There is scant literature on municipal electoral politics in Canada, but what little exists points to the likelihood that in a larger city, voter turnout would decline and incumbency would become the major predictor of electoral success. These points have been repeatedly raised in debate over the merits of municipal merger and clearly warrant further study. In an examination of the three elections following merger of the City of Toronto, it is found that incumbents had a virtual lock on the new council positions. Significant for local councilors who might be contemplating future initiatives for merger is the finding that incumbency at the regional-level provided a distinct electoral advantage over membership in city and town councils. The most significant finding is that, while voter turnout surprisingly increased as opposed to decreased in the larger ëmegacityiÌ, voter engagement was greatly influenced by socio-economic status, raising new questions about the implications of merger and about voter turnout in Canada in general.

On April 21, 1997, the Legislature of Ontario, after much heated debate, merged six city and borough governments with the government of the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, thereby creating a single municipal government to provide local services to over two million people (City of Toronto Act, 1997).1 The large size and entirely urban character of this new municipality, plus the rather vocal opposition to the idea of merger, 2 led to the new City of Toronto being dubbed ‘megacity’.

Since then, a number of other municipalities of varying sizes have been merged throughout Canada, including most of the municipalities in the Province of Quebec and several in the Halifax area of Nova Scotia. So heated was the debate over merger in Quebec that two years after the law came into effect and merger had been completed, the idea of merger was still an identifiable campaign issue in the provincial election of 2003 and a subsequent vote on demerger was held in 2004.

Whether or not the merger trend will continue to spread across Canada, or to other countries, or whether the move in the future will be to follow the example of several Quebec cities and demerge, it is clear that the debate is far from over. It is therefore important that the implications of merger/demerger are properly understood. One of the areas most in need of analysis is the representational question, as elected municipal councils are one of the institutions being merged.

With the last election held on November 10th 2003, Toronto has now had three elections for its megacity council 3, thereby allowing us to examine and draw some conclusions about incumbency and voter turnout in Canada’s largest city, the single-tiered Canadian m’egacity’ of Toronto.

There are two arguments that are relevant to the representational question. Verba and Nie (1972) have suggested that smaller municipal structures might be more effective because people are more likely to know one another and to know the candidate in small communities, thereby creating a direct link between political representation and the sense of community, something that will decline in large, complicated and impersonal cities. On the other side of the debate, Milbrath (1977) has suggested that voter involvement might be higher in large cities because of the excitement generated by larger election campaigns in a concentrated urban environment. Increased media, more resources and professional political communication strategies would combine to mobilize and connect voters to their elected representatives.

Since then, most of the evidence supports Verba and Niei’s contention that voters in the large municipalities will be less engaged. In particular, Kushner, Siegel and Stanwick (1997) found in the province of Ontario that voter turnout was lower, and incumbents had an increasing electoral advantage, the larger the municipality. In fact, they went so far as to suggest that the ‘lower voter turnout that accompanies increased municipal size supports a political argument against consolidation’ (542). It is therefore expected that voter turnout will be lower for the megacity of Toronto than it was for the former municipalities.

With a larger city and thus larger wards, voters are further removed from elected officials. It will be harder for voters to come into personal contact with their candidates during the campaign period or to obtain sufficient information about increasingly complex urban-governance issues so as to make informed decisions. This, in turn, will make voters less motivated to go to the polls.

It is also expected that incumbency will offer a great advantage in the megacity. Sometimes characterized as ‘preferring the devil you know to the devil you don’t’, incumbents benefit from name recognition, appreciation for public service and experience. Incumbency can offer voters a sense of stability and continuity, often there is personal appreciation for a specific service provided to a constituent and sometimes it is tied to vested local interests. Furthermore, the office itself has re-election built into it by allowing (at taxpayer expense) for constituent contact and for feedback on a regular basis in the name of informed representation.

Given the ethnic diversity of Toronto, election campaigns can be complex. Campaign literature often needs to be in multiple languages, canvassers may need to speak a variety of languages and sometimes cultural differences need to be addressed when navigating the minefield of local politics (where zoning and by-law changes often pit community against community). Incumbents, however, enter a campaign already organized to deal with linguistic and cultural community challenges, having had to function in this political environment on council, usually with the advice and support of the city bureaucracy and paid political advisors (not to mention such basic services as translation). They will often have previously established networks among community leaders.

It is therefore expected that the complexity and diversity of a megacity will give incumbents a strong advantage. Furthermore, it is expected that the larger and more diverse the city, the larger and more complex the wards, the greater the ‘disconnect’ will be from the voters. This should manifest itself in lower voter participation.

There is surprisingly little academic research on municipal elections in Canada. Major metropolitan areas have been studied (Magnusson and Sancton, 1983) and a few specific subjects have been explored in detail such as gender (Gidengil and Vengroff, 1997) and ward versus at-large elections (Tennant, 1980). There have been two studies that addressed the determinants of electoral success at the councilor level in Ontario municipalities, using the years 1982, 1988 and 1994 (Kushner, Siegel and Stanwick, 1997), and for the first mayoral election in the merged city of Toronto (Stanwick, 1997).

This lack of research is disappointing. One would think that, with ward boundaries drawn around homogeneous communities and the lack of formal party identification and apparatus, municipal elections commend themselves to the study of such things as the impact of socio-economic factors and incumbency (research items that have been of great interest to Canadian political science at the federal and provincial levels).

The primary reason there has been so little study is because of the difficulty in collecting and analyzing municipal election information. For the most part, municipalities administer their own elections, so researchers must contact each municipality separately and rely on the good graces of city officials for data and information. With the numerous re-organizations of municipalities during the 1980s and 1990s, ward maps, council composition and methods of selection were frequently re-engineered, which is a further impediment to analysis. With merger, this has been complicated yet again since records from previous councils are not usually turned over to the successor municipality (since in law this is a new corporation).

To undertake this study, information pertaining to the candidates in the 1994, 1997, 2000 and 2003 elections was taken from newspapers and from whatever city records could be found.4,5 Election statistics and boundary maps were provided by the City of Toronto Clerk and the Director of Elections, and their respective staffs, as well as the Toronto Archives.6

Census data were collected to measure the following population characteristics: English mother tongue, total visible minorities, percentage of immigrants, mobility based on five years, percentage of rented private dwellings, less than grade 9 education, university education, unemployment rate, average household income and median household income, and percentage of low income incidence in economic families. These socio-economic data were derived from the 2000 census, which the City of Toronto had commissioned Statistics Canada to generate for each of the 44 Toronto ward boundaries.7 These census data were applied to both the 2000 and 2003 ward turnout in an effort to determine if, and how, socioeconomic factors impact on voter turnout.8 Voter turnout figures were determined based on the number of eligible electors identified per the voters list, plus revisions at the poll, contrasted with the number of people who actually voted.9

For the purposes of this study incumbency is defined as being a member of the council of either Metropolitan Toronto or one of the six city and borough councils, or of the new megacity council, as of the day of the election (Nov. 10th of that respective year). Councillors and mayors who had served before but were not on council at the time of the election are not treated as incumbents, nor is a person who was serving on any other elected body, such as a school board or provincial legislature, at the time of the election (unless they were simultaneously serving on one of the seven councils).

Turnout for municipal elections is almost always lower than for provincial or federal elections (Drummond, 1990: 250). And larger cities typically have lower turnout than smaller municipalities (Kushner, Siegel and Stanwick, 1997: 542). Nevertheless, voter turnout went up in the 1997 Toronto municipal election, the first for the newly merged megacity.

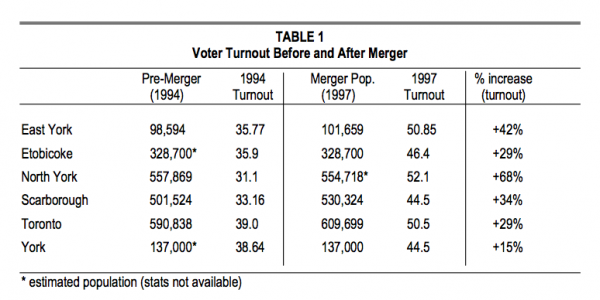

In 1994, the last election prior to merger, there was a turnout of 35.3 percent in what would become the megacity of Toronto. This is in keeping with the provincial average of 37 percent for municipalities with a population of 100,000 or more in that year (Kushner et al., 1997: 542). Turnout for the megacity of Toronto in 1997 was 48.68 percent (up 13.38 points or a 40 percent increase). And, as Table 1 shows, an increase in voter participation is true for each of the former six city and borough areas.10

The first merger election in 1997 was seen as a battle between the mayor of the old City of Toronto, Barbara Hall, largely identified with the New Democratic Party, and the mayor of the old City of North York, Mel Lastman, largely identified with the Progressive Conservative Party.11 Since both the cities of Toronto and North York contributed roughly equally to the population of the new megacity,12 even without partisan differences one could have expected regional loyalties to make this a tight race.

When there is a tight race between front-running candidates, voter turnout will be higher (Tindal and Tindal, 1995: 247). It will also be higher when there is a highly partisan contest (Karnig and Walter, 1983: 491505). There were also between five and seven referendum questions in 1997, and these have been shown to increase turnout (Tindal and Tindal, 1995: 247). Furthermore, this was the first election following merger, and merger had been strongly opposed, resulting in this vote being ‘the culmination of roughly one year of extraordinary high profile politics which never lost momentum’ (Stanwick, 2000: 556).

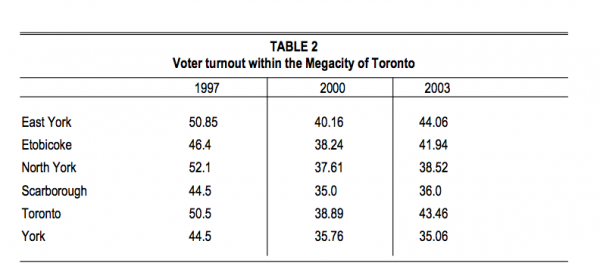

If the 1997 merger election were an anomaly, we would expect voter turnout to decline dramatically for the 2000 and 2003 elections. Table 2 shows that voter turnout was, in fact, much lower in the two subsequent elections for each of the former municipalities.13

However, voter turnout has not dipped below the 1994 level of 35.3 percent. In 2000, voter turnout was 36.1 percent and in 2003 turnout was 40.2 percent.14

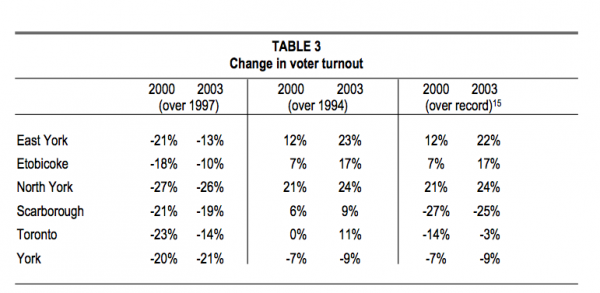

Table 3 shows that while the 2000 and 2003 elections witnessed a decline in voter participation over the original merger election in all of the former municipalities, there was in fact an increase over the turnout numbers experienced in the pre-merger election of 1994 in all but one municipality. What is more, there appears to be an increase in half of the city over the record highs for turnout in the former municipalities.

There are several caveats worth noting, aside from the obvious one that the numbers in Table 3 are more dramatic because they are the percentage of change as opposed to simply the number of points that have shifted. The cities in question were all in the category of large municipalities before merger, as defined by Kushner et al. (1997): that is to say they each had a population of 100,000 or more and were already experiencing lower turnouts. The previous record highs are, by definition, anomalous turnout results unique to each of those elections in which they were registered.

That being said, these figures would seem to indicate that voter turnout in a megacity might increase, in spite of expectations. Milbrath (1977) argued that voter turnout would be higher in urban environments because the political excitement would encourage participation and mobilize voters. While research has shown that large municipalities have lower voter turnout than small municipalities, perhaps there is a critical mass of urban size that creates enough excitement and awareness about the election to overcome the disconnect with the individual voter that is the expected side effect of larger city and ward size.

After some initial evidence that was presented to the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing that socio-economic factors may have an influence on voter turnout in Canada (Bakvis 1991), the general consensus that has emerged among Canadian political scientists is that they are not having a significant impact on voter turnout, though they continue to be part of the debate over turnout in other developed democracies.16 Part of the reason for this is the lack of class-based politics and identity in Canada, though it is undoubtedly also a by-product of how electoral boundaries are drawn at the federal and provincial levels. Vastly different communities are often combined into a single constituency, creating an almost median constituency profile within regions or cities.17 The smaller wards at the municipal level, with boundaries more closely coinciding with homogeneous self-identified ‘communities’, should lend themselves to a closer examination of SES factors and how they might impact on voter turnout in Canada.

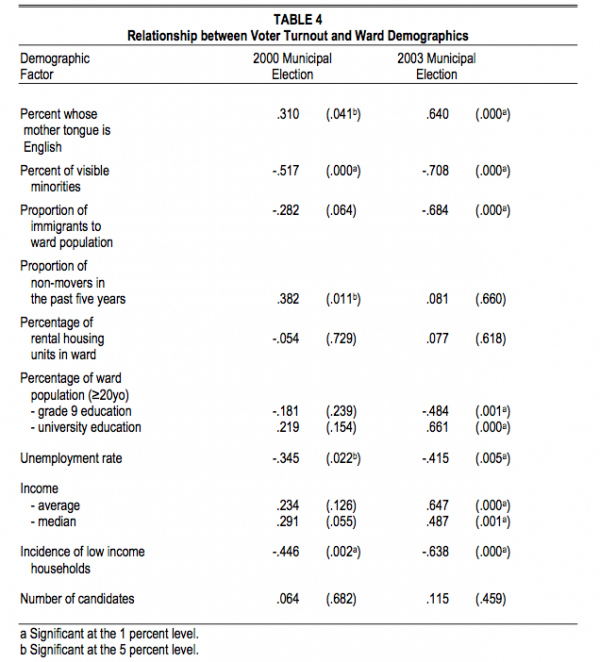

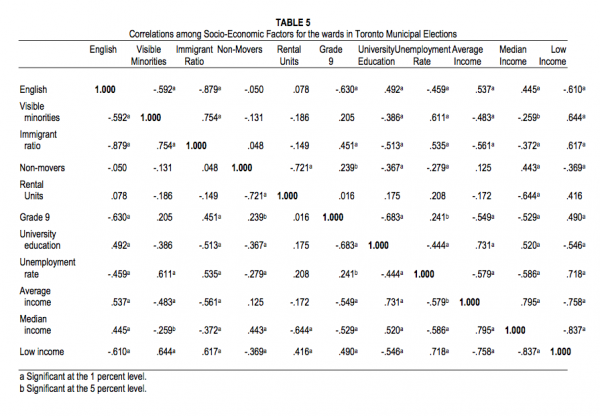

Table 4 reports Pearson correlation coefficients measuring the linear relationship among the socioeconomic characteristics of the wards and the voter turnout for each of the 2000 and 2003 elections (with their significance in parenthesis).

What we find is that turnout was significantly higher in wards with a greater proportion of high-income earners and a lower incidence of low-income households. Similarly, turnout was significantly negatively correlated with the unemployment rate in each ward. While the correlation with the percent of rental units was not statistically significant, it is in the direction consistent with the argument that in municipal politics (where taxes are collected on property) the property owners are more aware of municipal taxes and more concerned with the tax rate and the services the city provides. The fact that turnout was higher in areas where mobility was lower also lends credence to this conventional wisdom.

In wards with proportionately greater immigrant populations and visible minorities, turnout was significantly lower; and in wards with a greater proportion of people whose mother tongue was English, the turnout was higher. Language and culture create barriers for new Canadians that make it harder for them to fully participate.

Education is another item that one would expect to have an impact on voter turnout. Not surprisingly, in wards with proportionately more university-educated residents, turnout was significantly higher and in wards with proportionately more people who had not finished grade nine (among people 20 years of age or older), the turnout was lower. This is in keeping with the argument that information costs (i.e. the costs of obtaining, sorting and processing information) are higher for people with lesser education.

There is not only some degree of overlap and redundancy in some of these variables, but there can also be seen to be a causal direction. For example, greater education can lead to higher income and, since highly educated people earning higher incomes are able to afford more expensive homes, property taxes might increase the perceived importance of electoral participation for this group. Unfortunately, because of the relatively few number of cases available, it will not be possible to disentangle these variables. However, it should be possible to come up with a predictive model.

Up until this point we have concentrated on the independent effects of voter-turnout and socio-economic factors. A regression model will now be estimated to determine the relative impacts of socio-economic factors on voter turnout.

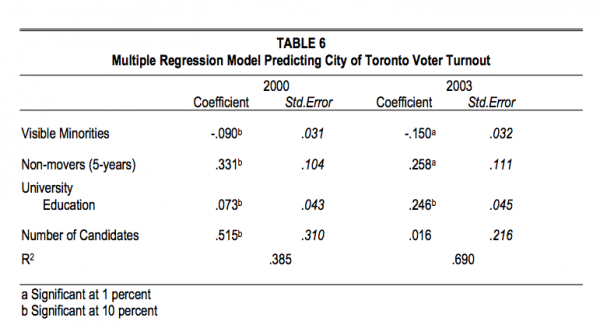

Table 5 shows a number of high correlations, such as visible minorities, immigrant ratio and English as a mother tongue, or unemployment and low-income households. To avoid the problem of multicollinearity, the regression model has been reduced to four factors that are representative of specific clusters. These are items expected to influence voter turnout and are quite distinct from one another.18 This model has been run for both the 2000 and 2003 elections.19 An income variable was not included because it was found to be too closely correlated with education, in particular, but also with mobility and visible minorities.

This model is quite robust. Within it, non-mobility is the most significant factor in explaining voter turnout when the other items have been controlled for, but each of the other items (except for number of candidates in 2003) remains statistically significant.

As mentioned above, homeowners receive a tax bill and are aware of the cost of municipal government (renters never see a tax bill since it is incorporated into their rent). What is more, the longer a person stays in a community the more likely it is that she or he will connect with that community. Both of these motivating factors for municipal electoral participation would be captured in the mobility variable.

The relevancy of the number of candidates is deserving of specific comment. In the bivariate analysis the number of candidates running was not statistically significant. What is more, it appeared to have less of an impact in the 2003 election than in the 2000 election. When included in the regression model, the number of candidates was significant in 2000 and appears to have had more of an influence on voter turnout than the other variables and certainly more than it did in 2003 (though with a higher standard error).

Most voting behaviour analysis works from the assumption that a ‘voter’ may be motivated by a number of factors, and researchers attempt to find a model that properly predicts this theoretical individual’s behavior. However, it is quite possible that different factors motivate different voters. If we postulate that there might be a segment of the population that will be mobilized by the excitement of politics – let us call it the ‘politically interested cohort’ – this might explain what is happening statistically with the ‘number of candidates’ variable.

While the number of candidates appears to have little impact on voter turnout on its own, when other mobilizing influences are controlled for (in this case visible minorities, education and non-movers) there appears to remain a segment of the population mobilized simply by the excitement of the campaign. This might also explain why this variable was less significant and of lower influence in the 2003 election in the regression model since that election had a hotly contested mayoral race. The ‘politically interested cohort’ would have been mobilized across the city in 2003, making the impact of multiple candidates in any one ward less significant.

At first glance, ‘politically interested cohort’ might seem to be a misnomer, since those persons genuinely interested in politics – persons the media and public discourse often refer to as ‘political junkies’ – will likely be mobilized by any election campaign. However, this segment of the population is likely composed of ‘soft voters’ who have no strong self-interest mobilizing them to vote, such as drives Downs’ (1957) homo economicus. These people would become aware of the election because of the increased excitement generated by the campaign (either because of a plethora of candidates in their ward or a high profile mayoral contest), and would get swept into the voting booth on election day by sheer momentum, generated by political interest, rather than economic self-interest (or a sense of civic duty).

Clearly socio-economic characteristics, such as education/income and ethnicity, are having an impact in Toronto municipal politics. Part of this might be because of the electoral lists. Electoral lists are generated from tax rolls,20 so the more marginalized population that would include many immigrants, people who don’t speak English, visible minorities, unemployed, low-income families, renters and people who have moved recently, will be underrepresented on the list. While this does not prevent these people from voting, there is a mobilizing dimension to the electoral list whether it be generated through the personal contact of enumeration or simply receiving election literature (such as polling station information), properly addressed to the voter at her or his correct address (Black, 2003). These omissions have a ripple effect since canvassing by the respective campaigns usually is based on the electoral list and missing names will result in campaigns skipping that residence for telephone and door-to-door canvassing and, therefore, not including them on election day when ‘getting-out the vote’. Finally, the energy required from the voter to have her or his name added to the list at the polling station may be seen by some as too great a barrier to voting.

Why the correlations become stronger for the variables in 2003 (something that is also seen in Table 4 with the bivariate relationships) is unclear. Voter turnout was higher in this election and one would expect that in higher turnout elections socio-economic differences would be less visible (obviously with 100 percent turnout there would be no evidence of socio-economic differences). That being said, it is worth keeping in mind that ‘higher’ turnout at the municipal level still means that less than 50 percent of the people on the electoral list voted.

One explanation for the differences on how SES factors impacted on these two elections might be found in the events of the election itself. Mayor Lastman, who had won the election in 1997 over Barbara Hall, did not run again in 2003. ‘Right-leaning John Tory’ came from ‘single digits last winter. . . close to pulling off an upset win’ over ‘left-leaning’ councilor David Miller (Globe and Mail, Nov. 11, 2003: A14), which may mean that particular SES constituencies were mobilized specifically in that election.

This hotly contested and partisan competition at the level of mayor would explain the higher voter turnout in 2003 over 2000. It could also explain why the number of candidates at the councilor level was not significant in our voter turnout model for 2003, and yet it was for 2000 (as noted above).

Another possibility is that there is an increasing disconnect between certain segments of Toronto and municipal politics. Obviously, with only two elections to study a trend cannot yet be predicted, but this warrants further study.

In addition, the Milbrath (1977) mobilization theory that could explain the higher voter turnout in megacity Toronto over its component cities does not presume that everyone mobilizes equally. The larger city with more complex wards could act as a deterrent to specific segments of society. Clearly there is an imbalance in participation rates along socio-economic lines in both elections.

Most of the research into incumbency in Canada has been done at the federal and provincial levels, where it has been found that incumbents probably have an advantage because of name recognition, experience and better access to campaign financing (Krashinsky and Milne, 1986). This translates at the municipal level, where there is no formal party identification,21 to a strong advantage, something even more significant in larger municipalities (Kushner et. al., 1997).

One of the advantages attributed to incumbency is that ‘incumbents normally do not have the disadvantage of having to run against an incumbent themselves’ (Marland 1998: 34). However, the election of 1997, which combined the Toronto Metropolitan (or ‘regional’) government with the six local governments, reduced representation and pitted incumbent against incumbent. This makes the issue of incumbency in that election particularly deserving of examination.

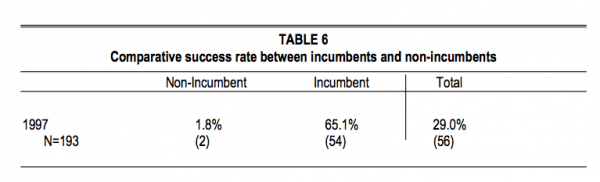

In the process of merging the six city and borough governments with the government of the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, the number of elected council positions went from 101 down to 56 plus the mayor.22 In what can best be described as a political version of ‘musical chairs’, 83 incumbents divided themselves up relatively evenly and competed against one another for the remaining seats left at the municipal level.

With so many incumbents running against one another it is not surprising that so few non-incumbents were successful. Table 6 shows that with 193 people competing for 56 councillor positions in the merger election, non-incumbents had less than a two percent chance of success.

A word of caution should always be expressed when examining chances of electoral success at the municipal level. With few barriers to entry, ‘frivolous’ candidates will invariably distort the results.23 However, even allowing for candidates who are running for attention or the novelty, running on a single issue or running because of a mistaken belief that their ideas or candidacy have a following, there was no shortage of qualified candidates who sought election to the new megacity council.24

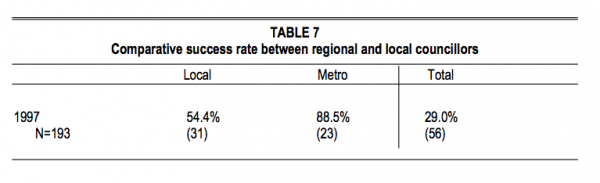

The idea of merger arose in the 1990s where buzzwords like ‘eliminating duplicatioon’ had become part of the Canadian political lexicon and the commonly used reference to local and regional government as ‘twotiered’, which implied duplication, brought municipalities and their services under increasing public and government scrutiny. It is therefore worth exploring whether or not incumbency on either tier of government provided an electoral advantage.

Prior to merger, there were 34 people who served on the Metropolitan Council for the greater Toronto area. These included the mayors of the six cities and boroughs, the councillors from the city of Toronto and councillors elected from the other cities specifically to serve on metro (elected either city-wide or for several combined local wards).

Table 7 shows that an incumbent coming from the metro or upper tier had better chances of electoral success in the merger election than did a local councillor. At face value this appears contrary to the old adage that ‘all politics is local’ and the belief that elected representatives in small communities have a stronger bond with their constituents. However, it is important to keep in mind that this is a reflection of the chances of electoral success in the new council with its larger wards, not a comment on respective connectivity between voters and their representatives at either of the two previous levels.

The new 1997 council had only 28 wards, with dual member representation.25 These were larger, more complex and diverse wards than all but a few candidates had campaigned in and represented before merger.

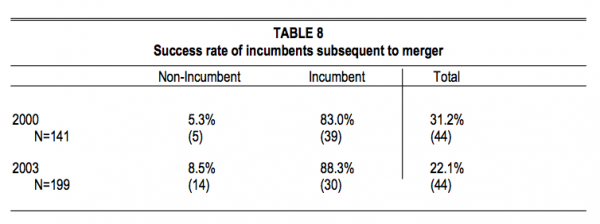

Table 8 makes it apparent that incumbency continues to be an overwhelming determinant for electoral success in the megacity. While non-incumbents had a slightly better chance of success in the two subsequent elections than they did in the merger election, it is well below the 14 to 16 percent average experienced by non-incumbents in large municipalities across Ontario (Kushner et al 1997: Table 2), though the success rates of incumbents is not out of proportion.

The lower success rate for non-incumbents (without a proportional change in success rates for incumbents) may be an indication of a lower attrition rate in a megacity, possibly due to higher salaries and a perceived increase in status of megacouncil membership (making the position attractive as a career and less a stepping stone for higher political office).

The electoral success of incumbents was higher in the 2003 election. In part, this is because in the 2000 election the city of Toronto made the transition from 28 dual-member wards to 44 single-member wards, resulting (once again) in several incumbents competing against each other for seats on the new council.

However, it is possible that the increase in success rates for incumbents is due to the fact that elections in the megacity increasingly favour the incumbent as the city becomes more complicated and impersonal. As with voter turnout, however, it is not possible to forecast a trend with only two elections. What we can state definitively though is that in a megacity incumbency matters, providing a virtual lock on electoral success.

In the 1997 merger election, incumbents running from the metro or regional level had a distinct advantage. It is possible that the voters considered the candidates who served on metro more qualified for the new positions. The delivery of services in Metropolitan Toronto had become more centralized over the previous decade and it would not be unreasonable to view merger as the absorption of the local governments into the larger entity of metro Toronto.26

It is also possible that this is simply a reflection of the increasing power of incumbency in the megacity of Toronto. Councillors running from metro would have higher name recognition and quite likely would be perceived as being more ‘senior’ by the voters. They would have larger election machines already in place having run in larger geographic areas than their local councillor cousins, familiarity with more of the communities contained within the very large and ethnically diverse megacity ridings, and easier access to resources (plus previous experience raising that sort of money).27

These advantages of incumbency would in all likelihood favour the metro councillor over the local councillor in a merger election and continue to help incumbents against outside challenge in the large wards of the megacity.

It would appear that voters may be relying on the shortcut offered by the slogan ‘re-elect’ to augment the lack of necessary information to make their selections in the large wards of a more complex megacity.

One must be cautious about extrapolating from this evidence and making unwarranted conclusions or rash recommendations. After all, these results technically apply only to one city and, even there, to three specific elections. They may not translate to other cities or levels of government, and may not hold over time. For example, it has already been noted that the little research that exists at the municipal level has found in the past that large cities have lower voter turnout, and yet voter turnout was higher in ‘megacity’ Toronto. We have advanced a plausible explanation for why that might have occurred, but the conflicting evidence also urges caution from both a comparative and temporal perspective,

It is usually an ecology fallacy to use data generated at the groupor aggregate-level and attempt to draw conclusions about individuals. For example, if neighborhoods with high rates of unemployment also have high crime rates, one cannot conclude that the unemployed people in neighborhoods are committing crime. However, it is accurate to state that there is a higher incidence of crime in these neighbourhoods (this is a simple observation of fact) and all we have suggested so far is that wards with a greater number of renters or mobility in residency, and wards with a high number of visible minorities, have lower turnout. As for the extrapolation that these groups might be the specific ones being disproportionately disenfranchised, this is probably a reasonable assumption since the correlates are high, the wards are somewhat homogeneous and there is strong theoretical and intuitive justification for what might be causing the fluctuations in voter turnout along socio-economic lines. Nevertheless, caution is also urged.

One must also be cautious about taking findings at the municipal level and extrapolating to the provincial and federal levels. We have earlier suggested that the larger federal and provincial ridings might be masking the impact of SES factors on voter turnout in Canada. While this is likely true (and there is much anecdotal evidence to support this statement), it is also true that lower voter turnout can accentuate disparities. In other words, at the municipal level, where voter turnout is only in the 30-40 percent range, it is more likely that upper income or higher education will have a more dramatic impact on the election (something picked up first in the voter turnout figures) than they will have in a federal election where turnout is fairly high and where persons from all classes and income groups become mobilized. While voter turnout at the federal level has dropped from the post World War II average of 75 percent, it is still at the cusp of 60 percent, which would tend to indicate that SES differences might be mitigated by higher turnout, though even in these cases it is likely that economic factors are disproportionately impacting on voter participation.

In spite of these cautions, the results of this study are particularly disturbing. Voting is a right. It is even enshrined in section 3 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. While it is accepted by many people that rights are subject to individual choice – in other words a person has the right to vote or not vote since an abstention is in some ways equally a vote (which is the common argument against introducing compulsory voting in Canada) – if that right is not freely accessible to all members of society, then the legitimacy of the government, the fairness of the system and the equality of the society come under suspicion.

Clearly there is evidence that persons of lower income and less education, people who are renters and frequent movers, and persons who are visible minorities, new Canadians and non-primary English speakers, are voting less, at least in Toronto elections. This has to be troubling for the municipal government collectively and for the councillors who, once elected, will want to lay claim to a mandate from ‘the people’. The relatively low voter turnout at the municipal level frequently poses challenges for local politicians to claim a mandate, but the standard political response to media questioning about their legitimacy is that the ‘voters had a choice’. If there is evidence that some voters are systemically disenfranchised because of race, income or education, then the validity of that claim becomes circumspect.

There are two steps that could be undertaken that would instantly increase, perhaps even double, turnout at the municipal level, and these would be to:

In addition, there are a number of steps that can be undertaken to address the specific problems arising from this new evidence:

As pointed out earlier, the implications of this evidence make the lack of similar findings at the federal and provincial levels suspicious. We have noted that greater voter turnout and larger ward size might conspire to either mask or partially eliminate the impact of these factors on voter participation. If it is the former, this is particularly troubling, especially since its existence is likely known by political strategists and candidates and just not seen by the public, the media and academics.38 Therefore, more research needs to be done on how SES factors might impact at the strata of federal and provincial elections. An examination of voter turnout at the polling station level (as opposed to the larger riding level where multiple communities are consolidated) would quickly shed light on how social and economic differences might be impacting elections, and any impact that shows up in voter turnout would be a good litmus test of a larger impact on electoral influence.

Turning to the issue of merger politics and the broader issue of representation, there are a number of disturbing issues raised by the virtual stranglehold that incumbents have on municipal politics and that regional councillors have on merger elections. Any steps taken to obtain higher voter turnout overall (through something like compulsory voting) will undoubtedly change the dynamics of municipal elections. In addition, several steps can be undertaken to level the playing field, and thereby open up municipal politics to women and minorities in particular:

There does seem to be a ‘disconnect’ between the voters and their megacity government, though not exactly in the way predicted.

Contrary to expectations, voter turnout appears to have increased as a result of merger. This may be due to the increased attention that politics in a megacity generates, specifically the campaign for megamayor, which seems to have more influence on voter turnout than the excitement generated by local campaigns. The fact that the mayor of Toronto is directly elected by more voters than any other elected official in Canada and that most of Canada’s media is concentrated in Toronto, would certainly contribute to mobilization.

However, voter turnout is still below 50 percent. More importantly, voter participation at the municipal level is not uniform. Marginalized communities are being disproportionately disenfranchised in Toronto politics either because of administrative barriers like the voters’ lists, the campaigns of the candidates themselves or the complexity and size of the megacity, its wards and issues.

That higher income people might be somewhat engaged in municipal politics is expected given the way municipalities are funded and the decisions municipalities have the power to make. But property issues, such as taxes and zoning, are not the only responsibilities of municipalities. Some provinces have increasingly downloaded services to this lower level of government (one of the most significant being welfare in Ontario). An imbalance in participation along socio-economic lines means that certain groups are not having a full say on which people and policies can materially impact on their lives.

The sheer number of incumbents running in a merger election results in a virtual shutout of newcomers to municipal politics. And incumbency at the regional level seems to give a candidate a distinct electoral advantage in that initial merger election. What is more, incumbency continues to be an overwhelming advantage for electoral success in a megacity following merger. All this points to the likelihood that in the larger and more complex wards of a megacity the benefits of incumbency, such as name recognition, access to resources and the ability to mount a campaign in a large ethnically diverse urban setting, are formidable advantages.

The fact that incumbency is such an advantage to electoral success in Toronto may be of legitimate concern to women and minorities who are currently underrepresented at every political level. If new candidates are unable to break into municipal politics, it is unlikely that imbalances will be corrected any time soon, particularly if the early indication that attrition rates are lower in the megacity turns out to be a reality. This can have even larger implications given that municipal politics has frequently been the avenue by which women and minorities obtain the experience and credentials to break into higher office.

It is even possible that this might be contributing to socio-economic disparities in voter participation. If certain segments of society do not see themselves represented in government, they may feel less connected to that government, which in turn may make them less willing to vote, which might discourage others from seeking office, and so on.

A decade after merger it is clear that there are representational implications to the creation of a megacity. Whether or not there is a directional trend remains to be seen.

Yet in spite of the troubling undercurrent revealed through these findings, it is within government’s ability to take remedial steps. The changes suggested in this paper range from the administrative to the structural, but each are changes that could be helpful to municipalities beyond the merger context in order to further democratize the voting process.

The two most effective initiatives would be to introduce compulsory voting and to have political parties operate at the local level. Each would dramatically increase voter turnout – perhaps as much as double its current level – and they would create a more informed electorate that is better able to choose between alternative candidates.

If changes made in the name of cost savings and increased efficiency have created barriers to participation or even if natural systemic flaws are beginning to emerge, then it is incumbent on society to watch for these inadequacies and to take all necessary steps to correct problems. The ultimate goal for improving democracy should always be equality in participation and representation.

Bakvis, Herman (ed.). 1991. Voter Turnout in Canada (Research Studies of the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing, 15). Toronto: Dundurn Press.

Black, Jerome H. 2003. ìFrom Enumeration to the National Register of Electors: An Account and an Evaluationî, IRPP Choices.

Black, Jerome H. and Lynda Erickson. Forthcoming. ìWomen Candidates and voter bias: do women politicians need to be better?î, Electoral Studies.

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Schedule B, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982. iÌ€AppendicesiÌ‚, Revised Statutes of Canada 1985 (Ottawa: QueeniÌs Printer for Canada).

City of Toronto Act, 1997. Statutes of Ontario 1997, v.1., c.2. Toronto: QueeniÌs Printer for Ontario.

Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper.

Drummond, Robert. 1990. ìVoting Behaviour: Counting the Changeî, in Graham White, ed., The Government and Politics of Ontario. Scarborough: Nelson Canada.

Eagles, Munroe. 1991. ìVoting and Non-Voting Canadian Federal Electionsî in Herman Bakvis, ed., Voter Turnout in Canada. Toronto: Dundurn Press.

Erickson, Lynda. 1993. ìMaking Her Way In: Women, Parties and Candidacies in Canadaî in Joni Lovenduski and Pippa Norris [eds.], Gender Party Politics. London: Sage Publications.

Gidengil, Elisabeth and Richard Vengroff. 1997. iÌ€Representational Gains of Canadian Women or Token Growth? The Case of QuebeciÌs Municipal PoliticsiÌ‚, Canadian Journal of Political Science 30.

Globe and Mail. (Nov.) 1994, 1997, 2000 and 2003. Toronto: Thomson Publishing.

Hicks, Bruce M. 2002. iÌ€The votersiÌ tax creditiÌ‚, Policy Options 23: 4.

Higgins, Donald J.H., Local and Urban Politics in Canada. Toronto: Gage.

Karnig, Richard C. and B. Oliver Walter. 1983. ìDecline in Municipal Turnout: A Function of Changing Structureî, American Politics Quarterly 11.

Krashinsky, Michael and William J. Milne. 1986. ìThe Effect of Incumbency in the 1984 Federal and 1985 Ontario Electionsî, Canadian Journal of Political Science 19: 337-43.

Kushner, Joseph, David Siegel and Hannah Stanwick. 1997. ìOntario Municipal Elections: Voting Trends and Determinants of Electoral Success in a Canadian Provinceî, Canadian Journal of Political Science 30.

Madnusson, Warren and Andrew Sancton [eds.]. 1983. City Politics in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Marland, Alex. 1998. ìThe Electoral Benefits and Limitations of Incumbencyî, Canadian Parliamentary Review 21: 4

Milbrath, Lester. 1977. Political Participation: How and Why People Get Involved in Politics. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Sancton, Andrew. 2000. Merger Mania: The Assault on Local Government. Montreal: McGill-QueeniÌs University Press.

Stanwick, Hannah. 2000. ìA Megamayor for All People? Voting Behaviour and Electoral Success in the 1997 Toronto Municipal Electionî, Canadian Journal of Political Science 30.

Rust-DiÌEye, G.H. 1989. iÌ€Tiers are Not Enough: The Exercise of Upper-Tier Planning Responsibilities in the Greater Toronto AreaiÌ‚ [unpublished].

Tennant, Paul. 1980. ìVancouver Politics and the Civic Party Systemî, in Dickerson et al., eds., Problems of Change in Urban Government. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press.

Tindal, Richard and Susan Nobes Tindal. 1995. Local Government in Canada. Toronto: McGraw Hill Ryerson.

Toronto Star. (Nov.) 1994, 1997, 2000 and 2003. Toronto: Toronto Star Publishing.

Verba, Sidney and Norman H. Nie. 1972. Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. New York: Harper & Row.

For immediate distribution – November 9, 2006

Montreal – “Overwhelming” benefits of incumbency reduce chances for visible minorities in particular, says Bruce Hicks. On November 13, the citizens of the megacity of Toronto head to the polls to elect their municipal government. In light of this, the IRPP is today releasing a study that shows that specific groups – most notably low-income individuals and visible minorities — are much less likely to vote, which results in the underrepresentation of those populations on City Council.

Author Bruce Hicks (Université de Montréal), examines municipal elections in Toronto before and after the merger that created the megacity. His findings show that visible minorities, people with lower incomes and renters are significantly less likely to vote in municipal elections than other groups. This, coupled with the fact that incumbency gives candidates a distinct electoral advantage, creates a situation whereby the aforementioned groups – particularly visible minorities – are underrepresented on City Council. Given that 40 percent of Torontonians are visible minorities (expected to increase to over 50 percent in the next decade), the author notes that such inequities cast suspicion on the legitimacy of the government.

Contrary to expectations, overall voter turnout rose in the 1997 election, immediately following the merger, but has declined in every subsequent election. More importantly, Hicks’ data show that socioeconomic factors are strongly correlated with voter turnout in recent municipal elections:

The author’s findings also show that incumbent candidates have been increasingly successful in each election since the merger in 1997. When coupled with low voter turnout among those with lower incomes and among visible minorities, the overwhelming benefits of incumbency create a situation where certain groups are underrepresented on City Council.

To address the related problems of low voter turnout, the primacy of incumbents and the underrepresentation of minorities, Hicks proposes several prescriptions, among which are the following:

Are Marginalized Communities Disenfranchised? Voter Turnout and Representation in Post-merger Toronto, by Bruce Hicks, can be downloaded free of charge from www.irpp.org

-30-

For more information or to request an interview, please contact the IRPP.

To receive the Institute’s monthly newsletter via e-mail, please subscribe to the IRPP e-distribution service by visiting its Web site, at www.irpp.org.

Founded in 1972, the Institute for Research in Public Policy (IRPP.org) is an independent, national, non-profit organization based in Montreal.