Volunteers have traditionally played a significant role in Canadian political parties, as campaign workers, supporters of candidates for party leadership or nomination, and local organizers. In the contemporary era of professionalized, media-oriented politics, however, the already circumscribed role of the Canadian party member has been limited even further. In this paper, the authors analyze the data of a 2000 survey of members of what were then Canada’s five major political parties and find that party members are not satisfied with their ability to shape party policy and are particularly resentful of the extent to which political professionals have usurped the role of the party member.

Because party membership in Canada is a form of public service and thus contributes to the vibrancy of political life in the country, the authors argue that we should be concerned that rates of party membership appear to be dropping, the average party member is nearing retirement and is not being replaced, and rates of activism within parties are relatively low. All of these tendencies are products of complex social change, reinforced by institutional constraints that have historically limited the role of Canadian party members. As such, they defy easy solutions. Cross and Young argue, however, that one approach that might encourage party membership and help political parties to fulfill their roles in public life would be to encourage parties to give a more meaningful, ongoing role in the development of their public policy positions to their rank-and-file members.

They suggest that if parties are to attract more Canadians as members and, more important, as ongoing participants in their affairs, they need to offer voters greater opportunities to influence party stances on questions of public policy. It is their view that in the long term, the establishment of vigorous party-policy foundations would not only help to address the concerns of voters about the lack of a meaningful role for them in party politics but would also strengthen our parties and our democracy more broadly. At present, our parties have little capacity for generating new policy alternatives. The parliamentary parties are necessarily concerned with the immediate issues of the day and the extraparliamentary parties have few resources for anything other than election preparation. The result is that our elected officials are largely dependent on other organizations for policy innovation. Formal policy foundations, organized and maintained by the political parties, would both provide opportunity for grassroots members to influence a party’s policy direction and act as an ongoing policy resource for the parliamentary party.

Knowing that policy interest motivates party membership in Canada, and that stalwart party members are not content with their circumscribed role in policy development within their party, the authors see clear potential for parties to involve their members in policy discussions. In an era when Canada’s federal political parties are largely funded by the public treasury, it is all the more important that they find ways to engage meaningfully with segments of Canadian society. Moreover, public funding can be structured in a manner that creates incentives for parties to speak directly with citizens on matters of public policy.

In the period just after Confederation, the notion that membership or involvement in a Canadian political party was a form of public service would have been considered quite peculiar. More accurate would have been the idea that activism on behalf of a political party was a route into the public service, as civil service jobs were awarded to the loyal supporters of the governing party. In the contemporary era, with fewer opportunities for political parties to dispense patronage, it is more plausible to think about party membership as a form of public service, as most party members are volunteers motivated by a desire to play a role in political life.

In fact, drawing on the Study of Canadian Political Party Members, our 2000 survey of members of what were then Canada’s five major political parties,1 we find that individuals are drawn to party membership not by a desire to further their personal interests but rather by support for their party’s policy stance and as participants in intraparty personnel contests. This conforms to a notion of public service as volunteerism motivated by a desire to participate in or influence discussions of public policy and party affairs. Volunteers have traditionally played a significant role in Canadian political parties, as campaign workers, supporters of candidates for party leadership or nomination, and local organizers. In the contemporary era of professionalized, media-oriented politics, however, the already circumscribed role of the Canadian party member has been limited even further. In our survey, we found that party members are not satisfied with their ability to shape party policy and are particularly resentful of the extent to which political professionals have usurped the role of the party member.

To the extent that party membership in Canada is a form of public service and thus contributes to the vibrancy of political life in the country, we should be concerned that the rates of party membership appear to be dropping, the average party member is nearing retirement age and is not being replaced, and rates of activism within parties are relatively low. All of these tendencies are products of complex social change, reinforced by institutional constraints that have historically limited the role of Canadian party members. As such, they defy easy solutions. We argue, however, that one approach that might encourage party membership and help political parties to fulfill their roles in public life would be to encourage parties to develop policy foundations.

Studies of political party organization and membership in Western Europe and North America in recent years point to significant changes in party organization, driven by declining rates of membership in political parties. The most notable of these studies is a book entitled Parties Without Partisans (Dalton and Wattenberg 2000), the title of which telegraphs a key concern about the development of party organization in these established democracies. The consensus among political scientists who study political parties in established democracies is that rates of party membership have declined over the past three or four decades (Scarrow 2000; Norris 2002; Heidar and Saglie 2003). The extent of the decline and the rate at which it has occurred vary by country, but the overall trend is in a downward direction. Moreover, rates of activism tend to be very low, and in many cases declining, among party members in these industrialized democracies (Scarrow 2000; Norris 2002; Heidar and Saglie 2003; Gallagher and Marsh 2002; Whiteley and Seyd 2002).

Although these findings have profound implications for the role of political parties in modern democracies, they must be placed in context. When measuring numbers of party members or the rate of party membership in the electorate, the initial basis for comparison is usually the 1950s or 1960s. Susan Scarrow (2000, 94-5) points out that “it was only in the 1950s and 1960s that many countries had parties of both the left and the right successfully pursuing mass enrolment strategies. Before and after this period, parties exhibited an uneven pattern of commitment to, and success in, enlisting supporters in permanent organizations.” As Scarrow points out, the period from the Second World War until the 1970s was a historical anomaly, with unusually high rates of membership. Using this time as a basis for comparison overstates the magnitude of the decline.

Even if the decline in rates of party membership is somewhat exaggerated by the basis for comparison, there remains the question of why membership rates began to fall after reaching these unprecedented highs in the postwar era. Norris’s (2002) cross-national analysis makes it clear that this is a phenomenon of affluent established democracies; in fact, she finds that affluent countries generally have lower rates of party membership than other democracies. This finding lends general support to the modernization thesis, which holds that various aspects of the modern social and political order in advanced industrialized nations lead to a weakening of the bond between the public and political parties (Dalton and Wattenberg 2000, 10-11).

More specifically, the modernization thesis suggests that increases in education, changing values held by citizens, changing modes of social organization, the rise of the mass media, tendencies toward professionalization and changes in technology all combine to weaken citizens’ attachment to political parties and to discourage membership in party organizations. At the level of the individual citizen, higher rates of education result in “cognitive mobilization” of citizens. With greater intellectual resources at their disposal, these individuals become self-sufficient political actors who are less deferential to political elites and less inclined to look to elites for political cues, opting instead to make their own choices (Dalton and Wattenberg 2000, 10-11). More complex patterns of social organization, when combined with this cognitive mobility, reduce the basis for group mobilization. Individuals in these postindustrial societies are less inclined to identify themselves as members of a social group — such as the working class — and are consequently less available to be mobilized as group members. Overall, these individual-level changes result in a smaller supply of individuals who can be mobilized to partisan activity.

Aspects of social organization in modern societies also contribute to declining membership in political parties. In particular, the rise of the electronic mass media supplants the role of party members in spreading the party’s message, and the rise of public opinion polling reduces party leaders’ need to gather information about the mood of the electorate from party members. Norris (2002) finds empirical evidence for this assertion. In her cross-national analysis, she finds that rates of party membership are lower in countries that have a high rate of ownership of television sets. From this, she concludes that the electronic broadcast media act as a substitute for party mobilization in established democracies. Parties communicate with voters not through volunteers who spread the word but via carefully crafted television advertisements.

Along with the rise of electronic media and opinion polling comes a professionalization of parties, in which fundraisers, pollsters and communication consultants come to fill the functions that were once the preserve of members of political parties. As a consequence, the conduct of politics goes from a labour-intensive undertaking in which volunteer labour was a necessity for an electorally competitive party, to a capital-intensive activity in which money, rather than volunteer labour, is essential to electoral success. In essence, technological changes have reduced parties’ demand for active members in these affluent, established democracies.

Given these trends, it would be reasonable to predict that political parties may one day become organizations without members. If party leaders do not need members to run election campaigns, maintain party organization and serve as informational conduits between the electorate and the party leadership, then why should they continue to recruit party members? In considering this question, it becomes clear that party members serve functions other than those listed above. First, parties gain legitimacy from their membership; if they are not able to point to some membership base, they may lose credibility in the eyes of the electorate. The existence of a membership base lends an air of legitimacy to decisions made by the party, not the least of which are the selection of a leader and the choice of candidates for legislative office. Second, members can be important assets in intraparty battles (Scarrow 2002, 100). As long as party constitutions give party members a voice in selecting party leaders, there will be an incentive for aspirants to mobilize members into the party to support their quest for the leadership.

This raises the question of how parties can recruit new members from the cognitively mobile and atomized societies that we find in most established democracies. Comparative studies show that parties have responded to this challenge in large part by moving in the direction of “plebiscitary” party organization, in which members are accorded direct votes in the selection of party leaders and on selected matters of party policy and direction (Scarrow 1999; Seyd 1999; Whiteley and Seyd 2002, 213). In their research in Britain, Whiteley and Seyd (2002) conclude that such techniques may increase the size of a party’s membership but do not increase the rate of activism within the party.

A strategy that parties facing such challenges often adopt is to turn to the state for financial support that allows them to purchase the services of professionals to maintain party organization (Katz and Mair 1995; van Biezen 2004). Increasingly, political parties are portrayed in both academic and political discourse as “public utilities” that perform services that are necessary to electoral democracy and that must be supported financially by the state. Certainly, with the advent of quarterly funding for Canadian political parties at the federal level, we can see that Canadian parties have, to varying degrees, adopted this strategy (Young et al. 2005). If state funding reduces a party’s need to maintain an active base of members and supporters, it may exacerbate tendencies toward party organization in which members play a minimal role.

How does Canada fit into this picture of declining party memberships? On one hand, there is little evidence that rates of membership in Canadian parties have declined substantially. In her comparative analysis, Scarrow (2000, 88) observes that the United States and Canada “do not support the picture of ‘decline,’ though they do match the picture of contemporary parties as lacking strong membership bases.” In essence, the golden era of the mass membership party never dawned in Canada.

Few Canadians choose to belong to political parties on an ongoing basis. An Institute for Research on Public Policy study by Howe and Northrup (2000, 89) found that 16 percent of respondents claim to have belonged to a political party at some point in their lives. This figure probably includes a significant number of “partisans” of a party who have never formally held membership. Our best estimate, from an examination of membership patterns over time, is that between 1 and 2 percent of Canadians belong to a political party on a year-to-year basis. This places Canada at the bottom of the list of Western democracies.

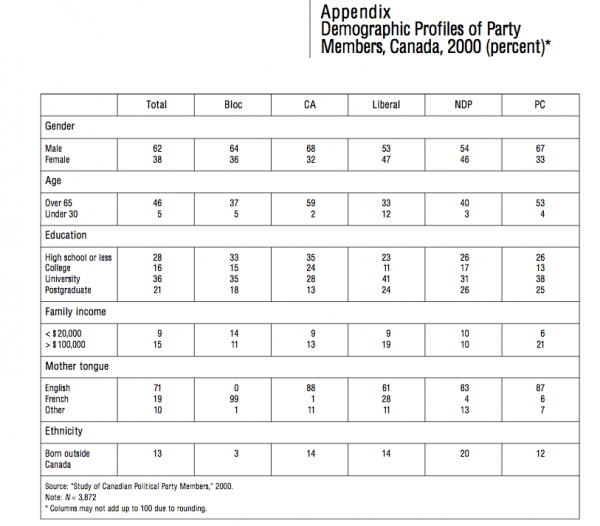

Moreover, Canadian party members are much older than the general population. In our survey, we found that the average age of party members was 59. Almost half our respondents were senior citizens, and only one in 20 was under age 30. Some of this age distortion may be explained by respondent bias, as seniors are more likely to participate in mail surveys than are their younger counterparts. However, this factor alone cannot explain the degree to which Canadian political party membership appears to be “greying.” Similar findings are reported in a study conducted by the IRPP in 2000, which found that only 5 percent of Canadians aged 18 to 30 have ever belonged to a political party (either federal or provincial), compared with one-third of those over age 60 (Howe and Northrup 2000). The same question was asked in a survey conducted in 1990; at that time, 10 percent of respondents aged 18 to 30 reported having belonged to a party. This decline over time in the rate of party membership among youth lends some credence to the idea that Canadian political parties, as membership organizations, are in decline.

No Canadian political party has achieved the kind of mass membership enrolment that characterized mass parties of the mid-twentieth century. The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and then the New Democratic Party (NDP) represented an effort to build a mass-type party in Canada, but neither party was able to achieve the kind of social encapsulation that leftist parties in Western Europe achieved. This may in part reflect the limited salience of class identities in the Canadian context, but it is also a product of the unique circumstances of Canadian political parties. R.K. Carty (2002, 729) notes that Canadian parties must accommodate differences among diverse and shifting coalitions of supporters, and have “little in the way of the material or ideational glue that traditionally holds political parties together.” As a consequence, “the conventional model of a centralized, disciplined mass membership party, speaking with one voice, and committed to offering and delivering an integrated and coherent set of public policies has never been the way to do this successfully” in the Canadian experience (Carty 2002).

Although the Canadian party system did not experience the full effects of the rise of the mass party in the mid-twentieth century, the formation of the NDP and changing expectations about internal democracy did provide a stimulus for the two traditional brokerage parties to increase the influence of their members. During the 1960s and 1970s, the grassroots party memberships gained greater influence over the selection of the party leader, gained the power to oust a party leader and won some influence over setting party policy (see Carty, Cross, and Young 2000, 110-11). As a result of these developments, the traditional influence of Canadian party members at the local level, especially in controlling local party affairs and selecting candidates, was enhanced by a new influence over the selection of the leader at the national level.

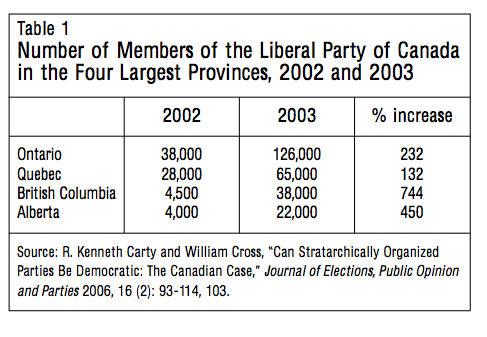

Members’ entitlements to vote in local nomination contests and in national leadership contests are the two significant entitlements that accompany membership in a Canadian political party. It is not surprising, then, that levels of membership in Canadian political parties follow a cyclical pattern. The number of members who belong to each party can double or even triple in election years and in years when the party is selecting a leader. Table 1 shows the dramatic increase in Liberal Party membership in each of the four largest provinces in the run-up to its 2003 leadership vote. Candidates seeking either the party’s nomination or its leadership mobilize supporters into the party, bolstering the membership ranks. However, after the contest is over, many of these individuals drop out of the party, leaving the stalwarts who maintain the party organization between elections. The vast majority of these members take no further part in party activities. This cyclical pattern suggests that voters are willing to join a party when they see some value offered in exchange for their taking out membership: a vote in the party’s leadership or nomination contest. When these contests are not imminent, however, these individuals let their membership lapse.

This raises the important question of why voters who are open to the possibility of participating in party politics will not maintain ongoing memberships. We suggest that the answer to this question is, at least in part, that voters do not see membership in political parties as a way of influencing the country’s politics (aside from personnel selection). The Howe and Northrup survey (2000) offers some evidence of this. They find that, by a three-to-one margin, Canadians believe that belonging to an interest group is a more effective way of influencing public policy than is participation in a political party. This public perception is not erroneous, as even the parties’ core group of consistent members are largely dissatisfied with the role they play in ongoing party decision-making. (We discuss this in some detail below.)

The cyclical pattern of membership numbers suggests that party members remain a valued resource for party leaders in intraparty contests. The same modernizing factors that have decreased party leaders’ demand for party members in other industrialized democracies are also at work in Canada, however. Canadian political parties have availed themselves of the services of opinion pollsters for checking the public mood, and use television and other electronic media as their primary means of communicating with voters. Canadian parties have become professionalized organizations in which volunteer labour is simply less necessary than it once was. In short, members remain valuable to Canadian parties primarily as a source of public legitimacy and as a resource in intraparty contests.

When we examine organizational changes in the major political parties over recent decades, we find clear signals that parties continue to seek members as a source of legitimacy. Led by the Reform Party/Canadian Alliance, Canadian parties have shifted their organizational modes in the direction of plebiscitary models of internal party democracy (Young and Cross 2002b). The clearest manifestations of this are the move to give every party member a direct vote in the selection of party leader, the moves of three of the major parties (the Canadian Alliance, the Progressive Conservatives and the Bloc QueÌbeÌcois) away from decentralized forms of party membership in favour of a national party list and the occasional use of referendums within parties on crucial policy issues (see Carty, Cross and Young 2000, chap. 6). The move toward plebiscitary democracy in Canadian parties had its greatest momentum in the 1990s, but the majority of reforms implemented during this period remain in place. While the merits and the success of these initiatives are subject to debate, their existence is a clear sign that the leaders of Canadian parties continue to see a value in trying to recruit and retain party members outside of leadership contests.

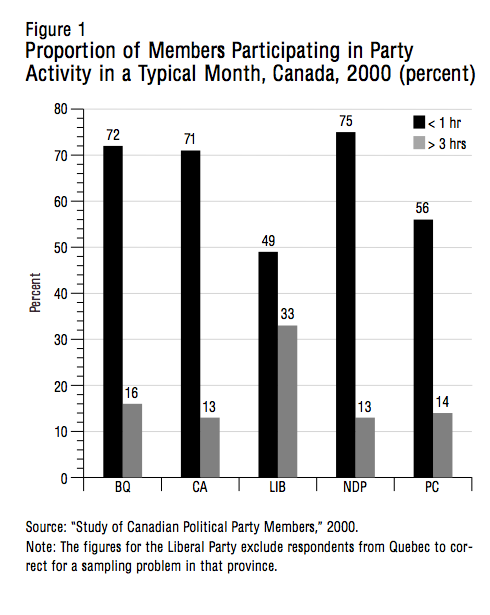

Not only do few Canadians belong to parties, but those who do are not particularly active. Our data, collected during a non-mobilization period when we suspect only the most stalwart of party supporters maintained their memberships, indicate that fewer than half of these party members engage in ongoing party activity. Our survey shows that 4 in 10 members report spending no time on party activity in a typical month, and an additional 2 in 10 commit less than one hour per month. As shown in figure 1, we found significant variance among the parties in this regard, with the Liberal and Progressive Conservative parties having fewer members who are disengaged from party activity than do the newer parties. This may be a governing party effect with activists more likely to participate in a party that has access to the levers of government and the accompanying patronage powers.

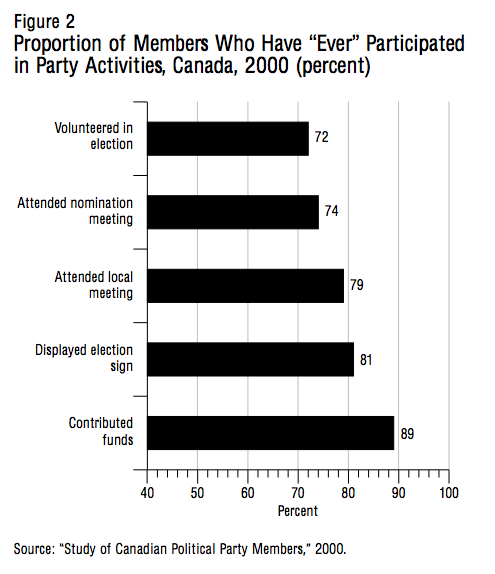

Similarly, 4 members in 10 report not having attended a single party meeting during the past year, and fewer than 4 in 10 attended more than two meetings. And, as illustrated in figure 2, almost one-quarter of members report that they have never attended a meeting of their local party association or volunteered in an election campaign. While participation rates of 75 percent may seem high, it must be kept in mind that the question asked of members was whether they had “ever” done each of the activities, and also that the population being surveyed was the stalwart (interelection) party members. On the other hand, 9 in 10 members report having contributed funds to the party. Many then appear to be what we might call “chequebook” members, willing to contribute funds to the party but not active in party affairs in any way that may be thought of as akin to public service.

Theoretical accounts suggest three categories of motivation for belonging to a political party (Young and Cross 2002a). The first category — material incentives — harkens back to the postConfederation era of Canadian politics, when patronage provided ample incentive for membership. The broad category of material incentives includes patronage appointments and government contracts as well as more general inducements like career advancement. The second category — social incentives — offers potential participants the company of like-minded individuals and social or recreational opportunities. The third category — collective or purposive incentives — gives individuals an opportunity to assist in achieving the party’s collective policy or ideological goals.

In most but by no means all industrialized democracies, material and social incentives have declined in importance over time. Civil service reforms and changing political values have reduced the practice of patronage, thereby reducing the parties’ ability to offer material incentives to potential members. As recreational opportunities have expanded and the bases of social organization on which mass parties were formed have eroded, parties have been less able to offer social incentives to membership (Ware 1996). This leaves the category of collective incentives as the primary set of motivators for partisan involvement.

If membership in a political party is a form of collective action, then it is subject to what Olson (1965) identified as the “free rider problem.” Olson argues that people have no incentive to participate in political action if they can benefit from the outcome without joining in the mobilization. “Free riders” are individuals who enjoy the benefits of a mobilization without participating in the campaign. In the context of political party activism, the question is this: If party involvement provides only collective benefits, what incentive does an individual have to join a political party?

Although there have been no comprehensive studies of the motivations for Canadians to join political parties, much of the literature suggests that supporting a candidate for the leadership of the party or for the party’s nomination in an electoral district is seen as one of the significant reasons for joining a party. In his study of Canadian parties’ constituency associations, Carty (1991, 38) found clear evidence that the Liberal and Progressive Conservative parties’ membership numbers fluctuated vastly between election years and non-election years, leading him to conclude that “when party elections are to be held — to nominate a candidate in an election, or select delegates for a leadership contest — membership takes on its meaning and worth, and individuals are mobilized for these contests with little concern for longer-term involvement or participation.” This pattern did not hold for the NDP, which Carty found to have a more stable pattern of party membership.

In their study of members of the Reform Party in 1993, Clarke et al. (2000) found that collective incentives most commonly motivated party membership. When members were asked what was their most important reason for joining the party, the most frequent responses were concern with the deficit or economic problems (31 percent), concern with moral principles in government (29 percent), dissatisfaction with the thengoverning Progressive Conservative Party (22 percent), concern that the province of Quebec was too powerful (17 percent), and a desire for individual freedom and less government (16 percent). A mere 2 percent of respondents cited material incentives, either business contacts or a desire to run for public office, as their most important reason, and only 1 percent indicated that their primary motivation was that friends or family are party members. Respondents were not asked whether supporting a candidate for the party’s nomination or leadership was a factor in their decision.

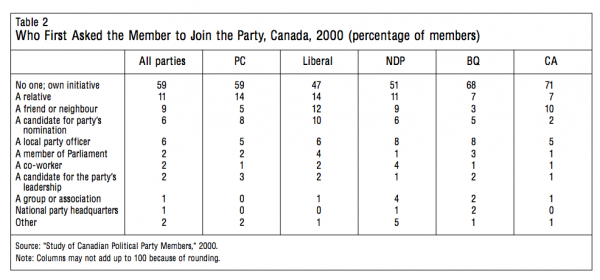

To what extent are individuals recruited into Canadian political parties, and to what extent do they take the initiative to join the party? Table 2 below summarizes responses to the question “Who first asked you to join the ___ party?” It is clear that, at least among the long-term or core members of the five parties who responded to our survey, the majority were not recruited into party activity but rather took the initiative to join the party themselves. This pattern is all the more evident in the two newest parties — the Bloc and the Canadian Alliance — in which 68 percent and 71 percent of members, respectively, joined of their own initiative.

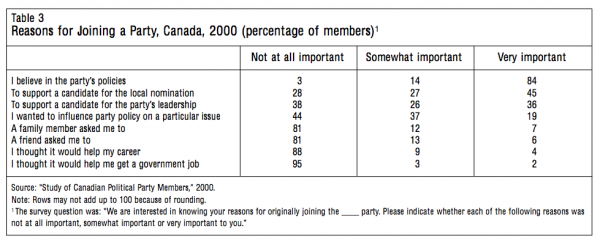

These patterns of recruitment suggest that conventional understanding of the importance of social networks and participation in leadership and nomination contests to joining Canadian political parties may be overstated and of limited salience in explaining membership in the more ideologically oriented parties. To determine this with greater certainty, however, we need to examine party members’ reasons for initially joining their party. Respondents were given a list of eight reasons for joining the party and were asked to rank each one as not at all important, somewhat important or very important. Responses were not mutually exclusive.

As table 3 demonstrates, belief in the party’s policies is the reason for joining given the greatest weight by party members. Fully 84 percent of respondents to the survey indicated that this reason was very important to them. Although important, support for a candidate for the party’s leadership or nomination lagged far behind policy as a reason for initially joining the party. Of course, if we were to add the 45 percent of respondents who indicated that supporting a candidate for the local nomination was very important to the 36 percent of respondents who indicated that supporting an individual for the party’s leadership was very important, this would suggest that these personnel-related concerns were as important as belief in the party’s policies. However, on closer examination we find that these are for the most part the same respondents: 72 percent of respondents who indicated that supporting a candidate for the leadership was a very important reason for joining the party also indicated that supporting a candidate for the nomination was very important. That belief in the party’s policies outweighs personnel-related reasons for joining suggests that even though Canadian parties have recruited a substantial portion of their members through such routes, the individuals recruited for the most part feel some attraction to the party’s ideological stance and are not merely joining in order to support an individual.

Contrary to expectations that a substantial portion of party members are recruited by friends or relatives, only 6 and 7 percent of respondents, respectively, indicated these as very important reasons. However, recruitment through a social network is related to support for a candidate for the nomination. Among respondents for whom recruitment by a friend was very important, 65 percent indicated that supporting a candidate for the nomination was also very important; similarly, among respondents for whom recruitment by a family member was very important, 60 percent indicated that supporting a candidate for the nomination was very important. To the extent that recruitment through social networks occurs, then, it appears closely tied to recruitment for nomination campaigns.

Finally, the very low percentages of respondents indicating that they initially joined the party for material reasons — to help their career or get a government job — indicate that material incentives have very little power to attract individuals to Canadian political parties. This is not particularly surprising, given the relative absence of patronage or other such inducements available to Canadian parties.

In short, these findings support the notion that party membership in Canada is for the most part motivated by a sense of public service. Relatively few members join political parties in the hope of furthering their careers or getting a government job, whereas many are motivated by support for their party’s policy stance. This signals a desire to influence public policy, which is precisely the public service that we expect political parties to perform.

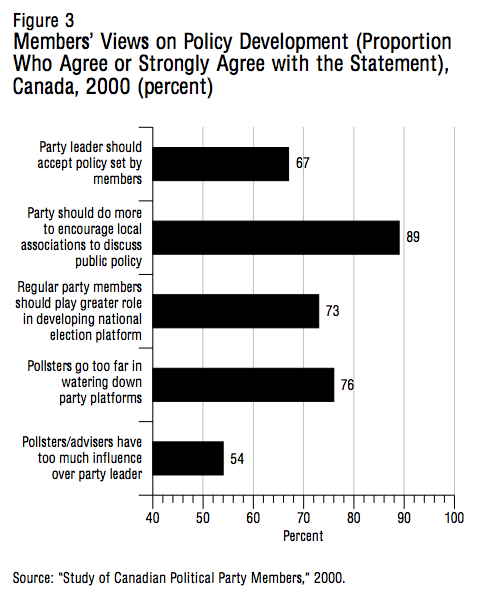

Members of Canadian political parties are largely dissatisfied with the role they are accorded in the development of party policy. As figure 3 shows, a majority of members of the five parties believe that members should have greater influence over party policy, while pollsters and advisers should have less. When given a choice between the statements “The party leader should have the freedom to set party policy” and “The leader should accept policy set by members,” two-thirds of respondents chose the latter statement. While the results varied somewhat by party, a majority of members in each of the five parties favoured the idea that the leader should accept policy set by members. It is not surprising, then, that the vast majority of members agreed with statements to the effect that the party should do more to encourage local associations to discuss public policy, or that regular members should play a greater role in determining their party’s national platform. In each of the five parties, including the populist Canadian Alliance, a sizable majority of members agreed with the latter statement.

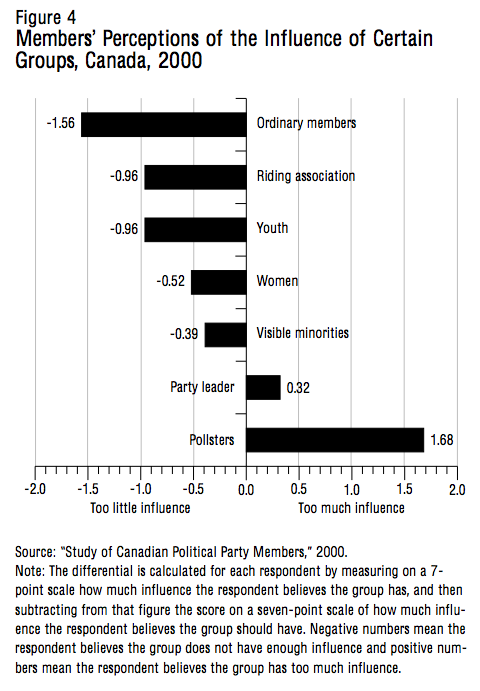

The data presented in figures 3 and 4 suggest that party members are acutely aware that their traditional functions have been usurped by professionals. A majority of members of each party agree that these political professionals have too much influence over the party leader, and that this influence is used to water down the party’s platform. Figure 4 demonstrates party members’ perceptions of which groups lack influence and which have too much influence. Party members perceive that ordinary members and riding associations are the most severely lacking in influence, while they believe that pollsters exert too much influence.

From this analysis, it is evident that members of Canadian political parties are far from content with their role in the party. Keeping in mind that the party members surveyed are those who renew their membership in non-election, nonleadership-contest years, the analysis leads us to believe that contemporary Canadian political parties are ill equipped to offer inducements to membership adequate to engage significant numbers of Canadians.

Our story to this point is one of political parties with few engaged members who are generally dissatisfied with their role in party life. In considering how our political parties might reinvigorate themselves, there are several points that are central to our investigation. The first is that while Canadians’ satisfaction with their parties’ performances can be judged to be only middling at best, they have not given up the belief that parties are central to successful democratic practice. When Canadians were asked to score the parties on a scale of 1 to 100, their mean ranking declined by almost 50 percent between 1968 and 2000. However, at the same time, 7 in 10 Canadians agree with the statement that “without parties, there can’t be true democracy” (Blais and Gidengil 1991, 20).

Consistent with this, there is concrete, on-theground evidence that Canadians have not completely turned their backs on party politics. As discussed above, when parties offer grassroots voters a meaningful role in important decision-making, Canadians have shown a willingness to participate. This is evidenced by the dramatic increase in member recruitment during periods of candidate nomination and leadership selection. These personnel decisions have traditionally been left to the parties’ members. Knowing that their participation determines the outcomes of these contests, thousands of Canadians who otherwise shun participation in political parties are enticed to join them. However, we also know that the large majority of these recruited members do not maintain an active presence in the party between personnel recruitment contests. We cannot know for certain why individuals drop out of active party life, but we do know that those who remain are generally dissatisfied with the decision-making role afforded them. Put simply, they see decision-making power between elections concentrated at the centre with little substantive role for grassroots members.

Too often, local party branches are ignored by the central offices and allowed to atrophy between elections. Indeed, the central offices themselves often suffer dramatic decreases in budget and staff between elections, reducing their ability to invigorate the party membership. The party in office dominates during these periods at the expense of input from the extraparliamentary membership. The elected party needs the membership party to wage successful election campaigns and to support personal ambitions in intraparty contests but finds little use for them otherwise. As we have argued elsewhere, this is part of a trade-off in which the extraparliamentary members are given control over personnel recruitment in return for the elected party having near unchallenged authority in setting a policy direction (Carty, Cross and Young 2000, 155-6).

We suggest that if parties are to attract more Canadians as members and, more important, as ongoing participants in their affairs, they need to offer voters more extensive opportunities to influence party stances on questions of public policy. Along with providing voters with an incentive to participate in party affairs, this would provide real benefits to the parties themselves.

There are defensible reasons why Canada’s traditional parties have not regularly provided their members with a meaningful role in determining party policy. The principal rationale reflects the brokerage practice in Canadian politics. This is the notion that the setting of public policy requires the accommodation of many different parochial (often regional) interests. Accompanying this has been a belief that only a small elite, representing these varied interests, can successfully make the compromises necessary in shaping these factionalized interests into a national policy (Noel 1977). Consistent with this, party leaders, particularly when in government, have argued that their responsibility is to represent the interests of all voters and not solely those of their active supporters. Party leaders must necessarily balance party members’ desire to affect party policy with considerations of brokerage, representation and electoral viability.

It is not surprising, then, that we observe that the closer parties come to government, the more eliteconcentrated their decision-making on policy issues becomes. Parties far from government often position themselves as more participatory and democratic than their governing counterparts and, as proof of this, attempt to involve their active members in policy discussion and decision-making. The fledgling farmers’ parties of the 1920s, occasionally the CCF and the NDP, and the Reform Party of the early 1990s are all examples of this. Similarly, former governing parties that find themselves mired in the opposition benches often try to reinvigorate themselves by promising their grassroots supporters a greater voice in rebuilding the party and setting its policy course. Unfortunately, these promises rarely last after the party comes close to, or achieves, power. The federal Liberals of the 1960s and 1970s and the Ontario New Democrats of the 1990s provide examples of these phenomena (Clarkson 1979; Cross 2004, 37-9). The participatory enthusiasm sparked by the Liberals’ Kingston Conference and subsequently by the early days of Trudeaumania were quickly replaced with a disillusioned membership that once again felt isolated from important party decision-making. Similarly, the Ontario New Democratic Party under the leadership of Bob Rae faced strong criticism from its activist base when the party suddenly found itself in government and decreed, against long-standing party practice, that the parliamentary party (and thus the government) was not bound by the policy dictates of the extraparliamentary party. The result is that voters might be encouraged by perpetual opposition parties and wounded former governing parties to participate in policy debates, but should their preferred party get close to government, this participatory ethos is likely to evaporate. Once burned, voters are unlikely to come back for a second round of disappointment.

The position of the parties’ leadership on this issue is not without merit. Successive prime ministers have been correct in asserting that once in government, they are there to serve all Canadians. And it is elected members who are accountable to voters, not the parties’ activists. The data provided in the appendix to this paper, describing the socio-demographic makeup of party members, also speak against allowing them a direct role in the making of public policy. They are not representative of the total population. With few young people, disproportionately few women and in most parties a lack of regional and linguistic balance, members may not be well positioned to reflect the varied interests that need to be considered in making public policy. Of course, the parties’ elected caucuses regularly reflect the same representational deficits. Nonetheless, the challenge for parties is to create a role for their supporters in policy study and development while not abdicating the responsibility of the parliamentary party to make final policy decisions. It is our view that these are not intractable positions; parties can create an environment in which their grassroots members are invited to contribute to policy study and development in a manner that assists, rather than threatens, the elected party’s policy-making responsibilities.

Two democratic reform commissions have recommended that parties establish ongoing policy foundations for these purposes: the 1991 Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing and the 2004 New Brunswick Commission on Legislative Democracy. These commissions found Canadian parties lacking both in the provision of participatory opportunities for their members in the development of party policy and in their capacity for ongoing study and development of policy options in aid of their legislative caucuses. Parties in many Western European democracies have established such foundations, allowing them to engage their grassroots supporters in the policy development process and to develop a series of policy alternatives for consideration by the party in elected office.

One reason why Canadian parties have resisted the creation of policy foundations is cost. Canada’s extraparliamentary parties, wholly focused on campaign efforts, have traditionally husbanded their resources for these electoral excursions and expended few resources between campaigns. Parties are reluctant to divert funds to developing and maintaining a permanent policy structure if this is seen as taking away resources that might otherwise be available for campaign efforts. The New Brunswick commission recognized this concern and included in its recommendations partial public funding for both the start-up and ongoing operations of party policy foundations. This is consistent with the practice in many of the European countries with party policy foundations.

At the federal level, the 2003 changes to the Canada Elections Act provide the parties with ongoing financial support between elections ($1.75 per vote on an annual basis). All of this public funding goes to the parties’ central offices. The central parties also routinely claw back all, or a significant portion, of the public funding provided to constituency candidates. Thus, few if any of these taxpayers’ dollars are used to support grassroots activity within the parties. There is no reason that Parliament could not require that a portion of these public subventions be directed toward a policy foundation. The tax credit currently available for contributions to federal parties might also be extended to cover additional contributions to policy foundations. Parties may well resist such initiatives, as their emphasis on electoral readiness encourages them to direct their financial resources accordingly. Moreover, parties have traditionally resisted such incursions by the state into their internal affairs. We argue, however, that requiring parties to engage in policy development is not unreasonable, given the extent of the public funds they are receiving. Many party insiders bemoan the decline of Canadian parties as generators of new policy ideas (see Fox 2005); regulations giving parties incentives to reverse this trend would arguably address such concerns.

It is our view that, in the long term, the establishment of vigorous party-policy foundations would not only help to address the concerns of voters about the lack of a meaningful role for them in party politics but also strengthen our parties and our democracy more broadly. At present, our parties have little capacity for generating new policy alternatives. The parliamentary parties are necessarily concerned with the immediate issues of the day, and the extraparliamentary parties have few resources for anything other than election preparation. The result is that our elected officials are largely dependent on other organizations for policy innovation. The Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing captured the essence of this when it concluded: “The dilemma is that the core of the party organization is concerned primarily with elections; it is much less interested in discussing and analyzing political issues that are not connected directly to winning the next election, or in attempting to articulate the broader values of the party” (Royal Commission 1991, 292).

Not surprisingly, then, voters interested in influencing public policy issues are not attracted to parties.

The cost to our democracy comes from the fact that parties, not interest groups or policy forums, are charged with brokering the various parochial concerns and forging national interests. If parties are absent in the field of policy study and development, this task is made all the harder. Their absence is filled by advocacy and interest groups that typically represent specific socio-demographic segments of our population and are not charged with finding policy alternatives that serve a national interest. The civil service also plays a role in developing government policy, but there is often little opportunity for ordinary citizens to involve themselves in these processes.

When the legislative parties become involved in policy issues, not only are they ill served by their concern with short-term electoral issues, they are hampered by the representational deficits found within all of the elected caucuses. Liberal caucuses regularly include few members from the Prairie provinces, just as Conservative caucuses have few members from Quebec; and all the parties’ caucuses have a shortage of female and visible-minority members.

Party-policy foundations can help to address these concerns by serving as a vehicle for grassroots supporters and substantive experts to participate in the study and development of policy options within each party’s broad ideological framework. Foundations can ensure that voices not found in a party’s legislative caucus are heard in their work. In this sense, they can assist rather than detract from the accommodative work incumbent upon the national parties. Almost a century ago, the federal Liberal Party changed its method of leadership selection at least partly out of concern that its Quebec-dominated caucus did not reflect the diversity of views that should be heard in the selection of their leader (Courtney 1995, 5). Accordingly, it opened up the process to include its extraparliamentary members from across the country. Our current parties would similarly benefit from an opening up of the policy development process to include their activists and invited experts from all parts of the Canadian community.

Well-functioning policy foundations would provide the legislative parties with a vehicle for the generation of new ideas and for longer-term planning than is currently possible. This might be particularly helpful in assisting parties in making the adjustment from opposition to government. Operating at some distance from the cut and thrust of daily political debate, foundations can take a longer-range perspective and can prepare policy options outside the constant glare of the media and political adversaries that are the reality for their legislative caucuses.

Over the past century, political party membership in Canada has evolved from a route into the public service to a legitimate and important form of public service. A broad, active and representative membership base connects a political party to its societal base of support and enables it to mobilize support between and during election campaigns. However, Canadian political parties have never been particularly robust membership organizations, and there is some evidence that they face a looming crisis in their ability to recruit members. To some extent, this inability is the product of broad social forces far beyond the control of the parties.

That said, parties are able to conduct their internal affairs in a manner that encourages individuals to join parties in order to engage in meaningful policy discussions and contribute in some small way to policy formulation. Knowing that policy interest motivates party membership in Canada, and that stalwart party members are not content with their circumscribed role in policy development within their party, we see clear potential for parties to involve their members more fully in policy discussions. In an era when Canada’s federal political parties are funded largely by the public treasury, it is all the more important that they find ways to engage meaningfully with segments of Canadian society. Moreover, public funding can be structured in a manner that creates incentives for parties to speak directly with citizens on matters of public policy.

Our parties are often criticized for not presenting voters with competing, detailed policy prescriptions. At least in part, this results from a situation in which no branch of the parties’ organization is charged with the task of long-term policy study. The parliamentary parties are focused on the cut and thrust of daily politics, the party in central office is little more than an election preparation machine, and the party in the constituencies attract members who are interested in studying policy but are denied any effective capacity to do so.

Policy foundations could benefit parties in several ways. First, they would provide an additional incentive for individuals to join political parties and maintain their membership. The evidence is clear that voters do not see participation in parties as an effective way of influencing public policy. Rather, they prefer activism in interest and advocacy groups, leaving the parties with an aging and often dispirited membership. Parties still rely on their grassroots members for activities such as local election organization and fundraising, so a reinvigorated base of grassroots supporters may well provide electoral dividends.

More important, however, the development of ongoing policy study capacity would better equip the parties to fulfill the responsibilities of the central role they play in Canadian politics. Parties are meant to provide a link between civil society and government. In a sense this is part of the public service role they are meant to play, and for which they are increasingly well funded from the public purse. Central to this task is the collection and brokering of policy interests from among competing groups of voters. Their ability to perform this task is compromised when voters do not engage with them in the policy realm. The establishment of policy foundations would provide an opportunity for parties to hear from civil society interests and policy experts in regions and from socio-demographic groups that are not included in their parliamentary caucuses. In doing so they would be better equipped for the accommodative role required of our national parties.

It is both our parties and the character of our democracy that suffer when parties are not fully engaged in the policy study enterprise. The solution is not to strengthen the policy capacity of the leaders’ offices or of the Prime Minister’s Office. While such an approach might enrich the policy offerings of the parties, it would do little to reinvigorate the connections between parties and citizens. We end then by recalling that while Canadians are largely dissatisfied with the operations of their political parties, they believe them to be key instruments of their democratic practice. Voters have not given up on parties. Let us hope that, at least in the realm of policy study, parties have not given up on voters.

Blais, AndreÌ, and Elisabeth Gidengil. 1991. Making Representative Democracy Work: The Views of Canadians. Toronto: Dundurn.

Carty, R.K. 1991. Canadian Political Parties in the Constituencies. Toronto: Dundurn.

_____. 2002. “The Politics of Tecumseh Corners: Canadian Political Parties as Franchise Organizations.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 35: 723-45.

Carty, R. Kenneth, William Cross, and Lisa Young. 2000. Rebuilding Canadian Party Politics. Vancouver: University of British Colombia Press.

Clarke, Harold D., Allan Kornberg, Faron Ellis, and Jon Rapkin. 2000. “Not for Fame or Fortune: A Note on Membership and Activity in the Canadian Reform Party.” Party Politics 6 (1): 75-93.

Clarkson, Stephen. 1979. “Democracy in the Liberal Party: The Experiment with Citizen Participation under Pierre Trudeau.” In Party Politics in Canada, 4th ed., edited by Hugh G. Thorburn. Scarborough, ON: Prentice-Hall.

Courtney, John. 1995. Do Conventions Matter? Choosing National Party Leaders in Canada. Montreal, Kingston: McGill-Queen’s Press.

Cross, William. 2004. Political Parties. Vancouver: University of British Colombia Press.

Cross, William, and Lisa Young. 2002. “Policy Attitudes of Party Members in Canada: Evidence of Ideological Politics?” Canadian Journal of Political Science 35 (4): 359-80.

_____. 2004. “Contours of Party Membership in Canada.” Party Politics 10 (40): 427-44.

Dalton, Russell J., and Martin P. Wattenberg. 2000. “Unthinkable Democracy: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies.” In Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies, edited by Russell J. Dalton and Martin P. Wattenberg. New York: Oxford University Press, 3-18.

Fox, Graham. 2005. Rethinking Political Parties. Ottawa: Public Policy Forum, and Crossing Boundaries National Council.

Gallagher, Michael, and Michael Marsh. 2002. Days of Blue Loyalty: The Politics of Membership of the Fine Gael Party. Dublin: PSAI Press.

Heidar, Knut, and Jo Saglie. 2003. “Pre-Destined Parties? Organizational Change in Norwegian Political Parties.” Party Politics 9 (2): 219-39.

Howe, Paul, and David Northrup. 2000. Strengthening Canadian Democracy: The Views of Canadians. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Katz, Richard, and Peter Mair. 1995. “Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party.” Party Politics 1 (1): 5-28.

Mair, Peter, and Ingrid van Biezen. 2001. “Party Membership in Twenty European Democracies, 1980- 2000.” Party Politics 7 (1): 7-21.

Noel, S.J.R. 1977. “Political Parties and Elite Accommodation: Interpretations of Canadian Federalism.” In Canadian Federalism: Myth or Reality, 3rd ed., edited by J. Peter Meekison. Toronto: Methuen Press.

Norris, Pippa. 2002. Democratic Phoenix: Political Activism Worldwide. New York: Cambridge University Press. Olson, Mancur. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing. 1991. Report. Ottawa: Supply and Services. Scarrow, Susan E. 1999. “Parties and the Expansion of Direct Democracy: Who Benefits?” Party Politics 5 (3): 341-62.

_____. 2000. “Parties without Members? Party Organizations in a Changing Electoral Environment.” In Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies, edited by Russell J. Dalton and Martin P. Wattenberg. New York: Oxford University Press, 79-101.

Seyd, Patrick. 1999. “New Parties/New Politics? A Case Study of the British Labour Party.” Party Politics 5 (3): 383-405.

Seyd, Patrick, and Paul Whiteley. 1992. Labour’s Grass Roots: The Politics of Labour Party Membership. Oxford: Clarendon.

van Biezen, Ingrid. 2004. “Political Parties as Public Utilities.” Party Politics 10 (6): 701-22.

Ware, Alan. 1996. Political Parties and Party Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Whiteley, Paul, and Patrick Seyd. 2002. High-Intensity Participation: The Dynamics of Party Activism in Britain. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Whiteley, Paul, Patrick Seyd, and Jeremy Richardson. 1994. True Blues: The Politics of Conservative Party Membership. Oxford: Clarendon.

Young, Lisa. 2000. Feminists and Party Politics. Vancouver: University of British Colombia Press.

Young, Lisa, and William Cross. 2002a. “Incentives to Membership in Canadian Political Parties.” Political Research Quarterly 55 (3): 547-69.

_____. 2002b. “The Rise of Plebiscitary Democracy in Canadian Political Parties.” Party Politics 8 (6): 673-99.

Young, Lisa, Anthony Sayers, Harold Jansen, and Munroe Eagles. 2005. “Implications of State Funding for Party Organization.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, September 1-4, Washington, DC.

For immediate distribution – June 13, 2006

Montreal – Political parties serve as bellwethers for the state of democracy. When citizens are actively engaged in parties, democracy flourishes. When they lose interest in participating, the system is imperilled. As a part of its Strengthening Canadian Democracy series, the IRPP is today releasing two studies on the role of political parties in Canada. The first, by Kenneth Carty (University of British Columbia), outlines the function parties have historically served in Canada and their place on the political landscape today. The second, by William Cross (Carleton University) and Lisa Young (University of Calgary), focuses on the critical role played by individual party members and looks at ways to reinvigorate citizens’ membership in Canada’s parties.

Both studies start with the same basic assumptions: an engaged citizenry is a cornerstone of democracy, and political parties are vehicles for public participation in governance. Given these assumptions, the authors see worrying trends on the horizon:

Are Canadian Political Parties Empty Vessels? Membership, Engagement and Policy Capacity, by William Cross and Lisa Young, and The Shifting Place of Political Parties in Canadian Public Life, by Kenneth Carty, can be downloaded for free from www.irpp.org.

-30-

For more information or to request an interview, please contact the IRPP.

To receive the Institute’s monthly newsletter via e-mail, please subscribe to the IRPP e-distribution service by visiting its Web site, at www.irpp.org.

Founded in 1972, the Institute for Research in Public Policy (IRPP.org) is an independent, national, nonprofit organization based in Montreal.