News stories about legal cases involving polygamy, how many parents a child can have, what unmarried partners owe one another and other family law issues have frequently made headlines in recent years. Based on these stories one might be tempted to conclude that contemporary family life and family law are often at odds.

Indeed, in this study, McGill University law professor Robert Leckey shows that while Canadian family law has evolved considerably over the past few decades, social practices and family relationships have changed even more dramatically and have outpaced the legal framework for families. He argues that these laws regarding family relationships interact crucially with public programs, especially in terms of gender equality, income security and children’s well-being. Therefore, he says, a discussion of the appropriate role of government in relation to families requires a clear sense of the state of the law.

The study describes the changes to family law in Canada in the second half of the twentieth century and its broad outlines today (including federal, provincial, civil and common law regimes). The author first sets out the conceptual framework for the rest of the analysis, presenting four oppositions that are the source of tensions in family law: 1) public versus private law; 2) instrumental versus symbolic recognition of a given relationship; 3) formal versus functional recognition of a relationship; and 4) formal versus substantive equality.

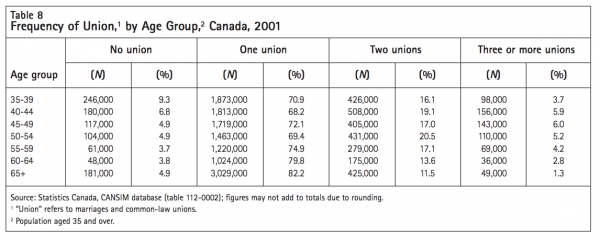

Leckey reviews the changes to marriage and divorce law in the last 50 years, notably those to equalize spousal rights and duties. Looking at data on the economic roles of spouses, he finds that legislative equality in marriage and divorce has not produced economic gender equality to the extent expected. At the same time, marriage rates have declined, so fewer couples benefit from the current regimes.

While marriage remains the most common family form in Canada, the landscape of Canadian families reflects increasing pluralism. Indeed, the increased social acceptability of relationships outside marriage has diminished marriage’s claim to the position of sole legitimate family form, while increased access and recourse to divorce have made marriage less permanent.

Paradoxically, the legal response to greater pluralism in family forms has been to treat more couples like married spouses. Leckey explores the legal recognition of same-sex and unmarried couples and shows that legislators have tended to base their treatment of these nontraditional forms of union on the traditional marriage model. He argues that this focus on marriage can impede recognition of other forms of nonconjugal relationships. Quebec stands out in this regard, since the Civil Code is silent regarding the duties of unmarried spouses toward one another.

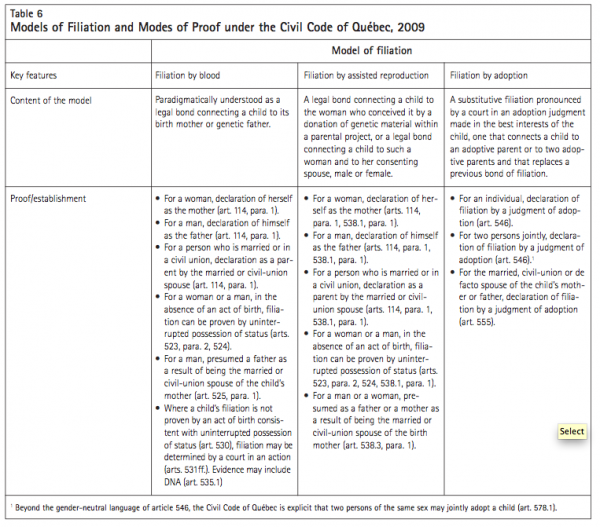

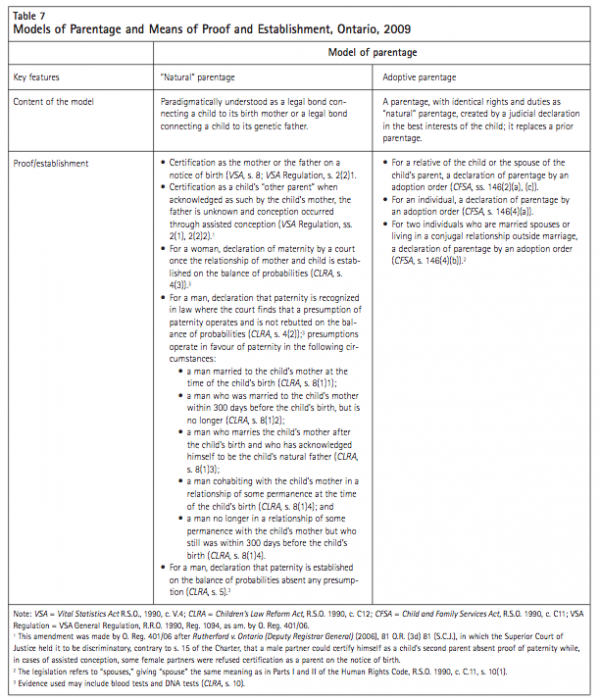

Finally, the author turns to parents and children and shows that in today’s legal regimes for recognizing parentage, there are contradictory concerns about genetic linkages, intention to parent and family stability. Having described how legal parental status is established and outlined parents’ legal rights and obligations when the family breaks down, the author then examines the implications of recognizing the parental rights and obligations of individuals who do not have full parental status.

Overall, the author argues that a coherent and sound family policy must strike a balance between the tensions within family law. These tensions, he says, are an inevitable feature of family law in a plural society. The key mission for policy-makers, in his view, should be to ensure that asymmetry or irregularity of recognition is an intended part of a larger policy plan, and not happenstance.

He also cautions that formal equality does not necessarily result in substantive equality. Indeed, despite significant law reforms to provide equality, economic disadvantage in certain types of families persists (for example, in female single-parent households). This reflects the limits of private law and the fact that, in many cases, the family resources are insufficient to support two households after unions break down, hence the need for robust social programs.

In concluding, Leckey discusses avenues for further legal changes, and he sets out guidelines for the design of public programs that support families. He makes several recommendations in relation to private family law. Quebec, for instance, should enact a reciprocal obligation of support on the part of de facto spouses who have had a child together. In addition, all the provinces should

In recent years, the family life of Canadians has collided repeatedly with legal definitions of family. January 2009 witnessed the laying of criminal charges for polygamy practiced in Bountiful, British Columbia (Matas 2009). The same month, a trial took place in Montreal in which a woman sued the multimillionaire she had once lived with, seeking $50 million of his assets and $56,000 per month in alimony. Her claim challenged the constitutionality of both Quebec’s family law and federal marriage law (Peritz 2009). In a path-breaking decision in 2007, an Ontario court declared a child to have a third parent.1 And it was only in 2005 that the Parliament of Canada made same-sex marriage possible across the country.2

Interestingly, despite the challenges and important legal changes to our understanding of family, Canadian law has no official definition of “the family.” For lawyers, the family — in a circular way — is the aggregation of the relationships, rights and obligations connecting those individuals who are otherwise seen as forming a family. So the relationships and duties of parents and children form a legal family, but the relationships and duties of neighbours do not. Relations between married spouses and between parents and children have been family law’s traditional preoccupations. But the boundaries can shift, and recognition of family relationships by contemporary laws exceeds these categories.

Legal rules in Canada currently recognize family relationships in many, often inconsistent, ways. Talk about family relationships can be confusing because the same words can take different meanings in one setting than in another (Kasirer 1999). The word “spouse” may mean something different in an invitation to a party, in rules fixing eligibility for welfare and in rules imposing support obligations. People’s definitions of family for themselves — how many pet owners view their domestic animal as a family member? — often differ from those in legal instruments. In a reminder that family practices can develop independently from legal rules, many same-sex partners referred to one another as “spouse” years before laws recognized them as such. Moreover, institutions in the private sector, such as employee benefit plans or the social pages of a newspaper, may recognize commitments that the laws of the state will not.

Difficulties in defining families connect to policy debates as to how governments should treat families and what programs they should provide so as to increase the well-being of family members. In recent years, such debates have considered topics such as parental leave, income splitting and child care. These debates engage controversial questions about the role of the state, the best use of scarce resources and intergenerational equity. In ways often left implicit, these debates connect to family law because they take definitions of family relationships for granted. Legal rules identifying family relationships and establishing their effects form the background for government programs and interact crucially with them. Discussion of the appropriate role of government in relation to families thus requires a clear sense of the state of the law, both past developments and the current regimes.

With an eye on these policy debates, this study aims to provide such an understanding of the past and present state of family law. The remaining subsections of this introduction identify key concepts necessary for understanding family law and set out the paper’s two arguments and the content of the four principal sections.

Four oppositions weave through the study. They help make sense of the developments studied and indicate areas of tension.

The first, concerning the parties to whom laws are addressed, opposes private and public family law. Private law regulates the relationship between persons and between persons and property. Rights and duties operate between family members as a consequence of their relationships. Specifically, the private law of the family treats matters of status and property as between family members, especially parents and children, on the one hand, and between adult intimate partners, on the other. Public law concerns the relationship between individuals and the state. In the family context, it consists largely of the programs through which governments carry out redistribution and deliver goods and services to individuals by virtue of their family relationships. Government policies such as taxation and social welfare help produce the family in law (Diduck and O’Donovan 2006).3 In recent years, the public side of family regulation has become more prominent, partly driven by rights claims under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Harvison Young 2001). Yet regulatory schemes that define family relationships for distributive purposes, such as workers’ compensation, date back to the nineteenth century. As the study discusses, private regulation and public regulation of families connect, as when a welfare scheme requires a claimant to enforce all possible private claims for support.

The second opposition arises between different reasons for identifying family relationships. Some forms of family recognition are instrumental: they are the instrument for applying legal rights and duties so as to achieve some purpose. The private law of the family uses marriage as a means for imposing duties of mutual support. The public law of the family takes conjugal relationships as a signal of interdependence, making appropriate the conferral of a survivor’s pension. Both the private and the public laws of the family use the legal bond between parents and children for the imposition of rights and duties. By contrast, some forms of family recognition have noninstrumental or symbolic value — that is, whatever their use, the legal recognition of some family bonds is understood as intrinsically valuable. Such recognition celebrates or affirms the relationship in a way that exceeds the enforceable legal content. For instance, the quest for same-sex marriage concerned the symbolic value of marriage, not only its rights and duties (MacDougall 2001). To be clear, calling a form of legal recognition “symbolic” should not imply that it is unimportant. Symbolic recognition may be intensely important to individuals and groups, a point underlying the struggles for legal recognition of various parental and conjugal relationships.

The third opposition consists of different bases for recognizing family relationships. Some rules of family law attach consequences to relationships on a basis that is formal. The classic formal bases for recognizing family relationships are marriage and parentage or filiation.4 The contrasting basis for recognizing family relationships is functional — namely, that the individuals have functioned similarly to the members of formally recognized family relationships. Recognition of unmarried cohabitation and of sustained conduct as a parent are examples of the functional approach.

A functional approach often takes individuals’ conduct as an implicit commitment to the relationship.

The fourth contrast opposes not dimensions of family regulation, but political conceptions of equality.5 Formal equality refers to identical treatment of individuals who are similarly situated. It drives toward sameness of treatment, a background state of affairs against which individuals achieve different outcomes in the market. Substantive equality is concerned with securing equal respect for different individuals in a way that takes their differences into account.6 It can lead to respectfully designed differences that recognize and affirm individuals’ characteristics, often concerning itself with equality of opportunity, if not equality of result. The relation between formal and substantive equality animates key issues in family law. For example, legislative reforms have made men and women formally equal in marriage, but women disproportionately experience economic disadvantage on divorce. They also continue to carry out disproportionate amounts of caregiving. That is why this study examines how well legal reforms to produce equality have translated into actual economic equality by looking at patterns of domestic and market labour.

What are the relationships among the four oppositions? Separating them is important for analytical clarity. Nevertheless, they do not interact in wholly random ways: some groupings are more common than others. The formal bases for recognizing relationships, such as marriage and filiation, are creatures of the private law; they usually engage both instrumental and symbolic dimensions. By contrast, the functional bases for recognizing relationships usually engage only the instrumental dimension. Public-law regimes typically recognize relationships for instrumental purposes, often using formal as well as functional means. It may be justifiable for law and policy to depart from such typical alignments, but, as discussed below, a departure from this pattern can also signal a potential incoherence in policy.

Before proceeding, a word about the structure of this field of law is in order. The Constitution Act, 1867 divides legislative power over the family, granting the provincial legislatures exclusive jurisdiction over family matters generally as part of their power over property and civil rights in the province, while assigning exclusive jurisdiction over marriage and divorce to Parliament. Another key constitutional feature is that the civil law provides the fundamental private law in Quebec, while the common law does so in the other provinces. These arrangements lead to the possibility that family will be defined differently in the two orders of government as well as from one province to the next. The chief sources of family law are the federal statutes and regulations, which apply across the country; the statutes and regulations of each province – in Quebec, the Civil Code; and the judgments of courts interpreting and applying those laws. The Supreme Court of Canada is the highest judicial authority for federal and provincial law. In principle, the Court’s judgments relating to federal laws apply in all provinces, although it is sometimes thought that the distinctness of Quebec’s civil law of the family should condition the application of those judgments in that province. By contrast, when the Court interprets a provincial law or rules on a Charter challenge to such a law, its ruling does not apply directly in other provinces, although the principles emerging from such a judgment are highly relevant to other provinces, provided their own laws are sufficiently similar to the one considered. Since assessments as to the relative similarity or distinctiveness of provincial laws can vary, the impact of a Supreme Court judgment concerning a law from one province on the law of another can be a matter of considerable debate. In the light of this background, this study necessarily discusses both provincial and federal law and attends to both commonand civil-law regimes of the family in Canada. For simplicity’s sake, for most purposes it takes Ontario as a representative common-law province.

Adopting a legal perspective, this study surveys Canadian family law. It provides a nutshell account of changes to that law in the twentieth century, lays out the broad outlines of family regulation today and sets out the legal rules in an empirical context of data on family practices. It traces the four oppositions identified above through the field of Canadian family law.

In the course of this survey, the study advances two arguments. The first draws together the opposition between private and public family law, instrumental and symbolic reasons for recognizing relationships and formal and functional bases for doing so. At first blush, the varying rules and approaches might be taken as indicating a disorderly field or “chaos” (Dewar 1998). Yet, however unruly the mass of rules and principles might appear, some order can be discerned. The variety of approaches point, collectively, to the insight that a meaningful and coherent family policy must attend, explicitly and simultaneously, to families as a matter for both private law and public law. It must also use formal as well as functional bases for recognizing relationships, ones that acknowledge the need for symbolic recognition of some relationships as well as, instrumentally, the importance of addressing the needs that arise from those and other relationships. The argument is not that the tension of these oppositions can be overcome; rather, such tension is an inescapable feature of family regulation in a plural society. A subsidiary to this argument about the multiple dimensions of family law is the striking contrast that will emerge in the case of Quebec, between that province’s progressive and prominent public policy in family matters and a restricted definition of the family in its private law that is arguably out of line with social practices.

The second argument is that law reform and family life in Canada show that formal equality does not necessarily bring about substantive equality. This observation does not call for rejecting formal equality. Indeed, the attainment of formal equality in many areas of family law has been an important step forward. But the observation underscores formal equality’s limits, especially within the private law of the family. The ways in which economic imbalance has survived the legal equalization of different family members — wives to husbands, children born outside marriage to children born within — highlights the need for a robust family policy, on the public-law side, in order to realize Canadian society’s commitment to substantive equality.

Both arguments unfold across the paper’s four main sections. The next section focuses on marriage and divorce. With an eye primarily on opposite-sex married couples, it provides a brief historical survey of the reforms of the past decades and addresses the contemporary regime during the relationship and afterwards. The third section surveys legal responses to the family practices of unmarried, opposite-sex cohabitants and of same-sex couples, both located outside traditional marriage. The fourth section traces the recognition of parental status and its effects, as well as the uneven application of some such effects to nonparents. Both the third and fourth sections show the grip of the past: the extension of family law has often remained in the shadow of the fundamental concepts of marriage and parentage. Although policy considerations emerge throughout the study, the last section focuses squarely on policy matters looking forward. It examines the limits of the private law of the family for securing the material well-being of family members, collects the recommendations for legal reforms set out throughout the preceding sections and presents lessons for revisions to public programs relating to families.

Marriage obviously has important social, economic, affective and, for many, spiritual elements. For present purposes, the starting point is marriage’s situation relative to the oppositions animating this study. Marriages attract consequences within regimes of private and public law. Legal recognition of marriage has instrumental value in the rights and duties it brings. It also has symbolic value in its public validation of a relationship. In terms of the bases for recognizing relationships, marriage is the paradigmatic case of formal ordering. It begins with a ceremony in which the partners exchange explicit, informed consent. Its conclusion is also formal: marriage is dissolved by the death of one spouse or by a judgment of dissolution. Assuming that the consent of spouses was free and informed, marriage seems consistent with individuals’ autonomy.

This section consists of four parts. The first recounts legislatures’ implementation of formal equality for women within marriage, which can be seen as an improvement to the law of marriage. At the same time, the increased social acceptability of other forms of intimacy and the enlarged access to divorce can be seen, at least somewhat, as having displaced marriage as the sole form of legitimate union, resulting in “the decline of marriage” (Le Bourdais and Lapierre-Adamcyk 2004). The second part shows the gap between formal equality in terms of legal rights and duties within marriage contrasted with data on the economic roles of spouses. The third part sets out the regimes applicable on divorce, when the resources of one household are divided between two. The second and third parts indicate that the legislative adoption of formal equality has not produced substantive economic equality. The fourth part acknowledges the interaction of religious rules relating to marriage with the state’s and identifies some of the resulting tensions and policy challenges.

Marriage has been the subject of much public debate. Indeed, there have been significant changes to the legal framework of marriage during the past century and a half. Developments have transformed three of its traditional hallmarks.

The first is the gendered character of marriage law. Husbands and wives historically had different roles, rights and duties during marriage. Statutes and common-law doctrines empowered men with decision-making authority on material and moral matters. In return for this authority, rules required men to support their wives. On marriage, a woman’s legal personality would merge into her husband’s, so that men exercised women’s civil rights — rights of property and contract, the initiation and defence of lawsuits — on their behalf. One consequence of this merger of legal personality was that it was impossible for one spouse to sue the other. In what was referred to as the married woman’s emancipation, reforms eventually equalized the rights and obligations of spouses during marriage. The process began in the common-law provinces in the 1880s (Girard 1990), though in Quebec not until the 1960s (Brisson and Kasirer 1996). At least formally, legislatures have now equalized the roles, rights and duties of spouses within marriage.

The second traditional hallmark is the status of marriage as the sole legitimate institution for sexual relations and child rearing. Historically, the legitimacy of marriage contrasted with the illegitimacy of other adult intimacy. Now, however, unmarried conjugality enjoys greater social acceptance than it did in the past (Milan, Vézina, and Wells 2007, 8). Legal changes also took place, with legislatures repealing the rules penalizing unmarried relationships, notably ones nullifying gifts from one unmarried partner to another and prohibiting gifts made by will. This step eliminated law’s explicit disapproval of cohabitation (Allard 1987). Moreover, as is recounted below, the legislatures of most provinces now subject unmarried opposite-sex couples to the same reciprocal duty of support as married spouses, and Canadian law no longer distinguishes between married and unmarried parents in setting out their rights and duties relating to their children.

The third hallmark is the intended permanence of marriage. Under Quebec’s 1866 Civil Code, for example, only the death of a spouse dissolved the marriage.7 Indeed, until Parliament enacted uniform legislation relating to divorce in the late 1960s, divorce laws across the country were a complicated patchwork of predominantly nineteenth-century English law.8 The increased availability of divorce in the last third of the twentieth century, however, diminished the permanence of marriage. It also aggravated the difficulty of disentangling the finances of husbands and wives. At one time, men typically held title to property acquired during the marriage. Consequently, the mere legal capacity of women to hold and manage their own property often failed to secure them anything like an equal share on the end of the marriage (Cullity 1972). The perceived injustice of women’s exiting marriages with negligible assets, or none at all, generated pressure for reform of divorcing couples’ property relations (Jacobson 1975). The 1968 Divorce Act set out in vague, discretionary terms the power of a judge to order one spouse to pay “corollary relief” to the other,9 and, in the 1970s and 1980s, the common-law provinces and Quebec enacted a number of reforms that moved toward the principle of the sharing of the growth in the spouses’ wealth during marriage. Now, dissolution of a marriage requires limited resources to be allocated so as to make two viable households out of one.

The provinces regulate the symbolic validation of marriage in the form of its solemnization. They also regulate, instrumentally, the rights and duties of spouses during marriage, although provincial rules fill in the legal content of marriage in ways of which spouses may be only dimly aware. In all provinces, maintenance or family relations statutes — in Quebec, the Civil Code — set out the obligation of spouses to support one another.10 These obligations continue during a factual or legal separation.

Legislative announcements of spousal duties are cast in gender-neutral terms. Ontario law speaks of the necessity of recognizing the “equal position of spouses as individuals within marriage and to recognize marriage as a form of partnership.”11 This declaration is fully consistent with a specialization of labour that yields different amounts of income. Indeed, Quebec’s Civil Code contemplates that spouses may contribute toward the expenses of the marriage by domestic activities.12

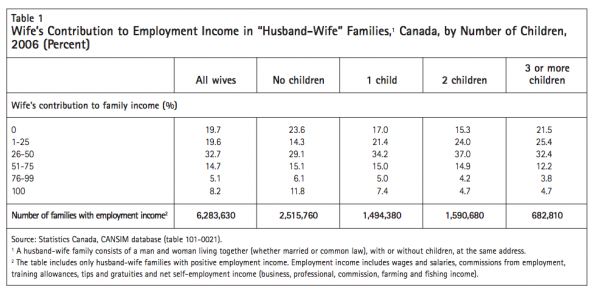

However formally equal spouses may be in their rights and duties, significant gender differences persist in patterns of domestic and market labour. These patterns affect women’s contribution to household income. Two-fifths (39.3 percent) of women in opposite-sex couples contribute one-quarter or less of the family revenue; 28 percent of women contribute more than one-half. Indeed, as table 1 shows, in households where there are no children, nearly one-quarter (23.6 percent) of women make no direct financial contribution to the family income, while another 37.9 percent contribute one-quarter or less of the couple’s employment income, and 67 percent contribute 50 percent or less of employment income. The arrival of children, however, contributes significantly to the gendered differentiation of labour. In households with two children, 39.3 percent of women contribute one-quarter or less of the family income, while 76.3 percent contribute one-half or less. In families with three children, 79.3 percent of women contribute one-half or less of employment income.

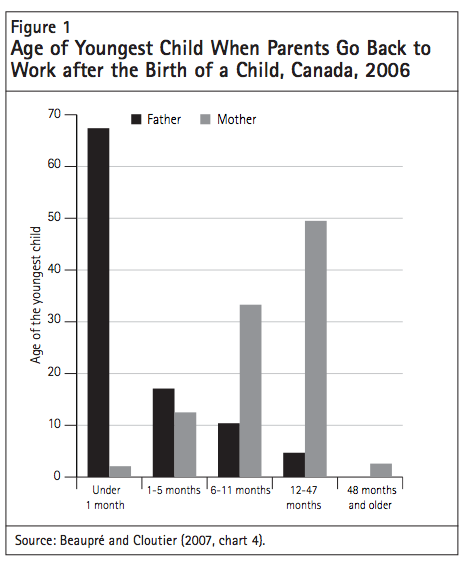

Moreover, as figure 1 shows, women spend much more time out of the workforce after the arrival of their youngest child than do men, which affects the work experience and earnings of women relative to the men with whom they are in a relationship. As well, during the marriage, that role may condition the spouses’ choices, and may establish a pattern in which the woman has a larger role in child care; should the marriage end, that pattern may influence a judge’s allocation of child custody. Family law regimes do not, explicitly, channel women toward domestic work over paid work relative to men. Yet the different roles spouses perform during marriage give critical importance to the distributive rules that apply when a relationship breaks down.

After Parliament enacted a divorce law in the 1960s, the divorce rate increased significantly: between 1971 and 1982, the annual number of divorces more than doubled, as did the divorce rate per 100,000 population (Gentleman and Park 1997, 54). The numbers and rates of divorce declined from 1982 to 1985, which suggests that some couples might have postponed their divorce in anticipation of legislation that would further liberalize access to it. Indeed, the 1986 Divorce Act made breakdown of the relationship the sole ground for divorce and reduced the evidence required to support the claim.13 During the two years after introduction of the new law, the numbers and rates of divorces rose dramatically: in 1985, there were 1,040.2 divorces per 100,000 legally married couples; in 1987, the peak year, there were 1,585.8 divorces per 100,000 legally married couples.

Divorce rates declined and levelled off in the 1990s, however, and the 1995 rate of 1,222 divorces per 100,000 legally married couples was not much higher than the 1982 rate of 1,215 (Gentleman and Park 1997, 55). For 2004, Statistics Canada reported a divorce rate of 10.6 per thousand legally married couples.14

Divorce produces effects of many kinds for spouses, children and extended family members. Its chief legal effect, one with instrumental and symbolic resonance, is the change in the marital status of the spouses. Its chief economic effect is the division of property and income between two households. Divorcing spouses may take into account a wide range of rules, including religious precepts, economic imperatives, social rules and state laws. Whether it is negotiated or, failing agreement, decided by a judge, a divorce settlement often draws on two bodies of legal rules: provincial legislation on the division of matrimonial property and federal divorce legislation on spousal support, child support and child custody.

The rules for the sharing of property typically grant each spouse an automatic entitlement. The point applies to equalization of family property in the common-law provinces and partition of the family patrimony in Quebec. The various provincial regimes are uniform in presuming an equal sharing of the increase in those assets during the marriage,15 although they differ somewhat in the basket of assets on which they operate (Payne and Payne 2006, 445-6; Pineau and Pratte 2006, 199-281). Crucially, the definitions of relevant property include pensions, although valuing them can be difficult (Martel 2003; Law Commission of Ontario 2008).16 The division of property between spouses reflects a legislative commitment to the idea that, whatever their role in the specialization of labour, spouses contribute equally to the marriage, which is viewed, unromantically, as a joint economic enterprise. It follows from this view that the spouses appropriately share its fruits. Indeed, legislation refers to “spouses,” without distinguishing husbands from wives, although provincial legislatures sought to remedy the injustice suffered by women who, on marriage’s end, faced economic precariousness. In crafting the rights and duties of married spouses, legislatures faced policy choices concerning the use of obligatory rules as opposed to rules the parties can alter by contract. These choices have resulted in an important distinction between common-law provinces, where spouses, by contract, may alter the rules of matrimonial property that apply to them,17 and Quebec, where spouses cannot exempt themselves from the rules of the family patrimony implemented in 1989.18 Both the common-law and civil-law regimes, however, recognize the importance of the matrimonial home, and it is possible, pending dissolution of the union, for one spouse to obtain an order for occupancy (Conway and Girard 2005; Pineau and Pratte 2006, 310-11).19

What is striking is that, simultaneously with the enactment of these rules on matrimonial property, the rate of marriage has declined. Throughout the 1960s, more than nine women out of ten would marry over the course of their life; by 2000, only 60 percent of women (and less than 40 percent of those in Quebec) were expected to marry at least once (Le Bourdais and Lapierre-Adamcyk 2004, 930). Thus, the proportion of adult unions affected by these rules on relationship breakdown has diminished significantly.20

Distinct from provincial regulation of spouses’ property, the federal Divorce Act addresses spousal support, authorizing a court to make an order that it thinks “reasonable” for support of the other spouse.21 This discretion makes plain that, unlike the presumption of equal division of property, spousal support does not operate as of right. A spouse who claims support from the other must demonstrate entitlement to support as well as the appropriateness of the amount sought. Parliament listed three factors that judges must consider when exercising their discretion: the length of time the spouses cohabited, the functions performed by each during cohabitation and any order or agreement relating to support.22 Moreover, a spousal support order should recognize any economic advantages or disadvantages to the spouses arising from the marriage or its breakdown, apportion between the spouses any financial consequences arising from child care that are not addressed by child support, relieve any economic hardship of the spouses arising from the breakdown of the marriage and, insofar as is practicable, promote each spouse’s economic self-sufficiency within a reasonable time.

The broad outlines of the federal legislation require judges to fill in the details of the Canadian law of spousal support. Beyond the vague reference to “reasonable” support, the legislation can be understood as reflecting several models of marriage and understandings of the basis of the obligation (Leckey 2002). Case law thus plays an especially large role. Moreover, while the legislative text has remained unchanged, the case law has changed significantly as the Supreme Court of Canada emphasizes one aspect of support, then another (Rogerson 2004). In 1992, in its landmark judgment in Moge v. Moge,23 the Court ordered support to a former wife who, though nearly 20 years had passed since the couple had separated, was still unable to support herself. The Court held that no single factor or objective takes priority — that is, in appropriate circumstances, the need to promote the parties’ self-sufficiency did not rule out long-term support. The judges held that the Divorce Act requires a fair and equitable distribution of resources to alleviate the economic consequences of the marriage or of its breakdown. In particular, the Court underscored the importance of spousal support for compensating a spouse for losses connected to the marriage.

In 2001, in response to concerns about the uncertainty in the law of spousal support, the Department of Justice asked two specialists in family law, Rollie Thompson and Carol Rogerson, to develop Spousal Support Advisory Guidelines. The guidelines do not have the force of law; rather, they are intended as a starting point for negotiations by spouses and their lawyers and for judges. The intention was that the guidelines would reflect the existing law, rather than change it.24

Spouses typically negotiate a global settlement, dealing simultaneously with child custody, property division and spousal support. Such negotiations, however, may disadvantage women: in exchange for concessions they see as benefiting the children, women may concede their economic entitlements (Martin 1998).

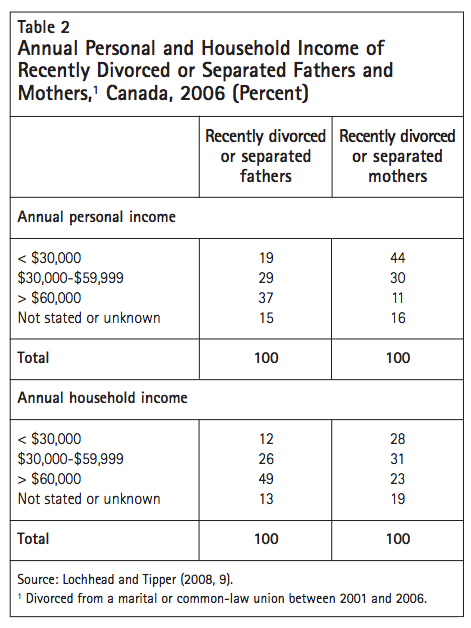

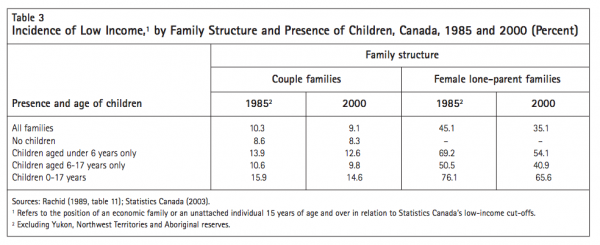

Indeed, despite the concern for equality in the distributive rules of family law, recently divorced or separated mothers remain financially worse off than recently divorced or separated fathers. As table 2 shows, 44 percent of recently divorced or separated mothers have an annual personal income of less than $30,000, contrasted with 19 percent of recently divorced or separated fathers. Moreover, 28 percent of recently divorced or separated mothers have an annual household income of less than $30,000, compared with 12 percent of recently divorced or separated fathers. Further, as table 3 shows, there is a high incidence of low income for families with children headed by a single female parent. Despite improvements over the past 20 years, the economic disadvantage of single-parent families headed by women has persisted. The causes are doubtless complex, and the picture necessarily must take into account the rules on the support of children (discussed in a later section). Before taking up that matter, however, it is appropriate to consider problems raised by the contemporary pluralism of Canadian families, which has effects both within marriage and beyond.

So far, the study has treated marriage primarily from the perspective of state law, viewing marriage as a civil institution. This section, however, addresses sources of friction between religious family practices and state regimes by looking at the issues of religious dispute resolution in the family setting and polygamy.25

To what extent should legislatures and policymakers care about the influence and use of religious norms as family members attempt to resolve disputes? Recent public debate has focused on recourse to religious, notably Muslim, norms and on the use of religious arbitral forums. The suitability of religious norms and forums, however, must be contextualized in relation to the scope for private ordering in family matters more generally.

Provincial and federal regimes present considerable scope for parties to negotiate and conclude agreements that depart from the legislated default rules (Roy 2006a; Tétrault 2007b).26 Where children are concerned, other rules apply, and courts assume a greater supervisory role. There is also significant scope in some provinces for alternative dispute resolution outside courts, through mediation and arbitration.27 Use of these possibilities by Christians on the ostensibly “secular” ground of individual choice typically attracts little media or other attention, even if one spouse receives a distribution that is less than she would have obtained under the default rules of the state regime or in a court.

By contrast, recourse to rules deriving from Islamic sources and arbitration in a religious forum have caused much more controversy (Macklin 2005; Ryder 2008, 104-6). In reaction to public outrage over the possibility of so-called sharia courts, Ontario amended its law in 2006 so as to specify that family arbitrations may be conducted only in accordance with the law of Ontario or of another Canadian jurisdiction (Razack 2007; Weinrib 2008).28 Some scholars have rightly expressed concern that rules prohibiting the recourse to religious norms or the use of religious arbitral forums are likelier to drive practices underground than they are to eradicate them (Macdonald and Popovici 2007; Shachar 2008). Moreover, while religious arbitration may have no legal force in Ontario, mediation remains a viable method for couples intent on using religiously based dispute resolution mechanisms. The mediation option suggests that “nothing has fundamentally changed for Muslim women whose vulnerability to bad faith husbands and patriarchal imams was the central concern of opponents to Sharia arbitration” (Emon 2009, 420). The shift underground of practices following such a legal reform is notoriously difficult to track and calls for careful empirical inquiry.

While the ways in which religious practices may adapt to law reforms is a concern, the larger point is that a focus on religious norms and arbitration in the resolution of family disputes risks exaggerating the distinctiveness of religion for family policy. In fact, divorcing spouses may exact and receive less than their statutory entitlement for a host of reasons, some of which rightly may engage public policy. The hostile reaction to the idea of religious arbitration in Ontario seemed, however, without conclusive evidence, to take religious norms as the most pressing reason a divorcing woman might claim and receive less than her fair share of household resources. Moreover, criticisms of religious arbitration forums unfolded against an unfounded assumption that the civil courts are easily accessible and affordable for family justice; in reality, many barriers prevent individuals — be they Muslims, Jews, members of another religion or nonbelievers — from going to court to enforce their rights (Macdonald 2003). For family policy, the pressing issue is the access of vulnerable individuals, especially women, to information and other support services as they undergo relationship breakdown. These needs transcend enculturation in one religious tradition or another.

The second point of friction at the intersection of religious marriage and state law relevant for present purposes is polygamy. The practice of polygamy poses difficult policy questions in fields such as criminal law, family law, immigration, taxation and social policy (see, for example, Bailey et al. 2005; Campbell 2005). Separating the strands in reference to this paper’s key oppositions helps clarify the issues for debate, although it is only a preliminary step.

In the public-law terms of the criminal law, practising “any form of polygamy” or entering into “any kind of conjugal union with more than one person at the same time” remains an offence punishable by up to five years in prison.29 The charges recently laid in Bountiful, British Columbia, likely will lead to a testing of this criminal prohibition against the guarantee of religious freedom in section 2(a) of the Charter (Meissner 2009). Turning to private law, with an instrumental focus on the distribution of resources among family members, the drafters of family law must consider whether to enforce support duties arising from a polygamous marriage validly celebrated abroad. For example, Ontario’s Family Law Act includes, in its definition of “spouse,” a marriage that is actually or potentially polygamous if valid where it was celebrated.30 An individual in such a polygamous marriage could seek an order in Ontario for support from another “spouse.” Distinct from this distributive question, another private-law matter engages family law’s symbolic dimension: should the federal definition include polygamous unions as civil marriages? What, if anything, does the recognition of same-sex marriages entail for polygamous unions (Leckey 2007b; Galloway and Matas 2009)?

Additional instrumental considerations play out in public-law fields such as immigration, taxation and welfare policy. The immigration problem includes whether rules relating to sponsorship and family reunification should take into account the bonds of foreign polygamous marriages. Taxation and social policy issues include the extent to which the rules defining tax credits and entitlements should take into account polygamous marriages. What is the appropriate posture in relation to a religious polygamous marriage of a state regime that confers a benefit on a contributor’s surviving married or common-law spouse? The example of Bountiful shows that at least some people in Canada practice polygamy. This fact should prompt policymakers to consider the extent to which their role is to respond to existing family practices as opposed to directing them.

This brief overview of some frictions between civil and religious marriage law sets the stage for discussion of another kind of pluralism — that of adult relationships outside marriage. The connection is that, in both cases, difficulties can arise from a policy focus that takes the civil marriage regime as paradigmatic.

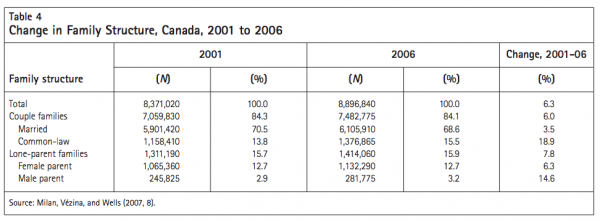

As table 4 shows, married-couple families remain the most common family structure, constituting 68.6 percent of all families in the 2006 census (down from 70.5 percent five years earlier). Within the set of married-couple families, the largest family structure is that of married couples with children ages 24 and under, representing 34.6 percent of total census families (Milan, Vézina, and Wells 2007, 11). Collectively, however, Canadian families are more plural in form than they were several decades ago. The census in 2006 for the first time enumerated more unmarried people ages 15 and over (51.5 percent) than legally married people; 20 years earlier, 38.6 percent of the population ages 15 and over was unmarried (Milan, Vézina, and Wells 2007, 19). How do these forms of family outside traditional marriage fit into the landscape of family law?

In 2001, the Law Commission of Canada collected four legal models used for regulating adult personal relationships: marriage, private law, ascription and registration (xvi). Box 1 summarizes them.

With reliance, in varying measures, on the models of marriage, ascription and registration, Canadian family law in recent decades has gradually recognized two new kinds of couples beyond the traditional, married, opposite-sex couple.31 One is the unmarried, cohabiting, opposite-sex couple,32 known in Quebec as the de facto union. The other is the same-sex couple.33 The legal recognition of these types of couples is the product of judicial and legislative activity. Together, their stories show more concretely the promise and risks of the four legal models. They also provide revealing case studies of the movement and tension between dimensions of family law: public law and private law, instrumental and symbolic, and formal and functional. These examples of family law pluralism also connect with the political ideals of formal and substantive equality, measured within individual couples and from one group of couples to another.

The discussion develops across three subsections. The first two address, respectively, unmarried couples and same-sex couples. The third makes explicit the grip of the past in the underlying assumption of marriage as the paradigmatic adult relationship.

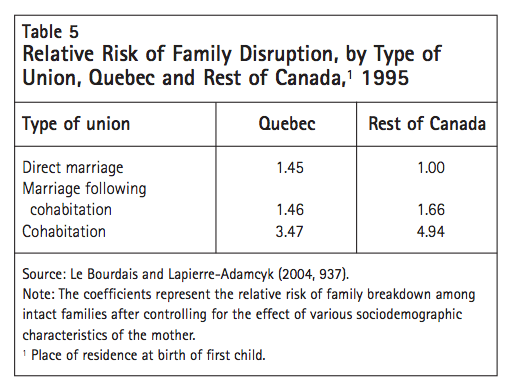

From the 2001 census to that in 2006, the number of unmarried-couple families grew by nearly one-fifth (18.9 percent), a rate more than five times faster than that for married-couple families (see table 4). In 2001, unmarried-couple families accounted for 13.8 percent of all census families; by 2006, they were 15.5 percent. Two decades ago, however, they accounted for only 7.2 percent of all census families (Milan, Vézina, and Wells 2007, 9). This sustained increase in the incidence of unmarried couples hints that they might present a matter for further attention by policy-makers. Indeed, as table 5 shows, unmarried cohabitants have a much higher probability of union disruption than do married couples.

Most provincial legislatures have used the ascription model for unmarried couples. In the common-law provinces, legislation requires unmarried cohabitants to support each another; the duty persists after cohabitation ends.34 As evidenced by legislative debates, the objective in most instances was not primarily to recognize the intrinsic worth of unmarried cohabitants as an identity group or to affirm their equality to married couples, but, instrumentally, to palliate the vulnerability of women who had lived with men with a view to reducing claims to public assistance.35

Although this policy choice has been widely adopted, analogizing unmarried and married couples for the assignment of duties can cause difficulties and surprises. Unlike married spouses, unmarried cohabitants have no formal marker of their relationship; legislatures wishing to regulate them thus need a proxy for their commitment. A typical choice is continuous cohabitation for a given period, such as three years. An alternative basis may be living “in a relationship of some permanence” and having a child together.36 A criterion of cohabitation for a specified period, however, is more likely to cause disputes over evidence than a criterion of marriage or registration. On the breakdown of the relationship, members of an unmarried couple may disagree on when they really began living together and, thus, whether they crossed the statutory threshold.

Another surprise can come when the partners stop living together. Marriage brings a legal status that persists even when the spouses have separated; the legal bond of marriage survives until dissolved by the death of one spouse or by a divorce judgment. By contrast, a cohabitation relationship, which is recognized on a functional basis, does not survive in a comparable way the physical separation of the parties and the intention of one of them that it should end. Thus, by terminating a cohabitation relationship, an individual loses his or her claim, for instance, to a survivor’s pension under the Canada Pension Plan on the partner’s death. In other words, government programs treat a former common-law partner like a divorced spouse, not like a separated married spouse.37

Alone among the provinces, Alberta has used the ascription model to attribute support obligations to a set of relationships larger than conjugal cohabitants. That province’s scheme of “adult interdependent relationships,” adopted in 2002, includes relationships outside marriage in which two persons share each other’s lives, are emotionally committed to each other and function as an economic and domestic unit. There is no sexual requirement.38 Alberta designed this scheme so as to comply with its constitutional obligations regarding same-sex couples arising from a legal case known as M. v. H.39 After the judgment in that case, the provincial government resisted elevating same-sex couples alone to a position equal to that of opposite-sex cohabitants (Alberta Law Reform Institute 2002), which suggests that, in its view, the instrumental extension of rights and duties to gay and lesbian couples on a functional basis risked validating them. Consequently, the government drafted a more widely cast regime that includes not only same-sex cohabitants, but also some nonconjugal couples who live together, such as two friends. The regime has the advantage of loosening the legislative grip on conjugality as the key indicator of legally relevant relationships (Cossman and Ryder 2001), but it also risks surprising individuals who do not see themselves as tacitly assuming obligations toward a person with whom they live (Bala 2003, 903). Because the scheme is relatively recent, its wider impact remains to be seen.

On the question of spousal support for unmarried couples, Quebec provides a glaring contrast. As in the other provinces, public-law legislation enacting social programs in Quebec, such as workers’ compensation, treats de facto spouses similarly to married spouses in most respects (Tétrault 2005, 549-51) — that is, for instrumental purposes, the public law of the family recognizes unmarried couples on a functional basis. Under the private law, by contrast, de facto spouses, as such, owe each other nothing (Moore 2003, 76-86) — in lawyerly jargon, they are legal strangers one to another. This state of affairs reflects a legislative choice to confine the family regulation within the Civil Code almost entirely to those relationships recognized by formal means. The result is that, in Quebec more than in any other province, the set of family relationships recognized by the private law for instrumental purposes is identical to the set recognized for symbolic purposes.

The Civil Code’s silence regarding the duties of de facto spouses is especially striking given the prevalence of unmarried cohabitation in Quebec.40 According to the 2006 census, unmarried couples represented over one-third (34.6 percent) of all couples in the province, a much higher proportion than in the other provinces and territories (13.4 percent).41 The increase in the incidence of unmarried couples in Quebec from 2001 to 2006 was 20.3 percent (Milan, Vézina, and Wells 2007, 35). As table 5 shows, the relationships of unmarried couples in Quebec appear to be somewhat more stable than those of unmarried couples elsewhere in Canada, but the likelihood of the disruption of such relationships is still three and a half times higher than for married couples elsewhere in Canada.

Matrimonial property provides a contrast with the support regimes in force in all provinces but Quebec. Most provinces restrict their matrimonial-property regimes to married couples and, typically, no rules call for the sharing of assets when cohabitation ends. In the late 1990s, a former cohabitant in Nova Scotia challenged the constitutionality of her province’s exclusion of unmarried couples from its matrimonialproperty regime and won her case in the provincial court of appeal. Following that judgment, the legislatures of Manitoba and Saskatchewan amended their statutes so as to include unmarried couples in their matrimonial-property regimes.42 On further appeal, however, the Supreme Court of Canada reversed the holding that restricting the regime of matrimonial property to married couples discriminated against unmarried couples. In 2002, in Nova Scotia (Attorney General) v. Walsh,43 it upheld the distinction on the basis that only married couples had chosen to subject themselves to the onerous rules of property division. The class of unmarried cohabitants, held the majority of the Court, was diverse and it was impossible to presume their consent to the regime.

Consequently, unless they have made arrangements by contract, unmarried cohabitants have relatively little protection in property matters. They may make a claim under the general private law, however, and have had modest success in claims of unjust enrichment (Lefrançois 2005, 51-5; Payne and Payne 2006, 60-1).44 Such claims require case-by-case demonstration of three elements: impoverishment on the part of the claimant, a corresponding enrichment on the part of the respondent and an absence of juristic reason, such as a contract, for the wealth transfer. Claims in unjust enrichment are most useful where one partner has contributed tangibly to significant property owned by the other. Overall, however, the recourse to claims of unjust enrichment is far from a full substitute for the equalization of family property or partition of the family patrimony available to married spouses.

In addition to the use of the ascription model, several provinces provide registration options for partners who do not wish to marry or cannot do so. Registration schemes for domestic partnerships have been available since 2000 in Nova Scotia and since 2002 in Manitoba (Roy 2002b).45 Alberta’s regime, noted earlier as an instance of the ascription model, also has a registration component: two adults, including those who are related by birth or adoption, may enter into an adult interdependent partnership agreement and thus may invoke the provisions that would apply by ascription to couples who satisfy the statutory criteria.

Quebec enacted its own alternative to marriage, the civil union, in 2002.46 It is more than simply a registration scheme, however; drawing on the symbolic affirmation associated with marriage, the Civil Code refers to a civil union’s “solemnization” (Kasirer 2003). It is available to both same-sex and opposite-sex partners, and its rules incorporate the legal regime of marriage, including the obligatory rules of the family patrimony.47 Unlike marriage, however, which requires a divorce judgment, a civil union can be consensually dissolved by a notarized joint declaration by the spouses.48

At the time they were introduced, the registration schemes just noted provided a formal recognition option for same-sex couples who, under federal law, could not yet marry (Moore 2002b; Fisher et al. 2004). Now, same-sex couples are recognized within Canadian family law on footing identical to that for opposite-sex couples. As recently as 1995, however, in Egan v. Canada,49 the Supreme Court of Canada rejected a claim that Old Age Security, a distributive program structured by public law, discriminated unjustifiably on the basis of sexual orientation by excluding same-sex couples.

In contrast, the first major Charter success before the Supreme Court relating to recognition of samesex relationships concerned the private law of the family. In M. v. H.,50 the Court heard a claim of a former member of a lesbian cohabiting couple that it was sexual-orientation discrimination, contrary to section 15 of the Charter, for Ontario to ascribe a spousal-support regime to unmarried, opposite-sex couples while ascribing no such regime to unmarried, same-sex couples. The regime to which the claimant sought access reflected an instrumental goal of addressing women’s economic vulnerability so as to reduce demands on the public purse. The claimant contended that, where the legislature recognized unmarried, opposite-sex couples on a functional basis, it should recognize same-sex couples on the same basis. The other woman opposed the claim, resisting the retroactive characterization of their relationship, on a functional basis, as marriage-like.

The Court agreed with the claimant. It referred to family law’s instrumental and symbolic roles, and acknowledged that its judgment would reduce the claims on public resources by former members of same-sex couples. But, consistent with its case law on section 15 of the Charter,51 it framed its judgment as a glowing, symbolic validation of same-sex couples’ worth and commitment (Cossman 2002a,b). Combining different bases for regulating family in an arguably problematic way, the Court used the language of dignity and recognition more typically associated with formal, consensual bases for regulation, such as marriage, than with the functional basis of ascription. In the Court’s view, ascribing duties to unmarried couples without their consent upheld their dignity and enhanced their self-worth.

In response to M. v. H., Parliament and provincial legislatures brought their regimes in line with the Court’s holding that distinctions between unmarried couples on the basis of sexual orientation were unconstitutional (Cossman and Ryder 1999).52 Ontario, for instance, added a new category, “same-sex partner,” to its Family Law Act.53 Quebec replaced gendered definitions for couples in more than two dozen statutes with a gender-neutral definition of de facto union.54 Consequently, where spousal-support regimes attach to opposite-sex couples who live together, they also attach to same-sex couples who do so. The different forms of the legislative responses to M. v. H. — including Alberta’s innovation detailed above — show awareness that even the instrumental recognition of same-sex couples on a functional basis had symbolic resonance.

Several years later, the focus of advocacy shifted to marriage, with the next generation of claims squarely targeting the state’s symbolic affirmation in the formal institution of marriage. Thus, recognition of same-sex couples as family for instrumental purposes in M. v. H. paved the way for their symbolic recognition (Leckey 2007d). Lawsuits in a number of provinces led to declarations that the opposite-sex requirement for marriage violated the Charter on the basis of sexual orientation.55 Parliament eventually passed legislation making it possible across the country for same-sex couples to marry civilly.56 Canada’s recognition of same-sex couples has put it, along with countries such as the Netherlands, Spain and South Africa, at the cutting edge of family developments (Wright 2006; Bamforth 2007).

From a policy perspective, same-sex couples may have merged onto the general terrain of family law, but viewed in the light of the impact of same-sex marriage on public discourse, their numbers are not high, representing 0.6 percent of all couples in the 2006 census.57 Married same-sex couples, who amounted to 16.5 percent of all same-sex couples in 2006 (Milan, Vézina, and Wells 2007, 12), have the benefit and burden of spousal support and division of matrimonial property. Unmarried same-sex couples fall under whatever legislative regime operates in their home province.

With the adoption of these instrumental and symbolic forms of recognition, it might be that sexual orientation is no longer a salient criterion for identifying policy challenges. The financial vulnerability of a same-sex partner after a long relationship with a specialization of labour may be the same as that of an opposite-sex spouse.58 Indeed, although one might suppose that same-sex relationships escape the negative effects for women associated with opposite-sex marriage, sociological inquiry shows that, over time, many same-sex couples assume a specialization of labour similar to that of opposite-sex spouses, one that is reflected in different earnings (Carrington 1999). Moreover, lesbian couples might be expected to exacerbate the impact of women’s lower earnings relative to men’s: female same-sex couples might bear the brunt of a gendered labour market, with neither partner appearing in the better-paid category.

While the legal situation of same-sex relationships seems to have stabilized, the position of unmarried couples in Quebec has recently made headlines. As noted in the introduction, in January 2009 a trial took place in Montreal of a former de facto spouse who sought inclusion in federal and provincial marriage laws (Peritz 2009). With a view to receiving $50 million of her former partner’s assets and $56,000 per month in alimony (distinct from the child support she receives from her former partner for their children), she made three constitutional claims. First, it was unconstitutional for the Civil Code’s spousal-support regime not to include de facto unions. Second, it was unconstitutional for the Civil Code’s family patrimony rules not to extend to de facto unions. This claim appears contrary to the Supreme Court of Canada’s judgment in Walsh,59 although the legal context differs from that present in that Nova Scotia case (Leckey 2009a). These two claims required the court to find that it is discriminatory to apply an instrumental family policy to couples recognized formally but not to couples recognized functionally. The third claim was that it was unconstitutional for Parliament’s Civil Marriage Act not to include, as married, partners who have lived together for three years. This claim engaged the symbolic affirmation associated with marital status, attacking the constitutionality of a status secured by exclusively formal means.

Given the resources available to both parties, and in particular the stated intent of the claimant’s lawyer to change family law, the case is unlikely to be settled for some time. But this lawsuit unfolds against a larger backdrop, and provides an occasion for reflecting on the appropriate treatment by lawmakers and policy-makers of relationships outside traditional marriage. In recent years, a number of scholars have called for revision of the legal position of unmarried couples in Quebec (Jarry 2008). Others, emphasizing liberty and choice, protest the illegitimacy of imposing duties on individuals without their consent (Roy 2002a, 883; Mrozek 2009). What issues should be borne in mind for policy reflection?

A significant factor is the impact of the existing rules on children. A focus on the choice or autonomy of adults allows little space in which to discuss the effect of parents’ marital status on their children. In determining the duties of parents to their children, Canadian legislatures do not distinguish married from unmarried parents, as we will see in a later section. Yet, in most provinces, the legal treatment of unmarried cohabitation does result in disadvantages for children whose parents are not married. The protections of marriage — chief among them the possibility of one spouse securing exclusive possession of the matrimonial home — indirectly benefit the children of married parents over those of unmarried parents.60

How many children are affected? In Canada, the proportion of married couples with children ages 24 and under far exceeds that of unmarried couples with children those ages (34.6 percent versus 6.8 percent). Nevertheless, significant numbers of children are raised in unmarried-couple families: according to the 2006 census, of all children ages 14 and under living in private households, 14.6 percent lived with parents in a common-law union, more than triple the proportion of two decades earlier (Milan, Vézina, and Wells 2007, 11, 24). Concerns about the effects of parents’ unmarried cohabitation on their children are increasingly raised in Quebec (Goubau, Otis, and Robitaille 2003), where, by 2005, births outside marriage reached nearly 60 percent, up from approximately 10 percent in 1978 and less than 5 percent in 1951 (Le Bourdais and Lapierre-Adamcyk 2008, 85). Some Quebec judges have creatively conferred use of the matrimonial home on one de facto spouse on the basis of the children’s interests.61 Such orders show a judicial refusal to accept that the legislature’s preference for recognizing relationships on a formal basis should confine the scope for instrumental effects where children are involved. Still, it would be preferable for provincial legislatures to debate the matter and to regularize such a possibility (Tétrault 2008, 337).

Another factor is the privileged place of marriage as a point of reference. Indeed, the legal treatment of unmarried couples and same-sex couples has remained closely tied to the regulation of marriage, despite Canadian family law’s distinction as a frontrunner in recognizing the so-called functional family (Bala 1994; Millbank 2008b). Paradoxically, the response to the fact of greater pluralism in family form has been to treat more couples like married spouses (and more adults like parents). Yet the foundational category of marriage has passed largely unexamined (Polikoff 2008), though it remains the touchstone by which recognition of other relationships is measured and designed. Claims under the equality guarantee in the Charter, in fact, have solidified this approach, arguing that one group (unmarried couples, same-sex couples) is really the same as another group (married couples) and that governments should treat them as such. The policy question is typically framed in terms of a relationship’s assimilation into marriage, either total (in the case of samesex couples) or partial (in the case of unmarried cohabitants, for support but not for property). This approach, which Bottomley and Wong call a “logic of semblance” (2006, 42), allows little space in which to examine the needs and vulnerabilities flowing from a particular kind of relationship, viewed without reference to marriage.

The idea of treating additional categories of relationship partly or wholly like marriage has some negative effects on thinking about family, since features of the marriage model can be obstacles to identifying other relationships. More specifically, the privileged place of marriage as point of departure for policy analysis imposes three constraints on analysis. One constraint is conjugality: a focus on sexual intimacy makes it harder for policy-makers to assess nonconjugal relationships, such as, for instance, that of cohabiting siblings, for possible recognition as a family unit (Law Commission of Canada 2001).62 Policy analysis of cohabiting siblings or friends necessarily would separate the dimensions of public and private law as well as instrumental and symbolic purposes. In that case, concern for autonomy might well dictate that registration, as opposed to ascription, is most appropriate. And it might be that interpersonal duties and recognition by public programs — such as survivors’ benefits and tax exemptions for transfers of registered savings — matter more than a symbolic recognition.63

A second constraint the marriage model imposes on thinking about family policy is cohabitation. Researchers are just beginning to focus on couples “living together apart” — that is, partners who regard themselves as committed to each other but do not share a dwelling (Haskey and Lewis 2006). Still, even the most creative policy thinking about relationships often assumes cohabitation as an essential criterion. Douglas, Pearce and Woodward challenge this assumption, arguing that, if “function” is the basis of the claim for legal recognition, there is no adequate basis for excluding noncohabiting partners from protection: “confining a remedial jurisdiction to those living together re-imposes a type of ‘form’ as the qualifier for inclusion, creating a new ‘status’ of cohabitation and bringing us back to where we started” (2009, 29).

A third constraining feature of the marriage model is its all-or-nothing character, since its full legal effects attach immediately on celebration. Proxies for the commitment of marriage typically copy this on/off character — an unmarried couple either qualify for assimilation into the spousal-support regime applicable to married couples or they do not. Where the legislature has set a threshold of three years’ cohabitation, couples having lived together for a shorter time are invisible for legal purposes,64 while couples who cross the three-year threshold come suddenly into view. Yet a less blunt, more incremental approach might better advance the policy objectives associated with unmarried couples. Barlow and James (2004) argue that the commitment and economic reliance of unmarried couples deepens over time; it thus might be more appropriate for legislatures to ascribe duties incrementally, with increasing weight at several intervals or with the arrival of children. More sophisticated policy solutions might come from empirical study of the lives of unmarried couples, as Lewers, Rhoades and Swain (2007) suggest. Unlike the equality claim in Walsh or the 2009 challenge by the Montreal woman, such an approach would not take the form of a constitutional claim for access to marriage by unmarried couples seen as a single group.

Policy analysis also must take account of the diversity of unmarried couples. In 2006, common-law unions were more predominant, in absolute numbers, among individuals ages 25 to 29, although the most rapid growth of this form of family life between 2001 and 2006 occurred in older age groups, with the number of individuals ages 60 to 64 in unmarried, cohabiting couples rising by 77.1 percent (Milan, Vézina, and Wells 2007, 20-1). These two groups likely have very different needs, concerns and goals in not getting married. Some feminists also express caution about assuming that treating unmarried couples like married ones will produce an overall improvement in the situation of women (Bottomley and Wong 2006).

Rigorous attention to the different roles of family law and its private and public aspects is necessary for understanding the logic of reform and for avoiding perverse policy consequences. The strategic shifts evident in past advocacy for same-sex couples are revealing. When the objective was access to a regime of ascription, advocates advanced concern about addressing the economic vulnerability resulting from intimate relationships, and focused on the need to palliate, ex post, the fallout of reliance and investment in such relationships. They argued that the interests of the economically weaker members of same-sex couples aligned with those of the economically weaker members of unmarried, opposite-sex couples, who might not have had a meaningful choice about the status of their relationship. Once the Supreme Court of Canada required the inclusion of same-sex couples within the class of unmarried couples for support purposes, however, the discourse of gay advocacy shifted. Now, the objective became marriage, and advocates for same-sex rights took up the liberal language of choice consistent with an intentional, formal model of regulation, framing the push for same-sex marriage as a quest for the right to choose to marry, focusing on formal recognition resulting from an ex ante choice (Osterlund 2009). That divergence between same-sex couples and unmarried opposite-sex couples shows that those seeking equality under the Charter may not always share common interests (Leckey 2007a, 82-3).

The experience of same-sex couples invites caution on the part of policy-makers in redesigning private and public programs in response to equality claims. Following the federal amendments, individuals living with same-sex partners may have been surprised to learn that they were suddenly “spouses” for the purposes of various redistributive programs. Lahey (2001) shows that extending spousal treatment to lesbian and gay couples for federal income taxation, social assistance and retirement programs resulted in disproportionately higher taxes and reduced social benefits for those lesbian and gay couples with the lowest incomes. Thus, the net impact of the recognition that same-sex couples “achieved” may have been regressive in the sense of disadvantaging lower-income couples and benefiting higher-income ones (Young and Boyd 2006). To some extent, therefore, it appears problematic to justify, on the symbolic grounds of equal recognition, the application of redistributive rules to same-sex couples on a functional basis.

The larger point is that it is worth analyzing claims for changes to family law rigorously to see (a) whether the objective is instrumental or symbolic and (b) whether the proposed basis for recognition is formal or functional. Policy responses should pursue coherence in the sense that a new measure should be justifiable in the same dimension of family law that it aims to advance. Accordingly, after considering the position of unmarried couples with children and the vulnerabilities that arise when their relationships break down, one can draw two recommendations. First, all the provinces should regularize a mechanism by which a parent with custody of children can secure an order for temporary possession of premises that have been used as the family home, irrespective of which partner owns or rents it. Concerns about autonomy and consent have least application here, because the children have neither chosen nor consented to the marital status of their parents. The second recommendation, which is based on the economic vulnerability of women with children, is that Quebec should provide for an obligation of support between de facto spouses who have a child together.

Both recommendations are instrumental in the sense that they aim to palliate vulnerability, and they are justifiable on functional bases. Neither recommendation has as its aim the symbolic validation of the worth of unmarried couples; moreover, given their limited scope, neither follows the logic of semblance by assimilating a category of relationship into marriage. Restricting the obligation of support recommended for Quebec to unmarried couples who have had a child together would take account of the diversity of unmarried couples. For example, such an obligation would not affect childless cohabitants in their twenties who are roughly equal in their economic position. Nor would it interfere with the economic relations of older cohabitants, such as those who have already been married and divorced and wish to avoid the legal consequences of marriage. In any case, this indication that the position of adult relationships cannot be considered without reference to the presence of children leads to the next section, which addresses directly the legal relations between parents and children.

Legal parentage or filiation is the relationship of parent to child in virtue of which laws attach rights and obligations. Unsurprisingly, parentage has complex effects within family law and policy. It directly engages three crucial oppositions: private versus public family law, instrumental versus symbolic recognition and formal versus functional bases for identifying family relationships. Consequences attach to parentage and filiation within the private law of the family in the form of parents’ and children’s reciprocal rights and duties as well as parents’ responsibilities and powers vis-à-vis their children. Within the public law, governments take parental bonds into account in a number of ways, from tax credits to reducing welfare entitlements. Parentage and filiation operate instrumentally, for distributive purposes, and also symbolically, in the sense of the intrinsic worth of the parental bond.65 Formal and functional bases play out in complex ways. A formal basis for recognition of a parental bond operates in, for example, the registration of a declaration of birth. Functional bases for recognizing a parent-child relationship operate in two ways. One is that some means of establishing the full legal status of parentage or filiation are functional — for example, acting like a parent can lead to a presumption that a person actually is a parent. The other way is that, without leading to parental status, functioning as a parent can also lead to the conferral of some parental rights and duties.

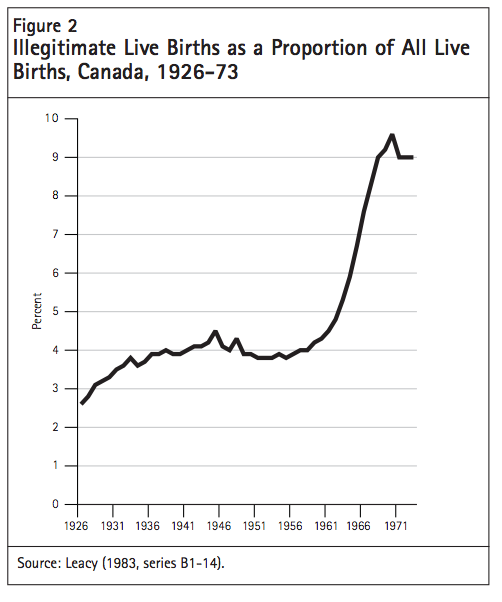

Historically, children’s status reflected their parents’ relationship. Until the 1970s, the marital status of the parents determined the child’s legal status: children born to married parents were “legitimate,” while those born to unmarried parents were “illegitimate” and suffered social stigma and legal disadvantages. In some circumstances, illegitimate children could claim support from their parents, but could not inherit from an intestate succession, nor did they become members of the larger family defined by kinship. That state of affairs showed legislatures responding, in a functional way, to the support needs of illegitimate children while withholding from them kinship’s symbolic recognition. By the 1960s, however, the percentage of illegitimate living births began to rise sharply (see figure 2), and in the 1970s and 1980s, legislatures abolished the status of illegitimacy.66 Filial bonds now connect children directly to parents, largely unmediated by marriage — that is, children’s parentage can be determined without reference to their parents’ marital status; moreover, the content of parental duties does not depend on marital status.

Meanwhile, the early twentieth century had witnessed the enactment of adoption statutes.67 One of adoption’s initial functions had been to fold illegitimate children into legitimate families. Another had been to provide families for the numerous abandoned children living in religious or other institutional care (Lavallée 2005; Roy 2006b). It took several stages of legislative amendment for legislatures to establish that adopted children are full members of their adopted families. Initially, there was resistance to viewing adopted children as fully equal to those born within marriage. Now, however, adoption produces the full effects of “natural” parentage. It thus pursues both an instrumental policy of providing security for children and a symbolic policy of validating the relationship as a legal family bond.68