Immigration is increasingly preoccupying politicians, policy-makers and citizens around the world. For the most part, however, the focus has been on the eco- nomic impact and social integration of new migrants. The authors of this study, François Crépeau and Delphine Nakache, address an issue that is often overlooked: the legal framework through which we welcome newcomers, whether they are legal or illegal. More specifically, they examine the Canadian migration regime and the dispari- ties between state migration controls (the state sover- eignty paradigm) on the one hand, and international and national provisions to protect fundamental rights (the human rights paradigm) on the other. The authors sug- gest ways that these two apparently conflicting para- digms can be reconciled so as to ensure that migrants’ individual rights are duly protected.

Crépeau and Nakache look first at how migrants (including irregular migrants, defined, in this paper, as migrants who are in – or try to enter – a destination country without proper authorization) have benefited from increased protection of human rights since the Second World War. The right of asylum, the principle of nonrefoulement, procedural rights, the guarantee of an effective remedy, and equality and nondiscrimination provisions have all found new expression or renewed strength under modern constitutional and international human rights regimes. In Canada, the case law relating to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms has consid- erably expanded the Charter’s protection of individual rights and freedoms both for citizens and foreigners, especially with regard to section 7 (the right to security of the person) and section 15 (the right to equality).

But, paradoxically, say the authors, over the last two decades, migrants’ rights have in reality been eroded in the West, as their treatment has increasingly been considered an internal issue relating to border security. Visa regimes, carrier sanctions, and interdic- tion and interception mechanisms have been put in place to try to prevent undocumented migrants from arriving on our shores. Deterrent measures – for example, the elimination of refugee appeals, reduced legal aid, increased detention and penalties for migrant smuggling – have also been used to send a message abroad to discourage irregular migrants. Moreover, regional initiatives, such as the Canada-US Safe Third Country Agreement, have been established to serve as preventive and deterrent mechanisms.

Since 9/11, migrants’ rights have been further eroded. Irregular migration has become a focus of the new global security paradigm, which has been used to legitimize many measures that would have been considered inap- propriate before. For example, the Canada-US Immigration Cooperation and Smart Border Action Plan allows for communication of passenger information, the use of enhanced biometrics and increased bilateral secur- ity cooperation. Measures aimed specifically at migrants have also been developed, such as the use of security concerns as grounds for inadmissibility, increased deten- tion of suspects and security certificates.

Canadian courts will have to decide whether maintain- ing a distinction between the rights of foreigners and those of citizens is sustainable over the long term under our modern human rights regime, as foreign tribunals such as the British House of Lords have started to do. In other words, we must determine whether treating irregu- lar migrants as second-class legal subjects – sometimes even as legal nonentities – is compatible with our core values. Crépeau and Nakache conclude that to deal with this question, we must first recognize that the principle of territorial sovereignty cannot be used to justify unlimited violations of individual rights and freedoms. They recom- mend using the existing mechanisms and structures of the international and national human rights system as guidelines to review Canada’s existing measures and inform future policies. With regard to the new Canadian security and migration legislation, the authors argue that judges should continue to hold Parliament accountable for respecting the high standards embodied in the Charter such as the right to life, liberty and security of the per- son; the freedoms of religion, association and expression; and the equality provisions.

In a period when alarmist media and politicians call for stricter border controls, detention of asylum-seekers, deportation of illegal migrants and other heightened security measures, judges have a critical role to play in making citizens understand that meaningful equality means protecting foreigners from human rights abuses to the same extent that citizens are protected.

International human rights law, international humanitarian law, international refugee law and international criminal law: each chapter of this corpus stands as a fundamental defense against assaults on our common humanity… The very power of these rules lies in the fact that they protect even the most vulnerable, and bind even the most powerful. No one stands so high as to be above the reach of their authority. No one falls so low as to be below the guard of their protection. Sergio Vieira de Mello, United Nations General Assembly, November 2002

In the last few years, large numbers of people fleeing persecution, human rights violations and armed conflicts, or displaced by natural or human-made disasters, have sought asylum in developed countries around the globe. However, the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) reported in March 2005 that the number of asylum-seekers arriving in industrialized countries had dropped 40 percent since 2001, to reach in 2004 its lowest level for 16 years (396,400). Whereas Europe as a whole (44 countries, including countries of the former Soviet Union and former Yugoslavia) saw asylum applications decline by 21 percent between 2003 and 2004, the United States and Canada recorded a 26 percent decrease, and Australia and New Zealand a 28 percent drop, which is the largest fall in asylum requests. Canada was in 2004 the fifth-largest destina- tion country for asylum-seekers, preceded by France (the largest destination country), the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany (UNHCR 2005).

When requesting asylum, some migrants fall within the narrow class of “refugee,” as defined by the 1951 Refugee Convention and the Refugee Protocol.1 Some, though in need of protection and relief, do not. However, in the last few decades, the international community has developed a number of instruments that could potentially affect every person involved in migration. Constitutional, regional and universal standards dedicated to the protection and promotion of rights and freedoms of all in general, and of migrants in particular, are more sophisticated, and implementation mechanisms are more effective than before. These instruments have been developed to impose on states duties toward individuals based not on their nationality but on their humanity. In other words, the central notion of human rights is “the implicit assertion that certain principles are true and valid for all people, in all societies, under all condi- tions of economic, political, ethnic and cultural life… These principles are present in the very fact of our common humanity” (Stackhouse 1984, 1).

But recently, states whose sovereignty is affected by many aspects of globalization in the economic and social fields, have tried to regain political ground by emphasizing their traditional mission, that of national security. In the past two decades, the phe- nomenon of the “securitization” of the public sphere has emerged. This phenomenon is defined as the overall process of turning a policy issue (such as drug trafficking or international migration) into a security issue (Faist 2004). This resulted in the definition of new fields of government activity: food security, environmental security, biosecurity, transport secur- ity, industrial security, international security and migration security, to name only a few.2

In this new context, where migration has been gradually “located in a security logic” (Huysmans 1995, 230), migration controls have become an important part of the securitization agenda, which is a major step in the process of

the creation of a continuum of threats and general unease in which many different actors exchange their fears and beliefs in the making of a risky and dangerous society. The professionals in charge of the management of risk and fear especially transfer the legiti- macy they gain from struggles against ter- rorists, criminals, spies and counterfeiters towards other targets, most notably transna- tional political activists, people crossing bor- ders or people born in the country but with foreign parents. (Bigo 2002, 63)

The securitization agenda actually emerged years before the events of 9/11, although those attacks gave authorities more incentive to radically change migra- tion policies and make them harsher toward unwant- ed migrants. This shift has also been attributed to the altered roles of the military and other security forces in the post-Cold War period (Dunn and Palafox 2000). Securitization as a process means that the spheres of internal and external security are merging after a period of polarization in which those two areas of activity had hardly anything in common. We have witnessed a change in perspective: states — and specifically their external security agencies, which traditionally worked against a foreign enemy — have identified new threats, such as terrorism, inter- national criminality and unemployment, which coa- lesce in the image of the migrant. These threats affect the state from the inside but are very often publicly defined as having their origin “out there” (Bigo 1994; Bigo 1998; Kostakopoulou 2004, 45).

Securitization is also taken up by political leaders. Indeed, the promise of a threat-free society can be an inspired way to win votes, and states clearly see con- trolling the number of migrants as an electoral issue. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that non- citizens generally cannot participate in the democrat- ic decision-making process of the state where they reside. As such, their preferences are unlikely to count for much in politicians’ calculations. Public opinion usually views the state as an institution made to advance the interests of its citizens rather than those of foreigners, even resident ones. In this con- text, states feel perfectly justified in implementing migration policies that attach more weight to the potential costs of migrants to citizens than to the rights of migrants themselves, and especially refugees (Aradau 2001; Gibney 2003). The policies of the Howard government in Australia exemplify this phe- nomenon.

The stronger the state, the more draconian the measures it can take, especially given the new sur- veillance and military technologies available. Nations have developed an arsenal of measures designed to directly (physical barriers) or indirectly (deterrence) prevent migrants — especially irregular migrants — from setting foot on their territories. In the process, they have re-emphasized the role of the border as the traditional and tangible symbol of national sover- eignty and, with that, border control as a convenient tool for distinguishing between “us” and “them.”

This tightening of migration laws and policies in many of the destination countries has led to a decrease in the legal opportunities for international migration, creating an environment that is very con- ducive to migrant smuggling. If stricter border con- trols are imposed, more people will turn to irregular means of migrating, including resorting to smuggling organizations, because they will feel they have little choice. Although the information here is very patchy, some 800,000 people may be smuggled across bor- ders every year (Bhabha 2005). In brief, the stricter the controls, the more difficult the journey (price, route, means) and the more people risk their lives crossing the border. This has led observers to chal- lenge the wisdom of the enhanced barriers in the long run:

Much of existing policy-making is part of the problem (of increasing human trafficking and smuggling) and not the solution. Refugees are now forced to use illegal means if they want to access Europe at all. The direction of current policy risks not so much solving the problem of trafficking, but rather ending the right of asylum in Europe, one of the most fundamental of human rights. (Morrison and Crosland 2001, 1)

The situation is further complicated by the fact that there is, today, no clear definition of “irregular migration.” The concept covers a number of rather different issues that are implicitly but not explicitly defined in international law. For this paper, the term “irregular migrant” refers to any migrant who is in — or tries to enter — a destination country without proper authorization. This includes those who entered clandestinely, those who entered with forged docu- ments and those whose entry was legal but whose stay in the destination country is not. The term “irregular migrants” then means the same as “illegal migrant,” “undocumented migrant” and “clandestine migrant,” all of which describe migrants who do not clearly come within one of the national definitions of legal entry, residence and work, and who thus fall into a grey area of the law (Guild 2004, 4).

In brief, we are in a situation where although inter- national human rights law standards stress the funda- mental rights of all individuals in the face of state action, states often attempt to define the individual rights of migrants more narrowly by emphasizing the “noncitizen” legal status of such people. Thus, while the gap between “us” and “them” has been constantly reduced through the prism of the international human rights movement (implementing the human rights par- adigm, which is inclusive), this gap has been widened by states in their continuing search to exercise migra- tion controls through a variety of ever more sophisti- cated means (based on the territorial sovereignty paradigm, which is exclusive). How, then, is it possible to reconcile these two paradigms?

While answering this question, it should be made clear that there is no simple solution in such a com- plex field as migration. A good example of the inter-connectedness of the modern world is the scale of migration and the capacity of many individuals to move among states and regions. While in recent times this movement may have been a result of the increased availability of international travel, it must be remem- bered that human history has been marked indelibly by migration. “Exclusionary discourses” that assert the homogeneity of “nation states” might seek to deny it, but heterogeneity has always been the norm in human history. The resulting diversity has enriched numerous societies, and host countries have benefited immeasur- ably from the contributions made by immigrants and refugees. One facet of the response to the increased anxiety about the mobility of some groups (and the call for more stringent regulation) should therefore be to emphasize the benefits of migration and the pluralism it has fostered. It should not lead us to neglect the root causes of migration: people have always moved from unstable and poor environments to more prosperous and secure societies. Thus, as long as there are global inequities in wealth and prosperity on the planet, the migratory pressure on wealthier and more democratic zones will remain.

One key objective in the attempt to reconcile, in law, the sovereignty and human rights paradigms is to recognize that the principle of territorial sovereignty cannot justify unlimited human rights violations based on nationality. This principle will guide our develop- ment in this paper of a conception of territorial sover- eignty that is compatible with the mechanisms and structures of the international system.

Canada is facing this dilemma, as are all other Western countries. Both paradigms are simultaneously affecting all migrants. Canadian authorities feel the pres- sure of migration at the borders and have tried to pre- vent irregular migration with an array of deterrent and repressive measures. Indeed, in a context where migrant smuggling serves approximately half the irregular migrants worldwide (IOM 2003), Criminal Intelligence Service Canada (CISC) presents it as being “evident” in international airports (although it does not provide any figures on human smuggling and trafficking to support this argument). More precisely, according to CISC,

Organized crime groups are involved in transporting smuggled and trafficked indi- viduals to Canada with some individuals des- tined for the US. Persons trafficked into prostitution, and to a lesser extent into forced labor, in Canada come primarily from southeast Asia and eastern Europe. Asian- based organized crime groups in particular are involved in human smuggling/trafficking in Canada. (2004, 38)

Canada has also been at the forefront of the movement to increase the protection of human rights for all. Indeed, the case law created by Canadian courts based on the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (hereafter the Canadian Charter) is a model that is referred to all over the world. The reconciliation of these two approaches in Canada will be a task for the judiciary: finding clear ways to maintain the societal values that are reflect- ed in the Canadian Charter and that are necessary in a free and democratic society, including protecting rights and freedoms guaranteed to all while ensur- ing security for all. In fact, the role of the judiciary has not changed, but the international, political and social environment has.

The first part of this study will explain the increas- ing protection of the human rights of migrants, con- sonant with the growing human rights culture generally, worldwide and in Canada in particular. The second part will demonstrate how, paradoxically, the rights of noncitizens have been eroded in recent years through the enactment of a stricter migration regime. The third part will focus particularly on the changes that have occurred under various security agendas, especially since 9/11.

Human rights instruments have developed to impose on states duties toward individuals based not on their nationality but on their humanity or “personhood” (Harvey 2000). They en- title noncitizens to equality before the law, to a fair hearing before independent and impartial tribunals in proceedings that affect their rights and obligations, and to an effective remedy to enforce their substan- tive rights under international conventions. The record of UN treaty bodies and other human rights mechanisms in addressing violations of noncitizens’ human rights, though still incomplete, is developing in a positive manner on the international scene. What’s more, Canadian standards provide noncitizens with a high level of protection (except in state secur- ity cases), generally consistent with international human rights norms.

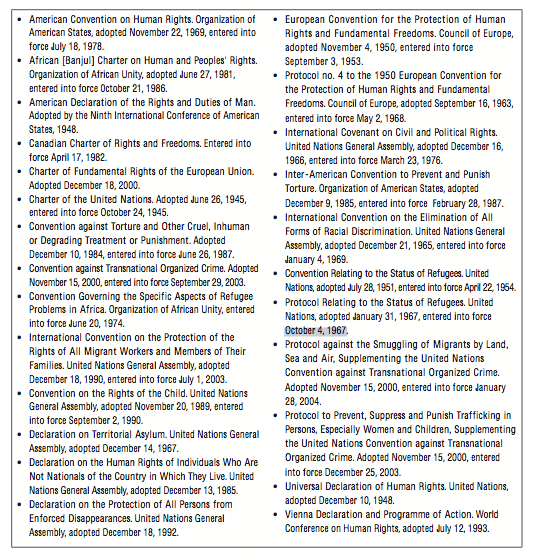

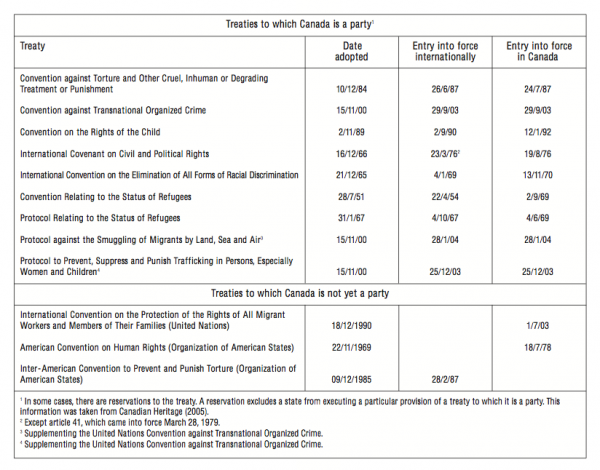

To carry out their pledge under the Charter of the United Nations to take action together and separately in cooperation with the UN, to promote “universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fun- damental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion” (arts. 55-6), states have engaged in an intense international effort, coor- dinated by the UN, to codify fundamental freedoms in numerous declarations and treaties. Human rights mechanisms have also been established on a regional basis in Europe, Africa and the Americas (Buergental 1995).3 No universally accepted codification of the human rights of migrants has yet been achieved. However, numerous international and regional human rights instruments and mechanisms can be employed to protect migrants, whether they be regu- lar or irregular. The limited scope of this study does not allow for a full review of these instruments. The following section briefly describes the potential of international human rights instruments as sources of substantive and procedural standards for enforcement of migrant rights.

The right to seek and enjoy asylum is guaranteed by a range of international and regional instruments.4 Although there is no universally accepted definition of asylum, it has been described as “the sum total of protection offered by a state on its territory in the exercise of sovereignty” (Harvey 2000, 47). The right to seek and enjoy asylum can be understood as the right of all individuals to escape from countries where they suffer profound violations of their basic human rights. Since those who exercise this right no longer benefit from the protection of their home countries, they are entitled to special protection by the international community. It should be noted, however, that the granting of asylum is exercised at the discretion of individual states: there is no right to asylum at the international level.

Nevertheless, international law recognizes an absolute prohibition against forcibly returning a person to a country where that person may be subjected to torture, and thus requires the implementation of effective remedies to guarantee the protection of this right (Lauterpacht and Bethlehem 2003). The principle of nonrefoulement has traditionally been defined in refugee law as the prohibition of the return of a refugee to “territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nation- ality, membership of a particular social group or politi- cal opinion” (1951 Refugee Convention, art. 33). However, the scope of the principle is now broader: it applies to torture and cruelty and to all persons, not only refugees. Nonrefoulement has found expression in various international and regional instruments.5

A categorical expression of the principle of non- refoulement is incorporated into article 3(1) of the Convention against Torture, which is an absolute and nonderogable provision.6 Of all treaty bodies, the UN Committee against Torture (UNCAT) has to date been the most active in developing case law on behalf of rejected asylum-seekers who, by bringing individual complaints, are looking to human rights treaties for alternative protection against deportation to their countries of origin: this puts political pressure on states not to send a person back to a place where s/he is likely to be tortured. The cases decided by UNCAT have moved the law on refugee protection in a posi- tive direction. Several countries, including Canada, have been involved in the jurisprudence of the Committee against Torture. In a 1994 case, UNCAT found that Canadian authorities had an obligation to refrain from forcibly returning Tahir Hussain Khan — a citizen of Pakistan of Kashmiri origin and a rejected asylum-seeker in Canada — to Pakistan.7 In December 2004, the committee, hearing a complaint from a Mexican claimant whose application for refugee sta- tus in Canada had been rejected, found that the Canadian refugee determination system had been unable to correct an erroneous decision.8 What is important here is that UNCAT puts the protection of the individual ahead of the sovereign powers of the state. Unless the state disproves the applicant’s evi- dence, the committee will favour protecting the human rights of the noncitizen. In its concluding observations of May 20, 2005, to Canada’s fourth and fifth periodic reports, UNCAT expressed concerns at several aspects of Canada’s immigration and antiter- rorist policies; for instance, the blanket exclusion of the status of refugee or person in need of protection for people falling within the security exceptions set out in the 1951 Refugee Convention; the explicit exception of certain categories of people posing se- curity or criminal risks from the protection against refoulement; Canada’s apparent willingness to resort to immigration processes to remove or expel individuals from its territory rather than prosecute them for ter- rorism and torture offences; and Canada’s reluctance to comply with all requests for interim measures of protec- tion, in the context of individual complaints. Among its recommendations, the committee urged that Canada unconditionally undertake to respect the absolute nature of article 3 in all circumstances and to fully incorporate the provisions of article 3 into the Canadian domestic law (UN Committee against Torture 2005).

Other instruments are lending support to the prin- ciple of nonrefoulement. As stated in its General Comment 20, the United Nations Human Rights Committee also considers that the prohibition of torture in article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights encompasses the prohibition of forcibly sending persons to countries where they may be sub- jected to torture or ill-treatment (UN Human Rights Committee 1992).

The principle of nonrefoulement is nowadays gener- ally considered, with respect to torture, as an impera- tive obligation under customary international law, indeed a part of jus cogens (Lauterpacht and Bethlehem 2003). The UN special rapporteur on torture routinely intervenes in cases where there is serious risk of extra- dition or deportation to a state or territory where the person in question would likely be in danger of being tortured (see UN Commission on Human Rights 2003; 2002, para. 8).

The case law that has developed within the European human rights system upholds protection from expulsion to a country when there are substantial grounds to believe that the person would be at risk of being tor- tured or subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treat- ment or punishment as defined under article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights.9

At the domestic level, some states have incorporated the terms of article 3 into their asylum procedures. In Canada, for example, an individual may apply as a “person in need of protection,” under section 97(1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (hereafter IRPA),10 if he or she is at risk of torture or cruel and unusual treatment or punishment. In effect, torture has been incorporated as another ground for refugee status (McAdam 2004, 628, 639).

The right to challenge an expulsion is vital to the right to seek asylum and to the principle of nonrefoulement, as well as to fundamental justice generally. Although it may be distinguished from extradition, the term “expulsion” covers all measures that result in the migrant being sent outside of the jurisdiction of the receiving state (Pacurar 2003, 17).

Human rights standards relating to expulsion of noncitizens lawfully in the territory of a state (that is, “persons who have entered a state territory in accordance with its legal system and/or are in pos- session of a valid residence permit and subject to state procedures aimed at their obligatory departure” (Novak 1993, 202) provide that expulsion must be decided by a competent authority in accordance with the law and must allow individuals to give rea- sons why they should not be expelled.11 Individuals are entitled both to have the decision reviewed and to be represented before the appeal or review authority (UN Human Rights Committee 1986). The procedural safeguards guaranteed by article 13 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights are considered minimal, and, indeed, states may provide for more, such as the right to appear in person at the review proceedings and the right to judicial assistance (Heckman 2003, 225).

Although irregular migrants benefit, to a lesser extent, from the procedural rights relating to expul- sion, they are equally protected against collective expulsions. Collective expulsions are indeed clearly prohibited by article 22 of the Convention on Migrant Workers, as well as by regional human rights laws, without distinguishing between lawfully and unlaw- fully resident foreigners (Council of Europe 2001).12

Most human rights treaties require states to provide an effective remedy to people whose treaty rights are found to have been violated.13 Therefore, state proce- dures affecting such treaty rights must contain a minimum of procedural safeguards and make avail- able certain preventive remedies, such as injunctive relief (Heckman 2003, 229).

In Chahal, a refugee and Sikh activist successfully argued before the European Court that judicial review of the minister’s decision to deport him as a risk to national security was not an effective remedy because the reviewing courts had been unable to independently assess the evidence for his claim that there was substantial risk of his being subjected to torture upon repatriation. This decision confirmed the absolute nature of the prohibition against torture by outlawing any balancing act between the interests of national security and the right of an individual to be free from torture and showed that effective remedy provisions in international human rights instruments can be used to challenge the sufficiency of domestic judicial and administrative decision-making and review mechanisms (Heckman 2003, 230).14

An appeal mechanism that can review the facts and law of the case is thus essential. The UN Committee against Torture, in its concluding observations of May 20, 2005, to Canada’s fourth and fifth periodic reports, recommended that Canada provide for judicial review of the merits, rather than simply of the reasonableness, of decisions to expel an individual where there were substantial grounds to believe the person faced a risk of torture (UN Committee against Torture 2005).

The nondiscrimination standard, notable for being included in the United Nations Charter15 and for being considered jus cogens,16 plays a central role in defin- ing the human rights of migrants. Most international and regional human rights treaties contain equality provisions requiring states to guarantee individuals equality before the law and equal protection of the law without discrimination (Fitzpatrick 2003, 172).

A differential treatment between nationals and non-nationals is permissible where the distinction is made pursuant to a legitimate aim, where it has an objective justification, and where reasonable propor- tionality exists between the means employed and the aims to be realized (UN Human Rights Committee 1986; 1989, 78).

A state party must ensure that the rights enumer- ated in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights are available to “all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction” (art. 2[1]), irrespective of reciprocity and nationality (art. 2[1], 26).17 The rights in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as they relate to distinctions against migrants can be divided into five categories (Fitzpatrick 2003, 174):

In summary, migrants are entitled to equal protec- tion with respect to many civil and political human rights, especially those relating to security of the per- son and due process. All nonderogable rights demand equality, but others (such as the right to fair trial) do as well. This will prove especially important when national security issues are at stake.

The Convention on Migrant Workers is the most recent and large-scale effort for a human rights response to migration in international law. Support among nations has been tentative. The convention came into force 13 years after it was opened for rati- fication and still, as of March 2005, major migration- receiving states (including Canada) were not among the 27 state parties.

The Convention on Migrant Workers addresses the situation of working migrants, entitling them to the same pay, hours, safety considerations and other workplace conditions that nationals enjoy. However, the convention goes beyond rights in the workplace by enumerating a comprehensive list of protections for migrants’ family members, with the goal of acknowledging migrant workers as more than simply economic factors of production.

The Convention on Migrant Workers also protects irregular migrants: “every migrant worker and every member of his or her family shall have the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law” (art. 24). As a consequence, irregular migrants are ensured some legal rights identical to those afforded to regular migrant workers and their families: fundamen- tal rights (arts. 8-24, 29); national treatment in matters such as equal conditions of work (art. 25), trade union rights (art. 26), social security (art. 27) and basic educa- tion (art. 30); preservation of cultural identity (art. 31); and repatriation of savings (art. 32).

In conclusion, the human rights of migrants have been low on the international human rights agenda, but this issue is now finally gaining more visibility. Substantive and procedural standards are being devel- oped or simply applied to them within international and regional human rights systems, thus reinforcing migrants’ status as holders of rights and not simply tar- gets of states’ sovereign power.

The concept of using international human rights law as guidance in the interpretation of Canadian law stan- dards has been accepted by the Supreme Court of Canada in its case law. Moreover, the enactment of the Charter has engaged the Canadian courts in an intense process of better defining and defending migrants’ human rights.

Given the prevailing dualist approach regarding the role of international law within Canada’s legal system, inter- nalizing unimplemented international standards within Canadian law can be problematic.18 Over the years, however, the Supreme Court of Canada recognized the important role of international law in interpreting the Constitution (Bastarache 2001, 9-10; La Forest 1996).19

The Supreme Court of Canada has articulated some important guiding principles, especially in migration mat- ters. In fact, in Canada, as in Australia and New Zealand, the majority of the case law concerning the use of inter- national human rights standards in domestic law seems to emerge from the administrative realm, and most of those administrative cases concern some aspect of immigration or refugee law (Macklin 2002). One of the reasons for this situation is that, traditionally, state authorities have dealt with foreigners with almost complete discretionary pow- ers. It was believed, in accordance with the principle that immigration is a privilege not a right, that foreigners had no right to oppose any decision affecting them made by competent authorities. With the advent of the constitutional protection of human rights and the recog- nition of international human rights law as a source of interpretation, however, this situation has changed con- siderably in Canada.

A good example of this trend can be seen in the way international law is used to interpret Canada’s IRPA, which itself contains the definition of “refugee” and the exclusion provisions found in the 1951 Refugee Convention. It is not infrequent to see Immigration and Refugee Board (hereafter IRB) decisions using human rights standards elaborated in international instruments in order to determine whether the claimant fears perse- cution (Macklin 2001, 326).

Decisions from the Supreme Court confirm this trend. In Pushpanathan, the majority held that, since the purpose of incorporating article 1F(c) of the 1951 Refugee Convention in the IRPA was to implement that convention, an interpretation consistent with Canada’s obligations under that convention had to be adopted.20 In Baker, the Supreme Court established that, although Canada had never incorporated the Convention on the Rights of the Child into domestic law, the immigration official exercising discretion in deportation cases was nevertheless bound to consider the “values” expressed in that convention, specifically the principle of “the best interests of the child.”21 Baker was of tremendous importance for administra- tive law, since it directed administrative decision- makers to look to those values in conventional international human rights law that resonate with the fundamental values of Canadian society in order to identify the relevant considerations delimiting their discretionary decision-making powers. In Suresh, a case decided after 9/11, the court, recognizing that Canada has a legitimate and compelling interest in combatting terrorism but is also committed to funda- mental justice, decided that expelling a suspected ter- rorist to a country where he faced the risk of torture violated the principle of fundamental justice pro- tected by section 7 of the Canadian Charter and con- firmed the absolute prohibition of torture and the principle of nonrefoulement “even where national security interests are at stake.”22

In conclusion, there are important judicial pro- nouncements on the domestic application of interna- tional human rights law standards. Although much depends on the particular circumstances of the case, we see from the Supreme Court’s decisions that the weight of international standards can be important. This is especially significant when trying to limit the discretionary nature of government’s decisions regard- ing foreigners who are suspected of terrorist activities.

Since 1982, fundamental rights and freedoms have been set forth in the Canadian Charter, providing an essential conceptual framework in asylum and migra- tion issues, as government legislation, programs and policies have been tested against its standards.

The Supreme Court, in Singh, held that refugee claimants — that is, claimants who are neither citi- zens nor permanent residents of Canada — are enti- tled to claim the protection of section 7 of the Charter, which provides that everyone should enjoy security of the person. This encompasses “freedom from the threat of physical punishment or suffering as well as freedom from such punishment itself.”23 Specifically, Singh established that the assessment of a risk to the security of the person means an assess- ment of the threat to any of the three rights guaran- teed to a refugee — that is, the right to status determination, the right to appeal a removal or deportation order and the right to protection against refoulement — and stressed that impairment of these rights would threaten security of the person, as they were “the avenues open to [the refugee claimant] under the Act to escape from…fear and persecution.”24 The court then determined that the procedure used in Canada to decide a refugee claim (that is, a written record of the examination before an immigration officer) did not comply with the principles of funda- mental justice because it did not provide an adequate opportunity for claimants to state their case and to respond to contrary evidence (the right to an oral hearing). The Singh decision had a significant impact on refugee law in Canada, pushing the federal gov- ernment to create the IRB in 1989 to provide an oral hearing to eligible refugee claimants.

Section 7 applies to “everyone,” and the court saw no reason to exclude refugee claimants from its scope. In essence, the Supreme Court of Canada embraced a theory of reciprocity of obligations and rights; that is, if asylum-seekers are to be subject to the full force of Canadian law, then they are logically entitled to benefit from Canadian standards of respect for human dignity (Galloway 1994; Eliadis 1995).

Since Singh, the Supreme Court has had occasion to examine the Charter rights of noncitizens in a variety of immigration and refugee protection con- cerns. A more restrictive outlook has characterized cases relating to national security or state sovereignty concerns. As regards the nonrefoulement standard, Charter protection or remedies have been denied, essentially on the basis that noncitizens possess vir- tually no recognizable life, liberty or security of the person that would be violated by their removal from Canada.25 To date, the courts have also upheld the process on the basis that detainees held under immi- gration laws are entitled to a diminished level of Charter protection. These decisions constitute a par- tial retreat from the breadth of Singh, and they have been described as “the low point in Canadian jurisprudence as it relates to the protection of non- citizens” (Waldman 1992, para. 2.72.48).

Section 15(1) of the Charter guarantees to an individ- ual equality before and under the law and the right to “equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimina- tion based on race, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

Canadian courts still struggle with section 15 and its interpretation. In Andrews, the Supreme Court ini- tially took a broad view of the guarantee of section 15 as it applies to foreigners. The court there held that section 15 prohibits discrimination on the basis of the analogous ground of citizenship. The inference from Andrews, then, is that the institutional and pro- cedural safeguards afforded to Canadian citizens should be made available to similarly situated non- citizens. In fact, this has not really happened.26

In Chiarelli, the Supreme Court rejected the claim that the Immigration Act violated section 15 by authorizing the deportation of only noncitizens. This does not mean, however, that the manner in which the decision to deport is taken can be arbitrary in any way. In Baker and Suresh, the Supreme Court outlined the principles governing the content of the duty of fairness that applies in cases of a deportation order, including participatory rights, but the analysis never developed around the concept of equality before the law.27

The Andrews test was revisited in the Law case and made more stringent, adding in particular a requirement that the discrimination must constitute a violation of human dignity.28 In the very few cases where the rights of noncitizens have been at stake since Law, and even more since 9/11, the courts have taken a very positivist attitude and upheld quite sys- tematically the distinctions made by the government or the legislature among citizens, permanent residents and foreign nationals. The courts found no violation of human dignity in the differentiated treatment of for- eigners as foreigners.29 Although the section 15 argu- ment has often not been well substantiated by lawyers, leaving room for further developments, for the present it seems clear that “section 15…with its promise of equality before the law, has no traction when it comes to the exclusionary dimension of immigration law” (Macklin 2004).

In conclusion, Canadian law contains valuable stan- dards for noncitizens in general and asylum-seekers in particular. However, each has limitations, and these limitations are exacerbated by the present immigration context, which is characterized by an emphasis on security and a narrower reading of the rights and inter- ests of noncitizens.

Despite the incidence of abuse, migrants’ rights have long been on the margins of the international human rights agenda, essentially because of a lack of data, the gaps between different institutional mandates, the exis- tence of parallel systems for protecting employment rights and human rights, the dearth of reporting by human rights NGOs, the dominance of refugee protec- tion in the migration field, and the fact that, until the Convention on Migrant Workers was drafted, human rights law only made implicit reference to migrants (as non-nationals) in the context of the free movement of labour. In the last two decades, however, there has been greater recognition of the issue of the rights of migrants, with new international standards, new inter- pretations of existing norms, new data-collecting and new reporting mechanisms strengthening awareness and creating new protection tools (Grant 2005).

The relationship between migration and human rights is extremely complex, however. First, it is multi- faceted. Human rights issues arise at all stages of the migration cycle: in the country of origin, during transit and in the country of destination. Second, while inter- national human rights law recognizes the right to leave one’s own country, there is no corresponding right to enter another country without that state’s permission. There is a genuine tension between international law and the exercise of state sovereignty, particularly in the present era of globalization, when control over the movement of people across national borders has become a last bastion of national sovereignty (Dauvergne 2004). In other words, states adopt migration policies that best suit the interests of the state and its society. Nevertheless, if a state decides that a migrant has entered the country illegally, this decision needs not, in itself, if properly taken, conflict with human rights principles. Third, although the link between migration and security is not new, growing security concerns in the last few years have fundamentally changed the playing field of immigration regulation. And the ten- dency to view migrants as a threat to national secur- ity has coincided with the re-emergence of anti-immigrant politics on the extreme right. It should be remembered, however, that treaty law is an explicit acceptance by nation states of some limitation to their sovereignty as well as an agreement to abide by the standard set out in international law. A migrant who has entered or remained in a country illegally is not per se a criminal, and a migrant’s being merely in breach of immigration regulations does not nullify the state’s duty under international law to protect his or her basic rights without discrimination.

In brief, Western democracies are increasingly caught between accepted rights-based standard on the one hand, and political and security pressures to effec- tively and securely control their borders on the other.

In dealing with security and immigration issues, host countries have taken a number of steps to reduce the rights and freedoms of noncitizens. They have strengthened their control over noncitizens through harsher immigration measures to police their external borders (Gibney and Hansen 2003). This is true for most Western countries, although in varied ways, since each country has a different legal, consti- tutional and international setting.

There is a long list of measures from which coun- tries can find inspiration in designing their own strategies. Preventive measures are used to prevent irregular migrants from setting foot on the territory, while deterrent measures allow for such rash treat- ment of undesirable foreigners that other foreigners in a similar situation will think twice before trying to reach the territory.

Beginning in the early 1980s, a number of immigra- tion policy measures, notably visa regimes and carrier sanctions, were either initiated or retooled in order to prevent the arrival of irregular migrants or asylum-seekers.

Many countries now use visa regimes explicitly to pre- vent the movement of people from source countries to their territory. Australia requires visas for all foreign nationals wishing to enter its territory, whereas Canada, the US and EU member states require visas only for the nationals of countries deemed to produce large num- bers of asylum-seekers (such as Iraq and Afghanistan) or overstayers (such as Morocco or Nigeria). Canada and the US have, under the Smart Border Agreement,30 harmonized visa requirements, resulting in a situation where the citizens of some 175 countries now require visas to enter the two states (DFAIT 2004). A similar harmonization now prevails for all countries in the EU’s Schengen area, where undesirable migrants are not only prevented from entering one country, but they are prevented from entering a whole region.31

While visa regimes have purposes other than stop- ping asylum flows, the linkage with asylum has become clear with, for example, the imposition of a visa requirement for Tamils by the British government in 1986, for Algerians by France in the same year and, most recently, for Hungarians by Canada in 2002. In almost all cases, asylum-seekers wishing to travel to the West have to apply for visas, and Western states can simply deny visas to those believed to be seeking asylum (Gibney and Hansen 2003).

Visa requirements are the most frequent migration control device and are most effective when they are used in conjunction with carrier sanctions.

Carrier sanctions are fines or other penalties imposed by states on airlines, railways and shipping compa- nies for bringing foreign nationals to their territory without the required documentation (for example, valid passports and visas). These sanctions transfer migration management to private carriers, who, if they wish to avoid substantial fines, must make deci- sions on the possession and authenticity of the docu- ments presented by travellers. Canada’s IRPA has several provisions that make carriers responsible for the removal costs of passengers arriving at Canadian airports without proper documents (ss. 148[1][a], 279[1]). Under the IRPA, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) charges a carrier an administration fee for each traveller arriving with improper documents. The CBSA has signed agreements with most airlines flying regular routes to Canada. Carriers with good performance records pay reduced adminis- tration fees. Carriers without signed agreements pay C$3,200 for each traveller with improper documents. For carriers with signed agreements, the fee drops to between zero and C$2,400, depending on the carrier’s history of transporting undocumented travellers. Airlines, in turn, agree that immigration control offi- cers will train their staff and assist them at foreign airports in identifying passengers with improper travel documents (CreÌpeau and Jimenez 2004). Preinspection agreements also enable countries to post immigration officers at airports, train stations or ports of foreign countries to screen out improperly documented migrants.

Like most Western countries, Canada has increasingly resorted to interception and interdiction abroad (in countries of origin or of transit) to prevent irregular migrants from entering its territory. Interdiction poli- cies, which convey a strong sense of the “not in my backyard” phenomenon (Morris 2003), place obstacles in the path of the right to seek and obtain asylum, as outlined by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in the Haitian Interdiction case in 1996.32

Canada maintains that it respects its international obli- gations toward the protection of refugees, but nothing in the Canadian government’s interception and inter- diction policies provides for an effective means of allowing migrants in real need of protection to come to Canada. Thirty-two percent of Canada’s interceptions in 2000 were made in the migrant’s country of origin or in countries that lack a refugee protection system com- parable to Canada’s (CreÌpeau and Jimenez 2004).

Canada currently has 45 migration integrity offi- cers (MIOs) in 39 key locations overseas (DFAIT 2004). Australia, the Netherlands and Norway, how- ever, send immigration officials abroad to train local airline staff at foreign airports to recognize fraudu- lent or incomplete documentation. The work of Canada’s MIOs resulted in an interdiction rate of 72 percent in 2003. Although verification is next to impossible, this figure means that, according to DFAIT, of all attempted irregular entries by air, 72 percent (over 6,000 individuals) were stopped before they reached Canada. Since 1999, more than 40,000 people have been intercepted by the MIO network before they boarded planes for North America (DFAIT 2004; see also Canadian Embassy 2005).33

While preinspection regimes extend migration boundaries, some states have tried to declare parts of their airports “international zones” in order to deter asylum-seekers. This practice is based on the fiction that the foreigner has not yet been admitted into the country and is still in some kind of international no- man’s-land. Established in areas accessible only to air- port personnel, these zones are set up to “allow” officials to refuse asylum-seekers the protection avail- able to those officially on state territory (for example, the right to legal representation or access to a review process), and to expedite their speedy removal from the country. Although such zones have been rejected in principle by domestic and international courts, the absence of external oversight makes what happens in these areas difficult to control (CreÌpeau 1995).34

The most radical development along these lines was the redefinition by the Australian government of the status of its island territories for immigration purposes. A 2001 act “excised” Christmas Island, Ashmore Reef, Cocos Island and other territories from Australia’s “migration zone,” so that, according to Australian law, the landing of asylum-seekers on these territories did not trigger the country’s protection obligations. While Australia’s obligations under international law, includ- ing the 1951 Refugee Convention, could not be changed by such a unilateral act, the protections asso- ciated with the country’s domestic asylum laws (for example, the right to appeal a negative decision) were no longer available to individuals on these territories (Gibney and Colson 2005).

Going further, the US has used its military base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to process Haitian and Cuban asylum-seekers in order to obviate the need to grant them the constitutional protections held by foreigners on US territory (Gibney and Colson 2005). In a similar vein, as one element of the “Pacific solution,” Australia took “interdictees” to processing camps on islands in the Pacific (Nauru, Fiji, Papua New Guinea), which those countries accepted in exchange for millions of dollars in aid from the Australian government (Morris 2003).

These preventive measures are very convenient for states. First, the extension of state enforcement mecha- nisms beyond state territory does not carry with it a clear obligation to ensure international protection for those who need it. Second, it is extremely difficult to control the actions of states overseas. By using extra- territorial mechanisms, states can pretend that they are free of the international and national legal constraints and scrutiny they face when migrants arrive on their territory — migrants are “outside” rather than “inside,” and thus they do not constitute a domestic political or legal problem anymore. And it is true that media, politicians, public opinion and even NGOs generally are not as attentive to what happens out- side their nation’s territory.

States are not, however, beyond the bounds of responsibility. The International Law Commission’s Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (2001), which were developed over the course of 30 years by international jurists, provide that responsibility ultimately hinges on whether the relevant conduct can be attributed to that state and not whether it occurs within the territory of the state or outside it. The place where such an act occurs is thus simply not a relevant consideration, and there is today ample authority at the global and regional lev- els to support this argument (Lauterpacht and Bethlehem 2003, 110; Brouwer and Kumin 2003; Crawford 2002).

The UN Human Rights Committee, which authorita- tively interprets the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, was extremely clear when it explained in its most recent general comment on article 2:

[A] State Party must respect and ensure the rights laid down in the Covenant to anyone within the power or effective control of that State Party, even if not situated within the territory of the State Party…this principle also applies to those within the power or effective control of the forces of a State Party acting outside its territory, regardless of the circumstances in which such power or effective control was obtained, such as forces constituting a national contingent of a State Party assigned to an international peace- keeping or peace-enforcement operation. (UN Human Rights Committee 2004, para. 10)

This unambiguous view by the committee is reflected in its consistent position on Israel. Indeed, both the UN Human Rights Committee and the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights35 hold Israel responsible under the covenants in the occupied territories, since Israel exercises “effective control” there.36

The extraterritorial applicability of human rights law is further underlined by the jurisprudence of regional human rights systems. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has considered that the American Declaration on Human Rights is appli- cable to acts of foreign forces — for example, during the occupation of Grenada, or, more recently, in the context of the detentions in Guantanamo Bay.37 The European Court of Human Rights has also repeatedly determined that the protections afforded by the European Convention on Human Rights apply to all territories and people over which member states have effective control. Thus, in Loizidou, the court deter- mined that Turkey was liable for breaching the European Convention on Human Rights for actions of the authorities in northern Cyprus, over which Turkey exercised “effective overall control.”38

In domestic courts, decisions challenge the manner rather than the principle. For example, the US Supreme Court in Rasul held, in June 2004, that for- eign nationals imprisoned without charge at Guantanamo were entitled to bring legal action chal- lenging their captivity in US federal courts.39 In December 2004, the UK House of Lords also held that a preclearance immigration control scheme at Prague airport, conducted pursuant to an agreement with the Czech Republic, constituted direct racial discrimina- tion against Czech citizens of Romani origin in pre- venting them from travelling to the UK.40

Despite a growing recognition of state responsibi- lity under international, regional and domestic law, one must note the paradox between the advent of pre- ventive measures on the one hand, and the advance of a human rights culture on the other. In a context where politics push policies toward closure and restriction, but where the law inches unevenly toward greater respect for the human rights of foreigners, it is no wonder that Western states increasingly resort to nonarrival measures to insulate themselves from claims by migrants, especially asylum-seekers.

While preventive mechanisms directly impede the entry of migrants, deterrent measures operate more indirectly. These attempt to discourage asylum-seekers or irregular migrants from entering the country by making the cost of entry so high, or the benefits so low, that they do not attempt the journey. There is an obvious overlap in practice between preventive and deterrent measures, because many policies that suc- cessfully prevent entry also act to deter subsequent migrants from attempting to enter (Gibney and Hansen 2003). In brief, the deterrent policies focus on reducing the privileges and entitlements available to migrants in general and asylum-seekers in particular.

Since the early 1990s, Canadian immigration law has undergone distinct changes, eliminating most forms of appeal previously available to foreigners. These changes do not seem to have occurred to the same extent in other countries. Judicial review remains available in Canada, however. A rejected refugee claimant can apply to the federal courts, but only with leave from the court and essentially only on purely legal issues. Leave is rarely given, and the courts are not required to provide a reason when they deny leave. From 1998 to 2004, 89 percent of the applica- tions to the federal courts for judicial review of refugee claim determinations were denied leave. If we compare the number of applications granted leave during this period (under 4,000), with the number of claims refused by the Immigration and Refugee Board during this period (just under 87,800), we find that only 4 percent of claimants have had the opportunity to have the decision against them reviewed by a fed- eral court (CCR 2005b). Furthermore, when a claimant is granted leave by the court, factual mistakes will generally not be corrected since the court is not required to review the factual analysis unless that analysis is found to have been wholly unreasonable.41 If the original decision-maker considered all the evi- dence in a reasonable way but reached the wrong conclusion, the court will not intervene. In this way, the management of immigration files is certainly made more efficient, but human rights protection has been radically diminished, as unanimously observed by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, UN Human Rights Committee and UN Committee Against Torture, respectively, in 2000, 2002 and 2004 (CCR 2005b). In 2001, the IRPA created the Refugee Appeal Division (RAD), where refugee determinations could be reviewed. This right to an appeal on the mer- its for refugee claimants was balanced by a reduction from two to one in the number of IRB members hear- ing a case. In 2002, the government implemented the new law without implementing the RAD, thus delay- ing indefinitely a migrant’s right to appeal.

The Canadian government is joining the ranks of Western governments which are using the political context created by 9/11 to renege on a general commitment to the rule of law. This fact is most marked in the area of immigration and refugee law. Canada is now in flagrant violation of one of the cen- tral pillars of the rule of law, the right of access to an independent court to test the legality of decisions affecting basic rights. Judicial review of such decisions is available, but only on leave, which is infrequently granted. That this is an inadequate safeguard has been recognised through a legislative promise to establish a Refugee Appeal Division, a promise which the government refuses to implement. In persisting with this refusal, the government exhibits the two-faced stance which is so depressingly common these days whereby governments maintain the facade of the rule of law without delivering its substance. (David Dyzenhaus, quoted in CCR 2005b, 3)

Recently there have been cuts in legal aid for migrants in most host countries. In Australia, for example, legal aid in immigration matters has been substantially reduced over the last six years. In addition to the appli- cant being subjected to the means and merits test, legal aid assistance can only be granted in migration matters where (1) there are differences of judicial opinion that have not been settled by the full court of the Australian Federal Court or the Australian High Court, or (2) the proceedings seek to challenge the lawfulness of deten- tion (Parliament of Australia 2004). In April 2004 in the UK, the Legal Services Commission introduced new funding arrangements for legal work on asylum and immigration issues, with the overall aim of reducing spending. The Department for Constitutional Affairs set out the rationale for the cuts, arguing that the system was an increasingly expensive “gravy train” for legal aid lawyers to carry out low-quality and unnecessary work on the cases of people who were not going to win the right to remain in the UK (Asylum Aid 2005).

In Canada, the refugee determination process, based on the Canadian Charter, is quasijudicial and each refugee claimant has the right to a hearing with full interpretation and the right to counsel (see discussion of Singh, above). However, it has never been deemed important in Canadian law and policy to provide sufficient legal aid to help migrants prepare their cases. Although the refugee determination system is under federal jurisdiction, legal aid in such matters has been left to the provincial legal aid regimes without ensuring adequate funding. In Ontario, the average legal aid fee for a refugee determina- tion case is still over C$1,500. In Quebec, it is C$455, which represents three hours of work if an interpreter is not required. In Manitoba, there is no legal aid for migrant cases. If the mafia boss has a right to legal aid, shouldn’t the provision of legal aid in refugee cases, where the consequences of an erroneous decision can be death, torture or prison, be treated as at least as impor- tant? (CreÌpeau and Jimenez 2004; Frecker et al. 2002).

Although Canada’s detention practice is not as harsh as what can be seen in other countries, such as the United States or Australia (the two countries automatically detain most illegal migrants),42 immigration detention has increased considerably in the past years, essentially because the IRPA and its regulations provide the citi- zenship and immigration minister with stronger author- ity to arrest and detain people who pose a security risk and those whose identity is in doubt.

As stated in section 55(2) of the IRPA, a person may be detained if that person is (1) not likely to appear for an examination, an inquiry or removal, (2) likely to pose a danger to the public or (3) undocu- mented or improperly documented. While these grounds are the same as in the former legislative regime, the provisions that allow detention are broad- ened. First, foreign nationals (people other than Canadian citizens or permanent residents) can be detained at any point in the claim process for identity reasons, whereas in the past they could only be detained on the basis of identity at the port of entry. Second, under section 55(3) of the IRPA, immigration officers have wider powers to detain all foreign nationals and permanent residents at a port of entry (1) on the basis of administrative convenience (for example, to continue the interview) or (2) when they have “reasonable grounds to suspect” inadmissibility on the basis of security or human rights violations. Third, section 55(2) of the IRPA expands the provi- sions for detention of a foreign national without a warrant at any stage of the determination process and for any ground for detention. Whereas there were pre- viously some limited circumstances in which foreign nationals within Canada could be arrested without a warrant, immigration officers are now authorized to arrest all people who are inadmissible, even if they are not about to be removed. The expansion of detention for lack of proper identity documentation is of partic- ular concern. Those seeking asylum are often forced to leave their countries without proper identity docu- mentation because it is precisely their identity that puts them at risk (Gauvreau and Williams 2002, 68). Moreover, one major criterion of detention in this context is the officer’s “satisfaction” with the level of the migrant’s “cooperation” in establishing his or her identity.43 The utility of requesting that the asylum- seeker take all measures to establish his or her identity is, however, questionable because such cooperation is required as soon as people enter the country, when they are under a great deal of stress and, given their experience in their home country, may still have a high degree of distrust of public authorities. Moreover, asylum-seekers may not want to cooperate in establishing their identities because applying to the author- ities of the home country for documentation may put family or colleagues still there at risk of persecution. Asylum-seekers are not compelled by the Canadian authorities to ask their embassies to provide them with identity documents, but they are strongly urged to do so, and the willingness to do so is viewed as clear evidence of cooperation. In such a context, how can one evaluate the noncollaboration of someone who is scared? How can one evaluate the lack of cooperation of someone who remains silent out of fear that his or her family still in the country of origin may be adversely affected if he or she does cooperate (Nakache 2002)?44

In addition to broader legal power to detain non- citizens, the government is making more use of the detention power. In the new budget allocations made by the federal government in December 2001, part of the funding for security included more money for immigration detention, the objective being to increase the number of people detained as well as the length of detention (DFAIT 2003). In 2003-04, 13,413 people were detained. This is an increase of 16 percent over the numbers for 2002-03 (11,503), of 40 percent over the numbers for 2001-02 (9,542), of 52 percent over the numbers for 2000-01 (8,786) and of 68 percent over the numbers for 1999-2000 (7,968) (CBSA 2004; CIC 2003). The number of detention days is not given by the newly established Canada Border Services Agency in its performance report, but we know from Citizenship and Immigraton Canada’s 2003 performance report that, in 2002-03, noncitizens were in detention for a total of 165,070 days, which is a 17 percent increase in the number of detention days over the previous fis- cal year (141,202) (CIC 2003). Despite security con- cerns, most of the money allocated to increased detention capacity is not being used to detain peo- ple considered threats to security; it is being used to respond to the increase in the detention of migrants with no adequate identification. From June to December 2003, for example, 56 percent of deten- tions were on grounds of flight risk, 10 percent because of a lack of satisfactory identity documents and only 1 percent on security grounds (Dench 2004). CIC has also tried other detention practices. For example, it has employed private security com- panies to implement deportation orders. In one such case, a security company kept one person in deten- tion in several successive countries for several weeks, without any authority to do so, before using forged documents to return the person to a country that may not even have been the person’s country of origin (CreÌpeau and Jimenez 2004).

Trafficking in people and migrant smuggling must be distinguished from one another. Despite the human rights concerns associated with smuggling and traf- ficking, it is actually law enforcement concerns (the war against terror, organized crime and irregular migration) that have moved this issue up on the international policy agenda. In 2000, two new proto- cols to the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime were drafted, dealing with traffick- ing and smuggling, respectively. The trafficking and the smuggling protocols are framed on a central dis- tinction between coerced and consensual irregular migrants. While people who are trafficked (and end up in forced labour or prostitution) are assumed not to have given their consent and are thus considered to be “victims,” migrants who are smuggled are con- sidered to have willingly engaged in the enterprise (Bhabha 2005). In other words, a person who is traf- ficked is kept under the control of the traffickers, whereas a migrant-smuggler simply facilitates the migrant’s clandestine entry into a country. It is easy to forget, however, that many irregular migrants, even those who are smuggled, need protection against human rights violations in their country and should not therefore be considered simply criminals, since they did only what many of us would do in similar circumstances: try to find the best way to pro- tect themselves and their families. And even if they might have technically broken the immigration laws of the host country, they retain certain rights and freedoms under the rule of law.

Although the two Palermo protocols stipulate that the migrants themselves should not be subject to criminal prosecution because of their illegal entry, the protocols require state parties to criminalize the con- duct of traffickers or smugglers and to cooperate with other states to strengthen international prevention and punishment of these activities (Bhabha 2005). These protocols were ratified by Canada in May 2002. The new IRPA consequently modified the penalty for migrant smuggling. The new Act imposes tougher maximum penalties for organizing irregular entry into Canada. For example, helping 10 individuals or more to cross the border irregularly, without any threat to persons or property (that is, not trafficking in people for slavery or prostitution purposes), is an offence punishable by life imprisonment. This is more than the punishment for rape at gunpoint, which carries a maxi- mum sentence of 14 years, and it is the same as that imposed for acts of genocide or crimes against human- ity. This is also much more than the legislation of other host countries, where the criminal penalties are a maxi- mum of 5 to 10 years of imprisonment (US State Department 2004, 115; see also European Union 2002). Last, but not least, the Canadian legislation does not distinguish between people who are motivated by humanitarian concerns and others. Contrary to the Smuggling Protocol, the IRPA does require remunera- tion or a benefit. Thus, someone who helps a family member flee persecution can be refused an asylum hear- ing or lose permanent residence without the possibility of appeal (CreÌpeau and Jimenez 2004). The deterrent effect of such grossly exaggerated penalties is doubtful, especially when, because of the “Western fortress,” most irregular migrants and most asylum-seekers must use help of some kind to enter Western countries for any reason (Morrison and Crosland 2001).

In December 2002, Canada and the US signed a safe third country agreement, which came into force in December 2004. This agreement allows each country to send back all the asylum-seekers who have reached its territory by way of the other. The rule applies only at a land port of entry; it does not apply to claims made at an airport, port or ferry landing (even by those coming from the US) or to claims made inside Canada. Figures provided by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) indicate that from 1995 to 2001, approximately one- third of all refugee claims in Canada (31 percent to 37 percent annually) were made by claimants known to have arrived from or through the US. Concretely, the agreement is expected to severely reduce the numbers of the now approximately 15,000 refugee claimants who arrive yearly in Canada from the United States (see Canada 2002; Manley 2001; US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants 2003).

Many nongovernmental organizations in Canada as well as the United Nations High Commission for Refugees have questioned the basic premise that the US is a safe country for all asylum-seekers. Although both the US and Canada are signatories to the 1951 Refugee Convention and the Refugee Protocol, certain US practices are of great concern: detention proce- dures, the expedited removal process (which excludes a full hearing of the claim and does not provide ade- quate procedural guarantees against refoulement or return to the country where there is a risk of perse- cution or torture), the one-year time limit to file a claim in the US, the more restrictive definition of refugee than that used in Canadian case law (espe- cially regarding gender-based persecution), and so on. The difference between the practices of the two states is most striking on the issue of the detention of children for immigration-related reasons. The United States routinely detains unaccompanied minors who lack legal status in the US and may be asylum-seekers, whereas in Canada they are pro- tected according to their “best interest,” as stated in Baker. This practice has been widely criticized by US and international human rights organizations (Macklin 2003). It is also very difficult for asylum- seekers to prove that they meet the exceptions to the safe third country rule (family reunification, unac- companied minors, nationals of a country to which Canada has temporarily suspended removals, and so on), in circumstances where documentation is scarce (Macklin 2003).

Last, but not least, the safe third country agree- ment will probably create a lucrative market for smugglers, who transport asylum-seekers across the border illegally. This is exactly what happened in Europe with the implementation of the safe third country provisions in the 1990 Dublin Convention. A study of the implementation of that convention, funded by the European Commission and carried out by the Danish Refugee Council, revealed, inter alia, that the “Dublin system” gave refugee claimants incentive to destroy identity and travel documents and to choose illegality and go under- ground in order to avoid transfer to a country where their claims might be dealt with less favourably. The EU ultimately recognized in that study that the “Dublin system” did not function as expected (Danish Refugee Council 2001). The fact that the safe third country agreement may create a huge market for migrant smugglers will further degrade the image of asylum-seekers, in effect turning them in the court of public opinion into menacing international criminals. Harsher repres- sive or deterrent measures against migrants will then be easier for governments to justify.

In conclusion, as a result of the recent multiplica- tion of restrictive migration policies, the vulnerability of migrants has increased and their rights have unquestionably been reduced at all stages of the migration process. This erosion of the rights of for- eigners is common to all receiving countries. Canada is probably better protected from from irregular flows of migrants than most comparable countries, consid- ering its relative geographical isolation and the fact that it is also somewhat less likely to enact the harsh- est measures because of the role played by the Canadian Charter. However, the more recent interna- tional security agenda has only reinforced pre- existing restrictive tendencies.