A decade ago, even with the Canadian economy firing on most cylinders, there were mounting concerns over labour shortages.1 Subsequently, the 2009 recession dimmed labour demand, but warning cries of shortages have since resurfaced with the economic recovery. Yet to even a close observer, the extent and nature of any labour shortage in Canada must seem perplexing. In good part, this is because of long-standing inadequacies in Canada’s labour market information (LMI).

In response to growing controversies over labour shortages, in 2008 the Forum of Labour Market Ministers (FLMM), representing Ottawa, the provinces and territories, created the Advisory Panel on Labour Market Information.2 The panel reported in May 2009 with 69 recommendations for improving LMI. To implement the suggestions would have a recurring annual cost of only $49 million (2009 dollars).3

For his part, federal Employment Minister Jason Kenney says that two-thirds of the recommendations have been or are being implemented.4 That sounds promising. But it begs the question of why there is still so much disagreement over labour market conditions. The situation calls for an update on the state of LMI in Canada – and a second cry for improvement.

More than 10 years ago, the Conference Board of Canada released a seminal report on labour shortages.5 It claimed there would be a shortfall of one million workers by 2020. At the end of the report, it noted some caveats, such as a warning that a persistent shortage would trigger higher wages, which in turn would lead to higher labour supply that would eventually restore the labour market to balance. But the caveats were not given much prominence and were largely ignored.

Interestingly, the Conference Board’s director of forecasting and analysis, Pedro Antunes, says that while researchers and the media have often quoted the “million worker shortfall,” the number has largely been misunderstood. Antunes adds, “In that same report, we explained that a worker shortfall is ”˜logically impossible’ and that something else has to give.”6

More recently, former Seneca College president Rick Miner in 2010 released another high-profile labour market report.7 Miner, a member of the FLMM Advisory Panel, projected that Canada would face a shortage of 4.2 million skilled workers by 2031. But just four years after issuing his report, Miner demonstrated the fluidity of such extrapolations. In March 2014, he updated his analysis to factor in recent developments such as an increase in the labour force participation rate among older workers. The projected shortage was cut from 4.2 million to 2.3 million, a 45 percent reduction.8 The latter figure is, of course, very high. But such a large change in four years to a forecast for conditions two decades out highlights the inherent uncertainty of such an exercise because, as the Conference Board noted in its original report, the labour market has many moving parts.

All the major Canadian business associations are championing the cause of -addressing labour market shortages. As just one example, the Chamber of Commerce in 2013 estimated that there would be 1.5 million vacancies for skilled jobs by 2016, but, at the same time, it said 550,000 unskilled workers would not be able to find work.9

These concerns have clearly attracted political attention. Speaking to a -Canada-US business audience in November 2012, Prime Minister Stephen Harper declared, “[The labour shortage] is in my judgment the biggest challenge our country faces.”10 But, as in most things economic, there is by no means a consensus on this issue. Several recent reports maintain that there is not now, nor will there likely be in future, a general, pan-Canadian labour shortage, of skilled or unskilled workers. Examples of this argument can be found in reports by the Parliamentary Budget Officer,11 by labour market economist and former Employment and Social Development Canada senior official Cliff Halliwell12 and by the TD Bank.13 All argue that any shortages, rather than being generalized, are concentrated in specific regions and occupations.

This more nuanced approach to labour shortages is gaining some traction. For example, the March 2014 Council of Chief Executives report summarizing results from its most recent member survey on skills and labour market issues begins with the following assertion: “The survey results do not support the argument that Canada is suffering from a comprehensive, national skills shortage. Rather, they suggest that shortages are limited to certain regions, sectors and occupations in Canada – a conclusion consistent with the findings of recent reports by TD Economics and the Conference Board of Canada.”14

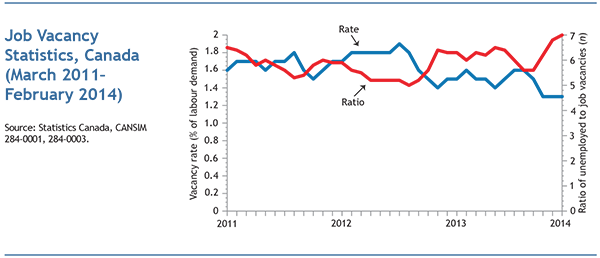

Lest the observer think some clarity is emerging concerning the labour market, I now turn to a more recent job vacancy controversy. One of the earliest responses to the FLMM Advisory Panel’s recommendations was Statistics Canada’s establishment of a monthly job vacancy survey.15 Its latest report (for the three-month average ending in February 2014) indicated a job vacancy rate of 1.3 percent. Put another way, for every vacant job, the survey suggested, there were seven unemployed people. As shown in the figure, both results have been fairly stable over the last three years. And both indicators suggest overwhelmingly that the principal Canadian labour market problem is insufficient aggregate demand rather than a shortage of workers.

However, the survey does point to regional and occupational variations. For example, in Alberta and Saskatchewan there were respectively only 2.3 and 3.3 unemployed workers for each job vacancy. If we look at surveys over the 12 months from March 2013 and February 2014, we see tight labour market conditions for some sectors, including health care and social assistance; professional, scientific and technical services; and information and cultural industries.

At the other extreme, the data show particularly weak labour demand for construction,16 manufacturing and educational services. So the Statistics Canada survey does suggest there are some significant geographical and occupational labour mismatches.

Clearly, to repeat a familiar refrain, the picture on job vacancies is clouded. Even the federal government has muddied the waters. In the 2013 and 2014 federal budgets, the finance department published its own estimate of job vacancies, supplementing the Statistics Canada data with private sector sources in a manner that has never been fully explained. The budgets suggested a job vacancy rate of around 4 percent, compared with Statistics Canada’s estimate of only one-third that magnitude.17 The difference is truly a game changer. Statistics Canada’s result does not point to a labour shortage and points to fairly limited mismatching. The budget result suggests there is a large skills mismatch problem, with the logical inference that there is a looming aggregate labour shortage.

Ottawa’s budget methodology has recently been criticized for including jobs posted on Kijiji. Critics have suggested, among other things, that this introduces the possibility of double counting.18 But while it has been reported in the media that the recent budget estimates have, as a result, been discredited, it seems unlikely that double counting through Kijiji could account for all of the difference between the Statistics Canada and budget estimates of the job vacancy rate. So confusion will likely remain the order of the day.

Related to the theme of labour shortages and mismatches are widespread claims that we have an oversupply of university graduates with impractical general degrees and not enough graduates in skilled trades and other areas currently in high demand, such as certain fields of engineering and information and communications technology.

Statistics Canada’s National Graduates Survey is an important source of information on how college and university graduates are faring in the workplace. The survey is conducted only every five years, so the latest information available is on how 2005 graduates did in 2007. Due to the infrequency but importance of these data, the survey of 2010 graduates is anxiously awaited. But it seems the wait will go on for a while longer, and even when it is released, there might not be clarity.

On March 31, 2014, Statistics Canada simply announced that the data from the 2010 National Graduates Survey are available for “custom request.” It seems the normal public data tape is not going to be released, and it will likely be only at the end of 2014 that Statistics Canada provides an analytical report. Meanwhile, we will have to see whether a researcher can make sense of the raw data and provide a report that finds its way into the public domain.

It does appear that some of the findings are seeing the light of day. Alex Usher of Higher Education Strategy Associates said on April 7 this year that he had obtained some basic results that show the employment and income outcomes of 2010 university and college graduates were favourable and undiminished from the 2005 survey findings.19 However, Usher retracted these conclusions two days later, citing discomfort with how Statistics Canada adjusted the 2010 survey results to account for the fact that the survey addressed outcomes three years after graduation, while all previous editions had looked only two years out.20 So, more confusion.

The uncertainty is not restricted to employment and unemployment flows. Since Ottawa announced the Canada Job Grant initiative in the 2013 budget, there has been an intense debate over job training in Canada. A common assertion, and indeed the premise behind the Canada Job Grant initiative, is that employers do not provide enough training. Yet we have little reliable information on how much training they do provide. And we have even less on the nature of that training and the results it yields for the company, the employees and the economy at large.

Indeed, little has been known about such matters since Statistics Canada cancelled its annual Workplace and Employee Survey (WES) in 2006. Gone also is needed information on work conditions such as the use of flexible time and time off for family responsibilities like child care and elder care. The FLMM Advisory Panel recommended that something similar to the WES be reinstated; this has not been done.

The World Economic Forum is one of many authoritative voices emphasizing the importance of matching skills with labour market needs. To quote its January 2014 report:

For individuals, overskilling or overqualification means unrealized expectations, lower returns on investment in education, lower wages and lower job satisfaction. For firms, it actually may reduce productivity and can increase the staff turnover rate. At the macroeconomic level, this contributes to structural unemployment and reduces growth in gross domestic product (GDP) through workforce underutilization and a reduction in productivity. But in addition to efficiency losses, these mismatches entail significant equity costs, as young people, migrants and those working in part-time and fixed-term jobs are more affected by skills mismatch.21

Good LMI is not a sufficient condition for effective matching of skills and labour market needs. But it is clearly a necessary condition. Good matching cannot occur if the agents – individuals, businesses, educational institutions and governments – do not have a clear idea of what skills are required.

Of course, these agents still have to react to the information. And there may be other impediments to that. But to a considerable extent, the agents will instinctively respond appropriately if they have the right information. For example, students will gravitate toward areas that offer prospects of good jobs. The unemployed and those looking for a job change will latch onto the job vacancies identified and will better address any skill deficiencies once they know the job requirements.

For their part, companies will adjust their recruitment and training patterns once they understand the nature of labour market mismatches. Colleges, universities and other educational institutions will shift their programs and training toward areas where graduates are in demand. At each step there may be obstacles, but governments with good information can better assess the types of policy interventions required to ensure that the matching of skills to labour market needs is effective and efficient.

The FLMM Advisory Panel argued that better evidence would lower unemployment rates in good and bad economic times.22 Indeed, the economic potential of lowering unemployment is tremendous. The panel calculated that lowering the unemployment rate by just one-tenth of a percentage point would add $800 million to Canada’s GDP. With Canadian governments spending approximately $100 million a year on LMI (as of 2009),23 the price is modest, even if one adds to it the approximately $49 million a year needed to implement all the panel’s recommendations.

While reports on labour market conditions, particularly those on labour shortages and mismatches, have become in some respects more sophisticated and nuanced in recent years, the field is still rife with confusion. One might well ask how this is possible in light of the FLMM Advisory Panel report and -Kenney’s assertion that two-thirds of the recommendations have been or are in the process of being implemented.

One possible answer is that the advisory panel’s recommendations, even if they had all been implemented, would not have provided greater clarity on labour market conditions. No doubt they would not have made everything clear, as labour markets are very complex, ever changing and highly heterogeneous by occupation and location. And no doubt I may harbour biases, having chaired the panel. But it seems safe to say that even if the recommendations fell short of perfection, their implementation should have greatly illuminated the situation. Yet that hasn’t happened. What, then, has gone wrong?

Having two-thirds of the recommendations implemented or under way is encouraging and gratifying. Clearly, all governments take the issue seriously. However, one must note that many more recommendations fall into the “being implemented” category than the “have been implemented” category. Furthermore, many of the in-process recommendations are at the bureaucratic background stage, so they have not produced any tangible benefits. And, finally, some of the most critical recommendations have not yet been satisfactorily implemented.

Not all of the panel’s 69 recommendations carry the same weight, so I will not review them all here. Instead, I will review only those believed to have the greatest payoff.

The recommendations that stand out from all the others are the first two, calling for the FLMM to take charge of labour market information and for Statistics Canada to fill in the information gaps. The panel found that the lack of an accountable body to make a cohesive, coordinated plan for the identification, collection, dissemination and communication of information was the main source of confusion.

In 2008, when the panel was established, some disarray was understandable. Ottawa had just devolved many of the responsibilities for designing and delivering employment supports to the provinces and territories. Unfortunately, there does not appear to have been any discussion of what would happen to the supporting LMI. To a large degree, that had been the responsibility of Human Resources and Social Development Canada (HRSDC, now Employment and Social Development Canada). But with fewer responsibilities in this area, HRSDC naturally withdrew to some extent from the information field. Many of the provinces tried to fill the gap, but from their provincial perspectives -rather- than a national one. To some degree, the shifting of policy responsibilities inadvertently weakened an already flawed national LMI system.

It is important to note that Statistics Canada never had the full array of responsibilities for LMI. Furthermore, there was not ongoing funding for much of what they did do. Consequently, the agency had to appeal to others, particularly HRSDC, for ad hoc funds. Statistics Canada already had serious budget constraints by 2008 and subsequently underwent several rounds of further funding cuts, making it difficult to maintain even its partial coverage of LMI, never mind step into a larger role. And as HRSDC and other federal departments began to face their own budget constraints, it became more difficult to obtain additional ad hoc funds.

In theory, the FLMM could have played a strong, coordinating role. But the advisory panel found little evidence of it doing so or wanting to, which was no surprise given how lightly resourced the entity was.

As early as 2008, potential LMI users were demanding more granular information. They wanted the data at the local level and with fine details on occupations and skills. In contrast, most of the information being generated was highly aggregated by region and occupation. As was typical in the broader LMI domain, the response to the call for granularity was uncoordinated and uneven.

The federal government, through Service Canada, helped a bit. Some provinces and even municipalities gathered their own local information. Several provinces paid Statistics Canada to increase the size of key surveys in their province, particularly the Labour Force Survey. But even those requests were not coordinated.

The panel felt its most important recommendation was the establishment of an appropriate governance structure, under FLMM’s direction, to coordinate LMI. There was a desperate need for some entity to step forward and take charge. To identify information gaps. To link the pieces of information already in existence. To make the information easily available to the agents who could use it. To explain the data. But what entity?

Another critical recommendation was that the FLMM “should be recognized by FPT governments and all Canadians as the Pan Canadian body responsible for the coordination of LMI.”24 In a way, the recommendation was an obvious one, as the panel was a creature of the FLMM. However, it may not be realistic under current circumstances. The FLMM has no permanent secretariat and little funding. The provincial co-chair typically provides a few people to support activities, but total resources have not been adequate or sustained for sufficient time to pull off what the panel recommended. The panel was well aware that its recommendation meant that FLMM would need to change significantly if it was to play the role being set out for it.

Since the panel’s report, the FLMM’s Labour Market Information Working Group and its senior officials have worked on addressing key challenges and gaps in the LMI system. However, the ministers themselves did not meet -between 2010 and late 2013. Perhaps as a sign of what was to come, the session to present the panel report was cancelled.

In all, the FLMM has not come close to assuming the mantle urged upon it by the panel.

This lacuna on the governance side largely explains why the changes to LMI since 2009 have been more piecemeal than holistic. It also explains why Ottawa, Statistics Canada and individual provinces and territories have implemented recommendations incrementally rather than with the urgency called for by the panel.

Another serious gap identified by the advisory panel was the lack of a job vacancy survey. It noted the contrast between the detailed information available on the unemployed, in good part because of the employment insurance program, and the almost nothing that is known about where job openings might be and their requirements. This seems a ready-made recipe for labour market mismatches, as the unemployed and those looking to change employment do not have adequate information. The lack of a gauge on labour demand also makes it difficult for educational institutions to know where they should devote resources.

Statistics Canada has created a job vacancy survey. Yet its accuracy is challenged in light of the suggestion in the last two federal budgets of an aggregate job vacancy rate roughly three times that estimated by Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada has also implemented the panel’s recommendation that Web-based data, including LMI, be made available free of charge. Users should not have to go through the expense, and more particularly the nuisance, of paying for data.

The panel was also greatly troubled by gaps in the information on post-secondary education, particularly during study and post-graduation outcomes. Work has been done in conjunction with the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC) to address these problems, but they remain. Even a more satisfactory handling of the National Graduates Survey is not an appropriate endgame. We should be in a position, by anonymously matching student identifiers to information such as tax returns, to track with considerable precision what happens to trade, college and university graduates by geographical area and field of study. Instead, we get only a partial picture from some provinces, the occasional academic report and, every five years, the National Graduates Survey. Not only is the information partial, but it is not broadly communicated to the public and certainly not to prospective post-secondary students.

It is often alleged that students are pursuing the “wrong” fields of study. This implies that they are not studying in fields that have high employment and income prospects. There isn’t compelling evidence to judge how true this is. But even if it is valid, there are several other considerations. First, students may choose their studies on broader considerations, such as personal interest. And caution must be exercised here. Some people who become leaders in a specific field do not have an educational background in that field. There is a lot of scope for different backgrounds and perspectives. There is nothing wrong with that.

Second, and this is the main concern here, prospective and current students may not have a realistic perspective on their employment and income prospects by field of study. Indeed, there is no reason, given the data problems, to believe they would. But they should. All young people should know well before choosing their post-secondary education options what lies ahead for them after graduation. That information would, of course, be based on information about students who have come before them, and there is nothing to assure that it applies in the future. But the information is critical for making informed choices. Finally, there is the issue of whether educational establishments and governments are creating and funding appropriately the various fields of study.25

When considering education data, the panel called for a strong partnership among the FLMM, CMEC and Statistics Canada. Some good work has been done since 2009, but the result is far from what the panel called for.

Clearly, the panel bemoaned the dearth of information on job vacancies. The -Statistics Canada series on job vacancies is of great help, such as it is. But difficulties remain. First, there is the controversy over whether the numbers are reliable, given the much higher vacancy rate cited in the last two federal budgets.

Second, the current series is largely of use to researchers, and less to people searching for work. The results are available only on a provincial basis and are aggregated into a small number of industries, masking the dissimilarities -between individual occupations. Knowing there are “professional, scientific and technical services” jobs somewhere in Ontario does not help the job seeker much. Where in the province are the jobs? And what are the skill requirements?

Furthermore, the survey’s inadequacy for policy purposes has become apparent in the current debate over the Temporary Foreign Worker Program: employers’ claims of shortages of specific workers cannot be analyzed because of the lack of local or detailed occupational data.

The job vacancy survey would also have to provide richer content to be useful for labour market planning. For example, it would be helpful to know how long vacancies have existed and what means employers have used to try to fill them. In short, rather than just driving to a vacancy number, the survey should pose some questions.

The job vacancy survey and the elimination of a user fee for Web-based CANSIM data from Statistics Canada have been noted. Improvements made by the federal government to its Job Bank are also noteworthy. Job Bank is an electronic service that lists job postings provided by employers from across Canada. Importantly, Ottawa has struck agreements with private sector job boards to increase the number of its Job Bank postings.

On April 12, 2014, Job Bank listed 107,055 available positions. An indicator of the bank’s granularity is that 25 of those vacancies were for economists. However, some of the positions were originally posted almost a year ago so may not still be available. A scan of other occupations revealed a similar phenomenon. Hence, the number of active positions available on Job Bank is likely well below the total of 107,055, as openings more than a few months old have likely been filled or withdrawn.

Within Job Bank, users can subscribe to Job Alert and receive twice-daily notices of jobs that match the criteria they specify. The Working in Canada Web tool was improved, and is now part of Job Bank. The site provides valuable information for Canadians looking for work or contemplating a job change. It contains information on occupations, job opportunities, education requirements, main duties, pay, employment trends and the jobs outlook.

Some of the provinces are also promoting LMI more actively. Take the WorkBC website. Among other things, the site contains a list of job openings throughout the province, analyses of the provincial labour market and the results of a job survey among post-secondary education graduates. British Columbia is now turning attention to using this LMI to determine short- and long-term education needs.26

Given the value of these improved job search tools, it seems odd that Ottawa or the FLMM is not doing more to create awareness of what is available. Other than employment insurance recipients, who automatically receive Job Alerts, people are picking up job information for the most part through word of mouth. Governments should be shouting from the rooftops about their services. Perhaps Ottawa is shy about promoting these sites because labour market matters have been largely devolved to the provinces. It is hard, however, to envision a constitutional squabble breaking out over attempts to help people find work.

Since the advisory panel’s report, Statistics Canada, with funding from Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), has introduced the biennial Longitudinal and International Study of Adults. With a focus on labour, education and training, it may provide further valuable LMI.27

Statistics Canada has also made progress in linking data files, including for workers. Such linking could increase the value of efforts to see how tax and employment insurance data could be used to provide LMI.

As well, ESDC has piloted a workplace survey that focuses on skills shortages, hard-to-fill vacancies, employment and turnover.28 Work is being done to improve information on disadvantaged participants in the labour market through the Canadian Survey on Disability, the Aboriginal Peoples Survey and the First Nations Regional Early Childhood, Education and Employment Survey. ESDC’S Canadian Occupational Projection System, which analyzes future labour market needs and potential imbalances, has been improved and now covers more than twice the number of occupations.

The advisory panel was troubled by Canada’s failure to provide a complete set of data to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for its flagship document Education at a Glance. In 2009, Canada filled in fewer than half the indicators used by the OECD for international reporting and comparison.29 The incompleteness made it impossible to evaluate Canada’s education system and its outcomes relative to those of other developed countries. Nevertheless, for the 2014 edition of the OECD publication the response rate was increased to almost 90 percent,30 for which Canadian officials are to be commended.

The federal government and CMEC have collaborated with the OECD’s -Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies and the Programme for International Student Assessment. Data from these surveys are comparable with those for other countries and will be used in OECD publications.

While the federal and provincial governments have clearly been working on improving LMI over the past five years, little has changed in too many areas. I will cite only a few of the gaps here.

The FLMM has not become the clearing house for labour market research or the leader in filling information gaps, as the advisory panel had envisaged. No portal has been created through which comprehensive information from across the country can be accessed.

The FLMM has not coordinated a plan for LMI related to education with CMEC (or with Statistics Canada). The cost of the education surveys is still not embedded in Statistics Canada’s budget. New and improved pathways have not yet been put in place to convey education and LMI to key users such as students, job seekers, educational institutions, career advisers, policy-makers, employers, unions and government agencies. We still do not have a comprehensive, national student identification number system. This is critical for determining outcomes on employment and income.

LMI is still based on net flows, a measure that misses much of the dynamic, as a net employment gain in one month may disguise huge movements in and out of employment. The panel recommended collecting and publishing gross labour flows to better understand employment decreases and increases. Very different labour market dynamics can produce a net employment increase of 20,000. For example, the increase could reflect the addition of 300,000 jobs and the loss of 280,000, or it could mean a gain of only 50,000 and a loss of 30,000.

We still do not have comprehensive data on employee layoffs. We still do not have a labour price index. And the Immigration Data Base is not being used along with the Labour Force Survey to report annually on how immigrants are performing in the labour market.

The panel heard competing arguments on how best to improve local LMI. Some emphasized increasing the size of existing surveys such as the Labour Force Survey. Others said, among other things, that greater use of administrative data would be more promising.

For its part, the panel recommended that an intense effort be made to identify the best way forward and then pursue it. Attempts have been made to improve local information, such as strengthening the analysis in Service Canada regions. But it seems that the larger question of how best to proceed has not been addressed.

Perhaps most disappointing, at least to me, as the chair of the panel, the FLMM did not comply with the final recommendation of preparing a follow-up report a year later as to the fate of the recommendations and what, as applicable, might have been done instead. Even if such a report were issued now, four years later, it would be welcome and highly useful.

The simplest suggestion for getting more actionable LMI would be to implement the remainder of the FLMM Advisory Panel’s recommendations. But to leave it at that would be to ignore why many of the recommendations have not yet been executed. There must first be a clear understanding of the obstacles, and then there must be a plan to overcome them.

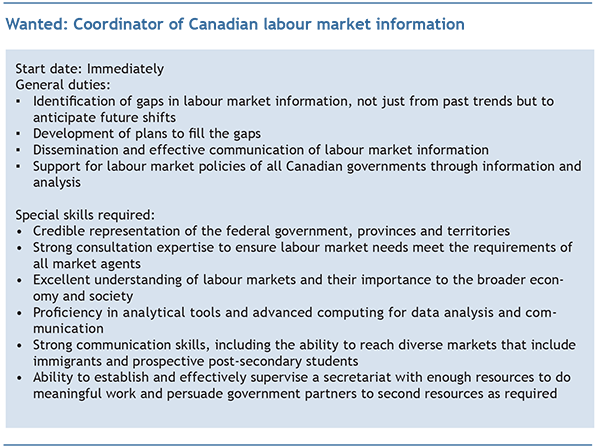

The principal obstacle to greater progress is that no entity has stepped forward to take charge. Many have done impressive work on their own, in their own domains. But there has not been strong, effective coordination. So a help-wanted ad is in order.

In 2009, the advisory panel recommended that the FLMM take this job. Five years later it is important to ask whether it should be given to someone else. Unfortunately, few possibilities come to mind.

Canadian governments could create a new, separate agency to do the job. A possible model is the Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency, which advises the national government on skill needs and development. But that agency performs only a subset of the tasks envisioned here. Furthermore, very tricky governance issues would have to be resolved to operate an agency that serves 14 governments. It seems probable that so much work would go into overseeing the agency that it might be more efficient to perform the tasks directly within some form of government.

Ottawa – principally through ESDC – is the only one of the 14 governments that has a natural national perspective and mandate. And because of the department’s history and size, it has the resources to do much of the task. But given that most labour market policy responsibilities are provincial, the federal government does not have the legitimacy to coordinate national LMI on its own.

Statistics Canada, in effect, could be the agency coordinating LMI. It meets most of the job requirements. But it does not have a direct connection with policy.31 So it would require considerable guidance from the 14 governments. Again, an appropriate governance structure would be required for that guidance.

By process of elimination, the question comes back to where the panel began: the FLMM. It brings to mind Einstein’s definition of insanity as doing the same thing, over and over again, expecting a different result. In this case, however, we are not repeating the same recommendation from five years ago, given that the FLMM has not expressed much interest or capacity to take on the job the panel wished to assign it. Instead, one possible way forward is for FLMM to become the main coordinating body but ease its task somewhat by more explicitly carving out some of the LMI domain for allocation to other players.

Here are three simple, stand-alone measures that could have a major impact on the quantity and quality of LMI.

A starting point could be the delegation, with appropriate resources, of much more of the LMI gathering responsibility to Statistics Canada. The agency should first be better connected with the federal, provincial and territorial officials who use its LMI for policy purposes.

Statistics Canada could even apply a governance model being used for the collection of justice statistics. An intergovernmental coordinating body oversees the data and analytical output of Statistics Canada’s Justice Statistics Division. It is designed to meet the needs of all the provinces and territories, the federal Department of Justice and the public.

If this model is adopted, attention should then turn to improving our understanding of the basic demand and supply of the labour market. On the demand side, the job vacancy survey should be enhanced to provide local information with greater granularity on occupations, and questions should be added to -improve the survey’s usefulness as a policy tool.

Since graduating students constitute the largest supply of entrants into the labour market, the current largely unrelated and partially related surveys should be consolidated, extended to fill the gaps and given permanent funding. Work should also advance on establishing the ability to monitor employment, income and other outcomes through linking administrative and tax data. And Statistics Canada should be charged with recommending the best way to collect local LMI.

After consultation with other governments and stakeholders, ESDC could be recognized as the principal source for national information, building on its Job Bank and other services. Given these existing responsibilities, ESDC would be best placed to oversee the continued development of a single portal of LMI, bringing together data on labour market conditions across the country.

With significant parts of the total LMI domain more clearly assigned to -Statistics Canada and the federal government, the FLMM’s task might be more manageable. But it would still need to be radically changed in order to fill the job description above. Ministers would have to meet more regularly. It would need a secretariat with adequate resources. It would have to build strong consultation and communication capacities.

The real state of labour market conditions was unclear in 2008 when the FLMM Advisory Panel began its work. Despite progress in some areas of information provision, confusion still reigns. This does not need to be the case. A greatly improved LMI system would not be expensive. The panel estimated the cost at $49 million a year spread across 14 governments. That is minuscule relative to total public spending. Money is always scarce, especially when a period of austerity lingers for many governments. But the lack of progress on LMI is not primarily a financial problem. The governance complexities arising from multiple jurisdictions are much more of an obstacle.

And that is a shame, because so much is at stake. Serious assertions are being made about labour shortages. About companies not able to expand because they can’t find the right workers. About companies and employees not investing enough in training. About people unable to find work that fits their skill set. About students pursuing fields that will not lead to good employment while more promising areas go undersupplied.

In each case, there is likely some validity to the claims. But we simply don’t know enough to provide a critical assessment. Hence, it is difficult to know what to do – as employers, as employees or as governments. Better LMI will not solve all the problems in the labour market. But it would provide a critical platform from which all agents could make better decisions.

A number of opportunities exist to roll out improvements to labour market information. The issue should be on the agenda at the July 2014 meeting of the Forum of Labour Market Ministers. Responsibilities for information gathering could be formalized as part of the Labour Market Development Agreement, to be completed this year.

If the various players in the LMI field, including the 14 governments and -Statistics Canada, up their game and find an effective coordination mechanism, Canada could have one of the best LMI systems in the world. This would lower unemployment and raise Canadians’ incomes and well-being.

Montréal – Lorsqu’elle est de qualité, l’information sur le marché du travail (IMT) permet aux employeurs, aux gouvernements et aux chercheurs d’emploi de prendre de meilleures décisions. Mais les améliorations apportées ces dernières années au système d’IMT restent insuffisantes, notamment parce qu’aucun organisme gouvernemental – y compris le Forum des ministres du marché du travail – n’a pris les choses en main. Dans une nouvelle analyse IRPP Insight, Don Drummond, qui a présidé en 2009 le Comité consultatif fédéral-provincial-territorial sur l’information sur le marché du travail, soutient qu’Ottawa doit prendre les devants s’il souhaite doter le pays d’un système IMT complet et national. Le gouvernement pourrait élargir par exemple le mandat de Statistique Canada ou créer un organisme d’IMT distinct.

Selon l’auteur, la confusion, qui perdure depuis plusieurs années, quant la situation réelle du marché du travail est en grande partie attribuable à l’insuffisance des données.

« Les problèmes évoqués de la pénurie de main-d’œuvre, du faible investissement des employeurs dans la formation ou de la difficulté pour des chercheurs d’emploi de trouver un travail qui correspond à leur compétences reposent sans doute sur une certaine réalité, convient l’auteur, mais nous manquons tout simplement des connaissances nécessaires pour en effectuer une évaluation critique. »

Des progrès ont été accomplis depuis que le Comité a déposé son rapport en 2009, par exemple la création par Statistique Canada de l’Enquête sur les postes vacants. Mais il manque toujours de données récentes et détaillées sur les tendances du marché de l’emploi local et des professions, la situation des diplômés ou les pertes et les perspectives d’emploi. De surcroît, le public n’est pas bien informé des données existantes.

« Si la confusion persiste quant à la situation actuelle du marché du travail, c’est surtout parce qu’aucune entité n’a assumé la responsabilité de l’IMT, estime donc l’auteur. Or le Canada pourrait se doter d’un des meilleurs systèmes au prix d’efforts relativement modestes, ce qui améliorerait le fonctionnement du marché du travail et amoindrirait le chômage tout en favorisant le bien-être et les revenus des Canadiens. »

Don Drummond exhorte ainsi Ottawa à collaborer avec les provinces et territoires aux objectifs suivants :

-30-

On peut télécharger sans frais le document Wanted: Good Canadian Labour Market Information,de Don Drummond, sur le site de l’Institut, au irpp.org/fr/.

Pour de plus amples détails ou solliciter une entrevue, veuillez contacter Shirley Cardenas au 514 594-6877 ou au scardenas@nullirpp.org

Pour recevoir par courriel notre bulletin mensuel, veuillez vous abonner à Infos IRPP.

Canada has poor labour market information and as a result we do not have answers to simple questions that affect Canadians’ livelihoods. Employers complain they cannot find enough skilled workers, yet the Canadian unemployment rate is far from its lowest level. Does Canada not have enough workers or are they in the wrong places with the wrong skills? Why are wages not rising more sharply in occupations in demand? In the past, graduates of general college and university programs have done well economically and socially. Should young people disregard the record and heed suggestions there won’t be good jobs for them? The Canada Job Grant is being introduced to encourage employers to provide more training to their workers; but how much training and what kind of training do employers now provide?

The federal, provincial and territorial governments were concerned about not having answers to similar questions in 2008, and through the Forum of Labour Market Ministers (FLMM) struck an Advisory Panel on Labour Market Information, of which I was the chair. The Panel made 69 recommendations that, at an annual cost of less than $49-million and spread across 14 governments, would have provided answers to the questions above and a great number of others. Jason Kenney, federal Minister of Employment and Social Development, recently claimed two-thirds of the recommendations have been or are in the process of being implemented. Unfortunately, many more are in process than accomplished. And most of those in process are in early stages of preparation. Meanwhile, even some of the information available in 2008 has been jeopardized by successive budget cuts, particularly to Statistics Canada, the main provider of labour market information.

As I argue in a paper for the Institute for Research on Public Policy, the main reason so little progress has been made is that no entity has stepped forward to drive a national program to collect, disseminate and explain better information. The Advisory Panel naturally recommended the FLMM play this co-ordinating role. But they have not taken up the mantle of leadership.

The need for better information has never been greater. Not only would it benefit Canadian employers and workers, but recent difficulties with policies such as the Canada Job Grant and the Temporary Foreign Worker Program highlight that policy action must be shaped by good information.

While the goals of the Advisory Panel are still valid, a different path is needed. Federal, provincial and territorial divisions seem too much for any single entity to do it themselves. So the task should be broken into more discrete pieces that can be pursued by various players. The provinces should continue to improve information within their borders. The federal government should take the lead on providing national information. With strengthened components, the FLMM should then be able to effectively co-ordinate efforts to ensure a comprehensive pan-Canadian LMI system.

Statistics Canada should be given the mandate and necessary resources to improve its coverage of labour market information. In particular, it should implement a better job vacancy survey, figure out how to provide more granular local and occupation data, and more closely monitor the economic and social outcomes of college and university graduates.

One of the few Panel recommendations to be implemented was the creation of the job vacancy survey. But with the results aggregated into a small number of industries and available only at the provincial level, the survey is of little help to job seekers or policy analysts. In the last two federal budgets, the federal government further clouded the view of job vacancies by publishing their own estimates, which were well above the official Statistics Canada figures. It has recently been acknowledged that some double counting went into the budget numbers but a full reconciliation to the Statistics Canada figures has never been provided.

In most cases genuine labour shortages are restricted to particular occupations and geographical regions. For the most part data is not available at this level of granularity. On Wednesday, Minister Kenney announced that the government intends to expand the collection of data on vacancies and wages at the regional level. When implemented by Statistics Canada, this will be a good step forward.

Well before young people graduate from high school they should have a good sense of the likely employment and income prospects of various fields of post-secondary study. More timely surveys with appropriate dissemination of the information could fill part of this gap. Better still would be a comprehensive program across Canada to anonymously link student identification numbers with income data from tax returns.

Better labour market information will naturally improve the decisions of employers, workers and education institutions. There will of course still be obstacles to a well- functioning labour market. But with the information, policies of the federal, provincial and territorial governments can strategically target the issues identified.

Don Drummond is the Matthews Fellow in Global Public Policy, Queen’s University, and was Chair of the Advisory Panel on Labour Market Information in 2008-09.