The thesis of Global Futures for Canada’s Global Cities is that the globalization and the information age have led to the economic, political and even democratic ascendancy of global city regions (GCRs). Yet there is sometimes a wide gulf between the potential for these GCRs and their on-the-ground reality. This is especially the case in Canada, where GCRs are fiscally weak and jurisdictionally constitutionless. Accordingly, the analysis focuses on a variety of alternative structures and processes that would allow our GCRs to reach their potential with respect to the knowledge-based economy.

Part of what underpins the GCRs’ role as the dynamic motors that drive innovation, growth and trade is that they hold the dense concentrations of human capital that increasingly are required by the knowledge-based economy (KBE). This leads to a virtuous circle by which GCRs can undertake policies and actions that make them attractive to human capital, which, in turn, allows them to become magnets for attracting KBE enterprises. Furthermore, evidence suggests that privileging Canada’s “hub cities” will propel them and their hinterlands forward economically.

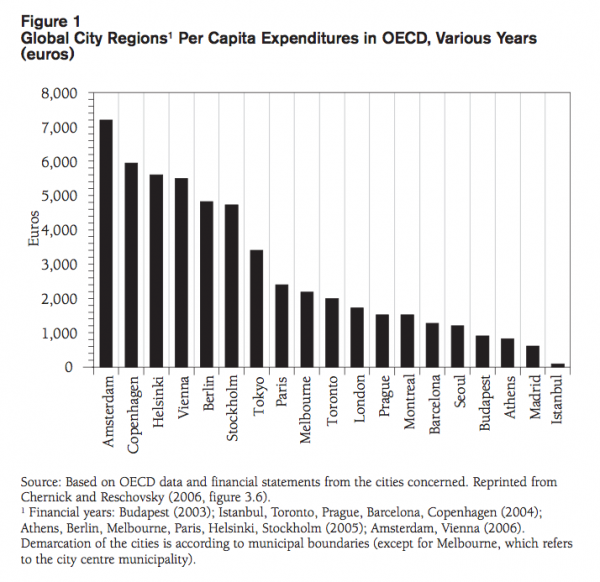

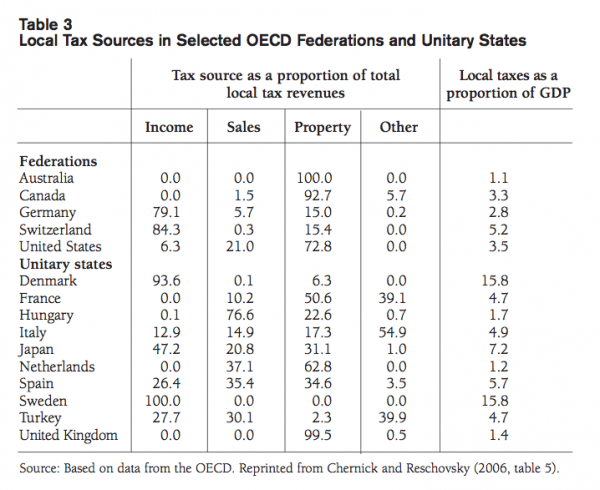

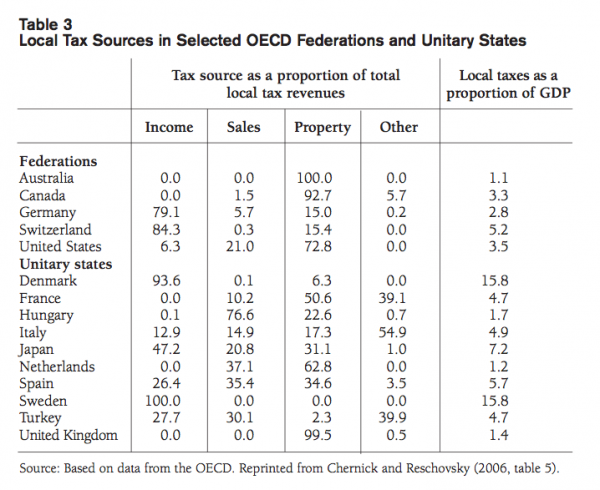

The international evidence on our GCRs’ fiscal weakness is striking. Cities like Stockholm, Berlin, Vienna and Helsinki spend twice as much and Copenhagen and Amsterdam three times as much per capita as Toronto does. This suggests that there is ample scope for decentralization in Canada to go beyond the devolution of money and power from Ottawa to the provinces. Not surprisingly, part of the problem here is that access to tax revenues in Canada’s GCRs (and those in the English-speaking world generally) tends to be limited to property taxes, whereas continental European cities often have access to a range of broad-based taxes. For example, Swedish cities are financed from income taxes and have revenues, in aggregate, of nearly 16 percent of GDP. In contrast, the political limit to property-tax financing is in the range of 3 percent of GDP. This implies that unless our GCRs obtain access to broad-based tax sources (or a share thereof), they will never achieve their KBE potential.

While American GCRs also rely on property taxes for about three-quarters of their tax revenues (the comparable average for Canada is over 90 percent), many US cities have access to income and sales taxes. Not only do US cities have access to many more own-source tax revenues, but they also share in a large number of state taxes. For example, 94 percent of Edmonton’s own-source revenues come from various taxes on property, whereas Denver’s property taxes account for only one-fifth of its own-source tax revenues, with nearly two-thirds coming from a general retail sales tax. Where the implications of these differences are most significant is in the area of capital spending. Over the 1990-2000 period, Denver’s per capita spending was nearly double that of Calgary. Given that Canadians’ living standards will to a large degree depend on how our GCRs fare relative to American GCRs, these are sobering figures indeed.

There is a variety of ways that the GCRs can become more fully and formally integrated into the operations of Canadian political and fiscal federalism. The most promising avenue would be to rework federal-municipal relations, following Ottawa’s recent initiatives in the municipal arena such as sharing the federal gas tax and exempting cities from the GST. But the GCRs maintain that federal gas-tax sharing amounts to an equalization program disbursed by the large cities to the smaller ones. The GCRs want access to a broad-based tax available on a derivation principle. Since the GCRs are the creatures of their respective provinces, the appropriate way to achieve this would be to rework provincial-municipal relations. Just as the provinces piggyback on the federally collected personal income tax (PIT), so cities could piggyback on the provincial portion of the PIT.

Propelled by the momentum arising from the principle of subsidiarity and the dictates of the knowledge-based economy (KBE), global city regions (GCRs) are increasingly hailed as the new dynamic motors of the information era. In Canada, the cities that would qualify as GCRs are fiscally weak in the international context and jurisdictionally constitutionless in the Canadian context. The role of this paper1 is to document the extent of the gulf between the global potential of GCRs and their Canadian reality, and to draw implications and conclusions from them.

Accordingly, I begin by focusing on the range of factors and forces flowing from the knowledge-based era that underpin the economic and political ascendancy of GCRs. Then I compare Canadian and international cities in terms, first, of their expenditures and, second, of their access to broad-based taxation. To anticipate the evidence, not only do Canadian cities fare poorly against their European counterparts, but they also come out decidedly second against American cities in terms of their fiscal autonomy.

In the remainder of the paper I address a range of options for bridging this potential-reality gap. In terms of the contribution that reworking federal-municipal relations could make, I look in turn at Ottawa’s gas-tax sharing; at removing the blatant discrimination in the qualification for employment insurance (EI) benefits in selected GCRs; at the proposals emanating from the 2006 External Advisory Committee on Cities and Communities; and finally, at the implications of the fiscal imbalance for increasing the revenue flexibility of cities.

While cities would no doubt welcome greater involvement and cooperation with Ottawa in terms of both powers and revenue, the underlying reality is that cities are, constitutionally, creatures of the provinces. It is the creative reworking of provincial-municipal relations that ultimately holds the most promise for enabling Canada’s cities to achieve their potential in the KBE. Following these lines, the analysis focuses on the Greater Toronto Charter as a (probably extreme) model of a set of exclusive and concurrent powers that would privilege GCRs. If one were to imagine what sort of event would trigger this power shift, it would be a province, say Alberta, deciding to share personal income taxes with, say, Edmonton and Calgary, and perhaps with other cities on an opt-in basis. While we await this and other decisive tipping points to privilege Canada’s global city regions, there are several smaller, but nonetheless significant, milestones in the direction of empowering Canada’s GCRs, which I will highlight.

The new global order — globalization and the information revolution, which together will be referred to as the knowledge-based economy, or KBE — is leading to the economic, political and even democratic ascendance of Canada’s global city regions, or GCRs. In terms of the globalization component of the KBE, the GCRs, in their roles as dynamic economic engines and export platforms, are spearheading the integration of their provinces and regions into NAFTA economic space. This secures the GCRs’ pride of place in conventional economic geography, or in what Manuel Castells (2001) refers to as the “the space of places.”

The knowledge-information-revolution component of the KBE adds an entirely new dimension to the significance of GCRs. Knowledge and human capital are increasingly important drivers of well-being and are at the cutting edge of competitiveness. And, because it is in the GCRs that one finds the requisite dense concentrations of human capital — information technology, research and development, high-value-added services, and so on — GCRs can become the coordinating and integrating networks in their regional economies, and the national nodes in the international networks that drive growth, trade and innovation. Thus, GCRs are also the key players in this new economic geography — Castells’ “space of flows.”

Underlying both the KBE and the new role of GCRs is the emergence of individuals as the principal beneficiaries of the information revolution, thanks in large measure to the democratization of technology and the rise of the Internet. This empowerment of individuals and their virtually unlimited access to information breathes new life into the principle of subsidiarity. The result will be to “push down to the local level and to individuals more power and resources than ever before” (Friedman 1999, 293). To be sure, subsidiarity also has a “passing upward” component, where the appropriate locus for regulating highly mobile activity is rising in the jurisdictional hierarchy, as exemplified in the creation of the euro. Glocalization is a convenient term that captures both the “passing upward” and “passing downward” components of the KBE, a duality anticipated over a decade ago by Horsman and Marshall, when they noted that “citizens…will seek political solutions, and democratic accountability, at ever more local levels as the world economy moves toward an ever greater level of integration” (1994, xv). This is an essential component of the argument that the GCRs will also experience a democratic ascendency.

In a recent paper, Vander Ploeg also focuses on the transition of GCRs, or big cities, into their new role as international “gateways”:

It is important to understand that Canada’s traditional comparative economic advantage has always revolved around ready access to an abundance of natural resources, an ample supply of, and reasonable costs for, medium-skilled labour, relatively cheap sources of energy, and proximity to the US market. These conditions favoured the building of a resource and manufacturing-based economy. But this is giving way — significant manufacturing activity has gone offshore and most of it will not soon return. As a result, “higher-ordered” producer services and activities that spin around knowledge and skills (e.g., idea generation and knowledge transfer, product engineering and design, prototype construction and testing), as well as the service industries that support those activities (e.g., financing, marketing, advertising), are becoming much more important…Increasingly, the opportunities for our future economic success are tying in with the new global and knowledge-based information economy. In this economy, comparative advantage shifts to the big cities, which are home to the young, educated, and highly skilled workers demanded by this type of economy, as well as the capital, investment, and entrepreneurs that drive it. Big cities are not only the locus of research, development, and innovation, they also serve as the gateways to global trade. (2005, 5)

“Gateway” is an apt term indeed, since it can encompass both the “space-of-places” and the “space-of-flows” roles of CGRs.

Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class (2002) has taken the primacy of human capital one step further: just as the concentration of mineral deposits will attract mining companies, so concentrations of talented and creative people attract will knowledge-intensive companies. And the cities that come out on top will be those that fare best in terms of what Florida refers to as the three “Ts”: technology (as measured by innovation and high-tech industry concentration); talent (as measured by the number of people in creative occupations); and tolerance (as measured by the amenities and opportunities available for every possible lifestyle). Florida labels this the “creative capital” theory of economic growth. Research undertaken by Gertler et al. (2002) indicates that Canada’s GCRs rank very high in North America in terms of tolerance, but lag in the two other “Ts.” This is consistent with evidence produced by Martin and Milway (2003): that the gap between Ontario’s per capita GDP and that of the average US state is an urban gap. They go on to argue that closing this gap requires addressing four factors: attitudes toward the KBE, manifested, for example, in lower university enrolment in Ontario; investment (private investment to enhance productivity and public investment to increase education and human capital); incentives/motivation (higher tax rates); and fiscal and governance structures. While some of these factors are beyond the jurisdiction of cities (e.g., marginal income tax rates), others are not. With appropriate governance structures, not only can cities create environments that will score high on the tolerance scale, they can also go a considerable way toward framing policies that allow the three “Ts” to interact and create a learning environment. In other words, given the requisite instruments, cities can enhance their own ability to be attractive to the clustering of both human and physical/financial capital.

This idea is a variant of one expressed in a somewhat earlier literature, which stressed that competitiveness and social cohesion are both important in determining a region’s success — or that, as Pastor says, “doing good and doing well can go hand in hand.” Pastor goes on to note that “the Silicon Valley Leadership Group has lobbied for higher (not lower) taxes in order to fund public transportation, coalesced with community groups to lobby for affordable housing, and generally maintained a positive relationship with the public sector.” He quotes the Alliance for Regional Stewardship as saying that such stewardship must “work at the creative intersection of the inter-related issues of economic development, social equity, community liveability and participatory governance by lending initiative and building partnerships with other sectors and organizations” (2006, 294). It is difficult to imagine that this horizontal coordination could occur anywhere but at the GCR/city level.

Finally (but hardly exhaustively), Brender and Lefebvre, in Canada’s Hub Cities: A Driving Force of the National Economy, present some evidence of the increased importance of what they refer to as “hub cities” (2006). These are the eight large cities — Vancouver, Edmonton and Calgary, Regina and Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Toronto, and Montreal — that function as the economic drivers of their provinces, and a ninth city, Halifax, that functions as a hub city for the Atlantic provinces. They conclude that Canada’s hub cities are not receiving the investment they need to fulfill their roles as the economic drivers of regional and national prosperity. This conclusion follows from the principal finding of the study, namely that the “growth in a province’s or region’s hub city… drives an even faster rate of growth in smaller communities within the same province or region” (2006, i). Moreover, the evidence suggests that this convergence appears to be contained within the regions: there is no evidence of convergence across the hub cities, nor is there evidence that focusing only on Vancouver, Montreal and Toronto would produce a boom across all provinces. The principal policy implication is that Canada needs a strategically focused big-cities or hub-cities agenda. In the words of Brender and Lefebvre:

[A]llotting strategic funding to all of Canada’s hub cities based on their needs would indeed produce a nationwide “boost” for them and for smaller communities alike. Such a strategic needs-based approach to hub city investment would also yield a bigger economic impact than the per capita funding approach used in the federal government’s 2005 budget, which allocated a gas tax rebate to Canadian communities on a uniform per capita basis. (2006, ii)

The message so far is two-fold. First, Canada’s GCRs hold the promise for success in the KBE. Richard Harris captured this when he asserted that the collective future of Canadians depends on how our large cities will perform relative to their US counterparts (2003, 50). Second, our GCRs are falling short of this promise.

As backdrop to the reworking of the division of money and powers in the federation — so as to enable the GCRs to achieve their potential as the dynamic motors of the KBE — it is instructive to compare the existing revenue and expenditure powers of Canada’s GCRs with those of international GCRs.

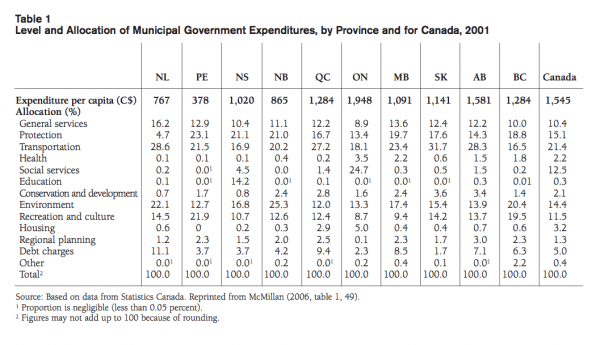

If we first look at the expenditures of Canada’s municipal governments, we see that they vary considerably across provinces (table 1). In 2001, local governments in Ontario led the pack (with nearly $2,000 per capita), Alberta’s were in second place (with $1,581), and PEI’s were in last place (with $378). A major reason for the higher spending of Ontario municipalities is that, unlike local governments in other provinces, they are responsible for a significant number of social services (24.7 percent of total expenditures for Ontario’s local governments, with Nova Scotia’s in second place, but well behind, at 4.5 percent). Nova Scotia’s local governments lead in terms of educational expenditure, with 14.2 percent of their expenditures in this area, compared with a maximum of 1 percent for the other provinces. Hence, in the international comparisons that follow, readers should keep in mind that while there are differences in expenditure allocations internationally, there are also very significant differences across Canadian cities.

Figure 1 presents expenditures per capita (in euros) for selected OECD GCRs. These data capture “overall expenditure assignments” in these metropolitan areas. Toronto (with spending of roughly €2,000) and Montreal (with roughly €1,500) are well down the list, with Amsterdam topping the rankings with over €7,000 per capita.

The first point to note is that the majority of the GCRs that spend more euros per capita than Toronto are located in unitary states. Perhaps this is not surprising, because if unitary states like Holland, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Japan and France (all of whose cities rank above Toronto) want to devolve responsibilities to a lower level of government, by default this has to be the local level. This raises important questions with respect to Canada’s GCRs and its cities in general: Why does decentralization in Canada appear to stop with the provinces? Are we truncating the operation of the principle of subsidiarity at the provincial level, when experience elsewhere suggests we could bring the provision of goods and services much “closer to the people?” And if so, why? I shall attempt to address these questions below.

Berlin and Vienna are the only two cities in federal states that have per capita expenditures above Toronto’s. In large measure, Germany and Austria fall into the “administrative federalism” camp, which means that legislation promulgated by the upper levels of government is largely implemented (administered) by lower levels. Consider the German federation, as described in the following excerpt from an excellent survey of Germany by Hrbek and Bodenbender:

The wide range of tasks and duties of municipalities reflects a basic feature of intergovernmental relations in Germany. Whereas legislation is primarily the responsibility of the federal level, the sub-national level is responsible for administrative tasks, including the implementations of federal laws and policies…The Länder have mostly delegated administrative functions to the local level… Altogether, between 70 and 80 percent of all legal provisions of the Federation and the Länder are implemented by the local authorities. (169-70, 2007)

Indeed, the authors go on to note that “the federal level is constitutionally denied the right to have administrative offices of its own at the sub-Länder level, except for a constitutionally minimal number of functions such as customs and border police.”

In terms of specific functions assigned to the local level, the authors elaborate as follows:

[The provision of public goods and services by the local authorities] includes the following areas: museums, theatres, schools, sports and recreation grounds, hospitals, construction, habitation, sewage, waste disposal, electricity, gas and water support, public transportation, promotion of trade and business, measures related to immigration policy and social assistance . . . Local authorities are the major providers of public utilities. Over 60 percent of all public investments are carried out by the local authorities…In 2002, the Federal had 490,000 civil servants (this includes the armed forces) and the Länder 2.1 million employees (this includes personnel in schools and tertiary education). The municipalities and counties had a workforce of 1.4 million which accounted for almost 35 percent of the bureaucracy. (170-71)

Finally, Hrbek and Bodenbender note that of the 300 European Union (EU) directives relating to the internal EU market, approximately 120 are to be implemented by the German municipalities. This is glocalization at its finest: powers are passed upward to the EU from Berlin (i.e., from federal Germany) and then downward to the German local authorities for implementation.

By way of an intriguing aside, students of Canadian federalism often argue that Canada is the most decentralized federation in the world. From the perspective of the most commonly cited aspect of this issue — the percentage of overall expenditures and own-source revenues that is collected and/or allocated at the subnational level — this is probably correct. However, the Germans could mount a persuasive, two-pronged counterargument in claiming the opposite. First, the länder have a veto (via the Bundesrat) over all federal legislation touching upon their roles and responsibilities, whereas Canada’s provinces have no role at all in our central governing institutions. In this (admittedly narrow) sense, Canada is arguably the most centralized modern federation in the world. Second, the German federation embodies the principle of subsidiarity to a much greater degree than does Canada.

This caveat aside, given the large disparities in per capita spending across the GCRs shown in figure 1, it follows that the tax assignments must also vary substantially. To this I now turn.

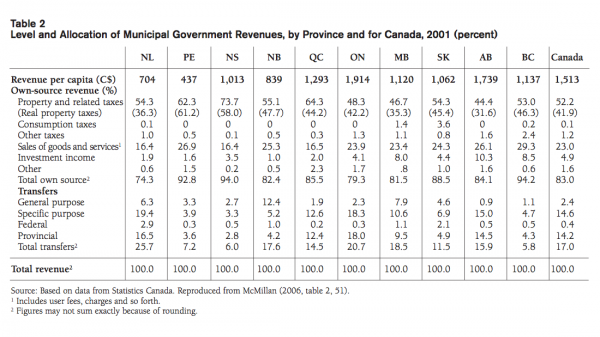

Table 2 shows the level and allocation of municipal revenues across the various provinces. Property-associated taxes account, on average, for 52.2 percent of per capita revenues for all municipalities (last column). This varies from a low of 44.4 percent in Alberta to 73.7 percent in Nova Scotia. In Canada as a whole, revenue from sales of goods and services represents just under one-quarter of municipal revenues, while transfers from other levels of government account for 17 percent, the overwhelming amount of which are (1) from the provinces and (2) in the form of specific-purpose transfers. (More detailed data relating to taxation sources for selected Canadian cities will be presented later.)

Turning now to the international context, table 3 presents data on the range of taxes available to local authorities in selected OECD countries. The first 5 countries are federations, while the remaining 10 are unitary states. The differences across the federations are quite astounding. Local authorities in Australia and Canada have no access to income taxes and are almost wholly reliant on property taxes (100 percent in Australia). In sharp contrast, local authorities in Germany and Switzerland obtain upwards of four-fifths of their tax revenues from income taxes, and only 15 percent from property taxes. The United States is somewhere in between these two extremes, but closer to the Canadian/Australian model. In the unitary states’ GCRs, income taxes are the dominant tax source in Denmark and Sweden, accounting for just over 15 percent of GDP in both countries. Indeed, as Lotz (2006, chap. 7) notes, one can make a convincing case that there is a “Nordic model” of local government financing (and also of decentralization in general). Defining Nordic as encompassing Norway and Finland in addition to Sweden and Denmark, Lotz notes that income taxes account, on average, for 91 percent of local taxes, with property taxes accounting for 7 percent and “other taxes” accounting for the remaining 2 percent (239). There are seven other countries, all unitary states, whose local authorities rely to varying degrees on sales taxes — with Hungary (76.6 percent) and France (10.2 percent) at the extremes. Finally, the United Kingdom, where property taxes account for 99.5 percent of its tax sources, falls into the “Anglo” camp (Australia, Canada and the United States).

Focusing only on the five federations, Australia, Canada and the United States are English common-law countries, whereas Switzerland and Germany are underpinned by civil law. It is well known that common-law regimes tend to be associated with individualist capitalism and tend to have equity markets as the principal source of corporate finance, whereas civil-law regimes tend to be associated with communitarian capitalism and credit-based, bank-dominated financing for corporations (Zysman 1983, tables 6.1 and 6.2). Looking at the sources of revenue of Canadian provinces (see table 2), this comparison might be extended to link common-law regimes with reliance on property tax, and civil-law regimes with reliance on income tax. (As noted above, the common-law characteristics also extend to the United Kingdom and, although it is not included in table 3, to New Zealand as well.) The linkage between local governments and property taxes makes considerable sense since (1) property taxes are an ideal revenue base for local governments because they are immobile, and (2) the traditional role of local governments (in Canada at least) was to provide property-based services — fire protection, policing, water, and sewage, garbage collection, lighting, and the like — and what better source of revenue for this than property taxes? Nevertheless, there is a limit to the amount of revenues that can be raised through property taxes. Lotz (2006, 238) notes that, according to the OECD, over the medium term, no country has revenues from property taxes in excess of 3 percent of GDP. Canada is arguably at this limit now. (This is especially true of Ontario, which is in the throes of a property-tax revolt.) What this means is that were reliance on own-source revenues at the local level in Canada to increase, this increase would presumably have to come from tax sources other than property tax. Phrased differently, even if Sweden (Stockholm) were intent on resorting to property taxation at the local level, it would still have to get access to a wider range of tax sources, since its local taxes exceed 15 percent of GDP, five times beyond the supposed limit for property taxes. The important policy implication flowing from this observation is that if Ottawa and/or the provinces are not willing to transfer broad-based tax room (incomes taxes or sales taxes) to the municipalities, it is difficult to conceive of Canada’s GCRs ever achieving meaningful revenue autonomy.

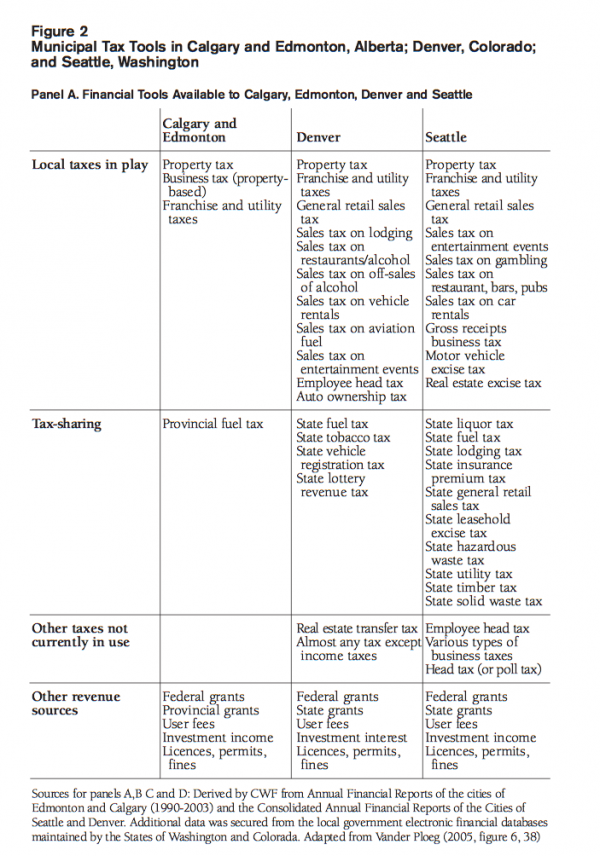

While both Canadian and US cities rely heavily on property taxes as a taxation source, Canada’s cities do to a much greater extent — 92.7 percent, compared with 72.8 percent for the United States (table 3). The reason for this is that American cities have much greater access to sales taxes than Canadian cities do — 21.0 percent compared with 1.5 percent (see table 3). By way of elaboration, Vander Ploeg (2005) presents some highly informative comparisons between Calgary and Edmonton, on the one hand, and Denver and Seattle, on the other. These comparisons are reproduced in the four panels that comprise figure 2.

Panel A presents the revenue sources (taxes and transfers) available to Calgary, Edmonton, Denver and Seattle. Seattle has access to 8 taxes in addition to those available to Alberta’s big cities, not to mention several other tax options that it has elected not to access. And, while Calgary and Edmonton do share in Alberta’s provincial fuel tax, Seattle has a share of 10 of the taxes of Washington state. In terms of “other revenue sources,” the cities have similar revenues at their disposal. Panel B, which shows Edmonton’s and Denver’s tax revenue profiles, illustrates just how dramatically taxation patterns can differ. In Edmonton, property taxes account for 93.8 percent of the city’s overall tax revenues, whereas they account for only 21.1 percent of Denver’s total tax take. Nearly two-thirds of Denver’s revenues come from a general retail sales tax.

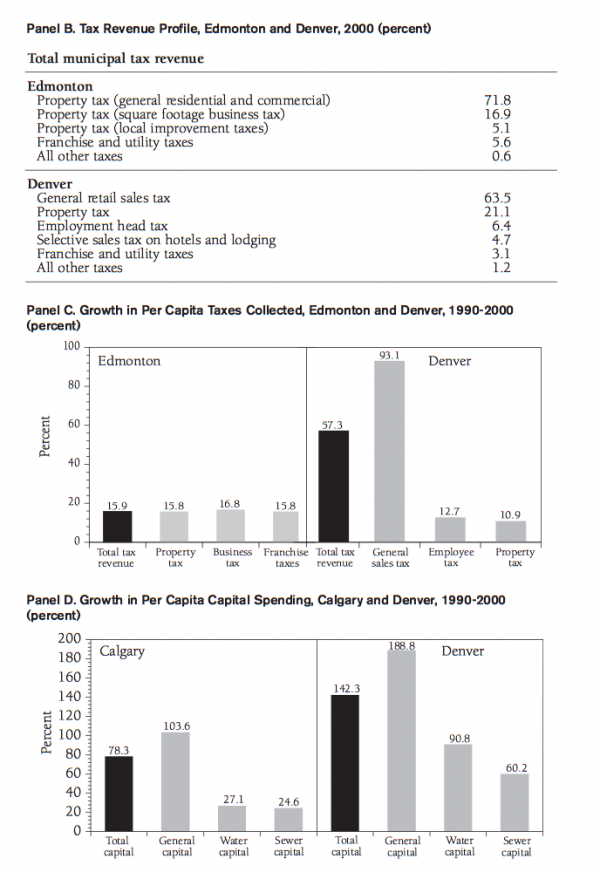

The implications of these differences, and especially the fact that Denver and Seattle have access to broad-based tax sources that grow in line with the economy, are quite remarkable. Edmonton’s growth in per capita tax over the decade of the 1990s comes in at just under 16 percent, in line with its growth in (residential and business) property tax. However, Denver’s growth in per capita tax over the 1990s is nearly 60 percent, pulled up by the 93.1 percent growth in general sales tax (panel C). Panel D reveals how this access to growth taxes ends up being transferred into per capita capital spending — Denver’s increase in per capita capital spending is nearly double Calgary’s. These are most significant differences, given that one of the principal challenges facing Canada’s GCRs is being able to compete head-on with American GCRs.

Vander Ploeg’s analyses and charts have important policy implications. Clearly, access to a range of broad-based taxes is not just a European phenomenon: it applies to some US cities as well. Moreover, the evidence suggests that having access to broader-based taxation is arguably the key to addressing Canadian GCRs’ capital-infrastructure deficit.

However, the broader reality is that there remains an enormous gulf between the economic and political potential of GCRs in the KBE, on the one hand, and the access to money and power of Canada’s GCRs, on the other. Indeed, not only do our GCRs rank very low internationally in terms of fiscal flexibility, but they are arguably the weakest, constitutionally, in the developed world. Thus, it should not be surprising that there are numerous voices calling for a rethinking and reworking of the role of our GCRs in our political, institutional and fiscal federalism. Among the most energetic and outspoken advocates of more powers for Canada’s cities is Alan Broadbent, who writes as follows in terms of the relationship between cities and their provincial political masters:

Canadian cities are creatures of the provinces. The amount of power and authority granted to them by the provinces, whether ample or not, is beyond their control. The provinces have the ability to dissolve municipalities and dismiss their governing councils. The provinces have the ability to dictate the size and structure of city governments, to set the conditions of their ability to raise capital, and to apply duties and obligations to them. The cities have no independent constitutional ability to resist whatever conditions the provinces opt to create for them.

The situation is problematic for cities in Canada, one of the most highly urbanized countries in the world. Its cities, particularly the large cities of Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, are the economic, social, and cultural engines of the entire country. Within these urban regions are contained the principal forces which make Canada an effective and competitive modern nation. Yet the cities have very little control over their decisions. They have limited ability to leverage their assets and to maximize their potential. (2000, 1)

Broadbent goes on to note that among the reasons why Canadian cities come up short in terms of what self-determination they do have is that they typically have “weak mayor” systems, a situation that is further complicated by the fact that their governance typically does not have the discipline associated with party systems.

In terms of their relationship with the federal government, it is clear that Canada’s GCRs (and municipalities generally) will never achieve the powers of the local authorities in Germany. Canada is a legislative federation, not an administrative federation and, as such, implementation is not routinely delegated to local authorities. However, there is plenty of scope between the polar positions of not allowing the central government to employ bureaucrats in the political boundaries of local governments (as is the case in Germany), and not allowing local officials to deliver or implement any federal programs. For example, our immigration-receiving cities have greater knowledge, experience and motivation than does Ottawa to ensure that Canada’s immigrants are successfully integrated into their cultural and labour-market milieux; yet, they have precious little say in these matters, let alone in the allocation of immigration-settlement monies or in ensuring that these immigration-settlement monies are appropriately coordinated with the myriad of other services to which immigrants and refugees need to have access.

At the same time, one needs to respect the perspective of University of Western Ontario political scientist Andrew Sancton (2004) on this issue. After noting that “of course, our big city municipalities should be free from oppressive provincial regulation,” and “of course [cities] should have access to a more diversified tax base,” he comments:

My position is that cities are far too important for municipal purposes alone. Policies of federal and provincial governments have always been crucial to the well-being of our cities and will continue to be, so we cannot define constitutionally who is responsible for what with respect to all the demands on government within our cities. The governance of cities will always be multi-level. (np)

These perspectives suggest that addressing the concerns of the GCRs in the KBE must involve creative processes as well as redesigned structures. This is the task of the remainder of this paper.

During the short-lived Paul Martin government, Finance Minister Ralph Goodale’s 2004 budget introduced a “New Deal for Canada’s Communities,” which included GST/HST exemptions for cities, enhanced infrastructure funding, federal gas-tax sharing, enhanced participation by municipal representatives in federal budget consultations, the creation of the External Advisory Committee on Cities and Communities (more on this later), and the appointment of a Parliamentary Secretary (and later a Minister of State) for Infrastructure and Communities. These initiatives ushered in an exciting era for cities, large and small. Even though the excitement has been turned down a notch or two under the Harper government, some recent developments merit highlight.

While much has been made of Prime Minister Paul Martin’s high-profile initiative to share the federal gasoline tax with the cities, one assumes that the GCRs were hardly pleased with it. This is because putting the transfer on an equal-per-capita basis, by province, effectively converts it into a program of equalization from GCRs to smaller cities, since gas taxes are disproportionately collected from GCRs. What the GCRs want, and arguably need, are tax transfers on a derivation basis, i.e., on the basis of what was actually collected from them in the first place. If the federal government finds it politically difficult to depart from equal-per-capita transfers by province, then the appropriate way out is to transfer the equivalent aggregate number of tax points or derivation-based tax shares to the provinces, which will in turn be committed to allocating them to their cities and local governments. To be sure, there is still no guarantee that these tax revenues will end up in municipalities on a derivation basis, but it is more likely that they will. For example, Ontario allocates 30 percent of its gas tax transfers on the basis of population and 70 percent on the basis of public transit ridership. Moreover, the prospect that investing in hub cities will have very substantial “trickle down” or convergence effects on smaller municipalities should also play a role in convincing provinces to privilege their GCRs or hub cities (Brender and Lefebvre 2006).

Federal gas-tax sharing did, however, provide an important catalyst for similar action by the provinces (e.g., Manitoba and Ontario). (Note that other provinces, such as British Columbia, Quebec and Alberta, already shared some gas taxes.) Indeed, the example of gas-tax sharing may well incite the provinces to share income taxes or sales taxes with municipalities.

The funding and distribution of benefits associated with Canada’s employment insurance (EI) program have long been a major concern for most of the GCRs. This came to the fore recently in the context of Time For A Fair Deal, the 2006 report of the (Toronto) Task Force on Modernizing Incomes Security for Working-Age Adults (MISWAA). Specifically, the task force noted that only 22 percent of the unemployed in Toronto are eligible for EI, compared with the national average, which is in the 43 percent range, and the even higher eligibility rates for cities like Saint John and St. John’s (figure 3). And, because access to the EI component of training is only available to those eligible for EI, a larger share of the unemployed in Toronto (and in many other cities, as figure 3 reveals) must be drawing upon provincial welfare or training funds rather than EI benefits or EI training funds. For a variety of reasons, this policy surely qualifies as unacceptable. The first reason is that it means that Canadians in similar situations are being treated differently under a national program. This is in part why many Canadians view EI as running afoul of interregional equity. The second reason is that the cost of living is higher in large cities like Toronto, so EI-related discrimination is especially inappropriate (Task Force 2006). The final reason relates the value system implicit in our social policy. We tend to congratulate ourselves because our medicare system is citizen-based, unlike in the United States, where health-care coverage is largely employment-based (in the sense that one needs a good job to fully access American social benefits). This linking of federal training funds to EI eligibility, rather than to the needs of similarly situated Canadians, represents a move toward the US value system as it relates to social benefits. In light of all of this, the task force proposed several recommendations, including the following (where their term “working income supplement” is identical to what we are calling the working income tax benefit [WITB]):

A new refundable tax benefit should be created consisting of a basic tax credit for all low-income working-age adults and a working income supplement for low-income wage earners. Most Task Force members believe this new benefit should be federally financed and administered.2 (2006, 32)

It also recommended that EI eligibility rates become standardized across Canada. Its preferred option is to extend the existing regional preferences (relating to entry and duration of benefits) uniformly across the country. With respect, my preference would be to standardize upward, as it were, and to remove the regional provisions that reward short-term labour-force attachment. One might maintain the current EI contribution rates, but roll the resulting “excess premiums” into a payroll tax dedicated to training for all Canadians or perhaps as a payroll tax dedicated to financing the WITB.

What is most intriguing about these proposals is the call for Ottawa to play a larger role in income-distribution among the unemployed and the working poor. Arguably, this would be entirely salutary for Canada’s GCRs (and cities generally), because one legitimate fear is that powerful cities would put efficiency and wealth creation before income distribution in terms of their overall priorities. To a considerable degree, such a focus on efficiency would be essential, since GCRs in the KBE are the wellspring of competitiveness and innovation. Moreover, given the recent volatility of regional fortunes and the resulting interregional migration, it seems that helping citizens adjust to variations in regional economic conditions should not fall as much as it currently does on the provinces, and especially not on the GCRs. With Ottawa already playing an income-support role for the children and the elderly, it might also consider extending its income-distribution role to the working poor in the form of a working income tax benefit. In other words, for cities to succeed in ensuring “place prosperity,” the senior levels of government need to play a larger role in ensuring “people prosperity.”

Prime Minister Harper’s commitment to open federalism is a commitment, in part at least, to respect the Constitution, including the provision that essentially makes cities the creatures of the provinces. Presumably this means it is unlikely that Prime Minister Harper will embrace federal-municipal tax sharing à la Paul Martin. On the other hand, the Conservatives are about to embark on an initiative that will serve to increase the options for, if not the likelihood of, a tax transfer to the provinces, which could then be passed on to the cities.

Specifically, the 2006 federal budget background paper, Restoring Fiscal Balance in Canada (Finance Canada 2006), asserts that for any federal action to redress the fiscal imbalance, there would have to be a provincial quid pro quo. One element of this quid pro quo would have to be a commitment on the part of the provinces to harmonize provincial sales taxes. Obviously, this would mean harmonizing the provincial PSTs with the GST for Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, British Columbia and PEI (since Quebec’s and the rest of Atlantic Canada’s provincial sales taxes are already harmonized, and Alberta, with no PST, can be viewed as also falling into the harmonized camp). This would be an excellent policy in its own right, since there are substantial competitive gains to be had from converting the PSTs to a GST format (such as an overall reduction in corporate taxes, since typically PSTs tax capital inputs and intermediate inputs generally). This situation would not occur under a GST, because these input taxes would be eligible for rebates. Moreover, according to Bird and Smart (2006), the GST provinces have had larger increases in investment than the PST provinces. The roadblock preventing provinces from capturing these gains is a political one: converting a PST to a GST may run up against considerable public resistance. In this light, Ottawa’s insistence that sales tax harmonization be part of the quid pro quo for addressing fiscal imbalance may well pave the political way for the provinces to make the conversion.

If this were to occur, it would open up the possibility of a GST tax transfer to the provinces. Arguably, the GST is an appropriate choice for a derivation-based tax transfer or even tax sharing. One reason for this is that per capita GST revenues would be distributed more equally among provinces than would personal income taxes and corporate taxes. Moreover, since Prime Minister Harper has promised a further cut in the GST — from 6 percent to 5 percent — this could take the form of vacating GST tax room to the provinces as part of a larger GST transfer. This GST transfer to the provinces could then be transferred on to the cities. This would be the “double devolution” recommended by the Harcourt Report, to which I now turn.

As already noted, among the city/municipal initiatives the Martin government undertook in its 2004 federal budget was the establishment of the External Advisory Committee on Cities and Communities (EACCC), which was chaired by Mike Harcourt, former British Columbia premier and Vancouver mayor. The committee was charged with examining the future of Canada’s cities and communities and developing a longer-term vision of the role that cities should play in sustaining our prosperity.

The report notes that the Europeans are more advanced than Canada in their embrace of subsidiarity and devolution, and it is convinced that some governance arrangements now in place (such as unfunded mandates) actually penalize the competitiveness of our people and places. All levels of government must become involved in correcting the situation; it says:

The federal government must make sure that Canada collectively is a strong nation by allowing better local choices. Provinces and territories have crucial strategic roles in reconciling policies and programs for places. Intercity networks, city-region effects and city-to-rural connections are valuable aspects of development that are less than national in scope and more than municipal in their functioning. Municipalities have important roles in delivering services, providing leadership and vision, and regulating and taxing highly localized markets.

To shape better cities and strong communities, federal capacities are needed to make connections, provincial and territorial powers are needed for strategic integration and municipal abilities are needed to engage with citizens and deliver change locally. Cooperative relationships are essential to good governance for places. To achieve the required outcome, it is the Committee’s view that it will be essential to strengthen not only provincial and territorial roles, but even more to see stronger, confident provinces and territories devolving power and resources to municipalities — working with them and civil society in new governance partnerships tailored to city-regions and neighbourhoods. (EACCC 2006, 4)

While much of the case for privileging Canadian cities tends to focus on reworking the structure of federalism (i.e., devolving money and power to the cities), the Harcourt Report puts much more emphasis on the processes of federalism. The important implication of this is that cities can also have more say about their futures if they are integral players in multi-level cooperative and collaborative approaches to governance, to policy design and to policy implementation. Janice Gross Stein has called this “networked federalism” (2006).

Nonetheless, in order to underpin this process dimension of federalism, the Harcourt Report also calls for some structural innovation, namely a “double devolution” of money and responsibilities to the municipalities:

The Committee therefore recommends a double devolution, shifting responsibilities and resources from the federal government to the provincial and territorial governments, and then from the provincial and territorial governments to the local level; the double devolution should ensure that choices about how to raise and use resources, including tax choices, move to the most appropriate local levels, where accountability to citizens is most direct.

By way of providing a rationale for this double devolution, the report adds:

The first principal purpose of double devolution is to make sure that all orders of government, with relevant partners from business and civil society, work together to implement governance arrangements that are locally appropriate, including arrangements dealing with significant city-region and neighbourhood issues that may not necessarily correspond with government boundaries. The second purpose of double devolution is to allow municipalities to develop a municipal taxation structure that gives them access to revenues, some of which grow with the economy while others provide a stabilizing influence. (5)

Clearly, one could list many other federal programs, policies and processes that could enhance the autonomy and well-being of Canada’s cities. I elaborated on some of these, such as the recommendations made by the TD Bank, in an earlier paper (2006). Nonetheless, the underlying reality is that increasing the cities’ fiscal autonomy, enhancing their powers, and improving local democracy and accountability will depend on creative changes in provincial-municipal relations.

Alan Broadbent puts the GCR-province challenge in the following context:

There is a huge number of issues where the city is the key point of delivery, where it has greater knowledge and experience, or where it can exercise the flexibility and responsiveness that leads to better delivery . . . But the city cannot structure its own solutions, because these solutions must pass the test of acceptability by a level of government with less specific knowledge, experience, or motivation. (2000, 3)

Since many GCRs are, in fact, larger than the majority of provinces and have the critical civil-servant mass needed for effective policy design and delivery, granting them powers and responsibilities in line with cities elsewhere in the world ought to be eminently achievable.

In order to advance this goal, Broadbent and a group of city politicians, business people, NGOs and academics drafted what they called The Greater Toronto Charter. The key provision is that the greater Toronto region be empowered to govern and exercise responsibility over a broad range of issues, including:

child and family services; cultural institutions; economic development and marketing; education; environmental protection; health care; housing; immigrant and refugee settlement; land-use planning; law enforcement and emergency services; recreation; revenue generation; taxation and assessment; transportation; sewage treatment; social assistance; waste and natural resource management; and water supply and quality management. (Greater Toronto Charter, 2001)

The requisite corollary provision of the charter is that the Toronto region would have to have the fiscal authority to raise revenues and to allocate expenditures with respect to the above powers/responsibilities.

Several comments are in order. The first is that the Charter focuses more on intergovernmental structures than processes. Second, it may be argued that the Charter is really a blueprint for a “city-state” (or city-province). Smaller centres would have neither the territorial scope nor the professional expertise to take on these powers. Third, and in terms of cities and multi-Hrbeklevel-governance or networked-federalism, these powers would not all be exclusive to cities. Many (perhaps most) would be shared, or concurrent powers. Indeed, some could be devolved administratively from other levels of government (as in the German federation). For example, Toronto, Montreal or Vancouver might decide to operate a “single window” for immigrant/refugee services, which could include some that currently fall under the senior orders of government. Finally, Canadian cities have more leeway than US cities to pursue their economic interests, because key elements of the social envelope, such as medicare and income support for children and seniors, are the responsibility of higher orders of government. In this regard, including social assistance in the responsibilities of cities could be problematic if the responsibility went beyond administration and coordination to embrace funding. Access to broad-based tax sources would help here, but there would still be a strong case for provincially financed social assistance (or greater federal financing, along the lines I suggested in the previous section).

With respect to funding, the Canadian model of provinces piggybacking on federal income taxes is successful at home and envied abroad. The time is ripe to replicate this at the municipal-provincial level. Presumably, this is what the Harcourt Report had in mind with the second part of the proposed double devolution. Obvious candidates for taxes to share are personal income taxes (PIT) and sales taxes (after the remaining PSTs have been converted to the GST). Initially, at least, the cities should settle for a fixed share of the tax on a derivation basis. After all, it took nearly 40 years for the provinces to win freedom to set tax rates and brackets under the shared PIT, so a settling-in period for the cities would be appropriate (and politically astute) . Moreover, and again initially, the tax transfer need not represent additional revenues. Rather, its initial role could be to replace a portion of the current 40 percent of revenues (in the Greater Toronto Area) that come from provincial grants and to reduce reliance on property taxes, especially for the growing range of services that have little relation to property. However, over time the cities will become progressively better off, since they will have access to a growing tax base.

In the meantime, “there is no reason for the cities to wait for a handout,” as Berridge asserts. Cities have many untapped or underutilized revenue sources — user fees and benefit taxation, as well as properly priced local public services — and they could even request some of the taxes currently accessible to Seattle and Denver. Moreover, as Berridge says with respect to Toronto’s utilities:

Toronto is one of the few cities in the world that still operates these services (electricity, water, garbage, transit . . . ) as mainline businesses. The ability to use the very substantial asset values and cash flows of these municipal businesses is perhaps the only financial option to provide the city-region with what is unlikely to be obtainable from other sources: its own pool of reinvestment capital…with remarkable leverage potential, both from public-sector pension funds and from private-sector institutions. (1999)

Cities would be better positioned financially and when they lobby the senior orders of government for more money and power if they utilized more fully the powers they already possess.

Even if it is true, as I posited earlier, that citizens are the principal beneficiaries of the information revolution, why push the principle of subsidiarity to the local level where democracy and accountability appear to be weaker than they are at higher government levels? Phrased differently, why has the recognized potential for democracy to thrive at the local level not materialized? One of the reasons may be that it is difficult for citizens to be enthusiastic about local democracy as long as city politicians are largely administrators of responsibilities and policies that are legislated (and funded) elsewhere. Much better, if this is the case, to join the city politicians and engage in rent-seeking at the provincial and federal doorsteps. However, with greater political autonomy involving enhanced responsibilities and greater revenue flexibility, the stage would then be set for more meaningful citizen engagement, since much more would be at stake at the city level. In a word, the result would be more local accountability and more democracy.

Along with this increased application of the principle of subsidiarity, there would also be an improvement in the dynamic efficiency of cities and their governance. This is because cities would approach their new-found responsibilities in myriads of creative ways. This is competitive federalism at play in the cities’ arena. Some might view this as needless variation. It is likely, however, to be the source of creative asymmetry, and novel ways to do things would emerge, the best of which would presumably be replicated in other cities.

Implicit in the foregoing analysis is that GCRs are different from other cities and merit preferential treatment. But surely all cities, not just the GCRs, would benefit from the dynamic-efficiency effects of acquiring greater money and power. Moreover, it might be difficult politically to privilege GCRs relative to smaller cities. In Apples and Oranges? Urban Size and the Municipal-Provincial Relationship, Roberts and Gibbins struggle with this very issue: are small cities similar enough to big cities so that they can be viewed as “small apples,” or are they really “oranges”? The authors recognize that there is a need for a new relationship between big cities and the provinces, but they reject the two extreme approaches, namely, drawing a hard line between big cities and other municipalities, on the one hand, and treating all municipalities in the same way, on the other. Their compromise is what they call the “best-of-both-worlds solution,” namely:

An opt-in framework that is flexible enough to enable those municipalities that desire greater autonomy or new fiscal tools in certain areas to adopt them, but one that does not require those municipalities that do not possess the capacity to take on the roles sought by big cities to abandon the security of their current arrangement. (2005,1)

The result would be de jure symmetry but de facto asymmetry, or “variable geometry,” as the Europeans would call it. And this, I would argue, would be good politics.

The daunting challenge is how to bridge the gap between the KBE potential of Canadian global city-regions and the ongoing Canadian reality, as well as the gap between Canadian and international GCRs. My reading of the literature is (1) that citizens and cities are indeed the principal beneficiaries of the KBE. (2) The democratization of information and the falling costs of telecomputation ensures that subsidiarity will prevails and bring government closer to the people, and (3) Given that human capital and associated KBE activities are concentrated in cities, this means that cities will increasingly drive productivity, innovation and living standards. Accordingly, GCRs need to be brought more fully and formally into the operations of Canada’s political and fiscal federalism. If one then notes that most of the world’s GCRs already have powers and responsibilities well in excess of those of Canada’s GCRs, it would seem to follow that granting GCRs enhanced expenditure and revenue-raising responsibilities should be a slam dunk.

But it clearly is not a slam dunk politically. One reason for this is that at stake is a realignment of effective powers in the federation, which is tantamount to de facto, if not de jure, constitutional change. Governments do not part with such powers lightly, not only because they want to “protect their turf,” but also because arguably all the institutional structures and processes in our federation rest on the current distribution of powers. Indeed, while one may lament the continued gap between the potential and the reality of Canada’s GCRs, constitutional change should be difficult, since at issue are society’s underlying property rights, as it were.

On a more positive note, however, considerable progress is already apparent. The “New Deal for Canada’s Communities” in the 2004 budget, in particular Ottawa’s gastax sharing (despite the equal-per-capita allocation), was a very significant initiative, because it “embarrassed” the provinces into recognizing the potential of their cities. Moreover, several major institutions have put their research, reputation and influence behind a better deal for our cities — the TD Bank, the Canada West Foundation, the Conference Board of Canada, the Maytree Foundation and the Institute for Research on Public Policy, among others. In addition, Ontario has recently reworked its municipal act in directions that would allow Toronto, for example, to deal directly with Ottawa in certain areas. Thus, one can envision the implementation of certain federal programs or services being delegated to the cities, which would clearly enhance the cities’ ability to coordinate, if not integrate, their various services. In tandem with many other developments, we are witnessing meaningful progress in terms of the structural and process dimensions of federalism. And from this there is no turning back.

However, the real breakthrough will probably have to come from the provinces. As was the case with Saskatchewan and medicare, one province needs to embrace broad-based tax sharing with its GCRs and cities generally, and then the game would be afoot. And this will be about “when” and not “if,” because all Canadians know that Canada needs globally competitive cities. If the provinces are not up to the challenge of privileging their GCRs, then Canadians and the GCRs must and will work together to ensure that subsidiarity privileges the cities, even if it means bypassing the provinces.

Battle, Ken, Michael Mendelson, and Sherri Torjman. 2006. Towards a New Architecture for Canada’s Adult Benefits. Ottawa: Caledon Institute of Social Policy.

Berridge, Joe. 1999. “There is No Need to Sit and Wait for a Handout.” The Globe and Mail, June 7.

Bird, Richard, and Richard Smart. 2006. “Transfer Real Taxing Power to the Provinces.” National Post, June 27, FP17.

Brender, Natalie, and Mario Lefebvre. 2006. Canada’s Hub Cities: A Driving Force of the National Economy. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada.

Broadbent, Alan. 2000. “The Autonomy of Cities in Canada.” In Toronto: Considering Self Government, edited by Mary Rowe. Owen Sound: The Ginger Press.

Castells, Manuel. 2001. The Internet Galaxy. New York: Oxford University Press

Chernick, Howard, and Andrew Reschovsky. 2006. “Local Public Finance: Issues for Metropolitan Regions.” In Competitive Cities in the Global Economy, edited by Lamin Kamal-Chaoui. Paris: OECD, 288-298.

Courchene, Thomas J. 2006. “Citistates and the State of Cities: Political-Economy and Fiscal- Federalism Dimensions.” In Municipal-Federal-Provincial Relations in Canada, edited by Robert Young and Christian Leuprecht. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press for the Queen’s Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, 83-115.

External Advisory Committee on Cities and Communities (EACCC). 2006. Chaired by Michael Harcourt. Restless Communities to Resilient Places: Building a Stronger Future for All Canadians. Final report. Accessed May 14, 2007. https://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/eaccc- ccevc/rep-rap/summary_e.shtml

Finance Canada. 2006. “Restoring Fiscal Balance in Canada: Focusing on Priorities.” Budget 2006. Ottawa: Finance Canada. Accessed May 17, 2007. https://www.fin.gc.ca/budget06/ fp/fptoce.htm

Florida, Richard. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic Books.

Friedman, Thomas L. 1999. The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization. New York: Ferrar, Straus and Giroux.

Gertler, Meric, Richard Florida, Gary Gates, and Tara Vinodrai. 2002. “Competing for Creativity: Placing Ontario’s Cities in the North American Context.” A report pre- pared for the Ontario Ministry of Enterprise, Opportunity, and Innovation, and the Institute for Competitiveness and Prosperity.

Greater Toronto Charter. 2001. In Towards a New City of Toronto Act, with contribu- tions by Alan Broadbent et al. Ideas that Matter. Toronto: Zephyr Press (page 40). Accessed June 1, 2007. https://www.ideasthatmatter.com/ cities/CityOfTorontoActJune2005.pdf

Harris, Richard G. 2003. “Old Growth and New Economy Cycles: Rethinking Canadian Economic Paradigms.” In The Art of the State: Governance in a World without Frontiers, edited by Thomas J. Courchene and Donald J. Savoie. Art of the State III. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy, 31-63.

Horsman, Mathew, and Andrew Marshall. 1994. After the Nation State: Citizens, Tribalism and the New World Disorder. London: Harper Collins.

Hrbek, Rudolph, and Jan Christoph Bodenbender. Forthcoming. “Federal- Municipal Relations: Germany.” In Spheres of Governance, Comparative

Studies of Cities in Multilevel Governance Systems, edited by Harvey Lazar and Christian Leuprecht. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press for the Queen’s Institute of Intergovernmental Relations.

Lotz, Jørgen. 2006. “Local Government Organizations and Finance: Nordic Countries.” In Local Governance in Industrial Countries, edited by Anwar Shah. Washington: The World Bank, 223-64

Martin, Roger, and James Milway. 2003. “Ontario’s Urban Gap.” National Post, July 4.

McMillan, Melville L. 2006. “Municipal Relations with the Federal and Provincial Governments.” In Municipal-Provincial- Federal Relations in Canada, edited by Robert Young and Christian Leuprecht. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press for the Queen’s Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, 45-82.

McMillan, Melville L. 1997. “Taxation and Expenditure Patterns in Major City- Regions: An International Perspective and Lessons for Canada.” In Urban Governance and Finance: A Question of Who Does What, edited by Paul Hobson and France St-Hilaire. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy, 1-58.

Pastor, Manuel. 2006. “Cohesion and Competitiveness: Business Leadership for Regional Growth and Social Equity.” In Competitive Cities in the Global Economy, edited by Lamia Kamal- Chaoui. Paris: OECD, 288-98.

Roberts, Kari, and Roger Gibbins. 2005. “Apples and Oranges? Urban Size and the Municipal-Provincial Relationship.” Discussion paper, Canada West Foundation. Accessed June 1, 2007. www.cwf.ca/V2/files/Apples%20and% 20Oranges.pdf

Sancton, Andrew. 2004. “Governance and Cities: Constitutional Capacity Issues.” Paper presented at the conference “Embracing the Urban Frontier: Capitalizing on Canada’s Cities,” Queen’s

School of Policy Studies, April 30-May 1. Stein, Janice Gross. 2006. “Canada by

Mondrian: Networked Federalism in an Era of Globalization.” In Canada by Picasso: The Faces of Federalism, by Roger Gibbins, Antonia Maioni and Janice Gross Stein, with an introduction by Allan Gregg. The 2006 CIBC Scholar-In- Residence Lecture. Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada, 15-58.

Task Force on Modernizing Income Security for Working Age Adults (MISWAA). 2006. Time For A Fair Deal. St. Christopher House, in partnership with The Toronto City Summit Alliance. Accessed May 17, 2007. www.stchrishouse.org/get-involved/ community-dev/Special%20Projects/ ModernizingIncomeSec/MiswaaFinalReport.php

Vander Ploeg, Casey. 2005. “Rationale For Renewal: The Imperatives Behind a Big City Partnership.” Western Cities Project Report no. 34. Canada West Foundation.

Zysman, John. 1983. Government, Markets and Growth: Financial Systems and the Politics of Industrial Change. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Thomas J. Courchene is the Jarislowsky-Deutsch Professor of Economic and Financial Policy and director of the Institute of Intergovernmental Relations at Queen’s School of Policy Studies and is Senior Scholar of the IRPP. He is the author of some three hundred articles, monographs and book chapters on a wide range of Canadian policy issues. He is a past president of the Canadian Economics Association and the North American Economics and Finance Association, holds Honorary Doctor of Laws degrees from the universities of Western Ontario, Saskatchewan and Regina, and is an Officer of the Order of Canada.

This publication was produced under the direction of Jeremy Leonard, Senior Fellow, Policy Outreach, IRPP. The manuscript was copy-edited by Francesca Worrall, proofreading was by Lynn Gauker, production was by Chantal Létourneau, and printing was by AGL Graphiques Inc.

Copyright belongs to IRPP. To order or request permission to reprint, contact:

IRPP

1470 Peel Street, Suite 200

Montreal, Quebec H3A 1T1

Telephone: 514-985-2461

Fax: 514-985-2559

E-mail: irpp@nullirpp.org

irpp.org

All IRPP Choices and IRPP Policy Matters and are available for download at www.irpp.org

To cite this document:

Courchene, Thomas J. 2007. “Global Futures for Canada’s Global Cities.” IRPP Policy Matters 8 (2).