In 1996, Bill C-63 – providing for the establishment of a National Register of Electors – was passed, thus changing Canada’s method of voter registration from postwrit enumeration to a permanent-list approach. Jerome Black’s analysis of the change in such an integral component of the electoral process has two objectives: to provide a detailed account of the forces and circumstances that led to the transformation of the regime, and to determine whether the new regime has had an effect on voter turnout.

The first objective involves identifying and discussing the factors that led to the changeover. These included increasing concern over problems with enumeration, the desire for shorter election campaigns, the promise of cost savings, the possibility of eliminating duplicate reg- istration efforts between different levels of government, the precedent set in the 1993 election with the reuse of the voters lists compiled for the 1992 referendum and the impact of the Lortie Commission and the auditor general’s recommendations. At the same time, the analy- sis underscores Elections Canada’s role, including that of the chief electoral officer, as a key and proactive element in the process of change. Professor Black argues that the agency capitalized on circumstances favourable to elec- toral reform to advocate a permanent list, stressing its technical and economic feasibility as well as the benefits it could confer, at a time when it was in both the gov- ernment’s and the main opposition parties’ interests to embrace change.

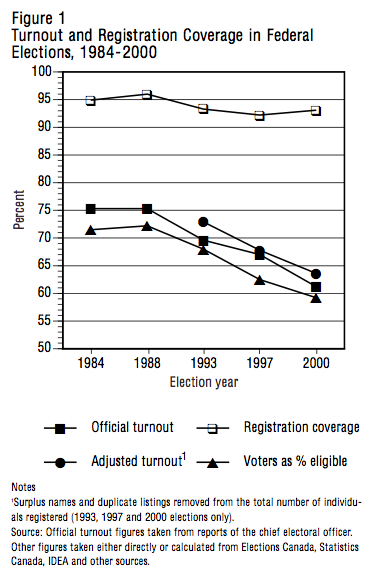

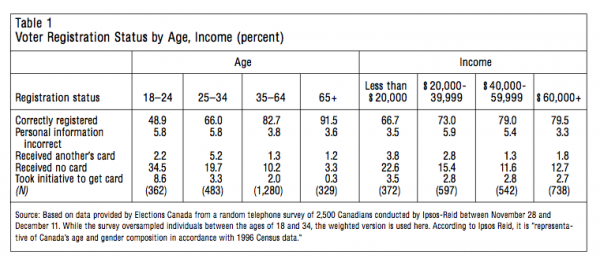

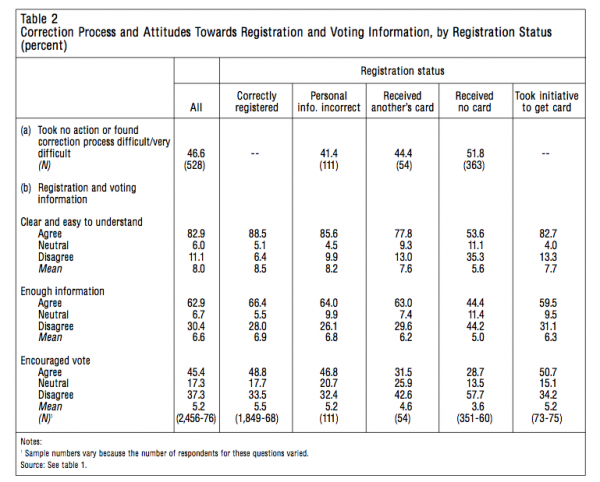

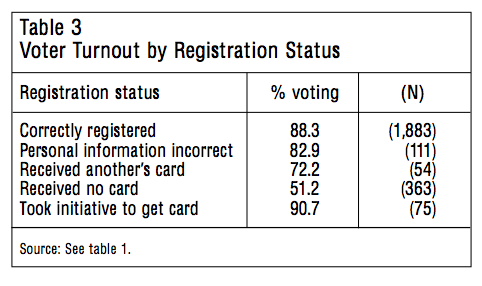

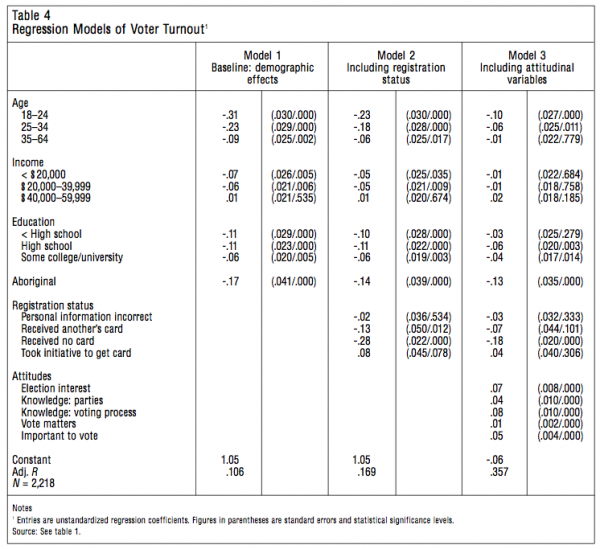

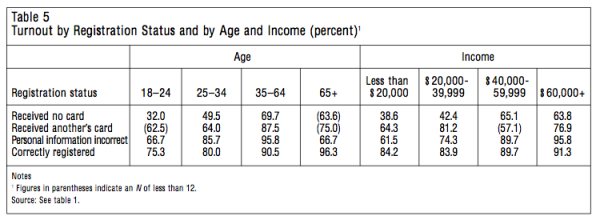

At the time, however, limited attention was given to the impact of the proposed shift on electoral participa- tion. This leads to the second objective of this paper, an examination of the link between the new registration regime and voter turnout. By and large, the analysis indi- cates that the permanent-list approach has contributed to diminishing voter turnout and has accentuated existing participation gaps across social groups. These negative effects are particularly evident in the 2000 election, the first full test of the National Register. Indeed, qualitative and quantitative data converge to demonstrate that a large number of Canadians ended up in less than ideal registration circumstances, which, in turn, decreased the likelihood of their voting. The impact was greater for those who did not receive a voter information card, which thus disproportionately constrained the electoral participation of younger and poorer citizens. The results also suggest that the registration process increased partic- ipation inequality beyond these situational aspects.

In his conclusion, Professor Black notes some steps that are being planned to increase the register’s effective- ness, but adds the recommendation that nation-wide enu- meration be conducted periodically.

When the IRPP published the first paper in the Strengthening Canadian Democracy (SCD) series in September 2000, our open- ing observation was that Canada’s political institu- tions have stood largely unaltered since their creation and might benefit from some critical appraisal. One important exception to this institutional inertia is the method used to register voters for elections. The tra- ditional approach in Canada was door-to-door enu- meration carried out just before an election. In 1997 this approach was abandoned in favour of a perma- nent voters list, formally known as the National Register of Electors. Regularly updated with informa- tion from a variety of government data sources, the permanent list is now used to generate the prelimi- nary list of electors when an election is called, with further adjustments and updates undertaken through- out the campaign period.

If the new registration regime was put in place without much fanfare, it has since become the focus of considerable public attention. Concerns were raised during the 2000 federal election about flaws in the new system that left would-be voters unregistered and uncertain about the necessary remedial measures. Similar concerns were voiced during the 1999 cam- paign in Ontario, which used the National Register to generate the preliminary list of electors for its elec- tion. The province, along with others, now maintains its own permanent list.

These concerns are based largely on anecdotal evi- dence. Jerome H. Black’s contribution in this issue of Choices represents a systematic and rigorous investiga- tion, providing both an account and an evaluation of the switch from enumeration to a permanent voters list.

The account outlines the conditions that created momentum for change and the particular alignment of forces that carried the day. In addition to shedding light on the motivations behind the change in regis- tration regimes, the analysis provides a framework for examining the preconditions for other reforms to Canada’s political institutions, highlighting the sig- nificant hurdles that must be overcome in bringing about institutional overhaul.

In his evaluation of the new approach to voter registration, Black focuses on one fundamental dimension — the impact on electoral participation.

Again, this takes us back to the beginning of the SCD series, Richard Johnston’s lead-off piece (“Canadian Elections at the Millennium,” Choices, 6, no. 6, September 2000), which pointed to declining voter turnout over the past decade as an indicator that all is not well with Canadian politics at the millennium. But whereas Johnston’s analysis focused on the shortcomings of Canada’s party and electoral sys- tems, Black’s focuses on the significance of a new registration system that places a greater burden on voters to ensure that they are properly registered.

Black also enters another distinct area of investi- gation, inequalities in voter participation across demographic groups, focusing in particular on age and income differentials in turnout. Again, this is ter- rain explored in an earlier SCD piece, from a different vantage point. Henry Milner (“Civic Literacy in Comparative Context: Why Canadians Should Be Concerned,” Policy Matters, 2, no 2, July 2001) high- lighted the importance of inequalities in “civic litera- cy” to disparities in political participation. Black’s analysis again draws our attention to administrative barriers: certain groups, already disadvantaged in one way or another, are less likely than others to find themselves on the permanent voters list, and conse- quently face greater hurdles to voting in elections. To what extent does this exacerbate participation inequalities?

The answers Black provides to this and other ques- tions are persuasive and compelling. He draws on his findings to recommend a variety of measures, parallel with the efforts that Elections Canada has been mak- ing to shore up the new system, to ensure that the National Register of Electors functions effectively in the future, particularly in facilitating robust and broad-based voter participation, an important objec- tive for all who hope to see democracy rejuvenated in this country.

André Blais, Université de Montréal

Paul Howe, University of New Brunswick

Richard Johnston, University of British Columbia

As with most processes designed to regulate aspects of political life, the decision to estab- lish a particular voter registration regime entails making significant choices. In one sense, the task can be portrayed as a mechanical endeavour, the need to select from among alternative methods, each of which strikes a different balance between guaran- teeing that qualified citizens have unimpeded access to the vote, on the one hand, and ensuring the integrity of the voting process by guarding against voter fraud, on the other. Registration approaches also differ in their degree of support for certain secondary, but nonetheless important, functions of the electoral system, such as allowing for the mobilization of vot- ers by providing parties with lists of electors. Registration systems also vary along other key dimen- sions, such as operational costs and the quality of the resulting lists. While such considerations are often regarded as establishing appropriate criteria for evalu- ating the performance of different registration regimes, they can also be thought of as objectives that the process might be expected to meet. The selection of a registration method, however, can also be under- stood within a more philosophical context where cen- tral principles and values establish a priority as to the most important purposes that the chosen approach should serve. Characterizing the decision in this way follows from the recognition that in attaching a greater weight to particular objectives, different regis- tration regimes elevate some principles to a higher status than others.1

A key principle underlying Canada’s approach to registration for federal (and most provincial) elections for much of the twentiety century, and around which there seems to have been a strong consensus, was that the state should assume the onus of ensuring that all eligible citizens were listed as electors.2 This belief was manifested in the country’s postwrit or election- specific enumeration approach, through the practice of carrying out a door-to-door canvass that used enumerators who determined and recorded eligible voters. The resulting compilation, carried out once the writs had been issued and used solely for the election at hand, became the preliminary list of elec- tors. Typically, there would be several visitations for those initially missed or not at home, and while at some point the onus shifted to the uncontacted (and thus unlisted) individual to take some minor steps to become registered, the dominant thrust of the approach amounted to a reaching out on the part of the state — literally to the doorsteps of the citizenry. With the state assuming the initiative, the effort required or “costs” incurred by the individual were quite minimal.3 Moreover, in employing a virtual army of enumerators (e.g., about 110,000 enumerators were used for the 1988 election), the massive can- vassing effort was able to capture a very high propor- tion of the eligible population.4 It also served to enhance inclusion, particularly since it drew into the political process the kinds of individuals, such as the young, the poor and those with little formal educa- tion, who otherwise would be less likely to take the initiative to participate.5 This proactive approach, which was the essence of enumeration, worked to augment voter turnout among all segments of society and thus mitigated a natural tendency toward partici- pation inequality in electoral politics.

The fact that registration was undertaken just before an election also served to ensure that currency and accuracy would characterize the registration information compiled. Close sequencing resulted in a reasonably up-to-date list of electors identified at their current addresses and, consequently, preliminary lists that contained a minimum number of errors, either of exclusion (eligible voters not listed) or of inclusion (ineligible voters listed). Thus, enumeration captured those who had changed residence, an impor- tant characteristic in a country with a high mobility rate, as well as new citizens who were constantly entering the electorate along with the newly age- eligible. The timely nature of postwrit enumeration also meant that the false listing of those who had emigrated or passed away was kept to a minimum.

This model, with state initiative at its core, had come to define Canadian tradition, and moreover con- stituted, as Boyer notes, a practice that was unique in the world.6 While he goes on to point out that a major criticism of the approach is its prolongation of the campaign (because of the time requirement of enu- meration), Boyer also states that the “most telling rec- ommendation for it is that approximately 98% of all eligible voters are registered.”7 He also cites, with apparent approval, Ward’s own positive verdict on the approach, including how the Canadian experience has “furnished conclusive evidence that the making of voters’ lists is a proper state function.”8 For his part, Qualter also sees virtue in a system that generates an up-to-date and accurate list of electors, and does so, moreover, “at relatively low cost.”9 Courtney and Smith make the strongest and most carefully con- structed case for the traditional system, highlighting its advantages not only in absolute terms but also rel- ative to alternative approaches. They too emphasize the ability of the enumeration method to reach out to all kinds of individuals:

Enumeration possesses the potential for incor- porating those with special needs into the eligi- ble electorate. These include electors in hospitals and prisons, those with physical and mental dis- abilities, and the homeless, the poor and the illiterate. For such people, a system that depends upon self-registration may well have a repres- sive effect on their willingness or capacity to be included on the list of electors. (p. 433)

They also believe that the personal contact inher- ent in enumeration can be beneficial in and of itself:

A system that places the onus for registration on the state rather than on the citizen and that is coupled with door-to-door enumeration serves as a personal reminder by the community of the pos- itive value that it places on electoral participation by its citizens. The approach of a pending election is heralded through human contact. (p. 433)

While not all academics have embraced enumera- tion as the ideal model,10 the greater emphasis on its merits is certainly part of a broader consensus that has existed about its value as a uniquely Canadian institution.

More to the point, enumeration had long stood the test of official scrutiny and reflection, including eval- uation against other methods of registration. As recently as 1986, a White Paper on Election Law Reform reaffirmed a preference for the traditional system as opposed to either permanent-list forms of registration or annual enumerations.11 Though the white paper identifies some problems with enumera- tion, including the increasing difficulty some return- ing officers were having finding competent enumerators, these were spelled out in the context of recommendations designed to remedy these problem- atic aspects. Moreover, the report lists the main argu- ments typically offered on behalf of alternative approaches. The advantages of a permanent voters list, for example, are cited as being a shortened cam- paign period and the elimination of both the “dupli- cation of effort at the three levels” of government (realizable through computerization) as well as the confusion of voters caught up in overlapping regis- tration efforts. Overall, however, the recommendation to maintain enumeration was forceful and strongly justified. Compared to a permanent-list approach, it was regarded as a less costly method. Moreover, it was argued that a permanent list “would not neces- sarily be more accurate, more complete or more up- to-date than the present enumeration system unless strict controls or compulsory registration were imposed,”12 and would be unacceptable to Canadians concerned about the threat to privacy entailed in the maintenance of permanent records. It seemed, then, that support for Canada’s traditional system of enu- meration was solid.

Ten years later, however, the postwrit enumeration system was abandoned. It was replaced by a perma- nent-list approach based on the compilation and main- tenance of a voters register. Bill C-63,13 which received Royal Assent on December 18, 1996, mandated the implementation of the new system for all electoral events (elections, by-elections and referendums) at the federal level. The National Register (formally, the National Register of Electors) was subsequently estab- lished following a final door-to-door enumeration that was carried out in April 1997, which, in turn, gene- rated the preliminary lists for the ensuing June elec- tion.14 The legislation also reduced the minimum period of an election campaign from 47 to 36 days.15

The National Register itself was established as an “automated database” containing the name, gender, date of birth and address of each Canadian citizen eligible to vote. Given that the standing expectation is for about 20 percent of the listed information to alter each year as a result of address changes (16 per- cent), new 18-year-olds (2 percent), new citizens (1 percent) and deaths (1 percent),16 regular updating of the permanent list is regarded as being imperative. This is done by incorporating new information from federal departments, particularly the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency and Citizenship and Immigration Canada, as well as provincial motor reg- istration and vital statistics agencies. The system is also designed to incorporate voting lists from other jurisdictions. The commitment to maintain the regis- ter in as up-to-date a fashion as possible distinguish- es this approach as an “open” or “continuous” permanent-list form.17 So too does the commitment to provide ample opportunities for unlisted individuals to register during an official revision period and on vot- ing day itself. These latter opportunities are vital because no updating processes can sufficiently track and record the enormous number of demographic and eligibility changes that constantly occur.

What happened? Why was enumeration, given its strong official endorsement as late as 1986, replaced by a permanent list? The question has even greater import considering that the changeover occurred fairly quick- ly, indeed within a remarkably short time frame, given that a major “representational building block,” to use Courtney’s words,18 was at stake. Moreover, the change was part of a 1990s trend that witnessed five provinces adopt their own registers, joining British Columbia, which had (exceptionally) long relied on a permanent list.19 Accounting for the switch in registration regimes at the national level is one of two principal and interre- lated tasks undertaken in this paper. The other is to evaluate the performance of the new system in facili- tating the electoral participation of Canadians.

In examining these two dimensions, this paper fol- lows up on an earlier project20 that provided some ini- tial exploration in both areas. That effort, in fact, identified most of the antecedent factors that appeared relevant for a rudimentary understanding of the changeover in registration regimes. The current contri- bution provides a more systematic account of what happened, and in the process outlines the major devel- opments that unfolded over the period in question. Beyond this descriptive aspect, an emphasis is placed on the role played by Elections Canada and the chief electoral officer in implementing the new system. This portrayal consists mainly in considering what motivat- ed the agency to take the lead in pressing for change and, as well, the kinds of arguments it advanced in order to convince other major actors about both the need for, and the benefits of, such a switch. These aspects are dealt with in Part 1. Part 2 similarly follows up on the earlier study, which had identified the main issues and criteria that are relevant for comparative assessments of the two methods of generating voters lists. In the current study, the emphasis is placed on the implications for voter turnout in Canada, exploring these in connection with participation levels among both the general population and the poorer and less established segments of society (what is characterized as equality of participation). The growing concern over decline in voter turnout and nonvoting in Canada pro- vides an important justification for such a focus. Moreover, one of the key conclusions drawn in Part 1 is that relatively limited attention was given to the pos- sible consequences the changeover might have for the electoral participation of Canadians. This sets up the central question explored in Part 2: whether the alter- ation in registration methods has resulted in reduced voter turnout. The paper closes with a reiteration of the main conclusions, some reflections on their impli- cations and a discussion of issues and possibilities in the development of the new regime.

The preliminary study, designed to frame rele- vant questions for this more extensive work, identified most of the factors that had a bear- ing on the changeover in regimes and, as well, indi- cated that many of them operated in such a way as to reinforce each other’s influence.21 They included increasing concern over difficulties with the enu- meration system and a sense that a permanent list would resolve these, while at the same time deliver- ing the additional advantage of cost savings and a shorter campaign period. Achieving economies was an especially attractive prospect in a climate where- in neoliberal principles, centred on fiscal conser- vatism and a scaling back of government, continued to gain ascendancy. This new environment was also characterized by a concern to reduce duplication of effort and expenditures in the federation, so that the prospect of shared voters lists, and thus even more savings, added to the appeal of a permanent list. A more immediate factor was the close sequencing of the 1992 referendum on the Charlottetown Accord and the 1993 general election. This proximity allowed for the use of the 1992 lists, outside of Quebec at least, in the 1993 election, establishing a precedent for the “reuse” of lists22 and thereby help- ing to legitimize the argument for a permanent list. Also consequential was a 1992 recommendation by the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing (RCERPF, or Lortie Commission) to move toward a register, albeit a provincially based one.233 The 1989 auditor general’s report was addi- tionally identified as having relevance insofar as it motivated Elections Canada to integrate new com- puter technology into its operations, upon which any successful and cost-effective permanent list would ultimately depend. Finally, Elections Canada and Chief Electoral Officer Jean-Pierre Kingsley were characterized as being strongly supportive of the change.

Independently, Courtney has since provided his own brief account of the reasons for the advent of a perma- nent list, but he is more explicit in identifying the near-perfect alignment of pressures and motivations that culminated in the change.24 He does so by drawing upon some fundamental aspects of organizational- innovation theory, particularly the propositions that innovation is most likely to occur when motivation is strong, the obstacles to change are weak and resources are available to overcome any obstacle. Based on information gained from interviews, he writes:

There was at the time (1) strong support from the prime minister (Jean Chrétien) and a convic- tion on the part of important political handlers in the prime minister’s office (such as Jerry Yanover) that change was highly desirable; (2) a notable absence of political opposition to the change in Parliament and indifference on the part of the public and media to the issue; and (3) ample resources to overcome such obstacles as there might have been. Those resources included Elections Canada’s identification of a set of problems with the existing system pack- aged together with a proposed solution to those problems; the Lortie Commission’s qualified endorsement of a move away from door-to-door enumeration; the high priority accorded the leg- islation’s speedy passage by the minister respon- sible for election administration [Herb Gray] and by the cabinet generally; and the attraction that the claims about the cost savings held for the parliamentarians.25

Courtney also points out, and rightly so, that the switch was facilitated by a consensus surrounding a single alternative. The fact that some provinces sup- ported and were interested in future co-operation also served to expedite change.26

In short, both studies understand the alteration in voter registration regimes (and as well the relative quickness of the change) as resulting from a matrix of forces and events that pushed in the same direc- tion; moreover, these converging factors operated without much in the way of counterveiling pressures. Cast at this level, the explanation for the changeover is fairly straightforward and hardly a mysterious affair. Still, as both accounts are quite brief, there is a clear need for more extensive documentation. A chronological analysis helps to meet this need, while also affording an opportunity to specify the essential differences between the two registration approaches and review the kinds of arguments and claims that can be made on behalf of each. A chronological and descriptive narrative also meets the second objective of Part 1, namely to document the key role played by Elections Canada, including the chief electoral officer, in engineering the changeover. To anticipate, it is maintained that the agency and Chief Electoral Officer Kingsley were pivotal in two ways. First of all, they took advantage of opportunities within an evolving political context from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s in which reform of the electoral process was under serious and active consideration. While the developments associated with this period can them- selves be seen as certainly having some relevance for the eventual emergence of a permanent-list system, their impact is largely due to the mediating efforts of Elections Canada. As the agency committed itself to the idea of a register, it gave expression and shape to these background forces and made them more perti- nent and weighty. Elections Canada was also pivotal in a second sense, as they subsequently embarked upon a strategy to demonstrate the technical and economic feasibility of a permanent list in order to sell the idea to elected officials. Moreover, they did so at an opportune time, when both government and the main opposition parties found the arguments for change especially compelling and indeed self-serving.

The idea of a change in the registration regime gained momentum during a period of broad reflection and debate on Canada’s electoral law. Prompted by concerns about the inappropriate and outdated nature of current legislation and practice, especially in light of new Charter-based realities and lags in the use of new technology, a consensus developed around the need to countenance reform in many areas, though not in the electoral system itself. The 1986 white paper and the RCERPF were both products of, and in turn contributed to, this context of questioning and the contemplation of change. At the same time, they differed considerably in the conclusions they drew about replacing the enumeration system. Two other reports, discussed in a moment, also helped define this period, and these too made reference to registra- tion matters.

The white paper’s impact on subsequent develop- ments is probably best understood as being an indirect one. While it did initiate debate on reform in many key areas, in the particular case of voter registration it ended up, as already noted, reaffirming a commitment to enumeration. Still, it did list some of the potential benefits associated with a permanent list and indicated the changes that would be needed to make it a more fea- sible and acceptable alternative. As well, the white paper alluded to the chief difficulty with the enumeration sys- tem, one that had been slowly developing over the years — a shortage of qualified enumerators.27

The chief electoral officer’s 1989 statutory report28 can be similarly identified as having reinforced the general sense as to the need for reform without making any direct contribution to the idea of substituting the enu- meration system. While it acknowledges the shortage of qualified enumerators as a problem by listing the various discretionary measures that returning officers had to take in the 1988 election, at no point does it call the enumeration approach itself into question, and it cer- tainly makes no mention of replacing it. The concern with the need for reform in other areas is, however, very much in evidence. Chapter 2, “The Crisis in Election Administration,” succinctly lists the various issues and pressures that were threatening to overwhelm the agency (pp. 9–12). One of these was the challenge of adopting new computer technology, a task made more difficult by understaffing and outdated legislative arrangements. At the same time, the report indicates that some steps had been taken in the use of computers and office automa- tion, including during the 1988 election.

The auditor general’s report, also issued in 1989, acknowledged these developments but regarded them as insufficient.29 It emphasized that far too much work was still being done manually, particularly with regard to enumeration and revision, and that even in those areas where computers were being employed disparate soft- ware programs were being used. The message, strongly conveyed, was that Elections Canada needed to become more efficient and to seek economies through a greater reliance on information technology and standardized software. The report pushed the case further by noting that computerization could result in additional cost reductions through the development of common proce- dures with other jurisdictions and the sharing of both information and tasks. It also recognized Elections Canada’s difficulty in finding enumerators, though it provided no further commentary in this regard. Still, in urging the agency to embrace fully technology and computerization and, as well, to engage in co-operative endeavours with other jurisdictions, the auditor gener- al’s report may have contributed to the change that eventually occurred. After all, it was generally under- stood that the only way that a permanent-list approach could be rendered sufficiently cost-effective, and thus have a chance of being considered seriously, was through the use of automation to handle the necessary large-scale data collection and data management tasks. As will be discussed below, the report appar- ently served as a catalyst in moving Elections Canada to embrace technological change.

The Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing (RCERPF), without doubt, provided the most extensive commentary and analysis on enu- meration and its possible replacement by a register. Its impact is evident in the way that it added to the general climate for change and, more specifically, enhanced the legitimacy of a permanent-list approach as a serious alternative to enumeration. Indeed, the RCERPF was, in fact, required as part of its mandate to report on “the compiling of voters’ lists, including the advisability of the establishment of a permanent voters’ list.”30 In the end, it proposed moving toward a register-based system. This added considerable momentum to the notion that change was desirable, and certainly the commission’s argu- ments and recommendations were often employed (though at times in a selective fashion) and became frequent points of departure and reference in the dis- course of those supporting a shift.

More particularly, the RCERPF’s main analysis and conclusions on voter registration are spelled out in two chapters of volume 2 of its final report, one dealing with the enumeration system (chapter 1, “The Registration of Voters”), the other with the permanent- list approach (chapter 4, “A Register of Voters”). The significance of the former is the concrete expression it gave to the scale of the decline in the quality of the canvassing effort: “The critical issue that was raised time and again at our public hearings and that has been acknowledged by election administrators, fede- rally and provincially, as an increasingly serious prob- lem over the past two decades, is the number of voters who are missed by enumeration” (p. 7). The issue was regarded as having two main components. One diffi- culty involved the predicament that enumerators faced accessing voters at their residences. This was attributed to occupational and lifestyle changes, such as more women entering the labour force and jobs requiring more travel, all of which meant that fewer individuals were at home when enumerators called. Also noted were problems accessing multiple-unit buildings where policies restrict door-to-door contact of residences. Furthermore, it was argued that in some urban areas “personal safety makes some voters, especially the eld- erly and those who live alone, unwilling to respond to unannounced callers” (p. 9). The Commission acknowledged that while these were not necessarily new con- cerns, they were nonetheless of increasing importance and that “taken together, they make a census-type count of voters more difficult than in the past” (p. 9). Similarly, problems accessing special-needs groups such as the hearing impaired, the illiterate, those who do not speak English or French and immigrants “who may be hesitant to respond to callers representing the state given their experiences in their country of origin” were identified as having “increased substantially in both absolute and relative numbers over the past two decades” (p. 9).

The second difficulty — a more serious one that had been the subject of increasing commentary over the years — was the shortage of competent enumera- tors. Here, too, more women entering the labour force was a factor, since it meant that fewer individuals were available to take up enumeration duties. Personal safety concerns in urban centres “have also taken their toll” (p. 9). Moreover, candidates and political parties, which have the right, in the first instance, to nominate enumerators, had become increasingly unable or unwilling to do so. The supply of enumerators was further constrained by statutory requirements limiting appointment to qualified voters residing in the constituencies.

Importantly, chapter 1 also went on to make rec- ommendations for improving the quality of the enu- meration process by addressing these problems. These included the earlier appointment of enumerators, the appointment of “supervisory enumerators,” the selec- tion of enumerators from all registered constituency associations and from community associations, a lowering of the minimum age to 16 and, in areas where safety was not a concern, the employment of one enumerator instead of two. These measures would no doubt have gone a long way toward resolv- ing the problems identified, and some were put in place for the 1993 election (although enumeration was not required outside of Quebec). Still, judging from comments by the proponents of a register, it was the problems of enumeration, not their recom- mended solutions, that stood out most in this part of the RCERPF’s report.

The chapter on register systems (chapter 4) was even more influential, simply because it did indeed end up recommending that a permanent register be ad- opted for federal elections — although arguing that this would be affordable only if federal authorities were to rely on provincially maintained lists. The particulars of the commission’s advocacy on behalf of a register can be thought of as involving multiple (and overlapping) types of argumentation and commitments. One stressed how it would be possible to ensure that a reg- ister could be guided by some of the principles associ- ated favourably with enumeration. This essentially entailed a commitment to maintain the principle that “registration should primarily be a state responsibility” (p. 113), along with the long-standing orientation to facilitate access to the voting process. Thus, the com- mission saw revision and election-day registration as being integral components of the overall process, in effect establishing the approach as an open-list system offering multiple opportunities for voters to become registered.31 In practical terms, of course, these provi- sions would be necessary to compensate for the expected gaps in the register’s coverage and lack of up-to-date listings of potential voters stemming from eligibility and demographic changes.

Another line of argumentation underscored the distinctive benefits of a permanent list. Principal among these was the advantages of a shorter cam- paign — because canvassing would no longer be nec- essary. This segment of the argument built on a brief section in another chapter (chapter 3, “Administering the Vote”) that began by noting that a shortened campaign was seen as a major advantage of a regis- ter, favoured as it was by most intervenors before the commission (p. 77). Proponents of a shortened cam- paign typically claimed that “Canadians are over- exposed to politics and lose interest as a result” (p. 79), that it would reduce administration costs and that it would make it easier to recruit campaign help. Opposition came from those in large ridings and from small parties with fewer campaign workers.

The case for change also involved the reiteration, often by implication, of the problems with enumera- tion. One point given particular emphasis was that a shared voters list would avoid the confusion of over- lapping enumeration by the different levels of gov- ernment. Maintaining that co-operation with other jurisdictions would bring down the overall costs of registration exemplified another critical line of argu- mentation, namely, addressing the concerns that had in the past surrounded the adoption of a permanent- list approach (such as its greater costs relative to enu- meration). The claim that provincially maintained lists could be employed was regarded as being even more important for the idea that a register could be economically feasible. In this regard, the commission could point to its own research for backing (pp. 125–132). Other research findings, it claimed, indicated that the high quality of the stored registration infor- mation, another long-time concern with a permanent- list approach, could be ensured.

Yet another reservation about permanent lists centred on fears that citizens might have about state intrusion and the loss of privacy. In response, the commission sug- gested that a “high-quality voters register” could be established and maintained without the need to access confidential information in government databases (p. 124), that registration could be kept voluntary, without voters having to relinquish the right to list themselves for a particular election, and that the current legal restrictions limiting the use of lists for electoral purposes could be extended, along with the implementation of appropriate administrative and technical safeguards.

A final line of reasoning involved challenging the idea that what some regarded as distinctive benefits of the enumeration system would not necessarily be lost in the move to a register. In response to the argument that voter interest could decline without personal contact with enumerators as representatives of the state, the commission suggested (but without any supporting evi- dence) that the extensive campaign activity would itself produce sufficient stimulation. In a somewhat similar vein, it asserted that “a shorter election period would not diminish the time available to conduct a campaign at the local level” (p. 123) — candidates and parties would get the preliminary lists of voters earlier since they would be automatically produced from the register.32

While it is clear that the next focal point in the narra- tive is Elections Canada, there are several possible ways of inserting the agency into the analysis relative to this background of significant discussion and the urging of change. One possible interpretation would be to take its subsequent role and specific advocacy of a permanent list as deriving from, and responding to, these develop- ments in the broader environment. Another vantage point, and the one adopted here, attributes more auton- omy and proactivity to the agency and, in fact, places it at the centre of an explanation of the changeover. In essence, it appears that Elections Canada was already motivated to give serious consideration to the idea of a register and, in effect, capitalized on the greater recep- tivity to such a change that was being engendered. This included taking advantage of the contribution that was made by the RCERPF in enhancing the legitimacy of the idea of a new registration method.

Such a perspective finds substantiation, in part, by the demonstration that the causal nexus between the RCERPF’s advocacy of a register and subsequent developments is weaker and much less direct than might be expected. Key to this characterization is the commission’s recommendation of provincially main- tained lists. This was simply a nonstarter for Elections Canada, and, indeed, it is difficult to imagine that the agency would ever take such a suggestion seriously, given that provincial processes and eligibility requirements differ too widely to allow it to meet its obligation for standardization and a national outlook. There is also, of course, the play of ordinary bureau- cratic politics and federal-provincial considerations that suggest that the agency would have been reluc- tant to cede direction of the registration process. Co- operating with the provinces was one thing, yielding control was quite another. A key discussion document that would later emerge from Elections Canada makes this point in plain language:

Elections Canada has a pan-Canadian need for complete, accurate and current electors lists. Federal electoral eligibility requirements provide a common denominator amongst federal, provincial and territorial jurisdictions. Elections Canada is, therefore, well positioned to assume the role of leadership.33

Still, this did not stop the agency from repeatedly dwelling on the commission’s sanctioning of a permanent-list approach as a critical source justifying a switch in registration regimes.

The initiatives that Elections Canada undertook well before the RCERPF tabled its final report (in February 1992) constitute even more persuasive evi- dence that the changeover was only diffusely and tenuously the result of the commission’s work; more to the point, they indicate the agency’s predisposition toward the adoption of a permanent-list approach. In part, these steps suggest a determined response to the growing recognition that Elections Canada needed to exploit new technology, especially computer-based technology. Still, the tight sequencing of these initia- tives and corresponding developments strongly indi- cates that these measures were put into place with the larger goal of developing a list well in mind.

Specifically, by-elections as early as 1990 provided the agency with an opportunity to, in its own words, “test customized software for the computerization of the lists of electors.”34 That experience provided the basis for a March 1991 commitment to use procedures that had already been developed (known as Elections Canada Automated Production of Lists of Electors, or ECAPLE) to produce voters lists on a broader scale. The first opportunity to do so came in October 1992 with the referendum vote on the Charlottetown Accord, in the 220 ridings outside of the province of Quebec (which had opted to supervise the referendum under its own rules). Even if the computerized lists were drawn up in conjunction with an enumeration, this large-scale use of automation was a significant step on the road to a permanent list. More to the point, it was what Elections Canada not only believed but, as well, what it planned for. The goal was to have the finalized 1992 voters list serve as the basis for the preliminary list for the next general election, expected in 1993, thus eliminating the need for another enu- meration. This would allow the agency to claim a rel- evant precedent in moving toward a register, since list reuse is the core principle of such a system. In practi- cal terms, it would allow Elections Canada to point to the acquisition of necessary experience and make more concrete the ways in which the foregoing of a door-to-door canvass would save money.

The forward thinking of the organization in this regard is quite apparent. A specific provision in the 1992 Referendum Act allowed for reuse of the voters list for up to one year following the nationwide con- sultation on the Charlottetown Accord. Moreover, this intent was certainly not disguised by Elections Canada. In his report on the referendum, the chief electoral officer made it quite clear what he had in mind for the future and the importance of computer automation in achieving that objective.

Implementation of the ECAPLE system for the referendum was an investment in the future. The system played a key role in making possible the re-use of the official lists of the referendum as preliminary lists for the 35th general election, as was foreseen in the Referendum Act, and its continued use offers potential for savings in future electoral events at the federal, provincial and municipal levels.35

Kingsley’s report on the 1993 election is even more forthcoming and elaborative of what the larger objective was, and indeed includes a chapter appro- priately titled “Preparing for a Continuous Register of Electors.”36 The preface to this chapter is interesting not only for its summary statement about the com- mitment to a register, but also for the way in which it justifies that commitment, illustrating several of the interpretations discussed above:

In its report of February 1992, the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing recommended that Elections Canada investigate ways of reducing duplicated efforts among election administrators at the federal, provincial/territorial, and municipal levels, espe- cially in the compilation of the voters list. From the number of submissions to the Royal Commission and the number of letters to Elections Canada, it is clear that methods better than door-to-door enumeration must be found to prepare the voters lists. Some form of a con- tinuous register, that is, a voters list that is maintained and updated on a regular basis, seems to be the obvious solution. (p. 130)

As will be seen, Kingsley, in an interview with the author, confirmed an even earlier commitment to a permanent-list approach on the part of Elections Canada.

By itself, the fact that the chief electoral officer was personally strongly in favour of a change in reg- istration methods is no minor detail. Indeed, it appears that if Elections Canada was at the centre of the process of bringing about a switch, Kingsley was its epicentre. His public reports and pronouncements, as well as his comments during the interview,37 pro- vide plenty of evidence of the leading role that he played. This is not to suggest that the idea originated with Kingsley. By his own admission, it was one that had been bandied about within Elections Canada before he took over, and certainly it is fathomable that over the years there would have been much “institutional reflection” on registration matters, increasing as enumeration came under intensifying scrutiny. Rather, what is a simple but nevertheless vital point to understand about Kingsley is that, as the top official, he came to hold a sturdy personal commitment to a permanent list not long after assuming the post in February 1990, and he clearly pushed for its implementation as soon as circum- stances permitted. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine the register coming into force as quickly as it did without his enthusiastic commitment to a new approach and without his guidance in focusing the agency’s efforts in that direction.

The formal record, including Kingsley’s statutory reports on the 1992 referendum and the 1993 election (both issued in January 1994), is replete with sub- stantiating evidence and cannot possibly be read without immediately grasping the strength of the commitment to a register-based approach. A few years later, in April 1996, Kingsley would appear before the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs, welcomed by the chair to discuss “his favourite project, the registry of elections.”38 In October, Herb Gray stood in the House to move that Bill C-63 be referred to that same committee, com- menting that “This bill stems from the report of the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing, the Lortie Commission, and from the rec- ommendations made by the Chief Electoral Officer.”39

In the interview with the author, Kingsley corro- borated the evidence on his central role, and he also helped to shed light on some important details that, in turn, reinforce the perspective that privileges the impact of the agency in the overall scheme of things. Clearly, he had thought about the possibility of a register early on. When he first arrived at Elections Canada, the Lortie Commission was in full swing, but by his own admission Kingsley initially concentrated on the problems assoc- iated with the lack of automation and standardization in drawing up voters lists for the 1988 election. Even before the RCERPF released its report, he had laid the ground- work for the development of ECAPLE for use in the 1992 referendum. At one point in the interview, he allowed that the notion to push for a register had come to him early on but that his staff warned him that “you can’t go too far too fast.” At other times, he talked about how, while he gave particular direction to the development of the register, it was an idea that had been “percolating” for a while in Elections Canada: “A damned good idea whose time had come,” was how he described it. That it was his initiative to reuse the 1992 list is another important marker of Kingsley’s early conviction; indeed, he indi- cated that he would have preferred to see amendments to the Referendum Act permitting the re-employment within two years, not one, presumably to enlarge the window of opportunity for establishing the reuse precedent. Cert- ainly, he was unambiguous in communicating the impor- tance of a consecutive application of the list and of its forming the basis for testing a permanent-list system.

Kingsley’s claims about the primary reasons that drew him early on to the notion of a register are also consistent with other available information about how the process unfolded. He spoke of being motivated by the growing problems with enumeration and, as well, the need, as a general matter, to develop automated and standardized procedures; these were, of course, the kinds of arguments that were being widely made to justify a change in registration approaches. He also identified possible future benefits in areas such as cartography. Interestingly, he did not spontaneously mention cost considerations, which, as will been seen, came to figure prominently in arguments that were being marshalled on behalf of a register. Only when directly asked about their role did he give them some relevance, indicating that as a career civil servant he was always interested in saving money. Still, he did maintain that “Cost is a factor; it is not a driving fac- tor.” He also said he “might have had second thoughts” had the research demonstrated that the new system would cost more.

Two other factors, the idea of sharing data with the provinces and the “benefit” of having a shortened campaign period, were also not offered upfront as having primary relevance. Again, only when specifi- cally probed about each did he indicate that they were “important secondary” considerations. Sharing does save the taxpayer money, he readily acknowl- edged, but it was up to the provinces to use the data. His only elaboration with regard to campaign length was to suggest, interestingly enough, that the Lortie Commission was mistaken in concluding that a 40- day campaign is possible even with enumeration; only a register, Kingsley maintained, can reduce the period to under 47 days.

His broader comments on the RCERPF reinforce the argument made above about its lesser or its more indi- rect impact on the emergence of the register. Kingsley even went so far as to assert, in rather blunt language, that the RCERPF’s support for a provincially based approach had a negative impact on the movement toward a register: “It hindered the work of Elections Canada because it created for some provincial electoral bodies a form of tacit recognition of their centrality; some saw it as being in their hands.” In fact, if the interview provided a sense that any report deserves to be singled out for having influenced his thinking and developments within Elections Canada, it was the auditor general’s report, which had sharply criticized the agency’s sluggishness in embracing new techno- logy. This jolt to the agency appears to have engen- dered a commitment to catch up technologically and indeed, judging from Kingsley’s demeanour and actions, to go much further than that.

This point merits emphasis and helps make a larger argument that the eagerness for the project was part of a broader vision, no doubt shared by Kingsley and others in Elections Canada, that the agency needed to embrace technological change and innovation unre- servedly. The development of a computerized list was only one way that Elections Canada could position itself in the forefront with regard to the use of the most sophisticated technology available; other areas included digital mapping, voting by telephone, elec- tronic voting (or “smart cards”) and voting machines (including touch-screen equipment) in ballot booths.40 A computerized voters list would fit well with and indeed facilitate these innovations. In short, it is prob- ably fair to say that a “culture of technology” gripped Elections Canada and that the exploitation of informa- tion technology became an operating and self-evident norm. This outlook represented a conscious break with the past and with an orientation that had been criti- cized in the auditor general’s report; by adopting the very latest in automation and other technology, the agency would be heeding the imperative to “modern- ize,” a word that Kingsley repeatedly used as he endeavoured to promote the switchover.41

Beyond establishing ECAPLE, Kingsley and the agency took other concrete steps that reveal an eagerness to move expeditiously toward instituting a register. A steering committee was struck on October 20, 1993, with a mandate to “act as a coordinating body, within Elections Canada, with respect to com- municating and encouraging the development of A Continuous Register of Electors.”42 By the spring of 1994, the in-house “Discussion Paper on a Continuous Register of Electors” was produced, intended to provide a “high level overview of the con- cept of the Register.”43 The document provides back- ground commentary about registers, including the experiences of other countries, but the bulk of the treatment and its overall tone make it quite clear that what was at issue was not whether a register would be established but rather the timing and the modali- ties of how it might be brought to fruition.44 No con- sideration whatsoever was given to the possibility of retaining enumeration and handling its shortcomings through remedial measures; instead, the emphasis was squarely on the need for change. To this end, there was the by now familiar litany of complaints surrounding enumeration and the advantages and opportunities that a register could confer.

Other important themes further reveal the goal- oriented nature of the document. One chapter, for instance, dealt with design considerations and some administrative and technical matters that would need to be taken into account in establishing a register (e.g., how the register might be structured, data qua- lity considerations and the like). Perhaps most impor- tant of all was the chapter “Strategic Avenues,” which dealt with the issues and obstacles, including political ones, that needed to be addressed. One sec- tion, headed “Political Will,” pointed out that “politi- cians need to be educated about the current problems and potential solutions in a cross-jurisdictional per- spective” (p. 28). The document concluded, confi- dently, that “key arguments support the initiation of a process that will lead to the creation of a shared Register of Electors” (p. 33).

The next step involved the steering committee set- ting up a special project team, in late 1994 or early 1995,45 charged with examining “the costs and bene- its of a register, extensive work on new processes and procedures, evaluation of sources for updating data, consultation with potential partners, and feasibility assessment.”46 One year later, in December 1995, suffi- cient work had been done to allow the chief electoral officer to present the team’s main findings to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs at an in camera meeting.

The project team’s report, The Register of Electors Project: A Report on Research and Feasibility, began circulating in the spring of 1996. It declared unequiv- ocally that study and analysis had shown that a national register was “both feasible and cost effective” (p. 5). Other assertions were set forth as additional “main conclusions.” A few of these reiterated familiar themes such as how the register would allow a reduc- tion in the election period from 47 to 36 days. Another identified the most appropriate existing sources for keeping the register up-to-date and argued that a “targeted reliability level of 80%” for the regis- ter could be maintained, meaning that the derived preliminary list would have the correct addresses for an estimated 80 percent of eligible voters. This figure was judged as “the level necessary to conduct an elec- toral event” (p. 5). The report also confirmed current support and future interest by other electoral agencies for a shared national register and as well dealt with the kinds of legislative changes that would be required for its creation. Finally, a key conclusion highlighted fiscal savings. While the implementation of a register at the next election would cost about the same as car- rying out an election under enumeration (in large measure because a final enumeration would be neces- sary), each subsequent contest would allow for sav- ings (a “cost avoidance”) of $40 million, and even more as other jurisdictions joined in (p. 6).47

Beyond these specifics, the report’s general tone reflected what had by then developed into the set strategy for selling the register, and one rooted in the logic employed by the Lortie Commission, namely, taking the problems and limitations of the enumera- tion approach as a point of departure, demonstrating how a permanent-list system would both ameliorate those difficulties and provide further benefits, and finally, pointing out how traditional concerns atten- dant with a permanent-list method could be sur- mounted. The latter included the argument that the voters list could indeed be effectively maintained and kept up-to-date. It was even pointed out that “elec- toral information would be of higher quality, because preliminary lists of electors would be produced over time and not in the tight time frames currently required during an electoral event” (p. 17).

The report also addressed the long-standing concern over invasion of privacy and confidentiality of the information that electors provided, and in several ways. First of all, it proclaimed privacy and confidentiality as core standards that had helped guide the research; this was part of the commitment to ensure that the register would preserve “certain principles and characteristics of the Canadian electoral system.” There were also indica- tions that the project team had reviewed the treatment of privacy concerns in other jurisdictions, and there were references to how there had been continuous con- sultations with the federal Privacy Commissioner’s Office (p. 21); indeed, there was an acknowledgement that a “privacy advisor” from the office had participat- ed in many of the workshops (p. 7).

However one might characterize Elections Canada’s packaging of arguments and background research to make a case for a register, it is abundantly clear that the government bought the package. Its support of an altered registration process and abbreviated campaign period is indicated most obviously by the legislative priority it attached to the changeover. On October 21, 1996, a little over half a year after the release of The Register of Electors Project, Bill C-63 was given first reading. The legislation moved fairly quickly through the House, receiving a third reading on November 26. The government’s firm support of the initiative is fur- ther evident in the selection of Herb Gray, who was House leader and solicitor general, to shepherd the bill through the chamber. Courtney similarly notes (in pass- ing) this turn of events as being reflective of the gov- ernment’s determined backing and, importantly, adds that his interviews suggested firm specific support from Jean Chrétien and the Prime Minister’s Office. Political support was apparent not only from within the execu- tive, however. It was also forthcoming from legislators as a whole. Indeed, the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs had signalled its approval even before the formal release of the The Register of Electors Project report, when members were briefed by Kingsley in December 1995. While that session, it will be recalled, was held behind closed doors, the minutes of subsequent meetings dealing with the draft legisla- tion make it clear that there had been widespread endorsement for the register at that earlier gathering. Moreover, in the report itself the committee was char- acterized as having “concurred in the value of moving to a register system, enthusiastically supported the approach proposed for its implementation, and agreed that Elections Canada should immediately pre- pare a report in the form of draft legislation to begin to develop the administrative mechanisms and sys- tems needed to use a register in the fall of 1997.”49

What is the basis of this political support? Why was the changeover given such an easy political ride? Courtney does not elaborate on what, specifically, may have motivated Chrétien, his ministers and his political advisers to embrace the change, but presum- ably they accepted the long-standing argument that a permanent list would resolve old problems and bring new benefits — among which the prospect of curbing expenditures would have had special appeal. While the costs associated with running the registration sys- tem had always been one of the criteria for evaluat- ing the relative merits of different approaches, registration economics came to play an even larger role as neoliberal principles became more widespread and entrenched during this period and as the Chrétien government became convinced of the need to reduce the state’s financial burden. In short, as the costs of the registration system came to be evaluated within a climate of economic restraint, the notion that a per- manent voters list could save governments and tax- payers money would have generated a positive response in many quarters.

Federal-provincial politics were no doubt also a consideration. At one level, the fact that some provinces had signalled their interest in co-operating with Ottawa enhanced the prospect of the federal government using provincial sources to update the register and cut overall costs through shared voters lists. Another amenable development, alluded to ear- lier, was the adoption at that time of permanent lists by a growing number of provinces. On a more politi- cal level, however, Ottawa’s ability to point to provincial interest and possible involvement, in an era when cross-jurisdictional conflict was more com- mon than not, provided it with a focal point for federal-provincial co-operation and success. It also served to illustrate that concrete steps were being taken to end overlap and duplication of effort on the part of the different governments,50 a fixation that had been intensifying as part of a general process of “rethinking government” designed to render its oper- ations more efficient and cost-effective.51 Thus federal-provincial co-operation meshed with savings as significant explanatory factors driving support for the register.52

The appeal of a reduced campaign period must have also been politically attractive to key politicians and their advisers. While most proponents of a shorter campaign touted its virtues by making the specific argument that administrative costs would be curbed or by offering the more diffuse notion that Canadians would be spared the tedium of an overly long contest, behind the scenes it may well have been understood that a condensed campaign would serve the re-election interests of an incumbent government — especially one that commanded a substantial lead in public opinion polls and that faced a sharply divided opposition. Even in the absence of hard evi- dence for a direct link between campaign length and incumbency success,53 the government likely realized that any lead it held would be harder to overcome in a compressed campaign period.54

The main opposition parties were no doubt also aware of this Liberal advantage, though they merely alluded to it in the House.55 With the Liberals still leading in the polls and an election imminent, the worry was that hasty implementation would indeed give the governing party an advantage.56 This is the chief reason why the opposition parties ultimately voted against the legislation. Indeed, the government used time allocation to end debate and expedite pas- sage, ignoring opposition protests that there had been insufficient consultation and that there was no “real reason” to rush the process. There were also the obligatory and predictable add-on complaints, such as that the bill did not go far enough in the context of what were regarded as other areas in need of con- sideration. The Reform Party wanted additional delib- eration on the subject of having fixed elections and the establishment of recall procedures, and also urged debate on removing the subsidies and tax conces- sions to political parties.57

From the other direction, the Bloc Québécois pushed for a stricter election finance regime, specifi- cally one that mimicked Quebec’s more regulated approach. That said, the opposition protest was driven mostly by the timing of the process and its hurried implementation of the new registration approach. As has already been pointed out, the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs as a whole had been supportive of the idea of change from the very outset, and throughout the legislative proceedings the two main opposition parties contin- ued to signal their fundamental agreement with the principles of establishing a permanent list and a shorter campaign.58 Reform MPs on the committee and in the House were openly enthusiastic about the possible cost reductions that would be realized from the changeover (and, to a lesser extent, content that a source of minor patronage would be removed for the dominant Liberals), while, for its part, the Bloc con- tinued to take its lead from developments in Quebec, where the provincial government was in the process of establishing its own voters register. Mention might be made as well that opposition members, as incum- bent politicians contemplating their own personal re- election campaigns, likely also regarded a shorter campaign as an attractive feature.

In short, the fact that Reform and the Bloc ulti- mately voted against Bill C-63 does not contradict the essential portrayal that the major political forces were lined up on the same side. Moreover, in retrospect, given their political outlooks, it is not at all surprising that there was support for the permanent list on the benches opposite the government. This is, of course, one of the implications of what was the most promi- nent feature of the political era, the collapse of the tra- ditional party system, characterized by devastating losses by the New Democratic Party and, especially, the Progressive Conservative Party, and their replacement by Reform and the Bloc. The two older parties were virtually invisible in the debate, as they were in Parliament generally, and, of course, lacking status as “recognized parties,” had no representation on the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs.

The executive, the Liberal Party and the two main opposition parties were clearly neither invisible nor irrelevant as part of the defining political environ- ment that ultimately produced the National Register. Obviously, their support, and particularly the backing by the government, were essential ingredients, and it is significant that these forces were all arrayed on the same side as the process unfolded. However, their impact, even if convergent in nature, was subsequent to the initiative demonstrated by Elections Canada and the engineering efforts that agency made to develop and sell the case for change. The early steps that Elections Canada took, already documented, are especially relevant for appreciating its prior impact with reference to these political forces. Reinforcing this interpretation of causal sequencing is the virtual absence of any evidence suggesting that these politi- cal actors, all of whom fared well in the 1993 elec- tion, had signalled any pre-existing preferences for a change in the registration system. Especially impor- tant in this regard is the lack of any mention of reg- istration reform in the Liberals’ famous “Red Book,” which set out campaign pledges in numerous areas.59 Another timing-sensitive point is apparent when one recalls that the agency established its all-important steering committee with the mandate, again, “to act as a coordinating body, within Elections Canada, with respect to communicating and encouraging the devel- opment of A Continuous Register of Electors” on October 20, 1993, that is, even before the 1993 election campaign had drawn to a close.

In sum, the argument here is that both government and opposition responded positively to Elections Canada’s initiative because the change was politically and economically favourable and because it was in the interests, both partisan and otherwise, of the main par- ties to go along. No doubt, much of what was pitched to the elected officials and their advisers by Elections Canada reflected its appreciation of which arguments, explicitly made or perhaps merely implied, would be most effective. In this sense, the organization not only capitalized on amenable circumstances as it took up the cause of a register, but actively championed it as well.

John Courtney makes the simple, though important, point that the process of change became easier in the absence of debate on what might replace enumeration. Consensus among those seeking change that the only acceptable alternative was some form of “open” perma- nent list no doubt helped concentrate opposition to enumeration in favour of a register. A broader take on Courtney’s observation might be that this consensus effectively ended up precluding the option of reforming enumeration. As it was, the reflection and discussion that surrounded registration reform tended to be nar- rowly focused. A more encompassing consideration might have done more to stress the relative strengths of enumeration and to include an analysis of the possibil- ity of reforming the canvassing-based process to meet what were regarded as its limitations. Such a stance would not have been completely at odds with the con- clusions of the Lortie Commission, which did, of course, offer important recommendations for improving the enumeration system, even as it favoured the move to a (provincially based) register.

However, the weight of the recommendations was undermined not only by the RCERPF’s advocacy of a permanent list, but also by the limited analysis that it had conducted as it drew critical conclusions about the functioning of the enumeration method. This is the case that Courtney and Smith make in their RCERPF- sponsored background publication.60 While admitting that the shortage of qualified enumerators had been a problem, they state that it was not a particularly new difficulty, that there was no hard evidence that it had increased in magnitude and that it was in any event a circumscribed matter involving some, but hardly all, urban polls. Courtney and Smith also wonder if enu- meration problems, especially overlooked voters, could indeed all be linked to the failure to find suffi- ciently qualified enumerators. Importantly, they point out that 85 percent of the returning officers were new in 1988 and that their inexperience could easily have resulted in the inadequate training of enumerators. In addition, they observe that the pressure to begin the campaign quickly was “another practical constraint on efficiency that is quite separate from the quality of personnel” (p. 363). They also list other factors, such as inadequate pay, as explanations for the short- fall in qualified enumerators.

Courtney and Smith also raise questions about the evidence justifying a move toward a shorter cam- paign. While the commission was no doubt impressed by the large number of interveners who identified a shorter campaign as one advantage of a permanent list, it is unclear whether this sentiment spread much beyond the context of its proceedings. The two authors admit that although there had been some concern about campaign length in the recent past (and that presumably this is what led to the reduction from 60 to 50 days), their sense of the matter is that it continued to be a fairly minor preoccupation. After reviewing statutory reports, newspaper commentaries and Elections Canada’s publication Contact, they con- clude: “In a list of problems and shortcomings of Canada’s voter registration system, the length of the campaign to which enumeration contributes, must be ranked low” (p. 371).

It would appear, then, that the RCERPF’s limited research into the problems of enumeration is one of the specific ways in which the commission con- tributed to the ascendancy of the permanent-list idea, which Elections Canada benefited from as it began to sponsor a federally controlled permanent list. The absence of a comprehensive assessment, one that included research-based solutions to the problems of enumeration, made it easier for the agency to take those difficulties (and the supposed benefits of a shorter campaign) as its launching point. It then had only to demonstrate that the substitution of a perma- nent list would resolve those problems. Of course, the fact that the agency’s research agenda did not itself include any analysis of a revamped enumeration process is even more indicative of a very early prefer- ence for a complete overhaul. Note as well that Elections Canada’s general strategy of selling the idea of a register served the same purpose — to keep all other options off the table.

Elections Canada’s research agenda was, unfortunately, also circumscribed in another important way: relative- ly little concrete consideration was given to the impact of a permanent-list approach on electoral participa- tion, including equality of participation. To be sure, there was a formal commitment to the idea that any new system would need to work to facilitate the vote. Indeed, appearing before the Senate as it considered Bill C-63, Kingsley articulated six principles that had guided thinking about the development and mainte- nance of the register, pointing out that the RCERPF’s own deliberations had been framed in these same prin- ciples. The first three centred on the need to ensure that the state would continue to assume primary responsibility for registration, that potential voters would be given postwrit opportunities to register and that the new system would function as effectively as the enumeration system — meaning that levels of cov- erage and accuracy would be equivalent to those achieved through enumeration. The remaining guide- lines centred on concerns about privacy, confidentiali- ty and the right not to participate in the process.61

These principles are comparable, though not iden- tical, to the orienting standards that were spelled out in The Register of Electors Project.62 The first three of these similarly identified state initiative and voter access as guiding principles. The fourth pledged to respect electors’ privacy and the confidentiality of their personal information. A fifth posited the need to locate reliable data sources, in order both to minimize the costs of developing and maintaining the register and to avoid “any further imposition on Canadians in gathering personal information.” Finally, there was a commitment to investigate the matter of sharing the register’s data with other jurisdictions.

The main point is that nowhere in that key report was there any note of concern about the possible neg- ative effects on voter participation that might ensue from the implementation of a permanent list. Short of a population register that would serve as the basis for a voters register or a system of mandatory registration, neither of which was seriously considered (and under- standably so), the permanent-list method as envisaged could never match the effectiveness of the state- initiated enumeration approach in facilitating registis- tration. It is true, of course, that once they are inscribed in the National Register, voting would be a relatively easy matter for the overwhelming majority of Canadians who do not move between electoral events. Nevertheless, for the many who do change addresses, particularly if they move out of their origi- nal constituency (see below), some action would be required to correct their registration information. The newly eligible, especially those turning 18, would need to do even more to register in the first instance. Without denying that with the new regime in place Elections Canada has made it as easy as possible for individuals to become properly registered, and as well granting that, from an objective perspective, the amount of effort required to do so is quite minimal, the reality nevertheless remains that individuals still need to exercise some initiative. And, again, every- thing that is known about the facilitation and inhibi- tion of participation would anticipate a drop in participation as these demands, modest as they may be, are placed on the prospective voter. Given the cir- cumstances and the demographics involved, the nega- tive effect is likely to be accentuated among those who frequently move, such as renters and poorer persons, as well as among those entering the electorate. Many such individuals are already less prone to vote, which is why there have long been disparities in turnout across social categories. A registration regime that demands some action on the part of such individuals may very well run the risk of creating even larger gaps. Unfortunately, such concerns about diminished participation and participation equality, arguably the main disadvantages associated with the new system, were largely ignored in the extensive research and dis- cussion that framed the understanding and arguments about the impact of a regime change.63