Dutch disease – along with its more virulent offspring, the resource curse – refers to the idea that a nation endowed with a bounty of natural resources can suffer adverse economic consequences as a result. This seems counter-intuitive. In principle, a country’s natural-resource windfall ought to enable it to improve economic welfare for all segments of its society, including future generations.

Whether Canada suffers from Dutch disease has been the subject of acrimonious political debate over the past few years. Indeed, the adverse indirect effects of growth in the resource sector on other sectors of the economy, such as manufacturing, have sparked much controversy, often ending up pitting Alberta’s economy against that of Ontario. While the jury is still out on how strongly segments of the Canadian economy are exhibiting the symptoms of Dutch disease, the fact remains that the country has for the most part benefited from a prolonged resource boom due to its abundant nonrenewable natural resources. However, when gauged in terms of providing economic benefits to all Canadians and the ability of governments to partially collect and spread the wealth, our resource riches have proven more of a mixed blessing.

Of course, most analysts would agree that higher export prices are good for Canada. This terms-of-trade gain improves our international purchasing power, as Canadians can buy more imports for a given amount of our exports. There are, however, important differences between natural-resource windfalls and those arising from terms-of-trade improvements in other sectors. Natural-resource wealth not only entails economic activity that draws factors of production from other sectors of the economy; it also generates rents, a significant portion of which flow to governments. This combination of diverted productive capacity and rent generation makes the management of natural resources challenging for governments.

Since natural resources in Canada are typically owned by the public sector, governments greatly influence the pace of development and extraction. This includes the provision of infrastructure to access the resources and transport them to markets. As a result, there is much potential for policy shortcomings in managing resources and collecting their associated rents. The most pressing concerns are inefficient taxation and regulation, inadequate infrastructure, externalities arising from resource production, and uncertainty about future policies. Another important consideration is that exploiting nonrenewables can have adverse environmental consequences, such as carbon emissions that contribute to climate change.

In Canada’s case, several factors further contribute to these potential policy shortcomings:

Active exchange rate channel: Resource prices are volatile, and there is a well-documented positive relationship between global commodity prices and Canada’s exchange rate. This can lead to an appreciation of the exchange rate during resource booms, hurting other tradable sectors of the economy.

Geography and minority ownership:Resource endowments like oil and natural gas are immobile, and distributed very unevenly. They are geographically concentrated in the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador, which account for a minority (only about 15 percent) of the Canadian population.

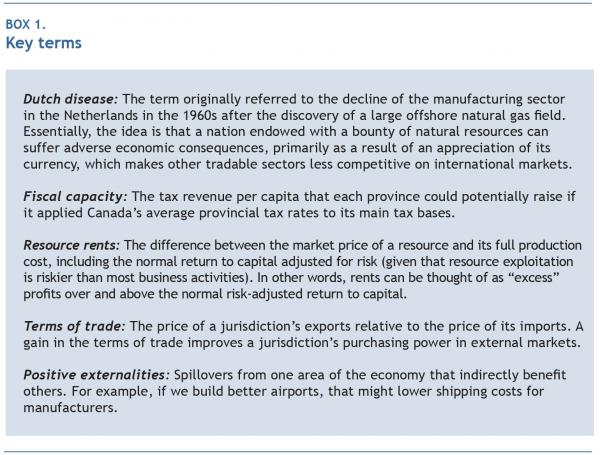

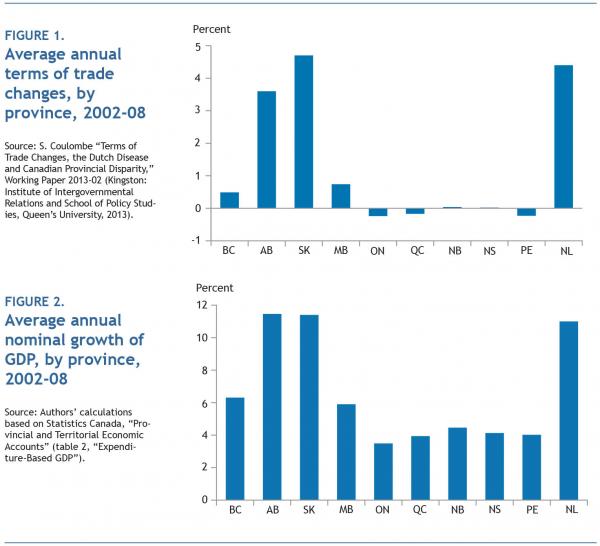

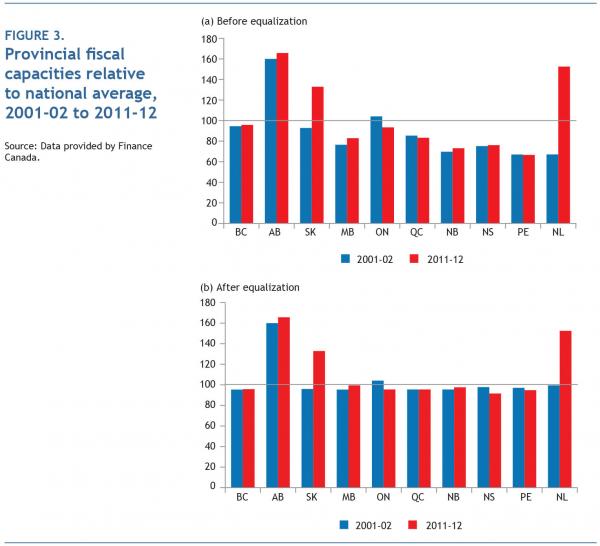

Decentralized federation: The resource boom, combined with the provinces’ constitutional power to directly tax resources, creates large interprovincial fiscal disparities that make the federal government’s equalization role much more difficult. Canada is one of the world’s most decentralized federations – provinces raise the majority (on average 80 percent) of their revenues, and they manage and tax their own natural resources. Therefore, when global resource prices are particularly strong – as they were in the boom period of 2002 to 2008 – this drives large differences in the terms of trade between provinces (figure 1). These translate into substantial variations in economic growth (figure 2), which are reflected in provincial government revenues and fiscal capacities. Based on data presented in figures 3a and 3b, we find that fiscal disparities before equalization have increased by approximately 20 percent over this period, while disparities after equalization have increased by 40 percent. Of course, federal equalization payments are still shrinking provincial fiscal disparities, but the equalization program’s overall effectiveness has diminished over time (from a 40 percent reduction in disparities in 2001 to only a 30percent reduction in 2011).

Tax competition and province building: Provinces face greater tax competition than does the federal government, so they might not collect an adequate share of rents (e.g., royalties), and they might not sufficiently save or invest those they do collect for future generations. Instead, they might use them to reduce other provincial taxes or increase spending in province-building activities that could put other provinces at a disadvantage.

This messy confluence of factors suggests that after a decade of strong resource prices, Canadians and their governments need to re-examine the adequacy of the federation’s adjustment mechanisms and how best to approach the broader policy challenges raised. This paper addresses the following question: What policies can Canadian governments enact to better manage our nonrenewable resources so that all Canadians benefit, including future generations, while still maintaining a functional economic and fiscal union?

In order to provide some answers to this question, we briefly review the research on Dutch disease and its consequences in the Canadian context. We examine the particular policy challenges presented by significant, prolonged upsurges in resource-sector activity. We conclude that the current tax and transfer systems in Canada are ill equipped to respond to these challenges, and propose policy options and prescriptions for the federal government and for the resource-rich provinces.

The pioneering research of Corden and Neary, which forms the basis of the theory of Dutch disease, identifies two main economic effects from resource booms: the spending effect and the resource movement effect.1 The spending effect relates to the spending of revenues gained from exporting natural resources. This can lead to an appreciation of the exchange rate, which makes it more difficult for other domestic traded goods sectors, primarily manufacturing, to remain competitive in international markets. This effect, which is the one most often emphasized, is larger when resource firms are domestically owned and when government spends, rather than saves, its share of resource revenues. The resource movement effect refers to the reallocation of labour and capital from manufacturing and nontraded goods to natural-resource production.

A resource boom may affect national economic welfare through its adverse effects on economic efficiency and equity. Resource production can reallocate activity away from an economy’s “core” sectors to the “periphery.”2 This shift can reduce overall economic efficiency if positive externalities that previously occurred in the core sectors – such as learning-by-doing productivity gains and the diffusion of technology and skills – are decreased or lost. These efficiency losses can be exacerbated in the case of a nonrenewable resource boom, because the economy may be permanently weakened by this reduced manufacturing capacity once the resource is exhausted.

Sachs and Warner argue that resource production can shift factors of production from sectors with high-productivity growth to sectors with low-productivity growth, thereby reducing the overall growth rate of the economy.3

Another source of inefficiency arises in the Canadian context because the bulk of government resource revenues go to the provinces. This enables resource-rich provinces to provide more and better public services at lower tax rates, which can be a further magnet for mobile labour and businesses. Resource-rich provinces might also use their windfall revenues to invest in infrastructure and business services as a means of diversifying their provincial economies, which could come at the expense of other provinces.

Natural-resource windfalls can also give rise to inequities, as there are inevitably winners and losers from such large economic shocks. In the case of resources, the winners are workers and governments in resource-rich regions. The negative impacts are mostly felt by workers from resource-poor regions, whose wages will be depressed as a result of the loss of economic activity (although the emigration of some workers to resource-rich regions will tend to mitigate this). Workers who choose to move to resource-rich regions can recoup at least some of their losses and may end up better off. Workers who lose their jobs are especially hard hit – particularly those with long tenure.

Finally, we would argue that future generations have as much of a moral claim to the benefits derived from public resource wealth as current generations. Their interests should not be overlooked in boom periods. When today’s Canadians allow the fruits of national, nonrenewable resource wealth to be spent and not judiciously saved or otherwise conserved, and when we exploit nonrenewable natural resources and cause permanent damage to the environment in the process, intergenerational equity is jeopardized.

Much of the recent research on Dutch disease in Canada underlines the urgency of the problem. Beine, Bos and Coulombe provide the most recent evidence that Corden-Neary Dutch disease factors are at work in Canada.4 They investigate the effects of the 2002-08 exchange rate appreciation on the manufacturing sector using a two-stage approach. They find that 42 percent of this appreciation was due to an increase in the value of resource exports from Canada, while the remaining 58 percent was due to exchange rate effects originating in the US, particularly the outflow of capital following the dot.com bust in the early 2000s. They also determine that 31 percent (roughly 100,000 jobs) of all manufacturing job losses during that period were attributable to Dutch disease (the Canadian component of the rise in the exchange rate) and 55 percent (around 180,000 jobs) were due to the US component. The remaining 14 percent (about 46,000 jobs) reflected long-term structural decline, mainly due to competition from emerging economies. Moreover Coulombe argues that while commodity-price-related exchange rate fluctuations in Canada play a stabilization role in the resource sector in the periphery, they tend to have the opposite effect on the traded-goods sector in the industrial core.5

These results can be compared with those of Shakeri, Gray and Leonard, who find output declines in 11 of 18 major manufacturing industries in Canada due to exchange rate appreciation.6 However, they do not distinguish between the Canadian and US components and therefore cannot determine what proportion of these declines is attributable to high energy prices. Clarke, Gibson, Haley and Stanford also provide evidence of Dutch disease in Canada.7 They show that the Canadian dollar’s partially resource-fuelled appreciation after 2000 led to a contraction of employment and production in nonresource-tradable industries, which had a negative effect on aggregate productivity.

Some observers dispute the presence of Dutch disease in Canada. For example, Krzepkowski and Mintz argue that the decline of the Canadian manufacturing sector is largely the result of competition from low-wage countries and weak productivity growth, rather than the booming resource sector.8 However, they do not provide econometric evidence of the relative effects of these different factors on manufacturing employment.

More recently, Gordon analyses the evolution of hourly earnings and employment in the Canadian manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors between 2002 and 2008. 9 Employment losses occurred in all classes of earnings below $35 per hour in the manufacturing sector, whereas most high-earning jobs created have been in non-manufacturing. More detailed data indicate that the service sector benefited from the largest job increases. These findings are consistent with the basic prediction of Corden and Neary’s model: a Dutch disease is characterized by a transfer of jobs from the manufacturing to the service sectors.

Regardless of the scale of negative impacts, there have also been clear upsides to the resource boom for Canada. Coulombe shows that improved terms of trade associated with the most recent resource boom accounted for nearly one-third of the improvement in Canadians’ overall living standards during the boom, thus compensating to some extent for the costs associated with the decline of the manufacturing sector.10

For our purposes, taken together the research offers two conclusions: first, Dutch disease effects matter for the Canadian economy; and second, with increased living standards in the aggregate from natural resources, there is scope for policies to spread their benefits more evenly throughout the country.

The challenges that arise as a result of resource booms are exacerbated by Canada’s federal structure and geography. There are several major dimensions to these challenges, which we outline below.

Economic shocks – abrupt shifts in economic conditions, along with their positive and/or negative consequences – are a fact of life in a modern economy. A government’s best response is not to prevent such shocks from working their way through the economy, but rather to help cushion their effects through the tax and transfer system and to design targeted policies as a way (albeit imperfect) for the winners to compensate the losers. Given the geographic concentration of natural resources in Canada, the effects of resource booms vary considerably from province to province.

In addition to the exchange rate channel, Canada has three main built-in mechanisms to respond to this kind of regional shock: intergovernmental transfers, a national progressive tax and transfer system and interregional migration. The effectiveness of each of these mechanisms in absorbing shocks is tempered, however, by our highly decentralized federation.

Equalization is the first line of defence against provincial economic and fiscal imbalances stemming from a prolonged resource boom. Section 36(2) of the Constitution commits the federal government to make equalization payments to provinces to compensate for differences in fiscal capacity and ensure the provision of reasonably comparable public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation. Such variations in fiscal capacity include those due to provincial resource revenues.

However, the effectiveness of equalization in responding to natural-resource shocks is limited by several factors. First, only half of natural-resource revenues are taken into account in calculating equalization entitlements, because of concerns about respecting provincial property rights and preserving economic development incentives. More important, while the fiscal capacities of have-not provinces are equalized upward to a given level, those of have provinces are not equalized downward, so the main source of horizontal imbalance is not addressed. The federal government’s capacity to equalize resource revenues is further constrained by the fact that it does not have direct access to that revenue base. And while equal-per-capita social transfers to the provinces, including the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) and Canada Social Transfer (CST), implicitly equalize provinces’ fiscal capacities (both upward and downward to some extent), they do little to address imbalances arising from natural resources.

Our progressive tax and transfer system is another buffer against regional economic shocks. The income tax system, unemployment insurance and other transfers can address the resulting inequalities, but only partially. While the federal tax and transfer system implicitly redistributes among provinces, it has limitations. Over the past few decades income tax collection has become more decentralized in favour of the provinces, whose own tax and transfer systems are less effective in mitigating market inequalities. On the tax side, as provinces have gained greater flexibility in setting their own income tax rates, they have generally adopted rate structures that are less progressive than the federal rates. On the transfer side, provincial welfare and disability benefits have not kept pace with increases in the cost of living.

Workers and businesses can respond to the interprovincial reallocation of economic activity due to a resource boom by moving to resource-rich provinces. In a decentralized federation, however, the resulting fiscal imbalances among provinces can encourage migration beyond the level justified by pure market considerations such as higher wages and the probability of finding work. In other words, the resource boom not only draws workers for economic reasons, but also causes fiscally induced migration because it allows resource-rich provinces to provide public services at much lower tax rates (so-called net fiscal benefits).11 As a result, workers who do not migrate generally face not only less favourable economic opportunities, but also lower levels of public services and/or higher tax rates than those who live in resource-rich provinces.

Provincial ownership of natural resources – and the implied right of provincial access to resource-specific taxes – is a unique feature of Canadian federalism. The Constitution Act of 1982 guarantees provinces the right to tax nonrenewable natural resources (as well as forestry and electrical energy). The power to tax resources is not exclusive to provinces, but they alone implement resource-specific taxes intended to claim returns from resource ownership, including mining profit taxes; oil and gas royalties; and sales of leases to explore, develop and extract natural resources. Provinces also have exclusive legal rights over resource management, from exploration to conservation.

By virtue of its broad taxation authority under the Constitution, the federal government is also able to tax natural resources indirectly. Ottawa obtains substantial revenues from natural-resource activity through general taxation on corporations and individuals, as well as through excise taxation. Finance Canada calculated in 2003 that at the end of the 1990s about one-quarter of combined federal and provincial resource revenues went to the federal government (divided roughly equally between mining and oil and gas) – this despite the favourable treatment afforded to resource industries through the federal corporate income tax system.12 The federal-provincial ratio may well have changed in the last decade as a result of corporate tax cuts, but the main point is that in practice, the provinces do not have sole access to natural-resource revenues.

Differences in natural-resource revenues can lead to substantial fiscal imbalances among provinces. Finance Canada calculates equalization payments based on each province’s fiscal capacity. As we showed in figure 3a, provincial fiscal capacities before equalization in 2011-12 varied from a low of 67percent of the national average in Prince Edward Island to a high of 166percent in Alberta. Moreover, some provinces have experienced a dramatic increase in fiscal capacity over the past decade, thanks to the resource boom. Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan saw their fiscal capacities jump from 67 to 153 percent and from 93 to 133 percent of the national average, respectively, transforming from have-not into have provinces. During this same period, Ontario’s fiscal capacity fell from 104 to 93 percent of the national average. Coulombe shows that these disparities in provincial fiscal capacities were largely due to changes in the provinces’ terms of trade relative to the rest of the world and the other provinces, rather than to provincial differences in productivity growth.13

Do Canadian provinces, as owners of their resources, capture enough of their rents for the public sector? The Alberta Royalty Review Panel argued that royalty rates had not kept pace with changes in the resource base and world energy markets; as a result, Alberta was not getting a fair share of revenues from oil and gas.14 They estimated that the total public-sector share of rents (from royalties and taxes for all levels of governments – including federal corporate taxes) – was 44 percent for conventional oil, 47 percent for oil from the oil sands and 58 percent for natural gas, with the remaining shares going to producers. The panel recommended increasing these public sector shares; the largest increase was recommended for the oil sands, from 47 to 64 percent, compared with five-percentage-point increases for conventional oil and for natural gas.

Given that these resources are publicly owned, why are public shares of rents so low? In the case of the oil sands, the panel’s report suggests one possible explanation is that royalty rates were initially set at low levels when the industry was small and struggling. Another is that, as a small open economy, Alberta is constrained from setting higher royalty rates by fiscal competition from other jurisdictions. Indeed, the panel acknowledged the need to be internationally competitive in setting these rates in order to continue to attract the necessary investments. The fact that resource taxes do not fall only on rents, but also apply to the normal return to capital, may explain the competitiveness pressures that Alberta’s government faces. If resource taxes really targeted economic rents, such pressures would be greatly diminished – after all, returns to capital are determined on world markets, and natural resources are immobile. Put differently, if the normal return to capital is excluded from the tax base, so that taxation is focused on rents, it will generally be neutral with respect to investment, even when capital is mobile internationally.

There may also be an element of political uncertainty at play due to the inability of provincial governments to commit to future royalty rates. If governments increase royalty rates when resource prices rise – which is often the case – resource firms face a policy-induced risk for which they must be compensated. This may be another reason why sales of leases do not fully capture the rents: the government’s inability to commit to constant royalty rates means that prices for leases must be set at relatively low levels so as to compensate producers for the risk of future increases in royalty rates. Whether federal direct access to resource taxation would lead to a higher proportion of rents being collected is an open question, but in principle, the federal government should face less competitive pressures than an individual province.

Of course, the fact that the provinces fail to collect a high enough share of resource rents does not aggravate Dutch disease. On the contrary, to the extent that resource firms are foreign-owned, the profits will be expatriated and exchange-rate-induced reallocations of factors reduced. However, some of the benefits of public ownership of natural resources would be lost in the process.

Despite the fact the share of resource rents they collect is less than optimal, provinces receive substantial resource revenues. How provinces manage these revenues has a bearing on the severity of Dutch disease. It is, therefore, troubling that provinces seem unable to save a significant portion of resource revenues for future generations. For example, while Alberta has a Heritage Fund, it accounts for a limited share of cumulated oil and gas revenues – around $16 billion in 2012, only 1.4 times the amount of annual nonrenewable resource revenues collected by the province. In comparison, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund was valued at $660 billion in 2011, roughly 12 times the annual government revenue from petroleum activities.15

While some of the resource revenues in Alberta have been used for capital investments – including human capital – a significant portion has been used to reduce taxes and increase current spending.16 Combined with the additional spending generated by provincial residents, this contributes to Dutch disease and to fiscal inefficiency and inequity in the federation.

Another reason why provinces might not be saving enough resource revenues is the temptation to use them for provincial economic development purposes, or province-building. Indeed, there are strong political incentives for provinces to pursue diversification strategies and major infrastructure investments. This may be a key factor in exacerbating the effects of Dutch disease in Canada.

In a similar vein, there is a natural urge to encourage processing of natural resources before exporting them as way to diversify economically. However, this is likely to exacerbate the symptoms of Dutch disease, because it increases the value of the resources exported (although it does not increase the value of resource rents available for the public sector). Dutch disease effects will tend to be amplified if processing activities attract production factors away from sectors with higher productivity growth or those that are better suited to exploiting agglomeration economies achieved through geographical clustering in other regions of the country.

How can governments design policies that would enable Canadians to share the fruits of natural-resource endowments? Political actors in resource-rich and resource-poor provinces, as well as at federal level, typically profess to have this objective. To achieve this, it would be desirable for the resource-rich provinces to have efficient rent collection and management policies that respect the rights of future generations, while at the same time minimizing adverse consequences on the resource-poor provinces. There are two main policy avenues available: more efficient taxation and better use of resource rents.

The existing provincial resource taxation regimes are not fully efficient revenue-raisers. In oil and gas, for instance, instead of more advantageous rent-based taxes, provinces rely on royalties that are set too low to collect a fair share of rents and often vary with price changes. Provinces need to adopt more efficient tax regimes that collect the bulk of rents without reducing the incentive to explore, develop and exploit resource properties.

Fortunately, there are established approaches that address this problem, such as the resource rent tax (RRT), touted by the Henry Report in Australia,17 and the allowance for corporate equity (ACE) tax, a European concept set out by Auerbach, Devereux and Simpson18 and recommended by the Mirrlees Review.19 When combined with competitive auctioning of leases, these regimes can be effective ways to collect resource rents for the public sector. Rent-based taxes allow the collection of rents at the production stage without affecting investment incentives. Lease auctioning is an efficient mechanism for collecting part of the expected rents before production starts, since firms are better informed than government about the expected value of those rents. It also places the burden of risk on firms, whereas rent taxes allow the government to assume some of the risk retrospectively.

Two pitfalls in implementing these tax changes ought to be acknowledged and addressed. First, governments should commit to a tax regime and maintain it regardless of price fluctuations in the future. The temptation to raise tax rates when prices rise compounds the uncertainty associated with resource-price volatility and exploration risks. Establishing stand-alone legislation might help, since it would raise the political cost of future policy changes, thereby increasing the credibility of the government’s policy commitment.

Second, losses should be treated symmetrically with gains – despite the fact that such full-loss offsetting is the exception for resource taxation around the world. Once again, Norway is a notable exception that illustrates the feasibility of a better system.

Resource revenues should provide adequate benefits to future generations. An effective way to do this is through sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), through which governments invest natural-resource revenues so as to generate returns that can be cashed in later, subject to clear rules for doing so. To formalize this approach, provinces could adopt legislated fiscal rules committing governments to deposit a pre-specified portion of resource revenues into an SWF. This would help governments resist pressures to spend rents in pursuit of short-run objectives. Investing the SWF in foreign assets, as is done in Norway, would help mitigate Dutch disease effects on other industries and regions due to exchange-rate shifts. A case can also be made for investing some rents in capital projects that generate long-term benefits, such as infrastructure and human capital – provided this does not exacerbate the excessive movement of production factors toward resource-rich regions.

Ultimately, however, the federal government is best placed to address the efficiency and equity issues that arise from Dutch disease and affect the broader national interest.20 The justification for federal intervention essentially draws on section 36(1) of the Constitution Act, which commits the federal government and the provinces to (a) promoting equal opportunities for the well-being of Canadians; (b) furthering economic development so as to reduce disparity in opportunities; and (c) providing essential public services of reasonable quality to all Canadians.

There are nevertheless important political and constitutional constraints on what can legally or practically be done. In suggesting federal-level policy options, we have respected provincial jurisdiction over resource development and resource-specific taxation. At the same time, we contend that even though the federal government cannot directly control the pace of resource development (aside from using regulation and through project approvals), it can and should intervene to address its unintended, adverse consequences.

The federal government has a number of policy options available to it, most of which require more emphasis on its coordination role within the federation.

The failure of the provinces to save enough of their natural-resource revenues is a serious problem. In principle, the federal government could establish its own SWF in which resource revenues would be invested and saved for future generations – an option recently discussed in a report of the Canadian International Council.21 But a federal SWF could not mimic a provincial SWF, so it would not undo the effects arising from insufficient saving and spending of resource revenues on the part of provinces. Another option, suggested by Shakeri, Gray and Leonard,22 would be to hold a higher proportion of the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) as foreign assets. This could potentially reduce the CPP fund’s exposure to risk associated with commodity price fluctuations, but it could also conflict with the independence of the CPP Investment Board.

Another option is simply to encourage resource-rich provinces to save more of their resource revenues. One lever that the federal government might use is intergovernmental transfers. For example, the equalization of resource revenues might be restricted to revenues that are spent instead of being saved. Provincial resource revenues put into a SWF would then be excluded from the equalization formula, and brought in only when the fund is drawn down. Of course, this approach would have to be carefully thought through to avoid perverse incentives for provinces to cheat the new system. The effectiveness of such a policy would depend on the extent to which it really induced higher net public saving. If provinces saved resource revenues in SWFs to shield them from equalization but simultaneously ran budget deficits, the effectiveness of the mechanism would be diminished.

Moreover, this proposal would only be effective if there were some reforms to the equalization system, for two reasons. First, resource-rich provinces are not equalization recipients, and the system is not designed to equalize their fiscal capacities downward. Second, the growth of the overall equalization budget is currently capped at the GDP growth rate and is therefore unaffected by changes in the formula.

Counterbalancing the adverse effects of resource-rich provinces’ economic development policies on other regions of Canada would be even more difficult. The federal government could invest in infrastructure to improve productivity in the traded goods sectors. In practice, however, this approach would only be effective if it reduced the diversion of factors of production away from the traded goods sector to the resource industries. That would entail a proactive industrial policy that effectively favours trading goods industries and presumes that the government is better than the marketplace at picking winners, which is unlikely.

Adding more value to raw resources before exporting them is another option that is often raised. As we have said, this might easily prove a bad policy: unless refinery activities were concentrated in the core and generated high productivity growth, such value-added would only exacerbate the effects of Dutch disease. Nevertheless, it may provide an opportunity to spread the benefits of a resource boom to other regions. Dodge and Dodge, Burn and Dion23 recently proposed a variant of this argument. They suggested providing active support for refurbishing existing natural-gas pipelines from Alberta to central Canada to transport oil to eastern refineries as a way to bring some of the industrial activity associated with oil sands exploitation to firms in central Canada. As of August 2013, TransCanada is moving forward on this proposal, subject to regulatory approval.

This highlights another issue, which is particularly relevant in a decentralized federation whose provinces span six time zones. For the most part, final users of natural resources are some distance from where the resources are extracted. Transportation infrastructure is required to get the resources to market, and this typically requires moving them across provincial borders. The fact that provinces enjoy exclusive legislative jurisdiction over resource management gives rise to coordination problems among the provinces affected. The federal government is well positioned to play a coordination role in this regard.

More provocatively, Dodge et al.’s eastern pipeline option is part of a broader proposal for federal investment in building productive and fiscal capacity in all provinces, especially low-income ones. Their argument is based on the view that compensating provinces for deficiencies in fiscal capacity through equalization and other transfers will be insufficient to meet the commitments of section 36(2) of the Constitution, given the growing disparities Canada has been experiencing. Instead, they argue, these fiscal inequalities must be addressed proactively. Federal infrastructure investment is a potential policy instrument for this purpose. However, this would require concentrating federal contributions in non-resource-rich, low-income provinces, whereas the established convention for federal infrastructure grants has essentially been to allocate them on an equal-per-capita basis across provinces.

Finally, the reallocation of activity from nonresource tradables to the resource sectors as a result of the boom may create unemployment and earnings losses for displaced workers, due to the difficulty in transferring skills across sectors. This has implications for labour market policies, including the need to provide temporary income support as well as retraining and labour market information. It also suggests a role for the federal government in addressing quite diverse labour market circumstances and ensuring policy coherence across provinces.

To sum up, some of the implications of the growing resource sector for the Canadian economy call for a stronger federal influence on the allocation of economic activity across industries and across regions. While different policy instruments are potentially available, a more active federal industrial policy (using targeted infrastructure investment, for example) would be justified in the current context, despite the potential complications. From a national perspective, there is no reason why spending on infrastructure and human capital should be restricted to the provinces in which resource rents are generated. Moving away from an equal-per-capita allocation of federal investments across provinces, while a deviation from established practice, could help counterbalance excessive reallocation of production factors driven by growth in the resource sector.

The federal government is constitutionally responsible for addressing horizontal fiscal imbalances among provinces through the federal-provincial transfer system. The current imbalances are unprecedented, and if not addressed will lead to sizeable fiscal inequities and significant fiscally induced migration. If all Canadians are to benefit from the resource boom, these imbalances must be addressed by the federal government.

There is a lengthy and contentious literature on the equalization of resource revenues in Canada; here we highlight two issues. The first is the perceived conflict between the federal government’s constitutional equalization commitment and the provincial ownership of resources. Those who give primacy to provincial property rights also argue that natural-resource revenues should be treated as implicit income of provincial residents and should be taxed at the federal income tax rate.24 The second is that attempting to equalize natural-resource revenue may act as a disincentive for provinces to develop their resources.

Several panels and commissions have reached different conclusions over the years on how best to resolve these competing interests. And although there have been many changes in the treatment of resources revenues since the equalization program was established in the late 1950s, the principle that those revenues should be substantially equalized has typically been recognized in practice, albeit with some special provisions to account for incentive effects and other issues. For instance, in some years, less than 100 percent of resource revenues were equalized, while in others, the fiscal capacity standard to which recipient provinces were equalized was based on a 5- rather than 10-province average. Moreover, special provisions have been applied for natural resources whose ownership is highly concentrated in a small number of provinces (e.g., offshore oil and gas).

The current equalization framework is based on the main proposals of the Expert Panel on Equalization and Territorial Formula Financing (2006).25 A 10-province standard is used, but only 50 percent of resource revenues are included in the base. This approach ensures that provinces retain some net fiscal benefits from extracting their natural resources. In 2009, the federal government, concerned about the impact of elevated resource prices on the cost of the program, capped the growth of total equalization payments to nominal GDP growth.

In addition, equalization has always been based on a gross rather than a net mechanism: provinces with below-average fiscal capacities are equalized upward, but those with above-average fiscal capacities are not explicitly equalized downward. As a result, significant fiscal disparities remain among provinces even after equalization payments (see figure 3b).

However, the full extent of equalization among provinces in Canada extends beyond the equalization program. It also depends on the design and amount of health and social transfers (the CHT and CST) and the relative share of revenue-raising between federal and provincial governments. A more centralized system, where the federal government raises more revenues than it needs for its own programs – including equalization – and transfers the balance to provinces on an equal-per-capita basis, partially equalizes a portion of provincial revenue capacities on a net basis (because more federal revenues are raised in provinces with above-average fiscal capacities, in per capita terms). This is currently how health and social transfers function. Conversely, a more decentralized revenue-raising system increases horizontal fiscal disparities and puts more stress on the equalization system.

All that said, it is our view that the current system of federal transfers is not capable of addressing the large fiscal disparities resulting from natural-resource booms. As currently designed, equalization cannot undo imbalances between have and have-not provinces. It is becoming increasingly difficult for the federal government to finance full equalization commitments with only limited access to the main source of imbalances. The GDP growth cap on equalization reflects this difficulty. While health and social transfers do contribute to equalization, they have little equalizing effect on resource revenues.

Four key ingredients are required to deal with fiscal imbalances and the shortcomings of the current equalization system. The first is simply to maintain the integrity of the equalization system, despite affordability concerns raised in light of the large increases in provincial natural-resource revenues in recent years. We believe the traditional approach to equalization should be restored: that is, the total equalization budget should be fully formula driven, rather than subject to discretionary caps. A well-functioning equalization system is absolutely critical for ensuring that any surge in resource-sector activity benefits all Canadians.

There is no fiscal justification for the current GDP growth limit, which effectively shifts revenue-raising responsibility from the federal government to the have-not provinces. Fiscal sustainability analysis by the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) – which takes into account the announced reductions in CHTs to the provinces and other recent expenditure restraint measures – suggests that the projected fiscal position of the provinces is much weaker than that of the federal government. Specifically, the PBO finds that while the federal government’s books are sustainable over the long term (with fiscal space equal to 1.3 percent of GDP to increase program spending or reduce taxes), the provinces as a whole face an unsustainable budget outlook.26

A second ingredient for addressing interprovincial fiscal imbalances is to maintain the federal government’s share of the income tax. Indeed, the more tax room is decentralized to provinces, the greater the horizontal imbalances are likely to be and the more difficult they will be to address. In addition, more decentralized personal income tax collection is also likely to be less progressive. A national, progressive income tax structure is therefore an important element in a federal system designed to ensure that economic shocks do not lead to unacceptably large inequities.27 Put simply, greater federal tax room allows for more equalization, including larger health and social transfers.

While equal-per-capita health and social transfers do provide an element of equalization, a more proactive approach should be taken in light of the deficiencies of an equalization program faced with vast disparities between have and have-not provinces. The third ingredient is to adjust transfers to have-provinces according to their fiscal capacity, while being careful not to undo their role in supporting good social programs with guaranteed minimum national standards. For example, CHTs and CSTs to a province whose fiscal capacity (including equalization payments) is above average could be reduced by an amount equal to some proportion of the gap between that province’s fiscal capacity and the national average, as proposed by Courchene.28 While the fiscal capacities of have provinces (including all federal transfers) would still remain above the national average, the gaps between their fiscal capacities and those of have-not provinces would be reduced. This would effectively move the transfer system closer to a net equalization system, like those in other federations such as Germany and Australia, or to the fiscal status of regions in unitary nations such as Sweden.

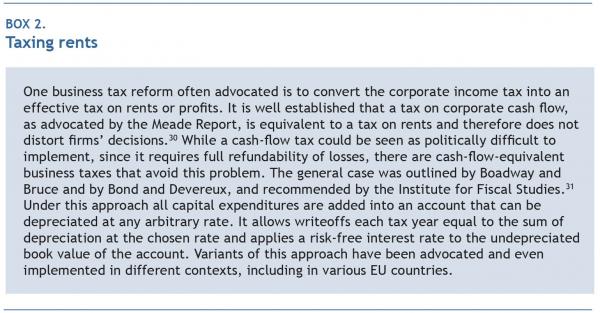

The fourth and final ingredient is to enhance the federal share of resource revenues so as to increase Ottawa’s capacity to address fiscal imbalances. We recommend reforming the corporate tax system along the lines proposed in the context of major international reports on tax reform29 and implemented in several countries (including Belgium, Croatia, Italy and Brazil). In general, these reforms aim to refocus the corporate tax system on directly taxing pure profits or rents generated by economic activity, rather than taxing corporate shareholders’ income.

These reforms are ideal for Canada, serving both to make the corporate tax system more efficient and to enable the federal government to obtain a greater share of resource revenues, without specifically targeting the resource sector (see box 2 for more details). The basic principle of the federal government acquiring a share of natural-resource revenues is well established, as long as it does not explicitly discriminate against resource industries.

In reality, Canada’s current system does the opposite. While the same general rules apply to resource and nonresource industries, some resource-specific measures end up providing favourable treatment for the resource sector. These include accelerated capital-cost allowances, generous deductions and tax credits for exploration and development expenditures, full deductibility of royalties and mining taxes against corporate taxable income, and flow-through share financing.32 As a result of all of these tax provisions, not only does the federal government effectively encourage resource investment relative to investment in other sectors of the Canadian economy, but it also forgoes substantial tax revenues that it could legitimately collect from resource industries. In a 2003 report Finance Canada estimated that effective tax rates on capital are significantly lower for resource-based industries than for others, such as manufacturing.33 For instance, in the report Finance Canada estimated that the marginal effective tax rate on capital in the oil and gas sector was 13.6 percent, decreasing to 8.7 percent as a result of the resource taxation review of the 2003 budget. Marginal effective tax rates in the mining sector were estimated to be even lower.

Several additional changes could be made to the corporate tax system to make it fairer, more efficient and potentially able to generate more revenue for the federal government. One option is to eliminate the deductibility of resource taxes from the corporate tax base, which, apart from being an unnecessary transfer from the federal government to the provinces, distorts the tax system.34 In fact, the deductibility of resource taxes may be a disincentive for provinces to reform their resource-taxation regime toward more efficient rent-type taxes.35

The advantage of a rent-based taxation approach is that it avoids the inefficiencies of the current business tax system documented in the Mintz Report, such as discouraging investment, favouring resource industries, encouraging debt finance and not being fully integrated with the personal income tax system.36 Such a reform would also reduce variations across industries in marginal effective tax rates on capital, as estimated by Chen and Mintz.37 This would improve the allocation of investment across industries, thereby increasing aggregate productivity in Canada.

A tax on rents would capture revenues for the public sector from rents or pure profits generated from all sources, including monopoly rents, resource rents, locational rents and rents due to special advantages. It would also generate for the federal government a share of resource rents using a tax that is not explicitly discriminatory, and would thereby contribute to the federal government’s ability to address fiscal imbalances arising from natural resources. Finally, a rent-based corporate tax would significantly mitigate the tax competition pressures that lead to lowering corporate tax rates internationally, because normal returns to capital would not be taxed.

Canada is a country blessed with bountiful nonrenewable natural resources. Given such good fortune, it ought to be possible to use these resources in a way that benefits all Canadians. Yet there is much concern that the scale and pace of exploitation of natural resources is a mixed blessing. Various pejorative terms have been used to express this idea, such as “Dutch disease” and “resource curse.”

Our aim in this paper has been to analyze the various reasons why a natural-resource boom might have detrimental consequences, and what policy responses might mitigate them. We have suggested three main reasons why this type of apparently positive economic shock may have negative side effects, if it is not accompanied by an adequate policy response. First, a resource boom can lead to production adjustments that engender economic inefficiencies. For instance, if factors of production are diverted from manufacturing and other industries in the core of the economy to natural-resource production in the periphery, agglomeration externalities in the core may be lost and not replaced by new activity in the periphery. In the long run, this can slow productivity growth in the economy overall. This is the essence of what is typically meant by Dutch disease.

Second, as with any economic shock, there will be winners and losers from a resource boom. The best response for governments is not to prevent the shock from working its way through the economy, but to use policy as a way, albeit an imperfect way, of having the winners compensate the rest. There are some built-in elements of the economy that reduce the severity of the damage to those negatively by the shock. One is the progressive tax and transfer system that naturally redistributes from those whose incomes rise to those whose incomes fall. This is supplemented by social protection policies that help those who lose their jobs. Another is the system of federal-provincial transfers that insures provinces against a decline in their fiscal capacity resulting from an economic shock. A final element is the migration of workers from one region or job to another.

Third, in a large decentralized federation where natural-resource wealth is concentrated in some regions and where provinces have the first claim on resource revenues, there are other potential sources of inefficiency and inequity. Provinces seem to have difficulty obtaining a large enough share of resource rents through their tax, royalty and leasing policies. Very little of the resource revenues that they do obtain is saved for future generations, who have as much claim to the common ownership of resources as current generations. Instead, these revenues are used either to reduce other taxes or to increase provincial government expenditures. The potential results are (1) individuals and businesses may be lured by purely fiscal benefits to resource-rich provinces, resulting in an inefficient regional allocation of resources; (2) those that do not move may face lower levels of public services at higher tax prices, a situation of horizontal inequity; and (3) provinces are prone to using their revenues for province-building purposes by investing in infrastructure and business services, thus tempting even more economic activity away from other provinces.

All of these problems prevail in the Canadian federation to some extent. There is evidence of Dutch disease in the Canadian economy, and the resource boom of the past decade has led to growing economic and fiscal disparities between resource-rich and resource-poor provinces. Faced with these problems, we have suggested the following policy responses that we believe governments in Canada, especially the federal government, need to consider:

These options respect provinces’ jurisdiction over resource development and their right to levy resource-specific taxes. At the same time, the federal government has important efficiency and equity obligations, as stated in the Constitution. Even though it has limited control over the pace of resource development, Ottawa can and should intervene to address its unintended, adverse consequences.

IRPP Insight is an occasional publication consisting of concise policy analyses or critiques on timely topics by experts in the field.

To cite this study: R., S. Coulombe and J.-F. Tremblay, Canadian Policy Prescriptions for Dutch Disease. IRPP Insight 3 (October 2013). Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IRPP or its Board of Directors.

All publications are available on our Web site at irpp.org. If you have questions about our publications, please contact irpp@nullirpp.org.

For media inquiries, please contact Shirley Cardenas (514) 787-0737.

This paper draws on some material from our article “The Dutch Disease and the Canadian Economy: Challenges for Policy-Makers,” prepared for “Thinking Outside the Box: A Conference in Celebration of Thomas J. Courchene,” Queen’s University, October 26-27, 2012. We thank France St-Hilaire and Stephen Tapp for their comments, which markedly improved the paper.

Rrobin Boadway is an emeritus professor of economics at Queen’s University.

Serge Coulombe is a professor of economics at the University of Ottawa.

Jean-François Tremblay is an associate professor of economics at the University of Ottawa.

Montreal – Canada’s tax and transfer system needs adjustment to better respond to the various fiscal and economic challenges posed by resource booms, say Robin Boadway, Serge Coulombe and Jean-François Tremblay, the authors of a new publication released today by the IRPP.

The authors show that the global resource boom of the past decade has widened economic and fiscal disparities between the resource-rich and resource-poor provinces, and they question whether our federation’s adjustment mechanisms are up to the task.

As a highly decentralized federation, Canada faces unique challenges in managing its resource wealth. Provinces own, manage and tax their natural resources and raise most of their own revenues. As a result, strong global resource prices translate into large differences in economic growth and fiscal capacities across the provinces.

The federal government is constitutionally committed to address these repercussions. “While Ottawa can’t directly tax resources and has limited control over the pace of resource development, it can and should intervene to address the unintended, adverse consequences” said Boadway, a noted fiscal federalism expert at Queen’s University.

The authors recommend that to manage Canada’s resource wealth more responsibly and for the greater benefit of all Canadians, governments should:

As Serge Coulombe, professor of economics at the University of Ottawa, points out, “We need to adopt a longer-term perspective on these important resource issues – future generations of Canadians have as much of a moral claim to the benefits derived from public resource wealth as current generations.”

-30-

Canadian Policy Prescriptions for Dutch Disease, by Robin Boadway, Serge Coulombe and Jean-François Tremblay, can be downloaded from the Institute’s Web site (irpp.org).

For more details or to schedule an interview, please contact the IRPP.

To receive our monthly bulletin Thinking Ahead by e-mail, please subscribe to the IRPP’s e-distribution service by visiting our Web site.

Media contact: Shirley Cardenas | tel. 514-594-6877 | scardenas@nullirpp.org