convergence with the average performance of nativeborn Canadians and their normative and behavioural standards (as indicated by key elements such as official language knowledge, socio-economic status or adopting ways of life similar to those of Canadians). Clearly, temporary migrants fall short when measured up to these indicators, particularly when they are applied to the lower-skilled migrants whose precarious employment and immigration status often contribute to social exclusion. Contemporary theories (which expand the concept to include such dimensions as economic, social and civic participation and a sense of belonging) are potentially more relevant but are rarely applied to temporary migrants.

The number of temporary workers coming to Canada has risen sharply, and some have a pathway to permanent residence. Is there a way to conceptualize integration for temporary migrants, and for migrant farm workers in particular? What implications might a clearer focus on their integration have for policies and programs?

In order to begin answering these questions, this study examines the structural and everyday realities of the streams of Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) operating in agriculture, drawing on a case study of Ontario. The study begins with background on the TFWP (with a focus on agriculture), including a summary of growth rates, countries of origin, demographic makeup and geographic distribution, as well as policy and rights frameworks. Following this is a short discussion of the concept of integration and its applicability to temporary migrants. The analysis then turns to the extent to which migrant farm workers are integrated into workplaces and local communities, drawing on empirical data from Ontario on such issues as access to health care and social inclusion. Building on this analysis, new ways of conceptualizing integration for temporary migrants are discussed further, and the Labour Migrant Integration Scale is presented as a potential measurement tool. Finally, the study proposes recommendations for policy and practice aimed at deepening the integration of migrant agricultural workers within Canadian communities.

Temporary labour migrants1 constitute a rapidly expanding segment of the Canadian workforce, from agriculture to information technology (IT), indicating a significant shift in Canadian immigration policy over the last several years. Increasing numbers of temporary labour migrants from developing countries take on low-skilled jobs, often in higher-risk industries such as agriculture and construction. Most of these lower-skilled workers enter Canada through the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) and the Low Skill Pilot Project (LSPP). In January 2011, the federal government introduced an agricultural stream into the LSPP, in what it claims is an attempt to bring labour market requirements for employers (such as demonstrating efforts to hire Canadians) and entitlements for LSPP workers (such as housing) in agriculture closer to those of the SAWP. Despite these intentions, the new stream effectively encourages the operation of two programs within the same sector, the same commodities and at times even the same workplace. Having two programs may further increase competition in the sector as employers search for the cheapest or least demanding workers, potentially driving wages and conditions down while pitting one group of workers against another based on gender, race or country of origin.

The TFWP has no cap on the total workers admitted, and numbers are largely driven by employers’ demands. Many agricultural employers, for example, turn to the most flexible labour source — foreign workers who will do jobs Canadians do not want to do — to provide them with a flow of labour on demand, with a tap that can easily be turned on and off. In Canada’s agri-food system, other factors driving this growth include demographic changes and the increasing globalization and concentration of agri-food markets that have consolidated farms and increased intensive agriculture (Hobbs and Young 2000; Preibisch 2007; Satzewich 1991; Shields 1992; Wall 1994; Winston 1992).

Canada’s history with agricultural labour migration dates back to the Second World War (Satzewich 1991). In the 1940s, international guest worker programs (including the USMexico Bracero Program) were spawned during the exceptional circumstances of war. In part to remain competitive with producers in countries using such schemes, Canadian farmers began to exert pressure for their own foreign worker program. Demands ramped up in the 1950s and 1960s in response to what employers claimed to be “exceptional” circumstances of industrialization, urbanization, increased agricultural competition and demographic change, in which not enough reliable domestic employees could be recruited to work under the difficult, demanding, low-paid conditions of agriculture (McLaughlin 2009). For a time, labour shortages were somewhat addressed through internal migration, largely by workers from Newfoundland and Quebec; these networks still bring workers to Ontario and British Columbia today, but on a much smaller scale (Hennebry 2006; Lanthier and Wong 2002; Wall 1994). In 1966, the Canadian government yielded to employer demands and the SAWP was born. The program began bringing workers to Canada from Jamaica in 1966, Trinidad and Tobago in 1967, Barbados in 1967, Mexico in 1974 and the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States in 1976 — under the same bilateral memoranda of understanding that still govern the program today. More than 40 years on, labour shortages, employers’ wishes and the perception that the tradition of Canadian agriculture (the core of which is the family farm) is at risk have led to an ongoing system of temporary agricultural migration in Canada.

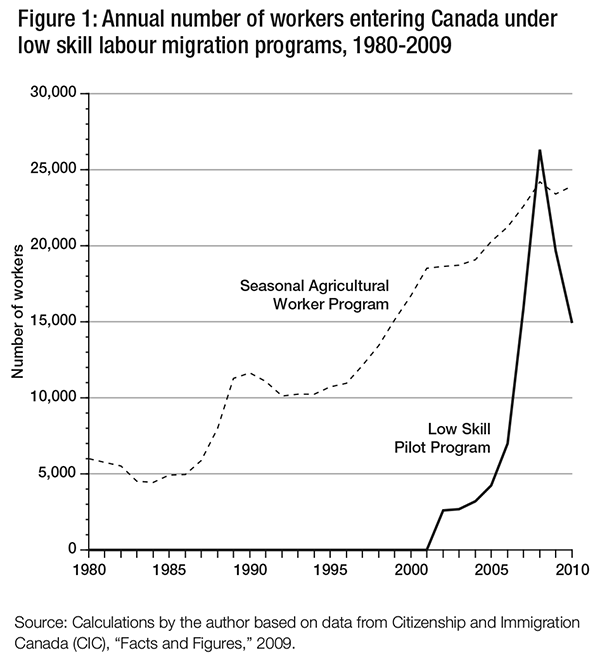

In 2006 for the first time, more temporary foreign workers (just over 139,000 of all skill levels across all sectors) than permanent economic class immigrants entered Canada. Since then, the pattern has continued (CIC 2010). In 2010, 182,276 temporary foreign workers entered, including 23,898 under the SAWP and 14,893 under the LSPP.2 Figure 1 shows two streams of lower-skilled labour migration programs.

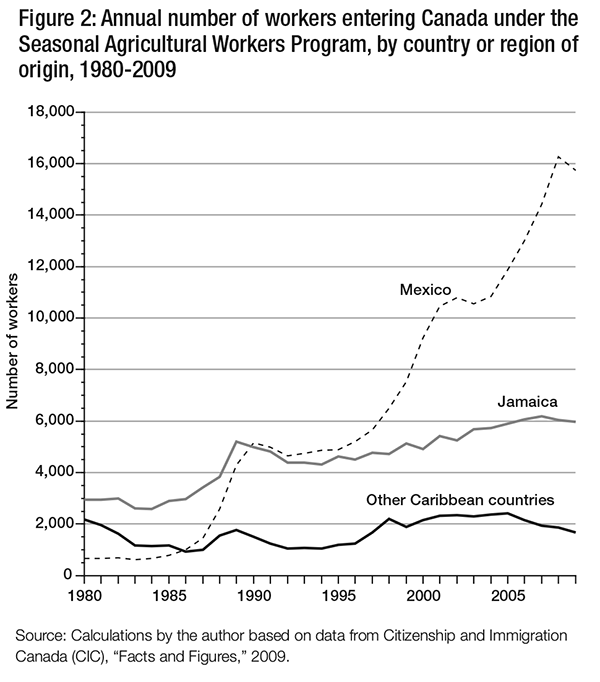

Before the introduction of the LSPP, the SAWP was the primary conduit for lowskilled temporary labour migrants to enter Canada. The number of SAWP workers from all countries entering Canada annually grew from 500 in 1974 to 23,898 in 2010 (CIC 2010). The number of SAWP entries from Mexico alone rose from just 203 in 1974 to 15,809 in 2010, with a total of 208,684 coming to Canada during this period (STPS 2010). Figure 2 shows the growth in the SAWP since 1980, by country of origin.

Interestingly, a majority of SAWP workers from Mexico are nominated workers: employers have requested them by name for the following season. In 2010, there were 12,339 named workers (STPS 2010). This means that nearly 80 percent of all SAWP workers from Mexico return for another season in Canada. These workers were employed on 1,488 farms in 2010, up just slightly from the number of such farms in 2009 (1,435) (STPS 2010). The number of employers involved in the SAWP has actually declined somewhat in recent years. For example, in 2003, 1,571 Ontario farms employed SAWP workers, and by 2010 there were 1,329 such farms (FARMS 2010). These numbers show not only that the majority of SAWP workers from Mexico return to Canada to work in subsequent years, but that most employers have been employing the same workers in the SAWP year after year.

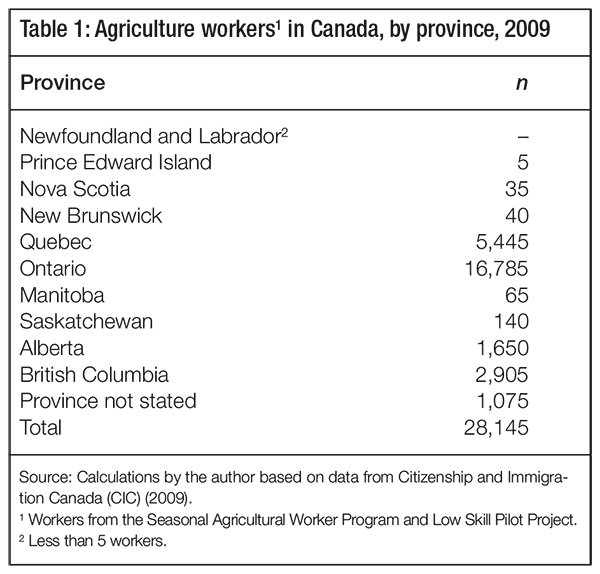

Most workers who enter under the SAWP are concentrated in Ontario. In 2009, there were 16,260 such workers in Ontario. The majority of migrant farm workers in Ontario are spread across rural areas, with the largest concentrations in the counties of Essex (4,047), Niagara (2,631), ChathamKent (1,199), Brant (967), Grey (711) and Simcoe (639), close to the towns of Leamington, Niagaraon-the-Lake, Brantford, Bradford and Simcoe (FARMS 2010). Of all SAWP workers from Mexico, 51 percent are in Ontario, 20 percent in Quebec and 19 percent in British Columbia; the remaining 10 percent are spread across the other provinces. Table 1 shows the distribution of agricultural migrant workers by province.

As for the LSPP, in 2009, 34 percent of the jobs under this program were in agri-food sectors, including agricultural and horticultural workers (5,060); food counter attendants, kitchen helpers, etc. (4,105); machine operations and related workers in food, beverage and tobacco processing (530); and labourers in processing, manufacturing and utilities.3 In 2009, 1,705 of these LSPP agri-food workers were in Ontario, up from 800 in 2005 (HRSDC 2009). Lowskilled migrant agri-food workers are now a significant presence in many local Ontario communities because of the SAWP and the LSPP. In Leamington, Ontario, in 2006, for example, 9 percent of all full-time workers were nonpermanent residents, primarily migrant farm workers (Thomas 2010).

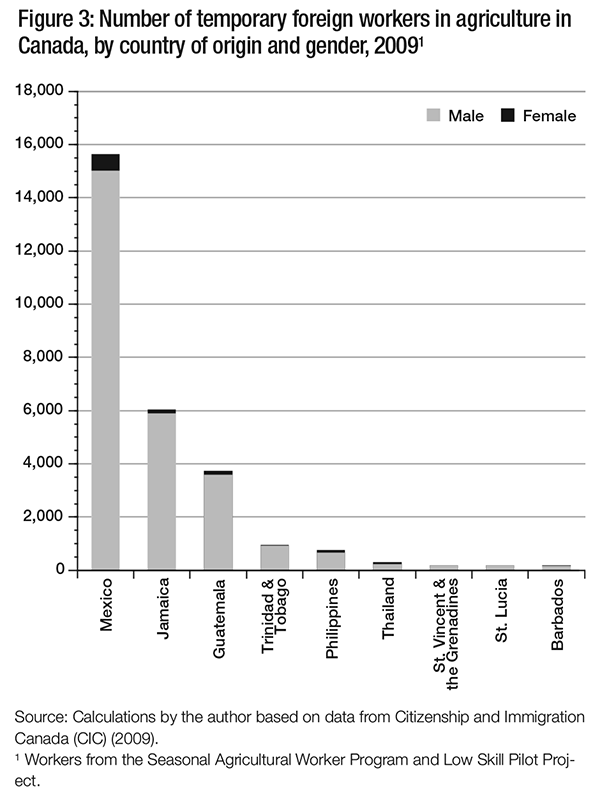

Most migrant farm workers are from Mexico and Jamaica, and they enter primarily through the SAWP. Under the LSPP, increasing numbers of agricultural workers are coming from new source countries, with Guatemala, the Philippines and Thailand being the top three countries of origin. Figure 3 shows countries of origin for workers in both programs.

Most Filipino and Thai workers are in Ontario; the majority of Guatemalan workers are concentrated in Quebec because of the role of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as well as the recent efforts at international recruitment by the Fondation des entreprises en recrutement de main-d’œuvre agricole eÌtrangère (FERME). In 2009, 3,750 participants came to Canada from Guatemala, working with 334 employers, mostly in Quebec (IOM 2008). The IOM has facilitated the migration of Guatemalan workers by providing recruitment, screening and predeparture services. FERME has now opened an office in Guatemala to directly recruit workers for employers, without the involvement of the IOM.

Although 34 percent of all temporary foreign workers are women, the vast majority of agricultural migrant workers are male; only about 3 percent of SAWP migrant farm workers and 4 percent of LSPP migrant farm workers are female. Even so, there has been an increase in the numbers of women in the SAWP: only 100 women participated on average throughout the 1990s, but 815 women did so in 2009 (CIC 2009).

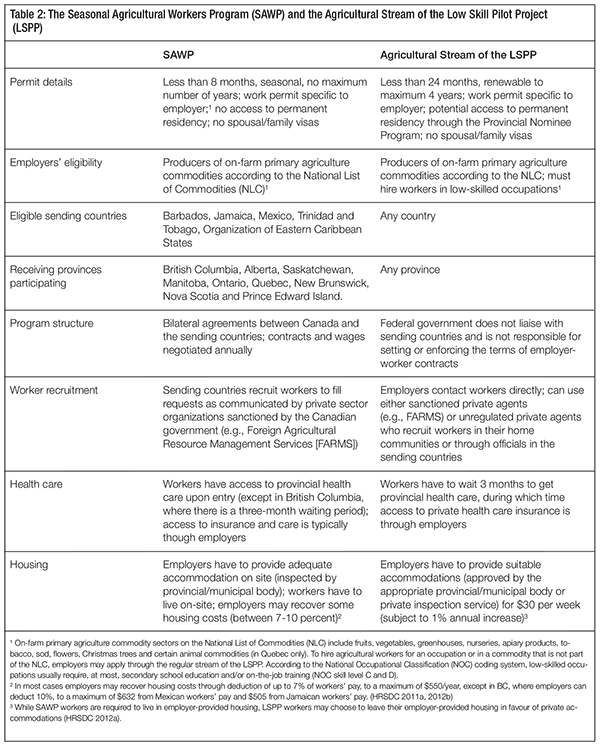

As previously noted, bilateral memoranda of understanding provide the framework for the SAWP. Participants are selected and screened by their own governments and work in Canada for up to eight months a year. Under the LSPP, workers are not seasonal; rather, they have work permits that are valid for up to 24 months, with a maximum of four years. Consular offices of sending countries play a significant role in the management of the SAWP, typically liaising with employers and workers, with the Canadian government and in some cases with provincial health care and insurance bodies. This is not the case with the LSPP to the same degree and sending-country representation varies. Employers are named on both SAWP and LSPP work permits. In the SAWP, transfers are typically initiated only by employers, whereas in the LSPP workers are typically left to locate another employer with permission to hire foreign workers. Typically such changes are made with assistance from FARMS (Foreign Agricultural Resource Management Services, a conglomerate of growers’ associations) and/or sending-country officials; Service Canada and Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) must also approve the change.

Migrants coming to Canada through either the SAWP or the LSPP do so without their families. Unlike the Federal Skilled Worker Program, neither of the two programs provides migrants with eligibility for visitor’s visas for family members or spousal work permits.

In order to meet the requirements of the SAWP, employers must pay the prevailing wage rate negotiated annually, provide transportation for workers to and from countries of origin and arrange basic medical coverage. SAWP migrant workers also receive supplementary medical insurance while in Canada; Mexican workers are covered for emergency medical, life, disability and dismemberment, through RBC (Hennebry 2006), and Jamaican workers get this coverage through a package arranged by their government (McLaughlin 2009). Access to provincial and private health care coverage is mediated by the employer, who must ensure that workers receive health cards and can have time off work and transportation to health facilities when necessary. The employer must also provide “adequate” seasonal housing to the workers that must be inspected by a licensed municipal housing inspector (typically prior to the arrival of workers). In most cases, the employer may recover part of the cost of housing by a deduction of up to 7 percent of workers’ pay to a maximum of $550 per year (in BC, 10 percent of pay to a maximum of $632) (HRSDC 2011a).

Employers and private sector recruiters play a more significant role in the LSPP, with no formal role for sending governments. The primary role for the Canadian government, through Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC), is to provide labour market opinions (LMOs), which are intended to determine the impact on the Canadian labour market of hiring foreign workers. A “positive” LMO effectively gives permission for employers to hire foreign workers (HRSDC 2011b). Employers recruit their own workers for the LSPP, typically through private recruiters or with the help of employer associations that provide a range of services such as advertising, screening, hiring, transportation, negotiation, labour market opinion consultation and work permit applications. Workers, usually assisted by recruiters or immigration consultants, then apply for a work permit with the named employer, which is subject to approval by CIC. These recruiters are not subject to federal-level regulation, and although there have been strides toward regulation in some provinces — most notably Manitoba — there are growing concerns that this lack of oversight leaves most temporary workers coming to Canada vulnerable to exploitation, extortion and abuse.

The Manitoba Worker Recruitment and Protection Act requires employers to register with the province before they can recruit temporary foreign workers, and it enables the province to monitor workplaces and penalize employers who fail to comply. It also allows the province to refuse or revoke a licence and to recover money from employers and recruiters on behalf of temporary foreign workers. No other province has implemented such a strong monitoring mechanism, but others have made some attempts at providing increased assistance for workers in difficult situations. In particular, Alberta has implemented the Temporary Foreign Worker Helpline and the Temporary Foreign Worker Advisory Office (TFWAO), which serve to connect workers with employment problems to the appropriate department or agency (Alberta 2011). However, the TFWAO acts merely as a referral service and does not offer direct advocacy or assistance to workers; its lack of regulatory teeth has been criticized (Alberta Federation of Labour 2009). A unique and important strength of the helpline is that it is a tollfree number available to people in most countries around the world.4

Compared with SAWP workers, LSPP workers can move slightly more freely within the labour market (both within and outside of agriculture), since they can apply for a change of status to their work permit if they manage to locate an alternative employer with permission to hire them. Enforcement of the terms of the employment contract, and typically of compliance with provincial and federal labour regulations, is complaints-based. Because workers may fear reprisals from employers, this means that little is done to address problems in the workplace and cases of abuse. A further weakness is that the LSPP explicitly excludes the federal government from the responsibility of ensuring that contracts meet federal requirements, of enforcing the terms of the contracts or of otherwise intervening in the worker-employer relationship (HRSDC 2011c).

Under the LSPP, workers are not eligible for provincial health care on arrival. Rather, for the first three months, employers must give workers access to a private health insurance plan; they must also register their temporary workers with the provincial workplace safety board (HRSDC 2011a). Employers in the LSPP are not required to provide housing for workers, unless they are in the new agricultural stream of the LSPP, under which employers provide housing to workers for a fee of $30 per week (subject to 1 percent annual increase). The housing does not have to be on farm sites (as does housing for SAWP workers). Table 2 summarizes the features of the two programs.

There is significant provincial variation in the administration of the SAWP and the LSPP, with varying degrees of involvement of different industry representatives, organizations and employers. For example, FARMS (the conglomerate of growers’ associations) plays an integral role in the everyday management of the SAWP in Ontario (facilitating employers’ requests for workers, providing transportation for workers, etc.), while sending countries recruit workers into the program. In Quebec, FERME has expanded its role and become particularly active in bringing in workers through the LSPP, largely from its international recruitment efforts in Guatemala.

Employment contracts for the SAWP also vary somewhat across provinces. The most notable differences are in British Columbia, where, for example, employers do not recover any transportation costs from workers and are permitted to pay a piecework rate (with a guaranteed minimum of $9.28 per hour). There is a three-month waiting period for access to the BC Medical Services Plan, and workers must have a work permit issued for a minimum of six months to be eligible for coverage. SAWP workers in Ontario are entitled upon arrival to health protections, such as Ontario Health Insurance Plan and Workplace Safety Insurance Board (WSIB) coverage, similar to those of other Ontarians. HRSDC requires health inspections of SAWP workers’ housing; in Ontario these are typically carried out by municipal authorities before employers receive permission to hire foreign workers, but in BC they are usually done by private contractors. There are also provincial differences with respect to rights and protections for migrant workers. For example, though the majority of temporary migrant workers are in Ontario, it is Manitoba that has begun to regulate recruitment practices, provide access to immigrant support services and give limited access to permanent residency through the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) (Manitoba 2008).

The long history of labour migration in Canadian agriculture might be read as an indicator that migrant workers have been significantly integrated into the agricultural labour market, yet research has shown that these workers’ lives are characterized by inequality and lack of freedoms when compared with those of their Canadian counterparts. In fact, early research on Mexican and Caribbean farm labour in Canada that focused on labour relations and structural inequalities demonstrated the uneven ways in which migrant labour is incorporated into the labour market (Satzewich 1991; Wall 1994). Since then, research has expanded to focus on agricultural migrant workers’ living and working conditions (Basok 2002; Binford 2002; Hennebry 2006, 2009; McLaughlin 2009; Preibisch 2004; Weston 2000), migrant workers’ limited rights (Basok 2002, 2003; Hennebry 2006; McLaughlin 2009; Preibisch 2004; Smart 1997; Verma 2003), impacts for sending countries (Basok 2000, 2002; Becerril Quintana 2011; Colby 1997; Verduzco and Lozano 2003), and globalization and changes in the agricultural industry (Colby 1997; Preibisch 2004, 2007). Generally, this research indicates that migrant farm workers are exposed to health risks through inconsistent and often substandard housing and face heightened workplace risks; they encounter barriers in accessing health care and compensation; and they are not sufficiently protected from rights violations.

Although research on the integration of migrant farm workers into Canadian communities is not extensive, two studies have looked at social inclusion and community relations. Preibisch (2003), in a report for the North-South Institute, explores the relationships between migrant workers, their employers and the rural communities in which they live. She finds that the majority of migrant farm workers remain invisible to most Canadians, in part because they work long hours in order to send more money to their families and in part as a result of their limited mobility. She concludes that this limited social interaction between migrant workers and the rural community gives rise to cultural misunderstandings, racialized stereotypes and, at its most severe, overt racism. Bauder et al. (2003) examine impacts of migrant agricultural labour on two small communities in Ontario: Delhi and Simcoe. They find that the impacts of foreign farm workers are profound, with grocery stores, banks, hardware stores, building material suppliers and restaurants benefiting from the seasonal presence of the foreign workers.

In a 2010 IRPP study, Nakache and Kinoshita assess the TFWP, ask whether economic considerations trump human rights concerns and examine government policies aimed at protecting these migrants. They argue that the short-term focus of Canada’s temporary labour migration policy is not going to help meet its long-term labour needs and is also unfair to labour migrants, who are unable to contribute to Canadian society even though they spend many years in Canada. They conclude that, while Canada does encourage the integration of highly skilled workers, it is largely indifferent to the needs of lower-skilled temporary workers.

As noted previously, the concept of integration has not been applied directly to the case of migrant farm workers in Canada. In order to do so, it is important to clarify what is meant by “integration.” Early theorizations of integration in Canada tended to adopt what Li (2003) considers a conformity model, whereby integration was assessed based on the extent to which immigrants conform with the culture and norms of the host society. Other conceptualizations of integration consider the parity (or otherwise) between immigrants and the Canadian-born population with respect to socioeconomic indicators. More nuanced theorizations recognize the economic, social, cultural, political and identity aspects of the concept, and view these as interrelated (Frideres 2008).

Recent research on integration in the European context is relevant for developing conceptualizations of integration for all newcomers, both temporary and permanent. Of particular value is the conceptualization of immigrant integration as a process through which “newcomers become capable of participating in the economic, social and political/civic life of the host country. Acquiring these capacities is not only the responsibility of newcomers: the host society and its governments must provide instruments and resources that will allow immigrants (and their families) to do so” (Joppke and Seidle forthcoming). Two aspects of this conceptualization relate to temporary migrants. First, integration is a process, though not one that inevitably leads to naturalization or citizenship; nor should citizenship be thought of as the principal tool for immigrant integration. Second, the integration process is a two-way street, with governments providing instruments and resources that assist immigrants in their efforts to integrate into economic, social and political life.

Integration of temporary migrants can indeed be understood as a process whereby these newcomers (like permanent migrants) participate in the economic, social, cultural and political aspects of Canadian society, yet with some important distinctions due to their “temporary” status. First, as already noted, integration of temporary migrants will not necessarily culminate in permanent residency or citizenship (although this may occur for some). Second, this process may not move forward consistently, and must straddle countries of origin and host countries, particularly seasonal migrants or workers who are subject to forced-return policies and must go back home for a minimum period in order to be eligible for more work permits. Third, some specific indicators of integration are arguably unique to temporary migrant workers — or at the very least are more important for them — such as whether they enjoy the same access to health care and social benefits and the same freedom of employment and residence as residents.

Another measure of integration is the extent to which labour force structures and workplace regimes for foreign workers are comparable to those for domestic workers (Werner 1994). Other indicators may be similar to those used to measure integration for newcomers more generally (such as community participation), but may be operationalized differently for this group. For example, membership in community organizations or clubs would not be an appropriate measure of social integration for temporary migrants; community engagement and outreach from community organizations might provide indicators.

Clearly, integration and inclusion can be experienced in very different ways in the everyday lives of temporary migrants in their workplaces and communities. Important to the examination of integration for migrant farm workers specifically is an approach that considers both the everyday experiences of inclusion and exclusion, and the structural factors that so significantly affect the integration of this group: namely, the legal frameworks and parameters of their work permits under the SAWP and the LSPP. The following section will draw on more than a decade of the author’s empirical research on Canada’s temporary migration programs operating in agriculture, with an emphasis on Ontario. This research includes qualitative interviews and ethnographic study with migrant farm workers in Ontario and in Mexico, nearly 600 standardized questionnaires with agricultural workers in Ontario,5 qualitative interviews with SAWP and LSPP workers and immigrant service providers and community groups in Ontario,6 as well as around 25 interviews with employers, representatives of private sector organizations and the IOM, and government officials from Canada and certain source countries.7

The analysis will concentrate on two main areas: how migrant farm workers’ status as temporary workers and the structures of the SAWP and the LSPP affect their rights and their integration into workplaces, institutions and society generally; and how migrant farm workers engage with the communities in which they live and work, with particular attention to community organizations that have emerged to support them.

It is like half of my life is here and the other half is there. (Mexican SAWP worker, Alliston, 2005)

We think that when we are separated, in this way, during eight months, from our family, well…in reality we are living our lives in halves. This is how I see it, because we can’t live completely when we don’t have either place. (Mexican SAWP worker, Bradford, 2003)

The life of a temporary agricultural migrant, particularly in the SAWP, can be characterized as a state of permanent temporariness — a transnational life of going back and forth, largely beyond the control of the worker, belonging neither here nor there. This section will examine how the structural frameworks of immigration and citizenship policy (the TFWP in particular) and the everyday realities of being permanently temporary influence migrant agricultural workers’ integration into Canadian society.

As noted previously, most SAWP workers from Mexico return to Canada to work year after year, and the vast majority of employers have been employing workers in the SAWP for many years. According to data from the Secretaria del Trabajo y PrevisioÌn Social (STPS), a Mexican government agency, 75 percent of all workers participating in the SAWP in 2010 had been participating in the program for 4 years or more, with 57 percent of workers participating for 6 years or more, and 22 percent participating for more than 10 years (STPS 2010). Among the nearly 600 migrant farm workers surveyed in Ontario, workers participated in the SAWP for an average of 7 to 9 years; many returned to Canada for upwards of 25 years (Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010). Though the majority of SAWP workers from Mexico are in the prime working age range of 18 to 45, over 3,000 workers participating in 2010 were over 45. Nearly 300 were over 55, and 119 were over 60. Many of the older workers have been coming to Canada since their 20s (STPS 2010). This means that many migrant workers have spent the better part of their lives in Canada, working on Canadian farms, shopping in local stores, going to local church services and so on.

These data clearly illustrate that the SAWP is a circular migration system, not merely a temporary migration program. It is important to make this distinction, since in Canada, highly skilled temporary workers will remain “temporary” for only a few years before gaining access to permanent residency or returning to countries of origin having gained Canadian work experience. Workers in the LSPP enter on work permits for up to 24 months and can stay in Canada to work only for a maximum of four consecutive years, after which they must return to their countries of origin for at least four years. The SAWP, by comparison, places no limit on the number of seasons that migrants may work in Canada, but they must return between seasons to their countries of origin. Therefore, the characterization of the SAWP as a “circular” migration system more accurately reflects the migrants’ cyclical and repeated presence in Canada over the long term, in contrast to the short, temporary periods in Canada allowed under other programs.

It is not surprising to find, then, that as workers spend years coming to Canada to work, many wish to have the opportunity to stay in Canada permanently. In the survey of migrant farm workers in Ontario, workers were asked whether they would be interested in applying for permanent residency if they had the chance. Over half of the workers surveyed from Mexico and Jamaica (60 percent) indicated that they were interested in permanent residency (Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010).

In addition to the lack of access to permanent residency, the SAWP has a number of structural particularities that affect workers’ ability to integrate. To start, recruitment practices and regulations mean that workers tend to be married with families that they cannot bring to Canada. Historically, recruitment patterns have favoured applicants with dependants over singles, and men over women; they have favoured small-scale farmers or farm workers, and applicants from rural and farming communities (Preibisch 2007). This is particularly the case in Mexico, where the selection criteria emphasize small-scale farmers with little or no education who are married with families (STPS 2006). These rules have a twofold advantage for the Mexican state: they target the poorest farmers, who have been displaced by NAFTA and other agricultural policies and economic changes in Mexico; and they ensure that remittances will be sent to families in Mexico, bolstering the economy (Hennebry 2006). For the Canadian state, the advantage is simple: migrants will have motivation to return home to countries of origin and will be less likely to overstay their visas or seek permanent immigration status. The fact that workers migrate without their families, moreover, means that they are more willing than Canadian workers to accede to employer requests to work longer hours and on weekends, and that they can live on farm sites in bunkhouses with other workers and are a readily available workforce (Basok 2002; Colby 1997; Hennebry 2006; Preibisch 2007; Smart 1997).

Interestingly, as noted earlier, the majority of migrant workers from Mexico participating in the SAWP are “nominated” workers, meaning that they are returning employees who have been selected by their employers. In 2010, there were 12,339 nominated return workers from Mexico, 78 percent of the total for the Mexico program (STPS 2010). This aspect of the program acts as a strong incentive for workers to aim for a good evaluation by employers, since renewal of employment (with this employer) is conditional on employers’ requests of workers by name; but because workers fear the loss of future employment, they are less likely to complain or report accidents or injuries.

Also, without any job security or independent appeals process, workers know that they can be fired and repatriated at their employer’s discretion, and this threat exerts effective control. As one SAWP worker explains, “We are always afraid of repatriation. The employers try to keep us intimidated, afraid of being sent home” (Mexican SAWP worker, Simcoe, 2008).

Language knowledge is commonly used as an indicator of integration, and for migrants it can be a first tangible step toward inclusion. Migrant farm workers who come predominantly from non-Englishand non-French-speaking countries, such as Mexico, come to Canada with minimal capacities in either of those languages. For many, the language barrier can be isolating and can serve a segregating or excluding function in the workplace. It can also limit workers’ ability to advocate for their rights and prevent them from accessing health care and participating in the community. In some situations, the lack of English can prove quite dangerous, since employers and supervisors typically give instructions or training (such as on pesticide use) in English. As one Mexican worker puts it, “Symbols and body language is our English and this is very dangerous” (Mexican SAWP worker, Leamington, 2008). Migrant farm workers cannot enrol in formal language training while in Canada, nor are they typically eligible to take language training services offered to newcomers, but many would like to. Of the Mexican workers surveyed in Ontario, 71 percent indicated that they would like to learn English while in Canada. This is not surprising since, for many migrant workers, greater safety, autonomy and responsibility at work and the ability to interact with the larger community are related to their fluency in English. For example, workers gave these perspectives:

The problem that I have is that I can’t communicate with them [Canadian workers], because they don’t understand me…and I don’t understand them either. (Mexican SAWP worker, Everett, 2005)

Sometimes…you can’t express an opinion about work…I don’t know, like how it could be faster or better or safer, but it is difficult without English. (Mexican SAWP worker, Bradford, 2004)

An accident I had — that supervisor that injured me with a forklift, he scraped my leg until it started to bleed through my pants…I never said anything to him because I could not speak English. (Mexican SAWP worker, Shomberg, 2005)

If you disagree with the boss or he says something or does something that you don’t like, what can you do? Personally I think that you can’t do anything. Because I can’t speak English, and probably if I do understand something that I don’t like, I don’t know how to respond to him and if I tell him in Spanish he’ll say “I don’t understand.” So we are left feeling uneasy…and they think I am not conforming. (Mexican SAWP worker, Bradford, 2003)

I want to learn English. In case I want to ask for something (if I want to get something like even a coffee), I don’t know how you would say that. Now I realize that I need English to…speak. If I don’t talk, I’m going to become a mute.

(Mexican SAWP worker, Everett, 2003)

On many farms, workers are segregated by country of origin or language, working only with others from the same country or those who speak the same language. Language knowledge is often used in the formation of workplace hierarchy: those who speak English are often trusted more and given greater responsibility or freedoms (such as supervising other workers or operating specialized equipment).

They tend to form their own little hierarchy system of, you know, who’s been there longer and who’s in charge [and] that kinda stuff. And language is basically the key, if you speak English, obviously, because I don’t speak Spanish.

(SAWP employer, Alliston, 2003)One guy — the guy we had last year — he is sort of the lead hand in that way because his English is the most fluid. He has become the in-between person, we give him the instructions and then he tells the guys what to do.

(SAWP employer, Shomberg, 2005)

In addition, migrant workers are often separated from Canadian workers. In Ontario, the majority of migrant farm workers surveyed indicated that they typically worked alongside other migrant workers, with less than 0.2 percent working alongside Canadian workers. In effect, the only role in which most migrant workers interact with Canadians is as subordinates; 75 percent said they had a Canadian boss (Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010). Moreover, employers often use country of origin and gender as a basis for selecting workers. Since employers are not provided with resumeÌs or the skill profiles of workers, they know nothing of the workers’ skills or experience when the migrants arrive; often the employers base initial decisions on which workers to employ on stereotypes or advice from other employers or workers. Employers often articulate their hiring preferences, their perception of workers’ capacities and the organization of the workplace in terms of race and nationality. In interviews, employers spoke of differences between the work of Mexicans and Jamaicans, or reasons for the selection of Mexican versus Jamaican workers, with reference to racial differences or stereotypes.

We had the option of going either Mexicans, Jamaicans or St. Lucians. I think we sorta picked Mexicans because…umm, I mean not that we were thinking of, you know, sort of a race thing, I think I was looking more for, umm, the fact that if you’re, if you’re from Jamaica and you’ve got family or friends in Canada, which there are a lot of, then the tendency is they’re gonna want to say, “Hey I wanna go and visit these people.” So yeah, the guys I know that have had Jamaicans, they’ve had problems. (SAWP employer, Bradford, 2004)

With the Mexicans, you don’t get the problems with the women and stuff, um, that you get with others, like with the Jamaicans…but with the Mexican program, you get some drunks. (SAWP employer, Alliston, 2004)

What has emerged over the last 45 years of these hiring practices in the SAWP is a highly racialized system of employment. These racialization processes, demonstrated by Preibisch and Binford (2007) (who documented the replacement of black Caribbean workers by Mexicans over the SAWP’s history because of racial stereotypes and the perceived controllability of the Mexican workforce), have been extended to the LSPP, where workers are threatened with replacement by workers from other source countries. Now that the LSPP includes workers from all countries, there are increasing levels of competition between different ethnic workforces, which further enhances the feeling among workers that they are disposable and interchangeable. An LSPP worker says: “Stop the threats from supervisors — physical and mental. Supervisors threaten to replace us with Cambodians if we don’t work hard enough. Employees are repatriated for reporting abusive supervisors” (Guatemalan LSPP worker, St. Thomas, 2008).

As Satzewich (1991, 51) notes, racialization can be understood as a mechanism that excludes people from full entry and participation in society. The structures of the SAWP and the LSPP serve this function by allocating migrant workers to jobs Canadians generally do not want, while creating structures that control migrant workers and separate them from domestic workers, and most fundamentally, by denying access to permanent residency and citizenship. Further, since these two programs operate in the same sector, in the same commodities, the heightened competition between them further fractionalizes the workplace by country of origin and perpetuates racial recruitment and replacement practices of employers.

Another important aspect of integration is workplace health and safety, and related access to Canadian health care and compensation systems. In a workplace well connected to its community, workers are healthy, do not face high levels of health risks and have access to health care. If particular minority groups or migrants have higher levels of risks and barriers to care, this may be a very important indicator of weak integration.

Farm work is dirty, difficult and often dangerous. All agricultural workers, both Canadian and non-Canadian, work long hours, doing physically challenging work in harsh environments. Both have access to provincial health care and insurance systems when workplace-related injuries or illnesses occur. However, mounting evidence indicates that migrant farm workers face greater risks than their Canadian counterparts, and face particular barriers to accessing health care and compensation — most notably fear of repatriation.

Research demonstrates that migrant farm workers face elevated health risks from factors such as exposure to dangerous pesticides and fertilizers without protective equipment, information or training (Basok 2002, 60; Bolaria and Bolaria 1994; Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010; McLaughlin 2009; Otero and Preibisch 2009; Verduzco and Lozano 2003); long hours of work without adequate rest (McLaughlin 2009; Otero and Preibisch 2009; Russell 2003; Smart 1997); exposure to heat and sun, airborne dust and animal-borne diseases (Basok 2002, 60); depression, stress, anxiety and other mental health concerns due to isolation and family separation (Basok 2002, 60,122; Binford et al. 2004; McLaughlin 2009; Mysyk, England, and Galleos 2008; Preibisch 2004); exposure to hazardous conditions causing work-related injuries (Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010; McLaughlin 2009; Otero and Preibisch 2009; Verduzco and Lozano 2003); inadequate hand-washing and food preparation facilities (for example, running water) (Basok 2002, xv; Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010; McLaughlin 2009; Otero and Preibisch 2009); unsafe transportation and/or lack of training and valid permits for vehicle operation (Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010); a lack of knowledge or understanding about safe work practices, rights and entitlements; and fear of reporting accidents and injuries (Basok 2002; Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010; McLaughlin 2009; Verduzco and Lozano 2003).

Additional risks arise from on-site living conditions, another factor unique to migrant farm workers, particularly in the SAWP. Features of their housing include lack of access to clean drinking water, lack of safe food storage (e.g., refrigeration), insufficient food preparation and cleaning amenities, proximity to pesticides and fertilizers, inadequate bathroom facilities, and improper management of food, household and human waste (Hennebry 2007; Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010; McLaughlin 2009; Otero and Preibisch 2009; UFCW 2002, 2005, 2006).

These deficiencies in housing and working conditions combine to create very specific vulnerabilities for migrant farm workers. Studies of Mexican workers (Binford et al. 2004) and Jamaican workers (Russell 2003, 82) found illness and injury rates of around 25 percent among migrant farm workers. Roughly 32 percent of workers in the Jamaican study reported a long-term illness as a result of illness or injury experienced while in Canada (Russell 2003). Despite these high rates of illness and injury, they appear to be underreported. Among migrant farm workers surveyed in BC, nearly half of the Mexican workers reported feeling that their employer never or almost never ensured their health and safety (Otero and Preibisch 2009). Preibisch (2004) found that many workers do not report a health problem for fear of repatriation, and when they do report it, it is not quickly addressed.

Since 2006, agricultural workers (including migrant workers) in Ontario have been covered by Ontario’s Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA). It is not clear, however, what changes to farm management and labour practices have been implemented, what regulatory measures will ensure compliance and to what extent the OHSA will have an impact on the health and safety of migrant agricultural workers, and on workers’ access to health care services. For example, a recent HRSDC-CIC compliance review of 241 employers in the LSPP found 30 were in breach of employment standards, despite the OHSA (Treasury Board of Canada 2010).

Numerous researchers and worker advocates conclude that migrant workers do not always know how to access health care and compensation systems and may not receive adequate treatment (McLaughlin 2007, 2008, 2009; McLaughlin and Hennebry 2010; UFCW 2005). Some researchers have also argued that migrant farm workers have less access to health and social services than Canadian permanent resident workers (Basok 2002, 2003). For example, unlike permanent immigrants, migrant farm workers do not have access to immunization and vaccination programs. Among the numerous barriers to health care access that make it difficult for workers to communicate problems or seek medical treatment are fear of loss of employment or pay and communication and transportation problems, including language barriers, poor telephone access and lack of safe and independent transportation (Hennebry 2009; Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010; McLaughlin 2009; McLaughlin and Hennebry 2010; Otero and Preibisch 2009; Preibisch 2003, 2007; Preibisch and Hennebry, 2011; Pysklywec et al. 2011; Verma 2003). Furthermore, unsafe transportation or lack of training or appropriate licensing poses heightened risks for migrant farm workers. Of the migrant farm workers surveyed in Ontario, nearly 60 percent had to be transported to work sites, nearly 50 percent said they were transported in vans, and more than 50 percent said there were not enough seatbelts for all of the passengers (Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010).

Employers’ mediation of access to health care and insurance represents a significant barrier for migrant workers. Almost 20 percent of nearly 600 Ontario migrant farm workers surveyed did not have a health card; 45 percent reported that their colleagues work despite illness or injury, for fear of telling their employers, and 55 percent reported working in these conditions themselves to avoid losing paid hours (Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010). In addition, there are transnational health implications of these barriers, such that when workers become ill or injured, they often do not receive adequate treatment. They have limited visas and depend on employers for housing, so they lack the support necessary to stay in Canada to receive care, investigations into their conditions and reassessment of their employment capabilities. Thus, they return home with their condition not fully diagnosed or managed (Hennebry 2007, 2009; McLaughlin 2007, 2009; Preibisch and Hennebry 2011). The experience of one Mexican worker while getting treatment demonstrates employers’ attempts to control, and the lack of support available for this worker from consular officials:

The doctor told me that the surgery was very delicate and that I have to take great care of myself. But since I already had problems with my employer, he didn’t allow any visits. He didn’t want anyone to visit me. He just wanted to have all the information about me for himself…Later on, the consulate called me, saying that they will send a paper with the employer so I could sign it. They said it was for the insurance, but I didn’t believe them since I witnessed how a girlfriend of mine was sent back to Mexico as soon as she left the hospital. I thought that I was going to get support from the consulate and it wasn’t true. As I said to the consul, you should let other organizations help you help migrant workers; it is a benefit for all of us involved. But the consul doesn’t want to let any other organizations talk to me, they want to do it all themselves and in reality, they cannot do it…I don’t want any other worker to experience what I experienced. (Mexican SAWP Worker, Cobourg, 2010)

In addition, the same barriers that migrant farm workers face to receiving health care, they also encounter when accessing provincial health insurance and compensation systems (such as limited literacy, awareness of rights, fear of reporting accidents or injuries). For example, a Worksafe BC study found that the claims rate among temporary foreign workers was 2 per 100 in 2006, compared to 3 per 100 among BC workers overall. Among SAWP workers in 2006, the rate was 2.2 per 100, compared with 3.6 per 100 in the industry as a whole (Bogyo 2009). McLaughlin’s research (2007, 2009) suggests that migrant farm workers face additional difficulties and complications related to the compensation system, even though workers, employers and physicians are all legally obliged to file a claim with the WSIB in the event of a workplace accident. Of the nearly 600 migrant farm workers surveyed in Ontario, the vast majority reported not knowing how to make a workers’ compensation claim (93 percent), make a health insurance claim (85 percent), or fill out hospital forms (92 percent) (Hennebry, Preibisch, and McLaughlin 2010). Research also shows cases of Caribbean workers who say their employer would not allow them to report an injury or illness (Downes and Odle-Worrell 2003, 96), while in BC, Fairey et al. found that farm workers “experience considerable pressure to not report injuries and lack understanding about their rights to workers’ compensation” (2008, 29).

Injured workers who are repatriated find that their difficulties continue at home, since communication between workers, government agents, medical practitioners and the WSIB can be complex and difficult, and the systems in place vary widely between countries (McLaughlin 2007, 2009). When the next season approaches, SAWP workers who go home injured cannot count on being nominated by an employer for a guaranteed return to Canada. Medical screening procedures in Mexico and Jamaica may also contribute to the exclusion of people from those countries from future employment opportunities. As they are unable to return to Canada, they cannot access the employment retraining opportunities that Canadian injured workers would have.

In sum, research reveals migrant farm workers have many specific vulnerabilities. If they are indeed encountering greater barriers to accessing health care and compensation than are their Canadian counterparts, then they are clearly not integrating with respect to access to the Canadian health care system or Ontario’s occupational health and insurance systems. Though the majority of research thus far has focused on SAWP migrant workers, it is likely that workers’ experiences in the LSPP are similar. In some cases, barriers may be greater for LSPP workers than for those in the more carefully managed SAWP, since LSPP workers must depend on employers for private health insurance during the first three months of their work permit. As both program streams continue to grow, access to health care and compensation will likely continue to be important indicators of migrant farm workers’ integration.

Social isolation and lack of transportation impact migrant workers’ sense of belonging and inclusion in Canadian communities. Many migrant farm workers have little involvement with Canadians within or outside the workplace and may be isolated even from friends and relatives who are also in Canada. Migrant farm workers typically live on farm sites (which is required by the SAWP), distant from population centres, and cannot visit others because they have no transportation or communication or because their work schedules are heavy. As one worker explains, “I do not go out to socialize often…I would like to see my cousin, but it is too hard…I don’t have a ‘ride,’ I mean I don’t have transportation. Also, I have not much free time. If I did, then I would go to church too” (Mexican SAWP worker, Schomberg, 2005).

In addition, SAWP workers do not always know in advance where they will be working while in Canada, and while here they have no means to contact or visit others. Said one worker, “Every year…the same…not knowing…come back, leave and go who knows where” (Mexican SAWP worker, Alliston, 2005). Another said, “I have a brother here, but I don’t know where he is…I have the phone number, I think. He is here in Ontario, but I really don’t know where. I called but no one answers” (Mexican SAWP worker, Cookstown, 2005).

For many workers, the separation from their families serves as a sharp reminder of their permanent state of temporariness and their outsider status. Together with their lack of access to permanent residency, it severely limits their integration into the communities in which they have lived and worked for many seasons.

What I lived there in Canada was very strong and hard for me. It was a sad period of my life because being away from my family, in a country that I don’t know, I don’t know the language. (Mexican SAWP worker, Cobourg, 2010)

Would like to have visitor’s visa to visit family and friends in Canada, even to stay an extra week when work is done…Why can’t we get visitor’s visa or permanent visas when we have proved how hard-working and dedicated after so many years of working for an employer — can we not earn points towards a visa? (Jamaican SAWP worker, Niagara-on-the-Lake, 2008)

When SAWP workers were asked about staying in Canada or feeling a sense of connection to Canada, most responded that they saw their relationships as temporary while in Canada. Workers generally indicated a lack of attachment to and integration in Canada. Many indicated they had few or no relationships with other Canadians, had no knowledge of Canadian culture and felt generally apart from society.

I do not know any Canadians, well, except you… (Mexican SAWP worker, Bradford, 2005)

Question: Do you feel close to Canadians? “Ah…no, not close, but I’ve worked with some coworkers…and we got along not very well but acceptable.” Question: Do you think that Canada has a special place in your heart? “With Canada…I don’t think so. In the States I worked for many years, and I did have something similar to what you are talking about…but I lived there all the time….Here, no not yet.” (Mexican SAWP worker, Everett, 2003)

I don’t want to stay here permanently because I do not know anything about Canada. We do not participate in the Canadian culture, all we do is work. I think that they live differently, but I am not sure how. (Mexican SAWP worker, Alliston, 2005)

Adding to the sense of isolation and lack of autonomy is the nomination process and the restrictive nature of their permits, which make transfers difficult and largely beyond their control. SAWP workers are not allowed to be transferred without obtaining approval from the liaison and/or the consulate, and the Simcoe Service Canada centre. Farmers can request particular SAWP workers by name and request workers through transfers from another farm, but the workers cannot choose employers or obtain a transfer at their discretion (FARMS 2012).

In addition, both SAWP and LSPP workers have little recourse when faced with poor treatment or contractual conflicts. The fear of repatriation or of loss of future employment is a strong motivator. Furthermore, migrant farm workers find their stay in Canada contingent on employers, with the constraints on their mobility and lack of access to permanent residency particularly frustrating.

The more recent LSPP migrant workers have similar complaints, sometimes aggravated by the fact that they leave behind families for longer periods of time than the SAWP workers, without the ability to leave between seasons and return (since they are not given multiple-entry visas) or to bring families to visit while in Canada. They may build relationships while in Canada for two to four years but then have to go back to their countries of origin for four years before they are permitted to return to Canada. The SAWP and LSPP workers interviewed expressed their consternation.

We have no rights — not allowed visits, even prisoners get visitors. We are always afraid of repatriation. The employers try to keep us intimidated, afraid of being sent home. (Jamaican SAWP worker, Niagara-on-the-Lake, 2008)

The worst bosses think that they are hiring slaves, but that’s not the case. When one breaks a contract, it is because one does not agree with the boss’s treatment towards us. But we never break a contract for no reason, and the consulate reminds us that we came here with a signed contract. They ask us if we know that we have a written contract and yes, I am aware of it, but I also know that we are human beings. If I don’t agree with the way I’m being treated, then I should be able to leave, I am not a piece of property. I think that I should be able to return to my country if I want to. (Mexican SAWP worker, Sutton, 2009)

The worst. I didn’t expect this. No protection (for workers). And we don’t understand why they wouldn’t give us status (i.e., permanent residency). They treat us like disposables. They can get rid of you when they want. We pay taxes, EI and CPP but then we are not entitled to all the benefits. I don’t understand why. (Thai LSPP worker, Leamington, 2011)

If integration into the labour market and into the workplace can be shown by equal labour force structures and workplace regimes for domestic and foreign workers (Werner 1994), then the racialized and gendered selection of migrant workers, the segregation of migrant farm workers from domestic workers in the workplace, and the structures of the SAWP and LSPP that place particular constraints on the autonomy and working conditions of foreign workers are clearly indicative of unequal labour market and workplace integration. In addition, as argued by Nakache and Kinoshita (2010), the TFWP puts up significant barriers to providing the same employment rights to foreign workers as to domestic workers, most notably the restrictive nature of the work permit and the weak enforceability of the employment contract (since the federal government has no authority to intervene as it is not a party to the contract). Without the right to vote or act collectively across all provinces, migrant workers are largely unable to challenge these realities or to advocate for their rights while in Canada (Sharma 2001; UFCW 2005). Moreover, migrant farm workers in the SAWP do not have access to employment benefits on par with Canadian residents. In particular, though these workers pay into the employment insurance system, they are eligible only for parental benefits, not unemployment coverage, since they are deemed ineligible once they return to their countries of origin.

Research on precarious employment and migration in Canada (Goldring, Berinstein, and Bernhard 2009; Vosko 2006; Vosko, Zukewich, and Cranford 2003) is relevant to this analysis. The term “precarious” has been used to analyze both migration status (Goldring, Berinstein, and Bernhard 2009) and employment status (Vosko 2006). The application of the concept to migrant farm workers is certainly appropriate, since both their migration status and their employment status are contingent and temporary — and, most importantly, they are tied together (McLaughlin and Hennebry 2010). Goldring, Berinstein, and Bernhard (2009) define precarious migration status as the absence of any of the following components typically ascribed to permanent residents (and citizens) of Canada: (1) work authorization; (2) residence permit (the right to remain permanently in Canada); (3) not depending on another person (e.g., an employer) to remain in the country; (4) access to social rights and services such as education and health care; and (5) being able to sponsor family. Migrant farm workers have access only to work authorizations, but even the work contract and their temporary residency are tenuous and depend on relationships with employers. Both SAWP and LSPP workers are typically unable to access permanent residency and have only limited and temporary access to health and social services. They are unable to sponsor family members and normally cannot even visit with family members during their stay in Canada because of logistical and visa restrictions (McLaughlin and Hennebry 2010).

Additionally, LSPP workers are now subject to the “four/four” rule. Recent amendments to the regulations of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act came into force on April 1, 2011, setting a maximum cumulative duration of four years of work in Canada, followed by a period of at least four years not in Canada before they can return. This move is specifically designed to keep low-skilled temporary migrant workers temporary, and “to signal clearly to both workers and employers that the purpose of the TFWP is to address temporary labour shortages” (Canada 2010). Evidently, Canada’s foreign worker programs are structured to ensure that lowskilled migrant workers, and agricultural migrant workers in particular, remain both precarious and permanently temporary.

Despite their temporary status, migrant farm workers have become a permanent presence in small-town Canada over the last 40 years. Every year, thousands of migrant farm workers arrive, filling the streets with bicycles, extending grocery store lineups and crowding around telephone booths waiting for their turn to call home. The majority of temporary migrant workers in Ontario are concentrated outside of urban centres. Each year, Ontario’s rural areas and small towns such as Bradford, Leamington and Simcoe receive about 30,000 temporary migrants.

Though temporary migration is indeed changing the visible landscape, it is unclear whether more meaningful changes have taken place that would indicate the integration of this circular and transitory population into the fabric of these communities. Ontario towns such as Bradford, Leamington, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Chatham and Simcoe have certainly experienced significant changes to their demographic makeup, particularly from April to November, as the migrant workers from non-European ethnic groups (in particular, Mexican, Jamaican and Thai workers) bring a new multicultural reality. Their long-term presence in these communities has also been stimulating the growth of businesses that cater to their needs, such as restaurants and bars like Tony’s Tacos in Leamington and Amigas in Simcoe; stores selling Mexican and Caribbean goods; Western Union outlets; and Spanish-speaking lawyers and other service providers. In Leamington, for example, there are about 14 Western Union agents, mostly located on the main streets where migrant workers shop on weekends (Hennebry 2008).

In this section, some of the integration initiatives that have emerged in communities in response to the growing presence of migrant farm workers will be profiled. Over the last decade, such projects have grown significantly, and have had a great impact on the experiences of many migrants. They demonstrate some of the positive actions aimed at encouraging the social integration of migrant farm workers in Canadian communities, despite the significant challenges and limitations they may encounter, ranging from lack of funding to racism.

Over the last decade, nongovernment organizations, churches, many businesses and service providers have begun numerous integration initiatives, which can be understood as initiatives or programs that serve to empower migrant farm workers or to encourage their active participation within or communication with a community. Their purposes range from human rights advocacy, health care and labour protection awareness to educational and cultural projects. For example, the United Food and Commercial Workers Canada (UFCW) union operates Canada’s largest association for agriculture workers, the Agriculture Workers Alliance (AWA), with a network of help centres across Canada in areas with high numbers of agricultural workers including Abbotsford, Kelowna and Surrey, BC; Portage la Prairie, Manitoba; Saint-Remi and SaintEustache, Quebec; and Bradford, Simcoe and Virgil, Ontario. Since opening the first centre in 1992, the UFCW and the AWA have assisted tens of thousands of farm workers with abusive employers, unsafe workplace and housing conditions, medical treatment and workers’ compensation claims, parental leave benefits, health and safety training, and accessing translation at hospitals, as well as supporting the rights of agricultural workers to form a union (UFCW 2011). In 2010, the UFCW started the Migrant Workers Scholarship program, offering 20 scholarships for the children, grandchildren, sisters, brothers, nieces and nephews of migrant workers.

Other groups directly address migrant agricultural workers and their rights. Most notably, Justicia for Migrant Workers (J4MW) has worked to assist workers in having a voice politically. J4MW is a community organizing collective that has worked with migrant farm workers in Ontario for more than 10 years (Justicia 2008). During this time it has been providing front-line emergency support to workers in crisis, lobbying governments and local communities and service providers to respond to the needs of workers in the local context, conducting workshops for workers on all issues pertaining to their rights and work in Canada, and assisting workers with human rights complaints. The bulk of J4MW’S work is to promote the voices, agency and leadership of workers in their own movement for the rights of temporary foreign workers in the country as well as for those of their families left behind. For example, on Thanksgiving 2010, a protest march from Leamington to Windsor was organized by J4MW to demand access to permanent residency and better rights.

Other organizations, though not created specifically to support migrant workers, have either expanded their reach to include this group or developed specific programs or initiatives to target it, often in collaboration with local communities. For example, Frontier College works with community groups to help them set up literacy programs in small towns such as Leamington. Frontier College offers informal literacy classes to migrant farm workers and new immigrants to the Leamington area for two hours a week. Over the last 110 years, Frontier College has recruited, trained and sent labourer-teachers to work and teach across Canada. They have worked on rail gangs, in lumber and mining camps, in prisons, in urban factories and in remote communities — and now they work with migrant workers in many of the same rural areas across southwestern and central Ontario. The labourer-teachers are placed in agricultural settings, on farms and in processing plants, and do the same heavy labour jobs as the other workers. In addition to the physical work, labourer-teachers volunteer their time to provide educational and recreational opportunities for their coworkers. These activities are determined by the interests of people in their workplace. For example, a labourer-teacher might help workers upgrade their English skills, instruct workers on the use of the computer or organize special events: a movie night, a sporting event, an outing to a tourist site. They give out information about workplace safety and procedures or provide peer counselling, mediation and contact with outside agencies such as doctors, dentists, hospitals and banks.

Other community groups have focused on particular groups of migrant workers in a given region, such as the Chatham-Kent Thai Outreach which is specifically aimed at supporting LSPP agricultural migrant workers from Thailand in that region. Enlace Community Link extend their support to Spanish-speaking Mexican migrant workers across southern Ontario through maintaining a calendar of events for migrant farm workers in southern Ontario and hosting events such as Migrant Worker Appreciation Day, held annually in Bradford in June; the Welcome to Migrant Workers event at the St. Mary Church in Simcoe; a bicycle rodeo at the arena in Virgil, a suburb of Niagara-on-the-Lake; and soccer tournaments in the Bradford/Newmarket area and Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Community churches and religious organizations have also been vital to the efforts to integrate farm workers into local communities. Most notable has been the work of KAIROS, Canadian Ecumenical Justice Initiatives, an association of 11 churches and religious organizations, which champions various human rights causes, including the rights of migrant workers in Canada. KAIROS focuses its education and advocacy work on improving legislation (both federal and provincial) so that workers have improved access to permanent residency and social services, improved labour rights, access to family reunification, and the ratification and implementation by the federal government of the Convention on the Protection of Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families. They have hosted large meetings across Canada of community organizations and advocacy groups that work with migrant workers.

The community church El Sembrador brings together Englishand Spanish-speaking parishioners from St. Elizabeth Seton, St. John Chrysostom and Holy Martyrs of Japan parishes. Its mission is to provide both spiritual and social support to the Mexican migrant farm workers who come to the Holland Marsh area each year. Parishioners visit farms in Bradford, East Gwillimbury and King Township, hold social events, help people find support for practical needs and assist with a weekly Spanish-language liturgy at local churches. El Sembrador’s mandate is one of social inclusion, calling on community residents to get involved: “With your involvement, we can do a better job of including our Mexican brothers and sisters in our parish and community” (El Sembrador 2011). The Diocese of London also provides outreach to migrant workers in the area of Leamington, Kingsville, Oxley, Pelee Island, Exeter, Bothwell/Thamesville, Blenheim and Ingersoll Deanery. Masses in Spanish are held in eight locations, as are socials and cultural gatherings such as celebrations of Mexican Independence Day. Though their outreach has been predominantly rural, they have also started to assist workers employed in urban, nonagricultural work. They have also begun outreach with Thai and Filipino migrant workers through community partnerships.

In some cases, community organizations have come together with an agenda to support migrant workers in their area. For example, the Community Legal Services of Niagara South has recently formed a partnership with members of the recently formed Niagara Migrant Workers Interest Group (NMWIG), which is made up of representatives of community organizations, health providers and volunteers in the region. The network aims to improve accessibility to services in Niagara and to assist workers who are pursuing legal challenges in order to ensure that workers are treated equally under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Other examples include the formation of a subcommittee bringing together community groups known as the Chatham-Kent Committee for Migrant Workers (CKCMW), whose mandate is to create a welcoming, supportive community for all migrant workers in ChathamKent. In other cases, there are less formalized outreach programs and initiatives aimed at supporting migrant workers in local communities. A notable example is the Caribbean Workers Outreach Program, a group of residents in the Niagara region — largely driven by the work of one very passionate person — who organize welcome events, social events and music concerts as well as giving health and safety information and support to workers in need.

The various nonprofit organizations and church groups have taken immense strides toward integrating migrant farm workers into their communities, but the ad hoc ways in which they have developed leave the support infrastructure in small-town Canada looking more like a patchwork of good intentions that may disappear from one year to the next due to lack of funding or political will.

The experiences of Brandon, Manitoba, could prove instructive for other small cities, towns and rural areas. From 2003 to 2007, the number of temporary foreign workers migrating to Manitoba doubled, from 1,426 to 2,878, and nearly half went to communities other than Winnipeg (Manitoba 2008). Responding to this influx, Brandon has developed an approach to settlement and integration that encourages collaboration and communication across sectors and bridging the community to employers, to plan for challenges and needs. For example, six employees from the largest employer of migrant workers in Brandon, Maple Leaf Foods, were assigned roles as Community Steering Committee liaison officers, to serve as a bridge between the company and the community (Moss, Bucklaschuk, and Annis 2010). In the early stages of this influx, service providers encountered significant challenges related to policy and program regulations based on status and immigrant category, which effectively denied services to temporary migrants. However, provincial policy adjustments have since enabled local immigrant service providers to increase support for migrant workers (Moss, Bucklaschuk, and Annis 2010).

Manitoba assumed control over settlement services not long after it launched its Provincial Nominee Program, allowing it to design and deliver services that more effectively serve the needs of recent immigrants, including temporary foreign workers (Carter, Pandey, and Townsend 2010). This unique approach has enabled Manitoba to better attract and retain immigrants, and to include temporary labour migrants across a variety of sectors and skill levels in this pool of potential immigrants — creating the conditions for better integration. Interestingly, Manitoba also provided a pathway to permanent residency through the PNP for roughly 500 temporary foreign workers at the Maple Leaf Foods plant in Brandon. Though the numbers are relatively small by national comparison, they represent a significant proportion of the approximately 3,000 temporary workers coming to Manitoba annually. More importantly, this move demonstrates the potential for such programs when applied to specific labour needs.

Surprisingly, Ontario has not adopted such an approach — to either its immigrant services or its use of the PNP — despite the large numbers of temporary labour migrants entering the province annually. In Ontario, most immigrant service providers are still not funded to provide support to temporary migrants.