Over the past three decades the labour market outcomes of immigrants to Canada have declined. Many recent arrivals have had difficulty finding employment, and earnings have gone down, particularly among men. Research has shown that there is no single explanation for this decline, pointing instead to a number of factors such as a shift in source countries, weak language skills, low economic recognition of foreign work experience and the high-tech bust of the early 2000s. In response, the Canadian government has significantly altered the country’s immigration policy. Although labour market outcomes have improved somewhat since the reform, the overall trend has not been reversed. Garnett Picot and Arthur Sweetman review the existing research, discuss recent changes to immigration policy and programs, and present a number of policy recommendations to address these challenges.

Immigration has always attempted to fulfill multiple short-term and long-term economic goals. The 2002 reform of the selection of immigrants under the Federal Skilled Worker Program strengthened language and education requirements, reflecting a focus on the longerterm potential of newcomers’ human capital. More recent policy changes – greater use of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, the Provincial Nominee Program and ministerial instructions – have shifted the focus toward the short term, responding to pressures to fill occupational and skill shortages. The 2002 reform led to some improvements in immigrants’ economic outcomes, and through the Provincial Nominee Program the number settling outside Canada’s three major cities increased. It is still too early, however, to assess the long-term effects of more recent policy changes. The authors therefore conclude that it will be important to evaluate their impact in order to avoid unintended results.

While working to meet short-run goals, policy-makers must also consider the long-run economic outcomes of immigrants and their children and the broad impact of immigration on standards of living. In contrast to adult immigrants, child immigrants and the second generation (those born in Canada) generally have quite positive educational and economic outcomes, with one significant exception: earnings of second-generation members of visible-minority groups are lower than might be expected in light of their high average educational levels. Unfortunately, further discussion is curtailed by the lack of research into some economic issues, notably the impact of new immigration on the economic well-being of Canadians.

The authors recommend several reforms to immigration policy, including reducing immigrant inflows during recessions, selecting younger immigrants, continuing to emphasize language skills, placing employer-sponsored immigration within the context of the longer-term goals, maintaining the focus on highly skilled immigrants (those in the skilled trades as well as college and university graduates) and supporting continued economic success among the children of immigrants.

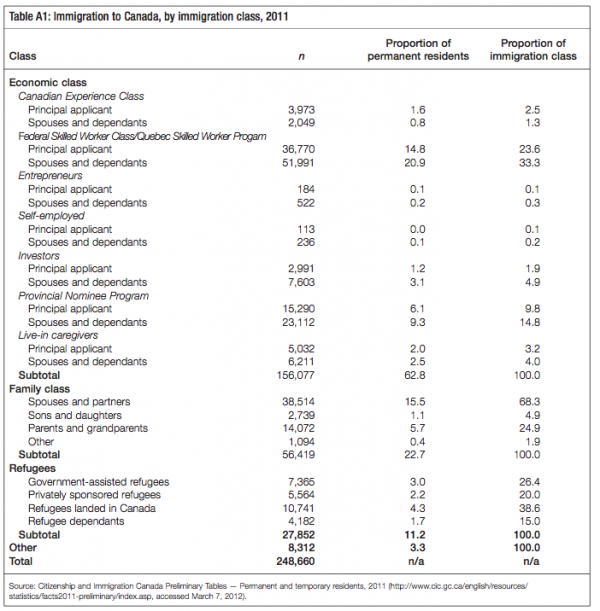

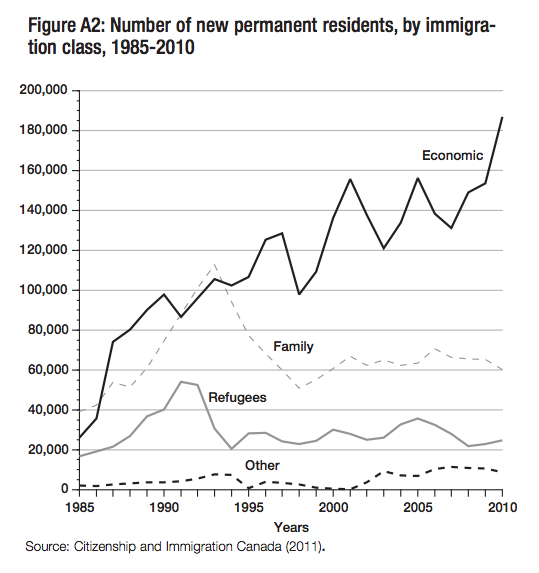

Canada’s immigration system has undergone significant change over the past decade, and that change is continuing at a rapid pace. Traditionally, there have been three main categories of immigration. Most economic class immigrants have entered through the Federal Skilled Worker Program (FSWP) and its Quebec counterpart; they have been selected under a points system that stresses educational attainment, English and French language skills, and work experience.GGGG1 In addition, there have always been some smaller programs under which economic immigrants have entered. Family class is the second category, including spouses or partners, children, parents and grandparents. A smaller share of immigrants enter as refugees, the third main group. The selection criteria for all these categories are well documented and transparent.

More recently, the number of paths for immigration, particularly economic immigration, has increased. In particular, the increasing scope of the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) and its growing share of new immigrants have made the system more complex and the selection criteria less easily understood. Also, an even newer program, the Canadian Experience Class (CEC), is just coming into its own. The FSWP remains a mainstay of economic immigration and was even bumped up in 2010, but its share of the economic class will likely reduce over time to make way for the two newer immigration streams. These three programs are likely to be the main pillars of economic immigration in the future.

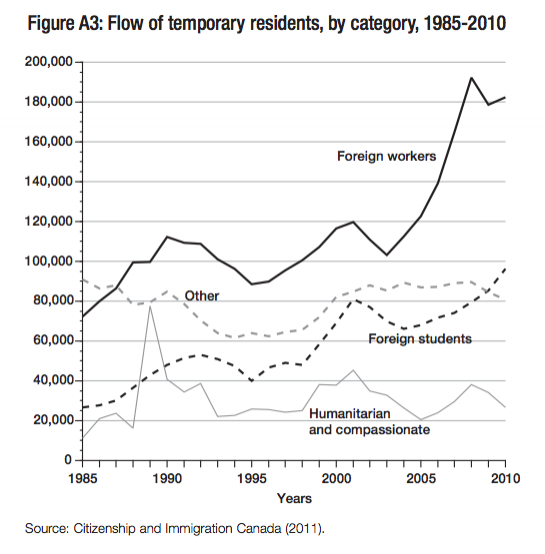

Another major change relates to temporary workers, who constitute a rising share of all immigration. The pressure to bring in more temporary workers in response to labour shortages in selected regions and occupations is likely to increase once recovery from the 2008-09 recession is well underway.

While social, political and humanitarian motives are important drivers of immigration policy development, this study focuses on the economic factors stimulating change in the system. Research over the past quarter century has documented both positive and negative outcomes for new immigrants’ economic integration, and we base our commentary on that research as much as possible. However, there is little Canadian research regarding the economic impacts of immigration on the economy, which limits informed discussion of this aspect of the issue.

The study begins by outlining eight major economics-related issues that have been or, we believe, should be motivating policy direction. Notable among these is the economic integration of immigrants and of their children. Then the study reviews and evaluates recent changes to the immigration system. The final section makes a number of recommendations for improvements to this multilayered and vital system.

A detailed description of the present system, including an outline of the programs included in both the temporary and permanent components of the immigration system, is provided in appendix A. Appendix B examines in depth the decline in employment and earnings and the rise in unemployment and poverty among immigrants.

A number of economic issues, listed below, either are driving the recent changes in the immigration system or, in our view, should be driving further change. Social and political concerns must also be considered in any system revision, but this study focuses on eight economic issues. We elaborate on these eight points in the remainder of the study, outlining recent research, and we conclude by presenting a number of suggestions for change.

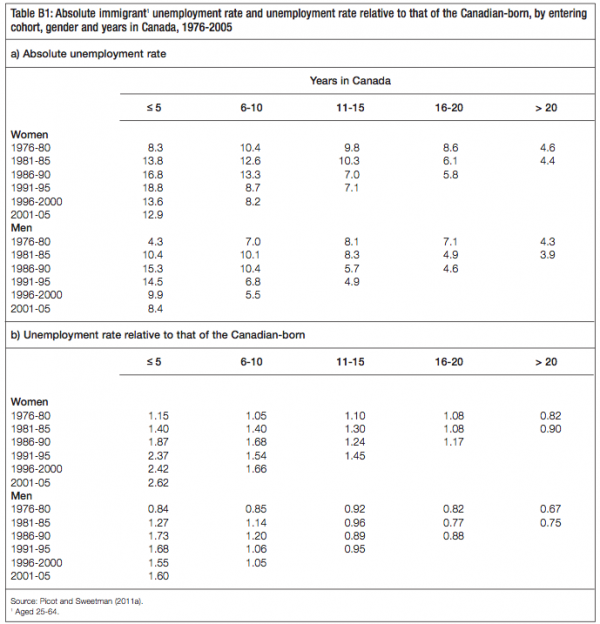

In many immigrant-receiving countries, the labour market outcomes of all categories of new immigrants have declined appreciably. Canada is no exception. This is probably one of Canada’s major social policy conundrums, and it has occurred in spite of rapidly rising educational attainment among new immigrants.3

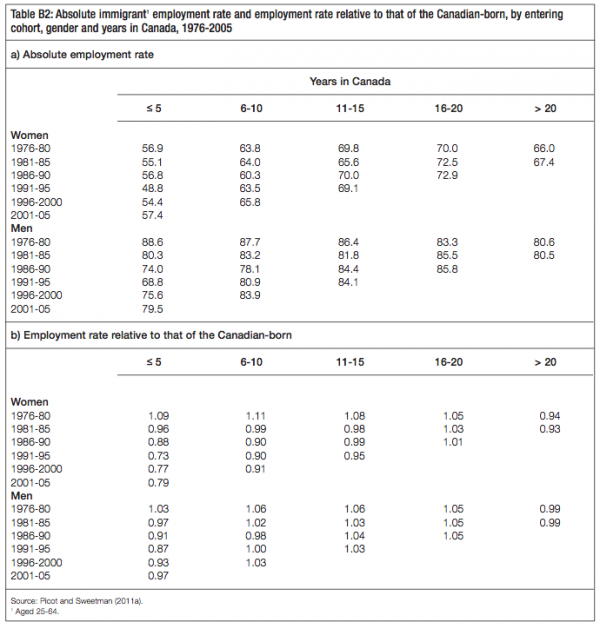

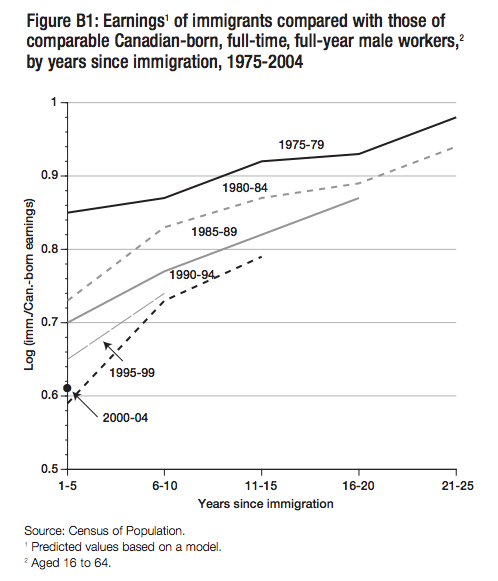

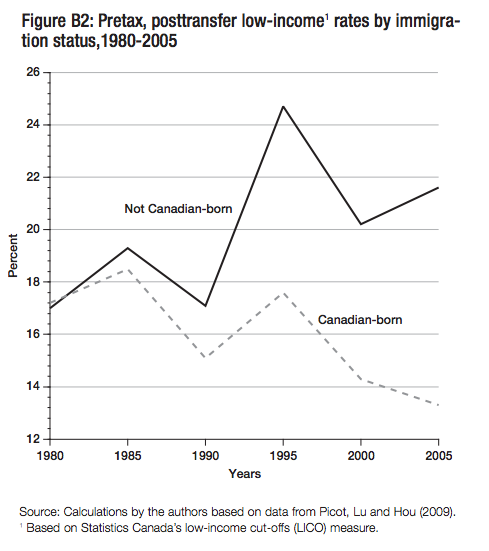

There is a large body of evidence examining how immigrants are integrating economically (see Aydemir and Skuterud 2005; Frenette and Morissette 2005; Green and Worswick 2010; Picot 2008; Sweetman 2010; Sweetman and Warman 2008). The research shows substantial deterioration since the late 1970s. Details on the decline in employment and earnings and the rise in unemployment and poverty, relative to the Canadian-born population, are provided in appendix B. The key points can be summarized as follows:

In order to explain the deterioration in immigrants’ economic outcomes, it is necessary to diagnose the problem. Many Canadian researchers have looked at the decline in relative entry earnings of successive cohorts of immigrants.4 This decline is the cumulative effect of a number of factors (see Aydemir and Skuterud 2005; Green and Worswick 2010; Picot and Hou 2010; for reviews, see Picot and Sweetman 2005, Reitz 2007, and Picot 2008). We will consider these factors in mostly chronological order.

First, during the early stages of the decline in the 1970s and 1980s, changing source countries played a major role. Fewer immigrants were coming from the traditional source regions, notably Western Europe and the United States, and more from Asian, African and Caribbean countries. A bundle of factors that are difficult to disentangle follow from this shift, including differences in language skills, ethnic or racial discrimination, cultural differences, and the quality and Canadian labour market relevance of education.

A second reason for the decline is the significant fall in the economic rate of return to preimmigration labour market experience. The fall occurred mainly during the 1980s and 1990s, but the return continues to be low. In the 1970s persons who immigrated with, for instance, 20 years of labour market experience were remunerated for this experience, as were the Canadian-born. However, the labour market now treats most new immigrants like new entrants no matter how much foreign work experience they have. With the exception of men from traditional source countries — who have also faced a decline in the return to preimmigration experience but on average still receive at least some return — the labour market does not, on average, financially reward such experience at all. Of course, the quantity of preimmigration experience a person has and that person’s age at immigration are closely related concepts. An alternative interpretation of this shift is that, looking at those who arrive as adults and holding education constant, older immigrants used to receive a premium relative to the younger ones and that premium has disappeared (see Schaafsma and Sweetman 2001). Part of this change may be related to baby boom demographics.

Third, and related to the second phenomenon, all new cohorts of labour market entrants, both Canadian-born and foreign-born, have seen a decline in their inflation-adjusted earnings at entry into the labour market, with most of this change happening in the early 1980s. This decline coincided with an increase in labour supply because of the baby boom’s demographics and the recession. Men were more affected than women.

Fourth, after 2000 there was a crash in information technology industries in North America and parts of Europe. A historically high number of entering immigrants were concentrated in computer science and engineering disciplines during the late 1990s and early 2000s as immigration responded — or overresponded — to the need for more workers during the high-tech boom of the late 1990s. During the IT bust of the early 2000s, these immigrants were particularly hard hit. Moreover, immigrants tend to have less seniority and therefore experience more negative consequences in sector-specific downturns. This is an example of the conflict between the frequently short-term nature of employers’ labour demands, which stimulate the immigration of an extremely large number of workers in a narrow field, and long-term national or governmental responsibilities, which continue with respect to those workers (who also have important identities as permanent residents and citizens) after some of the jobs that stimulated the immigration demand no longer exist.

Perhaps most important for current policy is a fifth factor, language skills, which appear to have a direct effect on labour market outcomes as well as influencing the rate of return to formal education. Immigrants with good language skills in English or French can much more easily convert their education to earnings than those without such skills. Recent research (Bonikowska, Green, and Riddell 2009; Ferrer, Green, and Riddell 2006) has shown that the rate of return to English and French language skills is very similar for immigrants and the Canadian-born. Also, when language skills in English or French are accounted for, immigrants and the Canadian-born have statistically indistinguishable rates of return to education. Differences in language skills explain a considerable portion of the earnings gap between immigrants and the Canadian-born. Goldmann, Sweetman and Warman (2011) find that language ability affects the return to educational credentials, with language ability being particularly important for those with higher levels of education.5 Overall, language skills appear to have significant direct and indirect influences on labour market success and are key to positive outcomes.

Much popular discussion suggests that a sixth reason for declining economic outcomes is the difficulty immigrants face in having academic credentials recognized or in upgrading degrees that are not equivalent to Canadian ones. Many federal and provincial government programs for new immigrants address these issues. However, the empirical data suggest that there has been only a modest change in the rate of return to foreign credentials in Canada (for example, Ferrer and Riddell 2008), although there are special issues around the IT collapse in the early 2000s, when the rate of return to higher education fell for many immigrants (Picot and Hou 2009). In general, immigrants do receive a somewhat lower rate of return to pre-immigration education, but this has always been the case and is not a significant source of the decline in labour market outcomes. Furthermore, credential recognition difficulties usually occur in the professions, such as medicine, accounting or engineering. These occupations account for a relatively small share of all immigrants to Canada. Even if credentialing problems disappeared, concerns with low earnings among immigrants would remain. Nevertheless, credential recognition and skill upgrading are real issues for particular groups of immigrants, and this is an appropriate policy lever to pull to improve outcomes even if it did not cause the decline.

Given this body of research, Canadian policy-makers and stakeholders have put considerable effort into improving labour market outcomes for immigrants. They have modified selection rules, strengthened language tests, introduced new programs such as the CEC, increased the share of immigrants in the economic class and bolstered settlement programs. While these changes have resulted in some successes, there has not yet been a marked improvement in outcomes, although it seems likely that current aggregate outcomes would have been even poorer without them. Looking forward, with the IT bust and the 2008-09 recession having passed, it is possible that immigrants’ economic outcomes will improve during the next business cycle upswing. However, an upturn may be delayed, just as it was after the recession of the early 1990s when, as in the most recent recession, the immigration rate was kept high by historical standards. The increasing size of the PNP also adds uncertainty, since the implications of this program for longer-term economic outcomes are currently unknown. The program appears to improve short-term outcomes in particular, since many immigrants have work when they arrive because they are sponsored by employers, but it is too early to assess longer-run effects.

The proverbial “economic pie” for all Canadians grows when new immigrants complement the existing population. That is, they should “fill holes” in the Canadian labour market. One of the most often-stated economic goals of permanent immigration is to fill occupational gaps or skill shortages. Such gaps can be short-term or longer-term. Frequently the gaps are shortterm, associated with (local) business cycle peaks. This was the case with the demand for IT professionals during the late 1990s IT boom and for workers in Alberta during the petroleum boom of the early 2000s.

Unfortunately, the immigration system can have difficulty responding to such gaps for a number of reasons. Obtaining reliable information on the magnitude of occupational imbalances, in either the short term or the longer term, is difficult. Occupational forecasting systems can provide broad guidelines regarding shortages but cannot, generally speaking, accurately forecast future demand for specific occupations (Freeman 2006). Information from observers on the ground (employers and local economists) can assist with very short-run demand, but such demand can change quickly with the business cycle; boom and bust periods are associated with commoditybased industries in particular, where many of the shortages appear. Furthermore, neither forecasting nor the “local informants” approach is capable of accounting for other labour market adjustments that tend to reduce shortages, such as capital investments, occupational wage increases, worker mobility, occupational mobility and training that allows existing workers to move into the shortage occupations. Fundamentally, there is a misalignment between the responsibilities of business and government. While firms can lay workers off at the end of a boom or abandon their obligations as they go into bankruptcy, the nation cannot “lay off” new citizens. The planning horizons and risk profiles of business and government differ dramatically.

Given the transitory nature of many occupational shortages and the long process of admitting immigrants to Canada, federal and provincial governments have difficulty using immigration to meet occupational targets. Therefore, occupational points were removed from the FSWP points system with the introduction of the IRPA in the early 2000s. Some policy-makers believe that provincial governments, being closer to local needs, are better positioned to use occupational targeting. But Carter, Pandey and Townsend (2010) indicate that Manitoba’s Provincial Nominee Program, after initially attempting to target occupational shortages, quickly moved away from doing so given their rapidly fluctuating nature.

Nonetheless, some recent initiatives have addressed occupational shortages. Ministerial instructions introduced in 2008 have recently restricted eligibility for economic class immigration to certain occupations.6 The PNP allows employers with skill shortages to sponsor specific immigrants. Processing speed clearly matters, but even if the PNP and the ministerial instructions are successful in meeting short-term labour market needs (a major benefit), they do not address the fundamental misalignment between the (frequently) short-term employment relationship and the lifetime nature of permanent residency or citizenship.

Another innovation that may alleviate occupational shortages is the CEC, introduced in 2009. Its key objective is to facilitate and encourage the permanent immigration of temporary foreign workers and international students. It is not yet known how the flow of temporary foreign workers will evolve as a result of the incentives built into the CEC, and which groups of workers will elect to immigrate, but this is clearly a renewed effort by the government to identify workers who can fill gaps in the current labour market.

More broadly, some economists argue that immigration policy should not attempt to respond to skill shortages at all (Freeman 2006; Green and Green 1999). Rather, they say, rising wages associated with gaps in the workforce will result in productivity gains from capital investment, more workers moving to regions where they are needed and the reversal of the decades-long slide in the relative wages of less-skilled Canadian workers.

Like most immigrant-receiving countries, Canada has struggled with filling occupational shortages through immigration. The move away from this practice with IRPA a decade ago indicated a lack of faith in occupational projections. More recently some of the ministerial initiatives and the introduction of the CEC suggest a return to this general idea, but the CEC uses a different approach to implementation that relies on on-the-ground information and addresses short-run shortages. (A more detailed analysis of immigration policy and labour shortages can be found in Ferrer, Picot, and Riddell 2011.)

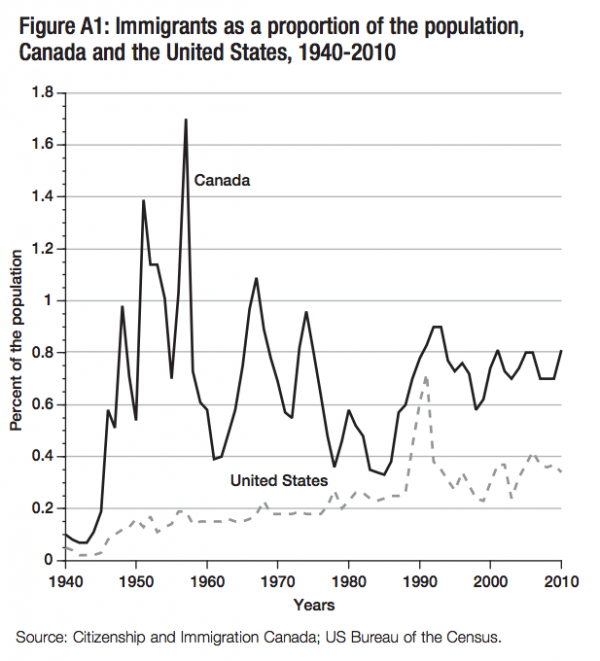

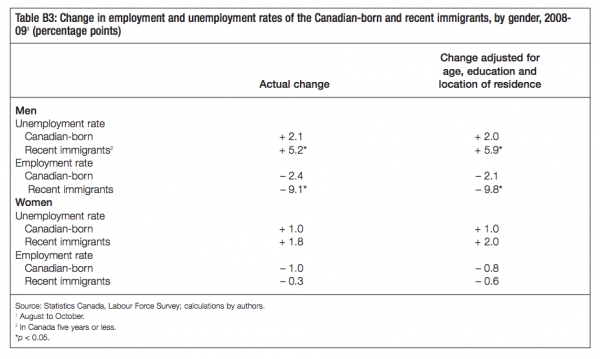

A distinct but related way to maximize the complementarity between new immigration and the Canadian workforce is to time immigration flows to correspond to stages of the business cycle. While such an approach necessarily entails lags, it was used in Canada from the time immigration was reopened following the Second World War until 1990 (with exceptions such as the 1956 Hungarian refugee movement). The idea is to cut back on immigration at points in the business cycle when new immigrants would likely replace rather than complement domestic labour, and to increase immigration when shortages constraining maximum output were more likely. A change in philosophy brought this practice to an end in the early 1990s as the focus turned to long-term economic goals: it was believed that even immigrants entering in recessions would ultimately achieve acceptable economic outcomes and contribute to the Canadian economy. The recession of the early 1990s was the first during which the immigration rate went up simultaneously with the unemployment rate. New immigrants in that period initially had a very difficult time in the labour market. The immigration rate was also maintained during the most recent recession, and even increased in 2010, with the result shown in table B3: during 2008-09, when immigration levels were maintained at a relatively high level by historical standards, economic outcomes (employment and unemployment) among recently entered immigrants deteriorated much more than did those of Canadian-born workers, even after accounting for differences in characteristics that affect such outcomes.

Similarly, but at the level of a sector rather than the whole economy, the IT boom and bust of the late 1990s and early 2000s was also a good example of a cycle when immigration was not reduced as the demand for skills deteriorated. The number of engineers and IT professionals entering Canada rose dramatically in response to the late 1990s boom, but with the bust in the early 2000s these workers saw their earnings drop precipitously (Picot and Hou 2009); the situation was compounded by the large numbers of IT professionals continuing to arrive. More generally, Aydemir and Robinson (2008) show that return and onward migration (that is, the emigration of recent immigrants) has a cyclical pattern, with immigrants who land in relatively strong labour markets being more likely to stay. Also, Beach, Green and Worswick (2011) point out that a stronger labour market is associated with higher skill levels among new immigrants. It is worth noting that those most affected by the arrival of new immigrants are the workers already in Canada who are most similar to the new arrivals — those who are substitutes rather than complements in the labour market — and these tend to be the immigrants who arrived just a bit earlier.

An IRPP study by Carter, Pandey and Townsend (2010) on the Manitoba PNP, which was designed in part to increase the share of immigrants settling in Manitoba, suggests that it did achieve this goal. The immigration rate in Manitoba rose from 2.6 immigrants per 1,000 population before the program to 9.3 by 2008. The short-term retention rate in the province also rose.

During the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, the vast majority of entering immigrants settled in Toronto, Vancouver or Montreal. For example, 77 percent of immigrants entering Canada in 2001 moved to one of these cities. This share declined to 72 percent in 2005 and further to 63 percent in 2010. This decline is related to the implementation of the PNP (CIC 2012). There are of course numerous reasons why immigrants move to the largest cities. Labour market information is key; job growth has been higher in the larger cities than in the rest of the country; and wages tend to be higher in these cities (although so is the cost of living). Once started, these immigration patterns became self-perpetuating: a network of kin and friends attracts more newcomers because of the social and economic support that it provides. Interestingly, Hou (2007) concludes that it is not the overall size of the immigrant community in a city that serves as the major draw for new immigrants, but rather whether they have friends or family in the community. This distinction is important for the discussion at hand, since it means that smaller communities can build on family and friendship ties to attract and retain new immigrants.

Before the PNP was established, smaller communities and provinces argued that the concentration of immigrants in the big three cities impaired their own economic growth and contributed to their falling share of the population. They sought a larger share of entering immigrants in the belief that immigration contributes to rising living standards, is needed to fill occupational shortages and is becoming the major source of population growth.

There was also concern in some quarters that the infrastructure required to socially, economically and educationally integrate immigrants and their families was under considerable strain in the larger cities, and a belief that some dispersion of immigrants would improve integration. In particular, the deterioration in economic outcomes might be arrested by settling more immigrants in smaller cities and communities, where the labour supply has not increased to the same extent and competition for jobs is less. But Warman and Worswick (2004) found that there is little difference among the eight largest cities in the earnings of entering immigrants relative to the Canadian-born and in the relative earnings trajectory of immigrants over time.

They also found little evidence that economic assimilation or integration is superior in the smaller census metropolitan areas compared with the three largest cities. They do find that relative economic outcomes of entering immigrants tended to be better in rural areas than in urban areas.7

Bernard (2008) accounts for differences in characteristics and similarly concludes that, relative to the earnings of the Canadian-born, wages of immigrants are superior in rural and smaller communities compared with the three large urban areas. However, this finding has more to do with the wages of the Canadian-born than with those of immigrants. Workers in smaller and rural areas earn considerably less, on average, than those in large cities. The gap in wages between immigrants and the Canadian-born in rural and smaller communities is explained to a large extent by the lower wages of the Canadian-born in these communities, not by the higher wages of immigrants. Plausibly, smaller communities are more affected by secondary domestic migration following job loss. Immigrants in rural areas may be more likely to depart following job loss, whereas locally born residents are more likely to stay. These questions remain open.

The educational and economic outcomes of the children of immigrants (the second generation) are rarely mentioned as issues to which immigration policy should respond, but we feel that their success or failure is one of the most important concerns.8 As many European nations have learned, much to their chagrin, ignoring the effect of immigration policy on the outcomes of the second generation can have undesirable long-term impacts (see Heath, Rothon, and Kilpi 2008 for a review). In the United States, second-generation outcomes are generally favourable by international standards, but that country is also likely facing declining educational and labour market outcomes among its second-generation immigrants. The role of low-skilled illegal migrants is also an important issue in the US context since these relatively numerous residents have less education and their children may have more limited educational opportunities (see Picot and Hou 2010 and Aydemir and Sweetman 2008 for Canada-US comparisons).

Canada has been fortunate to have experienced very positive educational and economic outcomes among the children of immigrants — among the best in the Western world. While features of Canada’s educational system and the social and policy context within which second-generation integration takes place have contributed to this success, so too have the characteristics of immigrants entering Canada as determined by immigration policy, especially immigrant parents’ educational attainment, residential location of immigrant families, source region and immigrant families’ aspirations for educational attainment. Research has found that these characteristics are important explanations of why the children of immigrants succeed, at least in educational attainment, more than the children of the Canadian-born (for literature reviews see Picot and Hou 2010, and Picot and Hou forthcoming).

Since it takes some time for children to enter the labour market, the research summarized below covers the children of immigrants who entered Canada mainly before the 1980s. Later arrivals have experienced falling economic outcomes, and there is some concern that outcomes for their children are in jeopardy. However, we believe that, if anything, second-generation outcomes in Canada will improve, not deteriorate, in comparison with those of the third-plus generation (that is, Canadians whose parents or earlier ancestors were born here).

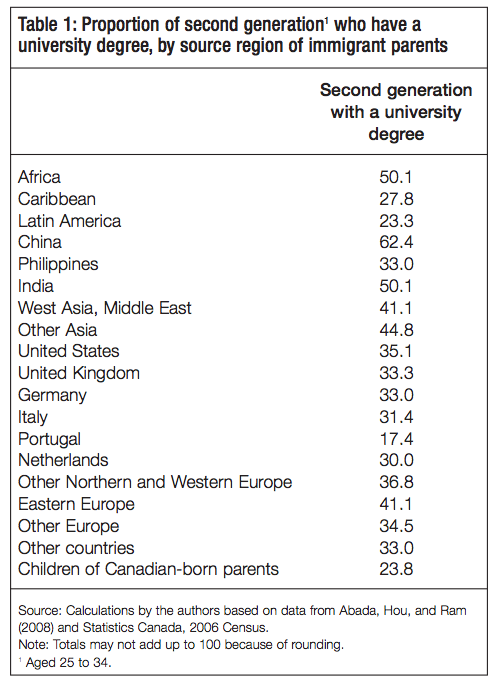

Second-generation Canadians have a significantly higher level of educational attainment than third-plus-generation Canadians. According to the 2006 census, 36 percent of the children of immigrants aged 25 to 34 held degrees, compared with 24 percent of the third-plus generation. Furthermore, children with two immigrant parents have more education than those with only one immigrant parent (Hum and Simpson 2007; Aydemir and Sweetman 2008). This higher achievement level is most noticeable among second-generation members of visible-minority groups (Boyd 2002; Aydemir and Sweetman 2008). There is significant variation among nationalities, with the Chinese, Indian and African second generations registering the highest educational attainment (table 1; Abada, Hou, and Ram 2008). However, very few nationalities among second-generation Canadians register lower educational levels than the third-plus generation, at least when measured by the share of children who attend university. A smaller share of children in the second generation than in the third-plus generation attend colleges, but overall, a higher share acquire some form of post-secondary education. As compared with the third-plus generation, the focus of the second generation is on university rather than college and the trades.

Recent research has revealed a number of reasons why the second generation is better educated than the third-plus generation. Immigrants to Canada are more highly educated than the population as a whole. Early research suggested that this higher education among immigrant parents accounted for about half of the second generation’s educational edge over the third-plus generation (Boyd 2002; Aydemir and Sweetman 2008). More recent research suggests that higher parental education may work through other variables, such as higher aspirations for educational attainment, and that once one controls for such aspirations, the effect of parental education is much reduced (Childs, Finnie, and Mueller 2010; Picot and Hou, forthcoming; Finnie and Mueller 2010). Location of residence is important, as the second generation lives disproportionately in large urban areas, where educational attainment is higher. “Ethnic capital” (the tendency of young members of an ethnic group to have advantages associated with more highly educated role models in the group, more group economic resources and useful networks) plays a role, accounting for perhaps one-quarter of the gap (Abada, Hou, and Ram 2008). Even second-generation students who performed relatively poorly in secondary school are highly likely to continue to the post-secondary level, usually university (Picot and Hou, forthcoming). This pattern is particularly evident among Asian-background families.

Nevertheless, much of the educational attainment gap persists even after one has adjusted the data for all of these effects. This points to some unmeasured factor, perhaps cultural, driving second-generation educational attainment, especially among those with Chinese and Indian immigrant parents, two of the larger immigrant groups in Canada in recent decades.

Aydemir, Chen and Corak (2009) find that immigrant family income has little to do with the educational attainment of second-generation children. This is important, as there is some concern that the decline in earnings among immigrant families entering Canada since the 1980s might harm the educational attainment of their children in the future. However, since parents’ education is a stronger predictor of the educational attainment of their children than is income, and since the educational attainment of immigrants has risen dramatically since the 1980s, it seems likely that educational outcomes will rise, not fall, among the second generation of recent immigrants.

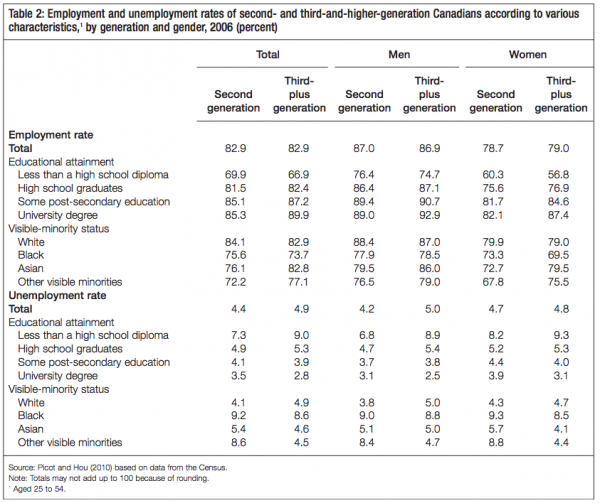

One would expect labour market outcomes to reflect the significant educational advantage held by the second generation over the third-plus generation in Canada, and, in the aggregate, they do. Unadjusted (raw) employment and unemployment data suggest that, on average, the children of immigrants are doing as well as, or better than, the children of Canadian-born parents (table 2). The employment rates of children of immigrants and those of the third-plus generation are similar. As well, unemployment rates are lower among the children of immigrants than among the third-plus generation. And the occupational data reflect the second generation’s educational attainment and focus on university. Secondgeneration members who are employed are more likely to be in professional occupations and less likely to be in blue-collar occupations than the third-plus generation. About 30 percent of second-generation workers were in professional and related occupations in 2006, compared with one-quarter of the third-plus generation (Picot and Hou, forthcoming).

Furthermore, in the unadjusted (raw) data, earnings of the second generation among the employed are, on average, 9 to 13 percent higher than earnings of the third-plus generation (Aydemir, Chen, and Corak 2009; Hum and Simpson 2007; Aydemir and Sweetman 2008). However, these data mask important differences within subgroups of the second generation. Unemployment data suggest greater employment difficulties among second-generation members of a visible-minority group. Unadjusted unemployment rates are higher among Asians, Blacks and “other” visible-minority groups than among White third-plus-generation members, or even among their third-plus-generation visible-minority counterparts (table 2).

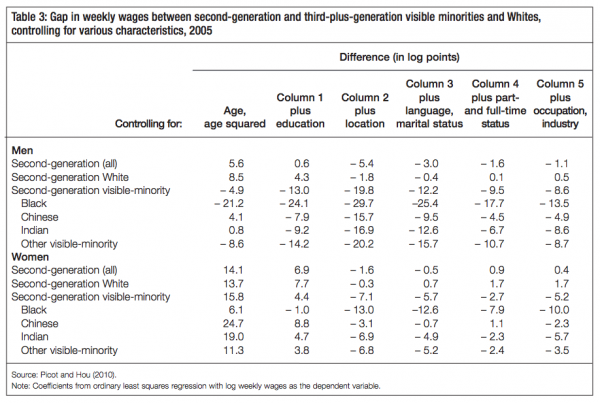

Members of second-generation visible-minority groups earn less, on average, than White thirdplus-generation members, accounting for background differences. Picot and Hou (2010) use 2006 census data to focus on the earnings gap for a number of visible-minority groups. Consistent with the research mentioned in the previous paragraph, they find that, for the entire relevant male population, second-generation men have weekly earnings 5.6 percent higher than those of the third-plus generation, with controls for age only (table 3). However, this wage gap is driven entirely by White second-generation Canadian men, who have an 8.5 percent lead over their third-plus-generation counterparts. Visible-minority men are 4.9 percent behind, in spite of the fact that they have higher educational attainment than White secondand third-generation Canadians. In addition, there is significant variation among visibleminority groups: Blacks have the largest gap (21 percent behind), whereas Chinese men have a lead among these groups. This result adjusts the data for age differences only. But there are other important differences between groups: after adjustments for personal and job-related characteristics, the data show that second-generation visible-minority members earn 4.9 to 13.5 percent less, depending upon the group, than White third-plus-generation workers.

A similar phenomenon is observed by Aydemir and Sweetman (2008) for the second generation overall. Comparisons using only age and sex groups showed second-generation Canadians having higher earnings than the third-plus generation, but once statistical controls for education and geographic location are employed, the gaps are eliminated or reversed. Second-generation Canadians appear to receive a slightly lower earnings premium for their educational attainment and urban character. However, the magnitude of these gaps is not enormous for most groups either conditional on characteristics (where they are negative) or unconditionally (where they are positive) — especially when compared with the enormous deficit among first-generation immigrants. Overall, the children of immigrants have very strong labour market outcomes.

It may be that economic integration is a multigenerational process. The earnings gap for visible minorities (relative to White third-plus-generation Canadians) is reduced across generations; it is greatest among the arriving immigrants, decreases with the second generation and falls even more among the third (Skuterud 2010; Dicks and Sweetman 1999). This pattern may be related to a long-term acculturation process and adaptation within the receiving society.

Although it has varied in scale, an application backlog has long existed. In recent years Canada has received on the order of 450,000 applications each year in all categories, granted 250,000 admissions and observed approximately 100,000 unsuccessful files, leaving an excess of 100,000 applications per year to be added to the backlog. These backed-up applications are far from homogeneous. Even though modern technology is allowing a move away from a scattered system, where queues were handled by local embassies or processing centres, to centralized application processing that is mostly located in Canada, there remain many distinct queues. Various classes are processed with different priorities (for example, spouses and PNP nominees have priority), and ministerial instructions have also prioritized (and then reprioritized) certain applications within the FSWP.

While there is little research on this topic since data are not available, it seems plausible that better management of the application backlog could lead to improvements in economic outcomes associated with immigration by increasing flexibility in selection. Crucially, the existence of a backlog prevents the selection system from operating nimbly. If there is any value in addressing short-term skill shortages, then processing times in at least the FSWP and the PNP need to be kept quite short.

Apart from improving the queue for management purposes, there are several important economic issues regarding the backlog that are not well understood. In particular, the length of time in the application queue may affect immigrants’ labour market outcomes after they do arrive. Also worth considering is the cost to Canada’s reputation of discouraging immigrants who have options among a variety of receiving nations.

What is the appropriate level of immigration to achieve economic goals? There is virtually no research in Canada asking whether immigration levels or the contribution of immigration to labour supply played a role in the decline in immigrants’ economic outcomes, particularly among the highly educated. Some argue that the decline itself is sufficient evidence to demonstrate that levels were (and are) too high. But many factors other than labour supply may explain the decline. Researchers have been able to account for virtually the entire decline in immigrants’ earnings at entry without resorting to labour supply explanations.

However, research about the IT bust did demonstrate that a mismatch in occupational supply and demand lowers immigrants’ economic outcomes disproportionately. When demand was high in the late 1990s, employers may have ignored the language skills and the educational quality of prospective employees and may have accepted workers who were not ideally matched to job openings. But when demand fell in the early 2000s, earnings among immigrant IT workers fell much more than among their Canadian-born counterparts. This observation fits with the evidence indicating that immigrants are harder hit during a recession, when demand falls (or labour supply is high). Such processes could have occurred among immigrants as a whole, resulting in declining earnings. At present there is little research about this issue one way or the other.

Determining appropriate levels for the future is even more challenging than pinpointing the effect of labour supply in the past. Observers such as the Conference Board of Canada (2007) have been issuing highly publicized warnings of a looming broad-based labour shortage associated with the aging of the workforce and increased retirements. Some are calling for increased immigration levels in response (Conference Board 2007). But others are skeptical that such a shortage will develop (Freeman 2006), in part because of the inability of forecasters to adequately take into account the various forms of adjustment that will take place. The forecasts that do exist put the labour shortages a decade or more away. These forecasts, even if they prove to be reliable, are not particularly compelling evidence on which to base adjustments to current immigration levels.

Further, a distinction needs to be made between increasing immigration levels and targeting a demographic shortage. To date, the age profile of immigrants has accentuated rather than alleviated the demographic bulge of Canada’s baby boom. As surveyed in Sweetman and Warman (2008), increasing immigration levels while maintaining the current selection policy would have little effect on overall population aging.

Closely related to the issue of immigration levels is the aggregate economic effect of immigration. Does immigration increase the economic well-being of Canadians? This question is frequently addressed by measuring (inflation-adjusted) GDP per capita, although many studies also look at the labour market impacts of immigration.9 There is little Canadian evidence on the subject, even though it is one of the most important questions in the immigration domain.

Overall, inferences based primarily on research in other countries suggest that immigration results in a very small change in GDP per capita, and although some studies do observe a negative impact, any change is probably positive. For example, Ottaviano and Peri (2008, forthcoming) suggest that the typical American-born worker in the United States gains about 0.6 percent in GDP per capita because of the cumulative total of immigration between 1990 and 2006; a relatively small gain, but not a loss. However, such a conclusion may or may not apply to Canada, since the types of immigrants entering the two countries are very different (Canada has put more emphasis on high skills) and the economies diverge on a number of other dimensions (such as social and health policy). Furthermore, the benefits can be very heterogeneously distributed and subgroups may face substantial gains or losses.

While there is little direct research on the overall impact of Canadian immigration, a few research papers have been produced recently. One approach focuses on the labour market and seeks to establish whether new immigration affects the wages of the existing population. Aydemir and Borjas (2007) apply a consistent methodology to Canada, the United States and Mexico using census data, although there is some debate about the structure of the model they employ. They find that Canada’s emphasis on skills has reduced income inequality in the country by slightly reducing the wages of high-skilled workers relative to those with fewer skills. They observe the opposite occurring in the United States (where immigrants are primarily low-skilled, so that the wages of low-skilled workers are bid down, increasing income inequality). Mexico, in contrast, experienced net emigration with departures among the domestic mid-skill-level workers being the most likely. This was associated with relative wage increases for this group.

Closely related research by Tu (2010) looks at Canada using census data and a similar methodology, but with the modification that he compares across distinct geographical regions. In some specifications Tu finds negligible effects of immigration on the earnings of the domestic workforce, and in others small and positive effects. However, when he, like Aydemir and Borjas, looks at the nationwide picture, he also finds small negative impacts on earnings. This difference in outcomes — depending upon whether one divides the country into regions or cities or looks at the nation as a whole — is similar to that observed across studies in the United States.10

Dungan, Fang and Gunderson (2010) use a different approach that introduces immigration into a macroeconomic model of the Canadian economy. Predicting the outcomes if 100,000 immigrants more than the current level were to arrive each year from 2012 to 2021, they trace out the simulated results for that 10-year period.11 Using parameters that describe the current Canadian situation, they observe that this increase in immigration would be associated with an increase in inflation-adjusted GDP of 2.3 percent. However, the additional immigration would increase the population by 2.6 percent, so GDP per capita would decline slightly. Unemployment would not be affected, and government fiscal balances would increase slightly. If the parameters are changed so that new immigrants do not have earnings levels at entry that are lower than those of their Canadian-born counterparts, real GDP per capita increases. However, to provide some context, in the modern era for which data are available, immigrant earnings at entry have never been equal to those of comparable Canadian-born workers, even in decades where immigrants had the best outcomes on record. This result is, nevertheless, useful in that it points out the economy-wide importance of public policy aimed at improving new immigrants’ labour market outcomes.12

Overall, evidence on the economic impact of immigration in Canada is best viewed as preliminary. It suggests that immigration has a very modest impact on measures such as GDP per capita and the government’s balance sheet, although whether it is positive, negative or zero is open for debate, with most observers favouring “small positive.” This conclusion is consistent with an older literature, surveyed by the Macdonald Commission and the Economic Council of Canada, and discussed in Sweetman and Warman (2008). However, it also seems clear that the nature of the impact depends upon the structure and operation of the immigration selection and settlement services systems.

Changes made by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) to the immigrant selection process in the early 1990s increased the average educational level among immigrants, grew the share of skilled immigrants admitted through the economic class, and raised the number of IT workers and engineers coming to Canada. Research suggests that these changes did improve wage levels among entering immigrants in the late 1990s (Picot and Hou 2010).

Since that earlier set of revisions, there have been several more changes to Canada’s immigrant selection system. The more important ones include the following:

The IRPA was phased in over the early to mid-2000s, since immigrants were admitted under the rules in operation when they applied and there was a substantial application backlog. One of the key features was a modification of the points system for principal applicants under the Federal Skilled Workers Program. A recent CIC evaluation (2010) convincingly concludes that the IRPA improved labour market outcomes, particularly with its increased emphasis both on knowing one of Canada’s official languages well and on education. The evaluation also observes that preimmigration offers of employment are predictors of good short-term labour market outcomes. The economic outcomes of spouses are also likely to be positively affected by improvements to the FSWP, since the better the qualifications of the principle applicants in terms of education, language skills, and so on, the better the outcomes of the spouse (Sweetman and Warman, 2010c). This probably stems from the tendency of “like to marry like.”

The Canadian Experience Class allows some skilled temporary foreign workers and former international students to apply to become permanent residents (see Sweetman and Warman 2010a; Warman 2010). By attracting those who have already (presumably) experienced success in the Canadian labour market and whose skills are in demand, by imposing a language test and (for former foreign students) by ensuring that education has been in Canadian institutions, the program aims to alleviate difficulties that many recent immigrants have experienced in transferring their preimmigration human capital.13 It is too soon to evaluate this program, however.

Many observers argue that French or English skills are directly essential to labour market success in Canada and also indirectly affect the transfer of other skills and educational credentials to the Canadian context. (See especially Ferrer, Green, and Riddell 2006; Goldmann, Sweetman, and Warman 2011.) A relevant recent change was to require formal language testing for all new immigrants entering under the CEC.14 The CEC language assessment tool is the same as that for the FSWP, but the test scores are applied differently. The CEC sets a high benchmark in a single official language that is an absolute requirement; for the FSWP, medium scores in both official languages may be acceptable, or low points in language can be offset by high points in other categories. These are very important differences that may have an impact on labour market outcomes; however, it is too early for empirical analysis.

The framework for the ministerial instructions provided in the 2008 budget constitutes the most important recent innovation. As of fall 2011, CIC has issued four sets of instructions that have significantly changed immigration policy. These apply mainly, but not exclusively, to the FSWP. First, although occupational points had been eliminated with the introduction of the IRPA, the ministerial instructions reintroduced occupation as an element of selection but with a new approach. Before the IRPA, occupation was simply an element in the points system; today occupation is a preliminary screen. Unless they have Canadian job offers in hand, new applicants who do not qualify for the posted list of occupations in demand are not eligible for processing; their files are returned and their application fees refunded. In contrast to the pre-IRPA system, under the new approach there is no fixed timetable for updating the list of approved occupations. The new approach is thus not attempting to respond to very short-run fluctuations in demand. One apparent rationale for the initial brief list was to limit applications and reduce the backlog, but this tactic did not work as expected; the posted list of occupations stimulated applications instead since it was taken to be signalling strong demand in the listed areas. Subsequent instructions therefore imposed and then reduced caps (quotas) for each of the occupations for which applications are permitted. Only 1,000, and then 500, persons were permitted in each category in each year, and the process was first come, first served. The caps were intended primarily to manage or reduce the massive backlog by discouraging applicants, but they may have beneficial economic implications as well: by (eventually) eliminating the backlog, the selection system will be able to respond more quickly to changing conditions and new information.

The immigration system has responded to many of the issues outlined in this study: notably the deterioration in economic outcomes of immigrants, short-term and longerterm occupational and labour shortages, and the regional distribution of immigrant settlement. The application backlog is so far being addressed primarily through ministerial instructions. Policy has not responded to the lack of connection between immigration levels and the business cycle, and it does not typically explicitly consider the economic outcomes of the children of immigrants.

Some advances have been made in the three areas where program changes have been focused. The shift toward more highly educated immigrants in the economic class improved outcomes in the late 1990s, and the IRPA changes of the mid-2000s significantly enhanced the economic outcomes of immigrants entering under the FSWP. Introducing the CEC and changing language testing also aimed to serve this purpose, at least in part, and it seems credible that these changes will be successful. Second, a smaller proportion of immigrants now settle in the three largest cities than in the 1990s, thanks in part to the Provincial Nominee Program. And finally, although there is no concrete evidence of which we are aware, it is likely that the rise in temporary workers in skilled trades entering under the TFWP in the early 2000s in particular did help alleviate short-term occupational shortages in some industries and regions. (The impact on the wages or employment rates of Canadian workers is also yet to be studied.) Similarly, the occupational restrictions and quicker processing time for selected new applicants brought about by the ministerial instructions focus the FSWP on serving short-term needs, thereby also improving labour market outcomes.

However, this does not mean that Canada has achieved the optimal policy orientation. In particular, immigrant economic outcomes remain an area of concern in Canada as well as in most Western immigrant-receiving countries. Relative to those of the Canadian-born, the earnings levels of recent immigrants remain far below levels among those entering before the 1980s.

A key goal going forward will be getting the right balance between what are now the three major legs of the newly reconstructed economic class: the FSWP, the CEC and the PNP. Ministerial instructions are also useful tools for adjusting the system on an ongoing basis in a timely manner, but gaining experience with and feedback on their operation will be important.

Selection under the CEC is on a pass/fail basis, which contrasts sharply with the points system in the FSWP. The differing approaches highlight that there are alternative ways to understand and measure “high skills.” Defining and evaluating such skills in a points system is transparent and in some sense equitable, but it is not straightforward. Implicit predictions of long-run labour market success are not always accurate; and, more fundamentally, nominally similar attributes for which the same points are awarded may not be very similar in practice. For example, the existing points system treats all bachelor’s degrees — regardless of, for example, field of study and university — as equivalent, whereas the labour market treats these educational qualifications as varying and rewards them accordingly. In a system based on presenting credentials, detecting fraud is also an ongoing struggle. By comparison, the CEC defines high skill based on the nature of employment actually obtained in Canada — that is, by success in obtaining and retaining “high skill” employment — and also imposes a language test, which is crucial to employment flexibility in a dynamic labour market. Of course, this approach also has its problems, since evaluating the occupational status of a job is notoriously difficult. Therefore fraud may also be a complication in this context.

Operating both approaches in parallel has substantial appeal since they address somewhat different markets in terms of both the supply of potential immigrants and the demand for specific skills by employers. Over time, comparisons between the two will be fruitful in promoting incremental improvements on both sides.

The first province to use the Provincial Nominee Program was Manitoba. It has since expanded to all provinces and territories except Nunavut, which relies on the federal system, and Quebec, which has its own economic class selection system. These programs effectively permit provincial and territorial governments to operate their own immigrant selection systems. Inasmuch as provinces are “closer to the ground” and able to identify and recruit immigrants who are better fits for local needs than those selected by the federal government, and inasmuch as they are able to retain such immigrants, the overarching program has merit. On the other hand, if provincial entry standards are lower than those of the federal government, and especially if immigrants are not retained locally, then the PNPs can become a national gateway, bringing immigrants into the Canadian labour market as a whole. Pandey and Townsend (2011) explore this issue, as well as looking at immigration rates across provinces. They find, as did a CIC (2012) evaluation, that the PNPs have been successful in increasing immigration rates to smaller provinces. Regarding retention rates, CIC (2012) found significant provincial variation. Among provincial nominees entering between 2000 and 2008, only 56 percent of those going to the Atlantic provinces were still in the province of entry in 2008, compared with 95 percent in Alberta and British Columbia.15 Such variation is related at least in part to economic outcomes, which were better in the West than in the Atlantic provinces. Clearly, these are important issues that need more attention as these programs age and expand. Regular monitoring of longer-term retention rates would be especially valuable. In fact, CIC would do well to include provincial retention rates for 1, 5 and eventually 10 years after immigration in its annual Facts and Figures publication.

An often-stated concern (for example, Alboim 2010) is that the criteria governing the selection of immigrants in some of the PNP entry streams are not stated precisely and transparently. Such uncertainty makes the application process for prospective immigrants more difficult, and keeping track of the various selection rules increases the value of immigration consultants and lawyers since the process has become so much more complex.

The CIC evaluation (2012) concluded that short-term economic outcomes overall were quite positive, although there was tremendous variation by province. About 80 percent of the immigrants entering under the PNP were employed at some time during their first year in Canada, but this rate varied from 50 to 75 percent in the Atlantic provinces to around 95 percent in the western provinces. Average earnings after one year also varied tremendously, from $23,000 to $47,000 in the Atlantic provinces to $70,000 to $80,000 in British Columbia and Alberta.16 Among immigrants entering between 2000 and 2007, earnings and employment rates during the first year were higher for PNP participants than for their FSWP counterparts. While employment rates remained marginally higher among the provincial nominees over the longer term (five years), earnings equalized around the third year, and after five years the federal skilled workers were earning $2,000 to $7,000 more annually. This highlights the importance of measuring both short-run and longer-run — ideally after 10 or 15 years — outcomes. It is also worth noting that the PNP has had priority processing since its inception; since the FSWP has not historically had such prioritization, this affects the interpretation of comparisons of the short-run outcomes of the PNP and the FSWP.

CIC’s PNP evaluation noted two issues of relevance to this discussion. The first relates to language requirements, an important component of successful social and economic integration. While the FSWP and the CEC have explicit and fairly strenuous language requirements, the evaluation noted that there is no consistent standard in the PNPs regarding language ability. The second relates to meeting skill shortages. Meeting labour market needs and skill shortages were the two program objectives most often cited by provincial officials. However, only one province had a formal evidence-based labour market strategy that linked labour market shortages to immigration levels. Most relied on dialogue with employers, industry associations, regulatory bodies and chambers of commerce. The CIC evaluation found that labour shortages were not well documented in most of the provinces. As we note elsewhere, obtaining relevant and useful information on either short-run or long-run general labour market or skill shortages is very difficult. When interviewed, however, employers tended to state that the program had assisted them with their labour market shortages.

One important question going forward is the scalability of the provincial nominee programs — to what degree they can be expanded. There are two dimensions to the question. First, provinces may have limited capacity to attract and retain immigrants; second, it might well be that only the first immigrants arriving under these programs have excellent outcomes, since the initial openings that a province fills are quite valuable (so-called “low-hanging fruit”). Over time, the highvalue gaps in the market that the province is able to identify may decline in number. The PNP may be overexpanding or expanding too quickly. There is some indication to this effect in the study of the Manitoba program by Carter, Pandey and Townsend (2010). Moreover, since the PNP continues to evolve very quickly, it is not yet possible to evaluate medium-term outcomes for those who entered under the program. There is nevertheless a need to proceed with caution.

Ministerial instructions are intended to serve a dual purpose: reducing the number of applications and hence the backlog; and targeting immigration toward particular occupations. The pre-IRPA legislation did not relieve occupational shortages well for a number of reasons (see Ferrer, Picot, and Riddell 2011), including very long processing times. Ministerial instructions now provide for priority processing of applicants in selected occupations. This measure is a novel approach for Canada, since it addresses not only entry criteria but also processing priority or speed. The success of this new management tool is yet to be determined, but it holds promise for meeting targeted labour market needs.17

The second and third sets of ministerial instructions imposed and then reduced caps on each occupational category, thereby limiting the number of applications for admission that would be accepted each year. These caps were imposed to deal with not only the existing backlog but also the large excess in annual applications over acceptances.

When the IRPA was introduced, the intention was to manage the backlog in the FSWP by adjusting the minimum points required for entry. Most people would agree that it is unfair to change the points threshold for a particular application after it is submitted. But with appropriate advance notice, the points cut-off could be adjusted annually for each coming year (much like the exercise at present where the Minister tables annual target admission levels in Parliament). However, this measure was never implemented, and the caps set by ministerial instructions are the new backlog management tool.

Although a cap may be an important backstop, and it certainly limits the number of applications, it is not necessarily the best first-line response since it does nothing to remedy the drop in labour market outcomes of new immigrants. Raising the points threshold would address this issue by producing better-qualified applicants. Sweetman and Warman (2009) show that labour market outcomes improve as points totals rise past the cut-off and that there is no rationale for the current threshold as opposed to a higher one. Further, the weight given to the various elements of the points system and the way the elements are selected are not optimal and should be evaluated and revised from time to time. In particular, adjusting the points assigned for age would be useful given Canada’s demographics and impending baby boom retirements.

Governments should not address the backlog in isolation from other important immigration policy issues. That said, adjusting the FSWP points threshold on an annual basis has the potential to address two issues simultaneously. It would also be a return to what was originally envisioned for the IRPA.

Immigration policy is clearly a very complex topic, and thus far we have surveyed the research and context, discussed some ongoing challenges and pointed to a few possible future directions. Here we build on this foundation to outline other key recommendations.

The shortage of research and informed discussion on immigration levels and the effect of immigration on Canadians’ living standards was pointed out earlier. These are difficult areas of research, and that fact no doubt explains to a considerable extent the present shortfall. Nonetheless, these two issues are key parts of immigration policy and should be addressed directly in the research and policy communities.

Research reviewed earlier showed that during recessions, economic outcomes deteriorate more among recent immigrants than among the Canadian-born. Reducing immigrant inflows in recessions or shortly thereafter restricts labour supply in a period when labour demand is falling. It also helps prevent longer-run economic “scarring” that can occur when new labour market entrants are unable to obtain jobs or are unable to practise their skills over a long period.

Reimplementing the procyclical policy on immigration levels of the type that was in place in Canada until the early 1990s would probably improve immigrant economic outcomes. Longer-run immigration targets would replace annual targets. Ideally, such targets would cover not any predetermined time span but the flexibly defined length of a business cycle, as was done historically. Beyond adjusting total immigration levels to the business cycle, it is also feasible to adjust the composition of the flow to the business cycle. Family class immigration, which is less sensitive to the business cycle and includes persons who should be admitted for noneconomic reasons, could increase in relative terms in recessions and decline in booms, while the various elements of overall economic class immigration do the opposite. These shifts would smooth the administrative burden across the business cycle. Any such changes over the business cycle or changes in the size of the family class in general would primarily affect parents and grandparents since spouses and partners are given processing priority. Some might argue that it is too difficult to alter flows quickly enough to keep targets in line with the economic indicators, which also lag behind the facts they measure. But even before computerization-aided data collection and communication, this approach was successfully undertaken.

Research indicates that a decline in the value of foreign work experience was one of the major causes of the deterioration in immigrants’ economic outcomes. Put another way, adult immigrants who are younger when they arrive, on average, do better economically than those who arrive at older ages (Schaafsma and Sweetman 2001). Children and young adults are also more likely to obtain Canadian education or accreditation, thereby further improving their outcomes. Boulet and Boudarbat (2010) look at the interaction of age on arrival and Canadian education, finding independent positive effects on employment for each. Furthermore, although immigration cannot on its own prevent a rising old-age dependency ratio as the number of retirees increases relative to the working-age population, a focus on immigrants born in the trough between the baby boom and the baby boom echo (between the mid-1960s and the mid-1980s) can move the dependency ratio in the right direction.18

In practice, the two goals of reducing the dependency ratio and focusing on younger workers may at times be in conflict, since selecting “young” people born at the peak of the baby boom echo would achieve the second goal, but not the first.19 Although Canada already missed key opportunities when these two goals were aligned, an increased focus on attracting immigrants of specific desirable ages — through changes to the points system in the FSWP and to the selection systems of the PNP and the CEC — would assist in meeting economic goals related to immigrant outcomes and the dependency ratio. Where there is a conflict between demographic and age criteria, targeting younger immigrants rather than those who would reduce the dependency ratio is probably the primary concern, with a larger economic effect.

Differences in French or English language ability between immigrants and the Canadian-born are another major explanation of the gap in wages between the two groups. One earlier paper found differences in language skills in English or French accounted for more than half of this gap (Bonikowska, Green, and Riddell 2009). Language skills have a strong influence on the value of formal education and probably other forms of human capital as well. The lack of strong skills in a Canadian official language can prevent a newcomer from converting education, in part or in full, into earnings; and high-level language skills can increase the value of highly skilled human capital — in the extreme, giving it some value when it would otherwise have none — in the Canadian labour market. Higher levels of language or literacy skills are required for persons with higher levels of education or who are working in more complex occupations. A continued focus on language ability is essential to improving economic outcomes.

CIC has moved to implement language tests for principal applicants in the FSWP and the CEC. Language ability is a criterion in some of the PNP streams, although, as noted in the CIC evaluation (2012), there is no consistent language requirement in the PNPs of various provinces and territories, as would be desirable. Given the central role of language for the economic outcomes under discussion, and the increased importance of the PNP, improved outcomes are likely to follow from minimum national standards for the PNP. (This idea could be extended to other characteristics but seems most crucial for language.) This need not imply a simple single threshold; instead, standards could be flexibly related to education and/or occupation and recognize that entry into certain occupations and the use of more advanced educational credentials have higher language requirements. Of course, such policies would affect both who migrates and the premigration skill accumulation of those who might wish to migrate.

Research such as the IRPA evaluation (CIC 2010) demonstrates that immigrants who are sponsored by an employer and have a job waiting for them do better economically, at least in the short run — as one would expect. This relationship justifies the current use of adaptability points for arranged employment in the FSWP’s points system. Increasing the use of employer nominee programs, such as some streams of the PNP, can assist with short-run outcomes. Employers possess knowledge of the local and immediate labour requirements that is difficult to generate centrally. To ensure that such input is consistent with longer-run goals, however, the use of employer nominations should be embedded within a set of criteria that will regulate educational and skill levels as well as the number of applicants chosen and possibly other characteristics. Such an approach would ensure that the types of immigrants selected to achieve short-run goals (such as filling labour shortages within particular regions or occupations) are also consistent with the longer-run goals that have been in place in Canada for some time. Further, there should be a counterbalance to employer nomination, perhaps similar to the current system’s labour market opinions (LMOs), both to ensure that employers are not simply driving wages (and employment standards) toward the global minimum and to avoid fraud.

It is not yet possible to evaluate the effect of many of the recent changes on immigrants’ economic integration. An evaluation of the relatively short-run outcomes associated with the PNP has recently been completed, but the PNP is expanding and evolving at such a rapid rate that ongoing short-run evaluation is required. Evaluations of the success of ministerial instructions and the CEC in achieving their goals will also be important for policy development. Most importantly, an evaluation program should not stop with research on the short-run outcomes of the programs and their participants. While early evidence on program achievements is important, it is the longer-run outcomes that really matter. This suggests an ongoing program of monitoring and evaluation that would also provide feedback to improve the day-to-day management of the system, which is increasingly decentralized with the PNP. Implementing research on perhaps the most important economic goal, increasing GDP per capita, about which little is known in Canada, would also aid in policy development.

The question of meeting specific occupational shortages, either short-run or long-run, through immigration policy has been debated for decades. Policy practitioners in Canada have vacillated between enthusiasm for it and dismissal of it as an approach that does not work. Other countries have had similar experiences. Generally speaking, economists are sometimes enthusiastic about the theoretical prospect of finding complementarities, but less so regarding the possibility of success in practice. Green and Green (1999) conclude that there are better ways to respond to occupational shortages than through immigration. Freeman (2006) concludes that the necessary information on which to base program changes is not available. Occupational forecasting is simply not sufficiently reliable. The CIC evaluation (2012) of the PNPs also notes the difficulty that provinces have generating the information needed to adequately assess even short-run labour or skill shortages. Only one province had a systematic method of generating such information. Most relied on ad hoc discussions with employers, regulatory bodies, chambers of commerce and other groups. The evaluation concluded that labour shortages were not well documented in most provinces; it is a very difficult task.

Meeting specific occupational shortages may be difficult, but more general human capital considerations deserve a place in immigration selection policy, particularly when considering longer-run outcomes. During much of the decade prior to the most recent changes, Canada focused on longer-run nation-building goals exemplified by the “human capital” approach to immigration. Under the human capital model, the goal of meeting specific occupational shortages is replaced by the selection of more highly skilled and educated immigrants, including those in the trades and with post-secondary education, because their enhanced ability to adjust to changing labour market circumstances should result in better outcomes in the longer run. The more recent changes in the immigration system have moved us toward a shorter-run perspective. Many immigrants selected under the PNP and the TFWP are chosen to fill perceived short-run gaps in the labour market. Such shortages are often identified by employers, who, by the very nature of their needs, will tend to focus on the present and very near future.

While short-run needs obviously have a place in immigration policy, it is the long run that really matters. European guest-worker programs were set up to fill short-run requirements, but the long-run result has been less than favourable, with the children of lower-skilled immigrants having considerable difficulty successfully integrating into the labour market. In the United States, it seems likely that the educational and labour market outcomes of the children of immigrants as a group will not be strong over the coming decades. This likely result is largely related to American immigration policy and how it was implemented (Aydemir and Sweetman 2008; Picot and Hou 2010).

Of course, new immigrants get to the long run through the short run, and good labour market outcomes in the short term may be quite important for long-term success. But short-term decisions need to be made with a view to the full life cycle and even to intergenerational consequences. Looking to the very long run, Canada is among the world leaders in the successful educational and economic outcomes of the children of immigrants, with obvious economic and social benefits. Ensuring that this success is in no way placed in jeopardy by changes to the selection system should be a high priority. Hence, even short-run requirements should be evaluated with the longer term in mind. In this context, continuing to focus on high-skilled immigrants in the economic class — workers in skilled trades, medical technologists and those with similar occupation-specific skill sets, as well as immigrants with post-secondary and professional education — has numerous advantages.20 The evidence to support this view includes the following:

Tempering the evidence in favour of the highly skilled, one caveat to an overly strong focus on highly educated immigration should be borne in mind. A rapid increase in the supply of highly educated labour, through either the education system or immigration, could suppress wages and increase underemployment among highly educated workers. Aydemir and Borjas (2007) suggest that wage suppression occurred from 1980 to 2000 in Canada as a result of the increase in the supply of university-educated labour through immigration; wages among holders of bachelor’s degrees fell by 5.8 percent over the period. This result would have the effect of suppressing the rise in wage inequality as well. However, the methodological challenges in estimating this effect are significant, and further research is likely required to confirm such a finding. Keeping a close eye on the potential labour market effects of the composition of immigration is warranted.

Understanding the relationship between the short run and the longer run is important. However, because short-run outcomes are by definition more immediately evident, and because it is difficult to know precisely the determinants of longer-term outcomes, the latter are often given less consideration. As the pendulum swings, longer-term goals should not be overlooked since it is the full set of costs and benefits going forward that matters.

Abada, T., F. Hou, and B. Ram. 2008. Group Differences in Educational Attainment among the Children of Immigrants. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Abbott, M.G., and C.M. Beach. 2011. Do Admission Criteria and Economic Recessions Affect Immigrant Earnings? IRPP Study 22. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.