A transformation is taking shape in the policy framework under which airlines are organized and operate international air services. Since the early age of commercial air travel, international air services have been governed by intergovernmental bilateral agreements. Until fairly recently, these agreements micro-managed international air operations by specifying the routes to be flown, the frequency of service, the equipment to be used, and the commercial relationships between airlines based in the partner countries operating the authorized routes. Although much of this micro-management has fallen away, some important remnants persist, and the regulation of international air services remains firmly in the grip of bilateral agreements.

The agent of transformation will be a new set of international air agreements between the European Union (EU) and all countries that currently have individual bilateral agreements with EU members. The EU’s decision to replace these bilateral agreements with a single EU-wide agreement flows from years of debate in the EU and a European Court of Justice decision declaring some aspects of bilateral agreements between members of the EU and other countries a violation of European law. Over time, all countries that have bilateral agreements with individual EU members will face the choice of negotiating a new, single agreement with the EU (or, at a minimum, amending the clauses that offend EU law) or accepting the abrogation of current agreements, thereby making the provision of air services with the EU subject to the whims of regulators and politicians.

The revolutionary element of the new or amended agreements will be an EU-wide nationality provision that will convey commercial rights to any airline owned by nationals of any EU member country that enters such an agreement. Under most current agreements, only airlines that are majority owned and operated by nationals of the partner countries may be designated to operate international air services. The EU will also be trying to obtain the right of establishment; that is, the right of European investors to own and operate airlines in other countries, and the right of cabotage, that is, the right of a foreign airline to operate commercial service between two points in another country. Such an agreement would effectively separate airlines offering international services from their home-country base and would have a profound and positive impact on travellers, cargo operators, airports, airplane manufacturers and nimble airlines.

In the immediate phase, the EU and the United States will open negotiations to create an open transatlantic aviation market. Negotiations with Canada and other third countries will follow. Canada may be tempted to cling, limpet-like, to old polices and refuse an invitation to enter into an EU-wide agreement. A wiser course would be to launch the preparations necessary to advance the interests of Canadian airlines and travellers in the new world of international air travel. It is necessary to grasp the importance of this transformation and seize the opportunity to break with the past, rather than keeping our transport policy head firmly fixed in the sand.

Today’s air travel radar screen is cluttered with blips showing jumbo financial losses, radically changing consumer preferences and outmoded business models. Whatever the shape of the industry that emerges from the current crisis conditions, providing a policy framework that accommodates international growth in air traffic should be an essential goal. As Air Canada and its partners and competitors do away with with outmoded business models, there is an equally urgent need to dispense with outmoded policies.

Although the implications of the new European policy have global reach, this article examines some of the commercial implications of the EU mandate for only transatlantic air relations.

International trade and air policies have followed sharply divergent paths. International trade policy has been firmly rooted in the principles and for the most part the practice of nondiscrimination embodied in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and now the World Trade Organization (WTO). The explicit aim of international trade policy has been to progressively reduce and eventually eliminate barriers to trade, with a view to promoting economic growth. It has reposed upon liberal domestic economic policies in the principal trading countries, which have progressively assigned a greater role to market forces to determine winners and losers. Regular rounds of trade negotiations provided for increasing exposure of national economies to international competition and required firms and workers to adjust to this competition. The objective was to provide equality of opportunity to exploit comparative advantage by removing government barriers to the free flow of international trade (Trebilcock and Howse 1999).

International air policy has eschewed most-favoured-nation treatment as its organizing principle in favour of the tight regulation of international air services through bilateral agreements. Like other policies governing service sectors such as telecommunications, international air policy was the natural consequence of heavily regulated domestic air policy frameworks that strictly controlled the terms and conditions under which domestic air services could be offered. Countries unwilling to allow the free play of market forces in the domestic air transport market to determine winners and losers were, accordingly, exceedingly cautious about the level of international competition they were prepared to tolerate for their airlines. Moreover, in most countries, state-owned airlines operating as a monopoly or in competition with privately owned airlines have borne the burden of serving as a symbol of nationhood, providing further justification for keeping air services distant from market-determined outcomes.1

The antecedents of international air policy lie in the Convention Relating to the Regulation of Aerial Navigation, negotiated in Paris in 1919, which in its first article granted each state “complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory.” States thus acquired rights with respect to the operation of aircraft in their airspace that were analogous to the sovereign rights of states under customary international law to control the entry of aliens into their territory. Such entry is a matter of domestic jurisdiction arising out of the state’s exclusive control over its territory. The practical effect of these rights was and remains that airlines operating aircraft in the airspace of another state must have the permission of that state. This principle was reconfirmed at the 1944 Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, which created the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and laid the basis for the postwar evolution of bilateral agreements. More importantly for the course of air policy, the convention rejected the United States’ preference for what was essentially an open skies policy in favour of the British position of tight regulation of international traffic, with governments controlling the rights to participate in that traffic. The instrument of choice became the bilateral air services agreement (Sampson 1984, 63-71).2

The typical bilateral air agreement mirrored rigid domestic regulation (Doganis 1991, 24-42). The objective was to achieve strict reciprocity of service. The agreements authorized each country to designate the airline(s) permitted to operate, normally one airline per country; required the designated airlines to be majority owned and operated by nationals of the designating state; specified the routes that could be operated and often the aircraft types that could be employed on the routes; required the designated airlines to obtain the approval of each national regulating authority for the fares it could charge; and encouraged the airlines to collude in the setting of these fares (Doganis 1991, 35-40).3 A more liberal form of agreement, the “Bermuda” type named after the first US-UK agreement, left control of frequency and capacity to agreement between the designated airlines, subject to the regulations of the partner countries. In many cases the bilateral agreement required that the airlines designated to operate the agreed routes share the revenues earned, meaning in practice that the more competitive airline paid a royalty to its competitor in order to operate the route. A market shift favouring one of the designated airlines in an agreement created a presumption of renegotiation, to redress not the balance of opportunities but the balance of outcomes.

Just as tight regulation of domestic services generated equally tight international rules, the collapse of domestic regulation in the United States and its slower but inevitable erosion in Europe and Canada brought radical changes to the content — although not to the outward form — of bilateral air agreements. In the US, the 1978 Airline Deregulation Act abandoned control of route networks and phased out regulation of fares. By 1983, the US airline industry had moved from an environment of intrusive regulation to freedom to choose routes, frequencies, capacity and prices (Pickerell 1991; Doganis 1991, 46-75). In the European Union, deregulation meant that national jurisdiction over airline operations by individual EU countries was replaced by Union-wide authority. By 1993, the EU implemented rules that granted airlines from any member country full traffic rights on any route within the Union, free of controls on capacity and fares. Norway, Iceland and Switzerland, which are non-EU countries, are part of this regime, as will be the 10 new members of the EU from Central and Eastern Europe (Doganis 2001, 38-44).4

Bilateral air agreements were adapted to accommodate the new regulatory and industry environment. New US agreements signed with the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany in 1978 established the early model of the open skies agreement. While there were variations, the agreements provided for the multiple designation of airlines, replacing the single or dual designations of previous agreements. Frequency and capacity controls were abandoned. The requirement for regulatory approval of fares was replaced by the formula that the fares announced by the airlines would become operative unless both governments disapproved.5 Airlines remained limited to the routes specified in the agreement. By 1992, even this limitation was abandoned (although the prohibition on cabotage remained), as the Netherlands and the US entered the first full open skies agreement. Agreements on this pattern followed between Canada and most but not all the countries of the EU (Doganis 2001, 23-37).6

A key provision of the full open skies model is regulatory approval of code-sharing, which allows an airline to sell tickets on services operated by another airline as long as the route rights are contained in the agreement. While airlines had been permitted to co-operate in the transfer of passengers and cargo, code-sharing, combined with domestic and international deregulation, became an essential feature that spawned the emergence of deeply integrated international alliances. These alliances enable airlines to offer prospective partners unrestricted access to all points in their home country. They create a worldwide reach built around an international hub-and-spoke system through which traffic is routed via a few central points. The coordination of flight schedules around major hubs, the capacity to sell tickets through a common computer reservation system on any flights operated by alliance members, the development of common service standards and marketing, and the pooling of fre- quent flyer plans have created powerful marketing tools to create and retain passenger loyalty. Competition among member airlines for traffic between points served within the alliance has been replaced by the sharing of traffic routed through hubs and spokes. Airlines outside alliances are limited to point-to-point traffic, and they face severe disadvantages in competing for traffic that originates outside the departure and destination points specified in the route schedules of their bilateral agreements. Currently four major international alliances account for more than two-thirds of all international air traffic (International Air Transport Association 2002, 22).7

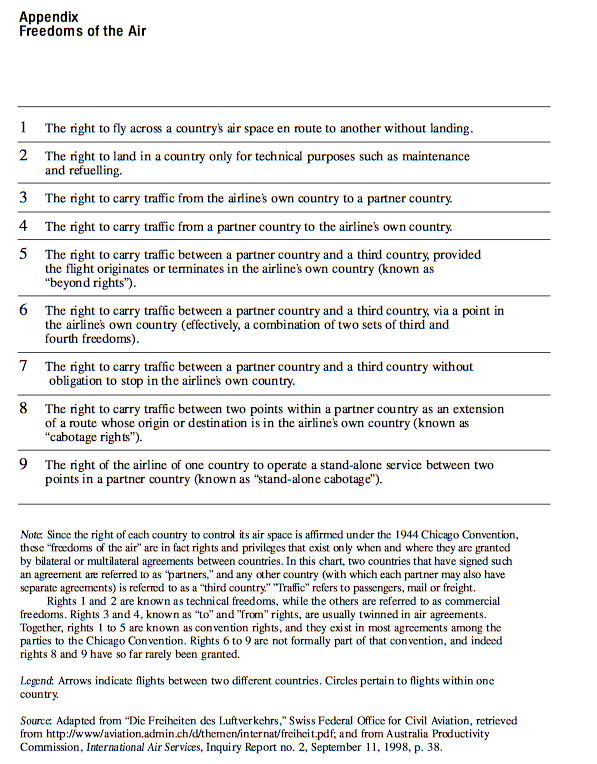

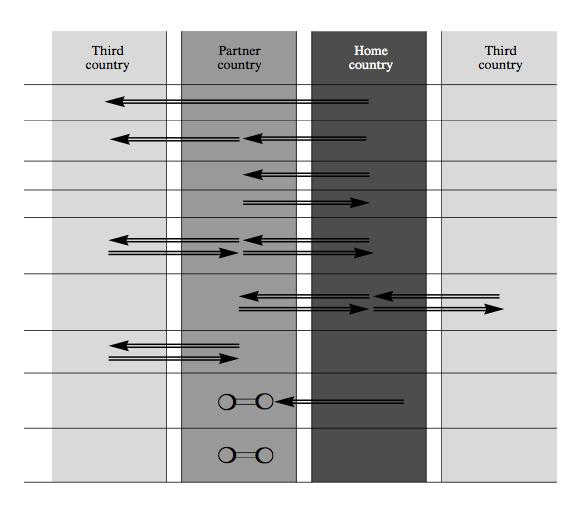

The US open skies agreements with EU countries also provide for “fifth freedom” rights. (For a glossary of the so-called freedoms of the air, see the appendix on page 20-21.) This is the right granted by one country to an airline of another country to put down and take on traffic that is coming from or going to a third country, in the territory of the first state. The exercise of that right requires, of course, the agreement of the third country.8 In the early postwar period, before the rapid growth of international air traffic, such rights were often essential to the profitable operation of a specific route. Negotiations often foundered on such rights, since countries jealously regarded all passengers originating within their territory as assets to be allocated to their airlines or their partners in bilateral agreements. While the emergence of alliances and long-range aircraft has rendered moot the old arguments over fifth freedoms, the incorporation of such rights in the new agreements contributes to the dismantling of the regulatory straitjacket regarding commercial operations.

Notwithstanding the extent of deregulation, remnants of the old regulatory regime constitute serious obstacles to realizing the full efficiencies of modern airline operation. Most countries require that airlines designated under bilateral agreements be majority owned and controlled by citizens or residents of the designating state.9 This requirement effectively prevents international mergers and acquisitions of airlines providing international service, since the merged or acquired airline would lose eligibility for designation under the bilateral agreements (Doganis 2001, 40).10 Most countries restrict the level of foreign ownership of airlines registered in their countries. In Canada and the US, the limitation is 25 percent. In the EU, non-EU nationals are limited to 49- percent ownership of EU airlines. This requirement is an effective barrier to mergers and acquisitions and largely confines the growth potential of airlines to the capital that can be raised by domestic investors. The third remnant is the prohibition on cabotage, that is, the carriage of traffic by a foreign-owned airline between two points in another country. It has long been a source of grievance among European carriers that while they are limited to serving single points in the US, their American rivals can serve the whole of the US by funnelling traffic through their domestic hubs to multiple points in the EU. While the emergence of alliances addresses this problem for alliance members, airlines outside alliances face a competitive disadvantage in attracting traffic beyond their cities of origin and of destination.11 Breaking down these barriers involves formidable obstacles rooted in an outdated commingling of national and airline-industry interests. The proposals for a new policy framework that the Europeans are to present to the US are preliminary steps toward developing globally efficient airlines.

For close to 50 years the federal government sought to micro-manage the Canadian airline industry, principally through its chosen instrument, the Crown-owned Trans-Canada Airlines (later Air Canada). The objective was to ensure Air Canada’s viability by guaranteeing it a 75 percent share of domestic traffic. Only one other airline, Canadian Pacific Airlines (subsequently Canadian Airlines), was licensed (from 1959) on a limited basis to operate transcontinental routes (Corbett 1965, 160- 181). Small airlines were licensed to operate regional or local routes to supplement but not compete with Air Canada’s services, and they were prohibited from operating outside their region. Until 1978, the federal cabinet approved airline entry into and exit from routes as well as the fares that airlines could charge. Deregulation in Canada started later than in the US, and, unlike in the US, where deregulation was rapid, in Canada the process evolved slowly, only becoming official in 1988. Entry into the industry was subject to a “fit, willing and able test,” licence restrictions were abolished, and fares were not subject to regulation except for a publication requirement and an obligation not to charge above the published rate for a route. These steps, combined with the privatization of Air Canada, created a deregulated environment for all domestic air services except for those in Northern Canada, where remnants of regulation remained (Oum et al. 1991).

Internationally, the government divided the world between Air Canada and Canadian Airlines. As the chosen instrument of air policy, Air Canada was granted most of the heavily travelled routes to the US and Western Europe. The more lightly travelled Latin-American and Asian routes were granted to Canadian Airlines. This division of the world was not consistently applied, as Canadian Airlines acquired routes to the Netherlands and Southern Europe and Air Canada was granted routes in the Caribbean. Demands by new Canadian airlines, such as Wardair, for international route rights created further inconsistencies in the attempt to achieve a coherent parcelling out of the market, since it became necessary to restrict the rights of established Canadian carriers in order to create room for the new entrants. Whatever the logical inconsistencies of Canadian international air policy, bilateral air agreements, of which some 70 were negotiated, were the counterpart to the tight regulation of domestic air services. Like those of Europe and the US, Canada’s bilateral agreements became complicated tools for the micro-management of international air services.

The 1995 open skies agreement with the US broke the mould for Canadian air agreements. Phased in over three years, the agreement provided for unrestricted transborder access for airlines of either country to any destination in the other, with no restrictions on fares. It was eventually followed by the effective replacement of the division of the world between Air Canada and Canadian Airlines approach by the allocation of all international air routes. Those routes, which generated 300,000 one-way originating passengers, became open to multiple designations if the governing bilateral agreements so permitted. All other routes were made subject to a “use or lose it” provision, so that one Canadian airline could not deny service to a point that it chose not to operate. If no Canadian carrier was interested in operating to a given country, a carrier from that country could be granted limited access to all points in Canada except Toronto, even in the absence of a bilateral air agreement (Canada Transportation Act Review Panel 2001). Following the agreement with the US, Canada amended its agreements with most European countries to reach open-skies-type agreements in practice if not in name, including the critical provision of code-sharing but without fifth freedoms. Those bilateral agreements, such as the agreement with Italy, that conform with the old model reflect airline priorities rather than government policy preferences.

If Canada has moved with the times in deregulating domestic and international routes and fares, it remains, like most other countries, steadfastly glued to the principle of domestic ownership of Canadian carriers. Currently, foreigners may own up to 25 percent of the voting shares of a Canadian air carrier. Although the panel reviewing Canadian transportation policy recommended that the 25 percent limit be raised to 49 percent (Canada Transportation Act Review Panel 2001, recommendation 7.3), the government has shown no signs such a step is imminent. Although it is possible that the events surrounding Air Canada’s entry into and anticipated exit from bankruptcy may produce some change, it is clear that the government is comfortable with the principle that airlines in Canada be domestically owned and operated.12 The government seems equally unperturbed by the prospect of a US-EU agreement that breaks new ground in the regulation of international air services. In the words of Transport Minister Collenette, Canada “has an airline policy that works…It would be incorrect to conclude that Canada must be an active participant in EU-US negotiations…Canadians can rest assured that the government will be following these discussions very closely.”13 As history demonstrates, followership is a sacred principle of Canadian air policy.

The international air law community is seldom concerned with the results of domestic court decisions. They are considered to be domestic matters. But when a decision is rendered by the Court of Justice of the European Union (known as the European Court of Justice, or ECJ), interpreting the founding treaties of the European Community (EC) on a matter relating to the internal and external powers of the EC vis-à-vis its member states, it may have profound consequences. Such is the case with the long-awaited decisions rendered by the ECJ on November 5, 2002, in the “open skies” cases.14 These decisions take their place alongside a number of other landmark cases that confirm or extend EC powers. Since the EC is the second most important legislative body in the world and the most important market for air transport services, any extension of EC powers in the field of air transportation is bound to have an impact on the international community.

The EC has been acquiring jurisdiction over various aspects of air transportation since the adoption of the first set of measures in 1988. Since then, successive legislative measures adopted by the Council of the European Union have greatly expanded EC authority over many aspects of air transportation, safety, and lately even security within the European Community (Dempsey 2001). These powers have dealt with the internal EC market. But the European Commission, the executive body, whose mandate is to ensure respect for the founding treaties and other rules of EC law, has sought a mandate to negotiate new air transportation agreements with foreign states. Member states of the EC have been very reluctant to concede this function to the commission, arguing variously that it has no authority over the external air services market and that all matters pertaining to international air services remain within national jurisdiction.

In the face of three refusals to grant it a negotiating mandate, and in the face of efforts by no fewer than 10 member states to negotiate new bilateral air transport agreements with the United States, the European Commission took these states to the ECJ to challenge the legality of various aspects of the agreements concluded or under negotiation with the United States. The commission’s principal arguments centred on three assertions: 1) that the traditional provisions on national ownership and control of designated airlines in the bilaterals violate the principle of freedom of establishment of persons and corporations established by article 43 of the European Community Treaty; 2) that by virtue of adopting extensive EC legislation governing air transportation, member states had lost the authority to negotiate these matters with foreign states, and, more generally, 3) that bilateral agreements made in the interests of individual member states potentially violate the principles of EC competition law and upset the freedom to provide services across national lines throughout the Community, particularly with respect to air fares on intra-Community routes, computerized reservation systems and the allocation of airport slots.

Advocate General Tizzano delivered his opinion on January 31, 2002.15 This opinion, which is designed to assist the court by elucidating the issues before it in a particular case, accepted many of the commission’s arguments and set the stage for the decision that the ECJ finally rendered on November 5, 2002.

The court clearly decided some matters and left others open for future development. First, seven bilateral agreements with the United States are declared to violate some aspects of EC primary treaty law and secondary legislation. Implicitly, similar provisions in some 1,500 other bilateral agreements in force between member states and foreign states, as well as those of the 10 (and ultimately 13) future EC member states, are similarly in violation. Second, the decision is unequivocal in stating that the national ownership and control provisions in the bilateral agreements violate a central treaty principle of freedom of establishment of corporations, in that they provide for the designation only of airlines subject to the ownership and control of the signatory state or its nationals. In doing this, the signatory states have denied the right of airlines of the other 14 member states to receive national treatment at their hands. Third, the court is unequivocal in confirming that, to the extent that internal jurisdiction is vested in the EC, this jurisdiction is projected externally. In doing so the court has applied a long-standing principle applicable to the EC’s external relations. Where the court is less categorical is with respect to the extent of the EC’s external jurisdiction over air transport, as the judgment speaks only of air fares, slot allocation and airline reservation systems. With respect to these three matters, EC external jurisdiction is complete, but on other matters it can still be argued that jurisdiction is shared with member states. The implication of this is that the European Commission now has a strong but limited mandate to negotiate at least certain air transport matters with foreign states. Finally, in deciding implicitly that each state cannot seek its own exclusive advantage in negotiating bilateral agreements with foreign states, the court has made it very difficult for any member state to continue to do this, and it has also implicitly strengthened the commission’s position to argue that EC competition law applies to both the external and internal markets for air transport services.

The ECJ has the exclusive authority to interpret primary and secondary law,16 and it has long held that this law enjoys supremacy over the domestic law of member states. It would thus be very difficult to undo what the court has done. The treaty principle of freedom of establishment would have to be changed in respect of international air transport, the existing edifice of EC air transport law regulating the internal market would have to be withdrawn, and the deregulated EC internal market in air services would have to conform with Chicago Convention principles. The only area where there is clear discretion to adopt a waiver is with respect to competition law. Since the court has decided what principles speak to EC external air transport law, the European Commission has no discretion and must seek to apply the principles to EC relations vis-à-vis other states.

A number of consequences can be discerned. Not all can be described with certainty; however, it is certain that the European Commission now enjoys an immensely strengthened hand in its efforts to regulate external air transport services. The ECJ has made it clear that the Community enjoys extensive jurisdiction over internal and external air transport matters. Some of these powers are shared with member states, but others are held exclusively. It is also clear that the commission is under a legal obligation to pursue policies that are hard to reconcile with the Chicago Convention bilateral air transport model, which is based on national sovereignty over national airlines and is enshrined in most of the 5,000 bilateral air transport agreements in force today. The commission is under a legal obligation to negotiate at least fifth and possibly also seventh freedom rights for all Community carriers (see the appendix on pages 20-21). It is for this reason that the decision is of such great significance for international air transport law.

The European Commission was quick to act. On November 20, 2002, it called for the denunciation of existing bilateral agreements between the member countries and the US. The commission stressed that the court judgment affected all existing bilateral agreements between EU members and other countries. Further, no changes to member state air policy of any kind were to be undertaken pending confirmation of their compatibility with EU law. It then called upon the Council of Ministers (representing the member states) to agree to a mandate for the negotiation of EU-wide agreements that would, inter alia, aim to further liberalize the transatlantic market and investment rules (European Commission 2002). In February 2003 the commission formally sought a mandate to negotiate EU-wide agreements to remove discrimination between EU-based airlines. These agreements would ensure that trade rights to and from the EU would no longer be reserved for national airlines but would be open to airlines that are owned and controlled by European citizens (European Commission 2003a).

On June 5, 2003, the transport ministers of the EU member states agreed to a three-part package of measures sought by the commission. The first part is a mandate to open negotiations with the US aimed at achieving, in the commission’s words, an “Open Aviation Area.” This would create a free trade area for air transport by giving EU and US airlines complete freedom to serve any pair of airports in the United States and in EU countries. The commission intends as well to seek a relaxation of the restrictions on ownership and control to make transatlantic mergers and acquisitions possible. The second is a mandate for negotiating with other countries to correct the problems identified by the ECJ, notably, nationality requirements in the current bilateral agreements. The priority countries for these negotiations are to be identified by the commission and the Council of Ministers. The third element recognizes the existence of hundreds of current bilateral agreements and the need to manage these relationships in accordance with EU law. Thus the council agreed, subject to the approval of the European Parliament, to issue a regulation that permits member countries to continue to negotiate bilateral agreements subject to EU co-ordination and on the basis of a common EU text (European Commission 2003b, 2003c).

Prior to the council meeting, the US made clear its readiness to engage with the EU to develop a new approach to the management of air relations. In a speech, Jeffrey Shane, US undersecretary of transport, argued the case for a broader multilateral framework to replace the current network of bilateral agreements. In the US view, geographically limited bilateral agreements lack the scope either to foster the achievement of global efficiencies or to provide the seamless system of air transport that a globalized economy requires. The US, declared Shane, would be prepared to enter into negotiations with the EU (Shane 2003). Subsequently, at the 2003 annual US-EU summit meeting, President Bush issued a joint statement with the presidents of the European Council and the European Commission announcing their agreement to begin comprehensive air negotiations in the early autumn of 2003. The purpose will be “to build upon the framework of the existing agreements with the goal of opening access to markets.”17 While officially the US does not echo the ambitious EU agenda in respect of investment- and nationality-based ownership restrictions, it is committed to a broad agenda that offers the prospect of a radically different model for the management of transatlantic air relations (White House 2003).

In a study conducted for the European Commission, the Brattle Group, a UK-based consultancy, estimated the future benefits of a EU-US transatlantic open aviation area at €5 billion (some C$7.5 billion at the time of writing). These benefits would occur as a result of massive productivity gains as more efficient airlines displaced weaker airlines and captured economies of scale and pricing synergies. Transatlantic flows of capital and labour would lead to consolidation and deeper integration (Reitzes et al. 2002). In a vigorous riposte, airline analyst Hubert Horan argues that these estimates are unsupported by the analysis and that, more importantly, the US is likely to bring a different perception to the costs and benefits of negotiating the complete liberalization of the regulations governing transatlantic air traffic. He also points out that the nationality provision on which an open aviation area would largely depend anchors many different and critical aspects of airline operations — notably safety — that render the negotiation of any agreement a complicated task (Horan 2003).18

The EU and the US were scheduled to hold their first negotiating session on October 1-2, 2003. While progress is unlikely to be rapid given the complexity of the issues at stake and the US 2004 presidential campaign, the ground has been laid for a radical restructuring of international air policy. The industry is clear on the direction it wants governments to follow. “Our purpose is simple,” declared the director general and CEO of the International Air Travel Association in a recent speech in Montreal, “to have our industry recognized by governments for what it is: a mass transit system that provides vital global economic benefits to travelers, tourism and industry. It should no longer be treated as a luxury product catering to an elite. It is an industry that must now be run as a normal business” (Bisignani 2003).

There is an urgent need for the Canadian government and airline industry to conduct a wide-ranging analysis of Canadian options and to develop a consensus on the wisest course to pursue. This analysis could usefully begin with the following three options.

The first option would be to reject any EU proposal for a Canada-EU agreement to replace the current bilateral agreements.19 The logic of the ECJ decision and the ensuing mandate granted to the European Commission strongly suggests that a rejectionist position would not be sustainable, particularly in circumstances where the EU successfully negotiates a single agreement with the US. The member countries of the EU would be left with no option but to abrogate current bilateral agreements with Canada, which in accordance with standard treaty practice and the terms of those agreements they are entitled to do. While the absence of an agreement or agreements would not terminate transatlantic air operations between Canada and Europe, it would make such operations subject to ad hoc approval by regulators unsupported by any governing international legal framework. It should be assumed that Air Canada would object strenuously to any such outcome, since it would not only render the airline’s transatlantic operations subject to the whim of regulators and politicians on both sides of the border, but it would also undermine its alliance relationships, notably those in the EU, which anchor its transatlantic service.

The second option would be to await the outcome of the EU-US negotiations, with a view to indicating readiness to enter negotiations with the EU for the sole purpose of replacing the current nationality provision in the bilateral agreements with an EU-wide provision. Since this step would meet the the ECJ’s principal objection to the current bilateral agreements, it is possible that the EU will be satisfied with this limited approach. Its effect would be to give all EU airlines the best available terms of market access in any of the current bilateral agreements between Canada and EU members. While a detailed commercial assessment of the impact of this step is beyond the scope of this paper, it is reasonable to assume that it would be modest, not least because of Air Canada’s dominance, but also because the access terms of the current bilateral agreements are consistent with the ambitions of the airlines offering transatlantic service. This option would bring negligible benefits to Canadian airlines, travellers or shippers.

The third option would be to propose that the EU and the US invite Canada to the table to negotiate a true transatlantic aviation area. In such a negotiation, it would be in Canada’s interests to embrace the EU approach to the nationality provision, the reciprocal removal of ownership limits and the right to cabotage operations. The purpose of this would be to encourage the flow of new capital into the Canadian airline industry and allow for the right of establishment by foreign investors. The impact would be substantial and on the whole positive. Such an agreement would allow European and US owned airlines to operate domestic services in Canada, the most obvious routes being those that feed and flow traffic to and from the principal Canadian international airports (Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal). European airlines outside the Star Alliance would acquire an attractive alternative to a relationship with Air Canada and the resulting expansion of service would considerably benefit travellers, shippers and airports. Air Canada and all the other Canadian airlines would have the same opportunities in the EU and the US. Where these opportunities would be taken up is less important than the contribution European and US owned and operated services would make to the efficiency of the Canadian marketplace.20 The ultimate result could be the creation of a multilateral framework for the air services from which all stakeholders would benefit.

Canadian airline policy has evolved considerably to effect a transition from a model devoted to the micro-regulation of every aspect of commercial operations to a framework that treats the airline industry as any other industry. While public ownership has been abandoned and proposals for reregulation disappear as quickly as they appear, the view that the airline industry needs to serve a broader purpose than merely responding to demands of Canadians to travel and export and import goods retains some vitality in the government. So too does a curious view of airline economics that justifies the government’s right to find some fares too high and others too low, notwithstanding the freedom accorded to set fares.21 When the current minister of transport deprecates the proposition that foreign investment can contribute to creating a vibrant industry in Canada, his view of airline economics is fully consistent with those of one of his long-gone predecessors, C.D. Howe, who assured Parliament in 1938 that regulation “should have the effect of lowering rather than raising rates by tending to eliminate wasteful and destructive competition among the various forms of transportation” (quoted in Oum et al. 1991, 126).22

Whatever the current cyclical problems of the industry in Canada and other countries, the growth potential of the industry exceeds by a considerable margin the growth potential of the Canadian economy as a whole. Over a recent 12 year period, the increase in traffic was almost double the growth in constant-dollar gross domestic product. The principal source of growth is international traffic (including with the US), where over the same period average annual growth rates were more than double the growth of domestic traffic. These growth patterns are expected to continue in the future (Canada Transportation Act Review Panel 2001). It follows that the principal objective of airline policy should be to permit the Canadian airline industry to adapt to and profit from the inevitable changes in the international aviation policy framework. There is a strong possibility of a sea change in the foundation of the international rules governing air transport. Canada should be at the table when this occurs. The government should urgently abandon its faith in followership and rapidly engage with the European Union and the United States.

The authors would like to thank Paul Dempsey Peter van Fenema, Roland Dorsay and Daniel Schwanen for their comments.

Bisignani, Giovanni. 2003. “Securing Air Transport’s Future.” Speech presented at the Aerospace Congress and Exhibition, Montreal, September 9. Available at www.IATA.org

Canada Transportation Act Review Panel. 2001. “The Airline Industry.” Chap. 7 of Vision and Balance: Report of the Canada Transportation Act Review Panel. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services. Available at www.reviewcta-examenltc.gc.ca

Corbett, David. 1965. Politics and the Airlines. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Dempsey, P. 2001. “Competition in the Air: European Union Regulation of Commercial Aviation.” Journal of Air Law & Commerce 66, no. 3 (summer).

Doganis, Rigas. 1991. Flying Off Course: The Economics of International Airlines. 2nd ed. London: HarperCollins Academic.

——. 2001. The Airline Business in the Twenty- First Century. London: Routledge.

European Commission. 2002. “European Commission Requests the Denunciation of the Bilateral Open Sky Agreements.” Press release DN IP/02/1713, November 20.

European Commission. 2003a. “Open Skies: Commission Sets Out Its International Air Transport Policy.” Press release DN: IP/03/281, February 26.

European Commission. 2003b. “New Era for Air Transport: Loyola de Palacio Welcomes the Mandate Given to the European Commission for Negotiating an Open Aviation Area with the US.” Press release DN:/IP/03/806, June 5.

European Commission. 2003c. “Q&A on the ‘Air Transport Agreements with Third Countries’.” DN: MEMO/03/124, June 5.

Horan, Hubert. 2003. “The EU-US Open Access Area: How to Realize the Radical Vision.” Aviation Strategy 69 (July- August): 2-11.

International Air Transport Association. 2002. “Airlines.” Report available at www.IATA.org

Lazar, Fred. 2003. “Turbulence of the Skies: Options for Making Canadian Airline Travel More Attractive.” CD Howe Institute Commentary 181. Available at www.cdhowe.org

Oum, Tae, William Stanbury and Michael Tretheway. 1991. “Airline Deregulation in Canada.” In Airline Deregulation: International Experiences, ed. Kenneth Button. New York: New York University Press.

Pickerell, Donald. 1991. “The Regulation and Deregulation of US Airlines.” In Airline Deregulation: International Experiences, ed. Kenneth Button. New York: New York University Press.

Reitzes, James D., Dorothy Robyn, Boaz Moselle and John Horn. 2002. “The Economic Impact of an EU-US Open Aviation Area.” Prepared for the European Commission. Available at https://www.brattle.com/

Sampson, Anthony. 1984. Empires of the Sky. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Shane, Jeffrey N. 2003. Speech delivered at the World Air Transport Summit /IATA Annual General Meeting, International Air Transport Association, Washington, June 1-3. Available at https://www.iata. org/agm/2003/sessions/index

Trebilcock, Michael J., and Robert Howse. 1999. The Regulation of International Trade, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

White House. 2003. “Aviation Agreement Fact Sheet” (June 2). Available at www.white- house.gov/news/releases/2003/06/ 20030625-3

This paper was also presented at the Air Policy Forum of the Canadian Airports Council, Toronto, October 30-31, 2003.

William A. Dymond is Director of the Centre for Trade Policy and Law, which is engaged in international trade policy capacity building, research, outreach and publishing. Between 1996 and 1999 he was the chief air negotiator for Canada. He served in several capacities with the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, including ambassador to Brazil, minister-counsellor with the Canadian Embassy in Washington and the Canadian mission to the European Union in Brussels. In Ottawa, his appointments included director-gen- eral of the Policy Planning Secretariat, chief negotiator for Canada for the OECD Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) and senior advisor to the Trade Negotiations Office for the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement.

Armand de Mestral is a Professor of Law at McGill University, holds the Jean Monnet Chair in the Law of International Economic Integration and is Co-direc- tor of the McGill-Université de Montréal Institute of European Studies. From 1998 to 2002 he was interim director of the Institute of Air and Space Law at McGill University. Recent publications include Law and Practice of International Trade (2nd edition, 1999) and The North American Free Trade Agreement — A Comparative Study (Hague Academy of International Law, Receuil des cours, 2000). He has been a panellist in disputes under GATT and NAFTA and is a con- sultant to the North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation.