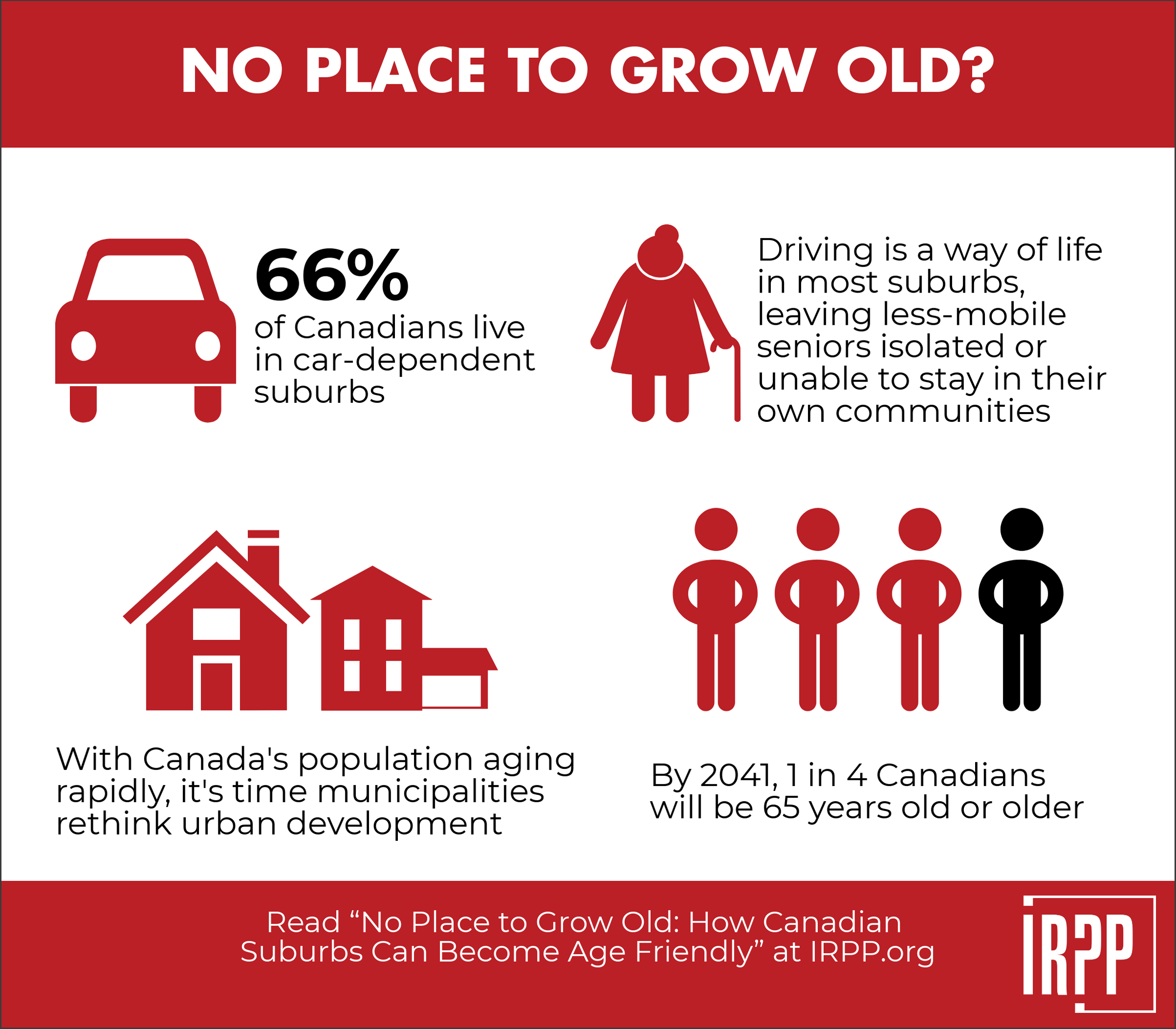

When we celebrated Canada’s centenary in 1967, the country was still relatively young demographically. Only about 7 percent of the population — or 1 person in 14 — was 65 or older. In 2017, as we celebrate the country’s 150th birthday, the demographic picture has changed dramatically, fuelled in large part by the impact of the aging baby boom generation, significant improvements in life expectancy and a recent trend toward smaller families. The Canadian population’s share of seniors is now 16 percent, and there are more seniors than school-age children. Forecasts suggest that that by 2041, 1 in 4 Canadians — more than 10 million — will be eligible to collect Old Age Security. Nearly 1.5 million of them will be over the age of 85.

A recent Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation study1 noted that today’s seniors prefer to “age in place” until their health or economic circumstances force them to relocate to retirement homes or long-term care facilities. Postponing such decisions may be an option for some, but as the number of elderly seniors continues to grow, the question arises of whether Canada’s built environment — the neighbourhoods and transportation networks that define the shape and functions of our cities — can be successfully adapted to meet the needs of an aging population.

The most challenging of these built environments are the car-dependent suburbs constructed since the Second World War. It is fair to say that our current suburbs are no place to grow old.2 Building neighbourhoods where people must drive or be driven to work, school or shopping areas may have worked well for successive generations of households during family-formation years, but as residents age and become less mobile, many lose the ability to drive or cannot afford a car. When amenities such as grocery stores, medical facilities or community centres are too far away to reach on foot, older adults who no longer drive become less active and are at risk of becoming isolated.

Although governments started raising concerns about this issue as early as the 1980s, it appears to have been the concept of age-friendly communities (AFC), introduced by the World Health Organization in 2007, that really captured the attention of decision-makers in Canada. More than 500 municipalities have since committed to becoming age-friendly. Despite this initial enthusiasm, however, the AFC movement has led only to minor physical improvements, such as the addition of park benches, better lighting or clearer signage, and it has thus far failed to generate the scale of public policy intervention needed to bring about significant changes to the built environment.

A 2016 survey of Ontario’s 27 largest municipalities conducted by the Canadian Urban Institute (CUI) suggests that developing the scope and design of frameworks intended to promote age-friendly communities is still very much a work in progress. Although municipally appointed committees and individual departments (for example, public health, social services, and parks and recreation) are successfully employing the AFC model to engage with older adults and to identify concerns and priorities in adjusting how services are delivered to seniors, the concept has yet to be adopted by municipal planning departments. For reasons I will discuss in more detail later, the work being carried out to make communities more age-friendly is still removed from the formal planning and development processes that determine the physical form of urban and suburban neighbourhoods. The challenge of overcoming the entrenched practices that determine how we build our cities should not be underestimated.

A key question, then, is how do we refocus community-planning efforts to encourage the development of age-friendly neighbourhoods that can allow people of all ages to live healthy, productive lives? In this paper, I will examine how we can integrate AFC goals for enhancing the built environment for older adults into mainstream planning and development processes.

The AFC concept was introduced almost 10 years ago by the World Health Organization with funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada. However, the origins of AFC can be traced to the 1970s, when the Canadian government began to invest heavily in research to determine how to provide appropriate care for a generation of older adults who were increasingly living long enough to suffer from heart disease, cancer, diabetes, dementia and other chronic conditions. Work undertaken in collaboration with like-minded researchers in other countries brought to light the importance of measuring the effectiveness of public policy in relation to the determinants of health.3

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research, founded in 2000, saw a need to broaden the base of research, which led to the 2004 formation of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Two years later, the PHAC’s landmark report Healthy Aging in Canada introduced the term “age-friendly” as part of a comprehensive vision of healthy aging, one that acknowledged the role of a well-designed built environment in delaying or mitigating the impact of chronic diseases and disabilities, potentially reducing health care costs and helping postpone or avoid transition to long-term care facilities.4

One of the report’s principal authors, Louise Plouffe, a senior official with the PHAC who was subsequently seconded to the World Health Organization, played a key role in an international consultation initiative led by the organization in 2006 to address the perfect storm in public health of a combination of rapid urbanization and demographic aging. The Global Age-Friendly Cities project, which involved the participation of more than 30 cities around the world (including 4 Canadian ones), led to the 2007 publication of Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide.5

The guide describes the age-friendly city as one that “encourages active ageing by optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age. In practical terms, an age-friendly city adapts its structures and services to be accessible to and inclusive of older people with varying needs and capacities.”6 The guide also provides a policy framework that cities can use to develop local responses in the form of age-friendly checklists on eight topics “covering features of the city’s structures, environment, services and policies that reflect the determinants of active aging”7 (see box 1).

Notably, although a key goal of the AFC initiative is to make a city’s built environment more appealing to older adults and to improve the delivery of services in response to the diverse and ever-changing needs of seniors as they age, five of the eight topics or domains emphasize social and experiential aspects of city living that affect quality of life; only three pertain directly to the built environment (outdoor spaces and buildings, transportation, and housing). Selection of the topics was based on extensive outreach with older adults on five continents and reflects the perceptions and priorities of city dwellers, not necessarily those of professional planners.

In the same year, with financial support from the PHAC, the World Health Organization launched four Canadian pilot projects in Saanich (British Columbia), Portage la Prairie (Manitoba), Sherbrooke (Quebec) and Halifax (Nova Scotia). At this point, a joint task force (federal-provincial-territorial and remote communities) shifted the focus of AFC from age-friendly cities to age-friendly -communities. Although this did not run counter to the substance of the AFC guide, it diverted the focus away from large urban centres, and this meant that an opportunity was lost to enlist the support of Canada’s principal cities in addressing concerns about the country’s age-unfriendly built environment.

Since 2007, the PHAC, provincial ministries, and numerous nonprofit and academic institutions have continued to support the AFC concept. In addition, more than 500 smaller communities and towns and several larger cities across the country have declared their intent to become age-friendly. Nevertheless, tangible changes to the built environment remain elusive.

In a 2011 country-wide scan conducted for the PHAC, the CUI determined that, although communities were successfully engaging with older adults to develop AFC strategies and action plans — mostly through the efforts of social service agencies, health departments, nonprofit organizations and stand-alone volunteer committees — there was little evidence that municipal commitments to create age-friendly communities were leading to substantive changes in land-use policy as formulated in local official plans.

In 2015, the Ontario Seniors’ Secretariat (OSS) funded many local initiatives aimed at enhancing existing, or developing new, older-adult strategies and AFC action plans.8 (Funding to prepare or enhance AFC initiatives has also been made available through the Ontario Trillium Foundation or been supported by upper-tier municipal governments.)

In fall 2016, the CUI surveyed the official plans of the province’s 27 largest municipalities to determine what (if any) progress was being made in using the AFC model to bring about change in the built environment. To be eligible for OSS funding, municipalities had to provide evidence of a council resolution confirming a commitment to become age-friendly.

All but 2 of the 27 cities have made such commitments, not necessarily in connection with a grant application.9 There are 6 (Brantford, Guelph, Hamilton, London, Mississauga and Ottawa) that are using OSS grant money to develop advanced action plans. Another 8 (Ajax, Barrie, Burlington, Kitchener, Markham, Oshawa, Vaughan and Whitby) are using OSS funds to engage their residents in processes that will lead to older-adult strategies or action plans. A further 10 cities (Cambridge, Chatham-Kent, Kingston, Milton, Oakville, St. Catharines, Thunder Bay, Toronto, Waterloo and Windsor) are preparing older-adult strategies or action plans independently with support from regional governments, the Ontario Trillium Foundation and other sources.10

The CUI survey found that none of the 25 cities that committed to becoming age-friendly have to date acknowledged this commitment in their official plans, nor have they identified the need to address the impact of demographic aging as a municipal priority or modified their development approvals process to reflect the goals of the AFC project.

A number of cities express the need to accommodate the housing requirements of their growing populations of seniors or to support aging in place. References to “supportive seniors’ housing” and “senior citizens’ facilities,” however, position seniors as a special-needs group, like people with disabilities, rather than establishing the basis for substantive policy solutions.

The survey found that, although volunteer and external advisory councils or specially constituted not-for-profit organizations still lead the development of AFC strategies, municipal staff in community services, social development, culture and recreation departments are beginning to play a more direct role. Planning departments often participate, but none of the AFC strategies or action plans for seniors are led by planning departments, although planning staff in Brantford, Hamilton, London and Ottawa help promote the integration of AFC initiatives with municipal work plans.

Several municipalities working on second-generation AFC initiatives issue annual reports to their councils detailing specific improvements or renewing commitments to implement improvements by individual departments. For the most part, minor capital improvements have been accommodated in operating budgets, often to comply with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act. This includes matters such as retrofitting public buildings with access ramps, improving street lighting, adding park benches and introducing timing signals on pedestrian crossings.

Overall, it appears that, in its present form, the AFC framework does not lend itself to stimulating the scale of public policy intervention needed to effect significant changes to the built environment. Problems with the AFC model are both conceptual, in that the eight AFC domains do not mesh well with the planning and development process, and practical, in that the drivers for city building are powerful and entrenched and thus make challenging the status quo with new ideas difficult.11 The following sections examine the context, barriers and obstacles that we need to overcome to address these limitations.

Many of the issues and challenges associated with creating age-friendly -communities derive from the fact that 66 percent of the Canadian population lives in some form of suburb.12 Sparked by unprecedented demand for affordable housing in the postwar period, Canada’s cities expanded outward, creating sprawling suburbs filled with low-density, single detached dwellings. They have continued to do so to this day.13

In 1946, Ontario adopted a policy-led approach to urban development with the passage of the province’s first planning act.14 Municipal councils were charged with responsibility for preparing official plans that set expectations for land use and transportation. These plans were implemented through planning tools such as subdivision control and zoning. It became common practice to turn 100-acre farms into single-family subdivisions, creating neighbourhoods separated from all forms of commerce and requiring families to own at least one (but often two or more) cars to maintain their lifestyle.

Although complaints about the effects of suburban sprawl have largely focused on the negative impacts of reliance on the automobile, the list of problems is much longer. It includes the consumption of irreplaceable farmland and encroachment on natural areas; the costly expansion of infrastructure (roads, sewers and water networks); and the unsustainable financial burden on municipalities, which must pay for new -community assets and maintain older ones. In the period 1971-2001, for example, the amount of land consumed by Canadian cities grew at twice the rate of the population.15

The shift from talking about the problems associated with sprawl to committing to do something about them has gained momentum over the past decade or so. There is a growing realization that urban growth patterns are economically, environmentally and practically unsustainable. Provincial, municipal and even private-sector stakeholders acknowledge that a change of direction is urgently needed.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Ontario, which is home to almost 40 percent of Canada’s population. In 2005 and 2006, faced with the mounting costs of supporting ongoing sprawl through municipal subsidies, the Ontario government made two complementary commitments to change how cities are designed and built. First, the province reinforced the Provincial Policy Statement to provide more substantive guidance for municipal planning across the province. Second, with the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, the province introduced a suite of sweeping chang-es applicable to a massive swath of land centred on the Toronto region with the aim of curbing sprawl and promoting more self-sufficient, compact communities designed around mixed-use, walkable neighbourhoods.16 Development industry groups such as the Building Industry and Land Development Association have since begun to work with their members to support these changes, at least in principle.

The main motivation to improve the way that cities are designed and built is largely the need to make better use of scarce infrastructure dollars and a desire to create more vibrant communities, but public health officials have added their voices to the chorus. New evidence on the negative health impacts of suburban sprawl has led to partnerships between public health officials and municipal planners, highlighting the overlap between healthy urban environments and age-friendly communities.

One early effort to provide an analytical policy framework for improving the built environment for seniors was the 1983 publication of a report by the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Although they did not use the term “age-friendly,” the report’s authors noted “the importance of examining seniors’ needs and relating their needs to planning for the general population.”17 In other words, planning for older adults benefits people of all ages. Entitled Towards Community Planning for an Aging Society, the report emphasized the links between the physical form of neighbourhoods and their social composition. Referring to the dominant form of development — single detached dwellings — the report noted that older adults are “disadvantaged both by the separation of uses and by the distance to facilities and services…Mobility becomes more difficult because of either cost or diminishing physical abilities.”18

The report described the importance of designing transportation networks that allow residents to reach services, amenities and workplaces. It also stressed the benefits of designing barrier-free walking and cycling environments. The report relied heavily on research carried out at the University of Toronto as well as growing acceptance of the principles of universal design, which promote accessibility to buildings, products and the built environment for people of all ages and capabilities.19

Perhaps the most prescient finding of the study was that most seniors who wish to stay in their own neighbourhoods have a limited range of housing to choose from. The report also suggested that the aging of the population would inevitably lead to increased demand for home-based delivery of health and social services, emphasizing that seniors were not a homogeneous group and services would need to be modified to accommodate the diversity of Ontario’s older residents. It called for the development of urban design guidelines and a rethink of planning practices to encourage mixed-use, higher-density development. Unfortunately, since seniors represented a relatively small percentage of the population in the 1980s, the study was ahead of its time, and its insights did not influence public policy.

A second useful framework, produced by the Canada Mortgage and Housing -Corporation (CMHC) in 2008, proposed six specific indicators for communities to consider in the context of an aging population: neighbourhood walkability, transportation options, access to services, housing choice, safety and community engagement in civic activities.20 Produced a year after the release of the World Health Organization’s Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide, the CMHC indicators arguably constituted a better fit with the way neighbourhood-scale planning policies are developed than the AFC framework, with its broader focus. The AFC model proved to have more traction, however, particularly with public health departments, social service providers and volunteer committees in small and rural communities. The good work carried out by the CMHC failed to have an immediate impact.

The third framework stemmed from a 2009 initiative led by the Medical Officer of Health for the Region of Peel, a sprawling suburban community immediately west of Toronto. Concerned about the growing incidence of type 2 diabetes in Peel, public health officials pointed to the community’s low-density, car-dependent built environment as a critical factor in this trend.

Collaborating with other public health departments and working with academics from McMaster University, clinicians from St. Michael’s Hospital and a -Toronto planning consultant, the regional municipality developed the Peel Healthy Development Index. While not specifically focused on the needs of older adults, the index addresses many of the same issues raised by Ontario’s Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing and by the CMHC. In particular, it establishes design and transportation standards compatible with the goal of reducing car dependence and improving walkability in suburban neighbourhoods.

The index is currently being integrated into the development review processes of the three municipalities that make up the Region of Peel (Mississauga, Brampton and Caledon), and as such it is expected to influence the content and design of future development projects. Planners will review development applications in light of seven criteria and work with developers to modify proposed designs as required. The criteria are density (and built form), proximity to services and transit, land-use mix, street connectivity, road network and sidewalk characteristics, parking, and issues related to aesthetics and human scale.21 The criteria were specifically calibrated to mesh easily with formal planning processes and lend themselves to the development of policies with measurable, specific standards. The hope is that these criteria will be established as municipal policies that cannot be the subject of appeals to the Ontario Municipal Board.22

The preceding frameworks, although developed at different times and motivated by different factors, help shed light on several important obstacles inherent in the planning and development process (past and present) that must be faced if age-friendly development is to succeed.

The main tool available to municipalities seeking to create an age-friendly built environment is the municipal official plan, which establishes the physical -structure of the community, sets out a vision for development by designating the location and density of land uses, and identifies strategies for implementing council policy. Once development patterns are established, however, change can be introduced only incrementally through intensification or redevelopment.

The first challenge is that, as communities expand outward from their historic cores, new development usually takes place on large, contiguous blocks of former farmland given over to homogeneous land use connected by major roads and highways. This has led to the creation of low-density subdivisions of single detached dwellings, giving way to car-dependent, age-unfriendly communities. When residents of these communities reach a point in their lives when they might consider relocating to a condo or apartment, the lack of housing options available to them contributes to inertia and a propensity to stay put.

A second challenge is that developers tend to specialize in one type of development, such as single detached housing. They are therefore not inclined to introduce the mix of housing types desired by municipal planners, or build retail properties, or engage in other land uses that would create the kind of diverse, attractive environment associated with older communities. As well, even though a developer may have acquired the approvals for a mix of residential units (including townhouses or other higher-density properties) as prescribed in an official plan, builders will often construct single detached dwellings first as these present the lowest risk because they typically sell easily. Since historically there has been no penalty for building at lower-than-approved densities, there has been no guarantee, until recently, that municipal approvals will deliver the desired built form and the densities that would support public transit.23

Research undertaken by the CUI for the Region of Waterloo highlighted several practical barriers to age-friendly development linked to the period in which a community was developed. The research showed that 1950s subdivisions were constructed on a grid that facilitated walking, connected adjacent subdivisions, and provided direct access to shops and schools. Later subdivisions featured curvilinear roads with a wider right of way, as well as cul-de-sacs and loops, which discouraged walking and encouraged driving.

As the design of subdivisions changed, the average size of single detached dwellings increased from 850 square feet in the 1950s, to 1,500 to 2,000 square feet in the 1970s, to 2,000 to 3,000 square feet in the 1990s, to 3,500 square feet today, even though average household size has declined. The result is that many neighbourhoods lack the critical mass of population to support local services and amenities. Instead, residents of newer subdivisions rely on power centres or shopping malls accessible only by car. As the CUI report states, “Driving is a way of life in their neighbourhoods — for getting to work, taking the children to school, socializing and recreation.”24

Analysis by planning staff in the Region of Waterloo (included in the CUI report) also suggests that aging residents in older, walkable neighbourhoods are better able to age at home than those in newer subdivisions, as they do not need to drive everywhere and because smaller houses require less upkeep and have lower operating expenses — a key factor for retired people on fixed incomes. Development in the Region of Peel puts the role and relevance of built form into perspective: in 2011, 48 percent of Mississauga residents aged 65 and over lived in single detached dwellings; in semirural Caledon, the percentage was 88 percent; Brampton was closer to the national average at 59 percent.25

Older adults living in neighbourhoods where a car is needed to undertake the activities of daily living are the first to be affected when they can no longer drive. When large numbers of aging residents living in car-dependent neighbourhoods suffer any loss of mobility (as a result of losing their driver’s licence or no longer having the stamina required to walk more than short distances), not only is their personal quality of life affected but also the situation becomes a public policy concern for the wider community.26 In municipalities such as those in the Region of Peel, most residents depend on driving for personal mobility. Yet the Ministry of Transportation of Ontario estimates that by 2036, 42 percent of residents aged 75 and older in these municipalities will no longer have driver’s licences.27

Pedestrian mobility can also be negatively affected in suburban municipalities when residential subdivisions are approved with sidewalks on only one side of the road or with no sidewalks at all. This can happen because development charges (fees charged to the developer by a municipality) cover only the capital cost of constructing elements of the public realm (such as sidewalks), not maintenance costs. Such designs reduce a municipality’s liability for the cost of maintaining sidewalks or clearing snow.

As the momentum shifts from new growth financed from greenfield subdivision revenues to growth through infill and redevelopment, some municipalities will find it difficult to manage the transition to a mature, built-out state in an age-friendly manner while paying higher costs related to public health and social service delivery.28

The City of Mississauga, once known as the poster child for suburban sprawl, approved its last residential subdivision more than five years ago, and now it must rely on less predictable revenue from infill and redevelopment projects, which tend to be more costly to process and service. Upper-tier municipalities, such as the Region of Peel, and lower-tier municipalities, such as Peel’s Mississauga, must nevertheless continue to repay long-term infrastructure debt while finding budget room to cover increasing soft costs for public health, social ser-vices and long-term care associated with an aging population.

Beyond the obstacles inherent in the planning and development process, the AFC framework faces challenges of its own. Based on its 2011 country-wide scan and informal interviews with planners, the CUI offered the following explanations for why municipal planning departments were not rushing to embrace AFC.

Municipalities and municipal planning departments are under constant pressure to achieve more with fewer resources. In their drive to adopt the latest thinking on what constitutes good planning, planners tend to embrace ideas and practical planning concepts that will help them achieve their goals in the most effective way possible. In the last decade, coinciding with the introduction of the AFC model, municipal planners have come under pressure to address a host of additional complex challenges such as ensuring sustainability and housing affordability and mitigating the impacts of climate change. So, although planners might be sympathetic to the notion of meeting the needs of older adults, the AFC model has proved to be less attractive to planners than other new planning models — including smart growth and new urbanism — that were conceived for the specific purpose of providing solutions to land-use problems.29

The practical consequence of having to balance a desire for continuous improvement in planning practice with the bureaucratic demands of managing rapid urban growth with scarce resources is the need to make choices. Stephen -Golant acknowledged this in a 2014 IRPP publication; he argued that proponents of AFC should avoid promoting “over-ambitious agendas” that “overlap with other housing, service and care programs.”30

There is also the practical reality that planning departments need to maintain their standing and credibility with elected councils, the general public and key stakeholder groups. Department heads therefore choose which themes to champion carefully. To this point, it would appear that the AFC concept has not yet achieved the profile necessary to make it a driving force in the council chamber.

Most concepts or models that promote good planning clearly articulate the scale at which the tools should be applied, but some can also be successfully -implemented at different scales. For instance, the smart-growth model, although originally conceived more than 30 years ago to address growth management issues at the citywide level, has been applied at the neighbourhood level in detailed local plans and integrated into criteria for the review of development applications on a project-by-project basis. Smart growth not only quickly became synonymous with good planning, but it also proved popular with the media and the general public, which probably helped accelerate its integration into formal planning processes.

Another example, from the other end of the scale spectrum, is universal (or inclusive) design, created to promote barrier-free development through application in national and provincial building codes. The concept of universal design is sufficiently clear that in addition to influencing building codes it has also informed citywide municipal standards for the design of streets, parks and other components of the public realm.

In contrast, the AFC domains pertaining to the built environment — outdoor spaces, buildings, transportation and housing — cover a broad range of concerns, from citywide issues (such as enhancing the quality of green and -natural spaces, providing affordable choices for public transit and developing barrier-free housing) to neighbourhood-scale and site-specific considerations (such as ensuring transit stops are well situated, providing clear signage, benches, and curb cuts, and building and maintaining sidewalks). So, although the scope of built–environment topics proposed in the AFC framework is extensive, the potential for these elements to be integrated into formal planning processes is limited, because of a lack of clarity with respect to scale.

A related factor influencing the adoption of new planning concepts is the ease with which they can be integrated into the formal tasks or actions that guide the planning process. Municipal plans are organized in a simple hierarchy in terms of scale that transitions from the general (citywide official plans) to the detailed (neighbourhood-scale secondary plans) to the prescriptive (project development applications). The closer a new concept can be matched to these building blocks, the more likely it is to be adopted. A good example is the Healthy Development Index, described earlier, which was designed to be slotted into the review process for development proposals. The AFC model, on the other hand, was conceived as a tool for a city’s self-assessment across a wide range of factors affecting quality of life for older adults. The AFC goals have considerable merit, but the framework as currently constituted does not mesh well with the building blocks of municipal planning.

When municipal councils make political commitments to create age-friendly municipalities, the breadth and unstructured nature of the eight AFC domains make it difficult for department heads to develop concrete plans for implementing the ideas or to sustain a corporate commitment over the long term. Indeed, AFC goals can intersect with the mandates of many municipal departments as well as external agencies focused on service delivery. Responsibilities for a municipality’s capital investment plans and departmental operating budgets are typically managed separately. The AFC’s built-environment domains blend capital items (for example, investment in low-floor buses) with operating service standards (such as the cleanliness of public toilets), which undermines the importance of the message.

As well, although there may be plenty of healthy debate about how the elements of the AFC framework apply to a community, discussions and action plans related to its implementation are typically conducted independently in stand-alone committees. This means that ideas or proposals developed outside the formal decision-making process present department heads with practical implementation challenges. The long lead time required to translate good ideas into policy commitments, and eventually into concrete, defensible proposals, necessitates ongoing support from one or more department heads. In other words, AFC–related initiatives conceived independently or without departmental support face an uphill battle to gain status in the budget process. This is compounded by the reality that individual municipal departments are in continuous competition for scarce financial resources.

Municipal planning departments are by definition future-oriented. They are charged with the task of preparing policies to guide the evolution of a community while anticipating the impact of incremental changes to the built environment on a project-by-project basis. Although the goal of creating an age-friendly community implies a municipal commitment to achieve a future condition, -AFC older-adult strategies and action plans are heavily focused — with good reason — on improving the quality of life for a community’s current population of seniors through improvements to the delivery of health and social services or the implementation of minor physical enhancements such as extending the walking phase at selected pedestrian crossings.

The AFC domains that relate to the physical environment focus to a significant extent on improving current conditions that are within the purview of -operations managers (for example, improving bus driver training and standards for sidewalk maintenance). From a policy perspective, however, this undercuts such worthy goals as designing new, or retrofitting existing, neighbourhoods in ways that could be considered age-friendly.

The AFC movement is well intentioned and has facilitated many valuable -initiatives that affect the delivery of health and social services, modify operations and make minor physical improvements in the public realm. Nevertheless, as currently configured, the AFC model does not lend itself to the scale of public policy intervention needed to bring about fundamental changes to the built environment. For AFC to have the desired impact on adapting the existing built environment and to ensure that future development takes the needs of seniors into account, the notion of healthy aging must be embedded in mainstream planning practice. As momentum builds to transform the model for how cities are designed and built in Ontario, there is an opportunity to integrate the goal of creating age-friendly communities into provincial land-use policy. Harnessing the forces of the demographic shift that is taking place can both strengthen public policy and leverage the power of the marketplace to achieve positive change in the built environment. The following proposals suggest ways to integrate AFC objectives into mainstream planning.

There are two interrelated ways that Ontario can signal its desire to design and build communities in a manner compatible with age-friendly development. The first is to make amendments to provincial land-use policy; the second is to reinforce the impact of the amendments by actively linking an existing commitment to promote the AFC model with provincial land-use policy.

The first step would be to incorporate the vision and rationale for age-friendly development into both the Provincial Policy Statement (PPS) and the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. Acknowledging the unprecedented scale and impact of the demographic shift under way in Ontario would complement the province’s current planning agenda while providing a substantive basis for the government to respond positively to population aging in other areas.

Planning and development in Ontario is a policy-led process. The PPS establishes the government’s policies on land-use planning. It provides “clear policy -direction on land-use planning to promote strong communities, a strong economy, and a clean and healthy environment.”31 Municipal official plans are required to be consistent with the policies of the PPS.

In 2005, the province passed the Places to Grow Act, which provided the authority for the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. The Greater Golden Horseshoe is a vast area covering more than 30,000 square kilometres in southern Ontario. It includes 22 of the province’s 27 largest cities. The plan came into effect in 2006 and is currently undergoing its 10-year review. In keeping with the province’s desire to make local planning more effective, the plan states that municipal policies “shall conform with” the growth plan’s policies — a more prescriptive requirement that increases the certainty that public policy goals can be achieved.

Although it has traditionally taken years for land-use policy changes to make a difference on the ground, the impact of requiring municipal plans to conform to provincial policy, combined with the effects of a variety of other adjustments to provincial land-use policy, has the potential to accelerate the pace of change. Proposed amendments to the growth plan set density targets more in line with development that encourages walking and public transit use and make it harder to continue the relentless outward spread of car-dependent subdivisions.

Another key change is a provision that allows municipalities to establish minimum densities for development. In the past, developers could build at densities lower than those that had been approved, substituting easy-to-sell single detached houses for stacked townhouses or low-rise or mid-rise apartments — building types generally more suitable for older adults. The change gives municipalities the ability to protect their investment in piped services sized to accommodate higher densities by requiring developers to construct the range of housing types agreed to when the plans were approved.

Introducing AFC-compatible policy language into the PPS and the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe would signal to municipalities and to the development community that the province wishes to make AFC a land-use priority. “Strong” communities (the current wording of the PPS) can also be age-friendly communities, designed and built for the benefit of everyone.

The Ontario government can reinforce its efforts in this regard by linking them more explicitly to other initiatives in the health care area. Indeed, the potential impact of population aging was influencing Ontario’s health care policies as early as 1982, when the government formed the Ontario Seniors’ Secretariat. With people living longer, health care practitioners began seeking ways to help older adults enjoy more years of healthy life, consistent with healthy aging — a core AFC concept. In 2009, a consulting study carried out for the North East Local Health Integration Network called attention to a looming crisis in long-term care.32 The study pointed out that the lack of appropriate housing options for a growing population of seniors no longer able to cope with living in single detached housing meant that the traditional practice of relying on long-term care beds to accommodate this demographic was both physically and financially unsustainable. Although the study focused on extreme market conditions in northern Ontario, its findings prompted a major reshuffling of priorities within the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care as officials made the connection between population aging, health care trends and the lack of appropriate housing options for seniors province-wide.

In 2010, prompted in part by the increasingly high cost of treating the elderly in hospital settings, the government adopted its aging-at-home strategy, turning a long-standing practice into formal policy. The AFC concept, which had just emerged from its pilot phase, was embraced by the OSS as a way to link health care priorities with a community’s physical built environment. In 2013, the OSS published Finding the Right Fit: Age-Friendly Community Planning,33 followed in 2015 by a program of grants to fund community efforts to develop AFC older-adult strategies and action plans.

As I have noted, although the AFC movement in Ontario’s largest cities appears to be flourishing on many fronts, it needs to be connected to another urgent provincial priority: reforming the way that cities are planned and built.

Although most of Ontario’s largest cities have declared their commitment to become age-friendly, none has yet taken the basic step of stating this commitment in the vision statements of their official plans. Members of the Large Urban Mayors’ Caucus of Ontario (LUMCO) of the Association of Municipalities of -Ontario — representing the 27 cities surveyed by CUI — work collaboratively on a variety of policy issues. Given that 25 of the 27 cities have already made a formal commitment to become age-friendly, the LUMCO is in a position to encourage its members to take the next logical step, which is to integrate that commitment into the community visions expressed in their official plans.

Official plans must be updated every five years, so the opportunity to present AFC as a municipal land-use priority would arise relatively quickly. Leadership of LUMCO cities would likely encourage smaller municipalities in the province to follow suit.

Introducing appropriate AFC policies into an official plan provides an opportunity to apply the concept of AFC at the three scales that best match the formal planning and development process: the citywide scale, the neighbourhood scale or secondary plan, and the scale of individual properties reviewed through the application process.

Amending the vision and strategy sections of official plans to acknowledge the impact of demographic change would create an additional, powerful impetus for rethinking development patterns with an emphasis on reurbanization over outward expansion. The AFC lens would reinforce citywide goals for urban design, neighbourhood walkability, and proximity to community services, amenities and public transit.

An AFC-motivated official plan would also establish the policy framework for investments and plans implemented by other departments, such as transportation, parks and recreation, and public housing. Instituting citywide age–friendly standards would both affect new infrastructure construction and inform the retrofitting and replacement of older infrastructure.

Land-use and transportation policies for neighbourhoods are established in detailed secondary plans, which need to be reviewed from time to time to ensure they are still relevant. Since it is unrealistic to assume that all neighbourhoods can be worked on at once, planning departments typically select areas for review where the need for a new approach is most urgent.

Once the citywide plan has acknowledged that creating age-friendly communities is a priority and that demographic shifts should drive change, municipalities could select areas for review that meet certain criteria related to the AFC concept — beginning with car-dependent neighbourhoods where a significant percentage of residents live in single detached dwellings and are aged 55 and older. Over a 10-to-20-year period, most middle-aged residents will become senior citizens. It takes time to effect physical change, so identifying areas for priority action increases the likelihood that these residents will be able to age successfully in place.

An AFC-compatible secondary plan review presents two complementary opportunities. The first is to systematically introduce a policy basis for incremental changes to the built environment that, supported by investments authorized in capital and operating budgets, could be accommodated as part of normal renewal. These changes could include, but go beyond, the rebuilding of sidewalks, the redesign of pedestrian crossings, the improvement of lighting, and the addition of benches and accessible public washrooms.

The second opportunity is to target sites that have the potential for age-friendly redevelopment. Neighbourhoods that have seen a decrease in population following the departure of children and an increase in single-occupant households would benefit from a revitalization of amenities and the development of more age-appropriate housing. As illustrated by the vignettes presented in the appendix, such development attracts people of all ages, not just seniors.

Having established AFC-compatible policy guidance at both the citywide and the neighbourhood levels so that age-friendly policies become synonymous with good planning, an important next step is to adjust and adapt the way that development applications are reviewed. When municipal departments and stand-alone agencies such as public health and social services are all independently promoting an age-friendly agenda, the cumulative benefits can be significant. The seamless integration of age-friendly policies with other priorities — such as promoting energy efficiency and active transportation — must also be conducted in collaboration with the private sector (developers, builders and their consultants) in order to mobilize the power of the marketplace to achieve these important goals.

There will never be a better time than the present to mobilize stakeholders engaged in the design and building of our cities — in particular, those working to develop new suburbs and improve older ones — to make an age-friendly built environment a reality.

The Ontario government continues to strengthen the statutes, policies and -regulations that steer planning and development toward a more sustainable future. Integrating the goals of AFC into these policies will in turn facilitate the integration of AFC principles into the planning process. Commenting on new provincial policy that supports more compact, pedestrian-friendly development, Kevin Eby writes, “The suburbs of the future are to be neighbourhoods that contain a mix of housing types and provide for the needs of residents at all stages of their lives.”34 The provincial government has signalled its strong support for age-friendly communities through the work of the OSS, as well as its firm commitment to health care policies that support healthy aging and aging at home. The arguments presented in this paper highlight many reasons why these two important policy initiatives should be linked.

The province’s departments of public health are becoming increasingly vocal about the connection between healthy aging and the built environment. Their leadership has already demonstrated how collaboration among public and private stakeholders can influence approaches to planning policy and practice. The Region of Peel’s Healthy Development Index, created in partnership with adjacent public health departments, provides an excellent model for accelerating the pace of change through collaboration.35

At the municipal level, there is the LUMCO of the Association of Municipalities of Ontario. It represents Ontario’s 27 largest cities, most of which have already passed council resolutions in support of the AFC model. The LUMCO is in a position to support the essential step of introducing AFC-compatible language into the policies and process of municipal planning.

To be useful, public policy needs to be implemented successfully. In order to capture the imagination of the older adults who stand to benefit from age-friendly development practices, municipal planners and their developer colleagues need to seek out and deliver compelling examples of age-friendly development that will benefit people, and customers, of all ages.

The neighbourhood of Port Credit, in the City of Mississauga, is a successful example of a comprehensive redevelopment of a brownfield site — the former St. Lawrence Starch property. Over a 15-year period, the developer built townhouses, mid-rise condominiums and, more recently, a retirement residence. The site was large enough to allow for the construction of a grid of local streets with access to an arterial road offering retail and other amenities. It is also within walking distance of a commuter rail station. Careful marketing on the part of the developer has prompted numerous residents to transition from townhouse to mid-rise to the retirement residence.

Between 2001 and 2011 (the most recent period for which census information is available), the neighbourhood saw increases in overall population in four age cohorts: 45 to 54, 55 to 64, 65 to 74, and 75 and older. The developer indicates that a majority of buyers have relocated from low-density neighbourhoods in the area. This brownfield redevelopment is a model for high-impact age-friendly development.

Don Mills, in the City of Toronto, was one of Canada’s first car-oriented suburban subdivisions. It has undergone significant change since it was first -developed, in the 1950s. The initial residents of Don Mills were typical 1950s -suburbanites — they depended on cars to access workplaces and shopping areas and to undertake other activities. An outdoor shopping centre was part of the original development. Most of the neighbourhood’s children were of a similar age, and when they began to reach adulthood and move away, the shopping centre became less viable. In keeping with the style of the time, the owner redeveloped the property as an enclosed mall — over the protests of residents.

About 20 years later, the mall was once again converted into an outdoor shopping centre with internal streets. This change was unpopular with older residents, who had come to depend on the enclosed facility as a site for exercise walking during the winter months. Despite their bitter opposition, the developer prevailed. However, when the project was completed, local residents were among the first to take advantage of the mid-rise condominiums (similar in scale to those in Port Credit) that were built around the periphery of the mall. The Shops at Don Mills project has permitted older residents to relocate to age-appropriate housing while generating business for the newly built open plaza.

Community hubs concentrate a mix of land uses to support development of a wide range of community services, retail and other amenities. A traditional form of community hub is a main shopping street that already has a successful business–improvement area (BIA). The BIA concept was invented in Toronto more than 40 years ago. In New York City, community leaders have taken it a step further by identifying key shopping streets as aging-improvement areas (AIAs),37 combining the drive and organizational skills of local businesses with AFC goals. In designated AIAs, urban designers, marketing specialists and community service providers work to ensure that buildings and services are accessible and attractive to people of all ages. AIAs give local shopping streets a competitive edge.

Research conducted by the Canadian Urban Institute for the Region of Waterloo identifies two good examples of a shopping street that has become a community hub: Broadway, in the Kitsilano suburb of Vancouver, British Columbia; and a North Toronto neighbourhood focused on Yonge Street. With thriving BIAs already in place, these two areas have excellent potential as AIAs. Both have seen the development of numerous of mixed-use mid-rise projects over the past 15 years. Although not explicitly planned as age-friendly projects, both focus on creating a high-quality public realm through zoning that encourages a mix of community-oriented uses and street grids that facilitate walking and easy access to public transit. These two community hubs have proven attractive to empty nesters as well as young families who can afford to rent or own condos.

Glenn Miller is a senior associate with the Canadian Urban Institute (CUI) in Toronto. A fellow of the Canadian Institute of Planners, he was editor of the Ontario Planning Journal (1986-2011). He led CUI’s research reports on aging for the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (with SHS Consulting) and the Region of Waterloo (with Philippa Campsie). He is also a member of the City of Toronto’s Seniors Accountability Table.

IRPP Insight is an occasional publication consisting of concise policy analyses or critiques on timely topics by experts in the field. This publication is part of the Faces of Aging research program under the direction of Nicole F. Bernier and France St-Hilaire. All publications are available on our website at irpp.org. If you have questions about our publications, please contact irpp@nullirpp.org.

To cite this study: Glenn Miller, No Place to Grow Old: How Canadian Suburbs Can Become Age-Friendly. IRPP Insight 14 (March 2017). Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IRPP or its Board of Directors.

For media inquiries, please contact Shirley Cardenas (514) 787-0737 or scardenas@nullirpp.org.

Copyright belongs to the IRPP.

To order or request permission to reprint, contact the IRPP at irpp@nullirpp.org

Date of publication: March 2017

ISSN 2291-7748 (Online)

ISBN 978-0-88645-365-7 (Online)

Montréal – Face au vieillissement rapide de la population, les villes doivent réorienter leurs efforts de planification pour prendre en compte les effets d’un étalement urbain qui favorise depuis des décennies l’usage de l’automobile et isole en même temps les aînés à faible mobilité, soutient l’auteur d’une nouvelle publication de l’Institut de recherche en politiques publiques.

Les aînés préfèrent aujourd’hui « vieillir chez soi », mais la plupart de ceux qui souhaitent rester dans leur quartier disposent de possibilités de logement très limitées, si bien que « nos banlieues sont loin d’être le meilleur endroit où vieillir », observe Glenn Miller, associé principal de l’Institut urbain du Canada de Toronto.

Même si plus de 500 villes ont annoncé leur intention de se joindre aux « collectivités-amies des aînés », ce mouvement n’a produit jusqu’ici que des initiatives mineures : ajout de bancs de parc, éclairage amélioré ou meilleure signalisation. Mais aucune n’a encore pris des mesures fondamentales comme l’adaptation des plans d’aménagement.

Or, en modifiant les politiques provinciales de sorte que la planification adaptée aux aînés devienne une priorité des villes, on compléterait d’autres mesures provinciales axées sur des lotissements plus denses et des aménagements piétonniers qui favorisent le « vieillir chez soi ». On inciterait également les villes à prendre des moyens concrets pour intégrer le concept de « collectivités-amies des aînés » à leurs processus de planification et de développement.

Les ministères chargés de la santé publique sont par ailleurs de plus en plus conscients du lien entre un vieillissement en santé et l’environnement bâti. « L’objectif principal du développement de collectivités-amies des aînés, estime l’auteur, est d’offrir des types d’habitation qui répondent aux besoins des résidents de tous âges et de créer des quartiers attirants, qui sont propices à la marche et permettent d’accéder facilement aux services. »

Avec le vieillissement de la population, il sera essentiel de coordonner les initiatives provinciales et municipales en vue d’adapter l’aménagement des banlieues et les réseaux de transport aux besoins des aînés.

On peut télécharger la publication No Place to Grow Old: How Canadian Suburbs Can Become Age Friendly, de Glenn Miller, sur le site de l’Institut (irpp.org/fr).

-30-

L’Institut de recherche en politiques publiques est un organisme canadien indépendant, bilingue et sans but lucratif, basé à Montréal. Pour être tenu au courant de ses activités, veuillez-vous abonner à son infolettre.

Renseignements : Shirley Cardenas tél. : 514 594-6877 scardenas@nullirpp.org

For many of us, Canada’s centenary celebrations seem like they happened yesterday. How did 50 years go by so quickly? As we prepare for our 150th anniversary, the demographic reality is that there are now more seniors than school-aged children in our population. Twenty-five years from now, one-quarter of us will be collecting old age security.

Although this has predictable implications for the economy and health care costs, we face another challenge: for decades we have been building car-dependent suburbs where residents have to drive or be driven to work, school or shopping. This worked well for growing families, but as people age and become less mobile, many lose the ability to drive or afford a car. When grocery stores, medical facilities and community centres are too far away to reach on foot, seniors without a car become less active and are at risk of becoming isolated. Forecasts suggest that by 2036, more than 40 per cent of people living in car-dependent suburbs surrounding Toronto will no longer have a driver’s licence.

What can be done to solve this problem? The good news is that hundreds of Canadian municipalities have signed on to become “age-friendly,” a concept introduced in Canada as a World Health Organization pilot a decade ago. In Ontario, nearly all of the province’s largest cities have declared their intention to become age-friendly. Some, such as Ottawa, Toronto, London and Hamilton, with support from the Ontario Seniors Secretariat (now the Ministry of Seniors Affairs), have already earned the WHO’s coveted age-friendly designation. But this recognition is renewable every three years and entails more than the relatively minor improvements (such as more park benches, better lighting and signage) we have seen so far. Cities can’t rest on their laurels.

One of the critical areas for improvement is to make the connection between “age-friendly” and land-use planning. Research by the Canadian Urban Institute finds that none of the larger Ontario cities pursuing the path to become age friendly has yet taken the basic step of amending its official plans to reflect that commitment.

Research confirms that most of us want to age at home, in familiar surroundings, where we have friends and know our neighbours. But unless there are “push factors” such as ill health, or “pull factors” such as the desire to move to more vibrant surroundings, most of us stay put. This inertia is exacerbated in low-density suburbs filled with single detached housing because these places offer few housing options for anyone looking to move.

In a publication just released by the Institute for Research on Public Policy, I detail the following opportunities:

A British gerontologist once stated, “Design for the young and you exclude the old; design for the old and you include everybody.” There are many reasons to build on the progress being made to create age-friendly communities. Preserving quality of life for seniors living in Canada’s suburbs seems like a good place to start.

Glenn Miller is a senior associate with the Canadian Urban Institute in Toronto. In addition to leading the CUI’s research on aging issues, he is a member of the City of Toronto’s Seniors Accountability Table.