Recent research carried out by organizations such as the World Bank, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United Nations and many other bilateral donors has drawn a clear link between the incidence of conflict, high levels of poverty, and underdevelop- ment. When crises occur, military and security forces will often be tempted to move into the power vacuum created by the collapse of state structures, operating outside the control of demo- cratic institutions. As a result, states become unable to guarantee the security of their citizens and state structures lose their legitimacy.

The relationship between conflict prevention and sustainable development has forced policy- makers and practitioners to develop ways and means of reforming a country’s security sector at the earliest possible stages of intervention. Security sector reform (SSR) has, in the past, been conventionally addressed by development departments. However, there is now clear evi- dence that SSR strategies must be factored into pre-conflict, conflict and postconflict planning; they are not an issue for consideration just dur- ing postconflict reconstruction. This has impli- cations for joint consultation and planning between all relevant ministries of donor coun- tries, requiring policy provisions to be made dur- ing each stage of intervention. Lessons learned from Cambodia, Haiti, Bosnia, Kosovo and Sierra Leone provide just a few examples of where the mismanaged sequencing of activities led to fur- ther problems. More immediately, this is rele- vant to postconflict challenges in Iraq.

Undoubtedly, the core business of the military is security. However, at the highest strategic lev- els, the mandates and desired endstates of inter- vention forces must reflect the needs of the wider development agenda for the host country and region. Before military troops hand over pri- macy to other external actors such as interna- tional police forces; authorities responsible for disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) programs; or local newly trained military forces and democratic civilian oversight mecha- nisms, they must have a clear idea of the longer- term agenda to which their short-term intervention strategy contributes – particularly if the intervention continues but shifts into a sup- porting role only, during which local authorities gain primacy.

This paper discusses the importance of joined- up government planning to support military intervention in countries that require complete reform, or perhaps partial transformation, of their security sectors. It outlines the key actors and activities involved in wider security sector issues, and it examines the linkages between SSR and peace support operations, small arms and light weapons, DDR programs, and civil society. Further, it discusses the importance of building these issues into the doctrine and the policy and planning capacity of international military forces.

Security sector reform (SSR) is a subject that has garnered significant attention from the development community and has crystallized into a debate that has been tack- led holistically by the national governments, as well as by many multilateral and nongovernment actors.1 While efforts to generate and build on the theory and concepts have encouraged the devel- opment of wider approaches and mindsets, the way in which these concepts have been translated into practice remains unclear at worst, and dis- parate at best.

It is necessary to acknowledge the wide spec- trum of activities and actors involved in SSR issues, and the institutional co-operation this implies both at the international and local levels. For example, it is impossible to initiate a com- prehensive military reform program without addressing legal and constitutional frameworks that ensure an acceptable degree of accountabili- ty from and transparency of the armed forces. Similarly, a country’s defence sector cannot undergo a completely successful transformation without equal efforts being extended to the reform of the internal security forces and their civilian oversight mechanisms, such as the police and judicial systems. The plans to overthrow Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq will result in an extensive agenda for the international communi- ty to take on, particularly with regard to Iraq’s security structures — a potential vacuum which, if left unaddressed, will have a further fractious effect on the region.

While a plethora of additional humanitarian and civil protection responsibilities (which have come in the early stages of many recent military interventions) has triggered cries of “mission creep” from national military contributors, today’s interventionists must be cognizant of the wider security needs of the transitioning soci- eties to which they are deployed. This notion bridges the gap between the emergency response phases of a conflict and the wider development agenda — a gap which, if left, can have a enor- mous destabilizing effect on a society, and re- ignite the roots of the conflict quite quickly.

This paper examines security in its broader context and identifies the key actors and activi- ties of the wider security sector. It gives an overview of the main program and policy areas for SSR and discusses the potential contribution of international military forces to each of these areas. Lastly, this paper looks at the current state of doctrine for peace support operations, and the operational training that supports contemporary approaches to peace operations, and makes rec- ommendations as to how SSR concepts can be blended into strategic planning and policy to account for the evolving developmentalization of security.

The agenda for international military forces has always included elements of broader security concerns, many of which are addressed in the later stages of a con- flict intervention, also known as the “postconflict development” or “postconflict reconstruction” phases. For example, international military forces serving under the NATO Stabilisation Force (SFOR) mandate in Bosnia now find themselves responsible for operations such as minority returns, the settlement of internally displaced persons (IDPs), the support of mine action pro- grams and the collection of small arms and light weapons (SALW) caches from an array of differ- ent areas in the country. More recently, in Afghanistan, British forces serving in Kabul have focused on garnering local support through the implementation of “quick impact programs,” which have included community rebuilding and local integration programs.2

Even in different types of interventions, such as NATO’s Kosovo Force (KFOR) and the British Army’s ongoing operations in Northern Ireland, a focus on the need for civil protection for minor- ity groups dominates the agenda. Both cases have parallels with experiences in Haiti, El Salvador and other internal crises where internal policing became the priority, and the international mili- tary forces strove to reach an endstate where the police could regain primacy. This will be impor- tant in Iraq. Although events in Northern Ireland have progressed to a level where the Royal Ulster Constabulary has held primacy since the early 1990s, the military still plays a support role to boost the effectiveness of the overall security sec- tor and works toward achieving wider develop- ment goals.

Due to the complex and multidisciplinary nature of the subject, SSR has recently been iden- tified as one of the most important challenges facing a range of government ministries and agencies. Chris Smith, of King’s College, London University, suggests that the academic history behind the evolution of SSR is one of fits and starts, lacking continuity and lucidity.3 It has emerged with the wider examination of military institutions in the Third World and with the study of defence diplomacy or the development of democratic market-based defence forces. Important linkages have also been drawn between defence expenditures and economic development in these countries, which is often seen in bloated defence budgets and the absence of any civilian oversight governing the activity of the military.

The subject further evolved when the relation- ship between defence forces and internal securi- ty forces was examined, and it was recognized that in many countries there was little difference between the military, what constituted internal police forces, and systems underpinning justice and the rule of law. A wider security community became identified, which — in addition to the police, the armed forces and the judiciary — included border guards, civil defence forces, intelligence services and paramilitaries. Professor Robin Luckham, from the Institute for Development Studies, Sussex University, describes SSR as

the quintessential governance issue. This is so both in the sense that there is enor- mous potential for the misallocation of resources and also because a security sec- tor out of control can have an enormous impact on governance — indeed, be a source of malgovernance.4

Other academics and practitioners typologize the actors involved in the wider security sector, which include those statutory and nonstatutory security services authorized to use force, civil society actors and oversight mechanisms, and nonstatutory forces that are not authorized to use force on any occasion. Nicole Ball describes the “wider security family” as including

Because this paper will focus on the contribu- tion of the military to SSR activities, a framework will be developed that is slightly more focused than Ball’s list of actors and draws a distinction between the players — the enablers/disablers and the activities/programs — which, collectively, draw on most of Ball’s descriptors listed above.

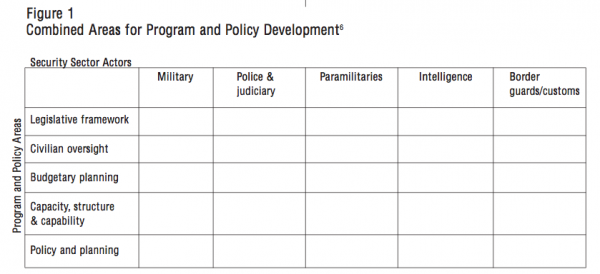

Figure 1 outlines a framework that describes the central players within a country’s security sector along the horizontal axis. These include the intelligence services, the armed forces, the police, the judiciary, paramilitaries, and border and customs officials. A number of policy imperatives, which can serve as “enablers” or “dis- ablers,” are listed along the vertical axis, all of which taken together should underpin the activi- ties of each of the security-related agencies listed below. These include accountable and transpar- ent legislative frameworks, civilian oversight, capacity, structure and capability, and policy and budgetary planning. The application of profes- sional competencies to some of these combined areas results in bilateral and multilateral policy being developed to address the more prominent problems inherent in some of these categories. Examples of this may include the development of programs and policies on United Nations (UN) peacekeeping, Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR), Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW), Democratic Governance and Civilian Policing.

It is important to note that these program areas can respond to the needs of a number of security agencies and their respective enablers/disablers, simultaneously, depending on the program and the way in which it is imple- mented. It is these program areas that this paper will focus on, and not the elements characteriz- ing the vertical and horizontal axes of the model. Moreover, the analyses will draw linkages between each program area and study the impli- cations for international military forces.

The realization that UN peacekeeping spanned a number of undefined modes of military intervention — some of which did not necessarily require a specific “peace” agreement to be in place prior to the deployment of international military forces — brought about a number of new definitions for what constituted peacekeeping in its broader sense. While the United States popularized the term “military operations other than war” (MOOTW),7 the UK crafted the term “peace sup- port operations” (PSO),8 which would serve to embrace all the UN-bespoke “tools of peace” such as peacekeeping, peacemaking, peace enforce- ment and peacebuilding (the details for each can be found in the UN’s 1995 Supplement to the Agenda for Peace).9

Over the last decade, the UK Armed Forces have further developed doctrine and concepts dealing with the broader notion of PSO. As a result, the UK has earned itself the position of custodian for the development of NATO doctrine on PSO, and has served as an influential lead nation on these issues at UN headquarters in New York. Moreover, it has projected these ideas fur- ther afield and has played a role in doctrine development and training in African, Latin American and Southeast Asian countries.

There are essentially three types of military responses to regional war, intra-state war or inter- nal civil strife: 1) a UN-led, UN-endorsed inter- vention, such as the 1992 UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in Bosnia and the UN Mission in Haiti (UNMIH); 2) a regional-organization-led, UN-endorsed intervention, such as NATO’s Implementation Force (IFOR) in Bosnia or the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s initial intervention in Kosovo; or 3) an “executive agent” or coalition-of-the-willing-led, UN-endorsed intervention (the type of interven- tion that the international community is seeing more of due to bureaucratic constraints to rapid reaction, mobility and the high readiness of multinational troops).

The common element to all of these interven- tions is the endorsement of the UN Security Council or, in the case where the Council has, in the past, been gridlocked by the veto of any of the five permanent members, resolutions have still been passed in the UN General Assembly to sanc- tion the efforts of others. Thus, the evolution of programs and policy on United Nations PSO requires continuous support. This will undoubt- edly be facilitated by the UN’s commitment to implementing recommendations for improving UN peacekeeping as articulated in the Brahimi report.10

Recent debate over the situation in Iraq has also prompted the UK government as well as most other European heads of state and interna- tional diplomats to reiterate the importance of international responses to international crises, which implies the need for the response to Iraq to be supported by a UN resolution if possible. Security Council failure to respond only compli- cates the postconflict peace support issues. However, strengthening the expediency of politi- cal decision-making mechanisms must run par- allel to a more robust capacity to respond mili- tarily, even if this capacity is outsourced.

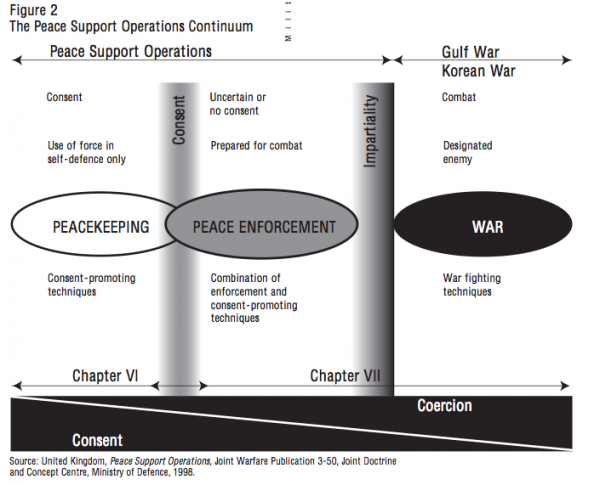

The concept of PSO continues to be defined in terms of level of consent and degree of impartial- ity of the intervening forces. When both these factors are low, the environment tends to be quite volatile, with fighting continuing and little prospect of peace in sight. This is normally char- acterized as a peace enforcement intervention, in which troops are sent into theatre under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, where consent and some- times even a stable government are nonexistent. As the levels of consent and impartiality increase, international military forces often find themselves in a peacekeeping environment, which is typically supported by some sort of interim peace agreement. Figure 2 illustrates this argument.

However, there is often a blurred distinction about what constitutes a pure peacekeeping envi- ronment, as peace agreements can remain quite fragile and often exclude many nonstate actors that perpetuate the violence in the first place. Lastly, a state of peacebuilding comes when the peace agreement has gained wide acceptance, when the international community has secured a degree of local trust and confidence, and when the international military forces take a backseat to the primacy of local actors who develop new democratic roles in an effort to sustain peace.

Not surprisingly, the primary problem with this military model is that it presumes that these states exist on a continuum and that one always precedes the other. All too often we have wit- nessed the case where this continuum works backwards and peace processes disintegrate overnight, as was the case in Sierra Leone in May 2000 when the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) attacked Freetown and caused havoc to ongoing development activities and reform programs. The continuum-based approach therefore does not give the attention it should to backward transi- tional management, or forward, as the state of the security environment regresses. As SSR has tradi- tionally been associated with the last phase on this continuum, and one that is often not reached due to the backward swings characteristic of a regressive peace or flawed intervention, a lack of attention to the wider security issues often serves to impede progress.

It is essential that doctrine and concepts on PSO further evolve to reflect the wider security challenges that can be encountered in a theatre of operations, challenges that should not neces- sarily be left to the peacebuilding, or postcon- flict reconstruction phase of the operation. Intervening military forces should be fully aware of how their activities may impact the development of a new national police force or the rebuilding of a national justice system. Similarly, knowledge acquired on small arms, light weapons, paramilitary groups and excom- batants might usefully feed into the information repositories developed for Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) and SALW programs, which may be more formalized following an interim peace agreement. If a gov- ernment already exists, and the level of consent for the international intervention is high, the role of the peacekeepers should also contribute to strengthening civil society and educating par- liamentarians, journalists and NGOs on the democratic role of the military, something which still undermines levels of public confi- dence in Belgrade, where a relatively stable gov- ernment has now been in place for some time. These local actors play an important role in feeding government policy, advocacy, agenda- setting, educating young opinion formers and in communicating these issues to the greater public.

Efforts to build SSR into PSO doctrine and training should extend to both NATO and UN peacekeeping countries, due to the influence both organizations exert on the policy and proce- dures of troops deployed under their respective organizational mandates. At the moment, large disparities exist in the approaches of different countries in implementing effective peace sup- port activities.11 Different levels of commitment to local dynamics become apparent, particularly in the postconflict phase of an intervention when the more professional national military contrib- utors, normally earmarked for the more intense phases of military activity, are replaced by forces from countries that are more suited to contribut- ing once some degree of peace and stability has been achieved and more of a monitoring and confidence-building role is required by the inter- national military forces. All too often, many peacekeeping contributors in this “second tranche” are quite removed from the current debate on PSO doctrine and training and, as a result, are less committed during this critical stage of SSR programs. The Nigerian-led UN Assistance Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) serves as a good example of where a lead military contributor was ill-prepared for the deterioration of a conflict and failed to respond to the wider security needs that could have prevented the resurgence of violence. For example, despite the initiation of a large-scale DDR program called for in the framework of the 1999 Lomé peace agree- ment,12 Nigerian troops were unsuccessful in deterring further attacks by the RUF on Freetown, a series of which culminated in the hostage- taking of 500 UN peacekeepers. The UN and the British government immediately called for the deployment of troops to solve the hostage crisis, secure the airport and assist the Sierra Leone Army in more credibly deterring further rebel attacks.

Once again, this underlines the danger in using the continuum model, which is still imbued in the mindset of many national mili- taries and aid organizations, and which comes across quite vividly in the illustrations of doc- trine on peace support operations. SSR has been misplaced as an activity in the postconflict- reconstruction or peace-building phases of a con- flict, and is often left to the authority of develop- ment agencies and international peacekeepers, which play only a marginal, and often disinter- ested, support role. Military and civilian inter- ventionists who ignore requirements to reform security sectors in the earlier phases of interven- tion do so at their peril, and they fail to provide more comprehensive solutions to wider security needs. Broadening their stakeholder base and awareness of interrelated activities does not sug- gest a shift toward “mission creep” — security is the core business of the military and SSR issues must be incorporated into their mindset, man- date and operational planning.

The following sections will examine some of the SSR program areas and the potential contri- bution that international military forces could make to these activities. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to address all program areas, the linkages between PSO and police reform, DDR, SALW and civil society will be discussed, albeit each in modest detail only.

As described in earlier sections, the tran- sition from military to civilian polic- ing has been a common element of many complex emergencies and military inter- ventions, particularly in countries where there is a breakdown in the rule of law and civil protec- tion. Generally speaking, there are three circum- stances in which there is need for police reform:

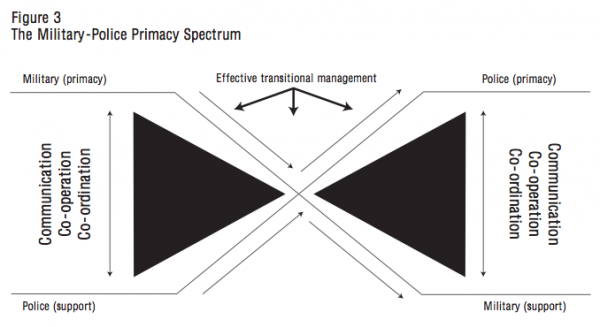

Police reform normally involves a tripartite process, whereby international military forces are initially responsible for securing and stabiliz- ing an environment before handing over to civil authorities. An international civilian police force, such as UNCIVPOL,13 then assumes police primacy as a newly developed or newly reformed force trains under international authorities and prepares for an eventual handover of the civil protection function. Figure 3 illustrates this need for supporting mechanisms to underpin each end of the “military/police primacy spectrum” (see p. 10). If overlooked, the resulting vacuums (shown in black) must be filled for a co-operative and amicable relationship to develop in the future.

During this process it is absolutely critical that the initial military mandate includes an element of civil protection and does not convey the impression that the presence of international peacekeeping forces is merely to offer protection to politicians and international personnel. As a result, peacekeepers must be perceived to be offering credible security guarantees to the majority of the civilian population, or individu- als and groups will go in search of security by other means. Paramilitary groups and warlords who do not have an interest in disarming and demobilizing garner the support of these local groups, who then serve as a prime target market that justifies their continued existence. This sub- sequently makes the job of the international police forces even more difficult, as they lack the local confidence necessary to rebuild a national police force in an environment where local acceptance provides a more promising founda- tion for sustainability.

As outlined in figure 3, in many cases there is a limited distinction between a country’s military force and police force, and the former is usually the dominant ruler of both internal and external security. As a result, the separation of these pow- ers becomes hugely challenging, let alone efforts to encourage the forces to work in concert with each other, as opposed to in competition with each other. Thus, it is difficult to directly draw on the templates used in Northern Ireland and Bosnia for police intervention in Africa, Southeast Asia and Iraq.14 The former cases assume a degree of transparency between the two forces and the willingness to offer mutual support regardless of which party maintains primacy. Other entry points or, perhaps, supporting strate- gies, would have to be developed for different glob- al regions where issues such as primacy and “aid to the civil power” remain unfamiliar terms.

It is therefore essential that issues concerning the rule of law and civil protection be factored into a robust international peacekeeping man- date at the earliest stages of a military interven- tion. This does not mean that the military should take on civilian policing activities, but it should acknowledge the endstate required for both a successful withdrawal of military forces and a well-managed transition to civilian protec- tion for internal security. As a result, a more comprehensive approach to rebuilding the secu- rity sector can be undertaken by both internal and external actors. This underlines the impor- tance of understanding the full security develop- ment spectrum at the earliest stages of interna- tional involvement.

As civil wars and regional conflicts con- tinue to be fuelled by the proliferation of rebel forces, paramilitaries and breakaway armies, the need for effective and com- prehensive Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) programs remains critical for postconflict peace. DDR programs come with enormous social, economic and political implica- tions and, as a result, must be integrated into the wider institutional development strategy.

Questions have been asked as to whether or not a peace agreement must be in place in order to ini- tiate a successful DDR program.15 In most cases, this would be a necessary prerequisite for the wider buy-in of the national government and the neces- sary support for local structures needed to sustain an effective DDR program, such as a national com- mission for DDR. Arguably, much of the relative success of the DDR program in Mozambique could be attributed to the fact that it was strongly sup- ported and subsidized by the Mozambican govern- ment, as well as supported regionally by the South African government. As the successful transition of postapartheid events in South Africa preceded the disarming of RENAMO rebels in Mozambique, bor- der security interests represented one of the many mutual interests between the two countries in sta- bilizing the region. This encouraged South Africa to provide a proactive contribution to Mozam- bique’s DDR process.

The case of the DDR program in Mozambique also opens the debate for more regional solutions to DDR. Small arms and excombatants do not become obsolete easily, are not easily traceable and can continue to operate in vigilant and crim- inal networks beyond the immediate borders of their countries. For example, despite the relative success enjoyed by the National Commission for DDR in Sierra Leone, many RUF fighters are con- tinuing their aggressive action in Liberia, Guinea and the Ivory Coast. Thus, national DDR pro- grams must engage the many existing regional and subregional structures, such as the Economic Community for West African States (ECOWAS), the G-8 countries, the Organization for African Unity (OAU), and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), and encourage them to be instrumental to the wider SSR agenda for the region.

For example, the 1998 deployment of the Nigerian-led ECOMOG force (ECOWAS set up the armed monitoring group, ECOMOG) and the sub- sequent contribution the Nigerian government made to the UNAMSIL force serves as an example of regional solutions to regional problems. Bilateral discussions between the governments of Sierra Leone and Guinea prepared Guinean forces to meet rebel groups attempting to pene- trate the Guinean border, which sent a powerful message to the RUF concerning the support to the international community offered by Sierra Leone’s neighbours. Similarly, immediate efforts to implement UN sanctions on Liberia also sent out an important message and served as an effort to break ties between Liberian leader Charles Taylor and the RUF. The creation of an International Contact Group (ICG) on Liberia (which included France, Monrovia, Senegal, Britain, Nigeria, the UN and ECOWAS) also sought to create stability in the subregion and find a resolution between Liberia’s government forces and the rebel groups.

Beyond the regional level were the consistent efforts at the international level to keep the con- flict in Sierra Leone high on the agenda of the UN Security Council (UNSC). The problem with dia- monds providing an incentive for violence, pay- ing for weapons and fuelling the war was also mitigated by the US-government-led Kimberly Process, which sought to combat the conflict dia- mond trade through the implementation of a global rough diamond certification system.

A more recent trend that has surfaced from ongoing DDR programs is the tendency to con- centrate on the disarmament and demobiliza- tion parts of DDR, but not as much on the rein- tegration aspect. Due to the chronological nature of this equation, donor fatigue tends to have an eroding effect on the DDR programs, creating a reluctance to accept the wider com- munity needs for successful reintegration.16 These difficulties arise from the tendency to dis- aggregate the terms in DDR when, ironically, the emphasis should be on reintegration, with disarmament and demobilization seen as neces- sary prerequisites. Besides a loss of interest and lack of resources, funds are often borrowed from the reintegration budget for stop-gap measures during disarmament and demobilization. Lastly, DDR straddles parts of both the emergency relief and the development domains. As bilateral and multilateral donors and operational agencies increasingly pursue more coherent strategies that place them in only one of these camps, more divisions are created between what may be considered as the more emergency-related phas- es of the DDR program and the longer-term development activities.

Furthermore, the international community often underestimates the economic challenges for the successful reintegration of excombatants when poverty levels characteristic of postwar economies present limited opportunities for civil society. Because of the public disdain for and lack of confidence toward armed forces, there is a reluctance to consider the possibility of reinte- grating excombatants into a democratic armed force as a viable source of employment. The post- war emphasis on downsizing often rules out areas of employment most compatible with the train- ing and core competencies of the excombatants. Should the US-led military intervention in Iraq result in provisional governance by an interna- tional administration, as in Kosovo, the restruc- turing of the security forces, complemented by a well-orchestrated public information campaign, will be quintessential elements for consideration.

Beyond this, however, is the need to focus on the reintegration of the wider community, and not just the excombatants. More effective research, and demographic and market analyses, must underpin DDR programs in order to pro- duce skill sets to support a country’s wider devel- opment needs. For example, the infrastructural rebuilding of roads and bridges to stimulate inter- nal economic activity and improve logistics to attract foreign investors requires engineers and labourers accustomed to working in team envi- ronments. Institutional rebuilding requirements could also produce skill set profiles that could directly influence national DDR objectives.

The wider community may also be affected by large groups of refugees who have either been internally displaced or who have no home to return to. Reintegration strategies must consider these other groups that do not form part of the pool of excombatants but face similar problems with regards to community reintegration. Families of excombatants will also require sup- port, as will former female soldiers who often represent a significant part of a rebel force, as was the case in Eritrea and El Salvador.

Most importantly, DDR programs must be inte- gral to the national plan and link with economic, social and political imperatives. This has impor- tant implications for strategic planning with regards to other strands of the wider security sec- tor and the linkages between programs such as DDR and the development and training of demo- cratic armed forces and a transparent and accountable internal security system. From the highest foreign policy objectives — which are a function of national interests and core values — should be drawn the broader implications for security planning. It is important to note that national interests of many countries will differ from most Western templates, as other societies are built upon different sets of values. Consequently, different objectives to support a national security strategy will be developed.

A national security strategy should therefore embrace all strands of the wider security sector and should clearly articulate objectives and pri- orities for each strand. At the operational level that follows, implementation imperatives for each area should be specified, such as details on national DDR programs, which may then be linked back to the highest levels of a country’s national strategic plan. The same is true for other SSR program areas, such as the requirement for a strategic defence review, a review of national defence expenditure, boosting the degree of civil- ian oversight for security agencies, and perhaps preventive measures like weapons stockpile man- agement and legislation on arms exports. This encourages wider buy-in at all levels of govern- ment, as well as codes of transparency and accountability, which underpin how these objec- tives should be achieved.

The above merely touches on the extent to which PSO, strategic planning for a country’s defence sector and DDR programs are so tightly linked to more comprehensive SSR strategies. The linkages create opportunities for military intervention at the strategic level as well as the operational level. For example, force comman- ders negotiating with local governments must be aware of how the international military interven- tion will support other strategic priorities in the national plan, particularly if the international military force is still the dominant actor in the transitioning society.

At the operational level, international mili- taries can contribute information on excombat- ants to local government authorities as well as the appropriate international and local commis- sions tasked with addressing DDR requirements. In addition, they could advise on the type of weapons the commissions could expect to collect prior to encampment and what may be required before rebel soldiers are able to renounce their combatant status. Lastly, the international mili- tary force could contribute to the security of the demobilization camps and advise on the skill sets of excombatants and their applicability in civil- ian employment.

The linkages between SSR and Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) relate to much of what has already been discussed in earlier sections. It is important to acknowledge the relationship between the demand for arms and the perception of a threat and, therefore, the associations between SALW and areas such as policing, international peacekeeping, judicial reform and the role of civil society.

Once again, the common denominator for all of these areas is the place of SALW in the nation- al strategic plan. Implementation objectives and priority areas for security planning across the sectors have wide-reaching implications for SALW programs. For example, the need for legis- lation on central procurement can serve to speci- fy procurement needs for national defence and internal security purposes. Similarly, require- ments for weapons stockpiling and inventory management should also underpin the objectives of all the security service portfolios and be a pri- ority for external actors tasked with assisting in military training and DDR programs.

International military forces can also con- tribute to the planning of SALW programs. As mentioned in earlier sections, UN peacekeepers are often on the ground before any thought has been given to SSR. With a broader understanding of comprehensive SSR requirements and the activities scheduled to ensue following the depar- ture of these forces, peacekeeping troops should be able to provide critical knowledge to other incoming external actors, particularly on excom- batants and armaments. One often assumes that lists documenting the location and details of arms, landmines and rebel forces are readily available. While this has been the case in a very small number of postwar societies, it is certainly not the case for most countries.

Due to the earlier interventions of NATO forces in Bosnia, as well as improved relations between the Bosnian entity armed forces and the interna- tional military forces, SFOR now plays a vital role in mine action programs. The same logic could be used to increase the contribution internation- al peacekeeping forces could make to SSR pro- grams, simply by sharing information on rebel and paramilitary forces, as well as the location of arms caches, types of weapons used, weapons trafficking channels, etc.

In their role as postconflict military training advisers (as with the International Military Assistance Training Teams, which operate in dif- ferent African and Central and Eastern European countries), knowledge of the military’s contribu- tion to SSR and wider development strategies could be communicated to the newly trained forces. This information should also be channelled toward civil society groups in order to boost confidence in the newly formed military force.

As described in the framework outlined in figure 1, as well as in Nicole Ball’s list of members of the wider security family, civil society plays an enormously impor- tant role in the development of democratic secu- rity forces and SSR. Following the end of a civil conflict, particularly when it involves serious human rights abuses by the country’s military and internal security forces, the public percep- tion toward security forces in general is quite negative. The long-lived nature of these forces in many countries prevents civil society from understanding or accepting any other use for the military.

In societies where remnants of elitist and oppressive military regimes still haunt postwar ministries of defence and headquarters of general staffs, parliamentary oversight becomes key to ensuring an acceptable degree of transparency and democracy within military politics. Such is currently the case in Serbia, where civil servants and former generals of Slobodan Milosevic’s regime still hold prominent positions within the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia’s Ministry of Defence. It is essential that these government rep- resentatives be presented with well-informed debates by parliamentarians to ensure political accountability to the wider electorate. Unfor- tunately, newly elected members of Parliament are often ill informed on the essentials of democ- ratic security forces and lack the ability to pose challenging debates. In Belgrade, the fact that the perceived status of a member of Parliament is directly proportional to one’s role in the corporate world precludes any commitment to current debates, particularly in more remote portfolios such as defence and security.17 Similarly, news reporters and editors formally controlled by infor- mation monopolies of the oppressive regimes lack the skills required to conduct investigative, as opposed to sensationalized, journalism.

These problems open opportunities for inter- national nongovernmental agencies (NGOs) to provide support to local actors to strengthen their knowledge and skills and provide a more informed level of oversight to the elected officials. While the role for international military forces here is more marginal than in other SSR-related program areas, the forces can certainly help to inform NGOs and media groups on the activities of newly trained forces, newsworthy information, and areas requiring further research and empiri- cal studies that could be fed into parliamentary questioning. Furthermore, they could engage their own defence ministries to fund capacity- building programs in-country and advise on the democratic control of armed forces and the man- agement of defence resources in market-based environments.

Earlier sections highlighted the need to engage existing regional mechanisms to provide regional solutions for postcon- flict and transitioning states. Also identified was the need for local constituents to develop nation- al plans, in order to secure wider local buy-in to the solutions proposed.

It is essential to underpin both of these imper- atives with clear direction from the international community, or the particular bilateral donors who wish to see themselves engaged in a specific area. More explicitly, a country supporting the postconflict rebuilding of another country must be able to state, categorically, why it has a nation- al interest to do so. All too often national mili- taries and development agencies are deployed overseas with no clear idea of the strategic inter- est supporting their mandate. It is just as impor- tant for the private soldier on the ground as it is for a Western nation’s head of state to fully under- stand why their country is assisting in the effort. If it is simply to fill a widespread humanitari- an/security vacuum, intervention agents should still understand the longer-term objectives and wider development agenda.

This theory must also be applied to supple- mentary support given to these countries, which often falls under the well-known label of “out- reach programs.” For a long time now, many dif- ferent bilateral and multilateral programs have come to the assistance of postconflict and transi- tioning countries by offering foreign military training and courses on peacekeeping. One must sometimes question whether or not this is indeed what these countries are really in need of, and whether or not courses and training on the pro- fessionalization of armed forces might better serve their requirements. More blatantly, what some countries might really desire is training on how to be a professional platoon or company commander, or on how to run an accountable and transparent ministry of defence. After all, what good is the most effectively trained army if it cannot be controlled?

International and national military forces intervening in civil wars, collapsed states and transitioning societies must consider the wider security agenda in their overall mandate, campaign planning, doctrine and training curriculum. SSR requires comprehensive solu- tions and the joined-up government18 efforts of bilateral donors that respond to these problems. In addition, what was traditionally an issue for the postconflict reconstruction group of players must now be seen as an issue for the conflict pre- vention and conflict phases of an intervention. For example, international development agencies and embassy staff should concentrate on preven- tive mechanisms such as better arms export con- trol, legislation on customs and excise, the state of a country’s armed forces and other vulnerabil- ities that could trigger the collapse of the securi- ty sector.

During the conflict phases of an intervention, when international military forces occupy the most prominent position on the ground, mea- sures must be put in place to consider existing security structures and information gathered on the wider security sector, to ensure both better transitional management from military to civil- ian primacy and a sustainable development agen- da. This paper has taken a cursory look at certain SSR program areas such as police reform, DDR, SALW and civil society, and discussed how the work of international military forces can useful- ly contribute to these program areas.

As we live in the shadow of an American-led war on Iraq, the requirement for postconflict peace and support to the security sector remains large and looming questions must be addressed and married with any proposed strategy to install an interim government or an international cus- todial administration. Even in Kosovo, which seems now to have become a long forgotten land for which no one is interested in taking on responsibility (including Serbia), internal securi- ty and civil protection of minority groups, as well as democratic governance, still remain the biggest obstacles to a sustainable peace. Weighed against the postconflict security challenges following a military engagement in Iraq, Kosovo’s problems seem negligible.

The following section will outline specific rec- ommendations to enhance the military’s contribu- tion to SSR at the multilateral and bilateral levels.

“Joined-up” government – It is essential that for- mal mechanisms be developed within states (par- ticularly donor countries) for joined-up decision- making between the relevant ministries that have an interest in SSR issues. This would clearly involve the participation of the ministries of defence, international development, foreign affairs, the interior, and the intelligence services or intelligence and critical infrastructure. SSR steering committees also should be created across these ministries, as should a common pool of funding to which each of the ministries con- tributes. The funding should be used to support policy development on wider security issues and capacity-building initiatives like in-country train- ing and education in regions where the govern- ment has a national interest.

The development of in-depth assessment tools and methodologies – To improve information and knowledge management throughout the relevant ministries, in-depth assessment/analytical tools and methodologies should be produced for coun- try/regional surveys and scoping studies. Other subject experts such as historians and social anthropologists should be brought in to add to these studies to ensure that there is a well- developed information repository for all areas to which the country may be asked to respond.

National defence ministries should be encour- aged to build SSR concepts into their respective doctrine on peace support operations to recog- nize the wider spectrum of security-related activ- ities and the linkages to international military mandates. The concepts should also be factored into campaign planning and into identifying lines of activity that in the past have included issues like humanitarian assistance and support for refugee programs.

National defence ministries should build SSR concepts into their operational training courses and modules, particularly those that prepare new units for rotational deployments to different operational theatres. These courses should include briefings on the relationships and link- ages between PSO and other SSR program activi- ties, as well as the notion of “security develop- ment” beyond military endstates.

National defence ministries should ensure that the concepts of transitional management and change management become integral parts of man- agement modules at the armed forces command and staff colleges. Module managers should spend time applying these concepts to a more compre- hensive understanding of SSR imperatives in PSO.

UN military advisers to permanent diplomatic missions at the UN headquarters in New York should help stimulate the awareness of the rela- tionship between SSR concepts and UN peace- keeping doctrine, particularly within the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations.

More detailed scoping studies and research should be undertaken, as a follow-up to this paper, on the role of international peacekeeping forces in SSR programs and the contribution these forces can make to DDR and SALW programs.

As well, research should be undertaken that looks at the development of national strategic planning tools that work to the benefit of the inter- vention agencies and donor governments, as well as to the benefit of the local government. This will encourage the wider buy-in of local governments to SSR programs and articulate separate and inter- related objectives for each of the security portfo- lios. For external actors, a national strategy will encourage their efforts to work toward a wider development agenda that has already garnered the support of local constituencies.

Ball, Nicole. “Transforming Security Sectors: The World Bank and IMF Approaches.” In Journal of Conflict, Security and Development, Vol. 1, no. 1 (2001), pp 45-66.

Boutros-Ghali, Boutros. Supplement to the Agenda for Peace. New York: UN Publications, 1995.

Fitz-Gerald, Ann. M. “Multinational Land Force Interoperability: Meeting the Challenge of Different Cultural Backgrounds in Chapter VI Peace Support Operations.” In Choices, Vol. 8, no. 3 (August 2002).

Smith, Chris. “Security Sector Reform: Developmental Breakthrough of Institutional Re-engineering?” In Journal of Conflict, Security and Development, Vol. 1, no. 1 (2001), pp. 5-17.

Taft, Julia. “From Promise to Practice: Strengthening UN Capacities for the Prevention of Violent Conflicts.” IPA- UNDP workshop, A Framework for Lasting Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration of Ex-Combatants in Crisis Situations, German House, UN, New York, 12-13 December, 2002.

United Kingdom. Peace Support Operations, Joint Warfare Publication 3-50. Joint Doctrine and Concept Centre, Ministry of Defence, 1998.

United States. Operations, US Army Field Manual, Department of Defense, publication FM 3-0, June 2001.

DDR Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration

ECOMOG ECOWAS Monitoring Group

ECOWAS Economic Community for West African States

IFOR Implementation Force (NATO)

PSO Peace Support Operations

RENAMO Mozambican National Resistance

RUF Revolutionary United Front (Sierra Leone)

SALW Small Arms and Light Weapons

SFOR Stabilization Force

SSR Security Sector Reform

UNAMSIL UN Assistance Mission in Sierra Leone

UNCIVPOL UN Civilian Police

For Immediate Distribution – Sunday, April 13, 2003

Montreal – With Iraq in mind, the emphasis should be on reintegration, with disarmament and demobilization seen as necessary prerequisites. A new study released today by the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP) argues that countries intervening militarily in civil wars, collapsed states and transitional societies need to follow up their war planning with peace planning, giving priority to re-establishing security after the shooting is over. And they must consider the wider security agenda in their overall mandate, campaign planning and training curriculum.

The paper, entitled “Military and Postconflict Security: Implications for American, British and other Allied Force Planning and for Postconflict Iraq,” by Dr. Ann M. Fitz-Gerald of the Department of Defence Management and Security Analysis, Cranfield University, United Kingdom Defence Academy, was written before the US military operations in Iraq began but anticipates it and other military interventions in the future.

“Security is the core business of the military and security sector reform must be incorporated into their mindset, mandate and operational planning,” argues Fitz-Gerald. Referring to the American-led war on Iraq, she says: “the requirement for postconflict peace and support to the security sector remains large and looming questions must be addressed and married with any proposed strategy to install an interim government or an international custodial administration.”

She stresses that overthrowing Saddam Hussein’s regime “will result in an extensive agenda for the international community to take on, particularly with regard to Iraq’s security structures — a potential vacuum which, if left unaddressed, will have a further fractious effect on the region.”

“Military and Postconflict Security” is the latest Choices study to be released as part of IRPP’s National Security and Interoperability series. It is now available on-line in Adobe (.pdf) format on the Institute’s Web site (www.irpp.org).

Please find the summary attached.

Dr. Fitz-Gerald, a Canadian, is also the author of “Multinational Land Force Interoperability: Meeting the Challenge of Different Cultural Backgrounds in Chapter VI Peace Support Operations” (Choices, August 2002), and the co-author of “A National Security Framework for Canada” (Policy Matters, October 2002). These two papers are available free of charge on the Institute’s Web site.

– 30 –

For more information or to schedule an interview, please contact the IRPP.

To receive IRPP media advisories and news releases via E-mail, please subscribe to the IRPP E-distribution service by visiting the newsroom on the IRPP Web site.

Founded in 1972, the IRPP is an independent, national, nonprofit organization whose mission is to improve public policy in Canada by generating research, providing insight and sparking debate that will contribute to the public policy decision-making process and strengthen the quality of the public policy decisions made by governments, citizens, institutions and organizations.