In this paper Lisa Sundstrom reviews the records of Canada and several other Western donor countries in promoting democracy, and some of the lessons learned from these experiences. She compares the democracy assistance approaches of the two largest donors, the United States and the European Union, and two European bilateral donors with democracy assistance budgets similar in size to Canada’s: the Netherlands and Germany. Professor Sundstrom proposes a few principles by which Canada might choose to allocate its democracy assistance around the world, allowing us to work in the areas where we have the greatest expertise, while remaining responsive to local contexts in countries that are aid recipients.

In an organizational sense, the donor community in Canada should strive to coordinate democracy assistance and share information among donors more effectively to allow them to specialize, minimize duplication and learn best practices. This would enable donors to avoid reinventing the wheel with each new program or in each country they work in. We must take care in this process, though, not to create a rigid, centralized institution that would sacrifice the flexibility and accessibility of Canadian democracy assistance by creating unwieldy new levels of bureaucracy, or that would raise barriers to the fruitful integration of democracy assistance programs with other kinds of development aid efforts.

However, the more pressing task in terms of Canada’s foreign aid policies is to place a real emphasis on democracy – in a broad sense, the meaningful participation of citizens in governing themselves and the realization of the necessary rights to do so. In Canada’s International Policy Statement (IPS), democratization is mentioned rhetorically as an area of sectoral focus for Canadian assistance in the future. Yet the specific criteria, as stated in the IPS, for choosing development partner countries are not well suited to a democratization agenda and do not mention democracy as a goal at all. In order to place a meaningful Canadian focus on democracy assistance, we must set relevant criteria in our foreign policy guidelines, taking into account that the stated priorities of poverty reduction and democratization will lead us to select different groups of aid recipient countries. Setting appropriate criteria will allow Canada to decide upon a group of “democracy partner” countries where we can best target Canadian democracy assistance to have a noticeable positive impact on democratic outcomes.

This is the fifth in a series of papers the IRPP has commissioned as part of its research project to assess Canada’s role in international assistance to democratic development. The objectives of the project are to examine how Canada can contribute most effectively to the collective international effort to assist democratic development and to determine best practices for delivery of this assistance.

In “International Assistance to Democratic Development: A Review,” a working paper that introduced the project, I pointed out that assistance in this area poses distinctive challenges that the entire community of international donors has not yet satisfactorily dealt with. Gerald Schmitz discussed the origins and evolution of Canadian policy in the context of these challenges. Subsequently, David Gillies explained the changes in donors’ thinking about the relationship between economic assistance and political development, and the relationship’s implications for donor policies and programs. In her paper, Jane Boulden explored the evolution of international efforts to promote peace, with an emphasis on the growing interest in what some see as the responsibility of the international community to intervene in failed or failing sates. For her part, Nancy Thede provided a critical analysis of the effectiveness of past Canadian policies to support human rights.

The International Policy Statement of April 2005 reaffirmed Canada’s commitment to be an active participant in the delivery of this kind of assistance. Yet, as Lisa McIntosh Sundstrom points out here, important questions remain about how democracy assistance fits into our international assistance policy as a whole, how we should organize its delivery, what forms it should take, and what criteria should be used in deciding to which countries it should be directed.

In discussing these questions, Professor McIntosh Sundstrom has provided a valuable context for other papers that are to follow in this series.

Canada’s role in support of democratic development overseas has been timid and small, but where it has been attempted, recipients of Canadian assistance have generally come away with positive impressions and an increased capacity to strengthen democracy in their local contexts. As other IRPP authors have noted, Canada does have a positive role to play in promoting democracy around the world (Axworthy and Campbell 2005, 2-3; Schmitz 2004). Most observers of democracy assistance maintain that such programs, when carried out effectively, can eventually have important results that encourage democracy in transitional regimes (Carothers 1999, 2002; Henderson 2003; Mendelson and Glenn 2002).1 The key task before the Canadian government is to render that role distinctive, clear and less hesitant.

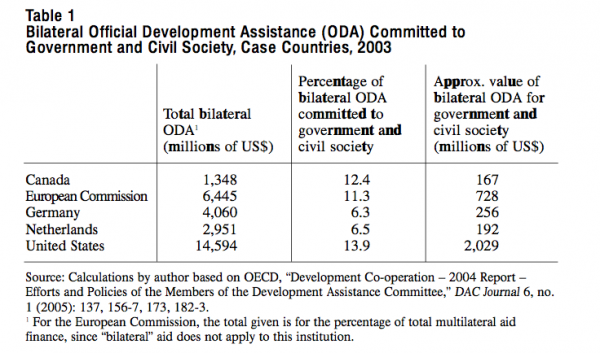

The federal government has a fairly small budget for overseas development assistance (approximately US$2 billion in 2003), currently under the auspices of CIDA. According to the Organization for Economic Development and Co-operation (OECD), funds devoted specifically to human rights, democracy and good governance (HRDGG) constitute only a small fraction of that total budget (12.4 percent of bilateral aid in 2003) (see table 1).

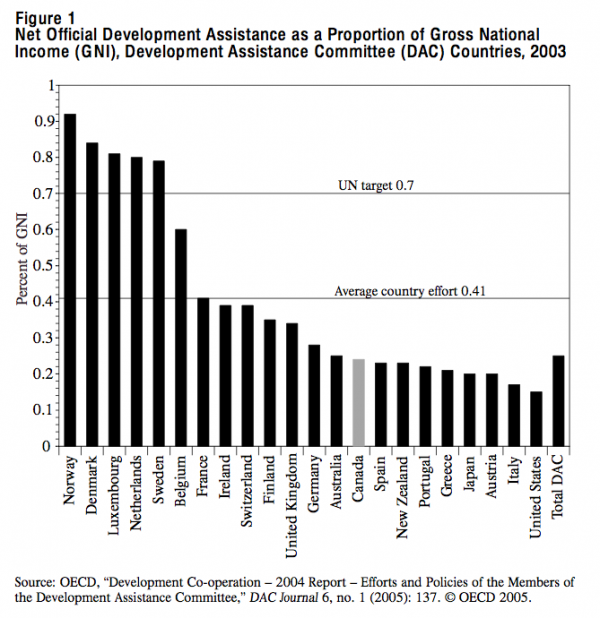

Notwithstanding Canadians’ common belief that their country is a generous donor of aid, among industrialized states it has actually become a below-average donor of international development assistance. Its official development assistance expenditures have declined drastically over the past 10 years. While Canada devoted 0.46 percent of its gross national income (GNI) to official development assistance in 1992-93, by 2003 that figure had declined to a low of 0.26 percent of GNI. This is far below the average amount that OECD (industrialized) states gave in 2003, which was 0.41 percent, never mind trying to reach the target of 0.7 percent of GNI that United Nations member states, including Canada, committed themselves to strive toward in 1970 (see figure 1).

The federal government’s new International Policy Statement (IPS) does not mention that 0.7 percent goal, but instead pledges to double the 2001 level of official development assistance and other foreign aid by 2010, and then to continue to increase it (Foreign Affairs Canada 2005, 21).

Canada should devote more assistance to democratic development than it currently does. The Canadian government has repeatedly stressed at a rhetorical level in policy framing statements that our fundamental values and foreign policy interests include “democracy, human rights, and the rule of law” (Foreign Affairs Canada 2005, 4; 1995), and that we wish to project those values to the world. This is one of the common reasons why Western democratic states have an interest in promoting democracy overseas: as George Perlin has phrased it, “a commitment to the intrinsic worth of liberal-democratic values” (2003, 3). Ottawa has traditionally shied away from any approach to foreign aid that would smack of paternalism by assuming that either Canadian institutions or a more broadly Western model of democracy are the best models for developing countries (Schmitz 2004, 11). Nonetheless, the government has repeatedly claimed to place a high priority on democracy as a general principle that Canada should promote worldwide. In foreign policy review documents since the end of the Cold War, the government has phrased “Canadian values” as including democracy at the forefront (Foreign Affairs Canada 1995, 2005). Notably, “good governance” is not typically stated as a fundamental Canadian value at this rhetorical level – good governance simply does not have the flashy ring to it that democracy has as an ideal.

If the above reason suggests that democracy has an intrinsic worth that Canada should always promote, Perlin and others point to at least two other instrumental, self-interested reasons why governments have come to view democracy assistance as a crucial foreign aid component. First, there is a strong empirical record of democratic regimes not engaging in military conflict with one another (Perlin 2003, 2-3). There is dispute in the literature as to whether this is a law without exception in international relations and what explains the pattern (Brown, Lynn-Jones, and Miller 1996), as well as the extent to which a democratic regime must be institutionalized in order to promote peace both within and outside its borders (Mansfield and Snyder 1995). Nonetheless, there is a strong pattern of peaceable relations among democracies. Thus, it is in the interests of existing democratic states to promote democratic development beyond their borders in order to pursue their own security (Burnell 2000, 46).

Second, in the 1970s and 1980s donors grew frustrated with the sense that economic aid policies in many poor countries were bringing few positive results due to problems such as rampant corruption and poor governance in authoritarian or weakly institutionalized regimes (Perlin 2003, 5; Carothers 1999, 46; Burnell 2000, 41). This realization spurred an interest in improving governance and citizens’ control over public policy and political leadership, in order to ensure that economic assistance did not disappear into a black hole.

Given the rhetorical commitment that Canada has made to promoting democratic values in its foreign policy, and the practical self-interested reasons why democracy in other countries is a desirable outcome for Western donor countries, the federal government should ensure that there is a strong democracy focus in its foreign aid programs. The recent IPS gives few signals that the government plans to increase funding for democracy assistance exponentially in the foreseeable future, so this paper will speculate on how Canada could maximize the impact of its existing assistance for overseas democratic development by making difficult choices on how to distribute such aid in terms of both substantive focus and regional concentration. I include examples, where applicable, from the country where I have the greatest experience in assessing democracy assistance programs: Russia.

It is important to keep in mind that broad government policy statements such as the IPS are tricky balancing acts. Their architects intend to leave wide latitude for bureaucratic agencies and individual diplomatic missions to maintain a certain degree of stability in their programs and routines, while placating various other stakeholders (in this case, international organizations such as the OECD and the UN, and domestic constituencies such as development NGOs and concerned citizens). Nonetheless, they give important cues to political actors regarding the language they can use to justify their activities and signal some significant shifts in emphasis.

In the IPS the government does make a strong statement of commitment to narrow and intensify its areas of assistance. The most striking modification to Canadian assistance that the IPS outlines is the decision to concentrate Canada’s long-term aid on 25 core “development partner” countries, and to gradually wind down aid programs in other countries. These countries are concentrated in Africa, Asia and the Americas, and the only post-Communist country remaining on the list is Ukraine (CIDA 2005b).2 According to the IPS, the countries were chosen based on their level of poverty (preference for poorest countries), their ability to use aid effectively (good governance and management), and the degree to which Canada’s presence in the country is strong enough relative to other donors to add noticeable value to development efforts (CIDA 2005a, 22-3). I argue below that these criteria for country partner selection have very little to do with the goal of promoting democratic development overseas.

The government is also attempting to narrow its focus to particular sectors of assistance, thereby specializing in certain areas based on the priorities of achieving the Millennium Development Goals, matching those goals with needs expressed in developing countries, and working in areas where Canadians may have a niche of expertise (CIDA 2005a, 11). “Good governance” is one of the areas emphasized by the government in this new plan, and this theme includes “five pillars”: democratization; human rights; rule of law; public sector institution and capacity building; and conflict prevention, peacebuilding and security-sector reform (13).

In fact, the choice of the term “good governance” in the IPS is not coincidental. “Governance” has been the term of preference in Canadian government assistance for political development throughout Canada’s history of providing such foreign aid. The new IPS does mention the goal of democratization more frequently than past government policy statements have done, but “democracy” is still not the preferred word that stands out in the latest policy statement. In a recent Policy Matters paper, Gerald Schmitz provides an excellent elaboration of the history surrounding the Canadian government’s reticence about openly advocating democracy overseas (2004). During the Cold War period, of course, the Western agenda of promoting democracy (particularly by the United States) was not viewed in a friendly light by many critics of Western values. Instead, democratization was seen as a biased agenda of promoting Western hegemony in the Cold War competition between communism and liberal democracy. So in the policy discussions leading up to the founding of the Parliament-funded International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development (ICHRDD) (now Rights and Democracy) in 1988, observers cautioned against the use of the word “democracy,” instead preferring to focus on promotion of human rights.

“Democracy” was a controversial term to use during the Cold War era; however, today it cannot be denied that a basic norm of democracy has developed globally. Virtually all national governments are now reluctant to call themselves opponents of democracy, even if they do not fulfill the democratic principle of rule by the people in practice. This normative opening in the international system provides an opportunity for promoters of democracy. Once governments have rhetorically proclaimed their interest in democracy, it is more complicated for them to reject outside assistance in achieving it than it would have been when the ideal of democracy itself was contested. Governments can still argue that foreign governments have interests other than democracy in mind in offering democracy assistance programs; spokespeople for the Russian government, for example, have stated on numerous occasions that foreign donors are supporting Russian civil society in order to turn civil society groups into puppets for foreign agendas (Evans 2005; Lipman 2005). Nonetheless, governments can no longer easily dismiss democracy assistance by arguing that democracy itself is an alien concept. So today, as Schmitz argues, and Robert Miller, an early promoter of the concept of the ICHRDD, points out, the concept of human rights is at least as contested internationally as the concept of democracy. Consequently, if the government really means democracy as the goal, “it should not be shy about saying so” (Schmitz 2004, 15).

In an IRPP Working Paper, Axworthy, Campbell and Donovan (2005) survey a wide array of institutions that various governments have created and/or funded to promote democratic development overseas. However, they focus solely on institutions that are based on political parties as their core staffing mechanisms and organizational backbone – whether single-party or multiparty in design. There are many other programs that constitute a considerable amount of government-funded democracy promotion overseas. In addition to mechanisms involving political parties based in their home countries, Western governments have also implemented democracy assistance through their own ministries, departments and international development agencies, which frequently contract out the implementation to organizations in the private nonprofit sector.

In this section, I give an overview of how several countries’ governments have designed their official democracy assistance programming: the size of their democracy assistance budgets, how they have organized bureaucratic structures responsible for such assistance, what the substantive areas of their focus have been, and how they have distributed assistance geographically. I examine the programs of the two largest donors, the United States and the European Union, as well as two smaller European donors, the Netherlands and Germany. The latter two countries provide potential models for Canada because the size of their foreign aid budgets are roughly comparable with Canada’s. Yet the ways in which the Netherlands and Germany have organized their democracy assistance strategies are very different from the way Canada has organized its overseas assistance.

One international trend is that the ways government donors from different Western states approach democracy assistance seem to have been converging gradually since the 1980s and 1990s, when the United States and European donors were often contrasted with one another. The US was perceived as designing very specific programs and not being responsive to local conditions in recipient countries, while the European Union was perceived as being much more demand-driven, allowing local citizens a great deal of latitude in proposing projects for funding (Youngs 2003, 134). Most analysts saw the US as heavily focused on intervening in the design of political institutions and the creation of political-rights-advocacy organizations in the image of American civil society. In contrast, European states were perceived as being much more focused on human rights as an issue, and much less willing to push a specifically “European” notion of democracy or rights on other countries. The United States gave short-term grants to organizations in recipient countries to conduct specific projects, while many European organizations, such as the German Stiftungen, or party foundations, were willing to support the overall operating costs of nongovernmental organizations in recipient countries for many years at a time. Along all of these axes, donors seem to be moving away from the margins to a middle ground. This is largely a result of having experienced flaws in their own ways of doing things, which has led them to look to one another for solutions to the problems they encounter in aid delivery.

Another general trend in recent years among government donors, particularly smaller ones, has been to focus assistance on fewer countries and on fewer issues (Santiso 2001, 5). Donors have realized that concentrated, intensive assistance has more impact on democratization in local contexts than aid that is scattered thinly around the world. Moreover, as others have noted, governments can gain a stronger reputation in democracy assistance by specializing in distinctive ways in specific countries and issues (Axworthy and Campbell 2005). In its recent proposal to narrow its areas of assistance, the Canadian government has joined this trend among most other small bilateral donors in democracy assistance specifically, and development aid more generally.

The United States is by far the largest absolute donor of democracy assistance worldwide, as well as official development assistance in general. The OECD keeps track of democracy assistance by classifying bilateral aid under the somewhat imperfect category of “government and civil society” – imperfect in large part because most analysts would not categorize all “government” assistance as democracy promotion. Yet this category is the most consistent available tally of governments’ democracy assistance expenditures. In 2003 the United States spent just over US$2 billion in bilateral government and civil society aid worldwide (table 1). Despite this enormous absolute amount of assistance, foreign aid in the United States constitutes one of the smallest proportions of gross national income among all of the OECD countries, at only 0.15 percent of GNI in 2003 (see figure 1).

United States government assistance programs are consolidated within particular agencies and offices, compared to those of most donors. Nonetheless, some programs are tucked away in multiple, not always intuitive, locations. The vast majority of official United States assistance for democratic development is located within the budget of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which is overseen by the US Secretary of State. Since November 2001, USAID has had a self-standing Office of Democracy and Governance,which aims to coordinate and design US government programming in these issues around the world (from 1994 to 2001 this body was called the Center for Democracy and Governance). This office works in coordination with USAID missions in particular countries and regions to help them design democracy and governance programs for their locations (USAID 2005).

In addition, the State Department works through a number of mechanisms to promote democratization. The Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor is the primary location for State Department programs to promote democracy. Among other programs, the bureau grants much of the yearly congressional allocation of funds to the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), an independent, non-partisan organization funded and overseen by Congress, but not directed by it. NED contains within it four “core institutes”: the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) and the International Republican Institute (IRI), which are loosely aligned with the two major political parties, as well as the American Center for International Labor Solidarity, representing the AFL/CIO, and the Center for International Private Enterprise, representing the US business community. In 2004, the NED received a total congressional budget allocation of just under US$40 million, but President Bush has promised to increase the NED budget to US$80 million for 2006 (with half that amount being dedicated to new programs in the Middle East and North Africa) (US Department of State 2005). Another State Department democracy promotion mechanism is the small-grants programs for NGOs that are administered by US embassies in recipient countries. Smaller amounts have come from other agencies such as the United States Information Agency (USIA), which closed in 1999, and whose programs have now mostly been amalgamated into the Department of State’s Bureau for Educational and Cultural Affairs.

Because the United States is the largest donor, it has far fewer problems than most other donors in deciding where to allocate democracy assistance funds. Although it could be larger, the budget is large enough to allow the United States to invest significant funding in nearly all transitional or semidemocratic states, and to fund a wide range of programs. Thus, in most countries that receive democracy assistance there are multiple sectors being targeted simultaneously. Nonetheless, there are some distinct trends in US assistance strategies over time.

First, since the mid-1990s, the US has increasingly focused democracy assistance on programs aimed at civil society development. This contrasts with an earlier preponderance of attention to so-called top-down approaches to democratization in which electoral and state institutional design was emphasized. According to Thomas Carothers, this stemmed partly from the practical circumstances of the 1980s and early 1990s, when a large number of democratic breakthroughs and first elections were taking place around the world. It also stemmed from the tendency of US administrations in the 1970s and 1980s to fear any populist mobilization and instead to prefer supporting transitions in a step-by-step manner controlled by the political regime itself (Carothers 1999, 89). Over time, that emphasis changed as the US government realized that purely top-down approaches can lead to hollow democratic institutions with little democratic support from the population at large, and the danger of reversion to authoritarianism without popular checks on government conduct.

Thus, starting in the mid-1990s, along with most other donors, the US began to increase its attention to “bottom-up” civil society development programs. Most donors moved in the same direction throughout the 1990s, and they espoused roughly similar conceptions of what democratic civil society should look like; that is, a discrete sphere of associations, sharply separated from the state and the market (Carothers 1999; Carothers and Ottaway 2000; Van Rooy and Robinson 1998). All agree that it is necessary to strengthen civil society in order to promote democratization, and they do so by supporting nongovernmental organizations that work to increase citizens’ participation in public or political life.

Yet while the definition of civil society and the basic goals that donor governments pursue with regard to civil society are fundamentally similar, there are some definite differences in how donors’ civil society assistance programs are structured, and how their strategies have evolved over the years. For the US, civil society has been defined for aid purposes in a very specific way that emphasizes groups advocating civil and political rights of various kinds, as well as the environment. There is scant attention to basic grassroots charity organizations or social service organizations that do not have explicit rights advocacy goals (Sundstrom 2001; 2003, 150-1). This is largely because, like other donors, the US tends to define its goals in democracy assistance by comparing the status quo for democratic institutions in recipient countries with a romanticized version of the situation that exists at home (Carothers 1999, 248). Thus, the ideal for consolidated democracy elsewhere is constructed mainly from an understanding of what exists back home, rather than any careful consideration of the ideal logical underpinnings of democratic regimes and how those could be fostered. Since American civil society, at least today, is heavily dominated by advocacy NGOs for particular interests or values (Skocpol 1999), this is the kind of civil society that US assistance has generally tried to promote.

The European Union has its own programs for democracy promotion, in addition to the programs of individual member states. When member states’ bilateral assistance programs and European-level programs are combined, European funding for democracy assistance actually exceeds US assistance by a significant margin (Youngs 2003, 128). Here, though, I only discuss European Union (EU)-level programs. European Commission (EC) funding devoted to governance and civil society amounted to US$728 million in 2003 (table 1). This is less than half the amount of US assistance in this area, but far outstrips other bilateral donors’ expenditures. Unlike many Western donors, the EC devotes a larger share of its social and administrative assistance to the area of governance and civil society than it does to fields such as health and education (OECD 2004, 183-4). Canada, Germany and the Netherlands, for example, give more aid to education than to governance and civil society.

EU programs in the early 1990s suffered from a number of problems, stemming organizationally from two shortcomings: a lack of EU coordination of programming, and a lack of adequate staffing to process project approvals and oversee programs (Youngs 2001, 32-3). There was no general understanding or bureaucratic attempt to keep track of how programs of different member states and the EU itself compared with one another or overlapped. There was no EU unit designed to coordinate democracy assistance under a single institutional banner. This spawned areas of confusion and disagreement among units in the convoluted European bureaucracies (Crawford 2000, 90). Youngs remarks that these “disconnects” occurred between the EU and member states, among member states themselves, between EU human rights machinery and machinery based on responsibility for geographic regions receiving aid, and between older human rights programs and the newer democracy promotion agenda (2001, 33). In Russia and the rest of the former Soviet Union in particular, the Tacis (Technical Assistance to the Commonwealth of Independent States) program of the early 1990s experienced serious problems such as incoherent goals and extremely cumbersome and bureaucratic project approval regulations. Internal and external observers sharply criticized the program, with one evaluation even calling it “one of the worst managed aid programs of all” (quoted in Sakwa 2000, 291).

All of these problems of EU democracy aid in the 1990s highlight the need for governments to have a coordinated approach to designing and implementing democracy assistance overseas, as well as foreign aid in general. Observers such as Axworthy and Campbell have argued that Canada suffers from the same lack of aid coordination (2005), although in Canada the problems have not been so great as in the EU, in part because of the relatively tiny size of Canada’s democracy assistance efforts. A lack of coordination is simply much more obvious in an aid structure of enormous scale.

In response to these sharp criticisms, the EU human rights and democracy assistance strategy underwent a major overhaul beginning in 1999. This resulted in July 1999 in the European Commission creating a new Human Rights and Democracy Committee to oversee and bring greater coherence to EC democracy assistance work (European Commission 2004). Delivery of actual democracy assistance programs was also shifted primarily into the European Initiative for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR). While tighter coordination of such work was something for which critics of the EU’s record in the 1990s had cried desperately, there were controversies and drawbacks associated with this change. Creating a new “basket” for EU democracy programming required that such programs be scooped out of geographically based departments in the EU aid structure. Some dissenters argued that this would hinder holistic approaches to foreign aid by obstructing coordination of democracy programs with economic and social assistance programs for particular recipient countries and regions (Youngs 2001, 34).

While it is difficult to gauge whether this has actually happened with EU aid programs as a whole, it appears that since the restructuring, there have at least been strong efforts in the EC to build linkages between EIDHR programs focused on democratization and human rights, and EC programs focused on good governance (housed in other EC “institutional support” budgets), particularly by incorporating grassroots participation as part of good governance projects (Youngs 2003, 131-2). The good governance category in EC aid, long viewed as separate from democratization and human rights, includes areas such as anti-corruption, public administration reform, and decentralization – that is, it seems to emphasize institutional effectiveness as distinct from democratization in the sense of promoting citizen rights and participation.

Geographically, the EU has expanded rather than constricting its focus over time, in contrast to many small donor countries. The EU, in concert with its member states, can afford to do this because its foreign aid budget is large and increasing, and thereby in size becoming more akin to that of the US, which also delivers democracy assistance in a broad array of countries. The EU began its democracy promotion efforts, understandably, in southern and eastern Europe as the “third wave” of democratization progressed from the 1970s into the 1990s, seeing its priority as democracy and security in regions bordering on or becoming new members of the EU. In the 1990s, the EU began to launch more significant programs in other regions, particularly the Mediterranean region, from which it perceived possible security threats and already felt significant migratory pressures (Youngs 2001). At this time, European assistance to Latin America, although modest, also took on a significant focus on democracy, human rights and the rule of law (Crawford 2000, 97). In other regions, such as Africa, the Caribbean, the Pacific and East Asia, assistance in the areas of democracy, human rights and governance has been a fairly recent and contested addition to EU development programs, but it has been gradually increasing (Crawford 2000, 95-6; Youngs 2001, 115).

Although the EU has expanded the number of regions to which it gives aid over the past few decades, beginning in 2002 the EC, taking an approach that was similar to those of many donors, decided to focus democracy assistance on a select group of countries. As of 2004, the EC had chosen 32 “focus countries,” with the largest number (12) in sub-Saharan Africa and the others scattered among other developing and post-Communist regions. The EC gave different criteria for choosing its focus countries than did Canada and the Netherlands. They were: (1) to enhance the impact of EIDHR activities; (2) to foster coherence with other development cooperation instruments of the EU; (3) to benefit political relations between the EU and specific developing countries; and (4) to promote geographic balance (European Commission 2004). In other words, the reasons have more to do with EU policies and the desire for visible EIDHR impact than with conditions on the ground in the focus countries. Notably, though, these focus countries are specific to the EIDHR program and not common to all EC assistance. This differs from Canada’s and the Netherlands’ development partner countries, which are chosen for all types of development assistance, whether oriented toward poverty or democratization. As I discuss below, I believe that employing separate criteria to choose target countries for different types of aid is a good way to maximize the positive outcomes.

As for sectoral focus, the EU, like the United States and most other donors, has shifted from concentrating on formal political institutions and procedures (such as electoral procedures and parliamentary institutions) to focusing on civil society, with most of the aid to NGOs being devoted to human rights issues. Youngs points out that between the mid-1990s and 2002, the share of EIDHR funding spent on electoral assistance dropped from over 50 percent to 15 percent. By the end of the 1990s, in most recipient regions the share of democracy and human rights aid allocated to NGOs had soared to between 80 and 90 percent (Youngs 2003, 129).

Dutch assistance is an interesting example for Canadians to study in assessing options for democracy assistance programming, as well as for foreign aid spending more broadly. First, the Netherlands is one of the few states that has met and exceeded the internationally agreed-upon target of devoting 0.7 percent of GNI to foreign aid. It met the 0.7 percent target in 1975, becoming the second country after Sweden to do so. The Netherlands has now settled on a more or less stable annual contribution of 0.8 percent of GNI. As such, the Dutch are serious about their foreign aid; they see development assistance as a priority on their foreign policy agenda.

Second, the Dutch approach makes an interesting comparison for Canada because, in absolute terms, it gives a similar amount of foreign aid as Canada in the area of government and civil society. In 2003, the Netherlands gave approximately US$192 million in bilateral aid worldwide for these purposes, while Canada gave approximately US$167 million (table 1). Yet it is important to note that the Netherlands devotes much less attention to democracy assistance as a proportion of its overall portfolio of foreign aid than Canada does. It devotes only 6.5 percent of all bilateral aid to government and civil society programs, while Canada spends 12.4 percent of its worldwide aid on these purposes. The Netherlands has used a strategy for allocating limited aid across countries and regions that provides useful lessons for Canada in revamping its approach to democracy assistance.

The Dutch government, through the central coordinating Ministry of Foreign Affairs, uses a number of different aid delivery channels in the category of “good governance” (does this sound familiar?), which is the category under which the ministry classifies democracy assistance. The government has a list of 36 “partner countries” in Africa, Asia and Latin America, whose governments receive from the Netherlands not only governance aid, but primarily other forms of development assistance (Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2005a).

The ministry also grants assistance to nonstate actors – particularly NGOs in the case of democracy assistance – whom it calls “partners in development,” with which it works particularly in countries “where the Netherlands does not wish to work with the government, either because there is no government to approach (as in Somalia), or because the government pursues extremely bad policies” (Royal Netherlands Embassy in Moscow 2000).

In addition to programs that are directly administered and delivered by the Dutch government, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has funded the Dutch Institute for Multi-party Democracy (IMD), which was created in 2000 to build political parties and party systems in young democracies. This institute is similar to many other multiparty institutes, particularly the NED in the United States, in terms of its mandate and structure. Yet because of its limited budget, the IMD is different from the NED in that it focuses on a narrow range of countries within the set of partner countries for foreign aid that the ministry has identified. Any Canadian multiparty institute would likely operate in a very similar manner internationally.

Like Canada’s new emphasis outlined in the recent IPS, the Netherlands’ aid focus is heavily on Africa, with half of all aid going to that continent. It is also concentrated on the objective of poverty reduction, in line with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that the United Nations has set as a priority to be achieved by 2015 (Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2005a). The Dutch government undertook a thorough review and redesign of its democracy assistance programming in 1998, and at that time took two important decisions that the latest IPS in Canada mirrored. First, the Dutch government decided to reduce the number of countries receiving Dutch aid from almost 120 countries to 19 “partner countries,” on which aid would be heavily focused. Second, it decided to select those countries based on two criteria: the level of income and the quality of governance in recipient countries. The government wanted to focus on countries with the most severe levels of poverty and with governance structures that were good enough to ensure the recipient government’s ability to use aid effectively.

This is strikingly similar to the 2005 statement that Canada would focus on development partner countries based on their level of poverty and ability to use aid effectively. In addition, though, the new Canadian government strategy adds a third criterion of “sufficient Canadian presence to add value” (CIDA 2005a, 23). This seems wise, since there may be compromises required in the commitment to focus upon poverty reduction and well-governed countries. Canada has a history of influential relations and long-standing aid policies in some countries that may not meet these two criteria, and it would be counter-productive to remove aid programs suddenly from these countries. Putting aside the UN poverty reduction mandate for a moment, if Canada wishes to place some emphasis on democracy and human rights worldwide, and not solely for the reason that democracy is key in creating structures to reduce poverty, then there may be countries in which Canada has an influence that are not necessarily the poorest in the world, countries where foreign assistance could help to bring about democratization. Many countries of the former Soviet Union come to mind. There is also the problem that by launching a mandate to focus assistance only on countries that are already fairly effectively governed, a donor deemphasizes any commitment to assist countries in improving poor governance. As Wil Hout has put it with regard to Dutch policies: “The pernicious consequence of such a requirement is that there is no incentive built into assistance policies for countries to improve the level of governance, nor can assistance policies be used to help countries improve the quality of governance” (2002, 512).

The new criteria of the Dutch government for choosing development partners seem to represent a departure from earlier foreign policy, particularly with regard to human rights and international development assistance. In the past, the Netherlands government has faced enormous dilemmas in meeting commitments to both human rights and socio-economic development, in that it took the stance of sometimes withdrawing development assistance when governments were conducting significant human rights violations, notably in Indonesia (Baehr 1997). The Netherlands government had difficulty in choosing a clear policy on development aid conditionality and human rights. Its criteria for choosing development partners and its policy priority statements demonstrate that it has, like Canada, shifted from downgrading human rights conditionality in ongoing aid programs, to a policy of first linking “good governance” performance with high levels of poverty in selecting development partner countries, and then using “positive measures” to encourage increasing human rights compliance in partner countries. (Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2005b).

The Netherlands is known for dedicating a high share of its overall overseas democracy promotion budget to NGOs (as opposed to governments), relative to most other government donors (Landsberg 2000, 120). In my study of democracy assistance to NGOs in Russia, I became interested in the Dutch approach because the Dutch embassy was one of the donors that Russian NGO activists in the study frequently mentioned (Sundstrom 2001). The foreign affairs ministry states that approximately one-quarter of all Dutch assistance consists of support to NGOs in the developing world (Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2005a).

One example of the Netherlands’ programs focused on NGOs is the Matra (“social transformation”) program, which is the official Netherlands assistance program that works with NGOs in the Central and East European region, including the former Soviet Union. In Russia, this program has included strategies for working with both governmental and nongovernmental organizations, and the essential criterion stated for choosing activities to support has been that they “should promote public involvement in the shaping of society” (Royal Netherlands Embassy in Moscow 2000). This program explicitly avoids advertising very specific granting priorities and instead invites applications on all topics related to democratic development that promote the rule of law, public participation in decisions, and proliferation of NGOs (Royal Netherlands Embassy in Moscow 2000).3

Germany provides a good point of comparison in the spectrum of possible democracy assistance strategies, since its modus operandus has differed significantly from those of most other government donors. Like Canada it falls within the range of smaller donors in bilateral democracy assistance programs, as it devoted approximately US$256 million of bilateral aid to “governance and civil society” purposes (see table 1).

Germany has opted for several decades to deliver democracy assistance programs largely through party foundations, or Stiftungen. As Stefan Mair points out, the Stiftungen “are without a doubt among the oldest, most experienced and biggest actors in international democracy assistance” (2000, 128). These foundations, unlike the Dutch IMD example but like the NED’s NDI and IRI foundations, are separate foundations for individual German political parties rather than multiparty foundations. As a result, they have tended to be more ideological in nature than multiparty foundations, and even more ideological than the two American party foundations under the NED, largely because the universe of German parties has a much wider ideological spectrum than the universe of American omnibus centrist parties.

The German approach is instructive when considering possible Canadian strategies, since the Axworthy and Campbell “Democracy Canada” proposal suggests a heavy emphasis on political parties as the organizational base for delivering democracy assistance (2005). Axworthy and Campbell suggest that Canada would do well to create a multiparty institute similar in organization to the Dutch IMD, and with programmatic orientations similar to NDI in the United States. They also argue that Canada should distinguish itself from these other party-based institutions by focusing on assisting new democracies in thematic areas where Canada is recognized worldwide, such as federalism, parliamentary institutions and multicultural policies (2005, 9).

Axworthy, Campbell and Donovan (2005) provide a thorough description of the programs of each of the Stiftungen. I am more interested here in examining the overall approach of the Stiftungen, and the pros and cons associated with it. The amount of funding that each Stiftung receives from the German state budget depends on the size of its affiliated party in the parliament. Their allocations come from the Ministries of Home Affairs, Economic Cooperation, Education, and Foreign Affairs. These funds support the Stiftungen both in their domestic work in civic education and political party functions, and in their international programs. The foundations, at their peak of funding in the mid-1990s, received approximately 4 percent of Germany’s total foreign aid budget. In 1996, they received US$237 million for overseas programs (Phillips 1999, 81). After that, funding for the Stiftungen declined significantly, and by 2000 they were receiving approximately US$107 million per year from the German budget for their international work (Mair 2000, 130). Yet this is still more than the traditional government budget allocations to the analogous American political foundations, the NDI and the IRI.

The first Stiftung, created eight decades ago, was the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, associated with the German Social Democratic Party. Initially this Stiftung worked in Germany alone, and began its democratization mandate after the Second World War, in the process of encouraging the development of a liberal democratic German political culture following the Nazi regime. The Friedrich Ebert Stiftung began conducting international activities in 1957. The Konrad Adenauer Stiftung of the conservative Christian Democratic Union and the Friedrich Naumann Stiftung of the Free Democratic Party were both created in the late 1950s. These were followed by the Hanns Seidel Stiftung of the Christian Social Union (1960s), the Heinrich Böll Stiftung of the Green Party (founded in 1997 by uniting three separate foundations that were created in the 1980s), and the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung of the Party of Democratic Socialism (1990).

The various Stiftungen have different stated geographic priorities that together cover most of the developing and post-Communist world. The Friedrich Ebert Stiftung focuses on sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia; the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung on Latin America; the Friedrich Naumann Stiftung on eastern Europe and Southeast Asia; and the Heinrich Böll Stiftung on eastern Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. Yet most of the Stiftungen have offices and field representatives in all of those regions (Mair 2000, 135).4

The sectoral priorities of the Stiftungen vary widely. Much more than the American party-affiliated foundations, the German Stiftungen depend on good relations with their respective parties in order to remain well funded, and thus their programs are closely associated with the various parties’ foreign policy perspectives (Mair 2000, 130-1). During the Cold War, there were multiple conflicting priorities among the Stiftungen in their international work, due to the fairly close ideological dependence of the foundations on their parties. For example, in Central America, the Christian Democratic Konrad Adenauer Stiftung tended to sympathize with conservative regimes, while the Social Democrats’ Friedrich Ebert Stiftung took the side of the Sandanistas and other leftist groups (Mair 2000, 132). Even in recent years, in Russia, NGOs that have been funded by multiple Stiftungen have reported distinct ideological differences between them. One leader of a St. Petersburg human rights organization recalled his experience this way:

One of the leftist foundations met with us…and we proposed to them that we work on improving access to government information…on rights of specific groups, like soldiers, children, refugees…and the representative said “Very interesting – tell me, couldn’t you be interested in the theme of the workers’ movement in Russia?” Even though we do not really have a workers’ movement in Russia!5

The usual program instruments that the Stiftungen employ are very similar to those of other donors: training both locally and in Germany, seminars, conferences and grants. Different Stiftungen work with different partners and themes in recipient countries, with some focusing on the development of elite-level political institutions such as trade unions, political parties, academics, think tanks, media and cultural institutions (Friedrich Ebert Stiftung and Friedrich Naumann Stiftung); others such as the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and the Heinrich Böll Stiftung focus more on NGOs; and the Hanns Seidel Stiftung specializes in civic education among youth (Axworthy, Campbell, and Donovan 2005, 13-18).

The types of grants that the Stiftungen have traditionally employed to support democratization differ considerably from those of most other donors in their length and magnitude. Until approximately a decade ago, the Stiftungen typically cultivated deep and long-term connections with a few core partners, often supporting recipient organizations’ entire program and maintenance needs for many years. In the past several years, though, they have shifted their approach to work with a wider variety of partners, funding smaller projects on an ad hoc basis. They also work in more countries than in earlier years, largely due to the countries that acquired new democratic regimes in the third wave of democratization (Mair 2000, 136-8). Thus, in contrast to most donors, who have tended over time to shift from a policy of thin but widespread distribution of assistance to concentration on a select number of successful organizations in a smaller number of countries, the Stiftungen have made the opposite shift.

The Stiftungen have initiated this change in response to a difficult problem: when massive resources are invested in a single organization, all of the investment is lost if that organization collapses or fails to work well. While this shift is understandable, Mair argues that it has placed the Stiftungen in peril of losing the comparative advantage they possessed in the donor community. In the past, they have operated according to their political orientations and lent long-term support to like-thinkers overseas. Now, through the process of moving to a more diffuse program consisting of large numbers of small grants, the Stiftungen have become less partisan in their orientations, and thus less distinct from other foreign donors in their approach (Mair 2000, 140).

The Stiftungen now typically have only one German expatriate employee stationed in each field office around the world. This has happened as part of the trend of expanding to work in a larger number of countries. Yet the German representative in each country maintains a strong and decisive role: he or she has a great deal of autonomy in day-to-day activities and program concentrations, with only general oversight from the head office of the foundation. They often remain posted in one country for many years – at least three or four, but often much longer. This approach has advantages and disadvantages. The chief disadvantage is that much of the Stiftung’s orientation and success in a country depends on the quality of the German representative. Yet the advantages are great: the German representatives are typically well immersed in the country’s political and social environment and have an excellent sense of local problems that need assistance (Mair 2000, 137; Phillips 1999, 87).

So what lessons do the records of other countries’ democracy assistance programs suggest about how Canada should design its democracy promotion efforts? I first address questions related to the very process of designing democracy programs and the organizational entities in which they are housed. In the final section, I wrestle with the difficult question of criteria for allocating scarce resources.

In designing democracy programs, as US experience indicates, it is extremely important to devise strategies in which local opinion is consciously solicited in recipient countries regarding what is needed and appropriate in order to advance democratic norms and behaviour. Carothers and countless other analysts of US democracy assistance have pointed out that assistance has little impact on democratization and multiple unintended negative consequences when it is not designed with input from local contexts and tailored to specific countries (Carothers 1999, 2002; Ottaway and Carothers 2000; Wedel 1998; Henderson 2003). In addition, though, the Canadian government should develop some priority directions in programming – which would vary somewhat by country to respond to local variations – by consulting a number of stakeholders. These stakeholders should include citizens of recipient countries who take an interest in democracy, Canadians experienced in the practice of democracy assistance, and scholars who have observed and assessed democracy assistance programs around the world. Priorities should not be developed by Canadians alone, based only on what Canada is “good at,” since the US experience has shown that this produces rigid programs that are not necessarily applicable in many recipient countries. Yet they should not be completely devoid of strategic focus since, as the EU record shows, this can lead to a lack of identifiable improvements in democratic development that result from assistance programs (Youngs 2003, 131).

The government should also make careful assessments before deciding upon any restructuring of the organizational frameworks that deliver democracy assistance. It is clear that some of the problems in Canada’s democracy programming are the same as the ones the EU suffered before the reorganization of the European Commission’s democracy assistance bureaucracy. Programs are tucked away in different departments and organizations, such as CIDA, embassies under Foreign Affairs, Rights and Democracy, and others. A number of commentators have lamented this problem (Schmitz 2004, 36-8). One solution that has been proposed is to create a new independent institute, the Democracy Canada Institute, to coordinate all Canadian democracy assistance under a single umbrella organization, which receives funding from Parliament but has independent status (Axworthy and Campbell 2005; Schmitz 2004, 36-8). This would be similar in form to the NED in the United States, but even more inclusive of the various forms of democracy assistance, including Canadian nongovernmental organizations and foundations that deliver assistance. While this is an excellent proposition in terms of increasing the international visibility and coordination of Canadian democracy assistance, not to mention finally giving unabashed attention to the value of democracy in Canadian assistance, it does present some distinct dangers, and it is not the only possible vehicle for achieving greater visibility and coordination.

First, the Democracy Canada Institute proposal suggests a very limited definition of democratic development as its starting point. The architects of the proposal, in searching for international models of comparison, focus entirely on democracy promotion initiatives that have political parties as their key organizational basis and, as a result, mostly emphasize elections and political parties as the primary target areas for democratic development assistance. There are some exceptions to this in their vision of international democracy promotion; for example, they mention the civic education work of the Hanns Seidel Stiftung and the support of NGO activism by the Heinrich Böll Stiftung. But political party foundations are the models for their vision of Canada’s democracy promotion (Axworthy, Campbell, and Donovan 2005). This focus on political party elites and elections de-emphasizes a broader conception of democratic development that would include widening citizen participation in governance and promoting a democratic political culture.

Second, and somewhat related, it is necessary to tackle the issue of how the proposed Democracy Canada Institute would be governed to accommodate the diverse community of government-funded initiatives, for example, Rights and Democracy, the Parliamentary Centre and Elections Canada, political parties, and privately funded foundations and NGOs. The Axworthy and Campbell model suggests, on the one hand, a central guiding role for political parties and their activists, based on models such as NDI in the US and the IMD in the Netherlands (2005, 16). Yet on the other hand, the proposal suggests that the institute would be a broad umbrella for all kinds of actors (2, 19). The model proposed by Chris Cooter, director of the Policy Planning Division of Foreign Affairs Canada, suggests that the institute would include any organizations that wished to participate in it (Schmitz 2004, 36-7). What would be the governing structure of the institute and how would potential recipients of assistance interact with the institute and its member organizations? Would the institute act simply as a clearing house of information with a Web site for prospective recipients to access information about Canadian initiatives?

An alternative to a more centralized and formalized Democracy Canada Institute is a “Democracy Council” (a term suggested in the recent IPS), which would be a consultative body of government departments and nongovernmental donors aimed at guiding development policies in the area of good governance (Foreign Affairs Canada 2005, 28). Similar ideas were advocated at an IRPP workshop on international good governance assistance in Ottawa in August 2005. It was suggested that the government-funded Canada Corps could act as a facilitator of such a council, since its mandate already includes “transform[ing] existing programming, by drawing together the many private and public sector actors to promote greater coherence in governance projects” (CIDA 2005a). The NGOs that attended the IRPP workshop made a number of other suggestions to enhance information-sharing and the coordination of Canada’s democratic development activities. These included holding periodic meetings or an annual conference of relevant NGOs and establishing “country tables” at least once a year to bring together organizations active in particular countries (as Foreign Affairs Canada has done for Brazil). Changes such as these would still allow Canadian organizations to pursue a great variety of democratic development initiatives while, ideally, decreasing duplication, sharing public relations costs and increasing the exchange of learned best practices. Of course, before any decisions are made, these options for improving coordination of Canada’s democracy assistance efforts should be discussed widely and thoroughly among governmental and nongovernmental assistance practitioners, the wider Canadian public, and, hopefully, a range of past overseas recipients of Canadian democracy assistance of various kinds.

One of the positive aspects of Canadian governmental assistance as it is currently structured, at least according to the occasional comments that I have heard from Russian NGOs who have been recipients, is that programs housed within the embassy are less encumbered with bureaucratic processes and more flexible in accommodating local project ideas than the larger structures of the EU and USAID. I hope that any new organizational structure can retain this flexibility, which can be one of the advantages of smallness as a donor.

The experiences of governments with foreign aid budgets that are comparable with Canada’s suggest that the Canadian government should limit assistance to some regional areas of concentration, as planned in the new IPS. Canada simply does not have a large enough foreign aid budget to spread over scores of countries. In 2003, Canada devoted approximately US$2.03 billion to official development assistance (OECD 2004, 136). To reach the absolute amount of funding for official development assistance (ODA) that the EU spent in 2003 (not including individual member states’ ODA), for example, the Canadian government would have to devote over US$7.2 billion, or 0.85 percent of its gross national income (GNI) to ODA to foreign aid, which is more than triple what it currently spends. In order to reach the international commitment of devoting 0.7 percent of GNI to ODA, Canada would have to devote US$5.92 billion based on the 2003 Canadian economy – more than double current ODA expenditures. The actual figure required today would be higher due to growth in the size of the Canadian economy since 2003.

In order to have a distinctive and palpable positive influence on democratization processes, the government needs to concentrate resources on particular countries and strategic themes. Most smaller OECD countries have made this shift in recent years, after realizing that the “broad and thin” aid approach is not effective. The questions that follow from this commitment are: What should the criteria be for deciding upon the partner countries and thematic sectors in which Canada will work? How do we make the agonizing decision of whom to exclude?

In the face of barely increasing foreign aid expenditures, and assuming that the share of aid devoted to democratization will not increase substantially, there are two ways in which the federal government can concentrate its resources in order to increase the impact of Canadian democracy assistance on recipient countries. The first is to narrow the number of thematic areas of assistance (or, as the new IPS puts it, to have “greater sectoral focus”). The second is to limit the number of countries in which Canada employs democracy assistance programs. The IPS proposes that the government do both. However, I argue below that the criteria outlined in the IPS for selecting development partner countries ignore the democratization agenda that is stated in the section on sectoral focus. I go on to suggest some criteria by which we could choose “democracy partner” countries and specific sectoral areas of focus.

In terms of geographic areas of concentration, the recent IPS document is correct in stating that Canada must concentrate assistance in fewer countries. The government proposes a reduction to only 25 core partner countries. However, although “good governance” is the first sectoral focus mentioned in the IPS document, and “democratization” is the first subcategory listed, the criteria for choosing countries as development partners for the future have little if anything to do with the potential for democratic development. Extreme levels of poverty are the first criterion by which development partners are to be chosen: the IPS states that only countries with less than US$1,000 in average annual per capita income would be considered as development partners (CIDA 2005a, 23). This distinction does not correspond well with the intention to partner with 25 core countries, since according to the United Nations Development Program Human Development Report, as of 2002 there were only 15 countries with incomes this low (UNDP 2004, 141-2).

The second criterion is the “ability to use aid effectively,” which refers mainly to government management and policies for social inclusion and equity. The IPS suggests using the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) ratings for countries (World Bank Group 2005), and states that countries in the bottom quintile of these ratings would not normally be considered as development partners. The CPIA ratings are a rough attempt to rate countries on their governance structures. There is an overall rating, which compiles the results from four “clusters” of areas of governance: economic management (cluster A), structural policies (cluster B), policies for social inclusion/ equity (cluster C), and public sector management and institutions (cluster D). Cluster D includes measures of rule-based governance, transparency and corruption, which are arguably extremely important for democratization potential as well as for the effectiveness of foreign aid implementation overall.6

If we look at the overall ratings of countries in the 2003 CPIA assessments, as well as clusters C and D separately – since social inclusion/equity and public sector management are specifically mentioned in the IPS criteria – we see that 3 of the 15 countries with per capita average annual incomes of under US$1,000 indeed are within the fifth (bottom) quintile of countries in the CPIA in the overall ratings; four are within this quintile in cluster C; and five in cluster D. An additional four countries fall within the next lowest quintile in the overall ratings. So it does seem to be the case that high levels of poverty and poor governance often coincide, leaving Canada with few potential development partners based on the criteria specified in the IPS.

Poverty reduction is certainly a laudable and important goal that should be one of Canada’s primary assistance priorities. But if the government really is serious about democracy as a priority as well, then there should be some reference to democratic potential in the very criteria for choosing development partners. In fact, although democracy is not an impossible goal for the poorest countries, one of the strongest repeated findings in political science is that as per capita income increases, the likelihood of a democratic regime transition increases (Lipset 1959; Huntington 1991). Moreover, the wealthier a country is, the more stable and long-lived its democratic regime is likely to be (Przeworski and Limongi 1997; Bunce 2000). Although the reasons for this relationship are disputed, the empirical pattern does exist. Aside from this relationship, we know that there are other problems in many of the very poorest countries, such as civil conflict, strong patron-client networks and corruption, which impede the potential for democratic change in the near term. These problems are partially captured by the World Bank CPIA rankings in clusters C and D, which refer to social equity, inclusion, transparency and corruption. Thus, criteria for choosing partners in the area of democracy assistance may not lead us to the same locations as criteria for choosing partners in poverty reduction efforts. Sometimes donor governments such as that of the Netherlands have faced the dilemma where poorer countries have been violators of human rights and democratic procedures; thus there is a tension between the development and democracy agendas when a decision must be made about whether to make development aid conditional upon adherence to democratic norms (Baehr 1997). As Carlos Santiso has stated, we still have not determined “to what extent these two converging agendas are compatible and complementary” (2001, 10).

I am not aware of a government that has successfully resolved the tension between stated emphases on poverty alleviation and democracy promotion. Certainly the Dutch government, whose approach is the most similar to Canada’s, has not done so. For the most part, other donors, like the Canadian government, simply continue to assert both priorities and design programs in various countries to pursue those priorities without making a clear decision at the level of policy implementation that poverty trumps democracy or vice versa. It is probably correct to uphold both priorities simultaneously, since they are both undoubtedly important, but there should be clear policy direction to determine where and under what conditions democratic development will be emphasized. If the Canadian government is serious about democratic development as a priority, it could consider several distinct sets of partner countries, depending on the sector of aid in question. It may be difficult to develop a consistent set of criteria by which all development partners are chosen if poverty reduction and democratization are both priorities. As such, it may make sense for each sector of foreign aid to have its own group of countries as core, long-term partners – a set of “democracy partners” in addition to the “development partners” that the IPS mentions. Poverty reduction through socio-economic development programs may be suitable given certain countries’ sets of problems, while democracy and human rights programs might be the most-needed assistance in other countries.

Yet by which criteria does one best allocate democracy assistance? This is less clear than in the case of poverty reduction, where there are definite approaches that can be utilized with success in the poorest countries. It is not so easy to determine partner countries for democracy assistance based on choosing those with the worst record on democratic performance. By that standard, countries with harsh dictatorships, such as North Korea, would be considered the best choices for aid in democratic development. Democracy assistance would have hardly a chance of bringing about positive change in such environments. In contexts where citizens are severely oppressed and foreign visitors are watched closely by the state at every turn, there is little hope that foreign aid to promote democracy can work effectively.

Thus, I would argue first that Canada should commit resources to democracy promotion in countries where it is likely to have a noticeable impact. This means devoting assistance funds to countries in which there is already a palpable movement in the local population in support of democratization. The existing record of democracy assistance indicates that it only has a facilitating effect where the dynamics are already in motion to some extent. Money from outside is not sufficient to start a movement where fertile ground has not already been established by local citizens.

Second, we should continue to focus assistance in locations where our programs have already begun to show some impact, but where democracy remains significantly impaired. This is in line with the general principle stated in the IPS of choosing development partner countries based on “sufficient Canadian presence to add value” (CIDA 2005a, 23). We should continue to work on a longterm basis where we have been attaining results, and not simply skip with the rest of the international donor community from one faddish location to the next. Observers of aid flows have heavily criticized donors for their tendency to move like herds of sheep from one place to the next, as democracy assistance has grown into an industry of its own. For example, beginning in the late 1990s, aid recipients in Russia acquired the distinct sense that donor funds had began to flow out of the former Soviet Union and into Kosovo. Then after September 2001, donors flooded into Afghanistan, only to reduce their presence shortly thereafter to focus resources on Iraq.

Canada can maximize its impact on democratic development in other countries by resisting this trend. For example, in the regions of Latin America, the Caribbean and eastern Europe, Canadian organizations have devoted attention to democratic development and cultivated relationships with local partners, who have a continuing need for Canadian support, given the tenuousness of local democratic institutions. Instead of shifting aid away from these regions to new “hot” areas of democratic transition, we can fill tremendous local needs for support and cultivate distinct niches for Canadian aid by maintaining our presence in certain regions while the largest donors jump to the newest transitions.

Beyond these criteria for choosing democracy partner countries, we could consider adding another: directing democracy assistance to locations where we have strategic security interests, including to transitional states such as Russia, China and those within the Americas (OAS states). As noted earlier, a long-standing pattern in international relations is that institutionalized democratic states do not engage in conflict with one another. Therefore, if we contribute to the gradual democratization of key states around us, we would be contributing to Canada’s security in the long run. However, this is a very controversial idea (presuming democracy partners are to be limited in number), since it suggests that some parts of the world – Africa in particular stands out – would be de-emphasized in the Canadian democracy assistance agenda, while remaining a priority in the poverty reduction agenda.

Just as we should not be slaves to fashion in geographic focus, we should also heed this principle in choosing the sectoral focus of Canada’s democracy assistance programs. Canada should specialize in thematic sectors where there are gaps in other donors’ programs and where Canada has expertise to offer as a result of its national or international experience.

One of the choices that confronts Canadian policy-makers in choosing sectors of focus is between following the trend of democracy assistance worldwide (taking the received wisdom at face value) and striking out in a completely unique direction. This is particularly true with regard to the international community’s faith that civil society is the correct approach to take in democracy assistance. Should Canada follow most other donors in channelling more and more democracy aid to and through NGOs? Or would Canada merely be carrying out unnecessary duplication by doing so? Should we promote democracy in a uniquely Canadian way?

I advocate an approach that emphasizes areas of democratic governance in which Canada is recognized internationally for its strength, yet takes lessons from the broader record of international aid programs on democratic development regarding the best ways in which to have a positive impact on democratization processes. So, for example, donors have become more and more persuaded that civil society is an area in which they have a noticeable impact on democratic norms and behaviour in new, fragile democracies. Canada should thus involve civic actors in partner countries as much as possible in the process of working with those countries in our areas of strength. Even though many of Canada’s strengths involve government institutions such as Parliament and a federal system, there are ways in which to include civil society in the design of programs related to these institutions. For example, informing publics about institutional choices and oversight, and advising on a process of public hearings to obtain input into institutional rules are a couple of ways in which to achieve civil society involvement and to contextualize Canada’s assistance in each country. British Columbia’s recent experience of gathering a citizens’ assembly to propose a new provincial electoral system is an excellent example of how formal institutional consultations can include the broader citizenry and thereby develop democratic institutions that are tailored to the specific concerns of a particular jurisdiction, in a democratic way.

A number of observers outside government have suggested ways for Canada to specialize and focus its assistance. One popular idea is that we should project values and institutions in which we excel, and for which we are world-renowned. This principle was mentioned repeatedly by participants at an IRPP symposium on Canada’s democracy assistance efforts in Ottawa in September 2004. Axworthy and Campbell include on this list grassroots organizational models for political parties; parliamentary best practices; decentralization, power sharing and respect for minority rights (through constitutional design and federalism); elections administration; labour legislation and union organization; and public broadcasting systems (2005, 14). They also mention “a social democratic ethos” (9). Certainly in my own study of Russian NGOs that have received foreign assistance (Sundstrom 2001), a frequent reaction to Canadian values was that we have a less individualistic and radically liberal political culture than does the United States, and are thereby “closer to Russians” in emphasizing the importance of collective social goods within a liberal context of individual freedoms.

Thus, we do have something distinctive to offer in Canadian assistance programs. However, we must be careful to offer assistance to democratizing countries and their citizens with regard to the range of choices available, and the pros and cons of different choices, without pushing all aid recipients to select the Canadian model by default. Close observers of democracy assistance in practice have noted again and again that assistance must be responsive and open to different local needs and contexts rather than offering “cookie cutter” programs based on what exists in donors’ home countries. For example, there might be multiple ways of managing the demands and desires of multicultural populations within a democratic framework. Certainly, states have adopted various ways of dealing with diverse populations, whether by electoral representation, language policies, federalism or building a common civic national identity. Canada has done well relative to the rest of the world, but we have particular circumstances and the outcomes have not been perfect. Hence, we cannot push a single solution for all evolving democracies. Context is everything.