Providing alternatives to hospital and institutional care for the nation’s expanding older population is one of the greatest social policy challenges Canadian governments are facing. Current long-term care policies assume that families (mostly adult children) are available to provide the care needed by their dependent elderly members, and that they have an obligation to do so. But in the next 30 years, the number of elderly Canadians needing assistance is expected to double, and considering that there will be a much smaller cadre of adult children, this will inevitably increase the need for more costly formal care.

This IRPP study is an overview of caregiving in Canada today, including the costs incurred by caregivers and the type and extent of public support they receive. Author Janice Keefe presents projections of future care needs and examines potential improvements in policy for income security programs, labour market regulation and human resource management in health and home care.

Informal caregivers are family members, friends or neighbours, most frequently women, who provide unpaid care to a person who needs support due to a disability, illness or other difficulty, sometimes for extended periods. They bear substantial costs – economic, social, physical or psychological. For instance, they are likely to incur out-of-pocket expenses and significant lifetime income losses, and they commonly experience stress, social isolation and guilt. Such personal costs can negatively impact the caregivers’ economic security, health and well-being.

Canadian governments must re-examine existing public services and programs to ensure that they meet the care needs of the elderly, and to address the adverse consequences of unpaid caregiving. More specifically, informal caregivers should receive financial compensation, together with in-kind support such as home help, education and referral services.

At present, the status of caregivers vis-à-vis existing public policy and programs is ambiguous. More public support for caregivers would not only demonstrate greater recognition of caregiving, it would also reduce the need for formal care, delay institutionalization and relieve the cost pressure on the long-term care and health care systems.

Given the anticipated shortages of health care workers in Canada, competition for health care resources is expected to be fierce in the coming years. To recruit and retain home support workers in all sectors, whether in voluntary, for-profit or public organizations, working conditions must be enhanced. Key in this regard are compensation levels, education, training and clear quality assurance accountability structures.

Due to the coming of age of the very large baby boom cohort, providing long-term care for older people is probably one of the greatest challenges governments face. Indeed, providing alternatives to hospital and institutional care for the nation’s expanding older population has been a key government concern for the past 15 to 20 years. Following a mid-1990s policy shift intended to curb escalating hospital and institutional care costs, much of this care in Canada has been provided in the community — to a large extent, by families. Annually, an estimated 1.2 million people in Canada use formal home care services (Carrière 2006), the majority of whom are aged 65 and older. With the exception of two federal programs — one for Veterans Affairs Canada and one for Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada — home care programs fall under provincial or territorial jurisdiction and generally provide services to citizens over the course of their lives.

Community care policies reflect the common assumption that families (specifically children) are available to provide care to their elderly members and that they have an obligation to do so. Indeed, research suggests that families do step in when needed (Gaymu et al. 2010). Caregivers of older persons usually want to take on this role and even prefer to provide such care themselves (Hollander, Liu, and Chappell 2009). Since community care is largely unpaid, this shift in health care policy has contributed to substantial savings for the public purse. In fact, it has been suggested that without it, the system would be unable to meet the care needs of older citizens.

It is not easy to assess the economic value of the contribution that informal (family and friend) caregivers are currently making or the costs of the formal care that would be required should informal care become less available. But the figures are certainly high: Hollander, Liu, and Chappell (2009), for instance, report that the market value of the contribution of Canada’s informal caregivers was between $24 and $31 billion in 2007, accounting for 1.6 to 2.0 percent of Canadian GDP.ggg1 In the short term, there are, structurally at least, many family caregivers available. In the longer term, we need to reconsider the expectation that family will continue to be available to the same extent. Changes in family structure caused by increased divorce rates and a decline in fertility rates, as well as increased labour force participation among women and geographical mobility, have created new challenges in providing informal care for older Canadians.

Since baby boomers are now entering a stage in their life cycle when they will need more care, it is opportune to examine whether family caregivers will be available to them. Although many may not currently have the care needs they can be expected to have 10 to 15 years from now, we must take a proactive approach to Canadian caregiving policy. Using Statistics Canada’s LifePaths microsimulation model (Statistics Canada 2009), in this paper I will assess both the demand for care among the aging cohort of baby boomers and the likely supply of informal caregivers. This paper draws on three of my programs of research: financial support policy for caregivers, projecting the care needs of older Canadians, and planning for the human resources needed to meet the care needs of older Canadians. This research has resulted in several publications, which are referred to throughout this study.

I first provide a brief overview of the role of family and friend caregiving in Canada today and the personal costs associated with elder care. In the second section, I report on projections of the likely future demand for, and supply of, caregivers for older Canadians, using three levels of disability scenarios. The findings are that in the longer term (post-2031), when the baby boomers have begun to pass the age of 85, a much smaller cadre of adult children will be available to provide informal care.

Next, I discuss the public policy implications of the findings. I first assess how Canadian caregivers of older family members are currently supported by their governments and how Canada compares to select other countries. Since demographic shifts in family profile will inevitably fuel the need for formal paid caregivers, and since a shortage of such workers is already evident across Canada, the discussion then turns to formal care policies, including a comprehensive human resource strategy directed to these formal caregivers. Potential avenues for improvement are discussed within three policy domains: income security, labour and health/home care human resources.

Caregiving is a complex activity, and it is important to clarify the terms we use to discuss it prior to addressing related policy challenges and solutions. “Caring” refers to the “mental, emotional, and physical effort involved in looking after, responding to, and supporting others” (Baines, Evans, and Neysmith 1999, 11). “Caregiving” refers more to the doing of the caring work — the tasks and type of supports provided. It has been assessed in different ways: by the types of tasks performed; by the frequency with which they are performed; by the scope, intensity and duration of the tasks; and by the relationship of the caregiver to the care receiver.

In examining policy to support caregivers, I propose a broad definition of “caregiver” — one that is used in many provincial and national population surveys. A “caregiver” is a member of the immediate or extended family, a friend or a neighbour who provides support, care and assistance, without pay, to an adult or child who is in need of support due to a disability, mental or chronic illness, life-threatening illness or temporary difficulty. For the purposes of this paper, “caregivers” are not paid workers such as home care workers, nurses or allied professionals. Salient to the definition here of “caregiving” (as opposed to “help”) for older Canadians is that it addresses the older person’s long-term need for formal or informal support. This paper looks at older Canadians who, because of a long-term disability or chronic illness, require assistance, but the focus will be on those who provide that assistance.

According to the 2007 Statistics Canada General Social Survey (GSS) of caregivers, 2.7 million Canadians aged 45 and older provided care to an older person with a long-term health condition or physical limitation in the previous 12 months (Cranswick and Dosman 2008).2 The number of caregivers had increased by about 670,000 from the 2002 survey. Of caregivers aged 45 and older, 57 percent were women and 43 percent were men (Cranswick and Dosman 2008). Not surprisingly, caring for an older close relative was the most common caregiving relationship, with 6 out of every 10 caregivers caring for a parent or parent-in-law. Interestingly, 14 percent of caregivers were friends, and 5 percent were neighbours of the person they were caring for (Cranswick and Dosman 2008), supporting the claim that a great deal of care is being provided by people outside of the immediate family structure (Rajnovich, Keefe, and Fast 2005).

Research consistently estimates that between 70 and 80 percent of the care given in the community to older adults is provided by family and friends (HeÌbert et al. 2001; Lafrenière et al. 2003). However, GSS data report that fewer than 1 in 10 caregivers are the spouse of the care recipient (Grignon, forthcoming). Analysts of the GSS note that spousal caregivers may be fewer in number than expected because they may not identify themselves as such (Cranswick and Dosman 2008). When available, spousal caregivers tend to provide more care than other caregivers (Keefe et al., forthcoming). Also important is the fact that among those aged 65 and older, the proportion of spouses will naturally be lower than the proportion of adult children. Not all seniors have spouses, and those currently over 65 tend to be parents of baby boomers and by definition have more children. Nevertheless, almost 10 percent of female and more than 8 percent of male caregivers are 75 or older (Rajnovich, Keefe, and Fast 2005). Clearly, older people are not only care receivers but also caregivers (Keating et al. 1999). These caregivers may also be dealing with their own disabilities or chronic illnesses and have their own care needs.

Caregivers provide a broad range of services and supports. These can be organized into the following four overlapping categories (Armstrong and Kits 2001):

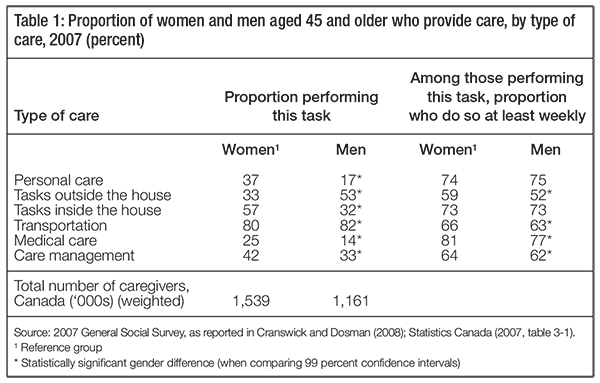

Table 1 provides detailed data on caregiving activities in the first three categories among Canadians aged 45 and older. Less detailed information is available on social and emotional support. In all categories of assistance except transportation and care outside the home, a significantly higher proportion of women provided the assistance than men. However, among those performing each task, gender differences between men and women were less pronounced.

In previous surveys — the 2002 GSS, for example — the number of hours spent providing assistance could be calculated. Data reported by Statistics Canada indicated that among caregivers aged 45 to 64, women spent almost twice as many hours on average per month providing assistance as men (30 hours per month, compared to 16); among those aged 65 and older, the gap narrowed somewhat (33 hours per month, compared to 21) (Stobert and Cranswick 2004).

Recent analyses of 2007 data confirm these gender differences and show that the amount of care provided is increasing (Fast et al. 2010). In 2007, female caregivers aged 45 and older spent an average of 11.9 hours per week providing care to their main care receiver, compared to 7.4 hours for male caregivers. If we look only at employed caregivers, their involvement was still considerable. Stobert and Cranswick (2004) found that these numbers were not much lower for employed caregivers: employed women spent 26.4 hours a month and employed men spent 14.5 hours per month providing care. These authors argue that the disparity between the amount of care provided by men and by women is related to the kind of care work performed. Women are significantly more likely to take responsibility for housework and personal care, as well as assisting with the management of care arrangements. Men may help with these tasks, but they are significantly more likely to take responsibility for home maintenance and transportation (see table 1).

The tasks that women caregivers are more likely to perform are personal and scheduled — preparing meals, accompanying the care recipient to appointments and administering medications. Cranswick and Dosman assert that “The time-specific nature of certain tasks is likely to add burden and stress to caregivers” (2008, 50).

Tasks typically performed by men, such as house maintenance and outdoor work, are not as time-sensitive and can be performed without necessarily altering the care provider’s schedule (Cranswick and Dosman 2008). Consequences of caregiving such as increased stress are discussed in the section on personal costs for caregivers.

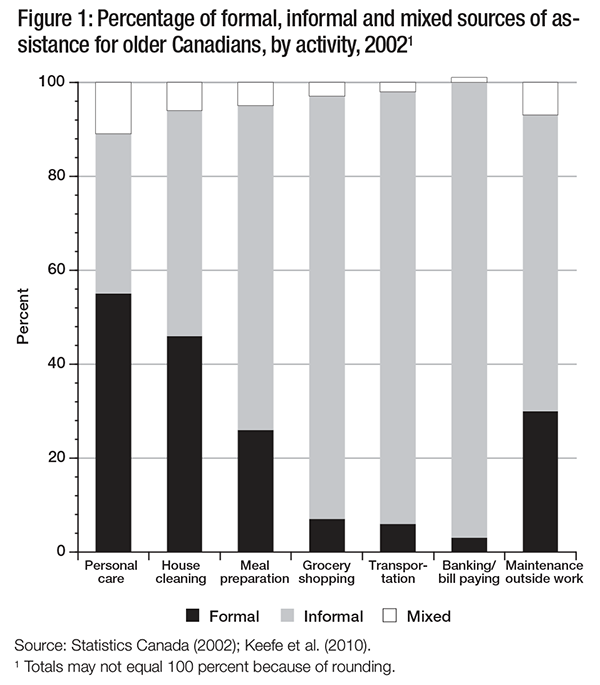

When the perspective of the care receiver is analyzed, a more complete picture of all sources of assistance, including formal care providers, emerges. Figure 1 presents the distribution of all sources of support provided to older persons in each activity type and enables us to determine whether certain activities are more likely to be supported by formal or informal sources. Findings confirm that certain activities — such as banking and bill paying, grocery shopping and transportation — are addressed through informal support: 11 percent or less receive any formal support. For personal care and house cleaning — and, to a lesser extent, meal preparation — formal support is very important.

Most older persons with disabilities or chronic illnesses receive support from their informal support networks — mainly family, but also friends and neighbours (Carrière et al. 2007; Kaye et al. 2006; Fast et al. 2010). Informal caregivers are increasingly being recognized as making a significant contribution to individuals, communities and society in Canada and internationally. But since they are often employed in the labour force, most bear some costs and consequences — economic and noneconomic — related to caregiving.

Economic costs include direct expenditures on services, equipment or supplies, as well as the loss of income and benefits from current and future employment. For instance, caregivers may change their work patterns to make themselves available to provide care; they may reduce their hours, take days off, arrive late or leave early, or take a leave of absence. Consequently, they may be turned down for raises and promotions, or they may have to refuse career-related opportunities, such as additional training or special projects, and promotions because they cannot take on the additional time or responsibilities due to their care work. If a caregiver has to reduce her working hours or quit her job in order to provide care, she could also lose many employment-related benefits, such as extended health care, life and long-term disability insurance, and private and public pension benefits (Fast, Eales, and Keating, 2001).

According to a pilot study conducted by the Metlife Mature Market Institute (1999) involving a small sample of high-intensity caregivers, a caregiver can expect a lifetime income loss of $659,139, including earnings, social security and pension losses. The economic consequences of caregiving are of particular concern for women. Recent research (Metlife Mature Market Institute 2006) has shown that they are more likely than men (7 percent versus 5 percent) to leave work to provide care; but both genders are equally likely to retire early to provide care to an older family member. In the United States, an estimated 101,000 women leave their paid employment to provide care each year. When women leave the workforce to provide care, this has a large impact not only on their personal finances but also on the economy: the estimated labour replacement cost to business is over $1.5 billion annually (Metlife Mature Market Institute 2006).

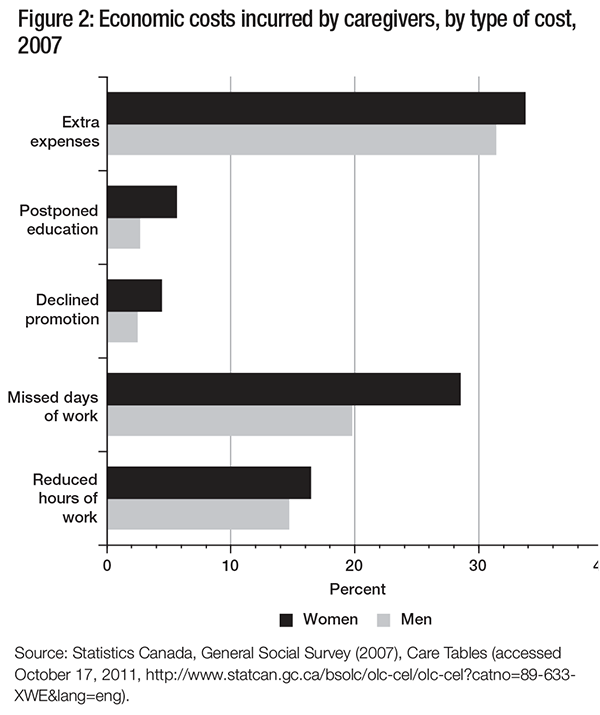

The gender dimensions of caregiving are also related to a decrease in women’s economic autonomy within the household. Caregiving is often treated as a natural extension of women’s kinship responsibilities (Keefe and Rajnovich 2007), and support policies for caregivers can bolster this assumption, perpetuating gender divisions of labour and inequality within households. Furthermore, women who provide unpaid care and do not participate in the labour market must often rely on a spouse for economic assistance (Keefe and Rajnovich 2007). Not only does this expose them to the challenges of having a low income, but, as they age, it can make them dependent on their spouse’s pension or on government programs such as Old Age Security or the Guaranteed Income Supplement (Townson 2000). Figure 2 summarizes the main economic costs reported by Canadian caregivers in 2007, by gender.

As figure 2 makes apparent, incurring extra expenses as a result of caregiving was the cost most commonly reported by caregivers; it was experienced by 33.7 percent of women and 31.4 percent of men. Guberman (1999) notes that these out-ofpocket expenses include not only those one would normally expect — such as care services, adaptive equipment, medication and home modifications — but also expenses that are less easy to identify or calculate. For example, in order to save time, or because they cannot leave the care receiver alone, caregivers may use services such as fast food or grocery delivery.

A study conducted by Health Canada in 2002 found that 44 percent of family caregivers paid out-of-pocket expenses; 40 percent spent $100 to $300 per month on caregiving, and another 25 percent spent in excess of $300 (Health Canada 2002). Distance is also a factor in calculating out-of-pocket expenses. Long-distance caregivers spend an average of $392 per month on travel and direct expenses related to the care receiver (Metlife Mature Market Institute 2004). These additional costs associated with caregiving are in excess of formal care services and contribute to the financial strain placed on caregivers.

Only a small minority of caregivers (and again, more women than men) reported that they had postponed their education or declined a promotion, but many did identify costs associated with employment. Gender differences were particularly noteworthy among caregivers who had missed days of work as a result of caregiving, an experience shared by 20 percent of male and almost 30 percent of female caregivers. There may also be a link between the types of care provided and employment-related economic costs. In an analysis of data from the 2002 GSS, Walker (2005) found that caregivers who provided more personal care were more likely to change their work patterns, and that women caregivers were more likely to quit their jobs. As mentioned earlier, missed days and reduced hours of work also have longer-term consequences for women’s economic security, as they may affect pension contributions and retirement savings (Keefe and Medjuck 1997).

In addition, caregivers may face noneconomic costs related to their caregiving responsibilities. In 2007, 57 percent of caregivers reported that they were coping “very well” with their caregiving responsibilities, and 42 percent reported that they were doing “generally okay” (Cranswick and Dosman 2008), but a significant number had to deal with social, physical and psychological costs (described in greater detail later in this paper). And, as with economic costs, a larger proportion of women than men report facing noneconomic costs (Cranswick and Dosman 2008).

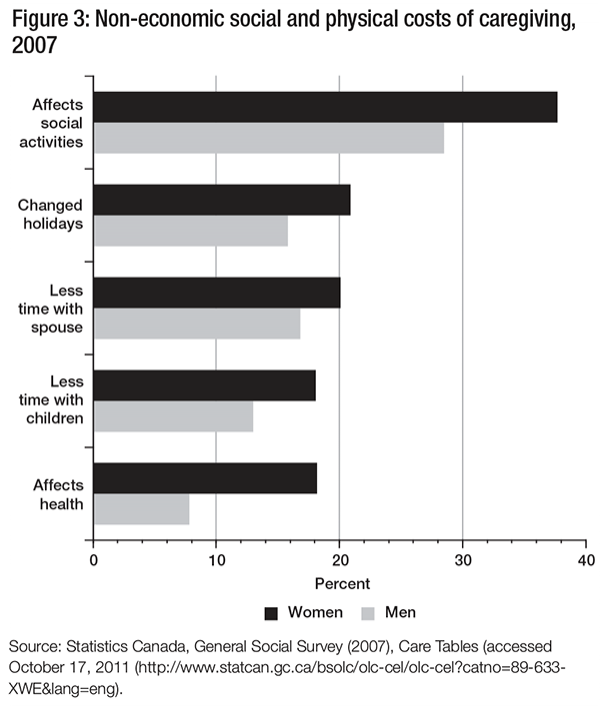

Data from the 2007 GSS presented in figure 3 show how caregiving responsibilities have affected caregivers’ social activities and compelled them to change their holiday schedules, again with relatively significant differences between men and women.

In-depth interviews with caregivers reinforce these population-based findings (Gahagan et al. 2004). For instance, caregivers often give up social activities and leisure time in order to provide care (Keating et al. 1999). They have difficulty maintaining social networks and lose friendships, either because they do not have the time or energy to maintain them or because their friends stop visiting. Caregiving responsibilities also have an impact on family dynamics. Both men and women report that their caregiving responsibilities cut into the time they spend with their spouses and children, although this affects women more than men (Cranswick and Dosman 2008).

The physical consequences of caregiving also differ according to gender. When asked about their overall health, more than twice as many women (18 percent) as men (8 percent) reported that caregiving had affected their health. Caregivers also express a range of emotions, concerns and desires related to their caregiving responsibilities. For a large majority, these are positive. For instance, more than 70 percent of both men and women caregivers reported that caregiving had strengthened their relationship with the care receiver (Rajnovich, Keefe, and Fast 2005); but many caregivers also reported having negative feelings, and an examination of these reveals more about the caregiving experience and its hidden costs.

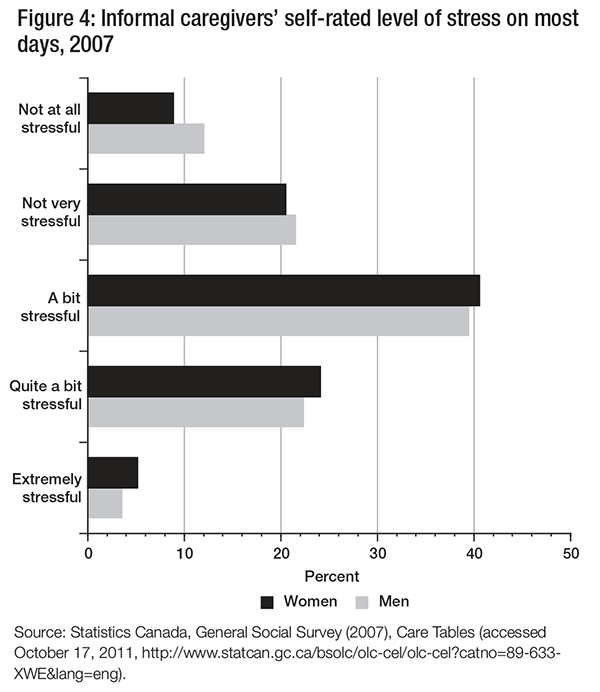

Stress has been identified as a prime concern for caregivers. According to data from the 2007 GSS, stress is common among both male and female caregivers: 61.9 percent of men and 64.7 percent of women reported that providing care for someone with a long-term health condition or physical limitation was “a bit stressful” or “quite a bit stressful,” and relatively few indicated that it was “not at all stressful” (12.1 percent for men and 8.9 percent for women). At the other extreme, only 3.6 percent of men and 5.2 percent of women reported that it was “extremely stressful” (see figure 4).3

Feelings of guilt pose another difficulty. Caregivers feel guilty because they cannot do as much as they think they should due to competing demands on their time and energy. Many think they should be more efficient or have better caregiving skills (Keating et al. 1999). In 2002, more than 10 percent of both men and women reported that they nearly always felt that they could be doing better, and more than 20 percent nearly always felt that they should be doing more. When we include those who said they sometimes had such feelings, we see that the majority of caregivers experienced feelings of guilt (Stobert and Cranswick 2004). Caregivers also wished that others would take over from them or help them more. Stobert and Cranswick (2004) found that among caregivers age 45 to 64, fewer than one in five (17 percent) received help when they needed it. Any assistance they did get came largely from other family members (82 percent); a much smaller proportion (16 percent) was paid help from private or government sources.

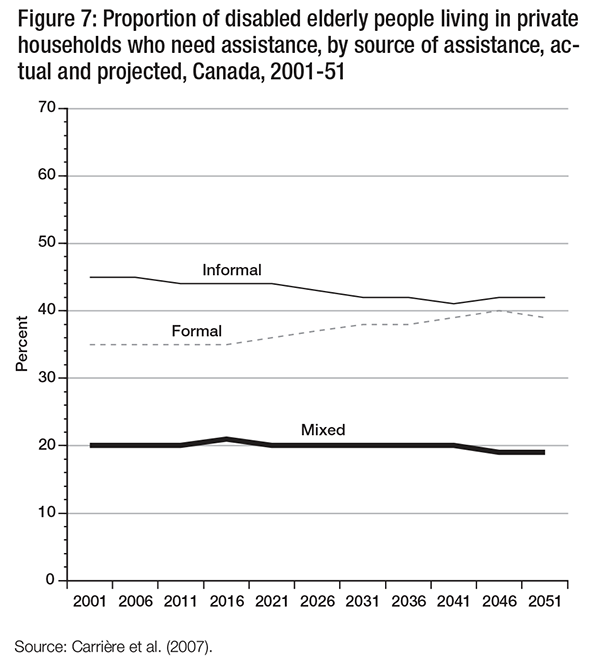

Family and friends provide the majority of care to older people in the community (Carrière et al. 2007). Even when older people receive formal services, a higher proportion of those services are provided via informal networks. Indeed, increases in formal services are often accompanied by increases in care provided by family and friends. Changes in the availability of adult-child caregivers in the future may thus mean that a greater proportion of this support will need to be delivered through the formal system, whether that care is publicly funded or purchased in the marketplace (Carrière et al. 2007).

How does the fact that baby boomers have had fewer children than previous generations determine the level of care they can expect to receive in the medium term? Is our current reliance on informal sources of caregiving appropriate in the medium term (the next 10 years), or in the long term (10 to 25 years from now)? One factor to consider here is that the baby boomer cohort is healthier than the current generation of seniors, so their care needs could be less. In other words, in order to plan efficiently to deal with the care needs of aging baby boomers, we need to examine not only the supply of caregivers but also the demand for them.

To address this issue, my colleagues and I (Carrière et al. 2008) engaged in an ambitious research program using Statistics Canada data and a microsimulation model to project the supply of, and the demand for, support for older people between 2001 and 2031. First, we analyzed data from the National Population Health Survey (NPHS) and the GSS using a series of regressions to advance an understanding of the level of disability and its impact on support network usage. Factors influencing disability levels were obtained from the NPHS (regression 1). Factors influencing the need for assistance and the receipt of assistance (age, number of children, level of disability and province of residence) were obtained from the GSS (regressions 2-3). Next, factors influencing living arrangements (regression 4) and the source of assistance (informal support versus formal support, or both formal and informal) were examined and stratified by gender (regression 5).

In order to assess the complexity of the need for future home care services, these results, along with changes in disability among older persons and changes in family structure (presence of children and of spouses), were applied to the results of the population projections using Statistics Canada’s LifePaths microsimulation model.

LifePaths is a dynamic longitudinal microsimulation model of individuals and families. As explained by Statistics Canada, Lifepaths “simulate life histories: taking account of birth, death, immigration status, inter-provincial migration, marital history (including common-law unions), educational history, employment history and the birth and presence of children at home” (Statistics Canada 2009). The model is used to analyze, develop and cost government programs that have an essential longitudinal component, in particular those that require evaluation at the individual or family level. It can also be used to analyze a variety of societal issues of a longitudinal nature, such as intergenerational equity.4

In our study on caregiving, my colleagues and I first ran the Lifepaths model to obtain population by age, sex, education level, region of residence, marital status, age of spouse, place of birth and number of surviving children (Carrière et al. 2008). We also determined who lived in an institution and who lived in a private household. Only the latter population was used in the statistical analysis, as, by definition, home care is provided to those who live in private households. Based on these data, we then applied the parameters obtained from regressions 1 through 5 to project disability status levels, need for assistance, living arrangement, receipt of assistance and source of assistance up to 2031. In this way, the numbers of people having certain characteristics were estimated. These data were extended through 2051 on the assumption that women’s life expectancy will increase, but less rapidly than men’s.5

At the outset it is acknowledged that these projections are limited in two ways. First, they are based on structural changes in the availability of children and spouse and the way in which these family members currently provide care. In the future, friends and neighbours may become more involved in the provision of care beyond current patterns of support, and this would affect the projections. Second, the projections are based on the assumption that formal systems of support will continue to offer the same services and that older persons will remain willing to receive either public or private home care services rather than rely on informal sources of support.

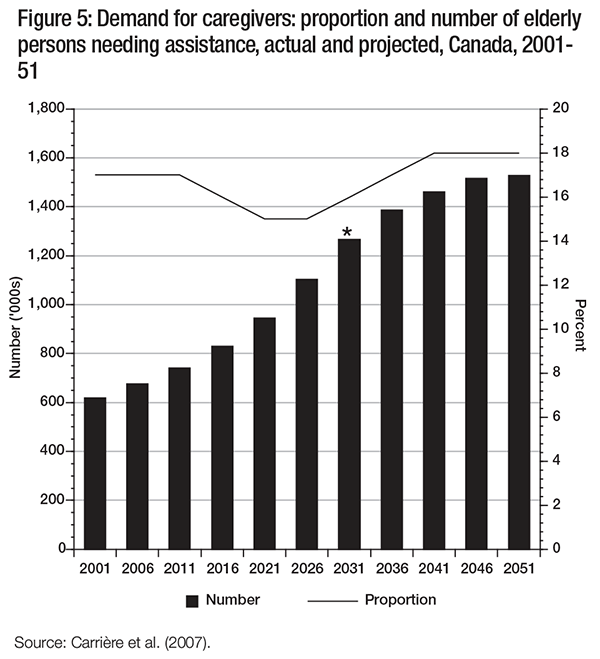

The results of the analysis are presented in three parts: demand, supply and source of assistance. In terms of demand, the projections indicate that the number of elderly Canadians needing assistance will double in the next 30 years and plateau around 2046 (see figure 5). The projection period was extended to 2051 to estimate the full effect of the baby boomer cohort reaching the age of 85. Since, as we are well aware, the policies and behaviours that we assume will continue over the next 20 years will be different after 2031, a star is placed at 2031 on figure 5. Data demonstrate that the proportion of older people needing assistance will decline between 2011 and 2026 due to the influx of younger cohorts of baby boomers entering the age group of 65 and over. Yet the number of older people almost doubles in this period.

In terms of supply, it is expected that, as the gap in life expectancy between women and men narrows, there will be a slight decrease in the proportion of people living alone. The potential for an increase in the family network could, according to Légaré and Décarie (2008), lead to reduced risks of dependency on formal sources of assistance. This points to a potential source of informal support within households (Keefe et al. forthcoming; Carrière et al. 2008). Walker, Pratt, and Eddy (1995) found that spouses who live together tended to rely more on one another for needed assistance than social services. Since people who live alone are more likely to use formal services (Chappell 1985; Grabbe et al. 1995), a decrease in the number of people living alone could have a significant impact on projections of the need for future home care services.

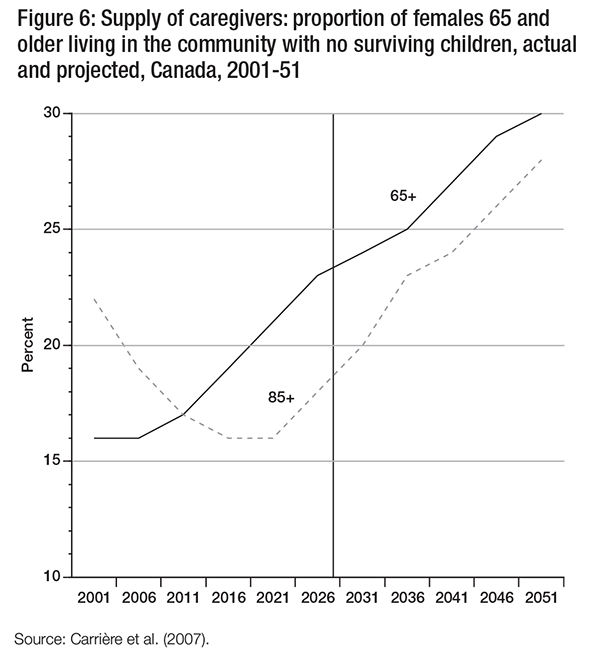

However, a decline in the availability of children is a major cause of concern, particularly since, as outlined earlier, many caregivers are adult children. Figure 6 presents the proportion of females 65 and older living in the community who have no surviving children, by age. Among females aged 65 and over, the proportion without any surviving children increases from 16 percent in 2001 to 24 percent in 2031 (and 30 percent in 2051). Close to one in four elderly women may be without a surviving child by 2031.

These data represent the demographic reality of the baby boom cohort moving through the years in which they are more likely to have an elderly parent or parent-in-law in need of assistance. Indeed, in the short term (until 2016), we see that the proportion of women 85 and older who have no surviving children is projected to decline from 22 percent to 16 percent. These parents of baby boomers are more likely to have surviving children. In the longer term, however, the likelihood of women having no surviving children increases steadily (see also Carrière et al. 2008). These demographic changes affect the availability of informal support and the proportion of disabled elderly who will need to rely on formal sources of support (figure 7).

Recent analyses of the amount of support children provide to older persons in need of assistance confirm the centrality of their role. Women aged 75 and older who live in the community are more likely than men to receive long-term assistance from their adult children: nearly 50 percent of the total hours of assistance received were provided by adult children. In absolute terms, this represents close to 1.2 million hours of assistance per week (Keefe et al., forthcoming). This said, a study conducted in Quebec of caregivers of the baby boomers indicates that their expectations differ from their parents’ when it comes to their own aging. They value their autonomy highly, and they expect public programs to help them support it as they age. They refuse to become a burden to their families (Blein et al. 2009). Given such expectations, and the projected reduction in the number of surviving children, we need to consider how the care now provided by adult children can be replaced in the future (Keefe et al. 2011; Keefe et al. forthcoming).

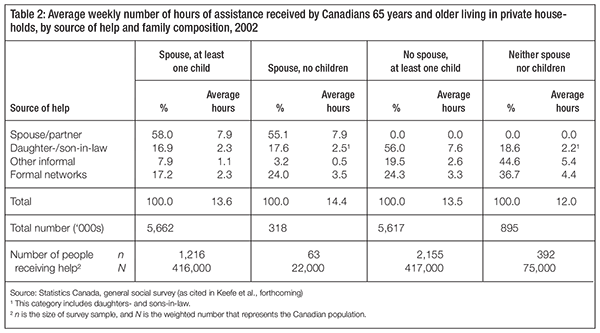

Table 2 shows the average number of weekly hours of assistance received by Canadians aged 65 and older, according to family composition. In terms of informal care, family constitutes a significant source of assistance for older persons, with adult children as the main providers. This is noteworthy, given Vézina and Turcotte’s (2010) findings that only 13 percent of adultchild caregivers aged 45 and older reside with their assisted parent, and that 22 percent of these caregivers live more than one hour away from their parent. Table 2 also shows that other informal support networks provide essential assistance to older Canadians who have neither spouse nor surviving children, constituting over 44 percent of the average number of hours of assistance per week. Despite the absence of surviving children, elderly persons within this group continue to receive assistance from daughtersand sons-in-law, constituting almost 19 percent of the total assistance received (Keefe et al. forthcoming).

Table 2 further indicates that, for families in which both a spouse and surviving children are present, formal network providers — such as marketplace providers or state-run services — deliver about 17 percent of care. In the absence of either spouse or children, formal supports provide approximately one-quarter of the total weekly hours of care. Older persons living in the community with neither spouse nor surviving children receive 37 percent of the assistance received is provided through formal support. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that older persons with neither spouse nor children receive less assistance on average per week. One explanation is that those who need more assistance may not be able to remain in the community and therefore live in nursing homes. Reductions in the size of the potential informal care network (because of an increase in the proportion of older people without surviving children) will likely lead to increases in the use of formal services (Carrière et al. 2007).

The research results suggest that the number of elderly Canadians needing assistance will double in the next 30 years, and this, combined with a decrease in the availability of informal support, will result in a relative and absolute increase in the use of formal support. Moreover, these demographic trends will be compounded by the characteristics of the elderly population. For example, highly educated people are more likely to access formal services. Consequently, the increasing levels of schooling among the older population will have a significant effect on the use of formal services over the next decades (Gaymu et al. 2010; Guberman et al. 2006).

In the short term, we know that among the very old (85 and older), who are most likely to need care, there are those with children available to provide that care. But even if adult children exist, other social factors may affect the amount of home care support older persons receive from family members. For instance, women have increasingly participated in the labour market over the previous three decades, challenging traditional expectations of their availability to provide care. Other factors include the geographic proximity of adult children, the expectations of stepchildren in blended families and the challenges of providing care to parents living in separate locations. Also, older parents’ expectations of their children may be very different from those observed in the recent past (Keefe, Légaré, and Carrière 2007; Guberman et al. 2006; De Jong Gierveld and Dykstra 1997). For instance, Guberman and colleagues found that “People in the 70+ group have higher expectations of the targeted family member than those in the 45-59 year old group for many support activities: medical and hospital appointments, meals and house cleaning, bathing and dressing” (2006, 70). While it is unclear whether such findings are an age or a cohort effect, the spending practices of the baby boomer cohort tend toward a greater use of formal services in later life than the spending practices of their parents.

Thus, in terms of planning and providing adequate care for older Canadians who need assistance, there are both shortand long-term challenges. The next section explores the shortterm challenge of developing a system of support for informal caregivers.

At the outset, it is important to declare that the current system of supports for family and friend caregivers is limited and inconsistent; their role is not clearly acknowledged by public policy. In fact, there is not one system of support for family and friend caregivers in Canada. What we do have are disparate services and programs that vary across political jurisdictions (federal, provincial, regional and municipal) and policy domains (income security, health/continuing care and labour). These are delivered through a large spectrum of proprietary, not-for-profit and volunteer organizations. In addition, access to these services and programs varies significantly — it depends on who you are, where you live, who you are caring for and whether the care recipient agrees to get help.

Within Canada, most public home care expenditures are covered by the provincial and territorial governments (97 percent); the federal government is only responsible for a minority of constituents such as veterans and certain Native peoples (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2007). A 2007 report from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) reveals that long-term care programs, and services and support for caregivers, vary across provinces and territories, and wide disparities exist in investment in home care. For example, from 1994-95 to 2003-04, New Brunswick maintained the highest per capita expenditure in Canada, despite the fact that it did not have the highest share of the population 65 and older. This can be attributed to its comprehensive Extra-Mural Program, which addresses health throughout the life course and focuses on the maintenance and restoration of health within the context of people’s daily lives (CIHI 2007). Over the same period, Nova Scotia exhibited growth in home care spending largely due to the HomeCare Nova Scotia program. This program was established in 1995 to meet the needs and support the independence of Nova Scotians (CIHI 2007). According to the CIHI, the most established and comprehensive universal home care program in Canada is the Manitoba Home Care Program (CIHI 2007).

While it is acknowledged that caregiving policies are embedded in the broader context of long-term care policies, both home care and institutional care policies, it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide an in-depth analysis of the myriad programs across Canada that address the needs of the care receiver. I now focus on select policy options related to financial support and the in-kind services that constitute the bulk of programs related to caregivers and/or the care needs of older persons. Following a description and critique of how current policies affect family caregivers, and an examination of some foreign programs, I propose opportunities where policies can be enhanced or developed.

Financial support is a growing area of the policy domain of income security. In some countries, such financial support may be administered through, and assessed under, the umbrella of home and continuing care programs. Despite the emphasis in this paper on financial support, no one policy solution can be a panacea for all caregivers. Throughout this section, there is an implicit acknowledgement that caregivers are diverse: there is no one-size-fits-all policy. A fundamental principle of providing support to caregivers is that we must maximize choice and flexibility in addressing their needs.

In Canada, there is a tension between developing services to support individuals in need of care and developing services to support caregivers. The policy dilemma is whether to support demand (for example, what dependent seniors need) or increase the supply of resources necessary to meet caregivers’ needs.

A decade of research in this area reveals that most financial support policies in Canada have both economic and social objectives. Policies that have a social objective recognize the contribution of family members and the need to support them even though they would continue to provide care if financial support were not offered. Moreover, in such cases, the point is not necessarily to replace services — care receivers remain eligible for assessed support services and caregivers themselves can access respite care services. Financial support for caregivers is typically a symbolic gesture; it is not intended as a wage for care work. Policies that have an economic objective strive to reduce or delay institutionalization, or to reduce access to formal home care, for persons with assessed care needs. Offering support to family and friend caregivers can decrease the cost to the long-term care/health care system (Keefe, Légaré, and Carrière 2004).

Internationally, financial support is an increasingly widespread policy option. Reviews of international experiences indicate that other jurisdictions have used a wide range of approaches and policy instruments (Keefe 2004; Keefe and Fancey 2008; Keefe and Rajnovich 2007). Financial payment schemes provide some compensation for the economic costs incurred (for example, extra direct and indirect expenses, job loss, reduced income, lost opportunities for promotion or advancement); at the same time, they may represent public recognition of the value of family care work. These economic initiatives take different forms (direct or indirect), purport different rationales (social or economic), and operate within different social policy contexts and domains (for example, social security/income maintenance, health/home care services or labour).

We can classify financial support policies in three broad categories: indirect financial support, which entails delayed monetary support such as pension security or some forms of tax relief; direct payments, which include cash benefits in the form of an allowance paid directly to the caregiver (or to the care receiver to pay the caregiver);6 and labour policies, which provide employment leave and partial replacement of employment earnings to eligible caregivers (Keefe 2004). I will discuss indirect financial support policies first, as Canada has developed a number of policy instruments for them. Next, direct policies will be discussed, as they offer opportunities to expand Canada’s financial support to caregivers; finally, labour policies will be addressed.

At the national level, two types of policies have been developed — one linked to the taxation system and the other to the Employment Insurance program (which will be discussed later). Within the federal taxation system, there are five credits and deductions that caregivers can access: the caregiver tax credit, the infirm dependant tax credit, the transfer of a personal credit, the disability tax credit transferred from a dependant, and the medical expenses tax credit. Caregiver applicants cannot claim more than one of these credits or deductions in the same year. In March 2011, the government also tabled in its budget an additional family caregiver tax credit, but it was not adopted prior to the dissolution of Parliament.7 In June 2011, the federal government adopted a new Family Caregiver Tax Credit to be effective January 1, 2012. This is a 15 percent nonrefundable credit on an amount of $2,000 that will provide tax relief for caregivers of infirm dependent relatives, including spouses, common-law partners and minor children. This tax credit will supplement one the five existing credits that caregivers can access.

The caregiver tax credit introduced in 1997 is a nonrefundable tax credit to a maximum of $642 (tax year 2011). It is intended for co-residing caregivers of an adult dependant or elderly relative who meet relationship and income criteria. This credit is nonrefundable, which means that while it can be deducted from taxes owing, one must be paying taxes in order to receive the benefit. Many provinces have introduced similar nonrefundable tax credits for caregivers. The infirm dependant tax credit is available to caregivers who are supporting a parent, grandchild, sibling, aunt, uncle, nephew, niece, adult child or spouse/partner; the caregiver does not have to be residing with the care receiver. The maximum credit is reduced when the care receiver’s net income exceeds $5,702; it is not available if the care receiver’s net income is greater than $9,721 (Finance Canada 2011). Other tax instruments are detailed in the appendix.

These tax credits have been criticized on numerous grounds. First, they all provide minimal amounts of money (in the range of a few hundred dollars per year) and therefore do not adequately compensate the financial losses associated with caregiving (Keefe and Rajnovich 2007; Keefe and Fancey 1999). The tax credits are nonrefundable and, with the exception of the new family caregiver tax credit, caregivers cannot claim more than one credit in the same year. Those with no or low income — often women caregivers — do not have sufficient income to receive any financial support through these credits (Gaymu et al. 2010; Shillington 2004). Care-receiver income tests, co-residency criteria, and eligibility based on type of relationship between caregiver and care receiver also severely limit who can benefit from these credits (Fast, Eales, and Keating 2001; Shillington 2004).

These tax credits could potentially be enhanced. For example, they could be made refundable and distributed on a quarterly basis similar to the child tax benefit. Other policy instruments, such as pension dropout clauses for the Canada Pension Plan, provide opportunities for the federal government to enhance its role in supporting family caregivers. Modelled on the child care dropout clause, this proposed policy change would enable family and friends caring for older adults to reduce their work hours for a set period without reducing their Canada Pension Plan benefits. Essentially, during times of low-to-zero earnings, the pension dropout clause allows for the exclusion of up to 15 percent of an individual’s Canada Pension Plan contributory period in calculations of the average monthly pensionable earnings.

Keefe, Glendinning, and Fancey (2008) identify four specific models for directing financial support to caregivers according to who receives the support and for what purpose. They are consumer-directed personal budgets that allow older people to employ their caregivers; care allowances paid to the care receiver, who has complete freedom to decide how they are to be used; care allowances paid directly to the family caregiver; and payments to family and friend caregivers who substitute for formal service providers (Glendinning 2006; Glendinning, Schunk, and McLaughlin 1997; Jenson and Jacobzone 2000; Lundsgaard 2005).

Direct financial support to caregivers is intensely debated in the social policy literature, both in Canada (Keefe and Rajnovich 2007) and internationally (Holstein and Mitze 1998; Keigher 1991; Kunkel, Applebaum, and Nelson 2003-04; Ungerson 1997). This type of policy, in particular, raises questions about who is responsible for providing care to older people who need assistance. Confusion and tension about the responsibilities of family, government and society fuel fundamental debates over the development of such policy. For example, the appropriateness of state involvement in the provision of financial support for those who are caregivers for older people is questioned. Is this the best mechanism for supporting people caring for older friends and family? Is it in the best interest of older Canadians receiving care? Is the primary objective of such policy to support caregivers or to reduce costs? Prior to assessing the particular parameters and nuances of delivering financial support programs, I will assess the fundamental objectives of the policy to help inform the social policy debate.

Keefe and Rajnovich (2007) summarize the debates surrounding the introduction of money into the care relationship. First is the concern that governments are taking over responsibility for family care. As part of the debate over financial support policy for caregivers, countries must first decide what their role in, or responsibility for, providing care to dependent adults is and how this role/responsibility fits in with that of the family. The question of whether paying family caregivers would result in a major shift away from viewing caring as part of normal family responsibility reflects a “deep concern over tainting lines between the work we do for love and the work we do for money, between ‘care’ and ‘work’” (Kunkel, Applebaum, and Nelson 2003-04, 79). Keefe and Rajnovich (2007) point out that policies such as Germany’s long-term care insurance undervalue the role of informal caregivers because they cover only about one-third of the cost if clients choose the payment-for-care scheme rather than formal services.

Second is concern about the commodification of care in the research on family care responsibilities. Introducing money into family relations is thought to be problematic. It is argued that as family caregivers provide care out of love, offering payment for it will alter the quality of the relationship between caregiver and care receiver — and, generally, the nature of family relationships — creating emotional distance. Third is the concern that the introduction of financial support for caregivers is being curtailed by government due to its fear that caregivers will come out of the woodwork to claim their entitlement, leading to excessive use of resources (Keefe and Fancey 1997). However, this fear is shown to be generally unfounded when eligibility clauses are introduced and when other, similar policies are examined. Neither the caregiver tax credit nor the compassionate care policy (part of Employment Insurance benefits) have come close to the federal government’s targeted cost estimates (Keefe and Fancey 2005; Shillington 2004).

A fourth and final concern is that direct payments to caregivers may reinforce gender stereotypes. While such payments might improve the temporary financial well-being of the caregiver, many observers fear that women will increasingly be expected to provide the care, and this could help consign them to a lifetime of poverty. Moreover, if direct payments are provided to the exclusion of support services, then the caregiver may experience increased isolation and burden, as was observed in a study of two provincial programs in Nova Scotia (Keefe and Fancey 1997). First legislated in 1984, the Nova Scotia Life Support program financially compensated family members for the care of the frail elderly, while Nova Scotia In-Home Support offered a range of home help services to the elderly. In their comparison of the programs, Keefe and Fancey (1997) found that living arrangements (such as co-residence with the care receiver), the level of involvement in task performance and type of financial compensation increased the burden for women caregivers. To address these findings, they recommended greater recognition of women’s caregiving as labour and proposed that “Financial compensation should not be offered in isolation, it should be provided in conjunction with home help services” (Keefe and Fancey 1997, 274).

Despite these challenges, financial support is used relatively often to compensate family caregivers. Two countries, Australia and Germany, are highlighted here as they have different approaches to providing direct compensation to family caregivers: Germany has a national health care insurance scheme, and Australia has a universal allowance supplemented by an income-based support system for caregivers.

Australia has two cash benefit programs that pay caregivers directly: Carer Allowance and Carer Payment. Carer Allowance, established in 1999, is an income supplement program available to people who provide daily care to an adult or child with a severe disability or medical condition. A limited, nontaxable payment of $90 every two weeks, the allowance is intended to help with the extra costs associated with caring for a dependent child or adult (Howe 2001). Carer Payment (formerly Carer Pension) is an income support program targeting low-income caregivers. It provides a means-tested benefit (income and assets) to people who cannot work full-time because of their caregiving responsibilities. It is paid at the same rate as other social security pensions (Access Economics 2005), and its recipients may be eligible for other financial assistance, such as a utilities allowance or a telephone allowance.

In Germany, the home care domiciliary benefit was implemented in 1995 as part of the longterm care insurance system.8 The cash benefit is paid to the care recipient who has been assessed as having unmet needs; it is intended to offer a choice to the individual and sustain and support family caregiving.

The amount of the benefit the care recipient gets is based on the assessed level of care required. It is not income-tested. Assessed levels of care range from level 1 (at least 90 minutes of care every day) to level 3 (at least five hours of care every day). The value of these cash payments is about half the value of services provided in kind (Glendinning, Schunk, and McLaughlin 1997). The cash allowance is not treated as taxable income for either the care receiver (Glendinning and Igl 2009) or the caregiver (Wiener, Tilly, and Cuellar 2003).

Glendinning and Igl also note that despite the fact that its value is significantly lower than that of the direct services option, the cash allowance option is consistently chosen by between 64 and 82 percent of beneficiaries. It is believed that the vast majority of those choosing the cash allowance do so because they prefer to receive care from family and friends than from strangers (Glendinning and Igl 2009; Wiener, Tilley, and Cuellar 2003). There is a tendency, however, for clients to switch to in-kind or a combination of in-kind and cash when care needs increase significantly. For example, in 1998, 82 percent of beneficiaries at the lowest care level chose cash compared to 77 percent at the middle level and 64 percent at the very severe disability level (Wiener, Tilley, and Cuellar 2003).

These models offer interesting alternative mechanisms for supporting caregivers in Canada. Those implementing such direct allowance programs may face challenges related to financing the program, ensuring quality of service and administering the program. Indeed, Canada would need to overcome several obstacles in order to introduce such programs. For instance, attempts to broaden the Canada Health Act (CHA) to include care in the community (currently described as “noninsured”) would raise concerns that the sacredness of the public delivery of health care services enshrined in the Act was at risk. Thus, the prospect of developing a national health insurance program composed of caregiving services and allowance programs seems futile, at best. The Australian approach of direct payment to caregivers seems more attainable, yet it would require the agreement of the provincial and territorial governments. This would be no small feat in an era when the federal role in developing national health policies is being reduced.

The compassionate care benefit (CCB) was introduced in Canada in January 2004 as one of the benefits available under Employment Insurance, which is an employer-employee-contribution-funded program (Keefe and Fancey 2005). The CCB allows eligible employees to take up to eight weeks leave, including an unpaid two-week waiting period, to care for a dying family member at up to 55 percent of earnings, capped at $468 per week in 2011. It includes a benefit that falls under Employment Insurance legislation and job protection that falls under the federal and most provincial labour codes. Caregivers can continue to work while receiving the CCB, earning up to $75 per week or 40 percent of the weekly benefits, but any earnings in excess of that amount will be deducted from the benefits (Service Canada 2011).

The definition of “family” was expanded from “immediate family” to encompass a broader range of relationships, including that between a caregiver and a care recipient who considers the caregiver to be “like a family member” (Service Canada 2011). Most provinces have implemented complementary legislation that alters their labour standards acts to enable an employee to return to work following a period of unpaid compassionate leave.

It is important to bear in mind that this policy is embedded in a national employment insurance program, and as such it is oriented to a continued productive labour force. It aims to ensure the stability of workers’ lives, prevent unemployment and improve the functioning of the labour market (Keefe and Fancey 2005). The purpose of this policy, then, is to maintain the attachment of caregivers to the labour market when a family member contracts a catastrophic illness.

One of the criticisms of the CCB has been its low take-up rate. In Canada in 2003-04, 1,755 people claimed it, and, on average, claimants only used approximately 4.3 weeks or 30 days out of the 6 weeks available within a 6-month period (Keefe and Fancey 2005). The low takeup rate could be interpreted as a reflection of the fact that the program does not sufficiently consider the needs of caregivers. The two-week unpaid waiting period may also be an obstacle.

In a detailed analysis of paid leave policies for caregivers of critically or terminally ill relatives in five jurisdictions (Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, Japan and California), Keefe and Fancey (2005) conclude that Canada is not alone in having lower-than-anticipated usage. Even with well-established programs such as Sweden’s 1989 Care Leave Act, the number of paid leave users and the length of leave time used were lower than expected. Few evaluation results were available to assist in the assessment of this pattern, but we can make several observations.

Delivery mechanism and eligibility criteria. Jurisdictions offering paid leave usually provide this benefit through distinct social insurance schemes (that is, unemployment insurance, disability insurance or social insurance). But when care leave is embedded in an employment insurance program — as it is in Canada, Japan and the Netherlands — access may be restricted due to program parameters such as a requirement to work a certain number of hours or to fulfill certain eligibility criteria (relationship and living-arrangement requirements vary among programs). However, many ineligible people have family care needs, and programs in California, Sweden and Norway, while still targeting employees, provide benefits to a wider group of workers. These schemes allow part-time and self-employed workers, as well as workers with less-regular labour force participation patterns, access to the benefit.

In Canada, access to the CCB is limited to caregivers whose labour force participation is regular and full-time according to stipulations concerning accumulated numbers of hours worked in the past 12 months (600 insured hours in the last 52 weeks or since the start of the last claim). Self-employed caregivers who are not registered for EI are not eligible, and part-time seasonal workers or those with interrupted labour force participation may also be ineligible.

Lack of promotion and low awareness of the program. Before people can find out if they are eligible for the program, they need to know it exists. Although long-term care and family caregiving are high-profile issues for governments, it appears that knowledge of this program is not widespread. Placing brochures in social insurance offices is not enough to ensure awareness of the program among those who need it most.

Physicians as gatekeepers. Physicians could play a significant role in promoting paid leave programs to family caregivers, but health care reforms and the restructuring of acute care may have left them little time to do more than make a diagnosis before the patient is transferred to the long-term care system. This has been observed in Sweden (Keefe and Fancey 2005). To increase awareness of such programs, promotional efforts need to target social workers at the institutional and community levels, as well as employers and employees.

Labour market trends. Labour market conditions and attitudes toward work leave may also influence take-up rates. In times of labour surplus, employees may be more hesitant to request leaves, even when they are entitled to them, because they think this could suggest that they are not fully committed to their jobs. In times of labour shortage, employers may be less supportive of employees taking leaves and employees could be reluctant to ask for them because of the perception of lack of commitment and the longer-term implications for career promotion and advancement. Attaching employee-replacement conditions to leave policies may be a further deterrent, particularly if labour is unavailable. Caregivers may forego leaves in an effort to preserve their positions and employment status. Rather than giving employees more bargaining power, labour shortages can produce a heightened sense of employment insecurity, contributing to the stress and strain experienced by elder caregivers.

Uniqueness of the dying process. The CCB paid leave is based on a restrictive definition of “terminal illness.” A physician must issue a medical certificate confirming that the care receiver is at risk of dying within 26 weeks (Keefe and Fancey 2005). Families and doctors may be reluctant to make rigid determinations of impending death, and the uniqueness of the dying process can make it difficult to calculate the best time to take a leave. For example, older persons whose bodies are slowly losing functions have much different end-of-life and palliative care needs than those dying of a specific disease (Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada 2006). Furthermore, evidence suggests that physicians are poor at determining the life expectancy of those with terminal illness and conditions (Christakis 1999; Lamont and Christakis 2003).

Changing family demographics. Take-up rates reflect societal values and expectations related to who should provide care to family members. There are reports of gender differences in the utilization rates, with women representing 70 to 80 percent of program users (Keefe and Fancey 2005). This is the case regardless of the program, and the reasons for it are embedded in societal expectations and employment economics. Care work is seen as women’s responsibility, and time-use data continue to suggest that even though women are employed outside the home, they remain primarily responsible for care work in the home (Jenson 2005).

In addition, take-up rates may be affected by the changing profile of families. Current trends in Canada include an increase in the number of lone-parent families, an increase in the number of older people living alone, and changes in employment and occupational structures (for example, the rise of the service industries has brought less-regular hours and lower rates of pay). These changes in work and family are generating income security risks. In particular, families with a single earner/income fare badly, and if the earner is female rather than male, the income is likely to be lower (Jenson 2005). Thus, many families with family care responsibilities may need two earners to stay out of the low-income bracket, and taking leave, whether with partial income replacement or not, is not an option for most.

In summary, the research suggests that Canada’s CCB is an advancement in public policy as it draws public attention to the needs of families and caregivers. However, the CCB appears to be lagging in terms of the amount of the financial compensation it offers and duration of time benefits are administered. Moreover, it is recognized that embedding care leave in the national Employment Insurance system presents specific challenges that prevent the program from attaining its full potential for families.

Caregivers are not official clients of the home care system and are generally not entitled to services in their own right — they receive services indirectly, through the care receiver (Guberman 1999). From a caregiver’s perspective, there are two types of services: formal home care services that support the care of the older person needing assistance, such as personal care or nursing care delivered by paid providers; and services directed toward the caregiver, such as respite, information and education.

The extent to which publically funded services that support the care of dependent older people are available varies across provinces and even within provinces. Nevertheless, most, if not all, provinces and territories have at least some services directed toward family and friend caregivers. Services such as in-home or facility-based respite and adult day programs provide a period of respite, or a break, for the primary caregiver. Despite the recognition of the valuable role played by family and friend caregivers expressed in many strategic documents, caregivers face many challenges in accessing services. This is compounded by their ambiguous status in relation to public policy and programs — for example, in the Nova Scotia Home Support Program (Keefe and Fancey 1997), and more recently where caregivers may be eligible for both respite services and the Caregiver Benefit Program (Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness 2011).

Traditionally, home care service programs have been structured to meet the most immediate needs of care recipients, while the needs and interests of their family caregivers are often ignored, overlooked or considered as secondary (Guberman and Maheu 2000; Twigg 1989; Zarit 2006). Researchers and practitioners acknowledge the importance of conducting caregiver assessments in order to determine the needs of the family caregiver (as distinct from those of the care recipient) as well as to gauge the effectiveness of various service interventions in reducing caregiver burden (Farcnik and Persyko 2002; Zarit 2006). Such caregiver assessment is not part of in-home care programs in Canada.

The United Kingdom, among other jurisdictions, has had a legislated right for caregivers to be assessed by a professional (separately from their care recipients) for over a decade. Assessments are conducted at the local social services level, and through these assessments, information about programs directed to caregivers is communicated.

Assessment of caregiver needs implies the opportunity to meet these needs with an array of services and programs. Increased respite services and educational support for caregivers has been the mantra of some caregiver advocacy groups and academics searching for ways to support caregivers. Others have suggested that this would be too little, too late and would not have a significant impact on caregiver health. Respite care is particularly challenging if the care receiver is not accepting of formal services and supports or if the caregiver is not comfortable with the quality of care provided to the care receiver.

Nevertheless, there are opportunities to improve respite care services and access to other supports, such as adult day programs. Supports could be offered to the caregiver directly and not tied to the care recipient, who might not agree to become a client of a publically funded program. Australia, for example, has the National Respite for Carers Program, which makes funds directly available to caregivers for respite services, respite centres, resource centres and a caregiver-counselling program; this program is in addition to financial support policies for carers such as Carer Allowance, or the care payment and home care services provided to care receivers (Australian Government 2011).

Education and referral is another area where increased supports could help caregivers. These supports do not necessarily need to be provided by governments directly; they can be delivered through partnerships with volunteer agencies and organizations supportive of caregiver needs. Another Australian initiative to support caregivers is Carers Australia, a national organization representing family caregivers. Its members are carers’ associations in each state and territory that deliver advice and counselling services. It advocates for caregivers’ rights and entitlements to government. For example, in a recent submission to government, it called for a comprehensive package of new initiatives to support caregivers, including creating legislation to make the carer bonus an annual, indexed payment; doubling the Carer Allowance benefit; and introducing a carers’ superannuation scheme for recipients of the carer payment (Carers Australia 2008).

Carer Allowance recognizes the work of caregiving and offers some financial support to caregivers who reside with care receivers or spend a minimum of 20 hours a week providing care (Keefe and Rajnovich 2007). Eligibility is not limited by income. Created by the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission in 2007, the carers’ superannuation scheme involves paying carers whose caregiving responsibilities have kept them out of the workforce for two years or more 9 percent of the federal minimum wage. Caregivers who can return to the workforce could also be eligible for a 9 percent government top-up of their employer contributions for a predetermined period (Aiesi 2009).

Having sufficient human resources to meet the growing demand for care services is of increasing concern to both health care planners and human resource policy-makers. Many jurisdictions in Canada are already facing or anticipating shortages of home care workers (Canadian Home Care Association [CHCA] 2008),9 and with the eventual decline in the number of adult children available to provide informal care and assistance, the risk of such shortages will become even more acute (Keefe, Martin-Matthews, and Légaré 2011). In this section, I discuss the challenges related to recruiting and retaining the human resources that will be needed to address the shortage of family caregivers.

There is wide consensus in the literature that recruitment and retention of adequate staff is a key problem facing home care in Canada (CHCA 2008; CoÌ‚teÌ and Fox 2007; Leipert et al. 2007). The CHCA states that “the number one challenge concerning home care that provinces face is health human resources — recruitment, ongoing education and retention of trained staff” (2008, xix). As it does with the informal caregivers discussed in the previous sections, gender plays a definitive role in human resources problems (CHCA 2008). The high proportion of female home care workers, combined with the traditional perception that home care is a predominantly female field, has constrained the supply of male workers (MacAdam 2007). This is compounded by a general shortage of health care workers in Canada, competition for resources within continuing care and an aging population (MacAdam 2007).

To date, health human resources planning in Canada has tended to focus on strategies to meet the demand for health professionals, such as doctors and nurses (see, for example Health Canada 2006), despite the significant number of home support workers in the health system and the important role they play. There is evidence, however, of increasing governmental attention and commitment to advancing home care (MacAdam 2007) through improved human resources planning. For instance, the Special Senate Committee on Aging recommends that health human resources planning in Canada include home care and related support, and that the provincial, territorial and federal governments work together in this endeavour (Carstairs and Keon 2009). The Canadian Healthcare Association (2009) also makes specific recommendations for recruitment and retention. These include wage parity, reduction of the casual workforce, career path development, improved benefits, standardized education outcomes and employer involvement in curriculum development.

Like Canada, other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries are considering strategies to address human resource challenges. In a recent OECD report, Fujisawa and Colombo (2009) emphasize three main responses: increase the long-term care workforce (for example, through training programs and recruitment efforts targeting specific populations); create policies that capitalize on existing workforce capacity (such as improved wages and benefits, supports for family and friend caregivers, and service coordination); and minimize the need for long-term care workers (for example, by creating technological opportunities, promoting healthy aging and assigning care work differently).

Most studies on home support services have focused on the organizational aspects of home care service delivery, with an emphasis on working conditions and the stress and strain involved in providing care. A number of recent studies underscore poor pay, lack of benefits, inconsistent work hours and limited opportunities for advancement as key issues for home support workers (Denton et al. 2006; Fleming and Taylor 2007; Martin-Matthews and SimsGould 2008; Sharman et al. 2008; Yamada 2002). The same factors have been found to impact job satisfaction, with resultant negative effects on both recruitment and retention of workers (Denton et al. 2006, 2007; Feldman 1993; Nugent 2007; Zeytinoglu and Denton 2006). Many of these challenges are common internationally (Fujisawa and Colombo 2009).

An international review of strategies to address workforce shortages concludes that policy-makers need to think about two approaches to recruitment and retention: “one to improve direct care workers’ job conditions and the other to explore and evaluate the creation of new pools of supply” (Hussein and Manthorpe 2005, 90). The authors suggest that high-quality workers can be drawn to care jobs and retained if the attractiveness and working conditions of those jobs are improved.

More specific to home support or personal/health care workers, the work done by my colleagues and myself on planning for the human resources needed (Keefe et al. 2011) suggest that efforts to improve the occupation may benefit from attention to job impacts in four key areas: compensation, education and training, quality assurance, and working conditions. Compensation includes wage issues such as low wages, inconsistent wages across provinces (and even within provinces) and lack of wage parity with counterparts in institutional settings. There is also the matter of compensation for travel, both in terms of mileage reimbursement and payment for time spent travelling between clients (Keefe et al. 2011).

Education and training captures such issues as access to training programs, program entry and graduation requirements, length and content of training programs, training consistency, and determination of who pays for skills upgrading (Keefe et al. 2011).

Quality assurance encompasses maintenance of high standards within home care and the professional regulation of home support workers. Given the diversity of the occupational groups and services involved in home care, clear accountability structures are key (Keefe et al. 2011). Canadian home support workers are not currently regulated by any professional or governmental body. Within home care programs, the emergence of care teams has contributed to a sense of uncertainty about the role and scope of unregulated care team workers. Provincial provider registries could address this uncertainty and offer greater legitimacy to the occupation. By January 2011, British Columbia and Nova Scotia had both announced plans to establish registries for community health workers (Keefe, Martin-Matthews, and Légaré 2011). Registries could also be used to monitor and report on working conditions.

As an area for targeted intervention, working conditions includes issues related to workloads; stress levels; harassment, discrimination and racism; safety; travel, particularly in remote or isolated areas; job insecurity; and feeling undervalued (Keefe et al. 2011). These are all factors that have been identified as a contributing to job dissatisfaction.

Pan-Canadian consultations were held in 2009-10 to engage home care sector stakeholders in discussing priority issues impacting home support workers and identifying strategies (known or envisioned) that could help improve recruitment and retention (Keefe, Martin-Matthews, and Légaré 2011). Discussions were focused on the four key issues mentioned earlier. As expected, the issues identified as priorities varied by province. For instance, lack of wage parity (within and across provinces and sectors) was raised as a priority in British Columbia and Quebec (where wage parity legislation has yet to be implemented), but it was less of a concern in Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan, both of which have instituted legislation governing wages for home support workers. As another example, guaranteed hours (which provides income stability) was raised as a priority in Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan and British Columbia but only touched on in Ontario and Quebec. Similarly, standardization of education and training was considered a priority in several provinces, with the exception of Nova Scotia, which already has a provincial curriculum. For the Nova Scotia participants, national education and training standards were seen as a possible goal.