Souvent considérées comme des « traités modernes », les ententes sur les revendications territoriales globales (ERTG) sont l’un des moyens dont les Autochtones se servent pour tenter de corriger les pénibles séquelles des politiques coloniales du passé et d’établir avec l’État canadien des relations qui répondent de plus près à leurs aspirations sociales, économiques et politiques et mènent à une amélioration de leur qualité de vie. En 1975, les Cris d’Eeyou Istchee et les Inuits du Nunavik dans le Nord du Québec ont été les premières nations autochtones à signer une ERTG, la Convention de la Baie-James et du Nord québécois (CBJNQ). C’est là une expérience tout à fait pertinente si l’on veut comprendre les possibilités à long terme et les limites des ERTG. Quelles leçons peut-on tirer de cette expérience ? Les institutions de gouvernance établies en vertu de la CBJNQ ont-elles donné aux communautés cries et inuites les conditions, les outils et les ressources nécessaires pour redéfinir leurs relations avec la société dominante ?

Selon l’auteur de la présente étude, il convient d’être prudent dans l’évaluation des effets de la CBJNQ. Les communautés cries et inuites du Nord du Québec ont connu des transformations importantes, positives aussi bien que négatives, au cours des 30 dernières années. D’un point de vue strictement socioéconomique, leur qualité de vie a certes connu une amélioration sensible, mais contrairement à ce qu’on suppose souvent — et malgré une augmentation importante, depuis la signature de la convention, des transferts des gouvernements au titre des programmes sociaux et du développement des infrastructures —, la situation socio-économique actuelle de ces communautés n’est guère meilleure que celle de communautés autochtones similaires au Yukon, dans les Territoires du Nord-Ouest ou au Nunavut, qui ou bien n’ont pas signé de traité, ou bien n’en ont signé un qu’à une époque beaucoup plus récente.

Au-delà de son impact direct sur la situation socio- économique des Cris et des Inuits, c’est sans doute du point de vue du régime de gouvernance établi par la CBJNQ que celle-ci offre les enseignements les plus utiles. L’un des grands objectifs recherchés par les signataires autochtones de la convention était d’obtenir un contrôle plus étroit sur un environnement social et économique qui évoluait rapidement. Or, les premiers résultats se sont avérés décevants. À ses débuts, la mise en œuvre de la CBJNQ s’inspirait largement des modèles traditionnels, où c’est l’État qui dirige et qui contrôle le développement des communautés autochtones. Les relations avec les pouvoirs publics étaient marquées par l’absence de mécanismes formels pour le règlement des différends et la coordination intergouvernementale. Avec le temps, certaines des instances de gouvernance créées en vertu de la CJBNQ sont toutefois devenues des instruments importants pour les revendications politiques des Cris et des Inuits. Non seulement ont-elles contribué, au sein de ces communautés, au développement d’une expertise dans divers secteurs de la politique publique, mais elles ont aussi joué un rôle important du point de vue de la consolidation d’identités politiques régionales vigoureuses dans les territoires d’Eeyou Istchee et du Nunavik.

La principale leçon qu’on peut tirer de la CBJNQ tient peut-être au fait qu’en eux-mêmes, les traités ne changent pas la situation socioéconomique ou le bien-être général d’une communauté, non plus qu’ils modifient de façon radicale les fondements de ses relations avec l’État. À la longue, toutefois, et à la faveur d’un leadership proactif et d’une collaboration étroite entre toutes les parties concernées, les ERTG peuvent devenir des instruments qui permettent aux peuples autochtones d’établir avec l’État une relation de gouvernance qui reflète de plus près leurs aspirations sociales, économiques et politiques.

Un second enseignement qu’on peut tirer de l’expérience de la CBJNQ, c’est que les traités doivent s’adapter à l’évolution de la réalité sur le terrain. Ils ne sauraient être figés dans le temps. Cette notion a d’ailleurs été reconnue en 2001 dans la Paix des Braves, qui a conféré aux Cris des pouvoirs élargis sur leur propre développement économique et social. Il faut donc que les gouvernements reconnaissent que les accords de revendication territoriale sont beaucoup plus que des transactions foncières : ce sont des documents « vivants » qui établissent les paramètres généraux d’une relation de décolonisation appelée à se transformer à mesure qu’évolueront la situation et les priorités des signataires autochtones.

In its final report, released in 1996, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) documented the consequences of past government policies aimed at redesigning the cultural, political and economic fabric of Aboriginal societies in order to facilitate the integration of Aboriginal people into the dominant society. Residential schools are a wellknown example of such policies. So are the (still extant) reserve system and the Indian Act, through which Aboriginal community life came to be almost entirely regulated by federal civil servants. The consequences of these policies — family and community dislocation, economic dependency and a profound sense of alienation — persist across Canada.

If we are to move beyond this colonial legacy, the royal commission argued, we must change our perspective on the very nature of the relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the Canadian state. Echoing what many analysts and community activists have long argued, the RCAP suggested that the institutional basis of the relationship be redefined and rebalanced to enable Aboriginal peoples to regain a sense of agency and control over their lives, their lands and their dealings with the dominant society. Comprehensive land claim agreements (CLCAs), often referred to as “modern treaties,” are one means by which Aboriginal peoples have attempted to establish a governance relationship that better reflects their social, economic and political aspirations.

In 1975, the Eeyouch, or Crees, of Eeyou Istchee and the Inuit of Nunavik, in northern Quebec, became the first Aboriginal peoples to sign a CLCA — the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA). Their experience is therefore highly relevant to our understanding of the long-term potential and limits of CLCAs. What lessons can we learn from it? Have the institutions of governance created under the JBNQA regime provided the Cree and Inuit communities with the conditions, tools and resources to redefine their relationship with the dominant society and improve their quality of life?

This study, building on the abundant literature on the JBNQA and some primary research, addresses the key lessons we can learn from the implementation of the first modern treaty and its impact on the quality of life of the Crees and Inuit. It suggests that the experience of the JBNQA should be assessed with caution. Cree and Inuit communities have undergone significant changes, both positive and negative, in the past 30 years. In strict socio-economic terms, their overall quality of life has improved, but the causal link with the JBNQA is difficult to assess. Various analyses indicate that the changes observed since 1975 were already under way before the agreement was signed. Moreover, contrary to popular assumption, despite a significant increase in government transfers for social programs and infrastructure development in the aftermath of the JBNQA, Cree and Inuit communities in northern Quebec are not markedly better off than similar northern Aboriginal communities in Yukon, the Northwest Territories or Nunavut that do not have a treaty or that signed one much more recently.

Beyond its direct impact on Cree and Inuit social and economic conditions, it is perhaps in the evolution of the governance regime it set up that the JBNQA is most instructive. One of the key objectives of its Aboriginal signatories was to gain greater control over their rapidly changing social and economic environment. In addition to the pressure of natural resource extraction on their traditional lands, Cree and Inuit communities were experiencing rapid transformations associated with the transition from a subsistence to a wage-based economy. The JBNQA was an opportunity for them to have a say in guiding these transformations. In this respect, the governance structures defined by the agreement initially had mixed results; the JBQNA did not radically alter the relationship between the Crees, the Inuit and the Canadian state, nor did it enable the Crees and Inuit to play more than a marginal role in the economic development of the region.

In fact, the agreement largely reproduced old models of state-led and state-controlled development in Aboriginal communities. This study suggests that the problem lies not only with the agreement itself, but also — and perhaps more importantly — with the way it was interpreted and implemented by its federal and provincial government signatories. The absence of institutionalized mechanisms to facilitate exchange between Aboriginal administrations and their federal and provincial counterparts contributed to a lack of consistency and coherence in the governments’ implementation of the agreement.

With time, however, some of the governance bodies created under the JBNQA have become significant vehicles for the political assertion of the Crees and Inuit. They have not only contributed to the development of Cree and Inuit expertise in a number of policy fields, but also played an important role in the consolidation of strong regional political identities in Eeyou Istchee and Nunavik. Building on this expertise and sense of regional unity, the Crees and Inuit are now engaging in a profound redefinition of the JBNQA governance regime, adapting it to their contemporary expectations and realities. Recent agreements with Quebec and Ottawa reflect this new reality.

The experience of the Crees and Inuit under the JBNQA suggests that a CLCA is no panacea for Aboriginal peoples. In and of themselves, treaties do not change the socio-economic conditions and overall well-being of communities, nor do they radically alter the colonial structure that Daniel Salée identifies in his study for the IRPP as one of the main explanations for the “glacial pace” of changes in the living conditions of Canadian Aboriginal peoples (2006). But, over time, and with proactive leadership and collaboration between all parties involved, CLCAs can become the instruments whereby Aboriginal peoples establish a governance relationship that better reflects their social, economic and political aspirations.

What are modern treaties, and how do they relate to the quality of life of Aboriginal peoples? Before we examine the experience of the Crees and Inuit under the JBNQA, we should address the broader debate about the role of treaties for Aboriginal peoples and their contemporary relevance, and we should define what we mean by “quality of life.”

“Quality of life” is one of those terms that can be interpreted in a number of ways. The literature tackling the issue is replete with debate over the meaning and usefulness of the concept.1 Ideas about what constitutes “the good life” also vary considerably from one individual or community to another based on culture, environmental factors and life history, making generalizations somewhat difficult. But it is generally understood that quality of life involves more than income and standard of living. For example, a healthy body and environment, as well as a supportive community, are increasingly considered integral to a good life. Findlay and Wuttunee underline the importance of such factors for Aboriginal women seeking to improve their quality of life (2007, 6), and Salée points out that well-being in Aboriginal communities tends to be defined in more holistic terms, as a balance between different aspects of one’s surroundings (2006, 8). In James Bay Cree communities, for example, health is associated with miyupimaatisiiun, or “being alive well,” which in turn is closely related to one’s identification with and relationship to the land (Adelson 2000). Inuit share a similar perspective (Usher, Duhaime, and Searles 2003).

Adding to the complexity of the question, the nature of what affects our well-being can also shift over time. In the case of the Crees and Inuit, at the time of the JBNQA negotiation, protecting traditional lifestyles was a key objective. While hunting, trapping and fishing are still important, the younger Aboriginal leadership places a greater emphasis on finding a balance between sustaining traditional pursuits and improving access to the wage economy.

Despite these caveats, the highly diverse literature on the quality of life of Aboriginal peoples generally echoes the royal commission’s insistence that individuals and communities must regain a sense of control over their lives and their relations with the dominant society if they are to achieve well-being. In other words, as Salée concludes, the economic and social dimensions of well-being cannot be separated from issues of individual and collective political agency and self-determination (2006, 26). This is where treaty making comes into play.

Treaties have a long history in Canada. Peace and friendship alliances between Aboriginal nations shaped the political and economic map of North America long before the arrival of the Europeans (Williams 1997). The negotiation of treaties was also central to early relations between Aboriginal peoples and representatives of the French and British Crowns. At the time, treaties were diplomatic instruments designed to establish the parameters of coexistence as well as political and economic alliances between the European powers and Aboriginal nations.

British and Canadian officials continued to use treaties through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries — by then, however, treaties had become mechanisms for establishing authority for the purposes of colonial expansion. Through the so-called numbered treaties, Aboriginal peoples agreed to European settlement on their traditional territories in most of Ontario and the prairies in exchange for the protection of their traditional lifestyle and some minimal social and economic guarantees (Dickason 2002).

The record of the Canadian state with regard to the numbered treaties is far from exemplary. Many aspects of the agreements have simply been ignored, especially those related to the protection of reserved lands and the well-being of Aboriginal communities. Often, the written treaties prepared by government officials differed significantly from what was agreed upon during negotiations by Aboriginal peoples with oral, rather than written, legal traditions. These discrepancies, along with the tendency of the federal and provincial governments to define their treaty obligations restrictively, led to ongoing disputes between government and Aboriginal signatories over the interpretation of the content as well as the general spirit and intent of the treaties.2

Despite these limits, the principle of treaty making remains central to the way Aboriginal peoples conceive of their relationship with the Canadian state and society. It is thus not surprising that treaties have reemerged as an important means for Aboriginal peoples to assert their political agency, define their place in Canada and gain some control over their well-being.

The 1973 Calder decision of the Supreme Court of Canada marked the re-emergence of treaties in contemporary Canada. While the country’s highest tribunal ruled against the Nisga’a of British Columbia in the case, it nonetheless recognized the possibility that Aboriginal title to the land had survived the assertion of British and Canadian sovereignty in the absence of an explicit transfer of that title to the Crown.3

In the immediate aftermath of Calder, the federal government established a new land claim policy in order to negotiate settlements in areas where Aboriginal claims had not been addressed by historical treaties, as was the case in Quebec, British Columbia and most of the northern territories.4 The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement was the first CLCA achieved following Calder, while the federal land claim policy was still on the drawing board.

Twenty-one CLCAs have since been ratified and are in force; a few more are in the final stages of ratification.5 The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, which led to the creation of the Nunavut territory, and the Nisga’a Final Agreement in northern British Columbia are often cited as examples of recent CLCAs that have reshaped the way Aboriginal communities interact with the Canadian state. Aboriginal rights defined in a CLCA are protected under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. This obliges federal and provincial legislation and policies to be consistent with their obligations under modern treaties.

However, just as there are in the case of older treaties, there are significant divergences between Aboriginal peoples’ interpretation of modern treaties and that of the governments involved. For the federal government, the objective of a CLCA is “to obtain certainty respecting ownership, use and management of lands and resources by negotiating an exchange of claims to undefined Aboriginal rights for a clearly defined package of rights and benefits set out in a settlement agreement” (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada 2007, 1). Provinces and territories also have an interest in clarifying the nature of Aboriginal rights in order to facilitate access to the land for the purposes of economic development.

The JBNQA set a standard in this respect. In exchange for the specific rights defined in the agreement and the negotiated benefits package, the Aboriginal parties had to surrender any title to the land they may have possessed. Section 2.1 of the JBNQA is explicit: “In consideration of the rights and benefits herein set forth in [their] favour…the James Bay Crees and the Inuit of Quebec hereby cede, release, surrender and convey all their Native claims, rights, titles and interests, whatever they may be, in and to land in the territory and in Quebec, and Quebec and Canada accept such surrender” (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada 2004). The language of more recent agreements has been modified in response to charges — from the United Nations, among others — that such practice is unfair.6 But treaties, from a government perspective, remain first and foremost land transactions to ensure legal certainty and facilitate economic development.

By contrast, most Aboriginal people see modern treaties in much broader terms — more like the initial treaties with European powers. Modern treaties are not just one-time land-ownership deals. They are constitutive documents that lay the foundations of a renewed and ongoing relationship between mutually consenting and equal partners (Tully 2001). For most Aboriginal peoples, treaties are, ultimately, a means of decolonization, a way to regain political agency and engage with the state under new terms. As organic documents establishing the basis for future relationships, they are bound to evolve and grow with changing circumstances. At the same time, as they move through the various phases of their implementation, respect for their original spirit is at least as important as the specific legal obligations they impose (Irlbacher-Fox and Mills, forthcoming).

These two conceptions of the treaty process are difficult to reconcile, and this explains the mounting frustration of those involved in treaty negotiation and implementation. Some negotiations have been suspended and resumed again and again over a period of 30 years as negotiators struggle with legal obstacles and unilaterally set government preconditions. The experience of the Crees and Inuit under the JBNQA also suggests that federal, territorial and provincial governments approach modern treaties programmatically, showing little interest for an implementation process that reflects the Aboriginal perspective on a given treaty’s general spirit and decolonizing dimensions.7 Such obstacles have led many Aboriginal people to question the legitimacy and usefulness of CLCAs as instruments of decolonization. Many have opted instead to use the courts to force governments to recognize their rights in the face of growing development pressures on their traditional lands (Alcantara 2007).

Despite their many limitations, modern treaties are significant documents. Whether we interpret them strictly as compensation for land or more broadly as institutional frameworks for a renewed relationship, agreements like the JBNQA are profoundly transformative. They establish new obligations and responsibilities for governments as well as mechanisms and rules of governance in a wide array of policy areas. As such, they can have a direct impact on quality of life as well as on the governance of the communities involved.

Signed in November 1975, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement is a 456-page document covering a series of issues related to the governance of land and communities.8 As the first of its kind, the agreement breaks new ground in a number of areas, and many of its dispositions are echoed in subsequent CLCAs. But the JBNQA also reflects the unique context from which it arose.

It was the result of four years of mobilization and legal action by the Crees, later joined by Inuit and other Quebec Aboriginal peoples, who challenged the province’s right to proceed with the construction of the massive James Bay hydroelectric complex without their consent. Since no treaty had ever been signed in northern Quebec, Aboriginal peoples claimed that their ancestral rights to the land had to be acknowledged before any development could take place. Following a historic court decision, which partly confirmed their assertion, Quebec proposed an outof-court settlement.9

For Quebec, the primary motivation for negotiating a settlement was to ensure that the construction of its hydroelectric complex would go forward; the province also intended to use the JBNQA to assert its jurisdiction in the Far North, a territory added to the province in 1912.10 The federal government took part in the negotiation to fulfill its obligations regarding the settlement of Aboriginal titles and land claims. For the Crees, the main objective was to minimize the damage to their environment and ensure the sustainability of their traditional hunting, fishing and trapping activities. Billy Diamond, chief negotiator for the Grand Council of the Crees, stated that “the issue was not merely a land claim settlement: it was a fight for the survival of our way of life” (1985, 280).

The Inuit, however, were not immediately affected by the first phase of the hydroelectric project, and they were divided about joining the negotiation process. Inuit communities were already discussing political autonomy, and some saw the JBNQA as an opportunity to advance their project. Others believed that trading their Aboriginal rights for limited administrative decentralization, as proposed in the JBNQA negotiations, was an unacceptable course of action (Rodon and Grey, forthcoming). In the end, three Inuit communities did not endorse the final version of the agreement, even though they would be fully covered by its dispositions.

Living conditions and economic prospects were also a source of concern for Cree and Inuit leaders. At the time of the JBNQA negotiations, their communities were undergoing profound changes. For Inuit, notably, permanent-settlement life was still relatively new. They were also in transition from a subsistence to a wage-based economy (Martin 2005). The infrastructure in the communities was deficient, many villages did not have adequate education or health facilities, and basic services were almost nonexistent. A negotiated settlement would be an opportunity to improve living conditions and gain some control over the direction and pace of change (Awashish 1988; Watt 1988).

In exchange for $225 million (divided between the two groups), the Crees and Inuit agreed to a slightly modified version of the hydroelectric complex; in exchange for rights specified in the treaty, they surrendered their existing rights. The nature of the treaty rights varies according to a tri-level system of land tenure. Most of the 1,165,286 square kilometres of land covered by the agreement is category II and III lands — public lands available for development, on which the Crees and Inuit retain some hunting, fishing and trapping rights. These lands and their resources remain under Quebec jurisdiction. Category I lands — 8,151 square kilometres for the Inuit, and 5,600 square kilometres for the Crees — fall under local Aboriginal authority.11

Reflecting a preoccupation of the Crees and Inuit, the agreement also ensures the viability of their traditional activities. The Cree Income Security Program provides hunters and trappers with a basic income. The Inuit Hunting, Fishing and Trapping Support Program funds equipment and transportation for these traditional activities and promotes the sharing of harvest products (Kativik Regional Government 2003, 43). The protection of traditional activities is also an objective of a series of joint Aboriginal-federalprovincial committees for wildlife management and environmental monitoring on the territory of the agreement. However, these committees have only advisory powers, and their influence on government has been quite limited (Craik 2004; Rodon 2003).

This focus on protecting traditional activities contrasts sharply with the agreement’s approach to economic development. The JBNQA does little to guarantee that Crees and Inuit benefit from natural resource extraction on their lands: it does not provide for natural resource royalties, only a lump-sum settlement; and its Aboriginal signatories have no rights to surface or subsurface resources outside the limited scope of category I lands.12 As for improving social and economic conditions, sections 28 and 29 of the agreement simply establish a general federal and provincial responsibility to “assist and promote” social and economic development in the communities.

The element of the agreement most crucial for improving Cree and Inuit quality of life is certainly the transfer of responsibility for administering most government programs and services to a vast array of Creeand Inuit-run bodies. The Crees chose a mixed structure of Cree-specific governance under federal jurisdiction at the local level, and under Quebec jurisdiction at the regional level. Inuit, being a clear majority in Nunavik and being unhampered by the institutional legacy of the Indian Act, chose local and regional public governance structures under provincial jurisdiction; most of the regional administrative bodies are funded jointly by the federal and provincial governments. In Cree communities, responsibility for health and education was transferred from Ottawa to Quebec, and Quebec, in turn, created two Cree-run boards — the Cree School Board and the Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay — to deliver the services in Cree communities. Similar administrative structures were created in Nunavik.

In addition to responsibility for health and education, responsibility for the administration of justice, local policing, housing and municipal services was transferred to Cree and Inuit local and regional bodies. Two of these — the Cree Regional Authority (CRA) and the Kativik Regional Government (KRG) — came to administer most government programs and transfers on behalf of the communities.

The JBNQA is thus much more than a land claim settlement. It created a unique regime of governance, characterized by a web of administrative structures at the local and regional levels through which Crees and Inuit were expected to run most government programs and services in their communities. But the limits of what Rodon and Grey (forthcoming) define as a “highly fragmented” regime of administrative devolution rapidly became apparent in the early years of the agreement’s implementation.

Gauging the results of an agreement of this amplitude is a difficult enterprise. Many of the changes it brought — notably, changes in the internal dynamics of Cree and Inuit communities or in the relations of these communities with government authorities — are hard to quantify. Even when the changes are measurable, it is not always easy to identify a direct causal link with the agreement, as the comparative data presented in this section indicate.

Yet we can draw some conclusions about the impact of the JBNQA more than 30 years after its ratification.

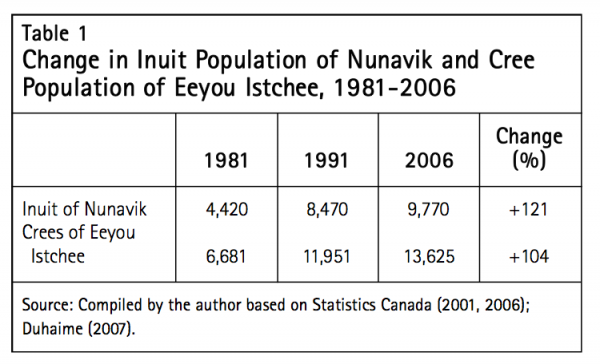

One very striking change in Cree and Inuit communities has been demographic growth. There were only about 4,000 Inuit and 6,000 Crees when the JBNQA was negotiated in 1975. Today, there are close to 10,000 Inuit and 14,000 Crees in northern Quebec (table 1). Although this trend has slowed in the past decade, if it continues, then the Cree and Inuit population could double again by 2027. This population is also very young: 35 percent of Crees and 39 percent of Inuit were under 15 years old in 2005.13

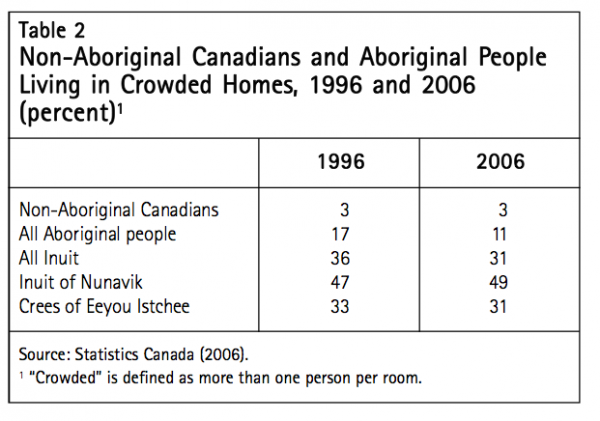

Population growth creates pressures on infrastructure — notably, those related to housing, schools and other public facilities. A key test for the JBNQA has been whether it has the capacity to adapt to these pressures and provide Crees and Inuit with the tools to respond to their changing demographic realities. Existing data suggest that the condition of roads, water supply and public buildings has improved significantly since the early 1980s in northern Quebec.14 The housing situation is less positive. Despite the large investments made since the signing of the JBNQA, Cree and Inuit houses remain far more crowded than those of non-Aboriginal Canadians. In fact, as table 2 suggests, housing conditions in northern Quebec are among the worst in the country and have not improved in the past 10 years. In Nunavik, the percentage of multiple-family households is the highest in the country, at 19 percent (Statistics Canada 2006).

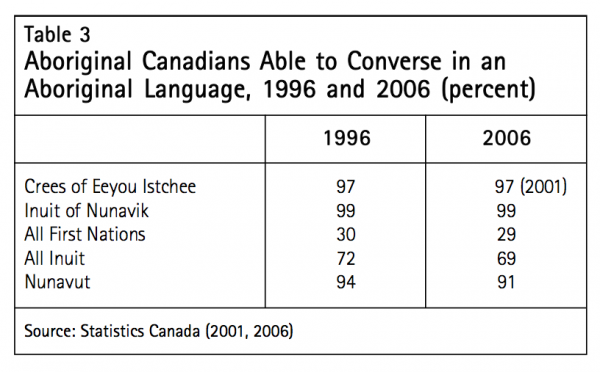

Creeand Inuit-controlled education is often touted as one of the great achievements of the JBNQA (Vick-Westgate 2002). While it is true that the school boards have given Crees and Inuit a much greater role in running their own education systems and the means to implement culturally relevant and environmentally aware programs, the picture is far from perfect. The good news is that the Aboriginal language retention rates of Crees and Inuit are among the highest in the country. This may be explained in part by the relative isolation of these communities from major population centres, but, as table 3 indicates, the proportion of Nunavik Inuit who can converse in Inuktitut and who speak the language at home is also significantly greater than the proportion of all Canadian Inuit, who are in a similar geographical position. The choice to provide early childhood and elementary education in Cree and Inuktitut certainly has a lot to do with the healthy state of Aboriginal languages in JBNQA communities.

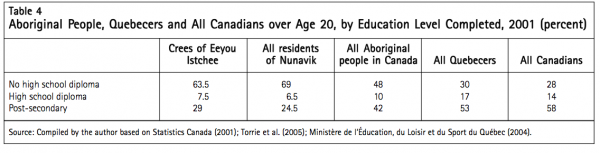

While Aboriginal language retention rates appear to indicate success, Cree and Inuit administrative control over education has not produced the expected levels and standards of education. The proportion of the Eeyou Istchee and Nunavik populations with a high school diploma or more increased between 1986 and 2001 — from 25 to 35 percent. But, as table 4 shows, the rate is still much lower than it is elsewhere in Quebec and in Aboriginal communities as a whole. Dropout rates at the Cree School Board and the Kativik School Board are the highest in Quebec, at 75 percent (Ministère de l’EÌducation, du Loisir et du Sport du QueÌbec 2004).

In signing the JBNQA, the Cree and Inuit had as a central objective the protection of their traditional way of life and the environment that supports it. In many ways, the agreement delivered. In early analyses of the impact of the JBNQA, the Cree Income Support Program and the Inuit Hunting, Fishing and Trapping Support Program are described as two of its most successful elements. According to Salisbury, the number of full-time Cree hunters increased by 50 percent between 1971 and 1981 as a result of the support programs (1986, 77). The programs did not stop the decline in traditional activities conducted on a full-time basis, but they certainly helped ease the transition to a wage-based economy. Given the importance of the connection to the land in Cree and Inuit cultures, this is a significant achievement of the JBNQA. While traditional activities now are part-time pursuits for the majority of Crees and Inuit, most adults still participate in them. In 2001, 77 percent of Crees did so, as did 81 percent of Inuit in Nunavik, compared with 70 percent in Nunavut (Statistics Canada 2001).

The decline in full-time traditional activities, combined with demographic pressures, has made job creation and access to the wage economy issues of major concern in Cree and Inuit communities. Consistent with the trend in most northern Aboriginal communities, wages now account for a much higher proportion of Cree and Inuit income than they once did: 73 percent of Cree income in 2001, compared to just 32 percent in 1971 (Torrie et al. 2005, 41). Between 1972 and 1983, full-time wage employment almost doubled in Nunavik, and the trend has continued (Chabot 2004).

The 2001 census data show an average individual income of $20,814 for the Crees of Eeyou Istchee, and $19,713 for residents of Nunavik.15 Considering the higher cost of living in the North, this is significantly lower in real terms than the Quebec average income ($27,125). It is also lower than the average income of inhabitants of Aboriginal communities in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories ($22,209); but it is comparable to that of other Aboriginal peoples in Quebec ($19,157). In 2006, unemployment rates in Nunavik (15.6 percent) and Eeyou Istchee (19.2 percent) were significantly higher than the Canadian average but slightly lower than those in Aboriginal communities in Nunavut (23.1 percent) and the Northwest Territories (18.4 percent).

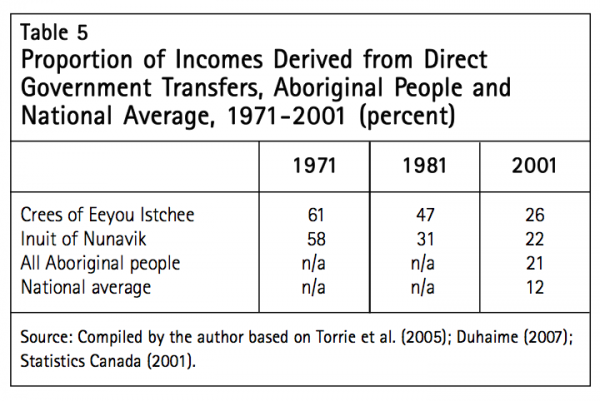

A key characteristic of the income structure in Cree and Inuit communities is that a relatively high proportion of overall income is derived from government sources. This high-dependency pattern was already well established by the time the JBNQA was signed, and the agreement has had a mixed impact on it. As table 5 indicates, the proportion of income deriving from direct government transfers such as unemployment insurance and social assistance has declined significantly in both Nunavik and Eeyou Istchee, but it is still twice as high as the Canadian average and marginally higher than the average in Aboriginal communities in general.

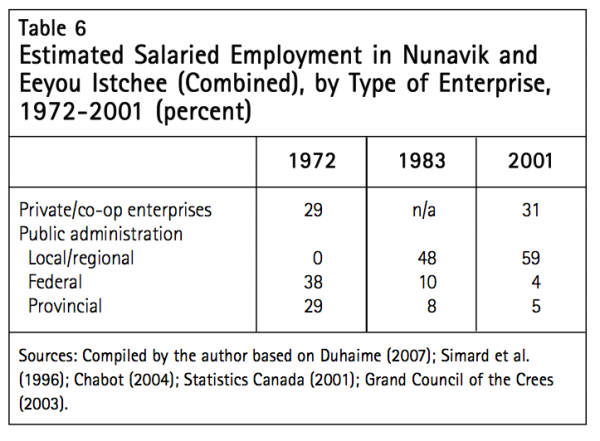

Though direct transfers have declined, the estimates presented in table 6 suggest that the regional wage economy is still dominated by the public sector.

Employment in education and health services, municipal services, capital projects and other public services, all funded through federal and provincial transfers, account for most of the jobs created in the region since the implementation of the JBNQA. Even when it comes to private sector employment, many enterprises were created and are supported by Cree and Inuit investments drawn from the compensation funds received in accordance with the JBNQA and subsequent agreements. And, with few exceptions, these private enterprises survive on contracts with the public sector. If we combine government salaries, investments drawn from compensation funds and direct income support, then we see that a large proportion of revenues in Nunavik and Eeyou Istchee still comes from government transfers.

This transfer economy, whether it is built on various forms of income support or on public service employment, has allowed Crees and Inuit to maintain a level of income comparable to that of most other Aboriginal peoples in the country. However, their communities are growing rapidly, and other sources of employment must be developed. Every year, 400 young Crees enter the labour force, and the public sector and the traditional economy alone cannot sustain them (Grand Council of the Crees 2005).

In a resource-rich region, job creation should stem from natural resource extraction activities. The limits of the JBNQA in this respect have become obvious over time. During various stages of the hydroelectric project, about 200 Crees and Inuit were employed, yet few were left with permanent positions once construction was completed. Forestry and mining are also important industries in the region, especially near the southernmost Cree communities, but in 2001, both industries combined employed less than 5 percent of the adult Cree population (Grand Council of the Crees 2003).

In striking contrast with this portrait, according to a 2004 study prepared for the Grand Council of the Crees, hydroelectric production on the JBNQA territory is an economic activity worth $3.5 billion annually, while the forestry and mining industries on traditional Cree lands generate $1.5 billion in annual revenues and sustain 15,000 workers (Fortin and Audenrode 2004). In Nunavik, mining is a growing industry as well (and the Inuit leadership has similarly sought guarantees that its communities will benefit from resource extraction, as I will discuss later).

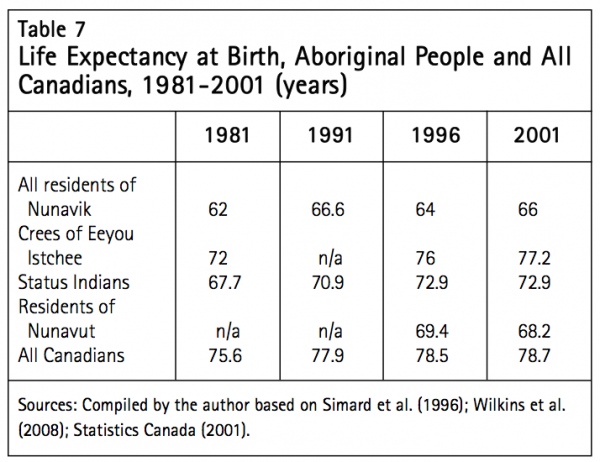

The health of Inuit and Crees has improved substantially with government investment in socio-sanitary infrastructures, health promotion programs and education. Like many other changes, however, these transformations are traceable to the period preceding the JBNQA; it is hard to make a clear causal link between the JBNQA and improvements evident in the decade following its implementation. Meanwhile, despite these improvements, the health situation in northern Cree and Inuit communities remains dire. Infant mortality rates decreased significantly in the 1980s and 1990s, but in 2001, the rate was still more than three times higher in Nunavik and Eeyou Istchee (15.2 and 12.6 per 1,000 births, respectively) than in Quebec overall (4.63 per 1,000) (Torrie et al. 2005; Wilkins et al. 2008). Moreover, as table 7 shows, if life expectancy is comparable to the Canadian average in Eeyou Istchee, it is more than 10 years lower than the Canadian average in Nunavik.

The accelerated pace of social and economic transformation in northern communities has also created new health problems. For example, in Cree communities, as the nature of economic activity has changed, the proportion of overweight and obese adults has increased greatly. In 2001, 87 percent of Cree adults and 56 percent of Cree children were overweight or obese, compared to 46 percent of all Canadians (Torrie et al. 2005).16

Other health issues have come to the fore in recent years in Cree and Inuit communities, revealing the degree to which the young population is still suffering from the psychological and physical consequences of social and economic shifts and of disempowering government policies. High levels of depression, alcohol abuse, family violence and poor nutrition (leading to diabetes and cardiovascular disease) indicate that these communities are under profound stress (Hodgins 1997). For example, Nunavik’s suicide rate is one of the highest in the world, which may partially explain the region’s lower life expectancy. In 2001, 68 percent of Inuit in Nunavik considered alcohol and drug abuse to be a major issue in their community, while 66 percent saw suicide as a primary concern (Statistics Canada 2001).

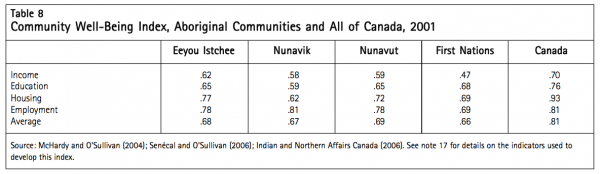

My analysis thus suggests that in terms of infrastructure, health, education and income, the situation in Eeyou Istchee and Nunavik has improved since the 1970s, but it is still far worse than in most nonAboriginal Canadian communities and only marginally better than in comparable Aboriginal communities. This conclusion is supported by the work of a team of researchers associated with Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, who developed a comparative measuring tool to assess the well-being of Aboriginal communities in Canada.

The Community Well-Being (CWB) Index was created using 2001 census data on, among other things, income level, employment, housing and education.17 While it presents a view of well-being that is not completely attuned to Cree and Inuit perspectives and that overlooks important dimensions of well-being such as personal health and environment, the CWB Index supports my conclusions. As the data presented in table 8 suggest, the CWB Index scores for the Crees of Eeyou Istchee are slightly above the average for First Nations communities in Canada in most categories, especially income and employment. However, the scores for the Inuit of Nunavik are slightly below those of communities in Nunavut. The gap is largest in housing and education; employment fares better. Both groups, however, fall significantly below Canadian averages in most categories.

In other words, if the JBNQA has had an impact over time, it has not dramatically altered the previously established trajectory and pace of change in living conditions in Eeyou Istchee and Nunavik compared to similar Aboriginal communities in other northern regions of the country. Part of the explanation for this may be related to the way in which the JBNQA has been implemented by governments rather than to the content of the agreement itself.

Crees and Inuit had high expectations when the time came to implement the agreement. They were, as a Cree leader claimed after the ratification ceremony, “taking their future into their own hands” (Diamond 1985, 268). But turning the agreement into concrete action was far more difficult than they had expected. Cree and Inuit administrators, and the numerous consultants hired to help operate the new structures, spent most of their time and energy navigating federal and provincial bureaucracies to obtain the necessary ministerial authorization or to negotiate their operational budgets instead of working toward the actual development of programs that reflected community priorities (LaRusic 1979).

Part of the problem was the absence of an implementation blueprint (Peters 1989). The federal and provincial governments did not have a timeline to proceed with the adaptations to their legislative and regulatory frameworks necessary to make room for the new reality of northern Quebec. Once the agreement was signed, it was business as usual. It was not until 1984, after a highly critical internal report was issued, that the federal government adopted the CreeNaskapi (of Quebec) Act, finally enabling Cree bands to exercise their local autonomy outside the framework of the Indian Act.

Adding to this lack of a clear implementation strategy was the fact that the agreement did not provide for a dispute resolution mechanism or a permanent intergovernmental forum through which dialogue could be conducted on implementation issues. Problems were dealt with as they arose, often after intense lobbying on the part of Cree and Inuit leaders for the attention of federal or provincial bureaucrats and elected officials. The problem was further compounded in relations with Quebec as Crees and Inuit had to deal with a wide array of departments — from education, to health, to natural resources — not all equally familiar with the JBNQA. This lack of institutionalized mechanisms to facilitate exchange contributed to the lack of consistency and coherence in governments’ approaches to the implementation of the agreement.

Many of the local and regional structures created under the JBNQA also found that the scope of their actions was considerably limited by the fact that they were conceived as administrative arms of the federal and provincial governments. The Quebec government, for example, saw the health and education boards not as Cree and Inuit governing structures but as extensions of its own administrative apparatus. Like other government service delivery agencies, the boards had their priorities established in Quebec City, not in the North.

The governance structures established under the JBNQA thus proved to be far more constraining than Cree and Inuit leaders had expected. The bottom line is that two visions of the agreement collided. For the Crees and Inuit, the agreement redefined the very basis of their relationship with Quebec and Canada as a partnership between mutually consenting governing partners engaged in a process to improve the living conditions of the communities. By contrast, the federal and provincial governments interpreted the agreement in light of their existing policies and approaches to Aboriginal governance. Cree and Inuit organizations and administrative bodies were considered integral to existing government apparatus — mere agents of the state. Participants in a colloquium evaluating the impact of the JBNQA 10 years after its ratification concluded, “Rather than allow for the administration of native affairs to be put in the hands of those most concerned, the Agreement gave rise to a plethora of committees and commissions whose powers overlap to such an extent that no one knows exactly who is responsible for what…The role of native representatives in those bodies is mostly symbolic and most of the time, governments make policy decisions without consultation. Governments have maintained their administrative and political control over the Crees and Inuit” (Vincent and Bowers 1988, 14).

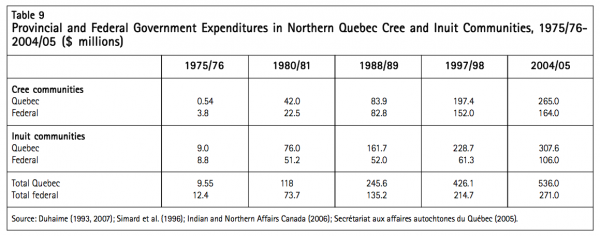

The Crees and Inuit also signed the JBNQA with the expectation that governments would provide the necessary financial support to run the new governance structures established at the regional and local levels. Significant investments were necessary to upgrade the level of services in the region and support the communities in their transition to a wage-based economy. The agreement did indeed bring a massive infusion of government funds into the region to support the devolution process. As the data presented in table 9 suggest, federal and provincial expenditures in Cree and Inuit communities grew considerably in the years immediately following the agreement and have continued to grow. The numbers are particularly striking in the case of Quebec, whose involvement in northern Aboriginal communities was minimal before 1976.

While the numbers are certainly impressive, we should put them in perspective. In terms of funding for services and infrastructure, expenditures in its northern regions represented about 0.1 percent of Quebec’s total budget the year of the JBNQA’s signing and reached a high of 0.57 percent between 1978 and 1982. They have declined in proportion ever since. In fact, if one takes into account population growth and inflation, overall government expenditures in Cree and Inuit communities grew by only 20 percent between 1981 and 1989, the core period during which all the administrative structures and programs resulting from the JBNQA were put in place (Simard et al. 1996, 48).

Despite the significant injection of funds that followed the JBNQA, funding of regional governance structures has been a constant source of tension. As they did when it came to program content, the federal and provincial governments viewed their JBNQA funding obligations strictly within the scope of existing budgets for Aboriginal communities. This meant that beyond the initial start-up funds for decentralized administrative structures, the share of federal and provincial budgets allocated for Cree and Inuit education, housing, health care and other services would be based on the standard funding formula used for other Aboriginal communities across the country (federal funds) and for non-Aboriginal communities in Quebec (provincial funds). The specific reality of the North and the political nature of the JBNQA were simply not acknowledged. As early as 1982, a federal task force mandated to review the implementation of the agreement concluded that while “Canada has not breached the agreement as a matter of law…the spirit of the JBNQA clearly called for a commitment beyond that of existing programs” (Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development 1982, 9).

Constraints related to program content, tight administrative control and tight budgets certainly go a long way toward explaining why improvement in the well-being of Cree and Inuit communities is only marginally greater than it is in other, similar Aboriginal communities that did not sign a CLCA 30 years ago. The JBNQA did give more responsibility to Crees and Inuit for administering the programs, but, with only a few exceptions (such as in education and language training), it did not provide them with significant new opportunities to create community-relevant social policies and promote economic development, nor did it change the general spirit of the relationship between the governments and the people of Eeyou Istchee and Nunavik. Ensuring that the spirit of the agreement would translate into concrete government commitments took years of effort on the part of the Crees and Inuit.

The discussion so far suggests that the JBNQA has not significantly improved the well-being of Crees and Inuit relative to that of other Aboriginal communities. Moreover, the governance structures and funding mechanisms it established have not altered the pattern of dependency on governments. Despite these mitigated conclusions, and while they often criticize federal and provincial implementation of the agreement, Cree and Inuit leaders are generally positive about the changes the JBNQA has brought about. In a message commemorating the 30th anniversary of the founding of the Grand Council of the Crees (GCC), Grand Chief Ted Moses celebrated the agreement negotiated by the Cree leadership as “better than any agreements signed by Aboriginal nations since” (GCC 2004, 6). Similar positive comments are often made on behalf of the Inuit (see, for example, Aatami 2002).

In fact, the value of the JBNQA can be fully appreciated only in the long term, and with a conception of quality of life that takes into account social and economic outcomes as well as the progressive transformations of Cree and Inuit societies at multiple levels — including the political. From this perspective, despite their inherent limits, the governing structures and organizations that have emerged from the JBNQA negotiations have become for the Crees and Inuit significant instruments for change.

At the time of the signing of the agreement, Cree and Inuit communities were only loosely integrated at the regional level. The cooperative movement had favoured some exchanges in the Inuit region, but no permanent regional structure existed to connect Inuit beyond their villages (Martin 2005). The same was true of the Crees, who had only started to articulate a common political vision during the JBNQA negotiations (Salisbury 1986).

A major outcome of the JBNQA has been the consolidation of Cree and Inuit identities and political unity at the regional level. Clearly, there were, and are still, dissenting voices. The Inuit were deeply divided in the aftermath of the JBNQA negotiations. But both groups have since achieved a degree of cohesion that has significant political repercussions. In their very self-definition as the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee and the Inuit of Nunavik, the two groups suggest the formation of regional societies, or nations, that transcend community differences.

The two regional organizations mandated by the communities to protect and promote their interests after the JBNQA ratification have played a central role in this nation-building process. The Grand Council of the Crees and Makivik Corporation have different statuses and roles, but both are political vehicles for the Crees and Inuit to define their collective priorities beyond village units and to establish a coherent front in relations with the federal and provincial governments. Presenting themselves as unified political entities in defending their interpretation of the JBNQA in the Quebec, Canadian and international arenas, the Crees and Inuit have redefined the boundaries of their polity from local to regional (Rousseau 2001; Jenson and Papillon 2000).

The regional administrative bodies created under the JBNQA have also been important to this nation-building process. Beyond playing a service delivery role, they have developed common approaches to, and standards of, health care, education and other services across the communities. The struggle of one community to gain access to adequate health or education services, for example, becomes a struggle for all the communities, and this gives rise to a strong sense of solidarity.

The emergence of this regional solidarity and sense of political agency is significant for communities that are battling against the deeply ingrained logic of command-and-control governance associated with the Indian Act that was largely reproduced in the JBNQA. Armed with a powerful sense of legitimacy and a coherent vision for their respective region-nations, the GCC, Makivik and other administrative bodies operating under Cree and Inuit control have tried to reshape the governance regime of the JBNQA.

A first example of this incremental transformation is the growing policy autonomy exercised by regional entities such as the school boards. Conducting policy development exercises and constantly asserting their autonomy from Quebec, the two boards have been engaged in recent years in a challenging yet vital redefinition of culturally relevant approaches to education in Eeyou Istchee and Nunavik in order to be more responsive to the reality of young Crees and Inuit. In taking ownership of education, the boards still had to undertake some push and pull with Quebec, and their programs have perhaps not been as successful as they would have hoped, but the content of the programs and the approach adopted are a product of Cree and Inuit choices (Vick-Westgate 2002). In 2004, the Cree School Board (CSB) employed 569 educators, technicians, professionals and administrative staff and had a budget of $93.4 million (CSB 2004).

The relative success of the school boards can be attributed not only to the resources transferred from Quebec and Ottawa, but also to the gradual development of a strong policy capacity within the organizations themselves, aided by external and internal expertise. Thus prepared, the boards engaged with Quebec in policy negotiations with relatively clear expectations and objectives. Community consultation and the active involvement of parents and local leaders in the management of the education system are also important elements of the school boards’ policy work. Finally, the boards’ relationship with Quebec’s Ministère de l’Éducation was also facilitated by the creation of a relatively stable and open channel of communication at the administrative level and the ministry’s eventual recognition that the unique status of the two JBNQA school boards called for a differentiated administrative approach.18

The Cree Regional Authority and the Kativik Regional Government have also developed an expertise and a capacity that extend far beyond that demanded by their initial role. Over the past 10 years, through the negotiation of administrative agreements, both bodies have gained new funding authority and new responsibilities in a number of areas. As an illustration, the Grand Council of the Crees and the Cree Regional Authority (CRA) combined now employ 154 people in five departments to run programs in areas such as human resources development, child care and family services, housing, environmental protection, forestry management, economic development, the promotion of traditional pursuits, policing and culture. In 2005-06, the combined structure of the GCC/CRA managed federal and provincial transfers valued at close to $190 million (GCC 2006).

The need to negotiate administrative transfer agreements puts these programs at the mercy of government policy changes, but they nonetheless create a space, or a margin, for Crees and Inuit to define their own policy priorities within the boundaries of the regime. Now — unlike the situation in the early years of JBNQA implementation, when Quebec and Ottawa could impose unilaterally the terms of the transfers — these transfer agreements are the result of multilevel governance exercises in which Cree and Inuit negotiators have their own well-developed policy objectives and priorities. As a representative of Makivik involved in a number of negotiations explained in an interview, using the resources at their disposal, they have “maximized the ambiguity” of the JBNQA and progressively gained de facto control over most aspects of government activity in the region.19 Cree and Inuit organizations have also developed expertise in intergovernmental relations and in the negotiation of political and administrative agreements. They have progressively gained better access to government officials in key positions and established more formal processes to facilitate exchange at both the political and administrative levels. The federal and provincial governments eventually established administrative structures to ensure that their activities conformed to the implementation of the JBNQA. More recent agreements with the Crees and Inuit also led to the creation of permanent liaison committees that include high-ranking civil servants and elected officials in order to facilitate the circulation of information at the executive level.

The incremental transformation of the JBNQA has also been achieved through more direct and confrontational approaches. The Grand Council of the Crees, in particular, has developed alternative strategies when negotiations have not produced results. In addition to using international political forums to bring world attention to the Crees’ situation,20 the GCC has aired a number of contentious issues in court — such as those related to the funding formula for the Cree School Board and local Cree bands and forestry management on category II and category III lands.

The mechanisms and strategies used may vary, but the outcome remains the same. The federal and provincial governments were progressively forced to engage with Cree and Inuit organizations in a fundamentally different way than they initially did in the early stages of the CLCA implementation. Rather than imposing their own priorities and views, governments increasingly involve themselves in negotiations, in finding compromises with the priorities and views of the Crees and Inuit. In effect, the JBNQA regime has evolved into a political relationship that goes much farther than classic administrative decentralization. And through such incremental shifts in the dynamic of governance, the Crees and Inuit are gaining greater agency in defining the conditions of their well-being.

As they take more responsibility for developing policies that correspond to their social reality, Crees and Inuit are challenging the colonial structures of economic relations that were largely reproduced with the JBNQA. I have already mentioned the pressures that demographic growth has exerted on the fairly limited job market of the region — a market essentially driven by a public service economy. Breaking that dependency and finding new sources of employment — notably, in natural resource extraction — has become a priority for the leadership of both groups.

It is with these economic issues in mind that the Crees agreed to sign the Paix des Braves with Quebec in 2001.21 In what was described as a “nation to nation” agreement, Quebec agreed to greater Cree participation in the economy of the region through, among other things, the creation of new co-management mechanisms for the exploitation of forestry and guarantees regarding Cree employment in the sector. Quebec also transferred its responsibilities under the JBNQA for regional economic and social development to the Cree Regional Authority. One of the agreement’s more important innovations is the mechanism through which funds for economic development are transferred to the Crees. The basic amount transferred over a period of 50 years following the signing of the agreement ($70 million annually) is indexed to the annual value of natural resource extraction (including that related to forestry, mining and hydroelectric production) in Cree territories.22 The trade-off was that the Crees agreed to withdraw all judicial proceedings against Quebec in matters relating to the agreement. More importantly, the GCC gave its consent to a new hydroelectric project (the Eastmain 1-A and Rupert River Diversion Hydropower Project) and agreed to cease its opposition to an extension of the existing La Grande complex.

The Paix des Braves is not a new treaty, nor does it recognize any form of shared sovereignty over the territory. In substance, it is an agreement on the implementation of Quebec’s JBNQA obligations, but it actualizes the JBNQA regime in relation to regional economic development and natural resource extraction to adapt it to the new economic and political reality of the Crees. In political terms, it was clear that Quebec could no longer deal with the Crees as an administered group and simply impose its own development priorities on them. It had to engage in an open-ended negotiation that recognized Cree interests and the mutual nature of the relationship. The Paix des Braves may not radically alter the JBNQA regime, but it certainly changes the tenor of Cree-Quebec relations pertaining to the management of natural resources and regional economic development.

A few months after signing the Paix des Braves, Quebec signed a similar agreement with the Inuit. While it received far less media attention, the Sanarrutik agreement also established a new partnership to accelerate economic and community development. In addition to launching a $350-million fund for social and economic development in the region, Quebec committed new monies for infrastructure and for feasibility studies for natural resource extraction projects. The agreement also sought to facilitate partnerships with the private sector to encourage greater Inuit participation in the mining sector. In the same spirit, the Inuit had negotiated an agreement in 1995 with the mining giant Falconbridge (now Xstrata) for a share in the exploitation of the Raglan nickel mine. The agreement established a compensation scheme based on the annual value of mineral extraction and also provided for Inuit employment at the site. In 2003, the mine employed 73 Inuit, representing 15 percent of the workforce.23

The impact of these agreements on the economy of the region and on the well-being of Crees and Inuit is still hard to measure. But their existence does suggest a significant realignment of governance of the northern economy. It would be hard to imagine Quebec going forward with a major development project now without first obtaining the consent of the Crees and Inuit and without negotiating a revenue-sharing arrangement. This contrasts sharply with the situation that prevailed in the early years of the JBNQA regime.

Another element to consider in any discussion of Cree and Inuit quality of life is the consequences of the priorities established by the communities as they embarked on a strategy of economic development based on natural resource extraction. There was strong opposition to the Paix des Braves in some Cree communities because a new hydroelectric project would have a significant impact on their immediate environment. It wasn’t clear to them why they should sacrifice yet a little more of their connection to the land — which they consider essential to their well-being — in exchange for more dependency money. The Crees were, in effect, faced with two conceptions of their well-being: one valuing Cree traditions and connection to the land; and the other focusing on their integration into the economy of the region.24

All of these transformations in Cree and Inuit governance are taking place within the JBNQA framework. While they certainly modify existing practices, they do not fundamentally alter the structure of the JBNQA regime. As I have pointed out, there is a growing disconnect between the model of governance established by the JBNQA and the contemporary reality of Eeyou Istchee and Nunavik. The growing influence and policy capacity of regional organizations and the related consolidation of strong regional identities among the Crees and Inuit need to be recognized in institutional terms.

This is precisely what the two groups are seeking to accomplish through projects aimed at creating regional governments to replace — or, more accurately, bring together — the various administrative bodies and political organizations that have emerged from the JBNQA. The idea of a regional government for Nunavik is not new. It was discussed as early as 1970, before the JBNQA institutions were put in place (Martin 2005). It has re-emerged regularly since. In 2001, the Nunavik Commission, a tripartite federal-provincial-Inuit task force responsible for recommending a “form of public government for the region…that can operate within federal and provincial jurisdictions,” tabled its report (Indian and Northern Affaires Canada 2001, 1). The commission recommended the creation of an elected regional assembly with powers delegated from the provincial governmen t.

The first step will be the fusion of the various organizations currently administering services on behalf of Nunavik residents.25 The agreement-in-principle for the creation of this new government and the merger of the three main regional bodies — the Kativik Regional Government, the Kativik School Board and the Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services — was signed by federal, provincial and Inuit representatives in December 2007. The powers that will be delegated to the Nunavik government are not substantially different from those currently exercised by the three administrative bodies. The main difference is that as departments of a regional government, these bodies will no longer have direct ties to ministries in Quebec. Instead, they will be accountable to the elected regional assembly.

The Crees have their own project to create a government for Eeyou Istchee. The idea of replacing the existing governing structures of the Grand Council of the Crees, the Cree Regional Authority and the other administrative bodies with a single elected entity emerged during the 1995 Quebec referendum as part of a reflection on the future of Eeyou Istchee. The project resurfaced in negotiations with the federal government regarding the JBNQA implementation. A Cree-Canada agreement similar in scope to the Paix des Braves was announced in July 2007.26 In addition to a financial package resolving outstanding federal obligations and future ones for a period of 20 years, the agreement launched the project of a Cree government to replace the existing local and regional administrative structures. Unlike their counterparts in Nunavik, who chose a regional public government, the Crees have chosen an Aboriginal-only self-government model with a more limited land base, similar to the one created under the Nisga’a Final Agreement.

Through these reform projects, the Crees and Inuit are seeking to redefine the governance framework inherited from the JBNQA in order to adapt it to their contemporary reality. In both cases, the model proposed will be clearly established within the legal boundaries of the Constitution of Canada. They do not represent a radical break with existing structures — although there is no precedent for a regional public government within a province, which Nunavik is bound to become. This transition from the JBNQA model of administrative governance to autonomous government certainly reflects the evolution of the two groups in their relations with the federal and provincial governments.

What lessons can we learn from the experience of the Crees of Eeyou Istchee and the Inuit of Nunavik under the first modern treaty? To begin, we can learn from the JBNQA’s mistakes. The agreement proved to have severe limitations. The surrender clause, which called upon the Crees and Inuit to abandon any remaining Aboriginal rights they held over the lands covered by the agreement, has certainly been a source of controversy. The agreement’s relative paucity of guarantees regarding the sharing of natural resources and the participation of the Crees and Inuit in the economy of the region is another source of criticism. Finally, and perhaps more importantly, the lack of clear guidelines and effective dispute resolution mechanisms to compel governments to implement the agreement in a manner consistent with its initial intent considerably limited its impact as a transformative tool for the Crees and Inuit.

The impact of the agreement on the social and economic conditions of the communities has also been mixed. The living conditions of the Crees and Inuit have certainly improved in the past 30 years, but comparative data suggest that they might well have improved without the JBNQA. In fact, the state of Cree and Inuit communities under the JBNQA is today only slightly better than or comparable to that of similar Aboriginal communities in other northern regions of the country — and, treaty or no treaty, Aboriginal peoples in Canada, and especially those in northern regions, endure far more difficult living conditions than non-Aboriginal Canadians.

The most significant lessons we can draw from the JBNQA experience are perhaps those related to the progressive transformation of the regime of administrative governance established at the regional level. The federal and provincial governments initially considered Cree and Inuit organizations and administrative bodies created under the JBNQA as an integral part of existing government apparatus. As a result, the capacity of Cree and Inuit communities to chart their own courses was severely curtailed. In fact, as many commentators have argued, the complex structures of the JBNQA simply shifted the burden of administration onto the Crees and Inuit while denying them more power to define their own priorities. However, with time, the governance bodies created under the JBNQA have evolved into significant vehicles for the political assertion of the Crees and Inuit.

The experience of the Crees of Eeyou Istchee and the Inuit of Nunavik under the JBNQA suggests that modern treaties are no panacea for the problems of northern Aboriginal communities. But CLCAs also provide a legal and institutional basis from which Aboriginal peoples can, over time, gain greater control over their quality of life. An agreement’s content certainly matters in this respect, but the way in which it is interpreted and adapted to changing circumstances is also very important. The Crees and Inuit have managed to transform a constraining regime of administrative decentralization into a much more complex regime under which they have far greater power to define the policy priorities, programs and orientations of their regional and local governing bodies. Faced with demographic pressures and an overdependence on government transfers, the Crees and Inuit have also repositioned themselves to take better advantage of the natural resource extraction economy of the region. Again, they have achieved this largely by adapting the JBNQA regime.

Another important lesson we can take from the JBNQA experience is thus that treaties must evolve and adjust to changing realities on the ground. As a means for Aboriginal peoples to redefine their relationship with the state and take charge of their social, economic and political conditions, they cannot be frozen in time. Governments should therefore acknowledge that land claims settlements are much more than land transactions: they are living documents that establish broad parameters for a decolonizing relationship that is bound to change as the conditions and priorities of the Aboriginal signatories change.

Yet another, related, lesson is that beyond implementation blueprints and clear objectives, which were clearly lacking for the JBNQA, formal institutional mechanisms to facilitate exchanges and negotiations between government agencies and Aboriginal organizations are also an essential part of a constructive governance relationship. The Crees and Inuit expended considerable energy simply trying to establish communication channels with relevant government authorities. Formal intergovernmental structures are not only essential to the process of developing policies and programs that resonate with the reality of the communities, they are also a form of recognition of the political — rather than merely administrative — nature of the relationship.

A final lesson is that agency matters. It is because of the ongoing mobilization and effort of Cree and Inuit leaders and organizations that the JBNQA regime was gradually transformed and adapted to the reality on the ground. Ultimately, no matter what the nature of the treaty is, Aboriginal peoples are the architects of change when it comes to their own quality of life. The negotiation of a treaty is the beginning, not the end, of a long transformative process, and it cannot succeed without strong leadership as well as responsive local and regional organizations capable of articulating their communities’ priorities for the future.

Aatami, Pita. 2002. “Speech to the Colloquium Reflections on the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement.’” In Regard sur la Convention de la Baie-James et du Nord québécois/Reflections on the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, edited by Alain-G. Gagnon and Guy Rocher. Montreal: Québec Amérique.

Adelson, Naomi. 2000. Being Alive Well: Health and the Politics of Cree Well-Being. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Alcantara, Christopher. 2007. “To Treaty or Not to Treaty? Aboriginal Peoples and Comprehensive Land Claims Negotiations in Canada.” Publius 38:343-69.

Awashish, Philip. 1988. “The Stakes for the Cree of Quebec.” In James Bay and Northern Quebec: Ten Years After, edited by Sylvie Vincent and Garry Bowers. Montreal: Recherches amérindiennes au Québec.

Chabot, Marcelle. 2004. “Consumption and Standards of Living of the Quebec Inuit: Cultural Permanence and Discontinuities.” Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 41 (2): 147-70.

Craik, Brian. 2004. “The Importance of Working Together: Exclusions, Conflicts and Participation in James Bay, Quebec.” In In the Way of Development: Indigenous Peoples, Life Projects and Globalization, edited by Mario Blaser, Harvey Feit, and Glenn McRae. Ottawa: Zed Books, Canadian International Development Research Centre.

Cree School Board. 2004. Annual Report 2002-2003. Mistissini, QC: Cree School Board.

Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND). 1982. James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement Implementation Review, February. Ottawa: DIAND.

Diamond, Billy. 1985. “Aboriginal Rights: The James Bay Experience.” In The Quest for Justice: Aboriginal Peoples and Aboriginal Rights, edited by Menno Boldt and J. Anthony Long. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Dickason, Olive P. 2002. Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times. 3rd ed. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press.

Duhaime, Gérard. 1993. “La gouverne du Nunavik: Qui paie quoi?” Canadian Journal of Native Studies 13 (21): 251-77.

_____.2007. Socio-Economic Profile of Nunavik 2006. Quebec: Chaire de recherche du Canada sur la condition autochtone comparée, Université Laval. Accessed July 5, 2008. https://www.chaireconditionautochtone.fss.ulaval. ca/extranet/doc/147.pdf

Findlay, Isobel, and Wanda Wuttunee. 2007. “Aboriginal Women’s Community Economic Development: Measuring and Promoting Success.” IRPP Choices 13 (4). Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Fortin, Pierre, and Marc Van Audenrode. 2004. “The Impact of the James Bay Development on the Canadian Economy.” Paper prepared for the Grand Council of the Crees. Montreal: Groupe d’analyse.

Gagnon, Alain-G., and Guy Rocher, eds. 2002. In Regard sur la Convention de la Baie-James et du Nord québécois/Reflections on the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. Montreal: Québec Amérique.

Government of Quebec. 1975. The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. Quebec: Government of Quebec.

Grand Council of the Crees. 2003. 2004. 2005. 2006. Annual Report. Montreal: Les Entreprises Serge Lemieux.

Hodgins, Stephen. 1997. Health and What Affects It in Nunavik: How Is the Situation Changing? Kuujjuaq, QC: Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services.

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC). 1999. Nisga’a Final Agreement. Ottawa: INAC. Accessed July 24, 2008. https://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/agr/nsga/index_e.html

_ _ _ _ _. 2001. Amiqqaaluta — Let Us Share: Mapping the Road toward a Government for Nunavik. Report of the Nunavik Commission. Ottawa: INAC. Accessed July 24, 2008. https://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/agr/nunavik/ lus_e.html

_ _ _ _ _. 2003. Tlicho Agreement. Ottawa: INAC. Accessed July 24, 2008. https://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/agr/nwts/ tliagr2_e.html

_ _ _ _ _. 2004. James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and

Complementary Agreements. Ottawa: INAC. Accessed July 23, 2008. www.ainc-icnac.gc.ca/pr/agr/que/ jbnq_e.html

_ _ _ _ _. 2006. Annual Reports 2000-2001, 2001-2002, 2002-2003: The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and the Northeastern Quebec Agreement. Ottawa: INAC.

_ _ _ _ _. 2007. General Briefing Note on the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy of Canada and the Status of Claims. Ottawa: INAC. Accessed January 21, 2008. https://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ps/clm/gbn/index_e.html

_ _ _ _ _. 2008a. Agreement Concerning a New Relationship between the Government of Canada and the Cree of Eeyou Istchee. Ottawa: INAC.

_ _ _ _ _. 2008b. “Agreements.” Ottawa: INAC. Accessed July 22, 2008. https://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/agr/index_e.html

Irlbacher-Fox, Stephanie, and Stephen J. Mills. Forthcoming. “Living Up to the Spirit of Modern Treaties? Implementation and Institutional Development.” In The Art of the State Volume IV: Northern Exposure. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Jenson, Jane, and Martin Papillon. 2000. “Challenging the Citizenship Regime: James Bay Cree and Transnational Action.” Politics and Society 28 (2): 245-64.

Kativik Regional Government (KRG). 2003. Annual Report 2001-2002. Kuujjuaq, QC: KRG.

LaRusic, Ignalius. 1979. Negotiating a Way of Life: Initial Cree Experiences with the Administrative Structure Arising from the James Bay Agreement. Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, Policy Research and Evaluation Group.

Linden, Hon. Sidney B. 2007. Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry. 4 vols. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Makivik Corporation. 2003. Annual Report 2002-2003. Kuujjuak, QC: Makivik Corporation.