Industrial policy — the use of governments’ fiscal powers to influence the level or direction of private-sector activity — has come back into focus in recent years, in light of developments such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These events have demonstrated some of the supply chain and economic risks associated with losing domestic manufacturing capacity. This has prompted some of our allies — particularly the United States — to undertake major industrial policy initiatives such as the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act.

There has also been a recognition that some of our biggest policy challenges require accelerated private-sector action and major capital investments. Addressing climate change and supply chain risk are two among many such challenges where governments need companies to respond in ways that support national policy objectives. Industrial policy is not the only tool in the toolbox, but it is an understudied one in Canada relative to legislative and regulatory interventions.

To help governments navigate the industrial policy landscape, the IRPP is holding a series of workshops, led by a steering group of experts, to generate recommendations for governments. This paper is the first in a series and explores potential rationales for industrial policy, some of the considerations for governments and the research questions that remain to be answered.

The paper identifies several areas as possible priorities for governments considering industrial policy interventions:

However, governments shouldn’t engage in industrial policy without careful reflection. For industrial policy to be successful, it needs a clear overarching strategy, good governance and careful evaluation. Even then, there are no guarantees that any particular intervention will succeed. Indeed, it may be that industrial policy tools aren’t appropriate for some of these challenges, or that complementary reforms are needed in other areas such as competition policy or regulation.

This paper explores some of the policy areas where governments could use industrial policy, while laying out some of the contours of what industrial policy entails and some of the questions that remain to be answered. Future papers will tackle some of these issues as part of a series that is building toward a final report, which will include recommendations for governments.

Industrial policy is a loaded term. To some, it signals a return to the heavy-handed state intervention of past decades. To others, it suggests rebalancing the relationship between the state, the economy, business and access to financing. Still others view industrial policy as a complement to the market economy that can achieve specific objectives the private sector lacks the incentives or capacity to address.

Shifting geopolitical realities, pressing environmental concerns and lagging productivity have all caused policymakers to rethink whether governments ought to consciously steer certain industries toward specific public policy objectives. In other words, do we need an industrial strategy?

Even if some form of industrial policy or strategy is desirable, many questions remain. What form should it take? How many resources should we dedicate to it? What are the primary goals? How do we measure success? Can we trust our institutions to set judicious goals and craft credible policies to address these goals, let alone properly implement, oversee and evaluate them?

In short, the emerging debate over industrial policy is complicated. That is why the Institute for Research on Public Policy is undertaking a multi-year project, “Canada’s Next Economic Transformation: What Role Should Industrial Policy Play?” We have assembled an expert steering group to understand the challenges and opportunities that motivate industrial policy, to evaluate past successes and failures, and to assess various industrial policy tools. The group is informed through consultations we are holding across the country with academic experts, governments, Indigenous leaders, industry leaders and other stakeholders.

This paper is the first in a series. It outlines Canada’s economic challenges with the aim of defining an industrial policy and laying out some potential guidelines for it. Future publications will explore issues such as program performance metrics and evaluation, and mandates and governance. The final report will offer a proposed strategy for Canada and recommendations for governments.

Steve Lafleur, research director, Institute for Research on Public Policy

Industrial policy has long been a largely dormant topic in Canada, even while many types of industrial policy have remained in use. Now that current economic challenges have generated renewed interest in industrial policy, it is worth summarizing what we know about it, what forms it can take, the trade-offs it can entail and which facets of industrial policy are particularly ripe for analysis.

Industrial policy is a broad topic that leaves much room for disagreement. We hope that, by outlining the ongoing debates and the merits of different approaches, we can identify some best practices for industrial policy that experts with a broad set of backgrounds and perspectives can agree upon. Whether or not one wants the state to pursue an active industrial policy, it should be possible to agree that certain tools and practices are more likely to achieve their aims than others.

Our interest in industrial policy stems from three overarching realities: 1) Canada faces real challenges to which it has a limited window of time to respond, and risks losing out on critical opportunities as both allies and rivals invest heavily in their own industrial policies; 2) governments in Canada are already pursuing industrial policy and it is unclear whether their decisions are adequately co-ordinated or based on a coherent strategy; and 3) there has been limited research on industrial policy in Canada.

This paper starts by presenting the concept of industrial policy. It then lays out potential rationales for industrial policy, the tools available and the need for a coherent strategy. This is followed by a discussion of trade-offs involved in consciously directing parts of the economy. Finally, it introduces the questions that we will try to answer through this research program.

By examining industrial policy both theoretically and concretely, we expect to gain a better understanding of the merits of our current industrial policies and to extract clues as to how we can make better decisions. The goal is to ultimately develop a suite of policy recommendations for governments.

Industrial policy is a broad concept or practice, lacking a single definition.

The OECD describes industrial policy as “government assistance to businesses to boost or reshape specific economic activities, especially to firms or types of firms based on their activity, technology, location, size or age” (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, n.d.-a). Jim Stanford, director of the Centre for Future Work and a member of our steering group, defines industrial policy as “proactive efforts to support investment, employment, innovation and exports in targeted high-value sectors of the economy” (Stanford, 2023).[1] David A. Wolfe, co-director of the Innovation Policy Lab at the Munk School of Global and Public Affairs, has a more structural than outcome-based definition. In his telling, industrial policy is “policy designed to change the economic structure, behaviour and/or performance of a given sector” (Wolfe, 2024).

Each definition has a slightly different focus, but all three share the common theme that industrial policy involves governments taking a conscious role in steering at least a portion of economic activity toward a particular objective. However, many government policies can be seen to favour or disfavour particular firms, industries or market segments. That makes it difficult to determine what does and does not constitute industrial policy, let alone to define it. It can remain vague or subjective.

At this stage of the project, we embrace a flexible definition of industrial policy. We are interested in the extent to which governments can — or should — use their fiscal power to consciously direct or guide certain aspects of economic activity to achieve objectives in the public interest. This may include spending to encourage particular economic activities or investments, providing financial incentives to steer the private sector toward addressing particular social or environmental objectives, or deploying financial tools to address market failures or help innovative firms scale up.

Industrial policy is also highly contextual. Many forces shape particular industries, including international policy and market dynamics, natural resources and human capital. A range of public policies across governments also influence investment decisions, access to capital and competitiveness. These include intellectual-property law, competition law, tax policy, regulations, infrastructure investment, and education and research spending. Industrial policy is simply one of many tools available.

Given that the steering group is still formulating recommendations, it would be premature to exclude potential policy solutions to address the challenges we view as relevant for industrial policy. Moreover, in some cases the most appropriate policy solution to a challenge may fall outside the scope of what we traditionally call industrial policy. We do not want to preclude good options based on a rigid definition.

Our final report will offer more clearly delimited sector boundaries, policy tools and objectives that we recommend as part of an industrial policy framework.

This brings us to the “why.” Industrial policy can, in theory, be used for a number of purposes. It is not always about job creation or economic development. Clarifying objectives can help steer governments away from wasting scarce public resources on low-value initiatives.

Industrial policy should centre around incentivizing private-sector activity that will help achieve broader public policy goals. These can include long-term economic growth, enhanced innovation, reduced greenhouse-gas emissions, improved living standards, health and security for Canadians, and more equitable distribution of the gains across regions and populations. Governments should never seek to solely enhance the profitability of specific private firms or shareholders. The net societal benefit from industrial policy must be greater than the financial benefit received by any particular firm.

Canada faces a number of critical, often interlocking societal challenges, to which well-designed and carefully targeted industrial policy might offer partial solutions. We group these challenges under eight subheadings:

Of course, industrial policy is often used for dubious ends. It can be used to prop up failing companies (or “softening the blow of decline,” as economist Don Drummond (2023) put it at the IRPP’s first workshop on industrial policy), pursue vanity projects or simply to create jobs at a very high cost to the economy. The fact that industrial policy is often abused does not discredit the concept, but rather highlights the need for sound strategy, evaluation and oversight, as well as humility.

Canada’s lagging productivity, recently labelled as “an emergency” by Bank of Canada senior deputy governor Carolyn Rogers, is now widely viewed as a serious economic challenge (Rogers, 2024). She highlighted that Canada lags other countries in both the level of economic output per hour worked and the rate of improvement over time (figure 1).

While Rogers’s remarks were not related to industrial policy, they should motivate policymakers to explore all options to increase productivity.

Some of the explanations economists have used for Canada’s low productivity performance include:

Figure 2 shows a disturbing trend in business investment over the past decade. Business capital investment per worker peaked in 2014 and is now well below 2006 levels. There are several reasons behind this decline, including a shift from capital investment for expansion in the oil and gas sector toward improved operating efficiency and payments to shareholders, and a decrease in the rate of entry of new firms (Gu, 2024; St-Arnaud, 2022).

Industrial policies — along with other policies — can play a role in helping to scale up small, productive firms, or by creating incentives for private-sector investment in sectors or markets that are likely to increase productivity. In some cases, encouraging businesses to invest in technology can help businesses improve their productivity while growing demand for technologies developed by innovative Canadian companies.

Industrial policy can also play an important role in establishing new productive industries. For instance, the early development of the Alberta oilsands was heavily subsidized by the Canadian government. Given the large sums of capital required and speculative nature of the endeavour, Canada’s oilsands sector might not have come to exist without state intervention (Hastings-Simon, 2019).

Canola production and the space sector are other areas in which success has arguably been ensured by government intervention (Carbonneau, 2024; Phillips, 2024). Some have argued that governments also played a major role in the growth of the Canadian auto manufacturing, aerospace, telecom manufacturing and pharmaceutical sectors (Stanford, 2023).

While one can debate the costs and benefits of even the most successful industrial policy interventions, it is clear that governments putting their weight behind a sector’s development can be beneficial. Steering group member Jim Stanford argues that Canada would benefit most from an industrial strategy focused on sectors that are export-oriented, technology-intensive and highly productive. This is particularly the case if such sectors anchor complex supply chains, and generate superior incomes for workers and fiscal flowbacks to governments (Stanford, 2023).

The dual shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have reminded us that we cannot take for granted the orderly functioning of global trade. While rumours of the end of globalization may be premature, it is clear that trade will not return to the pre-COVID status quo. Firms and governments seem to be taking seriously the ideas of supply chain diversification and strategic redundancy, and Canada — both firms and governments — will have to adapt. Moreover, geopolitical tensions and lopsided trade flows are leading key trading partners to more protectionist policies, which present both challenges and opportunities.

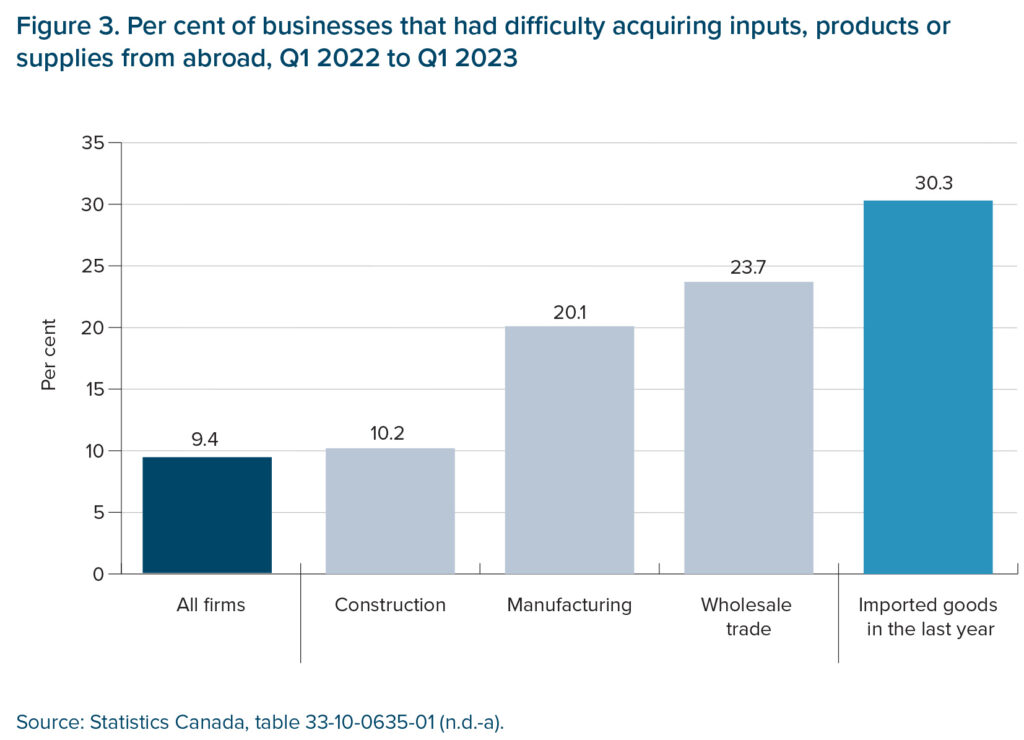

At the same time, Canada’s reliance on inputs from abroad has grown over time and shifted away from the United States toward East Asia. Exporters are also increasingly reliant on smooth supply chains for getting their products to market. As figure 3 shows, of firms that imported goods between the first quarters of 2022 and 2023, nearly one-third reported difficulties acquiring inputs, products or supplies from abroad.

Supply chain disruptions, such as those witnessed for personal protective equipment, fertilizers and semiconductors, can impact health, prices, incomes and economic activity. Around 40 per cent of industries in Canada, which together account for 25 per cent of national output, are highly vulnerable to both external demand and supply shocks. The auto and mineral sectors are the most vulnerable, followed by sectors such as agriculture and agri-food, forestry, transportation, chemicals and plastics, and mechanical and electrical manufacturing (Boileau & Sydor, 2020).

Governments have taken some steps to diversify supply chains and to encourage reshoring and “friendshoring” the manufacturing of critical goods. Corporations have taken action as well, most notably by shifting some production from China to less risky trade partners like Vietnam and India (Blais-Morisset & Rao, 2024).

There may be a rationale for governments in Canada to reduce supply chain risks in critical areas by supporting firms able and willing to produce inputs in Canada. The case is even stronger when production is highly concentrated in one country such that the risk of supply chain disruption, and the resulting societal cost, is high. For example, China refines more than half of the world’s lithium, cobalt and graphite, and produces more than 75 per cent of battery cells, 70 per cent of cathodes and 85 per cent of anodes (Defard, 2023). Any restrictions to China’s exports could disrupt global initiatives to electrify vehicles and transform auto manufacturing sectors. This concern led the federal government to develop a critical mineral strategy that it describes as a “roadmap to seizing a generational opportunity” in the exploration, extraction, processing, manufacturing and recycling of priority minerals (Government of Canada, 2022, p. 2).

The ever-shifting nature of protectionist tendencies of the United States, Canada’s largest trading partner, is also an ongoing concern — Canadian companies are at risk of disruption should American policies target Canadian imports. The recent implementation of powerful industrial policies for clean energy and related sectors in the United States — largely in response to concerns over China’s growing market share in clean technologies and manufacturing — is also a disruptive force that is creating risks and opportunities for Canada. According to Dana Peterson, chief economist and leader of the Economy, Strategy & Finance Center at The Conference Board, the United States has benefited from previous investments in research and development, automation, infrastructure, digital transformation and human capital. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS and Science Act are also driving large increases in manufacturing investment (Peterson, 2024). The long-term net effect remains to be seen, however, as the investments are also weakening the fiscal situation in the United States. In the short term, these various industrial policy measures have contributed to the post-COVID boom in non-residential construction (figure 4).

Steering group member Glen Hodgson has argued that Canada needs to respond strategically to the United States government’s support for key industries if Canada is to compete for new green investment, maintain market access and secure its place in regional and global supply chains (Hodgson, 2023). The federal government has already done so in several ways, including a suite of tax credits included in the 2023 federal budget and financial incentives for large electric-vehicle battery-manufacturing investments.

However, as it pursues industrial policy, the Canadian government must be mindful of the risk of retaliatory action from trading partners or the potential harm to existing trade agreements. For instance, subsidies or non-tariff barriers could contravene the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA). Trade policy both opens opportunities for and potentially constrains the scope of industrial policy efforts.

One of the most topical reasons for renewed interest in industrial policy is the need for decarbonization. This is essential if Canada is to meet its targets for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions and gain a foothold in growing global markets for clean technologies and goods. Canada’s approach to date has included a mix of carbon pricing, regulations and subsidies.

Steering group member Chris Ragan argues that carbon pricing should form the backbone of Canada’s decarbonization plans, since it is the least costly way to reduce emissions and provides a clear market signal to investors (Ragan, 2023). However, there are three areas where carbon pricing alone may be insufficient: uncertainty regarding future domestic or global policy; investment risks associated with early-stage technologies; and co-ordination failures with interdependent products.

While most investments involve risk, decarbonization investments are particularly vulnerable to shifts in government climate policy, such as changes in carbon pricing that would make some emission reduction investments less commercially viable. The risk is even greater for capital-intensive projects that, under certain policy trajectories, will generate returns only after decades (Clean Prosperity, 2024). With elections usually held every four years, investors are often wary of taking a leap of faith on the basis that policy plans will remain in place.

The risk is compounded in sectors that depend on international trade because major decarbonization investments can increase costs in the short term. This affects competitiveness if other firms face less stringent climate policies in their home countries. Long-term returns will also be influenced by the policies of other countries. For example, global oil demand could be much lower in the 2030s if countries adhere to their emission-reduction commitments (International Energy Agency, 2023).

Early adopters and developers of new technology also face higher risks, which can deter investors. When these technologies offer societal benefits — the reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions and air pollution, and the creation of knowledge that lowers costs and risks for future adopters — there can be a rationale for some level of government involvement (Criscuolo et al., 2023). Countries can also benefit if their companies are able to gain an early foothold in new markets.

Co-ordination failures between various firms and investors can also limit investment in beneficial technologies (Criscuolo et al., 2023). In some sectors, attracting investment depends on stable product demand or on a particular input required for production. For example, investment in clean hydrogen production may be contingent on securing forward contracts with large buyers such as steel or cement manufacturers, as well as on access to a substantial clean electricity supply for hydrogen production. Investment in biofuel production may be contingent on guaranteed supply of feedstock from agriculture and forestry sectors. Governments can help to connect buyers and sellers but may also need to play a role in acting as a first or last buyer to address co-ordination risks that impede investment.

Recognizing these challenges, the federal government set up the $15-billion Canada Growth Fund in 2022 — it is now managed by the Public Sector Pension Investment Board — which uses financial tools such as concessional equity or debt, anchor equity, offtake contracts and contracts for difference (Canada Growth Fund, 2024).

Many Indigenous Peoples and communities have been excluded from fully participating in the Canadian economy for a variety of historical, colonial, logistical and financial reasons. Industrial policy initiatives could conceivably promote Indigenous self-determination.

Government funding decisions in areas ranging from infrastructure to education can help to alleviate inequities, and tying investment to industrial strategy may facilitate Indigenous economic development by helping to overcome barriers, including those that were created and are perpetuated by the government of Canada. Of course, many of the barriers facing Indigenous Peoples will not be overcome by spending alone or by a few narrow initiatives.

Despite a strong increase in Indigenous employment income since 2005, a 2023 Bank of Canada study shows that it remains lower than non-Indigenous employment income (figure 5). The study also highlights the growing importance of the Indigenous economy in Canada, with Indigenous GDP estimated at $49 billion in 2020. However, gaps in infrastructure and access to financing continue to hinder growth (Chernoff & Cheung, 2023).

Furthermore, industrial policy has not always been positive for Indigenous communities. Steering group member Jesse McCormick of the First Nations Major Projects Coalition (FNMPC) noted that Indigenous Peoples continue to be excluded from decisions and opportunities. That is slowly changing with support from organizations such as the FNMPC, which provide free business capacity services to First Nations members. Dedicated institutions like the First Nations Finance Authority, which allows First Nations governments to borrow at rates comparable to municipal bonds, are also helping address barriers that communities often face when seeking to access capital.

Dawn Madahbee Leach, chair of the National Indigenous Economic Development Board and a speaker at the IRPP’s first industrial policy workshop, argues that more Indigenous-led institutions are needed “so that we can create our own solutions, to provide services that are trusted by our People and to allow Indigenous businesses to access financing and business services from entities that understand the needs of our People” (Madahbee Leach, 2023). She also said they need access to larger loans, integration with professional networks, training in financial literacy and more. Leach was one of the authors of the National Indigenous Economic Strategy for Canada, developed by over 20 Indigenous organizations in 2022 (National Indigenous Economic Strategy, 2022). The strategy includes four pathways (infrastructure, finance, people and land) supported by 107 Calls to Economic Prosperity, highlighting that there is a lot more work ahead.

In the IRPP’s second workshop, our panel on Indigenous economic inclusion focused on self-governance as a tool to drive prosperity in Indigenous communities. There is a strong body of evidence that jurisdiction and agency play a key role in economic success

(Pandakur & Pandakur, 2018). The federal government is moving in this direction, with plans to shift toward greater Indigenous leadership (Government of Canada, 2024a). Industrial policy will need to fit within this shifting approach, both enabling greater participation from Indigenous businesses and communities, and ensuring that Indigenous Peoples have a seat at the decision-making table for major projects on their traditional lands.

Canada is in the grips of a deep housing crisis. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation has projected that we need to produce 3.5 million additional units beyond the 2.3 million already projected to be built to achieve housing affordability by 2030 (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 2024).

Residential housing construction productivity has lagged general economic productivity for all industries since the 1990s (figure 6). Changing this trajectory will require expanding the use of innovative approaches to building.

The gap between residential construction and other industries has increased since 2020, with residential construction productivity returning to roughly where it was in the late 1990s. In 2023, it was 31 per cent below the rest of the economy. It is conceivable that there will be a mean reversion, but even if the productivity rate of the sector relative to the whole economy returned to pre-pandemic levels, there would still be a 15 to 20 per cent productivity gap. This problem is not unique to Canada, though Canada’s rapid population growth makes addressing the challenge especially pressing.

Industrial policy could help to increase productivity in the housing construction sector. The federal government is currently investing in technologies ranging from modular housing to 3D printing and automation to help boost output (Government of Canada, 2024b). For example, moving more of the construction process from worksites to factories, such as through prefabrication and panelization, can reduce construction time and reduce the scope for errors. While it remains to be seen whether these technologies are commercially viable at scale, they are a potential avenue for increasing the number of housing units built per worker.

Given the need to decarbonize the economy, we also need to ensure the scalability of energy-efficient and climate-resilient housing types that limit urban sprawl and car dependency. These types range from moderate-density infill housing — rowhouses and fourplexes in mature urban neighbourhoods — to high-density housing in transit-oriented neighbourhoods. Such models can decrease both infrastructure and transportation costs (and their associated carbon footprint), but also abate pressures to build in areas that are ecologically sensitive or at risk of natural disasters like flooding and wildfires (Environmental Protection Agency, 2014).

Without government intervention, certain regions or populations may benefit more from economic growth than others. Efforts to support Indigenous economic participation, Black entrepreneurship, northern economic development and other inclusive-growth objectives may require government involvement to overcome barriers to investment.

There are efforts already underway to empower Black businesses and entrepreneurs in Canada. Steering group member Lise Birikundavyi, co-founder and managing partner of BKR Capital, a $22-million venture capital fund that invests in tech startups founded by Black entrepreneurs, notes that she faced a lot of skepticism at the outset: “When we first started our venture capital fund for Black entrepreneurs, we were told the opportunity wasn’t there. But in less than three years we had over 1,500 pitch decks” (Birikundavyi, 2023). Her fund benefited from an anchor investment from Business Development Canada but has also been backed by a dozen other institutional investors, including financial institutions, pension funds and corporations. A range of other government-supported programs are developing that offer targeted funding for businesses led by populations that have not benefited equally from economic growth in the past, including racialized populations and those with disabilities.

Regional inequity is also an ongoing challenge in Canada. An index of economic disparity developed by researchers in 2023 showed wide variation across census subdivisions, with higher levels of disparity occurring more frequently in rural, remote and northern communities (Weaver et al., 2023). Addressing regional inequity is critical to avoiding the disengagement and discontent that can lead to support for populism, to rural-urban divisions and to a weaker democracy (Krawchenko et al., 2023). Some research has suggested that investment in distressed areas of the United States had a far greater impact on the regional economy than investment in more economically secure places (Congressional Research Service, 2023).

Federal and provincial economic development agencies could play an important role in this regard by implementing more localized and place-based industrial policies, though there needs to be coherence between the efforts of various levels of government, of course.

Canada, and much of the Western world, remain unprepared militarily for the prospect of a large-scale war involving our allies. As a middle power, Canada’s security rests on the strength of its alliances. And yet the Russian invasion of Ukraine has taxed those alliances, leaving NATO’s munitions stockpiles badly depleted (Financial Times, 2023).

Canada has long fallen short of meeting its NATO defence spending target of 2 per cent of GDP. To preserve our alliances, we should meet treaty obligations, and we could do so in part by rebuilding our defence industrial base. This could involve companies producing anything from ammunition to aircraft, ships, vehicles, drones, sensors and warning systems. NATO allows mixed civilian-military and research and development activities to be included in country expenditures when the military component can be accounted for or estimated (North Atlantic Treaty Organization, 2024).

Rebuilding Canada’s defence industrial base combined with strategic increases in defence spending can contribute to global security, which is in Canada’s interest. It could also offer the potential to capture new export growth opportunities.

Canada’s varied climate and topography mean that every part of the country is prone to some type of natural disaster. Many parts of the country are prone to wildfires, others are exposed to hurricanes and flooding. The impact and frequency of disasters will increase as the climate warms.

There are several avenues through which industrial policy might help foster resiliency. Governments could work more consciously with universities and industry to invest in research and development of flood and fire mitigation technologies and help commercialize them. One example is water bombers. Countries around the world are in the process of replacing or adding to their water bomber fleets to help combat forest fires. Indeed, European countries are awaiting Canadian-built water bombers (Last, 2022). Another example is commercializing technologies that help climate change adaption. This can range from flood- or fire-resistant infrastructure, to technologies that forecast disasters, to technologies that improve crop resilience (Shum et al., 2022).

Adapting to climate change will have costs, but it also provides opportunities for Canadian firms to develop new products and services. Industrial policy might lead to the commercialization of products or the scale-up of businesses that help Canada and the world adapt to climate change.

Once governments have established that there is a compelling case for intervention, they should evaluate both the effectiveness and the efficiency of potential industrial policy tools. What is the most efficient manner to achieve the policy objectives? Will there be any unintended consequences that work against other policy objectives or interactions with other policy tools?

Industrial policy is often thought of as a simple matter of tariffs and subsidies used to block foreign competition and promote domestic producers (Juhász et al., 2023). In reality, there are a broad range of options in the industrial policy toolbox appropriate for different contexts. It is possible to group policies based on the type of intervention (e.g., grants versus tax expenditures versus tariffs) and based on the scope of private-sector beneficiaries (e.g., economy-wide, sector, firm). And within the beneficiary categories, it is possible to differentiate further. For example, an intervention could target a particular technology within a sector, or distinguish firms based on certain characteristics, such as their size (e.g., small businesses) or stage of development (e.g., startups). Some policies are fairly broad, aimed at economy-wide production. For instance, export financing is aimed at exports in general, whereas battery-plant subsidies are allocated to individual firms to secure large investments.

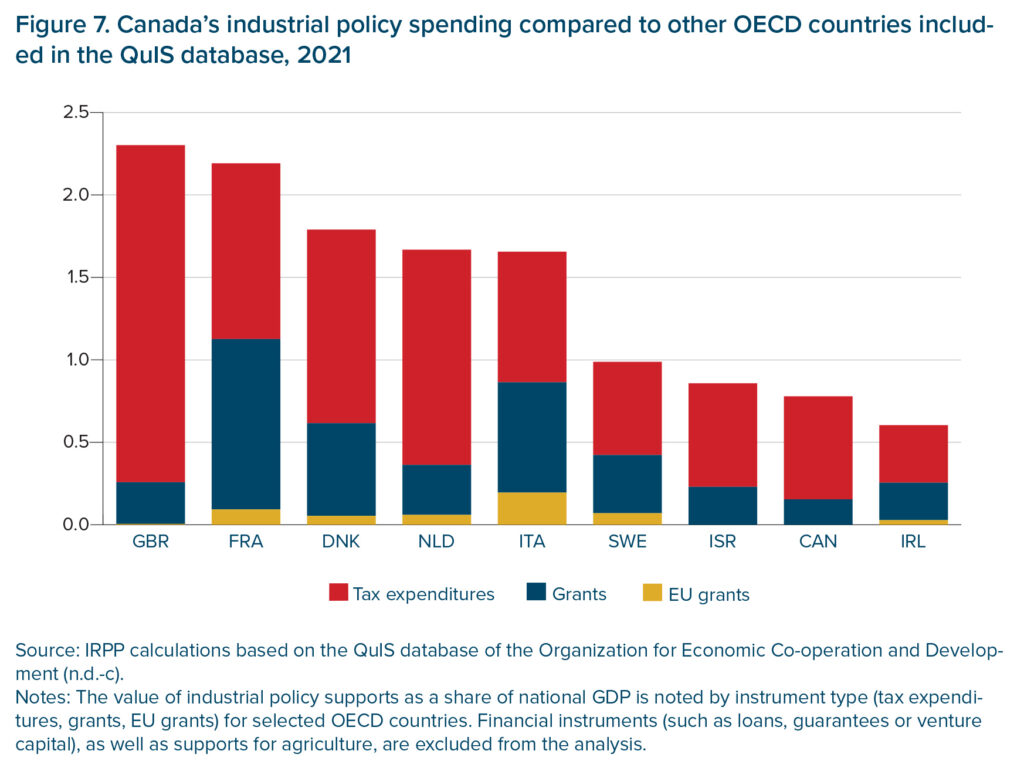

While industrial policy is often discussed as a major departure from the status quo, Canada is already engaged in industrial policy. In fact, all governments engage in industrial policy to some extent given that large swaths of public policies impact industrial production, consciously or otherwise. As figure 7 shows, the OECD’s Quantifying Industrial Strategies (QuIS) database estimates that Canada spent 0.8 per cent of its GDP on industrial policy in 2021. The OECD defines industrial policy as direct support extended by the public sector to businesses — including tax expenditures, grants, government venture capital, loans and guarantees — aimed at promoting investment, improving competitiveness or supporting economic development (Criscuolo et al., 2023). The 2021 data do not, however, capture the high-profile government investments in electric vehicles and battery manufacturing or the federal clean technology tax credits introduced between 2021 and 2024.

What is critical is relying on evidence to determine which interventions are most likely to achieve a government’s objectives. A 2022 paper by the OECD reviewed literature on the effectiveness of different industrial policy instruments and found strong evidence that well-designed research and development tax credits and subsidies can stimulate innovation. Evidence on other forms of policies, however, is limited and mixed. The authors found some evidence that grants are better suited to small firms and that financial instruments, such as public loans, guarantees or public venture capital, may be preferable forms of intervention for larger firms (Criscuolo et al., 2022).

The OECD’s research has shown that industrial policies should not be viewed in isolation, but rather as tools to fill gaps after other policies targeting framework conditions (e.g., trade and competition), access to inputs (e.g., skills and knowledge transfer), and demand (e.g., carbon pricing and regulation) have been explored (Criscuolo et al., 2023; Criscuolo et al., 2022). It also recommends that governments should make the rationale behind their policy explicit, “pay particular attention to the governance of the strategy to limit the risk of capture and attenuate information asymmetries” (Criscuolo & Lalanne, 2024). Identifying good management and oversight practices, as well as engaging in regular assessment, is key to effective industrial policy.

All policy measures come with trade-offs. Industrial policy is no exception. Below, we consider three oft-cited concerns with industrial policy: fiscal pressures and opportunity costs; market distortions; and managing scope and regional fairness. These are all crucial considerations when engaging in industrial policy.

Governments in Canada and around the world remain under fiscal pressure after the COVID-19 pandemic. Canada’s ratio of gross public debt (federal and provincial government debt combined) to GDP exceeds 100 per cent (Statistics Canada, 2022) and governments continue to accumulate debt. The federal government and eight of 10 provinces are projected to run deficits in the 2024-25 fiscal year, ranging from 0.2 per cent of GDP in Saskatchewan to 1.9 percent of GDP in British Columbia (RBC Economics, 2024).

While much of the recent public debt accumulation was driven by emergency spending and temporary revenue pressures, Canada’s public finances will continue to face challenges. Pressures on health care and old age security will continue as the population ages; defence spending will likely need to increase to meet our NATO obligations (Government of Canada, 2024c); governments need to incentivize the construction of millions of additional housing units to address an increasingly national housing crisis (Perrault, 2021); and the economy will need to rapidly decarbonize (Thomas & Smith, 2024). In this context, policies viewed as discretionary will come under increased scrutiny, which presents a significant hurdle for industrial policy efforts. A dollar spent on industrial policy is a dollar not spent on other policy priorities.

Moreover, in an era of mounting public debt and tight financial conditions, identifying a source of funds for new spending may become more challenging. A return to low interest rates cannot be taken for granted as higher interest rates increase the cost of debt financing. Private-sector actors are also under financial pressure in this environment, which can undermine the private financing of key social objectives. The difficulty of financing new housing projects is an example (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 2024).

A related consideration is that raising government revenue through increased taxes can potentially crowd out private investments, or result in economic costs that outweigh the benefit of the intervention (Dahlby & Ferede, 2018). This is particularly the case when taxes are raised inefficiently.

In short, governments face challenging decisions when it comes to public spending even in the best of times, let alone during periods of tight financial conditions and heavy debt loads.

For industrial policy, this creates a dilemma. Policies that apply broadly across the economy may be preferable, but ineffective if the funds available mean that the level of intervention is too weak to overcome obstacles to private investment. On the other hand, policies targeted at a particular firm or project may be more effective at stimulating private investment, but also increase risks associated with project failure, rent seeking and information asymmetries.

Another consideration is the impact of government decisions on the functioning of markets. The price system conveys important information to firms and individuals making investment, spending and saving decisions (Hayek, 1945). Policies that leverage private investment, such as broad-based tax credits, will be less likely to create unintended distortions. More targeted government interventions increase the risk of crowding out private investment, or unduly privileging one firm or sector over another in a way that distorts market competition.

As outlined above, there may indeed be market failures that justify government intervention. Moreover, there might be broader societal objectives that are not addressed through the existing industry structure. Governments need to weigh such considerations against the risks of market distortions.

As steering group member Chris Ragan put it: “If governments are going to intervene in the economy, they need to carefully articulate the benefits and costs and how effective the proposed tool will be relative to other options” (Ragan, 2023).

Preventing scope creep, particularly in the context of regional equity concerns, is a major challenge for governments considering new industrial policy initiatives. Many industries may frame themselves as “strategic” and governments need to be on guard against this type of rent-seeking behaviour.

As seen with recent subsidies to battery production for electric vehicles in southern Ontario and Quebec, the clustering of production facilities in certain regions can lead to resentment in other parts of the country. The Ontario government, eager to preserve and expand employment in its large automobile industry, might also become trapped in subsidy competitions with countries like the United States that have more fiscal capacity. These risks make it even more critical for governments to build an effective analytical case for targeted interventions.

Certain regions or communities may also feel they should receive similar support. Governments that have direct or indirect financial interests in projects, and especially if they receive royalty revenues, also have a fiscal rationale for ensuring they come to fruition. This could lead to a scenario in which marginal government dollars are chasing less and less enticing investment opportunities, perhaps to the point where returns are negative.

Even those who are skeptical of industrial policy tools would prefer that spending be constrained by strategic considerations rather than spread around on an ad hoc basis.

Canadian governments need a coherent set of principles to guide their choices on industrial policy. The strategy needs to be focused on the top public policy priorities and the biggest gaps in the current suite of policies. It also needs to be coherent across and within governments, ensuring that policy tools are selected and designed to complement rather than duplicate efforts and that there are no unintended consequences that harm other policy objectives. Choices on policy tools, governance structures and program mandates need to be based on rigorous analysis of both effectiveness and efficiency. Finally, a system of continual evaluation needs to be put in place to measure the results of the policy mix and recommend adjustments over time.

While this paper has attempted to broadly define industrial policy and to discuss some of the considerations for policymakers, there is much we do not know. Below are some of the questions we hope to answer through our ongoing research initiative.

Defining industrial policy and discussing its potential uses and limitations is one thing, but measuring its success is a much bigger undertaking. Governments are overly reliant on short-term job figures in narrow sectors as a measure of success, rather than providing a more complete analysis of the rationale for the policy and related metrics to evaluate success over time.

There is a great deal of uncertainty in long-term-oriented investments and many benefits may be difficult to quantify. Should we rely on narrow estimates of jobs created, or more sophisticated measures of economic and societal benefits? Moreover, there can be multiple policy objectives. How does one weigh economic growth against equity concerns, for instance? How do we account for uncertainty when evaluating speculative investments? What about opportunity costs?

Steering group member Emna Braham argues that governments need indicators that are clearly linked to the policy objectives in question, and that are specific enough that they can inform the decisions of program managers on the ground (Braham, 2023).

Evaluating industrial policy is an underexplored area. Given the fiscal pressures laid out earlier, and the ambitious objectives that industrial policy seeks to address, ensuring governments get good value for money is crucial.

In part for the reasons laid out above, industrial policy initiatives are often under-scrutinized. Once we have a framework for analyzing industrial policy initiatives, it will be worth asking which industrial policy initiatives have been successful and which have not. This will help to identify areas of strength for industrial policy and best practices. The work being done by the OECD and Statistics Canada is a great starting point, but more evidence and analysis are needed.

After determining how to evaluate industrial policy initiatives and identifying which have succeeded, it will be important to identify how we can arrive at some potential ways to improve upon existing initiatives. Given that Canada already has a number of ongoing industrial policy initiatives, improving existing programs is crucial. Sound governance and strategy need to be cornerstones of our industrial strategy moving forward.

Finally, there is the question of how much governments should spend and engage on industrial policy. It is conceivable that governments are already spending enough (or too much), but are simply not getting results. It is also possible that governments are not spending enough, or that policies are badly designed and poorly implemented.

Answering the previous three questions would go a long way in determining the possible and desirable scope of industrial policy in Canada. We hope to arrive at some answers through this process.

Shifting geopolitical and economic realities have led governments around the world to consider whether they should take a more conscious role in directing economic activity. In Canada’s case, it may be that industrial policy can help address momentous challenges like lagging productivity, adapting to geopolitical risk, hastening decarbonization and creating more inclusive growth.

Unfortunately, discussions about industrial policy are often vague and ideologically driven. We have attempted to broadly outline societal challenges where industrial policy might form part of the response from governments, the various industrial policy tools available, and some key issues for policymakers considering or already engaging in industrial policy initiatives. This paper is only the beginning of the larger project, Canada’s Next Economic Transformation: What Role Should Industrial Policy Play? We hope that, through consultations driven by our steering group and with experts from academia, industry and the policy world, we will be able to provide governments with a series of recommendations to guide their decision-making on industrial policy in the years to come.

[1] Stanford also emphasizes that industrial policy isn’t about government versus laissez-faire economics. Governments steer the economy in a number of ways, ranging from design of the tax code to monetary policy and intellectual-property protections.

Amundsen, A., Lafrance-Cooke, A., & Leung, D. (2023, March 22). Zombie firms in Canada. Statistics Canada. https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202300300003-eng

Birikundavyi, L. (2023, June 15). What could green, inclusive economic growth look like in Canada? [Workshop presentation]. Crafting a Policy Framework for Canada’s Next Economic Transformation, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Ottawa, Ontario.

Blais-Morisset, P. & Rao, S. (2024). Reshoring trend? What the evidence shows. Government of Canada. https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/economist-economiste/analysis-analyse/reshoring_trend-tendance_rapatriement.aspx?lang=eng

Boileau, D., & Sydor, A. (2020, June). Vulnerability of Canadian industries to disruptions in global supply chains. Office of the Chief Economist, Global Affairs Canada. https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/economist-economiste/analysis-analyse/supply-chain-vulnerability.aspx?lang=eng

Braham, E. (2023, June 15). Most people seem to agree that we should be aiming for more than GDP growth as a policy goal, but what are the right metrics? [Workshop presentation]. Crafting a Policy Framework for Canada’s Next Economic Transformation, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Ottawa, Ontario.

Canada Growth Fund (CGF). (2024). Supporting Canada’s journey to net-zero. https://www.cgf-fcc.ca/

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). (2024, Spring). Housing market outlook.

https://assets.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/sites/cmhc/professional/housing-markets-data-and-research/market-reports/housing-market-outlook/2024/housing-market-outlook-spring-2024-en.pdf

Carbonneau, L. (2024, February 6). History of industrial policy in Canada: What evidence do we have of costs and benefits? [Workshop presentation]. Lessons Learned on Industrial Policy, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Montreal, Quebec.

Chernoff, A., & Cheung, C. (2023, July 3). An overview of Indigenous economies within Canada. Bank of Canada. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/sdp2023-25.pdf

Clean Prosperity (2024). Canada could fall short of climate targets without expanded contracts for difference program. https://cleanprosperity.ca/canada-could-fall-short-of-climate-targets-without-expanded-contracts-for-difference-program/

Congressional Research Service (CRS). (2023, May 24). What is place-based economic development? https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF12409.pdf

Criscuolo, C., Diaz, L., Lalanne, G., Guillouet, L., van de Put, C-É, Weder, C., & Deutsch, H. Z. (2023, June 19). Quantifying industrial strategies across nine OECD countries. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 150. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://doi.org/10.1787/5f2dcc8e-en

Criscuolo, C., Gonne, N., Kitazawa, K., & Lalanne, G. (2022, May 3). Are industrial policy instruments effective? A review of the evidence in OECD countries. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 128. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/are-industrial-policy-instruments-effective_57b3dae2-en.html

Criscuolo, C., & Lalanne, G. (2024). A new approach for better industrial strategies. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 24, 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-024-00416-7

Dahlby, B., & Ferede, E. (2018). The marginal cost of public funds and the Laffer Curve: Evidence from the Canadian provinces. FinanzArchiv / Public Finance Analysis, 74 (2), 173–199. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45146950

Defard, C. (2023). The resurgence of US industrial policy and Europe’s response. La Revue de l’Énergie, 666. https://institutdelors.eu/en/publications/reveil-de-la-politique-industrielle-americaine-et-reponse-europeenne/

Deslauriers, J., & Gagné, R. (2023, April 17). The low productivity of Canadian companies threatens our living standards. Policy Options. Institute for Research on Public Policy. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/april-2023/the-low-productivity-of-canadian-companies-threatens-our-living-standards/

Drummond, D. (2023, June 15). Where do governments have a role to play in shaping economic transformation? [Workshop presentation]. Crafting a Policy Framework for Canada’s Next Economic Transformation, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Ottawa, Ontario

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2014, February). Smart growth and economic success: Investing in infill development. Office of Sustainable Communities.

https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2014-06/documents/developer-infill-paper-508b.pdf.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (n.d.). Total construction spending: Residential and non-residential in the United States. Federal Reserve Federal Reserve Economic Data. Accessed August 25, 2024. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1o6uf

Financial Times. (2023, January 31). Nato’s weapons stockpiles need urgent replenishment. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/55b7ba35-6beb-4775-a97b-4e34d8294438

Government of Canada. (2022). The Canadian critical minerals strategy. Natural Resources Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/campaign/critical-minerals-in-canada/canadian-critical-minerals-strategy.html

Government of Canada. (2024a). 2023-24 Departmental plan. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. https://cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1675097236893/1675097328140#sec3_1

Government of Canada. (2024b, April 5). Changing how we build homes in Canada. Prime Minister of Canada. https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2024/04/05/changing-how-we-buildhomescanada

Government of Canada. (2024c, May). Addendum: National defence funding and projected Canadian defence spending to GDP. Our north, strong and free: A renewed vision for Canada’s defence. National Defence. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/reports-publications/north-strong-free-2024/addendum-national-defence-funding-and-projected-canadian-defence-spending-to-gdp.html

Gu, W. (2024, February 22). Investment slowdown in Canada after the mid-2000s: The role of competition and intangibles. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2024001-eng.pdf

Hastings-Simon, S. (2019, November). Industrial policy in Alberta: Lessons from AOSTRA and the oilsands. SPP Research Paper 12(38). University of Calgary. https://doi.org/10.11575/sppp.v12i0.68092

Hayek, F. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812701275_0025

Hodgson, G. (2023, January 31). How should Canada respond to the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act? C.D. Howe Institute. https://www.cdhowe.org/intelligence-memos/glen-hodgson-how-should-canada-respond-us-inflation-reduction-act

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2023, November). The oil and gas industry in net zero transitions. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-oil-and-gas-industry-in-net-zero-transitions

Juhász, R., Lane, N. J., & Rodrik, S. (2023, August). The new economics of industrial policy (Working paper 31538). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w31538

Krawchenko, T., Weaver, D., & Markey, S. (2023, October 3). Good data is key to addressing economic disparities in Canada. Policy Options. Institute for Research on Public Policy.

https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/september-2023/economic-disparity-data/

Last, J. (2022, August 18). How an aging fleet of Canadairs is keeping Europe’s wildfires at bay. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/canadair-water-bomber-wildfire-europe-1.6553592

Madahbee Leach, D. (2023, June 15). Indigenous economic participation as a catalyst for Successful economic transformation [Workshop presentation]. Crafting a Policy Framework for Canada’s Next Economic Transformation, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Ottawa, Ontario.

Mahboubi, P. (2019, September). Bad fits: The causes, extent, and costs of job skills mismatch in Canada (Commentary No. 552). C.D. Howe Institute., https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/2021-12/Commentary%20552.pdf

National Indigenous Economic Strategy (NIES). (2022, June). National Indigenous economic strategy for Canada. https://niestrategy.ca/

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). (2024, June 18). Defence expenditures and NATO’s 2% guideline. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49198.htm#:~:text=Expenditure%20for%20the%20military%20component,procurement%20services%2C%20research%20and%20development

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (n.d.-a). Industrial policy. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/industrial-policy.html

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (n.d.-b). Productivity levels. OECD Productivity Database. Accessed August 21, 2024. https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?tm=gdp%20per%20hour%20worked&pg=0&snb=10&vw=tb&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_PDB@DF_PDB_LV&df[ag]=OECD.SDD.TPS&df[vs]=1.0&lo=5&lom=LASTNPERIODS&dq=.A.

GDPHRS……&ly[rw]=REF_AREA&ly[cl]=TIME_PERIOD&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (n.d-c). QuIS Industrial policy grants and tax expenditures. https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_INDUSTRIAL_POLICY%40DF_GRANTAX&df[ag]=OECD.STI.PIE&df[vs]=1.0

Pendakur, K., & Pendakur, R. (2018). The effects of modern treaties and opt-in legislation on household incomes in Aboriginal communities. Social Indicators Research 137(1), 139-165.

https://www.sfu.ca/~pendakur/papers/Aboriginal%20Agreements.pdf

Perrault, J.-F. (2021, May 12). Estimating the structural housing shortage in Canada: Are we 100 thousand or nearly 2 million units short? Scotiabank Economics. https://www.scotiabank.com/ca/en/about/economics/economics-publications/post.other-publications.housing.housing-note.housing-note–may-12-2021-.html

Peterson, D. (2024, February 6). Learning from experiences in other countries: Where have there been successes and failures? [Workshop presentation]. Lessons Learned on Industrial Policy, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Montreal, Quebec.

Phillips, P. (2024, February 6). History of industrial policy in Canada: What evidence do we have of costs and benefits? [Workshop presentation]. Lessons Learned on Industrial Policy, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Montreal, Quebec.

Ragan, C. (2023, June 15). Crafting a policy framework for Canada’s next economic transformation, [Workshop comments]. Institute for Research on Public Policy workshop, Ottawa, Ontario.

RBC Economics. (2024, April 3). Canadian federal and provincial fiscal tables. https://thoughtleadership.rbc.com/wp-content/uploads/Template-provincial-fiscal-tables_April2024.pdf

Rogers, C. (2024, March 26). Time to break the glass: Fixing Canada’s productivity problem. Bank of Canada. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2024/03/time-to-break-the-glass-fixing-canadas-productivity-problem/

Shum, L., Jeong, W., & Chen, K. (2022, November 1). Climate adaptation: The $2 trillion market the private sector cannot ignore. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/11/climate-change-climate-adaptation-private-sector/

St-Arnaud, C. (2022). Where’s the boom? How the impact of oil on Alberta may have permanently weakened. Alberta Central. https://albertacentral.com/intelligence-centre/economic-news/wheres-the-boom-how-the-impact-of-oil-on-alberta-may-have-permanently-weakened/

Stanford, J. (2023, June 15). Industrial policy: What, why, and how [Workshop presentation]. Crafting a Policy Framework for Canada’s Next Economic Transformation, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Ottawa, Ontario.

Statistics Canada. (n.d.-a). Table 33-10-0635-01. Business or organization obstacles over the next three months, first quarter of 2023. Accessed February 27, 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3310063501

Statistics Canada. (n.d.-b). Table 36-10-0480-01. Labour productivity and related measures by business sector industry and by non-commercial activity consistent with the industry accounts. Accessed May 21, 2024. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610048001

Statistics Canada. (2022, November 22). Consolidated Canadian government finance statistics, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221122/dq221122b-eng.htm

Thomas, K., & Smith, R. (2024, April 26). Canada needs to attract $140 billion in annual investment to reach net zero. Canadian Climate Institute. https://climateinstitute.ca/canada-needs-to-attract-140-billion-in-annual-investment-to-reach-net-zero

Weaver, D., Krawchenko, T., & Markey, S. (2023). The index of economic disparity: Measuring trends in economic disparity across Canadian Census Subdivisions and rural and urban communities. Canadian Geographies, 68(1), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12859

Wolfe, D. (2024, February 6). Current industrial policy in Canada: Is a modern approach developing? [Workshop presentation]. Lessons Learned on Industrial Policy, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Montreal, Quebec.

This report was prepared by IRPP research director Steve Lafleur, with the guidance of steering group members (Appendix A) and support from research associate Zakaria Nadir, lead data analyst Ricardo Chejfec, senior editor and writer Rosanna Tamburri, and vice president of research Rachel Samson. The manuscript was copy-edited by Claire Lubell, proofreading was by Zofia Laubitz, editorial co-ordination was by Étienne Tremblay, production was by Chantal Létourneau and art direction was by Anne Tremblay.

To cite this document:

IRPP Steering Group. (2024). Should governments steer private investment decisions? Framing Canada’s industrial policy choices. Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Acknowledgments

The IRPP wishes to thank everyone who contributed to our workshops, as well as those who provided their expertise and insight throughout the process.

If you have questions about our publications, please contact irpp@nullirpp.org. If you would like to subscribe to our newsletter, IRPP News, please go to our website, at irpp.org.

Cover: Raz Latif

ISSN 2817-8114 (Online)

Montreal — In the face of major challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change and geopolitical tensions, policymakers around the world have taken a renewed interest in industrial policy to address pressing challenges that aren’t being solved by markets alone.

Industrial policy, which involves using government resources to influence private-sector activity, has gained renewed attention in recent years. Many countries, including the U.S. with its Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS and Science Act, have launched major industrial initiatives. Should Canada follow suit?

The Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP) is addressing this crucial issue through its new multi-year project titled Canada’s Next Economic Transformation: What Role Should Industrial Policy Play? led by IRPP research director Steve Lafleur and guided by an expert steering group.

“We are engaging with stakeholders — including academics, government officials, and Indigenous and industry leaders — to learn from experience and identify potential industrial policy tools. We will provide evidence-based recommendations to governments exploring industrial policy,” says Lafleur.

To kick off the project, the IRPP has released Should Governments Steer Private Investment Decisions? Framing Canada’s Industrial Policy Choices, outlining potential applications for industrial policy:

“For industrial policy to succeed, it needs a clear strategy, strong governance and rigorous evaluation. It should benefit society at large, rather than just boosting corporate profits,” says Lafleur.

The IRPP will host a series of expert workshops and consultations throughout 2024, culminating in a major report and conference in 2025. For more information on the Canada’s Next Economic Transformation project, visit irpp.org.