Dans la foulée d’une série d’accords signés avec Ottawa depuis 20 ans, les gouvernements sous-nationaux du Canada en sont venus à jouer un rôle majeur dans la sélection des immigrants. Le premier de ces accords avait été conclu avec le gouvernement du Québec, qui choisit depuis 1991 tous les immigrants économiques désireux de s’y établir. À partir de la fin des années 1990, d’autres accords en partie inspirés par celui avec le Québec ont mené à la création de programmes des candidats des provinces (PCP) dans toutes les autres provinces, au Yukon et dans les Territoires du Nord-Ouest.

Depuis, les PCP se sont développés au point qu’environ le quart des immigrants économiques sont admis au pays à titre de candidats des provinces. Et conformément à l’un des objectifs initiaux des programmes, les destinations d’établissement des nouveaux arrivants ont changé au profit de provinces plus petites comme le Manitoba. Les PCP ont aussi multiplié les volets des programmes, en en créant notamment pour les travailleurs étrangers temporaires ayant une expérience dans une province donnée, les investisseurs, les familles d’immigrants admises en vertu d’un PCP et les étudiants étrangers diplômés. S’appuyant sur de récentes entrevues de recherche, cette étude examine l’évolution des PCP au Manitoba, en Colombie-Britannique, en Alberta et en Nouvelle-Écosse, de même que la cohérence et la coordination de leurs dispositions dans une perspective de gouvernance multilatérale.

Les accords conclus avec Ottawa laissent aux provinces une marge de manœuvre appréciable pour établir des programmes de candidats répondant aux besoins de leur économie et de leur marché du travail. Mais dans plusieurs provinces, leur application a donné lieu à de sérieux problèmes d’intégrité, surtout en ce qui a trait aux programmes d’investisseurs (certains ayant été annulés ou suspendus pour cause d’application inadéquate des exigences de recevabilité et d’admissibilité, voire de fraude). Ottawa a donc réaffirmé son rôle ces dernières années, insistant notamment sur le critère d’intégrité, et apporté des modifications s’appliquant à tous les PCP (entre autres des exigences linguistiques minimales). En 2009, il a imposé des limites au nombre de candidats que peut accepter une province, ce qui a créé des tensions importantes avec certaines provinces.

Essentiellement, Ottawa a traité ces problèmes avec chaque province concernée. Résultat de cette dynamique bilatérale: plusieurs décisions ne s’appuient pas nécessairement sur une vision politique globale ou sur l’expérience d’autres provinces. Et certaines innovations ont été apportées aux programmes sans que l’on mesure leurs effets sur tout le système d’immigration, comme l’indique le recours croissant, dans certaines provinces, aux PCP pour permettre aux travailleurs temporaires d’accéder à la résidence permanente (les critères de sélection qui s’appliquent diffèrent de ceux utilisés pour les candidats au programme des travailleurs qualifiés). Face à cette évolution, l’auteur propose qu’Ottawa et les provinces et territoires participants définissent conjointement une vision, un cadre et des objectifs applicables à tous les PCP, de manière à favoriser leur coordination et à déterminer les futures orientations de ces importants programmes.

Immigration policy is tied to questions of national sovereignty such as border protection and security and is also often linked to national economic and labour market policies. It is thus not surprising that, even in federal states, the admission of immigrants is almost always the responsibility of the national government. Canada is an exception: under the Constitution, the federal and provincial governments have concurrent jurisdiction over immigration, although Ottawa has the final say. However, until the 1970s, provincial governments were almost entirely absent from the field.

In the context of what is sometimes described as immigration federalism (Spiro 2001; Paquet 2012), a certain degree of subnational involvement in immigration matters applies in a number of other federal countries (Joppke and Seidle 2012). Among these, Canada is distinguished by the extent to which provincial governments participate directly in the selection of immigrants. As explained in the first section of this study, this transformation occurred through a series of bilateral agreements (that is, those between the federal and each provincial government). Except for the 1991 Quebec-federal government accord, the agreements are part of the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP). One result is that the distribution of newcomers has changed somewhat to benefit smaller provinces. There has also been a multiplication of entry streams — including for temporary foreign workers resident in the country. These developments are reviewed in the second section. The third section provides overviews of the scope of the PNPs, their impact and current issues in four provinces — Manitoba, British Columbia, Alberta and Nova Scotia.

Provincial governments have generally had considerable leeway in shaping their nominee programs to respond to economic and labour market needs — indeed, this is one of their strengths. However, major program integrity issues have emerged in a number of provinces, particularly with business investor programs.1 As discussed in the fourth section, the federal government has reasserted its role with regard to certain aspects of PNPs — notably, to press for greater program integrity — and introduced policy changes that apply to all PNPs (such as minimum language requirements for candidates). There have also been significant tensions over the caps on the number of nominees each province may accept.

Although processes of multilateral governance (that is, those involving the federal, provincial and territorial governments) are being used more extensively in the immigration field, PNPs have since the outset been subject to a strong bilateral dynamic: the federal government interacts with each province on its own. As a result, some decisions may not be sufficiently informed by the broader perspective and experience (both successful and less so) in other provinces. Moreover, practice is not always consistent with the stated objectives of the program as a whole — as demonstrated by the growing use of PNPs as a channel to permanent residency for temporary workers (both high-skilled and low-skilled). This study concludes by proposing that the federal and participating provincial and territorial governments jointly develop a vision and framework to encourage greater coordination and chart future directions for these important programs.

In light of the rather centralized form of federalism established at Confederation, it may seem surprising that provincial governments were given authority to legislate on immigration. Rob Vineberg (1987, 300) has explained that, because immigration had been a preoccupation of the (pre-Confederation) colonial governments, “it only made sense that all levels of an under-populated agrarian country would be actively interested in immigration and agriculture.” In fact, the immigration field provides an early example of executive federalism: federal-provincial conferences on immigration were held annually between 1868 and 1874; the 1868 conference led to the first intergovernmental immigration agreement, which allowed provincial governments to appoint immigration agents abroad. However, for most of the following century, the federal government regarded immigration as a national program, with provincial involvement permitted only as necessary (Vineberg 1987, 305-6).

Starting in the 1960s, Quebec’s political leaders sought greater powers for their province on a range of matters. Some policy-makers, concerned about the province’s slowing population growth, began considering how to attract more immigrants. A related claim was that the Quebec government was better suited to selecting newcomers who could be expected to integrate into Quebec’s largely French-speaking society. The first of four immigration agreements with the federal government was signed in 1971. Its terms were modest: the Quebec government was authorized to post an information officer in designated countries. The 1975 agreement gave Quebec a modest role in immigrant selection, and this was enhanced in 1978.

The fourth immigration agreement was negotiated at the same time as the 1987 Meech Lake Constitutional Accord and was set to come into effect when the amendments were proclaimed. When that failed to occur, the agreement, known as the McDougall/Gagnon-Tremblay Accord, was signed in 1991 (Citizenship and Immigration Canada [CIC] 1991). The Quebec government obtained the power to select all economic immigrants to the province; the federal government can overrule candidates only for serious security or medical reasons. Selection is based on a points system similar to the one used for the Federal Skilled Worker Program (FSWP) — the principal entry channel for the Economic Class. The Accord also gave Quebec sole responsibility for delivering integration services.

Although all this was achieved through intergovernmental agreements, there is a statutory basis for provincial involvement in selection and other matters. The 1976 federal Immigration Act provided that the minister could “enter into an agreement with any province…for the purpose of facilitating the formulation, coordination and implementation of immigration policies and programs.”2 From 1978, this led to the signing of agreements with a number of other provinces, none of which provided for a provincial government role in immigrant selection (Seidle 2010, 3).

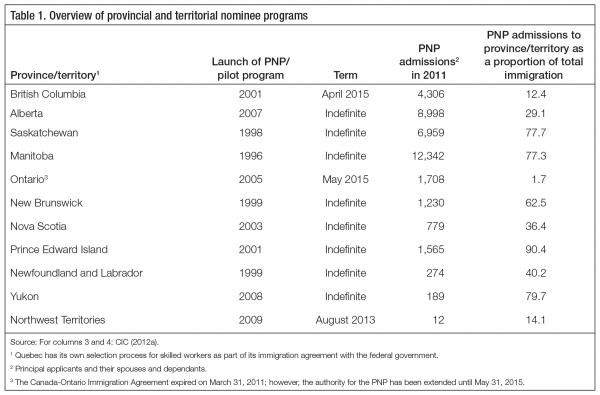

In the early 1990s, the governments of some of the Prairie and Atlantic provinces began to express concern about the low levels of immigration to their regions. In 1995, 88 percent of newcomers settled in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia — principally in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. Manitoba also raised a labour market issue: that as a result of the selection criteria for the FSWP, the province’s need for low-skilled workers in certain sectors was not being met. The federal government, unwilling to replicate its accord with Quebec, developed the PNP to allow other provinces (and the territories) to identify a limited number of nominees who, once approved, would become permanent residents. By 2009, all the provinces other than Quebec, as well as two of the three territories, had signed PNP agreements with the federal government (see table 1). (Despite the involvement of the two territories, the programs are generally referred to as PNPs; this usage has been followed here.)

As for how PNPs function in practice, provincial governments are responsible for:

For its part, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) is responsible for admissibility screening (medical, criminality, security) and the final selection of nominees. The federal visa officer ensures that the applicant:

In addition, the federal government is committed to processing PNP applications as a priority among applications for the Economic Class (CIC 2011a, 2).

According to CIC, the PNP has four main objectives:

On the first objective, advocates claim that provincial governments are better suited than federal officials to assess local labour market needs and that the former have closer links with employers and are able to adjust program criteria more quickly. Although this may be partly true, it skirts a fundamental question: Should admission streams under PNPs cover the range of categories that the various provincial governments judge important, or should PNPs complement — or at least not duplicate — the federal government’s immigration programs?

The second objective reflects smaller provinces’ calls for a greater share of immigration. As the following section demonstrates, PNPs have helped reduce the share of immigrants settling in Ontario, Quebec and BC. The objective of population growth has been particularly important to Manitoba since it launched its PNP in 1999. Some of the Atlantic provinces, notably Prince Edward Island, have also seen the PNP as a means of countering population decline.

Certain provincial governments have, or had, PNP streams with other objectives — for example, stimulating business investment and facilitating family reunification. As we shall see, there have been a number of problems in these two areas, particularly the first. This has led the federal government to press for improved program integrity and a reduction of what it sees as duplication of federal programs. Although some consolidation is taking place, there is no firm consensus about some of the more specific objectives that PNPs can or should serve.

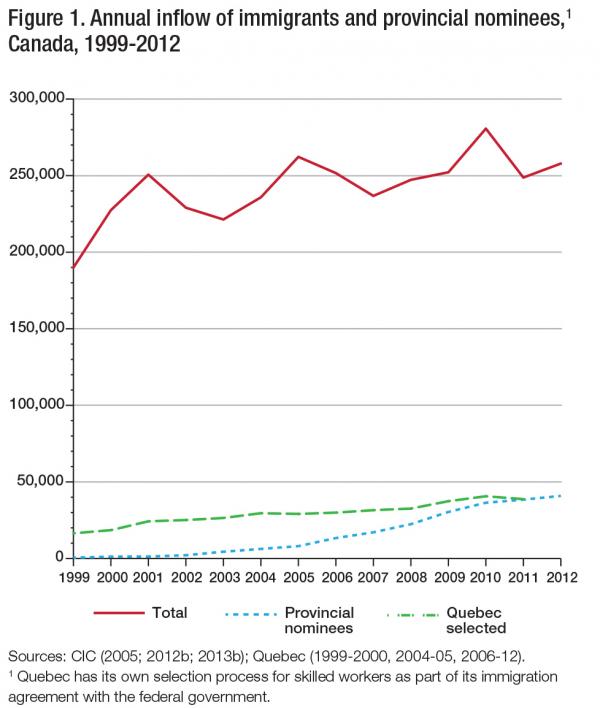

At the outset, the PNP was intended to be modest. In 1999, the first year of operation, 477 people were admitted. The numbers rose steadily in the ensuing years, and by 2004 there were 6,248 admissions (CIC 2005, 2). Following the election of the Harper Conservative government in 2006, there was a move away from limits on the number of nominations allocated to individual provinces. Renegotiated agreements and new agreements did not include limits. This further accelerated growth in PNP admissions (see figure 1).

In 2012, 40,899 people (17,200 principal applicants and 23,699 spouses and dependants) were admitted to Canada through PNPs (CIC 2013b). This represented 25 percent of the total economic principal applicants admitted that year. Combined with the economic immigrants selected by the Quebec government (Quebec 2013), provincially selected immigrants accounted for 50 percent of the Economic Class in 2012.

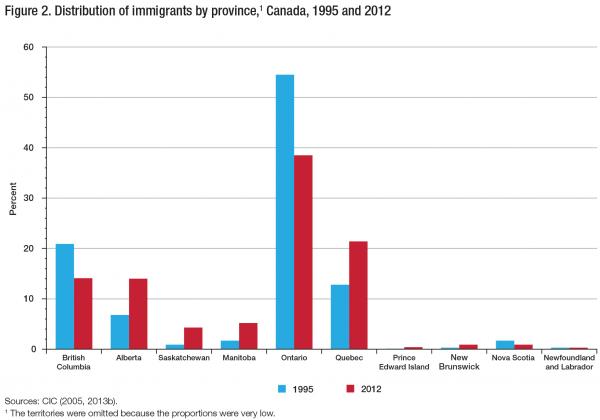

Figure 2 illustrates the changes in the distribution of immigrants between 1995 (before the first PNPs were launched) and 2012. During this period, the proportion that went to Ontario, Quebec or British Columbia dropped from 88 to 73 percent. Ontario, which in 1995 received 55 percent of newcomers, welcomed 38 percent in 2012. BC saw its share drop from 21 to 14 percent of the national total, while Quebec’s share rose from 13 to 21 percent during the same period. Among the smaller provinces, Manitoba registered the largest proportional increase — from 1.7 percent in 1995 to 5.2 percent in 2012. Although not all of these shifts can be attributed to the PNP — for example, the post-2008 economic downturn led to reduced flows to Ontario — the program has helped increase the share of immigrants settling outside the three most populous provinces.4

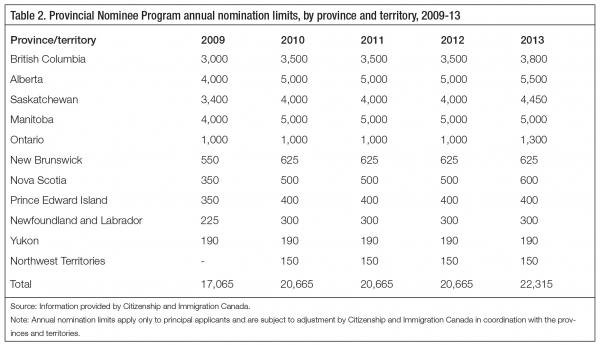

As PNP entries rose in the mid-2000s, the national immigration targets remained essentially at the same level. CIC became concerned that as a result of PNP growth, fewer economic immigrants were being admitted through the FSWP. Effective for 2009, it implemented nomination limits for the country as a whole and for each participating province/territory. The national limit (principal applicants) for 2009 was 17,065. To arrive at this number, provincial governments were asked how many nominees they expected to select in 2009, and their responses were totalled. The national limit was increased to 20,665 for 2010 and remained at that level for 2011 and 2012. Ministers from a number of provinces called for the limits to be raised. This included Ontario, which had recently begun to show interest in attracting more immigrants through its modest PNP (Friesen 2012; Baglay 2012, 132-3). Jason Kenney, the federal minister, said repeatedly in 2011 and 2012 that increases would not be possible.

Pressure from a number of premiers to raise the national limit continued. CIC concluded there might be some flexibility because in recent years the number of dependants accompanying provincial nominees had been lower than expected. When Kenney met his provincial/territorial counterparts in November 2012, he informed them that he was considering raising the national limit. It was subsequently set at 22,315 for 2013. Following further CIC consideration, which involved weighing a number of factors (including the degree to which the province had adjusted its PNP to focus on economic immigration), five provinces saw slight increases in their 2013 allocation (see table 2). For 2014, the target for PNP admissions (principal applicants, spouses and dependants) has been set at 44,500 to 47,000. If met, this will constitute a record level for the program (CIC 2013d).

As PNP numbers increased, so did the range of streams or categories through which nominees could be admitted. According to a 2010 study, in addition to the general or employer recruitment streams that all provinces administered, six provinces had business investment programs, six had family reunification streams and four had a stream for international students (Carter, Pandey and Townsend 2010, 7). Following a number of critical evaluations and audits, some of the business and family streams were closed. Further changes can be expected in response to CIC pressure to focus on economic immigration (as discussed in the fourth section).

A further significant development is that PNPs have become an important channel for two-step migration by providing access to permanent residency for some temporary foreign workers (TFWs) after they have worked in the country for a set period. The potential pool of TFWs has grown considerably: between 2002 and 2012, the number of TFWs admitted to Canada rose from 110,616 to 213,441 (CIC 2013c; see also Worswick 2013, 3). The federal Canadian Experience Class, introduced in 2008, allows high-skilled TFWs (those with jobs in National Occupation Classification [NOC] categories 0, A and B) to apply for permanent residency.5 In contrast, eight provinces and two territories also admit at least some low-skilled TFWs (NOC C and D).6 Manitoba’s PNP makes no distinction by skill level. In British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Yukon and the Northwest Territories, only those who are employed in designated low-skilled occupations or who fall within the category of “critical impact worker” qualify. Nova Scotia has no explicit channel but does admit some low-skilled TFWs. Ontario allows only high-skilled TFWs to apply. Despite this variation, PNPs are now the most likely path to permanent residency for low-skilled TFWs (Nakache and D’Aoust 2012, 161). In 2012, of the 38,067 TFWs who became permanent residents, 12,968 (34 percent) did so through PNPs (CIC 2013b). Over time, there has been what Tom Carter (2012, 187) has labelled a blending of the PNP and the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. This development has important implications, which I discuss in the assessment section.

Since the inception of the PNP, provincial governments have had considerable flexibility to tailor their programs to labour market needs and other priorities, such as attracting entrepreneurs and (in a small number of cases) facilitating family reunification. This section provides overviews of the development of PNPs in four provinces — Manitoba, British Columbia, Alberta and Nova Scotia — and the main results and current issues in each case. The first three provinces were chosen because for most of the period since Manitoba launched the first PNP, they have received the largest numbers of nominees (since 2009, Saskatchewan has received more nominees than BC). Nova Scotia was chosen in order to include one of the four Atlantic provinces and because it has long been a less significant destination for newcomers. Research for this study included nine semistructured interviews with present and former officials from Citizenship and Immigration Canada and each of the provincial governments.

In the early 1990s, business and other interests began calling for increased immigration to Manitoba (Leo and August 2009, 496). In particular, employers in the garment industry wanted greater flexibility to recruit immigrant workers (Baxter 2010, 18-19). In 1996, the Canada-Manitoba Immigration Agreement (CMIA) was signed. It provided for the negotiation of an annex on provincial nominees and the launch of a pilot project to recruit sewing-machine operators. The PNP annex was approved in 1998, along with a second annex providing for the devolution of settlement services (until then administered by CIC) to Manitoba.7

For the first two years, the Manitoba government was allowed to nominate 200 immigrants and their families. In response to demand, the limit was subsequently raised. When the CMIA was renewed in 2003, the cap was removed — a move that reflected the good relations between the federal and Manitoba ministers. Since the outset, Manitoba has led the provinces in its use of the PNP. Between 1999 and 2009, 45 percent of the nominees who arrived in Canada were destined for Manitoba (Carter 2012, 184). In 2011, 77 percent of all immigrants to Manitoba came through the PNP. Including some increase in the arrivals under federal programs, total immigration to Manitoba more than tripled from 4,610 in 2000 to 15,963 in 2011; this dropped to 13,391 in 2012 (CIC 2005; CIC 2012b; CIC 2013b).

Between 2004 and early 2013, the Manitoba PNP, which is administered by the Immigration and Multiculturalism department, had five streams: General, Family Support, Employer Direct, International Students and Strategic Initiatives (these are described in CIC 2011b). In part to make it easier for potential applicants to understand program requirements, in April 2013, the streams were consolidated into two categories.8 The first, Skilled Workers in Manitoba, is for potential applicants already in the province, including TFWs and international students. To be eligible, TFWs must have worked for an employer in Manitoba for at least six months and have an offer of a long-term, full-time job from the same employer. The same requirements apply to international students who have graduated from a publicly funded Manitoba post-secondary institution in a program of at least one year’s duration.

The second category, Skilled Workers Overseas, is open to applicants who have a connection to Manitoba through one of the following:

All applicants in this category are assessed according to a points system. Principal applicants must also demonstrate that they have at least $10,000 in liquid, transferrable settlement funds in their own name; eligible dependants must have $2,000 each.

Manitoba has two business-related categories:

The business program came under scrutiny after concerns were raised that among the applications from China — the volume of which doubled between 2007 and 2011 — there were some containing false information. In January 2013, a report from the Manitoba Auditor General confirmed that a significant proportion of Chinese applicants had submitted forged or fraudulent documents. It also indicated that between 2005 and 2010, 37 percent of business nominees did not meet the program requirements and forfeited their deposits (CBC News 2012). In its response, the department indicated that it had “proactively implemented integrity and enhanced quality assurance measures,” and that improvement would continue (Manitoba 2013, 238).

Encouraging immigrants to settle in smaller communities has been a key objective of Manitoba’s PNP. Between 2000 and 2012, an average of 31 percent of nominees, many of them former TFWs, settled outside Winnipeg. The peak was in 2000, at 49 percent; by 2012, it had dropped to 19 percent. The two top destinations after Winnipeg have been Winkler and Brandon, each of which has received some 6,000 immigrants since 2000; meat-packing is an important industry in the latter, as it is in Neepawa.9 The provincial government has made concerted efforts, in collaboration with communities, to adapt its settlement services in regional centres with limited recent experience of immigration (Carter, Morrish and Amoyaw 2008; Seidle 2010, 6-7). In a 2008-09 survey of 100 PNP principal applicants and 50 spouses (conducted as part of an evaluation of the PNP), newcomers who had settled outside Winnipeg rated their communities as more friendly and welcoming environments than did those living in the capital (Carter 2010).

Manitoba’s PNP provides channels for two-step migration. Once a TFW has been in the province for six months, he or she may apply for permanent resident status. Unlike some of the other provinces, Manitoba does not limit TFW applications to the high-skilled or people working in particular occupational fields. Between 2005 and 2011, an average of 816 TFWs a year became permanent residents under the Manitoba PNP. Sixty percent of those who made the transition were low-skilled (NOC C and D).10

Manitoba’s PNP has been more closely studied than any of its counterparts. One in-depth review concluded that the program “has been successful in achieving its stated objectives…and remains a model for other provinces to emulate” (Carter, Pandey and Townsend 2010, 33). Another study attributed the program’s success to the Manitoba government’s decision to work closely with community groups interested in bringing in immigrants (Leo 2006, 498). In my interviews with them, past and present provincial officials revealed their pride in the innovation that the PNP has allowed and in the program’s focus on engaging stakeholders in the immigration process. There are nevertheless some concerns that Manitoba’s PNP may have become what Tom Carter has described as a “something for everybody program” that, with federal funding, has been used to compensate for labour force shortages due in part to inadequate efforts in other policy areas, such as retraining older workers and improving the skills of the Aboriginal population.11

Despite the federal government’s unexpected decision in April 2012 to resume delivery of federally funded settlement services in the province,12 Manitoba Immigration’s relations with CIC seem to be reasonably good. The cap on nominees (currently 5,000 principal applicants a year) nevertheless remains a point of contention. Commenting on the drop of more than 2,500 immigrants (PNP and federally selected) to Manitoba between 2011 and 2012, Immigration Minister Christine Melnick attributed this to the cap, which she said should be lifted (CBC News 2013). However, Manitoba’s limit remained unchanged for 2013.

The first immigration agreement with BC, struck in 1998, included provisions to establish a PNP. A second agreement was signed in 2004 and remained in force until 2010. The latest agreement, which has a five-year term, was reached in 2010. As did its predecessors, the 2010 agreement includes an annex on provincial nominees.13 During most of this period, the BC government delivered federally funded settlement services. However, further to Jason Kenney’s April 2012 announcement (CIC 2012c), CIC will resume its administration in April 2014.

In part because BC has consistently received the second-highest number (after Ontario) of immigrants under federal programs, the BC government did not initially place as much emphasis as the Manitoba government did on nominee recruitment. By 2005, the number admitted under the BC program was fewer than 1,000. This later increased considerably, reaching 4,900 in 2010. There were 5,932 nominees in 2012, which represented 16 percent of total immigration to BC. Entries through the PNP have not compensated for the drop in admissions through the FSWP, which declined by 45 percent between 2005 and 2009. The report on the evaluation of the BC PNP for the period 2005-10, carried out by Grant Thornton LLP, observed that BC had become increasingly reliant on the PNP and the federal TFW Program to meet labour market demand and regional needs (British Columbia 2011).

The BC PNP, administered by the Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training, has two main streams: Strategic Occupations and Business. The first stream has the following areas of focus:

A number of the entry channels provide for two-step migration, and this has been significant. In the period 2005-10, an average of 79 percent of BC nominees had been TFWs. In 2010, the proportion was 93 percent.14 A study of the labour market outcomes of BC nominees concluded that their prior Canadian experience may have contributed to their success (Zhang 2012).

Business immigrants under the BC PNP fall into one of three categories:

BC provincial officials consider that, overall, business nominees have performed well. Between 2008 and 2012, entrepreneurs nominated through this stream invested $580 million and created 1,068 jobs.15 However, there have been some difficulties with the business program. A fast-track process under the Business Skills and Regional Business categories allowed applicants to be nominated for permanent residency immediately after they arrived in the province if they posted a $125,000 performance bond, which was returned once the program requirements were met. Suspicions were raised by a large increase in applications following the federal government’s decision to suspend its investor and entrepreneur visa programs (Hunter 2012). A government report indicated that only 26 of the 141 businesses that had used the fast-track option since 2007 had fulfilled the necessary requirements (Fowlie 2012). In November 2012, Pat Bell, the minister responsible for the BC PNP, announced the suspension of the fast-track option.

A number of the Strategic Occupations and Business streams include incentives to settle or invest in areas outside Metro Vancouver. Although this remains an ongoing challenge, BC officials told the author that about 25 percent of nominees are currently settling elsewhere in the province.16 A survey carried out in 2010 as part of the Grant Thornton evaluation found that, over time, there has been further migration out of the Mainland Southwest region (which includes Vancouver).

The evaluation report concluded that the BC PNP was increasing the benefits of immigration to BC. Noting some overlap with certain federal economic immigration programs, it observed that “the BC PNP’s focus on meeting specific labour market and economic development needs…clearly differentiates it from these programs, and highlights its continuing relevance” (British Columbia 2011). Looking forward, the province’s Immigration Task Force, which reported in May 2012, recommended that the 3,500 cap be raised to 5,000 for 2012 and 6,500 for 2013 (British Columbia 2012, 3). In February 2012, Pat Bell asked the federal immigration minister, Jason Kenney, to raise the limit to 10,000 (Carman and O’Neil 2012). It was increased slightly to 3,800 for 2013.

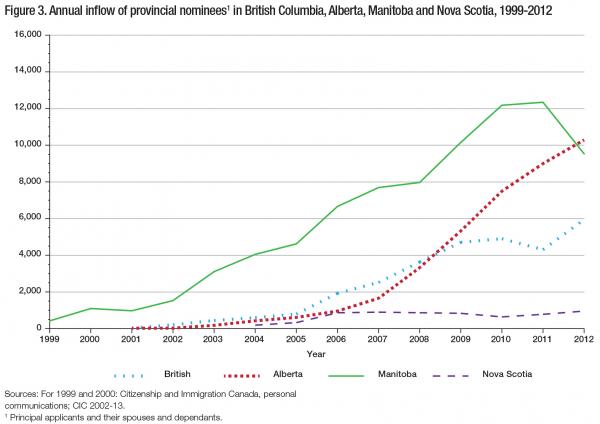

The Alberta Immigrant Nominee Program (AINP) began as a pilot project in 2002. In 2007, an annex to the Agreement for Canada-Alberta Cooperation on Immigration provided for an ongoing program.17 Admissions under the pilot reached only 956 by 2006. Rapid growth in the oil and gas sectors from the mid-2000s led employers to rely more extensively on TFWs (Derwing and Krahn 2008, 187), and the number of nominees increased. By 2009, Alberta had overtaken BC as the province accepting the second-highest number of nominees (see figure 3). Growth continued over the next two years. However, in 2012, Alberta did not meet its quota of 5,000 principal applicants. This resulted from, among other factors, the downturn in certain sectors that traditionally relied on the AINP and the decision to refer relevant candidates to the Canadian Experience Class and other federal programs.

Administered by the Department of Enterprise and Advanced Education, the AINP has three streams: Employer-Driven, Strategic Recruitment, and Self-Employed Farmer. The Employer-Driven stream is organized into three categories:

Under the Strategic Recruitment stream, candidates may apply without an employer. For a number of years, this stream has included two categories:

In 2013, two further categories were added to the Strategic Recruitment stream, broadening considerably the range of potential applicants under the AINP:

In addition, the Self-Employed Farmer stream is open to farmers who want to establish or purchase a farm business in Alberta, have a minimum net worth of $500,000 and are willing to invest at least $500,000 in a primary-production farming business in Alberta.

For a number of years, the Alberta government had a family stream (for close relatives aged 21 to 45) as well as a category for US visa holders (that is, people working in the US on temporary skilled worker visas and employed in occupations under pressure). In August 2010, the program stopped accepting applications for both categories because it wanted to prioritize nominating people who were currently working in permanent jobs or who had job offers in high-demand occupations. In April 2013, the categories were permanently closed. The absence of a business stream — and, since 2010, a family stream — may explain why program integrity does not seem to have been an issue in relations with CIC.

Between 2002 and 2010, the highest proportion of Alberta’s nominations was in the Skilled Workers category (40 percent of the total), followed by the Semiskilled Workers category (27 percent). The vast majority of nominees during the same period had been TFWs: Skilled Workers, 96 percent; International Graduates, 99 percent; Semiskilled Workers, 99 percent. The AINP has therefore been used almost exclusively as a pathway to permanent residency. In this regard, in early 2012, Dave Hancock, the minister responsible for immigration, observed: “People invested in [TFWs] in terms of their capabilities to do the job and their ability to settle into the community…In other words, they’ve already proved that they can be part of the community and be valuable to our province” (quoted in O’Neil 2012). In light of the province’s buoyant economy and the steady growth in its PNP, it is not surprising that the Alberta government has been pressuring the federal government to allow it to accept a great number of nominees. In the same statement, Hancock called for Alberta’s limit to be raised from 5,000 to 10,000 (quoted in O’Neil 2012). It was increased to 5,500 for 2013.

Nova Scotia’s nominee program dates from 2002. The current provisions are included in an annex to the Agreement for Canada-Nova Scotia Co-operation on Immigration, signed in 2007. The Nova Scotia Office of Immigration administers the PNP.20 In 2004, the first year for which data are available, Nova Scotia admitted 186 newcomers (principal applicants, spouses and dependants) under the program. The peak was reached in 2007 with 896 nominees. Levels dropped somewhat to 638 in 2010 and 779 in 2011. Because not all provinces met their quotas, in late 2012, Nova Scotia’s cap (principal applicants) for that year was raised from 500 to 700. For 2013 it is set at 600. Nominees and their families accounted for 36 percent of total immigration to Nova Scotia in 2011.

Initially, the Nova Scotia PNP had three streams. One of them, the Economic stream (launched in 2002), required applicants to invest at least $100,000 in a Nova Scotia business and participate in a six-month mentorship with the business. A number of serious issues emerged (some of which were referred to the police), and in mid-2006, the stream was closed to new applications. It emerged later that program criteria were often not respected, and that the private company partly responsible for the administration of the program had made a considerable amount of money with little to show for its efforts (Dobrowolsky 2013, 206). A subsequent review reported that many of the Economic stream nominees either did not come to the province or left after recouping all or part of their original $100,000 contribution (Nova Scotia 2012).

The Nova Scotia PNP currently has three streams in operation:

Three other streams that operated for a number of years are currently closed: International Graduates, Nondependant Children of Nova Scotia Nominees and Agri-food Sector.21 According to a senior Nova Scotia official interviewed in April 2013, Nova Scotia wants to focus on nominating skilled workers to fill labour market needs and, where relevant, it will direct applicants to federal programs. For example, international graduates will be encouraged to apply to the Canadian Experience Class (Nova Scotia 2013b). The official added that the department wants to ensure a high level of program integrity and align its PNP with recent federal policy changes.

The Nova Scotia PNP has no specific channel for low-skilled TFWs, but they are not excluded. In fact, 22 percent of the nominations made in 2012 were at NOC levels C or D.22 As in a number of other provinces, in Nova Scotia, efforts have been made to encourage newcomers to settle in rural and small communities. Through the Community Identified stream, almost 40 percent of newcomers have settled outside the Halifax region. This stream, to be renamed Regional Labour Market Demand, is being restructured to focus on meeting regional labour market needs. Applicants will need to demonstrate that they can fairly quickly attach themselves economically to the region where they plan to settle and indicate that they wish to live there permanently.23

The Nova Scotia government wants to increase immigration to boost its workforce as the population ages. Its 2011 immigration strategy called for a doubling of the number of immigrants (federally selected and nominees) in order to reach 7,200 by 2020. This is an ambitious objective and cannot be met by the modest increases in PNP limits set for 2013 and 2014.

Although the PNPs in the four provinces covered here differ considerably, there are some commonalities: a focus on responding to specific labour market needs, including regional ones; criteria to encourage a proportion of nominees (both individuals and businesses) to settle outside the province’s largest city; extensive reliance on TFWs as candidates; and efforts to pressure the federal immigration minister to raise the nominee limits. All four provinces have adapted to changing priorities and addressed program integrity issues.

Business streams have been the single greatest weakness in PNPs across the country. They have been modified in Manitoba and BC; Nova Scotia closed its stream for investors only four years after it was opened (Alberta has not had one). Some other provinces, notably Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick, have also faced problems with their investor programs; the latter announced in September 2013 that, owing to a large volume of applications, it was putting a temporary hold on its business category (Daily Commercial News 2013). In Alberta and Nova Scotia, there has been a move away from using the PNP for family reunification. However, in contrast to Saskatchewan’s tightening of its family referral stream,24 this did not occur because of program integrity issues. All in all (even if this is not by design), recent changes in the four provinces covered here are contributing to greater alignment between PNPs and federal programs.

In addition to the evaluations carried out in a number of provinces, CIC sponsored an evaluation of the PNP as a whole for the period 2005-09. The conclusions were mostly quite positive:

The evaluation report also included the following, more critical, observations:

On intergovernmental relations, the report stated, “Respondents expressed a wide range of opinions regarding the clarity of roles and responsibilities for the delivery of the PNP” (CIC 2011a, vi).

Although the CIC evaluation did not devote much attention to the language competency of nominees, the report nevertheless observed that in contrast to the FSWP and the Canadian Experience Class, there was no consistent minimum standard across individual PNPs and streams (CIC 2011a, 31).

Commenting on the evaluation findings, Jason Kenney observed: “[W]e are excited about this program but realize that it needs improvements in key areas.” In this regard, CIC moved quickly on one point. In April 2012, Kenney announced that effective July 1, 2012, most PNP applicants for semiskilled and low-skilled professions would have to be tested and meet minimum language standards (CIC 2012d).

This announcement can be seen as part of a reassertion of the federal role with regard to PNPs — a process that began in 2009 when CIC implemented annual limits for PNP principal applicants. Virtually all of the provincial governments have since been actively lobbying the federal government for more nominees, and a number of employers’ organizations and other stakeholders have supported them. Following a meeting with his provincial and territorial counterparts in November 2012, Kenney stated that the federal government does not want to “completely cede [its] role in selecting immigrants.” He added: “We believe immigration is not just about addressing regional labour market needs, it’s also about nation building” (quoted in Friesen 2012). Kenney nevertheless raised the national PNP limit for 2013 by 1,650. Provincial governments continue to call for further increases. For example, following the July 2013 meeting of the Council of the Federation, premiers called on the federal government to “scale up the caps on immigration levels” under the provincial and territorial nominee programs (Council of the Federation 2013). The national limit was increased further for 2014.

The emphasis on reducing duplication of federal programs and efforts to improve program integrity are further expressions of the reasserted federal role. On family reunification, Kenney repeatedly suggested that applicants should rely on the federal program, not provincial family reunification streams.25 A number of PNP streams for business investors have also suffered from program integrity issues. In such cases, critical provincial audits and evaluations (rather than federal pressure) were often the catalyst for closing the stream.

Duplication is not as clear-cut as program integrity issues. In some senses, it depends on where one is sitting. One provincial official told the author that the federal government has been redesigning its programs in ways that overlap with and duplicate PNP streams. As examples, he mentioned the Canadian Experience Class (which, as do five PNPs, provides a pathway to permanent residency for high-skilled TFWs) and the federal Skilled Trades Program, launched in January 2013 (CIC 2013c). Kenney, one of the most active federal immigration ministers in decades (until his appointment to a new department in July 2013), saw things differently. In a March 2012 speech, he remarked: “We’re saying to the provinces, ‘Let’s stop the duplication. Don’t nominate people who could come to Canada as permanent residents through a federal program like the Experience Class’” (CIC 2012e).

Differences of view such as these will persist as efforts continue to align the roles of the federal and provincial governments in immigrant selection. Although one of the strengths of PNPs is the program flexibility they offer provincial governments,26 for the better part of a decade they were left to expand and innovate without reference to a national policy framework; and, at least in some cases, insufficient attention was paid to program effectiveness and evaluation (Alboim and Maytree 2009; Auditor General of Canada 2009, chap. 2).

The lack of reference to a policy framework is reflected in the growing role of PNPs as a channel to permanent residency for TFWs, including for the low-skilled in designated occupations (as in BC and Alberta). Indeed, this dimension is not even mentioned in the four objectives of the PNP quoted in the first section of this study. The possibility of making the transition to permanent residency can make TFW jobs more attractive, contribute to the continuing rise in TFW admissions and lessen employers’ incentive to hire and/or train Canadians (on the latter, see Halliwell 2013, 38).

In this regard, concerns have been expressed (including in the interviews for this study) that admitting growing numbers of low-skilled TFWs may lead to a “deskilling” of the country’s immigrant pool. Some provincial governments are not only using their room to act but also making quite frequent adjustments to the PNP admission criteria for TFWs — as illustrated by Alberta’s mid-2013 policy changes (some of which lasted only a few months). Although the number of TFWs any province admits in a given year may not be high, it is not clear that the consequences for its labour force and those of neighbouring provinces are being adequately taken into account. This is only one example of the implications of the extensive program variation in immigrant selection. There is thus reason to heed Keith Banting’s observation that Canada has moved “from a world in which one government was clearly responsible for immigration to one in which everyone and no-one is in charge” (2012, 104).

Although some of Jason Kenney’s efforts to align PNPs (or particular streams) with federal programs were probably overdue, there are problems with an approach that relies extensively on pressuring individual provinces. A focus on bilateral processes — spokes on a wheel — precludes a review of the weaknesses (and strengths) of a given PNP in relation to those of other provinces and territories. Although the frequent intergovernmental meetings and conference calls that occur within the immigration sector provide the opportunity to raise particular issues, there is no ongoing committee or working group with a specific mandate with regard to PNPs.

This contrasts with steps the federal, provincial and territorial governments have taken since 2009 to develop a pan-Canadian framework for settlement outcomes. Its purpose is “to provide a cohesive, national approach for defining and measuring settlement outcomes and to establish the evidence base for better accountability and policy decisions” (CIC 2013a). It is notable that, except in Quebec, settlement programming is largely administered by CIC (although the agreements with Manitoba and BC were still in force when discussions began on the framework). Despite that, agreement was reached on this innovative intergovernmental framework.

In light of the significant (and still growing) provincial role in immigrant selection and the need to consider the implications of individual provinces’ program changes (including the intersection with other immigration streams — see Alboim and Cohl [2012, 25]), it is time that participating governments develop a shared vision and framework for PNPs. The framework would not replace bilateral discussions between individual provincial/territorial governments and CIC. Nor would it cover the highly political matter of each PNP’s annual limits. Rather, it would be centred on a statement of shared objectives intended to chart future directions for all the nominee programs. The framework would provide a reference point for addressing developments such as the increasing reliance on PNPs as a pathway to permanent residency for TFWs. An ongoing working group could be created to ensure a regular exchange of information and data (including that on nominees’ outcomes). This would encourage greater coordination and the kind of learning across jurisdictions that can be one of the strengths of intergovernmental processes.

Provincial nominee immigration programs, the fruit of a series of bilateral agreements with the provinces/territories dating from the late 1990s, have been successful in several respects. They have allowed provincial governments, through links with employers and other actors, to respond to particular labour market pressures, including those outside metropolitan areas. PNP applications have been processed considerably faster than FSWP applications (Young 2011, 317). Nominees have quite positive economic outcomes, even in their initial years after admission. In provinces such as BC and (especially) Manitoba, the program has encouraged a significant share of immigrants to make their homes outside the largest city. More generally, the PNP has led a greater proportion of new arrivals to settle outside the three largest provinces. The limits that have applied since 2009 may nevertheless put a brake on the growth of the share of newcomers settling in smaller provinces.

The development of PNPs demonstrates once again the often-praised laboratory dimension of federalism. The programs vary a good deal, but this is to be expected and should not simply be criticized as undue complexity or asymmetry. However, things can sometimes go wrong in laboratories. The major problems with the business investor streams in a number of provinces exemplify this, and some provincial governments have closed or suspended these streams. On family reunification, federal pressure has led to changes in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. The result is that in these two areas, PNPs and federal immigration programs are now more closely aligned.

Looking forward, it is important to bear in mind that, as Davide Strazzari has written, “immigration federalism is a dynamic phenomenon, the equilibrium of which is constantly challenged” (2012, 137). Although the concept of immigration federalism includes elements of competitive federalism, it also entails cooperation to achieve shared policy goals. In this regard, the optimal overall objective for Canada would be to preserve a reasonable level of provincial government flexibility with regard to PNPs while bringing greater coherence to these programs and the immigration system as a whole (which continues to evolve as a result of federal program changes). One way to achieve this would be to rely more extensively on multilateral intergovernmental processes by developing a shared vision and framework centred on a statement of shared objectives for PNPs. Although bilateral relations between Ottawa and individual provincial governments would still play an important role, this framework could encourage coordination and learning across jurisdictions and lead to a clearer alignment of federal and provincial immigrant selection programs.

Alberta. 2013a. Alberta Immigrant Nominee Program, September 27. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.albertacanada.com/immigration/immigrating/ainp.aspx

—————–. 2013b. Enterprise and Advanced Education. “New Immigration Option for Foreign Workers in Alberta.” News release, June 20. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.albertacanada.com/germany/documents/AINP_June_2013.pdf

—————–. 2013c. “Ineligible Occupations List,” September. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.albertacanada.com/files/albertacanada/AINP_srs_AWE_ineligible_occList.pdf

—————–. 2013d. “Semi-skilled Worker Criteria,” September 18. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.albertacanada.com/immigration/immigrating/ainp-eds-semi-skilled-criteria.aspx

Alboim, N., and K. Cohl. 2012. Shaping the Future: Canada’s Rapidly Changing Immigration Policies. Toronto: Maytree Foundation. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://maytree.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/shaping-the-future.pdf

Alboim, N., and Maytree. 2009. Adjusting the Balance: Fixing Canada’s Economic Immigration Policies. Toronto: Maytree Foundation. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.maytree.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/adjustingthebalance-final.pdf

Auditor General of Canada. 2009. 2009 Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_200911_02_e_33203.html

Baglay, S. 2012. “Provincial Nominee Programs: A Note on Policy Implications and Future Research Needs.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 13 (1): 121-41.

Banting, K. 2012. “Canada.” In Immigrant Integration in Federal Countries, edited by C. Joppke and F.L. Seidle. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Baxter, J. 2010. “Precarious Pathways: Evaluating the Provincial Nominee Programs in Canada: A Research Paper for the Law Commission of Ontario,” July 6. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://www.lco-cdo.org/baxter.pdf

British Columbia. 2011. Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Innovation. BC Provincial Nominee Program Evaluation Report. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.welcomebc.ca/welcome_bc/media/Media-Gallery/docs/immigration/come/BCPNPEvaluation_MainReport_2011.pdf

—————–. 2012. British Columbia Immigration Task Force, Minister of State for Multiculturalism. British Columbia Immigration Task Force. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.jtst.gov.bc.ca/immigration_task_force/docs/Immigration_Task_Force_WEB.PDF

—————–. 2013. Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training. BC Provincial Nominee Program. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.welcomebc.ca/Immigrate/About-the-BC-PNP.aspx

Carman, T., and P. O’Neil. 2012. “B.C. Hopeful Ottawa Will Increase Immigration Quota, Despite Saying No to Alberta.” Vancouver Sun, February 9. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.vancouversun.com/s/+Ottawa+will+increase+immigrant+quota+despite+saying+Alberta/6129845/story.html

Carter, T. 2010. An Evaluation of the Manitoba Provincial Nominee Program: Policy Reflections. Report prepared for the Manitoba Department of Labour and Immigration.

———. 2012. “Provincial Nominee Programs and Temporary Worker Programs: A Comparative Assessment of Advantages and Disadvantages.” In Legislated Inequality: Temporary Labour Migration in Canada, edited by P.T. Lenard and C. Straehle. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Carter, T., M. Morrish, and B. Amoyaw. 2008. “Attracting Immigrants to Smaller Urban and Rural Communities: Lessons Learned from the Manitoba Provincial Nominee Program.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 9 (2): 161-83.

Carter, T., M. Pandey, and J. Townsend. 2010. The Manitoba Provincial Nominee Program: Attraction, Integration and Retention of Immigrants. IRPP Study 10. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

CBC News. 2012. “Manitoba Defends Business Immigrant Program,” December 5. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/story/2012/12/05/mb-provincial-nominee-investment-program-immigrants.html

—————–. 2013. “Manitoba’s Immigration Dips in 2012: Report,” March 20. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/story/2013/03/20/mb-immigration-numbers-down-manitoba.html

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 1991. Canada-Québec Accord Relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens, February 5. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/DEPARTMENT/laws-policy/agreements/quebec/can-que.asp

—————–. 2002-13. Annual Reports to Parliament on Immigration. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/search-recherche/index-eng.aspx?search=basic&query=annual+reports&s=0&l=e

—————–. 2005. Facts and Figures: Immigration Overview — Permanent and Temporary Residents, 2004. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/Ci1-8-2004E.pdf

—————–. 2011a. Evaluation Division. Evaluation of the Provincial Nominee Program. Evaluation and Research. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/pdf/research-stats/evaluation-pnp2011.pdf

—————–. 2011b. Evaluation of the Provincial Nominee Program: Provincial-Territorial (PT) Appendices, September 29. [Available on request from the Evaluation Division of Citizenship and Immigration Canada.]

—————–. 2012a. Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/publications/annual-report-2012/section3.asp

———. 2012b. Facts and Figures: Immigration Overview — Permanent and Temporary Residents, 2011. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/pdf/research-stats/facts2011.pdf

—————–. 2012c. “Government of Canada to Strengthen Responsibility for Integration of Newcomers ‘Integration Services Are about Nation Building,’ Says Kenney.” News release, April 12. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/media/releases/2012/2012-04-12.asp

—————–. 2012d. “Minister Kenney Strengthens Economic Value of Provincial Immigration Programs.” News release, April 11. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/media/releases/2012/2012-04-11.asp

—————–. 2012e. “Speaking Notes for the Honourable Jason Kenney, Minister of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism at the National Metropolis Conference, Toronto,” March 1. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/media/speeches/2012/2012-03-01.asp

—————–. 2013a. Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/publications/annual-report-2013/section4.asp#a1

—————–. 2013b. Facts and Figures: Immigration Overview — Permanent and Temporary Residents, 2012. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/statistics/facts2012/index.asp

—————–. 2013c. “New Federal Skilled Trades Program Accepts Applications Starting Today.” News release, January 2. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/media/releases/2013/2013-01-02.asp

—————–. 2013d. “Backgrounder — Provincial Nominee Program: Record Levels Planned for 2014.” Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/media/backgrounders/2013/2013-10-28a.asp

Council of the Federation. 2013. “Jobs and the Economy Key Priorities for Canada’s Premiers,” July 25. Ottawa: Council of the Federation. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.conseildelafederation.ca/phocadownload/newsroom-2013/jobs_and_economy_july25-final.pdf

Daily Commercial News. 2013. “New Brunswick Puts Temporary Hold on Provincial Nominee Program,” September 16. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.dcnonl.com/article/id56997

Derwing, T., and H. Krahn. 2008. “Attracting and Retaining Immigrants outside the Metropolis: Is the Pie Too Small for Everyone to Have a Piece? The Case of Edmonton, Alberta.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 9 (2): 185-202.

Dobrowolsky, A. 2013. “Nuancing Neoliberalism: Lessons from a Failed Immigration Experiment.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 14 (2): 197-218.

Fowlie, J. 2012. “Permanent Residence Fast Track Suspended over Low Success Rate, Pat Bell Says.” Vancouver Sun, November 16. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.vancouversun.com/news/o/+residence+fast+track+suspended+over+success+rate/7562630/story.html

Friesen, J. 2012. “Ontario Puts Ottawa ‘On Notice’ It Seeks More Immigrants.” Globe and Mail, November 16.

Graham, J. 2012. Global Montreal. “Maple Leaf Waving Crowd Protests Changes to Saskatchewan Immigration Rules.” Accessed November 23, 2013. https://globalnews.ca/news/245665/maple-leaf-waving-crowd-protests-changes-to-saskatchewan-immigration-rules/

Grant Thornton. 2012. Prince Edward Island Provincial Nominee Program: Evaluation Results, December 31. Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/ISPNPEVALU2012.pdf

Halliwell, C. 2013. No Shortage of Opportunity: Policy Ideas to Strengthen Canada’s Labour Market in the Coming Decade. IRPP Study 42. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Hunter, J. 2012. “B.C. Suspends Visa Program after Suspicious Surge in Applications.” Globe and Mail, November 16.

Joppke, C., and F.L. Seidle. 2012. “Concluding Observations.” In Immigrant Integration in Federal Countries, edited by C. Joppke and F.L. Seidle. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Leo, C. 2006. “Deep Federalism: Respecting Community Difference in National Policy.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 39 (3): 481-506.

Leo, C., and M. August. 2009. “The Multilevel Governance of Immigration and Settlement: Making Deep Federalism Work.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 42 (2): 491-510.

Manitoba. 2013. Office of the Auditor General. “Provincial Nominee Program for Business.” Accessed November 23, 2013. https://www.oag.mb.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/WEB-Chapter-7-Provincial-Nominee-Program-for-Business.pdf

Nakache, D., and S. D’Aoust. 2012. “Provincial/Territorial Nominee Programs: An Avenue to Permanent Residency for Low-Skilled Temporary Foreign Workers?” In Legislated Inequality: Temporary Labour Migration in Canada, edited by P.T. Lenard and C. Straehle. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Nova Scotia. 2013a. “Nova Scotia Nominee Program (PNP).” Accessed November 20, 2013. https://www.canadavisa.com/nova-scotia-provincial-nominee-program.html

—————–. 2013b. “Province Acts to Increase Number of Skilled Immigrants.” News release, February 27. Accessed November 20, 2013. https://novascotia.ca/news/release/?id=20130227010

O’Neil, P. 2012. “Kenney Rejects Alberta Push for Greater Say in Immigration.” Edmonton Journal, February 8.

Pandey, M., and J. Townsend. 2011. “Quantifying the Effects of the Provincial Nominee Programs.” Canadian Public Policy 37 (4): 495-512.

Paquet, M. 2012. “The Federalisation of Immigration and Integration.” Paper presented at the annual conference of the Canadian Political Science Association, June 15, Edmonton.

Quebec. 1999-2000. Immigration et Communautés culturelles. Rapports annuels de gestion. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://www.micc.gouv.qc.ca/fr/ministere/rapport-annuel.html

—————–. 2004-05. Immigration et Communautés culturelles. Rapports annuels de gestion. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://www.micc.gouv.qc.ca/fr/ministere/rapport-annuel.html

—————–. 2006-12. Immigration et Communautés culturelles. Bulletins statistiques trimestriel sur l’immigration permanente au Québec.

Reeve, I. 2013. “Lighting the Way: Linking Goals of Immigration to Canada’s Devolved and Centralized Approaches to Immigration Policy.” Paper presented at the conference “The Economics of Immigration,” October 18, Ottawa.

Seidle, F.L. 2010. The Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement:

Assessment and Options for Renewal. Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation Paper. Toronto: Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://www.mowatcentre.ca/pdfs/mowatResearch/12.pdf

Spiro, P. 2001. “Federalism and Immigration: Models and Trends.” International Social Science Journal 53 (167): 67-73.

Strazzari, D. 2012. “The Scope and Legal Limits of the ‘Immigration Federalism’: Some Comparative Remarks from the American, Belgian and the Italian Experiences.” European Journal of Legal Studies 5 (2): 95-137.

Vineberg, R.A. 1987. “Federal-Provincial Relations in Canadian Immigration.” Canadian Public Administration 30 (2): 299-317.

Worswick, C. 2013. Economic Implications of Recent Changes to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. IRPP Insight 4. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Young, R. 2011. Conclusion. In Immigrant Settlement Policy in Canadian Municipalities, edited by E. Tolley and R. Young. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Zhang, H. 2012. Centralized vs. Decentralized Immigrant Selection: An Assessment of the BC Experience. Metropolis British Columbia Working Paper Series 12-04. Accessed November 22, 2013. https://mbc.metropolis.net/assets/uploads/files/wp/2012/WP12-04.pdf

I wish to thank the present and past officials from Citizenship and Immigration Canada and the four provincial governments covered in this paper for the extensive information they provided through interviews and subsequent correspondence. I also appreciate the helpful comments provided by Tom Carter, France St-Hilaire, Erin Tolley, James Townsend, Phil Triadafilopoulos and Rob Vineberg. I am particularly grateful to Quinn Albaugh for the excellent assistance he provided at various stages of this research.

This publication was published as part of the Diversity, Immigration and Integration research program under the direction of France St-Hilaire. The manuscript was copy-edited by Mary Williams and proofread by Zofia Laubitz. Editorial coordination was by Francesca Worrall, production was by Chantal Létourneau and art direction was by Schumacher Design.

F. Leslie Seidle is research director of the Diversity, Immigration and Integration research program at the Institute for Research on Public Policy, senior program adviser with the Forum of Federations and a public policy consultant.

To cite this document:

Seidle, F. Leslie. 2013. Canada’s Provincial Nominee Immigration Programs: Securing Greater Policy Alignment. IRPP Study 43. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Montréal – À l’exception du Québec, qui a conclu sa propre entente avec Ottawa, les gouvernements provinciaux sélectionnent, par l’entremise des programmes des candidats des provinces (PCP), une part appréciable et grandissante des immigrants admis au pays. Mais selon une nouvelle étude de l’Institut de recherche en politiques publiques (IRPP), les dispositions des PCP ne prennent pas toujours en compte leur éventuelle interaction avec les autres programmes d’immigration et devraient faire l’objet d’une vision et d’un cadre communs négociés entre les gouvernements concernés.

Directeur du programme de recherche Diversité, immigration et intégration de l’IRPP, F. Leslie Seidle retrace dans cette étude l’évolution des PCP du Manitoba, de la Colombie-Britannique, de l’Alberta et de la Nouvelle-Écosse.

Et il les juge efficaces à plusieurs égards. Les provinces disposent ainsi de la souplesse nécessaire pour adapter leur PCP aux besoins de leur économie et de leur marché du travail ; les demandes sont traitées plus rapidement que celles du Programme fédéral des travailleurs qualifiés ; la situation économique des candidats est plutôt favorable, même dans les premières années suivant leur arrivée ; et un plus grand nombre de nouveaux arrivants s’établissent désormais hors des trois plus grandes provinces.

En revanche, leur application a soulevé de sérieux problèmes d’intégrité dans plusieurs provinces, surtout pour ce qui est des programmes d’investisseur. De plus, « certaines innovations ont pu être adoptées sans mesurer leurs effets sur l’ensemble du système d’immigration ». Ce qu’indique par exemple le recours croissant aux PCP pour permettre aux travailleurs étrangers temporaires d’accéder à la résidence permanente, une conséquence qui ne figure nulle part dans les objectifs des programmes. (Les critères de sélection qui s’appliquent à ces travailleurs diffèrent de ceux utilisés pour les candidats au Programme fédéral des travailleurs qualifiés.)

À la lumière de ces éléments, Leslie Seidle propose aux gouvernements fédéral, provinciaux et territoriaux de « définir conjointement une vision et un cadre pour les PCP, assortis d’objectifs communs, en vue de déterminer les futures orientations de ces importants programmes ». Il ajoute que l’on pourrait mettre sur pied « un groupe de travail chargé d’assurer l’échange régulier d’informations et de données, y compris sur la situation des candidats, afin d’améliorer la coordination et le partage de leçons que permettent souvent les processus intergouvernementaux ».

-30-

On peut télécharger sans frais l’étude Canada’s Provincial Nominee Immigration Programs: Securing Greater Policy Alignment, de F. Leslie Seidle, sur le site de l’Institut, au irpp.org.

Pour de plus amples détails ou pour solliciter une entrevue, veuillez contacter l’IRPP.

Pour recevoir par courriel le bulletin mensuel À propos de l’IRPP, veuillez vous abonner à son service de distribution au irpp.org.

Renseignements : Shirley Cardenas | Tél. : 514 594-6877 | scardenas@nullirpp.org