The practice of rotating parliamentary secretaries (PS’s) every two years that was initiated by Prime Minister Trudeau and taken up by Prime Minister Chrétien has profound consequences for the way the House of Commons functions. This study analyses how appointments have been made since the office was first estab- lished and assesses the consequences of the current practice.

Under the present practice, PS’s know that after two years in the post their appointment will not be renewed, no matter how well they perform. Consequently ministers have little incentive to assign them significant responsi- bility, except when a PS brings prior experience or expertise to the position. Some PS’s develop productive working relations with their ministers and the appointment does offer a few material perquisites – a salary supplement, a title, some staff support and occasionally overseas travel on departmental business. Not surprisingly, however, when PS’s are replaced by a colleague regardless of their performance in office, the natural reaction is disappointment.

The frequent rotation of PS’s is not an isolated phenomenon. It has reper- cussions for other elements of the parliamentary system, in particular parlia- mentary committees. Usually those removed from the position of parliamentary secretary press their party whip to find them another office. The chair of a com- mittee is the preferred prize and frequently several openings exist, since a num- ber of chairpersons have usually been appointed to the vacant PS positions. And so another round of musical chairs takes place. The net result is that a practice, introduced by Mr. Trudeau to share among members of the government caucus the material rewards and the responsibilities that come with the office of parlia- mentary secretary, has become an important constraint on the effectiveness of committees.

The practice of other prime ministers with respect to parliamentary secre- taries differed substantially. A detailed review of PS appointments by prime min- isters since Mackenzie King reveals that five – King, St. Laurent, Diefenbaker, Pearson and Mulroney – frequently reappointed effective PS’s to the office for several years and treated them as additions to the executive. Moreover, some who proved their worth in the PS position were later promoted to cabinet.

A decision by government to revert to the practice of reappointing com- petent PS’s for multiple terms would bring several benefits. Incumbents would have the time to gain skills and expertise that would equip them to carry more responsibility in that office. Stability in the PS position would also remove a prin- cipal cause for the regular replacement of committee chairpersons. If chairper- sons – along with other committee members – remained in place for longer periods, committees could become more effective and play a more important role in the parliamentary process. This would provide a source of fulfilling activity for backbench members that could offset any frustration that might emerge from the reduced opportunity for a PS appointment. Together these steps would offer pri- vate members more predictable, satisfying and constructive career paths – and would make the House of Commons a more effective and productive institution.

The appointment of MPs to the office of parliamentary secretary (PS), a process that usually occurs each autumn, attracts little attention. This is unfortunate since the practice of wholesale rotation every two years that was initiated by Prime Minister Trudeau has profound consequences for the way the House of Commons functions and for the satisfaction that private members derive from the job of MP. This study analyses how appointments have been made since the office was first established and assesses the consequences of the current practice of regular rotation every two years.

When Prime Minister Chrétien announced in December 1993 the names of the first group of 23 MPs to be appointed to the office of parliamentary secretary, he described them as ministers in training and cautioned cabinet ministers to perform well lest they be outshone and replaced. The announcement did not come as a surprise since it reflected his own experience. Mr. Chrétien’s career took off when Prime Minister Pearson appointed him parliamentary secretary in the 26th Parliament (1963-65), reappointed him immediately following the 1965 election, and, after a total of 21 months as a parliamentary secretary, ele- vated him to the ministry.

But the Prime Minister’s words of caution proved to have no substance. Two years later, in February 1996, a wholesale rotation of parliamentary secre- taries was announced. The press release issued by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) reported that the “Prime Minister has adopted the practice of previous governments of completely rotating parliamentary secretaries.” The practice has been followed ever since by the Chrétien government. Parliamentary sec- retaries have been regularly replaced after two successive one-year terms in that office.

This practice of rotating PS’s has contrasted dramatically with the stability of the Chrétien cabinet. A defining characteristic of the three governments that he has headed has been the exceptional continuity of the ministry. Not only have few MPs been elevated from the backbenches to the cabinet, but during the eight years of Chrétien government, there have been relatively few shuffles within cab- inet, especially in senior portfolios.

A persuasive case can be made for leaving effective ministers in charge of important departments. Not only does this practice promote good government, because it permits a minister to set and pursue longer-term goals, it also offers successful incumbents a high level of job satisfaction.

Though the same arguments could apply to parliamentary secretaries, they have not been offered the same stability as cabinet ministers. Under the present practice, PS’s know that after two years in the post their appointment will not be renewed, no matter how well they perform. Reg Alcock, addressing a group of his colleagues at a meeting on Parliament Hill on May 10, 2000, spoke quite can- didly on the subject:

I want to focus on the turnover that takes place on the government side at all levels. I am currently a parliamentary secretary. I know the day I am appointed that my term will end in two years. As a result people in the department that are working with me have no real incentive to invest any time and energy in that relationship. And conversely, I know that I am going to leave … in a prescribed time. So there is an uneasiness in that relationship.1

As Alcock points out, the consequence of this practice is that a minister has little incentive to assign significant responsibility to a member who will be moved two years later, unless by chance the member already has solid grounding in the department’s business or has had previous experience as a PS. By the same token, unless the minister gives specific direction, senior pub- lic servants in the department are not inclined to reach out to their PS.

The position of PS does bring a few material perquisites: a salary supple- ment of $11,200, usually some staff support provided by the department and occasionally overseas travel on departmental business. PS’s are expected in turn to undertake some regular tasks: answer questions when their minister is absent from the House, usually on Fridays; provide supplementary information during the “late show” at the end of sitting days; and sit on the standing committee to which the department reports. Since in most instances “answers” are prepared for PS’s by officials, their short appointment to a ministry and consequent lack of specific knowledge does not present many risks for the government. In effect, a primary function of the system as it now works is to offer a title and a modest financial reward to some twenty-five additional government backbenchers every two years.

When the two years come to an end and they are replaced by a col- league, the natural reaction is disappointment, even a sense of rejection. That sentiment was well expressed by Clifford Lincoln in a letter to his colleagues who were holding a wake in March 1996 (which he could not attend) on the occasion of their group replacement in the office of PS. In sardonic language he wrote:

When I received the Prime Minister’s letter advising me in such lofty and sincere language that I had served my country with intelligence, nobility, dedication and utmost efficiency…I could not help wonder why, if I had been so proficient, I was being fired at the same time.

The frequent rotation of PS’s is not an isolated phenomenon. It has reper- cussions for other elements of the parliamentary system. The natural instinct of a government member whose term as PS has come to an end is to press the party whip to find him or her another office. The chair of a committee is the preferred prize. Usually a number of openings exist, since frequently the government has already appointed a number of chairpersons to the vacant PS positions. And so another round of musical chairs takes place.

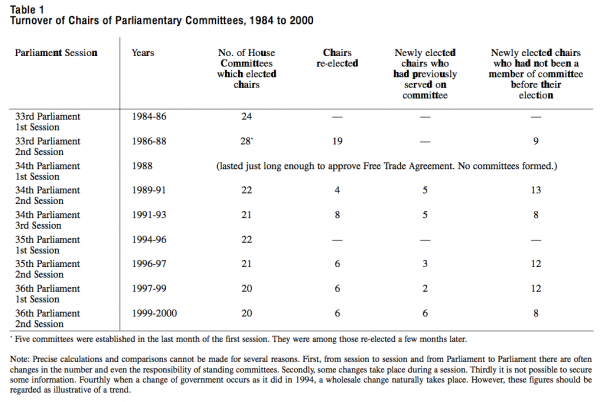

The high turnover among chairpersons, due to the rotation of PS’s, is recorded in Table 1. Apart from the complete change that occurs when a new party takes power, the only exception to the comprehensive change every two years was Prime Minister Mulroney’s decision to leave the majority of chairper- sons in office during the four years of the 33rd Parliament (1984-88).

The consequences of the regular rotation of PS’s are much more serious nowa- days than they were in 1970 when Prime Minister Trudeau initiated the practice. At that time, committees only met during a three-month period to review the estimates — a frustrating and unproductive task — unless they received a special order from the House, something that happened infrequently. Therefore, the lack of continuity of chairs of committees was of little consequence. In 1985, however, Prime Minister Mulroney’s government gave committees the power to meet when they wished and to set their own agendas. Committees thereby acquired a potential that had not pre- viously existed and a committee chairmanship offered the prospect of a substantial- ly enhanced role for private members. But to realize this potential, chairs need to remain in office long enough to learn about the subject for which the committee is responsible and to master the skills of presiding. More importantly, it also takes time to gain the confidence of the members of the committee, particularly those from the opposition. The frequent turnover of committee chairs has, as a result, hindered their effectiveness and that of their committees.2

So it was that a practice, introduced by Mr. Trudeau to share among mem- bers of the government caucus the material rewards and the responsibilities that come with the office of parliamentary secretary, became — once committees were given by Prime Minister Mulroney the right to meet year round — a constraint on the effectiveness of committees.3 The consequences were well expressed by John Harvard at the May 10, 2000 meeting on Parliament Hill, when he (at the time chair of the Agriculture Committee) said:

Now with respect to the stability of committees, I think it is crazy the way we rotate. I have been chairman of agriculture for two years. I think I am a better chairman now than I was two years ago….I hope I have learned something and I would hope — are you listening, whip? — I would hope that I could have this job come the fall because I think I can contribute more. I also look around to my com- mittee members. I know that those who have been on there for a year or two are doing a much better job now than they were when they started. I really think that committee members should be appointed for the life of a Parliament.4

When committees were formed after the election of November 2000, Harvard was no longer a member of the Agriculture Committee. Nor is he chair of either of the two committees on which he now serves.

Having identified the consequences of rotating PS’s every two years, it is appropriate to examine the accuracy of the PMO’s assertion about past practice in its statement of February 1996: “the Prime Minister has adopted the practice of previous governments of completely rotating parliamentary secretaries.”

Mr. Chrétien has indeed closely followed the practice initiated by Prime Minister Trudeau, who, in 1970, amended the law governing the office of parliamentary secretary, increasing the number of positions by providing for one PS for each department. He indicated at the time that he intended to rotate incumbents at biennial intervals and that is what he did. The maximum length of continuous service, enjoyed by only four among scores of MPs appointed PS by Mr. Trudeau, was 33 months.

In spite of the assertion in the PMO’s press release of February 1996, the practice with regard to the appointment of PS’s initiated by Mr. Trudeau and closely emulated by Mr. Chrétien actually bears little resemblance to that of other prime ministers, Liberal and Conservative. Under Prime Ministers King, St. Laurent, Diefenbaker, Pearson and Mulroney, effective PS’s were often reappoint- ed to the office for several years. While the terms of some who failed to measure up were not extended, and a few PS’s received different but equally significant positions such as whip or caucus chair, the practice of all five prime ministers was to renew the term of many PS’s — often for the life of the Parliament and even for a second Parliament — and to elevate some directly to the ministry. In short, as this and the following section will demonstrate, these five prime minis- ters treated PS’s as additions to the executive, leaving them in office long enough to learn the job and make a contribution, while also treating the office as a test- ing ground for ministers. In effect, the PS position offered for effective incum- bents a kind of career path.

A detailed examination of the approach to the office of PS of each of the five prime ministers named above will reveal a few differences. Some prime min- isters reappointed PS’s to the same ministry for many years, while others moved a PS through as many as three and, very occasionally, four or more departments. Not surprisingly their practice was influenced by the situation they faced: whether they headed majority or minority governments, how many governments they led, and the turnover in membership of the governing party from one elec- tion to the next. These different conditions, for example, affected the options open to Mr. Diefenbaker. He led two minority governments, interspersed by a Parliament with the largest government majority until that time, and as a result he faced a rapidly changing scene. But all of these five prime ministers reap- pointed several PS’s for a number of successive terms, which permitted these members to feel that their contribution was recognized in a tangible way and ensured a measure of stability in parliamentary offices.

This conclusion runs counter to the few previous studies of the office of PS, which have reported that the average term of incumbents lasted between one and two years only.5 The authors appear to have reached this conclusion by counting a shift of ministry for a given individual as a different appointment, even when the new appointment was announced the next day. In addition, some prime ministers, such as Mr. Pearson, terminated appointments when calling an election, but then reappointed them immediately after the election. Others, such as Mr. Mulroney, left PS’s in office until the next election took place and imme- diately reappointed some. In this study, we treat reappointments of this sort as continuous service. Applying this methodology reveals considerable stability in PS postings and suggests that these five prime ministers regarded appointments to that office as a launch on a potential career path. MPs who proved their worth could usually expect to be re-appointed or even promoted to the ministry.

The next section describes in detail how Prime Ministers King, St. Laurent, Diefenbaker, Pearson and Mulroney handled appointments to the office of par- liamentary secretary. The commentaries are supported by tables in the Appendix, detailing the length of service, along with promotion and demotion patterns, for all PS’s appointed by each leader.

The position of parliamentary secretary in the Canadian Parliament was first established by order-in-council during the Great War of 1914-18 to provide sup- port to overworked ministers. Three MPs were appointed to the position by Prime Minister Borden, but the office lapsed with the defeat of his government in 1921. The position was revived by Prime Minister King during the Second World War for the same reason, with seven order-in-council appointments made in 1943. Of the seven initial appointments, five were elevated to the cabinet at the end of the war, evidence that their competence had been demonstrated to Mr. King during their term as parliamentary secretaries.

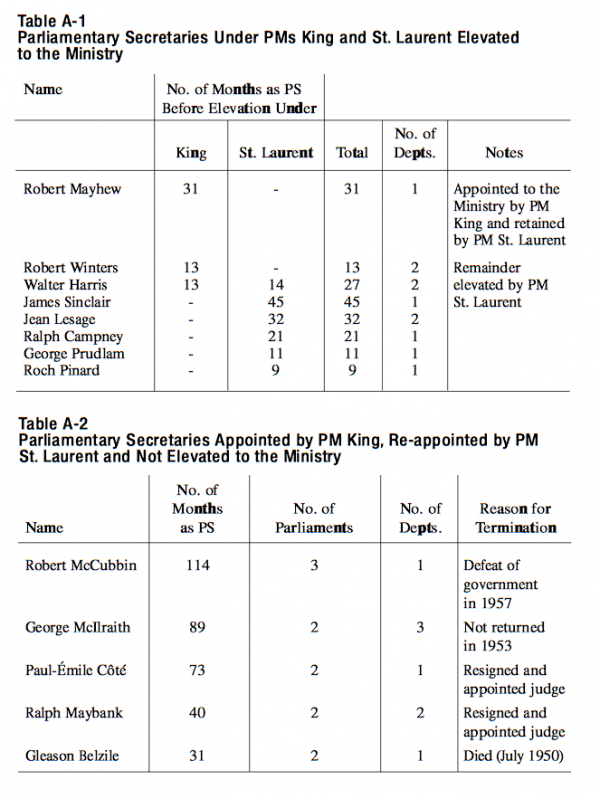

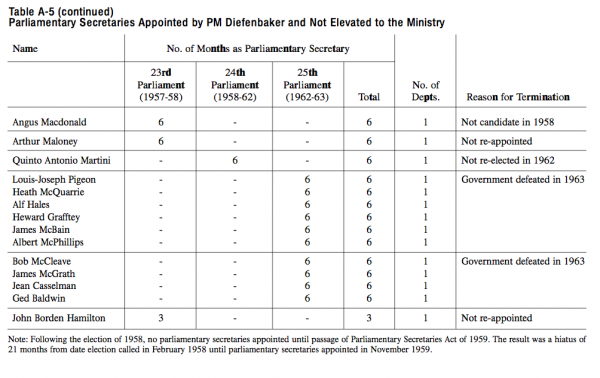

Starting at the end of the war, the three years of Liberal government under Mr. King and the nine subsequent years under Mr. St. Laurent can be regarded as a continuum. Mr. King continued to appoint PS’s after the war to replace those members who had been elevated to the ministry. One was made a minister by Mr. King after serving 31 months as PS; two others were subsequently elevated to the ministry by Prime Minister St. Laurent (see Table A-1).

In all, Mr. St. Laurent elevated eight MPs who had served apprenticeships as PS’s directly to the ministry. Table A-1 indicates how long each served as PS before being appointed to the ministry, including their length of service under Mr. King (if any) and Mr. St. Laurent. These apprenticeships ranged from 9 to 45 months. Thus, the typical practice under Mr. St. Laurent was to test ministerial appointees in the office of PS and to name them to the cabinet directly from that position.

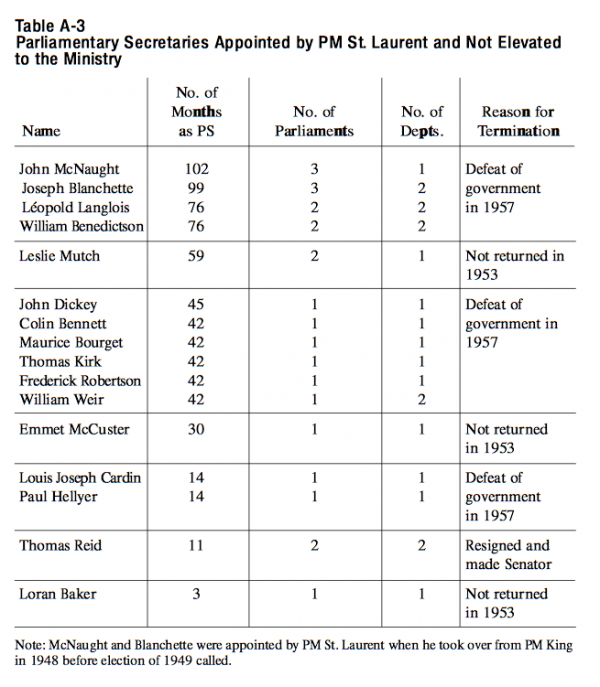

The next two tables record the number of successive years that MPs who were not elevated to the ministry served as PS’s under these two prime ministers. Table A-2 covers those who were first appointed as PS by Mr. King, and subse- quently extended in that office by Mr. St. Laurent. It is noteworthy that three of the five served continuously for six to ten years under the two prime ministers. Table A-3 lists those first appointed by Mr. St. Laurent. Again, four of the sixteen members served six or more years and two-thirds held the office for over three and a half years. Significantly, none of the MPs appointed PS by Mr. St. Laurent were returned to the back benches.

The message is clear. When Prime Ministers King and St. Laurent named PS’s, they regarded the appointment as a first step up a ladder. It could lead to the ministry. However, those who were not elevated could nevertheless expect continuous service as PS providing they were effective. This approach gave appointees both an opportunity to demonstrate their mettle and sufficient time in office to make a personal contribution. The total numbers appointed were small and the office was clearly perceived as a way to strengthen the ministry.

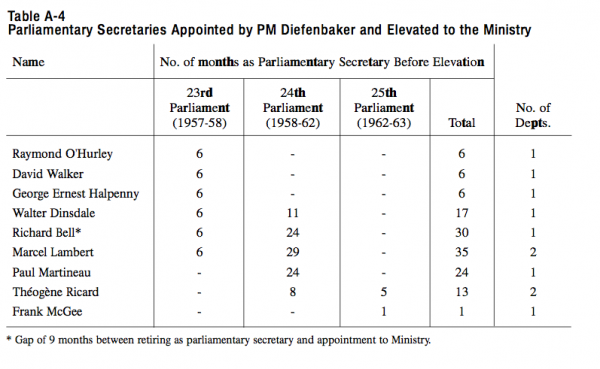

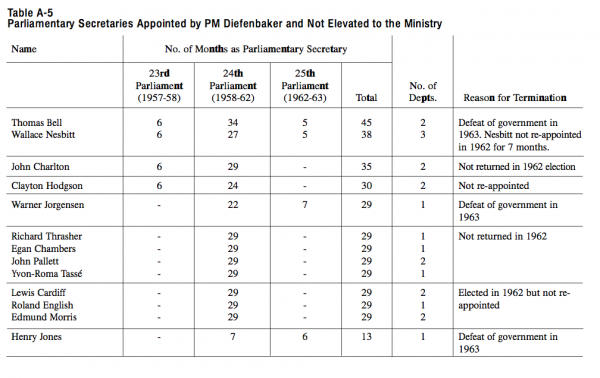

The three Diefenbaker governments lacked the stability of the preceding Liberal governments and this was reflected in the appointment of PS’s. Following nine months of minority government, in 1958 Mr. Diefenbaker won the largest majority achieved up to that time, which was in turn followed by another minor- ity government in 1962. PS appointments were accordingly affected by the large turnover of government MPs.

Following his 1958 election victory, Mr. Diefenbaker decided to increase the number of PS’s to 16 and to establish the office by legislation, rather than making order-in-council appointments. Pending passage of the Parliamentary Secretaries bill he made no appointments. Indeed, there was a lapse of 21 months between the calling of the election in February 1958 and the first appointments under the bill in the autumn of 1959. However, this study treats as continuous service PS’s appointed for the 23rd Parliament (1957-8) providing they were included in the first round of appointments in the 24th Parliament (1958-62).

The first point to be noted is that Mr. Diefenbaker appointed nine minis- ters after they had been tested as PS’s (see Table A-4). With one exception they were raised from PS to minister directly. Two of them served terms as PS in two successive Parliaments before their elevation.

As for PS’s who were not made minister, the combination of the interval of 21 months (while the bill was being drafted and passed) and the number of Progressive Conservative members defeated in 1962, leads to a record that is harder to analyse. Table A-5 indicates that, of the 27 appointments to the office, only six were not reap- pointed. Seven were defeated in 1958 or 1962 and therefore not available for reap- pointment. New appointments in 1962 — of which there were quite a few due to the large number of government members defeated in the election that year — had a max- imum of six months in office, before the government fell. In all, PS’s held office for only 47 months during the three Diefenbaker ministries. So, while PS’s under Prime Minister Diefenbaker enjoyed a less evident career path than they did under Mr. St. Laurent, it is equally clear that he was not following a policy of regular rotation.

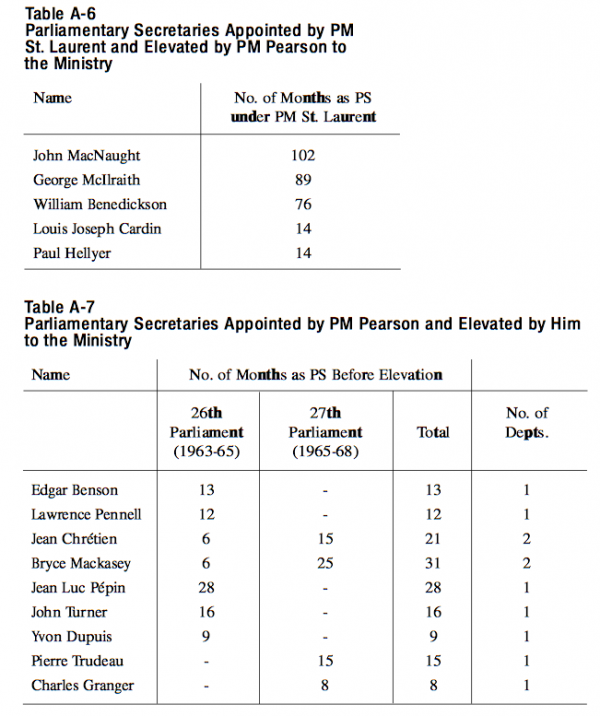

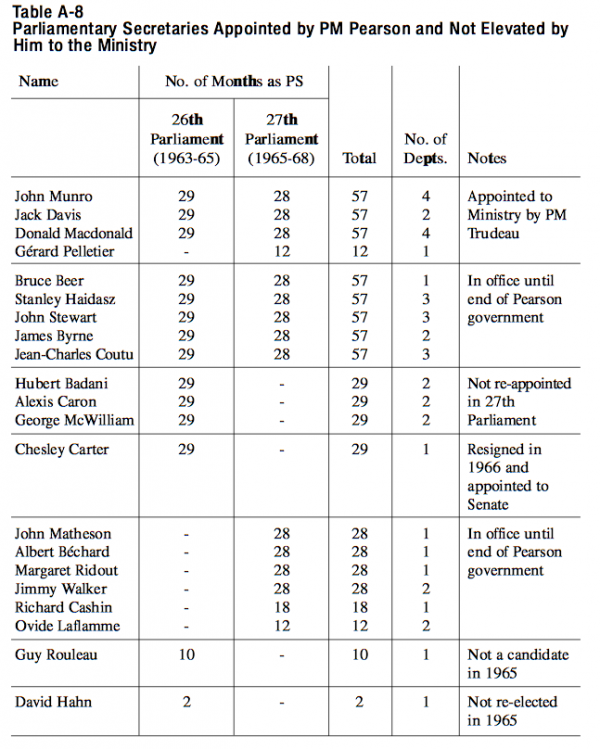

The same is true of Prime Minister Pearson. The record during his time in office makes it clear that he looked on parliamentary secretaries as junior mem- bers of the government, potentially available for promotion. When he assumed office in 1963, he immediately named five men to the cabinet who had earlier served as PS’s under Mr. St. Laurent. Of these, three had over six continuous years in that office (Table A-6). Subsequently Mr. Pearson appointed nine other members to the ministry following a period as PS. These included Mr. Trudeau and Mr. Chrétien (Table A-7).

Meanwhile, those PS’s not promoted to cabinet by Mr. Pearson were gener- ally kept in the position for an extended period. As Table A-8 shows, eight of the twelve PS’s appointed at the beginning of the 26th Parliament (1963-65) served the full term and were reappointed to that office in the 27th Parliament (1965-68), where they again served for the full term; while among the seven MPs first appoint- ed to the office of PS in the 27th Parliament, four served for the full term. In addi- tion, a handful of PS’s appointed by Mr. Pearson, most long-serving, were eventu- ally named cabinet ministers by Prime Minister Trudeau. The only significant movement in the PS position during the Pearson years was departmental rotation, as Mr. Pearson moved a number of PS’s to two, three or even four ministries.

Prime Minister Mulroney adopted broadly similar practices. He, however, had to manage a larger complement of PS’s, as he inherited the law on parlia- mentary secretaries introduced by Mr. Trudeau which provided for a PS for each department. When Mr. Mulroney greatly expanded the number of Secretaries of State (ministers who do not sit in cabinet), this automatically opened up more PS positions. In fact, there were so many offices created that he often made a PS responsible for two or even three departments or agencies at the same time.

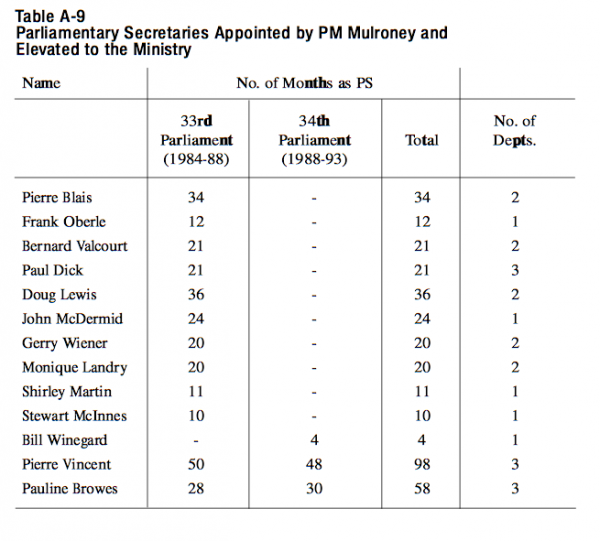

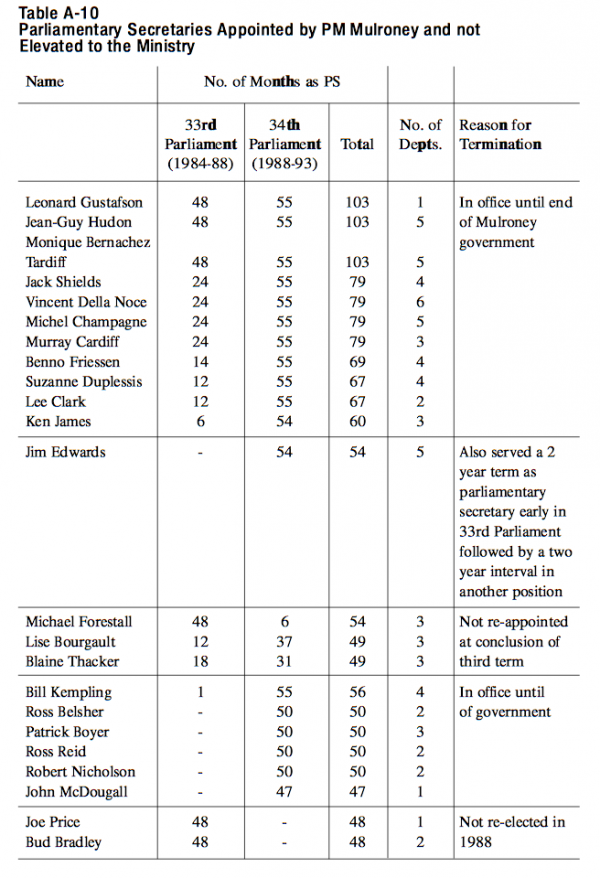

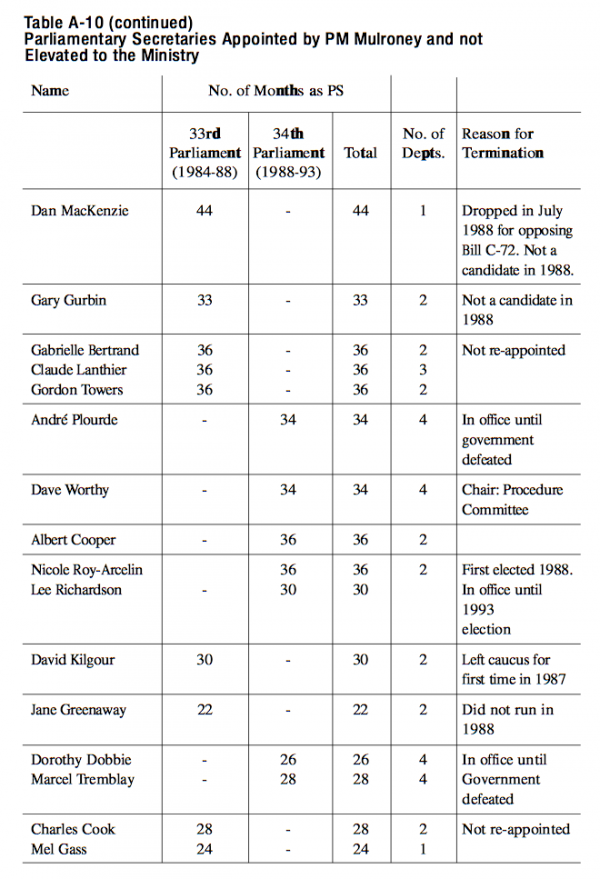

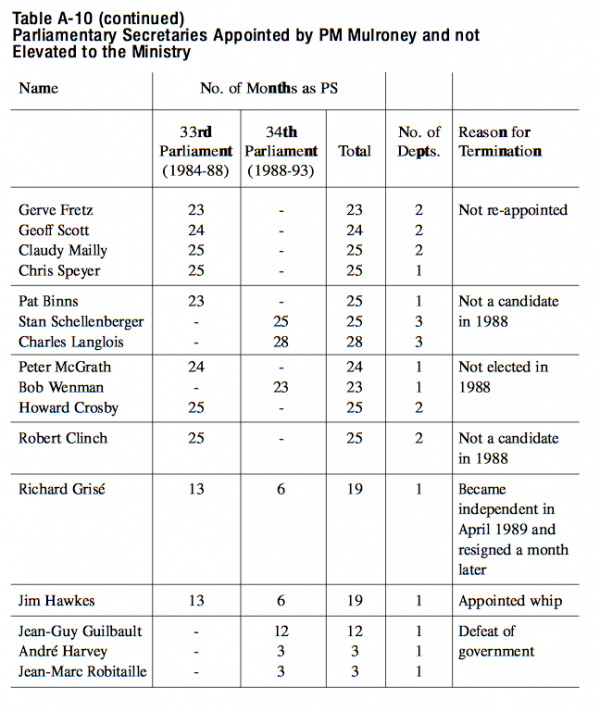

Thirteen persons whom Mr. Mulroney appointed as minister first served as PS, one for over eight years and two others for three or more years (see Table A-9). As for those who were not elevated to the ministry, 22 remained as PS for at least four years of continuous service. Indeed, three remained in office during the entire eight and a half years that Mr. Mulroney was Prime Minister and another eight held the office from five to six and a half years (see Table A-10). Leonard Gustafson remained Mr. Mulroney’s parliamentary secretary for the whole period, surely evi- dence of the value that the Prime Minister saw in stability in the office.

MPs are usually delighted when first appointed to the position of PS, particular- ly if they are assigned to a major ministry. Once in the position, their sense of sat- isfaction depends on the extent to which the minister to whom they report gives them substantive responsibility. Results vary: some are gratified, others frustrat- ed. But when the two-year term comes to an end and they are replaced by a col- league, disappointment is a common reaction.

The government also loses an asset. It takes time for MPs when first appointed as PS to a ministry to learn enough of the substance of the depart- ment’s business to make a contribution, less time of course if they are already knowledgeable about the subject. They also have to learn how to speak for the department in the House and in public and they need time to gain the confidence of their minister and of departmental officials. Contrary to the claim frequently made when new appointments are announced that a short term as PS helps the incumbent to gain new experience, the aphorism “Jack of all trades, master of none” is closer to the truth. From the perspective of ministers, if they knew that their parliamentary secretary might be assigned to the department for several years, they would normally be inclined to allocate greater responsibility to incumbents, perhaps even to make them responsible for evaluating advice on a segment of the department’s mandate.

The practice of rotating PS’s every two years seems to presume that unrest in the government caucus is kept in check by giving as many government members as possible the opportunity to serve as PS and to benefit from the additional compen- sation attached to the office. The objective is to “share the wealth” and avoid a situ- ation where some members appear to be given preferred treatment. Unfortunately, this approach and the musical chairs it engenders means that private members rarely remain long enough in a position of responsibility to make a contribution. In a world of increasing specialization, a member who has had sustained involvement in one field of activity is more likely at the end of his or her time in Parliament to be able to point to personal achievements. Parliament too would be better served if members attained a reasonable level of expertise in specific policy areas.

There are a limited number of PS positions, so that a decision to return to the practice of reappointing some PS’s for several years would mean that a large majority of the remaining private members in the government party could not aspire to an appointment to that position. At first sight, Prime Ministers King, St. Laurent, Diefenbaker and Pearson might have faced this problem, because com- mittees, which can offer another career path, were not then meeting on a regular basis. That private members under these leaders did not appear to be frustrated by this situation can be accounted for by two facts: under Prime Ministers King and St. Laurent, the House of Commons was the centre of genuine debate that influenced policy; and under Prime Ministers Diefenbaker and Pearson, there were four minority parliaments which meant that debate in the House remained engrossing and the outcome of votes was never certain.

Because these conditions no longer apply, unhappiness on the back bench- es might be anticipated if the regular rotation of PS’s was abandoned. But a solu- tion to this potential problem now exists: if parliamentary committees had greater stability of membership, leading to more effective work, they could offer an impor- tant alternative source of fulfilling activity and avenue of career advancement. The fact that a few committees have undertaken important and challenging work, which has been taken seriously by the government, proves the point.

Thus, active and productive committees offer a possible solution to the dif- ficulty that would be faced by a government if PS’s were to be reappointed rather than rotated. The challenge would be to provide an alternative career path for those not appointed as PS. If private members were to be offered continuity of service on committees, they would have time to learn about the subject for which the committee is responsible, permitting them to gain the detailed knowledge needed to hold departments to account. With continuity of membership, com- mittees could make longer-term plans, learn how to work together and not have to start anew every year or two. In addition, as members gained experience on a committee and demonstrated their competence, they should have the opportu- nity to work their way upward by becoming a sub-committee chair or vice-chair of the full committee, and eventually chair of the whole committee.

Continuous service on a committee could thus become a career path for government members, and indeed for members of all parties. It is noteworthy that lengthier service on committees was strongly supported by MPs who responded to a questionnaire circulated in May 2000 by the Parliamentary Centre. Over 80 percent favoured greater stability of chairpersons and commit- tee members and supported appointments to committees for two years or more.6

For these changes to happen, political parties would have to decide that they were prepared to extend the term of committee appointments. In addition, the government would have to be prepared to recognize seniority and competence as criteria for the election of chairs, as well as looking for ways to enhance the signif- icance and value of committee work. Supplementary compensation for chairs and vice-chairs would also remove one ground for rotating PS’s and committee chairs.

It has been argued that, with the increase in the 1980s in the number of secretary of state positions, a government has less need for experienced PS’s. There is some validity to this claim. Nevertheless, government has become more complex and Mr. Mulroney, who appointed a large number of secretaries of state, likewise found it worthwhile to extend the terms of competent PS’s.

A decision by government to revert to the practice of reappointing com- petent PS’s for multiple terms would bring several benefits. Incumbents would have the time to gain skills and expertise and so strengthen the ministry. Stability in the PS position would remove a principal cause for the regular replacement of committee chairpersons, a process that has seriously limited the latter’s effective- ness. It should also then be possible to stabilize committee membership, a move that would further add to their productivity. Together these steps would offer pri- vate members more predictable, satisfying and constructive career paths — and would make the House of Commons a more effective and productive institution.

For Immediate Distribution – Wednesday, September 19, 2001

Montreal – The biennial rotation of Parliamentary Secretaries (PS’s) took place last Thursday, September 13, as anticipated. However, Peter Dobell, the Founding Director of the Parliamentary Centre, says a return to the practice of reappointing competent PS’s for multiple terms, instead of rotating them every two years, would improve the House of Commons’ efficiency and provide more continuity for committee chairs. The Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP) announces the release of a new paper entitled Parliamentary Secretaries: The Consequences of Constant Rotation. In this 30- page study, Dobell analyses how appointments have been made since the office was first established and assesses the consequences of biennial rotation, a practice that was initiated by Prime Minister Trudeau and taken up by Prime Minister Chrétien.

“Under the present practice, PS’s know that after two years in the post their appointment will not be renewed regardless of how well they perform,” says Dobell. The rotation thus creates a natural sense of disappointment at the end of the two-year term. And, since it takes time for PS’s to learn the substance of a department’s business, the rotation hinders their effectiveness. “Consequently, ministers have little incentive to assign them significant responsibility.”

The author adds that the frequent rotation of PS’s is not an isolated phenomenon since it has repercussions for other elements of the parliamentary system, in particular parliamentary committees. Indeed, those rotated out of the position of PS usually press their party whip to find them another office. The chair of a committee is the preferred prize and frequently several openings exist, since a number of chairpersons have usually been appointed to the vacant PS positions. And so another round of musical chairs takes place, weakening the continuity that could strengthen committee work.

The IRPP study concludes that a decision by government to revert to the practice of reappointing competent PS’s for multiple terms, instead of rotating them every two years, would bring several benefits:

– Incumbents would have time to gain skills and expertise and so strengthen their department;

– Stability in the PS position would remove a principal cause for the regular replacement of committee chairpersons, a process that has seriously limited the latter’s effectiveness;

– Together these steps would offer private members more predictable, satisfying and constructive career paths – and would make the House of Commons a more effective and productive institution.

The author notes that “for these changes to happen, political parties would have to decide that they were prepared to extend the term of committee appointments. In addition, the government would have to be prepared to recognize seniority and competence as criteria for the election of chairs, as well as looking for ways to enhance the significance and value of committee work.”

Parliamentary Secretaries: The Consequences of Constant Rotation, the latest Policy Matters paper in IRPP’s Strengthening Canadian Democracy series, is now available on the IRPP Website at www.irpp.org – simply click on the “What’s New” icon on the homepage.

– 30 –

For more information, or to schedule an interview with Peter Dobell, please contact IRPP.

To receive IRPP media advisories and news releases via e-mail, please subscribe to the IRPP e-distribution service by visiting the newsroom on the IRPP Website.

Founded in 1972, IRPP is an independent, national, nonprofit organization whose mission is to improve public policy in Canada by generating research, providing insight and sparking debate that will contribute to the public policy decision-making process and strengthen the quality of the public policy decisions made by Canadian governments, citizens, institutions and organizations.

Quotes from the Study

“The net result is that a practice, introduced by Mr. Trudeau to share among members of the government caucus the material rewards and the responsibilities that come with the office of PS, has become an important constraint on the effectiveness of committees.” Page 3

“When the two years come to an end and (PS’s) are replaced by a colleague, the natural reaction is disappointment, even a sense of rejection.” Page 9

“The consequences of the regular rotation of PS’s are much more serious nowadays than they were in 1970 when Prime Minister Trudeau initiated the practice.” Page 10

“From the perspective of ministers, if they knew that their PS might be assigned to the department for several years, they would normally be inclined to allocate greater responsibility to incumbents, perhaps even to make them responsible for evaluating advice on a segment of the department’s mandate.” Page 17

“In a world of increasing specialization, a member who has had sustained involvement in one field of activity is more likely at the end of his or her time in Parliament to be able to point to personal achievements. Parliament too would be better served if members attained a reasonable level of expertise in specific policy areas.” Page 17

“Continuous service on a committee could thus become a career path for government members, and indeed for members of all parties.” Page 18

Strengthening Canadian Democracy

Research Directors: André Blais (University of Montreal), Paul Howe (University of New Brunswick) and Richard Johnston (University of British Columbia)

Since the 1960s, increased levels of education and changing social values have prompted calls for increased democratic participation, both in Canada and internationally. Some modest reforms have been implemented in this country, but for the most part the avenues provided for public participation lag behind the demand. The Strengthening Canadian Democracy research program explores some of the democratic lacunae in Canada’s political system. In proposing reforms, the focus is on how the legitimacy of our system of government can be strengthened before disengagement from politics and public alienation accelerate unduly.

Publications that have appeared under this thematic include (all available free of charge on the IRPP Website at www. irpp.org):

– Henry Milner, “Civic Literacy in Comparative Context: Why Canadians Should Be Concerned,” Policy Matters (July 2001).

– Matthew Mendelsohn and Andrew Parkin, “Introducing Direct Democracy in Canada,” Choices (June 2001).

– Don Blake, “Electoral Democracy in the Provinces,” Choices (March 2001).

– Louis Massicotte, “Changing the Canadian Electoral System,” Choices (February 2001).

– Jerome Black, “The National Register of Electors: Raising Questions About the New Approach to Voter Registration in Canada,” Policy Matters (December 2000).

– Peter Dobell, “Reforming Parliamentary Practice: The Views of MPs,” Policy Matters (December 2000).

– Peter Dobell, “What Could Canadians Expect From a Minority Government,” Policy Matters (November 2000).

– Richard Johnston, “Canadians Elections at the Millennium,” Choices (September 2000).

– Paul Howe and David Northrup, “Strengthening Canadian Democracy: The Views of Canadians,” Policy Matters (July 2000).

– Jennifer Smith and Herman Bakvis, “Changing Dynamics in Election Campaign Finance: Critical Issues in Canada and the United States,” Policy Matters (July 2000).

Research on the following topics is currently underway:

– The impact of the media on attitudes towards democracy in Canada.

– Generational patterns in political opinions and behaviour of Canadians.

– Evaluating the national register of electors.