Le système canadien d’aide financière aux étudiants devrait faire en sorte que tout Canadien possédant les aptitudes requises dispose des ressources nécessaires pour pouvoir poursuivre des études post-secondaires sans que cela n’entraîne des difficultés indues. Or, bien que le système actuel présente de nombreux avantages et vienne en aide à de nombreux étudiants, il est néanmoins très complexe et n’accomplit pas son objectif aussi bien qu’il le pourrait et ce, en dépit des changements annoncés par le gouvernement fédéral en février 2004. Dans cette étude, Ross Finnie, Alex Usher et Hans Vossensteyn recommandent une réforme du système et proposent une nouvelle « architecture » de l’aide financière aux étudiants. En lieu et place de la pléthore de programmes présentement offerts aux étudiants, ils proposent un programme unique qui accorderait l’aide à ceux qui en ont besoin sans gaspiller les fonds publics sur ceux qui n’en ont pas besoin.

Dans la première partie, les auteurs présentent le système actuel, qui comprend le Programme canadien de prêts aux étudiants et des programmes similaires établis dans les provinces, ainsi que de nombreux programmes de subventions et de bourses d’études (dont ceux qui sont administrées par la Fondation canadienne des bourses d’études du millénaire), de crédits d’impôt pour études, de subventions à l’épargne-étude, de régimes enregistrés d’épargne-étude, de remises de dettes, d’exemptions d’intérêts et de réductions de dettes en cours de remboursement. Ils en soulignent les principales défaillances, relevant notamment les aspects suivants : les crédits d’impôt pour études représentent une part excessive de l’aide aux étudiants et sont mal ciblés; il est trop facile d’être admis dans la catégorie des étudiants « indépendants » ; les plafonds de l’aide sont inadéquats; les attentes relatives à la contribution financière des parents sont souvent erronées et les enfants de parents qui ne contribuent pas sont pénalisés; et enfin, la remise de dettes n’est pas un moyen efficace de venir en aide aux étudiants. Selon les auteurs, le système canadien – qui, même à l’échelle internationale, se distingue par sa complexité et son absence de ciblage d’une bonne partie de l’aide accordée – ne fournit pas assez d’argent aux étudiants qui en ont besoin tandis qu’il en subventionne d’autres qui pourraient se passer de cette aide.

Dans la deuxième partie, les auteurs passent en revue les différents régimes mis en place à l’étranger et constatent que l’aide que reçoivent différentes catégories d’étudiants varie sensiblement suivant le régime adopté. Le dosage des programmes dans chaque pays dépend de plusieurs facteurs, et notamment des choix de chacun pour ce qui est de déterminer à qui incombe au premier chef la responsabilité de défrayer le coût des études : l’étudiant, les parents ou l’État, ou encore une combinaison des trois. Ils montrent que le régime canadien est présentement principalement centré sur l’étudiant mais qu’il comprend aussi certains traits du modèle « parental », une caractéristique qui s’est accentuée depuis quelques années, avec l’augmentation des dépenses liées aux crédits d’impôt et aux subventions à l’épargne.

Les auteurs procèdent ensuite à un exposé détaillé de la nouvelle architecture suggérée. Celle-ci ressemblerait en plusieurs points au système déjà en place, mais comporterait plusieurs changements-clé ainsi que de nouvelles façons de procéder. Le coût des études – frais de scolarité et autres, équipement et fournitures, frais de subsistance – serait calculé au moyen de formules standardisées et faciles à comprendre, comme cela se fait à l’heure actuelle. Ensuite, des formules tout aussi simples et équitables seraient mises au point pour déterminer quelle devrait être la contribution de l’étudiant, en fonction principalement de ses gains d’emploi et de l’aide reçue des parents ou du conjoint. L’écart entre le coût des études et les ressources disponibles serait alors entièrement comblé par l’aide financière. À ce chapitre, le système suggéré se distingue du régime actuel dans lequel les prêts et bourses sont assujettis à des plafonds arbitraires qui s’avèrent souvent inférieurs aux besoins des étudiants, même lorsque ces besoins sont calculés par le programme lui-même.

Les auteurs suggèrent qu’une tranche initiale de 5 000 dollars par année soit accordée sous forme de prêt et le reste sous forme de bourse. Cela aiderait à maintenir l’endettement à des niveaux raisonnables, et les bourses, une forme d’aide beaucoup plus coûteuse, seraient données aux étudiants aux prises avec des frais plus élevés ou qui sont issus de familles moins aisées. En outre, ils recommandent de mettre en place un mécanisme supplémentaire pour venir en aide aux étudiants dont les parents n’auraient pas fait la contribution attendue ou qui seraient incapables d’assumer leur propre part des frais.

Enfin, une aide supplémentaire serait offerte à ceux qui font face à un fardeau d’endettement excessif après avoir terminé leur scolarité, aide qui serait établie en fonction de leur rapport dette/revenu, une forme d’aide qui existe déjà mais qui gagnerait à être améliorée et bonifiée. Comme solution alternative, on pourrait mettre en place un mécanisme de remboursement lié au revenu, suivant lequel les versements seraient fonction de la capacité de remboursement de l’individu.

On pourrait financer un tel système, disent les auteurs, en réduisant ou éliminant certains programmes actuels. Ils citent en tout premier lieu le programme de crédits d’impôt pour études (qui représente 37 p. 100 des dépenses totales en aide aux étudiants) et divers programmes d’épargne-étude qui s’adressent aussi bien aux étudiants fortunés – et ont même plutôt tendance à les favoriser – qu’à ceux qui sont sans ressources. On pourrait également réaliser des économies supplémentaires en éliminant les programmes de remise de dettes. Enfin, les auteurs proposent que soient renforcées les règles qui régissent l’admission à la catégorie d’étudiant « indépendant » de façon à en soustraire ceux qui sont issus de familles à revenu élevé et qui réussissent à tirer avantage du système par ce moyen.

Canada’s student financial aid system should have a relatively simple primary function: to ensure that every qualified individual has the financial means to pursue post-secondary studies without suffering undue hardship. In other words, cost should not be a barrier to going to college or university.

Beyond this broad objective, more specific aspects of the definition of access arise. We choose to view the concept as including the following aspects: individuals are able to enrol in their programs of choice (provided, of course, that they qualify); they have the opportunity to attend the institutions they prefer, even — importantly — if that means moving to another town (again assuming they meet the relevant entry standards); they need not work at outside jobs during the school year to the degree that it adversely affects their studies; and paying for the schooling does not put unreasonable demands on family resources or lead to the accumulation of excessive debt burdens in the post-schooling period.

This may sound simple, or even obvious. And one might reasonably expect, given the plethora of student-aid-related programs in existence, that the current system is doing its job by removing financial barriers to post-secondary education. After all, we have the Canada Student Loans Program and its provincial counterparts, the Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation, myriad grant programs at both the federal and provincial levels, debt-remission programs, programs that help individuals who are having difficulty repaying their student loans in the post-schooling period, education-related tax credits, Canadian Education Savings Grants, Registered Education Savings Plans, all kinds of institutional-level support and more — all of which costs almost $5 billion each year.1

Unfortunately, these programs are not doing the job — or at least not the full job — of guaranteeing access in the manner intended. They don’t get enough money to some who need it, and they provide support to some who don’t (Hemingway 2003b; Usher 2004a). We should be doing better.

What is needed is a “new architecture” for student financial assistance in this country. We propose replacing the current hotchpotch of programs with a single program that effectively and efficiently delivers support to those who need it without squandering scarce dollars on those who don’t. The good news is that this system could be developed without inventing a whole new set of structures and procedures from the ground up — a disruption that would carry its own set of special challenges and costs. The even better news is that we could implement such a system without spending any new public money. This is one policy area where the solution depends not so much on finding new and more financing as on doing better with the existing resources.

Not only is reform of the student financial aid system possible, but it is also important, since providing every Canadian with the chance to pursue post-secondary studies is both a basic issue of fairness or social justice and an essential step to ensuring that we have the skilled labour force needed in the emerging knowledge-based economy in the years and decades to come.2 The student financial aid issue is a case where doing the right thing also makes good economic sense — a potent context for policy discussions.

In this paper, we begin by describing the existing student financial aid system and its main shortcomings. We then place the issue in an international perspective by reviewing the various approaches to providing student assistance in existence around the world and situating the Canadian system in that context. This leads us to a description of the “new architecture” that we propose, including not only the key elements of the plan, but also a consideration of some of the associated design and implementation challenges. The concluding section summarizes the major points of the paper and identifies the policy debates that might be expected should Canada begin to move toward such a system.

The Canadian system of student assistance, which is an area of joint policy responsibility between the federal and provincial governments, is dauntingly complex. There are loan programs at the federal and provincial levels, provincial need-based grant and debt-remission programs, other grants for particular demographic groups and those in certain disciplines (for example, Aboriginals and female graduate students in the sciences), still more grants and tax credits for families who save for their children’s educations, other tax credits to help defray direct expenses (tuition fees and the standard education credit) and the interest paid on student loans, various forms of institution-based aid, privately funded bursaries, and more. The major components of this system will now be described in turn.

We pay the greatest attention to the major loan and grant programs, since our new architecture essentially builds upon these while eliminating most other major sources of aid. These alone, however, comprise a complex system. As one recent publication noted,

it has two national loan programs (one for full-time students and one for part-time students). It has three quite separate methods of providing assistance to students (need-based, income-based, and universal grants). It has five national grant programs, seven provincial/territorial (P/T) loan remission programs, eight P/T grant programs, 12 P/T loan programs, 13 P/T student assistance programs, 15 major providers of public student assistance, over 40 different student assistance limits (depending on a student’s province, marital status, dependents, and level of study), more than 100 different loan/grant combinations within these aid limits, and hundreds of thousands of possible aid configurations once assessed need is taken into account. (Junor and Usher 2002, 115)

But despite the complexity and variation that exist across the country, most student loan and associated need-based grant systems follow a single paradigm. As we will see in the international section, the Canadian system is an example of the student-centred model, as are the systems of Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Japan and the United States.

In Canada, close to 99 percent of all need-based loan and grant assistance goes to full-time students (defined as carrying at least 60 percent of a full course load). A similar percentage of aid is given on the basis of assessed need as opposed to personal or family income. While it may seem odd to distinguish between need and income in this fashion, the distinction is crucial, as the former term includes an examination of costs as well as resources.

The manner in which costs and resources are assessed differs slightly from province to province. In general, accepted costs include the following items:

The resources considered to be available to the student are the following:

The principal contributions on the part of parents and students are deemed, or estimated, and they therefore do not necessarily represent actual amounts. The true parental contribution may, for example, range from zero to much more than the indicated amounts, while students may earn and save more or less than what the standard formulas assume. While such an approach means that the different circumstances faced by individual students are not taken into account, it is a relatively efficient and nonintrusive means of calculating students’ needs and is similar to those used in other countries.

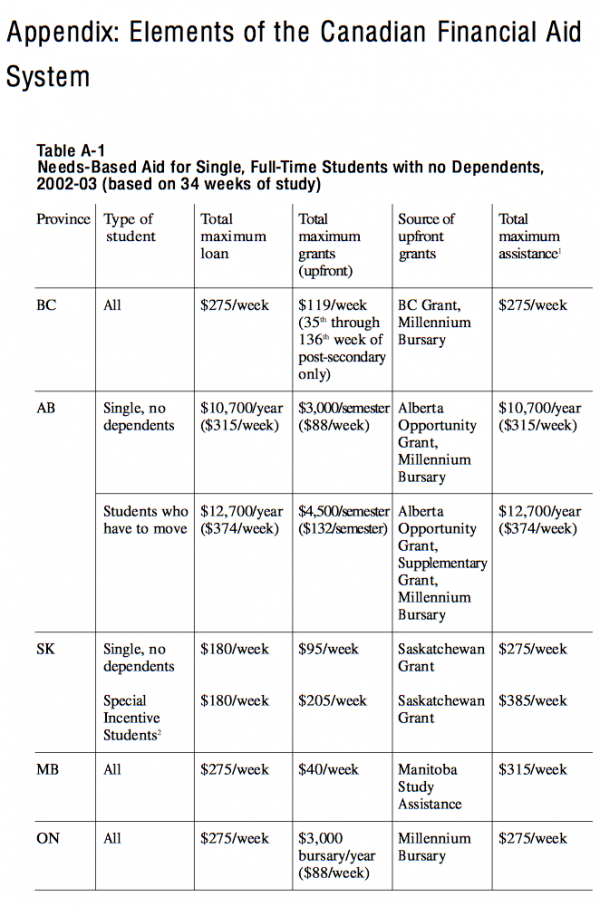

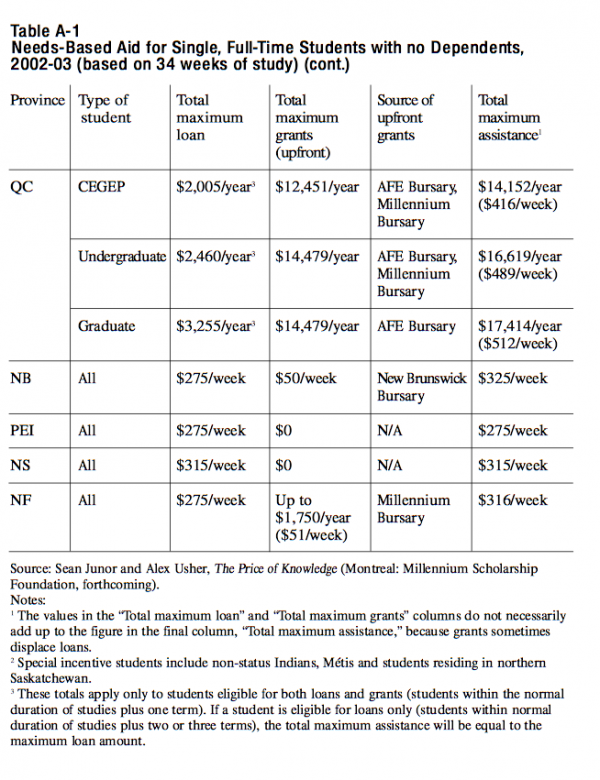

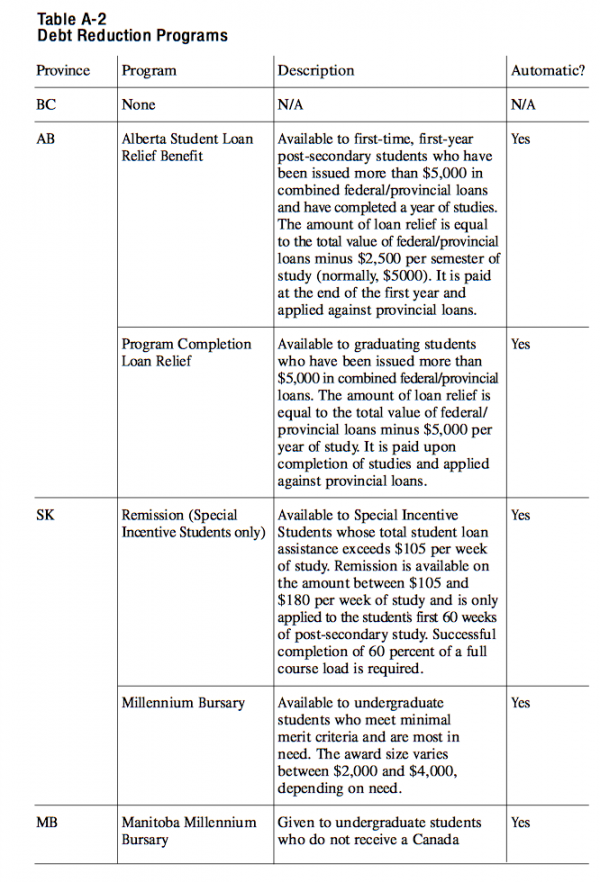

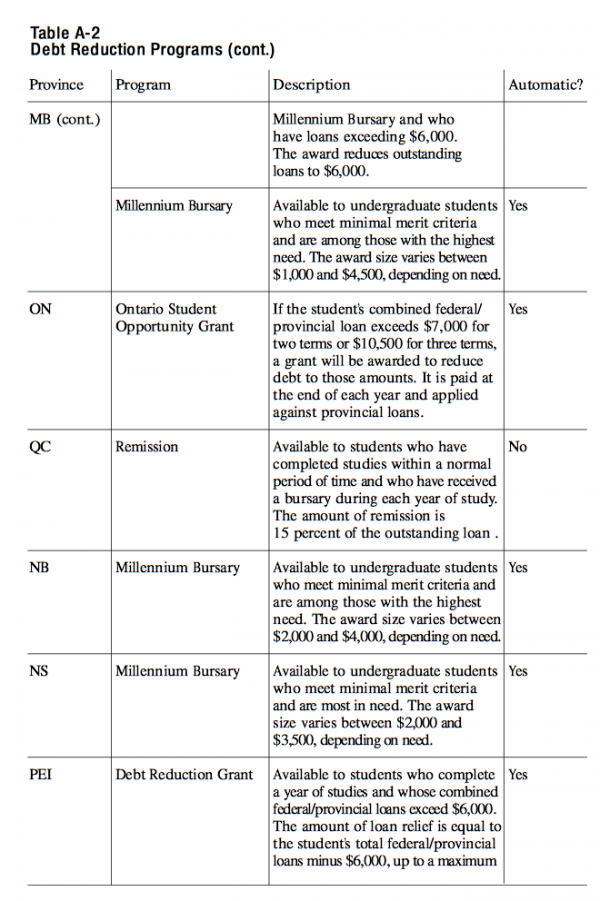

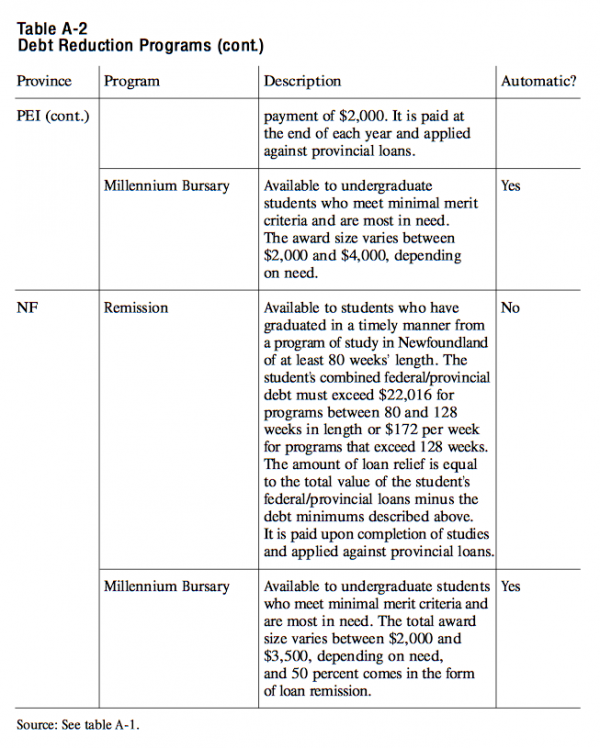

The first dollars of need — costs minus resources — are always met by loans. Only if the loan attains a certain level does a student become eligible for grants. The exact level at which loans turn into grants differs by province (see appendix A for these and other details regarding the country’s need-based grant and loan programs), but in much of the country it is in excess of $7,000 per year. In a number of provinces (British Columbia, Quebec, Alberta and Ontario), some or all grants are provided up front — that is, at the same time that loan assistance is distributed, in September and January. In other cases (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and the four Atlantic provinces), grants are provided as loan remission after a student has successfully completed a year of studies (see appendix A for details). Loan assistance is always portable across provincial boundaries. In most but not all cases, grant assistance is portable as well.

Although the student assistance system calculates need for all students, it does not necessarily meet that need. In most provinces, the maximum assistance available for a single student with no dependents is $275 per week, or $9,350 for a standard 34-week school year. For students with children, the amount ranges from $315 per week ($10,710 per year) to $500 per week ($17,000 per year). Quebec has much higher assistance limits but also a stricter need-assessment system, which makes it more difficult for its students to attain greater amounts of support. Remarkably, these maxima, with small exceptions, have remained unchanged since 1994, although in its March 2004 budget, the federal government outlined a plan to increase these limits and allow students to borrow greater amounts.

While a student remains enrolled on a full-time basis, governments pay the interest on the student loan. At the end of studies, interest begins to accumulate on the loan, but students are not required to make payments during an initial six month grace period (although interest accumulates). After the six months are up, students must begin paying back their loans at a steady rate.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, there have been four different regimes under which student loans are issued and repaid. Before 1995, private financial institutions issued loans, although government loan programs determined eligibility, and institutions could not refuse to issue a loan that had been approved. Governments — both federal and provincial — guaranteed these loans by committing themselves to buying defaulted loans at full value (including outstanding interest) from the lending institutions. From 1995 to 2000, instead of acting as guarantor, the government paid lenders a 5 percent risk premium on all loans going into repayment in a given year. In return, the banks assumed virtually full responsibility for collection. When the 1995-2000 agreement ended, an interim arrangement was put into place whereby the government became the lender (although it continued to issue loans through private institutions) and assumed full responsibility for all new loans issued. Since 2001, the government has issued student loans directly and assigned their management and collection to private companies brought into existence for this purpose.

For the most part, student loans are meant to be repaid within a 10-year period, although a substantial proportion of students manage to repay their loans within a shorter period (Finnie 2001b). During the repayment period, borrowers in repayment are eligible for “interest relief” (IR) if they have high debt-to-income ratios. More recently, the very few students whose debt-to-income ratios are persistently high over a period of three years or more have become eligible for “debt reduction in repayment” (DRR), which reduces the principal owed, but this program has had miniscule participation rates to date.

Nine provinces and one territory participate in the Canada Student Loans Program. In these places, need is met — in theory, at least — on a 60/40 basis; that is, the Government of Canada provides assistance equal to 60 percent of need up to a maximum of $165 per week, while the provinces pay the remaining 40 percent. Given that many provinces also provide assistance over $275 per week to students with dependents, and that provinces are typically larger per capita providers of grant assistance, the actual distribution of overall student assistance costs is actually closer to 40/60.

Quebec, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut have chosen to opt out of the Canada Student Loans Program. They have their own loan systems, to which the Government of Canada contributes through a system of alternative payments, which are built into the national student loans legislation (the Canada Student Loans Program was, in fact, the first federal program that provinces were permitted to opt out of with compensation). Quebec’s program is run on the same basic principles as those of the rest of the country, with three main differences. The first is the levels of expected parental contribution, which are much higher than those in other provinces. The second is that the system involves far more grants than loans. Until 2004, undergraduates received only the first $2,400 per year of assistance as a loan, with the rest of the assistance package coming as a grant (the 2004 provincial budget raised the loan ceiling to $4,000 per year). Finally, the limits on assistance are much higher than elsewhere: nearly $500 per week for single, independent undergraduate students, and close to $650 per week for those with dependents.

Roughly integrated with this system of loans and grants is the Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation (CMSF). This large nongovernmental organization — created by an act of Parliament in 1998 and endowed with $2.5 billion to be spent primarily on need-based grants over a 10-year period starting in 2000 — is the country‘s largest single provider of nonrepayable assistance. The foundation divides its roughly $285 million in annual bursary expenditures into equal per capita shares for students in all 10 provinces and 3 territories. Yet the foundation does not run a national program in any real sense. Instead, it effectively operates 13 parallel programs in conjunction with each province (as per its mandate). In Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, British Columbia and the three territories, foundation money arrives in the form of a grant in the second term of a student’s academic year. In the rest of the country, the money is used as a form of remission to reduce outstanding student debts.

The explicit legislative mandate of the CMSF was to provide scholarships to Canadian students in order to improve their access to post-secondary education. The government, however, surrounded the CMSF mandate with strong suggestions that the way to do this was to reduce the amount of debt that students were accumulating — as opposed to, say, issuing grants or additional loans on top of existing levels of assistance, thus making more money available to students to meet their direct schooling and related living costs. The foundation has, therefore, largely substituted grants for loans, thus reducing student debt levels, while having questionable effects on access. Furthermore, to a large degree the CMSF funds have simply displaced provincial spending on existing grant and loan remission programs.3 The foundation’s program is not unique in this respect; Canada Study Grants for Students with Dependents have also displaced large amounts of provincial funds. The problem is not so much with the foundation itself as with the inevitable complications of two levels of government competing to give money to the same student on the basis of the same criteria. It is this kind of duplication and overlap that a new architecture could help to eliminate.

Overall, the Canadian student loan system reaches about 450,000 university and college students each year, and about 40 percent of all post-secondary graduates borrow from government programs at some point during their schooling (Finnie 2001a, 6). Students receive approximately $3 billion each year in loans and $1 billion to $2 billion in grants, depending on what exactly is counted, and how. The cost to governments of providing this assistance is somewhat uncertain because there is no standard methodology for measuring expenditures, but it is likely in the range of $2.3 billion to $2.4 billion. Slightly under half of the total grant money comes in the form of back-end remissions.

Canada has used tax expenditures to subsidize students for over 40 years. Tax expenditures can be viewed as direct spending programs delivered through the tax system, and those related to post-secondary education are in this sense little different than traditional direct student-aid programs.

Tuition fees and a monthly “education amount” were originally tax deductions. But since these deductions provided more benefit to those with higher incomes (who have higher marginal tax rates), they were — like numerous other tax deductions — turned into the somewhat less regressive tax credits in the 1987 Tax Reform. At present, all tuition and compulsory fees (save student association fees) are eligible for the tuition tax credit, while the value of the monthly education-amount tax credit was raised from $200 to $400 ($200 for part-time students) in 2000. Students may use these credits in one of three ways. They may employ them to reduce their own current tax liability; they may transfer them to a parent, guardian, spouse or grandparent to reduce their current tax liability; or they may carry forward the value of any unused credits to reduce their tax liability in subsequent years. As with all other tax credits, the value of the credit is multiplied by the lowest tax rate (currently 16 percent) and the resultant amount is credited against tax owing.

In addition to these credits, there are a number of smaller tax expenditures. These include the deduction for moving to study (students who move to study may deduct expenses related to the move); the deduction for scholarship income (the first $3,000 of income from scholarships in any year is tax-free; in Quebec, all scholarship income is tax-free); and the student loan interest tax credit (a tax credit is given equal to the value of interest paid on a student loan during a calendar year; this may be used immediately to reduce tax payable or carried forward for up to five years).

These tax expenditures originate in the federal income tax code. But because provincial taxes are linked directly to federal taxes, tax expenditures at the federal level also result in provincial tax expenditures. Quebec, having its own tax system, also has its own set of tax expenditures, and certain other provinces have their own education-related tax provisions in addition to those that derive from the federal system. For example, Ontario has tax credits related to the hiring of co-op students, while Saskatchewan has a special one-time non-refundable tax credit of $350 to encourage recent graduates to stay in the province after graduation.

In addition to these forms of tax-based assistance, which are intended to offset education-related expenses directly, other tax-based measures have been put in place to encourage savings. Since 1972, the Canadian tax code has given special status to Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs). RESPs are savings accounts that permit tax-deferred growth (growth in the fund is left untaxed until income is withdrawn, at which time it becomes taxable in the hands of the beneficiary). Up to $4,000 per year may be contributed to an RESP. These vehicles are mostly used by upper-income families, who have the means to save and would probably do so anyway, or would find another way of financing their children’s education, rather than by lower-income families who are in greater need of assistance (Milligan 2002).

In 1998, the Government of Canada created the Canada Education Savings Grant (CESG) in an attempt to encourage more Canadian families to save for their children’s education. Under this plan, the government topped up every dollar contributed to an RESP by donating 20 cents, to a maximum of $400 per year. Data from the most recent Survey of Approaches to Educational Planning indicate that educational savings are expanding quickly (Shipley, Ouellette and Cartwright 2003), although other sources point out that the majority of this program’s money has gone to upper-income families (Milligan 2002; Usher 2004b). Partly in response to this, the 2004 federal budget increased the top-up rate on the first $500 contributed to 40 percent for low-income families and introduced a new Canada Learning Bond (CLB), which will provide every child born into a low-income family (defined, as per National Child Benefit [NCB] guidelines, as a family with an income under $35,000) with a $500 bond, cashable for post-secondary education once the child turns 18. Subsequently, these children will qualify for $100 CLB instalments until age 15 in each year their families are entitled to the NCB supplement. Children born after 2003 who are not eligible for the CLB at birth but become entitled to the NCB supplement in a subsequent year will qualify at that time for a $500 CLB and thereafter be eligible for the annual $100 CLB instalments.

In total, education-related tax expenditures in Canada currently amount to approximately $1.7 billion per year, of which approximately two-thirds comes from Ottawa. In addition, annual CESG expenditures (which come exclusively from the federal government) now total close to $400 million; this is expected to rise by another $100 million once the 2004 budget provisions are enacted.

The Canadian student financial aid system thus provides a substantial amount of support to students and their families in myriad ways. And, especially in the case of loans and grants, much of this money is targeted at those who need it. However, due to the different eligibility criteria, some of this assistance also ends up with students who are not so needy; the other forms of aid — tax credits and some other grants, in particular — are even worse in this respect.

Thus, while this student financial aid system has some very sound elements, increases many Canadians’ access to post-secondary education, and improves the terms under which they are able to study and how they finance that schooling, it also has some major flaws. These include the following.

Canadian governments collectively spend almost 40 percent of all their student financial aid dollars in the form of education-related tax credits, but these tax credits are distributed almost entirely without reference to need. Much of the money goes to students from higher-income families — or their parents (or even grandparents) — who do not really need the assistance to ensure their access to post-secondary studies. Meanwhile lower-income families are unable to benefit because they do not have the tax obligations required to take advantage of the benefits or, at best, receive no more assistance than higher-income families.4 Families with incomes above the national median receive roughly 60 percent of all education and tuition tax credits, while in the CESG program, the figure is closer to 70 percent (Usher 2004c ).

In addition, it is likely that many individuals are not fully aware of these credits or their value, and do not receive the benefits until after they (the students or those to whom they pass their credits) receive their tax refunds — typically, after the school year to which the benefits are meant to apply. Spending on tax credits would thus be better directed toward programs that are specifically designed to help students from low-income families who really need the assistance.

Other forms of Canadian student assistance — grants, loans, loan remissions, and so on — are designed to be need-based. In theory, this means that more assistance will flow to students from lower-income backgrounds. In practice, however, because the assistance provided to independent students is actually greater in total dollar terms than the amount that goes to individuals who depend on their parents, and because students are too often considered independent of their parents at the age of 22, much of Canada’s need-based assistance goes to students from wealthier families.

Across the country, students are considered independent if they are (or have been) married, have a child (in Quebec, 20 weeks or more into a pregnancy), have been available to the labour force on a full-time basis for two years, or have been out of secondary school for more than four years (in Ontario, five years; in Quebec, 90 credits or more completed at the undergraduate level). The last criterion is especially problematic because it makes individuals who have taken their time getting into or through post-secondary programs (including those who choose to travel or take a bit of time off from school) independent toward the end of their studies. As a result, roughly 60 percent of the CSL population is independent, even though best estimates suggest that independent students form only 30 percent of the Canadian post-secondary population (Usher 2004a).

There is no question that treating students as independent and making them eligible for financial assistance without regard to their family’s income is appropriate in some cases. But the current rules and practices are not restrictive enough; they need to be reformed so that at least some of the money now spent on students from higher-income families who manage to qualify as independents is retargeted at young people from lower-income families who are in greater need of the help. Doing so would almost certainly have a positive impact on access.

As discussed earlier, in most of the country single students are currently eligible for a maximum of $275 per week in direct assistance, a figure that has not changed since 1994. Spread over a university-standard 34-week period of study, this translates into $9,350 per year. Just on a priori grounds, if those limits were appropriate in 1994 — which was probably the case, as they were based on the best evidence available at that time — they cannot be so today, now that costs, especially tuition, have risen significantly.

Furthermore, although calculations vary, empirical studies indicate that even by conservative estimates at least 25 percent of all students have needs in excess of the lending limits established by the aid system itself (Hemingway 2003a,b). Yet regardless of assessed need (which takes into account the expected contributions of students themselves), students cannot receive more than $275 per week. So we have the rather bizarre spectacle of a need-based program telling students that they need a certain amount of money but not giving them what they need. Fred Hemingway makes a compelling case that student assistance maxima are currently inadequate and should be increased to approximately $350 per week, although even this may not be enough (2003a,b).

Finally, students are voting with their feet — or at least their bank accounts and borrowing patterns — and appear to have dramatically increased their dependency on private loans in recent years (Junor and Usher 2002). It is possible that this represents frivolous or unnecessary borrowing to support lifestyle spending, but it seems more likely that students are borrowing simply because they need the money to pay basic schooling expenses when assistance packages are inadequate.

We thus believe that the student financial aid system should increase the maximum amounts available to whatever is required to meet the students’ needs. After all, if the system determines that students need a certain amount of money in order to acquire a post-secondary education, then the student financial aid system should make this amount available.

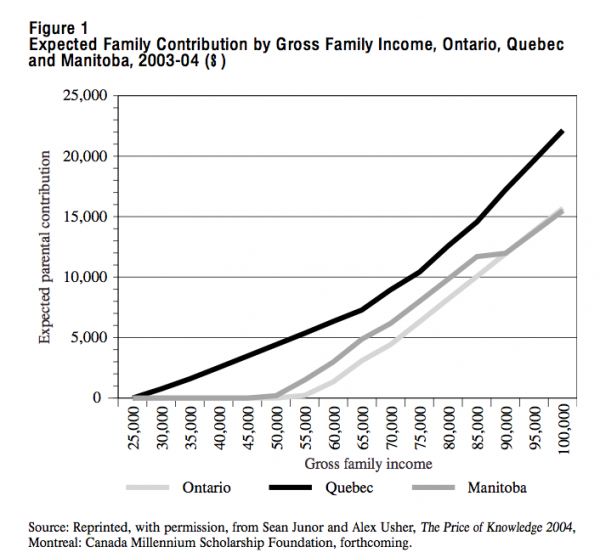

For dependent students whose parents’ resources are taken into consideration, there is an income threshold below which no contributions are required and the student is eligible for the full amount of assistance available. This threshold varies by province, according to cost of living and tax rates, but effectively the formula exempts families below about the fortieth percentile of family income from making any contributions whatsoever. However, by about the sixty-fifth percentile of family income, parents are expected to contribute 75 percent of marginal after-tax income (if we assume the support of their children comes out of current income), which is extraordinarily steep. Above the seventy-fifth percentile, parental contributions are expected to be so high that virtually no one is eligible for student assistance. At face value, these schedules seem unreasonable. Figure 1 shows expected parental contributions in the Canada Student Loans program and Quebec’s Aide financière aux études.

Furthermore, data on actual parental contributions strongly affirm that the current formulas are wrong on two counts (Ekos Research 2003). First, they vastly overestimate the contributions actually made by parents from the upper two income quartiles. Second, they underestimate the amount of money contributed by families with income just short of the median. As a result, the latter might receive more assistance than they need, while the former definitely receive less (Hemingway 2003a,b). Talks with institutions’ student financial award officers provide further ad hoc evidence of these inequities.

We thus believe that the student financial aid system needs to be recalibrated with respect to parental contributions in order to be fairer and more realistic.

As explained earlier, the system simply assumes that parents give their children what they should be receiving according to established contribution formulas. There are, however, many parents who do not give their children as much as expected — or who provide no support at all — and this will always be the case, even if parental contributions are recalculated along the lines we suggest. While most Canadian student loan programs do have an appeal system that allows students whose parents are not making the expected contributions to obtain at least some public support, this system is completely unadvertised and hence seldom used.

In most countries, especially those in which tuition fees are high, there is some form of loan system that addresses this precise problem. We think that Canada should adopt such a system.

Canadian governments spend about a billion dollars on nonrepayable assistance annually, but nearly half of this goes to students after they have completed a year of study, or even an entire program, through what is known as “loan remission.” With this form of assistance, the grant is received not by the student, but by the student’s financial institution as a paydown of a portion of an existing student debt. In Alberta, Newfoundland and Quebec, the loan remission occurs at the end of the program of study; it is based on total accumulated borrowing and is dependent upon timely completion of studies.5 In Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Prince Edward Island, it occurs at the end of a given year of study and is based on the amount borrowed that year.

Loan remission is an odd system — and Canada’s reliance on it as a means to deliver grants is unique in the world of student assistance. First, because these programs only pay down existing loans without putting additional money into the hands of students, to the degree students actually need more money to pay their schooling and associated living costs, they provide no benefit. Second, by denying students the money up front, the system of remitting loans after they have been taken out according to certain conditions creates uncertainty about the total assistance packages students will receive; this is especially so in terms of the loans-versus-grants mix, which is an important consideration for many, particularly those from lower-income families. Finally, loan remission programs deliver debt relief with no regard for an individual’s actual debt burdens, as measured by debt-to-income ratios in the payback period. In this respect, they are very different from interest-relief and debt-relief-in-repayment programs, which explicitly take post-graduation income into account.

We thus see a need to eliminate existing debt-remission programs and spend more money on upfront grants (or loans), which provide students with the money they need without creating uncertainty as to how much of it is loan and how much is grant. More money should also be spent on debt relief in repayment based on actual debt burdens (that is, on a comparison of the payments required and the individual’s income) rather than simply on the amount borrowed in a given year or even that accumulated over the student’s entire course of study (Queen’s University, Institute of Intergovernmental Relations 2003).

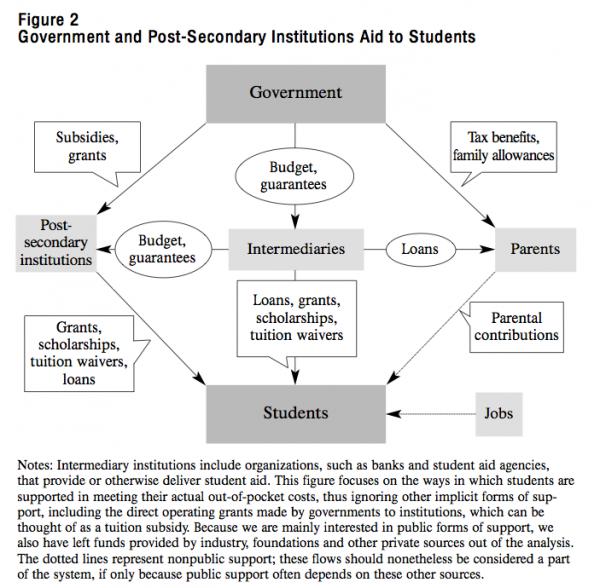

International practice shows a wide array of ways in which governments and higher-education institutions help students meet their schooling costs, including tuition fees, other mandatory charges, study materials, living expenses, and room and board (Vossensteyn 2003b). Figure 2 presents an overview of these approaches.

Of course, no single country has a system that includes all these forms of aid. The precise combination of programs depends on many factors, including each country’s conception of who is primarily responsible for the costs of an individual’s schooling — student, parents, government or a combination of these — which are in turn determined by the country’s ideologies, traditions, political compromises, and budgetary constraints (Vossensteyn 2003a). Here we identify a few broad models that allow us to categorize systems of student support and tuition policies in different countries and the groups of students who generally benefit from each system.

In the student-centred model, students are regarded as having primary responsibility for the costs of their studies. As such, they often face relatively high tuition fees. This implies that public funds to higher-education institutions should not fully cover instruction costs and that financial support is focused on students, not their families (although family contributions are taken into account). Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Japan and the United States provide examples of this approach (ICHEFAP 2003).

In these countries, students are charged considerable tuition fees (sometimes at differential levels by program and institution), while grants, scholarships and loans are primarily awarded to students on a means-tested basis, thus targeting support at students from low-income families and those who are otherwise needy. This approach reflects the (often implicit) expectation that parents will help their children according to their financial capacity, with parental contributions in some countries facilitated through programs such as tax credits and, in the case of the US, a parental loan program.

To what extent do students from low-through higher-income backgrounds benefit from these government transfers? The targeting is ostensibly at lower-income (and thus higher-need) families, but it does not always work this way in practice. One problem is that in countries where tax credits figure importantly (for example, Australia, New Zealand and the UK), families with high incomes have the best opportunities to reduce their taxable income through those credits. Having higher costs can also increase the amount of support, and in many cases this is again related to family income; these costs would derive from being enrolled in more expensive programs or at more expensive institutions, living away from the parental home or being considered independent from one’s parents. These factors are particularly relevant to the Canadian system (as mentioned earlier) and that of the US.

A particularly interesting example of the student-centred model is found in Australia (Dobson 2003). In 1989, tuition fees were reintroduced through the so-called Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS). The flat-rate tuition fee, representing approximately one-quarter of the average instruction cost, has evolved into three different tariff bands, reflecting cost differences between programs and differences in expected future earnings.

Students can pay their tuition up front with a 25 percent reduction or defer payments until after graduation via income-contingent repayments collected through the tax authorities. Because HECS debt has a zero rate of real interest (with only an annual correction for inflation), all students choosing this option are indirectly subsidized (although the absence of the 25 percent reduction can be considered a substitute for interest fees). Those with low incomes after graduation benefit the most from this interest subsidy because they make lower annual payments and have extended (interest-free) repayment periods. A separate system of support for living costs comes from the Youth Allowance program, which provides nonrepayable grants based on parental income and targeted at low-income students, although some funds do leak through the income-testing system to arrive in the hands of students from higher-income families. In addition, certain ethnic groups benefit from more specific scholarship programs.

The UK system — at least before a set of reforms being instituted at the time of writing — was much like that of Australia. The major difference was that student support for living costs came almost entirely in the form of student loans, with only a limited number of hardship scholarships. And since loans could be taken up by all students, including those from higher-income families, the benefits from the interest-subsidy of student loans was enjoyed widely. Students from higher-income families had to pay their tuition fees themselves, while those from low-and middle-income families could get all or part of their tuition waived. Higher-education institutions delivered small amounts of additional assistance to students remaining in financial need.

But in the spring of 2004, the British Parliament passed a bill that will lead to some important changes in tuition and student support. As of September 2004, grants will be reintroduced for full-time students from lower-income households up to an amount of £1,000 per year (approximately C$2,500). In 2005, the repayment threshold for student loans (below which no payments are required in that year) will be increased from £10,000 to £15,000 (C$37,000) per year. The more important changes will, however, occur in September 2006.

From then on, universities will be able to increase tuition fees above the standard rate of £1,150 to a maximum of £3,000 (C$7,400) per year. As compensation, the grants for lower-income students will be raised to a maximum of £2,700 (C$6,600) per year. Universities that want to charge the additional tuition fees must sign an agreement in which they promise to use part of their additional revenues to, for example, offer scholarships for disadvantaged students or actively recruit students from lower-income families. Finally, the maximum amount students can borrow will be increased, while any unpaid debt remaining after 25 years of repayment will be cancelled (Department for Education and Skills 2003).

These changes to a large extent reflect what has been argued for many years by Nicholas Barr of the London School of Economics. In his view, equity and access can be promoted only through differential tuition fees and, predominantly, loans (over grants) that have to be repaid when students (graduates) experience the financial benefits of higher education (Barr 2004). In many ways, the UK system has, with its increased role for student loans, mixed with targeted grants and generous assistance in repayment through its income-contingent element, moved in a similar direction to the new architecture we propose for Canada.

In the parent-centred model, parents are morally, and in some cases legally, responsible for maintaining their children during their post-secondary studies, while there are generally no, or only very low, tuition fees. As a result, student grants and loans are available to relatively few students (generally from 15 to 35 percent), and the amounts awarded tend to be small (Vossensteyn 1999). In contrast, parents are substantially subsidized in meeting their maintenance obligations to their children, generally receiving family allowances and/or tax benefits to help them do so. Family allowances typically vary according to family size and go to families from all income categories without a means test. Tax benefits, typically in the form of tax deductions, generally provide more benefits for parents with higher incomes (and hence higher tax rates) than lower-income families in the lower income/tax brackets. Support is thus less need-based than it is with other systems of support. Such systems can be found in a number of Western European countries, including Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Spain (ICHEFAP 2003).

Because it is assumed that parents will make up the difference between the expenses of students and what they get through direct and indirect support, it is usually difficult to say whether total support is sufficient to meet students’ costs. However, there is considerable evidence that not all parents make the contributions they are expected to make, and that students spend considerably more than they receive through the various forms of public support combined with parental contributions; they also tend to take on part-time jobs (Vossensteyn 1999; 2003a).

Systems in which students are regarded as fully independent from their families are typically found in countries with the most advanced social welfare systems, including Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden (Vossensteyn 2003a). In these countries, students do not have to make tuition payments, meaning that governments pay all instruction costs. At the same time, these countries have relatively flat wage systems in which higher-education graduates do not earn much more than secondary-education graduates.

In addition, public support for students fully covers their living expenses, regardless of whether they live with their parents or away from home. From 40 to 60 percent of the total support received by the student is provided through student loans; the rest comes in the form of grants. In theory, grants are fairly evenly available across socio-economic backgrounds. In practice, however, an increasing proportion of students receive contributions from their parents or take part-time jobs to avoid incurring debt, while lower-income students lacking family resources remain more dependent on student loans and jobs.

A final approach is where tuition and student support policies reflect a compromise between making students financially independent and having parents share the costs, as in the Netherlands. All full-time students are eligible for basic study grants, which vary in generosity according to whether they live with their parents or away from home. In addition, about 30 percent of all students are eligible for supplementary grants based on a parental income test; the parents of students who do not get a (full) supplementary grant of this type are expected to make up the difference. Students can also take out loans, and those independent from their parents are allowed to take up extra loans for the amount their parents are expected to contribute; this option represents a form of protection against parents who do not support their children to that degree. All in all, the three parts (basic grant, supplementary grant/parental contribution and voluntary loans) each comprise about a third of students’ normative budgets. In practice, however, students have substantially higher expenditure patterns, and as a result they are heavily involved in part-time work, which allows them to maintain a higher standard of living and avoid taking out student loans.

This brief survey has demonstrated the different ways in which governments provide financial assistance to students and otherwise help them pay for post-secondary education. These approaches result in substantial differences in how various groups of students are assisted.

Especially in countries where students are regarded as being financially independent or where support is principally channelled through parents, spending is distributed relatively evenly among individuals from different socio-economic groups. Student financial assistance is meant to open up opportunities for underrepresented groups, but the only spending that specifically addresses this objective comes from supplementary programs that target the relevant low-income and minority students. In contrast, systems that focus on the students themselves are generally the most successful in helping such disadvantaged groups. With such approaches, however, there is obviously no guarantee that the assistance will be adequate or improve access to post-secondary education for the targeted groups to the degree desired or intended.

This brings us to the issue that different models of student financing have different price tags for society. Approaches that, directly or through families, provide public subsidies to all students tend to carry higher public costs, because students from relatively affluent backgrounds also benefit. More targeted programs can, in contrast, deliver greater amounts of assistance to those most in need, but they may be more complicated to implement or go against certain societal values related to government spending and support for post-secondary education in general. We return to these issues in the discussion below of our proposed new architecture for Canada.

The Canadian system, for the most part, falls into the student-centred model. As we have just seen, the primary characteristic of this system is that students pay considerable tuition fees and are the prime unit for measuring financial need and receiving assistance. Yet the Canadian system also uses certain aspects of the parent-centred model, and it has been moving increasingly in this direction of late with the increased spending on tax credits and savings grants from which parents benefit.

That said, a number of specific aspects of the Canadian system stand out from a comparative perspective. First, Canada has relatively forgiving criteria when it comes to treating students as independent and thus eligible for increased amounts of government aid. In most countries, a student is not considered independent until age 24 or until he or she has completed a first degree program. This stands in contrast to the Canadian rules described earlier (Quebec’s independence criteria are closer to the international norm). As a result, an unusually large proportion of Canadian loans and grants go to moderately older under-graduate students who meet the independence criteria.

Second, the combination of tuition differences (varying across programs as well as provinces of residence) and a need-based student aid system means that students in more expensive programs — including high-cost professional programs — tend to receive greater amounts of aid than others.

Third, students must take loans before they can receive grants. In most countries, the criteria for loans and grants are separate, which makes it quite possible to receive either or both. In the United States, for example, loans are given out on the basis of assessed need, whereas grants are given out on the basis of family income. This aspect of the Canadian system is at least partly due to the fact that it rolls all education-related expenses — including both fees and living costs — into a single financial aid system, whereas most other countries have separate systems for these expenses.

Fourth, the proportion of assistance that comes in the form of tax expenditures is very high compared to other countries.

Finally, Canada has a great variety of agents through which student aid is delivered, including those at the provincial, federal and institutional levels. This multiple-assistance-points approach is similar to the one employed by the United States, the main differences being that Canadian provincial governments are more important than US state governments in the provision of aid, and the role of institutions is weaker in Canada than in the US. Furthermore, and again like the US, Canada delivers aid in a relatively complex mix of loans, grants, tax expenditures and savings instruments. The result of this complexity is a lack of coherence in terms of the aid delivered, and a lack of transparency for prospective students and their parents in terms of the assistance they are entitled to and in terms of the net cost of their education.

Over overall design goal6 is a student financial aid system that ensures that all students have access to the money required to cover the costs of their post-secondary studies but does not impose undue hardship on the students themselves or their families, or lead to excessive debt loads in the post-schooling period. The system should consist of the following elements.

The first element would be the determination of the student’s financial aid package. This would begin with the establishment of the student’s schooling-related costs, including tuition, and other fees, equipment, supplies and living expenses. These calculations would be based on actual expenditures (for example, tuition fees) or reasonable estimates (for example, living expenses that cover the student’s basic needs), much as is the case in the existing loan system. The established formulas should be easily understood and simple to follow in order to be fair and to keep application and administration costs down, but they should also be flexible enough to cover students in varying circumstances. In the previous section, we mentioned that schooling and living costs are treated separately in many countries, whereas in Canada they are added together in order to assess the student’s overall need and arrive at a single aid package. We follow that lead here.

Next, similar types of formulas would be used for arriving at what students and their parents are expected to contribute toward these costs — again, much like the current system in structure, but with the sorts of adjustments suggested earlier in order to make the formulas more reasonable and realistic. We would also simplify these formulas in order to make them — and the resulting aid calculations — more transparent and user-friendly and less intimidating to students who want to know where they stand in terms of the assistance to which they are entitled.

These first elements would be similar to those in the existing system of loans and grants. A more radical difference is that the resulting difference between costs and resources available would be declared the student’s financial need, and this full amount would then comprise the student’s financial aid package.

The composition of the aid package would then be determined, in particular its balance between loans and grants. We propose that the first, say, $5,000 (per year) of assistance be given in the form of a student loan. This loan-up-front approach would keep incentives right for the most critical first dollars of aid (higher education is an expensive undertaking leading to substantial expected private benefits); it would deliver this first portion of aid in a cost-effective manner (a government dollar spent on loans goes much further than a dollar spent on grants, because the money is effectively recycled as it is paid back); and it would generally limit borrowing to well-defined, reasonable amounts, thus addressing an important element of the “debt aversion” issue.7

This loan-first rather than, say, grant-first approach would also be consistent with the existing Canadian system, and thus, presumably, would conform to Canadian values in this regard. The $5,000 amount could, of course, be adjusted in response to public debate. The loans would carry subsidies similar to those that exist in the current student-loan system. The money would, therefore, be interest-free while the individual remained in school, the student would be eligible for assistance during the repayment period (more on this later), and governments would absorb the costs of default in one manner or another (as they have done over the years, as was discussed earlier).

The balance of the aid would be given in the form of a (nonrepayable) grant. This more generous — and expensive — form of assistance would thus be reserved for those who have greater overall need. It would also deliver a price subsidy (the fact that the money does not have to be repaid effectively reduces the cost of the schooling) where it is likely to be most effective in improving access — to individuals from lower-income families.

One implication of this system is that individuals with greater expenses, including those related to being in a more costly program or going away to school, will tend to receive more assistance (and more grants), than others, and these decisions (and amounts) may be related to family background. In particular, young people from higher-income families (among those families with incomes low enough to be eligible for aid) may receive more aid than others, and in this sense the system we propose may have a regressive element. But we believe that the proposed approach is the best solution for ensuring that the aid package is complete, and that it opens up opportunities for students from lower-income families, in particular, as they realize that they are eligible for financial aid to cover the full cost of their studies — including enrolling in more expensive programs, leaving home to go to school, and so on.

All this said, a grant-first system would be an alternative option, and public debate could help resolve this issue. The rest of the package could remain as proposed. The second major element of the new architecture concerns the definition of a “dependent” student. We propose that the classification be extended to cover nearly all students not enrolled in graduate or professional programs. In particular, the current rules permitting students who study part time to take a bit longer to get through their studies because they want to take time off to work or travel to qualify for assistance as “independants”, would be tightened. A useful starting point might be to consider all single students (that is, those not married and without children) age 25 or younger in any program below graduate school or a second-degree professional program as dependent, and have their parents contribute to their schooling costs. This change would reduce the amount of money going to older students from wealthier families and allow more money to be concentrated on students from lower-income families.

The next element of the system would be focused on the problem of dependent students whose parents cannot or will not make the expected contributions. We propose a secondary loan program that would allow students to borrow an additional amount up to the value of their expected parental contribution (with a maximum value equal to their assessed need). In order to discourage excess and frivolous borrowing (for example, by students from higher-income families who do not truly need the money), this additional program — like those in many countries — would not carry the same subsidies as the primary loan system, and interest would accumulate from the time the loan was taken out. This unsubsidized program could also be made available to students unable to make their own expected contributions from their summer employment earnings.

We would also ensure that parents and students alike clearly understand what the expected contributions are, thus putting moral pressure on parents to contribute to their children’s education.

The fourth element concerns the post-schooling period, and addresses the problem of excessive debt loads, even though this should be a limited issue in a context where loans are normally capped at $5,000 per year. We propose generous assistance for those who face large debt burdens relative to their post-schooling incomes, in the form of both shorter-term interest relief, and, for chronic situations, reduction of the principal owed. Such program features reduce the psychological cost of borrowing, even for those who never need to take advantage of the assistance, while obviously providing direct aid to those who do. Both the Canada Student Loans Program and the Quebec system currently have interest-relief programs in place, but these could be enriched (especially the latter, which is considerably less generous than the former). Debt reduction, however, does not currently exist in Quebec, and it exists in little more than name in the rest of Canada.

Since income-tested debt reduction — unlike simple remission — takes borrowers’ long-term income profiles into account, it represents a highly efficient and fair debt-management subsidy, as it delivers assistance where it is most needed in the longer run. We do not offer any specific suggestions for appropriate debt-servicing ratios (these could be determined through stakeholder consultation); we merely note the attractiveness of this type of subsidy on both equity and efficiency grounds and encourage both levels of government to invest more in it rather than in the wasteful loan remission programs that currently consume $1 billion per year.

Alternatively, a full income-contingent repayment (ICR) system could be adopted whereby payments are automatically geared to an individual’s income in the post-schooling period, and no payments are required for those with incomes below a certain minimum level, the money being collected through the tax system. While ICR systems have a long-standing tradition in the student loans literature, a strong argument could be made, in the current Canadian context, for a simple fine tuning and strengthening of the present interest and debt-relief programs (which contain a strong element of income contingency). This would build on existing structures and conventions in a way that similarly adjusts payments to debt burden in an effective manner.8

The final element of the new architecture would be to advertise all elements of this relatively simple, effective and equitable system so that all potential students are aware of the resources available to them and understand that financial barriers need not keep them from pursuing post-secondary studies.

Consider an example. A student decides to enter university, and the total cost of doing so — including both education-related expenses and living expenses — is $15,000 per year. The student may (by the chosen formulas) be expected to contribute $3,000 out of summer earnings and (perhaps) earnings from part-time employment during the school year. If the individual comes from a low-income family deemed unable to contribute to these expenses, the resulting aid package will consist of the full difference between costs and available resources, or $12,000. Of this, $5,000 will come in the form of a loan and $7,000 as a grant. The student will be given the resources to undertake the chosen schooling through what most people would probably consider a generous aid package. At the same time, the student will be making a considerable contribution to those costs (the $3,000 in cash and the $5,000 loan) without accumulating an excessive debt. And if a significant amount of debt does accumulate over the student’s full academic career and that student faces a substantial debt burden relative to his or her post-schooling income, further assistance will come in the form of interest and debt relief.

This new architecture might seem obvious: calculate the student’s need, assess the available resources, deliver the difference as the financial aid package, bundle the aid in a judicious combination of loans and grants, provide an alternative source of loans for those whose parents do not provide the assistance expected of them or who cannot make their own contributions, help those who have unreasonable debt burdens in the payback period and ensure that the system is well advertised and fully transparent. Such a system should meet the basic goal of removing financial barriers to post-secondary education and avoid excessive debt burdens. Furthermore, once in place, the system could be fine-tuned in a relatively easy and transparent manner.

All this said, financial considerations are but one barrier to post-secondary education. Others include individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, and preparation, and these need to be addressed if access to post-secondary education is to be made truly open to all, including those from lower-income families. Efforts should, therefore, extend beyond the student financial aid system to ensure that prospective students and their parents are abundantly aware of the substantial benefits that typically accrue to higher education. It would be equally worthwhile to institute measures to ensure that potential students are sufficiently well prepared to go on to higher studies when the time comes. Other components of a “starting-early” strategy should also be considered (Finnie, Laporte and Lascelles 2003; Looker 2001; Junor and Usher 2002).

In many circumstances, this new system would deliver increased aid to students whom the current system shortchanges because aid limits fall short of the students’ needs or expected parental contributions are too high. There would also be a substitution of grants for loans for some high-need students, thus driving aid costs up further. In addition, a greater number of students would likely qualify for assistance as parental contributions are made more realistic. Finally, we propose increased spending on individuals facing hardship in the post-schooling period because their earnings are not high enough to comfortably cover their debt loads.

Where would the money come from? Principally it could come from reducing current spending on student financial assistance where it is not needed to ensure access or is otherwise spent ineffectively. As mentioned earlier, Canada currently spends over $1.7 billion per year in education-related tax credits (37 percent of all student aid spending), which go to rich and poor alike, with a bias toward the better off, while the delayed nature of the benefits (that is, tax refunds are received only after a given year’s tax form is filed) further diminishes their effectiveness as a form of student aid. These tax credits could be eliminated and the proceeds put into our program.

The same goes for the country’s various education savings programs, which are taken up disproportionately by higher-income families who have the means to put money aside for their children’s future education costs, even as improved aid packages need to be provided to those from lower-income families seeking post-secondary education today.

Further savings would come from eliminating the need for existing debt-remission programs, worth another $430 million per year. These programs would no longer be necessary. The expansion in the up-front grants and assistance in repayment we propose would address the related access issues in a more efficient and effective manner.

Finally, our tightening of the criteria that determine who is an independent student would reduce spending on students from high-income families who benefit from the system because of the current overly generous independent-student provisions.

Eliminating spending on these poorly targeted and relatively ineffective forms of student assistance would thus represent at least a large down payment on the funds required by our new architecture. And while all those currently benefiting from these programs are surely glad to receive the aid, the first goal of the Canadian student financial aid system should be to eliminate financial barriers to higher education for children from lower and middle-income families — which the proposed system would do.

That said, many of those currently receiving the forms of support that would be eliminated in the proposed program — tax credits, debt remission and so on — would receive assistance through the new system, so that what is taken away with one hand would be (at least partially) given back with the other. And, most importantly, those who really need financial support would get it under the new architecture as part of a unified and coherent system that rationally ensures sufficient assistance for all who deserve it, rather than supporting those who do not need it and delivering to the target populations in only a limited, incomplete, and wasteful fashion.

After those basic needs are met — after the financial barriers to post-secondary education are removed for all — extra money could be directed toward providing subsidies to higher-income families for this clearly costly expenditure.

Once properly costed out, the parameters of the new architecture could be adjusted to ensure that it meets specific budget limits. For example, the initial $5,000 loan we propose before grants cut in could be increased, thus providing the aid in a more cost-effective manner. But it could well be that the savings we propose would be more than enough to cover our recommended program; additional funds could then be invested in various kinds of student financial aid (for example, targeted grants for disadvantaged groups) or the funds could be transferred elsewhere.

In many ways, the system we propose would be similar to the one currently in place. And we see this as one of its benefits, in as much as it would be easier to implement than a more radical set of changes. Our new architecture, would, however, also embody a number of key structural changes, as well as some important differences in detail.

First, while the new system would most resemble the current structure of loans and need-based grants, it would represent a single unified and coherent approach that would replace the plethora of existing programs — including tax credits, savings grants and debt remission — effectively doing the job of all these others more simply, thoroughly and efficiently. In its details, the new architecture would have the high assistance limits seen in Quebec, debtlimitation limits similar to those in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and it would use up-front grants in much the same way as British Columbia.

Second, the full difference between costs and resources available would be declared the student’s financial need, and this amount would comprise the individual’s financial aid package. Hence, there would be no unmet need. This stands in contrast to the currently available limited aid packages, which do not necessarily meet the student’s assessed needs.

Third, the full aid package would be delivered up front, in cash, through loans and grants, instead of months or even years after the fact in the form of tax credits and debt remission and other more ambiguous, uncertain and delayed forms of assistance.

Fourth, and more in the way of an important detail than a structural difference, the formulas used to estimate the student’s costs and family contributions would include certain additional expenditures (for example, computers), on the one hand, and fairer and more realistic parental contributions on the other. Parental contributions would begin at lower income levels, and modest, or nominal, contributions would be required from low-income parents (currently none are required). But, more importantly, the required contribution would rise with income more gradually than in the present system. Many middle-class parents would not have to contribute as much, and more families would benefit from the system.

Fifth, the definition of a dependent student would be extended to include those who simply take a little longer to get into or through their studies. Meanwhile, expected parental contributions would be made clearer and provisions to protect students whose parents do not make those contributions or cannot make their own expected contributions would come in the form of a supplementary loan plan. Aid delivered by institutions would, as now, provide additional help to such students, as well as to others who inevitably fall through the cracks of the proposed system (and its appeal procedures).

Sixth, assistance for students facing excessive debt loads would be based on total accumulated debt after leaving school and the individual’s income or ability to service that debt. This approach would resemble an expanded version of current interest and debt-reduction programs. It would also replace all existing debt-remission programs, which are in most cases based on annual borrowing rather than the total accumulated by the time the individual enters repayment, and in no instance take the student’s capacity to pay into account.

In short, the new architecture we propose could be a more effective, more efficient and less wasteful means of delivering financial aid to those students who need it than the current panoply of overlapping yet incomplete programs. Thus it could make post-secondary schooling a more viable option for many Canadians from middle and lower-income families.

One potential set of complications arising from such a unified and coherent plan in the Canadian context stems from the associated set of constitutional and jurisdictional issues and the mosaic of provincial (and territorial) programs currently in place, which reflect the various needs, circumstances and manner of doing things related to student financial aid in different parts of the country. These differences, in turn, stem from the fact that post-secondary education is, constitutionally, a provincial jurisdiction, though the federal government has an established role in the area of student financial assistance, which has included, since 1964, operating the Canada Student Loans Program, various grant programs, and the education-related tax credits and savings grants they provide.

The short and easy answer to such concerns is that once the clear advantages of the unified and coherent student financial aid system proposed here are recognized, it would simply be up to the relevant provincial and federal authorities to make it work. They would owe it to their constituents to do so. And this does not seem an impossible outcome, given the considerable level of federal-provincial cooperation that already exists in the area of student financial assistance. The Canada Student Loans Program, in particular, delivers federal dollars across the country using provincially determined need-assessment procedures and other administrative rules, while coexisting with provincial loan and grant programs that also differ substantially from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

A new program could, therefore, presumably function with some level of provincial diversity rather than a single nationwide set of rules and procedures. There could, for example, be variation in the need-assessment procedures, in the mix of loans and grants, in the amount and type of assistance available for repayment, in the extra aid going to higher-income families, or in any of the other specific program parameters, as long as the basic characteristics of the new architecture were maintained (that is, if it remained a single unified program that fully met students’ needs).

The federal government and each province could thus agree to a specific form of the sort of unified and comprehensive system described earlier and then divide the costs according to a simple formula, such as the 60/40 split that has come to be the standard for student financial assistance in this country.

Unfortunately, this type of arrangement would have its own problems. Provinces might not be equally willing or able to provide financial aid to students. Some might be tempted to push up tuition rates (which they control) or otherwise inflate students’ assessed costs, in order to increase the amount of federal spending on student aid even as they took in the resulting increased tuition revenues. And the federal government might balk at being locked into a cost-sharing arrangement whereby the provinces spent only 40-cent dollars, thus distorting spending incentives.

Still, one can imagine a set of federal-provincial agreements pegged, as required, to a set of reasonably well-defined post-secondary education costs (including tuition fees) that resolved these problems, with each jurisdiction paying its share.9 Ideally, students would see only a single program, thus it would be very clear to them what amount of assistance they were eligible for, and their lives would be easier at each point of contact with the program, including the application procedures, the actual taking out of the loan, and all aspects of repayment.