Political knowledge is a democratic value. It is also an important ingredient in democratic citizenship, influencing public attitudes and opinions and, thus, political behaviour. From existing studies we have learned that political knowledge tends to affect the number of beliefs individuals have, making it easier to decide on issues and to clarify behavioural intentions. But there remains a gaping hole when it comes to comparative, international studies.

For the last decade Henry Milner has been working on developing indicators for comparing levels of political knowledge in mature democracies and linking these to political participation. He has shown that when we compare countries as to the proportion of their citizens with the minimum levels of political knowledge needed to make effective political choices (civic literacy), we find good evidence that the positive relationship between political participation and political knowledge holds for countries as well for individuals.

As voter turnout and other forms of conventional democratic participation have recently declined, especially among young people and quite acutely in Canada, this relationship has become critical. A previous IRPP study by Milner (2005) shows that political knowledge, or the lack of it, was central to this decline. But the lack of cross-national data inhibited drawing clear prescriptions for action – except for the need for comparative survey data on political knowledge.

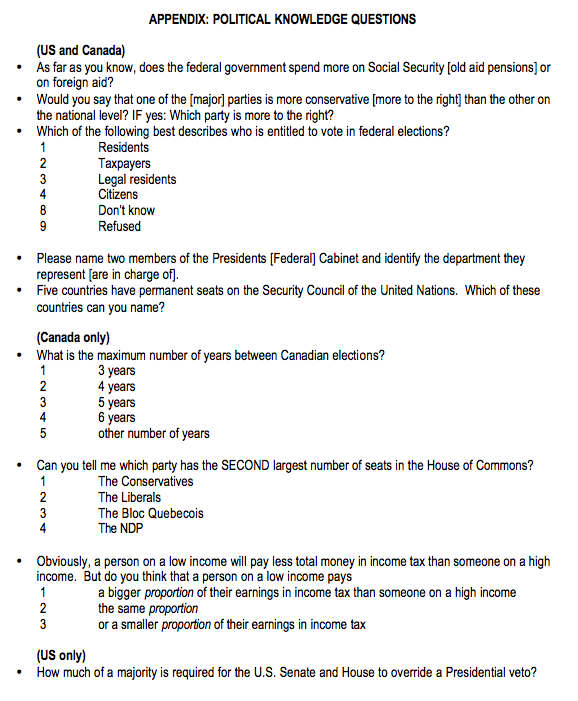

If political knowledge is an important determinant of political participation, we need aggregate indicators to be able to test the effects on political knowledge of various policy and institutional choices. This applies especially to the political participation of young people. Youth political participation levels have declined in recent decades in almost all Western democracies, but the degree varies considerably across nations. Hence the phenomenon is both generational and contextual; that is, it is a consequence of national institutions and policy choices. To disentangle these, the first step is to survey young people in two or more comparable societies using a common set of political knowledge questions. Henry Milner begins to take up this challenge in this paper with an analysis of the results of the initial application of a set of political knowledge questions designed to be used in Canada and the United States. The resulting questionnaires allowed for 8 possible correct political knowledge answers for US respondents, and 10 for Canadians, 7 of which are common to both. It is this combined score out of 7 that serves as the main indicator of political knowledge.

These were included in two recent surveys focusing on young people. One was carried out in the United States in May 2006 with 1,765 respondents, of whom 1,209 were aged 15 to 25. The other was carried out in Canada in September 2006 (and is being reported for the first time here), with 1,354 respondents, of whom 877 were aged 15 to 25. Apart from the political knowledge questions, 60 questions dealt with various forms of unconventional and unconventional political participation, media use, civic education, voluntary association participation, as well as relevant attitudes to political parties, the role of government, and so on.

The starting point of a comparative analysis of political knowledge in Canada – as in other aspects of culture, values and attitudes – is with the United States, given how much this country is affected by American developments. The exceptional opportunity of including common questions related to political knowledge in youth surveys in the two countries was thus one not to be ignored. While Canadian studies of youth political engagement have been much influenced by American findings and priorities, few replicate the actual survey questions and sampling methodology, and none include common political knowledge questions. Beyond providing a rare chance to assess what young Canadians know about politics compared with their American peers, the combined surveys make it possible to ask whether the American approach to tackling low levels of youth turnout is indeed appropriate for Canada.

Young Canadians’ political knowledge is low – only slightly higher than the level of their American counterparts and, therefore, low compared with Europe. This suggests that European nations are better at disseminating the information and skills needed to turn its young people into participating citizens, and raises the question of whether Canadians should look there, rather than to the United States, in seeking to address the issue.

Milner concludes that emulating the stress in the US on involvement in nonpartisan voluntary group activities as we seem to be doing could prove less effective than an alternative approach taken by high civic literacy countries in Europe, whereby political knowledge is regarded as the basis of meaningful political participation. It stresses measures that raise the level of political knowledge by making the environment of young people rich in political information, targeting especially those lacking the resources to gain access to it on their own. It looks to government programs in education, media support, political party financing, information dissemination, and so on, and, unlike the US, does not try to isolate civic education from partisan politics.

For the past decade I have been working on developing indicators for comparing levels of political knowledge in mature democracies and linking these to political participation. Political knowledge is a vital aspect of democratic citizenship. We know there is a strong relationship between levels of political knowledge and consistency between policy preferences and vote choice (Andersen et al 2001). Indeed, the accumulating evidence suggests a clear link between political knowledge and the quality of democratic representation and accountability of office holders.2 As far as participation is concerned, not only are better informed individuals more likely to vote and otherwise take part in politics,3 but the positive relationship between political knowledge and voter turnout is reproduced cross-nationally. Put otherwise, when we compare countries as to civic literacy, that is, the proportion of their citizens with the minimum levels of political knowledge needed to make effective political choices, we find a close positive relationship between levels of civic literacy and rates of political participation (Milner 2002).

This relationship is becoming critical, since voter turnout and other forms of conventional democratic participation have declined in recent years, especially in Canada. Moreover, as the 2000 Canadian Election Study (CES) reported, most of the decline in turnout (from 75 percent in 1988 to 61 percent 2000) was attributable to generational replacement (Blais et al 2002:49). A study carried out by Elections Canada found that 38.7 percent of eligible first-time electors voted in 2004. In contrast, turnout for those over 30 was close to 70 percent.4

In a recent paper I addressed the phenomenon of declining turnout among young Canadians (Milner 2005).5 I concluded that political knowledge, or the lack of it, was an important factor in this decline.6 With youth political participation levels declining in recent decades in almost all western democracies -though the degree varies considerably across nations (Franklin 2004) – there is no lack of parallel survey data from other countries indicating a clear relationship between declining turnout by the young and declining political knowledge and attentiveness on their part.7 But, with one partial exception, the questions and methodology differ in these various surveys, inhibiting our capacity to draw clear prescriptions for addressing low political knowledge among young people.

The exception is the 2002 National Geographic-Roper Global Geographic Literacy Survey, which assessed the knowledge of political geography of 3,250 young adults in nine advanced industrial democracies plus Mexico. Among the nine, the United States is at the bottom, with an average of 23 correct answers of a possible 56, followed by Canada at 27 and the UK at 28. Sweden led -with 40 – and Germany and Italy followed with 38. As expected, as a rule, countries with higher turnout performed better. But the study does not allow us to link the differences in knowledge levels with other factors that may explain these differences. Moreover, familiarity with international political geography is at best an indirect indicator of one’s level of the knowledge needed to participate effectively in national politics.

The absence of such data, though understandable given the difficulty of arriving at questions about national politics that are applicable cross-nationally,8 is unfortunate if we wish to understand and address the low level of political knowledge. It is especially the case here for, despite slight improvements in recent years, Canada, from what we know from the limited comparative data, ranks near the bottom in youth turnout among advanced democracies, along with the UK and the US (Milner 2005). As we shall see below, there has been much discussion in the US as to how to address the issue of youth participation. And, as in other areas, the Canadian approach has been much influenced by American developments.

But how appropriate for Canada is the American approach? To adequately answer this question we need comparable data; and such data has been in short supply. This paper begins to overcome this deficiency. It is based on data from two surveys, at the core of which is a set of political knowledge questions designed to be used cross-nationally. Both surveys focused on young people: one was carried out in the United States, the other in Canada. The originality of this study lies in the fact that respondents in both countries responded to the same questions, both those testing political knowledge, and those getting at the causes or consequences of low levels of political knowledge. In thus asking whether the American approach to preparing young people for citizenship is appropriate for Canada, we are able to take into account the effects of differences in institutions plus those of intervening variables such as the media use, voluntary group involvement and civic education, as well as differences in relevant attitudes towards politics.

It is generally accepted that compared to previous generations arriving at voting age, young American citizens are today less likely to see voting as a civic duty and to pay attention to politics.9 A useful comprehensive portrayal of the situation is provided by Wattenberg (2007). Nevertheless, there is an important difference among American observers as to the appropriate means of addressing – or indeed comprehending – the situation. Wattenberg’s pessimistic assessment is challenged notably by his colleague at the University of California, Irvine, Russell Dalton (2006), who suggests that critics have missed the “good news” about the engaged citizenship of young Americans. Such engaged citizenship takes the form of “repertoires” of attitudes associated, for example, with “forming one’s opinion,” “supporting the worse off,” “understanding others,” and “being active in voluntary associations.” Clearly, an approach that takes such attitudes as indicators (as opposed to one that emphasizes attentiveness to politics – as does Wattenberg and as do we) is likely to produce a more positive portrait of youth political participation, since, in effect, it costlessly invites respondents to place themselves in a positive light.

Moreover, there is an institutional dimension to taking this approach that makes it especially problematic for comparative analysis. American observers tend to place great emphasis on repertoires associated with involvement in a voluntary or service organization as an indicator of political engagment. The problem is that in the United States, more than in other comparable countries, including Canada,10 there are powerful institutionalized incentives in operation.11 In many American schools and colleges such activity is obligatory rather than voluntary. Such institutional incentives must be taken into account in comparative analyses of survey data about asking young people about participation in such activities – just as comparative assessments of voter turnout take compulsory voting into account.12

For these reasons, our study comparing young people in the US and Canada treats involvement in voluntary associations not as an indicator of political participation but as a possible predictor of both conventional and unconventional forms of such participation in comparison with media use, civic education, and party identification. Thus, it allows us to test for differences in the relative effects of voluntary group participation on informed political participation among young people in the two countries, and whether other factors – and hence strategies for confronting the problem – are more salient in Canada than in the US. The term informed political participation is chosen deliberately to reflect our stress on political participation as an expression of a knowledgeable political choice, rather than a response to institutionalized incentives. From this perspective, making voting compulsory, with a threat of fines, is of little value if it does nothing other than bring uninformed citizens to the ballot box.13

In operationalizing informed political participation, we here emphasize the informed (political knowledge) aspect rather than the participation (reported voting) aspect, because of the subjectivity and cultureboundedness of the latter. We know that respondents over-report voting to place themselves in a positive light; the subjective element is even more salient among the many respondents to the surveys aged 15 to 18+, for whom the question is one of intent to vote in the future rather than experience of doing so. As Hooghe et al (2006:19) report from a recent study of 14-15 year olds in 27 countries “when questioned about the likelihood of future voting behaviour … the expressed willingness to vote … does not seem to be inspired politically, but rather reflects a more general attitude, in which adolescents simply echo the kind of values that are being portrayed as socially desirable by either the parents or the school environment.” In contrast, an incentive to give the desired correct answer to a political knowledge question has no effect, since it doesn’t help the respondent who lacks the requisite knowledge. Nevertheless, as the literature reveals, and as we shall see in the survey data here assembled, there is a very close statistical correspondence between political knowledge and the various forms of political participation – including reported turnout.

Since we ask respondents in both countries the same questions, we are able to control for relevant background characteristics such as age, gender, and educational attainment, and focus on the factors associated with informed political participation that distinguish Americans and Canadians, young and older. In addressing strategies for encouraging informed political participation, we ask if emulating the stress in the United States on involvement in nonpartisan voluntary associations is likely to be effective in Canada’s different institutional environment, or if we should look more to alternate approaches associated with the high civic literacy countries in Europe. These give greater importance to measures that raise the level of political knowledge, looking to government programs in education, media support, political party financing, information dissemination, etc. This interrogation is given concrete form at the end of the paper in the discussion of alternative approaches to civic education. Today, more than ever, the school is the key arena for promoting the informed political participation of future citizens.

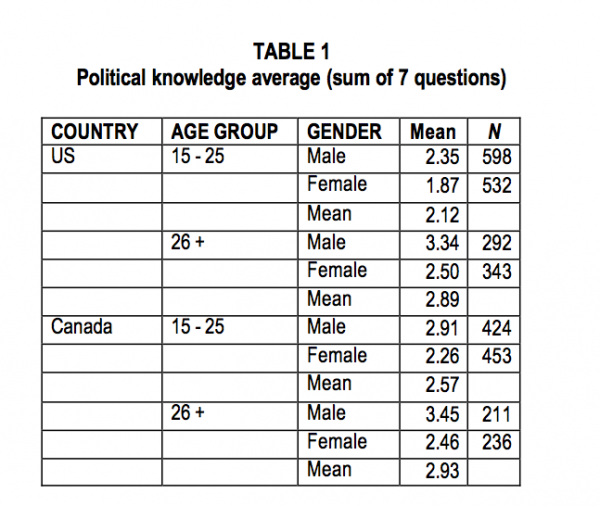

The data analyzed in this paper is derived from two surveys conducted in 2006, one in the United States and the other in Canada, in which there were roughly 60 common questions. The first was undertaken by CIRCLE (the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, at the University of Maryland). Its Civic and Political Health Survey updated a previous youth survey (Keeter et al 2002). Telephone interviews were conducted in May 2006 with a nationally representative sample of 1,765 people14 living in the continental United States, of which 1,209 were aged 15 to 25.15 The was conducted using similar methodology16 in September 2006 with 877 respondents 15 to 25 and 477 aged 26 and over. Just over one-third (451) of the interviews were conducted in French.17 (The breakdown of the entire sample by country, age group and gender can be found in Table 1 below.)

The earlier US survey posed 3 political knowledge questions. For this, second, round, five questions were added. (These were selected from from among those I had proposed, designed to be suitable also for Canada and to correspond as closely as possible with the 6 that had been slated for the second round of the European Social Survey (ESS) in 2004.18 The resulting questionnaires allowed for 8 possible correct political knowledge answers for American respondents, and 10 for Canadians, 7 of which are common to both. It is this combined score out of 7 that serves as our main indicator of political knowledge. (The list of questions can be found in the appendix.)

We begin by comparing young people in Canada and the US with each other and with those over 25 years in age in each country. While the Canadian data is here presented for the first time, CIRCLE has published an initial analysis of the US data. The analysis points to the low level of political knowledge, but attributes the low reported turnout of the respondents primarily to cynicism, “a plurality says that the government is ‘almost always wasteful and inefficient’ … a big drop in confidence since 2002” (Lopez et al, 2006: 3-4). Yet more young Americans voted in 2006 than in 2002 and, indeed, than in all elections since 1992.19 I contend that the key explanation lies elsewhere in the data: that most do not vote is linked to that the fact that they do not have the information needed to cast an informed choice, despite more than two-thirds of respondents claiming to follow what is going on in government and public affairs at least some of the time.

The figures in Table 1 tell the story. Political knowledge is poor, especially among young people. Out of a possible score of 7, the means for correct answers are 2.12 for young Americans and 2.89 for those 26 and over. Canadian young people’s scores are a little better: 2.57 mean correct answers, compared with 2.93 for those 26 and over. The smaller age gap in Canada than the US, as we shall see later, is largely due to generational developments among Quebecers.

When we break the results down by question, the most glaring contrast is on international matters: 55 percent of young Americans are unable to name one permanent member country of the UN Security Council (i.e., including the US), compared with only 30 percent of young Canadians. But there is no lack of political ignorance on domestic matters. Fifty-six percent of young Americans are unable to identify citizens as the category of people having the right to vote (compared with 43 percent in Canada.) Equally unnerving is a similar inability of young Americans to name even one cabinet secretary (55 percent) and to identify the party that is more conservative (60 percent). (Canadian numbers are similarly low on these questions, but circumstances made them harder to answer. The Canadian government had been in power for only eight months when the survey was conducted. Hence there were no equivalents of Donald Rumsfeld and Condoleezza Rice in public view. Moreover, since the new governing party is Conservative, the formulation used ended up being more difficult for Canadians, i.e., “which party is more to the right?” This latter figure is especially revealing, since no expression is used more frequently and consistently to characterize the Republican Party than the word conservative. The 60 percent of 15-25year-old Americans, and 50 percent of those over 25 who are unable to make this association are effectively off the political map. The correspondence with turnout percentages is surely not a pure coincidence.20

As the literature leads us to expect (e.g. Gronlund 2003), Table 1 confirms that older males are the most politically knowledgeable. While males are politically more knowledgeable the females in both age groups and both countries (see Thomas and Young 2006), the difference is lower among those under 25. This is not, we should add, because young women are more knowledgeable than their elders, but because young men are significantly less knowledgeable than theirs.

In Tables 3, 4 and 5, which set out these relationships, a consistent approach is taken. The dependent (predicted) variable is political knowledge, i.e., the mean of correct answers, and the analysis explores the link to specific expressions of these different types of predictors (“independent” variables). Since the dependent variable is interval (0-7, or 0-10) rather than dichotomous (either-or), the most appropriate statistical measure of that relationship is multiple linear regression. Apart from the traditional statistical measure of that relationship, the beta coefficient, the tables provide the T score, now a commonly used expression of that relationship. The higher the T score, the greater the confidence of statistical significance. (A significance level of below 01 means that we can be 99 percent confident that the relationship between the independent and dependent variable is not the product of chance.)

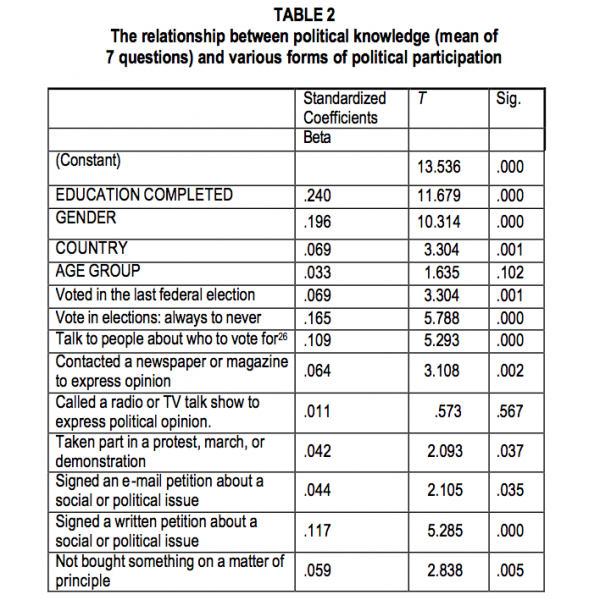

Before looking at the predictors of political knowledge, it is useful to see if our results confirm findings in the literature that political knowledge correlates not only with voting but also with other forms of political engagement.21 Here political knowledge is the independent variable, while the various forms of political participation surveyed, both conventional (vote, discuss politics, display poster, contact media to express an opinion), and unconventional (protest, petition, boycott, etc.), are dependent variables in a multiple linear regression. As shown in Table 2,22 with the exception of calling a radio or TV station to express an opinion, more politically knowledgeable people are significantly more likely to engage in the various forms of conventional and unconventional political participation,23 though the relationship is stronger for the more conventional forms, especially voting regularly. We can see, moreover, as reoccurs consistently throughout the study, that whether the respondent is male or female, American or Canadian, younger or older, or better or worse educated usually also has an important effect, but one that does not wash out the overall relationship.24

Having established that among the respondents to the two surveys those more informed about politics are those who can be expected to participate more frequently in the various forms of political life,25 we can now turn to the various factors that contribute to their being more informed. In the following tables in which the dependent (predicted) variable is the mean of correct answers, the analysis explores the link to predictors of informed political participation identified in the literature. The stronger the relationship, the higher the T score (in absolute terms, (i.e., it can be expressed positively or negatively). While this allows us to compare the effect of different predictors, we are especially interested in those relationships found to be significant (i.e., for which the significance is below .01, so we can be 99 percent confident that the relationship between the independent and dependent variable is not a product of chance).

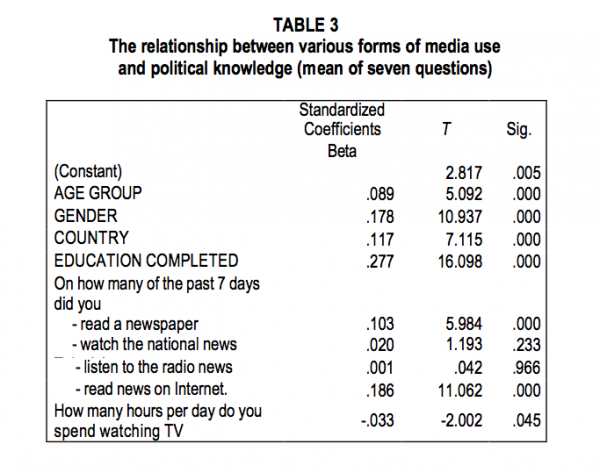

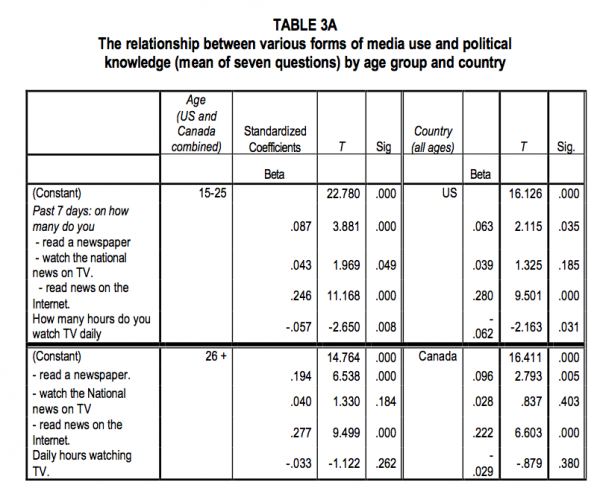

The first set of variables that predict informed political participation to be explored here are related to media use. It is well established that newspaper reading and television news watching are positively related to political knowledge and political participation.27 The regression data for both countries and age groups combined set out in Table 3 show that newspaper reading and, even more, reading news on the Internet, clearly affect political knowledge. The effect of television is more ambiguous. The overall effect of TV watching is negative, while the effect of watching TV news is positive, but relatively weak). Radio listening has no effect. To further explore the relationship, the regression with those media-consumption variables found to be significant in Table 3 are split by country and age group in Table 3A. Reading news on the Internet turns out to have the strongest correlation with political knowledge in both countries – and not only for the young.28 This is apparently a new development. Newspaper reading remains significant, though somewhat more weakly among Americans; while it is among Americans and younger respondents that watching TV for fewer hours has a significant positive effect on political knowledge.

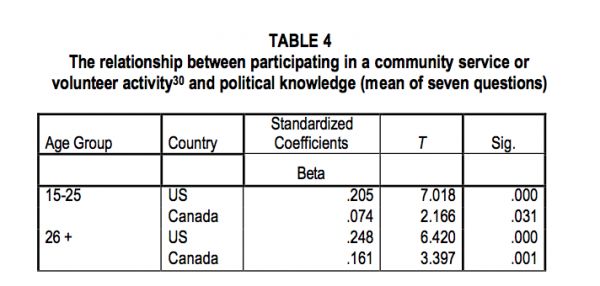

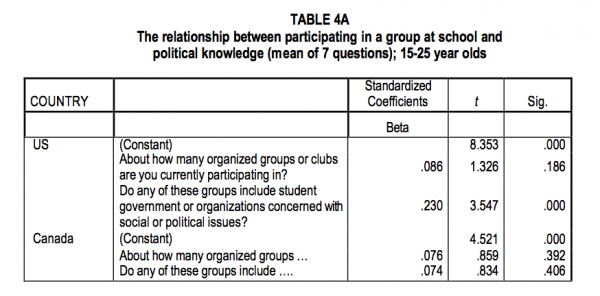

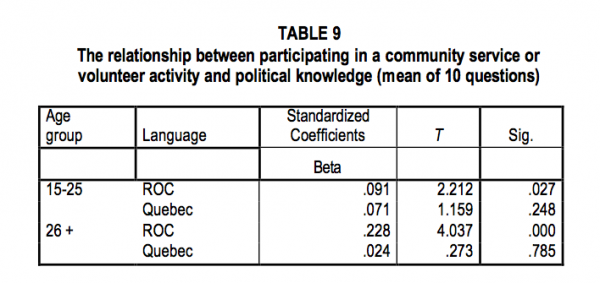

Like other such studies in the United States, the CIRCLE survey (see Lopez et al, 2006) poses a large number of questions about involvement in voluntary associations of various kinds. As noted, our interest is not in such activities per se, but in their relationship to informed political participation, especially voting, as well as to political knowledge. Hence only a small number of these questions are included in the Canadian survey. The most general asked: “have you ever spent time participating in any community service or volunteer activity, or haven’t you had time.” As Table 4 shows, the relationship between such involvement and political knowledge is significant for those over 25 in both countries, but only for the Americans under 25. In Table 4A, we look at a related question directed toward those still at school. The Canada-US difference again emerges when the indicator is the number of groups in which the students participate, though in neither case is there a significant effect on political knowledge. It does emerge in response to the question of whether any of these groups involve student government or social or political issues.29 Here we see a clear significant link between a positive response and political knowledge in the US, but none whatsoever in Canada.

One important difference between the two countries is thus emerging: participation in voluntary groups seems to be more important in producing politically informed young citizens in the US than in Canada.

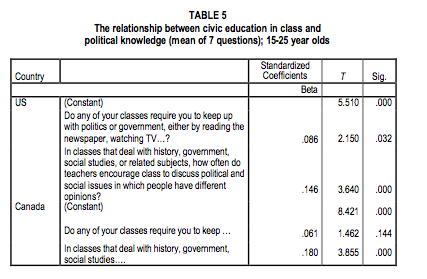

Having entered the school, we should next bring education itself into the analysis of factors associated with political knowledge. Regrettably, the CIRCLE survey asked far more questions about what goes on outside the classroom than inside it, and the comparative data is too limited and contradictory too take is very far. One question asked whether his or her classes required the respondent to keep up with politics or government, either by reading the newspaper, watching TV, or going onto the Internet. As Table 5 shows, the effect of such a reported requirement on the political knowledge of the students is weak, only approaching significance in the US. Nevertheless, the reported frequency that history, government, or social studies teachers encourage students to discuss political and social issues over which people have different opinions positively and significantly correlates with political knowledge in both countries.31

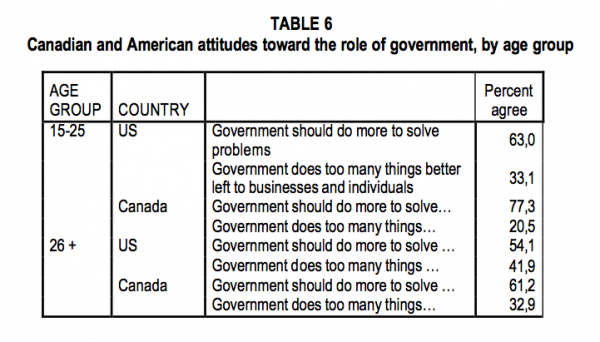

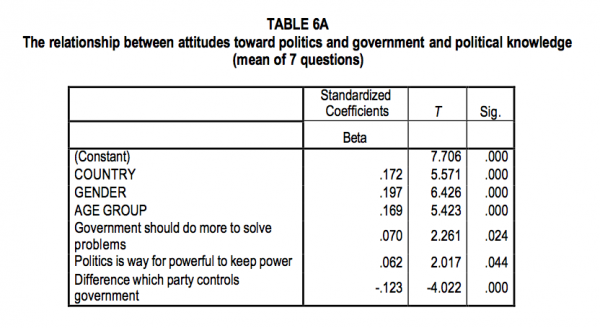

A number of other questions explored pertinent attitudes toward certain aspects of politics. As might be expected, Table 6 shows that a smaller proportion of Americans than Canadians, and older versus younger respondents, believe that government should do more to solve problems rather than that government does too many things better left to businesses and individuals. When it comes to the question asking whether politics is a way for the powerful to keep power to themselves or, instead, a way for the less powerful to compete on equal footing, slightly more respondents in both countries chose the cynical view. Table 6A shows that as a general rule, in both countries and both age groups, those that who want less government and see politics as serving the powerful, tend to display a higher average level of political knowledge.32 This is reinforced by the fact that the less one agrees that “it matters which party wins” the higher the average political knowledge. But, digging more deeply, on the question of party identification, which is not included in the table since the formulation is quite different in the two countries,33 we can see an important divergence. In Canada, all categories, young and older, male and female, French and English-speaking who identify with a political party are more knowledgeable.34 This is not quite the case in the US, with “independents” (.246) averaging the same levels of political knowledge as Republicans (.245), but almost half a point lower than Democrats.

Another question gets at a dimension suggested by Franklin (2005), namely, that the longer a person lives in the same neighbourhood the better the chance that they enter networks bringing them into contact with politically motivated individuals, and, in the case of young people, the greater the likelihood they are still living in the parental home and thus benefiting from an appropriate support group.35 The data, however, do not bolster his contention. No significant relationship was found between young people’s length of residence in the community and political knowledge (as well as intention to vote).

To sum up what we have seen thus far: the overall disparity between young Canadians and Americans is not great; nevertheless, compared to young Americans, young Canadians’ somewhat higher levels of informed political participation seem to be more closely related to traditional factors like newspaper reading and party identification than to voluntary group involvement in the community and at school.

The Canadian study, as is often the case, oversampled Quebecers in order to allow for statistically meaningful comparisons between them and Canadians in the English-speaking provinces (ROC). (Note that there is a correspondence between language and region since all Quebec surveys were conducted in French and all those in ROC were conducted in English.36) This dimension will become especially salient when we further explore the distinction suggested above, i.e., between factors such as media access and party identification versus those related to voluntary group involvement.

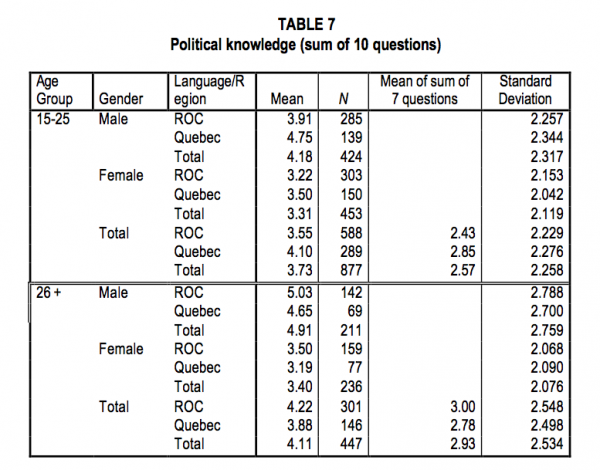

Table 7 presents mean correct answers among the Canadian respondents divided by age group, gender and language. (Note that since the language dimension is limited to Canada, we are able to base the score out of 10 possible rights answers. For comparative purposes, there is a separate column for data based on the 7 questions, which shows that the additional questions do not alter the overall relationships.) While for those over 25, political knowledge is higher among English speakers, both men and women, this is reversed when we get to those 15 to 25. Not only are young Quebecers, male and female, more politically informed (4.10 average questions correct out of 10) than their ROC peers (3.55) , but, unlike both them and their American peers, the young Quebecers are more politically informed than their elders (at 3.88).37 (We should note here that the knowledge questions are oriented toward national, i.e., Canadian, politics and institutions; we should also note that given the limited number of respondents in this category [N = 289 for those aged 15-25; and 146 for those 26 and over], the margin of error is too large to allow for definitive conclusions.)

Part of the explanation for this generational inversion lies in the modernization of Quebec’s educational system. In the International Adult Literacy Study (IALS) which tested a sample of the population of 20 countries in their ability to comprehend written texts in the early 1990s French speakers’ average score was well below that of English speaking Canadians (264.1 vs. 278.8). The gap dropped to 5 points when the test was repeated 10 years later, with the bulk of the change due to the youngest group. Indeed, francophones aged 15 to 25 had not just reduced the gap but actually surpassed their English-speaking counterparts 292.7 to 290 (Bernèche and Perron 2005).

One possible additional explanatory factor is the effect of politicization due to the polarization in Quebec over the national question and language issues during this period. Yet this does not easily fit the fact that Quebecers over 25 are less politically knowledgeable than their English Canadian peers. Moreover, we do not see evidence of the significant attitudinal differences that one would expect from a more politicized population. In relation to political cynicism, we find only a slightly greater likelihood for Quebecers than English Canadian young people to see politics as a means for the less powerful to compete (56 vs. 52 percent) rather than a means of the powerful keeping power for themselves. Conversely, however, this difference becomes highly salient when applied to the question whether they always do or intend to vote. Of the 123 uncynical young Quebecers, a full 96 said they (would) always vote, while of the 224 corresponding young anglophone Canadians, only 67 responded in the same way.

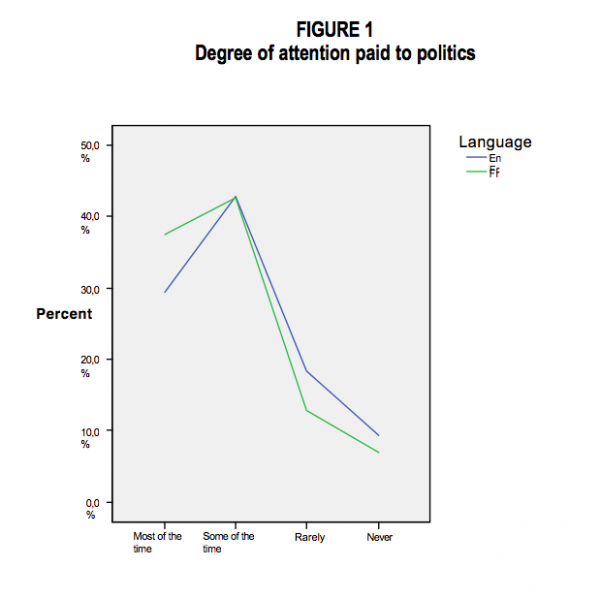

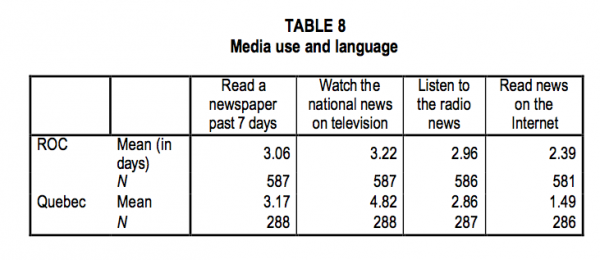

This distinction is noteworthy. While on most other attitudinal and most behavioural indicators there is nothing that significantly distinguishes young Quebecers from their ROC compatriots, a recurring difference is the young Quebecers’ attentiveness to the political world around them. As we can see in Figure 1 below, when asked about the extent to which they follow what’s going on in politics, 10 percent more Quebecers respond “most of the time.” This is confirmed in Table 8, which shows that young French Canadians report following the news in the media – especially via television, though not on the Internet – on significantly more days than their ROC peers. Conversely, when it comes to participating in a community service or volunteer activity, Table 9 sheds additional light on Table 4’s revelation of a weaker relationship of such activity with political knowledge for Canadians.38 Among Canadians, this relationship is significantly weaker for francophones.

The above findings indicate that the distinction drawn earlier between young Canadians and Americans is especially salient when applied to young Quebecers. We noted above that a comparatively very high proportion of those young Quebecers who see politics as a means for the less powerful to compete (rather than a means of the powerful keeping power for themselves) report that they always vote or intend to vote. We noted further that, compared to their anglophone peers, the young francophones follow news on television on significantly more days, and responded 10 percent more frequently “most of the time” when asked the extent to which they follow what’s going on in politics. In contrast, the effect of participating in a community service or volunteer activity on political knowledge was found to be significantly weaker for francophone Quebecers than for their English Canadian and, even more, their American peers.

These data can be seen as manifestations of alternative paths to informed political participation, bringing us back to the distinction drawn earlier. In response to the question of whether any of their classes require them to keep up with politics or government through the media, there is a clear contrast between the responses of the French and English speaking Canadian students. Among the former, 66 percent answered yes, compared to 46 percent of the former. This bolsters our contention that young Quebecers live and study in an environment that is more conducive to attentiveness to traditional political processes – elections, political parties and (activities intended to directly affect) government policies than that in English-speaking North America, which places greater stress on civic engagement via voluntary, nonpartisan activities and organizations unrelated to government policies.,

Canadians, especially those outside Quebec, both researchers and policy makers, thus confront a choice, specifically when it comes to civic education (see below). Observers (e.g., Westheimer et al. 2007) suggest that Canadian provinces tend to be taking the latter, American path. What we have seen suggests that, if this is the case, it may not be the wisest approach to take. For one thing, Canadians have options not available to Americans since Canada is not constrained by the institutional and constitutional obstacles faced by our neighbours to the south.39 In the United States, electoral administration is a prerogative of the states, hence, there can be no equivalent of Elections Canada: the many specific actions undertaken by nonpartisan public electoral authorities in other countries to address declining youth participation, must, in the US, typically be left to voluntary associations. Even registering young people so that they are eligible to vote in federal elections depends on local initiatives, since only state authorities can change the rules regarding voter registration.

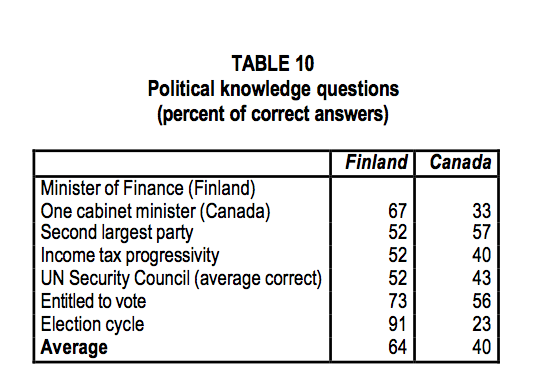

It was noted at the outset that recent efforts by Elections Canada directed toward young people 40 appear to have borne some fruit in the increased turnout of first time voters in 2004. There is more to be done here, and Canadians generally can profit from looking to the experience and efforts of comparable public bodies in high-civic-literacy countries for guidance. A useful comparison can be drawn with Finland, where several of the political knowledge questions posed in the Canadian survey were incorporated into a national survey.41 Table 10 compares the answers for the two countries (for the wording of the questions see the appendix). Given institutional differences (in particular the interval between elections, which is fixed in Finland),42 and the fact that it has been necessary to give added weight to the responses of the 35 percent of respondents over 25 in order to make the Canadian overall sample comparable to the Finnish one (which reflects the entire population rather than overrepresenting young people), we need be cautious in our interpretation of the specific numbers in Table 10. Nevertheless the overall higher level of political knowledge in Finland is beyond doubt.

Combined with the fact that Finland consistently places at the top of international educational performance league tables,43 such figures suggest that Canada could benefit from looking at the Finnish approach to civic education. Finnish 14and 15-yearolds in the last year of compulsory school are required to complete a full-year civic education course to graduate.44 The vast majority then goes on to complete upper secondary school (which usually takes 3 years), where they are given two compulsory and two optional civic education courses taught by instructors with both a teaching diploma and a master’s degree in history or civics.

Application of the Finnish model per se would not necessarily be appropriate for Canada, but certain aspects merit serious consideration. First of all, taking civic education is something every Finnish student takes for granted in the years leading up to the age of voting. Second, while the link to political life is stressed, it is related less to involvement in voluntary community organizations than to the political process as such. A recent drop in voter turnout among younger Finns has led to a refocusing on civic education at all levels, including teacher training. One dimension of this effort is to augment collaboration between teachers and local officials and politicians so that each can learn from the other through organized visits and hands-on experiences, with the priority on schools in areas with low turnout.45

Application of such approaches in Canada would entail, I contend, even greater efforts to target young people lacking the information on which to base an informed vote as engaged citizens. This entails designing and disseminating civic education programs to bring political knowledge to individuals low in the requisite home and community resources,46 supplemented by targeted government programs affecting the supply of political knowledge related to political party financing, information dissemination, voter registration, mock parliaments, etc. Such young people are frequently potential dropouts, and civic education courses need to be offered at a time when they are still in school but close to voting age, and in a form most likely to appeal to them. To identify what this might entail, we need to learn from such practices elsewhere. We currently lack even minimal systematic comparative data on basic aspects of civic education such as the hours of teaching time involved and whether it is compulsory and required for graduation.47 What we do know is primarily based on American studies, which suggest that civic education in the US is markedly skewed toward constitutional history and voluntary community participation (see Milner 2005). Few studies, however, single out civic education’s effects on those who need it most, i.e., students low in resources outside the school.48 It is reasonable to suppose that community involvement is less useful to those who need civic education more, and vice-versa.

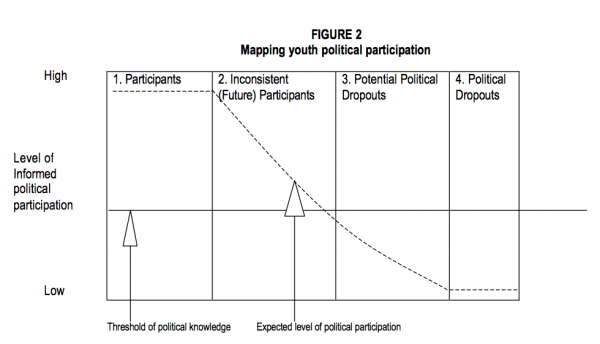

If this is so, it suggests that taking the American approach amounts to targeting primarily likely future political participants rather than potential political drop-outs. This is visualized in Figure 2 below, which categorizes North American young citizens based on a combination of political knowledge (pictured in relation to a minimal threshold of civic literacy) and likeliness to vote. The four groups are termed: participants; inconsistent (future) participants; potential political dropouts, and political dropouts. Based on the data analyzed here, we suggest that it is the group in rectangle 3, the potential but not yet actual political drop-outs, that should be the first priority, rather than those in rectangle 2 that the American approach tends to target.

As a rule, it is only when they are still in school that potential political drop-outs can be reached in meaningful numbers. To address the school dropout dimension, we should also consider, as I argued in a previous paper (Milner 2005), changing the voting age in order to offer civic education courses at a time when those needing them are still in school but close to voting age. With Canada’s – unlike Finland’s – high level of school dropout rates, lowering the voting age,49 in combination with compulsory civic education courses at an age when casting a first vote is looming in the young person’s horizon, would result in more potential voters still in school and, thus, in a position to benefit not only from civics classes, but also from complementary activities.50 I am thinking especially of mock elections that are being carried out high school students in the United States, Canada, Sweden and Norway (and many other countries no doubt).51

McDevitt and Kiousis (2006:3) recently assessed the effects over three years of Kids Voting USA,52 finding that “while the curriculum did not affect voting in the third year, 2004, directly, it did animate the family as a setting for political discussion and media use, habits that eventually lead to voting.” There is reason to believe that similar effects have been produced by parallel Canadian efforts53 supported by Elections Canada. 54

This is not the time or place to go into the content of civic education classes – except to stress what the survey data revealed. Media use is still strongly linked to informed political participation. When it comes to young people, the role of the school in fostering habits of newspaper reading remains fundamental. But clearly newspapers cannot do the job alone. Radio seems not to be an important source of information for young people, while the days of TV serving this function may be numbered. We found that using the Internet as a source of news is now more strongly correlated with political knowledge than reading newspapers. Emphasis must thus be clearly placed on bringing in appropriate electronic political information, with a view toward developing habits of attentiveness to – and the ability to pick up signals about – the political world. We are learning more about the kinds of electronic information sources that are most promising, how news Web sites without being overloaded with high tech gadgetry can be made more attractive and informative to young people (Sherr 2005; see also Gronlund 2007). As we have seen in this survey, in the US and, only slightly less so in Canada, a substantial proportion of young people arrive at voting age lacking the minimal knowledge needed to cast any kind of vote. Can the Internet be used to impart that knowledge, as well as induce the habits of attentiveness and skills required for acquiring it? Given the certainty that the Internet will be even more central to the socialization process of upcoming generation, this is a question that will have to be comprehensively addressed.

Clearly, further exploration of the relationship between what goes on in the classroom and informed participation is needed. For example, we would benefit from a study of the effects of the imposition of a compulsory civic education course in grade 10 in Ontario in 2000 – especially on the potential political dropouts from information-poor backgrounds. More generally, irrespective of other recommendations for action, a priority must be to include more and more detailed civic education-related questions in future surveys – especially questions that will allow researchers to pinpoint the effects of such courses on students lacking resources outside the school.

If there is a wider conclusion to be drawn, it can be linked to our finding that informed political participation among young people, though unacceptably low, tends to be higher in Canada (and especially for francophones) than in the US. We have noted that the relationship between involvement in voluntary associations and political knowledge is weaker for Canadians 15 to 25, reaching the point of insignificance for those in Quebec. We have suggested that the American approach, which emphasizes involvement in such associations, may not be especially effective at inducing political participation. This is certainly the case if we are concerned about informed political participation, since the American approach tends to downplay anything that smacks of partisanship.

For Canadians, it would appear that emulating the stress in the United States on involvement in nonpartisan voluntary group activities55 is likely to be less effective than the approach taken in the high civic literacy countries in Europe, whereby political knowledge is regarded as indispensable to meaningful political participation. Such an approach stresses measures that raise the level of political knowledge by making the environment of young people rich in political information, targeting especially those lacking the resources to gain access to it on their own. It looks to government programs in education, media support, political party financing, information dissemination etc. It does not discourage political involvement, even in civic education. At the core of this approach is getting political knowledge to those who lack it.

This distinction applies, before anything else, to the framework in which we approach the subject itself. I suggested earlier that certain influential researchers in the US tend to define away the problem by a methodology which, in effect, costlessly invites respondents to place themselves in a positive light by taking a subjective approach in which, taken to the extreme, youth participation becomes an expression of “that which engages me”?56 This path may be psychically rewarding for both the observer and observed and fit nicely into the dominant youth culture. But, I am persuaded, it fails to directly address the causes of the deficit in what we still take to be democracy. Researchers and policy-makers in Canada would do better to take an approach centered on identifying those who lack the needed the necessary political knowledge and getting it to them.

AASCU (American Association of State Colleges and Universities) 2006 Electoral Voices: A Best Practices Guide for Engaging College Students in Elections. Washington DC.

Andersen, Robert, Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott (2001) “Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices.” Working Paper #87: Centre for Research into Elections and Social Trends.

Archer, Keith and Jared Wesley (2006). “And I Don’t Do Dishes Either!: Disengagement from Civic and Personal Duty.” Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, York University, Toronto, ON, June 1-3, 2006.

Althaus, Scott. 1998. “Information Effects in Collective Preferences.” The American Political Science Review. 92: 545-58

Andolina, Molly, Scott Keeter, Cliff Zukin, Krista Jenkins. 2002. The Civic and Political Health of the Nation: A Generational Portrait. College Park Maryland: NACE.

Beem, Christopher (2005) “From the Horse’s Mouth conference” CIRCLE working document 27. (https://www.civicyouth.org/popups/workingpapers/wp27beem.pdf).

Bernèche, Francine et Bertrand Perron 2005. « La litteÌratie au QueÌbec : faits saillants – EnqueÌ‚te internationale sur l’alphabeÌtisation et les compeÌtences des adultes » (EIACA) 2003. QueÌbec : Institut de la statistique du QueÌbec.

Blais A, E. Gidengill, R. Nadeau and N. Nevitte (2002). Anatomy of a Liberal Victory: Making Sense of the Vote in the 2000 Canadian Election. Peterborough: Broadview.

Boylston, Frances, Henry Milner and Chi Nguyen. 2007. “The IDEA Civic Education Database: Some Preliminary Observations.” Presented at the ECPR General Conference, Pisa, September 2007.

Brynin, M., & Newton, Kenneth (2003). The national press and voting turnout: British general elections of 1992 and 1997, Political Communication, 20:59-77.

Chiche, Jean and Florence Haegel (2002). “Les Connaissance Politiques» in G. Grunberg, N. Mayer and P. Sniderman (eds.), La DeÌmocracy a L’eÌpreuve. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Dalton, Russell J. 2006. Citizenship Norms and Political Participation in America: The good news is … the bad news is wrong. Occasional Paper, The Centre for Democracy, Georgetown University

Delli Carpini, Michael X, and Scott Keeter. 1996. What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Edwards, Kathy, Lawrence J. Saha and Murray Print 2005. Youth, The Family, And Learning About Politics And Voting, Research Report 3: 2005 Youth Electoral Study Centre for Research and Teaching in Civics, University of Sydney

Franklin, Mark N. 2004. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——— 2005. “You Want to Vote Where Everybody Knows Your Name: Anonymity, Expressive Engagement, and Turnout Among Young Adults”. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington DC, September 2005.

Friedland, Lewis A., and Shauna Morimoto (2006). “The Lifeworlds of Young People and Civic Engagement.” in Peter Levine and James Youniss (eds) YouthCcivic Engagement: an Institutional turn: Circle working paper 45, February 2006

Gidengil, Elisabeth, AndreÌ Blais, Neil Nevitte, and Richard Nadeau (2003) “Turned Off or Tuned Out: Youth Participation in Canada. Electoral Insight: July 2003, Elections Canada.

Goul Andersen, Jørgen & Jens Hoff (2001) Democracy and citizenship in Scandinavia. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Grönlund, Kimmo. 2003. “Knowledge and Turnout – a Comparative Analysis.” Paper presented at the 2003 ECPR Conference, September 2003, Marburg, Germany.

——– 2007. “Knowing and Not Knowing: The Internet and Political Information,” Scandinavian Political Studies, 30: 397–418.

Henzey, Debra. 2003. “North Carolina Civic Index: A Benchmark Study Impacts State-Level Policy. National Civic Review,” 92:1, Winter 2003.

Holmberg, Soren and Henrik Oscarsson (2004). Swedish Voting Behaviour. Swedish Election Studies Programme, Gothenberg.

Hooghe Marc, Dimokritos Kavadias, and Tim Reeskens Tim. 2006. “Intention to Vote and Future Voting Behavior. A Multi-Level Analysis of Adolescents in 27 Countries.” Presented at the Metting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia September 2006.

Hunter, Susan and R.A Brisbin Jr. 2000. “The Impact of Service Learning on Democratic and Civic Values.” PS: Political Science and Politics 33:3: 623-626.

IDEA. 1999. Youth Voter Participation – Involving Today’s Young in Tomorrow’s Democracy. Stockholm: IDEA.

Iyengar, Shato and Simon Jackman. 2004. “Technology and Politics: Incentives for Youth Participation.” CIRCLE (The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement). https://www.civicyouth.org/.

Junn, Jane. 1991. “Participation and political knowledge.” In Political Participation and American Democracy, ed. William Crotty. New York: Greenwood Press.

Keeter, Scott, Cliff Zukin, Molly Andolina and Krista Jenkins. 2002. “The Civic and Political Health of the Nation: A Generational Portrait.” CIRCLE (Pew Charitable Trusts): College Park, MD.

Lopez, Mark Hugo, Peter Levine, Deborah Both, Abby Kiesa, Emily Kirby, Karlo Marcelo. 2006. “The 2006 Civic and Political Health of the Nation: A Detailed Look at How Youth Participate in Politics and Communities”. CIRCLE: Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement

McDevitt, Michael, and Spiro Kiousis, 2006. “Experiments in Political Socialization: Kids Voting USA as a Model for Civic Education Reform” Circle Working Paper 49, August 2006.

Micheletti, M., A. Føllesdal and D. Stolle (eds). 2003. Politics, Products, and Markets. Exploring Political Consumerism Past and Present. New Brunswick: Transaction Press

Milan, Anne 2005. “Willing to participate: Political engagement of young adults.” Ottawa: Canadian Social Trends.

Milligan, Kevin, Enrico Moretti, and Philip Oreopoulos (2003.). Does education improve citizenship? Evidence from the U.S. and the U.K. September 16, 2003

Milner, Henry. 2002. Civic Literacy: How Informed Citizens Make Democracy Work. Hanover: University Press of New England. )

——— 2004. “First past the Post? Progress Report on Electoral Reform Initiatives in the Canadian Provinces.” Policy Matters. Montreal: IRPP

——— 2005 “The Phenomenon of Political Drop-outs: Canada in Comparative Perspective.” Choices: IRPP .

———- 2005a. “Do We Need to Fix our System of Unfixed Election Dates?” Policy Matters. Montreal: IRPP, December 2005.

———-, 2007 “Loewen, Peter and Hicks, Bruce 2007. “Compulsory Voting and Informed Youth: A Field Experiment.” Policy Matters. Montreal: IRPP, forthcoming.

Mindich, David. 2005. Tuned Out: Why Americans under 40 Don’t Follow the News. New York: Oxford. NCES (National Center for Educational Statistics) 1999. NAEP 1998 Civics Report Card for the Nation. Washington: US Department of Education.

Norris, Pippa, 1996. Does television erode social capital? A reply to Putnam, PS: Political Science and Politics, 29:474-480.

O’Neill, Brenda 2007. “Indifferent or Just Different? The Political and Civic Engagement of Young People in Canada.” Ottawa CPRN.

Oscarsson, Henrik 2007. “A Matter of Fact? Knowledge Effects on the Vote in Swedish General Elections, 1985–2002.” Scandinavian Political Studies, 30: 301-322.

Pammett, Jon and Larry Leduc. 2003. “Explaining the Turnout Decline in Canadian Federal Elections: A New Survey of Non-voters.” Ottawa: Elections Canada

Sherr, Susan 2005. “News for A New Generation: Can it Be Fun and Functional? CIRCLE Working Paper 29: March 2005 .

Stolle, Dietlind and Ceci Cruz. 2005. “Social Capital, Youth Civic Engagement and Democratic Renewa.l” Policy Research Initiative, Government of Canada.

Stroupe, Kenneth S. and Larry J. Sabato. 2004. “@Politics: The Missing Link of Responsible Civic Education,” CIRCLE (The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement) https://www.civicyouth.org/PopUps/release_stroupe.pdf

Thomas, Melanie and Lisa Young (2006). “More Subject than Citizen: Age, Gender and Political Disengagement in Canada.” Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, York University, Toronto, ON, June 1-3, 2006.

Torney-Purta, J., and Barber, C.H. 2004. Strengths and weaknesses in U.S. students’ civic knowledge and skills: analysis from the IEA Civic Education Study. (Fact Sheet.). College Park, MD: CIRCLE.

Tossutti, Livianna 2004. “Youth Voluntarism and Political Engagement in Canada.” Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, Winnipeg, June 2004.

Von Erlach, Emmanuel (2006) “Politicization in Associations: An Empirical Study of the Relationship between Membership in Associations and Participation in Political Discussions,” World Political Science Review: Vol. 2: No. 1, Article 3.

Walker, Tobi. 2000. “The Service/Politics Split: Rethinking Service to Teach Political Engagement.” PS: Political Science and Politics 33:3: 647-649.

Wattenberg, Martin P. 2007 Is Voting for Young People, Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Westheimer, J., Cook, S., Llewellyn, K., and Molina GiroÌn, A. (2007).The State and Potential of Civic Learning in Canada. Democratic Dialogue Occasional Paper Series. Ottawa, ON: DemocraticDialogue.com.

Whiteley, Paul 2005. “Second Literature Review, Citizenship Education: The Political Science Perspective.” London: National Foundation for Educational Research Research Report RR631.

For immediate distribution – November 15, 2007

Montreal – Canada should look to Europe, not the US, as a model for increasing political awareness among its youth, says IRPP study. Political knowledge is a democratic value. It is also an important ingredient in political participation. However, as the IRPP study being released today demonstrates, young Canadians know comparably little about politics.

In this study author Henry Milner compares survey data on civic literacy from the US and Canada. He finds that young Canadians’ political knowledge is low – only slightly higher than that of their American counterparts and, therefore, well below the level of young Europeans. His research reveals that young Quebecers, whose level of political knowledge surpasses that of other Canadian youth, are the reason that Canada scores above the US. The situation requires redress if Canada is to stem the declining voter turnout and decreasing civic participation that currently plagues the country.

The results of Milner’s research reveal a startling lack of political knowledge in Canada and the US:

Looking at the higher levels of political knowledge among European youth, the author argues that European nations are better at disseminating the information and skills needed to turn young people into participating citizens. This, he says, “raises the question of whether Canadians should look there, rather than to the United States, in seeking to address the issue.”

He argues that emulating the US, where youth political knowledge is lower than in Canada is not an option. Instead Milner proposes looking to European countries, where youth populations score consistently high on tests of political and civic awareness, as a model.

European countries focus on civic education programs that target lower-income students who lack the resources to acquire political knowledge on their own. According to Milner, “such young people are frequently potential dropouts, and civic education courses need to

be offered at a time they are still in school but close to voting age, and in a form most likely to appeal to them.”

Political Knowledge and Participation Among Young Canadians and Americans, by Henry Milner, can be downloaded free of charge from www.irpp.org

-30-

For more information or to request an interview, please contact the IRPP.

To receive the Institute’s monthly newsletter via e-mail, please subscribe to the IRPP e-distribution service by visiting its Web site, at www.irpp.org.