In a span of less than a year, there has been a tectonic change in Canada’s fiscal reality. Up until at least the end of 2007, the expectation among the general public and the budget guardians was that there would be a continuation of federal budget surpluses, debt reduction, and the considerable scope for additional spending and/or tax cuts that began in 1997. However, the recession that began in late 2008 has shifted the debate, at least for the next two years, and in fact the debate has shifted from managing surpluses to tolerating deficits in order to stimulate economic activity.

This temporary suspension of the “no-deficit” era is an opportune time to step back and examine the underlying budget planning framework, which has been largely unchanged over the past 15 years. In this study, Mike Joyce examines federal budgeting since the landmark 1995 budget and shows that, while the fiscal framework met the primary goal of getting the federal government’s fiscal house in order in the late 1990s, it had other, unintended consequences that have undermined credibility and effective budgeting.

A principal element of budgeting, which was adopted by the ChreÌtien government in the 1995 budget, was the introduction of explicit prudence factors (for example, contingency reserve) into the fiscal framework. These prudence factors reduce the amount of fiscal flexibility available for new resource allocation in each annual budget and so reduce the risk of missing budget targets should the economy perform more poorly than forecast. Successive Liberal and Conservative governments have continued this practice, though the Conservatives have shown a greater willingness to push the risk envelope than their Liberal predecessors.

A further consequence of the risk intolerance built into the budget planning framework was that implicit prudence factors were also introduced or retained in order to provide an additional degree of risk protection. The political cost of failing to meet annual fiscal targets was considered so high that, in addition to including explicit prudence factors, successive governments also systematically overand underestimated spending and revenues.

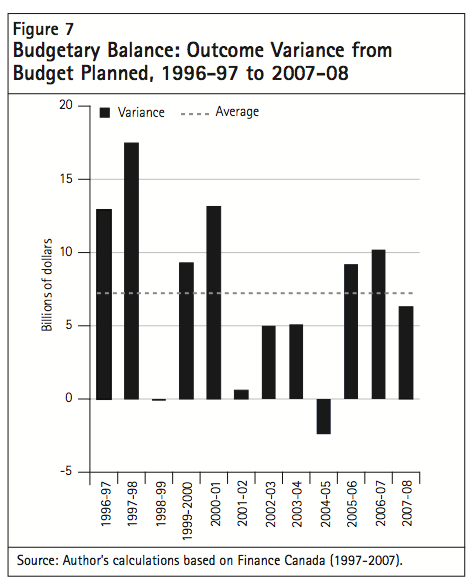

The result was large and persistent annual surpluses averaging $7 billion a year from 1996 to 2007. The author points out that while these surpluses did get Canada back on a sound fiscal footing, they constrained unnecessarily the scope of tax reductions and/or new spending. The author notes that during this period only a minor portion of the new spending room that materialized each fiscal year was actually allocated as part of the regular budget plan and thus subject to thoughtful debate. The rest (that is, unplanned surpluses) became available too late in the fiscal year to be allocated effectively, and so was either spent in a relatively ad hoc fashion or applied to debt reduction. This “fiscal policy by stealth” undermined both the credibility of fiscal forecasts and the transparency of fiscal allocation decisions.

In the context of current deficits, many of the same problems still exist, because the fundamental fiscal arithmetic that frames allocation decisions has not changed. Single-year deficit targets will continue to be highly vulnerable to relatively small variations between revenue and expenditure projections and outcomes (since the surplus or deficit is the difference between two much larger numbers), and even more so in economically turbulent times. Consequently, the incentive to apply excessive implicit prudence to reduce the risk of exceeding the forecast deficit will persist.

The author proposes two remedies that would address the problems in the current federal approach to prudent budgeting. The first is to move from a single-year budget target to one that is expressed as a cumulative total over a multi-year period. Of political necessity, Budget 2009 has tried to shift the focus away from single-year to multi-year targets, and this change should be consolidated and incorporated into the planning framework. This would provide a more credible and effective path back to balanced budgets.

The second is to modify accounting rules that constrain surpluses from being carried forward, in order to enable more flexible management of unanticipated surpluses or deficits. This would allow any part of a surplus that is placed in a notional “savings account” to result in a reduction in the size of the reported surplus when the transfer occurs and the size of the deficit in future years when the account needs to be drawn upon. This is not the case under the current accounting rules – a clear case of rules preventing truly prudent budgeting. Having a rainyday fund like this certainly would have proved useful in the current context of large and growing annual deficits.

In the span of less than one year, there has been a tectonic change in Canada’s fiscal reality. Up until at least the end of 2007, the expectation among both the general public and the budget guardians was for a continuation of federal budget surpluses, debt reduction and the broad scope for additional spending and/or tax cuts that began in 1997. Paul Martin’s famous 1994 remark that he would meet his deficit reduction targets “come hell or high water”1 had become entrenched in the public consciousness, as had his subsequent “balanced-orbetter” budget refrain. For more than 10 years, changes to the budget planning framework developed by the Liberal Party allowed Ottawa to spend and cut taxes without risking a return to deficits. The basic planning framework remained intact after the Conservatives came to power in 2006.

However, the recession that began in late 2008 has shifted the debate from managing surpluses to tolerating deficits in order to stimulate economic activity. The current economic and fiscal climate also calls into question one of the presumptions on which the prudent budget planning framework continues to rest: that annual fiscal targets are to be met or exceeded at any cost. The amount of prudence built into Budget 2008’s fiscal framework for 2009-10 was manifestly insufficient to avoid a return to deficit. The fiscal framework has now been recalibrated, but the increased economic uncertainty will require unrealistically high levels of prudence to provide a reasonable degree of protection against the risk of missing explicit annual fiscal targets.

Temporary suspension of the “no-deficit” era provides an opportunity for us to step back and examine the current budget planning framework. This paper will show that, while that framework has met the primary goal of getting the federal government’s fiscal house in order, it has had other, unintended consequences that have undermined both credibility and effective budgeting.

A principal design element of prudent budgeting is the introduction of explicit prudence factors into the fiscal framework. These prudence factors reduce the amount of fiscal flexibility2 available for allocation in each annual budget and so reduce the risk that budget targets will be missed if the economy performs less well than forecast. The Conservative government has continued this practice, though the Conservatives have shown a greater willingness to push the risk envelope than their Liberal predecessors. From a level in Budget 2006 that was close to the $4-billion firstyear norm established by the Liberals, explicit prudence had been reduced to $2.3 billion by Budget 2008. Perhaps more significantly, the Liberal practice of increasing economic prudence for successive out years was abandoned by the Conservatives in both Budget 2008 and Budget 2009.3

An inevitable concomitant of the risk intolerance built into the budget planning framework, although not by design, is the fact that implicit prudence factors were also introduced or retained in order to provide an additional degree of risk protection. The political costs of failing to meet annual fiscal targets were so high that spending and revenues were systematically overand underestimated beyond the explicit prudence noted above.

With the achievement in 1997 of the first surplus in almost 30 years, one outcome of this budgeting approach was that it allowed for a fiscal planning stance of allocating fiscal flexibility in excess of planned debt reduction to spending increases and/or tax cuts. Prominent big-ticket examples included the approximately $5 billion ($100 billion over five years) in corporate and individual tax cuts in 200001, increases of some $7 billion in 2004-05 to transfers to provinces associated with the 2004 Health Accord, and allocations of $11 billion, $10 billion and $7 billion in 2005-06, 2006-07 and 2007-08 to tax reductions, predominantly to the Goods and Services Tax (GST). Because these measures involved fiscal commitments, they had the effect of reducing future fiscal flexibility.

Despite this approach to allocation decision-making, significant amounts of additional fiscal flexibility emerged too late in the year for the government to allocate – yet another unintended consequence of prudent budgeting. By default, any year-end surplus that results from such unallocated flexibility must be applied to debt reduction.4

The current fiscal planning framework has caused a number of serious problems with regard to the budgetary process:

This paper is based on an analysis of fiscal data from a period of economic expansion and surplus budgeting. This raises the issue of the extent to which its conclusions are relevant considering the recent move to recession and planned deficits. Even if prudent budgeting practices continue, will the different economic and fiscal circumstances cause a reduction in implicit prudence levels? The final section of the paper suggests that they may not. The focus remains on single-year budgetary balance targets, which continue to be highly sensitive to relatively small variances in revenue and expenditure outcomes. Current economic uncertainties only serve to increase that volatility and, along with it, the risk of missing singleyear targets. Given the mounting criticism of the government’s fiscal forecasts, it might want to decrease that risk and so the need for prudence will increase. Therefore the consequences of prudent budget planning and its attendant implicit prudence are likely to remain with us.

Whether or not this proves to be the case, crises frequently provide an opportunity to make worthwhile changes that would otherwise be difficult to bring about. Looking to the future and a return to more balanced budgets, this paper suggests two complementary changes that would help to preserve the merits of prudent budget planning while attenuating the risks.

The data used throughout the paper are taken from three documents produced regularly by the Department of Finance: annual budgets, fall updates and annual financial reports.5 Appendix A provides some detail on these data, terminological issues related to debt and spending, and structural adjustments that have been made to the way these data are typically displayed by the Department of Finance.6

Government budget officers tend to be prudent by nature. In that sense, prudent budget planning is more of a philosophy underpinning the work of central budget agencies than a particular budgeting process, formula or practice. What sets Canada apart from other countries is the fact that the ChreÌtien (Liberal) government that took power in 1993 adopted prudent budget planning as a principal element of its approach to budget development and decision-making as well as to its budget communication strategy.7 When the Harper (Conservative) government won office in 2006, it made no mention of “prudent” in communicating its approach to budget planning. However, as this paper shows, the basic elements of the prudent budget planning framework that had evolved under Liberal governments remained largely intact and apparent changes were more terminological than substantive. The Conservatives continued the Liberals’ fiscal stance of spending all the fiscal flexibility available after setting aside a target amount for debt reduction. As would be expected, in allocating that flexibility, the Conservatives favoured tax cuts over program spending. In that respect, they continued the trend set by the Liberals toward the end of their mandate, although the Conservatives were willing to make reductions in the GST a significant part of their allocation strategy. Where the Harper government differed more significantly from its Liberal predecessor was in the apparently greater fiscal risk it was prepared to take in applying what amounted to the same prudent budget planning framework. The explicit prudence factors were progressively reduced below levels that had been established by the Liberals, initially by choice but more recently by necessity. However, evidence of similar amounts of implicit prudence within the fiscal framework remains.

Charles Dickens encapsulated two of the key principles that characterize the federal government’s approach to prudent budget planning in the advice that he had Mr. Micawber give to David Copperfield:

Annual income, twenty pounds; annual expenditure, nineteen nineteen six; result, happiness. Annual income, twenty pounds; annual expenditure, twenty pounds ought and six; result, misery. The blossom is blighted, the leaf is withered, the God of day goes down upon the dreary scene, and – and, in short, you are for ever floored… (Dickens n.d., 164)

The first parallel is with the government’s focus on annual budget performance targets instead of on multi-year aggregates. The second is with the high priority the incoming Liberal government gave to reducing Canada’s debt load, putting a history of persistent annual budgetary deficits on a track to balanced-or-better budgets (Liberal Party of Canada 1993). This somewhat atypical pre-election political priority was made possible by a conjunction of public and political opinion that supported the ensuing initiatives and was reinforced by economic events in the early years of the Liberals’ mandate (see Courchene 2002, 2006, for an analysis of how this fiscal story developed over the Liberals’ period in office). The Conservative government continued to prioritize debt reduction.

Annual deficit reduction targets contained in successive Liberal budgets established clear budgetary performance benchmarks. And, as if these alone were insufficient, the Liberal finance minister’s publicly stated commitment to meet those targets “come hell or high water” accentuated the prospect of Dickensian misery should they not be met. The scene for prudent budget planning was set. A further benchmark was established in 1997-98 when the government achieved Canada’s first budgetary surplus since 1969-70, a benchmark that Mr. Micawber would have applauded. This achievement upped the ante on the degree of misery to be suffered should the government lapse back into deficit in any subsequent year. Achievement of that surplus marked a political point of no return and had the effect of introducing an unwritten no-deficit budget rule, at least until the onset of the current economic crisis.

The Liberal government introduced an explicit approach to prudent budget planning as the principal means of managing the risks associated with the high stakes set by its deficit reduction commitments, based on the following parameters:

Although these parameters did not change, the manner in which they were applied and disclosed did evolve. Prudent budget planning became established through consistent and repeated application of the parameters, rather than through any legislated rules. The Liberal government provided a comprehensive summary of what could be considered the final evolutionary step in its 2001 update (Finance Canada 2001, 49-51).

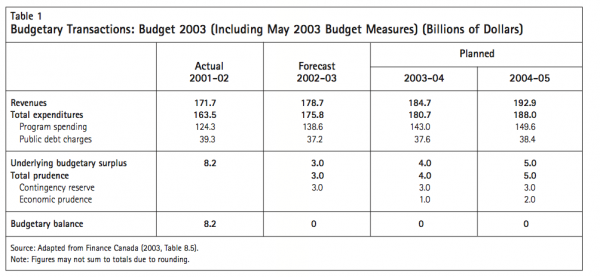

Table 1 shows the fiscal framework contained in Budget 2003 as an illustration of the outcome of the Liberal government’s approach to prudent budget planning. This table reveals a number of typical features:

• Two prudence factors:

• A budgetary balance of zero after the prudence factors have been subtracted in both the current year and the two forward budget years, indicating a budgetary stance of allocating all fiscal flexibility in excess of the contingency reserve to new spending.9

• A surplus in the previous year (2001-02) that significantly exceeds the typical $3 billion in planned debt reduction (the contingency reserve established for that year). In this example, the $8.2-billion surplus consists of $3 billion in planned debt reduction and an unplanned surplus of $5.2 billion.

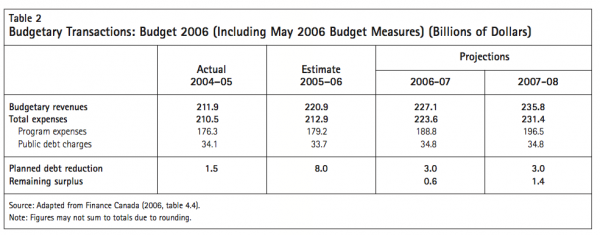

Table 2 shows the equivalent display in Budget 2006, the first budget of the newly elected Conservative government. Although neither this table nor the text of the Budget makes any reference to prudence factors or prudent budget planning, there is little practical difference in the fiscal structure. Only the terminology has changed. “Planned debt reduction” is equivalent to the Liberal government’s “contingency reserve” – even down to the $3 billion set aside for that purpose. Similarly, the “remaining surplus” is equivalent to “economic prudence” in that it represents unallocated fiscal flexibility that, for planning purposes, is available as a cushion should fiscal forecasts turn out to be optimistic; otherwise it becomes available for in-year allocation.

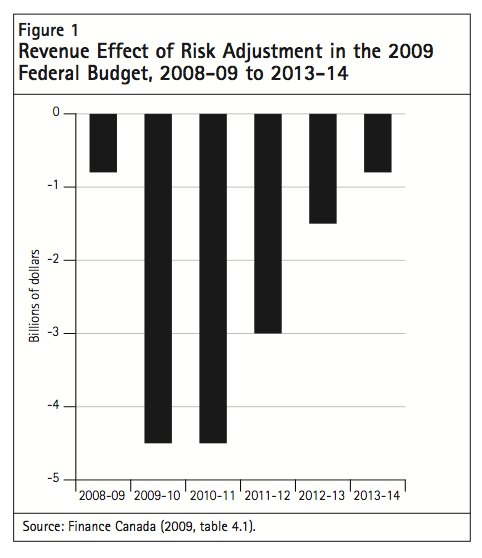

The same fiscal structure was employed in the two subsequent budgets. Only the relative amounts changed. In Budget 2007, “planned debt reduction” remained at $3 billion in each of the two forward years, but the unallocated “remaining surplus” was significantly lower, at $0.3 billion and zero, respectively. In Budget 2008, “planned debt reduction” was significantly reduced, to $2.3 billion and $1.3 billion, respectively, with no equivalent to economic prudence – that is, there was no “remaining surplus.” With a deficit budget balance target in Budget 2009, debt reduction was no longer available as a prudence factor. Instead, the government adjusted downward the average private-sector GDP forecasts, with the effect of introducing the explicit prudence factors presented in figure 1.

The Conservative government’s willingness to reduce the size of these prudence factors in its 2007 and 2008 budgets, and to reduce them in the out years in its most recent budget, indicates that it has been prepared to take a more fiscally risky stance than the previous Liberal government — and the Conservatives have certainly shown no less inclination than the Liberals to fully allocate all available fiscal flexibility to new spending measures after planned debt reduction. There is, however, clear evidence under both regimes that base revenue and spending forecasts contain material amounts of implicit prudence, which serve to significantly diminish the apparent degree of fiscal risk taken by both governments.

The next section explores evidence of implicit prudence as a factor in explaining persistent fiscal overperformance.

Four factors combine to form a compelling incentive for those managing the budget development process to adopt additional risk management measures, over and above the explicit prudence factors incorporated into the fiscal framework.

The first of these factors is the government’s focus on the budgetary balance as the primary measure of fiscal performance. This measure is the arithmetic difference between two much larger revenue and expense numbers. Small swings in either revenue on expense outcomes or both have a disproportionately large impact on the budgetary balance. For example, a revenue result that comes in 1 percent above the budget forecast would have the effect of increasing the budgetary balance outcome by some $2 billion above the target set out in the budget. This makes the budgetary balance a highly volatile performance measure.

The second factor is that fiscal performance is measured in separate single-year outcomes, not as a multi-year average. This single-year benchmark effectively removes the option of using a more statistical approach to setting and reporting on fiscal performance. A multi-year measure would allow for the offsetting of underperformance in one year by overperformance in another and therefore would attenuate the volatility inherent in the single-year budgetary balance measure. This approach would make unfavourable deviations from the target in a single year acceptable. As a result, risk management would be shifted away from a one-sided approach focused solely on eliminating the risk of an unfavourable outcome. Consequently, significantly less prudence would be required for an equivalent degree of risk protection.10

The third factor relates to the size of the explicit prudence factors that are the primary means of managing the risk of incurring a deficit. In a study commissioned by the Department of Finance, O’Neill (2005) indicates that an annual prudence factor in the range of $7 billion to $9 billion would be needed to avoid a single-year deficit. The upper range is over twice the $4 billion in prudence that became the norm in most years. Both the leading private-sector forecasters involved in developing the initial fiscal framework for budget planning and Finance officials would have been well aware that this standard $4billion prudence provided an inadequate cushion against the risk of a deficit outcome.

A fourth and defining factor was Paul Martin’s “come hell or high water” commitment to meet or exceed his fiscal targets. Such an emphatic and repeated public commitment raised the stakes in what was already a high-risk game. The decision by Moody’s early in 1995 to put the federal government on a “credit watch” served to further entrench risk-averse behaviour by those involved in developing and managing the fiscal framework. It is no surprise that the government’s expenditure management system, in combination with the factors discussed above, resulted in an exceedingly low tolerance for the risk of failure to meet the primary fiscal target. The 1997-98 surplus — the first since 1969-70 — arrived well ahead of schedule. That outcome not only lent momentum to the government’s approach to budget planning, but also resulted in zero political and public tolerance for a deficit situation, at least until the onset of the current economic crisis.

Examination of the fiscal framework reveals clear evidence that implicit prudence was a factor in persistent fiscal overperformance over the 1997-2008 period. Publicly available data allow for the testing of four components of the fiscal framework: revenues, public debt charges, major statutory spending forecasts and direct program spending estimates.11

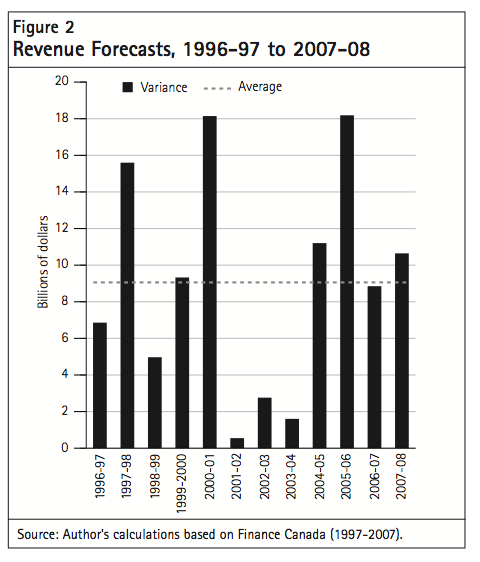

Figure 2 shows that the variance between actual revenue outcomes and budget forecasts was positive in each of 11 years (i.e., base revenues were underforecast each year), strongly suggesting the presence of additional implicit prudence within these forecasts. In his thorough examination of forecasting accuracy, O’Neill (2005) distinguishes between economic forecasts and the process by which they are used to generate revenue forecasts. He notes that, while “economic forecasts have not been particularly accurate…the errors have not persistently been in one direction or the other” (2005, 6; emphasis added). In summarizing the results of three methods used to estimate the impact of economic forecast inaccuracies, he concludes that “economic forecast inaccuracies have, on occasion, contributed significantly to forecast differences for total revenues, but a considerable portion of those differences remain to be explained” (2005, 67). In other words, private-sector forecasts show no systematic errors that would indicate that firms are introducing prudence factors into their forecasts. This strongly suggests that implicit prudence factors must have been introduced during the process of translating these private-sector forecasts into the fiscal framework used for budget planning.

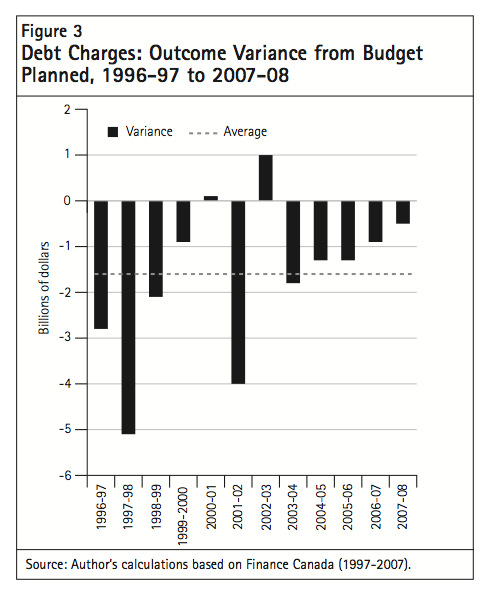

Figure 3 shows a similarly clear pattern of overforecast debt charges contributing to budget overperformance. The Department of Finance’s practice of introducing implicit prudence in forecasting debt charges, through an upward adjustment to the interest rate forecast, became apparent when the government declared that it was ending the practice in Budget 2000 (Finance Canada 2000, 56).

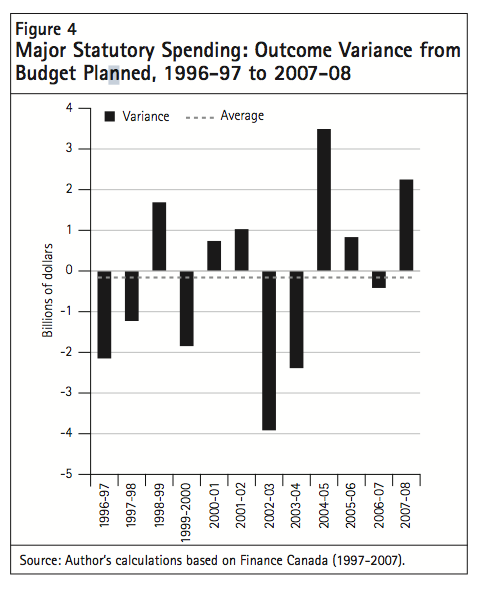

Major statutory spending consists of the government’s major transfer payment programs: to provinces and territories for health and other social programs, for equalization and for infrastructure; and to individuals for elderly benefits, child benefits and employment insurance benefits. A common characteristic of these programs is that the level of spending is established in legislation, usually based on a formula and in most cases based on economic and demographic variables. Thus, planned expenditure levels for the programs are derived from forecasts of those variables. Actual expenditure outcomes are outside government control, at least in the short run, as expenditure levels can be varied only by amending the constituent legislation for the programs to modify the formulae they contain. As shown in figure 4, there is little evidence of any systematic bias, with a roughly equal distribution, both in incidence and in magnitude, of positive and negative variances. The lack of any evidence for implicit prudence in this spending category may well be the result of the formulaic basis of the planned spending forecasts and the relatively even “scatter” of the forecast versus actual variance of the economic and demographic variables on which they are based.

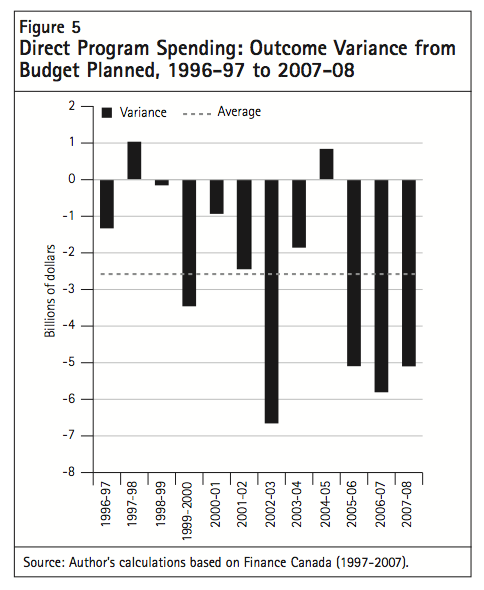

Figure 5 shows a clear pattern of direct program underspending relative to the provisions made in the fiscal framework, with only two years showing a positive variance.

In terms of the way the government categorizes spending in its annual budgets, direct program spending is the residual spending category, after debt charges and major statutory spending.

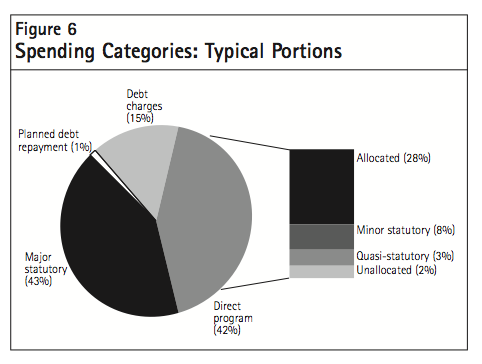

As shown in figure 6, direct program spending can be divided into four subcategories:

With the exception of the minor statutory and unallocated subcategories, direct program spending levels are not so much forecast as establshed as an upper control limit by a decision of the Treasury Board. In the absence of any centrally driven expenditure reduction or reallocation exercise, the budget rule for setting the greater part of the direct program spending base is to take the level established in the previous year and add to it any new, subsequently approved policy funding. In effect, for the major part of their spending, departments receive no compensation for inflation.

On the surface, this approach indicates that the scope for adding implicit prudence is significantly less than the levels implied in figure 5. The repetitiveness and predictability of these direct program funding levels suggest that departments should be able to manage their programs so that their spending outcomes are close to the levels allocated. Some systematic negative variance might be expected because of the serious consequences for departments that exceed their approved spending levels. Risk-averse behaviour might cause departments to persistently underspend their expenditure authorities, and the aggregate of these safety margins might then produce a relatively constant annual negative variance. However, two factors limit the impact of this factor.

Departments are allowed to carry forward to the next year up to 5 percent of any unexpended part of their operating budget. Experience shows that the aggregate total of operating budget lapses each year is roughly equal to the additional funding allocated in respect of the previous year’s underspending — that is, the two balance each other out. The second factor, as noted above for the unallocated subcategory, is that an allowance for the broader aggregate lapse in departmental spending (i.e., over and above the operating budget base) is included in the fiscal framework. Any persistent negative variance from these broader lapses is thus greatly diminished, if not eliminated.

Consequently, the scope for implicit prudence is more likely to exist within the following components of the direct spending base, to which this “same as last year” rule does not apply:

While there may be limited scope for implicit prudence within each of these components, the natural prudence of the central budget officers who establish the amounts and manage their allocation has a cumulative effect. The wider scope for implicit prudence within the minor statutory as compared to the major statutory category could be a result of the larger number of actors involved in major statutory forecasting: the departments concerned and, within Finance and the

Treasury Board, the sectors responsible for oversight of these departments as well as the central sectors responsible for budget planning. It might just be that the interaction between the large number of officials from different organizations inhibits each from adding implicit prudence.

In light of clear evidence that implicit prudence is a persistent component of revenue, debt charges and direct program spending, it is reasonable to ask why the more logical approach of increasing the explicit prudence factors included in each budget is not taken. One possible reason is that a significant portion of this implicit prudence is not added by any single actor in the budget office but has multiple sources, some of which might be invisible to the budget officers responsible for constructing the fiscal framework. Since the source of implicit prudence is beyond the control of these budget officers, there is no guarantee that a decision to increase explicit prudence will cause an offsetting decrease in implicit prudence. In any case, such a reduction would not be immediate. A more credible explanation, perhaps, is that budget officers are comfortable with the degree of risk protection offered by this particular set of implicit prudence factors and therefore are quite willing to retain them.

More generally, there is an inherent conflict between the desire to increase explicit prudence and the political demand for new spending. Increasing the prudence factors established in the framework implies that less fiscal flexibility is available for new spending. With annual new spending demands greatly exceeding available flexibility, it has become very difficult politically to increase explicit prudence factors. Budget officers would need to manage the resultant risk by introducing their own implicit prudence and maintaining any prudence that already exists.

The Liberal government introduced a specific approach to prudent budget planning with the principal objective of creating the fiscal discipline needed to eliminate annual deficits en route to the longer-term objective of reducing the federal government’s stock of debt. Prudent budget planning, although not the only factor in achieving those objectives, was a significant one. However, it also resulted in other, less desirable outcomes. This section focuses on two of those outcomes. One was the emergence of persistent fiscal overperformance, which showed up as annual surpluses significantly in excess of those planned. The second was a shift away from annual budgets as the focal point for allocation decisions and toward a process of in-year allocation decision-making.

The budgetary balance for the first year of any individual budget has become the single most important fiscal performance target set by the government. One reason for this is the fact that the measure has compelling communication virtues. It can be readily and intuitively grasped (at least in concept) by a nontechnical audience, and the target level of performance can be expressed as a single, unequivocal number against which to compare an outcome verified by the auditor general in the public accounts. A second and directly related reason is that a communication focus on this measure was consistent with the Liberal government’s priority of eliminating annual budgetary deficits. “Balanced-or-better” outcomes became a budgetary refrain.

Figure 7 shows the amounts by which budgetary balance outcomes exceeded the targets set in each year’s budget. On its own, this measure shows an exceptional level of fiscal performance, with only one year (2004-05) indicating what might be considered a material negative variance — moreover, that particular variance resulted primarily from adjustments to the accrual basis used to derive the numbers rather than from any fiscal performance factors.

Why has fiscal overperformance developed into such a persistent characteristic of prudent budget planning? One explanation is the fact that the economy has outperformed forecasts (see Courchene 2002, 2006, for an examination of this aspect of fiscal performance). Another is the arithmetic result of the implicit prudence shown in the previous section. Revenues have been systematically underforecast and spending systematically overforecast. The result has been a systemic conservatism in fiscal forecasting over and above economic variability.12

An inevitable consequence of excessive prudence is that material amounts of fiscal flexibility emerge as each year unfolds. Decisions on the allocation of this additional flexibility to new spending may be made throughout the year, although they are typically disclosed in two distinct publications other than the original budget: the fall update and the budget for the next fiscal year. Any flexibility that is deliberately left unallocated or that emerges too late in the year to be allocated to new spending is automatically applied to debt reduction.

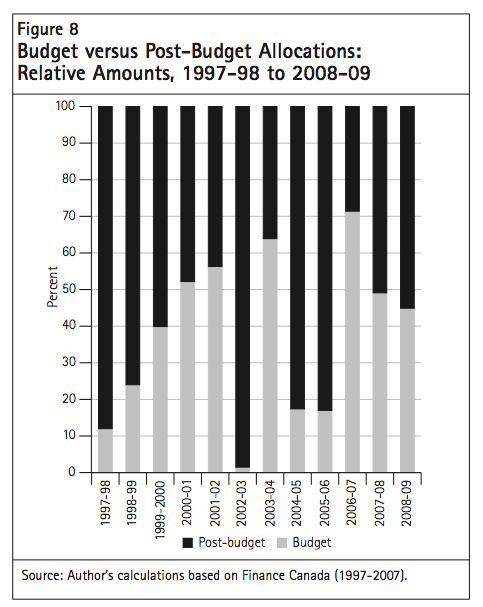

Figure 8 compares allocations made in year to those made during the annual budget decisionmaking process.13 The patterns shown in this chart lead to a number of observations:

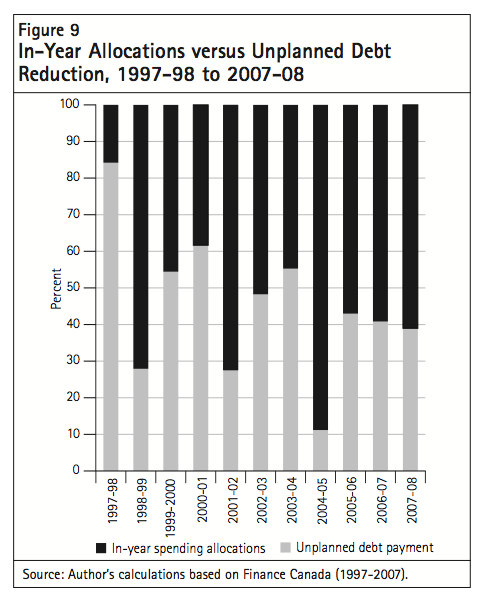

Figure 9 shows how the total amount of additional flexibility that emerges each year is divided between new spending measures and additional debt reduction (over and above planned debt reduction represented by the annual contingency reserve). While there are considerable variations between years, the chart indicates a trend that increasingly favours new spending relative to debt reduction. A possible explanation for this trend is that, with experience, governments become better at managing in-year spending decisions to consume the additional flexibility that they know will inevitably emerge during the course of the year.

Of greater significance, however, is the fact that these additional amounts of debt reduction have been unplanned. In aggregate over the period shown, 47 percent of all the in-year fiscal flexibility that emerged did so after forecasts were updated at the end of the year — too late to be allocated to spending. Application of these amounts to debt reduction did not result from any conscious allocation decision, but was simply a consequence of the accounting treatment of the surpluses.

The Liberals were clearly operating to an unwritten budget rule that emerging flexibility was to be spent and that planned debt reduction was to be limited to the amount set aside as a contingency reserve. This is evident from the fact that, after annual deficits were eliminated in 1997, budgetary balance targets were set at zero both at the start and, more significantly, at the end of each fiscal year in all years but 2000-01. The same is essentially true for the Conservative government: the final forecast surplus was reduced to zero in 2006-07 and 2007-08.

A budgetary policy of allocating a significant portion of the surpluses that emerge throughout the year to debt reduction may even have found support among spenders able to take a long-term view. Every additional $1-billion reduction in debt creates an ongoing stream of additional fiscal flexibility, worth about $55 million annually, that would have become available for potentially more useful allocation decisions than the one-time, in-year spending necessitated by the allocation of emergent surpluses to in-year spending. But the politics of the situation demanded more immediate spending action. Budget planners were facing increasing criticism over such large and recurrent unplanned surpluses. The criticism was all the more pointed given both the perception and the reality that excessive prudence was constraining new spending decisions in annual budgets. The artificiality of that constraint is examined in the next section.

When measured against its primary objective of achieving the budgetary balance target set in each successive budget “come hell or high water,” prudent budget planning has been an unquestionable success in creating the discipline needed to turn a history of persistent annual deficits into annual surpluses. However, as we have seen, the practice has resulted in a number of less desirable outcomes. Those outcomes in turn have the potential to diminish the effectiveness of budget decision-making. The very success of prudent budget planning in achieving its primary objective may have served to decrease its effectiveness as a more general expenditure management tool. This section examines four risks inherent in prudent budget planning: constraints on the range of allocation options available, decreased credibility of the budget guardians and reduced fiscal discipline, reduced process transparency, and reduced capacity to reallocate resources.

Maintaining the discipline necessary to produce planned or better fiscal results is only one objective of budgeting. Another is the effectiveness with which available resources are allocated (Schick 2001). The fact that a government is meeting or exceeding its fiscal targets says little about the effectiveness of how resource allocation decisions are made. The quality of the process of developing new policy proposals is an important factor in the effectiveness of expenditure decision-making. More critical factors still are the government’s fiscal capacity for new policy initiatives and how it makes decisions on the allocation of available fiscal flexibility among competing priorities.

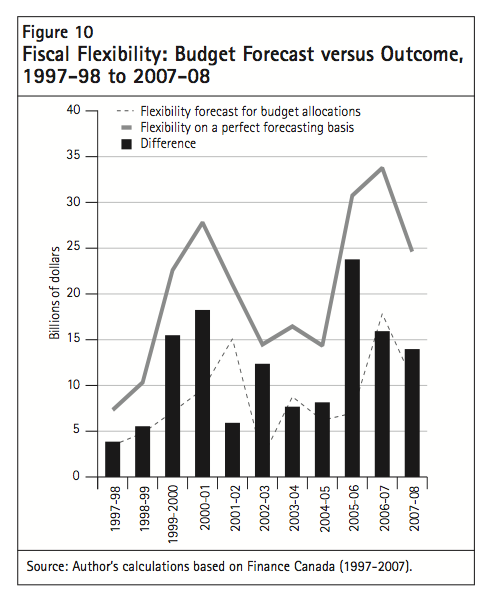

The structural inevitability of fiscal overperformance during the period under study and how it translated into in-year spending decisions were demonstrated in earlier sections of this paper. But these same outcomes had the effect of unnecessarily constraining the scope and range of the expenditure management options available to the government. This effect can be seen in figure 10, which compares the forecast amount of fiscal flexibility available for allocation in the annual decision-making process with a hindsight view of the actual amount of flexibility available based on year-end outcomes.

The lower line shows the amount of flexibility that was forecast as available for allocation in the budget for each year. The upper line shows the amount of flexibility that would have been available had the fiscal forecast been accurate at budget time. The bars show the difference between the “perfectly accurate forecast” benchmark and the forecasts on which budget allocation decisions were made. They provide a measure of the impact that fiscal forecast inaccuracy has had on budget allocation decisions.

Although this is a hypothetical benchmark, based as it is on a retrospective, perfectly accurate fiscal forecast, it nevertheless demonstrates the degree to which budget allocation decisions have been constrained by the overly prudent forecasts on which they are based. The average difference between the perfect forecasting benchmark and the flexibility forecast on which allocation decisions were based amounts to $12 billion. The gap is positive in all years, ranging from a low of $4 billion to a high of $24 billion. What this illustrates is that even relatively small improvements in the all-important forecasting of fiscal flexibility on which annual budget allocation decisions are based would materially increase the range of allocation decisions that could be included in the budgetary process.16

The issue here is that the range of options available to the government in dealing with the additional flexibility that emerges over the course of each year is much more restricted than it would have been had the flexibility been available as part of the budget decision-making process. There are two reasons for this. The first is that a significant portion of the flexibility is concentrated in the year in which it emerges. As each year progresses, an increasing number of forecasts turn into “actuals.” While forecasts may be refined, the implicit prudence they contain remains largely intact and is revealed as additional fiscal flexibility. But this flexibility does not carry over into succeeding years. As a result, policy options that require multi-year or continuing funds are effectively eliminated from consideration.

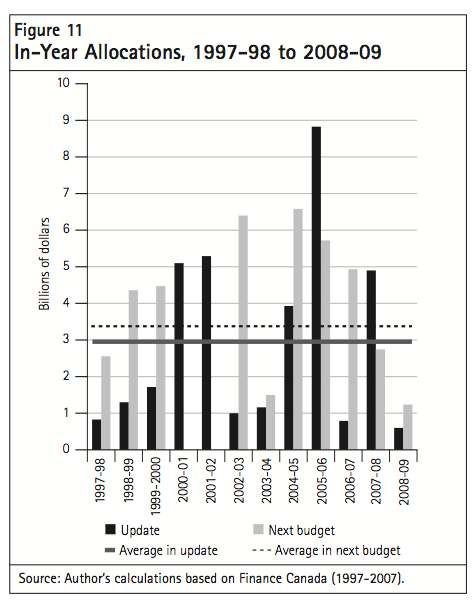

The second reason is that material amounts of this additional flexibility do not become apparent until late in the year. The fact that this additional flexibility is measured in billions of dollars limits the extent to which it can be allocated to departmental program spending. As illustrated in figure 11, the amount of additional flexibility shown as allocated in fall updates averaged $3 billion, with a further $3.4 billion on average shown as allocated in budgets for the next fiscal year.17 Departments have limited capacity to spend any large increases to their budgets that arrive that late in the fiscal year — sensibly or not!

The combined consequence of these two factors is that the government is limited to three options for allocating the additional fiscal flexibility that emerges in year. It can transfer funds outside the government accounting entity, deliver one-time tax cuts or reduce debt. The third option is in fact the automatic consequence of not using the first or the second. Both Liberal and Conservative governments have made extensive use of the first option through payments to foundations and trusts, although the Conservatives removed foundations as an option in announcing that these entities would be consolidated within the Accounts of Canada (Finance Canada 2006, 57-58). In the period 1996-97 to 200304, the Liberal government transferred more than $9 billion to foundations (Auditor General of Canada 2005), although use of this mechanism declined in tandem with the auditor general’s increasing criticism of the practice.18

Payments to trusts have been used primarily as additional federal transfers to the provinces. The Conservatives used this mechanism to allocate a total of $5 billion in their first two budgets. The trust mechanism has the dual advantage of freeing both levels of government from the accounting constraint requiring that unexpensed funds be lapsed and applied to debt reduction. Funds transferred by the federal government are recognized as an expense in the year in which they are transferred and hence achieve the purpose of “spending” the additional fiscal flexibility that has emerged. But the provincial governments do not have to draw down funds from these trusts until they wish to make an expenditure, and thus do not have to accept federal funds in an accounting period during which they are not needed.

Figure 9 shows the extent to which unplanned budgetary surpluses that governments were unable to spend have been allocated to debt reduction; in dollar terms, these come to a total of $112 billion over the period 1997-98 to 2007-08. The amount was unplanned in the sense that both the Liberal and the Conservative governments were operating to a “spend all the fiscal flexibility” rule. These payments, over and above the planned debt repayments, represent the fiscal flexibility that emerged after the final set of allocations was made toward the end of each year. By default, any subsequent fiscal flexibility that emerges automatically reduces the debt.

Significant fiscal overperformance has been a hallmark of prudent budget planning since its introduction in 1994. When the deficit corner was turned in 1997, fiscal overperformance achieved even greater prominence with the emergence annually of billiondollar unplanned surpluses. In the eyes of many if not most stakeholders, the credibility of the fiscal framework on which expenditure management decisions are based was put in doubt. To say that a loss of credibility poses a risk to fiscal discipline is to state the obvious. The fiscal framework provides the basis for fiscal discipline in expenditure management decisions, whether they are made in developing annual budgets or throughout the year. If the spenders in government come to expect that the central budget office’s estimates of flexibility available for new spending will be unnecessarily conservative, then the job of those guardians in fending off spending pressures becomes increasingly difficult.

The same credibility issue can be found at the political level. The prime minister and the finance minister face similar difficulties in resisting spending pressures — from within the cabinet as well as from a wide range of lobbies outside the government. Credibility issues flowing from prudent budget planning are also factors in cabinet cohesion, which itself can affect fiscal discipline. The prime minister must be able to manage the political risks in a process that inevitably produces real and perceived winners and losers. The weaker the cohesion within the cabinet (or the weaker the prime minister’s control), the greater the temptation to minimize the degree to which individual ministers are actual or perceived losers. A real or perceived position of weakness will increase pressure on the fiscal framework and so pose a risk to fiscal discipline.

There is a parallel here with a credibility issue that was a factor in the demise of the Program and Expenditure Management System. PEMS, as it was known, was an approach to expenditure management put in place in 1980 with the overall objective of linking expenditures more closely with priorities. One of its features was an attempt to introduce reallocative discipline into the policy decision-making process. New policy decisions that could be only partially afforded within the policy funding envelopes established as part of PEMS had to be funded through reallocation — or so the concept went. These policy envelopes were set at a level that was insufficient to meet the demand for new policy funding, in an attempt to force reallocation across the programs within each policy envelope. The affordability limits set by the size of the policy envelopes lacked credibility, and ministers were able to mount successful end runs around PEMS by appealing directly to the finance minister or the prime minister for funding, and thus avoiding the need for reallocation. The success of these end runs reinforced the low credibility of the policy envelopes as realistic upper limits for new spending and was a key factor in the system’s eventual demise.19

Persistent surpluses also called the government’s credibility into question on the issue of tax levels in a way that is quite separate from the damage they inflicted on the credibility of the fiscal framework. This aspect of tax policy has nothing to do with economic arguments, but arises from continuing debate over federal-provincial fiscal balance and federal tax levels. Material, recurrent budgetary surpluses have been cited as clear evidence that the federal government is raising more revenue than it needs to discharge its responsibilities. For example, a report commissioned by the Council of the Federation defines the vertical fiscal imbalance problem by stating unequivocally that “for almost a decade the federal government has been running budgetary surpluses and has been spending significantly in areas that the Constitution of Canada assigned to the provinces. The federal government has more money than it requires to discharge the functions for which it is responsible.” (Advisory Panel on Fiscal Imbalance 2006, 9) When coupled with complaints that the federal government’s use of foundations as a means of implementing new policy represents an intrusion into provincial jurisdiction, such criticisms also served to bring the government’s fiscal credibility into question.

The Conservative government’s reduction of GST rates could be seen as a response to this pressure. An alternative view is simply that the government had the fiscal flexibility to allocate, that it was following the same “spend all the fiscal flexibility” rule that its Liberal predecessors had followed but had an ideological preference for spending that flexibility on tax cuts rather than on new programs. In this case, the creation of “tax room” that the provinces could occupy would be a secondary effect of the decision rather than a direct response to provincial pressure. Arguably, the federal government’s choice of the GST was based on a consideration of which tax instrument would have the most immediate public impact, rather than on the tax areas where provinces would prefer to increase their occupation.

As discussed in the previous section, fiscal overperformance is a structurally inevitable outcome of prudent budget planning. But fiscal overperformance is not unequivocally an indicator of excess revenue capacity. If even a portion of the additional flexibility that emerged in the succeeding years had been available for allocation in annual budgets, the government would have had the option of allocating it to new spending. Surpluses would have been much lower and new spending allocations might have been directed toward programs more clearly in the federal domain, where there is significant demand, such as in defence and Aboriginal programs.

The point is that this aspect of the vertical fiscal imbalance debate would be more productively pursued in terms of the appropriate bounds of federal spending rather than through sterile assertions that surprise surpluses demonstrate excess federal revenue-raising capacity. The latter claim is an easy one for proponents of the imbalance argument to make. It is also one that the federal government has difficulty defending credibly in the public domain.

The gradual emergence of significant additional flexibility throughout the year also has the effect of shifting the locus of expenditure management decision-making away from the annual budgetary process and toward a continuous, year-round process, as indicated in figure 8.

In practical terms, the concept of annual budgeting is more a question of degree than an absolute.20 While even a tendency toward the annual end of the budgeting spectrum may not be the sine qua non of a systematic process, it is difficult to conceive of a disciplined expenditure management process that is not framed by a regular timetable and some degree of transparency – if not publicly then at least within the government. The marked shift toward the continuous end of the budgeting spectrum brought about by prudent budget planning has reinforced the tendency toward centralized decision-making. Canada’s expenditure management system is quite explicit in stating that the prime minister and the finance minister are responsible and accountable for budget decisions (Treasury Board of Canada 1995, 10), and the decreased role played by cabinet and cabinet committees in the budget development process is well known.21 The apparent process regularity of allocation decision-making in a regular cycle of budgets, updates and “next” budgets is misleading, as many of the allocation decisions disclosed in the latter two documents are confirmation of earlier decisions. While budget decision-making is not necessarily the most transparent of government exercises, there exists at least a broad knowledge of the main process elements and the roles played by the principal actors. A more ad hoc process would have few if any regular process elements. The result will be less transparency. The consequence will be much less opportunity for intervention, internally within government as well as by Parliament and the public.22

Although prudent budget planning has continued to be effective in controlling fiscal aggregates and, until the recent economic crisis, preventing any return to deficit budgeting, it has become increasingly ineffective in exerting the discipline necessary to reduce spending below levels consistent with a balanced budget target. Prudent budget planning has done little to limit growth in spending. Furthermore, the expectation that flexibility will inevitably emerge throughout the course of the year has served to transform decision-making from an annual budget development process into a year-round exercise. Spending up to a level that allows for no more than the planned annual $3-billion debt reduction payment has become the fiscal planning norm.23 In any rational model of budgeting, reallocation would be expected to play a part.

The federal government has a long history of reallocation initiatives. The 1970s and 1980s were characterized by frequent cutting exercises known as X-budgets that came to follow a regular pattern. Central agencies proposed rationally derived cut options. Political consensus on the differential impact of these rational proposals proved impossible to achieve, often because of the short span of time within which decisions had to be made. That led to an eventual default decision to make equal percentage cuts across the board. Motivated primarily by fiscal stress, these X-budgets were mechanically successful in achieving a minimum degree of expenditure reduction, to limit the size of annual deficits that persisted during the period. Attempts at more rational approaches to expenditure reduction during the period, such as PEMS in 1979, the Neilson Task Force in 1984 and the Expenditure Review Committee in 1989, were universally unsuccessful in terms of their reallocation objectives.

In contrast, the Liberal government’s Program Review initiative was successful on two reallocation fronts: as an instrument of expenditure reduction; and, for the first time with such a major and farreaching exercise, achieving differential rather than across-the-board cuts.24 Some departments were cut more severely than others, and few direct spending programs were exempt from cuts altogether. Broad public and political acceptance of the need to decrease spending in order to reduce the deficit was a key enabler of the Program Review’s success (Kroeger 1998). Three motives for reallocation – fiscal stress, good management and new policy spending pressures – combined to give the Program Review that broadbased support (Kraan and Kelly 2005).

Even with the elimination of annual deficits, and thus the removal of fiscal stress as a motivational factor, the two other motives for reallocation remained. In the face of vocal advocacy for smaller government, or at least slower growth in government spending, the government fell under continual pressure to come up with a reallocation encore. As a result, reallocation came to be firmly established as a budgetary goal and was the subject of a number of further initiatives.25 None of these initiatives, however, came close to achieving the success of the Program Review. Ironically, it was the very success of the Program Review that removed the main precondition for expenditure reduction success: fiscal stress. Without that reason for reallocation, other reasons proved inadequate to bring about the consensus and political will needed to repeat the Program Review’s reallocative success.

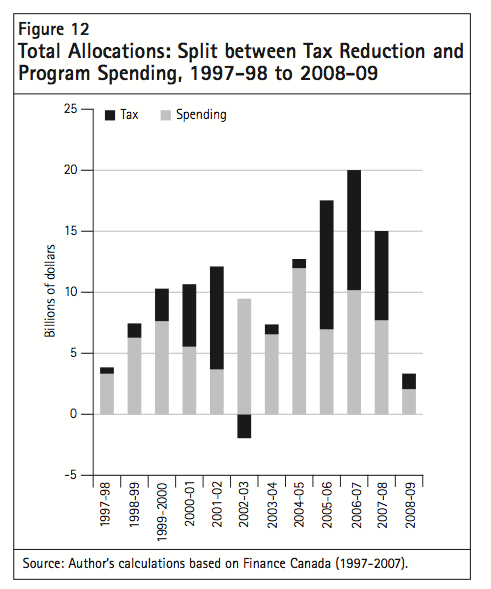

Nonetheless, the need for reallocation remained, even if it appeared less compelling in times of fiscal abundance. Growth in program spending would at least be reduced to the extent that tax reductions were favoured over new program spending. But, as indicated in figure 12, within a “spend all the fiscal flexibility” approach to allocation decisions, both Liberal and Conservative governments continued to allocate relatively large portions to program spending.

Should there be any real political desire to reduce the rate of growth in program spending once the recession is behind us, it is unlikely that curtailing allocations to new program spending will be accept able as the primary contributor. Cuts to the existing program base would have to make a significant contribution. However, a fiscal environment in which the emergence of additional flexibility is seen as inevitable represents a major impediment to the fostering of the broad-based public, bureaucratic and political will needed to make the intrinsically difficult decision to cut existing programs.

The preceding discussion suggests that prudent budget planning will have to undergo some adjustments or risk losing its effectiveness as an expenditure management tool. This section discusses two changes that could significantly reduce that risk.

Whatever targets are singled out by a government as the basis for fiscal accountability, other targets will usually be evident from the data presented in various budget documents. However, few would argue that the budgetary balance should not feature prominently as a performance measure for public and parliamentary accountability. As we have seen, this measure has a number of compelling communication virtues. It can be readily and intuitively grasped (at least in concept) by a nontechnical audience. Moreover, a target level of performance can be expressed as a single, unequivocal number against which to compare a verifiable outcome. The budgetary balance is, however, a volatile performance measure because of its sensitivity to minor variances in either revenue or expenditure results. When the focus is on the balance for a single year, that volatility is exacerbated.

The other measure that both Liberal and Conservative governments have communicated as a fiscal target is the ratio of debt to GDP. This measure has a number of advantages over the budgetary balance. Because it is a medium-term target, annual outcomes are put in the less volatile context of past and projected progress along a track. Another advantage is that it brings the more fundamental issue of debt level into focus, thus providing a context and rationale for the annual budgetary balance target. The reality, however, is that debt/GDP as a performance measure has received little media or parliamentary attention. One possible reason for this is that the performance of debt/GDP has simply been overshadowed by media attention on the more controversial nature of budgetary balance overperformance. Another is that it is a less appealing measure for a nontechnical audience, although this drawback could be overcome with some media attention leading to greater familiarity. Finally, governments may be reluctant to give prominence to a target such as debt/GDP for which there is little consensus on a desirable or optimal level.

Revenue and expenditure forecasts will always generate annual uncertainty, and this is something that budget planners will have to deal with. But if their errors are neutral, these forecasts should produce an aggregate zero error over a sufficiently long period. If the budgetary balance target is established as an aggregate over a multi-year period, shortfalls in one year can be made up by tightening discipline in succeeding years. Conversely, overperformance in one year would permit fiscal relaxation in succeeding years.

A multi-year target would permit a reduction in the size of the annual prudence factor in order to achieve the same degree of risk protection. As we have seen, there are two reasons for this. One is that the risk is spread over a longer period. The other is that risk management is shifted away from a one-sided approach focused solely on eliminating the risk of an unfavourable outcome and toward a two-sided approach with variations in both directions around an aggregate target. Smaller prudence factors, in turn, translate into greater fiscal flexibility available for allocation decisions, and thereby reduce fiscal overperformance. In addition to diminishing variability, this approach would shift the balance of new spending decision-making into the annual budget development process and serve to reduce in-year decisions.

Two factors have to be taken into account in considering such a change. One of these is the communication challenge. Were the government to shift from an annual “balanced-or-better” budget target to a multi-year target, it would be abandoning what has become a publicly understood and accepted norm. Although the current recession has rendered deficits acceptable, once a recovery takes hold, this no-deficit norm will no doubt regain its prominence. The government would then have to counter the inevitable criticism that it is softening a target that constituted a principal element of fiscal discipline. This suggests that there is at least conceptual truth to the argument that government might take advantage of a year when performance is better than planned by increasing spending but might feel politically constrained in making the tough expenditure reduction decisions that will be necessary should the risk of fiscal underperformance become reality. By the same token, the shift from recession to recovery would provide a perfect opportunity to change the public mindset.

In addition, the media, and particularly the opposition parties, might simply ignore the multi-year basis for accountability to which the government is committed and focus instead on the single-year planning numbers still contained in budget documents and reports — especially if these provide better fodder for question period. That negative dynamic was evident in the media’s focus on “surprise surpluses” during the Liberal government’s mandate, instead of on updates to future-year forecasts where differences from previous forecasts were smaller.26 And it persists in today’s economic and fiscal environment, but with an interesting twist. Now that planned budgetary balances have shifted to deficit — and because of informed criticism that the government forecast of a return to budgetary balance is optimistic — media attention has also shifted, to encompass future years, where the cumulative total provides a more dramatic number.27

The second factor in considering this approach is the length of the multi-year period in which an accountability commitment to an aggregate budgetary balance target would be made. O’Neill (2005) suggests that the period should be the economic cycle. A practical difficulty with this approach, as O’Neill acknowledges, is that it is virtually impossible to determine the length of a cycle prospectively. Robson (2006) reaches similar conclusions in his study on prudent budget planning but suggests a probabilistic approach that does not rely on “point forecasts that are certain to be wrong” (9). In Robson’s approach, the government would establish a spending growth rate consistent with what it considers an acceptable risk of running a deficit. That in turn would result in planned surpluses with analytical backing and would, Robson suggests, allow the government to communicate ahead of time the uncertain nature of these budgetary outcomes (in a manner similar to that used by the Bank of Canada around its inflation targets). Communication issues with the general public and parliamentarians would be key factors to take into account when considering this approach.

Should there be any desire to adopt a multi-year target, a simpler approach might be possible — one that avoids the risk of getting bogged down in technical considerations. This would be to set a multiyear budgetary balance target over a short but arbitrary period related to the political cycle. An obvious option would be the four-year period between elections, now that legislation to put elections on a fixed schedule has been enacted.28

A measure that would facilitate expenditure risk management, either on its own or as a counterpart to a multi-year budget target, would be the capacity to carry forward unplanned surpluses to future years. A simple analogy might be that of a family choosing to put any money they have on hand at the end of the year into a savings account and postponing the decision whether to spend the money or to use it to pay down their mortgage. While there is nothing preventing the government from putting its year-end surplus into the conceptual equivalent of a savings account, the accounting principles that it currently follows are counterintuitive and would result in another communication challenge.

In accounting terms, the government’s deposit of any part of its year-end surplus into such an account would not be recorded as an expense. Consequently, the public accounts would not show any reduction to the surplus for that year. The expense would in fact not be recorded until the government decided to draw down funds from the account and spend them. If that “withdrawal” occurred in a tight fiscal year, the logical circumstance in which additional funds would be needed, this accounting treatment could have the perverse effect of forcing the government to record a deficit for the year in which it withdrew funds. The more logical explanation by the government, based on the family analogy (i.e., maintaining a balanced budget by dipping into its savings fund), is thus apparently contradicted by the numbers that will eventually be shown in the public accounts.

A number of provincial governments (including Alberta, Manitoba and Quebec) use “fiscal stabilization” accounts and appear prepared to deal with that potential accounting complication.29 The federal government, possibly because of the communication concern around the potential situation described above, has taken different approaches. In concert with its 2005 update, the Liberal government introduced Bill C-67, which would have authorized the allocation of “unanticipated surpluses” in equal shares to tax cuts, program spending and debt reduction. Those allocations would have been made after any surplus in excess of the $3-billion contingency reserve had been identified in the public accounts. The legislation would have applied over a time-limited period, 2005-06 to 2009-10. As the Bill died on the Order Paper with the November 2005 election call, its accounting treatment and the manner in which its application would have been communicated are a matter of speculation.

After signalling in Budget 2006 that it would consider allocating unanticipated surpluses to the Canada Pension Plan and the Quebec Pension Plan, the Conservative government took a different approach. It included the Tax Back Guarantee Act in its 2007 Budget legislation (Finance Canada 2006, 147; Finance Canada 2007, 156; Budget Implementation Act 2007). This legislation authorizes the government to reduce personal income tax by the amount that debt reduction reduces debt interest charges. This measure amounts to a pre-allocation of future year fiscal flexibility, and thus is an indirect and marginal means of carrying forward unplanned year-end surpluses.

The point being made here is that the application of accounting principles suited to a private sector environment can have a perverse effect in the environment in which governments operate. The federal government has had to resort to convoluted alternatives to the straightforward approach of carrying forward year-end surpluses. The way in which these accounting principles are applied constrains an option that could materially improve the government’s way of making expenditure management decisions, and thus constrains budget policy.

A useful challenge for the accounting community would be to look at how current accounting principles might be adapted so as to remove this constraint. Why, for example, is it considered unacceptable in accounting terms for the federal government to transfer surplus funds to the equivalent of a trust fund, outside the government accounting entity, from which it could draw down funds in the future? What would be the consequences of adjusting the accounting rules that prevent this treatment? Would those consequences be sufficiently grave to outweigh the benefits for the government? It seems ironic that external trusts can be used to transfer funds to the provinces such that both levels of government incur the associated expenses and revenues in years when they do not artificially distort fiscal outcomes, yet an external trust cannot be used in that way for the benefit of the federal government.

One consequence of the current economic crisis has been the government’s return to deficit budgeting in a fiscal planning environment that is markedly different from that which prevailed throughout the major part of the period under study. This raises the question of the extent to which the above findings are affected by the current situation, as we enter a period characterized by economic uncertainty and a fiscal plan that forecasts four years of deficit outcomes.

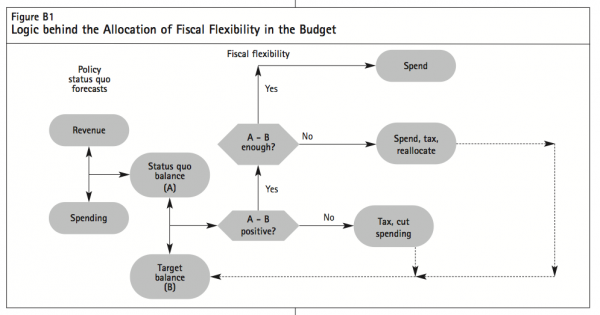

Most of the factors that underpin the arguments made in this paper are not affected by adverse economic conditions or deficit budgeting. The fiscal arithmetic that frames allocation decisions remains the same. Fiscal flexibility is still calculated by subtracting the target budgetary balance from that calculated on a policy status quo basis. The only difference is that the status quo balance is now a negative number. If the government decides to set a target budgetary balance that increases the deficit, there will be fiscal flexibility to allocate. If it decides to set that target at a lower level of deficit, then it will have to cut spending, increase revenue or do both.30 But the fact remains: whatever single-year target is set, it will still be highly vulnerable to relatively small variations in revenue and expenditure outcomes. Furthermore, in uncertain economic times, revenue and expenditure variability is likely to be greater and may well increase the volatility of that target. Consequently, the incentive for implicit prudence factors to reduce the risk of an unfavourable budgetary balance outcome will remain. The issue then becomes one of whether the political tolerance for that risk has increased.

During the Liberal government’s years in office, a significant driver of risk aversion was Paul Martin’s “come hell or high water” commitment to meet his targets as finance minister. Although the Conservative government has been willing to take greater fiscal risks, the analysis in this paper does not signal a trend toward reduction of implicit prudence since the Conservatives’ rise to power. On the one hand, an argument can be made that this government is just as sensitive as its predecessor to an unfavourable budgetary balance outcome variance and therefore just as risk averse. For example, the current government has faced sustained criticism on a number of fronts: its post-election change in position regarding a return to deficit budgeting; its unrealistically optimistic fiscal forecasts in the 2008 fall update; and similar optimism in Budget 2009’s forecast of a return to surplus by 2013-14. With its credibility under siege, the government is unlikely to accept any significant increase in the risk of missing its budget targets. On the other hand, the media and the public, if not the opposition parties, may be accepting of an unfavourable (but slight) variance from a budgetary balance target that is a deficit as opposed to a balanced budget. All things considered, however, political aversion to unfavourable variances in a single-year, budgetary balance target is unlikely to disappear, which suggests that the levels of implicit prudence are unlikely to deviate from those of the past.

As we have seen, refocusing budget targets as an aggregate over a multi-year period significantly lowers the potential for outcome volatility. In order to encompass a planned return to a “balanced-or-better” fiscal outcome, Budget 2009 shifted its focus toward targets over a multi-year period, although not toward an aggregate. Coupled with the inevitability of continued annual deficit outcomes in the short term, that shift could provide the basis for moving to and establishing an aggregate as the fiscal anchor. Outcome volatility would decrease, and the incentive to retain implicit prudence would decrease along with it. The current environment could also provide an opportunity to pursue capacity to carry forward future surpluses. Such capacity would serve as a volatility reduction complement to an aggregate target and allow for the allocation of the excess fiscal flexibility to something other than deficit reduction. The government should take action to plan for this if — or when — surpluses return.

However, even if there is movement in that direction, the opposition parties are likely to maintain a focus on annual measures, particularly if the government misses the annual numbers that would still be contained within a medium-term budget framework. In that respect, there is a short-term consequence of the admirable requirement for quarterly fiscal accountability reports that the government has agreed to provide: they might serve to keep the media and public focus on annual performance and to delay acceptance of any multi-year aggregate target.

Capacity to reallocate resources is another area in which the current situation could change the dynamics. As we have seen, fiscal stress is a key factor in creating the political will necessary for successful reallocation. Although fiscal stress is with us once again, its impact could be blunted if implicit prudence is not reduced and if fiscal overperformance continues. Even in an era of deficit budgeting, in-year flexibility would continue to emerge. Whether the government decided to spend this additional flexibility or to allocate it to debt reduction, the emergence of additional flexibility would weaken the credibility of calls for reallocation — as would, for that matter, any weakening of the resolve to return to “balanced-or-better” budgets.

Prudent budget planning, as practised by the Canadian federal government over the past 15 years, has been a highly successful tool of fiscal discipline. It has been a major factor in eliminating annual deficits and therefore in putting Canada on an accelerated track to achieving the target debt/GDP ratios that have been set. Notwithstanding changes to terminology and display, the Conservative government has embraced most elements of the prudent budget planning framework inherited from its Liberal predecessors.

However, the way in which prudent budget planning has been practised has created an incentive for budget officers to manage the political risk of missing annual budget targets by retaining or introducing implicit prudence into the fiscal framework. That has resulted in two unintended and undesirable outcomes: persistent and material fiscal overperformance, and a consequential increase in both the size and the incidence of in-year allocation decisions to spend the resultant surpluses.

These outcomes pose a number of risks to the effectiveness of the government’s expenditure management process. First, the overall effectiveness of expenditure management is reduced because the range of allocation options available to the government is artificially constrained. The constraint occurs either because the full amount of fiscal flexibility available is not apparent when annual budget decisions are made, or because a significant portion of that additional flexibility does not emerge until it is too late to allocate to departmental spending and a further portion does not emerge until it is too late to allocate at all. Second, the credibility of central budget officials, and of the prime minister and the finance minister, is jeopardized, making their fiscal guardianship role more difficult. Third, the shift toward a more continuous process of decision-making has increased the tendency of the Westminster system to centralize power. The transparency of the budget process is reduced as a result. Fourth, the government’s capacity to reallocate resources is impaired, largely because of the difficulty, in the face of persistent unplanned surpluses, of creating and maintaining the political will needed to eliminate or scale back existing programs that may no longer be effective.

Two remedies that would attenuate these risks are discussed in this paper. The first is to move from a single-year budget target to one that is expressed as a cumulative total over a multi-year period. Of political necessity, Budget 2009 has tried to shift the focus from single-year to multi-year targets, and this change could be consolidated and incorporated into the planning framework. The four-year election cycle recently established by legislation would provide an appropriate length for that multi-year period while respecting political realities, but governments would have to respect the intent of the law.

The second remedy — in the context of lessons learned from the unintended consequences of prudent budgeting — is to modify accounting rules that constrain surpluses from being carried forward. Currently, any part of a surplus carried forward or placed in a notional “savings account” does not produce a reduction in the size of the reported surplus. Furthermore, any future use of surplus funds carried forward in this way could have the perverse effect of causing an “accounting” deficit to be reported in the year in which the funds are used. This is a clear case of accounting rules obstructing sound budget policy.

Barack Obama’s chief of staff recently quipped, “We shouldn’t let a good crisis go to waste.” The reality of short-term deficits (which has lifted a 10-year taboo) provides an opportunity to revisit budget planning processes with the twin goals of a return to budget balance (once the recession is over), and prudent and effective budget allocations over the long term.

This paper is an updated version of a paper presented at the Association of Budgeting and Financial Management’s 20th Annual Conference in 2008 and was Web-published in the Queen’s University School of Policy Studies’ working paper series. The author would like to thank David Good, Sharon Sutherland, Jim Quinn and a number of former government colleagues for their comments on earlier versions of this paper. Thanks are also due to Tom Courchene and Jeremy Leonard for their comments on more recent versions. The author is, however, responsible for the way these comments have been taken into account.

Advisory Panel on Fiscal Imbalance. 2006. “Reconciling the Irreconcilable: Addressing Canada’s Fiscal Imbalance.” Ottawa: The Council of the Federation. Accessed May 27, 2009. https://www.councilofthefederation.ca/ pdfs/Report_Fiscalim_Mar3106.pdf

Alberta Finance and Enterprise. 2008. Budget 2008 Fiscal Plan. Edmonton: Government of Alberta. Accessed May 27, 2009. https://www.finance.alberta.ca/ publications/budget/budget2008/pdf.html

Aucoin, Peter. 2003. “Independent Foundations, Public Money and Public Accountability: Whither Ministerial Responsibility as Democratic Governance?” Canadian Public Administration 46 (1): 1-26.