On October 25, 2013, the Institute for Research on Public Policy, with support from Elections Canada, Samara, the Maytree Foundation and the Centre for the Study of -Democratic Citizenship at McGill University, held a workshop on the electoral and civic involvement of Canada’s immigrant communities. The event was held at the Samara offices in Toronto, and the more than 30 participants included academic experts, government officials, former political party activists and representatives of a variety of nongovernmental organizations. The program, presentations and list of participants are available here (at https://irpp.org/en/events/electoral-involvement-immigrants).

Why does this issue matter?

In order to understand the electoral and civic involvement of Canada’s immigrant communities, it is important to define the terms. Simply put, electoral involvement refers to voting and holding public office. However, it has many different dimensions, including candidate selection and recruitment, and attitudes towards elections and elected representation. The bulk of previous work on these issues has tended to focus on the degree to which minority groups’ elected representation matches their proportion of the population. This focus is important for two reasons. First, diversity in elected representatives sends a powerful message of inclusion to minority groups. Second, a large body of research has shown that diverse representation can lead to different policy outcomes. Representatives from minority group backgrounds tend to raise different issues for the public agenda and bring unique perspectives that have an impact on decision-making.

Civic involvement refers to participation in community organizations, including groups that primarily serve immigrants and those that help to “build bridges” -(particularly between immigrants and the receiving society). Civic involvement can thus contribute to immigrant integration. However, civic involvement is also an end in its own right.

It is important to distinguish between immigrant communities and visible minorities. The term “visible minority” has its origins in the federal Employment Equity Act and is widely used by Statistics Canada in official population figures. In essence, it refers to people who are neither white nor Aboriginal. Statistics Canada specifically identifies the following subgroups as visible minorities: “Blacks, Chinese, Filipinos, Japanese, Koreans, Latin Americans, Pacific Islanders, South Asians, and West Asians/Arabs.”1

This definition of visible minority groupings can be problematic for studying representation. For example, it includes subgroups that have their origins in one country (e.g., Japanese) as well as those whose members have origins in many countries (e.g., Blacks). In the latter case, members’ experiences may vary considerably. Despite its shortcomings, it is typically the standard category in research on immigrant communities’ electoral and civic involvement. In this report, we use the term “immigrant communities” — a term intended to encompass a broader population, including those who may not be captured by the “visible minority” definition as well as the descendants of immigrants — except where we report on research that uses visible minorities as the measure.

Trends in Representation

One of the most fundamental types of representation concerns the ability of citizens to see people like themselves among elected office holders. This is often called “descriptive” or “mirror” representation. Research in the United States has shown that, for some historically marginalized groups, seeing people from their own group in elected office fosters confidence in the political process. There is also some evidence that, in carrying out what is termed “substantive” representation, minority office holders focus on different policy issues from their colleagues.

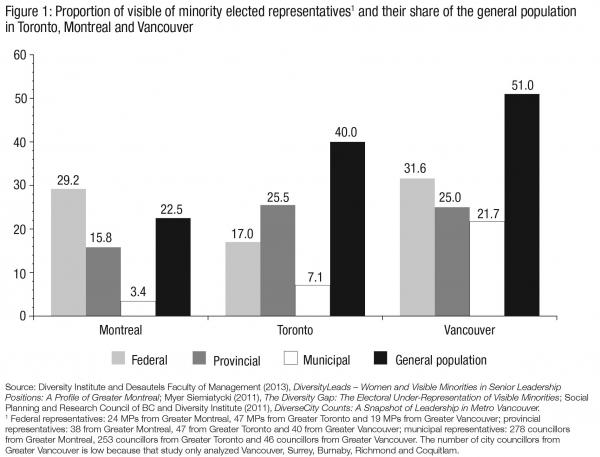

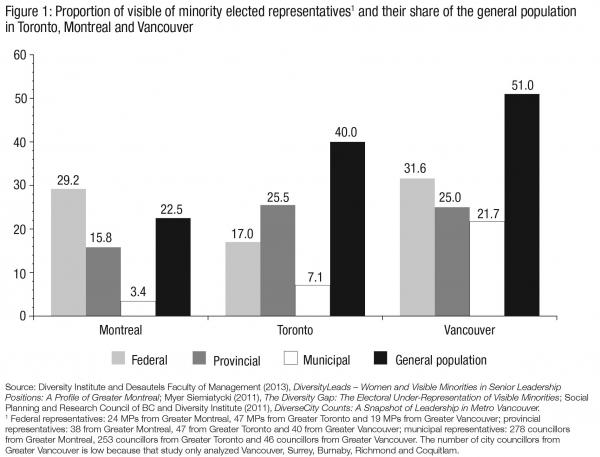

Recent research presented at the workshop compared the proportion of elected officials in a set geographic area with the demographic makeup of that area, with a focus on Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver (in 2011, 63 percent of immigrants resided in those three census metropolitan areas). Although this method has some limitations, the presentations highlighted a number of major findings:

- The number of foreign-born and visible minority elected officials is in most cases lower than their share of the population. Livianna Tossuitti and Jane Hilderman reported that, following the 2011 election, 9 percent of federal MPs were from visible minority groups, even though visible minorities made up 19 percent of Canada’s population, according to the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS). They noted that the parties differ considerably in their proportions of visible minority MPs:

- Following the 2011 election, the NDP had the highest proportion of visible minority MPs — 14 percent of their caucus. The NDP has an affirmative action policy that includes targets for candidate recruitment from under-represented groups. For women, the target is 60 percent of ridings where the NDP has a reasonable chance of winning; for other under–represented groups, including visible minorities, it is 15 percent.2

- The Liberal Party had the lowest proportion of visible minority MPs among the three largest parties in the House of Commons, at 6 percent.

- The proportion of visible minorities in the Conservative caucus was slightly higher than that in the Liberal caucus, at 7 percent.

Tossutti and Hilderman noted that some visible minority MPs are given additional appointments, such as cabinet or parliamentary secretary positions. However, one participant suggested that looking only at the number of such appointments could lead us to overestimate the clout of visible minority representatives in cabinet, since they may be more likely to have minor portfolios (as was in the case in the composition of the federal cabinet following the 2011 election).

Chima Nkemdirim pointed out that the Calgary area has seen enormous growth in its visible minority population in recent decades, almost doubling between 1996 and 2011 (from 16 percent to 28 percent). Indeed, according to the 2011 NHS, Calgary has the third-highest proportion of visible minorities (and of immigrants) among census metropolitan areas — in percentage terms, higher than Montreal. However, Calgary elected its first visible minority city councillor only in 2007. In both 2010 and 2013, two visible minority councillors were elected.

There was one exception to the trend of under-representation: Greater Montreal has a larger share of visible minority federal MPs than the corresponding share of the population. A combination of the NDP “orange wave” in the 2011 federal election and the party’s affirmative action targets could explain much of this result.

- Immigrant communities have widely varying levels of representation on federal, provincial and municipal governments. Two of the presentations, by Wendy

Cukier and Myer Siemiatycki, compared federal, provincial and municipal representation within a geographic area. In general, visible minorities are best represented at the federal and provincial levels and least represented on municipal councils (see figure1). In Greater Montreal, visible minorities make up 29 percent of the area’s federal MPs, 16 percent of the area’s MNAs but only 3 percent of the area’s municipal councillors.3 In the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), visible minority officials make up 17 percent of the area’s MPs, 26 percent of the area’s MPPs but only 7 percent of the area’s municipal councillors. In Greater Vancouver, visible minorities make up 32 percent of the area’s MPs, 25 percent of the area’s MLAs and 22 percent of the area’s city councillors.4

- Within metropolitan areas, certain areas — not necessarily in the downtown core — typically elect more visible minority representatives. Myer Siemiatycki illustrated that some parts of the GTA elected more visible minority representatives than others. The “905” suburbs (particularly Brampton, Mississauga and Markham) performed the best in terms of numbers, followed by the suburban areas of the City of Toronto (Etobicoke, North York and Scarborough). However, the vast majority (16 out of 25) of municipal councils examined in the GTA had no visible minority representatives at all.

- Areas with a high proportion of visible minorities do not necessarily elect visible minority representatives. Chima Nkemdirim pointed out that although Calgary has major concentrations of visible minorities in certain parts of the city (notably Chinese communities in northwest and central Calgary, and South Asian communities in northeast Calgary), these areas were not the ones where visible minority city councillors were elected. Instead, they came from areas where the largest group was not a visible minority.

- Some immigrant communities are better representated than others. Siemiatycki pointed out that treating visible minorities as an umbrella group can obscure major differences among communities. Within the GTA, four visible minority communities had no representatives at all: Arab, Filipino, Latin American and Southeast Asian. By contrast, the South Asian and Chinese communities have been relatively successful. Four federal MPs, seven MPPs and four municipal councillors in the GTA come from South Asian backgrounds. Chinese-background elected officials were more numerous at the municipal level: two-thirds of Chinese-background elected officials in the GTA were city councillors, and more than half of all the visible minority municipal councillors in the GTA are of Chinese background.

Despite these findings, a number of the participants questioned whether what is sometimes called “counting bodies” is an appropriate way to analyze the electoral representation of immigrant communities. Karen Bird argued that we should take into account the perspectives of immigrant communities in assessing the importance of descriptive representation. She conducted a series of nine focus groups with Chinese, Black and South Asian participants from the GTA. She used the Statistics Canada definitions for these groups, which led to Black focus groups consisting of people whose families had immigrated from a variety of countries. The Black participants nevertheless had shared experiences of discrimination. Bird suggested that these citizens do not necessarily want to be represented by people from the same group. However, when this does occur, those citizens tend to have higher expectations and are more disappointed when their representatives fail to meet them. These communities nevertheless seem to understand that party discipline limits elected representatives’ freedom to act.

Barriers to Electoral and Civic Involvement

Participants discussed a number of obstacles to the electoral and civic involvement of immigrant communities. These barriers can be institutional, as political parties and other organizations are often gatekeepers of electoral involvement, or they can be attitudinal. On attitudinal barriers, participants acknowledged that racism affects both how the host society interacts with immigrants and immigrant communities’ sense of acceptance by the host society.

- Back-room decision-making might explain some of the gaps in immigrant communities’ electoral representation. A number of participants suggested that researchers study the impact of riding associations on recruitment and nomination politics. It was observed that riding associations, while theoretically open to all, often see few changes in their active membership. Association executives may play favourites in choosing candidates or show lower levels of support for potential candidates because they are not white. Greg Sorbara suggested that while prejudice has diminished over time, it still exists, and provincial or national search committees could help correct for biases within riding associations.

- Political activists sometimes “colour code” areas when considering where visible minority candidates might run. Several participants noted the important role that ethnicity and race play in shaping such colour coding.

- Candidates from immigrant communities are often pushed to run in areas with large numbers of people who look like them. Myer Siemiatycki suggested in his presentation that candidates from immigrant communities are typically “ghettoized” into running in areas with high minority populations. Another participant echoed this, drawing on his own experience running for municipal office: he was told to run in an area that was associated with people who looked like him, even though he had not lived there and had no ties to that community. Siemiatycki noted that many of the ridings where visible minorities were candidates were ridings where multiple political parties ran visible minority candidates — often from the same ethnocultural group.

- Political parties want to win: Several of the presenters who had been involved with political parties, for example Greg Sorbara, Raj Sihota and Matt Smith, suggested that parties deliberately recruited people from particular immigrant communities to try to increase their chances of winning seats in areas with large populations from those communities. This can either help or hurt minority representation. Within the areas identified as places where parties “have to run” visible minority candidates, the practice may be useful for electing visible minorities; however, outside these areas, it might discourage electoral involvement.

- Sometimes visible minority candidates win outside colour-coded areas: Chima Nkemdirim referred to the election of Mayor Nenshi and two -visible minority candidates to the Calgary City Council in 2010 as an example of how stereotypical views of geographic areas can be unfounded. On that occasion, Nenshi and both visible minority councillors received the bulk of their votes in white-dominant areas.

- Municipal governments present a unique set of barriers to inclusion. One of the main points of discussion throughout the workshop was how we can explain the low representation of immigrant communities on city councils that serve diverse populations. Participants suggested a variety of factors that would explain this:

- Presence (or not) of municipal political parties: Participants debated how helpful municipal political parties are for the representation of immigrant communities. Ontario municipalities do not have political parties; however, Vancouver and Montreal do. A number of participants argued that in Vancouver political parties compete to recruit visible minority candidates, particularly those from larger immigrant communities. Some participants suggested that, judging by the Vancouver experience, municipalities in the GTA would benefit considerably from having municipal parties. However, in the Montreal metropolitan area, political parties do not appear to be doing much to foster visible minority representation, given that fewer than 4 percent of municipal councillors are from visible minority communities.

- Electoral institutions. There was some debate about ward systems versus at-large systems for electing councillors. Under a ward system, the municipality is divided into geographically limited districts, much like provincial and federal ridings. One of this system’s main benefits is that, if an immigrant or visible minority community is concentrated in a particular ward, it may have a considerable impact on who is elected. Under an at-large system, councillors are elected from the entire city. This tends to dilute the influence of immigrant communities: minority candidates have to win support from the entire city, rather than from particular areas.

- Paths to becoming a candidate: Chima Nkemdirim suggested that a key factor in explaining the under-representation of visible minorities on the Calgary City Council was the typical path to candidacy. Currently, prospective candidates often get involved with one of the city’s community associations. These organizations originally were meant to organize recreation. Over time, however, they became major -stakeholders in civic and urban planning decisions in a way that is unlike many other major Canadian cities. Positions on the associations are often used as a springboard to city council. However, the associations, in part due to membership fees, are highly unrepresentative of the communities’ ethnocultural makeup. As a result, though the associations are often consulted, they are not necessarily the best means to engage immigrant communities or recruit candidates for city council.

- Voting rights for permanent residents: Some participants suggested that granting permanent residents the right to vote in municipal elections could foster greater engagement at the local level and help develop a practice of participation for when they become citizens. This is the practice in a number of European countries. The Toronto City Council recently passed a resolution calling for this reform, although it would require the provincial legislature to pass legislation.

- Feelings of acceptance are key to immigrants’ attitudes toward elections and involvement. Antoine Bildoeau’s presentation drew on a survey of visible minority citizens in Quebec. The survey examined the sources of feelings of acceptance from Quebec and from Canada and the consequences for immigrants’ political integration. Many factors shape visible minorities’ feelings of being accepted by Quebec, including home language, time spent in Canada and experiences of discrimination; however, feeling accepted by Canada is only affected by experiences of discrimination. As feelings of acceptance go down, visible minority citizens tend to devalue engagement in politics and be less attached to the receiving society.

- New forms of outreach are necessary to foster electoral and civic involvement. Chima Nkemdirim spoke about the outreach strategies used by Mayor Nenshi. In the 2010 campaign, his materials were translated into 14 languages. In office, the motivation behind the approach Nenshi’s team has developed is that in order to reach many communities it is necessary to go directly to them — for example, approach them in shopping malls and on Calgary Transit. Another important way to foster civic and electoral involvement is to engage with youth. Holding mock elections and inviting classrooms to City Hall can help get school children become interested in participating.

The Perspectives of Civil Society Organizations

Representatives of four civil society organizations present at the workshop outlined their insights and approaches.

- Improving civics knowledge is necessary: Building on Chima Nkemdirim’s comments about the importance of mock elections and holding class meetings at City Hall, Alison Loat of Samara emphasized the importance of civics education for improving the inclusion of immigrant communities in public life. While improving civics education could improve the civic and electoral involvement of all Canadians, the impact children can have on their parents is particularly important in many immigrant families, given that many immigrant parents were not themselves socialized into political life in Canada as children.

- Improving citizenship education is key to enhancing involvement: Eyob Naizghi noted that his organization, MOSAIC, which serves immigrant communities in British Columbia, has developed an extensive citizenship education program for new Canadians. Although citizenship education tends to focus on familiarizing immigrants with the material in the citizenship guide, MOSAIC goes much further by teaching newcomers about Canada’s political system, providing practical knowledge about how to interact with government agencies and creating opportunities to debate public issues. In this context, Alejandra Bravo of the Maytree Foundation suggested that incorporating civics education into language classes for immigrants could be fruitful.

- Training potential candidates can boost minority representation: Alejandra Bravo discussed Maytree’s School for Civics program, which has trained hundreds of potential community leaders, including candidates, campaign managers and advisers in the 2010 Ontario municipal elections. The program helps leaders from under-represented groups (who make up 30 percent of the participants) plan long-term campaign strategies, obtain practical knowledge about campaigning, build networks and understand how to interact with the media. The Calgary School Board has a similar program for potential school board candidates.

- Building ties with and between ethnocultural communities is necessary: Anne-Marie Pham outlined her experiences creating programs for Vietnamese youth in Calgary (through the Calgary Vietnamese Youth Association) and nationally (through the Vietnamese Canadian Federation). These experiences led her to -several -conclusions about how visible minority civic organizations can improve the quality of community relations: fostering friendship and a sense of belonging, focusing on contributions of community, mentoring and inspiring the community’s youth and promoting leadership within the community. She added that is also important to build bridges between communities. She proposed the idea of “community hubs” – venues for bringing different communities together to educate people about politics while also focusing on issues among and between different communities.

- Basic support services are necessary to help foster civic involvement: Stéphanie Casimir from la Maison d’Haïti in Montreal spoke about barriers to electoral and civic involvement, including low incomes, a lack of child care and feeling uncomfortable travelling outside familiar areas of the city. She underlined that promoting involvement requires addressing basic life concerns, not just new outreach strategies. For this reason, la Maison d’Haïti provides public transit tickets and child care services, recognizing that the communities it serves may otherwise be unable to participate in civic activities.

Looking Forward

Participants shared the view that there is still a considerable amount of work to do for immigrant communities to be fully included in civic and political life. Ratna Omidvar, president of the Maytree Foundation, emphasized that government and nongovernmental organizations need to work to that end and that, although the situation seems to have improved somewhat, we need to do more to make improvements now. Governments and nongovernmental organizations can take concrete steps to increase immigrant communities’ civic and electoral involvement by recognizing the barriers that exist and attempting to correct them. They can also adopt best practices for outreach, particularly the following:

- Target outreach efforts and public events to places where immigrant communities get together, rather than places that are traditional.

- Demonstrate that public officials are accessible and are there to serve immigrant communities.

- Provide counselling to potential candidates for public office from immigrant and visible minority backgrounds.

- Translate materials into a variety of languages to make them accessible to wider communities, where possible.

- Integrate civics education into language and citizenship classes.

In addition to spreading knowledge about useful techniques for outreach, the workshop raised several questions that merit further exploration. In this regard, participants suggested a number of areas for future research and discussion.

- How much is visible minority representation about the demand for diverse candidates and how much is it about who is willing to be a candidate? Knowing the balance between the demand for and supply of candidates is crucial for understanding where our efforts should lie. This issue is particularly pressing at the municipal level, given that, according to some participants, potential candidates from immigrant communities seem to be less interested in running for municipal office than in federal and provincial elections.

- Backroom politics. Although there have been studies of candidates and elected representatives from immigrant communities, there has been less research into what goes on in private environments, such as candidate recruitment, decisions made by riding associations and discussions within political parties and their caucuses. The low number of candidates and representatives from visible minority and immigrant communities suggests there are barriers in moving from private citizenship to public candidacy. There was a strong consensus on the need for research in this area.

- Factors that motivate members of immigrant communities to become involved. One participant raised the issue of what motivates new Canadians to vote; however, this question also applies more broadly to civic and electoral involvement. Several participants suggested that role models were particularly important in fostering involvement.

- Outreach programs and civics and citizenship education. Although nongovernmental organizations have been developing good practices to improve the civic involvement of immigrant communities, it would be extremely helpful to know which aspects of these programs are most effective in encouraging immigrant communities to engage in public life.

- Fostering greater feelings of acceptance. Antoine Bilodeau’s research sparked considerable interest in the concept of acceptance and its potential impacts. Are there best practices for how community organizations and governments can promote feelings of acceptance?

- The impact of institutions on immigrant communities’ electoral representation. Participants raised several institutional factors that can affect immigrant communities’ electoral representation, including municipal political parties, high rates of incumbency, campaign finance regulations and the electoral system. More research is needed into which institutional reforms would be most helpful

- How diversity in elected institutions affects the representation of immigrant communities. One participant raised a central question: “How would politics be different if more elected officials came from visible minority communities?” Several participants built on this idea by suggesting that researchers examine how those elected from immigrant communities represent those communities – whether they represent their opinions better, pay more attention to them and talk more about the issues facing them.

- How civic involvement affects electoral involvement. One issue raised was the possibility that electoral involvement may not actually be the area that needs improvement first. Civic involvement is also incredibly important, both as a goal in its own right and as a means to improve electoral and other forms of engagement.

Although participants provided a number of suggestions for further research, we already know that immigrant communities are often outsiders in political and civic life in Canada. Given this reality, we need better outreach so these communities are fully included in public life. Increasing civic and political involvement is, after all, a crucial part of immigrant integration. These efforts will become more important as Canada becomes an even more diverse country through continuing immigration.