A democratic deficit can manifest itself in a number of symptoms, such as low voter turnout, low participation in political parties, and declining trust in political leadership and democratic institutions. Another less recognized symptom of a democratic deficit is a gap between a population’s preferences and the actions governments take, resulting in governments’ inability to deliver on the results the population desires.

Many solutions have been proposed to cure this deficit, such as electoral reforms or increasing the political knowledge of young Canadians, but most of these solutions would be difficult to implement and would take considerable time to produce benefits. One thing that all the proponents of these solutions would agree on is that increased and more meaningful public involvement would improve discourse, expand dialogue and engage people in the decision-making processes of our democratic institutions.

In this study Joseph Peters and Manon Abud (Ascentum Inc.) start by making the case that Canada is in a state of democratic deficit, and then they propose e-consultation as a way to mitigate this deficit by increasing public involvement in democratic processes. While they admit that it is not a panacea for our democratic challenges, they demonstrate that it is an emerging approach and a tangible way for Canadian democratic institutions to make better decisions through an engaged public.

The authors define e-consultation as the use of information and communications technologies to involve different publics through different forms of interaction with democratic institutions. Among other benefits, they say, it could increase civic literacy and allow the public to be engaged in discourse and dialogue, thus addressing key symptoms of the democratic deficit, including closing the gap between expectations and what is actually delivered.

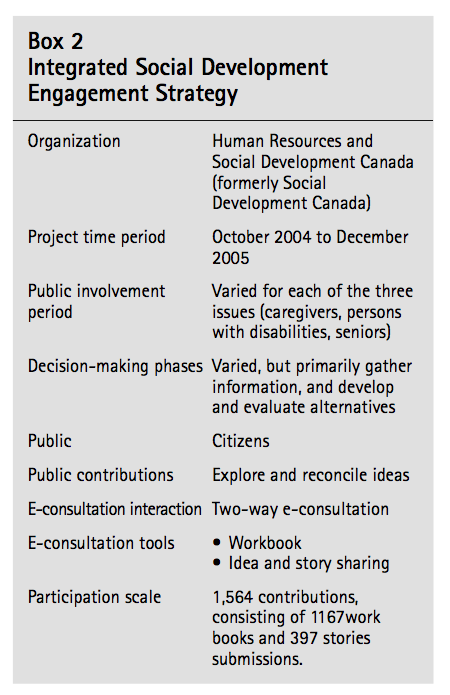

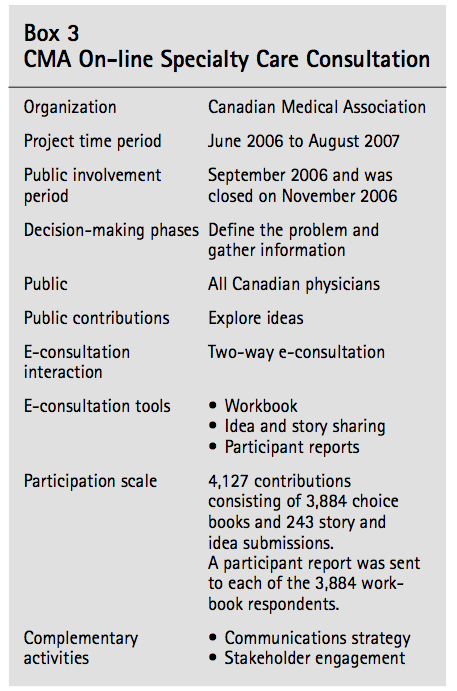

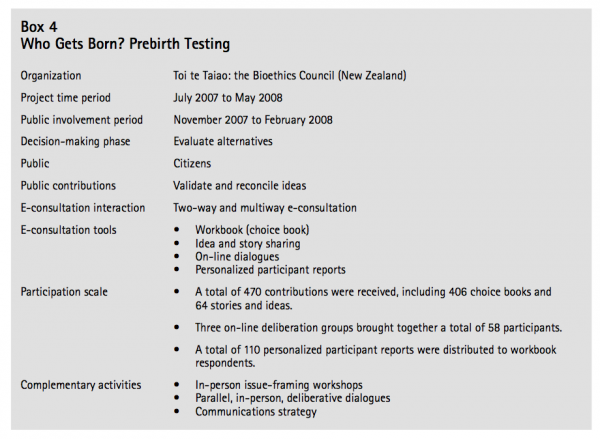

Peters and Abud then present some practical applications of e-consultation through several case studies. The first is in a parliamentary context: an e-consultation on mental health undertaken by the Senate of Canada. The second is a public administration consultation undertaken by Social Development Canada on priority issues such as care giving, child care, seniors, persons with disabilities and communities. The third is from the voluntary sector, the Canadian Medical Association’s e-consultation with its membership on specialty care. The final example comes from outside the Canadian context, but provides a model to aspire to. It is an e-consultation initiative undertaken by the Government of New Zealand on prebirth testing. For each example the authors discuss strategic concerns, the approach that they took, their findings, the challenges and what they learned in the process.

Based on the information presented in the case studies and their experience with public involvement and e-consultation, the authors make several policy recommendations for those involved in democratic governance and intending to conduct on-line consultations. These recommendations include the need to:

They emphasize that on its own e-consultation can not address the democratic deficit. However, they argue that public involvement is a key part of a new model of democratic governance. With time, resources and commitment, meaningful e-consultation could facilitate a shift in public perspectives and renew the public’s belief, trust and interest in our democratic institutions.

Two commentators provide academic and practitioner perspectives. Kathleen McNutt (University of Regina) agrees with the authors that e-consultation has the potential to facilitate democratic dialogue and be an effective tool in overcoming citizen’s discontent with modern democratic institutions. However, she challenges the idea that it can successfully contribute to an increase in public trust without a binding commitment from governments to incorporate into policy development the feedback they receive through the consultations. According to McNutt, without substantial changes to the process of valuing public input, citizens’ perception of government responsiveness will remain unchanged. Colin McKay (Privacy Commissionner of Canada) also agrees with Peters’ and Abud’s diagnosis of the problem and the use of e-consultation to increase public involvement in democracies. He describes some of the main challenges of the process, drawing an important distinction between stakeholder consultations and broader public engagements. He also points to some interesting examples of the latter in the United Kingdom and the United States, for instance, its use by Barack Obama in his electoral campaign. He stresses that whether on-line engagement can be translated into the policy development process, which he sees as one of the greatest tests of e-consultation, remains to be seen.

Canada exists in a state of democratic discontent or deficit. There is ample evidence to illustrate that trust, respect and the perceived relevance of our democratic institutions are in question. Change is beginning to take place. While not the panacea to our democratic challenges, public involvement through e-consultation approaches may be a piece of the complex solution to reducing apathy, increasing trust and establishing a new relationship with Canadians. E-consultations facilitate getting beyond the “usual suspects” by expanding perspectives and enriching the sources of input into democratic decision-making processes.

E-consultation successes abound in the Canadian context, but are not often documented or celebrated. This study aims to explore e-consultation from various perspectives: definitions, tools, examples and best practices. The authors’ objective is to present the strengths and weaknesses of e-consultation in theory and practice, but also to provide evidence of this position as a valuable, if not essential, part of a new era of democratic governance.1 To that end, this study

E-consultation is an emerging approach and a tangible opportunity for Canadian democratic institutions to make better decisions through an engaged public.

Raymond Williams provides an enduring perspective of democratic governance in Culture and Society: 1780-1950, published in 1958. In today’s context it is still relevant and in retrospect prophetic: “If people cannot have official democracy, they will have unofficial democracy, in any of its possible forms, from the armed revolt, through ‘unofficial’ strikes or restrictions of labour, to the quietest but most alarming form — a general sullenness and withdrawal of interest” (315).

This warning resonates with more relevance today than it did 50 years ago. Given the context of societal change in which Raymond was writing, he presents the idea that a withdrawal of interest is worse than armed revolts and protest. Such events call the health of democracy into question. If one considers the decline in voter participation over the past several decades in Canada as a proxy for withdrawal of interest, then by Raymond’s definition the health of our democracy is in question.

Canada cannot claim ownership of the term “democratic deficit” — British parliamentarian William Dunn asserts that he was the first to coin the phrase. He used “democratic deficit” to characterize the distance and disconnect between the European Union and the citizens of its member countries (Newton Dunn 1988). In Canada, this term has been fodder for opposition parties and occasionally ruminated on by those in government. Consecutive governments at the federal level have had cabinet positions with responsibility for democratic renewal. By this action alone, one might conclude that there must indeed be a deficit or that something is wrong with democracy if it is in need of renewal.

From a definitional standpoint, there are a couple of schools of thought on what the democratic deficit is. Most of the literature focuses on the decline in attitudes, action, engagement and civic literacy relative to previous eras. The most popular symptoms are low voter turnout, lower participation in political parties, and declining trust in political leadership and democratic institutions (see Howe and Northrup 2000; Pammet and LeDuc 2003; Institute on Governance 2005; Milan 2005; EKOS 2006; Milner 2007). Another perspective centres on the idea that there is a gap between the preferences of a population and the action taken. This deficit is more about an inability to deliver on the results a population desires (see Pilon 2001; Conrad 2003; Rebick 2001; Axworthy 2004; Heath n.d.). The definition of the population can shift in this perspective from just those interested in or affected by certain policies to the general population. The common definitions of “democratic deficit” in the Canadian literature thus focus either on a relative decline in participation and trust or on a preference gap in decision-making. Evidence of the decline is abundant, but evidence of the preference gap is more subtle and nuanced.

The overall trend in voter turnout has been declining since the Second World War, with three major drops in 1953, 1974 and 1980. Recently, the decline has been more steady and prolonged, and Canada has come to an interesting crossroads in voter turnout: in the past four elections, the number of Canadians who were eligible to vote and did not was larger than the number who voted for the winning party. Younger cohorts are also less likely to vote and do not view doing so either as essential or a part of their civic duty (see O’Neill 2001; Pammet and LeDuc 2003; Milan 2005; Milner 2007).

Data show that trust in political leadership has been in decline since the 1960s. Overall interest and participation in political parties have also followed a steady decline. This picture is augmented by a 16 percent decrease between 1998 and 2006 in the number of Canadians who say they discuss politics and political affairs with family and friends (EKOS 2006). A number of studies also point to a decline in public deliberation. Nevitte’s and Axworthy’s evidence points to a decline in the interest in and function of political parties (see, for example, Nevitte 1996; Axworthy 2004).

Deliberation is also hampered by the media’s superficial coverage of political actors and issues, especially when combined with the concentration or consolidation of power within the media (Nadeau and Giasson 2005). Paquet argues that citizens are frustrated by the slow and disjointed response of governance to an increasingly dynamic and pluralistic environment, and that the deficit is related to governance structures and decision-making (1999). Research also shows that there is a gap between how much people want to be involved and how much they feel that they are involved in decision-making and governance (EKOS 2006).

The solutions are not as clear as the evidence, which should not come as a surprise. The potential solutions are complex to implement, and it could take considerable time to see their benefits. An exploration of several recommended courses of action points to interesting conclusions.

The most common prescriptions and attempts to solve the democratic deficit have been manifested in changes to the voting system. At the provincial level, we have seen attempts to move to proportional representation in British Columbia, Ontario, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island over the past several years. The idea with this solution is that the value of a vote changes with proportional representation, so that electors will be more likely to cast their votes if they feel their participation has yielded a greater degree of efficacy or tangible results of their participation.

Both O’Neill and Milner point to youth as the solution. O’Neill notes the need to promote the importance of voting among young Canadians (2001); at best, however, this would solve only the votingturnout challenge of the democratic deficit. Milner’s focus, instead, is on increasing the political knowledge of young Canadians — a course of action that might affect more elements of the deficit, though it likely would take generations to make a difference (2007).

Axworthy argues that the deficit should be addressed by changing the role of political parties, which need to have an increased responsibility for public discourse (2004). This is consistent with another solution that calls for leadership and political will to address the democratic deficit (Institute on Governance 2005). A significant challenge lies in the power of the status quo. It has been too good, historically, for the two major political parties in Canada to suggest that either would support or accept significant change to the current system.

O’Neill also points to a different discourse than that of Axworthy, suggesting that change can take place through an increased dialogue with Canadians (2001). Paquet agrees to an extent, but prescribes subsidiarity and citizen-based evaluation and feedback in decision-making.2 In his opinion, this would ensure legitimacy and responsiveness in governance. Dialogue and mechanisms to allow an engaged citizenry are seen as two potential solutions to the democratic deficit (Paquet 1999).

These are just a few of the potential courses of action for relieving the democratic deficit. The comprehensive exploration of this current state of affairs and its potential solutions would warrant another study in and of itself. Regardless of the precise diagnosis and symptoms of our democratic illness, we must consider opportunities to address our state of disengagement through a shift to new forms of democratic governance. Based on the exploration of several proposed solutions, there is a clear role for an increase in meaningful public involvement. This would improve the discourse, increase the dialogue and engage the public in the decision-making processes of our democratic institutions.

Democratic governance is much broader than public involvement, which is just one of many different ways to contribute to democratic governance. E-consultation, in turn, is merely a form of public involvement that takes place over a different medium: the Internet. We propose the definition that e-consultation is the use of information and communications technologies (ICTs) to involve the public (citizens and/or stakeholders) through different forms of interaction with our democratic institutions, with the intention to elicit inputs that contribute to more sustainable or robust decisionmaking.

Within public involvement and e-consultation, there is a host of related definitions and terminology to navigate. Citizen engagement, deliberative dialogue, public consultation and public involvement are often used interchangeably. Here, we use “public involvement,” as we believe it is a more inclusive definition, in which the other concepts are subsumed.

E-consultation can address several elements of the democratic deficit. One is the idea of closing the gap between expectations and what is actually delivered. E-consultation can assist in understanding and, where possible, alleviating the gap. Another area is civic literacy: e-consultation can present the different perspectives on an issue and facilitate a deliberative exploration. The final link to the democratic deficit is made through the e-consultation process itself, which allows the public to engage in civic discourse and dialogue.

There are other arguments that support the case for e-consultation. Coleman and Gøtze presented a strong case for e-consultation in their popular piece Bowling Together, in which they argued for mass adoption of e-consultation in the United Kingdom, where the Internet use rate was just 50 percent at the time (2002). Adoption rates have now reached such levels that it is difficult to argue against the ubiquity of the Internet. In Canada, Internet use hovers around 73 percent (Statistics Canada 2008), and the circle of life (youth becoming older) will ensure that this number grows. High-speed or broadband access is still a challenge for rural citizens, but with many e-consultation tools high speed is not a factor, since our public institutions like to work with the lowest common denominator, or a least a lower technological and bandwidth denominator, for the most part.3 Regardless of these other factors, the Internet is a communications medium that a large majority of Canadians are using. Our democratic institutions’ relevance to citizens and stakeholders can come into question if they fail to reach people through this commonly adopted medium.

Internet adoption rates among youth (those ages 16 to 24), at 96 percent, are much higher than among the general public (Statistics Canada 2008). The Internet is the medium of choice for young people today. The challenge for e-consultation hosts is to get through the noise. The question that needs to be asked is: Can government reach 19-year-olds who have YouTube, iTunes and Facebook running simultaneously on their screens? Ironically, the same accessibility standards that aim at allowing low bandwidth and access for persons with disabilities end up excluding youth. It is a breach of those guidelines to engage young people through the many new and emerging technologies they choose to interact with over the Internet.

While it is still evolving, one can safely conclude that the Internet is well established as a communications medium. However, our democratic institutions are still trying to figure out the best means to engage citizens and stakeholders over the Internet. E-consultation is one means. To develop an understanding of e-consultation and public involvement more broadly, we explore several issues. First, we develop a definition of who the “public” is in public involvement.

Second, we examine when and how public involvement can contribute to decision-making and policy development. Third, we look at the different types of interactions that can be initiated between the host and participants through e-consultation. We then make a link to specific e-consultation tools and carry them over to several case studies.

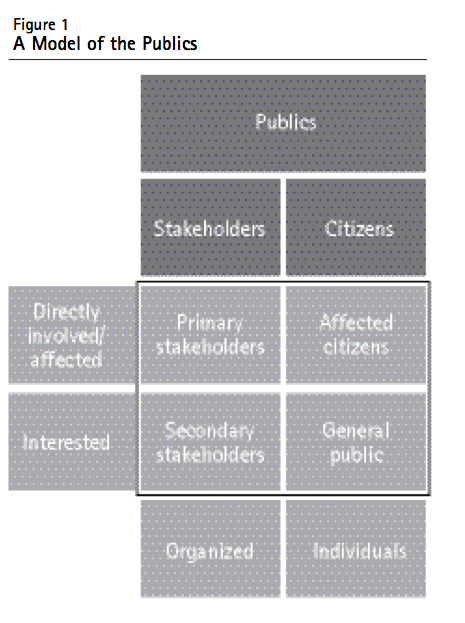

The “public” in public involvement should be seen as the different publics to be engaged. For some initiatives, the publics might be narrowed to target audiences and stakeholders. For others, the publics might include affected citizens, interested parties or even the general population.

As shown in figure 1, this model presents the publics through several important lenses. The first breaks the publics into citizens and stakeholders. The defining difference between stakeholders and citizens from our perspective is that stakeholders are organized entities of some size or scale. Broadly, a stakeholder provides an organized or organizational perspective on an issue, while a citizen provides an individual perspective. (Experts and academics offer exceptions in certain cases: an expert might not be affiliated with an organization, though most are; an academic might provide an individual perspective even though affiliated with an institution.)

The next criterion — that of being directly involved in or affected by an issue — adds a public involvement lens to this model. The idea is that those who are involved or affected should have their perspectives considered at some point in a democratic decision-making process. There is also a spectrum to this criterion: some citizens might be greatly affected, while others might be only marginally affected.

We have seen that stakeholders and experts attempt to convey that they represent the viewpoint of individual members or citizens. We have found this representation to be lacking in democratic fundamentals. It is common for organizations to take the paternalistic view that “we know what is best for our members and those we represent,” rather than presenting the actual results of a broad engagement of those they represent. Our conclusions lead us to the view that citizens and stakeholders who are involved and affected need to be engaged in public involvement and democratic decision-making.

Next comes the criterion of whether or not the publics are interested. This suggests a second tier of the public, but we are not suggesting a two-tiered form of democracy — we believe both tiers need to be engaged. This might take different forms; at a minimum, however, it is essential for the perspectives of those involved in or affected by the issue to be considered.

A common concern in public involvement is the issue of representativeness, recruitment and the sampling approaches that should be used. Some feel that without the use of a random sample, a public involvement initiative is of little use from a research perspective, arguing that results then cannot be generalized or extrapolated but can be considered only the sum of the views of hundreds or thousands of participants.

There is, however, a fundamental flaw to this logic: a random sample can be used in a public involvement initiative, although it might be inappropriate. One can argue that if the consultation is to be public, it might therefore need to be open broadly to the public to participate. We contend that, for many public involvement initiatives, open or self-selected participation is warranted, if not required. If the public involvement is intended to give the interested public an opportunity to offer its perspective, then a closed initiative would be inappropriate and would be seen as “undemocratic” by those with an interest in contributing. This is not to say that broad representation from different interests is not desirable. On the contrary, active communccations efforts are essential to inform and engage diverse and inclusive perspectives.

Another argument to consider is the idea that democracy is active. While all citizens have the right to vote, only those who actively decide to vote contribute. The fact that there is an overrepresentation of seniors and an underrepresentation of youth does not invalidate the results of an election. We argue that it is not contradictory to think that a democratic public involvement initiative should accommodate all those interested in participating.

A major concern is interest group manipulation of the public involvement activity. While a valid concern, in our experience, its likelihood is exaggerated, especially in an e-consultation context. Depending on the approach and the tools used, the potential for interest group manipulation can be kept readily in check.4

Several symptoms of and solutions to the democratic deficit are tied to engaging citizens in decision-making. For public involvement to be considered genuine, it must be able to contribute to the decision-making process. This is not to say that the public should make the ultimate decision, but that its input must be considered and used by those requesting public involvement. A public involvement initiative that is a public relations exercise or a “check box” in the policy development process does more to increase the democratic deficit and the public’s corresponding cynicism and apathy. Even if they have the best of intentions, public involvement initiatives also need to be analytically responsible — poorly designed initiatives that cannot respectfully consider the input received merely increase the democratic deficit, perhaps even more so than initiatives designed as no more than public relations exercises. Asking for input is not enough. There has to be the will and means to use the input if skepticism and cynicism are not to prevail.

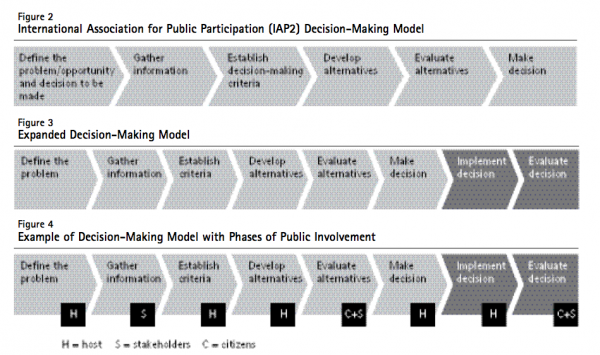

The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) provides training services and organizes conferences for public involvement practitioners around the world. The IAP2 has been successful in creating a common understanding of the principles and tools for public participation. In its training courses, it presents a five-step decision-making model (see figure 2). Our experience has shown, however, that this decision-making model is missing two important postdecision steps that could benefit from public involvement — namely, implementation and evaluation (see figure 3). Engaging stakeholders or citizens in the implementation or evaluation of the decision could have tremendous utility, which the model in figure 2 does not capture.

The IAP2 makes an important observation about the relationship between public involvement and the decision-making model — that public involvement may take place at any step of the decision-making model. The emphasis is on may. Different initiatives require public involvement at different stages; different publics may also participate at different stages, with experts and stakeholders at one stage and the general public at another. The public appreciates the opportunity to contribute as long as its role and the intended use of its contribution are effectively conveyed. Coleman and Gøtze suggest that citizens do not want to govern, they want to be heard (2002).

To help illustrate the potential for different roles, figure 4 presents a model of a fictional decisionmaking sequence, one in which stakeholders, citizens and the democratic institution contribute to different stages of the decision-making process. The model is not a prescription; rather, it is an example of public involvement at different stages in the decisionmaking life cycle. This depiction is helpful in several ways. First, it conveys the point that public involve-

ment does not equate with the devolution of decisionmaking to the public. In most instances, it is about allowing the public to contribute to the formulation of the decision. A referendum is the comparatively rare example of allowing the public to make the final decision regarding a public policy issue. Second, the depiction assists in determining the intent and design of the public involvement. By first understanding the purpose of the input to be requested from the public, the appropriate tools and approach can then be selected. Finally, this model and example attempt to convey the idea that each public involvement exercise is different, and that interactions with the public can and should change on an issue-by-issue basis.

The public can contribute in a variety of different ways to democratic decision-making, including exploring, validating and reconciling ideas (see figure 5 on page 8).

With exploring ideas, the focus is on divergent input and conversations, whereby the public can bring ideas, suggestions, information and perspectives into the decision-making process. The public can also be engaged to validate ideas and allow the decision-maker to check ideas with the on-the-ground perspective. The third contribution that the public can provide relates to reconciliation of diverse ideas. These are more convergent discussions that emphasize trade offs and the weighing of values. Thus, the design and intent of the public involvement initiative can call for exploration, validation and reconciliation. These are not mutually exclusive concepts — this is the rationale for presenting these public contributionsinfigure5asaVenndiagram: onepublic involvement initiative might be designed to explore an issue and validate (or invalidate) options, while another might encompass all three types of input.

This model should not be interpreted as precluding the public from making other contributions. Rather, its intent is to convey the different perspectives and input that public involvement can provide decision-makers.

Leighninger argues that our democratic institutions need to break away from a paternalistic parent-child relationship (2006). Citizens are demanding a change, so a shift to adult-to-adult conversations is required if we are to create a new and meaningful form of democracy. Part of that shift to adult conversations is moving from opinion to deliberation and informed participation. The public needs to be provided with a sense of efficacy — with a sense of how its contributions will be used. This does not imply a devolution of decision-making to the public. On the contrary, the use of the public input must be appropriately scoped and conveyed to participants, as presented in the decision-making models above.

Public involvement approaches try to distance themselves from the top-of-mind opinion that polling and surveys tend to emphasize. For example, the intent of James Fishkin’s Deliberative Poll is present in its name (see Fishkin 1991, 1995, 2000; Fishkin and Laslett 2003). But whether it is a citizen jury, a national issues forum or an on-line workbook, thoughtful consideration or deliberation of the issue is essential.

For informed deliberative public involvement to t a ke place, a baseline of civic literacy around the issue needs to be established. We argue that a deficiency of civic literacy is a key element of the democratic deficit. Most public involvement approaches emphasize balanced background information for participants to consume. This translates into the idea that different perspectives need to be provided to the public to consider if meaningful deliberation — the thoughtful consideration of an issue through the weighing of evidence — is to take place. This might seem counterintuitive, as there then is a requirement to provide information in order to get information (or input). Another way of considering this is that the public involvement host needs to share what it knows, or at least to indicate from where it is starting. In the exploration phase of decision-making, the host might not have much to share. In an evaluation of alternative phases, there should be a base of information on the rationale behind each alternative. This should be provided to the public where at all possible.

Stakeholder organizations and subject matter experts have critical roles in our definition of the public. Their need for information is different than a citizen’s, but not much. Background information from the host can clarify the issue’s starting point or present the host’s perspective. This can help to provide a focus for the public involvement as well as the parameters around the decision to be made. Just assuming that the organized or expert publics know this intuitively does not set up the public involvement initiative for success.

In most public involvement tools and techniques, the notion of deliberation is often construed as a group activity — many equate deliberation with group interaction. We support the argument that the act of deliberating can also be an individual one. Goodin argues that deliberation does not need to be limited to the “external collective” (2003). It is possible for individuals, through an “internal reflective” approach, to engage in internal deliberation and experience informed consideration of an issue. As the jury collectively deliberates the facts presented before it, so does the judge in the privacy of his or her chambers.

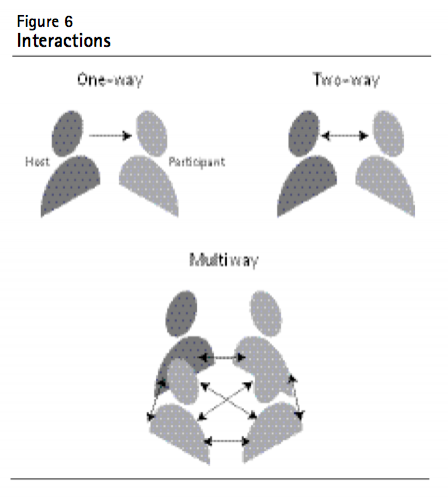

At the foundation of public involvement are the different types of interactions and the flow of information between the host and participants. These can range from the simple to the significantly complex. We argue that, as shown in figure 6, public involvement initiatives encompass one-way, two-way or multiway interactions between the host (black in figures 6 through 10) and participants, whether citizens or stakeholders (grey in figures 6 through 10). Some initiatives might incorporate all three types of interactions, while others might consist of one or two. In this section, we discuss these interactions and provide examples of e-consultation tools that fit the different types.

The one-way broadcast (figure 7) is the simplest form of public involvement, and it is difficult to consider it on its own to be a valid or effective form of involvement. It represents traditional communications that might include the release of a report, a newsletter, a press release or a media event. The primary role of the one-way broadcast is the dissemination of information. With the increasing noise in communications, this type of involvement on its own makes it quite difficult to achieve a significant positive impact. We argue, though, that the one-way broadcast is an essential precursor to more sophisticated involvement activities. Communications are essential to raising awareness of a public involvement opportunity among the intended participants. We have found in our work that this is a critical area, in which many public involvement hosts do not invest enough time or resources.

The opposite of the one-way broadcast is the oneway receipt (figure 8). This would come in the form of unsolicited input — for example, a letter to a minister or member of Parliament. Democratic institutions frequently receive unsolicited input. In certain cases, this type of input is seen as a “trigger” to initiate a public involvement initiative.

From a practical standpoint, two-way interaction (figure 9) is the beginning of active involvement and consultation. The interaction primarily exists in a oneto-one interaction at this level between the host and participants. The host might initiate interactions with a request for input from many participants, but formal interaction among the participants is not part of the intended design. Most of the e-consultations we have participated in had this type of interaction as their starting point.

The workbook is a personally deliberative two-way interaction tool that provides information for a participant to consider before presenting questions. The workbook can be effective in providing baseline information and establishing civic literacy around an issue with participants. The output is primarily quantitative data, although qualitative data can be also collected. The challenge in drafting a workbook is making the conscious effort needed to ensure that the information is balanced and unbiased. In our experience, this can be overcome with a diverse external review panel, not unlike an academic peer review.

Designing a workbook to present a participant with the same tough choices decision-makers face can result in several outcomes. For example, a sense of empathy can be established by creating an understanding of the potential trade-offs in making choices. Finite resources also become a reality when priorities need to be determined. The point is that creating an initiative with tough choices can be a rewarding and engaging initiative from a participant’s perspective.5

Workbooks do not resonate with all types of participants; some will reject a highly structured process with a quantitative foundation. While workbooks facilitate large-scale participation, they often need to be complemented with a qualitative input opportunity.

Storyand idea-sharing tools are on-line qualitative input processes, structured to allow for thorough qualitative analysis. Stories and ideas each have a different intent and focus: a story has an experiential and anecdotal emphasis, while an idea is more actionor solution-oriented. To provide some structure to the input, a choice of themes, topics, issues or challenges can be established so that a participant contributes to a host’s areas of interest.

In our experience, participants value the opportunity to share their stories and ideas with other participants in their preferred fashion. We do not know whether the underlying motivation is the sense of community that is established, the learning from others, Internet voyeurism or the wish of some to see their contribution in black and white on a Web site. Ultimately, the ability to share becomes the prerogative of both the host’s design and the participant’s interest in doing so.6 Story and idea sharing are an effective qualitative complement to the quantitative orientation of a workbook or “choice book.” We have found that with citizen-focused initiatives, there is an emphasis on stories; conversely, stakeholders and experts concentrate more on presenting ideas, suggestions for solutions or actions.

Other two-way interaction tools are also used in e-consultation. One example, though not often used, is online surveys or polls. While they serve a purpose and can be an excellent data-gathering tool, surveys do little to increase civic literacy, enable a public discourse or create the opportunity for deliberation. It should be noted, however, that we do use them for evaluation purposes at the conclusion of an e-consultation.

Another two-way interaction tool that we do not often use in e-consultation, at least for data collection purposes, is the blog — a word derived from “Web log” and a concept not dissimilar to that of a diary: the author posts a message with limitless flexibility (hourly, daily, weekly, occasionally). Most blogs allow their readers to comment on the post. In this sense, a blog might be seen as a two-way or multiway interaction tool, depending on how the comments system is structured. We like blogs, but we see them more as a communications vehicle than as a means of collecting input to contribute to robust decision-making.

Multiway interaction (figure 10) involves a different level of sophistication and complexity. In this model, the public involvement host can initiate interactions with a number of participants. The intent is for the interactions to be not just between the host and individual participants, but among participants as well. Moving from a one-to-one model to a many-tomany form of involvement can result in the host’s losing a degree of control. The host might set boundaries or guidelines for the many-to-many interactions, but the interactions among participants ultimately cannot be accurately predicted or contained. This is a desirable outcome in many situations.

On-line dialogue aims to engage participants in a manner similar to in-person dialogue. It is the idea of exploration, sharing and learning among participants that is a fundamental objective of most initiatives. While deliberative dialogue is a best practice, whether on-line or in traditional forms, not all on-line diaOn-line dialogue can be delivered through various designs and permutations. From a technology standpoint, most government undertakings use a lowest or lower common denominator approach. Video-based dialogue is a reality for some potential participants, but a more general adoption of this technology is challenged by broadband access issues, hardware and software standards. Text-based dialogue, for the most part, is how on-line dialogue operates in a government context.

On-line dialogue can be moderated or unmoderated. We have had more success with moderated events, but with highly motivated participants moderation is not essential. Moderators can provide summaries, keep the conversation going and invite participants to “speak up” or come back to the virtual table. On-line dialogue can also be set up to take place in real time (synchronous) or any time (asynchronous). There are benefits and drawbacks to scheduling, convenience and the time commitment to both approaches, but these are design factors for the host to consider.7

There is often some discussion about the size of the group for an on-line dialogue. From a technological standpoint, there is little difference whether the group has 20, 200 or 2,000 participants. In attempting to adapt the best practices from in-person dialogue to the on-line experience, we have found that 15 to 20 participants around a virtual table have the benefits of small group dialogue — large enough to keep the conversation going, but small enough that everyone can have the opportunity to make a contribution and that information overload is avoided.

In our experience, multiway interaction tools are still in a state of refinement. We have had both excellent and mediocre experiences with on-line dialogue. More research and experimentation are needed before online dialogue is as useful as two-way interaction e-consultation tools.

Discussion boards are almost as old as the Internet itself when one takes into account the context of newsgroups, listserves and e-mail. They allow individuals to visit a site and post on an issue, and the sequence of posts of individuals is referred to as the “thread.” Threads can be structured around themes or topics. A visitor to a discussion board can review different topic threads and make a post.

Discussion boards have become more sophisticated recently, with more intuitive interfaces and higherquality content indexing and searching within threads and posts. Discussion boards are also highly scalable and can easily accommodate large-scale involvement. For a new participant, the challenge sometimes is figuring out where to start and where the conversation has been. On a site with 10,000 posts or even just 500, a sense of information overload is often unavoidable. A moderated discussion board can provide summaries of contributions, although this is rare in practice. Discussion boards can be a rich source of qualitative information, but the lack of structure makes thorough qualitative analysis difficult.

Another tool that has enjoyed a rapid increase in popularity is the wiki. A simplistic definition of a wiki is a Web page that can be edited easily by multiple authors. A wiki usually has the ability to track changes and keep previous versions, and in its basic form is a tool for collaborative authoring. The use of the wiki in e-consultation initiatives is still quite nascent. Wikis are first and foremost a tool for collaboration — they are best applied where there is a pre-existing relationship or working relationship, which is not always the case with a public involvement initiative. (Tapscott and Williams explore mass collaboration in their 2006 work, Wikinomics.)

The best example of where the wiki has worked is Wikipedia. But the broader concept of mass collaboration is the big opportunity for public involvement and e-consultation. Linux or open-source software in general are the great examples of Internet-based mass collaboration. More thinking and experimentation needs to be undertaken to see how these concepts can be applied in a democratic governance and public involvement context.

All sectors of Canadian society — private, public, not for profit — are starting to use or experiment with different types of e-consultation and public involvement tools. With whom they are engaging depends on their perspective. Governments consult with citizens, experts, stakeholders and other governments. Businesses look to involve clients, customers and shareholders. Associations in the third sector might look to involve members or clients. All organizations, especially those of a larger scale, have the opportunity to involve employees in both internal and external issues of importance.8

Since our experience with e-consultation in the public sector has concentrated on the federal level with national institutions, the examples we explore below centre on the federal story. There are, however, several good examples at the provincial and municipal levels. Borins and Brown outline Ontario’s e-consultations on the 2004 budget and a municipal housing initiative (2007), while Culver and Howe, with a look to efficacy and other outcomes of public involvement, explore an on-line budget deficit consultation undertaken by the City of Moncton (2004).

In this section, having covered the arguments for e-consultation, as well as some theoretical and conceptual considerations, we now introduce some practical applications of e-consultation through a series of four case studies in which we were involved as practitioners.9 The first case is from a parliamentary perspective: an e-consultation on mental health embarked upon by the Senate of Canada. The second case is from the public administration perspective: an integrated engagement undertaken by Social Development Canada. The third case is an exploration from the notfor-profit sector: the Canadian Medical Association’s (CMA’s) e-consultation with its membership on specialty care.10 The final example comes from outside the Canadian context, but provides a model to which to aspire: an e-consultation initiative undertaken by the Government of New Zealand on prebirth testing.

All four case studies have a number of points in common. In each instance

It thus can be argued that the main drivers of participation were the participants’ desire to speak out on an issue that directly affected them and the belief that they would be heard.

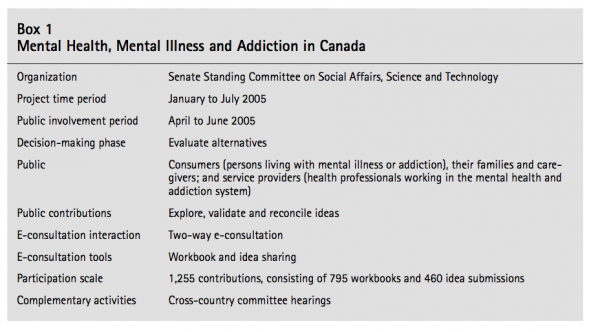

In 2005, the Senate Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, under the leadership of Senator Michael Kirby, undertook a research initiative on the state of mental health, mental illness and addiction in Canada (summarized in box 1). This Senate initiative was built on the foundations of work undertaken in the House of Commons by the Subcommittee on Persons with Disabilities, which launched the first Canadian parliamentary e-consultation in December 2002 (Parliament of Canada 2003). The Senate initiative benefited from the process, technical, analytical, procedural and governance lessons learned by the House.

Senate committees — or parliamentary committees, for that matter — do not often hear testimony from a broad base of individual citizens. Members of the committee identified a need to move beyond the “usual suspects” and speak to “consumers” of mental health and addiction services in Canada. Beyond transparency and inclusivity, the intent was to test several ideas and courses of action, including a consumer charter of rights. Additionally, it was felt that family members of consumers and those working in the health care system also had valued experiential perspectives that would further inform the committee’s research.

During a previous preliminary research phase, a short on-line survey had garnered interest in the mental health community. The committee chair and research team believed that this provided a foundation upon which to launch a more comprehensive initiative. There was anecdotal evidence that participants were particularly sensitive to providing information about their mental illness and addiction experiences. To address this issue, two specific courses of action were implemented. First, the ability to make an anonymous contribution had to be provided. Second, while participants were on the consultation site, the session had to be encrypted to ensure that contributions submitted were private and secure.

The primary target audiences for the e-consultation were consumers (persons living with mental illness or addiction), their families and caregivers, and service providers (health professionals working in the Canadian mental health and addiction system). However, participation was open to all those interested in completing a workbook or sharing an idea or experience.

The workbook began by soliciting participants’ views on the current state of the Canadian mental health and addiction system. Participants were then invited to assess a series of scenarios that illustrated options for improving the Canadian mental health and addiction system, and to identify what they felt should be the priorities for action. They were also asked to comment on specific ideas under consideration by the committee, one of which was the creation of a charter of consumers’ rights. Participants were also given the opportunity to submit their personal recommendations on how to address some of the challenges currently faced by the Canadian mental health and addiction system through an open-ended (qualitative) idea-sharing process that complemented the close-ended (quantitative) questions of the workbook. Here, input was solicited under four main themes: access to services, services and supports, the role of the federal government, and, “If you could change one thing, what would it be?” A plainlanguage review of all consultation materials, as well as an external review by subject matter experts, was instituted to ensure that the content was accessible, balanced, relevant and accurate.

A unique partnership was established with Les Impatients, a Montreal-based organization that uses art as a form of therapy for those living with mental illness. The artwork was converted to a digital format and used throughout the on-line consultation Web site and on-line workbook as a means to make the on-line experience more engaging and reflective of the experience of participants.

Participants in the e-consultation were recruited via an active viral marketing campaign: a number of provincial and national associations with an interest in mental health were sent a letter signed by the committee chair, an invitation to their members to participate in the e-consultation and a promotional poster. Many groups responded by promoting the e-consultation within their networks. In addition, targeted advertising was placed in national mental-healthrelated publications.

The outcomes of the e-consultation exceeded the expectations of the committee and its research team. In all, 1,255 contributions were received, including 795 workbooks and 460 idea submissions. Participants included a mix of consumers, family members, service providers and a small group of concerned citizens. Close to half (43 percent) of workbook respondents were service providers, while the other half was made up primarily of consumers (22 percent) and family members (27 percent). The distribution of idea submissions was the reverse: approximately 40 percent were submitted by consumers, 35 percent by family members and 25 percent by service providers. Many participants “wore multiple hats,” sharing their views and experiences from multiple perspectives.

It is noteworthy that those most directly affected by the issue were most likely to opt for the qualitative process, often stating that they valued this opportunity to voice their concerns and share their thoughts directly with the committee. Reflective of this was the fact that the ratio of workbooks to ideas was almost two to one, much higher than our usual experience of 10 to 15 percent.

The on-line findings strongly supported the notion that issues of availability and accessibility of services, as well as discrimination and stigmatization, remain prevalent. Emphasis was placed on adopting a more holistic approach to mental health. Participants also advocated a broader federal role in establishing standards in mental health.

The parliamentary context and calendar can make comprehensive and long-term research challenging. The spectre of an election loomed large at several stages of the project and could be considered to have been disruptive. The consultation input period had just finished when the election was called and Parliament prorogued, resulting in the dissolution of the committee and the cessation of research. Fortunately, several key members of the committee remained when it was reconstituted under a new government and new session of Parliament.

The Library of Parliament, which provides research services to both the House of Commons and the Senate, was able to transfer many of the lessons learned from the House of Commons pilot initiative to this Senate research initiative. The internal library team led the development of the e-consultation content and lines of inquiry, and they were supported by analytical and technology expertise. The dynamics of the team facilitated a comparatively rapid development of the Senate e-consultation compared with the experience of the House of Commons pilot. This is consistent with our finding that the first e-consultation can have a steep internal learning curve. The success of the previous initiative not only had set precedents, but had also removed some of the barriers and resistance that are often associated with new approaches.

These e-consultations contributed to the momentum building for action. The 2007 federal budget announced the creation of the Mental Health Commission of Canada, with Senator Michael Kirby appointed as its first chair, and with a 10-year mandate to address several key issues identified in the e-consultation, including addressing the challenge of stigma, increasing access to knowledge and creating a pan-Canadian strategy for mental health.

From a public efficacy perspective, the mental health community can see its aspirations and recommendations begin to come to fruition. This is a tangible example of meeting public desires without a significant gap between expectations and what is to be delivered. It is a step in the right direction when it comes to reducing the democratic deficit.

The state of parliamentary committee partisanship in the context of minority governments, however, makes objective public involvement difficult. Speaker Peter Milliken’s recent statement in the House serves to validate this conclusion: “Frankly speaking, I do not think it is overly dramatic to say that many of our committees are suffering from a dysfunctional virus that, if allowed to propagate unchecked, risks preventing Members from fulfilling the mandate given them by their constituents” (2008). Indeed, since this initiative was completed, with the exception of an occasional Web survey, little comprehensive e-consultation work has been undertaken in either the Senate or the House.

Initiating deliberative and genuine e-consultation and public involvement in today’s parliamentary context is challenging, if not impossible. But objective research is still being undertaken by the Library of Parliament, which could be commissioned to undertake an engagement on behalf of a committee. Committee members might be profiled in a welcome message or an invitation to participate, but the design and operation of the e-consultation would be led by a research team. This might seem an odd approach at first, but it is similar to the means by which a committee might undertake a public opinion research poll to be delivered by a third party.

In fall 2004, Social Development Canada (now Human Resources and Social Development Canada), recognizing the need to engage Canadians on priority issues, identified caregiving, child care, seniors, persons with disabilities and communities as particular areas of focus. Because of the overlap in audiences and the horizontal nature of the issues, the department’s leadership determined that an integrated approach was needed to provide a coordinated effort in the area of public involvement (for a summary of this case, see box 2). Each issue was at a different stage in the policy development or decision-making life cycle. Caregiving was a new policy idea at the time, with little history or data on which to move forward. At the other end of the spectrum, child care agreements were being negotiated between the federal and provincial/territorial governments, and there was a rich foundation of policy to build upon with seniors and persons with disabilities. The role of communities was being investigated and framed in new and different ways.

An integrated engagement team was created with a mandate to deliver a coordinated consultation effort, both in person and on-line, on all five issues, where possible. The team was made up of directors general from each policy area, communications and the offices of two ministers. The authors provided expertise and advice on the process to complement this team.

There was an urgent need to launch the caregiving consultations, as there were significant gaps in the policy research and the leadership felt that consultations with caregivers, experts and stakeholders could help move the file forward. As a result, the caregiving e-consultation was launched first. The child care issue was in the midst of federal-provincial/territorial negotiations, so that, with the exception of a few ministerial round tables, broad consultations (electronic or otherwise) were deemed inappropriate at the time. The seniors and persons with disabilities files had several potential areas of interest for consultation and were seen as the logical candidates for the second consultation phase. Communities had recently commissioned policy research, so it was decided that consultations on this topic would be undertaken as the third phase, once the issues were more clearly defined. The election and change in government ultimately meant that this issue was not consulted on in a fashion similar to the others.

This initiative was broader than e-consultation alone, since the intended audiences to be engaged were citizens, stakeholders, experts and parliamentarians, as well as other governments, but the e-consultations were designed to complement and provide a broader perspective than was possible with ministerial roundtables, bilaterals and, in certain cases, negotiations. The e-consultations were made available to all Canadians, and the e-consultations on caregiving, persons with disabilities and seniors included their own workbooks and a storyand idea-sharing process. A single Web site provided participants with the opportunity to learn about or take part in all three e-consultations. Significant efforts were undertaken to ensure technological accessibility for persons with disabilities.

From the department’s perspective, the caregiving initiative was the most successful because of the prioritization data that were collected via the workbook and the rich anecdotal input from the stories and ideas. These tied into a policy report that served as the foundation for a conference that brought together a diversity of stakeholders to set the national caregiving agenda. Since this was a new issue with little data on needs and priorities, the input received through the e-consultation proved invaluable for the department’s policy team, and provided a rich foundation for discussion during the stakeholder conference. The caregiving consultation generated a total of 657 contributions, divided between 497 workbooks and 160 story submissions.

The persons with disabilities consultation findings provided additional policy input, generating a total of 724 contributions, divided between 520 workbooks and 204 story and idea submissions. It is interesting that the qualitative input provided by persons with disabilities exceeded our traditional ratio, with almost one story for every two workbooks. As was the case with the Senate e-consultation, the most vulnerable audiences typically were the most likely to favour the storyand idea-sharing process (versus the workbook).

The seniors initiative had a relatively low level of participation compared with the other two consultations, with outreach and communications efforts garnering only about 200 contributions, a scale too small to facilitate a broad base of input for analysis. It is possible to speculate as to why this initiative did not resonate with the community in the same way, but there are no concrete means to draw conclusions.

Coordinating five different policy areas, communications and two ministers’ offices was quite complex — these groups do not often work together horizontally or even bilaterally — and it is largely due to the support and commitment of senior leadership that this initiative took shape.

The parliamentary calendar and the precarious nature of a minority government also placed considerable strain on the process. Timelines and priorities often changed. One particular challenge during these e-consultations was the restriction placed on advertising as an outcome of the sponsorship scandal. As a result, it was difficult to spread the word comprehensively about the e-consultations. The only way to recruit participants was to promote the e-consultations on the department’s Web site and to enlist the support of intermediary interest groups to spread the word about them. While viral marketing is often the most effective way to promote an e-consultation, the nature of this process makes its outcomes somewhat unpredictable: in some instances, it works very well (the message “sticks” and is actively propagated); in others, it proves less powerful (the message does not resonate with the audience or is crowded out by competing messages). Having access to other means of promotion to supplement viral marketing is therefore invaluable.

The approval process was also quite challenging, since cabinet approval was required for the overall approach. For the on-line consultation, specifically, there were several steps to the internal approval process, followed by a final review by the Privy Council Office.

With this, as with other initiatives, in an organization’s first comprehensive e-consultation, there are internal lessons to be learned. The most significant lesson from this initiative was the recognition of the value of public involvement. Social Development Canada made a serious commitment to develop a culture of public involvement, supported by a corresponding investment in capacity and resources. The Public Involvement Secretariat was formed at the conclusion of this initiative to serve as a central resource for policy and program areas.

Since this initiative was undertaken, Social Development Canada and Human Resources Development Canada were merged to create Human Resources and Social Development Canada (HRSDC). This was more than a simple reconfiguration — it was the reintegration of two completely different organizational cultures. Social Development Canada had taken steps toward reducing the democratic deficit, not as an explicit departmental objective but, rather, as an outcome of interacting with the public. By establishing a new civic discourse, the department was able to create some civic literacy concerning its priority issues. Since the formation of HRSDC, however, several major backward steps have been taken: the publics are more stakeholder focused, and more open and inclusive public involvement is now the exception. From an e-consultation perspective, there is a renewed emphasis on simple electronic surveys.

HRSDC still has the institutional knowledge and capacity to return to more democratic public involvement and e-consultation. Leadership is needed to build on Social Development Canada’s foundations. Through the establishment of guidelines or a public involvement framework, it might be possible to reintegrate standards, consistency and best practices. The question remains, though, whether time has run out on the opportunity to build on its predecessor’s experiments and explorations.

In 2001, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) undertook a review of specialty care in Canada and outlined its key findings in a discussion paper (2001). Five years later, and even though all levels of government had reinvested in the health care system since that time, the CMA still believed there was cause for concern. For example, wait times for specialty care services remained a critical issue, and access to primary care physicians was still problematic in many parts of the country. Referring back to our expanded decision model, the CMA wanted to update its definition of the problem and gather information that would allow it to develop sound alternatives that would be rooted in the realities of physicians on the front line of health care.

Beyond the need to review and update the data collected for the 2001 specialty care review project, the CMA was grappling with a broader internal challenge. A recently completed audit of its member communications activities indicated that awareness of the CMA’s efforts as an advocate for the profession, for patients and for improved health care remained relatively low among its members, even though members had a strong desire for the CMA to play this role at the national level. The audit also revealed that grassroots members wanted to be more engaged in the development of the organization’s policies and positions. In other words, the CMA was grappling with the very issue EKOS Research had described: the gap between how much people want to be involved and how much they feel that they are actually involved in decision-making and governance (Ekos 2006).

Given this combined need for relevant data and meaningful member engagement, the CMA chose to engage its individual members (grassroots physicians) in an e-consultation to identify issues of concern and potential solutions in the specialty care system (a summary of the results is shown in box 3). A supporting communications strategy was launched to raise awareness that the CMA was proactively engaging its members in this way; on-line and paper-based advertising, media relations and a direct e-mail campaign to members all served to communicate the message that the CMA was listening and was prepared to act on the input it received from its members.

While the CMA had determined that the on-line consultation would be on the subject of specialty care in Canada, it was important to engage its institutional stakeholders (provincial/territorial medical associations and affiliate specialty societies) in refining the dimensions of the issue and in understanding the different perspectives on this very complex topic. The CMA’s objective was twofold: to create an opportunity for building relationships with its strategic stakeholders; and to ensure that the topics explored in the consultation were both relevant and grounded in the experience of physicians, residents and students.

A number of initiatives were implemented in support of these objectives: the creation of the Specialty Care Review Working Group, an advisory committee consisting of representatives of various provincial associations and affiliated specialty societies; the creation of a specialty care CEO task force, which provided communications and recruitment assistance; and the conducting of key informant interviews with representatives of various stakeholder groups. This enabled the collection of detailed input, which, in turn, informed the development of the consultation choice book that formed the core of the e-consultation process.

More than 38,000 CMA members were preregistered for participation in the e-consultation, and each received a personalized invitation e-mail that included “clickthrough” access to the e-consultation Web site, along with succinct information on the purpose of the e-consultation and how to participate. Prizes were also offered as an incentive for participation. Paper versions of the consultation materials were also made available to those who could not, or preferred not to, participate on-line. In addition to completing the choice book, participants in the e-consultation were invited to share their thoughts and personal experiences of the specialty care system. They could recount their story or that of someone they knew, or share their ideas for addressing a specific issue. The CMA was very clear in presenting the purpose of the e-consultation: to gain a better understanding of the challenges and opportunities within the specialty care system, as experienced by those on the front lines.

The CMA specialty care consultation ran for nine weeks and generated a total of 4,127 contributions: 3,884 choice books and 243 story and idea submissions. The on-line consultation tools enabled a two-way exchange between the CMA and its members, with a focus on the exploration of ideas and perspectives. Beyond simply asking questions, the CMA shared relevant facts, context-setting information and scenarios for consideration; it also candidly discussed the benefits and drawbacks of various options. Participants not only answered questions, they were also invited to share their thoughts and ideas to contribute to the CMA’s broader reflection on the issues.

Physicians invested up to one hour of their time to complete the consultation choice book, which achieved a 75 percent completion rate — a noteworthy rate given that physicians are an extremely busy and highly solicited group of professionals. Participants provided valuable input on the situation today but, most important, they also identified a number of priorities for action in the area of specialty care and in the health care system in general. (In addition to quantitative data generated by the on-line workbook, some 265,000 words of qualitative input were received, reviewed and analyzed.)

Findings from the on-line consultation were reviewed by the Committee of National Medical Organizations, Canada’s broadest forum of physician leaders, and by the Specialty Care review Working Group. This ultimately led to the formulation of 16 recommendations, which were adopted by the CMA board and which fed directly into the organization’s advocacy and policy agenda. The 16 recommendations were accompanied by a participants’ report, sent to each of the 3,884 workbook (choice book) respondents, telling them what conclusions had been drawn and what actions would be taken as a result of the input received through the e-consultation.

One of the main challenges of this type of initiative is communications and outreach. Close to 4,000 physicians participated in this e-consultation, but the CMA represents approximately 65,000 doctors, residents and medical students across Canada. To some, a participation rate of 6 percent is satisfactory, but the challenge of making more voices heard remains, particularly in the case of self-selected samples, as it was in this context.

Physicians are busy and oversolicited. Cutting through the “noise” to get and then maintain their attention for close to an hour can be a significant challenge. It was therefore critical that both the communications surrounding the consultation process and the consultation content itself be relevant, meaningful and to the point.

This e-consultation illustrated that a process that

is seen to be legitimate and credible has the greatest chances of success. The relevance of the issue for the target audience and the fact that, despite certain misgivings, participants trusted that their voices would be heard and that their contribution would make a difference in the decision-making process (a comment often heard in participants’ stories) were critical in this regard. This perception was reinforced by the distribution of the participants’ report.

The e-consultation was also designed with the needs of the audience in mind: a simple and userfriendly security model (preregistration) removed psychological barriers to participation, and the e-mail recruitment campaign allowed participants simply to “click to participate.” The consultation materials were designed to take full advantage of physicians’ experience and knowledge, and provided them substantive and balanced information for consideration. The “anytime, anywhere” nature of on-line participation provided a high degree of flexibility and convenience that made it easy for physicians to fit the e-consultation into their schedules.

Finally, the structured data collection process facilitated the analysis of the large volume of data collected. This proved to be invaluable, given that participation rates quadrupled the original target of 1,000 and that the volume of qualitative data collected was tenfold what had been expected.

The specialty care consultation was the first and largest e-consultation conducted by the CMA, and it marked a turning point in how the CMA engages its members. This success opened the doors for similar on-line initiatives, allowing the CMA gradually to build a critical mass of “cyber-engaged” members. However, input collected on-line has also served as fodder for continued discussion in other fora — for example, in a series of in-person dialogues between the CMA president and grassroots members during a pan-Canadian outreach initiative. The net result is that the CMA has renewed its commitment to consult, to be responsive, to be representative and to build a stronger, more personal relationship with its members.

In New Zealand, Toi te Taiao: the Bioethics Council was established after the Royal Commission of Inquiry on Genetic Modification to consider the cultural, ethical and spiritual issues raised by biotechnology (see box 4). In this role, the council provides information, promotes and participates in public dialogue and gives advice to the government. The council was scheduled to report to the government in May 2008 on the issue of prebirth testing, and sought to engage New Zealanders in an inclusive public dialogue on this issue.

Given its mandate to promote and participate in public dialogue, and given that prebirth testing touches the lives of so many people, the council needed to demonstrate leadership and the political will to engage citizens in open and frank dialogue on the issues. This vision reflects what Axworthy posits as a potential solution to the democratic deficit: changing the role of political parties (or, in this case, a government agency) to have increased responsibility for public discourse (2004).

The council therefore opted for a transparent, public and participatory process for framing the issue and developing its recommendations. More specifically, the council emulated the approach used by the US-based National Issues Forum Institute, which promotes the use of “issue books” as a framework for public deliberation. In choosing such an approach, the council aimed to make its public engagement processes more deliberative and focused. The goal was to ensure that the informed views and values of New Zealanders were reflected in the recommendations that the council would make to the government, while also ensuring that the recommendations were just, reasonable and practical.

The council’s approach was based on “multiway” interactions. First, members of the public helped develop the deliberation framework by participating in a public issue-framing exercise. Some 56 citizens contributed to identifying the issues and approaches that were subsequently outlined in a choice book that formed the centrepiece of the various consultation activities undertaken by the council.

A series of 18 in-person public deliberative dialogue events was then organized to gather input from New Zealanders on the approaches under consideration; four of them were Maori-specific events. During these three-hour sessions, participants were called upon to review and discuss the four approaches outlined in the choice book. In order to expand the reach of this public dialogue, the council also launched a parallel online deliberation process that mirrored the content and structure of the in-person deliberative dialogues.

The focus, both in-person and on-line, was on evaluating (and augmenting) the alternatives that had been developed during the participatory issueframing process. In this regard, citizens were being called upon both to validate ideas (comparing them with the reality on the ground) and to reconcile ideas (weighing values, making trade-offs and prioritizing).

The on-line deliberation process consisted of an on-line adaptation of the in-person choicebook, a story and idea submission process and three on-line deliberation groups (actively moderated by council staff). Completing the on-line choice book, which took an average of 30 to 40 minutes, was a prerequisite for participation in the on-line dialogues. A paper version of the choice book was also available for those who could not or preferred not to participate on-line.11 While the consultation materials were not completely bilingual, care was taken to include Maori greetings and proverbs throughout the on-line choice book and Web site to be inclusive of New Zealand’s large Maori population. In addition, one of the four approaches under consideration focused specifically on the needs of the Maori.

Great care was also taken to protect the privacy of participants and to ensure the confidentiality of their personal information. For example, given the personal and sensitive nature of the issue, participants could choose to complete the choice book or share their story or idea anonymously. Participants were asked to choose whether they wanted their story or idea submission to be published in the “shared area” of the Web site or kept private. Participants in the on-line deliberations could elect to participate under their real name or under the pseudonym of their choice.

Finally, the council undertook a number of initiatives aimed at raising awareness of its on-line deliberation and driving traffic to the on-line deliberation Web site. An e-mail campaign was undertaken to invite people who had already registered their interest in the project to participate, as well as to all those who were registered in the council’s general database. In addition, a printed article in a national magazine was in wide circulation during the e-consultation period. Finally, two ads were posted on New Zealand’s popular TradeMe Web site.

The on-line deliberation Web site was launched on November 2, 2007, and closed on February 13, 2008. Participants contributed a total of 406 choice books and 64 stories and ideas. In addition, 58 individuals actively participated in one of the three on-line dialogue groups, which ran for three weeks each and generated more than 130,000 words of comments. Interest in the on-line dialogues was such that, within two weeks of launching the e-consultation, registration to participate in the on-line dialogues had to be terminated because the three planned sessions were already at capacity. It should also be noted that, while the topic of the e-consultation technically affected all citizens, those who were most inclined to participate generally had a very personal interest in or experience of prebirth testing: respondents were predominantly female and of child-bearing or childrearing age. Most (or their spouses/partners) had experienced a pregnancy and had or planned to have children. A fairly high proportion also had some knowledge and/or experience of prebirth testing. As a result, while response rates for the choice book and story and idea submissions appear relatively low, they nonetheless exceeded expectations.

While the quantitative input collected through the on-line choice book provided a useful baseline of information, the qualitative input received via the stories, ideas and on-line dialogues powerfully put “a human face” on the issues. The depth and quality of participants’ comments and ideas also reflected the effort they had made to acquaint themselves with the issues and approaches when completing the on-line choice book. In particular, the council noted that in many cases, participants in the on-line dialogues had been able to explore issues in more depth than had been possible in the three-hour in-person deliberative dialogues. This was due in large part to the asynchronous nature of the on-line dialogues, which allowed participants to engage in a “read-reflect-respond” pattern. In other words, engaging in text-based deliberation allowed participants to integrate what was being said in the forum at their own pace, to reflect upon it further, to research the issues and to take the time to craft their responses carefully.