On May 17, 2005, for the first time in Canada, a provincial election took place on a date set by law, and not by the arbitrary choice of the current premier. British Columbia voters, election officials, potential candidates, party activists, journalists and civic education instructors were all able to plan for the election well in advance.

While this is a breakthrough in Canada, fixed election dates are quite com- mon elsewhere in the world. In this study, Henry Milner assembles pertinent information on the rules regarding election dates in some 40 democracies world- wide: only a quarter has unfixed election dates.

He poses the question directly: Would Canadian democracy be better served if Parliament and the other provinces adopted fixed voting dates, fol- lowing the lead of BC? After examining the standard arguments, Milner finds that on balance the fairness and administrative efficiency of fixed elec- tions outweigh the added cost due to longer campaigns. More importantly, he argues, fixed election dates can be an important element in a compre- hensive strategy to address the democratic deficit. They can help remove seasonal obstacles to voting, reduce voter cynicism at the manipulation of election dates for partisan ends, and attract more representative candidates – especially women – by allowing them to plan well in advance.

Beyond this, fixed election dates could enhance the effectiveness of a vari- ety of measures designed to actively boost voter turnout. The planning and stag- ing of public events, such as seminars, adult education activities, and public information campaigns, to raise interest and involvement in public affairs can only benefit from having the date of the next election in view.

With young people voting less, civics education is a key measure. With fixed voting days, Milner argues, teaching civics can be more effective. In planning the content of civics courses targeting the young people who are about to become citizens, educators would know the dates of the upcoming federal and provincial elections (and thus the deadlines related to nominating candidates, adopting cam- paign platforms, etc.), so they could better incorporate these elements and line up knowledgeable resource people for their classes.

The author makes a series of specific recommendations for changing to fixed election dates for the House of Commons and the provincial legislatures. First, he recommends that a precise election date be adopted (British Columbia adopted the third Monday in May). Second, he argues in favour of early fall for the date, explaining that formal campaigning would thus begin in mid-August, which marks the end of the vacation period and the beginning of the “political season.” Third, in case of a premature election, he recom- mends an arrangement like the one chosen by BC and Ontario, under which the calendar resumes with the next regular election, in the fourth calendar year following the unscheduled election.

What is the likelihood of fixed election dates becoming a reality in Canada? Henry Milner suggests that with some provinces adopting the prac- tice on their own, and given the fact that the federal opposition is prepared to invest political capital in the issue, Canadians could join the citizens of most mature democracies and be voting under fixed election dates in the not-too- distant future.

This is the third IRPP paper in which I address the democratic deficit in Canada. My primary objective here is to explore the relationship between the absence of fixed election dates and the democratic deficit. While the extent to which elec- tion dates are set by law as opposed to being open to the discretion of the gov- ernment may seem a mere technical matter, I argue that it can be an important element in a comprehensive strategy to address the democratic deficit.

In a late-summer 2004 contribution to this series, I focused on electoral reform initiatives in Canada.1 After that paper was published, on May 17, 2005, British Columbia voters were asked in a referendum to approve a new electoral system for their province. Although the 60 percent target was not reached (it was approved by 57.4 percent of the voters), the outcome signalled what the paper had described: electoral system reform had arrived on the public agenda. Canada would no longer be the exception. It would no longer retain the first-past-the- post (FPTP) electoral system inherited from Britain for all its federal and provin- cial elections. This is a remarkable development: just six years earlier, in introducing a collection of essays on alternative electoral systems, I had written that while change had even come to Britain, “Only in Canada, universally [used] as a textbook case of the distortions that FPTP can bring, is there effectively no continuing discussion of the issue” (Milner 1999, 16).

Canadian exceptionalism also emerged in my 2005 paper, which looked specifically at the problem of youth nonvoting (see also Blais et al. 2002). The numbers in that context starkly set out the contours of the democratic deficit. In Canada, more than in most comparable countries, young people are dropping out of electoral participation. The result is that overall turnout has declined steadily and sharply, from 75 percent in 1988 to 61 percent in 2004 — the low- est figure ever, down from 64.1 percent in 2000. Canada has joined the tradi- tionally low-turnout United States, Japan and Switzerland at the bottom of the list. Only the United Kingdom among comparable countries has experienced as precipitous a decline — from 78 percent in 1992 to 59 percent in 2001. Moreover, if the Canadian rate of 61 percent of registered voters were to be con- verted into the percentage of potential voters (the measure used in the US), it would be about 53 percent, which puts us well below the unusually high American 2004 turnout rate of roughly 60 percent (Milner 2005, 2).

While the 2005 paper focused on civic education, it also built on the find- ings of the first paper to consider the appropriate institutional framework in which such education could take place. Such a framework comprised an appro- priate electoral system and complementary rules and regulations concerning media access,2 party financing, information dissemination and fixed election dates. This framework would ensure — and allow citizens and actors to expect — “that legitimate political positions are given expression and representation in the various democratic institutions, from the local to the national and beyond, at a level approximating their support in the population” (17). Fixed election dates, in particular, “would allow those initiating civics education courses, mock elec- tions and other activities that encourage youth voting to plan their programs well in advance” (16).

In this paper I resume the argument. While Bill C-24, which took effect in 2004, has brought Canadian party financing regulations well into the pro- gressive mainstream, there has until very recently been little discussion and no action on fixed election dates. The exception has been British Columbia, which again led the way. The date of the 2005 BC provincial election (which coincided with the referendum on electoral system reform) was not left to the arbitrary choice of the current premier. The date — May 17, 2005 — was set in law shortly after the previous election, in 2001. Thus voters, potential can- didates, party activists, journalists, civics education instructors and everyone else concerned were able to plan well in advance.

While other provinces are considering such a move — at the time of writ- ing, a similar law awaits third reading in the Ontario legislature — the issue has not attracted the kind of public interest that electoral system reform has. This is unfortunate, since fixed election dates, like electoral system reform, is an element in what could be a comprehensive approach to addressing the decline in electoral participation. Yet, compared to electoral system reform, fixed election dates is a relatively simple and straightforward proposition. It has not generated much dis- cussion, perhaps because the standard argument for it is based on removing the advantage unfixed dates give the party in power. And fair treatment of political parties is not a rallying cry likely to mobilize public opinion. Judging by the experience of proponents of electoral system reform, focusing on enhanced popular participation — that is, reducing the democratic deficit — is a more effective means of garnering public interest and attention.

This, then, is the approach I take here to the question of fixed election dates. As I did in my discussion of electoral system reform, I stress the lessons learned from the experience of comparable democratic countries. And, as was the case in that earlier discussion — especially with regard to youth political participation — it turns out that the Canadian situation is distinctive, if not exceptional. Recognition of this fact has generated a willingness to question Canada’s electoral institutions rather than treating them as something to be taken for granted.

Canada’s distinctiveness with regard to setting election dates is unknown, even among those knowledgeable about such matters. We Canadians seldom think about the rules relating to the length of the electoral term, although we do sometimes — especially these days — complain about incumbent leaders fla- grantly manipulating election dates for partisan reasons. But even so, we do not think about changing to a fixed date, assuming, most likely, that all parliamen- tary systems function as ours does, and that changing to a fixed date would entail adopting American-style presidential institutions, with all their drawbacks. This misconception is perfectly understandable, since there is a singular lack of solid comparative information on this matter. A recent groundbreaking work by lead- ing Canadian political scientists André Blais and Louis Massicotte details every conceivable aspect of election law in more than 60 democracies but does not consider the date of the election (Massicotte, Blais and Yoshinaka 2003).

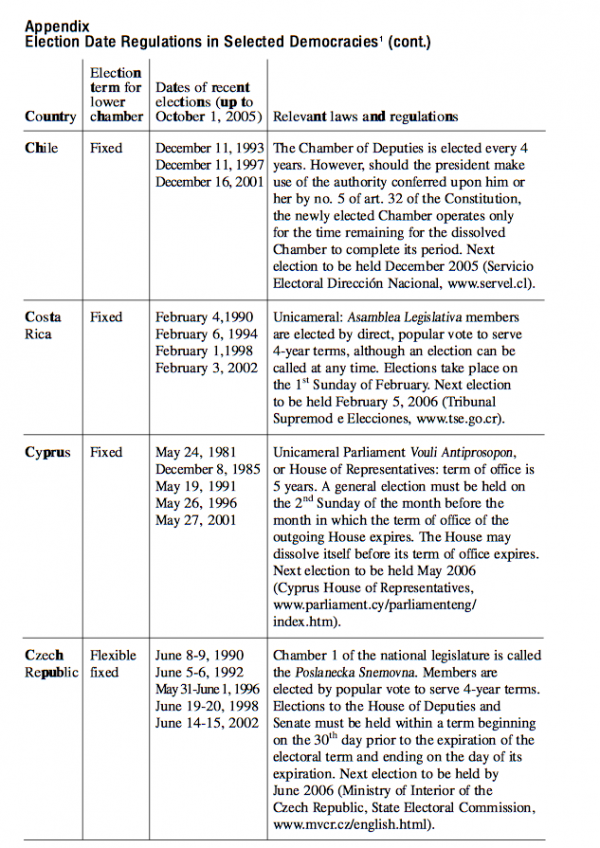

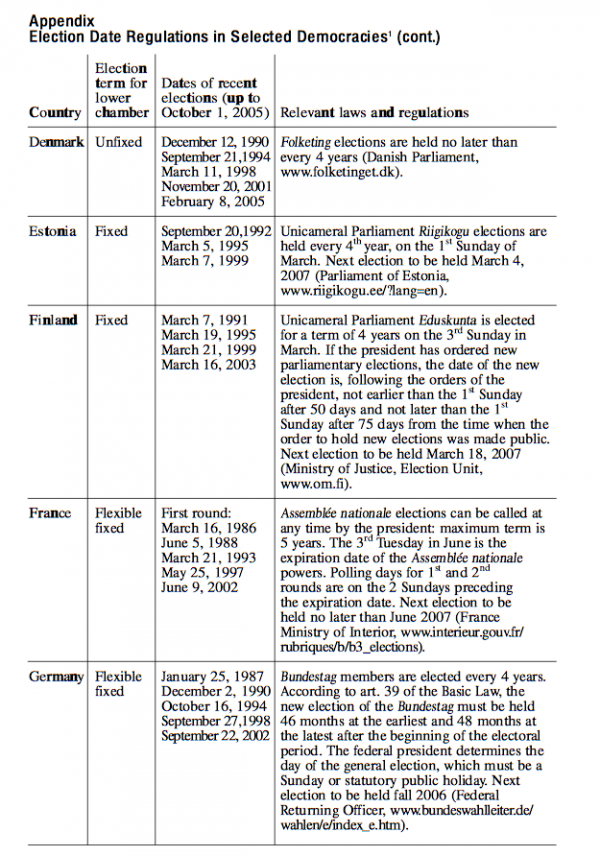

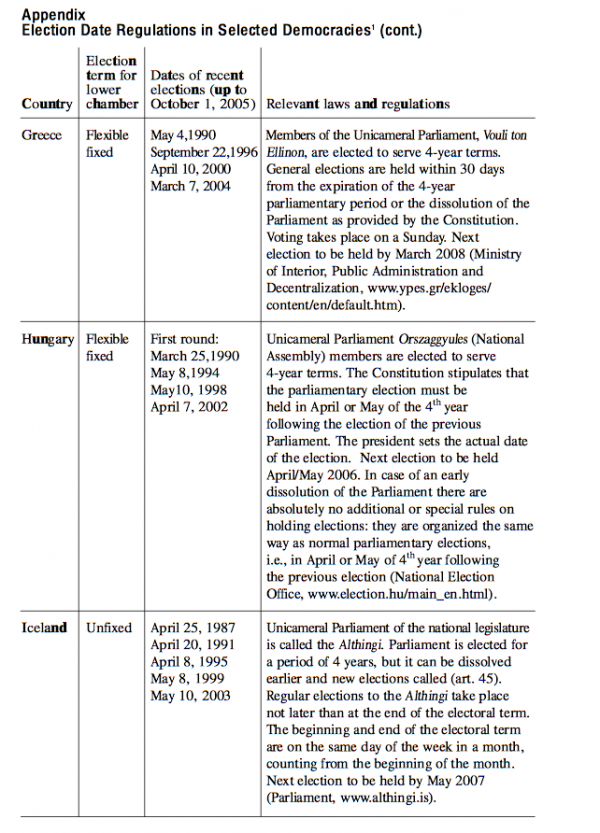

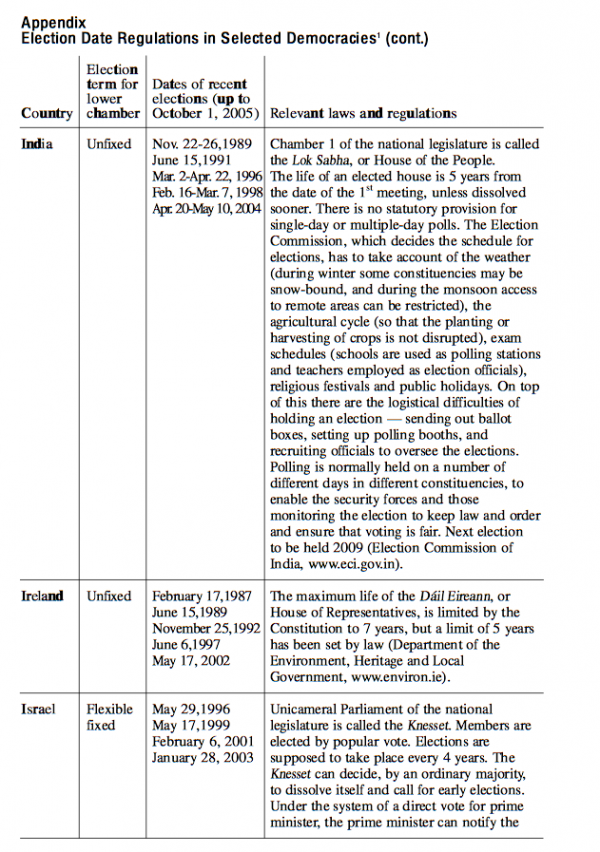

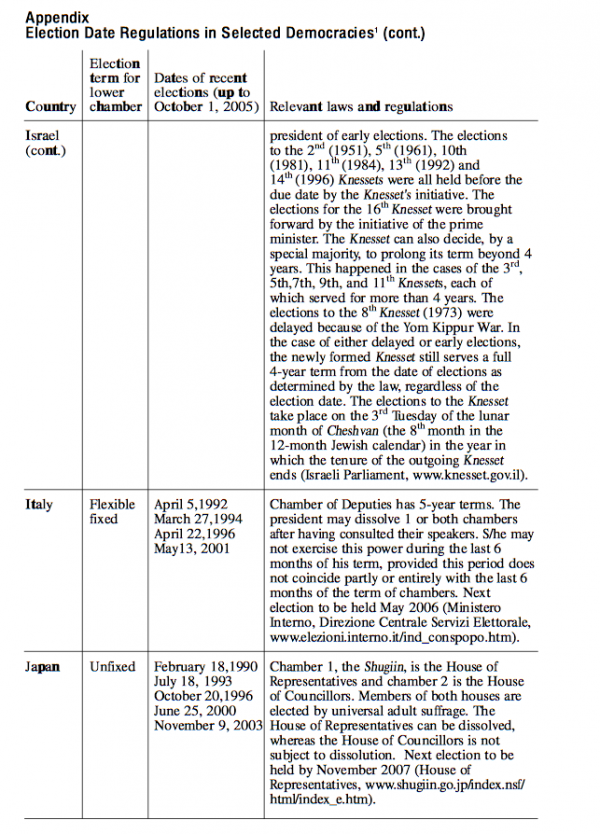

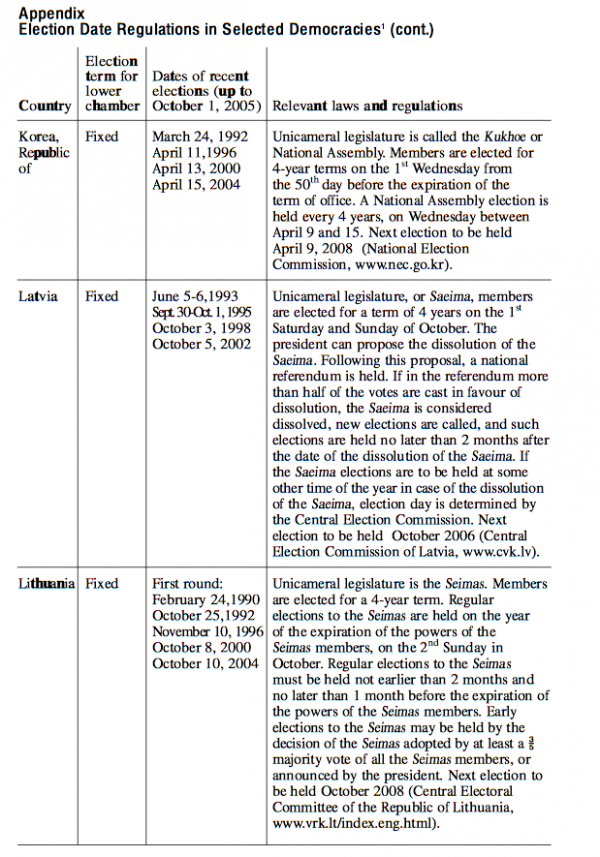

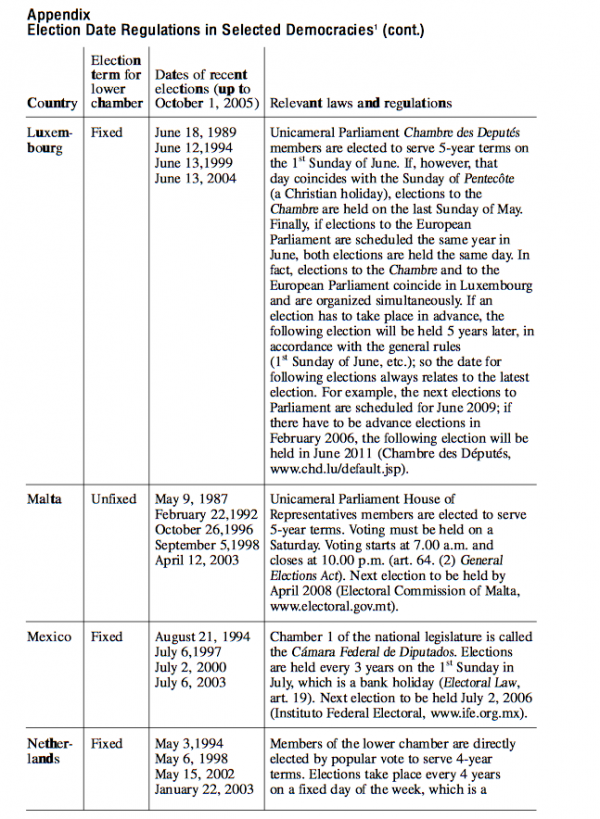

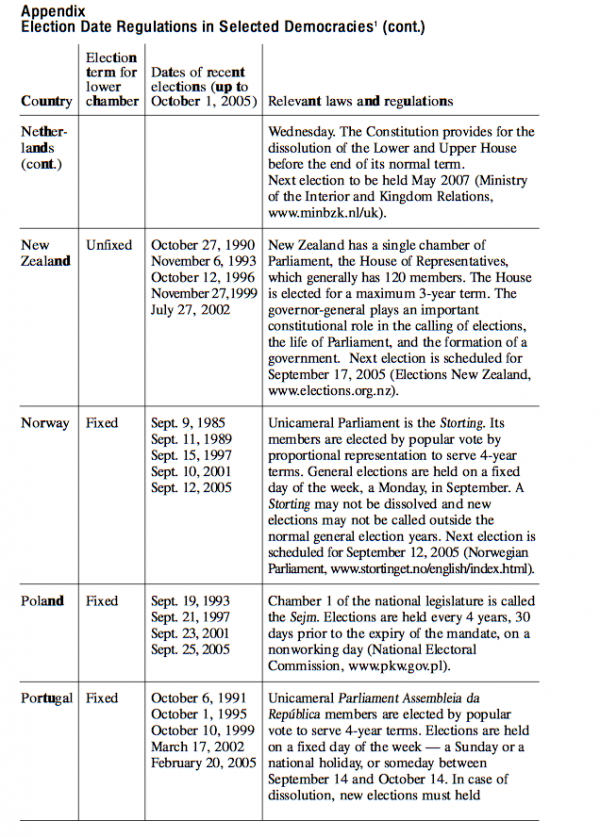

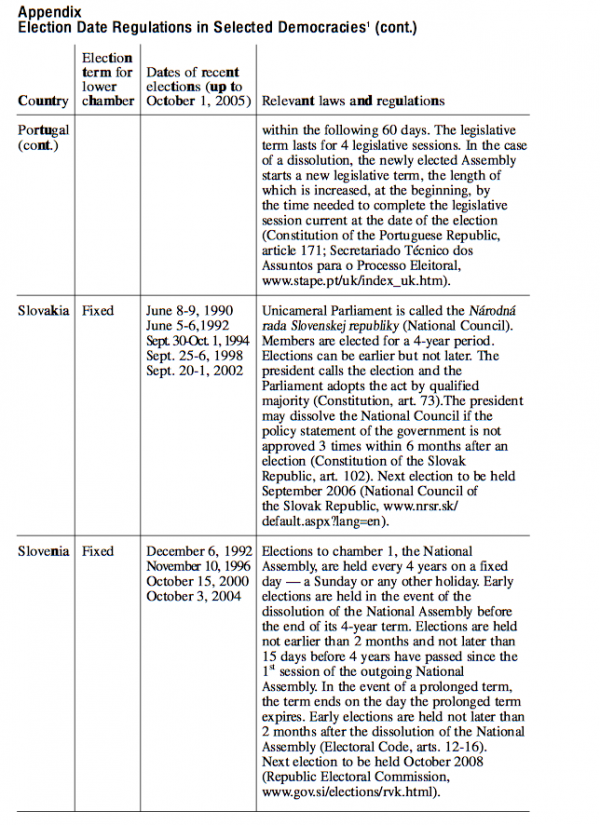

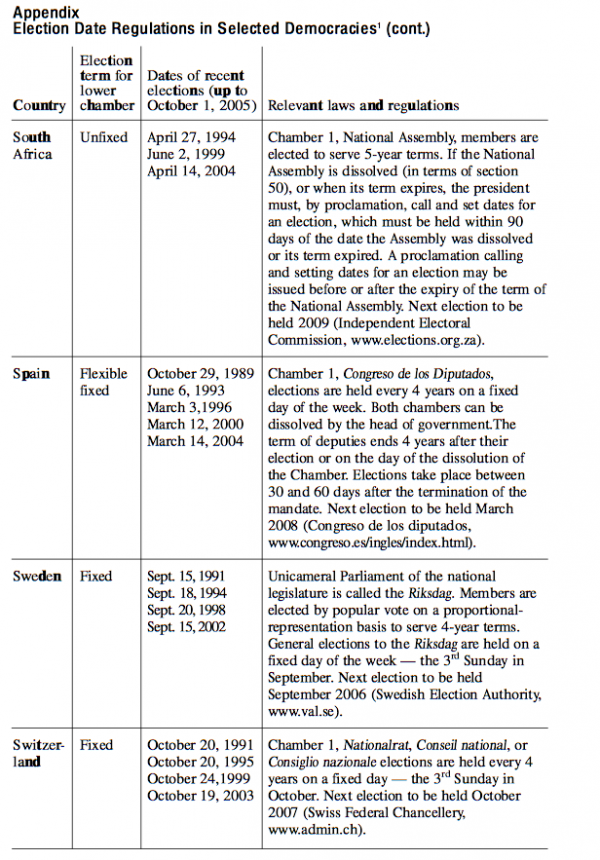

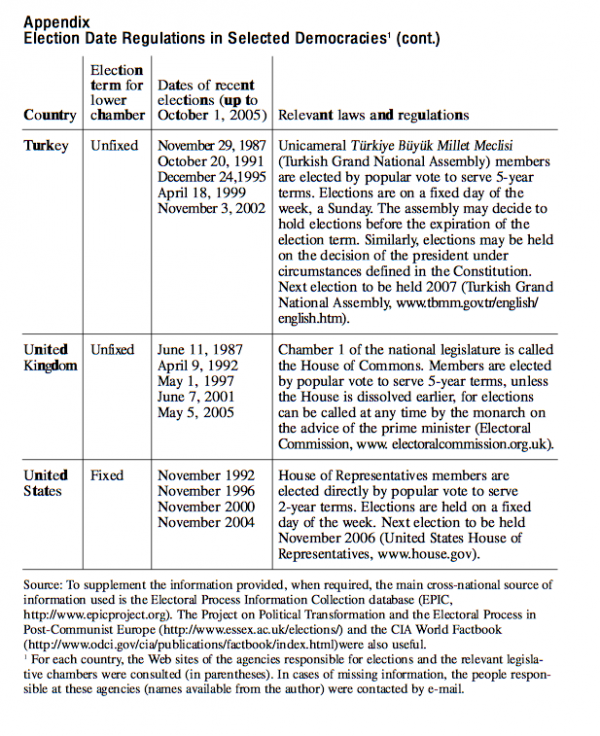

Hence, an important preliminary task here — within the limits of a rela- tively short paper focused on Canada — is to address this misconception. I have assembled the relevant information about the regulations and laws setting elec- tion dates in the 40 democracies most comparable to Canada (in Europe, among the major Westminster countries, and in important stable democracies else- where). I will show that though American-style rigidly fixed election dates are very rare in parliamentary and mixed systems, this does not make unfixed sys- tems the rule. Quite the contrary: in only a minority of these does the head of government (such as the prime minister of Canada) effectively set the election date for the legislature.

We consider first the Westminster countries — that is, those, like Canada, that inherited their political institutions from Great Britain. It is often assumed that these institutions come as a package deal, that you cannot change one without changing them all. Developments during the past 10 years in New Zealand, Scotland and Wales have undermined this assumption, awakening Canadian interest in the pos- sibility of replacing our electoral system within the context of Westminster institu- tions. Once Scotland and Wales followed New Zealand in adopting a form of proportional representation election known as the mixed member proportional sys- tem, it became increasingly evident that, with regard to electoral systems, Canada was a backwater — more Westminster than Westminster itself.

A parallel situation applies with regard to election dates. When Britain cre- ated the new assemblies in Scotland and Wales in 1998, the acts proclaimed that elections take place on the first Thursday in May every four years. In this they were following the lead from down under. While national elections for Australia’s (lower) House of Representatives are unfixed, with a maximum term of three years, the National Capital Territory and three of the six states (South Australia and the two most populous states, New South Wales and Victoria) have fixed terms of four years. In addition, Australia’s senators are elected for fixed terms.

Australia’s senate, like other upper chambers — despite being among the few that are directly elected and exercise any real power — is normally not in a position to force the government to resign. Hence, we limit ourselves to the dates for electing lower chambers and do not look at upper chambers or the (typically fixed) terms of elected heads of state in mixed and presidential systems. We must note, however, that people in countries with such institutions are used to fixed- term elections. In contrast, with an appointed upper chamber and head of state, Canada (before May 17, 2005) was among the very few nations that had no expe- rience of fixed-term elections above the municipal level.

Canada can thus be compared to New Zealand, which has traditionally been described as more British than Britain. But the New Zealand picture has been changing. New Zealand adopted the MMP system for its 1996 election, and it is currently discussing prolonging the parliamentary term, which has brought the question of fixed-term elections into focus. Prime Minister Helen Clark announced on June 14, 2005, that as part of an effort to move from a three-year to a four-year term, she would like to see New Zealand consider a fixed-election- date system like that used in Sweden (“PM Keen” 2005). Were this to happen, as we shall see, it would leave Canada among only 11 of 40 comparable democra- cies that still do not have laws setting out the dates for regular legislative elec- tions. Of course, all these unfixed-election-date countries do provide for a maximum term length and, on occasion, Parliament continues until the date of its automatic dissolution. But this is rare and is in itself a choice made by the head of government.

Countries with only maximum terms of Parliament and no fixed election date set by law are classified as unfixed; but they are not identical, since the head of government’s capacity to exercise discretion is not simply a matter of laws and regulations. Historical and institutional factors come into play. Choosing the date so as to optimize re-election prospects entails the risk of punishment at the hands of voters who view such an action as an abuse of power. The degree of such con- ventional or subjective constraint will differ among societies, even those with the same legal or regulatory environment. These subjective factors cannot be sys- tematically incorporated into the kind of empirical comparative analysis here undertaken, but they should be kept in mind.

We might describe this subjective side as path dependency. If voters are used to elections every fourth spring, then expectations are high and costlier to defy.3 Related to this is an objective factor: the length of the maximum term. Canadian and British prime ministers operate with less constraint under five-year maximum terms than do their Aussie and Kiwi counterparts, with their three- year maximum terms; in Australia and New Zealand, the expectation and incen- tive to take a full term is quite strong. The exception proves the rule. The 2002 election in New Zealand was called a few months earlier than normal — in July rather than in the fall (spring, in New Zealand). The Clark government justified this decision by citing the untenable (and unusual) situation in which one of the parties, the (left-wing) Alliance, found itself. (Two factions of that party had become hopelessly estranged in late 2001. The Electoral Integrity Act compelled them to coexist within the shell of their former party, even though they intended to contest the next election as separate organizations.)4 The most recent New Zealand election reverted to tradition, having been called for September 17, 2005 — one week before the expiry of the term.

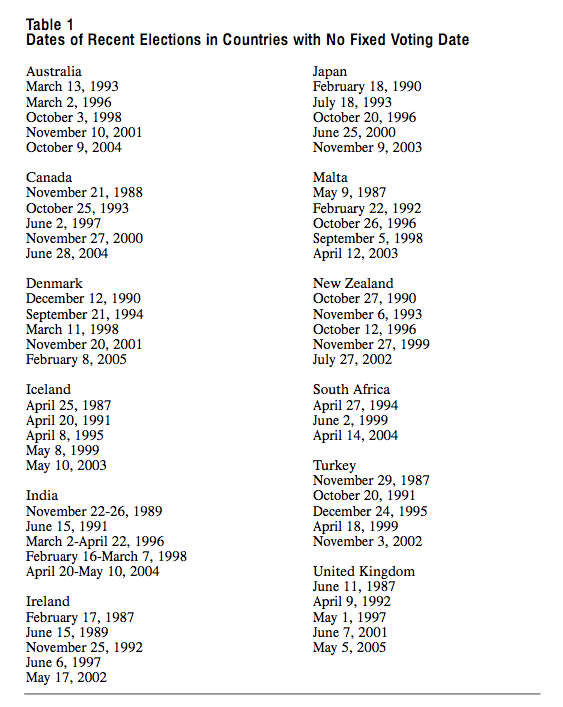

A simple indicator of the effects of these subjective constraints in coun- tries with unfixed election dates can be found in the consistency of the inter- val between, and dates of, recent elections (though clearly other factors — specifically, whether the government is a majority one — will also be reflect- ed). Table 1 sets out the dates of the most recent general elections in the 11 countries. As we can see, Canada, despite the fact that each of the five elec- tions produced a majority government, is among the more inconsistent.

A comparison of the regularity of election dates as set out in table 1 reveals that Canada is one of the most flexible, even among the minority of countries with tra- ditional Westminster systems of unfixed elections. A contrast could be drawn, for example, with Iceland — also formally classified as having unfixed election dates — where elections have taken place every fourth April or May since the premature elec- tion of December 1979. As we shall see, if we place the countries on a continuum of fixed to unfixed, Canada would undoubtedly fall on the unfixed extreme.

As noted, the commonly held assumption that fixed-date legislative elec- tions are compatible only with presidential systems and thus incompatible with parliamentary systems such as ours is inaccurate. Yet this misconception is understandable, since any knowledge that Canadians possess of such matters is likely confined to Canada, the United States and, possibly, the United Kingdom, each being an example of either a “pure” fixed or unfixed system.

Leaving aside conventional constraints, unfixed systems are by their nature pure: that is, by definition they set no rules — beyond a maximum term — limiting the power of the head of government to choose the election date. One cannot make a similar definitive statement with regard to fixed systems. The def- inition of a fixed system as one in which (as in the United States) nothing can be done to alter the date of the next legislative election is too narrow; it excludes any parliamentary system that allows for premature elections — as do almost all of them. It is unrealistic to expect every legislature to be always capable of replac- ing a government that has lost the support of its majority. To avoid a stalemate situation in which no government can be formed, parliamentary systems with fixed election dates, as a rule, make it possible, though seldom easy, to bring about early or premature elections. Typical rules allowing for premature elections impede the ability of opposition parties to force them by, for example, requiring a vote of nonconfidence to be supported by a majority of members, voting or not, or, as is the case in Sweden and Germany, that legislators make an extraordinary effort to vote confidence in an alternative government before any premature elec- tion can be called.

According to Desserud, this opens the door for governments themselves to prematurely force an election by resigning, in effect turning fixed into unfixed systems: “Fixing the election dates under our system won’t work because there are no sanctions that can be imposed on a premier or prime minister who ignores the new rules and requests dissolution regardless…How do you prevent a prime minister from requesting an early dissolution? What recourse is there if the prime minister should do so, despite any imposed restrictions? How, in other words, do you force a government to stay in office?”(Desserud 2005, 52).

If this is the criterion, then beyond the United States and other countries with presidential systems, only Norway5 and Switzerland (though not a parlia- mentary regime) would qualify as fixed-date systems, since they do not provide for premature elections and the circumstance has not yet arisen in which the law has proven unworkable. But such a criterion is too narrow: even if they can theoretically force an early dissolution, governing parties under fixed-date sys- tems very seldom do so. The German 2005 case, in which Chancellor Schroeder’s extraordinary efforts to force a premature election could very well have been frustrated by the president or the constitutional court, is the excep- tion that proves the rule.

In sum, even if they are not pure fixed-date in the American sense, these countries do not belong in the same (unfixed) category as Canada. The reality is that unlike Canada, the majority of countries with parliamentary or mixed regimes set a fixed date for their legislative elections, which is known and, as a rule, respected. In concrete terms, what distinguishes fixed-date countries is not whether they make premature elections possible, but whether they have a law that sets out clear rules for the date on which (or the specific period within which) the subsequent regular election will take place after any such premature election, such that it is known to all. We now turn to these rules.

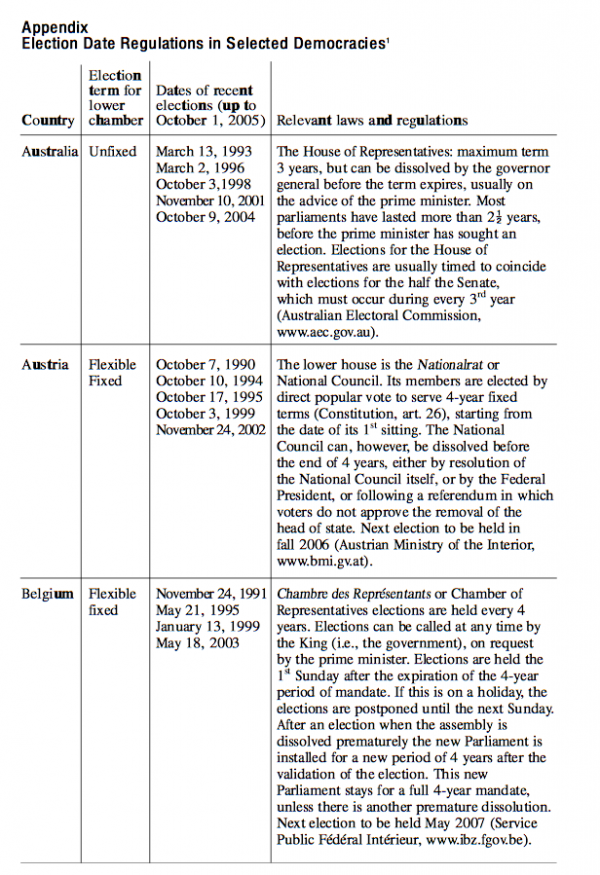

There are several variations in the way the date of the next regular election after a premature one is fixed. The simplest and most fixed variation is found in countries where this date is unchangeable — that is, unaffected by any prema- ture election that may have preceded it. In such instances, limits are also typi- cally set on how late in the regular term premature elections can take place. Finland is a good example: elections to the Eduskunta take place on the third Sunday in March every four years — even if during the previous four years a pre- mature election has taken place. But, to avoid one election falling on the heels of another, no premature election can be held later than the first Sunday after the beginning of the 75-day period before Parliament must be dissolved for the next regular elections.

The second variation is found, for example, in the Netherlands and Hungary. Unlike Finns, who know that legislative elections will take place every four years in March, no matter what, Hungarians know that the next general election will be held in April or May of the fourth year following the election of the previous Parliament. In the former case, it is the actual date of the regular election that is fixed; in the latter, it is the time of year plus the interval since the previous election, whether regular or premature, that is fixed. (This is the varia- tion chosen for British Columbia and Ontario.)

A greater element of flexibility is added under a third variation, used, for example, in Belgium. Here, when the Assembly is dissolved prematurely, the fixed term (of four years) begins when the new Parliament is installed. Thus, though known in advance, the date of fixed elections can be shifted from one time of year to another.

Of the cases described earlier, some are examples of fixed election dates that specify the exact day, and some specify only the period. The extent of this period constitutes a second dimension affecting the level of fixedness. A fairly common practice is to designate a month and day of the week (as in Norway). We have noted that in Hungary elections take place within a two-month period. This seems to be the longest period permitted in fixed systems. Such systems usually specify the actual months and weeks concerned, as in the Hungarian case, but sometimes they do not: the German electoral act, for example, states that the new election of the German Bundestag shall be held on a Sunday or a statutory public holiday 46 months (at the earliest) or 48 months (at the latest) after the beginning of the electoral period.6

One tendency demonstrated by the actual dates of elections is a different form of path dependency: fixed systems generate greater consistency than that required by law. The case of Germany is revealing in this regard. Not only have recent regular elections been held in the second half of September or the first half of October, but also the premature election provoked by Chancellor Schroeder in June 2005 — by the extraordinary measure of having members of his own Social Democratic Party caucus vote nonconfidence in his government — was timed so that an election would take place in the same period, on September 18, only one year early.

Given the variation in flexibility, it would be inappropriate to force all countries specifying a date or period for regular elections into the same “fixed” classification. To be safe, I place countries that allow greater flexibi- lity as to the date and the rules regarding the dates of regular elections sub- sequent to premature ones in a third classification termed “flexible fixed.” In borderline cases, where it is unclear whether to classify a given country as fixed or flexible fixed, I look at the consistency of actual election dates (see the appendix, column 3).

As a glance at these dates shows, elections are more often regular than premature in countries with rigid fixed terms and in those with flexible fixed- term election dates (most of them take place under proportional-representation electoral systems and thus very seldom produce majority governments). The exception is Israel, which is treated as flexible fixed, since that is the legal prin- ciple under which its legislature operates. The dates of its recent elections reflect the fact that the “exceptional circumstances” allowing for early elections have in fact proven not so exceptional. Another possible exception is France, where the powerful presidency appears to weaken the fixed nature of the legislative term. The relevant laws state that National Assembly members are elected for a term of five years, the election to take place in the 60 days leading up to the third Tuesday in June. However, the constitution gives the president of the republic the prerogative of calling an early election; and, in an effort to improve their political positions, this is just what François Mitterrand did in June 1988, and Jacques Chirac in May 1997.7

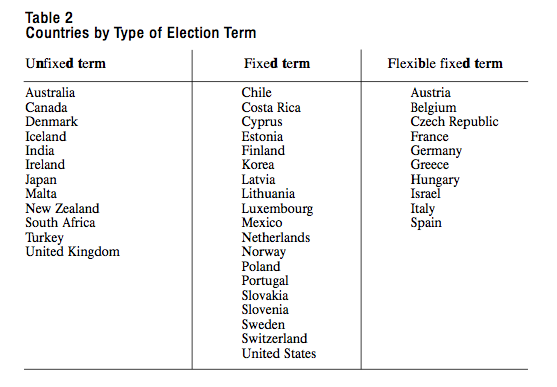

I have assembled pertinent information on the rules regarding election dates in some 40 countries that are comparable to Canada and for which data is available. This information, found in the appendix, serves as the basis for classi- fying regimes (in table 2) into three categories: unfixed, fixed and flexible fixed.

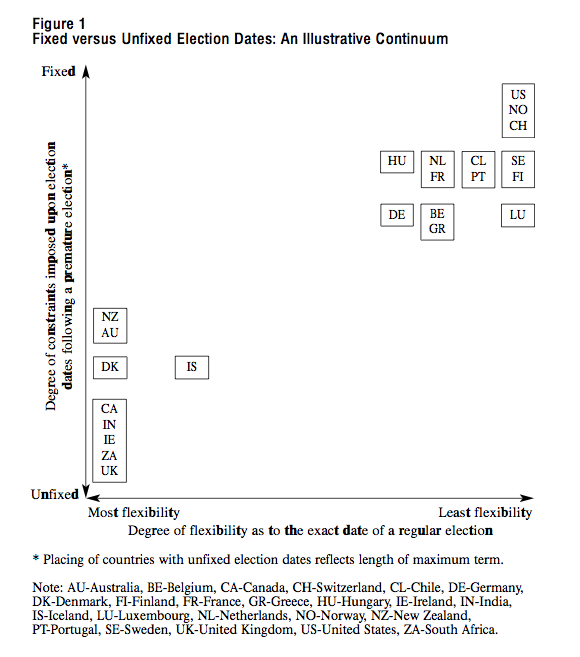

This threefold classification is used because we do not have enough information about the relative position of all 40 countries on the relevant scales to draw a continuum. However, to illustrate the key distinctions noted earlier, figure 1 sets out the positions of a number of representative countries relative to each other on two key indicators: one, on the horizontal axis, the degree to which there is flexibility as to the exact date of a regular election; and two, on the vertical axis, the constraints imposed upon elections following a premature election.

What stands out in table 2 is that even after we have placed Israel, France and eight other countries into the flexible-fixed category (column 3), roughly half the 40 still fall into the fixed-election-date category (column 2) — almost twice as many as in the unfixed category (column 1), where Canada is situated.

Having established the context, we can now pose the question directly. Would Canadian democracy be better served if Canada moved from column 1 to column 2 in table 2 — from unfixed to fixed? In the context of Canada’s parlia- mentary institutions, and compared to the situation elsewhere, what would be the advantages and disadvantages of such a change?

Until recently, like most political scientists interested in political institutions, I gave little thought to the rules concerning election dates. If asked whether Canada’s system of unfixed dates needed fixing, I would have responded that while that system gives a strategic advantage to parties in power, this was a small price to pay, given the cost of adopting an American-style presidential system, with its fixed election dates. My work on Scandinavian welfare states in the 1980s and 1990s gave me an opportunity to observe Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish elections, and I came to realize that parliamentary regimes were in fact compatible with fixed election dates. But this knowledge did not alter my think- ing substantially. I assumed, without bothering to check, that this was just another case of Scandinavian exceptionalism.

Developments in the later 1990s piqued my interest in the question. Invited to join a group of foreign observers of German federal elections, I realized that such invitations could be sent out well in advance only because the date of the next election was known.8 And Germany was a country respected for its innova- tive approaches to political institutions, especially those concerned with election campaigns, parties and voters. All of this coincided with my developing interest in the relationship between political institutions and electoral participation — or the lack of it, especially among young people. As noted in the introduction, it is the possible connection to such participation that sparked my interest in fixed voting dates. Before focusing on that specific relationship, however, we will con- sider those arguments relevant to Canada that have been advanced on both sides of the debate over fixed election dates.9 These are presented under 10 headings.

The standard argument for unfixed elections is that they are a necessary aspect of the parliamentary regime, that our institutions must provide for minor- ity governments (such as the current one in Ottawa) when they lose their major- ity in the house and must go to the people. As we have seen, fixed-election-date systems can and do provide for such an eventuality. But minority governments are the exception. Our FPTP electoral system’s singular virtue is that it produces majority governments most of the time. But, as we see in table 2, countries in northern Europe that exemplify effective proportional electoral systems use fixed- date elections, and (as we can see in the third column of the appendix) they have few premature elections. It is only under FPTP that (as in Canada) premature elec- tions can be expected if no party has a majority of seats. Under proportional rep- resentation (PR), elections typically result in coalition governments that respect fixed election dates. Even when PR produces minority rather than coalition gov- ernments, they tend to act differently than minority governments under FPTP; in the latter case, parties know that the minority-government situation is likely to be short-lived. This is not the situation under PR: provoking an election does not bring majority government, so nothing is to be gained by acting irresponsibly. We can see this in the recent experience of continental European PR countries as well as New Zealand, Scotland and Wales, which recently adopted PR.

The second main line of argument against fixed election dates concerns the cost of election campaigns. Critics contend that the adoption of fixed elec- tion dates would mean longer and more expensive campaigns, with parties vying with one another to get their messages out first. This is a legitimate con- cern, but such an eventuality can be averted by a combination of tight financial controls limiting the period of campaign spending and an appropriate choice of election date. Moreover, there is another potentially countervailing effect: the duration of the formal campaign can be shorter under the fixed-election-date system since the work of the electoral officers can begin before the election is called. This could save money and result in better planning, as was apparently the case in British Columbia.10 In addition, setting dates for by-elections is sim- plified and the overall cost of these elections is reduced, since calling them close to the date of an upcoming general election can be avoided when the date of the next general election is known.

A number of arguments have been advanced in favour of change. The most common critique of unfixed voting dates has to do with fairness. Why should the party in power have a special advantage in planning electoral strat- egy due to its inside knowledge of when the next election will take place? Why should its leaders be permitted to time an election to exploit conditions favourable to their re-election?

Related to the issue of fairness is the fact that governing parties can to some extent also manipulate conditions, through fiscal and other economic policies, for partisan ends. Here the discussion of election dates raises a second tradition- al concern related to electoral institutions — namely, their relationship to the effectiveness of government. In countries with fixed-term elections, the United States in particular, some economists have drawn attention to the so-called polit- ical business cycle — that is, the phenomenon of incumbent governments manipulating economic policy instruments to aid their re-election efforts. Even though we tend to assume that governments spend more money before an elec- tion to generate employment and then make up for it after they come to power, the existing evidence that economies do better before elections, with fiscal pain to follow, is ambiguous (Nordhaus 1975; Golden and Poterba 1980).

If proving the existence of a political business cycle is difficult under fixed election dates, it is even more difficult when election dates are not known in advance. Governments in such a system can manipulate economic policy and election dates so as to face voters at the time most conducive to attaining their electoral objectives. Japanese figures, according to Ito, show that Japan’s unfixed election dates made it possible for the country’s prime ministers to adjust the political cycle to the economic cycle in order to time elections to upturns in the economy (1989). We do not have the comprehen- sive data to test this assertion cross-nationally, but it is clear that parties in power, when given the opportunity, will try to use any system to further their chances of re-election. This window of opportunity is smaller under fixed sys- tems due to their transparency — with election dates known in advance, efforts of governments to buy voters with their own tax money are more obvi- ous. Under unfixed systems, it is only after the election is called that such efforts become apparent.

Fixed elections should allow for better policy planning in the bureau- cracy — more effective investigative commissions, and the like — simply because officials will be better able to plan into the future the use of limited resources, including the time of the participants. A fixed-election system would allow members of parliamentary committees to set out their agendas well in advance, which would make the work of the committees, and the House as a whole, more efficient, given the varying and at times conflicting calls on parliamentarians’ time.

The absence of media speculation over the date of the next election and the various strategic considerations going into it should leave more room for public discussion of the actual issues and priorities.

Removing the prime minister’s capacity to call an election at his or her discretion is especially pertinent in Canada, which is run, in the words of The Globe and Mail’s Jeffrey Simpson, by a “friendly dictator” who, “when it comes to political power inherent in [the] office…now [has] no equals in the West” (Savoie 2000, 31). Unlike their counterparts anywhere else, Canadian prime ministers appoint the members of the upper chamber, the head of state and the members of the Supreme Court. Moreover, incumbent Canadian party leaders are invulnerable. It is inconceivable that what befell Britain’s Margaret Thatcher, Australia’s Bob Hawke and New Zealand’s James Bolger — that is, having the rug pulled out from under them by rivals in caucus — could hap- pen to a Canadian prime minister. Moreover, the fragility of Canadian federal- ism actually strengthens the role of the prime minister, whose office takes control of any issue or policy domain even vaguely linked to national unity. Finally, Canadian prime ministers do not have to deal nearly as much as British prime ministers with powerful ministers who have deep roots in their party and well-established policies and positions on many issues.

By allowing for interested citizens to plan well in advance, fixed elec- tions should make it easier to attract candidates with a greater need to recon- cile possible political careers with other obligations. This applies especially to women and those employed in more traditional occupations. Similarly, a longer period of notice should attract more and better volunteers for campaign-related activities.

Election dates known in advance and chosen to optimize participation should make it easier for certain classes of citizens to make themselves available to vote. This applies especially to potential voters with seasonal constraints, such as seniors and students. In the case of students, it would facilitate avoiding elec- tions on a date when they are in transition between home and school — in early May or September, in particular.

Furthermore, selecting an appropriate fixed date would keep municipal or school-board elections from having to compete for attention with provincial or federal elections, which we know has a tendency to dampen turnout.

In the long term, diminishing the ability of governing parties to manipulate the timing of elections for political or partisan purposes should strengthen public confidence in the political process. In the short term, implementing what will certainly be a popular measure should contribute to reducing the prevailing cynicism toward elections and election campaigns. The Environics Research Group found that “just a week before Prime Minister Paul Martin called the 2004 Canadian general election…81percent of Canadians preferred that elections be held at specific and fixed times, instead of ‘whenever the party in power wants to call [them]’” (Desserud 2005, 48).

The weight of the foregoing arguments at the very least places the burden of proof on those who would retain the system of unfixed election dates in those countries where it is still found. It may very well be that existing conditions or complementary institutional arrangements in another country retaining unfixed elections are such as to justify this system,11 but the burden is too heavy as far as Canada and its provinces are concerned. This does not mean that moving toward fixed voting dates will in itself reverse Canada’s low and declining voter turnout; but it is a necessary component of a systematic effort to address this pressing issue. First of all, several of the previously noted fac- tors affecting the representativeness of candidates, the availability of volun- teers and the reduction of cynicism toward politics can be expected to indirectly boost political participation, at least marginally.

Beyond this, fixed election dates are conducive to the effectiveness of a variety of measures designed to actively boost turnout. The planning and staging of public events, seminars, adult education activities and public information campaigns to raise awareness of, and interest and involvement in, public affairs can only benefit from having the date of the next election in view. This is espe- cially the case with regard to youth participation.

Among the most important of these youth-participation-focused activi- ties are mock elections. Canada’s first large-scale undertaking of this kind this was conducted in 2003 in Ontario; students in 584 high schools cast ballots identical to those used in the October 2003 provincial election. The second such undertaking was Student Vote 2004, which, despite greater financial support and better organization, saw far lower rates of participation. This was due to the fact that the June 28 federal election date was too late to allow for a simultaneous vote. Instead, each school selected an election day. Results were tabulated for 1,168 schools. Clearly, the number of schools was kept down by the lateness and uncertainty of the election date. In contrast, the fact that the voting date was fixed in advance clearly facilitated the latest of the mock elections — namely, Student Vote BC, which took place on May 16, 2005, in 350 schools.12

We do not yet have any direct evidence of the effect of these recent ini- tiatives, but there is some reason to believe that they contributed to revers- ing the downward-turnout trend for first-time voters that seems to have prevailed in the 2004 election. A study carried out by Elections Canada based on a sample of 95,000 voters drawn from electoral districts in every province and territory found that 38.7 percent of those identified as first- time electors turned out to vote (Kingsley 2005), as compared to the (prob- ably low) estimate of 22.4 percent for the same group in 2000 based on a survey of voters and nonvoters by Pammett and LeDuc (2003, 20). The effects of the mock elections staged by Kids Voting USA, a nonprofit, non- partisan voter education program in 39 American states — which, researchers maintain, have been positive, especially on parents13 — are sug- gestive. Efforts like those of Student Vote 2004 to get young citizens to the ballot box14 could also only be enhanced by their knowing, as do their American counterparts, the date of the next election (see Milner 2005).

Finally, and most important, fixed voting dates constitute a key measure — among those identified as required to set civics education in an appropri- ate institutional context — in a long-term strategy of addressing the phenom- enon of youth political dropouts (Milner 2005). In looking at the experiences of countries that have been able to avoid Canadian political-dropout levels, I have stressed the designing of civics courses targeted at young people who are about to become eligible to vote, giving an important place to the positions taken by the different parties on relevant local, regional and national issues. One approach would be to issue regular invitations to party spokespersons to come to the classroom, both virtually (through Internet-based information provided by the parties) and physically; this way, young people can be exposed to another side of those seeking their votes, a side that is potentially more authentic than that provided by the media.

Approached in this way, teaching civics would certainly be more effec- tive within the fixed-voting-date system, since civics educators would be better able to organize their programs well in advance. In planning the con- tent of civics courses targeted at young people about to become citizens and voters, educators would know the exact date of the upcoming federal and provincial elections (and thus the deadlines related to nominating candi- dates, adopting campaign platforms and so on) and could therefore line up knowledgeable resource people for their classes. It is not inconceivable that such a course could be structured to focus in spring on elections to take place the coming fall (or winter/spring) — one year federal, one year provincial and one year municipal. (The fourth year could even concentrate on US elections — if the timing permitted — though this could be going a bit too far.) In such a situation, it should not be too difficult to schedule classroom visits by the appropriate players and to create appropriate peda- gogical support material.

A glance at table 2, which classifies the systems for calling elections for the lower houses of the legislatures in 40 countries, shows that Canada is in the minority in terms of unfixed election dates. British Columbia, with its new fixed-date sys- tem, is in fact in the mainstream and should serve as an example for other provinces and the federal Parliament. British Columbia’s experience will add a Canadian case to those fixed-date systems surveyed here and help us to choose from among the specific measures used in the parliamentary regimes with fixed election dates those best suited to the Canadian context. This would allow us to test tentative guidelines emerging from experiences elsewhere.

Three such guidelines, which we will now look at, apply to modalities related to fixed-date elections: the degree of rigidity about the date; the season and length of term; and procedures with regard to premature elections.

Should the date be completely fixed — for example, the third Monday of every fourth September — or should it be more flexible — for example, during the months of September and October? On this question we can take as our starting point the rule adopted in laws already implemented in British Columbia, about to be adopted in Ontario, and proposed by the New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island electoral reform commissions. In each case, there is provision for precise fixed dates: in British Columbia, the third Monday in May; in Ontario, the first Thursday in October; and in New Brunswick, the third Monday in October. Experience in the coming years should demonstrate to us whether the planning advantages of knowing the exact date outweigh the loss of flexibility to deal with unforeseen cir- cumstances provided by specificying a month or a two-month period.

What season is best? The report of the New Brunswick Electoral Commission noted that, spring or fall, the decision should take into account the dates of municipal elections, the school year, the budgetary process and the dates of any federal fixed-term elections (New Brunswick 2004). Moreover, given Canada’s weather conditions, Canadians’ vacation habits, and the seasonal requirements of seniors and students, there are a limited number of appropriate days in each sea- son. As noted earlier, combined with strict regulations limiting campaign spend- ing to the formal election campaign period, the date selected could reduce the likelihood of overly long and expensive campaigns. Sweden’s choice of the third Sunday in September, for example, corresponds with and contributes to public expectations. Formal campaigning begins in mid-August, which marks the end of the vacation period and, every fourth year, the beginning of the political season.

We could expect an early-fall fixed date to have a similar effect in Canada. Moreover, if we are, as we should be, concerned about growing popular cyni- cism about politics, the fact that legislatures are not in session in the summer is an added reason to opt for such an election date. We would do well to avoid a parliamentary session in the weeks before an election campaign; in such ses- sions, strategies are transparently geared toward improving the parties’ electoral prospects rather than the country’s welfare. A late-February date would also work, except that Canada’s climate, like that of Sweden, makes this a less attrac- tive option.

What happens after a premature election with regard to the next regular elec- tion? British Columbia, Ontario and the New Brunswick Electoral Commission follow international practice in choosing a four-year fixed term. And they take a similar position with regard to the timing of the next regular election fol- lowing a premature one. None choose the Norwegian system of eliminating premature elections. This is doubtless too rigid for Canada. As for the Finnish and Swedish system of disallowing changes to the dates of regular elections, it has the advantage of discouraging premature elections and enhancing advance planning (for example, in setting the curricula of civics education courses), but it could mean more frequent elections. Hence, the arrangement chosen by BC and Ontario — under which the calendar resumes with the next regular election, held on the first Thursday in October in Ontario and the third Monday in May in BC, in the fourth calendar year following the unscheduled election — should be given the benefit of the doubt. Its appli- cation would mean, for example, that if after the next regular election in Ontario, slated for October 4, 2007, the government were to fall, and a pre- mature election were to be held, say, in May 2009, then the following regular election would take place on the first Thursday in October 2013 (rather than 2011). Given the advantages of developing a political season, this seems preferable to the provision — used in Belgium, for example — that would set that election four years after the premature election and thus conceivably move the date from fall to spring.

The upcoming years will serve as a laboratory for testing the effectiveness of these procedures in at least BC and Ontario. In the unlikely event that pre- mature elections become the rule rather than the exception, changing to a more rigid, Finnish-style system under which premature elections cannot affect the date of the next regular election would be one alternative. Under this system, parties are less prone to precipitate premature elections since they cannot put off the date of the election in which they will have to pay the political price of imposing an extra election.

At this point, First Ministers can set the dates of elections to the House of Commons and the provincial legislatures at will. This is a prerogative they are happy to exercise but poorly able to defend if challenged in the public arena. It would thus appear that inertia alone underpins the status quo. We can therefore anticipate greater and perhaps even acceler- ated progress toward a fixed system if, or rather when, the question is widely raised.

As they did in the case of electoral system reform, the provinces will lead the way to fixed-date elections. We have already noted the situations in British Columbia, Ontario, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island; in the latter province, the Electoral Reform Commission recommended in its 2003 report that the province provide “a fixed date for provincial elections or a very narrow window be selected during which an elec- tion may be called” (Carruthers 102). Several provincial opposition parties, including New Brunswick’s Liberal Party, the Saskatchewan Party and the Alberta Liberal Party, have taken positions in favour of fixing election dates (Desserud 2005, 48-9). In Quebec, at the Estates General on democratic reform called by the Quebec government in February 2003, more than 1,000 delegates endorsed fixed-date elections.

Federally, the Conservative Party of Canada has clearly included fixed elec- tion dates among its commitments. Not only did its 2004 election platform, enti- tled “Demanding Better,” promise to hold federal elections on a fixed date every four years, but also, prior to that election, party leader Stephen Harper tabled Bill C-512 in the House of Commons to this effect. After it died on the Order Paper, Conservative MP John Reynolds introduced a second motion on fixed election dates, which was defeated in the House of Commons on April 27, 2004.

With provinces moving forward on their own and the federal opposition prepared to invest political capital, it is possible that Canadians will join the citi- zens of most mature democracies and vote under fixed election dates in the not- too-distant future. It is a matter of building on the momentum in British Columbia and Ontario. While there are no guarantees, compared to electoral sys- tem reform and all the complexities it entails, adopting fixed election dates should be — forgive the expression — a slam dunk.

Let us imagine what would happen in Ontario if the federal government were to join the province in fixing fall election dates — the first being scheduled for the fall of 2009. It would thus come roughly two years after the next election in Ontario, slated for October 4, 2007. That election, in turn, will take place about a year after Ontario’s municipal and school-board elections of fall 2006.15 The overall effect would be to create a political season, a period in the year when pay- ing special attention to public affairs and politics is the norm. This would make attentiveness to politics and voting more a matter of habit than it is now. And recent work has shown that voting is, to a not insignificant extent, a matter of forming the habit while still young (Franklin 2004; Plutzer 2002).

This new context, moreover, is conducive to specific activities designed to develop habits of voter participation. As mentioned earlier, a clear advantage of this would be that civics educators could plan their curricula more effectively, as could organizers of public events, seminars, public information campaigns and the like. Finally, the more traditional advantages of fixed elections — including more and better candidates, better volunteer availability and a reduction of the cynicism engendered by the manipulation of election dates for partisan ends — should improve the context in which such activities take place. In sum, it’s a win- win proposition.

Bennett, Gerry. 2005. “Fixed Election a Boon to Planning for Big Day.” Vancouver Sun, May 5.

Blais, A., E. Gidengill, R. Nadeau, and N. Nevitte. 2002. Anatomy of a Liberal Victory: Making Sense of the Vote in the 2000 Canadian Election. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Carruthers, Norman (2003). Prince Edward Island Electoral Commission Report. Accessed November 25, 2005. https://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/er_ premier2003.pdf

Desserud, Don. 2005. “Fixed-Date Elections: Improvement or New Problems?” Electoral Insight 7, no. 1: 48-53.

Franklin, Mark N. 2004. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Golden, David G., and James M. Poterba. 1980. “The Price of Popularity: The PBC Reexamined.” American Journal of Political Science 24: 696-714.

Golston, Syd. 1997. “Never Too Young: Kids Voting USA.” Civnet Journal 1 (2).

Ito, Takatoshi. 1989. “Endogenous Elections Timing and Political Business Cycles in Japan.” NBER Working Paper 3128. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kingsley, Jean-Pierre. 2005. “Chief Electoral Officer’s Message: The 2004 General Election.” Electoral Insight 7, no. 1: 1-5.

Massicotte, Louis, André Blais, and Antoine Yoshinaka. 2003. Establishing the Rules of the Game: Election Laws in Democracies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Milner, Henry. 1999. Introduction. In Making Every Vote Count: Reassessing Canada’s Electoral System, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

———.2001. “Civic Literacy in Comparative Context: Why Canadians Should Be Concerned.” IRPP Policy Matters 2, no. 2. Montreal: IRPP.

———.2004. “First Past the Post? Progress Report on Electoral Reform Initiatives in the Canadian Provinces.” IRPP Policy Matters 5, no. 9. Montreal: IRPP.

———. 2005. “Are Young Canadians Becoming Political Dropouts? A Comparative Perspective.” IRPP Choices 11 (3).

Milner, Henry, ed. 2004. Steps toward Making Every Vote Count: Electoral System Reform in Canada and Its Provinces. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Nagel, Jack H. 2004. “Stormy Passage to a Safe Harbour? Proportional Representation in New Zealand.” In Milner, ed., 2004.

New Brunswick. 2004. Commission on Legislative Democracy (Lorne McGuigan and Lise Ouellette, commissioners). Final Report and Recommendations. Accessed November 25, 2005. https://www.gnb. ca/0100/ FinalReport-e.pdf

Nordhaus, William 1975. “The Political Business Cycle.” Review of Economic Studies 42: 169-90.

Pammett, Jon, and Larry Leduc. 2003. “Explaining the Turnout Decline in Canadian Federal Elections: A New Survey of Non-voters.” Ottawa: Elections Canada.

“PM Keen for Debate on Four-Year Term.” 2005. Daily New Zealand News, June 14.

Plutzer, Eric. 2002. “Becoming a Habitual Voter: Inertia, Resources, and Growth in Young Adulthood.” American Political Science Review 96: 41-56.

Savoie, Donald J. 2000. “The Prime Minister of Canada: Primus in All Things.” Inroads 9: 37-47.

Sawer, Marian, and Norm Kelly. 2005. “Parliamentary Terms.” Democratic Audit of Australia, February. Accessed November 23, 2005. https://democratic. audit.anu.edu.au/SawerKellyParlterms.pdf

For immediate release – Wednesday, December 7, 2005

Montreal – As Canadians prepare to trudge through the snow to cast their ballots in the second federal election in less than two years, a study published today by the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP.org) argues that adoption of fixed election dates is a key element in a comprehensive strategy to address low voter turnout and cynicism.

Author Henry Milner (IRPP Visiting Scholar and professor of political science at Laval University) shows that Canada is among only 12 of 40 comparable democracies that does not use some form of fixed election dates.

These numbers contradict the widely held misperception that flexible election dates are incompatible with parliamentary systems. In fact, most parliamentary democracies in Scandinavia and continental Europe – including several with Westminster-style systems – have “flexible-fixed” systems, in which election dates are statutorily set, but provisions exist for holding early elections if necessary.

Adopting fixed election dates is “a win-win proposition” according to the author, because it will lead to more responsible governments, reduced elections costs, more fairness, and improved confidence in the political process. He points out that British Columbia has already adopted fixed election dates, and a similar law is currently being debated in Ontario.

“The weight of the foregoing arguments at the very least places the burden of proof on those who would retain the system of unfixed election dates,” says Milner. And public-opinion polls routinely show that Canadians overwhelmingly favour fixed election dates over the status quo.

Milner notes that fixed voting dates are a necessary, but not sufficient, condition to address increasing cynicism among Canadians (particularly young voters), which has caused voter turnout in federal elections to plummet from 75 percent in 1988 to 61 percent in 2004. Fixed voting dates would facilitate organization of civic education programs, mock elections and other tools with a proven track record of boosting turnout. Furthermore, the fact that the party in power would no longer dictate election timing would in and of itself reduce voter cynicism.

The author makes a series of recommendations for adopting fixed election dates for the House of Commons and the provincial legislatures, including:

“Fixing Canada’s Unfixed Election Dates: A ‘Political Season’ to Reduce the Democratic Deficit” is the latest IRPP Policy Matters released as part of the Institute’s Strengthening Canadian Democracy research program. It is available on the IRPP Web site, at www.irpp.org.

-30-

For more information or to request an interview, please contact the IRPP.

To receive the Institute’s media advisories and news releases via e-mail, please subscribe to the IRPP e-distribution service by visiting its Web site, at www.irpp.org.

Founded in 1972, the Institute for Research in Public Policy (IRPP.org) is an independent, national, nonprofit organization based in Montreal.