The negative effects of colonial disruption on Aboriginal families and communities continue to shape the quality of life of young Aboriginal children. Although many Canadians believe that the colonial oppression of Aboriginal peoples is long over, the situation is the same – or arguably even worse – today as it was in the early 1990s, when the background research was conducted for the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Significant structural inequities persist, and Aboriginal communities still have to justify their demand for self-determination in matters of health, education, social development and child welfare. Many Aboriginal children live in poverty, and as a result they have unacceptably high rates of health and developmental challenges. Environmental risks and acute health problems appear to be at an especially critical level among First Nations children living on reserve and among Inuit children across the North. While health and development indicators show that Aboriginal children are more likely than non-Aboriginal children to need health services and early interventions, they are far less likely to receive them. These legacies need to be recognized in government policy decisions and program investments.

One exception to an otherwise sluggish effort to ensure Aboriginal children have the same quality of life as other children in Canada is the sustained federal investment, for over a decade, in Aboriginal Head Start programs for children aged three to five. Supporting AHS and similar familycentred, holistic, preventive and community-driven programs is one way that Canada can ensure the safety, health and nutrition of young Aboriginal children and improve their quality of life in ways that reflect culturebased values and goals.

To date, these programs have accommodated only a small fraction of Aboriginal children, but the need of these children, as a result of poverty and the multigenerational harm done by the residential schools and other colonial government interventions, is especially great. This study supports the recommendation of a 2008 study by Leitch that investment in the AHS programs on and off reserve should be significantly expanded. Concurrently, in order to optimize and sustain the effects of AHS on children’s quality of life, expanded investment is needed in Aboriginal community economic development, prevention services and family-strengthening programs in child welfare services to Aboriginal children, particularly on reserve; and in public school reforms.

There are serious gaps in our information about young Aboriginal children’s ecologies, health and development. We do know enough, however, to meet our obligations under international conventions through structural remedies, community-based program development, monitoring and research. Studies conducted in high-, middle-, and low-income countries have demonstrated that low socioeconomic status and associated social exclusions contribute more than any other factor to low quality of life and reduced opportunities for optimal development within populations of children. There is also strong evidence of the efficacy of high-quality child care and other early childhood programs in ensuring safe, stimulating environments for children. When their families, communities and countries are ready to provide children with the quality of life they need and deserve, they will be less likely to require child welfare intervention and more likely to thrive. Equitable opportunities for quality of life and optimal development will allow generations of Aboriginal children to benefit from and contribute to a postcolonial society that protects and nurtures its youngest members and their diverse cultural heritage.

We will raise a generation of First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and youth who do not have to recover from their childhoods. It starts now, with all our strength, courage, wisdom and commitment.1

In 1989, Canada played a prominent role in helping the international community draft the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Eighteen years after Canada ratified the UNCRC, a 2007 United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report argued that relative to other nations on the list of the world’s 21 richest countries, Canada has been slow to honour its commitment to uphold these rights and ensure the well-being of children (Canada ranked 12th on the list, and the United Kingdom and the United States ranked 20th and 21st, respectively). The report singled out the plight of Aboriginal children as especially desperate, noting that in some communities they lack access to adequate housing and education, and even clean water (UNICEF 2007).2 Although the Government of Canada promised to improve conditions in its 1997 Gathering Strength: Canada’s Aboriginal Action Plan (Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development 1997), there is still no legal framework and no independent national children’s commissioner to monitor implementation of children’s rights federally and to coordinate federal, provincial and territorial policies that affect children. These needed strategies were recommended in a 2007 Senate report (Canada, Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights 2007).

This paper begins with a review of the life circumstances and opportunities for health and development of First Nations, Métis and Inuit children between infancy and five years of age. Evidence points to Canada’s lacklustre performance with regard to ameliorating poverty, health-related inequities and high rates of placement in government care. In the second section, promising approaches to improving these children’s circumstances are discussed with reference to a decade of community-driven innovation through the federal-government-supported Aboriginal Head Start program. In the third section, I make a number of recommendations that emphasize collaboration between governments and Aboriginal organizations, supported by streamlined access to resources. Such collaboration should enable communities to implement culture-based approaches to improving quality of life for Aboriginal children. In addition, I recommend the creation of new information-gathering strategies to monitor conditions and measure program effectiveness in order to make a case for long-term investments in programs that produce a lasting opportunity for Aboriginal children to enjoy their quality of life and achieve their developmental potential.

Almost no empirical research has been published to date to guide those establishing priorities, creating policies or making investments in improving the quality of life and developmental outcomes of Aboriginal infants and preschoolers. Sources of population-level data about Aboriginal peoples are often conflicting and contested, and are always incomplete, as not all populations of Aboriginal children have been surveyed. There is an urgent need for a coordinated effort to fill the information gaps. A national program is required to monitor conditions and outcomes for Aboriginal children and to evaluate interventions, not only for their operational efficiency, but also for their impacts on Aboriginal children.3 Meanwhile, the following discussion draws largely upon indirect indicators as well as the historical factors bearing on the quality of life of Aboriginal children in their formative years.

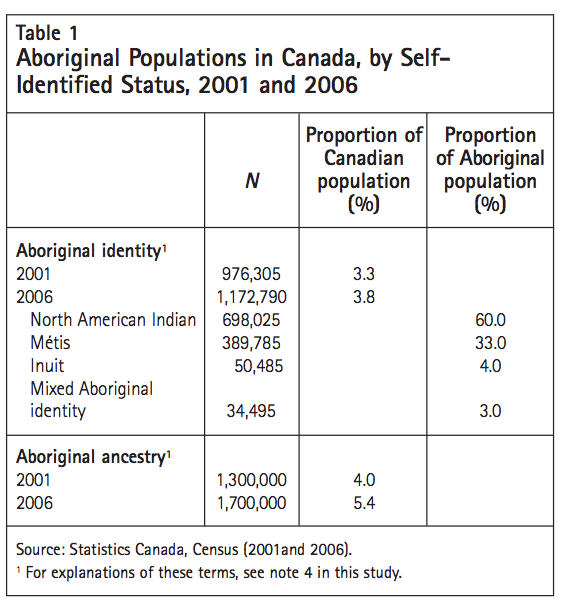

Between 1996 and 2006, Canada’s Aboriginal population grew by 45 percent — nearly six times more than the non-Aboriginal population (Statistics Canada 2006). In the 2006 Census, the number of Canadians who identified4 as Aboriginal surpassed 1 million.5 The Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes three Aboriginal peoples in Canada: North American Indian, Inuit and Métis. Census 2006 data for these groups are shown in table 1.6

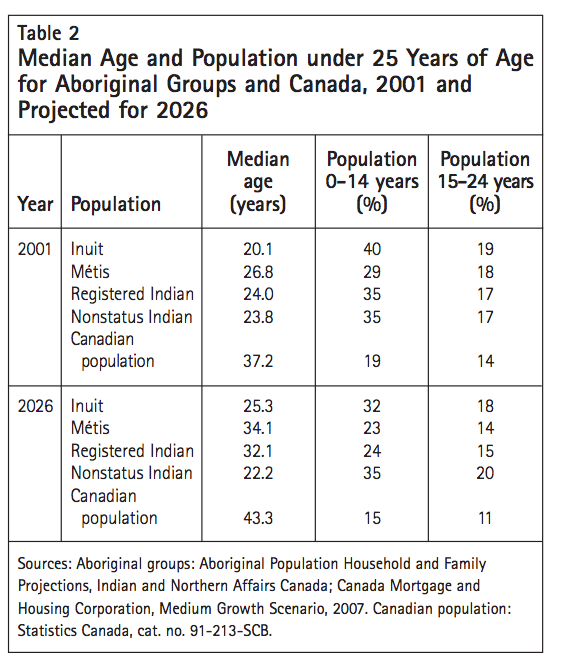

The population of First Nations people living on reserve is growing at a rate of 2.3 percent annually, which is three times the overall rate for Canadians. With a median age of 27 in 2006, the Aboriginal population is very young compared to the overall Canadian population, with a median age of 40. The Aboriginal populations of Nunavut and Saskatchewan are the youngest, with a median age of 22 years, followed by that of Manitoba, with a median age of 24 years. Table 2 provides data on the ages of Aboriginal population groups in 2001 and projections for 2026. In 2006, about 9 percent of the Aboriginal population was under five years old, and 10 percent was between five and nine years old (Statistics Canada 2006). The proportion of Aboriginal people under five years of age was approximately 70 percent greater than the proportion of non-Aboriginal people.

In 2006, 8 out of 10 Canadian Aboriginal people lived in Ontario or the western provinces. A slow but steady migration into urban centres has been noted over the last three censuses. In 2006, 53 percent of Aboriginal people lived in urban centres.7 Winnipeg, Edmonton and Vancouver have the largest Aboriginal populations. Another 27 percent of Canada’s Aboriginal people live on reserve, in self-governing First Nations and Métis settlements; and about 20 percent live in rural areas off reserve.

Among people identifying as North American Indian in the Census (which I refer to in this report by the more commonly accepted term “First Nations”), the most important distinction is between those living on reserve (40 percent) and those living off reserve (60 percent) (Statistics Canada 2006). The collective and individual well-being of on-reserve First Nations people is a matter of federal jurisdiction under the Indian Act, which affects almost every aspect of onreserve life. The federal government has a responsibility to fund a range of services, including children’s services, on a par with those available to all Canadians. While 98 percent of First Nations people on reserve are registered as status Indians under the Indian Act, many First Nations people who live off reserve have lost their entitlement to resources and services provided by the federal government under the Act and now access those provided by provincial governments to non-Aboriginal people. The number of First Nations people whom the Act deems eligible to receive status is continually dropping. Clatworthy has projected that within five generations, no one will be born eligible for status, rendering federal responsibility to provide resources and services to First Nations children and families obsolete and turning fiduciary responsibility for these supports entirely over to the provinces (2005).

”¨In Canada, the cultural nature of development, the pervasive influence of government policies (notably the Indian Act), and variations in access to supports and services result in very different life experiences and developmental outcomes for First Nations, Métis and Inuit children compared to non-Aboriginal children. Some of these differences may be seen in a positive light. For example, more young Aboriginal children (7 percent) than non-Aboriginal children (1 percent) share a home with their grandparents (Statistics Canada 2006), learn skills for living on the land, are exposed to an Indigenous language in their homes and have the opportunity to participate in the sacred ceremonies unique to their spiritual and cultural heritage (First Nations Centre 2005).

However, many aspects of young Aboriginal children’s experience of life are cause for alarm, including a 1.5 times greater probability of dying before their first birthday, higher rates of hospitalization for acute lung infections and accidental injury (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2004), higher rates of apprehension by child welfare services, and a greater chance of having to live in a series of foster homes outside their community (Trocmé, Fallon et al. 2005). All of these are largely the result of the lower quality of life afforded to a large proportion of young Aboriginal children, characterized by a lack of basic necessities — adequate housing, food security, clean water and access to services. Such deficiencies are indicators of poverty.8

No published reports of systematic assessments of developmental conditions or milestones in a population of young Aboriginal children were found for this review. No monitoring, screening or diagnostic tools have been empirically validated for use with Aboriginal children. Early childhood screening and assessment tools and school-readiness inventories currently used in Canada have been developed, normed and validated in research involving predominantly English-speaking children of European and Asian heritage living in middle-class urban settings.9

A perspective on selected aspects of First Nations children’s health comes from the First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey (RHS). Funded by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Health Canada, the RHS is the country’s only First Nations–governed national health survey. The national team, based at the Assembly of First Nations, collaborates with 10 independent RHS regional partners across Canada to plan, conduct and analyze the survey. While the inaugural survey, undertaken in 1997, encountered some challenges, data collection in 2002-03 was more successful: 22,602 parents were surveyed in 238 First Nations communities. From its inception, the survey has not systematically sampled Métis children, and in 2002-03, Inuit communities did not take part.

The children and youth component of the 2001 Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS) conducted by Statistics Canada collected information from the parents or guardians of 35,495 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children under 15 years of age (Statistics Canada 2001). Developed in collaboration with national Aboriginal organizations, the 2001 APS provided data on a variety of topics, including health, injuries, nutrition, child care, social activities and language. The sample included 13,666 children under the age of six. Of these, 9,466 lived off reserve. The remaining 4,200 children lived on the 116 reserves that participated in the APS. The data for these reserves are representative at the community level only and are not representative of the total onreserve population. The 2006 APS provided data for Aboriginal children and youth aged 6 to 14 and for adults aged 15 and over.

Aboriginal children were not systematically sampled in the two national longitudinal cohort studies of the development of Canadian children and youth (the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth and the Understanding the Early Years Study). Recognizing that neither of these two major studies has a large enough sample of young Aboriginal children to produce meaningful estimates, and that other surveys exclude some Aboriginal populations, Human Resources and Social Development Canada engaged Statistics Canada to conduct a survey — the Aboriginal Children’s Survey (ACS) — using the 2006 Census as its sampling frame. An original survey tool was created through extensive consultation with Aboriginal organizations and specialists in early childhood care and development, and through focus testing with Aboriginal parents. Agreements with national Aboriginal organizations representing Inuit, Métis and First Nations peoples living off reserve supported data collection; whether to conduct the survey on the reserves was still under discussion at the time of writing.

In 2006-07, the inaugural ACS surveyed over 13,000 caregivers of Inuit, Métis and First Nations children aged six months to five years living off reserve. The survey will yield quantitative data that will enable disaggregated and combined analyses of developmental trends; estimates of health problems and developmental difficulties; and information on the perceived accessibility and frequency of utilization of programs and services for Inuit, Métis and First Nations children living off reserve. In addition, the ACS will be the largest parent-report database on the developmental milestones, health, cultural learning and quality of life of Aboriginal preschool children in Canada. Meanwhile, in order to create a picture of young Aboriginal children’s living conditions, health and developmental outcomes, we must draw upon databases with varying inclusion criteria, as well as proxies, anecdotal and informal reports, and a scattering of program evaluations that are far from conclusive.

Many Aboriginal leaders and scholars have asserted that as a group, Aboriginal children have a diminished quality of life due to the negative impact of colonization on their parents, who were either forced as children to attend residential schools or are children of residential school survivors. As early as the 1600s, Indian children in New France were taken from their families and placed in institutions to be “civilized” and “Christianized.” This practice became more widespread in the 1820s, when the churches began to operate a number of these residential schools. Mandatory attendance became a matter of federal government policy in 1884. By 1960, more than half the First Nations and Métis children in Canada were enrolled in residential schools (Miller 1996). The last residential school — Gordon Residential School in Saskatchewan — closed in 1996. In 2002, it was estimated that one in six First Nations children under 12 years of age had at least one parent who had attended a residential school (Trocmé, Knoke et al. 2005).

Most children in residential schools were forced to stop speaking their language, repudiate their culture and spiritual beliefs, stop communicating with their siblings, and relinquish their Indian names and any belongings they had brought with them from home (Fournier and Crey 1997; Miller 1996). It has been well documented that many First Nations and Métis children were physically, emotionally and sexually abused by their residential school custodians (Haig-Brown 1988; Lawrence 2004). As a result, having never been nurtured by their own parents, many of today’s First Nations parents and grandparents did not learn parenting skills (Dion Stout and Kipling 2003; Mussell 2005). As Prime Minister Stephen Harper noted in the June 11, 2008 apology for the Indian Residential Schools system, this “sowed the seeds for generations to follow” (Office of the Prime Minister of Canada 2008). Many former residential school students lost confidence in their capacity to engage in the kind of nurturing social interaction with young children that promotes attachment and intimacy (WesleyEsquimaux and Smolewski 2004). Such interaction is the primary means of instilling self-esteem, a positive cultural identity, empathy, language development and curiosity about the world during infancy and early childhood.

Six out of ten First Nations and Métis respondents to the RHS identified the legacy of the residential schools as a significant contributor to poorer health status, along with insufficient access to healing programs and other treatment options (First Nations Centre 2005). Analyses reported by the RHS team in 2002-03 indicated that First Nations respondents’ health improved as the number of years since their family members attended residential schools increased (First Nations Centre 2005).

A significant proportion of Aboriginal children have also been placed by provincial child welfare agencies in non-Aboriginal foster and adoptive homes. This practice, though referred to as the “sixties scoop,” began in the 1950s and still continues (First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada 2005a). The forced relocation of entire villages, dispersal of clans and urbanization have further disconnected Aboriginal children and families from their communities, languages, livelihoods and cultures (Jantzen 2004; Lawrence 2004; Newhouse and Peters 2003; York 1990). These colonial legacies have an impact on a range of policy areas, including residential school healing programs, education and support for mothers and fathers during the transition to parenthood, infant development programs, highquality child care, family-strengthening initiatives, family literacy, community development, employment and social justice.

No doubt some Aboriginal parents and their children are thriving. The unique strengths of Aboriginal families have been described by Aboriginal scholars (Anderson and Lawrence 2003). Values and approaches that inform socialization in many such families include recognition of a child’s varying abilities as gifts, a holistic view of child development, promotion of skills for living on the land, respect for a child’s spiritual life and contribution to the cultural life of the community, transmission of a child’s ancestral language and an emphasis on building upon strengths rather than compensating for weaknesses. One child welfare study found that First Nations children are not overrepresented in reports of child abuse, suggesting that some protective factors are at work in Aboriginal families, however impoverished they are (Trocmé, Fallon et al. 2005).

Yet many Aboriginal parents of young children are struggling, as shown by the high rates of health problems, early school leaving, suicide attempts, substance abuse and criminal detention. The 2006 Census portrays a challenging family structure for many Aboriginal children. Thirty-five percent live in single-parent households (as opposed to seventeen percent of non-Aboriginal children), and this is associated with an increased likelihood of growing up in poverty. Among urban-dwelling Aboriginal children, more than 50 percent live in single-parent homes. The vast majority of Aboriginal single-parent homes are headed by women. More Aboriginal mothers”¨than non-Aboriginal ones are single, and more are adolescents. In fact, the number of First Nations children born to teenagers has remained high since 1986, at about 100 births per 1,000 women — a rate seven times higher than that for other Canadian teenagers and comparable to the rate in the leastdeveloped countries such as Nepal, Ethiopia and Somalia (Guimond and Robitaille 2008). Whereas the United Nations Population Fund and countries with high teen fertility rates, such as the United States, implement strategies to reduce teen fertility and address the needs of teen parents, Canada has few programs that specifically meet the needs of First Nations teen parents.

The absence of Aboriginal fathers from their children’s lives has been widely interpreted as an indication of their indifferent attitude (Claes and Clifton 1998; Mussell 2005). Yet the marginal living conditions and mental and physical health problems faced by these men (Health Canada 2003), combined with an overwhelmingly negative social stigma, create formidable obstacles. Virtually all of the 80 men interviewed for an inaugural study of Canadian First Nations and Métis fathers of young children reported past or current challenges related to mental health or addiction, and most were struggling to generate a living wage and to secure adequate housing (Ball, forthcoming). Research on non-Aboriginal fathers shows a significant correlation between paternal involvement and developmental outcomes for children, mothers and fathers (Allen and Daly 2007). A father’s absence is associated with more negative developmental and health outcomes for his children and for the father himself (Ball and Moselle 2007). Grand Chief Edward John of the BC First Nations Summit has argued that “Aboriginal fathers may well be the greatest untapped resource in the lives of Aboriginal children and youth” (2003). At the same time, while the majority of Aboriginal children residing in urban settings are living in lone-mother-headed households, 6 percent of Aboriginal children identified in the 2006 Census are being raised by lone fathers. First Nations children living on reserve and Inuit children are twice as likely as other Canadian children to reside in lone-fatherheaded households (Health Canada 2003; Statistics Canada 2006). There is no program in Canada specifically designed to help Aboriginal fathers become effective supports for their children (Ball and George 2007), and there are few program supports specifically for Aboriginal parents, especially on reserve.

A plethora of studies have shown that up to”¨50 percent of the variance in early childhood outcomes is associated with socio-economic status (Canada Council on Learning 2007; Case, Lubotsky and Paxson 2002; Dearing 2008; Raver, Gershoff and Aber 2007; Weitzman 2003). Many of the health and developmental problems of Aboriginal children are understood to reflect the cumulative effects of pervasive poverty and social exclusion (Canadian Institute of Child Health 2000). A recent report of the National Council of Welfare links the impoverishment of Aboriginal families to their “tremendous programming needs, reliance on food banks, and cyclical poverty” (2007, 26).

The 2006 Census indicates the pervasiveness and depth of poverty among Aboriginal children. Depending upon the criteria for defining poverty and whether the child is of Aboriginal identity or Aboriginal ancestry, 41 to 52.1 percent, or almost half of Aboriginal children, live below the poverty line. The average annual household income of families of First Nations children is almost three times lower than that of non-Aboriginal Canadian families; one in four First Nations children live in poverty, compared to one in six Canadian children as a whole.

Related to employment and household income, the average level of educational attainment among Aboriginal parents is lower than it is among nonAboriginal parents. But this gap seems to be narrowing: the proportion of Aboriginal people who have a high-school diploma or post-secondary education increased from 38 percent in 1981 to 57 percent in 2001. Yet by 2001, the proportion of Aboriginal people who had not completed high-school was 2.5 times higher than the proportion of non-Aboriginal Canadians. The gap in high-school attainment is the highest for Inuit people, at 3.6 times higher. Significantly, one of the primary reasons Inuit students give for leaving high school is to care for a child (Government of Nunavut and Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated 2004). In 2003, the British

Columbia Ministry of Education found that the proportion of students in grade 4 who were “not meeting expectations” was 16 percent higher among Aboriginal students than among non-Aboriginal students. By grade 7, the difference had risen to 21 percent. Between 40 and 50 percent of Aboriginal students failed to meet the requirements set by grade 4, 7 and 10 literacy tests (Bell et al. 2004).

According to data from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, at least 33 percent of First Nations and Inuit people (compared to 18 percent of nonAboriginal people) live in inadequate, unsuitable or unaffordable housing (Engeland and Lewis 2004). Twenty-eight percent of on-reserve First Nations children live in overcrowded or substandard housing; 24 percent of off-reserve Aboriginal children live in substandard housing. Aboriginal homes are about four times more likely than Canadian homes overall to require major repairs, and mould contaminates almost half of First Nations homes. Aboriginal homes are often poorly constructed and ventilated; their plumbing systems are often inadequate for the number of residents; and their clean water supply is often unreliable. Six percent of these homes are without sewage services, and four percent lack running water and flush toilets (Assembly of First Nations 2006a).

A study of the indoor air quality for Inuit children under five years of age found that their homes had an average of 6.1 occupants (the homes of their southern Canada counterparts averaged 3.3 to 4.4 occupants). Most of the homes studied were smaller than 93 square metres. In 80 percent, ventilation rates were below the recommended Canadian standard, while carbon dioxide levels far exceeded recommended concentrations — an indicator of crowding and reduced ventilation. Smokers were present in 93 percent of the homes (Kovesi et al. 2007).

One in three First Nations people consider their main drinking water unsafe to drink, and 12 percent of First Nations communities have to boil their drinking water. Contaminants in the water and food supply are a growing problem for those concerned with the health and wellness of young Aboriginal children. For example, one study found that more than 50 percent of Inuit in a Baffin Island community had dietary exposure levels of mercury, toxaphene and chlordane exceeding the provisional tolerable daily intake levels set by Health Canada and the World Health Organization (Chan et al. 1997).

Studies on selected variables indicate that Aboriginal children are more likely to suffer poor health than are non-Aboriginal children, and that this is likely to affect their development and quality of life. A research review by the Canadian Institute for Health Information found evidence of poorer health outcomes among young Aboriginal children compared to non-Aboriginal ones on almost every indicator. For example, they are more likely to suffer accidental injury, to have a disability, to be born prematurely or to be diagnosed with fetal alcohol syndrome disorder. The tuberculosis rate for First Nations people in the 1990s was at least seven times higher than it was for all Canadians (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2004).

A recent study showed significant correlations between overcrowded, poor-quality housing and the health of Inuit children. It also found that Inuit infants in the Baffin region of Nunavut have the highest reported rate of hospital admissions in the world because of severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) lung infections, with annualized rates of up to 306 per 1,000 infants. Twelve percent of Inuit infants admitted to hospital require intensive care, which often means being airlifted to hospitals in southern Canada. Inuit infants also have disproportionately high rates of permanent chronic lung disease following lower respiratory tract infections (Kovesi 2007).

In 1999, the RHS obtained reports of First Nations and Inuit parents on the health and development of their children under 18 years of age. This survey found that the rates of severe disability — including that related to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, hearing loss, and attention and learning disorders — among on-reserve First Nations children and Inuit children were more than twice the rate for non-Aboriginal children. The highest rates were for on-reserve First Nations children (First Nations and Inuit Regional Health Survey National Steering Committee1999).

Studies have consistently reported evidence of insufficient nutrition among Aboriginal children: their diets tend to be high in sucrose, low in vegetables and marked by frequent consumption of fast food and junk food (Kuhnlein, Soueida and Receveur 1995; Moffatt 1995). These dietary trends are thought to play a major role in the development of type 2 diabetes (Gittelsohn et al. 1998) and its major risk factor, obesity (Hanley et al. 2000), both of which disproportionately afflict Aboriginal children in Canada.

Governments have tended to address these issues in an ad hoc manner, but have nevertheless found funds in “emergencies,” when health problems are declared to have reached “epidemic” proportions in specific communities (for example, during a 2005 health crisis in Kashechewan, northern Ontario, triggered by contaminated drinking water, and a 2007 series of suicides in Hazelton, BC, attributed to a devastated local economy and multigenerational trauma caused by residential schools). However, the level of sustained investment has been inadequate to produce long-term improvements in environmental determinants of Aboriginal children’s well-being.

One of the consequences of the colonial disruption of Aboriginal family and community life is that Aboriginal children are greatly overrepresented among children in government care. There are approximately 27,000 Aboriginal children younger than 17 in government care — three times the number enrolled in residential schools at the height of their operations, and more than at any time in Canada’s history. In some provinces, Aboriginal children outnumber non-Aboriginal children in care by a ratio of 8 to 1. There are important differences among Aboriginal groups with regard to child welfare interventions. For example, 10.2 percent of status First Nations children were in the care of the state, compared to 3.3 percent of Métis children (First Nations Child and Family Caring Society 2005a). The rate for non-Aboriginal children was 0.7 percent (Blackstock, Bruyere and Moreau 2005). These staggering figures prompted the Assembly of First Nations to file a human rights complaint against the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs in February 2007 to protest inadequate funding for child welfare agencies on reserves that could prevent high numbers of First Nations children being taken into care.

Child welfare interventions involving Aboriginal children include investigations of maltreatment; there are also investigations into the practice of removing children from their family homes and placing them in foster care, usually in non-Aboriginal homes outside of their communities. The Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect, conducted in 1998 and again in 2003, has revealed that although only 5 percent of children in Canada are Aboriginal, they account for 17 percent of cases reported to child welfare agencies and 25 percent of children in government care (Trocmé, Fallon et al. 2005). Another study estimated that Aboriginal children represented between 30 and 40 percent of Canadian children in out-of-home care in the late 1990s (Farris-Manning and Zandstra 2003). Yet another study showed a 71.5 percent increase in out-of-home placements of onreserve First Nations children between 1995 and 2001 (McKenzie 2002).

The Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect has shown that the primary reason Aboriginal children enter the child protection system is neglect — including physical neglect and lack of supervision when there is a risk of physical harm. As Blackstock and other Indigenous scholars have argued, these and other factors are indicators of the grave socio-economic conditions of Aboriginal people. The Assembly of First Nations has commented that while there are apparently insufficient funds to support some First Nations families in their effort to keep their children safely at home, the funds to remove First Nations children from their homes are seemingly unlimited (2006b). The current crisis in child welfare practice involving Aboriginal children is most dire for First Nations children living on reserve. Ensuring the well-being of these children is a federal responsibility, and therefore Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) must fund child welfare services. Shortfalls in funding for prevention and early intervention programs within on-reserve child welfare services have been acknowledged by INAC (Blackstock, Bruyere and Moreau 2005). In addition, there is no program within INAC that actively supports and monitors the range of prevention and early intervention services (McDonald and Ladd 2000; Blackstock, Bruyere and Moreau 2005) — services that are available to other Canadian children through the provincial system.

The 2005 Wen:de Report10 draws on evidence from the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect to demonstrate the need to improve the funding formula for First Nations-delegated child and family service agencies to support primary, secondary and tertiary intervention services in on-reserve First Nations communities (First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada 2005b). Such improvement would enable a policy of least-disruptive measures related to children at risk of maltreatment or neglect. Examples of least-disruptive measures include: in situ rather than out-of-community foster placement or adoption; support for improved parenting; more supervision of children through daycare placement; local access to services for children and parents; and supplementary food resources. According to Blackstock, Bruyere and Moreau, giving First Nations child welfare agencies the basic tools to help children and families would cost less than 1 percent of the 2005 federal budget surplus of $13 billion (2005). To date, few Wen:de Report recommendations have been acted upon.

As part of the growing movement toward Aboriginal self-government, many Aboriginal communities aspire to form their own child welfare agencies with a full range of family support, prevention and early intervention services, as well as foster and adoption placement. There are many challenges to this agenda for communities on reserve, partly as a result of federal funding shortfalls as well as a lack of trained Aboriginal child protection workers in Canada and difficulty recruiting trained practitioners to work in settings where there are few support services or alternatives for children. Challenges are also being encountered by urban Aboriginal, Inuit and Métis child welfare agencies off reserve, though the number of these agencies is steadily increasing (Bala et al. 2004).

Jurisdictional disputes among federal and provincial governments contribute to the impoverishment of the quality of life of First Nations children living on reserve. Disputes within service agencies about which level of government will cover the cost of a service can result in these children being denied timely provision of urgently needed services that are more readily available to children elsewhere in Canada. Responding to this denial of basic human rights, the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society proposed the adoption of Jordan’s Principle, named in memory of a First Nations boy from a Manitoba reserve. Born with complex medical needs, Jordan spent two years in a Winnipeg hospital, after doctors had said he was well enough to go home, due to a jurisdictional funding dispute between the province, INAC and Health Canada. Jordan died before the dispute was resolved, never having lived in his family home.

Jordan’s Principle is that when a jurisdictional dispute arises between or within governments regarding services for a status Indian child — services that are available to other Canadian children — the government of first contact must pay for the service without delay or disruption and resolve the jurisdictional dispute later (Lavallee 2005). Research has found that jurisdictional disputes over payment for essential medical and other health services for First Nations children are common, with nearly 400 cases occurring in a sample of 12 First Nations child and family service agencies over a one-year period (First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada 2005a). A resolution endorsing Jordan’s Principle was passed unanimously in the House of Commons on December 12, 2007, but by the end of that year, only Nova Scotia had put into place an agreement to implement it.

Many Canadian service providers, educators and commentators tend to see Aboriginal children as at risk for negative development outcomes such as depression, substance abuse, suicide, involvement in the sex trade and homelessness. They seem to think that the challenges Aboriginal children face are selfgenerated, and therefore they support the idea that Aboriginal children must be protected through more focused efforts to make them ready for public school — for example, by promoting early reading, early numeracy and proficiency in the dominant language of instruction; by providing extra learning supports in special classrooms; and, in some cases, by placing them in the care of the government.

What those who hold this view fail to see are the structural risks that are also at play such as poverty, environmental degradation, and a lack of community-based programs (operated by Aboriginal people) to promote health and family development. Many of the risks faced by Aboriginal children arise from such structural factors, as well as from ongoing racism and political oppression. What this means is that high rates of disease in early childhood, placement in state care and early school leaving cannot be reduced simply by investing more in medical care, parenting programs and targeted school-based interventions.

According to quality of life indices based on labour force activity, income, housing and education, the bottom 100 of nearly 4,700 Canadian communities includes 92 First Nations communities; the top 100 includes only one (Pesco and Crago 2008). Analyses of quality of life indicators using the United Nations Human Development Index have concluded that, if taken as a group, the Canadian Aboriginal population would rank 48th out of 171 nations, and First Nations communities would rank 73rd compared with Canada as a whole, which has been among the highest-ranked nations using this index (White, Beavon and Spence 2007). The UN report concluded that Canada has disregarded the socio-economic objectives to which it is committed under international law (United Nations 2004).

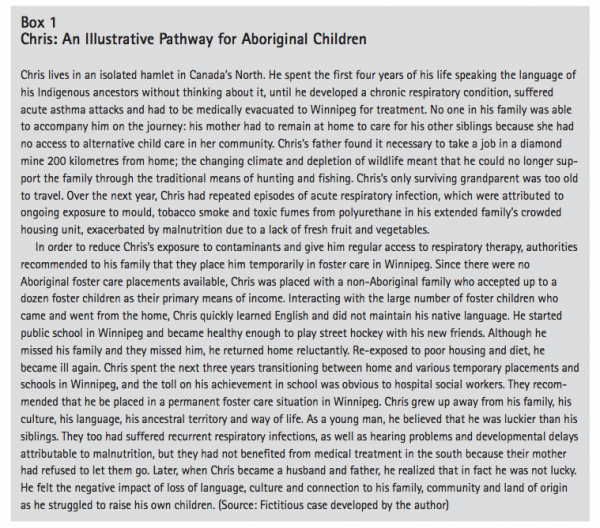

The case of Chris (see the text box) illustrates an Aboriginal child’s typical pattern of loss of culture and language of origin and assimilation into the dominant urban Canadian culture. Early school leaving and a sense of displacement and longing are all too common among Aboriginal children, who lack access to basic rights including adequate housing, food security, and health services for acute and chronic conditions close to home. Government interventions over generations have resulted in large numbers of Aboriginal children losing their connections to family, community and culture. The gravity of the situation for young Aboriginal children like Chris calls for fundamental changes in policies and programs, as well as in the goals, attitudes and understandings that drive them.

In light of historical barriers such as those discussed earlier, Aboriginal community representatives, leaders, practitioners and investigators have stressed the need for an adequately resourced, sustained and culturebased national strategy to improve supports for young Aboriginal children’s development. They have called for resources to enable these children to acquire skills valued by their parents such as speaking their Indigenous language, and services to address their health and developmental difficulties such as ear infections and hearing loss, before they start school. These supports must be delivered within the context of families and cultural communities through community-driven programs operated by trained Aboriginal practitioners (Assembly of First Nations 1988; Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996).

In 1990, the Native Council of Canada (NCC) undertook the first national effort to define Native child care and the meaning of cultural appropriateness with respect to the delivery of child care services. Its report, Native Child Care: The Circle of Care, conceptualized a direct link between culturally relevant child care services that are controlled by First Nations and the preservation of First Nations culture. As Indigenous scholar Margo Greenwood has summarized: “Aboriginal early childhood development programming and policy must be anchored in Indigenous ways of knowing and being. In order to close the circle around Aboriginal children’s care and development in Canada, all levels of government must in good faith begin to act on the recommendations which Indigenous peoples have been articulating for early childhood for over 40 years” (2006). From the perspective of the NCC report, governments have failed to mobilize a sufficiently thoughtful and coordinated response to these demands, in large part because they have failed to acknowledge the multigenerational impacts on today’s Aboriginal children of years of colonial interventions.

Long-standing inequities persist between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in access to health services; access is particularly poor for First Nations children living on reserve and for children in remote, isolated and northern communities (Adelson 2005; deLeeuw, Fiske and Greenwood 2002; Health Canada 2005). In 2004, the Assembly of First Nations put forward a health action plan calling for First Nations–controlled, sustainable health promotion and health care systems that would embody holistic and culturally appropriate approaches. There have been some improvements in recent years. New health-related initiatives include the creation of institutions such as the National Aboriginal Health Organization and the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, driven by Aboriginal people; the Regional Longitudinal Health Survey, controlled by Aboriginal people; the Aboriginal Health Transitions Program within Health Canada, which supports pilot projects demonstrating culture-based, integrated and more accessible health services for Aboriginal peoples; and some transfer of authority and control over health and social services to Aboriginal peoples. However, new federal health program funding is often provided only to selected communities and, judging by available health indicators, it does not appear to be adequate.

A boriginal leaders and agencies across Canada have long argued that the overall lack of services for young Aboriginal children as well as the cultural inappropriateness of the tools for monitoring, screening, assessing and providing extra supports for them — frequently results in serious negative consequences for these children (British Columbia Aboriginal Network on Disability Society 1996; Canadian Centre for Justice 2001; First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada 2005a; Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996).

Overall, indicators of the developmental challenges and negative outcomes of many Aboriginal children, combined with their high incidence of health problems, are so alarming that in 2004, the Council of Ministers of Education stated: “There is recognition in all educational jurisdictions that the achievement rates of Aboriginal children, including the completion of secondary school, must be improved. Studies have shown that some of the factors contributing to this low level of academic achievement are that Aboriginals in Canada have the lowest income and thus the highest rates of poverty, the highest rate of drop-outs from formal education, and the lowest health indicators of any group” (Council of Ministers of Education 2004, 22).

Extensive research has shown that targeted investment in a range of community-based programs can make a difference in shortand long-term health, development, educational achievement and economic success, as well as parenting of the next generation (Doherty 2007; Cleveland and Krashinsky 2003; Heckman 2006: McCain, Mustard and Shanker 2007). “Early childhood care and development” (ECCD) refers to a broad range of home-based, centred-based and community-wide programs as well as specialist services aimed at promoting optimal development from birth through five years of age. The largest portion of investment in early childhood programs in most high-income countries is used to support a network of child care and early learning programs offered in licensed home daycares and child care and development centres. Recent research suggests that such programs can counteract some of the effets of vulnerability linked to multiple risk factors (Jappel forthcoming).

Unlike most other high-income countries, Canada lacks a national strategy to ensure access to highquality programs that will stimulate and ensure optimal development during the early years for all children or for children in an identified risk category. For all children in Canada, early childhood initiatives are part of a catch-as-catch-can collection of programs and services. In 2003, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Directorate for Education produced a grim report on the piecemeal, unevenly distributed, generally unregulated or low-quality programs and services available to Canadian families caring for infants and young children. It noted that the vast majority of Canadian children do not have access to regulated child care or early learning programs and charged that the situation is much bleaker for young Aboriginal children. The team reported that with respect to access to highquality, culture-based early learning and care programs, young Aboriginal children are very disadvantaged and socially excluded compared to the population as a whole (Bennett 2003). An estimated 90 percent of Aboriginal children do not have access to regulated infant development or early childhood programs with any Aboriginal component (Battiste 2005; Canada Council on Learning 2007; Social Development Canada, PHAC and INAC 2005). Many young Aboriginal children are never seen by developmental specialists (infant development consultants, child care practitioners, pediatricians or speech-language pathologists).

For Aboriginal families, access to early childhood programs and developmental services is complicated from both a funding and a regulatory perspective because of the multiple jurisdictions involved and the significant variation in provisions for young children and families between provinces.11 For example, most First Nations children residing on reserve have no access to ancillary health services such as those provided by speech-language, occupational or physical therapists. When a child does have access, the services are not paid for or reimbursed by the federal government. Provinces vary in the way they provide access and coverage for First Nations children, whose well-being is the fiduciary responsibility of the federal government.

A survey conducted in 2001-02 found that 66 percent of the federally funded child care centres for First Nations and Inuit children had long waiting lists (Human Resources and Social Development Canada, Health Canada and Indian and Northern Affairs Canada 2002). During that period, approximately one-third of Aboriginal children living on reserve attended partial-day prekindergarten or kindergarten programs in an on-reserve elementary school. Children living on reserves that do not offer these programs are eligible to enrol in kindergarten for five year olds in an off-reserve school; fees charged to these pupils are paid by the federal government. No data are available on the number of children living on reserve who use this provision. Most Aboriginal children living off reserve depend on the services provided by provincial or territorial governments, some of which target them — for example, Aboriginal Head Start in all provinces and territories, and BC’s Aboriginal Infant Development Program.

In addition to a call for increased investment in programs targeting and tailored to Aboriginal children, there is a call for more non-Aboriginal early childhood programs and services to ensure the cultural literacy of practitioners, cultural safety of parents and cultural learning of Aboriginal children. The 2003 OECD report found that although sensitivity to Aboriginal families and incorporation of Aboriginal cultures were seen as goals by many policy-makers and program directors, there was little evidence that these aspirations were being pursued in mainstream child care and early learning settings (Bennett 2003).

These criticisms notwithstanding, there have been some investments over the past decade at every level of government that have engendered an Aboriginal early childhood care and development movement that is strengthening Aboriginal human resource capacity and giving rise to program innovations. In 1995, five years after the NCC’s Circle of Care called for investment in culture-based developmental programs and services for young Aboriginal children, the federal government committed new funding to establish the First Nations/Inuit Child Care Initiative. The overall goal was to ensure high-quality child care for First Nations and Inuit children that was on a par with that available to other Canadian children and would meet the unique needs of their communities. A fundamental principle was that First Nations and Inuit should direct, design and deliver services in their communities, reflecting federal government recognition of their inherent right to make decisions affecting their children. Steps taken to increase Aboriginal capacity in the early childhood care and development sector include the training of Aboriginal infant development and child care staff (mostly unaccredited and on a shortterm basis), as well as the creation of child care spaces, parent education resources and programs, and organizations that enable networking and resource exchange.

A review of program literature, Web sites, newsletters and agency reports yields a plethora of communitybased and community-involving Aboriginal ECCD programs that have been initiated in the past decade across the country. Many of these programs are directed at families needing extra support to provide adequate supervision, nutrition and nurturing to their children in order to stop the cycle of child removal by welfare agencies. Some programs target children with health or developmental challenges. Many communities have developed their own approaches for home-visiting programs, nurseries and preschools, creating culture-based elements and drawing upon curricula common to many early childhood programs — such as music and movement, storytelling, preliteracy and prenumeracy games, as well as parenting skills. One objective of these programs is to reinforce a positive cultural identity in Aboriginal youngsters and their families by, for example, drawing upon traditional motifs in arts and crafts, drama, dance and stories, and by providing opportunities to engage with positive Aboriginal role models in child care and teaching.

The resulting growth in Aboriginal ECCD was indicated in the parents’ reports included in the 2001 Aboriginal Peoples’ Survey: 16 percent of Aboriginal children entering first grade had participated in programs geared to Aboriginal people during their preschool years, compared to only 4 percent of children who had turned 14 in the same year (Statistics Canada 2001). The survey indicated that the proportion of Aboriginal children living off reserve who were attending early childhood programs specifically designed for them had increased fourfold over an eight-year period, reflecting in large measure the federal investment in Aboriginal Head Start (AHS).

With the exception of the AHS programs (discussed in the next section), a large number of promising community-based programs driven by Aboriginal people rely on surplus funds from other programs, special project funds requiring annual reapplication or one-time-only seed grants, which undermines their capacity to succeed. For instance, there is little incentive for community members to seek the training required to staff programs that are not likely to last. Program staff may no sooner develop trusting relationships with families and partnerships with other community organizations than the program abruptly terminates. Tenuous and attenuated funding does not create sustainable community capacity or confidence among community members that their children’s needs will be reliably met.

The Aboriginal Head Start (AHS) programs, which commenced in the mid-1990s, are a bright light in the otherwise gloomy landscape of federal government initiatives for young Aboriginal children. AHS was inspired by the Head Start movement pioneered in the United States in the 1960s, which heralded the dawn of the modern era of early childhood intervention (Smith and McKenna 1994; Zigler and Valentine 1979). Head Start in the United States — and an adaptation in the United Kingdom called Sure Start — are government safety nets for children at risk of suboptimal developmental outcomes as a result of poverty or disability. The goal is to prepare children to make a successful transition to formal schooling and to achieve on a par with their less-disadvantaged peers.

In 1995, the Government of Canada committed new funding to establish AHS. Its aim was to address disparities in educational attainment between First Nations, Métis and Inuit children and non-Aboriginal children living in urban centres and large northern communities.12 Aboriginal Head Start Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) is operated by the Public Health Agency of Canada; an expansion of AHS for children living on reserve in First Nations communities was undertaken in 1998. This expansion was a result of commitments made in two reports following on the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples — Securing Our Future Together (1994) and Gathering Strength: Canada’s Aboriginal Action Plan (1998) — and in the September 1997 Throne Speech. Aboriginal Head Start On Reserve (AHSOR, previously known as First Nations Head Start) is operated by Health Canada and collaborates with other Health Canada programs, such as Brighter Futures, in an effort to fill service gaps and coordinate program objectives.

In 2001, AHSOR served approximately 6,500 Aboriginal children living on reserve across Canada, while AHSUNC served approximately 3,500 children, or about 7 percent of age-eligible Aboriginal children living off reserve across Canada. At the time of writing, there were 130 AHSUNC programs, reaching approximately 4,500 Aboriginal children across Canada. An estimated 10 percent of Aboriginal preschool children between three and five years of age currently attend AHS programs. Acceptance criteria vary from one community to another. Generally, AHS programs accept Aboriginal children aged three to five on a first-come, first-served basis. Some programs require parents to volunteer hours or make a monetary contribution; some reserve spaces for children referred by child welfare or other social service agencies in the community. Most children with special needs are eligible to participate in AHS programs if qualified staff and the necessary facilities are available.

AHS programs are usually managed by Aboriginal community groups or First Nations governments in consultation with parent advisory committees. National and regional committees of Aboriginal representatives have been established to oversee their implementation. Programs generally operate on a part-time basis three or four days a week. Both onreserve and off-reserve AHS programs are staffed mainly by Aboriginal people, who serve as early childhood educators, managers, administrative support and, in some programs, parent outreach workers, bus drivers and cooks (Health Canada 2002).

Canadian AHS differs substantially from US Head Start. While they share the goal of preparing children for a successful transition from home to school, the emphasis of Canadian AHS is on the culture-based and community-specific elaboration of six program components: culture and language; education and school readiness; health promotion; nutrition; social support; and parent/family involvement. In most communities, efforts are made to hire Aboriginal staff, though they are in short supply. Staff trained in early childhood education work with Elders, Indigenous language specialists, traditional teachers and parents to enhance the development, cultural pride and school readiness of young children. Most programs, both on and off reserve, operate primarily in English, although in some, children are exposed to one or more Indigenous languages. AHS programs are locally controlled, allowing for innovation in finding the best curricula and staff for each community and each child. This presents challenges when it comes to evaluation.

The AHSUNC program has been the focus of some evaluation effort, including a descriptive evaluation released in 2002 and a three-year national impact evaluation completed in 2006. The 2002 evaluation focused mostly on the demographic characteristics of children served by AHS, parental involvement, and program facilities and components. The overall impression of this evaluation was that AHS was extremely well received — parents saw it as beneficial in many respects. However, there was no systematic assessment of impacts on the specific areas of child development, child health or quality of life before and after participation in the program (Public Health Agency of Canada 2002).

Approaches to measuring the impact of programs on Aboriginal children’s development have been fraught with difficulty, partly due to the lack of appropriate instruments to measure this development in ways that are readily amenable to standardized scoring and composite analysis. In the National Impact Evaluation of AHSUNC, participating evaluation sites had widely varying interpretations of the dimensions to be evaluated and scoring criteria. The evaluation did not include procedures with established validity or reliability for measuring baseline, exit or longitudinal levels of children’s health, development, cultural knowledge or quality of life; or parents’ confidence, competence or social support. It did not ask what sites were doing to promote various measurable developmental outcomes. Also, its research design did not include comparison or control groups, which are always ethically and practically challenging to organize in small communities. Although the evaluation had many methodological shortcomings, efforts were made to obtain data on children’s language and prereading skills, fine and gross motor skills, social skills and health. In addition, parents were surveyed as to their level of satisfaction with the programs and their children’s abilities.

A detailed report of the findings of the AHSUNC National Impact Evaluation had not been released by the time of writing, but a brief overview had been delivered. Children were assessed at the beginning and the end of one year of participation in the program by means of the Work-Sampling System, which records their ability to perform various tasks. Children with low baseline scores in the areas of language and literacy showed “moderate proficiency” in these areas after participating in the program, and there were also improvements in their physical development and health. Parents reported increases in their children’s practice of Aboriginal culture and traditions and Aboriginal language acquisition. No direct measurement of children’s behaviours was made (Public Health Agency of Canada 2007). Given the limitations of the study design and data analysis, we cannot draw conclusions about the effects of participation in AHS upon health or development or the effectiveness of AHS as an early intervention for vulnerable children or parents.

An evaluation of AHS sites in the Northwest Territories (NWT), undertaken from 1996 to 2006 by the Western Arctic Aboriginal Head Start Council, is somewhat more informative. Its findings have the potential to be generalized to AHS programs as a whole, insofar as the NWT programs embodied the six AHS program components that are federally mandated. Similar to AHS programs across Canada, the NWT programs employed activities that developed children’s knowledge of their cultural heritage and competence in areas valued in their cultural communities — from prereading to prehunting skills. An initial, descriptive evaluation in 1998 focused on infrastructure issues such as staff retention, facilities and equipment. From 2000 to 2001, and again in 2004, data were collected on various child outcomes identified as important by local program staff using measures of each child’s overall health and development, social skills and vocabulary that were seen by local advisors as having potential (though not proven) validity for Aboriginal children (such as the Brigance preschool and kindergarten screening scales). As well, the quality of the program environment was measured using a standardized early childhood environment rating scale, and culture and language program impacts were assessed using parent and community surveys. The sample of AHS enrollees participating in the research consisted of 84 Aboriginal children in 2001 and 139 in 2004.

One conclusion of the study was that children who participated in the NWT AHS programs had, as a group, widely varying skill levels when they began the program as four year olds (including a significant number with deficits in language development and social skills) and had widely varying skill levels after one winter in AHS. Differences between children remained. For example, the data showed improvements in scores based on measures of early learning and school readiness from fall to spring for both the 2001 and 2004 cohorts. Nevertheless, at the end of one winter of AHS, 31 percent (the 2001 cohort) to 51 percent (the 2004 cohort) of AHS children were delayed in terms of school-readiness skills, while 29 percent (the 2001 cohort) to 47 percent (the 2004 cohort) had above-average school-readiness skills. The investigator urged further development of the AHS program to strengthen its potential to improve children’s social-emotional development and to lower the risk of poor school outcomes. The most positive findings came from parent and community ratings of the culture and language components of the program. The evaluation concluded that one of the strongest features of the NWT AHS movement was its site-specific identity and focus and its dedication to the promotion of local culture, language and traditions. This community collaboration on a multisite program evaluation is a promising basis upon which to build future impact evaluation research (Western Arctic Aboriginal Head Start Council 2006).

Another perspective on the impact of AHS comes from the Regional Longitudinal Health Survey. It indicates that at least one year of AHS reduced the risk of a child repeating a grade in elementary school. The RHS asked parents, grandparents and guardians of children who had and had not attended AHS about their children’s academic performance and whether the children had repeated grades in elementary school. The data suggest that AHS helped children to become ready for school, as measured by grade repetition: 11.6 percent of children who attended AHS repeated a grade; 18.7 percent of children who did not attend AHS repeated a grade. These results suggest the potential of AHS to contribute to early school success.13 Although the RHS does not provide a differentiated view of how AHS affects children or for how long, its findings are encouraging.

More work is needed to establish research-based evidence of the ways in which AHS affects Aboriginal children’s quality of life and developmental outcomes, but the program has a number of positive and promising features that are highly congruent with principles advocated by many Aboriginal organizations.

While some provinces are encouraging the downward expansion of public schools to encompass more programs for preschoolers from three to five years of age, centralizing programs for young children in public schools is not necessarily the most promising approach to resolving problems of access for Aboriginal children. Canadian public schools have”¨yet to prove that they can grasp and effectively address the historically conditioned needs and goals of Aboriginal families and ensure their cultural safety and dignity (Canadian Council on Learning 2007). Programs operated by public school districts tend to reproduce dominant cultural understandings of what children and parents need and should be doing to promote “school readiness” and “success.” The current narrow approach to measuring school readiness in some provinces (for example, British Columbia and Ontario) has generated alarm among AHS program staff, who are concerned that the pressure for preschoolers to develop preliteracy, prenumeracy and English-language skills and to demonstrate personal self-sufficiency at an early age will pre-empt the AHS’s holistic objectives.

Approaches need to be explored for ensuring that early childhood interventions and outcome measures encompass the full spectrum of Aboriginal caregivers’ goals for young Aboriginal children’s development; these approaches would include promoting Indigenous languages, cultural learning and spirituality; facilitating intergenerational relationships; and improving school-readiness skills. Unlike public-school-based programs, the community-based and community-operated AHS programs serve the dual purpose of improving conditions for Aboriginal children’s health and development while contributing to Aboriginal capacity, self-determination and cultural revitalization.

AHS programs are as varied as the cultural communities that operate them. While each must have the six program components, these components can be tailored to the community, culture, goals, resources, strengths and needs of the young children and families who will be using it. Thus, AHS is not a prescriptive, cookie-cutter model, like so many brand-name programs. “One size does not fit all” has been a recurrent theme in the health, education and community development sectors over the past decade. We need to move beyond a positivist, Eurocentric developmental paradigm in our approach to child wellbeing and family structures, and beyond a singularly medical model in our approach to health, and instead embrace an ecological, culturally embedded approach (see, for example, Chandler and Lalonde 2004). Among those working with young children and their families, there is a grassroots movement away from a universalist approach to what children and families need toward a dialogical approach that encompasses parents’ values, goals and strengths. The illusion that there are best practices that can be dropped into any setting is gradually giving way to a search for promising practices applicable in particular settings. In Aboriginal agencies and communities, skepticism has grown toward brand-named programs touted as “best practices” and offered to communities without preliminary focus-group consultation or pilot testing and adaptation to ensure cultural appropriateness.

Policies and program investment strategies to improve the quality of life of young Aboriginal children need to take into account geographic and social circumstances, cultural factors, distance from diagnostic and specialist services, and the different kinds of challenges and assets of diverse Aboriginal communities. This approach was advocated in 2002 by the Romanow Commission, which called for the creation of partnerships across levels of government and for Aboriginal community organizations to reconceptualize approaches to meeting the wellness needs of Aboriginal peoples. It also urged commitments of flexible, longterm funding for Aboriginal communities to innovate and evaluate new strategies that could create equivalency of supports and services between the North and the urban south (Romanow 2002). Similarly, the Canadian Centre of Excellence for Children and Adolescents with Special Needs has advocated new program delivery approaches, new assessment tools and new training to meet the needs of Aboriginal children (Palmantier 2005; Rogers and Rowell 2007).

Family-focused, culturally responsive policy, funding and evaluation frameworks encourage ingenuity, diversity and community initiative (Stairs and Bernhard 2002). Although targets are effective tools in some settings, they can be prescriptive in a way that is out of step with a community development approach. For this reason, Aboriginal practitioners working with young children have taken steps to define Aboriginal criteria for evaluating child care and development programs rather than accepting criteria imposed (top down) from outside their communities (British Columbia Aboriginal Child Care Society 2003). Similarly, some Aboriginal organizations have resisted the imposition of mainstream measures of school readiness — such as the Early Development Inventory (EDI) (Hymel, LeMare and McKee, 2006) — for young Aboriginal children and comparisons between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children. Early education is one element of the holistic approach that AHS and other early childhood programs take in supporting young children’s well-being. However, practitioners are concerned that the EDI will come to dominate perceptions of the effectiveness of holistic programs. Externally defined targets and the tools provided to measure them can distract practitioners, parents and funders from the original intent of the program. Although the full range of community-specified goals for the program always include early learning there are various ways that this can be expressed, and AHS program goals always include acquisition of holistic and culture-based knowledge, pride and Indigenous language; family support; and the development of spirituality and intergenerational relationships. In community development models, communities are asked to articulate targets that fit their circumstances, needs, goals and levels of readiness and to specify indicators of the extent to which self-identified or negotiated targets have been achieved. Defining targets in terms of their measurement criteria would enable evaluation of the extent to which community-driven programs have achieved community-defined objectives.

In informal reports and at gatherings of representatives of Aboriginal organizations involved with children and families, AHS is often identified as the most positive program in Canada for Aboriginal families with young children. Receiving funding to develop an AHS program is a top priority in many communities. However, only approximately 10 percent of Aboriginal children have access to an AHS program, and many such programs have long waiting lists. A recent report by the Advisor on Healthy Children and Youth to the federal minister of health, Dr. Kelly Leitch, calls for an expansion of AHS to cover 25 percent of Aboriginal children (Leitch 2008).

In contrast to the quick fixes that roll out and back with the turning of the political tide, AHS has for over a decade been establishing its credibility in Aboriginal communities, building a cadre of trained and experienced staff, accumulating a wealth of preliminary reports and program examples, and taking some initial steps toward documenting outcomes for children. It is unquestionably the most extensive, innovative and culture-based initiative in Aboriginal ECCD in Canada. Although solid empirical data on its impact on child health and development are not yet available, there is evidence that AHS is already working in complex ways to enhance the quality of family and community environments for young Aboriginal children.

Aboriginal children, especially those in rural and northern Canada, are the least-supported children in Canada in terms of their access to the basic elements of quality of life. Significant inequities persist in health care, housing, access to safe water, protection from family violence, early childhood education and protection of cultural and linguistic heritage. What will it take for Canada to ensure equity and dignity for Aboriginal children? The measures I now recommend draw on the review of the literature and socio-economic indicators presented in the first part of this study as well as the discussion of Aboriginal Head Start and other targeted programs.

Although there have been improvements, data on the life conditions of Aboriginal children are still inadequate in many respects. This hampers policy and program development. The following recommendations would enhance knowledge creation and sharing:

ӬImprovements are urgently needed to ensure that Aboriginal children have adequate housing, safe food and water, protection from environmental contaminants and access to health care. In addition to closing equity gaps, the following steps are recommended:

Although we cannot yet draw conclusions about the impact of programs for the early development of Aboriginal children, the available evidence is promising. The following recommendations underline the need to expand such programs and to give further attention to preparing Aboriginal people for parenthood:

Many Aboriginal people assert that it took seven generations to erode Aboriginal families, cultures, communities and territories, and it will take seven generations to rebuild Aboriginal identities and societies. Canadian government investment in the Aboriginal Healing Foundation has enabled important programs, tailored to local community groups, to aid in the healing process. Given the time it takes to reconstitute strong cultural communities and family structures, federal government contributions to Aboriginal healing programs need to be sustained. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission headed by Justice Harry LaForme is expected to assist in the healing process for the Aboriginal people who suffered atrocities in residential schools, and to enhance the understanding of Canadians in general about the historical events that have created high need among Aboriginal children and families.

Adelson, N. 2005. “The Embodiment of Inequity: Health Disparities in Aboriginal Canada.” Canadian Journal of Public Health 96 (2): S45-S61.

Allen, S., and K. Daly. 2007. The Effects of Father Involvement: A Summary of the Research Evidence. Guelph, ON: Father Involvement Research Alliance; Centre for Families, Work and Well-Being; University of Guelph. Accessed June 14, 2008. https://www.fira.ca/ cms/documents/29/Effects_of_Father_Involvement.pdf

Anderson, K., and B. Lawrence, eds. 2003. Strong Women Stories: Native Vision and Community Survival. Toronto: Sumach Press.

Assembly of First Nations. 1988. Tradition and Education: Towards a Vision of Our Future. Ottawa: Assembly of First Nations.

_____. 2004. Federal Government Funding to First Nations: The Facts, the Myths, and the Way Forward. Ottawa: Assembly of First Nations. Accessed October 9, 2007. https://www.afn.ca/cmslib/general/Federal- Government-Funding-to-First-Nations.pdf

_____. 2006a. Royal Commission on Aboriginal People at 10 Years: A Report Card. Ottawa: Assembly of First Nations.

_____. 2006b. Leadership Action Plan on First Nations Child Welfare. Ottawa: Assembly of First Nations.

Bala, N., M.K. Zapf, R.J. Williams, R. Vogl, and J.P. Hornick. 2004. Canadian Child Welfare Law: Children, Families and the State. Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing.

Ball, J. Forthcoming. “Indigenous Fathers Reconstituting Circles of Care.” American Journal of Community Psychology.

_____. 2005. “Early Childhood Care and Development Programs as Hook and Hub for Inter-sectoral Service Delivery in First Nations Communities.” Journal of Aboriginal Health 2 (1): 36-50. Accessed June 14, 2008. https://www.naho.ca/english/documents/ JournalVol2No1ENG6earlychildhood.pdf

_____. 2006. “Developmental Monitoring, Screening and Assessment of Aboriginal Young Children: Findings of a Community-University Research Partnership.” Paper presented at the Aboriginal Supported Child Care con- ference, November 23, Vancouver.