Human rights were adopted as an explicit element of Canadian foreign policy in the late 1980s, part of the human rights/good governance/democratic development triad. In this paper Nancy Thede argues that despite this apparent recognition of the link between human rights and democracy promotion, Canada’s policies and programs – like those of most other Western countries – are not guided by a strategic understanding of the nature of this link. This lack of a theory of the dynamic relationship between human rights and democratic development results in democracy promotion activities that do not focus on human rights in a way that strengthens democracy. The paper proposes an understanding of democracy based on the reinforcement of human rights and democratic institutions and argues that in order to be effective, democracy-support activities must be guided by such a theory.

A second, but related, issue, says the author, is the selective approach the Canadian government has taken to human rights. She argues that despite its commitments as a signatory of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Canada has adopted a stance that is generally hostile to attempts to enhance the recognition and implementation of economic and social rights. In fact, one of the key shortcomings of new democracies is precisely that economic and social rights are poorly institutionalized. From the perspective of democracy promotion, therefore, unwavering support for the implementation and fulfillment of these rights should be a high priority. Although Canada is not alone in this situation, the Nordic countries have shown that it is possible, even within a liberal-democratic paradigm, to give greater support to economic and social rights.

The roles played by Foreign Affairs Canada and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) in policy and programming around human rights and democracy promotion are examined here. Only one CIDA program adopts a rights-based approach: though marginal, it illustrates that such an approach is feasible. Foreign Affairs Canada is shown to be consistently unwilling to support human rights instruments that protect economic and social rights or that promote their enforcement. This unwillingness apparently also extends to proposed new instruments for civil and political rights; this is the case with the debate on emerging transversal rights such as the right to democracy and communication.

The paper concludes that the weakness in Canada’s approach to human rights within its democracy promotion policies and programs undermines the country’s potential impact. One of the priorities for reformulating international policy should be to revisit and address these two central problems for Canada’s democracy promotion.

Over the past 20 years the promotion of democracy has become an increasingly important element in Canadian foreign policy. This is reflected in particular in the growing expenditure on technical assistance to encourage democratic development. This paper is part of the IRPP’s International Democratic Development research program, which assesses Canada’s policies and programs in delivering this kind of assistance. (For an excellent review of the evolution of Canadian democracy promotion policies, see Gerald Schmitz’s earlier paper in this series.) The objectives of the project are to establish how Canada can contribute most effectively to the collective international effort to assist democratic development and to determine best practices for delivery of Canadian assistance.

In its foreign policy statement of April 19 the Government of Canada reaffirmed its commitment to “assist countries to build the conditions for secure, equitable development by promoting good governance.” One of the principal instruments for doing this will be the provision of support to programs and projects that expand and strengthen human rights. In this paper Nancy Thede provides a critical analysis of the effectiveness of past Canadian policies to support human rights.

Earlier papers in this series have provided a context for assessing Canada’s democracy assistance policies. Dr. Thede’s is the first to focus on how these policies have been implemented. The aim in this and in other papers to follow is to encourage public discussion about the best means for Canada to contribute to international democratic development.

Human rights became an explicit element of Canadian foreign policy and development assistance priorities in the late 1980s, at the same time as, and in connection with, a concern with democratic transitions in developing countries.1 The Canadian approach to human rights in democracy promotion is similar to that of other Western countries in its general contours and its weaknesses, characterized by the absence of a theory of the relationship between democracy and human rights. Such a theory would, as I illustrate here, reveal the important role of economic and social rights in democratic development. The lack of a theory undermines the impact of democracy promotion programs. This is accompanied by a strong official bias against the justiciability of economic and social rights, and against emerging transversal rights (principally to democracy, communication and development). The bias against economic and social rights runs counter to Canada’s international human rights commitments and, at the same time, undermines democratic development.

This paper begins by setting out the major characteristics of the international human rights framework, then discusses a theoretical conceptualization of the relationship between human rights and democracy and goes on to identify the major problems of democratization as concern rights. Following an examination of the approaches of Foreign Affairs Canada (FAC) and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) – the two major government institutions involved in formulating and applying official policy on human rights in democracy promotion – the paper discusses the implications of the previously noted bias in Canadian policy. It ends with proposals to help rectify this situation.

The founding instrument of today’s international human rights regime is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted in 1948 as part of the process of constructing the United Nations; it was originally a central aspect of the UN’s mandate. The 30 articles of the UDHR include individual and collective civil, political, social, economic and cultural rights. Its underlying inspiration is triple: it recognizes first that these rights inhere in the human person (as opposed to the State); second, that all human rights are fundamental to the realization of human dignity; and third, that they belong equally to all persons by virtue of their very existence as human beings.

From the outset, the expectation of the drafters was that the UDHR would quickly be complemented by a binding treaty to be ratified by all member states of the United Nations. Cold War logic, however, dictated the division of the proposed treaty into two treaties, one concerning civil and political rights and the other concerning economic, social and cultural rights. Western countries were the principal advocates of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), whereas the Soviet bloc and the nonaligned group of countries supported the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, there has been movement from each of those camps to ratify both covenants. Of the 189 UN member states, 148 have now ratified the ICESCR and 151 the ICCPR. The significant exceptions today, aside from a number of very small countries in the Caribbean and Oceania, are several Arab countries (Bahrain, Brunei, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates), the Southeast Asian “tigers” (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore), Pakistan and Cuba. Although the US signed the ICESCR in 1977, it has never ratified it.

Other major international human rights treaties are the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). They have been ratified by, respectively, 169 and 174 states. Even countries that have refused to ratify one or both of the two original covenants have ratified CEDAW. Outstanding exceptions are the Holy See, several Islamic countries and the US – the latter signed in 1980 but has to date not ratified the convention. Clearly, ratification does not guarantee that the state will apply these instruments within its borders, but it is significant in that states that are party to the convention agree to submit to international scrutiny on that basis.

Canada has made an important contribution to the development of international human rights instruments. Canadian diplomat and scholar John Humphrey was one of the three original drafters of the UDHR, and Canada rapidly ratified each of the instruments. Having ratified them, Canada acquired obligations under the international human rights regime. These obligations include respecting, protecting and fulfilling the rights the instruments contain, ensuring a core minimum as concerns each right and engaging in international cooperation to realize them.

Each of the conventions is monitored by UN machinery created to that end. The Human Rights Commission, under the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), meets annually and is composed of some 50 elected state members. Seven treaty-monitoring bodies, composed of individual independent experts, are responsible for monitoring implementation of the various instruments (the most recent was created in 2004 to monitor the Convention on the Rights of Migrant Workers and Their Families).

The 1993 UN World Conference on Human Rights highlighted four principles that lie at the heart of the human rights regime: universality (rights belong to all persons), indivisibility (rights cannot be separated from one another), interrelatedness (rights impact upon one another) and interdependency (a right cannot be fully achieved without fulfillment of all other rights). The Vienna Declaration was adopted unanimously by the states, including Canada. These four principles should therefore be reflected in Canadian policy and programming on human rights.

The progressive drafting, ratification and entry into force of the different human rights instruments underline the fact that the international regime for protection of human rights continues to evolve. The types of rights specified in the instruments are often referred to as “generations” of rights. Civil and political rights have come to be called first-generation rights; economic, social and cultural rights, second-generation; and collective rights, third-generation. Although this division does not necessarily stand up to historical scrutiny,2 it does reveal strong ideological tension among the proponents of the various types of right.

The passing of the Cold War has unfortunately not closed the gap between the two major covenants. Rather, there is now a discernible gap between southern countries who support economic and social rights, and the United States along with a few allies (in particular, the United Kingdom and Australia), who oppose their further institutionalization; European Union countries often straddle the gap. I will come back to this issue, and to the arduous task of situating Canada’s stance, later in the paper.

Human rights have become an important component of multilateral and bilateral aid efforts. Bilateral aid programming in this area was generally carried out through NGOs and arm’s-length institutions during the 1980s. With the demise of Soviet influence after 1989 and the consequent depoliticization of this form of aid, human rights support was integrated into the broad category of democracy support. All Western aid donors – including, more recently, some southern and eastern European donors – have both bilateral aid programs and specialized institutions for democracy and/or human rights support. Most cast human rights as an essential trait of a democratic society but do not elaborate upon the nature of the relationship between human rights and democracy. Conley and Livermore aptly note, “As the Cold War ended and as ideological competition waned, the three grand themes of human rights, economic development and democratization gradually came together to form a more or less coherent policy framework. Donor governments and multilateral funding agencies began to explore both the theory and practice of all three areas more fully and to frame programmes supportive of all three areas, on the assumption that they constituted an integrated package” (1996, 29).

The United States has the most explicit formulation: human rights are considered to be civil and political rights; and individuals – especially those individuals organized as civil society – supported by those rights, are seen as the seat of resistance to an encroaching state (USAID 1998). Other liberal democracies subscribe more or less to this approach, with varying levels of accommodation of economic, social and cultural rights. A statement by the Development Assistance Committee of the OECD indicates, for example, that “the agendas for good governance, participatory development, human rights and democratization are clearly interlinked. They include elements which are basic values in their own right, such as human rights and the principles of participation” (quoted in Perlin 2003, 7).

In fact, the relationship between democracy and human rights is more complex than indicated by such official statements. In established democracies, human rights are historical and social constructions. They have been formulated, recognized and codified in a conflictual process initiated by emerging social actors. Such a process might be described as the mutual constitution of human rights and democracy. According to Habermas, “the principle of democracy can only appear as the heart of a system of rights. The logical genesis of these rights comprises a circular process in which the legal code, or legal form, and the mechanism for producing legitimate law – hence the democratic principle – are co-originally constituted” (1996, 121-2). Historically, the social struggle for rights has been the basis for the development of democratic institutions (representation, elections, property, security of the person), but rights are at the same time a constraint on those very institutions.3 Thus, while the two are mutually constitutive, they are in constant tension with one another (this is evidenced, for example, in regular court challenges to legislative decisions). Citizenship – understood here in its sociological sense, and not restricted to its legal criteria – is the driving force and the outcome of this process. It is the transformation of individuals and social groups into subjects of rights – in other words, citizenship is the mutual constitution of rights and of the subjects of rights.

Again following Habermas, a democratic legal order rests upon the recognition of the right to equal individual liberties (1996, 122). This, in turn, implies “basic rights to the provision of living conditions that are socially, technologically, and ecologically safeguarded, insofar as the current circumstances make this necessary if citizens are to have equal opportunities to utilize the civil liberties” (1996, 123).

Democracy theorist Guillermo O’Donnell describes the process of democratization as one in which power-holders are progressively obliged, however reluctantly or contradictorily, through the agency of contending social and political forces, to institutionalize political rights (1999). Seen from this perspective, the ruling elite is progressively made to realize that, in order to survive, it must broaden access to the political process and to economic and social benefits. The ruling elite thus reluctantly circumscribes – partially or completely – its own authoritarianism (or is forcibly replaced by actors more amenable to doing so).

Furthermore, O’Donnell describes the process by which there has historically occurred a mutual constitution of rights and of the individual rights-bearer within the liberal system – which by this very process has become a liberal-democratic system. Citizens use existing rights to expand the political sphere and to develop new rights; thus, according to O’Donnell, the legal backing and enactment of agency (the capacity of persons to individually and collectively influence the evolution of society) are central elements of contemporary democracy. In fact, however, in many new democracies the legal texture of rights (across territory and across social class) is uneven in that the actual quality of a right can differ according to the social and historical experience of a society, or a sector thereof. “Political citizenship may be implanted in the midst of very little, or highly skewed, civil citizenship, not to say anything of welfare rights” (O’Donnell 1999, 33). In such cases, agency is negatively affected (for example, by fear or destitution), and in this sense the ineffectiveness of civil citizenship eventually saps and undermines political citizenship in large sectors of the population, particularly among the marginalized or excluded. Despite this, however, the agency is stimulated by the development of a public sphere, the basis of which is “the universalistic assignment of political freedoms and the inclusive wager” (1999, 38, 40).

Historically, rights in western regimes were won by social movements,4 first the nascent bourgeoisie and later the workers’ movements. The tangible result of their struggles was the recognition of certain rights (at first – and mainly in Western countries – civil rights, and later political rights) for certain categories of the population (at first – and again, in Western countries – adult males, initially those belonging to the propertied classes, and later the entire adult male population). This ultimately led to the institutionalization of social and economic rights. But beyond this tangible result, the movement set in motion a double process: on the one hand, the constitution of a community of citizens (whose specific composition evolves over time to include social groups – women, indigenous peoples – that place their demands in the public sphere)5; and, on the other hand, the constitution of a set of democratic institutions in tune with the historical experience and period. It could be said that this situation reflects the social consensus of a given historical moment as to who is recognized as a citizen (that is, as a rights-bearer in the public sphere) and as to the limits of citizenship (that is, the specific rights that inhere in citizenship) – put otherwise, the consensus regarding the subject of citizenship and its object.

The adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 represented an important threshold, projecting this heretofore essentially domestic, Western consensus on civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights into the international arena, transforming these rights into baseline criteria for human dignity throughout the world. This quantum leap, however, side-stepped the internal historical development of numerous societies, particularly in the “developing” world, and froze a balance of power that had evolved in Western countries into a set of international legal norms. The struggle thus continues within all societies to secure and enhance the effectiveness of these internationally recognized rights.

A huge number of developing and former Soviet bloc countries have adopted the institutions of liberal democracy since the early 1980s. There is cause for reflection, however, as to the real nature of these transitions. Although their initial reaction was rather triumphant (encouraged by a superficial reading of the significance of criteria such as those published by Freedom House), analysts, activists and politicians alike are now attempting to decipher the specific characteristics of the transitions. Recent literature on democratic transitions has revealed two major interrelated problems. First, all recent democratic transitions appear to be truncated or partial in that participation in the political and public spheres is limited to a small urban elite;6 participation in the institutions of the new democracies continues to be exclusive of the majority of the population. Second, the effective exercise of citizenship, notably the exercise of civil rights, is restricted to a comparatively small circle of social actors. The formal institutions and rules of democracy are unevenly applied, thus excluding a large part of the population – often the majority. Be it for reasons of gender, ethnic identity or economic status, entire sectors of the populations of new democracies are virtually absent from that sphere (Thede 2002a). Economic and social inequality continues unabated. These two phenomena have led authors to qualify these systems variously as “low-intensity citizenship” (O’Donnell 1993, 1361-3), “disjunctive democracy” (Holston and Caldeira 1998), “uncivil democracy” (Holston 1998), “illiberal democracy” (Zakaria 2003) or “hyper-presidentialism” (Oxhorn and Ducatenzeiler 1998). The implications of these lacunae in terms of rights are evident: democratic transitions have institutionalized political rights, but they appear unable to guarantee civil, economic, social or cultural rights. The future development of certain states as democracies depends on overcoming this weakness.

To address the problem, it is therefore not enough to approach human rights and democracy as distinct characteristics of society. A clear strategy for expanding the access to, and effectiveness of, democratic institutions for the socially excluded in concrete societies must be at the heart of any attempt to promote or strengthen democracy. Such a strategy must resolutely strengthen and support social forces constructing effective rights and promote the reform of institutions in order to facilitate access for the excluded.

The analysis of the relationship between human rights and democracy shows human rights to be as crucial for equality of opportunity (the liberal-democratic view) as for democracy as social justice (the social-democratic view). As Pateman maintains, substantive autonomy of citizens is necessary for democracy, and this entails not only formal political equality but also access to education, health and cultural development (2002, 43). It is not possible to separate the implications for democracy of different types of rights along the classic civil-political versus economic-social-cultural fault line. In fact, the relationship is much more complex than is often assumed. In the case of truncated new democracies, mentioned earlier, lack of access to the political sphere is in large part – but not exclusively – a problem of nonrealization of economic, social and cultural rights (poverty, unemployment, poor health and education). But it is also related to the nonfulfillment of civil and political rights (unequal and discriminatory law enforcement or outright repression of opposition forces, for example). In each case, the degree of effective realization of rights determines the quality of citizenship.

The accent on human rights as a motor for the construction of democracy around the world has been an integral part of the emergence of a new world order since 1989. Indeed, human rights activists and movements were central actors in the fall of authoritarian regimes in the East and South in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Their demands for civil and political rights inspired Western donors to include human rights in the democratic development agenda, but without necessarily considering the meaning of the entire family of human rights.

Human rights were formalized as a Canadian foreign policy objective in Canada in the World (Foreign Affairs Canada 1995). The first official commitment to take human rights into account in foreign policy had previously come with the promise in CIDA’s strategy document Sharing Our Future (1987) to take the human rights record into consideration in determining which countries would receive Canadian bilateral aid. The government also agreed to create a human rights unit inside CIDA. It had earlier agreed to establish an arm’s-length institution to promote the development of human rights in response to a recommendation by the 1986 Special Joint Committee on Canada’s International Relations (the Simard-Hockin Committee) (Morrison 1998, 276). This commitment was made effective in 1988 with the adoption by Parliament of the law creating the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development.

Although some authors trace the influence of such concerns back to the 1940s (Roussel and Robichaud 2004, 152), concern for human rights and demands that they become an issue explicitly addressed by Canadian foreign policy were forcefully voiced by Canadian churches and solidarity organizations after the Chilean military coup of September 11, 1973. Those demands were taken up by opposition MPs in the House of Commons following individual initiatives in the form of private members’ bills presented by Conservative MP David Macdonald in 1976-77 and 1977-78 (Morrison 1998, 502). The 1982 report of the Subcommittee on Canada’s Relations with Latin America and the Caribbean was marked by controversy over the issue of human rights. The Simard-Hockin Committee report of 1986 unequivocally reiterated the 1982 subcommittee’s proposal to link official development assistance (ODA) to human rights performance and urged Canada to take a stand on the issue of the effects on human rights of the decisions of international financial institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In response, the government made some limited commitments related to human rights. Soon after came For Whose Benefit?, the report of the Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, which examined Canada’s ODA; the committee was chaired by William Winegard. Issued in 1987, the report presented numerous recommendations for focusing the aid program on development priorities and, like the previous reports, it urged allocation of ODA on the basis of a human rights assessment. The government response to the report, To Benefit a Better World, accepted the majority of the recommendations and paved the way for the 1987 CIDA strategy.

It took the fall of the Berlin Wall to make human rights an explicit policy and programming priority for the government. Prime Minister Brian Mulroney announced a stronger Canadian policy on human rights at the 1991 Commonwealth and Francophonie summits (Islam and Morrison 1996, 10). CIDA established among its interim priorities the support of human rights, good governance and democratic development (hr-gg-dd) and created a good governance and human rights policy unit in 1992 and a “thematic fund” for programming in this area in 1993. The 1995 report of the Special Joint Committee Reviewing Canadian Foreign Policy reaffirmed the idea that hr-gg-dd should be central to Canadian foreign policy. Canada in the World finally consecrated the shift away from sanctioning human rights violators (a position with which the government had never been comfortable) and toward an approach highlighting promotion of human rights in foreign policy.

Parliamentary committees continue to force human rights onto the government agenda, as witnessed by the recent debates over human rights in the context of the Free Trade Area of the Americas. When, in the late 1980s, the Canadian government finally agreed to implement a human rights policy in ODA (long after several like-minded governments, such as that of the Netherlands, had done so), the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War depoliticized discourse. Officials began to approach human rights and democracy as technical issues rather than as the conflictual processes they actually are.

Two institutions of the Government of Canada have responsibility for issues related to international human rights. Foreign Affairs Canada (FAC) deals principally with the policy and political aspects of international human rights, setting policy with respect to foreign countries and preparing Canada’s initiatives at the annual meeting of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) and its related bodies. The Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) develops concrete programming in countries eligible for official development assistance. The five categories of international human rights (civil, political, economic, social and cultural) are not approached as an interrelated whole by either CIDA or FAC, although CIDA does support programming that could be interpreted as advancing economic, social and cultural rights.

The International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development (ICHRDD), an arm’s-length institution, was created by Parliament in 1988 with a mandate to undertake programs in developing countries to help give effect to the rights enumerated in the International Bill of Rights7 and to assist democratic development. Its programs target areas crucial to human rights where official policy is often loath to tread. Its annual budget of under C$5 million was decreased somewhat over the years and was only increased in 2004. Although the approach adopted by the ICHRDD is potentially complementary to those of CIDA and FAC, the connection has been difficult to make in most cases (with the notable exception of women’s rights, for which CIDA is funding an ICHRDD initiative in Afghanistan). The ICHRDD, now known by its short name, Rights & Democracy, developed an innovative methodology based on human rights criteria and designed to assess the state of democracy in a given country with a view to producing democratic development programming strategies,8 but it was unable to arouse CIDA’s interest in collaborating on strategies emerging from the assessments. It is noteworthy that this methodology – developed prior to, and independently of, the International IDEA Democracy Assessment – is ultimately very similar in intent, approach and lessons learned.9 Canadian government officials participate actively in IDEA but have maintained their distance from the ICHRDD.

Two types of issue are relevant to an examination of human rights within Canada’s democracy promotion programs. The first concerns the overall Canadian foreign policy regarding human rights and the stances taken by Canada on international human rights questions. This falls principally under the purview of Foreign Affairs Canada (FAC). The second is that of the strategy regarding human rights within democracy promotion activities per se. This is largely within the domain of CIDA.

As noted earlier, in the post–Cold War phase, Canada has relied increasingly on promoting human rights and tended to abandon pressure tactics. While this promotional approach can strengthen actors within developing countries through financial and technical support, a similar tack in the diplomatic arena has proven much less positive. Indeed, it represents a retreat from the commitment to sanction violators (in a moral and political sense, not an economic one) on which the credibility of the international human rights bodies depends. Some reluctance is evident in Canada’s performance during its most recent stint as a member of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, for example.

This is not to intimate that promotion is not a crucial and necessary aspect of an official human rights approach. But it can be effective only to the extent that it is based on an analysis of the facts on the ground in terms of actual violations, their perpetrators, their victims and their causes. Unfortunately, as frequently witnessed in FAC policy documents on specific countries (for example, those presented at the annual FAC-NGO consultations on human rights), there is a tendency to defend incumbent governments and to underestimate or disqualify information from human rights NGOs in the field. Thus, despite the official affirmation that “Canada pursues state compliance with international human rights in venues such as the United Nations General Assembly and the Organization of American States” (DFAIT 2003, par. E1), this endeavour is systematically undermined by the refusal to analyze situations on the basis of international human rights standards. And it is aggravated by an overdetermination of this analysis by political considerations (as in the case of Palestine, outlined later).

At FAC, the Human Rights Unit coordinates the preparation of Canada’s position for the annual session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR), entailing, among other things, consultations with the NGO community on major human rights issues. Generally frustrating for all concerned, these annual consultations often amount to little more than confrontations of opposing positions, with little sense that the government position is being constructively influenced by the analyses of civil society, or vice versa. NGOs and human rights advocates often have the impression that the country assessments that inform FAC positions are biased toward foreign governments and the business sector, to the detriment of reports of human rights violations from grassroots organizations.

The positions put forward by FAC demonstrate an overwhelming concern with civil and political rights, to the virtual exclusion of economic, social and cultural rights. Despite the fact that Canada ratified both international covenants in 1976, it does not recognize economic, social and cultural rights as justiciable in the same manner as civil and political rights. In fact, in its internal affairs, as in its international policy, Canada does not give the recognition to economic and social rights it gives to civil and political rights: the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms does not include economic and social rights.

Two important biases are present in Canada’s approach to human rights on the international level, and they both inhibit its capacity to address democracy-building through human rights. One is the previously mentioned bias against economic and social rights; the other is an increasing tendency to align with the United States on key human rights issues. Especially in the post-9/11 period, one can discern the emergence of a new front of human rights hard-liners composed of the US, the UK, Australia and Canada. In a striking departure from its reputation as a middle power that often sides with the Scandinavian countries, Canada is now often in opposition to a large bloc of European Union countries and new Latin American democracies. I will describe this emerging alliance in relation to several key human rights issues: the optional protocol for the ICESCR, the World Summit of the Information Society (WSIS), the rights of indigenous peoples, the problem of Israel-Palestine, the ratification of the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), the right to development and the right to democracy.

The ICCPR is accompanied by an optional protocol, now ratified by 104 countries, that creates a complaints mechanism whereby individuals whose rights have been abused by a state may seek recourse through the body created to monitor that convention (the Human Rights Committee, in this case). An initiative is underway to draft a similar optional protocol for the ICESCR, thus giving economic, social and cultural rights a standing that resembles that of civil and political rights. An open-ended working group has been established by the UNCHR with a mandate to consider options regarding the development of such an optional protocol (Commission resolution 2003/18, Economic and Social Council decision 2003/242). Canada was originally reluctant to support this initiative, but in 2003 it agreed to participate in the working group. This was welcomed as indicating Canada’s support for this initiative. In January 2005, however, fears were confirmed that, given Canada’s reluctance to endorse economic, social and cultural rights, its participation would hinder the process of developing an optional protocol. At that meeting of the working group, Canada sided with the US, the UK, Japan and Australia in maintaining that no protocol should be developed. The vast majority of new democracies and European Union countries are, however, in favour of drafting the protocol. As it is put in a Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) discussion paper,10 in the context of the discussion on this proposed optional protocol, “Canada is also concerned that in the absence of consensus on the definition of economic, social and cultural rights, these rights would be open to interpretation” (DFAIT 2003, par. E3). This argument stunningly ignores the fact that civil and political rights are also “open to interpretation” – to wit, the ongoing debates on the right to democracy.

In recent years at the UNCHR, Canada has been the lead sponsor on several resolutions, all of which have been generally adopted by consensus. At the 2002 session, these were the resolutions on freedom of opinion and expression; the elimination of violence against women; the working group and the draft declaration on the rights of indigenous populations; the human rights situation in Sierra Leone; impunity; and the effective implementation of international human rights instruments. Presumably, these are the issues on which Canada feels most comfortable investing its political capital and energies. It is therefore striking to note that even on at least two of these priority issues Canada has recently contradicted itself.

Despite sponsoring the resolution on freedom of expression and opinion at the UNCHR, Canadian delegates to the December 2003 UN World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) were reluctant to insist that these and other relevant rights (such as freedom of information) be mentioned in the summit declaration on the pretext that it might inhibit recalcitrant countries from supporting the declaration.11

On this issue, Canadian policy has been inconsistent. Since 1994, delegates from the representative organizations of indigenous peoples around the world have been meeting with state representatives at the Working Group on Indigenous Populations, under the Sub-commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, which is part of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, in order to negotiate a declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples based on a draft prepared by a working group that included representatives of states and of indigenous peoples. The negotiations have been arduous, and to date only a few paragraphs out of a total of 45 have been agreed upon. The remainder were to be dealt with in 2004, the final year of the working group’s original mandate.12 The declaration is of enormous symbolic, as well as practical, importance to indigenous peoples, and they strove to obtain agreement within the UN Decade of Indigenous Peoples, which ended in 2004. Canada had generally positioned itself as receptive to the views and proposals of indigenous peoples.

At the September 2003 session of the working group, however, Canada made a strange departure from its previous stance. While progress was apparent in the general agreement reached on the issue of self-determination, on the thorny issue of indigenous lands, Canada backed an Australian proposal that ran counter to the emerging consensus supported by the Scandinavians and Latin Americans. The Australia-Canada proposal, supported only by Great Britain and the United States, undermined the draft text on land rights and had the effect of stalling the negotiations precisely when time was of the essence.

In September 2004, Canada made another about-face, now supporting a proposal of the indigenous representatives on the issue of self-determination while the US, the UK and Australia opposed it. Two factors seem to have influenced this change of posture.13 These factors – the Canadian legal framework and strong political will – can be seen to influence Canada’s stance on other human rights issues related to democracy.

Canada’s recent stance with respect to the problem of Palestine at the UNCHR also gives pause. At the 2002 session, Canada and Guatemala were the only countries to oppose a resolution led by the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) to send UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Mary Robinson on a brief fact-finding tour of the occupied territories. Canada was also one of only five countries opposing a Pakistan-led resolution on human rights in the occupied Arab territories, including Palestine. Such positions distance Canada from European Union countries and align it more closely with US positions (the United States itself was not a member of the commission in 2002). Canada has continued to adopt this type of position, again voting against a recent UN resolution on the rights of Palestinians (Toupin 2004).

The Government of Canada refuses to accede to additional international human rights instruments that codify economic and social rights. It has refused to ratify the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), despite having become a member of the Organization of American States in 1990. Official reasoning is that the international community already possesses many human rights instruments that are poorly implemented, and they should not be diluted with new ones. But many human rights experts are concerned that the government will enter into a hemispheric trading agreement without contributing to the provision of hemispheric human rights guarantees.

In a 2003 discussion paper, Foreign Affairs reviewed its position on the American Convention and related issues (DFAIT 2003). In response to the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade, and having organized consultations with independent experts, Foreign Affairs to all intents and purposes rejected every proposal made to it on human rights issues and reiterated its very debatable reasons for not acceding to the ACHR:

Increasing commitments to the OAS by ratifying the Inter-American Human Rights Convention [sic] and contributing financially to the inter-American HR system was also an option considered. However, Canada has not signed the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights. Canada has been subject to criticism by several non-governmental organizations. Many of the Convention’s provisions are problematic in Canadian law, including for example, the Convention’s establishment in Article 4 of the right to life “in general, from the moment of conception.” This is incompatible with Canadian legislation and safe-guards for women’s reproductive freedom. In addition, Canada’s efforts to protect vulnerable groups through legislation prohibiting hate propaganda and child pornography would be contrary to Article 13 of the Convention which prohibits prior censorship. (DFAIT 2003, par. E2d)

This is not the place to go into the details of this argument: its many misinterpretations have been dealt with elsewhere (see, for example, Rights & Democracy 2000). Human rights experts and women’s rights advocates have repeatedly explained to government officials that solutions exist that would allow Canada to ratify. The problem is clearly a lack of political leadership on this crucial issue. And, as Thérien, Hénault and Roberge point out, the fact that the most fervent supporters of democracy promotion in the hemisphere – the US and Canada – have not ratified the convention does nothing to remedy the gap between human rights and democracy promotion in the OAS agenda (2002, 422).

The proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) is a framework for liberalization of trade and services that pays no attention to human rights or democracy. The Government of Canada has been highly supportive of this US initiative, saving in extremis the meeting in Monterrey in January 2004, while at the same time being very reticent to strengthen the inter-American human rights machinery and, in particular, to commit to full Canadian participation in it. Whether or not the FTAA moves ahead and meets its original target deadline of 2005 (at the time of writing this seems unlikely), it is vital that the hemisphere’s human rights framework be reinforced by the adhesion of those countries that are not yet party to its basic instruments. In a context where Canada is moving toward greater economic and commercial integration with the rest of the countries of the Americas (with or without a multilateral agreement), a universal human rights system, backed by a regional human rights court, is crucial. Without it we will find ourselves living in a hemisphere where only commercial rights are justiciable. The rapidity with which Canada ratified the Landmines Convention and the Inter-American Convention against Terrorism indicates that political will is lacking in the case of ratification of the ACHR. Parliamentarians have been doing their part; now the government needs to give a signal.

Canada has consistently voted against resolutions concerning the right to development.14 This situation appears not to have evolved since Leslie Pal wrote, “Officials see the right to development as a potential argument by some Asian and African governments against the importance of traditional civil and political rights, and they also prefer to work with the functional division of labour within the UN system between human rights and economic issues” (1995, 197). Canada has also, together with fellow West European and Others Group (WEOG) members, opposed resolutions on structural adjustment programs and their (often negative) impacts on human rights.15 Canada was the only country to vote against a 2002 resolution on the right to safe drinking water and sanitation.

When questioned, government officials justify this stance on the basis of the idea that human rights should be attached to individuals and not to the State:

“Who is the obligation-holder of a right to development or a right to democracy?” they query.16 There is also a concern that the governments of developing countries could consider themselves authorized by such a declaration to demand development assistance from Northern countries.17 It is probable as well that the notion of countries having full sovereignty over their natural resources is unpalatable to Northern governments and corporations. More generally, however, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and former Supreme Court of Canada justice Louise Arbour charges that Canada does not even give legal and constitutional protection to economic and social rights within its own borders.18

“Right to democracy” is a term that has been used more and more frequently in rights parlance in recent years, in both academic and policy circles (see Ezetah 1997; Muñoz 1998). Ezetah contends that the right to democracy overrides customary international law: “Given that the right to democracy is an aspect of the peremptory norm of self-determination, all states have an obligation erga omnes [that is, opposable to, and valid against, the whole world and all legal persons, irrespective of consent] to protect the democratic character of [UN] member states” (1997, 509). Schraeder argues that the United Nations itself embodies the international acceptance of this democratic norm (2003, 26, 30).

The term “right to democracy” was used in two international rights documents: United Nations Commission on Human Rights resolution 57 in 1999 and the Inter-American Democratic Charter of the OAS in 2001. Its career was brief, however, and subsequent resolutions on the same subject at the UNCHR were titled Promoting and Consolidating Democracy. Canada put a statement of interpretation on article 1 of the Inter-American Democratic Charter, asserting that it should be considered a political statement with no legal weight. Furthermore, the evolution of the discussions on this theme at the UNCHR has led to the formulation of three distinct sets of resolutions on democracy and human rights. One deals with democracy principally in terms of civil and political rights and is sponsored by WEOG and several new democracies in Latin America and the former Soviet bloc. A second is sponsored by the non-aligned group of developing nations and is titled Strengthening of Popular Participation, Equity, Social Justice and Non-discrimination as Essential Foundations of Democracy. And the third, also sponsored by the nonaligned group, is called Promotion of a Democratic and Equitable International Order. The second and third of these are ardently opposed by WEOG, principally due to their insistence on economic, social and cultural rights.

The justifications advanced by the Government of Canada for its stance on the right to democracy have to do with its reluctance to treat economic, social and cultural rights as equal to civil and political rights. The explicit reasoning often used by FAC human rights officials is that Southern countries may be attempting, through the wording of the resolutions (especially the resolution on the right to development and the resolutions on global democracy), to introduce new interpretations of existing norms and to undermine civil and political rights protection. There is an expressed aversion to any wording that alludes to collective rights.

Three observations can be formulated on the basis of this overview: Canada shows consistent bias against treating economic and social rights as equal to civil and political rights; a strong political will can quickly resolve deadlocks in Canadian positions on human rights issues; and Canada’s positions on sensitive human rights issues are bending toward those of the United States since 9/11. All of these issues affect Canada’s democracy promotion policies and programs. I argued earlier that the development of democracy requires strong development of economic and social rights – this is one of the imperatives in new democracies. The Canadian government is loath to undertake any engagement that could lead to financial claims against it, whatever its existing commitments in international human rights terms.

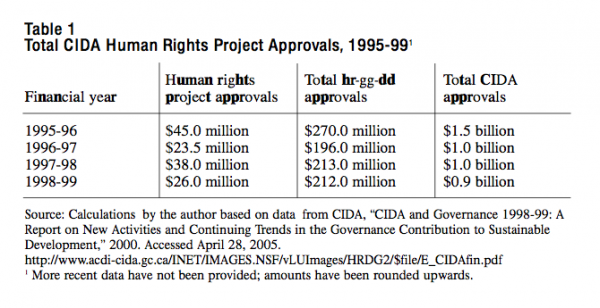

The Canadian International Development Agency designs and implements programs to support human rights and democratic development in developing countries. It is difficult to quantify Canadian ODA allocated to human rights programs. CIDA has published a single report on its hr-gg-dd approvals and disbursements covering the fiscal years 1995-96 to 1998-99, although its Web site promises reports for 2000 and 2001 as well. The report, titled “CIDA and Governance,” divides the projects into five categories: human rights, democratic institutions and practices, public sector competence, civil society and political will of governments (CIDA 2000). “Public sector competence” received for the period 1995-96 to 1998-99 over one-third of approvals by amount, with human rights and civil society each receiving under one-sixth.19 These statistics must be viewed with some caution, however, since a single project may touch on several themes but be only listed under one theme. It should be noted also that for this period annual CIDA disbursements amounted to 40 to 50 times the total budget of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development.

Human rights programs within the agency account for a small percentage of its total budget, as seen in table 1.

The most complete statement of the official understanding of human rights and their relationship to democracy is contained in the 1996 document Government of Canada Policy for CIDA on Human Rights, Democratization and Good Governance.20 This document treats its three components – human rights, good governance, democratic development (hr-gg-dd) – as parallel aspects of sound development, and there is no discussion of any relationship between them. It simply states that “together, they create the framework of society within which the development efforts of its members can be effective and sustainable” (CIDA 1996). Although it has its merits (for example, its definition of “civil society”), the CIDA policy treats human rights simply as a necessary aspect of a democratic society.

After its short-lived career – from 1993 to 1998 – as hh-gg-dd, CIDA’s programming on democracy and human rights was neatly subsumed under the functionalist heading “governance.”21 This is manifest in the September 2002 CIDA policy Strengthening Aid Effectiveness, which describes gender, human rights, democratic development and rule of law as subsumed under “governance issues.”

CIDA aims to include human rights as an aspect of all its development programs. “CIDA seeks to enhance respect for human rights as the foundation of equitable and sustainable development. This includes integrating human rights into development programming…The Agency has identified the following priorit[y] for the next three years in the area of governance: increase integration of human rights principles in development programming” (CIDA 2003, 41-2). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has initiated a more ambitious effort by agreeing to base all its programming on human rights (see UNDP 2003b). The UNDP undoubtedly has some way to go in order to make this decision effective, but it has begun to produce analyses and tools to facilitate implementation (for example, UNDP 2003a). These demonstrate that the UNDP does have a theory of the relationship between human rights, democracy and development. CIDA has not travelled as far along this path. The sectoral action plans for CIDA’s Social Development Priorities of September 2000 in its four areas of programming (health and nutrition, basic education, HIV/AIDS, child protection) all mention human rights as an aspect of their strategy, but only one – the Action Plan on Child Protection (June 2001) – adopts human rights as a strategic framework for programming. In this case, the strategy is based on the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This is an inspiring example of the potential strategic value of taking a rights-based, as opposed to a needs-based, approach to development programming. Its human rights lens leads the action plan to position children as “protagonists” and as “agents of social transformation” rather than as passive victims or beneficiaries. As well, the action plan explicitly sets out the difference between a needs approach and a rights approach.22 Based on a rights analysis, it focuses on “the most marginalized girls and boys who often experience exploitation, abuse and discrimination and who require special measures to support their development.” Honing this approach to develop a strategic focus, it prioritizes the issues of child labour and children affected by armed conflict (CIDA 2001).

It is not clear why such rights-based strategies have not been developed for the other three priorities or for the overarching areas of gender equality and human rights/governance/democracy. In contrast, the Action Plan on Child Protection demonstrates that such an approach is not only feasible but provides its participants with a sharper strategic focus and greater empowerment.

In general, though, both FAC and CIDA use a shopping-list approach to democracy, positing that a series of characteristics, or building blocks (democracy, respect for rights, accountability), are necessary. This approach does not allow for devising a strategy, because it provides no understanding of the dynamic interrelationships among the components. It ignores the fact that human rights and democracy are mutually constitutive phenomena. The compartmentalized approach to human rights and democracy in Canadian government policy ignores the complexity and the conflictual nature of both human rights and democracy, casting them as end products and unrelated principles.23

How do Canada’s approach and programs compare to those of other members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)? Do they reflect an overall trend among donor countries, or is this stance specific to Canada or a subgroup of countries? The following overview of official policy statements on human rights and democracy in official development assistance will shed some light on these questions.

An examination of the Web sites of the British Department for International Development (DFID), the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the French Direction générale de la coopération internationale au développement (DGCID), the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, the Norwegian Agency for Development (NORAD), the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) and Dutch development assistance24 reveals the following:

United States, Great Britain, France and Germany: USAID, Britain’s DFID, and France’s DGCID, unlike CIDA, do not set out specific strategies or programming approaches for human rights.25 USAID organizes its work around the issues of governance and civil society and treats human rights as a subsection of its approach to rule of law, itself a subsection of governance (USAID 1998). As for the DGCID (a section of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs), its overall objectives are “la lutte contre la pauvreté, le développement durable, et la bonne gouvernance.” Human rights are mentioned only in passing, under the sectoral heading “Favoriser l’État de droit et les libertés publiques.” The Web site does indicate, however, that FRF474 million (approximately C$100 million) was spent on human rights projects in the year 2000. A study of France’s support to democratic development in Africa reveals that France is concerned with a limited range of issues, related above all to the administrative capacity of the state apparatus (Banégas and Quantin 1996).26 The German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development has the most explicit approach to human rights of all members of this group: its overall policy focus is on sustainable development. Within that area, debt relief is a specific priority, and human rights is mentioned as part of that initiative. The Web site for the ministry indicates that DM200 million is spent yearly on human rights projects, over and above the amounts spent by the six political foundations also supported from the ODA allocation; the total is thus much higher than that of similar CIDA allocations in absolute terms, but lower in proportion to the total aid budget.

Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands: The Nordic countries put greater emphasis on human rights as a specific area of programming. Norway gives it the highest profile, with its Ministry for International Development and Human Rights, within which “peace, democracy and human rights” is one of six focus areas. Human rights is one of five key principles guiding development cooperation, and specific mention is made of the right to development as a framework for assistance. Sweden’s SIDA sets out “human rights and democracy” as a sectoral area of programming and states that it considers the three distinct groups of rights (civil/ political, economic/social/cultural, collective) to be not only universal, but interdependent and interrelated. However, SIDA does not go so far as to endorse the right to development. In the Netherlands, the Constitution itself enshrines human rights, and human rights and democracy are objectives of foreign policy. The Dutch government was among the first to introduce a coherent human rights policy document, in 1979, and in 1983 the Advisory Committee on Human Rights and Foreign Policy was created (it has now been replaced by the Permanent Commission on Human Rights within the Advisory Council on International Affairs). Human rights and democracy are part of the larger foreign policy objective of peace and security. An explicit aspect of Dutch development cooperation is the enhancement not only of economic progress but also of social and economic rights.

Each of the countries discussed here has also created arm’s-length foundations specifically dedicated to the promotion of human rights as an aspect of democracy (Great Britain, the United States, France, Germany) or to human rights per se (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Holland), similar to Canada’s ICHRDD. Except for the German ministry, none of the official agencies has published a report on the amounts of ODA provided to human rights and democracy assistance, as CIDA has done.

In comparison with other bilateral donors, therefore, CIDA provides more specific, publicly available information on its human rights activities, although Norway’s NORAD and the Netherlands ministry offer greater clarity in terms of the integration of human rights within overall development priorities. Only Norway explicitly endorses the right to development as a basis for official development assistance. All of the agencies define human rights in terms similar to those of CIDA and FAC by simply indicating the international instruments and affirming that human rights inhere in the individual by virtue of her existence as a human being. Most affirm respect for human rights as a necessary characteristic of a democratic society, but none sets out a theoretical basis for the relationship between human rights and democracy.

The manner in which the place of human rights and democratic development are defined within the overall foreign policy and ODA priorities places Canada closer to the first group of countries than the Nordics – a group with which it has often had affinities in the past. But the real point here is not that Canada does things better or less well than other donor countries. It is the similarities among all these policies that are striking, not the differences. None of the approaches outlines an understanding of the dynamic role of human rights in developing democracy, and most – except those of Norway and the Netherlands – sideline economic and social rights to concentrate on civil and political rights.

The bias in favour of individual/civil-political rights on the part of the Government of Canada resolutely ignores the fact that individual rights are only obtained and rendered effective through the following collective means: identities and mobilizations (Oxhorn 2003). The apparent anomalies in this bias are support for women’s rights and the rights of indigenous peoples, but upon examination it is evident that the position of Canadian foreign policy in favour of these collective rights applies principally to civil and political rights, not economic and social entitlements. In CIDA’s Policy on Gender Equality, women’s equality, both economic and social, is addressed under every one of the six program priorities except hr-gg-dd (1999, 13).27 Such an approach constitutes a violation of the guarantees of nondiscrimination and equality of the exercise of rights, as a group of experts on women’s rights recently pointed out. On the issue of substantive equality, the group asserted: “Economic, social and cultural rights must be interpreted and implemented in a manner that ensures to women substantively equal exercise and enjoyment of their rights. Substantively equal enjoyment of rights cannot be achieved through the mere passage of laws or promulgation of policies that are gender-neutral on their face. Gender neutral laws and policies can perpetuate sex inequality because they do not take into account the economic and social disadvantage of women; they may therefore simply maintain the status quo. De jure equality does not, by itself, provide de facto equality” (Aurora et al. 2002).

The civil-political and individual rights preference informing Canadian policy on human rights prevents that policy from addressing the role of processes to enhance the establishment of human rights in concrete societies and, in turn, the contribution of these processes to the development of democracy. In failing to see the interrelated struggles for democracy and human rights as collective social processes that address multiple and intricately intertwined objectives (economic, social and cultural, as well as civil and political), Canadian policy and programs may actually undermine the development of democracy. In many cases, by basing support on a formalistic or descriptive approach to democracy, Government of Canada programs – albeit unwittingly – enhance the control of elites over the political sphere and process, thus accentuating the truncated nature of new democracies and, hence, excluding large parts of the population from effective citizenship.

Numerous authors have commented on the neo-liberal bias present in the Western democracy promotion programs of the 1990s.28 If that bias was problematic for democratic development in the 1990s, an additional hurdle is arguably emerging in the post-9/11 policy context. Indeed, not only are Western governments – Canada included – not moving toward more a coherent integration of human rights with democracy, but they are also orienting policy toward a more regressive and restrictive conception in which democracy, development and human rights are subordinate to an overarching security logic. The recent “triple D” (defence, diplomacy, development) approach promotes greater integration of development and foreign policy with security concerns. On some of the current issues defining the increasing north-south divide, Canada has sided with the United States and against the vast majority of developing countries, and even many European countries.

If the Canadian government is to demonstrate a real commitment to promoting democracy, beyond the highly appreciated international role of Elections Canada,29 it must address human rights as a force that can generate and sustain democracy. The translation of this conceptual position into policy would mean a commitment to human rights not solely as a moral principle,30 but also as a primary motor for developing democracy. It would logically lead to the acceptance of the contested notion that international human rights law has a status of primary international law with which other international agreements have to abide.

It is admittedly difficult to assess the results of support to democratic development in general, and to human rights efforts in particular. Developing democracy is an extremely long and complex process. Changes cannot be measured from one year to the next. Neither can visible changes be attributed to a single factor or actor, much less to the efforts of external actors providing modest financial, technical or political support.

There have been numerous attempts over the past 20 years to develop statistical indicators for measuring human rights progress, and they have rightly aroused serious debate.31 None has received generalized or official approval. Statistical measurement in this field is fraught with pitfalls and cannot produce a detailed qualitative analysis for each case (see Thede 1999, 2000, 2002b). Results-based management methods have been introduced in CIDA programs since the mid-1990s. The inappropriateness of this approach for democratic development and related activities, including the promotion of human rights, is forcefully and accurately argued by Gordon Crawford (2003). Unfortunately, perhaps, assessing progress in democratic development and human rights is as complex and demanding as those processes themselves.

Support for human rights from agencies of the Government of Canada is undeniably useful to the organizations and institutions receiving it, whether it be financial support (principally through CIDA) or political support (mainly through FAC). But the contribution of that support to strengthening democracy is arguably accidental. With no explicit theory of the relationship of human rights to democracy there can be no real strategy. More to the point, perhaps: without an analysis of the problems encountered in new democracies there can be no strategy that works. Therefore, the choice of recipients of such support can only be – at best – intuitive and unsystematic. The tendency to support mainly elite organizations and institutions – whatever their political stance – reinforces precisely the negative tendencies of new democracies, and it is the principal product of the absence of theory and strategy.

Two characteristics of Canadian policy in this field have serious negative implications for democracy promotion. First, the bias toward civil and political rights to the near exclusion of economic, social and cultural rights is in violation of Canada’s international commitment to the indivisibility of the entire family of human rights. It also reinforces exclusion – particularly, but not only, in contexts of democratic transition. Second, support for the US position on issues of flagrant human rights abuse (as in the case of Palestine), and issues relating to security and the economic agenda, indicate that Canada is backing further and further away from a position that recognizes human rights as an overarching commitment for all states. Given the central role of rights processes in developing and institutionalizing democratic states and societies, this trend should be of major concern to all those committed to strengthening national processes of democratization through international means.

Canada has been adopting positions on human rights problems that are deepening, rather than closing, the north-south divide. If it is to contribute to strengthening multilateralism, Canada must revise its short-sighted opposition to economic, social and cultural rights and to the emerging transversal rights. It must make a serious attempt to address the fundamental shortcomings of new democracies by considering the role of human rights in the democratic process. What, then, would it entail for Canada to take the human rights framework as a basis for its policy and programming strategy? Creative examples are afforded by DFID (2000) and CIDA’s Action Plan on Child Protection (2001). Both demonstrate the benefits of such an approach in terms of policy coherence and strategic focus.

The term “human rights framework” refers, on the one hand, to the major international human rights treaties and, on the other, to a series of principles derived from, or underlying, those treaties. These principles are intuitively derived and can differ from one source to another – DFID, for example, defines them as participation, inclusion and fulfillment of obligation (2000, 7). A readily applicable framework for policy and programs could be devised on the basis of the three key principles of participation, nondiscrimination and accountability, and the four emerging human rights standards (availability, accessibility, appropriateness and adaptability).32 The principles imply the following: nondiscrimination (no person may be deprived of rights for reasons linked to gender, class, or ethnic or religious background); participation, inclusion and equity (the international human rights instruments understand all individuals as agents having the same rights);33 accountability, rule of law and transparency (rights imply obligations and duty-bearers who are held to account through specific mechanisms).

These principles and standards provide a dynamic guideline for designing and assessing policies, programs and strategies for democracy as well as for economic and social development. Canada should follow the lead taken by UNDP, the Netherlands, Norway, DFID and CIDA (with its child protection strategy) and take a human rights approach with all its international policies and programs.

A second measure to enhance Canada’s democracy promotion would be to create an advisory council on democratic development and human rights modelled on the Human Rights Advisory Council of the Netherlands. It should be composed of independent Canadian experts on human rights and democracy drawn from areas of academia and civil society active in democratic development. Its mandate should be to advise the Government of Canada on improving and refining policy in this field.

Some analysts argue that Canada’s national interest has been radically transformed by the advent of a unipolar world. According to them, Canada should no longer attempt to promote multilateralism but rather should accommodate US policy choices. This approach seems contradictory, however, for Canada’s interest can only lie in the emergence of a rules-based international system. Such a system, in order to function, must be a multilateral one. Canada’s long-term interest cannot lie in accommodating a relationship with the United States that depends solely on the balance of forces imposed by the superpower.

This new order puts a potentially contradictory emphasis on political and economic liberalization. Those who emphasize the latter make much of the need to construct a predictable, rules-based framework for investment in this context. However, from the perspective of political liberalization, promoting human rights and democracy is very much a part of building a predictable political environment on a world scale. Rights-based democracies are upholders of rules and a predictabl e legal and political framework, domestically and internationally. It is in the interests of Canada and other established democracies to support the development of full democracies – democracies that strive for institutionalization of the full range of rights – and the strengthening of a rules-based international system. Moreover, Canada must creatively address the post-9/11 challenges on the basis of strengthening international human rights norms, particularly as they relate to democracy.

Human rights are international rules – rules designed to ensure the human dignity of every person born on this Earth. They are an essential part of a predictable, rules-based international system. Canada’s national interest lies in helping to ensure that those rules are clear and impartially applied. In an epoch of globalization and extreme interdependence of nations and economies, it is ever more crucial that those rules pertain equitably to all. If not, those excluded from the benefits will ensure that no one can enjoy them.

That is not to say that Canada does not have to adapt its policies to the new world context. It does. It must move beyond the outmoded Cold War logic that has informed its human rights policies. The existence of two opposing political camps dictated the confrontation between proponents of civil and political rights on the one hand and advocates of economic, social and cultural rights on the other. The imperative for that division is long past. It is time for Canada to revamp its foreign policies for human rights in order to eliminate false distinctions and to reflect the interdependence of all rights: civil, political, economic, social and cultural.

I am indebted for their insightful comments and criticisms of an earlier draft of this paper to Brian Tomlinson, Gerald Schmitz, Kathleen McLaughlin, Max Cameron, Gerd Schönwalder and Phil Oxhorn. George Perlin made numerous valuable comments to various versions of the paper. My thanks are also due to two anonymous reviewers chosen by the IRPP.

Arbour, Louise. 2005. “De la charité à la justice: La pauvreté et de grossières inégalités continuent d’exister dans notre arrière-cour.” La Presse (Montreal), March 5, A24.

Aurora, Sneh, et al. 2002. Montreal Principles on Women’s Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Montreal: Rights & Democracy. Accessed January 14, 2004. www.ichrdd.ca

Banégas, Richard, and Patrick Quantin. 1996. “Orientations et limites de l’aide française au développement démocratique. Bénin, Congo et République centrafricaine.” Special issue, Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d’études du développement: 113-33.

Beetham, David. 1999. “The Idea of Democratic Audit in Comparative Perspective.” Parliamentary Affairs 52, no. 4: 567-81.

Canada. Department of Finance. 2005. The Budget Plan 2005. Ottawa: Department of Finance.

Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). 1996. Government of Canada Policy for CIDA on Human Rights, Democratization and Good Governance. Ottawa: Canadian International Development Agency.

–––.1999. CIDA’s Policy on Gender Equality. Ottawa: Canadian International Development Agency.

–––.2000. “CIDA and Governance 1998-99: A Report on New Activities and Continuing Trends in the Governance Contribution to Sustainable Development.” Accessed April 28, 2005. https://www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/INET/IMAGES.NSF/vLUImages/HRDG2/$file/E_CIDAfin.pdf

–––.2001. CIDA’S Action Plan on Child Protection: Promoting the Rights of Children Who Need Special Protection Measures. Ottawa: Canadian International Development Agency. Accessed February 19, 2004. www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/childprotection

–––. 2003. Estimates. Canadian International Development Agency 2003-2004 Estimates. Part III: Report on Plans and Priorities. Ottawa: CIDA.

Conley, Marshall, and Daniel Livermore. 1996. “Human Rights, Development and Democracy: The Linkage between Theory and Practice.” Special issue, Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d’études du développement: 20-35.

Crawford, Gordon. 2003. “Promoting Democracy from Without – Learning from Within,” part 1, Democratization 10, no. 1: 77-98.

Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT). 2003. “Enforcement of International Obligations: Environment, Labour, Human Rights, Cultural Diversity.” Accessed April 22, 2005. www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/tna-nac/IYT/toc-en.asp

Department for International Development (DFID). 2000. Realising Human Rights for Poor People. Accessed February 19, 2004. https://62.189.42.51/DFIDstage/Pubs/files/tsp_human.pdf

Ezetah, Reginald. 1997. “The Right to Democracy: A Qualitative Inquiry.” Brooklyn Journal of International Law 22, no. 3: 495-534.

Foreign Affairs Canada (FAC). 1995. “Canada in the World: Canadian Foreign Policy Review.” Accessed April 28, 2005. https://www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/foreign_policy/cnd-world/menu-en.asp

Graf, William. 1996. “Democratization ”˜for’ the Third World: Critique of a Hegemonic Project.” Special issue, Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d’études du développement: 37-56.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Translated by William Rehg. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Holston, James. 1998. Citizenship in Uncivil Democracies. New York: International Center for Advanced Studies, New York University.

Holston, James, and Teresa P.R. Caldeira. 1998. “Democracy, Law, and Violence: The Disjunctions of Brazilian Citizenship.” In Fault Lines of Democracy in Post-transition Latin America, edited by Felipe Aguero and Jeffrey Stark. Coral Gables, FL: North-South Center Press, University of Miami; Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

ICHRP. Forthcoming. Doing Good Service: Local Government and Human Rights. Geneva: ICHRP.