Following 9/11, renewed efforts have been made to increase the integration of the Canadian and American economies. Part of this drive has been focused on the need to increase security within North America. Another has been focused on the need for a customs union or a common market between the two coun- tries. These proposals are meant to expand current trade arrangements to incor- porate the establishment of a common tariff against third countries and to allow the free movement of capital and labour between Canada and the United States. Alan Green’s study deals with the consequences of the latter.

One of the implicit assumptions in the proposal to allow for the free move- ment of labour between the countries is that we are dealing with two closed economies. This is clearly not the case. For example, immigration into Canada over the last half century has rivalled that of earlier peak inflow decades, while immigration into the US during the last three decades has exceeded that of any decade in the last century. In Canada, immigration now accounts for about two- thirds of population growth. Hence, any move toward free movement of labour between the two countries must take into account the effects of immigration and immigration policy on labour-market integration.

The question, then, is this: If there is to be labour-market integration, since immigration plays an important role in it, whose immigration policy will prevail? On the basis of size alone, it is reasonable to assume that the main regu- latory provisions concerning how many people are to be admitted and who those people should be will more closely follow the US model than the Canadian one. This is an important assumption, since in the 1920s, the US adopted a very different approach to that of Canada. US immigration policy imposed a quota system that apportioned the inflow across countries in a way that was biased toward immigrants from the traditional source areas of north- western Europe. Canada, however, did not set a quota for admission but adopted a more flexible immigration policy according to which the annual inflow was tied to the state of the Canadian labour market. Nevertheless, Canadian immigration policy was as discriminatory as that of the US, as it favoured the US, the UK and north-western Europe. Both Canada and the US adopted a more universal admission policy during the 1960s.

In this paper, Green adopts a counterfactual approach – a “What if…?” historical methodology – to analyze what would have happened to the Canadian economy had Canada adopted US immigration regulations at the start of the last century. He has selected three periods for study: the years of Western settlement (1870-1914), the interwar years (1919-39), and the post-Second World War period. With US versus Canadian immigration policy, it is unclear what the outcome of the first period would have been. Probably Canada would have had a smaller total population, slowing the settlement of the West. In the second period, the adoption of the US immigration policy of fixed annual quo- tas would have meant a loss of flexibility in levels of inflow. This flexibility served Canada well in the post–Second World War period, as the country went through a major structural transformation from a resource-based to an industrial-urban economy. In addition, an independent immigration policy allowed Canada to introduce the point system in the 1960s. The US has no such policy.

In addition to examining the three periods, Green studies the impact of immigration flows on technological change in Western agriculture in the 1920s and on long-run manufacturing growth. His findings show that high levels of immigration in Canada slowed the transition to a modern farm sector in the West and differentiated Canada’s growth path from that of its neighbour to the south.

Finally, the author reports on two recent studies that examined the role of immigrants as “shock troops” in the process of structural change in the economy. Both studies concluded that immigrants eased the transition by moving into and out of the affected sectors faster than their native-born counterparts. As a result, immigrants helped to lower the cost of transition and so contributed to a rise in the standard of living. US immigration policy, with its fixed annual quota model, could not have responded as rapidly to structural change.

This study suggests that immigration has had a profound influence on long-run economic and social development in this country. Immigration will play an increasingly important role in shaping Canada’s future, and, Green argues, it is imperative that we maintain sovereignty over this vital area of national policy.

Since 9/11, debate has revived over the possibility of a greater economic integra- tion of Canada and the United States. Two recent studies (Dobson 2002 and Goldfarb 2003) have suggested that to facilitate this integration, a single North American labour market should be created, one that permits the free flow of labour between the two countries. This would unquestionably have some benefits for the operation of the labour markets in Canada and the United States. But the studies do not address one problem: both countries have fairly vigorous immi- gration programs. For example, between 1950 and 2000, the US admitted 25 mil- lion documented immigrants, while Canada admitted about 8 million. Any plan to integrate North American labour markets must therefore deal with this open- ness to external supplies of labour and the economic issues — to say nothing of the social and security issues — associated with large population flows.

Any move toward a more integrated North American labour market would require a harmonization of Canadian and American immigration policies. For example, if one country wished to shut down its immigration inflow while the other did not, immigrants could first enter North America via the open country and then move to the closed country. Even if this problem were overcome, con- sider the problems that would emerge if the desired composition of immigrants — selected either by source region or by skill — were different in each country.

In order to investigate the implications of such a situation, I will start from an extreme position: in negotiations to reconcile policy differences, Canada would end up adopting American-style regulations governing the admission of immigrants. This is not an unreasonable projection, given that over the last half century the US admitted over three times as many immigrants as Canada did; that is to say, 25 million compared with our 8 million immigrants. The question is, would such an outcome affect the economic (and social) development of the country? The short answer is “Yes.”

In examining this conclusion, it is useful to adopt a historical approach, because the effects of immigration are potentially very large, and it takes time for them to work themselves out. Moreover, the impact of immigration on the economy is subtle, and so it is difficult to evaluate fully in the short run. Hence, to understand how a particular policy regime influences events, we need to examine how such policies have evolved. Once we have understood how immigration policy has been used in the past to help solve specific problems, we can then better understand how the absence of a domestically derived immigration policy may have changed the very nature of long-term economic development in this country.

In this paper, I will address the question of how Canada’s handling of par- ticular economic problems would have produced different economic outcomes had this country adopted US immigration regulations during the last century. I will also discuss the question of whether the adoption of US immigration policies would have aided or hindered Canadian development. The evidence gathered from this exercise suggests that to adopt a particular immigration policy is to choose a development path, and that having such a choice has benefited Canada in at least two ways. First, immigration reduced the cost of structural change; second, the adoption of the point system in 1967 proved to be of critical importance at that juncture in Canadian economic history. In essence, Canada would have been a very different country if it had adopted the US approach to regulating immigration. Therefore, any proposal that Canada open its borders to the free movement of labour between it and the US, thereby surrendering control over the formation of its own immigration policy, should be treated with a great deal of caution. It is not clear that such a move would be in Canada’s best long-term interests.

Two approaches to North American labour-market integration have been suggested. Wendy Dobson proposes that Canada enter into a common-market agreement with the United States (2002). Under such an arrangement, both countries would agree to the free movement of goods, services and capital and to the establishment of a single external tariff against third countries. Danielle Goldfarb, however, takes a more cautious approach by recommending that Canada enter into a customs-union agreement with the US (2003). The two countries would agree on a common set of tariffs on a range of traded goods, and the agreement would eliminate tariffs between them. But even Goldfarb’s approach suggests that some form of North American labour-market integration be implemented to sweeten the negotiations over the formation of a customs- union agreement. The focus of this paper is on the potential consequences of such labour-market integration, regardless of how it is attained. We begin with a brief examination of the long-run trends in immigration to the two countries.

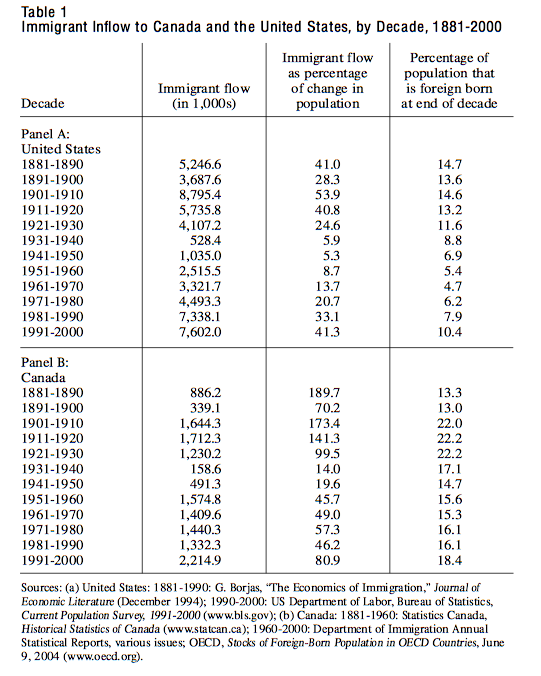

Table 1 sets out by decade the size and contribution of immigration to Canada and the United States over what might be called “the long twentieth century” — that is, from 1880 to 2000. The most striking feature of this comparison is the revelation that immigration played a much larger role in Canada’s population history than it did in that of the United States. For example, in terms of immi- gration’s contribution to population growth — the total immigration inflow for a given decade divided by population change during the same period — the Canadian rate is higher than that of the US, sometimes considerably. In the 1880s, and again during the first two decades of the twentieth century, the ratio for Canada was greater than 100. This implies that population churning was tak- ing place: people were moving in and out of the country in large numbers rela- tive to the change in the population stock. During the 1880s, this churning was associated with large-scale emigration from Canada to the United States as Canada was experiencing large gross inflows of foreign population. The same cir- cumstances prevailed in the 1890s, except that the inflow of immigration was drastically reduced due to poor economic conditions in Canada.

However, the high ratios of immigration to population change during the first three decades of the twentieth century were associated with high levels of net immi- gration (gross immigration minus gross emigration) as opposed to the high levels of net emigration that dominated the last three decades of the nineteenth century. These three decades were a period of rapid economic growth, due to the settlement of the West and the emergence of wheat as Canada’s leading export commodity during the last half of the 1920s. Hence, even when economic conditions improved in Canada, the population turnover — much of which was associated with ongoing outflows to the United States — continued. These large population flows undoubtedly eased the transition to a national economy by providing Canada with a safety valve (the exo- dus to the US) during periods when economic conditions made the inflow of new labour difficult to absorb and threatened to lower wages or raise unemployment.

The US experience (panel A) during these decades was quite different from that of Canada. In no decade covered in table 1 did the ratio of immigration to population change exceed 100 percent. It may have been that in earlier decades, when the US was still largely underdeveloped and underpopulated, it had rates in excess of 100 percent, as Canada did in the period after 1880. However, it is worth remembering that Canada’s large inflow and outflow of population is unique. In fact, between 1880 and 1930, the US, unlike Canada, did not expe- rience a prolonged period of net emigration. Apparently, then, immigration played a smaller and less volatile role in the demographic history of the US over the last century than it played in the history of Canada.

The sharp drop in the contribution of immigration to population change that took place in the US after 1930 was due not only to the poor economic conditions of the 1930s but also to the restrictions placed on the intake of immi- grants — 150,000 a year, as set out in the Quota Act of 1924. Canadian immi- gration regulations did not limit the inflow of immigrants, but during the 1930s and 1940s, the inflow was affected by poor economic conditions and by the impact of war on the international movements of migrants. Yet gross immigra- tion contributed more to Canada’s population growth than it did to that of the US during the same period (see table 1, column 2).

This Canadian pattern of higher inflows relative to population size per- sisted after the war. By the 1950s, immigration to Canada accounted for just under half the total population growth — 45.7 percent. The ratio for the US dur- ing the 1950s was about 9 percent. As the postwar period went on, this ratio rose sharply, reaching 80 percent in Canada and 41 percent in the US by the 1990s. Falling fertility rates combined with rising levels of immigration accounted for these figures.

The net effect of these immigration flows on population change can be seen in the columns showing the share of the foreign-born population relative to total population in Canada and the United States at the end of each decade (table 1, column 3). Except during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, Canada’s share of the foreign-born population exceeded that of the United States by a margin of two to one. For example, throughout the postwar period, the Canadian ratio was more than double the US ratio. This is further proof that over the course of the last century, immigration has contributed more to population growth in Canada than it has in the US.

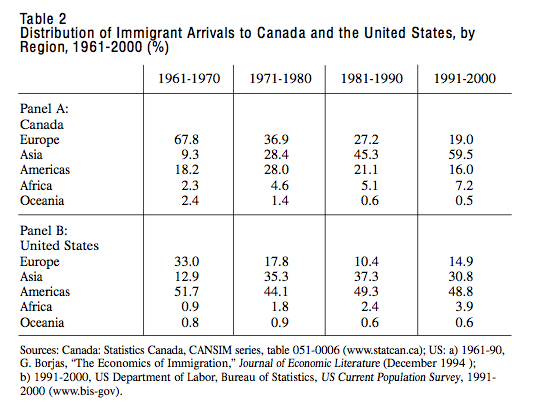

Table 2 sets out the distribution of immigrants arriving in Canada and the United States from five broad regions (Europe, Asia, the Americas, Africa and Oceania) by decade totals from 1961 to 2000. During this period, both countries wit- nessed a dramatic change in their sources of immigration.

Beginning in the 1970s, the share of arrivals from traditional source areas declined sharply. For example, in the 1960s, two-thirds of all arrivals to Canada came from Europe; by the last decade of the twentieth century, this figure had fallen to 19 percent. The US saw a similar downward trend in this period, although its initial share of immigrants from Europe was only 33.8 percent — roughly half the figure for Canada. Right from the start, then, the postwar immi- gration experiences of the two countries were very different, with Canada draw- ing a much larger share of its foreign labour supply from Europe in the early postwar years than did the US. This was mainly due to large inflows to Canada from Britain before 1970. The US drew its foreign labour supply from a wider geographic area. This is most noticeable in the higher share of people immigra- ting to the US from places like Mexico and Central America — 51.7 percent chose the US, while 18.2 percent chose Canada.

With the abandonment of discriminatory immigration policies in the 1960s (1962 in Canada, 1965 in the US) came the shift to nontraditional immigration sources. Both countries saw a sharp rise in immigration from Asia, but even here, the Canadian case is different. The percentage of arrivals from Asia to Canada increased from 9 percent in the 1960s to about 60 per- cent today. Although the share of immigrants to the US from Asia rose from 13 percent in the 1960s to 30 percent in the 1990s, the change was not as dramatic as for Canada over the same period. Furthermore, the share of Asian immigrants to the US has stabilized at about 30 percent, while Canada’s share continues to rise.

Not surprisingly, documented (to say nothing of undocumented) arrivals from the Americas — especially Central and South America — have continued to choose the US over Canada. Moreover, the US share of arrivals from this broad region has been relatively constant since the 1970s, while the Canadian share has declined from 28 percent in the 1970s to 16 percent in the 1990s. This is in sharp contrast to the share of immigrants from Asia, which has increased dra- matically for both countries — particularly for Canada, where the figure is now almost 60 percent. Finally, it is worth noting that over the last three decades the share distribution across regions has been fairly stable for the US but not for Canada, again illustrating the differences in immigration patterns between the two countries during the post-Second World War period.

The concept of “What if…?” — or counterfactual history — has a long and noble tradition among economic historians. For example, the assertion that inferior entrepreneurship retarded France’s economic growth implies that had the French economy been managed by a business elite, its growth would have more impres- sive (O’Brien 1977, 23). Historians use the same device. They often play with the idea of how different the world would have been if Napoleon or Hitler had not ascended to power, or if Britain had not entered the First World War. The mod- ern use of counterfactual history by economic historians began when Albert Fishlow and Robert Fogel almost simultaneously posed the same question: How different would American development in the nineteenth century have been with- out the railroad? (Fishlow 1965; Fogel 1964). In other words, what if the US had been forced to rely on the old technology of canals and roads? Both historians were examining the widely held belief that the railroad was indispensable to the nation’s economic growth. Although they chose different periods to test this proposition (Fishlow chose 1859 and Fogel 1890), their conclusions were the same: if the railroad had not existed, the impact on the economy would have been small. Edward Chambers and Donald Gordon (1966) reached a similar conclu- sion when they estimated, using a counterfactual approach, the impact of wheat exports on Canadian economic growth during the first decade of the twentieth century. Like Fishlow and Fogel, they found that the contribution of exports to the observed growth in average income was small. These findings suggest that economies have more than one path to long-term economic development.

I use the counterfactual concept here as a means of rethinking how immi- gration policy has shaped long-run developments in Canada. The question is: What if Canada, at the start of the twentieth century, had adopted the American model of regulating immigration, and how would that have influenced events in Canada over the ensuing century? I will address the question by examining how an alternative immigration policy would have influenced Canadian develop- ments in the last century.

A caveat: To have any validity, a counterfactual proposition must include a plausible alternative. For example, in the Fogel/Fishlow case, canals were an alter- native to railroads. We certainly have one here. Given the similarity of Canadian and US immigration policies in 1900, it would not have been difficult for Canada to adopt American regulations governing admission. Both countries took a laissez- faire approach to immigration; only paupers, criminals and the sick were turned back at their borders. In essence, both countries sought to exclude only those immigrants who were likely to become public charges or spread communicable diseases. Second, there was a general belief, especially in Canada, that large-scale immigration raised the standard of living of the resident population through gains associated with unexploited economies of scale, the result of an increase in the size of the domestic market (see Green and Sparks 1999). Third, although both countries were beginning to worry about the changing source of immigration as the share of immigrants coming from central, eastern and southern Europe rose, they were doing little to control the flow from these regions. Fourth, reciprocity, or free trade, was still a goal of Canada’s manufacturing community, and if it had been attained, then the free movement of labour between the two countries would have seemed a perfectly viable option. Finally, an effective border-patrol system emerged only gradually between 1900 and 1914 (Ramirez and Otis 2001). Before that, individuals could move relatively freely back and forth across the forty-ninth parallel — for example, a native of Halifax could simply board a ship in Halifax harbour and sail to Boston to look for work. Hence, the conditions for the cre- ation of a common market were present.

What if, on January 1, 1900, Canada had decided to adopt American immigration regulations and maintain a single or harmonized immigration policy for the balance of the century? Would this decision have altered the path of Canadian development in the twentieth century? The evidence I will set out suggests that the answer is “Yes.”

The goal of immigration policy during this period was to encourage farmers, farm labourers and female domestics to settle the Canadian West. The search for farmers was concentrated in Britain, the United States and northwestern Europe. To facilitate its search, the government adopted a vigorous advertising campaign, disseminating pamphlets outlining the benefits of settlement in Canada. The most famous of these was entitled “Canada: The Last Best West.” In addition, the government placed immigration agents throughout Britain, in selected European countries and in almost every state in the US; it also partially subsidized the tra- vel expenses of prospective immigrants, especially expenses incurred within Canada. Government representatives met immigrants at various entry points and escorted them to their destinations. This process of persuading immigrants to settle in Canada was part of a set of policies, referred to collectively as the National Policy, that included placing high tariffs on imported secondary manu- factured goods, completing a transcontinental railway (the CPR) and introducing measures to encourage the settlement of the West (see Green 2000).

The United States did not adopt a settlement-promotion policy. It did not need to. Between the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) and the outbreak of the First World War, more than 50 million people left Europe for overseas destina- tions. The United States absorbed over 60 percent of them. Canada, even with its recruitment schemes, attracted only 8 percent (Hatton and Williamson 1994, 4). Nor did the US have a policy to encourage settlers to head west. The reason was simple. A report in the 1890 US census declared that the frontier was closed, meaning that nowhere in the West was the population density low enough per square mile to justify defining the region as “frontier land.” In addition, the US, unlike Canada, did not have a set of polices promoting national development. In fact, in 1891, the US Immigration Act was amended to include, among other things, a “ban on all advertising for the purpose of encouraging immigration” (Timmer and Williamson 1998).

Other differences existed, and one of the biggest concerned immigrant ori- gins. More than three-quarters of immigrants to Canada came from Britain and northwestern Europe; the number of immigrants from these places who chose the United States was much smaller. In fact, beginning in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the share of immigrants arriving in the United States from central, eastern and southern Europe increased dramatically. Hence, the majority of immigrants to Canada came from the most industrialized — and therefore the highest-wage-paying — countries in the world, while most new immigrants to the US came from parts of the world, like southern and eastern Europe, with low-wage agricultural economies.

By 1900, the United States had emerged as one of the world’s leading indus- trial nations. But Canada — west of Manitoba, at least — was still largely empty. It stood at the cusp of its first golden age of growth (1896–1914), which came with the settlement of the West. Immigrants to the United States were moving to large industrial cities, while Canada attempted to recruit farmers and farm labour. The Canadian government had few doubts about the potential of this inflow to raise the country’s standard of living, but the value of mass migration was a sub- ject of debate in the United States beginning in the 1890s (Goldin 1994). The flow of unskilled migrants from central, eastern and southern Europe into urban areas was threatening the American unskilled labour force. This was especially so dur- ing periods of slow growth and high unemployment, such as the 1890s.

In Canada, due to railway construction, the period 1896 to 1914 was one of high investment. During that time, the annual rate of immigration was the highest in the country’s history. Although the government continued to advertise for farmers to settle the West, immigrants were heading into every region and sector (see Green and Green 1993). Indeed, recent research suggests that rapid population growth, driven mainly by immigration, played a significant role in raising real per capita income during this period by exploiting opportunities for economies of scale (see Green and Sparks 1999).

So, to return to our “What if…?” question, if Canada had adopted US immi- gration policy in 1900, would the country have attracted as many immigrants (and those of the “right kind” — that is, farmers from preferred countries) as it did? Recall that attracting immigrants to fill the West was a central element in the government’s nation-building strategy. Two factors stand out. First, immigrants to Canada would have been much more ethnically diverse had the government not implemented poli- cies to draw migrants from higher-wage countries. Second, Canada’s level of perma- nent immigration may well have been lower, since new arrivals would have been attracted to the expanding industrial cities to the south. We see some evidence of this churning effect in table 1. One might expect to see such labour turnover dur- ing periods of slow growth and low net emigration (1870-1900). The fact that it occurred during years of high net immigration (1900-13) suggests that the two labour markets were closely integrated at this early stage (see Green, MacKinnon and Minns 2002). Hence, one suspects that if the two countries had possessed a common immigration policy, immigrants would then have been more inclined to see North America as a single labour market. Still, even if this common immigration policy had existed, some migrants would have gone west to take advantage of new opportunities in the region, especially since economic conditions had improved.

So would the settlement of the West have occurred later if Canada had adopted US immigration policy in 1900? And who would the settlers have been? The US would likely have drawn many of the immigrants arriving in North America, and more native-born Canadians might have moved west; more Americans would certainly have moved north. By filling the West on the strength of its own immigration policies, Canada was able to control the pace of settle- ment and thereby maintain sovereignty over this largely unsettled region. This was one of the motivating factors behind the creation of the National Policy. But had the country adopted US immigration policy, would it have become industri- alized as quickly as it did, and what pattern of growth would it have been fol- lowing as the twentieth century got under way? For example, would manufac- turing have become concentrated in central Canada in the opening decades of the century, or would this have occurred later?

The cases for and against harmonization in the period 1870 to 1913 are unclear. Canada was in desperate competition for immigrants during this period. One might speculate that anything that undermined Canadian policies to attract immigration would have decreased the number of immigrants the country received. And recall that beginning in 1891, the US Immigration Act was amended to prohibit advertising for immigrants (Timmer and Williamson 1998), poten- tially reducing the flow of immigrants to Canada.

By the end of the First World War, most of the countries that had experienced large-scale immigration the century before had shifted from laissez-faire immi- gration policies to policies of regulation and restriction. This coincided with the end of the period of frontier settlement, which had been under way since the late nineteenth century in such countries as Australia, Canada and the United States. When the inducement of free land was withdrawn, immigration centred on urban areas. This threatened to lower real wages and, in hard economic times, raise the level of unemployment among native-born workers. In addition to wor- rying about the level and timing of immigration, governments began to be con- cerned about the shift in the source of immigrants — from the traditional regions of northwestern Europe to the nontraditional areas of central, eastern and south- ern Europe. Not surprisingly, the war had left a legacy of xenophobia.

One interesting aspect of the move toward restricting entry was the way in which different countries chose to regulate immigration flow (see Foreman-Peck 1992). In essence, restrictions were stringent where labour interests dominated the political process and less so where landed interests and the owners of capital were in control. Even in Canada and the US, where the basic democratic institu- tions were similar, the policies that emerged after the First World War were quite different. For example, in 1921, the United States imposed the first set of quotas on the number of immigrants admitted annually. It set numerical limits on immi- gration from countries outside the Western Hemisphere. (Canadians — that is, citizens and immigrants who had resided in the country for a specified period of time — were exempt from these new regulations.) The quota was set at 3 percent of a country’s resident population as recorded in the 1910 census. In 1924, the Quota Act was amended to establish a quota of 2 percent of a country’s population based on the 1890 census. The purpose of the quota was to restrict the flow of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, and it succeeded. Between the decade preceding the passage of these acts and the 1920s, immigration from southern and eastern Europe dropped by 79 percent, while immigration from the traditional source countries rose by 9 percent (Gemery 1994, 177). The adoption of the quota acts therefore brought a larger share of immigrants to the US from the high-wage countries. In 1927, the annual total quota was set at 150,000.

In 1923, Canada followed the United States by formally adopting admission restrictions based on country of origin. It divided the world into preferred and non- preferred countries. The former included Britain, the white Commonwealth coun- tries, the United States and the countries of northwestern Europe. Immigrants from Britain were admitted without restriction, with the exception of those deemed likely to become public charges. Immigrants from northwestern Europe — the Scandinavian countries, Holland, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Finland and, after 1926, Germany — were admitted on the same basis. Only British immigrants who intended to farm were eligible for financial assistance. Immigrants from the rest of Europe — the nonpreferred class — were admitted only if they intended to become agricultural workers in the West or had a permit issued by the minister of immigration. These restrictions allowed the government to control the flow of unskilled workers into Canadian cities. Hence, Canada and the US ranked European countries in a similar way for immigration purposes.

But here the similarity ends. Canada did not impose an annual immigra- tion quota. Nor did it impose limits on the number of people entering from any one country. Rather, it adopted the concept of absorptive capacity: it tied the number of immigrants admitted in a given year to the country’s short-run eco- nomic conditions. Henceforth, immigration would follow alternating periods of large inflows targeted at specific economic goals and periods of virtual shut- down in the face of poor domestic labour market conditions. Economic goals, therefore, became central to Canadian immigration policy. Family reunification remained a consideration, but, until recently, it was always subordinate to “gap filling” (see Green and Green 1999). American immigration policy, from the 1920s onwards, focused more on political considerations, especially during the Cold War years, and on kinship rather than economic factors. The United States did not adjust its annual inflow or the occupational composition of that inflow to accommodate short-run economic conditions.

Finally, the stated goal of Canadian immigration policy up to 1930 remained the same — to draw farmers and farm workers who would settle in the West. Immigration therefore continued to be a tool of economic policy in Canada, but, with the passage of the Quota Acts in the 1920s, the US government ended the age of mass migration and signalled that immigration would no longer be a major factor in US economic development. Both countries received few immigrants during the Depression of the 1930s and the war years of the 1940s. What, then, might the economic consequences have been if Canada had adop- ted the closed-door immigration policy of the United States?

The US Quota Acts did not allow for the flexibility of Canada’s absorptive- capacity approach, whereby immigration levels could be matched to short-run economic conditions. An annual quota was set, and no adjustments could be made to accommodate the changing economic situation. But was the Canadian system actually more flexible than the American one during periods of extreme economic downturn, such as the Great Depression?

In 1931, the Canadian government passed an Order-in-Council limiting admittance to those with sufficient capital to start a farm, farm labourers and domestics (Green 1976, 18–19). Under this order, sponsorship rights were limi- ted to immediate family members and only children under the age of 18. Immigration to Canada fell from an annual average of about 123,000 in the 1920s to 16,000 in the 1930s. The US experienced a similar drop with the onset of the Depression. The average annual gross immigration during the 1930s was only 13 percent of the annual average in the 1920s (400,000). It is interesting to note that the drop between the 1920s and the 1930s in the US was identical to that in Canada — 13 percent.

This decrease was not due to a quota change. In fact, there was a decline in the percentage of quota fulfillment. The share of quota allotment fell from nearly 100 percent in the late 1920s to 10 percent by the mid-1920s. The share climbed to only 40 percent of total quota allotment by the outbreak of the war (Gemery 1994, 180). The reasons for this sharp decline were the high and per- sistent level of unemployment; the effect of lower incomes on the ability of resi- dent immigrants to sponsor relatives; and the strict interpretation by overseas immigration officials of a provision in the 1917 US Immigration Act refusing visas to individuals “likely to become public charges” (Gemery 1994). If Canada had adopted US immigration regulations, then, it would have made little difference during periods of extreme economic downturn. However, as we will see in the next section, the difference would have been significant during periods of eco- nomic expansion.

Canada faced a very different set of problems in the quarter-century following the Second World War than it did in the decade leading up to it. The 1930s was a decade of high unemployment and slow growth. The postwar period was one of rapid growth driven initially by high levels of investment and rapidly expanding exports. The country had gone from having an excess of labour to experiencing labour shortages. Furthermore, there was a lack of native-born workers entering the labour force due to the low birth rates of the 1930s. The demand for labour peaked in the 1950s. Slight relief came in the late 1950s and early 1960s, as growth slowed. However, when expansion resumed, the government found itself with a different problem. Skilled workers were now required to fill specific gaps in the occupational structure, but since few changes had been made to Canada’s immigration policy between the early 1900s and the early 1960s, such workers were in short supply.

It is difficult to see how these labour-market demands could have been met had Canada adopted US immigration regulations. Canada not only needed a rapid increase in inflow but also the flexibility to draw immigrants from new sources — the traditional source areas had dried up by the late 1950s. Such flexibility was not possible under US regulations. At the time, a small country like Canada could not have made up for the labour shortages caused by the low birth rates of two decades earlier. Neither, as we will see, did Canada have the educational infra- structure to fill the sudden need for highly trained workers. In addition, the bene- fit of having a highly mobile labour force due to this surge of immigration would have been lost just at a time when the country was shifting from a resource-based economy to one driven by manufacturing and service-sector expansion.

In the 1960s, both Canada and the US abandoned their racially based immigra- tion policies. There was public pressure to eliminate human rights violations and discrimination, and immigration policy based on admission by country of origin was out of step with the new domestic reality. Canada moved to a universal policy of admission in 1962. A prospective immigrant would be admitted on the basis of personal characteristics, not place of birth. In theory, Canada viewed the whole world as a source of immigrants and, supposedly, treated each country equally. But when the United States abandoned its country-specific quota system in 1965, it divided the world into two parts: the Eastern Hemisphere, which was allotted 170,000 visas annually; and the Western Hemisphere, from which 120,000 immigrants could be accepted each year. The US Immigration Act of 1965 made family reunification the core of American immigration policy. This was modified somewhat in the late 1980s to allow independent immigrants with needed skills to be admitted (see Reimers and Troper 1992, 38ff.) — a scheme similar to the one Canada employed.

Here the similarity between the two policy regimes ends. In 1967, Canada adopted a system under which independent and nominated immigrants had to have a certain number of points — awarded on the basis of age, education, train- ing and occupation — to gain entry. The point system is a powerful tool for directing inflow to where it is most needed. Although it has been modified over the intervening period, the system remains in effect today, and it continues to shape Canada’s immigration policy. Thus, as the US moved to reaffirm kinship as the primary focus of its immigration policy, Canada was once again using immi- gration as a tool of economic policy.

With David Green, I examined the effectiveness of the point system. Using time-series analysis, we sought to measure whether the occupational composition of immigrants changed with the introduction of the point system and whether the occupational composition reflected the categories of workers preferred under the new system. The empirical results showed that the occupational composition changed with shifts in points in the years after 1967 (Green and Green 1995). The system works. However, it is mainly larger point shifts that caused changes in the inflow. We also found that this effect can be swamped by changes in the unassessed part of the inflow — that is, as the admission priority moves toward including more distant relatives in the sponsored class, the effectiveness of the point system in matching demand to supply declines.

Although the points awarded to specific occupations changed over time, it is fair to say that this system was designed to increase the share of skilled work- ers entering Canada. Did the fact that the US did not have such a scheme to con- trol for the occupational composition of arrivals — except in a very limited sense — matter to Canada? If we assume that it did not, then it suggests that Canada had an educational infrastructure that could meet the changing demands for skills required for the successful operation of the economy. It is fair to say that Canada did not have such an infrastructure in place by the early 1960s. If, however, the US did have educational facilities in place — which it did — then it would have been disastrous for Canada to adopt the US model. Since a kinship-oriented immigration policy like that of the US would have reduced the human-capital level of immigration (see Green and Green 1995), Canada would have been left with an undertrained and undereducated labour force compared to that of the US. As a result, Canada’s economic growth would have slowed and America’s would have soared, leaving Canada with an even lower standard of living.

The implicit assumption behind such an outcome is that Canada operates under conditions of extreme complementarity — that is, it uses factors in fixed proportion to one another. Hence, shortages or gaps in one factor — say, skilled labour — must be filled if output is to remain unaffected (see Green and Green 1999). We do not know whether the Canadian economy actually operates under such extreme complementarities, but what we need to establish is how success- ful Canadian immigration policy has been at filling gaps in the domestic labour force (Green and Green 1999, 439-40). To explore this question, we will look at three recent research findings, all of which are illustrations of alternative out- comes rather than definitive conclusions.

After the short, sharp, inventory-driven recession of 1921, commodity markets rebounded quickly. Leading this rebound was the worldwide increase in the demand for wheat. Canada, with the West settled and the US and Russia removed from international markets, stood ready to benefit from this surge in demand and the rising prices that accompanied it. Prairie farmers, at the peak of their political influence (Green 1994b), got the federal government to steer immigrants their way, thereby filling their need for more farm labourers. For the first time, the government actually had the bureaucracy to mount such an initia- tive. In the past, it had relied on the railways to deliver labour to a particular part of the country out of their own self-interest. After 1925, for example, it con- tracted with the CPR and the CNR to search for farmers in central and eastern Europe who were willing to work on Prairie farms. Moreover, the government now had a civil service able to follow up on its policies and ensure that immi- grants who had agreed to farm in the West were in fact doing so.

Using a simple model of the determinants of Prairie wages, I found that when I assumed a counterfactual of zero immigration to this region — acting as if the US immigration policy was in effect — real wages rose sharply over the test period (Green 1994a, 166–69). A more open and economically focused immigra- tion policy, therefore, had a significant impact on the evolution of Prairie labour markets relative to what would have happened if the US model had been adopted.

Starting with this finding — that is, that Canadian immigration policy brought Prairie farm wages lower than they would have been had Canada adopted the US immigration approach — Byron Lew and Bruce Cater found that the wages of Prairie farmers would have increased by 20 percent under US immi- gration policy (2001). Lew and Cater then examined the effect higher wages would have had on the rate at which Prairie farmers adopted the tractor. The decision to abandon horses and move to tractors was not an easy one. It depended on a number of factors, such as the prospective price of wheat, farm size and tractor prices. Lew and Cater found that between 1920 and 1925, the tractor-adoption rate on the Prairies was faster than the tractor-adoption rate on the farms of the Northern Plains. Between 1925 and 1930, when immigrants were being steered to the West, the adoption rate declined relative to the rate on farms south of the border. The argument is as follows: Prairie farmers, convinced that the government would deliver a steady stream of immigrant labour, had lit- tle incentive to risk investing in the new tractor technology — it was potentially more profitable to stay with horses. Under such an immigration policy, the farm- ers were confident that they could keep wage costs under control and have suf- ficient workers during the critical harvest season; thus the tractor-adoption rate in their region remained relatively sluggish.

Lew and Cater raise the interesting speculation that the failure to adopt this new technology meant that more labour was retained in Canada’s Prairie region than in comparable regions to the south. So if Canada had used US immi- gration regulations, mechanization would then have proceeded faster in Canada, and when tractor adoption increased sharply in the 1950s, the resulting exodus from the Prairies would have been less dramatic, since more farmers would have been operating tractors earlier. The structural readjustment that had occurred in the US in the interwar period did not occur in Canada until after the Second World War. Such a conclusion does not assume the adoption of an optimal immi- gration policy in the 1920s — that is, the Quota Acts. It simply happened that the adoption of a xenophobic policy delivered these particular results.

Steering large numbers of immigrants toward jobs on western Canadian farms apparently had both short- and long-run effects on the development of this sector. Such a strategy would have been impossible if Canada had adopted the quota system used in the US after 1924. The open question, then, is whether the delay in the adoption of tractor technology was good or bad for Canada’s long- run development. On the assumption that it is always better to adopt best- practice technology as quickly as is economically feasible, the answer is that Canada’s immigration policy may have slowed growth by trapping more workers in the lower-productivity sector (agriculture). The policy also made the Great Depression harder on western Canadians, because more of them had to struggle to make a living in this hard-hit region than would have been the case if immi- grants had not been streamed west during the late 1920s.

There has been a long-standing debate over the efficiency of the Canadian manufacturing industry as compared to that of its US counterpart. When output per worker is used as the measure of efficiency, empirical results suggest that through much of the twentieth century, Canadian industry was 20 to 30 percent less efficient than that of the US (Keay 2000, 1050). The main cause is seen as the high tariff imposed on the import of secondary manufactured goods to Canada. The tariff induced manufacturers to operate factories at lower output levels than was necessary to yield maximum efficiency. Much of the early research into this phenomenon relied on industry-wide data and limited the measure of efficiency to output per worker.

Recent research has revealed a much different relationship between Canadian and American manufacturing efficiency. Researchers have used firm- level data and matched specific industries on each side of the border, and their findings suggest that although labour productivity is lower in Canada than in the US, capital productivity is much higher. And when these two measures of effi- ciency are combined into a single index of productivity, known as total factor productivity (TFP) — the difference, either across space or over time, between the weighted sum of the inputs (capital and labour, where the weights are the fac- tor shares) and real output — there is near parity in efficiency within a number of industries over much of the last century, especially after the late 1920s (Keay 2000, tables 3 and 5; 1061, 1063). Hence, by the early twentieth century, man- ufacturers in Canada had become proficient at adapting best-practice technology to Canadian manufacturing needs. In other words, they were adapting their tech- nology to the domestic economic environment; the relatively lower output per worker suggests that they were using more labour relative to capital per unit of output. This outcome suggests that labour was cheaper in Canada than in the US, so Canadian manufacturers were tending to use more labour per unit of output than their American counterparts.

The lower relative price of labour, one might hypothesize, has its roots in Canada’s more open immigration policy. In Canada, manufacturing developed later than it did in the US — in the 1910s and 1920s as opposed to the last decades of the nineteenth century. The Canadian industrial sector, then, grew to maturity just when the rate of immigration to Canada was at its peak, a time when wage increases were restrained. This occurred again in the 1950s and 1960s, when the next spurt in manufacturing growth coincided with the second great wave of immigration to Canada, much of which flowed to key manufac- turing cities like Hamilton, Windsor and Toronto. Furthermore, with Canadian immigration policy focused on short-run labour-market conditions, manufactu- rers were assured of an adequate supply of labour during high-demand periods. This set Canada on a different technological path in the manufacturing sector, one that required more labour per unit of output.

Again, would Canada have been better off following American immigra- tion policy? There are many ways to produce the same item, but Canadian pro- ducers chose the method that reflected the greater availability of labour — a more intensive, per-unit-of-output use of labour. Although the compensation for this was higher capital productivity, there remains the question of whether Canada would have been more efficient if it had adopted a more capital-intensive strategy for its manufacturing sector. Had it done so, one benefit would have been that the marginal productivity of labour would have been higher, and Canadian wages would have been closer to American wages. Furthermore, it would have induced the manufacturing sector to use more sophisticated means of production — that is, more capital-intensive methods. This clearly is an area where more research is needed.

Immigrants can play an important role in the process of adjusting to struc- tural change that takes the form of a shift in technology or a demand for outputs. Do immigrants act as shock troops, moving into expanding sectors in greater numbers than native-born workers or more rapidly out of contracting sectors? If so, then immigrants help to reduce the costs associated with structural change. With David Green, I examined the possibility that immigrants played such a role in the Canadian economy between 1921 and 1961 (Green and Green 1998).

Test results on the shock-troops model were mixed. Overall, immigrants did not move into expanding sectors or out of contracting sectors faster than native-born workers. However, these aggregate numbers masked some impor- tant differences when subgroups were studied. For example, new arrivals moved disproportionately into expanding sectors relative to either native-born or earlier migrants. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in this regard between source regions. Immigrants from the UK tended to be less flexible than native-born workers, while other European immigrants moved relatively rapid- ly out of contracting sectors and into expanding sectors such as manufacturing, especially in the post-Second World War period. Thus, immigrants increased Canada’s capacity to adjust to structural change. But not all immigrants bring this long-run benefit.

These conclusions were reinforced by David Green in a study based on recent immigrant experience. Green argues that immigrants in the 1980s adapted to changes in the Canadian economy much more rapidly than did nonimmigrants (1999). The overall conclusion, then, is that immigrants admitted under Canadian immigration policy played a positive role in the process of structural change, reducing adjustment costs. Hence, if Canada had adopted the post-1924 US immigration policy, with its fixed annual level of inflow and its humanitarian-versus-economic orientation, the adjustment process to structural change might have been slower and the costs of long-run development higher.

Our investigation of the question “What if Canada had adopted US immigration regulations?” points to the following outcomes:

We should not take away from this counterfactual exercise the idea that Canadian immigration policy was the right policy in every set of conditions. The flooding of the Canadian West with immigrants in the late 1920s created a pool of cheap labour, slowing down the onset of technological change (the substitution of tractors for horses). And when the manufacturing and service sectors began to open up, the exodus of workers from low-productivity farming into these higher- productivity sectors made the move toward new technology in agriculture even slower than it would have been if that move had been undertaken earlier.

Finally, what of the future? Would it matter if Canada adopted US immi- gration regulations today? As we enter the twenty-first century, the US is being forced to respond to the documented and undocumented migration streaming northward out of Mexico and Central America. Canada does not face such a problem. This flood of immigrants into the US has sparked anti-immigration sen- timent in that country. Current Canadian immigration policy is oriented toward attracting young skilled workers and addressing the needs of the world’s refugee population. The debate in the US over how to deal with the rising tide of unskilled workers may not yield a solution that is compatible with Canada’s future social and economic needs. As immigration plays an increasingly impor- tant role in shaping Canada’s future, it is imperative that Canadians maintain sov- ereignty over this vital area of national policy.

Chambers, Edward, and Donald Gordon. 1966. “Primary Products and Economic Growth: An Empirical Measurement.” Journal of Political Economy 74, no. 4: 315-32.

Dobson, Wendy. 2002. “Shaping the Future of the North American Space: A Framework for Action.” C.D. Howe Institute Commentary 162. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Fishlow, Albert. 1965. American Railroads and the Transformation of the Ante-Bellum Economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Fogel, Robert W. 1964. Railroads and American Economic Growth: Essays in Econometric History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Foreman-Peck, James. 1992. “A Political Economy Model of International Migration, 1815-1914.” Manchester School 60, no. 4.

Gemery, Henry. 1994. “Immigrants and Emigrants: International Migration and the United States Labor Market in the Great Depression.” In Migration and the International Labor Market: 1850-1939, edited by Tim Hatton and Jeffrey Williamson. London: Routledge, 175-99.

Goldfarb, Danielle. 2003. “The Road to a Canada-US Customs Union: Step-by- Step or in a Single Bound?” C.D. Howe Institute Commentary 184. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Goldin, Claudia. 1994. “The Political Economy of Immigration Restriction in the United States, 1890 to 1921.” In The Regulated Economy: A Historical Approach to Political Economy, edited by Claudia Goldin and Gary D. Libecap. Chicago: University of Chicago Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research, 223-58.

Green, Alan G. 1976. Immigration and the Postwar Economy. Toronto: Macmillan.

——. 1994a. “International Migration and the Evolution of the Prairie Labour Market.” In Migration and the International Labor Market: 1850-1939, edited by Tim Hatton and Jeffrey Williamson. London: Routledge.

——. 1994b. “The Political Economy of Immigration Selection in Canada, 1896 to 1930.” Unpublished paper.

——. 2000. “Twentieth Century Canadian Economic History.” In The Cambridge Economic History of the United States, Volume III: The Twentieth Century, edited by Stanley L. Engerman and Robert E. Gallman, 191-247. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Green, Alan G., and David A Green. 1993. “Balanced Growth and the Geographic Distribution of European Immigrant Arrivals to Canada, 1900–1912.” Explorations in Economic History 30: 31-59.

——. 1995. “Canadian Immigration Policy: The Effectiveness of the Point System and Other Instruments.” Canadian Journal of Economics 28, 4b: 1006-41.

——. 1998. “Structural Change and the Mobility of Immigrants: Canada, 1921- 1961.” Paper presented at “Regions in Canadian Growth,” March 15-16, Queen’s University, Kingston.

——. 1999. “The Economic Goals of Canada’s Immigration Policy: Past and Present.” Canadian Public Policy 25, no. 4: 425-51.

Green, Alan, Mary MacKinnon, and Chris Minns. 2002. “Dominion or Republic? Migrants to North America from the United Kingdom, 1870-1910.” Economic History Review 55: 666-96.

Green, Alan G., and G.R. Sparks. 1999. “Population Growth and the Dynamics of Canadian Development: A Multivariate Time Series Approach.” Explorations in Economic History 36: 56-71.

Green, David. 1999. “Immigrant Occupational Attainment: Assimilation and Adjustment over Time.” Journal of Labor Economics 17, no. 1: 49-79.

Hatton, Tim, and Jeffrey Williamson. 1994. “International Migration 1850-1939: A Survey.” In Migration and the International Labor Market: 1850-1939, edited by Tim Hatton and Jeffrey Williamson. London: Routledge.

Hatton, Tim, and Jeffrey Williamson, eds. 1994. Migration and the International Labor Market: 1850-1939. London: Routledge.

Keay Ian. 2000. “Canadian Manufacturers’ Relative Productivity Performance, 1907- 1990.” Canadian Journal of Economics 33, no. 4: 1049-68.

Lew, Byron, and Bruce Cater. 2001. “North American Immigration Policy of the 1920s and the Diffusion of the Tractor.” Unpublished paper.

O’Brien, Patrick. 1977. The New Economic History of the Railways. London: St. Martin’s Press.

Ramirez, Bruno, and Yves Otis. 2001. Crossing the 49th Parallel: Migration from Canada to the United States, 1900-1930. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Reimers, David M., and Harold Troper. 1992. “Canadian and American Immigration Policy since 1945.” In Immigration, Language and Ethnicity: Canada and the United States, edited by Barry R. Chiswick, Washington, DC: AEI Press.

Timmer, Ashley S., and Jeffrey G. Williamson. 1998. “Immigration Policy Prior to the 1930s: Labor Markets, Policy Interactions, and Globalization Backlash.” Population and Development Review 24, no. 4: 739-71.

Alan G. Green is an emeritus professor at Queen’s University and teaches in the Department of Economics. Mr. Green’s areas of research are the evolution of labour markets and regional income inequality. His work on regional income examined long-run trends in regional income inequality. His research on labour markets has focused on the economics of immigration, with a particular emphasis on Canadian immigration policy. His first book was published in 1973, and recent published work has examined such themes as the geographic distribution of immigrants to Canada before the First World War; the impact of the points system on the composition of immigrants to Canada; and most recently, the evolution of Canadian immigration policy from its roots in the late nineteenth century to the present.