Voter turnout has been in decline in Canada since the late 1980s. In the decades following the Second World War, there was an average turnout for federal elections of approximately 75 percent; during the past two decades, however, the average percentage has dropped to the low 60s. Similar drops are being witnessed in most other established democracies. There is also mounting evidence that this phenomenon is having a variable impact on our society – the largest voter turnout decline is among young people.

While any drop in turnout is cause for concern, the fact that young people are among the most disenfranchised in society is especially troubling. Voting appears to be a socialized behaviour learned early in life. Therefore, if the young fail to vote when they reach the age of majority, it is possible that they will remain forever disengaged from the political system. It is even possible that the current low participation rate will extend to future generations.

Not surprisingly, the decline in turnout has been of growing concern to political scientists and politicians during the past 20 years. When turnout dropped below 62 percent in the 2000 federal election, many – including the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada – were forced to acknowledge that if the trend continued, then Canada may need to consider compulsory voting. The practice has been instituted in more than 20 democracies around the world. A sanction (usually minimal) is imposed on any citizen who fails to go to a polling station on election day and cast a vote. The impact of compulsory voting is significant. Countries where it is practised have an average turnout rate that is 15 percentage points higher at the federal/national level; the turnout rate at the provincial/ regional or local level is even higher.

The effectiveness of compulsory voting is without question. Advocates have also claimed that compulsory voting will lead to a more engaged and informed electorate, but this has yet to be empirically verified. In this study, Henry Milner, Peter John Loewen and Bruce Hicks tested this claim by engaging in a unique experiment involving college students who were eligible to vote for the first time, in the 2007 Quebec election. They asked two groups of students to complete two surveys (the first before the election and the second after the election), for which they would be paid. One group, however, was told they would only receive their remuneration if they voted. By comparing the results, the authors could ascertain whether a financial disincentive to abstain motivated young citizens to inform themselves about the election.

This study contributes to the debate over this important and complex question. Generally, it explores some of the issues surrounding mandatory voting. More specifically, using the Quebec provincial election of 2007, the authors have designed and implemented a field experiment aimed directly at young people (the group of voters likely to be most positively affected in terms of turnout if voting were compulsory) in order to determine the implications of compulsory voting on political knowledge and engagement. The experiment has shown that when a young person is made to vote in an election, his or her attentiveness to politics or knowledge about politics does not necessarily increase. Does this mean that compulsory voting would not have a beneficial impact on young people over the long term? Do arguments in favour of compulsory voting outweigh the counter-argument that compulsory voting would merely increase the number of ill-informed voters? Would political parties change their behaviour if faced with a larger number of voters?

Canadians need to discuss such questions, and this paper attempts to set out, in a dispassionate manner, many of the issues that will facilitate the discussion. It also contributes research on one particular aspect of the debate: the direct, short-term impact of compulsory voting on young nonvoters’ political knowledge. In short, this paper is a salvo in the debate over compulsory voting – a debate that is likely to continue as long as voter turnout for Canadian federal, provincial and municipal elections remains low.

Does compulsory voting lead to a more engaged and knowledgeable electorate? That it results in higher levels of political participation is without question. However, the second-order effects of compulsory voting, especially its effects on political engagement and knowledge, are not well established. This paper provides an analysis of the results of a field experiment carried out during the Quebec provincial election campaign of March 2007. The purpose of the experiment was to determine whether compulsory voting and voting incentives lead to more attentive and knowledgeable voters. Advocates of compulsory voting generally claim that it will lead to a more engaged citizenry; in particular, they claim that the currently disengaged will inform themselves as a natural byproduct of having to vote.1

In examining this aspect of compulsory voting, we do not cast judgment on its overall merits. There are other arguments in favour of compulsory voting, such as those related to political equality in a democracy and to the fact that increased turnout may compel political parties to reach out with their policies to disengaged communities. However, voter knowledge is a dimension of compulsory voting that proponents incorporate to varying degrees in their argumentation, and it has yet to be put to an experimental test.

In this paper, we provide experimental evidence that casts some doubt on the claim that the act of voting, as forced by sanction or encouraged by incentive, will cause voters to become information seekers. Following this introduction, the paper is separated into two parts: in the first, we present arguments for and against compulsory voting and incentives, touching on experiences in other countries, we look at the debate in Canada and we present a review of the empirical literature on the effects of compulsory voting; in the second part, we describe the methodology and the results of our experiment. We conclude with a discussion of our findings and an assessment of their wider implications.

It is well known that voter turnout has been declining in most advanced democratic countries — Canada certainly included. From the Second World War until 1988, this country had a consistent participation level among registered voters in federal elections; it averaged about 75 percent. But in the past two decades, that percentage has dropped steadily, reaching the low 60s. Various studies have shown that in Canada and elsewhere, this trend is largely attributable to the voting — or, rather, nonvoting — habits of the new cohorts of voters who reached voting age during this period (Milner 2005; Blais et al. 2002; O’Neil 2001).

In most countries, second-tier (provincial) and third-tier (municipal) elections usually have lower voter turnout than first-tier (presidential or parliamentary) elections. In Canada, turnout for second-tier and third-tier votes has historically lagged behind turnout for elections at the federal level by between 15 and 40 percentage points, but the gap has decreased as federal electoral participation has fallen (though with noticeable variations by province, city and town, and by election).

We should note, since the experiment used for this study was carried out in Montreal during a provincial election, that the Province of Quebec has in the last four decades consistently been an exception, with turnout rivalling — and sometimes exceeding — that for federal elections in Canada. However, in recent Quebec elections, turnout levels have also begun to decline; the 2003 provincial election engaged only 70 percent of registered voters.

Very little research has been done using cohort analysis at the provincial level but, based on evidence from federal elections, it is reasonable to assume that there is a strong cohort differential here, too, with young people failing to participate at the levels of previous generations. Decline in youth voting is additionally troubling because voting patterns in early elections can carry forward into future elections. The initial voting experience affects whether or not a citizen will be politically engaged or disengaged — those who fail to vote early in life may remain nonvoters as they age (Franklin 2004; Green and Shachar 2000; Gerber, Green and Shachar 2003).2 Hence, if the decline in turnout around the world is disproportionately attributable to young people, and if the socializing effects of voting are weaker among the youth of today than among previous generations, then the issue of compulsory voting and voting incentives is of particular relevance to them.

There is also evidence that low socio-economic status is linked to low voter turnout (Hicks 2006; Blais 2000; Bakvis 1991). Uneven turnout based on race, ethnicity and class is worrisome in that it could lead to certain segments of society exerting greater influence on elections and thus on government programs and policies. As Linder has noted with respect to Switzerland, “especially when participation is low, the choir of Swiss direct democracy sings in upperor middle-class tones” (1994, 95). While not all agree that election outcomes would differ greatly if there were full turnout (Rubenson et al. 2007; Martinez and Gill 2006; Citrin, Schickler and Sides 2003), the possibility alone is cause for concern.

The fundamental objective of compulsory voting is to increase voter turnout (Watson and Tami 2001). That this happens is clearly supported by the Australian and European experiences. In addition, compulsory voting is credited with decreasing disparities in participation due to age and socio-economic background. This is particularly true when fines for not voting are levied and when voting is made compulsory in second-tier and third-tier elections. Yet in all the discussion about compulsory voting in the literature, and despite proponents’ Henry Milner, Peter John Loewen and Bruce M. Hicks claims that compulsory voting will lead to a more knowledgeable electorate, the one thing that is not examined empirically is how such initiatives might affect the political attentiveness of citizens. In short, we do not know if people who cast a ballot under threat of financial penalty are any more likely to educate themselves about the issues and candidates.

In the context of a generation-linked turnout decline, it is appropriate to focus on young people who have just arrived at voting age. Since the young vote in such low numbers, the impact of compulsory voting should be greatest on them. This was suggested by Print, who found that among young Australians (aged 16 to 18) the percentage responding in the affirmative when asked if they planned to vote declined from 86 to 50 when the question was rephrased to determine whether they would still do so if voting were not compulsory (2006).

Our study involved young people living in the Montreal region, and the election was a Quebec provincial one; we found our participants at a college chosen for its large number of students from a diversity of ethnic groups and socio-economic backgrounds. But there is nothing inherent in this experiment that required it to be carried out where and when it was. Indeed, it could have been conducted around an election at a different political level or in another democratic society. We chose to focus on this particular election because during the election period, the necessary resources and cooperation were available to us: we were physically present in Montreal, and we had access to a group of young people at the cusp of the legal voting age. There is nothing about the milieu from which the participants were selected that precludes the findings of this study from being generalized to youth in other jurisdictions and, perhaps, to all voters.

The circumstances surrounding the March 2007 Quebec election were very promising, as far as participation was concerned. Not only had several measures to facilitate ballot access been instituted for 2007 by the Directeur geÌneÌral des eÌlections (DGE) — extending the period for advance polls, removing any obligation to justify using them, installing voting booths in seniors residences and allowing those with impaired mobility to vote at home3 — but also the race was unusually competitive. Indeed, many observers characterized it in the lead-up as the most interesting in a century, with three political parties competing to form the government all the way to the end; and this should have stimulated turnout (Franklin 2004; see also Blais 2006). Yet turnout improved only marginally: up 0.79 percentage points from 2003. Clearly, many people, including young ones, did not vote. It is thus timely to look more closely at reforms that could boost turnout, such as compulsory voting and voting incentives.

The decline in voter turnout in democratic countries in recent decades has renewed interest in compulsory voting and voter incentives (Wattenberg 2007). But such measures have been employed since the birth of democracy — the first time was in the direct democracy of ancient Athens. In that city-state, the People’s Assembly was convened on a hill called the Pnyx. To force people to attend, officials corralled them from the agora (marketplace) below using a rope soaked in red dye (Hicks 2002); the clothing of tardy or unwilling participants was marked by a red stain; there may also have been a fine for nonparticipation (Hansen 1999, 5). Thus were born two of the incentives used today in compulsory voting: public stigmatization and financial penalty.

The vast majority of Athenians were wage earners, and many had to travel great distances to attend the assembly, so in 403 BC, when democracy was reintroduced, assembly pay was given to the poor to cover the costs of attendance (Mavrogordatos 2003, 7). Eventually, assembly pay became the largest expenditure item in the Athenian budget (Hicks 2002). In 380 BC, Plato, who had no love for democracy, ridiculed the practice: “I hear [Pericles] was the first who gave the people pay, and made them idle and cowardly, and encouraged them in the love of talk and money.” This was the genesis of the debate over compulsory voting and voter incentives — specifically, the cost to the state versus the actual benefit to both the state and the individual.4

In the modern era, compulsory voting began to emerge in representative democracies with the extension of the voting franchise. It was first introduced at the national level in Belgium in 1892, in Argentina in 1914 and in Australia in 1924. Some countries that adopted compulsory voting later reexamined and abandoned it (for example, the Netherlands in 1971 and Italy in 1994); a good number have maintained the practice.

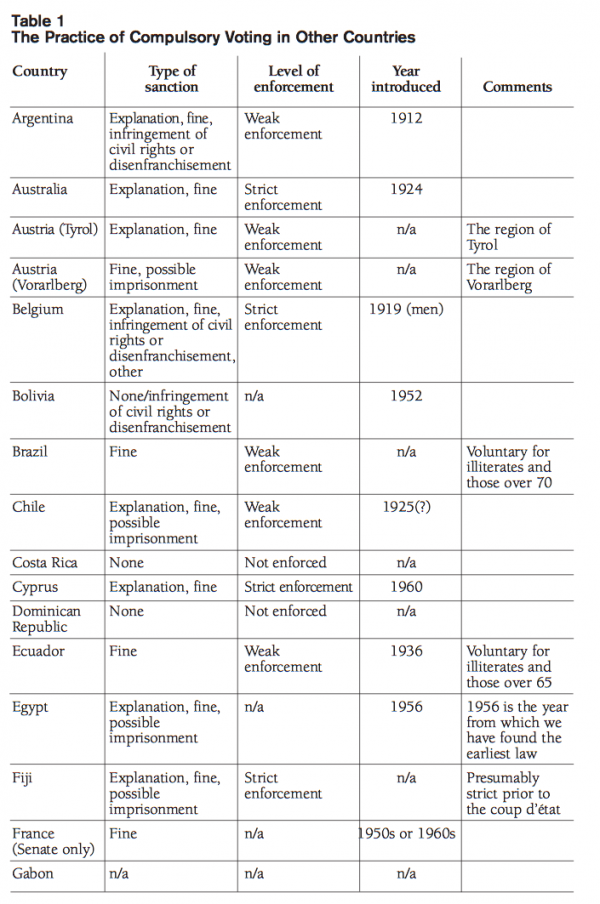

Table 1 reproduces Gratschew’s charting for the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) of the basic information about the democratic countries that, as of 2001, had some form of compulsory voting (2001). As we can see, there were dramatic differences in the sanctions imposed and the degree of enforcement.

The most effective tool for boosting voter turnout is, of course, the fine. As Gratschew found, 20 countries use fines, and the amounts vary by country, though most are nominal. For example, Switzerland fines nonvoters 3 francs; Argentina, 10 to 20 pesos; and Peru, 20 soles (all of which are equivalent to less than 7 Canadian dollars). Australia imposes fines of about 20 Australian dollars (17 Canadian dollars). In 13 countries, nonvoters are simply required to provide an explanation, and, if that explanation is deemed legitimate, then no further sanction is enforced (if any exist).

A variety of sanctions have been employed as alternatives to fines. For example, in Belgium, a person who has not voted in at least four elections during the previous 15 years can be disenfranchised. In Peru, voters must carry stamped voting cards for several months after an election as proof of having voted; the cards have to be shown at some public offices before services will be rendered. In Singapore, nonvoters are simply removed from the voter register until they apply to be reinstated. And in Bolivia, voters must produce their voting cards for three months after an election or be denied payment of their salary through a bank. Some communities in Italy have simply posted the names of nonvoters on the town hall door in order to embarrass them; and, in some cases, nonvoters are refused services such as daycare. Mexico similarly relies on arbitrary social sanctions. In Belgium, nonvoters may have difficulty getting a job in the public service, and in Greece, they may encounter difficulties obtaining a new passport or driver’s licence. Worldwide, six countries use formal infringements of rights or disenfranchisement to encourage turnout, and four rely on moral suasion and peer pressure. Only four countries use imprisonment. While there does not appear to be any documented case of a person being imprisoned for not voting, there is some lack of clarity on this issue — in Australia, for example, the only sanction is a fine, but if the nonvoter does not pay that fine after several reminders, he or she faces the possibility of incarceration.5

Equally significant is the level of enforcement. Only nine countries have strict enforcement; twice as many have weak enforcement or no enforcement at all. And there are eight countries that have compulsory voting legislation that contains no sanctions whatsoever. We should note that what we mean by “compulsory voting” in this context is required attendance at the polling station. The state cannot force a person to vote without drawing back the veil of secrecy that is essential for fair balloting in a democracy. Voters are at liberty to spoil their ballots, and in some countries that have compulsory voting, voters are able to register their abstention on their ballots.

There is also an alternative to imposing restrictions on citizens through legislative compulsion — namely, to offer an incentive. This measure was also used in ancient Athens. While it is not employed widely in the modern era, it is increasingly discussed as an alternative to compulsory voting, since it avoids the politically and emotionally charged issue of making democratic participation compulsory. A voters’ lottery has been used in municipal elections in the town of Evenes, Norway, and it appears to have increased voter turnout (Ellis et al. 2006, 58). Korea is considering using lottery tickets or gift vouchers to stem its turnout decline (“Voting Incentives” 2006). Closer to Canada, a referendum was held in Arizona to decide whether the state would offer each voter the chance to win a million dollars; the proposal made it onto the ballot in November 2006 but was rejected by a margin of two to one (Arizona Secretary of State 2006, 15).

Such incentives are intended to boost voter participation, yet nothing matches compulsory voting in this regard. Approximately 18 percent of European countries use some form of compulsory voting, and all are among the 45 percent of European countries with the highest voter turnout; four of the countries in that 18 percent group are on the list of the top five voter-turnout countries (Keaney and Rogers 2006, 27). When Australia introduced mandatory voting in 1922, its turnout was 57.9 percent; this figure rose to 91.3 percent in the next election in 1925. Voter turnout in that country has averaged about 95 percent since the Second World War (Butt et al. 2006). Similarly, turnout in Belgium has averaged about 93 percent since 1946 (Bennett 2005). In the Netherlands, the average difference in voter turnout before and after the change was 10 percent. This is similar to the difference in presidential election turnout between those Austrian provinces that maintained compulsory voting and those that removed it during the 1980s (Hirczy 1994). When Costa Rica and Uruguay introduced penalties for not voting, their turnouts increased by 15 and 17 percentage points, respectively; and when the Netherlands and Venezuela removed such penalties, they experienced turnout declines of 20 and 30 percentage points, respectively (Watson and Tami 2000, 7). Though estimates of the increase in turnout due to compulsory voting measures vary, every study of Western democracies reports that increase as being between 10 and 15 percentage points for national elections (Jackman 1987; Blais and Carty 1990; Blais and Dobrzynska 1998; Franklin 1996, 2004; Blais and Aarts 2006). And Jackman goes so far as to argue that compulsory voting is the only institutional mechanism that can achieve voter turnout levels of over 90 percent (1987).

Even without sanctions, first-tier elections usually have higher voter turnout than secondand third-tier elections, so turnout increases more dramatically when compulsory voting is applied to subnational elections. In the case of Australia, combining the turnout increase in the various state elections with that in the federal election reveals an average increase of between 12.4 and 37.8 percentage points before and after the introduction of compulsory voting (McAllister and Mackerras 1998, 2).Lijphart points out that “The power of mandatory voting is highlighted by the fact that when it is applied to local elections — as it is in all nations with compulsory voting except Australia — turnout levels are almost the same as those for presidential and parliamentary elections” (1996, B4). In sum, that “compulsory voting increases turnout [is] a well-established proposition” (Blais 2006, 114).

However, overall turnout is not the only issue related to voter participation. To many, an even more important question is whether there is a turnout differential between various societal groups. If there is, it could result in some segments of society exerting greater influence than others — a phenomenon that would have a number of sociological, economic and even psychological ramifications. As we have noted, the decline in youth participation is now seen as the primary cause of declining voter turnout in many countries; this trend may be increasing within cohorts of young people and could continue as they age (Keaney and Rogers 2006; Milner 2005; Franklin 2004). Additionally, lower turnout may be affecting people disproportionately based on race, ethnicity, education, income and a number of other socio-economic factors. Compulsory voting has the benefit of raising participation rates across categories of citizens. For example, Lijphart, by placing Netherlands voters in a hierarchy of five levels of education attained, found that turnout fell in all groups from above 90 percent to between 66 and 87 percent following the abolition of compulsory voting in 1970; the group with the highest turnout was the one with the highest level of education (1997). A simulation of what would happen in Belgium suggests that there would also be a great disparity in voter attrition; turnout declines among those with low levels of education or professional status would be the most dramatic if compulsory voting were abolished (Hooghe and Pelleriaux 1998).

The idea of compulsory voting is not new to Canada. It was first raised in the House of Commons in 1920. Andrew McMaster, a Liberal MP, claimed it would “eliminate a large number of the ways in which money is, or has been, illegally spent at elections.”6 This gave an unusual twist to the voter-turnout argument by suggesting that if turnout were higher, then it would no longer be possible to buy votes (Hicks 2002).7 The usual motivation for the introduction of compulsory voting is the desire to increase turnout, and just four years after this Canadian House of Commons debate, Australia — in response to the 57.95 percent voter turnout in the 1922 election — adopted such a system.

The idea of compulsory voting surfaced during hearings of the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing (the Lortie Commission), as did the idea of voting incentives, though the commission made scant mention of either of these ideas in its report to the government on its public hearings (1991, 4:19). This is perhaps not surprising, given that discussion of compulsory voting was advanced purely in the context of voter turnout, at a time when Canada was still experiencing relatively high turnout levels. While Jerome Black’s research for the commission suggested that voter turnout in Canada was not as high or as stable as was widely believed, neither he nor Munroe Eagles nor Jon H. Pammett (the three political scientists asked to examine voter turnout for the commission) proposed compulsory voting. This led the commission’s director of research, Herman Bakvis, to conclude that compulsory voting was probably not in keeping with “Canadian mores and sensibilities” (Bakvis 1991, xx).

The commission itself did pass judgment on the merits of the idea. It concluded that it would be “unacceptable to most Canadians, given our understanding of a free and democratic society” (1991, 1:57), even though the idea of compulsory voting was never proposed to Canadians as part of the commission’s formal survey of public opinion (Blais and Gidengil 1991). Among the criticisms the commission levelled at the idea were that in other countries it had not increased turnout to 100 percent, and that the laws are rarely enforced “because citizens must be given the benefit of the doubt when they explain why they did not vote” (1991, 1:56).

Also relevant to the debate on compulsory voting was the commission’s consideration of whether, and which, citizens could cast a rational and informed vote — it identified this as one of the “four criteria for determining who should vote,”8 albeit “one that has always been more implicit than explicit in our electoral law” (1991, 1:35, 33). This principle of rationality and knowledgeability requires that citizens be able to exercise independent judgment and have the capacity to engage in political discourse; when combined with the criteria of responsible citizenship, it also requires that the state discourage “anything that would bring the vote into disrepute, or devalue it in citizens’ eyes” (1991, 1:34). It is upon these principles that the commission hung its recommendation that any person for whom a legal guardian has been appointed or who has been confined by reason of insanity, and anyone under 18 years of age, be denied the vote (1991, 1:41, 49).

The idea of compulsory voting arose again following the 2000 federal election, when turnout dropped to a level approximating Australia’s in 1922. Chief Electoral Officer Jean-Pierre Kingsley was asked about the possibility of Canada adopting a compulsory voting regime like Australia’s. His immediate response reflected the view of Canada’s political elite: he found the idea “repugnant.” But he added that “if we start dipping below 60 per cent, I’m going to have to change my mind.” The reaction of members of Parliament to the idea was almost universally negative. Public comments ranged from “it won’t fly in Canada” (Liberal MP Paul Steckle), to “it may work in Australia, but it won’t work here” (New Democratic Party MP Peter Stoffer), to “I think people do make a conscious choice to not go out and vote, and my feeling is they are entitled to make that choice” (Canadian Alliance MP Ted White).9 The views of these politicians also reflected public opinion: when asked, 73 percent of Canadians said they were opposed to compulsory voting (Howe and Northrup 2000, 28).

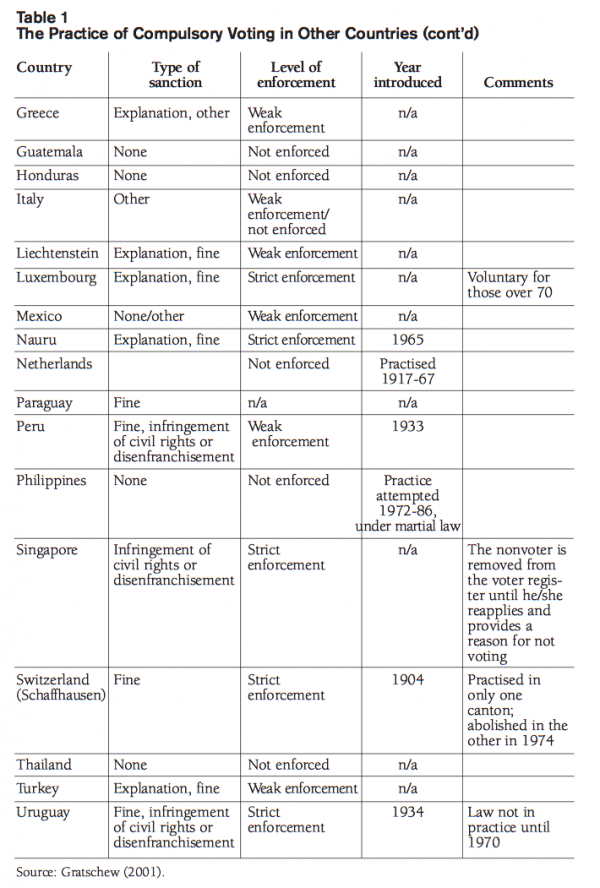

Most recently, Senator Mac Harb introduced a private member’s bill to make voting mandatory.10 His stated motive in introducing the legislation was that it constituted a “direct response to a rising electoral crisis” (2005, 4) — that is, voter turnout in recent Canadian elections had declined dramatically and was now approaching the 60 percent mark. As table 2 illustrates, turnout in Canada had been relatively stable, in spite of population growth, since the Second World War. The variations among elections could be explained by a number of factors, such as election timing, administrative rules (governing, for example, whether voters were allowed time off work to go to the polls, which day was selected for the vote, how many advance and regular polling stations were set up, and how thorough the enumeration was) and election saliency.

It is well established in other countries that different segments of society participate in elections at different levels based on the resources they possess (education, wealth) and the barriers they encounter (language, relevance of candidates and parties, prejudice). And while there are various interpretations of the degree to which socio-economic status affects turnout in Canada, it is widely acknowledged that “the proportion of low-income families in a riding is consistently a factor associated with lower levels of voter turnout” (Eagles 1996, 315).

Until recently, given the relative stability of voter turnout, electoral law review bodies such as the Lortie Commission and parliamentary committees have been singularly focused on improving administrative procedures, increasing voter awareness, strengthening political parties and ensuring public confidence in the integrity of the process. However, the decline in turnout for Canadian federal elections during the last two decades has given rise to additional concerns. The fact that this decline is concentrated among young people (Milner 2005; Blais et al. 2002; O’Neil 2001), and the possibility that it is causing certain ethnic groups and the more vulnerable members of society to become disenfranchised (Hicks 2006; see also Pal and Choudhry 2007), is beginning to generate renewed interest in electoral reform. Several provinces have adopted fixed election dates and are considering moving toward proportional electoral systems.

Yet this reforming spirit has not embraced compulsory voting, despite its being the only administrative mechanism that could immediately and significantly boost voter turnout in federal and provincial elections. Senator Harb was unable to win meaningful support for his legislation in the Senate. For Senator Don Oliver, a former member of the Lortie Commission, there was “something inherently anti-democratic about enacting legislation to essentially coerce or force Canadians into exercising their democratic rights.”11 Senator Jack Austin called compulsory voting an infringement on personal liberty,12 while Senator Noël Kinsella suggested that the right to vote set out in section 2(a) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms included the right not to vote.13 The legislation died on the Senate order paper when Parliament was dissolved in November 2005.

Like the Lortie Commission, Courtney has argued that the very idea of compulsory voting and sanctions may run contrary to basic Canadian values (2004). He suggests that classical liberal ideology has created a natural resistance in the electorate,14 and among Canadian elites, to the idea of any form of stateenforced voter participation. Given this apparent resistance to compulsory voting, Hicks had earlier suggested that Canada might be uniquely situated to instead follow the Athenian example and compensate lower-income Canadians for some of the costs they incur when voting (2002).15

In light of current trends, it is clear that the debate over ways to boost turnout will continue in this country for some time. While compulsory voting and voting incentives have received only limited consideration to this point, it is inevitable that attention will turn to such mechanisms, and an informed debate should be encouraged.

Clearly, the most compelling argument for compulsory voting is that it will boost electoral turnout, especially among the weakest in society. As we have seen, the most frequently voiced argument against it is the libertarian one: it infringes on individual freedom and personal liberty — that is, the right some argue is implicit in a free and democratic society not to vote. The central question then becomes: Even if it will increase turnout and reduce possible class and/or ethnic bias, is it democratic to compel people to vote, and can elections conducted under compulsion and threat of sanction be considered free and fair (Lever 2007)? It was a negative answer to this question that led to the abolition of this measure in the Netherlands in 1970.

Supporters of compulsory voting argue that “the benefits of increased legitimacy, representativeness, political equality and minimization of elite power justify the element of compulsion, especially considering the relatively minor restriction of personal freedom that is entailed” (Keaney and Rogers 2006, 30). Furthermore, they point out that when compared with civic obligations that are readily accepted as necessary for the good of society, such as performing jury duty and paying taxes, compulsory voting would be a relatively minor imposition on personal freedom (Engelen 2007; Hicks 2002). Opponents counter that refusing to participate can be a form of expression, that people need the power to withdraw legitimacy from their governments, and refusing to vote is one of the most peaceful ways to do this. Moreover, compulsory voting does not address the underlying causes of low voter turnout but masks them instead.16 If citizens are not voting, then it is incumbent on governments and political parties to address those causes.

There is, however, another side to this argument; namely, that where voting is voluntary, political parties expend sizeable resources mobilizing their own supporters rather than winning over undecided voters. In a compulsory voting environment, parties would be forced to engage with the groups least interested in politics and most dissatisfied with the political situation, rather than simply focusing on the party faithful and ensuring they vote on election day (Keaney and Rogers 2006, 29). If socio-economic status is tied to voter turnout, then compulsory voting would force politicians to engage with ethnic, linguistic and other minority communities, an essential undertaking in a bilingual and multicultural society like Canada (Hicks 2006).

Advancing arguments for or against compulsory voting and voting incentives to induce nonvoters to become full participants in the system invariably raises the thorny issue of the quality of participation. In fact, most arguments related to political participation hinge on three theoretical democratic pillars: citizen engagement, political representation and vote choice. Each of these has an informational component. Classic democratic theory as it emerge in the 18th century was predicated on an informed voter who thoughtfully considers the issues and arguments before casting a ballot. This leads to reasoned debate and the election of representatives who reflect the community. Social contract theory posits individual citizens coming together to form a collective will. Individuals are thus forced to subordinate their egoist natures, giving rise to a state that offers equal protection to all of the interests it contains. Even rational choice theory, which is based on a more self-interested citizenry, links voter turnout directly to information and the cost of acquiring it. The question then becomes whether compulsory voting results in better representation in Parliament for the electorate or in a failure to improve representation — since the measure would merely bring uninformed citizens to the polls and thus reduce the likelihood that well-considered choices would be made on political issues. And concern about uninformed voters determining electoral outcomes is what led John Stuart Mill to suggest that votes should be weighted based on on the elector’s degree of intelligence and ability (though he could think of no effective test of these qualities).

Milner makes the distinction between informed voters who do not vote out of apathy or as a protest and voters who fail to vote because they lack the basic information they need to do so — people whom he classifies as “political dropouts” (2005). Yet proponents of compulsory voting are optimistic that the very act of voting will have beneficial effects on the citizenry. Lijphart suggests that it creates “an incentive to become better informed…a form of adult education” (1997, 10), while Hill claims that voting can be a first step toward combatting social isolation and marginalization (2000).

When considering youth, the socialization dimension frequently emerges as central to the voting equation. Proponents of compulsory voting insist that if voting is a habit and a skill acquired in youth, and perhaps linked to other forms of civic duty, then compulsion is justified. But here, too, the debate invariably returns to divergent views on the quality of the participation.

In his well-known presidential address to the American Political Science Association in which he called for compulsory voting, Lipjhart suggested that such a measure would result in (among many other benefits) a more politically knowledgeable population (1997). Yet others argue that “whether or not this is true is open to conjecture” (Weller and Fleming 2003, 21). Bilodeau and Blais could find no empirical studies to support Lipjhart’s claim (2005). To fill the gap, they attempted to substantiate his claim in three ways, all of which were indirect and yielded inconclusive results. They first looked at people in western European countries where voting is compulsory to determine whether they discuss politics more than others. Then they looked at immigrants to New Zealand from compulsory-voting Australia. Finally, they looked at immigrants to Australia from compulsory-voting countries. In each case, they sought differences in reported levels of political discussion, interest in politics and attitudes toward voting, but they were unable to find evidence of socialization due to compulsory voting.

The same result emerged from a recent analysis of Belgian survey data by Engelen and Hooghe, who used a hypothetical question — “What if voting were not compulsory?” — in an effort to isolate those who vote to avoid sanction (2007). Another recent study, using data from the Polish Election Survey, employed the same method in reverse: it asked nonvoters what they would do if voting were compulsory (Czesnik 2007). Not surprisingly, those who reported voting to avoid sanction were the least interested and knowledgeable. Ballinger looked at the British and Australian evidence and determined that Australians are no better informed about political systems. He concludes that “compulsory turnout in Australia may have masked a system in which political knowledge, and especially youth engagement with politics, is not necessarily higher than we currently have in the UK” (2007, 9).

While these studies are suggestive, they display two methodological problems that hinder extending inference to the second-order effects of compulsory voting. First is the probability of a major difficulty with cross-national comparability when it comes to survey questions tapping political knowledge. It is very hard to establish that two national scales are measuring the same type and amount of political knowledge. Moreover, even if the scales are measuring exactly the same quantities, we cannot be certain that the same amount of knowledge would be required in each country for effective democratic citizenship. The second problem is that even if we can come up with directly comparable measures of survey knowledge, the analyst will still be confronted with unobserved heterogeneity. It is entirely plausible that the countries that adopt compulsory voting are the countries that have the least engaged citizenries. We cannot thus assume that any observed differences are a function of compulsory voting and not some unobserved variable in the populations.

In the absence of a change in electoral law within a given country, allowing for a before-and-after quasi-experiment, there is no unambiguous empirical basis for determining the second-order effects of compulsory voting. What we need, therefore, is a method that decouples compulsory voting from pre-existing levels of citizen engagement and knowledge. One such method is an experiment that randomly subjects some voters to a treatment resembling compulsory voting while subjecting others to a control condition. We now turn to one such experiment.

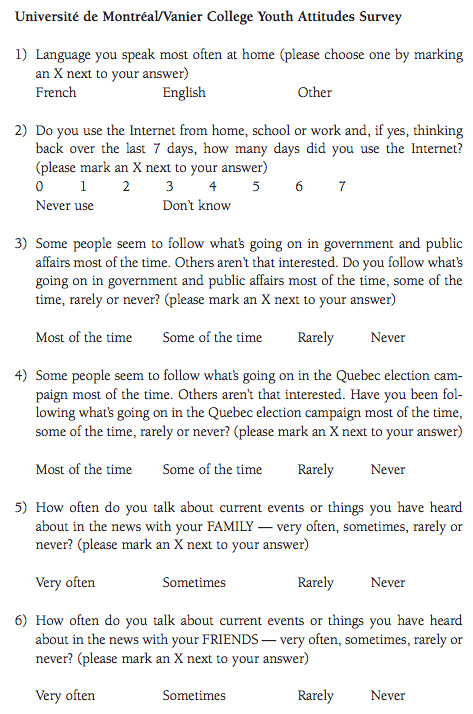

The logic of our experimental design is quite simple. We recruited a group of students at a Montreal junior college (a CEÌGEP) to participate in a study that consisted of two surveys we described as being about “youth attitudes”; these surveys were administered approximately one month apart — specifically, at either end of a provincial election campaign. All students who completed the surveys were eligible to receive $25, except for a randomly selected subset, who also had in addition to vote in the provincial election in order to be paid.17 We were thus left with one group whose members faced a financial disincentive if they chose not to vote, and another whose members faced no such disincentive. By comparing the differences between these two groups related to increased political knowledge, media news consumption and discussion about politics, we were able to draw strong inferences about the effects of compulsory voting and incentives on voters — especially first-time voters. As a result of our design, those in our treatment condition faced a financial incentive to vote. This may differ theoretically from the prospect of losing money by having to pay a fine, but we believe that it sufficiently approximates compulsion.

Quebec’s Directeur geÌneÌral des elections (DGE) is responsible for the administration of elections in the province, including the registration of voters and the administration of polling stations. The cooperation of his office made it possible for us to verify that our subjects voted; such verification had never been done before, and it required no small effort on the part of the DGE. The survey was conducted at Vanier College, a Montreal English-language CEGEP with over 5,000 students from a variety of socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds, the majority of whom are in pre-university programs.

Recruitment occurred in over 60 Vanier College classes. We specifically targeted students in social science and commerce general education courses — that is, courses with minimal admission requirements.18 The classes we chose were those most likely to contain students who on election day would be at least 18 years of age, the voting age in Quebec (as it is in the rest of Canada). Interested students were asked to fill out a registration form containing 10 otherwise unrelated questions,19 one of which was whether the respondent expected to vote in the upcoming Quebec election.

Once the election was formally announced, 205 of the students who had filled out the forms and who were eligible to vote were invited by e-mail or telephone to complete the questionnaire in a classroom at the college on a given date at a set time. The students who had said in their applications that they did not intend to vote or were unlikely to vote constituted the majority of the 205. Half of the 205 were randomly assigned to two treatment rooms and the other half were randomly assigned to two control rooms.20 Disappointingly, only 55 students showed up. All of them were given instructions, a research consent form and a questionnaire. The only difference was that the students in the treatment rooms were told that they would be obliged to vote in order to be paid. Students in the control group rooms were not told that any students were being asked to vote, or that the survey was associated in any way with the election; they were merely informed that they would be given a second questionnaire in approximately one month’s time.

To expand our sample, we then e-mailed or telephoned those who had not turned up at the first invitation and 255 of the remaining students who had filled out the forms (and stated that they would likely vote). We offered them the option of completing the attached survey by e-mail or completing it in a secretary’s office on the college campus at their convenience (within a five-day window). Once again, assignment to treatment was randomly determined (for details concerning the randomization process, see appendix 1). At the end of the first round, we had 82 participants in the control condition and 101 in the treatment condition. Overall, 52 percent of respondents completed the first survey on-line, while the remainder filled out a paper version.

The second round of the survey was administered during the five days prior to the election. All participants in the first round of the survey were emailed the second survey and asked to complete it on-line or on paper (at the same secretary’s office, within a five-day window). The e-mail text differed for those in the treatment and control groups only with regard to the obligation to vote. The deadline for completing the second questionnaire coincided with the close of polls on election day (March 26, 2007). In all, 143 participants completed the questionnaire (all but 6 did so electronically).

All students had to complete and sign, in person, a research consent form (the electronic version was rejected by the DGE) granting the college permission to provide the DGE with their names and addresses so that the DGE could verify that they had voted. Hence, excluding those who failed to fill out the consent form, as well as treatment group members whose voting we were unable confirm,21 the final participation rate was 55 young people in the control group and 66 in the treatment group.22

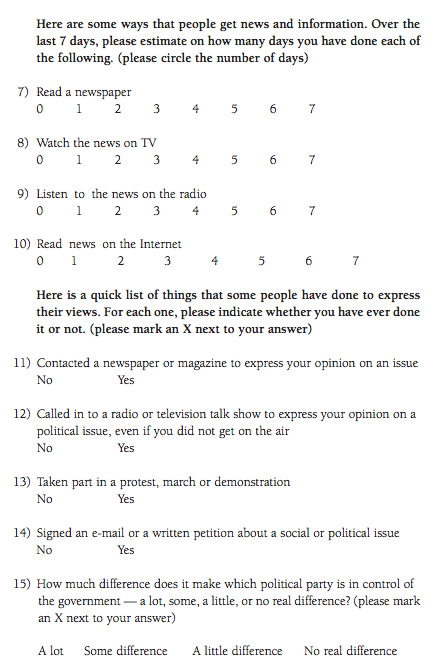

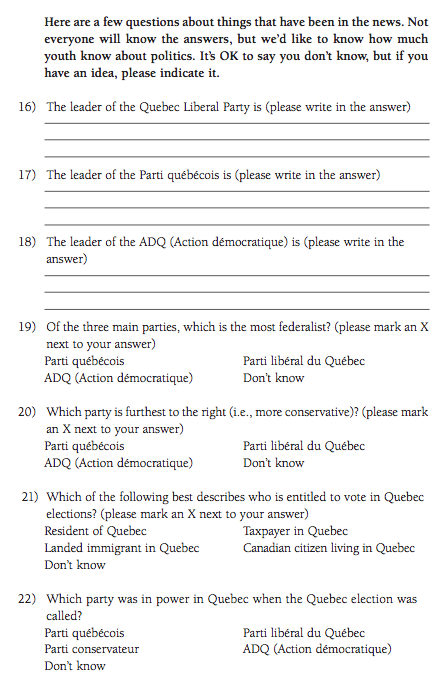

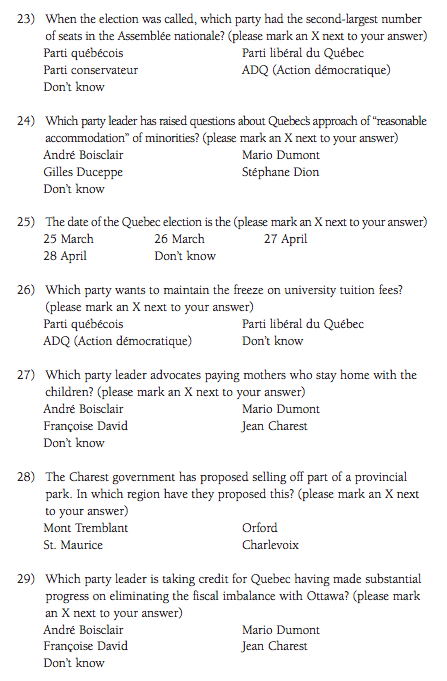

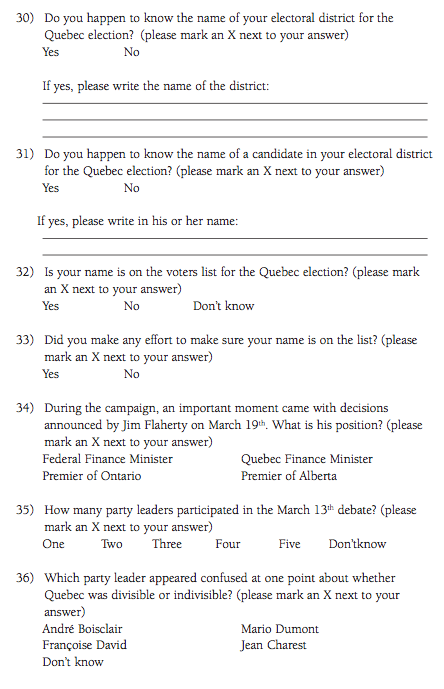

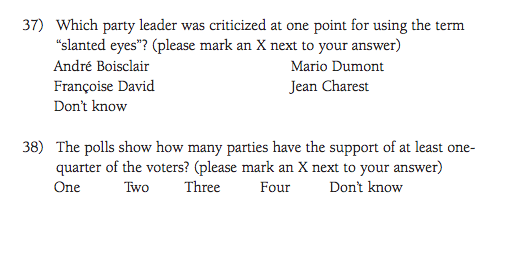

Students who chose to participate in the experiment (either on paper or on-line) were all given the same surveys (the second survey is found in appendix 2). The first survey contained a number of questions about their media usage, their engagement in political discussion, and their attitudes toward politics and political involvement, followed by a set of political knowledge questions. As the overall purpose of the experiment was to determine whether those who have a financial incentive to vote (or a financial disincentive not to vote) pay more attention to politics, we carefully selected a variety of knowledge questions. These ranged from questions about the positions of the different parties on various issues in the campaign (such as whether university tuition should be raised), to questions about political facts (such as which party was in power when the election was called), to questions related to election knowledge (such as what date had been set for the election, and who is eligible to vote). In sum, we included a range of questions designed to identify those with a rudimentary knowledge of politics generally and current Quebec politics specifically.

We did much the same with the second questionnaire; however, we added several political knowledge questions, bringing the total to 23. Of the questions, nine were repeated verbatim from the previous questionnaire, 2 were altered versions of previous questions, and 12 were new (almost all of them closely linked to developments in the campaign). We are confident that the full battery of questions is an appropriate instrument for uncovering any significant knowledge differences between our two groups relevant to electoral participation in this time and place.

The first-order effect of compulsory voting — increased turnout — is quite clear. However, the second-order effects of greater knowledge and engagement are not. We argue that the possible second-order effects of compulsory voting on citizen engagement can be operationalized in the form of three hypotheses:

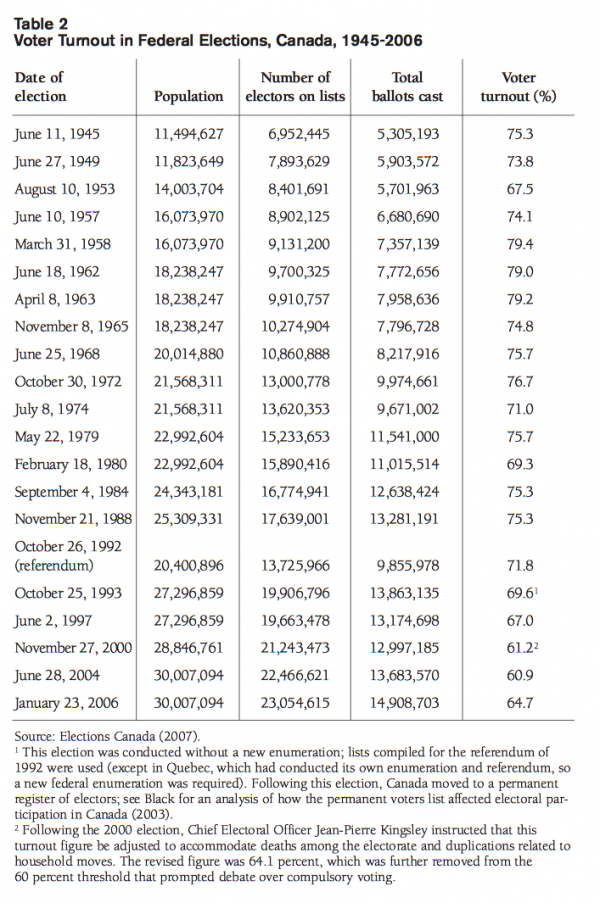

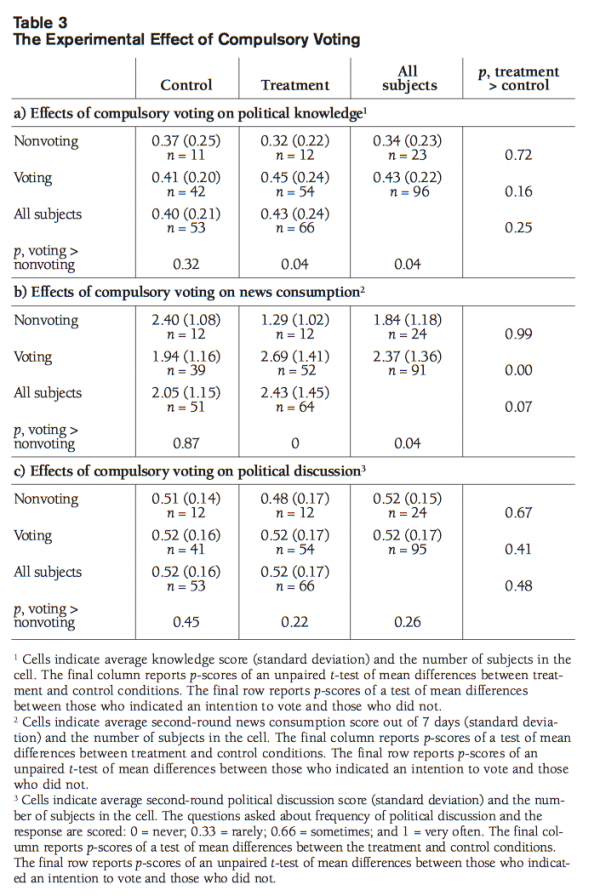

We find little support for these hypotheses in our data. As we found no significant differences between treatment and control conditions in our first-round scores, we limit the analysis to second-round scores. Table 3a) presents comparisons of knowledge scores on the second survey between those in the control and treatment conditions and those who voted in the election and those who did not. Each cell presents a mean for the group in question, its standard deviation and the number of individuals in that group. The final column provides the results of a t-test of mean differences between those in the control and treatment conditions. The final row likewise provides the results of a t-test of mean differences between those who indicated an intention to vote and those who did not. The lower the p-value, the more confident we can be that the difference between our groups does not occur by chance (0.05 is the critical point at which we are sure that the difference is different from 0, 19 times out of 20). As we can see, the overall difference in the second round between groups under treatment and control conditions is not significant. Moreover, when we split the groups into those who voted and those who did not,23 we do not uncover significant treatment effects. Giving (young) voters a financial disincentive to abstain from voting did not increase the amount they learned about politics.24 Rather, our findings suggest that those in both control and treatment were able to answer about 4 out of 10 questions correctly. The only significant difference is between those subjects who intended to vote at the outset of the experiment and those who did not, with the former correctly answering about 1 more question in 10 than the latter.

We next consider the possibility that the treatment students did try to learn more about politics but were unable to do so. We find no evidence that they increased their general engagement with politics through discussion, which could have signalled a greater effort to learn. Rather, all subjects, on average, reported discussing politics somewhere between rarely and sometimes.

Despite the absence of findings on political discussion, when it comes to news consumption, there is an indication that subjects in the treatment condition consumed more news by the end of the campaign than those in the control condition. In table 3b), we see that news consumption seems to increase with treatment — certainly in the voting group (p < 0.00), and probably overall as well (p <= 0.07). It is hard to know how much significance to attribute to this (those in the control condition on average reported consuming all forms of news 2.05 days out of 7, while those in the treatment condition reported consuming all forms of news 2.43 days out of 7).25 This difficulty occurs because we do not know at which point greater media consumption begins to yield knowledge benefits, or at which point it signals a more engaged electorate. In itself, it is consonant with the claims of compulsory-voting advocates, but it creates a new puzzle in that it does not manifest itself in any measurable increase in knowledge.

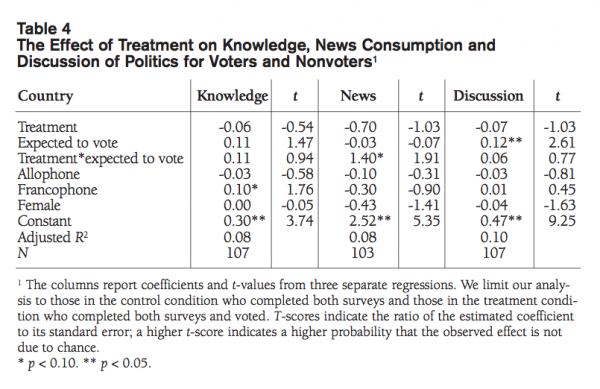

Aside from our news-consumption finding, we did not discover support for the hypothesis that when individuals are financially compelled to vote they become more politically attentive and knowledgeable citizens. But it is possible that this effect is isolated in the group where we would most expect to find it — those who would normally not vote. If compulsory voting does increase attentiveness and knowledge, then we might find the effect among those who did not intend to vote at the outset of the study but were assigned to the treatment and then voted. We test this proposition in table 4. We limit our analysis to those in the control condition who completed both surveys and those in the treatment condition who completed both surveys and voted.26 Our approach is to use a conventional ordinary least squares (OLS) analysis, regressing second-round scores for knowledge, discussion and news consumption on a dummy variable indicating treatment, another indicating whether the subject initially reported that he or she expected to vote (expvoter), and an interaction between these two variables. We also include dummy variables indicating whether a subject is francophone or allophone (with anglophones acting as the comparison group), and whether the subject is female. The following regression equation for political knowledge captures the effect of treatment on initial nonvoters:

Y (knowledge) = a + b1 * treatment + b2 * expvoter + b3 * expvoter * treatment + b4 * allo + b5 * French + b6 * female + e

As we are interested in the effect of treatment (treatment = 1) on nonvoters (voter = 0), we are left with the following equation:

Y (knowledge) = a + b1 * treatment + b4 * allo + b5 * French + b6 * female + e

Accordingly, the specific effect of compulsory voting on knowledge acquisition (or levels of discussion, or news consumption) among nonvoters is captured by the coefficient on treatment.27 This effect is presented in the first row of results in table 4.

We should note that we do not include several other variables that we know are related to political knowledge and engagement (see Fournier 2002). Because we are using a randomly assigned experiment, we can assume that these factors are equally present in our control and treatment conditions. Including them should not theoretically change the estimated effects of the compulsory voting treatment.28 Accordingly, we exclude them and stay with a simpler model.

As table 4 demonstrates, we find a treatment effect on news consumption among those who intended to vote in the first place. Our results suggest that those in the treatment condition who intended to vote consumed all types of news approximately 0.7 days per week more than those who did not intend to vote. However, we can find no effect of the treatment among those who would otherwise be nonvoters — hence we are unable to reject the null hypothesis that compulsory voting does not increase the news consumption of nonvoters. Moreover, on both our knowledge variable and our discussion variable, we cannot find a significant effect of treatment either among those who intended to vote or those who did not. In sum, the data does not give us any good basis for rejecting the null hypothesis: to the extent that our experiment reproduces a compulsory voting context, we find that compulsory voting does not boost political knowledge, discussion about politics and news consumption among young potential voters.

We should note that the number of subjects who filled out a form stating that they did not expect to vote or were uncertain whether they would vote was well worn down by attrition by the end of the second round; only 22 of our 121 subjects fit this category. While this is a small number of subjects, we do also note that the signs of the compulsory voting effects are not even in the expected direction. We do not believe this nonfinding to be a problem of inadequate statistical power.

Before turning to compulsory voting, we must look at two findings from this study that inform other questions currently being examined in political science. First, there has been some reticence about posing political knowledge questions, as they may embarrass the uninformed respondent. At least as far as young people are concerned, this appears to be a non-issue. The matter arose when we found ourselves forced to use on-line surveys, and our initial concern was that some students responding on-line might seek answers to the knowledge questions on the Internet so as not to appear uninformed (and thus skew our findings). This concern proved unwarranted, as we could find no discernible difference in political knowledge scores between the two groups (those who used the Internet and those who completed the questionnaire in person under supervision). The fact that these students didn’t make the extra effort strongly suggests that they did not feel embarrassed by their lack of political knowledge or attentiveness to politics in the media.

Second, the low level of political knowledge and lack of interest in electoral politics among young people in Canada was more than confirmed in this study. In table 3, we can see that at the end of the campaign the average student paid attention to news in the media just over two days a week, resulting in an average political knowledge score of just over 40 percent. When we break down the score question by question, we find that more than half the students were able to identify the party leaders, the party in power, the most federalist party and the date of the election, but only a quarter, on average, got the issue-related questions right — the equivalent of chance.

Turning now to the issue of compulsory voting, it is important to keep in mind that we did not exactly replicate a compulsory voting environment. Economists and psychologists have shown that people are more willing to risk losing money promised to them than money already in their pockets (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). Nevertheless, as recorded in table 1, many compulsory voting systems have weak, poorly enforced sanctions, and the loss of an expected $25, though a relatively small amount, is not a negligible sanction for 18and 19-yearolds. Hence, without claiming that we have recreated the conditions of compulsory voting, we can legitimately state that under the conditions of the experiment there should be some measurable indication of an increase in attentiveness due to some of the same processes as would operate under compulsory voting. Additionally, the experiment does closely replicate the effects of voter incentives, which are sometimes offered as a less-intrusive alternative to sanctions.

Nevertheless, we do not wish to overstate our results, principally because they occur in the context of an experiment with a survey instrument conducted over a nonrandom population. The generalizability or external validity of our inferences may be limited (Shadish, Cook and Campbell 2002), but we have not found anything in the literature to suggest that the effects will be nil among youth but strong among others. The contrary is more likely to be the case, since the literature shows that the turnout effects of compulsory voting are greatest in electoral contests where turnout is lowest and among groups that would otherwise be the most disengaged. If second-order effects exist, we would also expect them to be strongest in this category of voters. Young people generally, and those in Canada particularly, certainly belong in this category.

In stating this, we are not making a case against compulsory voting. There may be good reasons to be concerned about turnout — especially if it reaches a point where abstaining is as legitimate as voting. Furthermore, compulsory voting may have a significant impact on how parties create and target their platforms, how they organize their campaigns, and what communities they are attentive to in terms of resources and policy commitments. As Lijphart has rightly argued, compulsory voting “makes voting participation as equal as possible” (1997, 11).29

Nevertheless, our findings do place the ball in the court of the advocates of compulsory voting — at least, those who suggest that individuals will seek out more information so as to make correct decisions when compelled to vote. Their contention, however plausible, needs to rest on empirical evidence. We were unable to confirm it in our experiment. Our results suggest that though it is a sufficient motivator for getting an uninformed voter to the polls, the desire to avoid relinquishing money is not a sufficient motivator for getting that voter to learn more about politics. This is hardly the end of the story. But advocates of compulsory voting will need to provide a more compelling, empirically based micro-story about how it makes better — or at least better-informed — citizens.

There is the possibility that socialization to active citizenry takes time, though this has never been suggested by those who call for compulsory voting. In fact, according to its supporters, it is the immediacy of the benefits deriving from the act of voting that make compulsion desirable. If information collection is something that occurs over time, then this fact could be used to buttress arguments both for and against compulsory voting, so there are merits to pursuing this question in future research.

We should make one final point about young people’s readiness to take part in the experiment more generally, which has implications for compulsory voting and other measures affecting political participation. After distributing well over 1,000 recruiting forms we had expected to receive an excess of applications, from which we would choose 200 respondents who did not expect to vote. Yet of those eligible to vote who filled out a form, only 20 percent stated that they did not expect to vote or were uncertain whether they would vote. In all likelihood, the nonvoters among those enrolled in the classes from which we recruited were more likely to be absent from school or to be unwilling to indicate their interest in participating. This has direct implications for, to give one example, our reliance on permanent registers of electors that are based on voluntary participation.

We were even unable to get most of the people who completed the form and expressed a willingness to participate to come to a locale within the school they attended regularly. And, despite the fact that we made administrative changes (that is, let subjects complete the forms on-line) and undertook active mobilization exercises (such as repeated e-mails supplemented by telephone calls), we still had a large attrition rate, particularly among the nonvoters. This is particularly significant since, historically, the mechanisms used to increase turnout for Canadian elections — the only ones supported by the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Elections Canada to date — have been administrative changes and mobilization efforts. Clearly, such mechanisms will not be sufficient to activate the next generation of recalcitrant voters (young people for whom instantaneous communication and technological convenience will always be present). This may be good news for supporters of compulsory voting, as it implies that past initiatives may be increasingly ineffective; though it is bad news for the health of Canada’s representative democracy. It would also seem to suggest that voter incentives like those Hicks suggests will fail to overcome lack of interest in participating in the groups he identifies as most at risk (2002, 2006).

When voter turnout in Canada was at approximately 75 percent, Pammett’s research for the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform suggested that “there is a small hard core of perennial non-voters, numbering perhaps five per cent of the population at most” (1991, 34), and that these persons were distinct from the approximately 20 percent who chose not to participate from election to election. British politician Geoff Hoon, a prominent advocate of compulsory voting, refers to the former group as “serial non-voters” (Ballinger 2007, 11). Milner has identified a similar group among the young, which he calls the “political dropouts,” and he has sounded the alarm that their numbers may be increasing (2005). This group does, in fact, appear to be growing; and it seems likely to include a higher proportion of males than females.

Overall, then, the future does not look bright for voter participation in Canada as this next group of youths enters the electoral pool. If, as seems to be the case, disengagement and lack of interest are becoming the rule and not the exception, then there is good reason to expect that turnout will not return to previous levels — and it may decline even further. Compulsory voting may be one solution, but in this paper we have raised a number of questions surrounding it. Much more work needs to be done on how information related to voting is obtained and processed by members of society who normally do not vote. Specifically, research is needed on whether information collection alters over time with repeated voting. Additionally, many of the other dimensions of this debate should be more deeply examined, such as how parties respond to greater numbers of voters when mobilization is no longer so central to their electoral strategies. The debate over voter engagement and participation is just beginning in Canada, and it can only benefit from more empirical research. We have merely begun to scratch the surface.

Ackaert, Johan, Patrick Dumont, and Lieven de Winter. 2007. “Compulsory Voting and Electoral Turnout: Drawing Lessons from the Belgian Case.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research Joint Sessions workshop “Compulsory Voting: Principles and Practice,” May 7-12, Helsinki.

Arizona Secretary of State. 2006. State of Arizona Official Canvass: 2006 General Election. Accessed October 30, 2007. https://www.azsos.gov/election/2006/ General/Canvass2006GE.pdf

Bakvis, Herman, ed. 1991. Voter Turnout in Canada. Vol. 15 of Research for the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Ballinger, Chris. 2007. “Compulsory Voting: Palliative Care for Democracy in the UK?” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research Joint Sessions workshop “Compulsory Voting: Principles and Practice,” May 7-12, Helsinki.

Bennett, Scott. 2005. Compulsory Voting in Australian National Elections. Parliament of Australia, Department of Parliamentary Services Research Brief 6, 2005-06, October 31. Canberra: Department of the Parliamentary Library. Accessed October 25, 2007. https://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/rb/ 2005-06/06rb06.pdf

Bilodeau, Antoine, and AndreÌ Blais. 2005. “Le Vote obligatoire exerce-t-il un effet de socialisation politique?” Paper presented at the International Colloquium on Compulsory Voting, Institut d’EÌtudes Politiques de Lille, October 20-21, Lille.

Black, Jerome H. 2003. “From Enumeration to the National Register of Electors: An Account and an Evaluation.” IRPP Choices 9 (7).

Blais, AndreÌ. 2006. “What Affects Voter Turnout?” Annual Review of Political Science 9:111-25.

———. 2000. To Vote or Not to Vote: The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice. Pittsburgh: Uiniversity of Pittsburgh Press.

Blais, AndreÌ, and Kees Aarts. 2006. “Electoral Systems and Turnout.” Acta Politica 41 (2): 180-96.

Blais, AndreÌ, and Kenneth Carty. 1990. “Does Proportional Representation Foster Voter Turnout?” European Journal of Political Research 18:167-81.

Blais, AndreÌ, and Agnieska Dobrzynska. 1998. “Turnout in Electoral Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 33:239-61.

Blais, AndreÌ, and Elisabeth Gidengil. 1991. Making Representative Democracy Work: The Views of Canadians. Vol. 4 of Research for the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Blais, AndreÌ, Elizabeth Gidengil, Richard Nadeau, and Neil Nevitte. 2002. Anatomy of a Liberal Victory: Making Sense of the Vote in the 2000 Canadian Election. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Butt, Emma, Erin Prisner, James R. Robertson, Michael Rowland, Tim Schobert, and Sebastian Spano. 2006. Canada’s Electoral Process: Frequently Asked Questions. Ottawa: Library of Parliament. Accessed October 28, 2007. https://www.parl.gc.ca/information/library/ PRBpubs/prb0546-e.htm

Citrin, Jack, Eric Schickler, and John Sides. 2003. “What If Everyone Voted? Simulating the Impact of Increased Turnout in Senate Elections.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (1): 75-90.

Courtney, John C. 2004. Elections. Canadian Democratic Audit Series. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Czesnik, Mikolaj. 2007. “Is Compulsory Voting a Remedy? Evidence from the 2001 Polish Parliamentary Elections.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research joint sessions workshop “Compulsory Voting: Principles and Practice. May 7-12, Helsinki.

Eagles, Munroe. 1996. “The Franchise and Political Participation in Canada.” In Canadian Parties in Transition, edited by A. Brian Tanguay and Alain-G. Gagnon. Scarborough, ON: Nelson Canada.

Elections Canada. 2007. Voter Turnout at Federal Elections and Referendums, 1867- 2006. Ottawa: Elections Canada. Accessed June 11, 2007. https://www.elections.ca/content.asp? section=pas&document=turnout&lang= e&textonly=false

Ellis, Andrew, Maria Gratschew, Jon H. Pammett, and Erin Thiessen. 2006. Engaging the Electorate: Initiatives to Promote Voter Turnout from around the World. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA).

Engelen, Bart. 2007. “Why Compulsory Voting Can Enhance Democracy.” Acta Politica 17:23-39.

Engelen, Bart, and Marc Hooghe. 2007. “Compulsory Voting and Its Effects on Political Participation, Interest and Efficacy.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research joint sessions workshop “Compulsory Voting: Principles and Practice,” May 7-12, Helsinki.

Fournier, Patrick. 2002. “The Uninformed Canadian Voter.” In Citizen Politics: Research and Theory in Canadian Political Behaviour, edited by Joanna Everitt and Brenda O’Neill. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Franklin, Mark N. 1996. “Electoral Participation.” In Comparing Democracies: Elections and Voting in Global Perspective Since 1945, edited by Lawrence LeDuc, Richard G. Niemi, and Pippa Norris. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2004. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gallego Dobon, Aina, and Guillem Rico. 2007. “Assessing the Capacity of Compulsory Voting to Reduce Turnout Inequality.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research Joint Sessions workshop “Compulsory Voting: Principles and Practice,” May 7-12, Helsinki.

Gerber, Alan S., Donald P. Green, and Ron Shachar. 2003. “Voting May Be Habit Forming: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (3): 540-50.

Gratschew, Maria. 2001. “Compulsory Voting.” Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA). Accessed October 24, 2007. www.idea.int/vt/compulsory_voting.cfm

Green, Donald P., and Ron Shachar. 2000. “Habit-Formation and Political Behavior: Evidence of Consuetude in Voter Turnout.” British Journal of Political Science 30:561-73.

Hansen, Mogens Herman. 1999. The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes. London: Bristol Classical Press.

Harb, Mac. 2005. “The Case for Mandatory Voting in Canada.” Canadian Parliamentary Review 28 (2): 4-6.

Hicks, Bruce M. 2002. “The Voters’ Tax Credit.” Policy Options 23 (4): 63-68. Montreal: IRPP. ———. 2006. “Are Marginalized Communities

Disenfranchised? Voter Turnout and Representation in Post-Merger Toronto.” IRPP Working Paper Series 2006-03. Montreal: IRPP.

Hill, Lisa. 2000. “Compulsory Voting, Political Shyness and Welfare Outcomes.” Journal of Sociology 36 (1): 30-49.

Hirczy, Wolfgang. 1994. “The Impact of Mandatory Voting Laws on Turnout: A Quasi-experimental Approach.” Electoral Studies 13:64-76.

Hooghe, Marc, and Koen Pelleriaux. 1998. “Compulsory Voting in Belgium: An Application of the Lijphart Thesis.” Electoral Studies 17 (4): 419-24.

Howe, Paul, and David Northrup. 2000. “Strengthening Canadian Democracy: The Views of Canadians.” IRPP Policy Matters 1 (5).

Jackman, Robert W. 1987. “Political Institutions and Voter Turnout in Industrial Democracies.” American Political Science Review 81 (2): 405-23.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk.” Econometrica XLVII:263-91.

Keaney, Emily, and Ben Rogers. 2006. A Citizen’s Duty: Voter Inequality and the Case for Compulsory Turnout. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Lever, Annabelle. 2007. “The Case for Compulsory Voting: A Critical Perspective.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research Joint Sessions workshop “Compulsory Voting: Principles and Practice,” May 7-12, Helsinki.

Linder, Wolf. Swiss Democracy: Possible Solutions to Conflict in Multicultural Societies New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Lijphart, Arend. 1996. “Compulsory Voting Is the Best Way to Keep Democracy Strong.” Chronicle of Higher Education 43 (8): B3-4.

———. 1997. “Unequal Participation: Democracy’s Unresolved Dilemma.” American Political Science Review 91 (1): 1-14.

Malkopoulou, Anthoulap. 2007. “Compulsory Voting in Greece: A History of Concepts in Motion.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research Joint Sessions workshop “Compulsory Voting: Principles and Practice,” May 7-12, Helsinki.

Martinez, Michael D., and Jeff Gill. 2006. “Does Turnout Decline Matter?: Electoral Turnout and Partisan Choice in the 1997 Canadian Federal Election.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 39 (2): 343-62.

Mavrogordatos, George Th. 2003. “The Classical Model Revisited: Athenian Democracy in Practice.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research Joint Sessions workshop “Bringing Citizens Back In: Participatory Democracy and Political Participation,” March 28-April 2, Edinburgh.

McAllister, Ian, and Malcolm Mackerras. 1998. Australian Political Facts. Oxford: Macmillan Education.

Milner, Henry. 2005. “Are Young Canadians Becoming Political Dropouts? A Comparative Perspective.” IRPP Choices 11 (3).

O’Neil, Brenda. 2001. “Generational Patterns in the Political Opinions and Behaviour of Canadians: Separating the Wheat from the Chaff.” IRPP Policy Matters 2 (5).

Pal, Michael, and Sujit Choudhry. 2007. “Is Every Ballot Equal? Visible-Minority Vote Dilution in Canada.” IRPP Choices 13 (1).

Pammett, Jon. 1991. Voter Turnout in Canada. Vol. 15 of Research for the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Print, Murray. 2006. “Socializing Young Australians to Participate in Compulsory Voting.” Paper presented at the World Congress of the International Political Science Association, July 2006, Fukuoka, Japan.

Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing (Lortie Commission). 1991. Report of the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing. 4 vols. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Rubenson, Daniel, AndreÌ Blais, Patrick Fournier, Elisabeth Gidengil, and Neil Nevitte. 2007. “Does Low Turnout Matter? Evidence from the 2000 Canadian General Election.” Electoral Studies 26 (3): 589-97.

Selb, Peter, and Romain Lachat. 2007. “‘The More, the Better?’ Counterfactual Evidence on the Effect of Compulsory Voting on the Consistency of Party Choice.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research Joint Sessions workshop “Compulsory Voting: Principles and Practice,” May 7-12, Helsinki.

Shadish, William R., Thomas D. Cook, and Donald T. Campbell. 2002. Experimental and Quasi-experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

“Voting Incentives to Be Introduced.” 2006. Korea.net: Gateway to Korea. Accessed October 24, 2007. https://www.korea.net/ Search/SearchAll.asp

Watson, Tom, and Mark Tami. 2000. Votes for All: Compulsory Participation in Elections. Second Term Thinking Series 50. London: Fabian Society.

———. 2001. “Abolishing the Democratic Deficit: Time for Compulsory Voting?” In The People Have Spoken. UK Elections: Who Votes and Who Doesn’t, edited by Virginia Gibbons. London: Hansard Society.

Wattenberg, Martin P. 2007. Is Voting for Young People? New York: Pearson.

Weller, Patrick, and Jenny Fleming. 2003. “The Commonwealth.” In Australian Government and Politics: The Commonwealth, the States and the Territories, edited by Jeremy Moon and Campbell Sharman. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

The randomization of participants proceeded in three steps. First, we identified all subjects (119) who indicated on the initial recruitment form that they did not expect to vote or were unsure whether they would vote. Using a random number generator, we assigned each of these subjects a number and then ranked them according to this number. The top half were assigned to the treatment condition and the bottom half to the control condition. Second, we assigned a random number to all potential participants who indicated that they were likely to vote. We selected the top 86 of these participants. The top half of the selected group was assigned to the treatment condition and the bottom half to the control condition. Third, to expand our sample using an on-line survey, we invited the remaining 255 eligible participants to take part in the study. We assigned subjects to treatment and control prior to contact using the method of random number assignment and then ranking them as we have described. However, in this instance, 70 percent were assigned to treatment (where attrition could be expected to be high) and the remaining 30 percent to control.

We have checked our randomization procedure across several key variables, and, for the most part, we found no significant differences between conditions in the first round, suggesting that our randomization worked. In each test of balance, χ2 indicates the score of a chi-square test of the relationship between treatment and another variable. The p-score indicates the probability that the relationship observed is due to chance. Lower χ2 and higher p-scores indicate that the relationship is due to chance and that treatment is thus uncorrelated with that variable. Our treatment was balanced according to gender (χ2 = 0.82, p = 0.37), with female participants making up 73 percent of the treatment group and 67 percent of the control group. (Women students are considerably overrepresented in the pre-university social science program; and, as noted, attrition was lower among the female students.) Internet usage was also insignificantly related to treatment assignment (χ2 = 5.84, p = 0.44). Most importantly, there was no difference in the average knowledge scores in the first wave of the survey between the two groups (χ2 = 7.06, p = 0.63). The same is true for political discussion and media news consumption. Both the control and the treatment groups showed remarkably low levels of knowledge about Quebec politics, with more than half of the respondents in each group getting 3 or fewer questions out of 11 correct. There is also no difference in knowledge when we control for the likelihood of voting. There is, however, a language difference: those who speak French at home as their first language know significantly more about politics than those who do not.30 We should note, however, that language is unrelated to randomization.