This study is also available in French.

Parliament, the central institution of democratic control, plays several roles in the annual budget process:

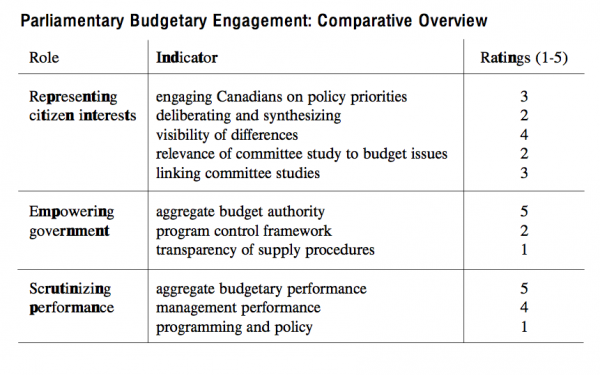

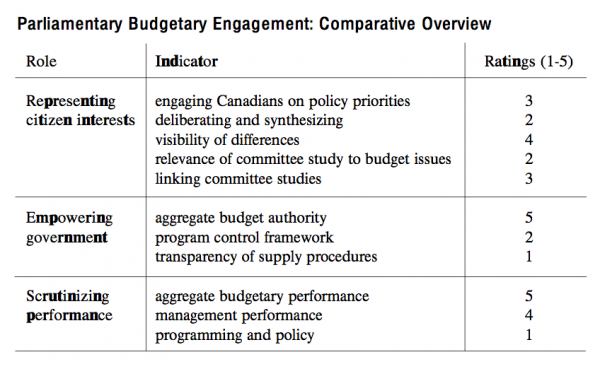

The paper describes how Parliament carries out each of these three roles. It summarizes the findings from a review of all House of Commons committee reports tabled during 2001 and also the views of a sample of com- mittee Members. The findings are organized around indicators of perform- ance. The ratings – five being best and one worst – provide an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of Parliament’s engagement in the budget process.

The findings point to three important areas needing attention:

a) a more understandable financial control framework for supply so Members know what they are voting for or against; and

b) improved scrutiny of the effectiveness of programs for those committee studies aimed at influencing budget decisions;

c) improved means to engage citizens on budget and program matters.

This study also suggests that parliamentary committees take a critical look at their tasks and objectives to assure themselves that they are getting the great- est value for Parliament and Canadians from the substantial time and resources invested. One way to begin would be for committees to periodically report on their own performance.

Democracy and parliaments are vigorously promoted as essential for freedom, for reliable economic development and for enabling citizens to play a role in governing themselves. Yet, headlines and editorials increasingly assert that the Parliament of Canada is becoming weaker, even irrelevant. Is Parliament in fact playing a lesser role? How well is it fulfilling its various roles and how important is this for democracy? What information would help to answer these questions?

This paper addresses these questions by looking at the recent performance of the House of Commons as related to the annual budgetary process. It provides information on Parliament’s engagement, outlines expectations about Parliament’s role, and suggests indicators to help organize observations and evi- dence. It looks at Parliament and the executive as important institutions in dem- ocratic governance, not as alternatives or adversaries.

According to the OECD, budgets have become a government’s most important instrument for setting policy, as well as a key instrument of democrat- ic control.1 By focusing on budgeting, we limit the scope of analysis, but still deal with a subject sufficiently important to explore the feasibility and value of using indicators of parliamentary performance.

Before looking at information on parliamentary performance and effectiveness, it is important to sort out some core ideas and terms — how to talk about budg- ets, Parliament and performance. The intention is not to develop new terms but rather to select and describe those most suitable to understanding performance.

A budget is the government’s key device for converting its obligations, promises and policy into concrete and integrated plans — what actions are to be taken, what results are to be achieved, at what cost and who will pay how much of the cost. The budget connects a government’s aspirations with its analysis of affordability. Its significance arises largely from the difficult choices it faces. In preparing its budget, a government tries to capture all the complementarities among its programs in achieving its overall objectives, but ultimately it must choose — among social and economic groups, among regions, and between today and tomorrow.

The process associated with preparing and implementing a budget includes the policy and management analyses needed to take decisions, as well as actions related to implementing them. These actions include adjustments to mandates, objectives, resources and practices that are put in place to ensure the realization of plans and the tracking of performance — the management side. The actions also include seeking public understanding and support, obtaining parliamentary approval, reporting on performance, and responding in accounta- bility sessions — the governance side.

Decisions related to tabling a budget in Parliament and managing its implementation are the responsibilities of the executive; those related to gover- nance — democratic control — also involve Parliament. To address the issue of democratic control, we need to understand the roles of Parliament and how these roles apply in the budgetary process.

Canada’s form of governance is typically described as a representative democracy with a Westminster-style Parliament. In such a system, it has become conventional to think of Parliament as having three fundamental roles: empow- ering government (often called legislation), scrutiny and representation.

All three roles are at play in Parliament’s engagement in the budget process, but are here reordered to follow the natural cycle of the budget process beginning with representation — advising.

As is evident from the foregoing, much of Parliament’s engagement on the budgetary process takes place in committees. Accordingly, the work of commit- tees will be an important source of information for the analysis of all three roles.

The pre-budget process offers an opportunity for Parliament to exercise its con- sultative and advisory role. This is where Parliament helps define the public inter- est and the public policy agenda. As the most representative and democratically legitimate institution in our governance system, Parliament is in a position to play an important role in interpreting the evolving state of society and the effectiveness of current government policy, and to deliberate on these matters. As a result, it has an informed perspective on the contemporary agenda for action and on the important issues to be addressed. Doing this in open consultation with citizens adds further to the quality and legitimacy of its views of the public interest.

It is important to note that such consultation and deliberation by Parliament does not reduce the role of executive government. The budget in our system must be the government’s budget — for which the executive is fully accountable. It is the executive that decides what advice to take; the executive can articulate why it rejects certain proposals, just as opposition parties and oth- ers can explain why they disagree with the government. When Parliament is vis- ibly and actively engaged in the process of deliberating these matters, it is play- ing its representation role — whether or not its advice is taken.

The extensive consultations conducted by the Finance Committee are the most visible aspect of Parliament’s involvement in the pre-budget process. However, the work done by Members in other committees and at other times to consult with citizens, to articulate the public interest, and to recommend pro- gram and expenditure changes is also important. The pre-budget period brings together the different pieces of committee advice into a package that also takes into consideration broad economic and affordability issues.

Until 1993, the preparation of the budget by a minister of finance was shrouded in secrecy, perhaps because budgets until then focused more on changes to taxation. Since then the budget has played a growing role in limiting and ordering spending. The Minister of Finance has opened up the government’s pre-budget consultation process, has made evident the sources for the essential economic forecasting information, and has engaged the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance in undertaking consultations with Canadians on budgetary issues. At the same time, successive Presidents of the Treasury Board have led initiatives to improve information from government departments on results planned, how these results are linked to planned expenditures and on actual performance.

There can be little doubt that the budget hearings of the Finance Committee have been a positive development. During the 2001 pre-budget exercise almost 250 groups and individuals were consulted. Although there was a strong align- ment between the recommendations of the Finance Committee and the subse- quent budget, the alignment of actions and recommendations should not be over- emphasized. The broad lines of the government’s intentions were reasonably apparent in advance and there is no automatic connection between what a com- mittee hears and what it recommends.

More importantly, the work of the committee appears to contribute to a bet- ter public understanding both of the government’s agenda and the public’s inter- ests. In comparison with earlier experience, there now appears to be greater pub- lic understanding of budgets. While this greater acceptance is the result of sever- al factors, the efforts of Parliament are almost certainly a positive contribution.

The pre-budget consultation work of the Finance Committee focuses on the level of aggregate spending, tax policy and deficits/surpluses, not on the detailed allocations to a department and the specific results it seeks to achieve. While considerable information on specific programs surfaces during the Finance Committee’s consultations, the primary source is ordinarily the studies of the relevant standing committee.

During 2001, 19 committee reports had budgetary implications — that is, they made recommendations proposing altered resources or results.2 Six of the 19 contained recommendations that, while proposing additional government ini- tiatives, likely could be handled within current resource allocations, as they dealt more with results and how resources are used than with changes in resources. The Finance Committee report and 12 other reports recommended additional spending or initiatives implying additional spending.

It should be noted that most of these 19 reports were not tabled in the pre- budget period, and appear not to have been written with the budget directly in mind. Several, for example, also focus on scrutiny. Yet they do include recommen- dations, which if accepted, would change either the planned results or the resources proposed in the budget and estimates. For this reason, the content of the reports and the information used by the committees is described in this section.

The essence of budgetary decisions is to find the best package of results meeting contemporary public interests, consistent with what is affordable. Thus, information linking costs and results and information on how results of pro- grams align with current and evolving societal conditions is particularly relevant. The committee reports were examined from this perspective.

Twelve of the 19 studies began by looking at societal conditions, or recent changes in these conditions. Some went from this analysis directly to recommen- dations; others looked to varying degrees at current government programs and policy. Regardless, they almost always identified the need for additional action — i.e., enhanced or new programs. The remaining seven studies began from the per- spective of existing programs and looked at their adequacy and effectiveness in terms of government commitments or current societal conditions. Of those seven, three went on to propose significant expansion of the programs studied.

The differing perspectives adopted in studies seem to influence the propen- sity to recommend program or spending expansion. Where societal conditions were the dominant focus, expansions were frequently recommended. Studies that focused on programs and their effectiveness tended to recommend program improvement as often as expansion. While this may not represent a pattern, the Finance Committee did recommend that committees filter their recommendations through the 1994/95 Program Review’s “six questions” — public interest, role of government, federalism, partnerships, efficiency and affordability.

Few of the studies examined both results and resources or commented on the effectiveness of the government’s programs. A potential source for such infor- mation is the departmental planning and performance reports, but there was lit- tle reference in the 19 committee reports to the use of this resource. Based on dis- cussions with committee members it is clear that, while they are aware of them, they rarely see the departmental planning and performance reports as a conven- ient source of information for committee studies. This could be due to the nature of their studies, weaknesses in the departmental reports or inadequacy of staff resources.

Another potential source for information is the reports of the Auditor General. Although the Auditor General focuses on financial management and administration, rather than program need and effectiveness, these reports are used by committees in their own studies. For example, the testimony of the Office of the Auditor General plays a prominent role in the 3rd Report of the Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs. Also, the Office of the Auditor General is listed as a witness in three additional study reports.

Engagement of citizens is a further important factor. Seventeen of the 19 committee reports list the individuals and organizations consulted during their respective hearings. In total, 600 organizations and 37 individuals were consulted. While there is some overlap in the organizations consulted, committee work evi- dently involves contact with many Canadians. It is not clear how representative of Canadians’ interests are the organizations consulted — some Members observed that there is a tendency to hear the same messages from the same interest groups who seek to be heard, which raises questions about the balance of representation.

Finally, there is the question of the quality of the deliberation and consen- sus building within committees. Although most participants and observers are critical of the quality of committee deliberation, there is no agreed-upon method to describe this. What can be measured in committees is the growing number of minority reports and the increased use of roundtables of witnesses. The use of roundtables — beyond extending the coverage of witnesses — serves to provide a diversity of views and to encourage debate within committees. At the same time, minority reports and a lessened tendency to articulate differences of opin- ion within committee reports appears to indicate a decline in deliberation and consensus building.

It is important to emphasize that the foregoing observations are not criti- cisms of either the quality or the value of the study reports; the observations sim- ply outline the kinds of information that the reports contain as related to the kinds of information that are implicit in budget deliberations. However, when committees do seek to have influence on budgetary decisions through a com- mittee study, these are matters that need to be considered.

Clearly many things work well and many do not. The following informa- tion and observations focus on the degree to which Parliament: a) engages citi- zens in defining their interests; b) deliberates and synthesizes their views; c) ren- ders visible the differing views; d) reports findings relevant to analysis of budget issues; and e) aligns its committee work to provide a balanced and representative perspective.

Engaging Canadians on public priorities: Members devote considerable effort to consulting and listening to constituents. A strength of committee studies is their openness to hearing citizens and their organizations. Yet it would appear that this openness still falls short of Canadians’ expectations, as perhaps it always will. Nevertheless, a number of Members consider that the package of tools avail- able to them, particularly in light of the potential offered by modern technology, is inadequate.

Deliberating and synthesizing: A key feature of representation is deliberation — speaking, listening and responding — to articulate priorities and seek consensus, and where this is not possible to clarify the issues. In a country as large and diverse as Canada, having a legitimate and representative body finding and articulating common interests in an open way is particularly important. Debate on the floor of the House of Commons rarely plays such a role, whereas committees can and at times do play such a role, though rarely in a visible way. Media coverage of com- mittee hearings has declined and only recently have steps been taken to provide tel- evision facilities in a second committee room. Moreover, a number of Members noted that committees now seem to devote less attention than they did earlier to seeking consensus. Party caucuses work to reach common ground, but they are nec- essarily less representative and the deliberation does not take place in public.

Visibility of differences and options: In democracies public differences of opinion are expected and are seen as important to public debate. The comple- ment of finding consensus is making visible the genuine differences. Differences among parties are visible on the floor of the House and increasingly in commit- tees, principally through the growing number of minority reports. A weakness of minority reports by parties is that they can be seen as an instrument of party mar- keting, rather than representing genuine differences among the interests of Canadians. Articulating points of difference in a consensus committee report — a practice used more frequently in the past — would highlight when committees were in agreement and also illuminate the differences.

Relevance of committee study to budgetary issues: The central issue is the degree to which committees study the links between programs and societal con- ditions while also addressing and analyzing the links between results and resources. Although committees pay considerable attention to changing societal conditions, they have not vigorously reviewed programs or their effectiveness. In addition, committees rarely use departmental performance information that might well help make these connections. Nor do they recommend specific improvements to this potentially important source of information.

Linking committee studies: Budgeting is inherently horizontal, as are the interests of citizens. Committee studies tend to focus on issues from the per- spective of a specific department or agency — that is, from a vertical perspective. This indicator assesses practices to provide more integrated and balanced budg- etary advice. The timing and nature of recommendations in committee studies indicate that six committees targeted their reports for the pre-budget period. Most of these reports dealt with matters related to September 11 and there was a consistency to their recommendations. It would appear that these events led to enhanced consultation among the chairs of committees working on related poli- cy areas for a period of time. This experience suggests that better procedural con- nections among the committees developing budgetary input might help align their recommendations and provide for a more representative package of advice from Parliament. It also suggests that the co-ordination practiced for a period of time after September 11 might be a useful model.

The empowering and scrutiny roles of Parliament are, in a sense, mirror images of each other. Parliament provides the authority and resources to the government to achieve certain things in a certain way, and through scrutiny finds out how well government has done.

In management language, the act of empowering is analogous to estab- lishing a “control framework” — the things we do to assure ourselves that those we entrust with power and resources use them as we intend. These things can include documenting the specific results to be achieved, the performance infor- mation that we require and placing constraints on the application of resources to specific activities. Establishing the “parliamentary financial control framework” is complex since, in addition to the budget and supply process, it includes expen- diture authorities in ordinary legislation (currently over 60 percent of annual expenditures are so authorized). Administrative legislation, such as the Financial Administration Act, provide for specific controls, measurement obligations and reporting requirements. To maintain the focus on the budgetary process, we will exclude these broader matters from further discussion here.

What remains is parliamentary action related to approving the aggregate budget proposals, reviewing the estimates and supply. The House has explicit procedures for considering the aggregate budget including among other things speeches by party leaders. The tabling of the budget also attracts considerable media attention. It is easy for interested citizens to be informed of the content, the societal context and the different options. In addition, changes in taxation affect large numbers of citizens and also attract considerable attention. Provisions for reporting on aggregate financial performance also provide for a high level of visibility.

Empowering the government at the level of departments and programs is much less visible. The government, through the published estimates, provides an extensive package of information. The principal parts, for all departments and programs, are:

In addition, the government proposes up to three sets of supplementary estimates each year to further spell out its expenditure plans and this package of documentation sets out the government’s plans for responding to the public interest, consistent with the aggregate budget. Parliament, for its part, is expect- ed to understand the plans, to concur or propose changes, and to assure itself regarding the provisions for controlling the application of the funds.

A constraint in Westminster systems is that expenditure proposals in budg- ets are often treated as matters of confidence, and therefore a defeat in Parliament on a budget provision is seen as a defeat of the government. Accordingly, the degree to which estimated expenditures are changed in the parliamentary con- sideration process, at least in majority parliaments, would not be a good indica- tion of effectiveness. However, other aspects of parliamentary control, such as the information needed to demonstrate performance, have not been treated in the same manner. In some cases, the government has asked for Parliament’s views on such matters.

Another feature that should be noted is the complexity of the material. In the federal government there are more than 80 different departments and agen- cies, each with distinct programs. There are over 200 individual votes. In addi- tion, there are different supply periods and supplementary estimates, and sever- al thousand pages of documentation. At best such detail could only be dealt with in committees where estimates documentation is automatically referred. In large measure, therefore, Parliament’s effectiveness can be seen in how committees deal with this material. This parliamentary process is called “the business of supply.”

Parliamentary supply procedures force adherence to a strict timetable. Where committees do not report by the deadline — May 31 — they are deemed to have done so. There is an expectation that ministers should attend committee hearings when so invited, and many do. However, Members and other observers note that the discussions at committee hearings, particularly when ministers appear, frequently digress from the department’s program towards topical policy or operational issues. These hearings rarely enhance a committee’s understand- ing of planned results, costs and how such results are related to the government’s policy agenda.

During the 2001 calendar year, 10 reports of committees were tabled as part of the estimates and supply process. Only one dealt only with a performance report (discussed later). Of the nine other reports directly linked to the estimates, all but one were pro forma reports containing no recommendations. The one substantial report summarized relevant material drawn from earlier committee studies and rearticulated earlier recommendations for changes to departmental plans, but not the current year estimates.

Committee activity as a whole, accordingly, adds very little to either the understanding of the government’s plans or to specifying how Parliament might best be informed on the resources it supplies. Actual voting on supply in the chamber provides little, if anything, more.

These findings are not at all surprising. As documented elsewhere, includ- ing in the Catterall-Williams report (The Business of Supply: Completing the Circle of Control, 51st Report, 35th Parliament, Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs), this is an area where parliamentary performance is very weak. The usual explanations for this situation are that the supply procedures do not provide members any opportunity to influence anything and that the informa- tion and the process are too complex to understand.

A recent initiative to have two estimates selected by the Leader of the Opposition debated for up to five hours on the floor of the House could add vis- ibility and might attract additional committee attention. But relative to the pro- posed reasons for inattention, the change would not seem adequate. However, implementing certain of the Catterall-Williams proposals might well have an influence. For example, the creation of a House of Commons committee or another body to monitor the supply process and to work with the government on rendering the parliamentary financial control framework more accessible could lead to more substantial changes over time. A further suggestion is to encourage committees to invite the Auditor General to brief them on the depart- mental estimates under review.

Except for macro-fiscal matters, the empowering role of Parliament as related to the budgetary process seems particularly weak.

Macro-fiscal control practices: Although there are some issues, such as the appropriateness of using very conservative fiscal forecasts, Parliament and polit- ical parties pay attention to the aggregate budget and the public seems signifi- cantly engaged.

Program control framework: The business of supply defines the specific bundles of activity for which Parliament provides resources, as well as the spe- cific purposes and ways departments can use these resources. Through their con- sideration of supply, committees can spell out the kinds of information they would like to see in order to judge the effectiveness and needs for such spend- ing. Committees can further influence the framework of control by the nature of their scrutiny of the estimates. Together, these mechanisms are Parliament’s con- trol framework. While many weaknesses were outlined above, it also is impor- tant to note the potential strengths. The government provides considerable infor- mation. There are over 200 individual votes to provide authority for approxi- mately one-third of the government’s annual expenditure, and there are provi- sions for Parliament to play a more active role if it so chooses. But from the per- spective of democratic control, the dominant factor is that Members do not engage in understanding plans proposed by government and exercising their influence in this way.

Transparency of estimates/supply procedures: Members consistently note the complexity of both the process and the documentation. It is to them virtually impenetrable. Control procedures which are not understood and which are too complex do not contribute to democratic control.

Question Period is often perceived as the core of parliamentary scrutiny. While it is important, it rarely focuses on budgetary decisions and implementation, but rather on operational administrative issues, ministerial activity and commentary on issues raised by the media.

The second most visible area of scrutiny is the work of the Auditor General and the Public Accounts Committee. The Auditor General investigates compliance with the parliamentary financial control framework, comments on the quality of government performance reporting and identifies areas of inad- equate attention to value for money. The Auditor General is an officer of Parliament, independent of government, and has the resources to undertake in-depth studies. The subsequent review of the Auditor General’s reports by the Public Accounts Committee further adds to the visibility and impact of these reports.

The work of the Auditor General and the Public Accounts Committee is central to parliamentary scrutiny related to the budget. This process, however, does not extend to two key questions essential to budget scrutiny: the effective- ness of programs in terms of government objectives, and the need and priority of programs in relation to evolving societal conditions.

Questions of effectiveness and priority require in-depth study by a com- mittee to develop a good understanding of:

a) the expenditures, intended and actual results, and the programming approach adopted by the departments and agencies involved;

b) related (complementary or conflicting) programs in other departments; and

c) the societal conditions that give rise to the need for such programs and how those conditions are evolving.

Views of constituents as taxpayers, users and beneficiaries of programs are a good source for information on performance, as is the media. A further source of information is government itself, through reporting, electronic access and direct contact. The most significant change in recent years has been the increased access to information provided by departmental websites and by the departmen- tal performance reports. In addition, the government provides a report including updated information on changing societal conditions at the time it tables its departmental performance reports. In 2001, for the first time, this report pro- vides comparisons of Canada’s performance with those of other countries.3 It also identifies some of the programs that have an influence on each area of perform- ance documented.

Committee scrutiny of budgetary performance can take place through:

a) review of the annual Public Accounts of Canada and Auditor General’s reports (typically by the Public Accounts Committee);

b) review of departmental estimates and plans, as well as supplementary estimates;

c) review of departmental performance reports; and

d) in-depth study of policy and programs.

As noted earlier, the Public Accounts Committee is active and generally seen as effective in its scrutiny role. The work of both the Committee and the Auditor General of Canada, while attracting some criticism from time to time, seem to be very useful and so regarded.

Committee review of estimates as part of the business of supply, as noted earlier, is not effective and does not at present contribute in any reasonable way to scrutiny.

The introduction of departmental performance reporting each fall provides an opportunity for committees to scrutinize the effectiveness of departmental programs. This was one of the reasons for introducing these reports in the late 90s. Only one departmental performance report — that of the Office of the Auditor General — was so reviewed and assessed in 2001. This was done by the Public Accounts Committee. Based on this review, that committee specified the kind of information on performance that it felt would help both the Auditor General and Parliament to better judge the Office’s effectiveness. In the past, a few committees have undertaken similar if less in-depth analyses. But on the whole such scrutiny occurs only rarely.

The final approach for committee scrutiny is an in-depth study. Of the 19 in-depth studies noted earlier, about half addressed program performance issues. For example, the study of marine infrastructure (Small Craft Harbours) by the Standing Committee of Fisheries and Oceans reviewed the implementa- tion of existing government commitments. The Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs reviewed the readiness of Canadian Forces in the new security environment. It looked at both the effectiveness under earlier conditions and the impact of the societal changes related to the World Trade Center incident.

Committees can and do contribute to scrutiny through their studies; at issue is the degree and effectiveness of undertaking scrutiny this way. Coverage is easier to assess. Of the 14 committees that have a mandate to review specific departments and programs, only five tabled reports in 2001 that reviewed current program per- formance in a substantial way. And of these five committees, only for three could the work on scrutiny be described as a substantial focus of committee effort.

The quality of the studies — for the purposes of scrutiny — is more diffi- cult to describe. Most studies are based on the hearing of both government and external witnesses, most describe departmental activities and most lead to rec- ommendations to change or augment activities already carried out. However, few studies comment on the effectiveness of existing programs, although they do suggest additions. When additional activities are advocated they do not identify the less valued activities that in their opinion ought to be replaced or reduced if additional resources are not available. In this sense, committee studies are weak in challenging the effectiveness of current programs. Moreover, there is little doc- umentation in reports to indicate that departmental explanations of effectiveness — their performance reports — have been considered, nor have committees identified the kind of information that they would need to make judgements on priority and effectiveness.

Although scrutiny attracts considerable parliamentary attention and activ- ity, it clearly has some important gaps.

Macro-fiscal performance: This is an area where, likely because of its impor- tance and the media attention it attracts, parliamentary attention is quite vigor- ous and where differing party positions are most clear.

Managerial/financial performance: This area also receives substantial atten- tion, likely because of the availability of reports from a well-resourced and respected scrutiny agent (the Office of the Auditor General) and because it is a source of embarrassing stories of possible mismanagement. This is an area where partisan differences are least apparent.

Programming performance: This is where the complex questions of both the effectiveness of current programming and its relevance to evolving societal con- ditions are addressed. Such matters can only be dealt with effectively through studies by committees. While a few committees devote considerable effort to scrutinizing effectiveness and program priority, the result for Parliament as a whole can only be described as weak. There clearly is quite limited attention within committees to developing an understanding of how programs are expect- ed to achieve results and their performance in doing so.

While set within a context, the indicators used in this report have emerged from discussions with Members of Parliament and knowledgeable observers. In other words, the way people think and talk about performance played the dominant role in the selection of the indicators. This is not the only way to proceed. There is a considerable literature on indicators of democratic and governance perform- ance. Employing the concept of “an ecology of governance,” the Parliamentary Centre has developed an analysis that explores relations among institutions and that identifies three broad indicators of parliamentary performance: accountabil- ity, transparency and participation.4

Only one of the 11 indicators used in this study does not fit easily within that structure — linking committee studies. While dropping this indicator would not change the overall findings appreciably, horizontal connections between com- mittees are important. The well-being of citizens is not segmented as departments and ministries are organized. Committees, accordingly, need to adopt a broad per- spective to carry out scrutiny with citizens in mind. Many Members have identified the absence of horizontal connections as an impediment to their work. For exam- ple, this view is a central theme of Common Vision (4th report, 37th Parliament of the Standing Committee on Human Resources and Persons with Disabilities).

The 11 indicators of this report focus much more on accountability and transparency than they do on participation. Perhaps this is due to the focus of this paper on the budget process. Other aspects of governance, such as the sys- tem for selecting Members — the electoral system — would focus more directly on participation. Nonetheless, it does illustrate that the selection of indicators is far from an exact science. While broadly accepted indicators and reliable infor- mation are important, experience shows that it is also useful to publicly expose early analyses and judgments, to expand the discussion to include others, and to make improvements as indicated by experience. That is the spirit in which these indicators and evidence are proposed.

The following table seeks to provide an overall impression of performance. To do so, numbers are assigned to reflect the foregoing analysis. The numbers, it must be emphasized, have no meaning beyond providing a simple-to-read com- parison among the indicators; there are no passing or failing grades. Two further aspects should be noted. First, the numbers from 1 to 5 (5 being the best per- formance) were assigned in reference only to each other. The numbers, accord- ingly, average out to approximately 3.0. Second, not all the indicators are likely to be of equal importance. Thus, adding the numbers makes no sense.

Yet, there do seem to be patterns. The empowering role, although well- documented in the Standing Orders, seems the least effective in practice. Scrutiny appears to be the strongest role except in the important areas of priori- ty and effectiveness. Representation shows neither particular strengths nor weak- nesses, but a number of Members felt that Parliament’s engagement of citizens — both by individual Members and by committees — is extremely important and needs to be strengthened.

The indicators and evidence cited do suggest that democratic control, in partic- ular as effected through the roles played by Parliament, is not something to be taken for granted. While it is likely that all areas can be improved, the analysis and observations of Members highlight three areas as most in need of attention: the parliamentary financial control framework for programs and supply, com- mittee studies to serve more effectively Parliament’s scrutiny and representation roles, and more effective engagement of citizens.

The key issue regarding the financial control framework is that Members are not engaged in the process of empowering the government through the sup- ply process. This is due, in large part, to the virtual impossibility of understand- ing the supply process and the substance of the authority provided in this process. If Parliament is to play a role, Members must have a more understand- able financial control framework for supply so they know what they are voting for or against. The government has expressed interest in working with Parliament on the framework. But, this is more than a technical matter — it must also engage Members.

Committees undertake studies for reasons other than to advise on budget- ary matters or to scrutinize program effectiveness and need. Yet in both these areas, committee studies are not only important, they seem to be the only rea- sonable way Parliament can fulfill these roles effectively. Accordingly, the man- agement, mandating and resourcing, and monitoring of committee performance in conducting studies are matters that need to be examined. Some Members on committees indicate that they are seeking quite actively to improve studies with these objectives in mind.

While good committees are essential to an effective Parliament, their func- tioning as an institution of Parliament receives little analysis. The learning by Members that occurs is more through osmosis than a deliberate attempt to improve performance. In the UK, for example, each Select Committee prepares a report on its performance. The Liaison Committee then synthesizes the find- ings and prepares a report recommending certain general improvements. While not all the recommendations are likely to be accepted, it has provided an oppor- tunity for each committee to think about its performance and how to improve it. A number of Members with whom this idea was discussed felt that this is some- thing our committees should investigate.

This suggests a more structured approach to committee management. Issues to consider include the approach to developing a committee’s agenda, the balance of resources between committee and staff, the allocation of staff as between chairs and individual Members, the balance between hearing time and deliberation time, the efficiency of different approaches to hearings and the value of committee travel. Although these points extend beyond the scope of this study, in the course of its preparation all these matters were discussed with Members as possible ways to strengthen committee performance.

The findings do not point as clearly to the need for this third action, yet the importance of engagement between Members and citizens was raised fre- quently and with some intensity. The credibility of committee studies frequently depends on how well and how visibly studies reflect citizens’ views. Moreover, in view of the potential provided by new information and communication tech- nologies, citizens’ expectations regarding consultation with their Members are growing here and abroad.

Members have a unique role to play in connecting government to citizens, a role some feel is being eroded and others feel needs to be strengthened. From the perspective of democratic governance, anything that strengthens the connec- tion is likely not only to improve deliberation of the public interest, but also strengthen the role of Parliament in empowering the government and holding it accountable.

The foregoing suggestions for change are, in a sense, incidental to a more fundamental matter, namely developing a better means of understanding and strengthening parliamentary effectiveness. In a world where change is seen as neither inevitable nor impossible, conscious step-by-step improvement based on examination of actual performance is a good way to proceed. This paper pro- poses some indicators of performance, provides some evidence and judgments of participants and observers on actual performance, and offers the findings as a package for thought and debate. While there is much in Parliament that does not work well, there is much that does, and what does not often seems improvable. The paper suggests a more structured approach to learning about the effective- ness of this most important of all Canadian institutions.

Chairpersons of Parliamentary Budget Committees of OECD Member Countries. Holding the Executive Accountable: Changing Role of Parliament in the Budget Process. Paris: OECD, 2001.

Miller, Robert. “Parliaments that Work: A Conceptual Framework.” Ottawa: Parliamentary (October 2001).

President of the Treasury Board. Canada’s Performance, 2001. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2002.

For Immediate Distribution – Tuesday, May 14, 2002

Montreal – In a new Policy Matters paper released today by the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP), Peter Dobell and Martin Ulrich analyse how Parliament carries out three roles in the annual budget process – representing citizen interests, empowering the government and scrutinizing the government’s performance.

In this paper, entitled “Parliament’s Performance in the Budget Process: A Case Study,” the authors organize their findings with the aid of performance indicators, seeking to shed light on the role of Parliament in preparing budgets. These ratings provide an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of Parliament’s engagement in the budget process.

The findings point to three important areas needing attention:

This study also suggests that parliamentary committees take a critical look at their tasks and objectives to ensure that Parliament and Canadians are getting the greatest value for the substantial time and resources invested. Periodic committee performance reports would be one way to begin.

“Parliament’s Performance in the Budget Process: A Case Study,” is now available in Adobe (.pdf) format on the IRPP website at https://www.irpp.org – to access the document, simply click on the “What’s New” icon on the homepage.

Peter Dobell is the Founding Director of the Parliamentary Centre. He has worked with Members of Parliament and parliamentary committees since the Centre’s founding in 1968. Martin Ulrich is a Senior Associate at the Parliamentary Centre. He joined the Centre in 2001, after 30 years in the federal public service, where he led Treasury Board initiatives to improve performance measurement and reporting to Parliament.

– 30 –

For more information, or to schedule an interview with the authors, please contact the IRPP. To receive IRPP media advisories and news releases via e-mail, please subscribe to the IRPP e-distribution service by visiting the newsroom on the IRPP website.

Founded in 1972, the IRPP is an independent, national, nonprofit organization whose mission is to improve public policy in Canada by generating research, providing insight and sparking debate that will contribute to the public policy decision-making process and strengthen the quality of the public policy decisions made by Canadian governments, citizens, institutions and organizations.