Imagine it’s 1997. After four years of unprecedented spending restraint, the health care system is in disarray. Wait times are long, morale is low, and public confidence is in the tank. The economy has recovered, and government fiscal circumstances have turned the corner. It’s time to reinvest in health care. Total annual health care spending (both public and private) is $70 billion. How much new money will it take to shorten wait times, update technology, and improve safety and quality?

Let’s start with $10 billion per year — a 14 percent boost. Would that do the trick? Probably not; that would merely restore spending to where it would have been had there been no restraint in the mid-1990s. How about $20 billion, or 29 percent? That would easily surpass the previous high-water mark. But, just to be sure, and because health care is so fundamental, let’s up the bidding to $30 billion more annually — a 42 percent increase. That, surely, would be an embarrassment of riches.

But since public health care forms part of our basic identity and Tommy Douglas is the greatest Canadian ever, let’s go for the gold and double health care spending, in real terms, by 2011. That would surely give us the Ferrari of health systems, the best of the best. Could we even spend that much?

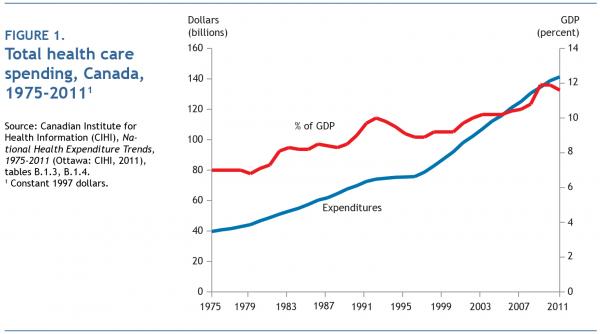

We did — we doubled real health care spending in 14 years (figure 1). Behold the results. Serious access, safety, quality and fairness problems remain. The spend-to-greatness experiment failed. And now, following the fiscal fallout from the 2007-08 worldwide financial crisis, governments once again want to bend the cost curve — down, not up. The new mantras are “value for money,” “appropriateness” and “waste reduction.”

Good luck to ’em. Costs rise, and health care absorbs all money made available to it, because the system is designed that way. It will take blood and guts to redesign it. The good news is that there is nothing inevitable about either the level or the rate of increase in health care spending.1 Bending the cost curve is technically simple: governments can decide to allocate less money, just as they did in the mid-1990s. Newfoundland has budgeted a 3 percent decrease in spending for 2013-14. The combined provincial estimates call for a 2 percent increase, the smallest since the mid-1990s. Consider the cost curve already bent. The real challenge is to bend it permanently while making the system perform better. That condition is unlikely to be met without fundamental changes in accountability for performance and value.

Scientific evidence, quality improvement, sound policy, thoughtful incentives, cultural change and political courage, judiciously applied, are the key ingredients of a successful transition to a lower-cost future. The real issue is not how much we spend or even the rate of growth we attain; it is what health value we achieve for what we spend. The bad news is that there are few painless and easy-to-implement measures that would significantly and permanently alter spending growth patterns. That is why governments always flinch unless and until there is literally no alternative. They do not help their cause by constantly churning deputy ministers and erasing valuable parts of their corporate memory.2

Many argue that health care spending trajectories are inherently unsustainable,3 and that effective restraint would be difficult because of an aging population. On the latter contention, the research is clear: population aging occurs slowly, and on its own it drives spending increases only to the tune of about 1 percent per year.4 We would reformulate the former contention because there is no objective definition of “sustainability,” and there are irreconcilable disagreements about whether governments have a revenue problem or an expenditure problem (or both). Our concern about health care spending is that at the margins it delivers poor value for money. Ineffective spending therefore constitutes a major opportunity cost for governments and for society as a whole. Only when we develop policies and practices that ensure we spend health dollars well will we be able to have a more thoughtful conversation about whether we spend enough.

Four main factors drive health care spending: the system’s architecture; culture, both within health care and throughout society; health human resource policies and practices; and prices.

Paul Batalden famously declared that “every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.”5 Our financing arrangements and delivery systems are designed to drive up costs. Under fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement, physician incomes rise with volume of services delivered. Each additional doctor-patient encounter increases the likelihood of more diagnostic tests, referrals or procedures. By contrast, provider restraint reduces provider incomes. Moreover, Canadian FFS agreements create incentives to treat problems in isolation rather than as a whole. The all-encompassing fee code for “partial examinations” pays the same amount for a three-minute visit to obtain a prescription renewal as it does for an hour-long consultation to address a frail elderly patient’s multiple complaints.

Similar logic pervades the entire system. Health care equates productivity with service volumes, not health outcomes. Individuals and organizations get paid regardless of whether the services they deliver are appropriate or inappropriate, high quality or mediocre. In the US Medicare system for the elderly, per capita spending is three times higher in some regions than in others, with no difference in outcomes or patient satisfaction. Elliott Fisher and colleagues at Dartmouth College have demonstrated that most of this variation is explained by supply (the number of doctors and hospital beds) and by practice preferences that depart from the best available scientific evidence.6 Canada has barely begun to discuss appropriateness, and it rarely acts on persuasive evidence that excess utilization is not simply useless but often harmful. A recent study estimated that at current rates of CT scanning, 15,000 Americans will die annually from exposure to radiation.7 Canadian research has carefully documented overuse of surveillance imaging following breast cancer.8

An unjustifiable variation in intervention rates is an important sign of a quality problem. Yet there is little curiosity in Canada about why rates vary so widely, the consequences of the variation and which rate is more consistent with better outcomes. Physicians frequently claim that patient demand and preferences drive differences in rates. This is a convenient untruth; patients tend to do what their doctors urge them to do.9

There is almost no active management of clinical practice in Canada. Clinical autonomy is more strongly rooted here than in most other developed countries. Integrated US systems widely described as high performers — Group Health Cooperative in Washington State, Intermountain Healthcare in Utah, Kaiser Permanente — measure, monitor and manage clinical care as core operating imperatives. Like all quality-oriented organizations, they standardize work wherever possible and have automated information systems to inform trajectories of care. They identify outlier practices and support doctors and facilities to improve their performance. Despite some promising innovations across Canada, medicine remains for the most part a cottage industry of small businesses in which neither payers (governments) nor providers adequately scrutinize quality, health outcomes or resource-consumption patterns. And still governments wonder why it’s hard to contain costs.

Teachers have to take jobs where the students are, but doctors can pretty much practise wherever they like, regardless of need. Underserviced geographic areas are a perpetual source of angst for the public and for policy-makers. The conversation conveniently ignores overserviced areas and misses the irony that the failure to deal with that problem exacerbates shortages elsewhere. Physicians cluster in attractive urban areas with healthy populations and overlook pressing needs both within and outside our cities. Interestingly, it appears that the percentage of the population that reports not having a regular family doctor is not related to the doctor-to-population ratio.10 The BC Supreme Court struck down the government’s plan to pay physicians in overserviced areas a reduced percentage of the fee code on Charter of Rights grounds. By contrast, the New Brunswick Court of Appeal upheld a regional health authority’s right to limit the number of physician slots in various specialties. Quebec has found a way through regional medical staffing plans to limit practice locations for many years.11

This competing jurisprudence suggests that whether governments can mandate a reasonable geographic distribution of doctors remains an open legal question. No case of this type has yet been referred to or adjudicated by the Supreme Court of Canada. There are 84 percent more seats in medical schools than in 1997. Unless the tsunami of new graduates spreads out from the metropolitan areas, we will face a major surge in supply-induced demand.

The public has been thoroughly co-opted in the battle against prudence and restraint, especially when it comes to pharmaceuticals. To a greater extent than anywhere else in the system, provincial drug formularies make transparent recommendations based on sound effectiveness and cost-effectiveness assessments. Very expensive treatments that will yield at best a few weeks or months of low-quality life rarely make the cut. Most formularies initially rejected public funding for beta interferon for multiple sclerosis (MS) patients on cost-effectiveness grounds, yet every government reversed course in response to intense lobbying. A recent review in British Columbia showed that among patients with relapsing-remitting MS, the drug had no effect on the progression of their disease.12 Such capitulations inspire other well-organized (and sometimes industry-funded) interest groups to pressure governments to pay enormous sums for long-shot therapies that pass no rational test of cost-effectiveness. Politicians who rue this emotional blackmail when in government become ardent practitioners of the dark art when in opposition. One could argue that such generosity is a fitting response to the will of the people — except that the people also want lower taxes, lower tuition fees and better roads. Or one might approach the problem differently: in the case of high-cost drugs, governments could, at a minimum, track and report what happens to the patients who receive them. (The results would sometimes support reconsideration of coverage.) We’re just getting started, and Canada could pursue these measures far more vigorously.13

Successful commercial enterprises are obsessed by the search for the lowest-cost option for achieving the desired result. In health care, funding policies and budgeting systems are designed to promote and entrench higher-cost service delivery and treatment options. When a frail elderly person walks into an emergency room with an impending heart attack, the system is instantly primed to spend tens of thousands of dollars for tests, surgery and a hospital stay. However, that is often the same person who languished at home, mildly depressed, isolated, physically inactive and malnourished — someone for whom the system refused to spend a few hundred dollars a month on home care to prevent the catastrophe that ended up in the emergency room and the operating room. These types of problems have been identified for decades, yet to our knowledge, no jurisdiction has organized its budget envelope to create a natural incentive to seek the most cost-effective option.

In the prevailing zeitgeist, just because you feel fine doesn’t mean you’re well. More and more conditions have become medicalized, which creates more and more grist for the health care mill. If you’re not diagnosed, it’s because you haven’t looked hard enough. Recent examples include erectile dysfunction, depression (at the same time promoted in media ads encouraging people to buy over-the-counter antidepressants and underdiagnosed in populations such as the elderly), autism-spectrum disorder, attention-deficit disorder, prediabetes, osteoporosis and other manifestations of human imperfection. “Fully normal” has become an exotic and rare nondiagnosis. Not coincidentally, the remedy for the expanded diagnoses is more often than not a drug. There is a great deal of money to be made by pathologizing new territory,14 and there is significant overdiagnosis associated with tests like mammography and prostate cancer screening.15 The emergence of new diseases or pseudodiseases without the prospect of a cure will chiefly serve to produce more anxiety — a phenomenon certain to multiply with each new form of predictive genetic testing.

For this we can thank the twentieth century, which transformed health care from a largely ineffective, unscientific and palliative enterprise to a highly specialized juggernaut with infinitely more capacity to diagnose, cure and enhance. Our culture privileges technology-intensive expertise and procedures over more traditional forms of care. Procedural specialists (orthopaedic surgeons, ophthalmologists) earn more than cognitive specialists (geriatricians, psychiatrists). Many clinicians have lost the arts of listening, touching and observing. Primary care physicians defer to lab tests, imaging and specialists to make a diagnosis. They have lost their clinical confidence because they have been socialized to believe that the “real work” of the system gets done by specialists and machines. If you install it, they will come. The result is an avalanche of dubious use. To cite a few examples:

Prevailing health human resources (hhr) policies and practices in Canada thwart innovation and increase costs. The incentives under which health professionals work strongly influence the organization, delivery and cost of services, and they are among the most resistant to change.

Historically, professional identity has been intimately identified with scope of practice. Professions’ tendency to claim exclusive domain over specific activities has persisted despite legislation that in theory makes competency rather than identity the basis for determining what one is able to do. It takes a long time to make even modest changes in scope. The results are stalled careers, needlessly long and expensive retooling, and high service costs.

Similarly, there has been an explosion of credential increases during the past 20 years. The most far-reaching has been the requirement for new registered nurses to have baccalaureate degrees. More recently, the fields of occupational and physical therapy have all but completed the transition to a master’s-level degree entry requirement. Pharmacy is moving toward having the PharmD as its entry credential. Enhanced credentials require extra time to produce graduates, and they create barriers to entry for lower-income groups. Perhaps even more worrisome, they may further fragment the system as students spend more time in parallel educational streams and graduate-level training programs that promote distinct theories of health. When training programs lengthen and become more expensive to operate, there is at least a temporary drop in the number of graduates they produce, which exacerbates labour shortages and drives up wages. It is hardly a coincidence that the interprovincial bidding wars that dramatically pushed up nurses’ pay followed soon after the transition was made to requiring that entrants to the profession be degree holders.

Diverse forms of payment also get in the way of progress. The FFS system encourages short primary care visits and quick referrals of more time-consuming cases to specialists. Efficiently performed routine work is more lucrative than complex problem solving, and this drives specialists to work at the lower end of their capabilities. They may chafe at dealing with problems that should have been addressed in primary care, but this avoidable busywork is a source of easy money. The most lucrative physician-owned private clinics focus on routine, low-risk day surgery procedures (such as cataract surgery and simple orthopaedic procedures) and technology-intensive diagnostics. Paying doctors for discrete acts that they personally perform discourages them from delegating practice terrain to competent colleagues, such as advanced practice nurses. Sometimes the victims of turf-protecting behaviour become the perpetrators: registered nursing regulatory bodies have battled to restrict the scope of work of licensed practical nurses.

Many HHR standards and policies became entrenched before the health sector achieved greater insight into the factors that promote quality improvement. The system is left with a legacy of mandated requirements that increase costs but produce few, if any, benefits. Examples include regulations requiring a specific number of nursing hours per resident, and fixed ratios of personnel. Mandatory staffing levels appear to be a blunt instrument for ensuring quality.17 When they become part of collective agreements, legislation and accreditation standards, they are nearly impossible to jettison, even when obsolete. Contemporary quality improvement theory and practice emphasize the processes of care and no longer put much stock in inflexible standards.

Health care is famous for contradicting the normal economic laws of innovation. Computers, bicycles and smart phones get cheaper as they get better. Health care technology gets marginally better and vastly more expensive. Most new drugs are no better than old ones, yet they always cost much more. The next generation of scanners will certainly produce better pictures, and they will cost a great deal. But will they produce better health outcomes, and does that, in the end, matter to the clinicians who requisition them or the charitable foundations, health care organizations and governments that buy them?

Costs are price times quantity. Reducing either will alleviate pressure on total costs, and reducing both will compound the benefit. Canadian health policy has rarely addressed price, and as a result, Canada’s health care system fares poorly in international comparisons of value for money. For example, our generic drug prices have been extremely high by world standards. Ontario cut them in half by law in 2010. Despite the wailing of pharmacists and manufacturers, the sky did not fall, and neither had to close shop. This long-overdue move spawned imitations across the country, which, over time, will save billions of dollars. The Council of the Federation agreed in 2013 to set the price paid for six widely used generics at just 18 percent of the brand-name price. Cataract surgery used to be a lengthy procedure that involved an in-patient stay. Today it is a 15-minute day surgery procedure. Yet the price has dropped only moderately, and ophthalmologists who restrict their practice to this routine, low-risk, simple operation often bill over a million dollars a year. Their colleagues who deal with complex eye disorders bill a third or a half of that. The income staple of gastroenterologists is threading scopes through various orifices. Well-trained nurses do this work in the US and the UK, reducing the cost. Proposals to replicate these successes in Canada are at least a decade old.18

Many factors conspire to drive health care costs up. It will take nothing less than a sustained, carefully designed, multipronged strategy to avoid reliving the experience of the past 20 years. Many elements need to change: culture, incentives, education, structures, relationships, accountability, transparency. The first step has to be a shared commitment to improving value for money based on recognition that the system just isn’t good enough. There must be a similar willingness to leave the comfort zone of conventional practice at all levels — governmental, organizational and front-line practice. Some important changes should yield tangible benefits in a relatively short time; others will take much longer. There is no sure fire blueprint for success, and there will be surges and setbacks along the way. While we may not know exactly what has to come, we do know what has to go. Some structures have to be bulldozed and some ground has to be decontaminated if we are to build a better future. Here are some essential steps.

First, and most important, we must acknowledge that bending the needs curve is the best way to bend the cost curve. Every structure and incentive should be aimed at preventing or postponing avoidable health breakdown. Most of the preventable burden of disease results from social and economic conditions that are beyond the purview of health care to change. Therefore, the focus of health care should be on secondary prevention — preventing conditions from getting worse. The system does a woeful job of managing the chronic conditions that account for up to two-thirds of all spending. It puts the elderly at risk of debilitating and costly health breakdown by denying them help until a crisis occurs. Canadian medicare has effectively deinsured home support and community rehabilitation. Deferring maintenance costs exacts an enormous and partly avoidable subsequent cost.

Second, the collective agreements between governments and medical associations must be rebuilt.The new agreements must underscore the principle that physicians are full partners in the systems where they work, with a reasonable balance between entitlements and obligations. A public system must have the right to mandate a reasonable distribution of physicians both geographically and in alignment with the needs of the population. Compensation schemes must be simplified and must definitively abandon the assumption that activity equals productivity. This means the end of conventional FFS. Accountability for doing things must be replaced with accountability for achieving desired outcomes. It should be a professional obligation to participate in quality-improvement activities, to address variations in practice and to play an important role in resource stewardship. In return, physicians should have good working conditions, ample opportunities for career development and health information systems that help them improve practice. (This point is developed more fully in the June 2013 issue of Policy Options.)

Third, governments and professional regulatory bodies must embrace a new approach that breaks down artificial barriers to career mobility and competency-based scope of practice. Existing regulatory practices focus heavily on beginning-of-career credentials and often link competencies to specific professions. There is little point in encouraging lifelong learning and the acquisition of new skills if the regulatory framework is unable to allow practitioners to stretch their capabilities in continuously changing circumstances. If the goal is to maximize the contribution of all occupations and to encourage individuals to expand their competencies throughout their careers, then law and regulation will have to adapt. It may even be necessary to revisit the sacred construct of the self-regulating profession, given the difficulty of reconciling professional self-interest with the public interest.

Fourth, if we expect health care providers to work in interdependent teams, health science education and apprenticeship will have to make teamwork a core part of the curriculum and a core competency for licensure. For decades, health science education programs have been becoming more specialized and distinct, compartmentalizing health breakdown on the assumption that patients are mechanisms whose health can be maintained by attending to malfunctions in individual parts. Patient-centred care demands carefully orchestrated care plans that are internally coherent and mutually reinforcing. A fragmented group of largely autonomous providers cannot effectively or efficiently meet the needs of patients with multiple chronic conditions and mental health problems. These needs make up the majority of health care business and should drive the way in which health science education is conceived and delivered.

Canada must follow the lead of the UK, Australia and a number of continental European countries and make comprehensive primary health care the backbone of the system. This means polyclinics with a wide array of personnel, capable of repatriating a considerable amount of care from often scarce and overworked specialists. The family doctor of the future should be part geriatrician, part chronic disease expert, part mental health coach and an excellent team player. Behavioural psychology should be a core discipline because improvement requires both providers and patients to change. If this transformation fails, all bets are off.

A recent evaluation of various models of care in Ontario19 showed that community health centres with salaried physicians working in teams tend to look after more disadvantaged populations with complex needs than traditional, cottage-industry FFS practices. Costs, complexity and the potential for adverse events increase when patients bounce from specialist to specialist, each of whom may prescribe therapies in isolation. The assumption that specialty care is superior to primary care must be laid aside. Compensation signals matter; in Denmark, family doctors earn more than specialists.20

Front-line care must not only be better, it must also be more convenient and responsive. Modern communications tools (e-mail, telephone, telehealth, interactive software) are often as effective as in-person visits. FFS payment systems are a major barrier, but so is prevailing culture. A family doctor at Seattle’s renowned Group Health Cooperative works 40 hours a week and has a roster of 1,800 patients, several hundred more than a typically beleaguered Canadian counterpart. Working in teams, doctors schedule only 14 patient visits per day; these appointments are reserved for patients with complex problems that need time to sort out. Others are dealt with promptly by phone or e-mail, often by a nonphysician. Through the widespread use of electronic health records and telephone communication, Kaiser Permanente decreased primary care office visits by 26.2 percent and specialist visits by 21.5 percent.21 Such efficiency is merely common sense, but that is the rarest of all commodities in health care organization and finance.

Fifth, we must root out useless, burdensome and harmful service use. This requires a series of policy initiatives and practice reforms. The world’s best systems ask not just whether something can be done, but whether it should be done. They get to the heart of why intervention rates inexplicably vary, and they clamp down on ineffective diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. All financial incentives that reward both individuals and organizations for inappropriate and unnecessary care should be eliminated. Organizations that prevent health breakdown should be rewarded more handsomely than those that unleash the medical juggernaut to address avoidable failures. It is preposterous to pay physicians more for scheduling multiple appointments to deal with a patient’s needs than for addressing them all at once. Likewise, turn off the tap that excessively rewards the routine use of expensive diagnostic technologies that have a low probability of changing diagnosis, management or outcome.

Sixth, it must be made a core obligation of organizations and individuals to address variation in practice and its cousin, appropriateness of care. Unjustified variation in either the rates of care or the approaches to care of patients with identical problems bespeaks a quality problem. Not all medical work can be standardized, but much of it can, and variation can almost always be narrowed, if not eliminated. The conventional health care discourse in Canada continues to use the language of scarcity. American specialty societies have listed over 100 commonly overused tests and procedures under the rubric of the Choosing Wisely campaign.22 While some people do not have access to required care, there is growing recognition that, at times, providers are too quick to intervene. These issues have been raised from time to time in Canada for 30 years, but there has been no sustained effort to deal with them. As Canada’s physician population continues to grow faster than the general population, the impetus to do more will accelerate, compromising not only cost containment but also prudent and effective care and patient self-management.

Seventh, governments must think very carefully and strategically about incentives for both individuals and organizations. In recent years, a number of provinces have adopted activity-based funding for hospitals and pay for performance for individuals. Both have tended to be based on the achievement of either volume targets (for example, the number of hips replaced) or adherence to processes (for example, the proportion of diabetic patients receiving specific tests), repeating the error of equating activity with productivity. Until we have a full understanding of variation and appropriateness, and unless there is a method for rewarding — or at least not penalizing — the avoidance of dubious or decidedly unnecessary tests and procedures, the new incentives will drive costs higher. One of the great policy failures of the past two decades has been that governments have sent mixed signals on this issue. They have encouraged doctors to abandon FFS but often judge those who are paid by other means by whether their activity levels mimic those of their FFS counterparts. They have encouraged hospitals to be more efficient but penalized them for successful secondary prevention that reduces the demand for more procedures. They have retreated from funding health regions on the basis of population characteristics and needs, funding them instead for workload. Of course, governments should expect health care providers to be efficient and to meet legitimate and addressable health care needs fully and well. But they must recognize that eliminating low-value consultations and interventions, employing a conservative management approach to many conditions and encouraging patients to be self-reliant are crucial elements of good performance and financial efficiency.

Eighth, we must seize every opportunity to lower prices. If it does nothing else, a single-payer system should at least be a smart purchaser. The recent forays into pan-Canadian bulk drug buying should be expanded rapidly. We should link health technology assessment more explicitly to decisions on what to buy and at what price; cease funding drugs, devices and treatments demonstrated to be a waste of money; and follow New Zealand’s lead and bargain for prices that reflect the drugs’ therapeutic benefit. If Ottawa were especially brave, it would rewrite the rules on the tax deductibility of the enormous expenses involved in pharmaceutical marketing.

Ninth, some fairly straightforward structural reforms should be made to create an incentive to seek the most cost-effective care patterns. Budgets could be combined into care bundles to create more natural incentives to substitute less-expensive for more-expensive venues and types of care: for example, hospital and postacute home care; nursing home and home care; primary care and basic diagnostics and drugs. The Lean approach and other methods of streamlining health care processes and eliminating unproductive activity could be pursued. Patient-based rather than volume-based payment methods could be expanded.

Finally, and as important as all of the others, a new and open conversation with the public must be established. That conversation begins with truth telling. Compared with other countries, Canada has a woefully underdeveloped health information culture. Citizens have little access to health information that would help them make more informed decisions about whether and where to undergo treatment, or about the quality and value of the system. When organizations such as the Canadian Institute for Health Information publish even the most innocuous comparative, high-level performance data, the poor performers will often try to explain away their failures, and on occasion provinces threaten to withhold data or cease to participate in future studies. It is virtually impossible for Canadians to obtain information such as a surgeon’s complication or mortality rate, or a hospital ward’s readmission rate — information that is published in newspapers in many American cities.

The irony is that the absence of full public disclosure of what insiders know to be the system’s deficiencies undermines the case for widespread and rapid reform. The public remains fixated on access problems and is largely oblivious to the issues of variation, overuse, poor outcomes and waste. Ultimately, there can be no transformation unless the public considers it necessary and legitimate. Without full and sustained public reporting on the quality, fairness and efficiency of the system and its components, the status quo will prevail over attempts to bend the cost curve, take on the guilds, insist on real accountability or reinvent the workforce. When the massive US Veterans Health Administration reached its nadir — ruthlessly portrayed in the movie Born on the Fourth of July — it changed on a dime. Within four years, it closed 55 percent of its hospital beds, opened over 300 new primary care clinics and improved its preventive health performance across the board. In Canada, we talk as if we’re mad as hell and not going to take it anymore, but our revolutionary zeal is easily deflated. The system does just enough in small increments to quell a sustained uprising. Our expectations are modest, and we are grateful when they are met at great cost. Only a deeper and more forthright commitment to truth telling can free us from complacency and give us the courage to act decisively to make the changes long called for and seldom acted upon.

Timid policies, exhortation, gentle measures and avoidance of difficult conversations will fail to bend the cost curve or achieve both widespread efficiency and quality improvement simultaneously. Doing what we have always done will guarantee that whatever is saved through short-term restraint will be more than given up in the form of panicked spending down the road. That’s been the lesson of the past 20 years. Unless there is the vision, will and creativity to do things differently, we will be destined to repeat our recent mistakes.

Steven Lewis is the president of Access Consulting Limited in Saskatoon and adjunct professor of health policy at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, BC.

Terrence Sullivan is board chair of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health and a professor at the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto.

Montréal – Tandis que les gouvernements provinciaux cherchent une fois de plus à freiner les dépenses de santé, une nouvelle publication de l’Institut de recherche en politiques publiques (IRPP) soutient que pour en réduire définitivement la hausse, ils devront accroître la responsabilisation en matière de valeur et de rendement des soins.

Quelles que soient les économies obtenues par des compressions à court terme, observent ainsi les spécialistes des politiques de santé Steven Lewis et Terrence Sullivan, auteurs de How to Bend the Cost Curve in Health Care, elles seront subséquemment annulées par d’autres dépenses incontrôlées.

« Les coupes des années 1990 et la longue période de dépenses effrénées qui leur a succédé ont clairement montré que les restrictions et les dépenses irréfléchies créent plus de problèmes qu’elles n’en résolvent », expliquent les auteurs de cette analyse à la fois critique et éclairée de la hausse des coûts de soins de santé au Canada. Les années d’investissements ont échoué à régler les sérieux problèmes d’accès, de sécurité, de qualité et d’efficacité.

Le vrai défi consiste à rendre le système plus performant, estiment Lewis et Sullivan.

« La conception même de nos mécanismes de financement et de prestation fait bondir les coûts, jugent-ils. C’est ainsi que la rémunération à l’acte augmente les revenus des médecins selon le volume de services fournis, peu importe que ces services soient médiocres, inadaptés ou de grande qualité. »

L’ensemble du système obéit à une « logique analogue selon laquelle le rendement des soins est mesuré en termes de quantité de services et non de résultats de santé ». Améliorer le rapport qualité-prix des soins exigera donc des gouvernements, des organismes et des intervenants qu’ils quittent la zone de confort des pratiques traditionnelles et qu’ils délaissent l’idée voulant que l’activité soit synonyme de rendement.

Toute réforme structurelle doit prévoir des incitations à privilégier les solutions qui offrent le meilleur rapport coût-efficacité en matière de soins. Pour ce faire, il faut combiner les budgets en groupes de services qui incitent naturellement à remplacer des ressources et traitements coûteux par des soins plus abordables.

« Comme l’ont fait notamment l’Australie et le Royaume-Uni, le Canada aurait intérêt à placer les soins primaires au cœur de son système. Cela nécessiterait de créer des polycliniques dotées d’un personnel diversifié capable de dispenser un volume appréciable de soins à la place de spécialistes souvent peu nombreux et surmenés. »

On peut télécharger sans frais How to Bend the Cost Curve in Health Care, de Steven Lewis et Terrence Sullivan, sur le site de l’Institut (www.irpp.org). Cette publication est la première d’une nouvelle collection intitulée IRPP Insight, qui publiera des critiques et des analyses non arbitrées sur des questions d’actualité.

-30-

Pour de plus amples détails ou solliciter une entrevue, prière de contacter l’IRPP.

Pour recevoir par courriel le bulletin mensuel @propos de l’IRPP, veuillez vous abonner à son service de distribution au www.irpp.org.

Renseignements : Shirley Cardenas Tél. : 514 594-6877 scardenas@nullirpp.org

The Canada Health Act specifies that physicians are entitled to “reasonable compensation,” and the current agreements are the accumulation of four decades of incremental negotiations, compromises and accommodations. All are based on the assumption that a doctor’s “activity” and “productivity” are identical. They are not. Increased medical activity increases costs in the system – but only some increased activity is productive. Some is useless, and some is harmful.

The only way to permanently de-escalate health care spending is to do less with less. Collective agreements with physicians encourage them to practice more medicine, at greater cost. The only way to contain health care spending is to change the deals we make with doctors.

Collective agreements between governments and provincial medical associations are complex and varied, but they share a few key elements. The dominant payment mode remains fee-for-service. Most physicians are independent contractors to the government and operate as cottage industry entrepreneurs with often only fleeting attachments to their place of work and its corporate objectives. Those with office-based community practices are neither formally part of, nor meaningfully accountable, to health regions or their equivalents. Surgeons do have to compete for operating room time, but their practice patterns remain highly autonomous.

In the main, physicians have huge discretion over how they practice, and the claims they make on system resources. Moreover, with a few notable exceptions, they can set up practice wherever they want, regardless of whether the community is under- or over-supplied with doctors. The entirely predictable result is huge variation in how physicians work and the resources they consume.

The collective agreement neither requires nor prohibits excellent practice, but often poor practice is more lucrative. Conscientious and engaged family doctors who spend time dealing with the challenges of complex geriatric cases earn lower incomes for doing so. Others who refer every difficult case to specialists, see 60 patients a day and prescribe drugs indiscriminately make a lot more money. One physician may order three times as many tests for her patients as her colleagues; neither is likely to know that this is the case and there are no consequences for doing so.

The paymaster – government – may or may not be aware of these variations, but rarely, if at all, will anything be done to address them. The one constant under fee-for-service is that each activity generates income for someone, and each activity avoided reduces income for someone. Moreover, there are neither rewards for prudent system resource consumption nor penalties for profligate use.

The perverse incentives that privilege piecemeal problem-solving over holistic care, prescriptions over conversations and procedural specialists over generalists must be erased. So, too must the mechanisms that get in the way of an efficient division of labour between doctors and other providers. A new agreement must prize integration above fragmentation and balanced entitlements with contractual obligations to deliver and be accountable for high quality, appropriate care. Every collective agreement renewal that buys temporary peace by pretending that the price and volume of procedures operate independently is a dagger pointed squarely at the heart of cost containment. Governments and doctors unwilling to depart from the historical path doom the system to a sorry combination of poor performance and eternally rising costs.

“Physician polls reveal that most doctors, and especially younger and female doctors, are ready for change”

Ah, but how do we get there, given the deeply entrenched nature of current structures and the conservative nature of both governments and medical leadership? We propose the equivalent of a two-state solution. Let the primarily older physicians finish out their careers under the general provisions of existing agreements. Invite the others to a separate table to create a new deal that redefines their roles, relationships, clinical accountabilities to the organizations and regions in which they practice, and payment models.

It is one thing to grant late-career doctors the right not to change; it is going too far to allow them to continue to hold their colleagues, governments and the citizenry hostage to the obsolete constructs of the ancien regime. Physician polls reveal that most doctors, and especially younger and female doctors, are ready for change. It is time governments insisted on giving expression to their desires, and for their change-averse colleagues to get out of their way.

This is an excerpt from the June issue of Policy Options. Steven Lewis and Terrence Sullivan are the authors of a newly-released IRPP Insight report titled How to Bend the Cost Curve in Health Care available at irpp.org.