Au cours des dernières décennies, la garde non parentale a suscité un intérêt croissant au Canada et ce pour au moins deux raisons : l’augmentation importante du taux de participation des mères au marché du travail et une meilleure connaissance des effets béné- fiques des services de garde éducatifs de qualité sur le développement des jeunes enfants.

Mais en dépit de cet intérêt, il est étonnamment difficile de trouver des informations précises et actualisées sur la question. Il n’existe par exemple aucune enquête statistique visant à recueillir des données sur l’utilisation, le prix et les dépenses, le coût ainsi que la qualité des services de garde.

La présente étude tente de combler cette lacune en puisant à plusieurs sources de données comme l’Enquête longitudinale nationale sur les enfants et les jeunes (ELNEJ), l’Enquête nationale sur la garde d’enfants (ENGE), l’Enquête sur les dépenses des ménages (EDM) et quelques enquêtes québécoises et canadiennes sur la qua- lité des services. Elle apporte ainsi un éclairage nouveau sur la garde non-parentale au Canada, en termes d’utilisa- tion, de dépenses et de qualité des services utilisées.

Après avoir présenté les façons de penser les plus répandues en matière de garde des enfants et décrit le contexte politique dans lequel se tient le débat actuel autour de cette question, les auteurs examinent en détail comment les familles canadiennes gardent ou font garder leurs enfants, en soulevant les questions suivantes : Combien de familles utilisent des services de garde non parentale ? Comment ces habitudes ont-elles évolué depuis 1995 ? Les familles dont la mère ne travaille ou n’étudie pas ont-elles recours aux services de garde non parentale ? Qui au juste utilise quels types de services ?

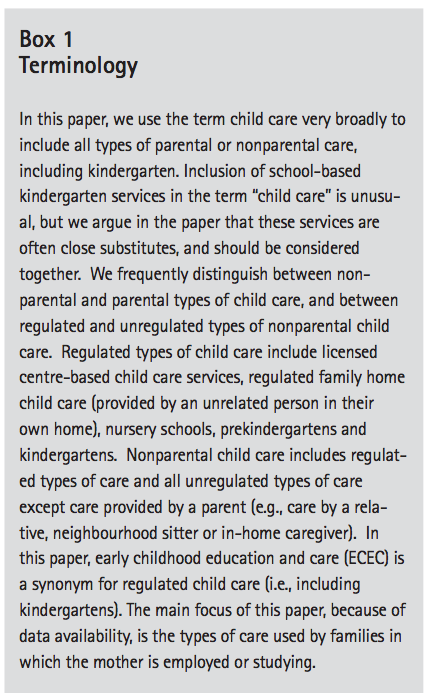

Les auteurs examinent toutes les catégories de familles, mais les données disponibles les ont amenés à privilégier celles dont la mère travaille ou étudie. Par ailleurs, ils étu- dient la question en adoptant une définition étendue des modes de garde, incluant la garde parentale, la garde non parentale réglementée ou non, ainsi que la maternelle.

Ils constatent que près de 80 p. 100 des enfants d’âge préscolaire dont la mère travaille ou étudie sont régulière- ment en garde non parentale. Et la moitié le sont dans des milieux réglementés, une proportion qui atteint près des deux tiers si l’on inclut la maternelle. Par ailleurs, un nombre appréciable d’enfants dont la mère est au foyer fréquenteraient aussi une garderie, une prématernelle, une maternelle ou un autre type de garde réglementé.

En ce qui concerne les dépenses, les auteurs tentent de savoir combien les familles canadiennes dépensent en frais de garde. Pourquoi ces frais sont si élevés pour cer- taines familles et si faibles pour d’autres ? Et d’expliquer l’existence de services de garde à coût nul.

Ils constatent que les frais de garde annuels des familles canadiennes ayant des enfants d’âge préscolaire (à l’exception du Québec) s’élèvent en moyenne à

4 500 dollars pour toutes les familles dont la mère tra- vaille et à 6 900 dollars pour celles dont la mère travaille toute l’année à temps plein. Soit, généralement, près de 20 p. 100 du revenu de la mère. Et pour la plupart des familles, constatent-ils, les dépenses en frais de garde sont associées au niveau de revenu de travail de la mère.

Du point de vue des politiques publiques, ces observations suggèrent que les frais de garde sont un obstacle à la partici- pation au marché du travail pour de nombreuses mères. Dans certains cas, cela leur imposera de modifier leur situation d’emploi ou le type de garde non parentale qu’elles utilisent afin de réduire le fardeau financier de services de garde.

Étant donné le recours très répandu à la garde non parentale, ces conclusions soulèvent aussi la question de leur qualité. En troisième partie, les auteurs examinent donc les données disponibles et concluent à une qualité trop sou- vent insuffisante. Même si la grande majorité des milieux réglementés offrent un environnement sain et sécuritaire aux enfants, beaucoup ne développent pas pleinement les aptitudes cognitives, linguistiques, comportementales, sociales et motrices des enfants. L’information dont on dis- pose en ce qui concerne les milieux non réglementés semble dénoter une qualité plus faible encore.

Puisque les mères sur le marché du travail sont là pour y rester et que la grande majorité de leurs enfants fréquentent des services de garde non parentale, les auteurs font valoir qu’il est temps de changer notre façon de voir la situation et de considérer la garde parentale et la garde non parentale comme des approches complémentaires et non comme des substituts. Ils préconisent donc une stratégie qui rendrait plus abor- dables pour toutes les familles des services de garde édu- catifs de qualité. Ils évaluent à cette fin les avantages et les limites des diverses formes d’aide publique : 1) les crédits d’impôt ou les transferts en espèces aux parents ; 2) les coupons liés à l’utilisation de services de garde non parentale ; 3) les subventions ciblées pour les familles à faible revenu ; 4) le financement direct des fournisseurs de services de garde réglementés. C’est avec ces deux dernières formes d’aide que l’incidence serait la plus positive, estiment-ils, surtout le financement direct pour améliorer l’abordabilité et la qualité.

In the last 25 years in Canada, there has been an explosion1 of policy interest in nonparental child2 care. There are many reasons for this intense public interest. From the recommendations of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, through Judge Rosalie Abella’s Royal Commission on Equality in Employment, many Canadians have expressed a need for child care policies that promote gender equity in workforce access. The rapid increase in the workforce participation of mothers over the last 40 years and more has produced high levels of demand for all types of child care and has led to persistent shortages of licensed child care services.

Beyond workforce and gender issues, there has been increasing recognition that good-quality early childhood education and care (ECEC) services can have beneficial effects on child development. This opinion has been buttressed by much-discussed longitudinal research findings on the effects of early education on children, by emerging research on the influence of environments on brain development in young children, and by economic findings that investment in the early years can pay larger lifetime dividends than many trainingor education-related alternatives.

Despite all of this public interest, the Canadian-generated knowledge base on child care has been modest. Surprisingly, for instance, Canada has no statistical surveys dedicated to collecting information on the use patterns, prices and expenditures, costs, and quality of child care. Our information on child care comes from surveys designed for other purposes but containing a few questions on child care, or from one-off surveys by academics or advocacy organizations, or from administrative data collected by municipal, provincial or territorial governments.

The team of academics who worked on this paper has unearthed new evidence from these surveys: about what types of family uses what types of child care, about how much Canadian families spend on child care, and about the quality of the child care they use.

In the body of the paper, we examine evidence from a number of sources: several cycles of the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY), a project of Statistics Canada and Human Resources and Skills Development Canada; Statistics Canada’s comprehensive (but never repeated) Canadian National Child Care Survey (CNCCS) of 1988; Statistics Canada’s annual Survey of Household Spending (SHS); the Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Quebec (begun in 1998 and known by its French acronym, ÉLDEQ, for Étude longitudinale du développement des enfants du Québec); the Quebec Survey on the Quality of Educational Daycare (conducted in 2003 and known as Grandir en Qualité); and a 1998 survey of child care facilities and quality in six provinces and one territory, known as You Bet I Care!

We will show that the use of nonparental care by families with preschool children is now commonplace, rather than unusual. A large majority of Canadian children receive nonparental care regularly, just as a large majority of Canadian mothers of young children are employed either full-time or part-time over the course of the year. Our research finds that the number of children using nonparental child care is much greater than estimated in the recent literature. Further, close to half of all preschool children of employed mothers in Canada primarily attend ECEC services (i.e., regulated types of care).

Our results suggest that families cannot afford the high costs of good-quality nonparental child care. Average annual child care spending by employed families is about $4,500, which is a burden for these families but still not enough to cover good-quality regulated services unless the cost is subsidized. Some families are able to provide all their own child care (by off-shifting between the two parents or by having the mother work at home). However, for most families this is too costly, in terms of lost income, to be a viable option. The mother’s earning power appears to be a major constraint on the amount that families are willing to spend on child care. Those families who purchase child care currently spend, on average, over 20 percent of the mother’s earnings on these services. Since the purchase of child care makes these earnings possible, apparently the mother’s earnings potential limits the amount that families are willing to spend.

The most important finding, given the widespread use of nonparental care, is that the quality of child care in Canada is too often inadequate to support child development. Among the various types of nonparental care, nonprofit centre-based regulated care currently provides the best experiences for children,3 followed by regulated family home child care, for-profit centrebased regulated care and, lastly, unregulated care.

In the remainder of this introduction, we outline different views in the body politic on appropriate early childhood policy, the historical policy framework for child care in Canada and a review of recent policy developments. In the body of the paper, we review evidence and analyze child care use patterns, spending patterns and quality levels in Canada. In a concluding section, we draw together the main patterns of this evidence and formulate some recommendations for future child care policy in Canada.

A large majority of parents with young children are now regularly employed in the paid labour force. As this is a dramatic change from earlier generations of parents, the established ways of caring for preschool children have had to change as well. Many Canadians believe that governments need to step up their financial and program support for families raising children in this new environment.

The public policy issues surrounding child care, early education and preschool are controversial; Canadians hold passionate, perhaps irreconcilably divergent, positions on what should be done. Some believe, in the context of already widespread nonparental child care, that good-quality child care, including preschools and kindergartens, is much more beneficial for child development than informal arrangements and that this level of quality should be available to all children through universal public funding. Further, they believe that lowering the net cost of ECEC can play a role in removing the barriers to women’s employment. According to this view, the first priority in Canada, outside of Quebec, is to provide affordable services for children two to five years of age (users could pay some fee for services, perhaps for additional hours beyond a core that is free of charge), together with slightly longer and more flexible maternity/parental leave and benefits covering a larger portion of the employed population. In Quebec the first priorities would be to improve the quality of existing ECEC services and reduce waiting lists.

Other people believe that regulated child care has positive effects on children from low-income families (whose home life may not be developmentally stimulating) but is neither better nor worse than the alternative arrangements made by parents of more advantaged children. They favour generous subsidies for the use of ECEC targeted to low-income families, to encourage parental employment as well as to provide care that is developmentally oriented. Families with middle incomes would receive a partial ECEC subsidy, based on income; many families would be ineligible for ECEC subsidies but would make their own arrangements.

Some others believe that care by parents is inevitably better than any form of nonparental care, and furthermore that parents prefer parent-provided care, at least for preschoolers, and that, for families with young children, government should make it financially possible for one parent to stay at home. This view leads to a policy recommendation for a substantial child care/home care allowance for stay-athome parents, or a generous family allowance (like an expanded Universal Child Care Benefit [UCCB]) with higher net benefits for single-earner families than for other family types, and/or maternity/parental leave and benefit arrangements that provide income support for the first three years of a child’s life.

Others believe that different types of child care (including regulated and unregulated care and exclusively parental care) are appropriate for different children, and that parents make the best judges regarding the quality of the child care offered and the particular needs of their children. According to this view, the fundamental characteristic of public policy should be financial support that in no way discriminates among parental choices of child care type and employment status. Support could take the form of an even-handed family allowance, or a more generous Canada Child Tax Benefit, or (in order to ensure that public funds are actually spent on child care) a voucher scheme with vouchers redeemable for approved types of care, including care by a parent or relative.

Finally, there are those who believe that children are a consumption or lifestyle choice, one that should not be favoured over other consumption choices. In this view, public policy should be neutral with respect to whether families do or do not have children. In this paper we will not be discussing this final policy alternative.

The history of government child care policy at federal, provincial and municipal levels reflects all of these policy positions. From the 1960s to the 1990s, regulated child care was funded on a 50/50 cost-shared basis between the federal government and the provinces/territories (with municipalities responsible for 20 percent of the total in Ontario), but only for low-income families or children otherwise considered to be disadvantaged or at risk. The income limits and other subsidy eligibility rules (generally, parents had to be employed or in job training, as well as being poor) were established at the provincial/territorial level (within federal guidelines) and varied across the country. Although the Canada Assistance Plan, which cost-shared this funding, was eliminated in 1996, provincial/territorial child care subsidies targeted at low-income families still exist in all jurisdictions except Quebec.4

The second pillar of child care policy has been the Child Care Expense Deduction (CCED; since 1972). The CCED allows the lowest income earner in a family to deduct the cost of nearly any form of nonparental care (up to a limit of $7,000 per child under seven years of age) from her taxable income. The logic behind the CCED is not well appreciated (and is frequently misinterpreted).5 In deciding whether to be employed, the second earner in a family with young children will compare the value of her time spent at home to the value of her time spent in the workforce. If one of these is taxed while the other is not, the taxation will distort the employment decision inefficiently, in a way that discriminates against employment. Even though time at home does produce services of value to the family, the value of this “home income” is impossible to calculate and is not subject to taxation. To reduce the resulting tax discrimination against employed mothers, the CCED shelters child care costs from taxation. These costs are already a barrier to mothers’ workforce participation but would be more so if they had to come out of after-tax income (i.e., the mother would be paying tax on the income earned to pay for child care, and then paying the child care costs).

The third pillar of child care policy has been maternity and parental leave and benefits paid through the federal Employment Insurance Fund, which is a contributory fund financed by employers and employees. In effect, eligible parents are paid a proportion of their normal employed income to permit them to stay at home with a newborn child for up to one year. The first 15 weeks of benefits (17 weeks of leave) are reserved for the mother of the newborn, but the ensuing 35 weeks can be split between the two parents as desired. Only mothers who have been employed (not self-employed) for at least 600 hours during the preceding year are eligible, and the recompense for most is 55 percent of earned income up to $435 per week (or about $22,000 for 50 weeks). Quebec has recently (2005) negotiated with the federal government to provide more generous benefits for Quebec parents, including some flexibility in the amount and timing of benefits as well as coverage for self-employed mothers (see Phipps 2006 for details). Year-long maternity/parental leave allows parents to spend more time away from work caring for their very young child, but, by providing a job guarantee, simultaneously encourages new parents to maintain their workforce attachment.6

The fourth pillar of child care policy is the provision of universal, free kindergarten for age-eligible children. Kindergarten is typically provided through the public school system, for half days in some provinces/territories and full school days in others. In most provinces/territories, kindergarten is voluntary (but almost universal in take-up) and is provided for children who are five years of age (or nearly five in September, when school starts). In Ontario, half-day junior kindergarten is universally available for children four years of age (or nearly four).7

There is more to child care policy than these four pillars, of course. Each province and territory has a framework of regulations for child care (staff-child ratios by child’s age, group sizes, teacher qualifications, health and safety) and a staff that licenses centres and monitors compliance with regulations. In addition, Quebec (as discussed below), Manitoba and some other provinces provide direct operating funding for centres and family homes, to lower the cost borne by parents and to enhance the quality of services offered.

Four factors have combined to put pressure on the existing “four pillars” framework for early childhood policy. First, there has been a widespread recognition that the increasing employment of mothers has dramatically changed family life, that this trend is continuing and that the great majority of preschool children are affected. Second, there is recognition of the importance to the economy, and to gender equity, of women’s continuing attachment to the workforce. Third, there has been considerable research on child development and the effects on children of positive and negative parental and nonparental preschool experiences (and the potential negative effects of inaction or lack of policy and services). Finally, there has been concern about increased inequality in Canadian society and, in particular, the burden of child poverty on present and future generations; increased subsidization of ECEC could affect both the current incomes of parents and the future abilities of children.

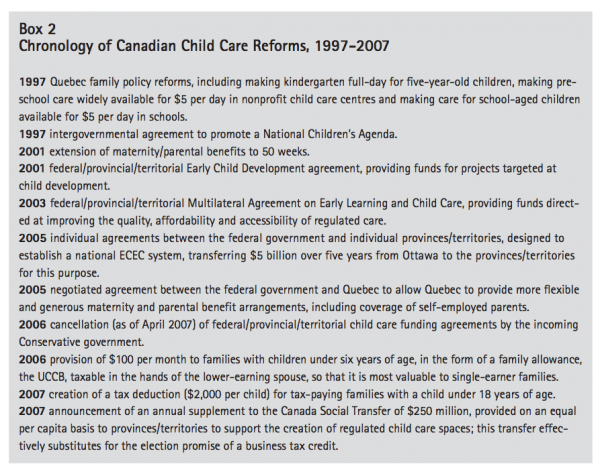

As a result, the last decade has seen a flood of child care initiatives at the federal and provincial levels. Box 2 presents some of these initiatives in chronological order, with some commentary on the objectives of each.

The conventional wisdom is that a bare majority of preschool children in Canada receive nonparental care. This notion has its origins in two recent reports (Bushnik 2006; Statistics Canada 2005) stating that in 2002-03 only 54 percent of all children 6 to 71 months of age received any form of nonparental care. This has become accepted fact through repetition (see Baker, Gruber, and Milligan 2005; LeRoy 2006; Richards and Brzozowski 2006). Further, according to these same sources, as recently as 1994-95 only 42 percent of Canadian preschool children received nonparental care.

There is reason to believe that these data present a misleading picture of the extent of nonparental child care in Canada. Indeed, given the phrasing of its questions related to child care use, the survey from which the data are drawn can generate valid estimates of use only for families with both parents employed or studying8 and not for all Canadian families.

The source of these data is the NLSCY,9 which is currently the only source of data on child care use patterns across Canada. The NLSCY has been collecting data every two years, starting in 1994-95, on a large sample of Canadian children. Initially, the group of children ranged in age from 0 to 11 years; as the group has aged, additional younger children have been recruited to make the data more cross-sectionally representative of Canada’s population of young children.10 The survey assesses different aspects of children’s development, so that child care use is only one of its many subjects of investigation. Its questions about child care use are directed only at those families in which parents are employed or studying. For these reasons, the NLSCY provides an incomplete picture of child care use patterns. Still, the data are the best currently available.

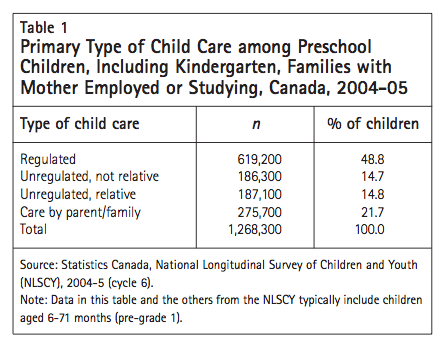

Tables 1 and 2 list the primary types of care attended by children under six years of age11 in families with an employed or studying mother. The data are from Cycle 6 (2004-05). The term “primary” refers to the type of nonparental child care used for the largest number of hours in the reference week. In the case of parental care, however, a child is classified in this category only if parental care is the sole type of care used (in other words, if the child does not attend any form of nonparental care).12

In these tables, we consider four types of child care. Reducing the number of types of care in this way allows us to see broad policy-relevant patterns in the data. The four types are: regulated child care, unregulated care by a nonrelative, unregulated care by a relative, and care by a parent or immediate family member.13

Many parents use kindergarten services as a form of child care for children three, four or five years of age (depending on eligibility rules in their province), rather than or in addition to nursery school, pre-kindergarten, preschool or centre-based child care (all of which might be considered reasonably close substitutes). In table 1, we include kindergarten as a form of regulated child care. If more hours are spent in kindergarten14 than in any other form of care, then regulated child care becomes the primary type of care used.

Table 1 shows that nearly half of all preschool children of employed or studying mothers attend regulated care as their primary type of child care.15 Just over 20 percent do not attend any type of nonparental care (i.e., they are cared for exclusively by a parent or family member). In 15 percent of cases the primary type of care is care by a nonrelative and in another 15 percent it is care by a relative.

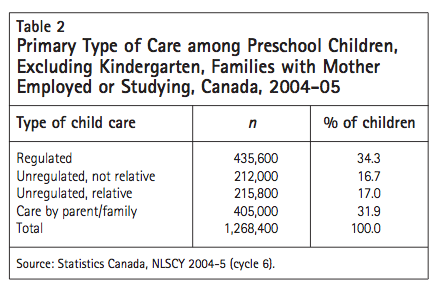

One might wonder how this picture of child care use would change if the role of kindergarten in providing care were ignored. Table 2 omits kindergarten as a form of regulated care (leaving child care centres, regulated family-home child care, nursery schools and preschools to make up the regulated care category). This increases the amount of exclusively parent/family care (i.e., for some families kindergarten is the only type of nonparental care used). If we employ these definitions, over one third of all preschool children with employed/studying mothers attend regulated care services, while just over 30 percent are cared for exclusively by one of their parents and 17 percent, in each case, are cared for by a nonrelative and by a relative.

The answer to our question about how many children are in particular types of nonparental care depends, therefore, on whether kindergarten is considered a form of child care. Based on parent behaviour, we believe kindergarten should be included.

We can look at parent behaviour when Quebec made kindergarten full-day rather than part-day in 1997, when New Brunswick initiated full-day kindergarten in the early 1990s and when Ontario opened junior kindergarten services across the province. In each of these cases, kindergarten use increased and other nonparental care (especially regulated child care) decreased. When parents see these services as close substitutes, both for child development and as a form of substitute care while they work or study, it is appropriate for researchers and policy-makers to include kindergarten as a type of child care in their analyses of use patterns and family decision-making.

Moreover, kindergarten is included as a form of ECEC in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development reports for nearly all countries (see OECD 2001, 2007) and is included in regular reports on “Early Childhood Education and Care” by the Childcare Resource and Research Unit of the University of Toronto (Friendly and Beach 2005a; Friendly et al. 2007). In Canada, most kindergartens are located in schools but attendance is voluntary; except in New Brunswick, they are not part of the compulsory school system. Kindergartens generally offer a play-based early learning experience that is similar to that provided in regulated child care, with less advantageous staff-child ratios but with more years of teacher training (although generally with no requirement for special training in early childhood development).

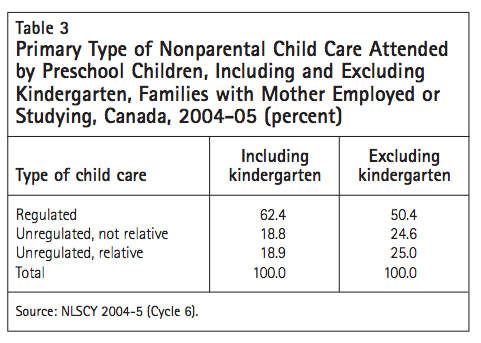

If we include kindergarten as a form of nonparental child care, then 8 out of every 10 children in families with an employed or studying mother received nonparental care on a regular basis. If kindergarten is not included, the figure is 7 out of 10. In other words, a large majority of preschool children whose mothers are employed or studying regularly receive some form of nonparental care, and, including kindergarten, approximately half attend regulated services. But tables 1 and 2 include parental care. If we focus only on nonparental care, as shown in table 3, we find (including kindergarten) over 62 percent use regulated ECEC as their primary form of care, 19 percent use unregulated care by a nonrelative and the remaining 19 percent use care by a relative. If kindergarten is excluded, then the figures are 50 percent, 25 percent and 25 percent, respectively.

The main alternative source of information on ECEC in Canada is regular publications of the Childcare Resource and Research Unit (CRRU) in Toronto (Friendly and Beach 2005a; Friendly et al. 2007), which use data provided by provincial and territorial officials. For 2006, these publications estimate that there are roughly 390,000 centre-based, regulated child care spaces for preschool children in Canada, and about another 140,000 spaces in regulated family child care; it is unknown how many of these family spaces are occupied by children under six years of age. This compares to our estimate, in table 2, of 435,600 preschool children in regulated care (not including kindergarten).

The estimates are different, for several reasons. First, the CRRU numbers measure capacity, not enrolment. Second, they include spaces occupied by children from all families rather than only those with an employed or studying mother. Third, they refer to 2006 rather than 2004-05. However, these estimates appear to be broadly consistent with our own, based on the NLSCY survey.

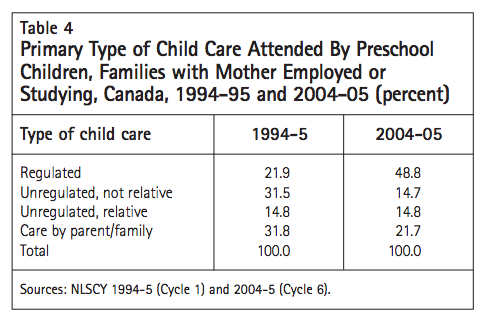

We can compare the numbers in table 1 (from 200405) to those available from Cycle 1 of the NLSCY in 1994-95. Table 4 shows the percentage use in both years for all types of child care in families with an employed or studying mother. Use of regulated forms of child care has grown substantially since 1994-95 (from less than a quarter to nearly half of all children), while care by a relative is stable in percentage terms. The use of unregulated care by a nonrelative has been cut by more than half, and the exclusive use of parent/family care has dropped by more than a third.

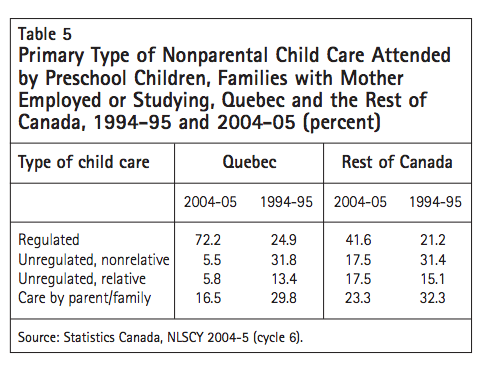

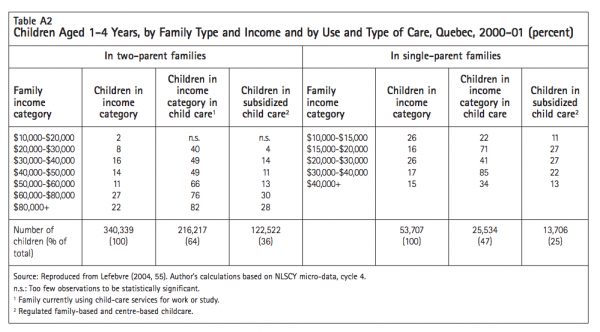

The role of Quebec’s child care and kindergarten reforms in these changes over the last 10 years is unmistakable, and quantitatively large. Table 5 shows the 2004-05 child care use patterns for Quebec and the rest of Canada separately (with the corresponding 1994-95 figures in parentheses). In Quebec the use of regulated care (including kindergarten) by families with an employed or studying mother is now overwhelming, with over 70 percent of children attending this type of services, whereas in the rest of Canada it is merely predominant, at over 40 percent. Still, looking at the use patterns in 1994-95 (in parentheses), one can see that there has been substantial growth in the use of regulated care in both Quebec and the rest of Canada and substantial decline in both nonrelative care and exclusively parent/family care in Quebec and in the rest of Canada. Care by a relative is up slightly in percentage terms in the rest of Canada over the decade but has fallen dramatically in Quebec.

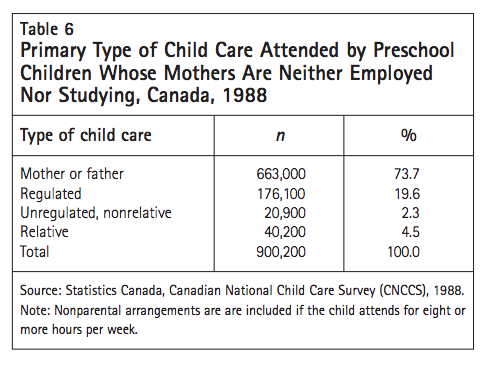

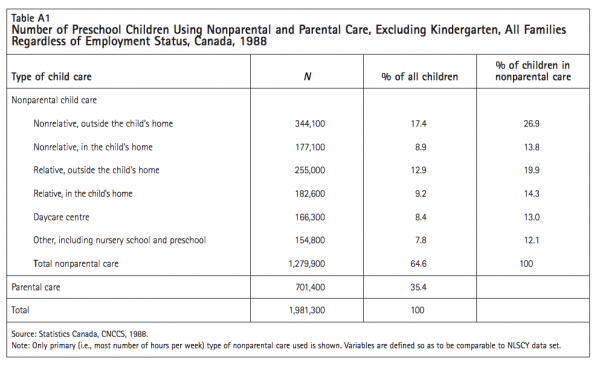

There are no valid current data on use of nonparental child care by families with children in which the mother is not employed or studying, although some of these families do use care outside the family (for stimulation of early learning experiences, for peer play or for a parental break). Therefore, table 6, from the 1988 CNCCS, is valuable in that it shines a light on this neglected group.

Given the publicity for positive research findings about the beneficial effects of preschool child care experiences, it is probable that the use of different forms of nonparental care in families in which the mother is not employed or studying is greater now than it was nearly 20 years ago when these data were collected. At that time, there was no substantial use of nonparental care in over 70 percent of these families (we define substantial use as at least eight hours per week). However, nearly 20 percent of preschool children in these families did attend regulated care (often nursery school or kindergarten) on a regular basis and nearly 7 percent received substantial amounts of other types of nonparental care.

It has been frequently claimed (e.g., Kozhaya 2006; LeRoy 2006) that Canadian parents do not favour regulated child care; it is suggested that this type of child care is “institutional” and that parents prefer care that is provided by parents or relatives. This claim seems to be at odds with the rapid growth in use of regulated care in both Quebec and the rest of Canada over the last decade, so the issue of “parent preferences” warrants some exploration.

The origin of the view that parents do not favour regulated care appears to be a study conducted in9 2004 for the Vanier Institute of the Family by Professor Reginald Bibby of the University of Lethbridge. The study report was subtitled “A Survey of Canadian Hopes and Dreams,” reflecting the design of this survey of more than 2,000 adults. The survey collected data on the aspirations of Canadian families in an ideal world.

Survey respondents were asked to imagine that they had preschool children in a two-parent family with both parents working. They were asked to list their top five choices among different types of care they could use. Bibby summarizes the results this way: “[I]n an ideal world, the number one choice is one’s partner, followed by one’s parent, then another relative. Rounding out the top five? Home-based child care, followed by a child care centre” (Bibby 2004, 55).

To put these responses in context, we should note that, despite the phrasing of the question, it is not “employed” Canadian parents of preschool children who are responding to the survey, but a group of adult Canadians of all ages, the large majority of whom do not have preschool children currently and many of whom may not be employed currently. The respondents are answering a hypothetical question about what preferences (i.e., unrelated to financial or employment constraints) they would have if they were living in a family situation that the majority of them are not currently living in.16

A study conducted by the Institut de la Statistique du Québec (2006) provides an alternative guide to the child care preferences of parents. This study surveyed families in Quebec with a child under five years of age in September 2004. The families were asked which type of child care they would choose, based on the age of their child, if they needed to use care on a regular basis. They were given a number of alternatives: care provided in their own home, unregulated care in the caregiver’s home, reduced-contribution care in a family home (coordinated by a CPE — Centre de la Petite Enfance, or nonprofit child care centre), reduced-contribution care in a CPE, other type of care. For a child under one year, the majority of families chose care provided in their own home. From one year through four years, approximately 65 percent to 80 percent chose care in a CPE or coordinated by a CPE in a family home. The survey did not include care by a parent or relative.

In the final analysis, surveys of preferences do not necessarily provide trustworthy evidence about parents’ underlying tastes; most respondents are dramatically influenced by the wording of the questions and by the conditions (child care price and quality; family income) that they face while answering them. In the end, the best guide to parent preferences, under given conditions, will be the type of care that parents actually decide to use. The latest available data suggest an increased willingness, in both Quebec and the rest of Canada, to use regulated care.

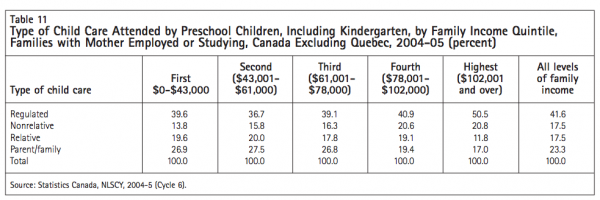

Different families, in different family situations, use different types of care for their preschool children. Using the data from Cycle 6 of the NLSCY (2004-05), we can examine factors affecting the use of various types of care by families with employed or studying mothers for preschool children (aged 6-71 months). Because of the dominance of regulated child care in Quebec, we confine this analysis to the rest of Canada.

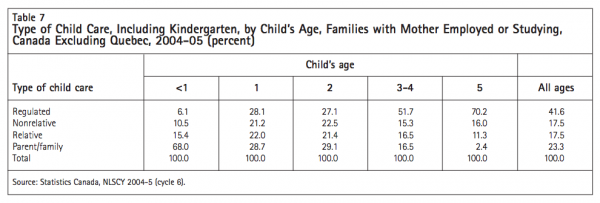

The decisions of parents about which of the four main types of child care to use are influenced by a range of factors.17 As table 7 suggests, one key factor is the age of the child.

The majority (68 percent) of children under one year old (i.e., age <1) in families in which the mother is employed or studying are cared for by parents or other members of the immediate family. This may be surprising, but remember that mothers who are on maternity or parental leave are employed. A large proportion of these children in exclusively parent/ family care are cared for by a parent on paid leave from work.

At one and two years of age, approximately equal numbers of children are in regulated care and cared for exclusively by parents/family. At ages three, four and five, roughly half and then 70 percent attend regulated care services. The use of exclusively parent/family care drops correspondingly, with about 17 percent of children at ages three and four and less than 3 percent at age five not using some form of nonparental care.

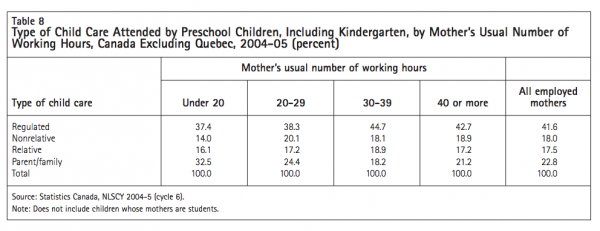

A second factor is the number of hours per week that the mother typically works in her paid job (see table 8; note that the table excludes children of student mothers). Families in which the mother works less than 20 hours per week are much more likely to use exclusively parent/family care than those in which the mother works more than 20 hours (one out of three vs. one out of five). Of course, we cannot necessarily regard number of hours as the cause and parental care as the effect; a mother may decide to work fewer hours precisely because she prefers to use exclusively parental care or because the cost of purchasing nonparental child care is too high.

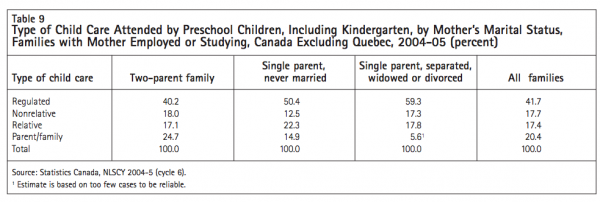

A third factor is marital status, whose effect is shown in table 9. Single-parent families, regardless of whether the mother has never married or is separated, widowed or divorced, are more likely than two-parent families to use regulated child care. This may reflect the lower incomes of single parents and the greater availability of low-income child care subsidies to single-parent families, but it also reflects the absence of a second parent who could provide parent/family care. Marital status has little effect on the combined total use of unregulated nonrelative and unregulated relative care, although never-married single parents are more likely to use care by a relative. Single-parent families are much less likely than two-parent families to use exclusively parent/family care. In families with a never-married single parent, about 15 percent of mothers care for their own children while employed, whereas in separated, widowed or divorced families, parent/family care is in the low single digits; these figures compare to nearly one quarter of the children in two-parent (married or common-law) families.

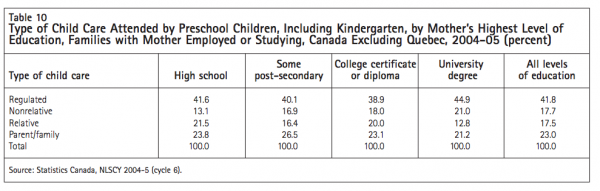

As table 10 shows, the mother’s education is only moderately related to the type of care chosen. At every level of education, regulated child care is the choice of a plurality. Use of exclusively parent/family care diminishes moderately at higher education levels. Use of care by a relative is somewhat lower for university-educated mothers; use of unregulated care by a nonrelative rises with level of education.

Table 11 shows the relation between use of different types of child care and quintile groupings of annual family income in 2004-05. Income is related to many other family characteristics. Families in which the mother works for pay for fewer hours per week are likely to have lower incomes. Single-parent families are likely to have lower incomes. Families in which the mother has higher education are likely to earn more. Family income reflects these differences between families as well as having its own independent effect.

Use of regulated child care is approximately 40 percent in the four lower quintiles of family income, rising to 50 percent in the highest quintile. Although most regulated child care is expensive, kindergarten is free for five-year-olds (and four-year-olds in Ontario). Low-income (particularly single-parent) families in Canada may be eligible for child care subsidies for children of any age (Friendly et al. 2007). As a result, those in the lowest income quintile are not less likely to use regulated care than those with middle incomes.

Unregulated care by a nonrelative is not subsidized and may be expensive; the use of this type of care rises with income. Use of unregulated care by a relative is not greatly affected by family income but falls off at the highest income level. Parent/family care is less common at the two highest income levels.

Which family types use care by a parent or sibling for their preschool children when the mother is employed or studying? This is an intriguing question, linked to the important question of how it is that many families do not purchase child care even though the mother is employed (see below, in the section on spending patterns and affordability).

It is useful to start by listing the different ways in which a family can end up using exclusively parent/ family care for a preschool child even though the mother is employed or studying.

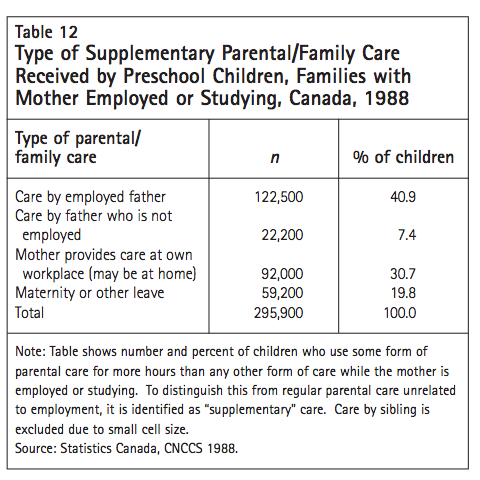

The NLSCY does not permit us to calculate how many children are cared for in each of these situations (it asks only about forms of nonparental child care). However, the 1988 CNCCS does permit us to do so.

Table 12 provides a breakdown of the different types of parent/family care provided to preschoolers whose mothers were employed or studying in 1988. In this breakdown, kindergarten is considered a form of nonparental care, so possibility number 5 in the list above does not apply. Further, the amount of care provided by a sibling is too small to report, so we do not show a breakdown for possibility number 4.

As table 12 indicates, the largest category of parent/family care is care provided by the father. In about 40 percent of cases, the father off-shifts with the mother to care for the child. In another 7 percent of cases, the father provides care while the mother acts as the family breadwinner. In about 30 percent of cases, the mother provides the child care by herself while at work (most of these mothers are selfemployed and work in their own homes). About 20 percent of parent/family care is provided by mothers who are on maternity or other leave18 from a job (they are therefore classified as employed but, of course, are able to provide care for their own child).

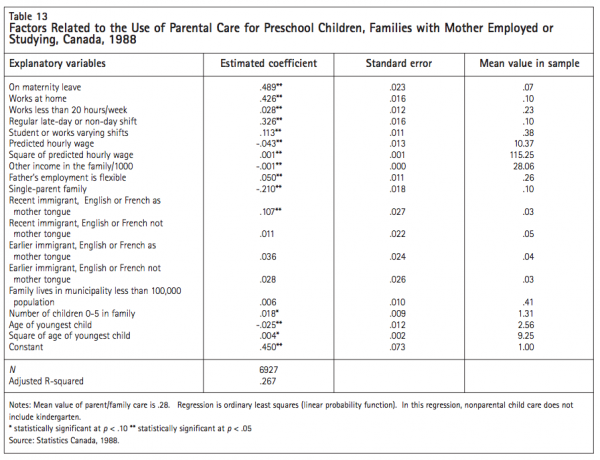

Table 13 gives us additional insight into the factors that affect the use of parental care by families with an employed or studying mother. This table looks at a range of family circumstances related to the choice of child care arrangements and the effects of each, holding the others constant. In other words, it analyzes factors related to the use of parent/family care in a regression framework. By necessity, it is based on data from the 1988 CNCCS.

Many of these factors are significantly associated with the decision to use parental care. The probability that any child uses primarily parental care while the mother is employed or studying varies from 0.00 to 1.00; the estimated coefficients in column two of the table tell us how much, on average, each factor (in column one) affects this probability. Naturally enough, being on maternity leave increases the probability by about .49 (i.e. by nearly 50 percent) of using primarily parental care for a child. When a mother’s usual employment is at her home, this is also strongly associated with using parental care for a preschool child. The probability of using parental care is higher by .43 for families in which the mother works at home.

Part-time work for a mother is also significantly associated with parental care, but the size of the effect is relatively small (approximately a .03 increase in probability). However, if a mother with a preschool child regularly works an evening or night shift, the probability of using parental care increases by about .33. If the mother is a student or works varying shifts week to week, parental care is also more likely (increased probability of about .11). Presumably, these three work situations for the mother would be typical ones in which a father might off-shift to provide care evenings or nights.

The above variables may well be correlated with a family’s income situation; the next variables, however, are explicitly economic. The CNCCS has no data on the hourly wages of mothers. However, part of the sample for the CNCCS overlaps with data from the Labour Market Activity Survey, which does have wage data. Lisa Powell (1997) used this unique situation to estimate wage equations for mothers. Using her results, we can predict wages for every mother in the CNCCS data set.

Our results show that mothers with higher wages are less likely to use parental than nonparental care, but this effect moderates somewhat at higher wage levels.19 For example, compared to the effects at a wage of $0 per hour, a mother earning $7 per hour (in 1988) would have a decreased probability of using parental care of .25. At the mean wage in the sample ($10.37), she would have a .34 decrease in probability of using parental care. At a wage of $20, she would have a .46 decrease in probability of using parental care. The effect is non-linear; at a wage of $30, the decrease in probability of using parental care is somewhat lower, at .39.

Other income in the family (in most families, the husband’s earnings) is negatively related to the use of parental care — the higher this other income, the lower the likelihood of the family using parental care. There are two offsetting factors that are likely to produce this result. The classic effect of higher other income in labour economics is to decrease the number of hours worked by the mother. This would make parental care more likely. However, higher other income also means more ability to purchase nonparental child care. Apparently this second factor dominates. However, the size of the net effect is small; an increase of $10,000 in other income decreases the probability of using parental child care by only .01.

If the father in the family is not employed or has flexible hours, parental (presumably paternal) child care is more likely (the probability is increased by only .05, however). Unsurprisingly, a single mother (who is employed or studying) is less likely to use parental care (decreased probability of .21).

Immigrant families are apparently somewhat more likely to use parental child care, but this result is consistent enough to be statistically significant in only one case out of four (recent immigrant whose mother tongue is English or French — 3 percent of the sample). In this one case, the size of the effect is substantial (increased probability by .11), but in other cases it is both small and insignificant. The size of the municipality in which a family lives does not affect the use of parental care when all other factors are taken into account.

Finally, the age of the (youngest) child is associated with the use of parental care. For instance, for a oneyear-old, there is a decreased probability (relative to a child less than one) of using parental care, but the probability decreases by only .02. The effect for a twoyear-old child is similarly small (-.01). Holding all other factors constant, fourand five-year-old children are somewhat more likely to receive parental care (perhaps because of the availability of kindergarten).

No doubt these regression results could be interpreted in different ways. However, this regression shows that the decision to use parental care (for a family in which the mother is employed) is very much an economic and work-related one. Those variables that are most closely associated with pure preferences (for parental care) would be immigrant status, living in a municipality with fewer than 100,000 people and the youngest child being at least one year old. However, these variables either are statistically insignificant or have a relatively small effect. It is the work, wage and income variables that explain most of the variation in the likelihood of using parental care.

Of course, the decisions to work part-time, to work at home or to work the evening shift are not unrelated to the decision to provide parental care. The desire to provide parental care may be part of the decision to work the evening shift, for instance. The point is that the decision to provide parental care is apparently very much related to the economic and employment circumstances of the family, and might well change if those circumstances were to change.

Summary

There are a number of sources of information on child care spending by families. The most detailed source is the CNCCS, but these data are from 1988. The Survey of Household Spending (SHS) is an annual survey (successor to the Family Expenditure Survey) that collects information on the entire range of family expenditures, including a small amount of detail on child care spending. In the SHS, spending is not associated with any specific child, so the figure given is an aggregate for all children in the family.

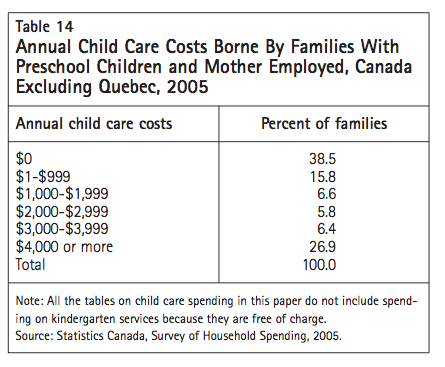

Child care spending by families is remarkable for its variation. Table 14, from the 2005 SHS, gives a snapshot of the distribution of annual child care spending by families with an employed mother and at least one preschool child. Because spending in Quebec is strongly affected by the availability of $7per-day child care, these figures do not include Quebec. Economists expect many variables will be distributed according to a bell-shaped distribution, with most of the observations in the middle and a smaller number at the extremes. The distribution of child care spending is the opposite. Nearly 4 out of 10 families have no child care expenditures. These are families using care provided by parents (some on maternity/parental leave), using care provided by close relatives, using only free public kindergarten or receiving full subsidy for regulated child care. Another 3 out of 10 spend between $1 and $2,999 per year on child care. These might be families with parents working part-time or part-year, paying a modest amount to relatives or purchasing low-priced informal care, but they would also include most of the subsidized families in Canada (excluding Quebec) using regulated child care. More than 3 out of 10 families spend a considerable amount on child care — $3,000 or more annually.

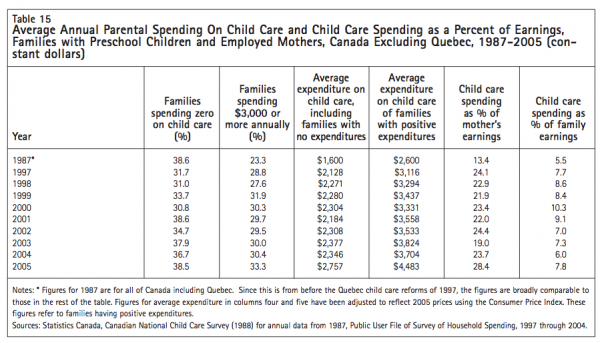

Table 15 shows trends in inflation-adjusted annual child care spending in the period 1987 to 2005. These data are from the SHS (with the 1987 data from the CNCCS). Again, spending by Quebec families is omitted; because of the availability of $7-per-day child care, average child care expenditures are considerably lower for Quebec families. In the rest of Canada over this period, there has been a modest upward trend in child care spending until 2005, when we see a sharp spike upwards.20

Although the total annual expenditure may seem low, it is substantial as a percentage of the mother’s annual earnings. There is fluctuation from year to year (apparently mostly in the denominator: the mother’s earnings). In nearly every year, the expenditure is over 20 percent of the mother’s earnings on average (and close to 30 percent in 2005). Total family earnings fluctuate as well, but child care spending is between about 5 percent and 10 percent of family earnings in different years (and close to 8 percent in 2005).

This points to two further questions. First we need to explore what factors influence the level of spending when families do have child care expenditures. Second, we need to discern what kinds of families have no child care expenditures. Before that, however, it is useful to review some recent evidence from the OECD about the burden imposed by child care costs in Canada.

The OECD, concerned about the workforce effects of population aging and about decreased fertility, has been investigating ways of improving the balance between work expectations and family responsibilities in OECD countries (OECD 2007). With evidence concerning average fees for regulated child care, and with software that simulates taxes, tax-related child care benefits, and a multitude of general and child carespecific benefits, the OECD has recently estimated the effect of child care costs and other factors on work incentives in its member countries (OECD 2005, 2007; see Kershaw 2007, 25-29, for similar work-incentive calculations for Alberta and British Columbia).

In Canada (Ontario, specifically), net child care costs, taking into account eligibility for benefits related to child care, are higher, for all family types considered, than the OECD average. For a family with two children, these costs range from 18 percent of net family income (for a family of two earners each earning 100 percent of the average production worker’s wage — APW) to 42 percent of net family income (for a singleparent family earning two thirds of the APW).

Employment decisions are made at the margin; the OECD (2005) further investigates the change in net household income (after accounting for changes in income and payroll taxes, benefits and net child care costs) when an earner moves from not being employed to being employed and using regulated child care. If the second earner in a married couple lives in Ontario, has two children aged two and three years, and earns two thirds of the APW, 78 percent of her increased earnings will be eaten up by child care fees, taxes and reduced benefits. In fact, if she earns minimum wage (about 35 percent of APW), her decision to be employed will have no net effect on household income, and even if she were to earn more than her spouse (110 percent of APW), she would increase spendable household income by only 50 percent.

The situation of single parents in Canada is less favourable still.21 If a single parent with two children two and three years old decides to be employed and can earn two thirds of the APW, child care fees, taxes and reduced benefits will eat up 97 percent of her increased income. This is the well-known “welfare wall”; employment may generate virtually no net financial reward for single parents with modest potential earnings. However, if this single parent were able to earn at the much higher rate of 90 percent of APW, her spendable household income would increase by 25 percent; if she could earn 110 percent of APW, her spendable household income would increase by 50 percent.

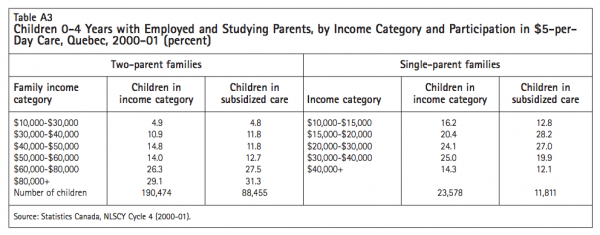

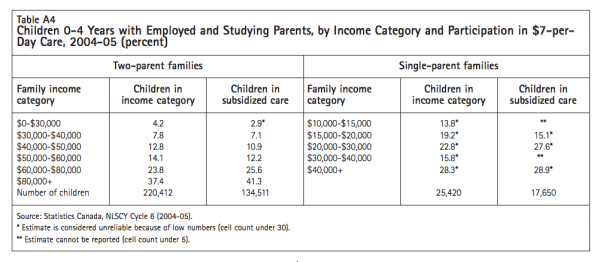

In this context, it is perhaps no surprise that the Quebec $5-per-day (now $7-per-day) child care reforms have had a significant impact on mothers’ employment. The universal lowering of child care fees to under $2,000 per year for full-time care has increased workforce participation, hours worked and annual earnings. Employment participation has risen at least 7 percentage points (Baker, Gruber, and Milligan 2005; Lefebvre and Merrigan 2005). Lefebvre and Merrigan (2005) and Lefebvre, Merrigan and Verstraete (2007) find especially strong employment effects for mothers with high school education or less. Overall, the $5-a-day policy has moved Quebec from a situation of lower employment rates than the rest of Canada amongst mothers with young children to a situation of consistently higher rates.

The puzzle with respect to family expenditure on early learning and child care is that many families have zero expenditures and many others quite high ones. In the following section, we will see that about 3 out of 10 families with an employed mother and a preschool child spend nothing on the purchase of ECEC services, and among those who do have such expenditures, the average expenditure, on all their children, is about $4,500. The picture that many analysts begin with — that families with a preschool child and two employed parents (or an employed single parent) must necessarily spend at least $6,000 to $9,000 per child per year — is apparently wrong. The OECD results discussed above suggest why many families do not spend this amount, but several factors influence spending patterns.

Most nonparental child care is expensive. In general, the higher the quality of the care, the more expensive it will be. Although care by a relative may cost nothing, it is available only to some, and very often only on a part-time or part-week basis. For most types of nonparental care, quality is closely linked to the caregiver’s level of training in child development and to the number of children looked after by the caregiver. Cleveland and Krashinsky (2004) estimate the full unsubsidized cost of centre-based care for a threeyear-old child to be more than $6,000 per year, even at a modest caregiver salary of $26,000, and close to $9,000 per year at a salary of $35,000 for staff trained in early childhood education.

There are two possible interpretations of spending patterns. These lead to different judgments about family and child well-being and have quite different policy implications.

It may be that good-quality child care is prohibitively expensive for many families and that, as a result, families do whatever they can to secure free or low-cost alternative care. These alternative arrangements would include having one parent work part-time, parents arranging their work shifts so they can share child care responsibilities, having one parent take salaried or self-employed work that can be done at home so that he or she can care for their child while working, having a relative provide care for little or no remuneration, obtaining a full subsidy for regulated ECEC, using free public kindergarten as a form of ECEC, or some combination of these various strategies.

This first interpretation leads to the judgment that good-quality nonparental child care is desirable but unaffordable for most, and that many families are choosing either nonparental care of inferior quality (inadequate for optimum child development) or inconvenient but free family care. Further, this interpretation suggests that families suffer considerable stress trying to provide child care through the family while holding down a job, or else are sacrificing considerable income to reduce their child care costs to an affordable level.

Alternatively, it may be that parents could readily afford good-quality nonparental care but are uncomfortable with purchased child care and prefer to spend time with their children themselves when the children are young. Even if less expensive non-family services were available, they would prefer not to use them. This second interpretation leads to the judgment that families are doing precisely what they want with their child care spending dollar. Many families spend nothing because they prefer parent, family and relative care. Many others spend only a small amount because they prefer part-time to full-time employment. Others spend a lot because they believe the expenditure brings them good-quality, enjoyable, healthy and safe experiences for their children, preparing them optimally for school and life.

Let us probe these alternative interpretations by looking at the factors that influence the decision to spend nothing on child care and, for those who do purchase child care, the decision with respect to how much to spend.

The literature includes a handful of economic studies on child care expenditure. Brayfield and Hofferth (1995), analyzing data from the US National Child Care Survey of 1990, find that it is economic factors, particularly those associated with the mother, that largely determine who pays for care, how much they pay and the share of earnings spent on care. “[I]t is out-ofpocket costs of care, mother’s wage and family income that will determine what type and quality of care is purchased” (p. 175).

Phipps and Burton (1998), using data from the Statistics Canada Family Expenditure Survey of 1992, find that families pool their incomes in deciding on some but not all categories of household consumption. Expenditures on child care are found to increase only with women’s incomes — higher male income is not associated with higher expenditure on child care even when both spouses work full-time, full-year. “Anecdotal evidence indicates that many couples ‘net out’ the costs of child care from the wife’s earnings in deciding whether it is ‘worthwhile’ for her to take a paid job. Child care seems still to be regarded as very much a woman’s responsibility. Our results confirm such ideas. Apparently, women can only ‘afford’ to work for low wages if they have ‘free’ child care from a parent or neighbour.” (Phipps and Burton 1998, 609-10)

Rosenbaum and Ruhm (2005) use the 1996 US Survey of Income and Program Participation to study the “cost burden” of child care, defined as child care expenses divided by after-tax income. There is wide variation in the cost burden across families, but it is not systematically related to a measure of socio-economic status that they construct, largely because lower-income families use lower-cost types of care and pay less than higher-income families for the care arrangements they make. Rosenbaum and Ruhm do not examine the relationship between mother’s predicted income and child care spending, and they are not able to control for the quality of child care used by different income groupings nor the “cost” burden of care provided by parents and relatives.

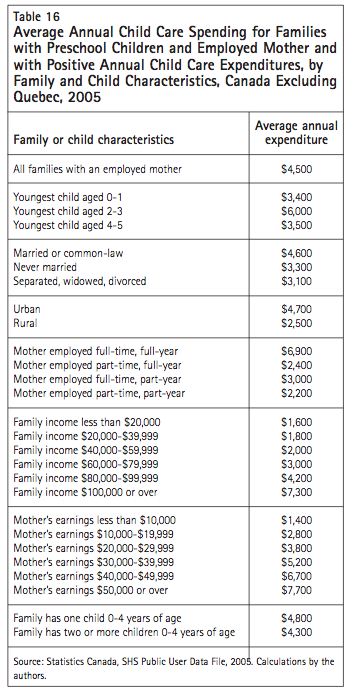

Table 16, using data from the 2004 SHS, shows that different family types spend different amounts on child care. Families with a twoor three-year-old spend more (kindergarten apparently reduces expenditures for older children, as do higher child-staff ratios). Married or common-law families and families living in urban areas also spend more.

The more “fully” employed the mother, the higher the family’s average child care expenditure ($6,900 if the mother is employed full-time, full-year). Child care expenditure is clearly related to family income and the mother’s earnings. Annual child care expenditures vary from $1,600 for low-income families to an average of $7,300 for those with an income of $100,000 or more. Child care spending is strongly related to the mother’s earnings, rising from $1,400 to $7,700 at an earnings level of $50,000 or more. Canadian families appear to value child care, and to be willing to spend a considerable amount on it when they have the means to do so.

Many factors affect child care spending. It is useful to try to separate out the individual influences of these distinct factors. Data on family characteristics that would allow us to analyze factors influencing child care spending are not available in the SHS, so we must use the data from the 1988 CNCCS. In 1988 the average weekly expenditure per child on purchased care for children with an employed or studying mother was $46.38.

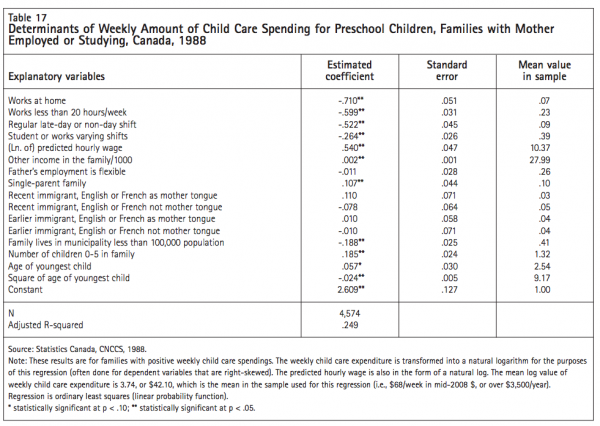

Table 17 shows the results of a regression of the amount of weekly child care spending in 1988 on what might be considered its key determinants. The results show just how important the mother’s employment and earnings situation is (or perhaps was in 1988) in explaining the amount spent each week on nonparental care.

Although an increasing number of families purchase ECEC purely for its developmental benefits, most families purchase child care to support the employment and education or training activities of the parents. In the majority of families, the mother earns less than the father. This, combined with traditional role definitions, means that it is most often the mother’s employment or study situation that triggers the need for nonparental care.

As a result, affordability of child care, for most families, appears to involve a comparison between the costs of care and the mother’s potential earnings. Families want the best care they can afford. As table 17 suggests, the higher the mother’s potential earnings, the more the family will spend on care (for better quality and more hours). Once the mother’s earnings are taken into account, then, “other family income” (generally the father’s earnings) plays only a minor role in the amount spent on care. If the mother’s potential earnings are low, the family may be forced to patch together arrangements of dubious quality (caregivers with no training). The care chosen may be purely custodial, rather than including developmental elements (see the evidence on the quality of unregulated care in the section on Quality, below). In many cases, these adjustments may involve a different employment situation for the mother, in order to decrease the cost burden of nonparental care.

The results shown in table 17 reveal that working at home decreases spending on nonparental care, as does working on a part-time basis. Part-time work often means evening and weekend work or variable shift arrangements. All of these employment situations are associated with less spending on nonparental child care.

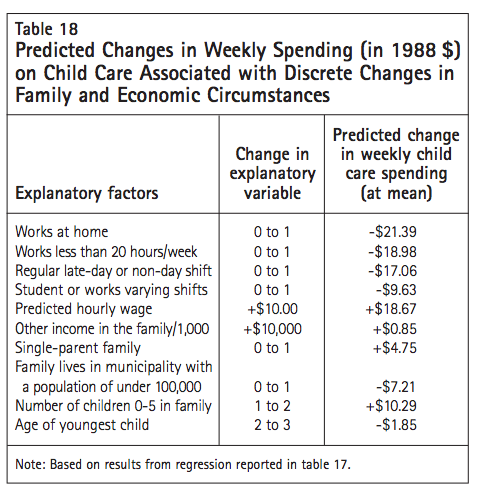

Table 18 takes the results from table 17 and expresses them in a more meaningful form. It shows the effect of discrete changes in the statistically significant variables on the predicted value of weekly child care spending.

Much of zero-priced child care is provided by parents, but relatives, neighbours, regulated centrebased or family home care and kindergarten can also provide zero-priced care. We can identify a number of ways in which families arrange care for their children without spending any money even if both parents have jobs.

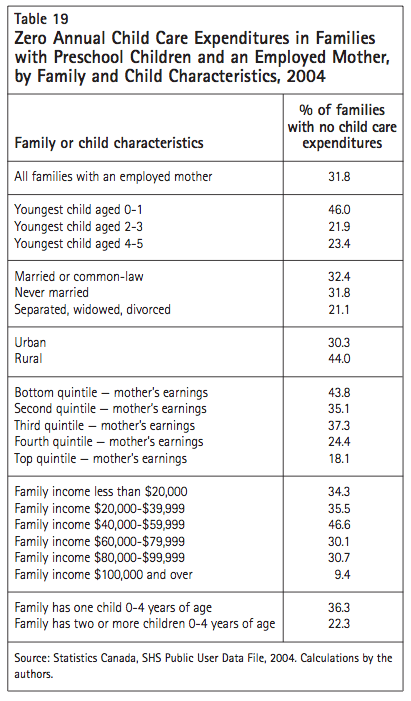

Table 19 considers the different factors that may affect the decision to use zero-priced child care. Not surprisingly, these results are very similar to those in table 13, explaining the decision of families to use parental care instead of some form of nonparental care. The majority of zero-priced care is provided by the child’s own parents.

Some nonparental care is available at a zero price, but this represents a minority of children. Indeed, in 1988 in Canada, about 390,000 children with an employed or studying mother used parental care (and paid zero), and only about 90,000 used nonparental care and, for one reason or another, paid a zero price. In other words, only 11.7 percent of children with employed or studying mothers who used nonparental care paid zero for it; the rest were charged some amount.

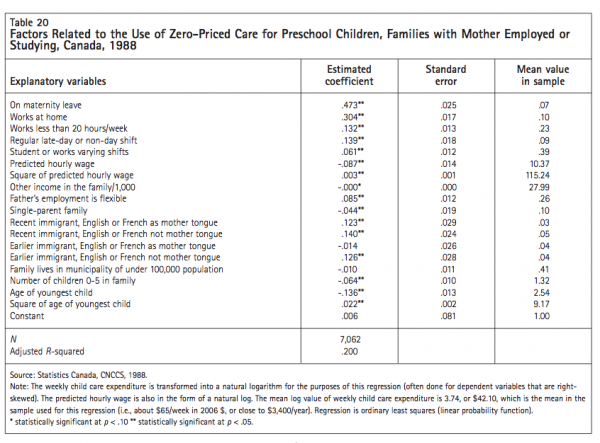

There are many factors that will affect the likelihood of families with preschool children and employed mothers paying zero for child care. Table 20 indicates the statistically significant factors with starred coefficients; these coefficients measure the impact of each factor on the probability of paying zero. Many of these factors are the same ones that increase the likelihood of parental care, such as the mother being on maternity leave, working at home or working fewer than 20 hours per week.

Our results show that mothers with higher wages are, in general, much less likely than those with lower wages to use zero-priced care. For example, we can calculate that, compared to the effects at a wage of $0 per hour, a mother who earns $7 per hour (in 1988) would have a decreased probability of .46 of using zero-priced care. At the mean wage in the sample ($10.37), a mother would have a decreased probability of .58

Other income in the family (in most families, the husband’s earnings) is negatively related to the use of zeropriced care, but the effect appears to be negligibly small.

If the father is not employed or has flexible hours, then zero-priced (often paternal) care is more likely (increasing the probability by .09). A single mother (who is employed or studying) is slightly less likely to use zero-priced care (decreased probability of .04).

Immigrant families, according to the results discussed earlier, are generally not more likely to use care by a parent while the mother is employed. However, they apparently have other sources of zeropriced care (e.g., live-in relatives). Immigrant families who have been in the country more than 15 years and whose mother tongue is English or French are similar to native-born families. However, both of the other immigrant categories (in the country more than 15 years but with a different mother tongue; in the country less than 15 years with any mother tongue) are more likely to use zero-priced care (increased probability of .12 to .14).

This regression gives evidence that the decision to use zero-priced rather than paid nonparental care is very much an economic and work-related one, as well as being influenced by cultural and preference factors. While immigrant status and the age of the child affect the use of zero-priced care, employment and the mother’s wage variables are central explanatory factors related to the use of zero-priced care.

Research evidence concerning the effects of child care quality on different aspects of child development is now widely available. The results suggest that child care matters to children’s development, particularly in a high-quality learning environment (Doherty 2007, 30-36; Gormley et al. 2005; NICHD and Duncan 2003; Vandell 2004).

There is some concern about possible negative behavioural effects of group child care arrangements, particularly for very young children and when quality is poor.23 However, context seems to matter for findings on behaviour24 and, overall, the best evidence we have is that quality is the key feature of child care programs that promote child development. In From Neurons to Neighbourhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development, Shonkoff and Phillips (2000) summarize their findings based on the literature on child care quality and child development:

In sum, the positive relation between childcare quality and virtually every facet of children’s development that has been studied is one of the most consistent findings in developmental science. While child care of poor quality is associated with poorer developmental outcomes, high-quality care is associated with outcomes that all parents want to see in their children, ranging from co-operation with adults to the ability to initiate and sustain positive exchanges with peers, to early competence in math and reading… (p. 313-14)

Although child development research has identified quality as the most consistent factor in the influence of child care on children, Canada has little statistical information on the quality of its ECEC services. Ignoring a few small, localized studies, Canada’s information on child care quality comes from three data sources: the You Bet I Care! study of 223 child care centres and 231 regulated family child care homes in six provinces and one territory in 1998; the Grandir en qualité study of 705 infant and preschool rooms in child care centres and 200 regulated family child care homes in Quebec in 2003; and the ÉLDEQ, which collected information on 1,540 ECEC arrangements used by a sample of children two and a half to five years old in Quebec in the period 2000 to 2003.

Each of these studies provides data on the quality of child development based on in-depth on-site inspection. The ÉLDEQ is distinct in that it entailed inspections of quality in whatever child care arrangements families were using, including unregulated care. None of the studies provides good data on the quality of care provided by relatives, provided in kindergartens, nursery schools and preschools, or provided by parents. Such data can be collected and some studies in the United States have done so.25

The ÉLDEQ began, in 1998, to collect data on a representative sample of children born in Quebec from October 1997 through July 1998. The study included an evaluation of the quality of child care settings attended by these children after they reached the age of two and a half years. It evaluated not only nonprofit centre-based settings (CPEs — Centres de la Petite Enfance), for-profit centre-based settings (garderies) and regulated family child care (homebased CPEs), but also unregulated home-based settings. The evaluation of the quality of unregulated care is virtually unprecedented in Canada, making this data source particularly valuable for the study of the quality of child care settings.

The sample included 2,223 children but only 1,540 on-site evaluations were conducted: 728 in centrebased CPEs, 337 in home-based CPEs, 296 in for-profit centres and 179 in unregulated home-based settings.

The instruments used to evaluate quality (the Early Childhood Environments Rating Scale — Revised, or ECERS-R [Harms, Clifford, and Cryer 1998], and the Family Day Care Rating Scale, or FDCRS [Harms and Clifford, 1989]) have frequently been used in studies of this type and provide a global assessment of the quality of the service provided. As Japel, Tremblay, and Coté (2005) put it, “These scales, whose validity and reliability are well established, measure the parameters elaborated by the NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children in the U.S.) to ascertain whether a particular setting is conducive to child development” (p. 11).

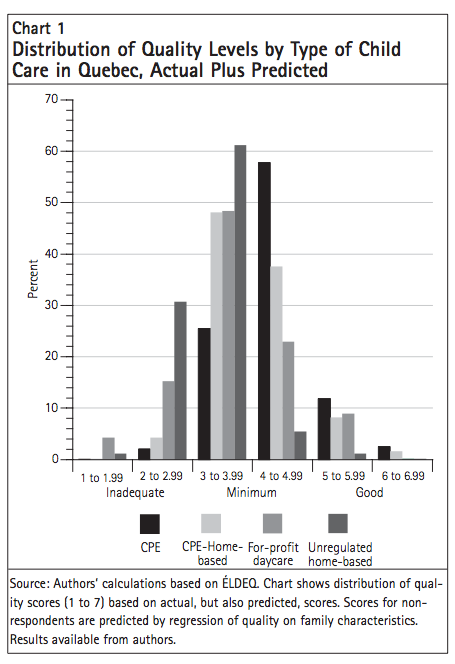

The ECERS-R, for example, consists of 470 indicators grouped into 43 items in 7 subscales (Space and Furnishings, Personal Care Routines, Language and Reasoning, Activities, Interactions, Program Structure, Parents and Staff). Each centre gets a quality score from 1 to 7. A score of 1 is “inadequate,” 3 is “minimal,” 5 is “good” and 7 is “excellent.”

The ÉLDEQ findings show that the majority (about 70 percent) of all child care arrangements score below the level of good developmental quality. While the majority of these are not harmful to children, neither do they stimulate development in a way that would be considered adequate. Just over 10 percent of arrangements are problematic in terms of quality (below minimal), another 25 percent are just over minimal quality and therefore well below the level needed for desired child development, and a further 35 percent are just below good quality on average. Only about 5 percent of arrangements are truly exceptional (between 6 and 7 on average).

The adequate and inadequate child care arrangements are not randomly distributed across types of care. While just over 10 percent of all measured arrangements are considered inadequate (i.e., below minimal quality), this is true of just over 5 percent of centre-based and home-based CPEs. However, just over one out of every four arrangements in a for-profit centre or an unregulated family home is inadequate by this measure.26

Similarly, while about 27 percent of all arrangements are of good quality, this is true of less than 15 percent of for-profit centres and about 10 percent of unregulated family homes. About 35 percent of centre-based CPEs and about 30 percent of home-based CPEs score in the good-quality range. This distribution is also reflected in the average scores for each type of arrangement. The average score is 4.53 for centre-based CPEs and 4.32 for home-based CPEs. For-profit centre-based arrangements have an average quality of 3.65, while unregulated home care averages an almost identical 3.64.

Chart 1 shows how much difference there is in the underlying distributions of quality for care of different types. Very few unregulated home care arrangements are above the midpoint on the quality scale; the vast majority score below 4. The majority of centre-based CPEs are in the top half of the scale. Home-based CPE care is oriented towards lower quality, with both lowand high-quality facilities. For-profit care is more strongly distributed towards lower quality.

The Grandir en Qualité data were collected in Quebec in 2003 to construct a snapshot of the quality of child care provided in CPEs, garderies and regulated family child care arrangements (coordinated by CPEs).

This study (Drouin et al. 2004)27 collected data from a large number of CPEs (N = 228) providing centre-based care for preschool children (18-59 months); garderies (for-profit daycare) (N = 225) providing centre-based care for preschool children; CPEs (N = 128) and garderies (N = 124) serving infants; and family child care providers (N = 200) affiliated with CPEs and serving children of all ages. In contrast to the ÉLDEQ, the Grandir en Qualité study did not include unregulated settings.

The Échelle d’observation de la qualité éducative (Bourgon and Lavallée 2003) was developed specifically to measure conformity with the principles behind the educational program of regulated child care in Quebec. Three versions of the quality measurement instrument were developed — one for infants in centres, one for preschool children in centres and one for children in family child care. The scales comprise four dimensions: physical layout of facilities, organization of activities, interaction between educators and children, and interaction between educators and parents. The first scale has two subscales: physical arrangement and materials and equipment. The second scale, measuring activities, has four subscales: planning, observation, daily schedule and play activities. The interaction scale has three subscales: value placed on learning through play, democratic modes of intervention and positive communication.

The four dimensions are averaged in determining the score for each group of children chosen. Each item that makes up the subscales and scales is rated from 1.0 to 4.0, so that the range is essentially three points. Average scores up to the midpoint of this range (i.e., 1.0 to 2.49) are considered to represent unsatisfactory quality, with the first third of this unsatisfactory range corresponding to very poor quality, the next third to poor quality and the final third (i.e., 2.00 to 2.49) to somewhat poor quality. Average scores of 2.50 to 4.00 are considered satisfactory, with the lowest third of this range corresponding to fair quality, the next third (i.e., 3.00 to 3.49) to good quality and the final third to very good quality.

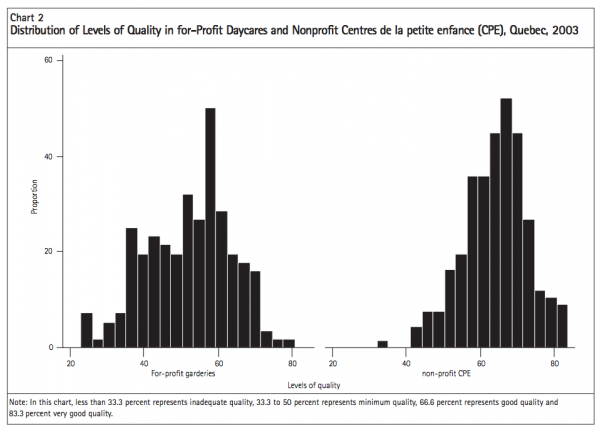

Looking at preschool classrooms only (in this data set, preschool is defined as covering 18-59 months), we find substantial gross differences in quality, on average, across nonprofit and for-profit centres. Measured on a scale of 1 to 4, nonprofit CPEs rate an average score of 2.93, garderies an average score of 2.58. If we transfer these scores onto a percentage scale, for-profit centres score, on average, 52.5 percent, whereas nonprofit CPEs score 64.2 percent. In other words, there is a 12-percent difference between these two types of centre (or the quality of CPEs is, on average, more than 22 percent superior to that of garderies). This is a substantial difference, greater than one standard deviation (s.d. of index quality is .26 for CPEs and .34 for garderies).

We have depicted the sample distributions of quality on a graph. Chart 2 shows two histograms of quality scores (in percentage terms). The histogram on the left shows scores for preschool classrooms in garderies, the one on the right for CPEs. Somewhat less than half of the mass of the left-hand distribution is below the 50-percent mark on the quality scale (i.e., unsatisfactory). In contrast, only a small part of the right-hand distribution lies below 50 percent. In these graphs, 66.6 percent represents good quality and 83.3 percent very good quality. Only a small number of garderies are in the good or very good range, compared to a substantial number of CPEs.

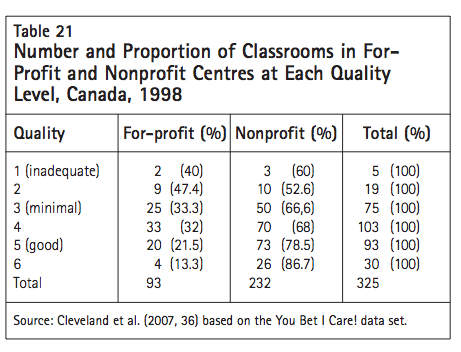

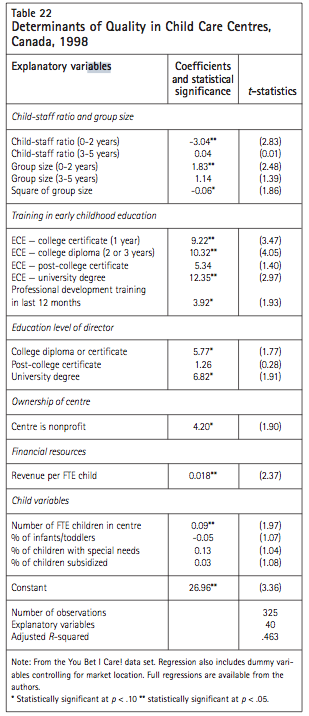

You Bet I Care! is the collective name for a group of linked data sets investigating earnings, working conditions, and observed quality in daycare centres and licensed family homes in Canada in 1998.28

The two main measures of classroom quality in this data set are the Infant-Toddler Environment Rating Scale (ITERS) and the ECERS-R, which are global measures of the developmental potential in the classroom (the environment fostering interactions). The updated version of the ECERS-R (Harms, Clifford, and Cryer 1998) comprises 43 items that evaluate seven aspects of centre-based care for children from two and a half to five years.29