The incorporation of immigrants into Canadian economic life is a complex process with longterm consequences for immigrant workers, their families and Canadian society as a whole. This study calls for a reframing of the study of immigrant economic incorporation to pay closer attention to the relationship between migration status, legal status trajectories and employment outcomes, measured by job quality and not just by employment rates and earnings.

Luin Goldring and Patricia Landolt’s conceptual framework redefines the migrant labour force to include permanent and temporary workers. It also recognizes that there are various legal status pathways that lead to migrants’ long-term settlement in Canada. The authors use their original Index of Precarious Work to measure economic incorporation in terms of job quality, and they consider migrants’ legal status as an explanatory factor. Tracking job quality and changes in legal status over time allows for an analysis of the effects of policy and labour market dynamics on newcomers.

The concepts of precarious work and precarious legal status are central to this study. Precarious legal status is the situation of all nonpermanent residents, authorized and unauthorized. Using original data from a sample of 300 Latin American and Caribbean immigrant workers in the Greater Toronto Area, including information on job quality and legal status over time, the authors present findings from quantitative and qualitative analyses. Based on their quantitative analysis, the authors find that initial job quality and legal status upon entry are significant predictors of current job quality. Transitioning from precarious to secure forms of legal status did not protect respondents from remaining in jobs that were significantly more precarious than those of people who entered with the relatively secure status of permanent residence.

The qualitative research shows how early precarious legal status can contribute to migrants settling for precarious work and getting stuck in low-paying jobs for a long time, even after a change to secure legal status. The authors’ research identifies two broad factors that help explain the long-term effects of precarious status: employer practices that exploit workers’ precarious status to erode, violate or evade employment standards; and employees’ need to spend time and resources on efforts to adjust their status, which sometimes results in their losing money.

The authors conclude by identifying ways of mitigating the effects of precarious status on immigrant economic outcomes and social inequality, including replacing probationary forms of temporary migration with permanent residence, faster transitions to secure legal status and permanent residence, open work permits for temporary migrant workers, improvements in labour market and workplace equity, and broader access to settlement services. They also call for informed public dialogue on the current transformation of the national immigration system, including the increased role of employers in the selection of immigrants.

Analysts have noted the deterioration of immigrants’ economic outcomes in Canada despite an immigrant selection policy that admits “the best and the brightest.” This paradox is illustrated by data that show immigrants earning less than similarly educated Canadian-born workers and by stories of underemployed doctors, engineers and other professionals. Credential recognition, occupation-specific language and adequate Canadian experience have been identified as examples of the barriers facing high-skilled immigrants in particular, while discrimination, difficulty assessing education and credentials, and language skills are identified as factors affecting immigrants more generally. Given that Canadian immigration policy is undergoing changes with far-reaching and unclear long-term effects, we need to consider more carefully the assumptions, models and data that guide the analysis of immigrants’ employment outcomes. Close attention must be paid to the relationship between migratory status and status trajectories on one hand, and employment outcomes on the other. This study uses our Index of Precarious Work (IPW), a composite indicator of labour insecurity or job quality, to measure employment outcomes.

In the first section of this study, we review immigration models, discussing the links and gaps between immigration policy, implementation, government surveys and administrative data,1 and trends by entry categories. This section frames our interest in understanding the incorporation of all newcomers, whether they are official or de facto immigrants. The second section reviews scholarship on immigrant economic outcomes; it includes work that specifically deals with the labour market incorporation2 of newcomers and literature on transformations that contribute to general labour market insecurity for all workers. The review situates immigrant-specific precariousness in the wider context of labour market transformation. While many workers do increasingly precarious work, a growing number of newcomers spend time navigating various forms of temporary and probationary legal status before they can apply for permanent residence. Others may remain in a temporary category, stay in Canada without work or residence authorization or leave the country. We explore how their precarious legal status impacts their labour market outcomes, as defined by job quality. We suggest ways of investigating current immigrant trajectories and patterns of labour market incorporation that adequately capture contemporary policies and on-the-ground trends.

In the third section, we present our own framework for analysis of the links between precarious employment and precarious legal status trajectories, addressing the challenges and research gaps identified in the first two sections. Specifically, we measure job quality and insecurity using our composite Index of Precarious Work and explain how we capture legal status trajectories over time. This methodology allows us to investigate how newcomers arriving under a variety of entry categories fare over time in the contemporary labour market in the Greater Toronto Area.

In the fourth section, we identify the key determinants of immigrant work outcomes as measured by the IPW, in order to understand the linkages between precarious work and legal status trajectories. We begin with a quantitative analysis of the determinants of precarious work using original data collected in 2005-06 from a sample of Latin American and Caribbean workers.3 A key finding is that early job quality and having precarious legal status at any point are significant determinants of economic incorporation. This analysis is followed by a discussion of qualitative results from the study. Our empirical research offers insights into the employment experiences of people who enter Canada under various categories and experience a range of legal status trajectories. Focusing on those who move from authorized and unauthorized precarious status to the security of permanent residence, the qualitative results illustrate how employers’ “gloves-off strategies”4 are among the factors contributing to long-term employment precarity, even among those who shift to secure status.

In the final section, we discuss our findings in relation to recent changes in immigration and settlement policy and identify issues for public discussion. Our concern is that immigration and settlement policy, combined with shifts in the economy and labour markets, is turning migratory status into a significant and lasting dimension of social inequality in Canada.

Canadian immigration policy is strongly connected to economic priorities, particularly the needs of employers and labour market pressures (Bauder 2006). International relations and events on the world stage also shape national immigration policy.5 Over time, immigrant selection criteria and settlement policies have changed — expanding, for example, to include humanitarian considerations through refugee policy and to address short-term labour market priorities through temporary worker programs. Labour market outcomes remain a key indicator of incorporation as well as an important topic of discussion. Precisely how these economic outcomes are defined, however, is not an exact science. Instead, it is tied to how researchers ask questions about immigration, which in turn is linked to immigration policies, government survey and administrative data, the politics of policy implementation and actual trends in migration and incorporation.

In turn, immigration policies are linked to the way governments collect, organize and present survey and administrative data on immigration; to regulations meant to put policies into practice; to the implementation of policies through programs, budget allocations, personnel decisions and the like; and to actual patterns of newcomer entry and incorporation. We use the term “immigration models” to encompass these aspects of immigration. Each of these elements of migration, taken on its own, does not tell a complete story: immigration policies may or may not be fully or evenly implemented across or within jurisdictions, and policies may not always be in step with government surveys and administrative data, implementation or actual trends.6 However, policies and data strongly influence the way researchers ask questions about immigration and newcomer integration. It is our contention that prevailing immigration models have been slow to capture emergent trends that can be detected but not fully analyzed with existing data. We argue that, to study and explain current patterns of immigrant economic incorporation and their relationship to legal status, research questions need to be posed differently and new types of data collected.

Here we first describe three immigration models that, since the mid-1960s, have organized immigration research and debate and discuss how they, together with government surveys and administrative data, shape the way analysts define and study immigrant incorporation and outcomes. We then present a fourth model, which we argue offers a more accurate picture of what is currently taking place. Our discussion notes links between policy and government data. It focuses on the entry tracks associated with each model and considers whether and how these are associated with long-term settlement versus short-term labour market priorities, the permeability of track boundaries and the possibilities and kinds of movement between tracks. Our discussion of policy models seeks to examine the tension generated by the gaps between policy, government surveys and administrative data, common sense understandings of migration patterns and realities experienced by many migrants with precarious status.

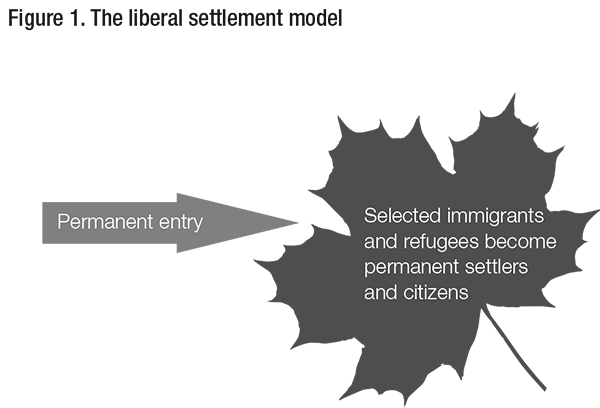

We describe our first model as the liberal settlement model (figure 1). It took shape under the Liberal governments of the mid-1960s and 1970s. We refer to it as liberal partly because of the governing party’s name and platform but also because it was based on the removal of explicitly racist criteria and the implementation of seemingly “universal” selection criteria based on human capital (through the points system), while also leaving room for family members and humanitarian admissions. It is a settlement model because of the focus on permanent immigration and settlement. This model presented one entry track for people migrating to Canada: for permanent residents who would subsequently become citizens. This track’s boundaries were not in question; everyone was on the same conveyor belt to settlement and eventual citizenship. Although temporary residents (including workers and others) were in fact entering and present in Canada, and had been since the mid-1960s, they were absent from the policy model and from immigration statistics.

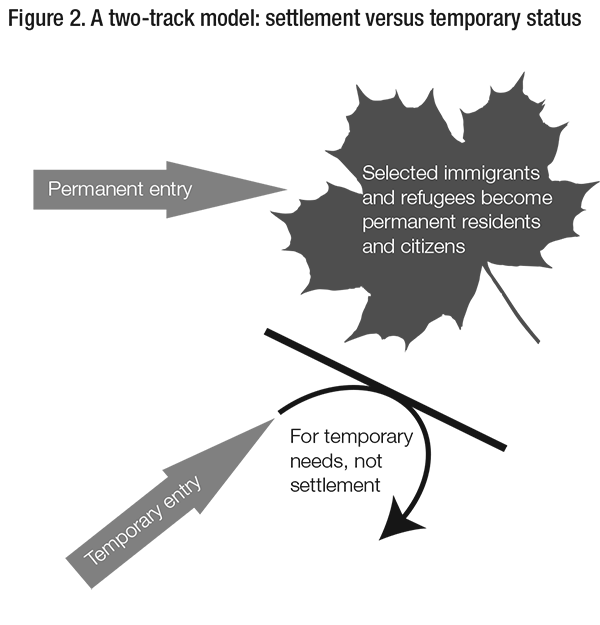

Signs of a second model appeared with the identification of nonimmigrant entrants, but the paradigm became clear only in 1980, when temporary entrants were included explicitly and separately in official statistics. Temporary entrants were classified in terms of their relationship to settlement and employment, with information on geographic location and length of stay.7 The early two-track model (figure 2) can be understood as a framework for making sense of immigration trends — and associated labour market policy — based on recognizing two groups and tracks: immigrants (understood as workers and long-term settlers) and temporary residents (entering for various reasons but remaining for defined and short-term periods). The two entry tracks are distinct and clearly bounded. They lead workers along separate paths, into distinct labour market segments, and sort them into future citizens and noncitizens. Temporary residents are only temporary: their path leads them to leave Canada and go “back home,” perhaps to return but again on a temporary basis. The only route written into policy that offered a shift from temporary to permanent status operated on a small scale, starting in 1982, for workers in the Live-in Caregiver Program (LCP) (Valiani 2009).8

The liberal and two-track models have had a lasting impact on public debate, research and government surveys, and administrative data on migration. The most notable legacy is the handling of immigration status as an immigrant versus nonimmigrant binary rather than a multiple-category variable in studies of immigrant incorporation. The binary classifications typically compare foreign-born immigrants with native-born, or contrast immigrants (by official definition, permanent) and nonimmigrants (defined as temporary residents). These binaries may or may not correspond to people’s practices: permanent immigrants may spend time abroad, and some temporary residents may return again and again, raising questions about the permanence of the former and the temporariness of the latter.9 The binaries ignore the possibility of de facto settlement. Moreover, they homogenize extremely diverse populations (Pendakur and Pendakur 1996; Shields et al. 2011) and have the effect of freezing migratory status, precluding the possibility of studying the effects of changes in legal status over time.

In sum, the first two immigration policy models do not allow for questions about legal status trajectories or the social and economic incorporation of nonimmigrant entrant10 (such as temporary workers, students and refugee claimants), who are by definition understood as outside the category of immigrants. The possibility that some immigrants may have entered and spent time in one or more forms of temporary status is not acknowledged, and there is no analysis of the relationship between specific entry status (temporary versus permanent, and subcategories therein) and labour market outcomes.

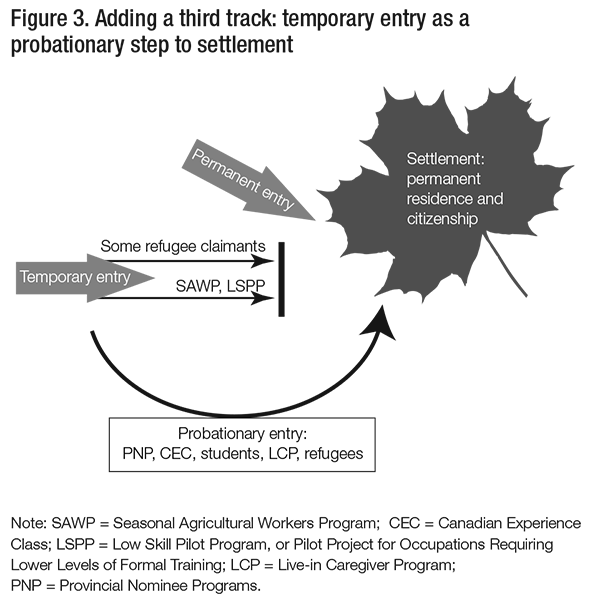

Since the late 1990s, a third immigration model has emerged. This model (figure 3) identifies explicit pathways from temporary entry to permanent residence for selected temporary workers. The model effectively creates bridges between temporary and permanent status, formalizing existing trends (such as the route to citizenship offered through the LCP), but selectively. Researchers have characterized this policy provision as “two-step migration” (Hennebry 2012; Nakache and Kinoshita 2010; Valiani 2009). This type of migration currently takes place through two programs. The Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) allows territorial and provincial governments and employers to nominate selected temporary residents for permanent residence. Individuals in various skill designations (including “low skill”) as well as their spouses and dependants are eligible. The Canadian Experience Class (CEC), introduced in 2008, allows temporary workers in high-skilled occupations and international graduates with Canadian work experience to apply for permanent residence.11 As a share of the total number of permanent residents entering Canada in 2011, principal applicants plus spouses and dependants represented 15.4 percent for the PNP, 2.4 percent for the CEC and 4.5 percent for the LCP (CIC 2012a). The PNP program, in particular, is becoming an increasingly used pathway to permanent residence for temporary entrants. Moreover, with 22.3 percent of permanent residents classified under one of these three categories, twostep migration has become an important element of immigration to Canada.

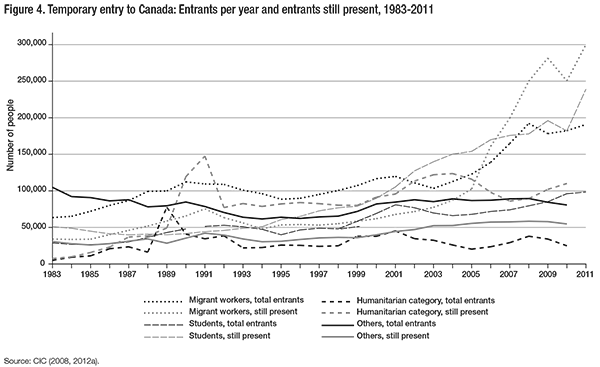

The term “two-step migration” draws attention to the existence of a bridge or path to citizenship for (some) temporary entrants but sidesteps the continuing increase in temporary entrants. The number of temporary entrants, particularly migrant workers and international students, has increased dramatically. The number of economic class permanent entrants has also climbed, but the number admitted through the family class has declined since the early 1990s. Figure 4 reports the number of temporary entrants and the number of those still present, by category of temporary entry, for each year between 1983 and 2011. It shows that in 2006 the number of temporary workers still present surpassed the number of temporary workers entering Canada. The persistent and growing presence of people counted in these temporary entry categories points to a rising and substantial population of people with authorized but precarious status, an unknown number of whom are de facto settlers.

Two points of tension emerge in the normative framing of immigration as a two-step model. First, “two-step” suggests a unidirectional and orderly progression from temporary to permanent residence that focuses on the end point rather than the process. But is temporary residence part of an orderly progression for all who are eligible to make this transition, or is the “step” better understood as an opportunity to assess a candidate’s suitability for permanent status? If the latter, “probationary status” would be a more accurate term. The ways government surveys and administrative data are organized do not allow for a comprehensive analysis of the transition from temporary to permanent status via the two-step track. Available government data provide information on permanent residents by subcategory, which tells us how many people initially entered under these temporary categories. But information is not publicly available on how long they spend in a temporary category, on whether they moved between several temporary categories before the shift to permanent status or on the sociodemographic profile of those who were eligible and did or did not move to permanent resident status (Goldring 2010).

In addition, this three-track, two-step model ignores the possibility that people move between entry tracks in various directions, shifting between different authorized temporary categories, from authorized to unauthorized situations and perhaps back to authorized status or even falling out of status more permanently. That is, the tracks may not be as bounded as many assume.

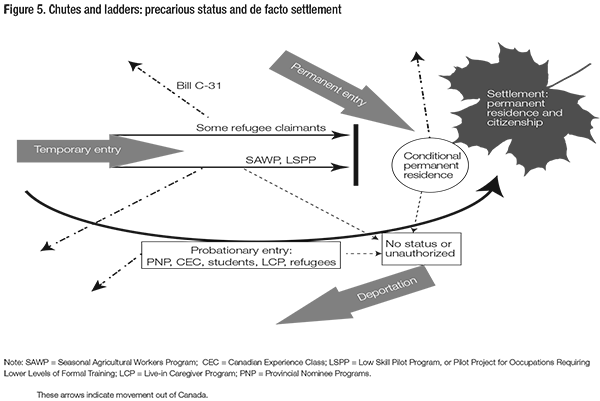

In light of the gaps discussed above, we propose an alternative model. The “chutes and ladders” model illustrated in figure 5 has several advantages over the three-track immigration model. First, it reframes the orderliness and unidirectionality of the latter model by recognizing multidirectional movement between tracks. This takes into account the very real possibility that newcomers entering under various authorized but temporary categories are likely, over time, to experience shifts in status, leading them to occupy one or more categories. While some will achieve permanent residence, others may move between temporary authorized categories or between these and unauthorized status, and thus continue to live with precarious status. This is consistent with the lived experiences of an unknown but not insignificant number of migrants.12

Second, the chutes and ladders model invites attention to the role of policies and institutional actors in precipitating movement along or across tracks. Policy changes may redraw the boundaries of immigration categories and change the rights associated with categories. Front-line workers, teachers, landlords, doctors, legal consultants, employers and other institutional actors may act as catalysts, moving people from one legal status category to another, and toward more or less secure status.

Third, this model underscores the importance of a systemic perspective, one that pays attention to the whole “board game” or model. Instead of focusing on a specific immigration category or track, this means considering a wide set of policies and programs and their relationship to one another, available government surveys and administrative data, gaps in data and actual patterns of immigration and settlement, including those of de facto immigrants.

Although a comprehensive analysis of recent immigration policy changes is beyond the scope of this study, some trends are worth noting. One is the expansion and fragmentation of probationary categories. There are plans to use probationary forms of status for people who came to Canada on a direct track to permanent residence, rather than reserving them for temporary entrants such as refugee claimants and those becoming permanent residents through the CEC and the PNP. For example, proposed policy changes have introduced “conditional permanent residence” for sponsored spouses (CIC 2011a; Canadian Council for Refugees 2011). While this proposal is intended to prevent marriage fraud, implementing it would extend probationary status and status precarity into the realm of permanent residence. A second trend is restriction of entry under humanitarian categories. The idea that people from around the world have a legitimate claim to refuge is being eroded (Macklin 2011).13 Recently announced changes to the Federal Skilled Worker Program will prioritize stronger language skills, Canadian experience and a narrower and younger age range (CIC 2012b). There are also plans to increase the entry of workers in the skilled trades. Some of these measures may contribute to improving outcomes for immigrants who are not required to first spend time in a probationary temporary status. However, more restrictive policies tend to push people to find ways of entering and remaining in the country through any possible avenue. That would continue to produce churning through forms of authorized and unauthorized precarious legal status, with the effect that the population of vulnerable workers will remain significant.

Our main interest is to understand the determinants of precarious work among newcomers, regardless of their status upon entry or their postentry trajectory. The chutes and ladders model offers a framework that allows us to pose such questions about migrants’ legal status trajectories. We especially want to examine employment outcomes with variables and analytical concepts that can begin to capture the complexity of how immigration policies play out on the ground and the experiences of what we call de facto settlers, rather than limiting the discussion to permanent residents or officially recognized immigrants. In the absence of adequate data on employment quality, migration and legal status trajectories as well as basic social and demographic information, we undertook original data collection. Before describing our study, we review two sets of scholarship that help us understand the character of immigrant economic incorporation in the new economy labour market with attention to labour insecurity and precarious work. In line with our previous discussion of immigration models, the overview of scholarship highlights the relationship between how issues are defined and how data are collected; it also identifies gaps between existing data sources and emergent realities and practices on the ground.

Labour market incorporation of immigrants is important for social inclusion because it determines employment income and shapes material well-being. Work relations are among the most influential relationships in people’s everyday lives, with consequences beyond the workplace (Kalleberg 2009). Finding and keeping decent work that pays a living wage is an essential component in the healthy and productive incorporation of immigrants. Falling into unstable and poorly paid jobs has immediate negative impacts on immigrant families and their children as well as long-term negative consequences for Canadian society as a whole. Precarious employment, in particular, is associated with a battery of negative health outcomes for individual workers, families and communities (PortheÌ et al. 2010; Scott-Marshall and Tompa 2011; Tompa et al. 2007; Vives et al. 2010; Wilson et al. 2011).

Global economic reorganization has affected immigrants’ labour market incorporation trajectories and outcomes at the national level. Unlike the immigrants who entered Canada during the industrial boom after the Second World War, today’s immigrants, although more educated, encounter declining employment and income rates and increasing unemployment and poverty rates, compared with Canadian workers (Picot and Hou 2003; Picot and Sweetman 2012). Although there is broad agreement that many immigrants are not “making it” in Canada, there is still considerable debate about the causes and characteristics of immigrants’ declining fortunes. There is also debate about how labour markets and work have been reorganized as a result of globalization and whether the resulting changes are positive or negative.

Three perspectives distinguish literature on immigrants’ labour market outcomes: human-capital-driven explanations, labour market stratification and institutional approaches linked to labour market segmentation theory.

A focus on human capital is favoured by economists who examine immigrant incorporation from the perspective of microand macro-level supply-demand transactions and exchanges. Research is commonly based on Statistics Canada surveys and other administrative data. Analysts track and compare wage, employment, poverty and unemployment rates over time for immigrant and Canadian-born workers, focusing on demographic and human capital factors as key determinants. In terms of policy dialogue, recent research on declining immigrant fortunes has led economists to evaluate the alignment between labour market demand and immigrant selection policy (Alexander, Burleton, and Fong 2012). Debate centres on how to define and plan for labour market shortages: by responding to short-term or long-term demand, to industryand employer-specific needs versus immigration policy frameworks, or to regionalor national-level shortages.

Picot and Sweetman (2012) provide a comprehensive review of this approach. They identify important factors causing mismatches in the labour market that, economists argue, explain why immigrants arriving since the late 1970s have fared poorly in spite of their education and premigration work experience. Among these factors are the shifts in immigrant source countries (associated with difficulties with language, racial discrimination and cultural differences) and the declining relevance and economic rate of return of premigration education and labour market experience (7). Picot and Sweetman also consider the integration of the second and third generations,14 reporting that visible-minority second-generation workers earn less, on average, than White third-plus-generation members, even when accounting for differences in education. Despite their acknowledgement of the likelihood that racial discrimination exists in the labour market and their recognition that economic mobility will not always improve over time, they nonetheless conclude that economic incorporation is a multigenerational process in which earnings gaps, even for visible minorities, decrease over time; and they report that, overall, the children of immigrants have strong labour market outcomes (16).

A second perspective, inspired by John Porter’s (1965) vertical mosaic framework, focuses on stratification. Like economists, stratification scholars use Statistics Canada data to track earnings and employment and poverty rates, with initial work focusing on differences between “ethno-racial” groups (Lautard and Guppy 1990). They also look at occupational and sectoral clustering and distributions to explore whether workers are tracked into different occupational settings based on social location.15 Race, gender and birthplace are considered key stratification determinants, resulting in differential life chances and outcomes (Boyd 1984; Hou and Balakrishnan 1996; Ornstein 2006; Pendakur and Pendakur 1996).16 For stratification scholars, employment equity in hiring procedures and pay scales is a priority as a way to adjust for employer practices and to enable workers to find jobs commensurate with their skills and education.

Contemporary stratification research finds that immigrants, particularly those from racialized groups, have lower incomes than similarly educated nonimmigrants, and that lasting income disparities are emerging among native-born ethnic and racialized groups (Hou and Balakrishnan 1996; Li 2000; Galabuzi 2006; Teelucksingh and Galabuzi 2005). Pendakur and Woodcock (2010) investigated earnings disparities across Canadian-born ethnic groups, finding that earnings gaps between visible minorities and White workers have not narrowed since the 1990s in spite of the growth of the visible-minority population. The poor earnings of South Asians and Blacks are still evident in the 2000s. These findings challenge the notion that time in Canada or immigration status is the root cause of differential labour market outcomes, rather than discrimination and related processes (Pendakur and Pendakur 2002, 2011).

A third perspective starts from the premise that labour markets are segmented, with the primary segment characterized by higher status and better-paid jobs and the secondary segment by jobs that are poorly remunerated, offer no possibilities for upward mobility or improvements in job quality and rely extensively on and exploit vulnerable labour (Gordon, Edwards, and Reich 1982). Segmentation research in Canada offers a variety of approaches and variable findings, making it difficult to generalize or compare across cases (cf. Hiebert 1999). Among the influential factors that segmentation scholars see as affecting immigrant earnings, employment rates and socio-economic incorporation are employment setting, sector of employment (public or private), firm size and basis of pay (Fang and Heywood 2006; Hou and Coulombe 2010); professional accreditation practices (Boyd and Schellenberg 2007; Boyd and Thomas 2002); neighbourhood (Wilson et al. 2011) and city-level variation and effects (Hiebert 1999); and gender, ethnicity and racialization.

Policy prescriptions linked to the segmentation perspective tend to be rather diffuse and conjectural. Certainly stratification scholars’ support for equity policies, antiracism initiatives and easier credential recognition resonates with the segmentation approach. The focus of segmentation scholars is, however, on how institutions and various stakeholders produce and reproduce inequalities. There is also a perennial call for data that better reflect changes in work organization on the ground (Hiebert 1999).

In spite of their variations in the characterization of the labour market, the above three perspectives converge in their findings and to some extent on how to account for current trends. A key difference concerns the role of time, a factor closely related to how each perspective understands the structure and logic of the labour market. Human capital theorists find that over time some immigrants (particularly earlier cohorts) experienced labour market improvements, such that the children of immigrants can expect some upward mobility. Stratification theorists expect minimal, if any, improvement in immigrants’ incorporation over time: racialized glass ceilings, glass doors and sticky floors within and across firms make upward mobility highly unlikely, particularly for non-White immigrants and, some argue, their Canadian-born children. Segmentation scholars do not examine the role of time in immigrant labour market incorporation.

There are conceptual problems and significant research gaps across the three perspectives. First, the bulk of research focuses on immigrants assumed to be on a track toward citizenship and permanent settlement. Thus, migrants’ legal status is defined in binary terms: foreign-born versus Canadian-born, and immigrants versus nonimmigrants. We have used the concept of precarious legal status to develop an alternative to such binary ways of thinking. Precarious status means forms of legal status characterized by any of the following: lack of permanent residence or permanent work authorization, limited or no social benefits, inability to sponsor relatives and deportability. In Canada, precarious status describes people with authorized temporary status (such as temporary workers, international students and refugee claimants) and people without authorization to work or reside in the country (including those with expired permits or denied refugee claims, those under deportation orders and people who entered without authorization) (Goldring, Berinstein, and Bernhard 2009). In addition to capturing the precarity associated with several state-defined legal status categories, precarious status also includes the possibility (unrecognized in most literature) that over time, individuals may (and often do) move between such categories. It also recognizes that precarity may be produced and reproduced through social policy and institutions (Goldring and Landolt, eds., forthcoming).

A second research gap is the absence of studies that examine temporary and permanent migrant workers together or identify workers who shift from a temporary entry category to permanent residence. Research on the labour market experiences of temporary migrant workers often focuses on specific programs, such as the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP)17 and the Live-in Caregiver Program (LCP) (Arat-Koc 1997; Bakan and Stasiulis 1997a; Valiani 2009). Since 1982, workers in the LCP have been able to apply for permanent residence after completing a set number of work hours. However, research on the post-LCP outcomes of this group of workers is limited. Research on the labour market outcomes of refugees and asylum seekers is also limited, but findings point to high rates of poverty and low employment rates (Abbott and Beach 2011; Devoretz, Pivnenko, and Beiser 2004). Our work seeks to address these limitations. We show the importance of expanding research on immigrant labour market incorporation so that temporary and permanent migrants are considered together, a wider range of temporary categories are acknowledged and the range of ways individuals may transition from temporary to permanent status is better understood.

A third research gap is that analysts focus on earnings and wage rates with limited consideration of the terms of employment or labour insecurity that might characterize immigrants’ work experience.18 Scholars note differences based on firm size, sectoral distributions, the level of wages paid by firms and occupational rankings but do not adequately consider the quality of work. In our view, establishing that immigrants consistently fall into the most precarious jobs seems insufficient and tells us little about how beginning in a precarious job shapes the jobs an immigrant will have over time. To address this gap, our research measures the quality of work using a multidimensional index of precarious work. We track this measure over time and analyze its determinants.

To advance our understanding of immigrant labour market incorporation, we look at a second body of literature dealing with the reorganization of work and attendant labour insecurity in the new economy. We focus on three main approaches. These highlight precarious work; workplaces and employer strategies; and changes in the regulatory landscape.

The first approach tracks the presence of precarious work in the labour market. Precarious work is characterized as a multidimensional social process, thus allowing us to go beyond the dichotomy between standard employment (full-time permanent employment) and anything else (nonstandard or contingent work), to study multiple dimensions of insecurity (such as degree of certainty of continuing employment, union protection and performing formal versus informal work). In Canada a groundbreaking initiative led by Leah Vosko used Statistics Canada surveys to document the existence and growth of precarious employment in the Canadian labour market.19 This research found a pronounced increase in forms of employment (such as part-time work, self-employment and temporary agency assignments) characterized by precarity in the 1990s and a plateau in the trend in the 2000s (Noack and Vosko 2012).

Other research finds that precarious work is stratified such that women, immigrants (recent immigrants in particular), visible minorities, people with high school education or less and single parents are consistently more likely to fall into low-wage and insecure work arrangements or precarious work (Creese 2007; Noack and Vosko 2012, 27). Drawing on Rodgers (1989), Cranford, Vosko, and Zukewich (2003) create a typology of mutually exclusive employment forms that differ in relation to three dimensions of precarious work: regulatory protection as measured by firm size; union status as an indicator of control over the labour process or organization of work; and hourly wage as an indicator of income. More recent research adds extended medical coverage and pensions as indicators of a “social wage,” a fourth measure (Noack and Vosko 2012).20 These scholars are interested in what combinations of indicators are more likely to occur together and in the correspondence between points of greater overlap between the indicators and employment forms. However, the levels of aggregation at which Statistics Canada data are organized have made it difficult to move from the calculation of indicator overlaps to the calculation we have sought: namely, a composite measure or index.

A second approach studies workplaces and employer strategies and shows, in particular, how employer strategies informalize the organization of work, thus pushing workplace labour practices outside the bounds of state regulations (Bernhardt et al. 2008; Neu 2012; Portes, Benton, and Castells 1989). Bernhardt et al. (2008) map the different ways that employers in North America are responding to global competition and identify four types of employers’ gloves-off strategies: employers evade labour standards by creating legal distance from employees through subcontracting, temporary agency hiring and the misclassification of workers as self-employed; they erode normative standards by manipulating work hours so that employees don’t qualify for benefits (for instance, by part-timing the workforce, shifting to piece rates or commissions, or bringing in project-based pay systems); they abandon normative standards when they institute wage freezes and create two-tiered pay systems; and they violate labour law, paying workers off the books and not contributing to state entitlements such as employment insurance and the national pension plan (cf. Neu 2012).

Gloves-off strategies are difficult to study. Erosion and evasion strategies are neither monitored by regulatory agencies nor documented in existing industry data (Bernhardt et al. 2008). Violation strategies, such as paying workers off the books (cash payment), are hard to detect. In the absence of surveys that raise questions about deregulation and informalization practices, it remains difficult to analyze these trends (cf. Akter, Topkara-Sarsu, and Dyson 2012).

Research in the United States has amply demonstrated the link between gloves-off strategies and precarious status. Workers’ precarious legal status is exploited by employers to organize shop floors as well as informal day labour in ways that evade, violate and erode employment relations (Gammage 2008; Theodore et al. 2008). Canadian research has only begun to document the conditions faced by people with no authorized status (Magalhaes, Carrasco, and Gastaldo 2010), temporary workers in agriculture (Basok 2002; Hennebry 2009; McLaughlin 2009; Preibisch and Binford 2007) and other sectors (Byl 2009), and those with other forms of precarious status working in other sectors (Goldring and Landolt, forthcoming; Landolt and Goldring, forthcoming; McLaughlin and Hennebry, forthcoming; Workers’ Action Centre 2007). More research is required to understand how legal status intersects with the sectoral, occupational and regional contours of employers’ strategies for evading and violating employment standards.

A third approach in the literature of work organization and labour insecurity examines regulations that underpin the legal and normative framework of the employment relationship. The reorganization of work produces employment forms that fall outside the existing regulatory framework, which was designed in relation to the standard employment form of full-time permanent work for a single employer (Lowe, Schellenberg, and Davidman 1999).21 Governments at different levels rewrite regulations through legislative and fiscal reform (Vosko 2010), including changes to minimum wage legislation, to definitions of working time (such as full-time, part-time or casual) (Fudge and MacPhail 2009; Thomas 2009) and to monitoring of health and safety standards (Tombs and Whyte 2010; Sargeant and Tucker 2010). The research suggests that reforms to the regulatory environment tend to complement gloves-off strategies and promote flexible, nonstandard employment forms with less public oversight.

Of particular interest to our study is research on the relationship between labour market regulations and immigration policy.22 Analysts document how immigration admission policies create legal status entry categories that place restrictions on migrant workers’ participation in the labour market. Temporary visas for migrant workers and other temporary residents who are authorized to work (such as sponsored dependants and international students) shape workers’ relationships to employers (Anderson 2010; Vanderklippe 2012). In Canada programs such as the PNP and the CEC, which offer a pathway from temporary to permanent status, can also influence these relationships because the employer determines the workers’ transition in legal status (Abboud 2012). Immigration entry categories do more than admit newcomers; they establish workers’ legal rights in the labour market. The categories may also give rise to employer-employee arrangements outside the legal and normative employment relationship that regulates native-born and permanent immigrant workers (Anderson 2010; Faraday 2012; Fudge 2012; Fudge and MacPhail 2009; Sharma 2006).

The research on labour insecurity reviewed above offers rich insights. First, it makes a strong case for understanding work as more than simply employment rates and wages. The concept of precarious work, for example, captures the multidimensional character of labour insecurity, thus strengthening our call for the construction of a composite measure or index of job quality. Second, the study of workplace and employer strategies offers an institutional and relational analysis of how labour insecurity plays out on the shop floor. The notion of gloves-off strategies suggests how the tactics of individual employers can downgrade the legal and normative terms of the employment relationship for all workers in a place of employment, regardless of status. Finally, the analysis of the current regulatory environment suggests that immigration policy, specifically the creation of categories that restrict migrants’ rights in the labour market, allows employers to differentiate between citizen and noncitizen workers and also among noncitizens. Overall, not only does the research point to the importance of legal status for the study of immigrant incorporation into Canadian labour markets, it also points to the need for a conceptualization of legal status (or legal statuses) in a manner more congruent with current worker realities than the simple divisions of foreign versus Canadian-born and immigrant versus nonimmigrant.

Our goal was to analyze the intersections of precarious work and precarious legal status over time. To that end, we required a data set that would allow us to track the relationship between precarious work and precarious legal status over time. Such data were not available, so we designed and carried out an exploratory survey that gathered information not available in larger secondary data sets. Here we review important considerations and obstacles that we encountered and sought to address in the research design phase of the project. We also discuss how we measure precarious work and legal status trajectories based on data collected in our survey.

In our assessment, an index is the most flexible and robust instrument for analyzing the multidimensional character of labour insecurity as defined by the concept of precarious work. An index is commonly used to generate a composite measure of a multidimensional concept based on the grouping of information from multiple questions. Indeed, two other international research teams have developed an index to measure precarious employment (Tompa et al. 2007; Vives et al. 2010).

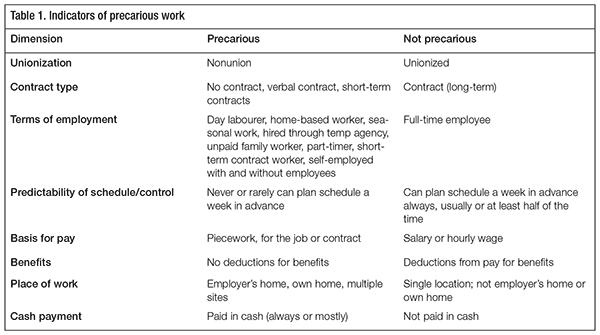

In order to arrive at a decision about which indicators should be included in an index of precarious work, we reviewed various authors’ concerns over obtaining a robust measure of precarious work and conceptualizing precarious work as a multidimensional and dynamic socio-economic experience.23 We found valid reasons for including income as a dimension of the concept of precarious work and an indicator in an index of precarious work.

However, we also found good reasons for not including income. If precarious work is, as the literature on labour insecurity suggests, a reflection of a complex variety of employer strategies and of a shift in the normative and regulatory environment, then it is likely to occur at different income levels (cf. Gilmore 2009). A worker can be precariously employed and very well paid. If income is not an index indicator, it is possible to test to what extent and which dimensions of precarious work are more prevalent with higher or lower earnings. Moreover, given the diversity of pay structures that characterize the labour market in the new economy, the basis on which workers are paid (cash payment, piecework, commissions, etc.) may be a more significant source of employment precarity than how much they are paid, because informalized pay arrangements make workers more vulnerable to underpayment and wage theft (Akter et al. 2012; Workers’ Action Centre 2011).

We also reviewed 20 surveys and administrative data sets to find a bundle of indicators that we could use to construct our index and test the relationship between precarious work and precarious legal status. We found that these failed to provide sufficient information on employment to capture the multiple dimensions of precarious work. All the data sets lacked indicators that could speak to the growing informalization of work (for example, cash payment). Other indicators, such as measures for nonpermanent work, were not mutually exclusive. We also found that data sets with more comprehensive information on work relations had scant information on legal status. There was no information on temporary forms of legal status (categories such as migrant worker or asylum applicant) or transitions in legal status (for example, from asylum seeker to permanent resident and citizen). Given the limitations of existing data sets, we chose to design a survey in order to produce our own data. Table 1 identifies eight indicators of precarious work as measured in our research and captured by our Index of Precarious Work (IPW).

Our survey sought information about precarious work at different points in time: work before migration, work in the respondent’s first year in Canada (early work) and current work, including up to three jobs, at the time of the survey (2005-06). For each job, the IPW adds up the indicators and provides a summary score from 0 (not precarious) to 1 (most precarious). To receive a score of 1, a person’s job would have to rank as precarious for all eight indicators. The composite score provided by the IPW enables us to describe more completely the extent to which a person’s job is precarious. It also allows us to make comparisons between groups, and over time for groups and individuals. For example, we can compare the IPW scores for groups categorized by gender, country or region of origin, period of entry, age, education and so on. We can compare early work IPW scores with current work IPW scores for different subgroups. It is also possible to examine the components of the IPW to illustrate which indicators are most prevalent among sample subgroups (cf. Goldring and Landolt 2009a, 2009b).

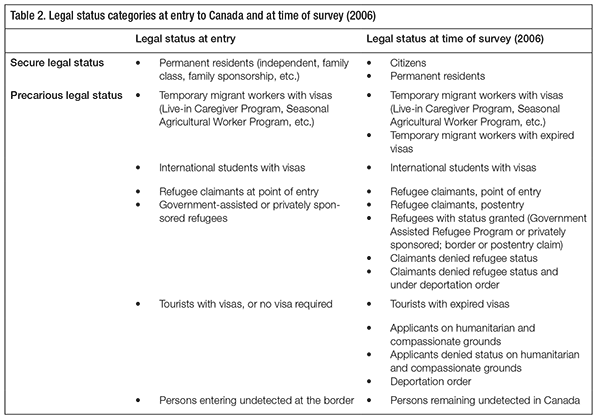

To test the relationship between precarious work and precarious legal status, the project survey asked respondents about their status at the time of arrival and at the time of the interview and the range of strategies (legal, formal or informal) they used to improve their legal status in Canada. Table 2 presents the range of legal status categories at the time of the survey. It includes formal entry categories (such as permanent residents, live-in caregivers, international students with visas, tourists with visas) and post-entry categories (such as applicants on humanitarian and compassionate grounds and claimants denied refugee status) as well as informal and potentially unrecognized entry and postentry categories (such as persons entering undetected at the border, applicants rejected on humanitarian and compassionate grounds and visa overstayers). Because we designed the index in 2005-06, it did not include legal status categories that did not exist or were not commonly used in Ontario at that time (such as the PNP and the CEC, as shown in the three-track, two-step immigration model in figure 3).

In 2005-06 we interviewed 300 Latin American and Caribbean immigrant workers using a mixed-method survey that included closedand open-ended questions on a variety of topics: reasons for migration and early settlement experiences; approaches migrants use to deal with employment challenges and opportunities in Canada; the extent to which these approaches are transnational in scope — that is, whether they require the maintenance of ties to people and institutions in the country of origin; and patterns of contact (or lack of contact) with social institutions and community organizations in the early settlement process. Respondents were also asked detailed questions about the jobs they held at four points in time and about their legal status and the changes in that status over time. In this section, we review the sample design and population characteristics and present the logistic regression model and the key findings. We then present some of the qualitative findings that help us make sense of the dynamic relationship between precarious employment and precarious legal status.

Constructing a representative sample was a challenge, as there was no clear sampling frame.24 In the end, we developed a multistep random sampling design to generate a study population of 300 respondents, composed of 150 Latin American and 150 Caribbean immigrant workers living in the Greater Toronto Area. We took steps to produce a sample that reflected the complexity of recent immigration trends and processes for the two groups. We established five criteria for choosing respondents: born in a Spanish-speaking Latin American or English-speaking Caribbean country; arrived in Canada after June 1990 and before June 2004; age at arrival between 14 and 45 years; currently employed, at least 20 hours per week and for the previous two months; and not a full-time university or college student. We did not establish requirements for legal status, occupation, sector or terms of employment. We did take steps to limit the overrepresentation of any particular occupation, sector or nationality.

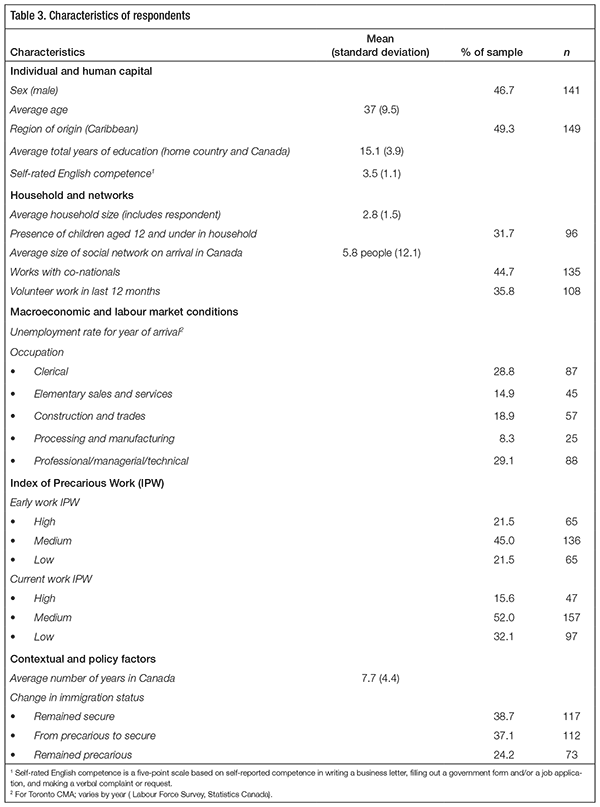

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the sample and presents information for the variables used in the logistic regression analysis.25 With an average age of 37, the sample reflects a population that was squarely in the work stage of the life cycle. The sample had considerably higher rates of educational attainment than the Latin American and Caribbean population of Ontario as a whole. Only 11 percent of Ontario’s Latin American and Caribbean immigrants have a university degree, in contrast to 26 percent of the sample (Lindsay 2001; Statistics Canada n.d.). The sample population tended to have small households with an average size of 2.8 people, and 31.7 percent of sample households had at least one child under age 12 living at home. We found 44.7 percent of the respondents worked with co-nationals or people from the same region, that is from Spanish-speaking Latin America or the English-speaking Caribbean, most of the time; 35.8 percent had done volunteer work in the last 12 months at the time of the survey. The sample was well distributed across a range of sectors that include sectors in economic decline, such as manufacturing, and important growth sectors of the new economy, such as services and construction.

Table 3 includes a breakdown of the sample by the IPW for early work (the respondent’s first year of work in Canada) and for current work (the respondent’s main occupation in 200506). The early work IPW shows that 21.5 percent of the sample had a high IPW score during their first year of work in Canada; they experienced between six and eight of the indicators of precarious work presented in table 1. Forty-five percent had a medium IPW score during early work, answering yes to between three and five of the precarious work indicators. Another 21.5 percent scored low on the IPW, answering that during their first year of work in Canada they had experienced none, one, or two of the indicators of precarious work. The IPW distribution of the sample shifts for current occupation. Over 15 percent of the sample had a high IPW score, the bulk of the sample (52 percent) fell into a medium IPW range, and a larger proportion (32.1 percent) scored low on the IPW. There was a general improvement in the IPW distribution from early work to current work for the sample as a whole.

Table 3 also provides a breakdown of the sample by legal status change. The data show that 38.7 percent of the sample stayed secure (retained landed status or went from permanent resident to naturalized citizen), 37.1 percent regularized (moved from precarious — temporary or unauthorized — to secure status) and 24.2 percent stayed precarious.

The logistic regression model tests which variables predict the odds of an immigrant worker falling into a higher or lower category on the IPW. We estimated this probability for two separate equations, first for the early work IPW and then for the current work IPW. Here we present findings for current work and make reference to findings for early work.26 Table 4 presents the results of the logistic regression for the dependent variable “current work IPW.”

Demographic and human capital factors are inconsistent predictors of the likelihood of having more precarious work. Whereas region of origin — Latin America or the Caribbean — was a statistically significant predictor of the early work IPW score, this did not hold true for the current work IPW score. The immigrant workers from the Caribbean were more likely to fall into a higher category on the early work IPW than immigrants from Latin America. However, for current work, region of origin is not statistically significant. Gender was not a significant predictor of precarious work for the first year in Canada but was a statistically significant predictor of falling into a higher IPW category for current work. Women were more likely than men to be in precarious forms of employment for current work. Education, which we measured as total years of education in the country of origin and in Canada, was not a statistically significant predictor of precarious work.27 Education did not protect these newcomers from falling into precarious employment during their first year in Canada or in their work in 2005-06.

In contrast, the variable self-rated English competence was a highly significant predictor of current work IPW scores. Combined with the model results for the predictor region of origin, this suggests that language proficiency does help explain differences in work precarity. Those with higher competence in English were more likely to have a less precarious job. However, in a related analysis, we found that attending or having attended language classes (English or business English) was not a significant predictor (Goldring and Landolt 2009a).28 Additionally, workers from the Englishspeaking Caribbean were more likely to fall into a higher IPW category than Spanish-speaking Latin American workers during their first year of work in Canada. This suggests that race, specifically being of African descent, may counter the positive effects of English-language competence. This is consistent with the findings of stratification scholars who flag the importance of race and racialization as a key determinant of labour market outcomes for immigrants and their Canadianborn children (Pendakur and Pendakur 1996; Teelucksingh and Galabuzi 2005).29

The impact of household composition and social networks on precarious work was mixed. Household size was significant and positive, meaning that respondents living in larger households were more likely to hold highly precarious jobs. However, the presence of children under age 12 in the household was significant and negative: respondents with young children were less likely to have jobs with high IPW scores. Volunteering — one of the three social network variables in the model — was a significant predictor of current work IPW scores. Respondents who had volunteered in the last 12 months were significantly less likely to be in jobs with high IPW scores than those who had not. The extent of a respondent’s social network and working with co-nationals were not statistically significant predictors of precarious work.

Challenging the predictions of human capital explanations of immigrant labour market incorporation, the number of years in Canada was not a statistically significant predictor of job quality for our sample. Time in Canada was also not a significant predictor of income security (Goldring and Landolt 2009b). In contrast, early work experience was an important predictor of job quality for current work. Respondents whose early work IPW score was medium or high were at increased risk of falling into or remaining in a higher IPW category for current work than respondents whose early work IPW score was low. Precarious work during the initial settlement period had a lasting — and negative — impact on workers.

An immigrant’s legal status at time of arrival was a significant predictor of the current work IPW score. People in our sample who arrived in Canada with a temporary permit or no work permit and stayed precarious (such as students, tourists, refugee claimants and temporary foreign workers) were more likely to fall into a higher IPW category than those who entered and stayed secure. This was also true for respondents in the “regularized” category, those who entered with precarious status but eventually obtained secure status. Those in the “stayed secure” category had better employment-related outcomes, as measured by the probability of having a lower IPW score. Thus, precarious legal status at time of entry into Canada had lasting negative effects.

To gauge the importance of broader macroeconomic and labour market conditions on respondents’ IPW scores, we used the unemployment rate in the year of a person’s arrival as an independent variable. It is not significant. However, sector of employment was significant. The regression calculates the likelihood of respondents’ having a higher current work IPW score in different sectors of employment, with professional/managerial/technical workers as the comparison group. Respondents in the clerical and construction sectors were more likely to be in a high IPW category than those in management. Respondents in either sales and services or processing and manufacturing were not any more likely to be in a high IPW category than those in management. For our sample, then, broader macroeconomic trends seem to be less important than sector-specific features in determining the composite precarity of a job as measured by the current work IPW.

We draw on qualitative data from the survey to further analyze the relationship between precarious employment and precarious legal status over time.30 We focus on the subsample of respondents who entered Canada with precarious legal status and then shifted to secure status (permanent resident or citizen). The subsample is conceptually significant. On the one hand, migrants with authorized but precarious legal status who transition to secure status approximate the two-step probationary immigration system that is a centrepiece of the federal government’s revamped immigration selection model (figure 3). On the other hand, as we suggest in our analysis of the current or fourth immigration model (figure 5), some newcomers may fall out of status and experience churning or rotation through various forms of precarious legal status. We can therefore expect some migrant workers who go through periods of unauthorized precarious legal status to also transition to secure status. The qualitative data offer a glimpse into the employment experiences that shape the long-term labour market incorporation experience of migrant workers with authorized or unauthorized precarious legal status who manage to move to secure status.

Precarious legal status migrants live in a restrictive regulatory context that has cumulative and highly corrosive consequences. Migrants with unauthorized precarious legal status, such as tourists who overstay their visas or rejected refugee claimants, face blanket restrictions in social and economic spheres. Migrants with authorized precarious legal status, such as refugees, international students and temporary migrant workers, are legally entitled to certain public services. However, temporary authorized residents are assigned a social insurance number (SIN) beginning with the number 9, a highly visible marker of their temporariness (cf. Montgomery 2002).

Precarious legal status migrants, both authorized and unauthorized, face restrictions that condition their engagement with public and private institutions in Canada. In Ontario, they are denied entry into federal and most provincial government-financed immigrant settlement programs and services, such as free English-language classes and employment counselling. They are also charged international student fees at all post-secondary educational institutions, making recertification or educational advancement financially prohibitive. In our research, we found that authorized migrants with a SIN that begins with 9 also have difficulties opening a bank account, getting a landline telephone, accessing bank credit and applying for a credit card. One Caribbean respondent commented about how having a SIN starting with 9 affected the search for work:

First of all, when you have a work permit, it specifies you either have to get an open [work] permit or a specific permit that says you’re only allowed to work in this field. With an open permit, you’re allowed to explore all the jobs that are there, but more than likely very few people are going, to hire you with a 9, which means your temporary status — it kind of limits you, even though it gives you an open permit that says apply for how many jobs you want. When you come with your qualification, then you put a 9 in front of that, it changes the dynamics of what you are entitled to get. (interview no. 265)

Having a SIN starting with 9 constrains the job search. There is a gap between the formal rights associated with authorized but temporary status,which provides the right to work in any field, and employers’ hiring practices: employers tend to avoid hiring workers with temporary migratory status.

Regulatory barriers have cumulative impacts: restrictions in one sphere compound vulnerabilities in other spheres. As noted above, respondents with precarious legal status are excluded from government-funded English-language programs, even though, like many immigrants, they identify language and accent as central barriers to securing a decent job:

What I felt affected me [looking for work] was my English. It was not fluid. Even now, the accent, there are some people that make “remarks” to point out your accent; they mention it to you, they have mentioned it to me…At my ast job I had to quit because he [my employer] placed too much emphasis on my accent and my race. (interview no. 111)

Without “standard” Canadian English, precarious legal status migrants felt they were unable to advocate for themselves at work and beyond.

Regardless of education and work experience prior to coming to Canada, lack of a work permit or having only a temporary work and residence permit meant that respondents with precarious legal status settled for any job they could get, often cash jobs in cleaning, construction or caregiving:

People are willing to hire illegal people, but like the type of work, of course you have to take what you get, the type of employer, you take what you get…You don’t have a wide variety, right, because you don’t have a social [insurance] number, you’re illegal, right. So when a job situation arises, it might not be much but you’re willing to take it because, what else is there? You’re not going to be able to go through unemployment insurance or anything so — social services, no, so you take what you get, because who’s going to take care of you? (interview no. 226)

Lack of work authorization meant a self-imposed limiting of the job search, focusing on jobs one would be likely to get, and where few questions would be asked:

Prior to becoming a landed immigrant, the only jobs — even though I knew better and I had skills and I knew that I could do all these things — but the only jobs I thought were within my range were cleaning people’s houses, working in a factory or taking care of people’s kids in their house, right. Um, those were also the jobs that you were less, um…intrusive, people weren’t going to ask you about your personal business, they weren’t going to ask you how you got there, can I see your proper insurance number. (interview no. 265)

In settling for what they could get, many respondents found themselves in jobs that meant deskilling; they were doing work they would not have done before coming to Canada:

My husband…had always had his own business, worked in an office. He didn’t know anything about carpentry; in his life he’d never held a hammer except to hang something at home…He had never done that, and it pains me that he is doing this, because he never had to do it in his life, so he never had a chance to study. [He] always had to work to sustain us, so that we could live here. (interview no. 22)

Precarious status meant that the respondents were placed in work situations characterized by limited workplace regulation, little worker control and virtually no recourse in the face of abuse or exploitation. Employers who hire people without work permits can get away with illegal or unfair practices. Respondents provided examples of harassment, intimidation, cash payment and wage theft by employers.

Employers use the temporariness of refugee claimants’ status, and specifically the SIN starting with 9, to generate uncertainty and secure workers’ compliance. One man remembered an early employer’s strategy to keep refugee claimants working for him:

Another thing he said to me was that because of my status — when I was a refugee claimant — that companies in general discriminate against people with a 9 on their SIN because they don’t have the certainty that the person will be staying in Canada. He would say these kinds of little things, and of course it made one scared. And we would limit our looking for other work opportunities. (interview no. 51)

Employer harassment reflects the social practice of a restrictive regulatory environment. Having a SIN beginning with 9 demarcates the boundaries of migrants’ participation in Canadian labour markets and society. It puts migrant workers in abusive and vulnerable work situations.

The vast majority of respondents who shifted to secure status had experienced nonpayment or underpayment of wages, particularly when they first entered the Canadian labour market: “That happened to me a couple of times. I lost about $3,000,” one respondent said (interview no. 4). The impact on workers of wage theft was often compounded by lack of information about their rights and the vulnerability of their legal status:

I think in my first year they stole from me maybe more than 60 percent of the times I worked; that it was a very precarious situation; that even though I spoke English — I spoke English when I arrived here — my lack of knowledge of the context, the surroundings. (interview no. 136)

Employers, they overwork you and then they underpay you: “Oh, your salary is XYZ,” but when the end of the week comes, it ends up being ABC, so they give you less than what they planned on giving you. If you talk, they get angry and fire you. (interview no. 237)

For some Latin American respondents, limited English compounded the vulnerability of their legal status; their lack of voice translated into limited information and recourse:

In the beginning, because I didn’t know the language, I had to accept everything; one time they didn’t pay me…in this company where I did occasional work. I did a job but I did not know my rights, so when I went to ask for my pay they had discounted, and it wasn’t for the government — it was a fine or something like that. Really they never explained it to me; they didn’t explain and they never paid me the money that they should have paid me. It was a dirty trick…I worked all day and they did not pay me. (interview no. 146)

Employers sometimes rationalized underpaying workers by arguing that they were helping the worker in some other way. One respondent was sponsored by her employers for the Live-in Caregiver Program; the employers then used that relationship to underpay her:

I told them all the time, and she was like, “Oh, we have three kids and we have the mortgage and that’s all we can afford.” And then this is the part that humiliated me: they would always make you feel because they sponsored you, they can just pay you $250, because she would say stuff like, “Remember we sponsored you and we’re helping you in some way.” So that probably they thought that they did that so they could pay me $250 and I shouldn’t complain. But I told them all the time this isn’t adequate, it’s not enough…but because they sponsored me, they thought, OK, we can take advantage of her. (interview no. 261)

Respondents clearly identified the relationship between precarious status and aspects of precarious work such as cash payment and wage theft:

What happens is that as long as you don’t have your work permit and you work for cash, people abuse you. And, well, the truth is, yes, I was exploited a lot as well. I worked for very little money and I worked a lot of hours and a lot of those hours I was never paid…You would do the job just like any other person…but because of the papers…A person needs to eat, needs to buy stuff… You have to earn something…You accept and you accept…And it’s that way and the government should know about this. (interview no. 7)

Some workers and employers may prefer cash to avoid paying taxes, but cash payment generally means that employers have control over when, how and how much the workers get paid. One Caribbean woman recalled her first job as a nanny:

I consider them the family from hell because, like, they pay me, like, $100 every two weeks. I work from, like, 7 o’clock Sunday night, and Saturday morning I have to wake up and sit on the steps and wait for these people to wake and give me a paycheque. And when they woke up, they would say, ‘I’m sorry, Frances, I don’t have any cash to give you.’ And then I have to wonder how I’m going to get home because I don’t have any money to take the bus, so a lot of the times my sister would send her husband to come pick me up — [this] was, like, an every week thing. (interview no. 280)

Unsurprisingly, the search for work with unauthorized precarious status leads to precarious work. However, temporary authorized migrant workers also face difficulties finding work because of the SIN starting with 9 and often end up in precarious jobs. Precarious status migrants, with or without work authorization, spend prolonged periods in precarious work, are likely to remain poor and have limited opportunities to improve the terms and conditions of their employment or invest in education as a stepping stone to less precarious, more decent work (Landolt and Goldring, forthcoming).

Precarious employment is certainly not limited to immigrants or people with precarious migratory status. However, precarious legal status has certain specific features rooted in the vulnerability of temporary authorized status and unauthorized status: precarious status workers cannot afford to complain about work and related violations, cannot easily train or retrain for better work and, in some cases, cannot even search for new jobs. Their legal status constrains opportunities for getting better work, as they need to continue to earn a living to meet daily costs and regularize their status.

Our research leads us to call for reframing the study of the economic incorporation of immigrants in Canada. Contemporary migration policies and trends are changing the dynamics and complexities of Canadian labour markets and patterns of immigrant incorporation; research questions, approaches and data need to map these contemporary realities more closely. While our small sample size precludes wide generalization, it does raise important issues for consideration. In this concluding section, we summarize key findings from our research and discuss implications relevant to researchers, policy-makers, service providers and migrant advocates.

Our review of immigration models leads us to question assumptions in the currently prevailing three-track immigration model, with its paths for permanent, temporary and probationary entry. These include the assumption that the tracks are bounded, with little movement between or off tracks, and that movement from temporary to permanent status for probationary entrants follows orderly steps toward permanent residence. We propose our chutes and ladders model as an alternative immigration model that provides a more accurate picture of contemporary policies and trends. The chutes and ladders model takes into account multidirectional legal status trajectories, recognizes the de facto settlement of people outside the category of “immigrants” and examines the role of social institutions and actors (including immigration policies, employment regulations and employers) in shaping legal status trajectories over time.

The chutes and ladders model challenges the assumptions of probationary categories associated with programs such as the PNP and the CEC. Rather than offering a clear bridge between temporary and permanent migration tracks and forms of legal status, these programs and policies, as we see them, are expanding the arena of probationary and necessarily precarious legal status trajectories. Then there is the issue of outcomes or effect over time: the language of two-step migration conveys the idea that, once an immigrant has moved to more secure status, the experience of precarious status becomes a thing of the past. A key finding of our research has shown that this is not the case: precarious status can have long-term negative effects on quality of work.

Taking the chutes and ladders model as a point of departure and reviewing recent data on permanent and temporary entrants and those still present, we see the importance of two trends. Others have noted the rising share of temporary migrants among all entrants each year, but we also note a similar pattern for temporary entrants still present in Canada. With the share of people who entered under temporary permits going up, it is likely that the number and proportion of people with or moving between forms of precarious status (authorized and unauthorized) is also rising.

Some may prefer to ignore the rise of de facto settlement, but we argue for a wider definition of the “immigrant” category in studies of newcomer incorporation. People with ongoing roles in the labour market should be counted in studies of labour market incorporation. This means studying the incorporation of all newcomers, regardless of legal status, and revising research questions, methods, data and indicators. Our research design allowed us to gather employmentand migration-related information from people in a variety of legal status situations, including temporary entrants, visa and permit overstayers and people denied refugee status. It also allowed us to explore the relationships between various legal status trajectories and work outcomes. If we had limited our study to those classified as immigrants, we would not have been able to examine the role of changes in legal status over time.

To summarize, de facto immigration is taking place, so all newcomers should be included in research on immigrant incorporation. The permanence of temporariness cannot be ignored; precarious status migrants are part and parcel of local labour markets, families, schools, neighbourhoods and communities. Research on work can and should reflect the experience of workers in general and immigrants in particular.

Job quality and labour market outcomes are increasingly measured with multiple indicators that allow researchers to examine precarious employment as a multidimensional experience. Labour market informality, deregulation and employer strategies aimed at violating or evading regulations need to be included when developing measures of employment precarity. Our Index of Precarious Work offers a way of measuring job quality that is robust enough to capture these features of contemporary labour market insecurity.31 This particular index, like the use of composite measures more generally, is critical to the analysis of immigrants’ labour market insecurity but should not be used only in research on immigrants.