Although the word “strategy” originated in a military context, it is now general- ly used concerning the current state of an individual, institution or organization, where it wants to be in the future, and the means and resources it plans to use in getting there. The foundations of strategic planning are always based on broader vision or mission statements that reflect the core values and interests of the organization.

This paper addresses the lack of any framework for articulating Canada’s national security strategy and its subsequent linkage to defence policy. It begins by clarifying key definitions and terms of reference whose understanding is fun- damental for strategic defence planning. A discussion follows which explores the critical linkages between a broader definition of national security and Canada’s core values and national interests, which can be drawn from various policy docu- ments such as the Department of National Defence document Shaping the Future of Canadian Defence: A Strategy for 2020, and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade 1995 White Paper Canada in the World. A further con- nection is then made between these core values and interests and the tools and instruments to preserve them, which include defence policy and military power.

For comparative purposes, the national security strategic planning frame- works of both the United States and the United Kingdom are described to high- light the analytical rigour and the consistent and coherent mechanisms that support long-term strategic thinking in those countries. Recommendations are then outlined which address the need for a more methodical and coordinated inter-departmental approach to developing a national security strategy for Canada, one that remains integrally linked to wider foreign policy objectives and core values – the national interests – that we, as Canadians, profess so proudly to represent.

The September 11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre in New York sent a security chill across the world. It was viewed as a terrorist attack not just on New York but also on the core values and interests of the American people. It was an attack against a NATO partner. It was something that could easily repeat itself elsewhere.

Since that day, world leaders have been forced to review their own national security at the highest strategic level, and citizens are asking searching questions about security policy. As Air Chief Marshal Sir John Slessor reminded us in 1953,

It is customary in the democratic countries to deplore expenditures on arma- ments as conflicting with the requirements of social services. There is a ten- dency to forget that the most important social service a government can do for its people is to keep them alive and free.1

Many people and nations suddenly came to realize that without national security, nothing else matters, a mantra-like statement the media has echoed across the world.

For Canada, quick to support and join the coalition response, public debate has arisen concerning the relevance and adequacy of our national response and the capability and readiness of the Canadian Armed Forces. Questions include:

A key strategic policy issue is Canada’s perceived capability to “fight against the best alongside the best,” not only in terms of equipment, but also in terms of availability, deployability and sustainability of our forces outside of Canada — issues of interoperability with our allies. The events leading to the tragic loss of four Canadian soldiers in a training accident have served to rein- force these questions.

Since 1945, when Canada and her allies celebrated the end of the Second World War, Canada’s national security and defence identity has undergone numerous transformations while experiencing varying degrees of public and political support. Since the 1989 end of the Cold War, many in Canada have failed to see the defence portfolio as significant to Canada’s overall security con- cerns and have underestimated the strong links and interdependencies it has with the country’s democratic value system and its economic well-being. The shock of September 11, however, has caused some reaction and raised questions regarding Canada’s defence and security posture. It is now widely acknowledged, both inside and outside of government in Canada, that there is no national secu- rity framework or clear and distinct national security policy as such.

The lack of a national security framework or “policy” reflects a general lack of strategic vision and meaningful strategic objectives — and the associated resources — required to implement such a vision across the whole of govern- ment in general, but related to both the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade and the Department of National Defence in particular. This has been highlighted in the most recent report from the Canadian Senate2 and confirms similar and long-standing observations by others, including Byers (1986), Dewitt and Leyton Brown (1995), Bland (1987), Boulden (2000) and Delvoie (2001).

This paper will therefore examine the national security strategy and policy framework needs of Canada, starting with clarifying definitions of common termi- nology. This will be followed by a discussion of the way in which Canada defines its national interests and core values, which should serve as the foundation for a Canadian national security strategy. It will then examine how these strategic inter- ests shape defence policy and military power, which, together, represent one of the main instruments for implementing a national strategy. Lastly, this paper will dis- cuss the approaches to formulating national strategy and the linkages between defence policy and national strategy within the British and American governments. Conclusions will propose a national security policy process framework that will not only reflect Canada’s interests but also be comparable in terminology and scope with traditional coalition partners, the US and UK.

The term national security is used frequently to refer to matters ranging from domestic or internal security through to international security, but is seldom defined. Such imprecision can lead to difficulties, unless a Humpty-Dumpty-like3 flexibility in meaning is intentional, and therefore intentionally confusing. Clarity in the meaning and understanding the scope of national security are essential at the outset.

Canada’s National Defence College in 1980 adopted the following defini- tion to form the foundation of its curriculum.

National Security is the preservation of a way of life acceptable to the Canadian people and compatible with the needs and legitimate aspirations of others. It includes freedom from military attack or coercion, freedom from internal sub- version, and freedom from the erosion of the political, economic, and social val- ues which are essential to the quality of life in Canada.4

For the United States,

National security is a collective term encompassing both national defence and foreign relations of the United States. Specifically, the condition provided by: a) military or defence advantage over any foreign nation or group of nations; b) favourable foreign relations position; or c) defence posture capable of successfully resisting hostile or destructive action from within or without, overt or covert.5

For Canadian policy planners, in keeping with both definitions, it should be understood and be equally clear that the concept goes beyond internal secu- rity or military issues, and takes into account the whole range of government activities. National security, then, as pointed out by Slessor, truly is the first and most important social service for a government to deliver to its people.

Throughout security discussions there are other words and terms used which, to many both inside and outside the discussion, have different meanings in different contexts. How a national security policy may be developed and implemented leads directly to the notion of a national or grand strategy.

Strategy itself is a word that carries many meanings and interpretations and is used regularly in private and public sector and non-profit organization- al activity. Although there is a common misperception that strategy is primari- ly concerned with military matters, it really reflects goals or objectives, an understanding of the environment, including resources available, and the means by which the resources will be organized or applied to achieve the objectives. Thus, strategy can mean different things depending on the context and the level at which it is being considered. For example, at the lowest level it is possible for an individual to have a personal strategy, perhaps relating to his or her career aspirations. At the highest level, a government may have a strategy (or set of strategies) in order to meet its obligations to the country, across critical policy areas.

Over 60 years ago, Edward Meade Earle said,

Strategy is not merely a conception of wartime, it is an inherent element of statecraft at all times. In the present-day world, Strategy is the art of controlling and utilizing the resources of a nation — or a coalition of nations — including its armed forces, to the end that its vital interests should be effectively supported and secured against enemies, actual, potential or merely presumed. The high- est form of strategy — sometimes called grand strategy — is that which so inte- grates the policies and armaments of a nation that resort to war is either ren- dered unnecessary or is undertaken with the maximum chance of victory.6

In his recent article entitled Grand Strategy in the 20th Century, Sir Michael Howard states that grand strategy refers to the state of a country in wartime and peace, and involves warfighting and war avoidance (or deterrence).7 He acknowl- edges that most states maintain their independence, extend their influence and, at times, extend their dominion using national tools like armed force, wealth, allies and public opinion. In other words, certain strategic tools and techniques exist for a nation-state to use to protect its core values and national interests, which, for most countries, would include their political integrity and territorial sovereignty.

In the United States, the Department of Defence currently defines nation- al strategy or grand strategy as “the art and science of developing and using the diplomatic, economic and informational powers of a nation, together with its armed forces, during peace and war to secure national objectives.”8

Two other definitions of grand strategy draw on the work of Liddell Hart and Bernard Brodie, the first of whom explains that it involves the coordination and direction of all the resources of a nation, or a band of nations, toward the attainment of political objectives sought.9 Bernard Brodie, who sought a more rigorous approach to strategy and a systematic form of analysis rather than a nar- row superficial approach to security problems adopted by the military, referred to grand strategy as “an instrumental science for solving practical problems.”10

Edward N. Luttwak, in his 1987 book, Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace, describes grand strategy as something that is used to explain the totality of what happens between states and other participants in international politics, the con- clusive level of strategy as a whole.11 Thus, grand strategy is the pinnacle of the strategic edifice which offers the most general explanation of conflict.

For some states, military power is the leading instrument for pursuing grand strategic objectives. But it also presumes that the nation-state is a cohesive unit, which is why a national strategy seeks to protect the values and interests which ensure that cohesion. Professor Lawrence Freedman goes beyond the mil- itary context, stating recently that grand strategy is concerned with how far and for what purposes states concern themselves with the international system. He suggests that the new challenge is protecting a state’s international position not vis-à-vis other more radical states, but vis-à-vis the more fundamental shifts in the system that contest the whole idea of a state.12

Governments are not carried forward by the tide of technology and the remorseless logic of markets but have real and difficult choices to make about how they look after their people and act beyond their borders. That is, they need a strategy.

These discussions are reflected in the concise US definition of a National Security Strategy: “the art and science of developing, applying and coordinating the instruments of national power (diplomatic, economic, military and informa- tional) to achieve objectives that contribute to national security.”13

National security strategy — grand strategy — therefore, is something far- reaching, all-encompassing, visionary and long-term, yet dynamic in nature. So, the art of strategic planning should first define particular objectives, based on the national values, to be pursued as the foundation of a national or grand strategy. At a private-sector corporate level, this involves the board of directors and the operating executives. At the nation-state level, this should involve the major gov- ernment portfolios and the whole Cabinet.

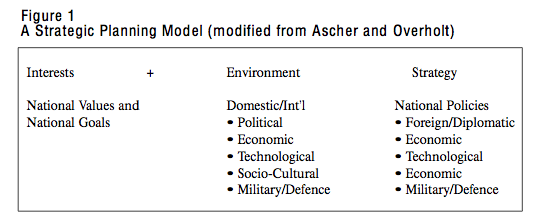

Commonly, strategic planning models and processes begin with the articulation of national or corporate values and goals, which collectively represent the fun- damental interests to be pursued and preserved. The expected operating envi- ronment — events, issues and trends — are then projected into the future and their potential impact on the fundamental interests assessed. A strategy is then developed using the available resources (human, technical, financial) to promote national or corporate interests and achieve national or corporate goals in the per- ceived future environment.

A modification of the Ascher-Overholt Strategic Planning Model14 for a nation might then be useful to clarify and simplify the concept and process.

The first step, identification of national interests, brings us to another mat- ter, the concept of “the national interest” itself. The concept of national interest is sometimes criticized as being potentially too subjective or too specific. But a particular problem, like other terminology discussed above, is the misunder- standing and misuse of the words. Plischke, following an exhaustive review of the concept, states,

Much of the difficulty of comprehension and objection to its application in the conduct flows from its careless and equivocal use by political leaders and the biased and parochial interpretations of some of its analysts. But, these are scarcely valid reasons for justifying the invalidation of a concept as prevailing and important as national interests in managing and understanding the foreign policy process.15

Joseph Nye also has noted that “In a democracy, the national interest is what a majority, after discussion and debate, decides are its legitimate long-run shared interests in relation to the outside world.”16

A clear and unequivocal statement of national interests, however difficult to develop, can be a valuable tool in policy development and to assess reaction to domestic and international events. In addition, it can be used to encourage public discussion and involvement in how national interests may be protected or pursued. National interests are inextricably linked to national security and a national security policy.

In the US, national security interests are “the foundation for the develop- ment of valid national objectives that define US goals or purposes. National secu- rity interests include preserving US political identity, framework and institutions; fostering economic well-being; and bolstering international order supporting the vital interests of the United States and its allies.”17

In Canada, there is no clear definition or overt statement of national inter- ests as such, although the expression of something being or not being “in the national interest” is commonly used by politicians and commentators. However, a construct of Canada’s national interests can be achieved by examining state- ments of foreign and defence policy goals, which incorporate statements of fun- damental values. Such a construct could not only provide clarity of purpose, but also foster informed public discussion, as well as being an element of accounta- bility for public policy makers.

In the 1995 foreign policy White Paper, Canada in the World,18 Canadian values are clearly stated to be:

The foreign policy goals in that document, which may be seen to reflect nation- al objectives, even if not overtly stated, are:

The Department of National Defence document Shaping the Future of Canadian Defence: A Strategy for 202019 states: “The Canadian values to be defended include”:

In Canada, the development of foreign and defence policy is a somewhat ad hoc process, lacking in detailed analysis from first principles, but driven more by certain concepts enunciated by deputy minister-level officials in the Department of Foreign Affairs, the Privy Council Office or indeed the Prime Minister’s Office. This process, as it concerns the Canada in the World document and many of its predecessors, is frankly discussed in David Malone’s recent arti- cle, Foreign Policy Reviews Reconsidered. Notwithstanding expectations to the con- trary, Canada’s foreign policy reviews have been essentially more of the same thing, but reflecting the personal interests of politicians and officials rather than fundamental analysis. Even so, Malone claims that Canada in the World still pro- duced “a fluent, sophisticated, acute analysis of the world in 1995, with fairly insightful projection into the mid-term future.”20

Notwithstanding this criticism, the combination of Canada in the World and Shaping the Future of Canadian Defence provides a foundation for at least some gov- ernment perception of Canada’s national interests based in economic well-being, security, and protection and projection of Canadian values: democracy (including the rule of law), individual freedom and human rights, and social justice. However, there is no consistent national security policy-planning framework within the Privy Council Office, the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade or the Department of National Defence. Officers and officials in the departments and agencies involved admit there is no such framework and support the need for some coherent and consistent process that could be used to integrate various depart- mental interests. Some also indicated that there are opposing opinions on the need for such a framework, as “resisters” wish to avoid being constrained by a particu- lar process or even an overt statement of interests.

This reinforces the assessment of Jane Boulden who in her study, A National Security Council for Canada, stated, “there is a national security policy gap that needs to be addressed in Canada.” The gap in question is a functional one related to the national security policy-making process and “the machinery of government.” The process has continued to be ad hoc, based in Cabinet deci- sions made on advice received from ministers’ individual departments, which may indeed be in conflict. The Auditor General observed the decision-making process for peacekeeping deployments in 1996. As Boulden reported, “The Auditor General found that a clear statement of Canadian objectives was not always provided” and the implications for Canada or for other government departments were given “insufficient” analysis.

The absence of a formal process, then, contributes to limited or poor analysis and less than coherent and consistent policy development or decision- making.

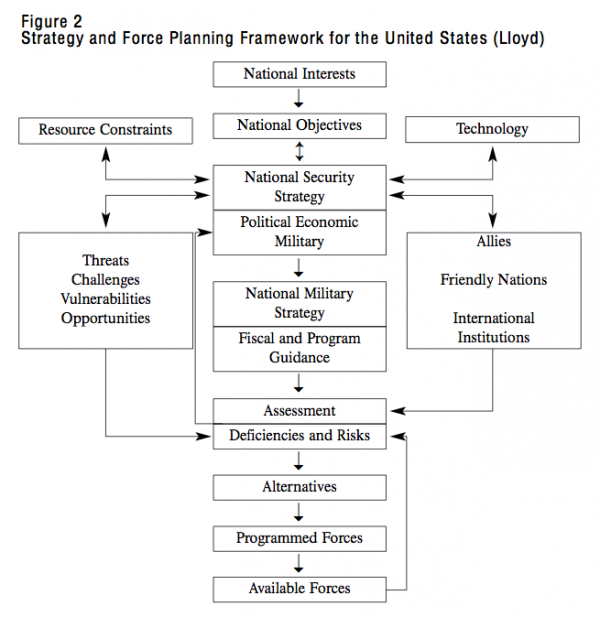

The development of process models or frameworks can be useful tools in explaining the sequence and content required in a dynamic system, as well as the impact that changes may have on other elements of the system. Richmond Lloyd has developed one framework to describe the strategy and force planning process in the United States (figure 2). Recognizing that there can be many activities and elements involved in any one of the components, a detailed description of the components and inherent activities is included in his text and will not be repeat- ed here.21 However, it is clear from the model that the starting place is the state- ment of national interests and national objectives leading to a national security strategy, encompassing political, economic and military components and the external environments including resource, technology and international analy- ses. These feed into the national military strategy which — following resource, risk and deficiencies assessment — lead ultimately to the force posture.

In the United States, such a framework is additionally useful because of the formal statements made periodically by each administration, as well as a glossary of terms and definitions, some of which have been used above. For example, in the Clinton administration document entitled “US National Security Strategy for the New Century,” the United States’ national objectives are clearly stated to be:

It is interesting to note the similarity with the foreign policy goals of Canada in “Canada and the World.”

The same document details the statement of the United States’ national interests by category:

More recently, the Quadrennial Defense Review, “America’s Security in the 21st Century,” articulated US interests and objectives as:

Ensuring US security and freedom of action, including:

Honoring international commitments, including:

Contributing to economic well-being, including:

These statements all provide the starting point for the top down analysis and policy development process and reflect the basis upon which national secu- rity — in its widest context — and military strategy planning is undertaken.

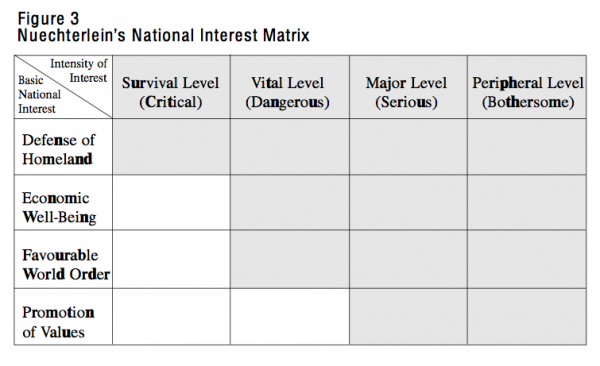

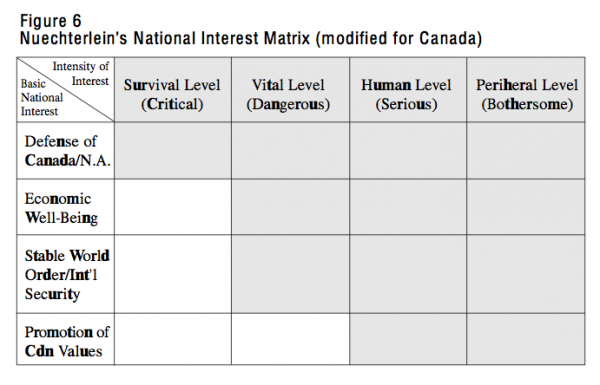

Given such statements of goals and interests, another very useful tool, termed the “National Interests Matrix,” was developed by Donald Nuechterlein, in its original form in 1976 but most recently published in his 2001 book, America Recommitted — A Superpower Assesses Its Role in a Turbulent World.24 This matrix (figure 3) starts with listing the basic national interests in the left-hand column and, across the top, the levels of interest: survival, vital, important, peripheral. A given world situation can be quickly assessed in “interest terms” by asking the question, “Which countries interests are affected by this situation and at what level?” Considering that survival or vital interests usually call for a mili- tary commitment, this matrix tool can quickly indicate the countries which are likely to respond, and using which means. Equally, it serves to clarify which United States’ interests may also be affected.

As useful as the policy framework or national interest matrix may be, they still require a fundamental first policy step: a clear articulation of national goals and values, i.e., the national interests.

It should be remembered that the “national interest” approach to policy planning originated with British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston in 1848, when he stated, “We have no eternal allies and no perpetual allies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual and those interests it is our duty to follow.

The United Kingdom’s approach to linking a national strategy with defence planning has evolved considerably since Palmerston and even the application of Winston Churchill’s model during the early 1940s. Today, Prime Minister Blair’s inner office continues to lead proactively on defence and foreign affairs issues, sim- ilar to the Thatcher government. So, although national interests should be arrived at by consensus in the Cabinet and Office of the Prime Minister, Mr. Blair has slimmed down the Cabinet and personally has a great sense of national interests. This has become known as the “presidentialization” of the British system of gov- ernment: the contention is that the British prime minister increasingly resembles the president of the United States in his or her ability to take policy decisions and drive the government machinery, free, or relatively free, from the constraints of col- lective ministerial responsibility and other constitutional conventions.25

There is also a recognition that the Ministry of Defence (MoD) is a leading authority on national strategy and longer-term thinking, underlined by the way in which the department handles equipment procurement and recruitment policies. Despite the fact that the Cabinet is served by the Defence and Overseas Secretariat, the work of which feeds into the Defence and Overseas Policy Committee, there is a tendency for the current government to bypass the Cabinet committees and take advice directly from the Director of Policy within the MoD. Thus, the MoD is more political than it has ever been and it is perceived to be more of a medium- term thinker than the Foreign Office, which is more pragmatic and short-term in its view. The Foreign Office has also been described as an office that has become overburdened with the development and application of management techniques, which has resulted in time lost for policy thinking, policy planning, and for the formulation and orderly pursuit of policy objectives.26

Whereas a defence policy flows from a country’s foreign policy, a country’s foreign policy should be based on national interests and values that serve as national policy at the grand strategic level. Although the term “national interests” can at times be deceptive and unclear, in a democracy, voters have a right to a foreign policy that promotes their immediate interests. However, the raft of real issues that confront governments and voters on a daily basis can dilute this as they create conflicting priorities and, therefore, make difficult a consolidated view of what national interests may be perceived to be.

Similar to the way successful multinational corporations define their mis- sion statement in fairly general terms (for example, Sony’s commitment to pro- vide “personal and portable sound to every household”), national interests do not need to be narrowly defined. From a British perspective, London School of Economics’ Professor Mary Kaldor stresses,

National interests include national security as well as jobs, environmental sus- tainability, as well as trade, the fulfillment of properly chosen humanitarian goals, as well as business interests of British firms.27

The next step in the British approach to grand strategic policy formulation is to define the assets that are available to pursue the national interest as defined. In this context, nation-states have four general categories of “tools” or “instru- ments” at their disposal: those that come under the control of the government, such as political skills, diplomacy, a country’s armed forces, and resources that come under the control of other government departments; those that depend on the government but which operate outside its control, such as the national media and state councils; institutions and organizations such as think-tanks, academic institutions and non-governmental organizations; and a country’s foreign invest- ments and assets.

The last step is to create a vision that describes objectives and activities in a meaningful way, not only to policy practitioners but also to the public and for- eign audiences. Unless a country’s voters believe that public expenditure is devoted to causes that relate to their interests, they cannot be expected to pro- vide support. As John Coles has observed,

National interests should not be suppressed in order to construct an artificial consensus or a bogus unity. Influence was a means and not an end in itself. Occasionally, it might be appropriate to accept a loss of influence if that was the only way to protect our interests.28

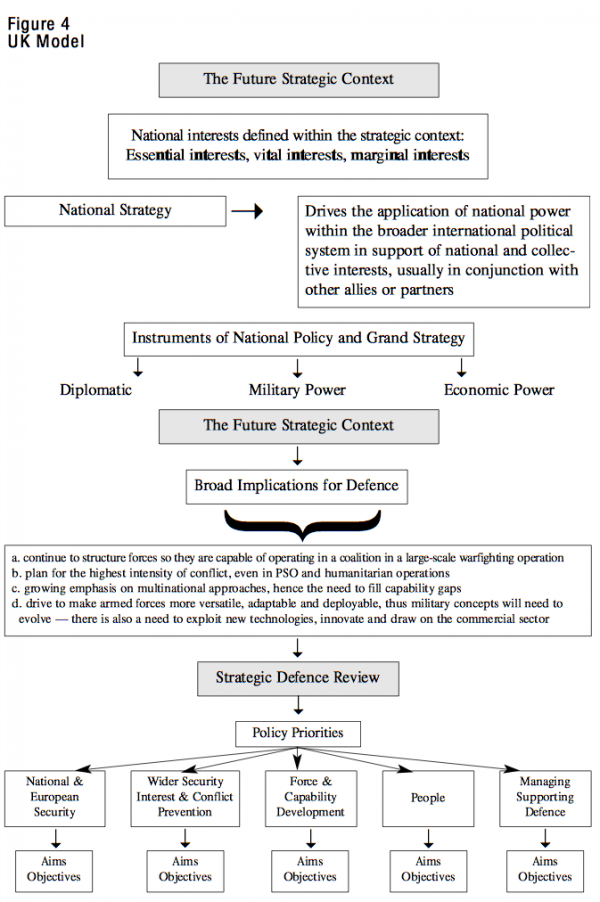

For the United Kingdom’s MoD, the implementation strategy for the process described above unfolds in a reasonably systematic way, bearing in mind the approach of the current government. An obvious and integral element of the national strategic planning equation is the Treasury which, every two or three years, calls for spending reviews, something which triggers the MoD to produce a Strategic Defence Review (SDR). The last SDR was conducted in 1998 and was sufficiently strategic in vision to still hold contemporary relevance since the events of September 11. The strategic analysis process involves defining the future strate- gic context and invites the participation of the other Cabinet members (usually led by the Secretary for Defence). If disagreement exists in terms of how this strategic context is defined, the work then goes to the relevant Cabinet committees. However, since the arrival of the Blair government and its commitment to “joined- up” government deliberations, this contingency has not been used.

The main framework of the strategic environment includes the analysis of political, economic, military, physical, scientific and technical, social and cultural, and legal, ethical and moral issues, discussing each in turn and then drawing them altogether in an overall description of the world as seen from a British perspective.29

Once an exhaustive analysis has been completed, UK national interests are defined within the strategic environment and categorized into essential, vital and marginal interests. While these definitions are still perceived as a function of the state, the UK military’s strategic doctrine must be sufficiently flexible to cope with shifts in perceptions of national interests reflected in policy. From the analysis a national grand strategy is developed which drives the application of national power within the broader international political system in support of national and collective interests, usually in conjunction with other allies and partners.30

The senior planners then revisit the instruments of national grand strate- gy, which include diplomacy, economic power and military power. The future strategic context is then reviewed and broader implications for defence are drawn from the analysis. This may include statements such as “to continue to structure forces so they are capable of operating as a coalition in a large-scale warfighting operation” or “to recognize a growing emphasis on multinational approaches and filling capability gaps.” Policy priorities are then taken and grouped under their relevant headings such as National and European Security, Force Capability and Development, People, Wider Security Interest and Conflict Prevention, etc. Aims and objectives for each of these categories are then articulated and serve as the executive text of the SDR. While the SDR is only published every few years, the strategic analysis and planning processes are perpetual and dynamic.

In the mid-1990s, the structure of the most senior UK MoD departments was altered slightly, and the restructuring resulted in the creation of the Defence Management Board (DMB) that would sit directly under the Defence Council, the high- est national authority responsible for defence. The Policy Directorate is responsible for producing the Defence Strategic Plan (DSP) through the same analytical process described above. The short-term version of the DSP is the Corporate Plan, which has a shorter-term vision of four years and is produced by the Defence Performance and Analysis Department under “Finance.” The methodology which serves as the founda- tion for the Corporate Plan is the Balanced Scorecard (BSC), which targets the deliver- ables and underlines the agreement the Department has with the Treasury.

Thus, the approach to defence planning and formulating defence policy in the UK has a definite strategic orientation and, moreover, there is a direct link between strategic planning surrounding the national security of the UK and the grand strategy of the country, based on core values and national interests. These tight linkages have resulted in coherent policy, which the UK MoD has been able to communicate clearly to the British public. This strategic orientation of the MoD has gained it an influential overall advisory position in the highest offices of the Blair government. Its continuous commitment to strategic analysis and influence in the Cabinet has triggered current work on the development of new levers of power, to be used when military power is not the best way to penetrate the center of gravity of a threat to the UK’s national interests.31

Lastly, the UK’s dynamic approach to strategic analysis for defence deci- sion-making led the Secretary of State for Defence to request that the MoD embark on a “new chapter to the 1998 SDR.”32 This decision was precipitated by the fact that the threat of terrorism has potentially been raised, which has signif- icant strategic impact for the UK, and the MoD is also keen to know if it is deal- ing with something strategically different in light of the fact that the UK itself may now be strategically different. In a recent House of Commons debate, the Secretary of State for Defence stated:

The threat to the UK goes beyond the UK’s borders and thus has implications for the UK’s armed forces on deployment. The more they are used for overseas missions, for which changes under the SDR are designed to equip them, the more they risk presenting themselves as targets…Professor Lawrence Freedman has also said that, where conflicts in far-off places involve British troops, we cannot always assume that they will necessarily be fought out only where they arise.33

A framework model of the UK process is presented in figure 4.

It is clear from examining Canadian experience and both the US and UK process- es that Canada lacks any process even remotely comparable in analytical rigour, multi-department involvement, coherence and consistency. The absence of a clear process is possibly a major factor in the irregularity of foreign and defence policy reviews: the methodology is not clear and has to be reinvented each time, leading to the less than relevant results as reported by Malone. Further, as already observed by Boulden and the Auditor General, the absence of stated relevance of deployments of Canadian Forces to Canada’s interests — goals and values — indeed reflects inadequacies in the policy and decision-making process.

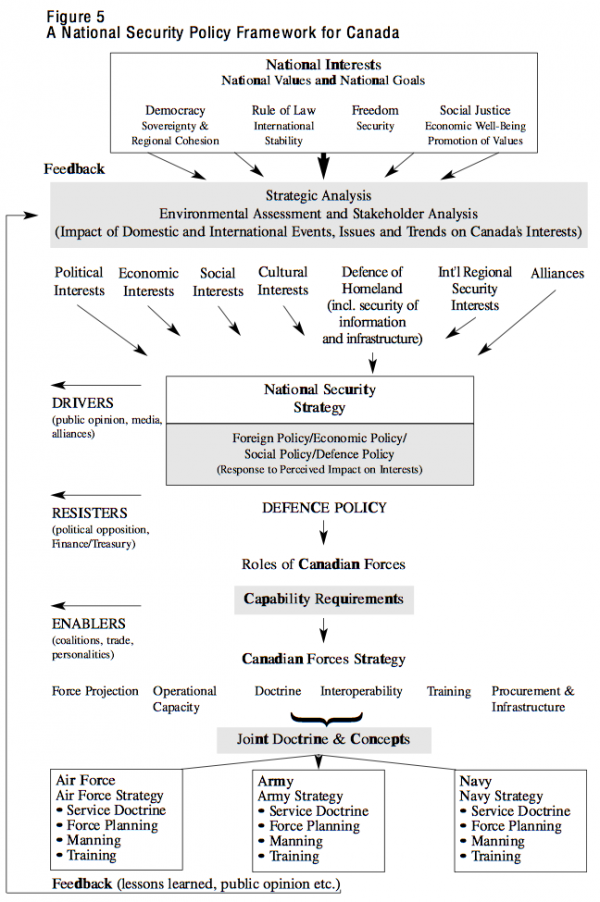

A national security policy framework for Canada has therefore been pro- posed, taking into account the processes in the US and UK, but recognizing certain special concerns for Canada. The first of these is the need for clear articulation of Canada’s national interests, based in a clear statement of fundamental values and national goals. The second is to highlight both domestic and international interests against which an environmental assessment will be undertaken to identify the events, issues and trends which may have an impact on Canada’s interests. Thirdly, a clear link between a national security strategy, national security policy and defence policy should emphasize that national security is about more than defence, but that defence is importantly integrated into national security, hence the important involvement of the other government departments concerned with for- eign, economic and social policy. Finally, defence policy that articulates the roles and capability requirements consistent with the national security strategic situation ultimately leads to the location and role of individual service strategies in the over- all scheme to ensure a comprehensive approach to the issue. This framework is presented in figure 5.

The first step, the statement of national interests — values and goals — can be derived from existing policy and constitutional documents. The Canadian values used here (democracy, the rule of law, freedom and social justice) are the core values or intrinsic values of virtually any Western democracy, and the shared values which are so often referred to in political speeches and policy statements. These are not, however, the Canadian values often expressed in terms of social or “instrumental” values, as described by Maloney34 (“soft power,” tolerance, edu- cation, medicare and the like), which are, in reality, derivatives of the core val- ues. The core values should be clearly stated, as these are the values we expect our troops to defend and, if necessary, die for.

The national goals (sovereignty, regional cohesion, economic well-being, security, international stability and promotion of values) already articulated in both foreign policy and defence policy documents are consistent and appropriate.

The next step is a formal strategic analysis, an environmental assessment and stakeholder analysis, to identify domestic and international events, issues and trends that may affect Canadians and Canada’s interests. This step requires a detailed analysis conducted by a team of analysts schooled in the analytical tech- niques and knowledgeable in the areas of politics, economics, technology, and military and international affairs. This analysis — strategic intelligence — should identify the major risks and threats to Canada’s interests and, therefore, overall national security, in the broad sense defined at the beginning of this paper.

From the strategic analysis, a policy response is developed — a National Security Strategy. First, the impacts of domestic and global events on the various areas of concern to Canadian’s national security are detailed: political, economic, social, cultural, defence, international regional security, and our allies. This leads to the development of a set of major policies (foreign, economic, social and defence) and a national security strategy to react to those impacts and protect or promote Canadian interests. The coordination of the development and execution of the various policies is properly the role and responsibility of the Privy Council Office, which in the context of this national security framework and process will thereby be effectively a national security agency.

Defence policy, formulated in concert with the other security policy com- ponents, can then concentrate on the essentials as detailed in figure 5. The roles of the Canadian Forces are dictated by the policy that then leads to an analysis of the capability requirements to meet the perceived risks and threats identified in the strategic analysis. From this analysis a Canadian Forces strategy can be for- mulated — how to organize and deploy the Canadian Forces given the threat environment, capabilities required and resources made available by the govern- ment. This will lead to decisions in a number of areas concerning activities, for example: the need for force projection; operational capacity; operational doc- trine, including opportunities and needs for interoperability with allies; training; procurement; and infrastructure. Joint doctrine and concepts developed from this phase can then provide the foundation for the individual services to devel- op their own strategies, doctrine and planning.

On the left side of the chart are indicators of elements external to the process that can have an influence on the policy directions. “Drivers” such as public opinion, the media and alliance members will provide essential views of whether or not an open policy process includes public consultation. “Resisters” to certain policies may arise from political or bureaucratic opposition, such as the Department of Finance, the Treasury Board or even Foreign Affairs or National Defence. “Enablers” such as the trade environment, interest group coalitions or even public personalities may be less directly involved in the pol- icy development but can be important factors supporting the intended policy direction.

Finally, the proposed framework provides for feedback that can and should be formal and public to ensure that the policies in fact address the concerns iden- tified in the strategic analysis, or even identify changes in risks or threats.

An additional tool, a modification of the very useful Nuechterlein National Interest Matrix is offered (figure 6) to improve the utility of the matrix for Canadian conditions. This matrix can be used for analyses not only to clarify interests at risk in a given situation, but also to assess the level of response and to communicate more clearly with both the various relevant departments and the Canadian public.

Determining whether the proposed systemic process for national security policy development will lead to better sets of coordinated policies which may improve Canada’s governments’ domestic and international performance would perhaps attribute too much simply to process. On the other hand, with clear statements of national interests at the highest level and a coherent set of policies aimed at protecting or enhancing those interests, the Canadian public could become more directly involved in the discussions, and hence legitimize the assumptions in the foundations and the eventual policy outcomes, as befits an involved democratic society.

The need to have a systematic and consistent process for the formulation of Canada’s national security policy must be recognized to be in the interest of all of Canada — the government, principal policy departments and the Canadian public, but especially the Canadian Forces. To have a process that uses termi- nology and elements similar to allies and major coalition partners can permit the comparison of conclusions, needs and capabilities to the better benefit of sound decisions affecting Canada’s security interests in the broadest sense.

It is hoped that the proposed framework and the modified Nuechterlein matrix in their proposed (or some modified) form will find their way into the responsible departments and agencies. Canada may then have, for perhaps the first time, a set of policies that truly represent a comprehensive national security strategy, from which will flow a national security policy which will be understood and discussed by all Canadians, and to which appropriate public resources will be dedicated.

Ascher, William and William H. Overholt. Strategic Planning and Forecasting. Toronto: John Wiley and Sons, 1983.

Brodie, Bernard. “Strategy as Science.” World Politics 1 (July 1949): 177.

Clinton, William J. A National Security for the New Century. Washington, DC: The White House, 1999.

Coles, John. Making Foreign Policy. London: John Murray, 2000.

Department of Defence. Department of Defence Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. Joint Publication 1-02 (As amended to December 19, 2001).

Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. Canada in the World: Canadian Foreign Policy Review. Ottawa: Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1995.

Department of National Defence. Shaping the Future of Canadian Defence: A Strategy for 2020. Ottawa: Department of National Defence, June 1999.

Earle, Edward Meade. Makers of Modern Strategy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1943.

Freedman, Lawrence. “Grand Strategy in the 21st Century.” In Defence Studies 1(1) (Spring 2001): 11.

Hart, Liddell. “Strategy as Science,” World Politics 1 (July 1949): 486.

Hoon, Geoff (Secretary of State). Minutes of Evidence. House of Commons, Defence, Question #300, November 28, 2001.

House of Commons. “Threat of Terrorism.”

House of Commons Select Committee Report, #3481-3482, December 12, 2001.

Howard, Michael. “Grand Strategy in the 20th Century.” In Defence Studies (1)1 (Spring 2001): 2-3

Huntington, Samuel. The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1957.

Kaldor, Mary. “Foreign Policy in the 21st Century.” Speech to One World Action seminar, October 29, 1997, Report of the Seminar. London: One World Action, 1997.

Lloyd, Richmond M. “Strategy and Force Planning Framework.” Strategy and Force Planning, Third Edition. Newport, RI: Naval War College, 2000.

Luttwak, Edward N. Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Malone, David. “Foreign Policy Reviews Reconsidered.” International Journal 56 (Autumn 2001): 555-578.

Maloney, Sean M. “Canadian Values and National Security Policy: Who Decides?” Policy Options, 22(10) (December 2001): 45-49.

Nuechterlein, Donald. America Recommitted: A Superpower Assesses Its Role in a Turbulent World, 2nd ed. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001

Nye, Joseph. “Why the Gulf War Served the National Interest.” The Atlantic 267-268 (July 1991), 54-56.

Plischke, Elmer. Foreign Relations — Analysis of Its Anatomy. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Slessor, John (Air Chief Marshal Sir). Strategy for the West. New York: William Morrow, 1954.

The Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence. Canadian Security and Military Preparedness. Ottawa: Report of the Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence, 2002.

United Kingdom Ministry of Defence. British Defence Doctrine. MoD Joint Doctrine & Concepts Centre: RMCS Shrivenham, 2001.

United States, Department of Defense. America’s Security in the 21st Century. Quadrennial Defense Review Report. Washington, DC, 2001.

For Immediate Distribution – Wednesday, October 9, 2002

Montreal – After September 11, 2001, the need for Canada to formulate a national security strategy is in the interests of the government and the Canadian Forces, says new study. Canada has no distinct national security policy as our US and UK allies do and what policy we have is ad hoc, says a new study entitled A National Security Framework for Canada, released today by the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP).

“The shock of September 11 has caused some reaction and raised questions regarding Canada’s defence and security posture. It is now widely acknowledged both inside and outside the government of Canada that there is no national security framework or clear and distinct national security policy as such,” say authors W.D. Macnamara and Ann M. Fitz-Gerald.

In fact, there is no process in place to begin formulating a policy. “It is clear from examining Canadian experience and both the US and the UK processes that Canada lacks any process even remotely comparable in analytical rigour, multi-department involvement, coherence and consistency.”

Thus, after examining the processes used in the US and UK, the authors propose a National Security Policy Process Framework that reflects Canada’s interests, while being comparable to those of our traditional coalition partners. “The need to have a systematic and consistent process for the formulation of Canada’s national security policy must be recognized to be in the interest of all Canada — the government, principal policy departments and the Canadian public, but especially the Canadian Forces.”

W. D. Macnamara, a retired brigadier general, has been teaching international business and strategy in undergraduate, MBA and executive programs at the Queen’s School of Business. Ann M. Fitz-Gerald, a Canadian, is an associate professor at Cranfield University’s Department of Defence Management and Security Analysis at the UK Defence Academy, and Director of the Centre for Managing Security in Transitional Societies.

A National Security Framework for Canada is the latest Policy Matters paper to be published by the IRPP in its National Security and Military Interoperability series. It is now available in Adobe (pdf) format on the IRPP website, www.irpp.org

Other studies in this series include:

– 30 –

For more information, or to schedule an interview with an author, please contact the IRPP. To receive IRPP media advisories and news releases via e-mail, please subscribe to our e-distribution service by clicking on “Newsroom” on the IRPP website,

Founded in 1972, the IRPP is an independent, national, nonprofit organization whose mission is to improve public policy in Canada by generating research, providing insight and sparking debate that will contribute to the public policy decision-making process and strengthen the quality of the public policy decisions made by Canadian governments, citizens, institutions and organizations.