L’individu a toujours été l’unité de base du régime d’imposition canadien. Aussi la proposition visant à permettre aux conjoints de se répartir entre eux leurs revenus à des fins fiscales a-t-elle soulevé un vif débat dans les milieux politiques. Le Canada permet la répartition des revenus de retraite entre conjoints depuis 2007, ce qui ouvre la porte à un traitement similaire pour les autres types de revenus. Le Parti vert s’est prononcé en faveur d’une telle proposition, qui est également vue d’un bon œil par le Parti conservateur. Même le porte-parole du Parti libéral en matière de finance admet que le public est favorable à l’idée. Cependant, les implications d’un tel changement sont plus complexes qu’on pourrait penser. C’est pourquoi il importe d’analyser cette question attentivement avant de procéder dans ce sens.

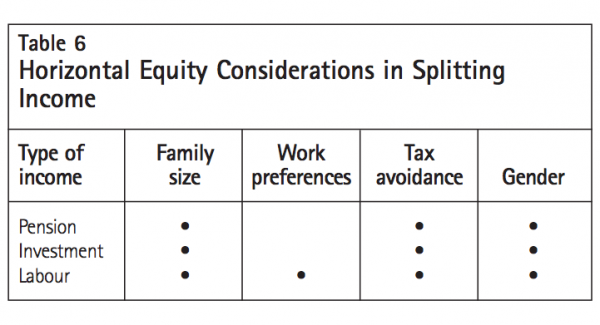

Cette étude évalue de manière approfondie les propositions favorisant la répartition des revenus entre conjoints dans le cadre du régime fiscal canadien en les comparant aux autres options possibles. Selon l’auteur, l’équité est le critère fondamental pour établir quelle est l’unité fiscale appropriée dans le cas des couples. Il faut considérer aussi bien l’équité horizontale — c’est-à-dire le traitement fiscal égal de personnes qui se trouvent dans une situation identique — que l’équité verticale et l’égalité des sexes. L’équité horizontale exige qu’on tienne compte de certaines différences au niveau des besoins (taille de la famille), des préférences (emploi rémunéré ou travail au foyer) et des possibilités d’évitement fiscal. Parmi les principaux autres critères qu’il faut également examiner, mentionnons l’efficience économique, la simplicité, les coûts et l’effet de diverses approches sur le comportement des individus.

Selon l’auteur, le Canada peut tirer des leçons utiles de l’expérience des États-Unis et de l’Europe en matière de traitement fiscal des couples. Ainsi les pays qui ont maintenu ou adopté l’individu comme unité fiscale de base permettent certaines formes de répartition entre conjoints pour les revenus qui ne proviennent pas de l’emploi. En effet, l’analyse détaillée des divers critères en jeu indique qu’il convient de considérer séparément le traitement des revenus de retraite, de placement et de travail.

Les arguments en faveur de la répartition des revenus de retraite entre conjoints reposent sur l’iniquité qui existe entre les couples qui ont accès aux REER de conjoint et ceux qui n’y ont qu’un accès restreint en raison de leur participation aux régimes de retraite de l’employeur. Selon l’auteur, la nouvelle disposition fiscale adoptée en 2006 devrait néanmoins être modifiée afin de limiter la part des revenus de retraite qui peuvent être répartis et éviter que cette mesure ne serve à contrer la récupération fiscale des prestations de la Sécurité de la vieillesse. Une alternative serait de permettre au conjoint dont le revenu est moins élevé de transférer la partie inutilisée de sa marge fiscale au conjoint dont le revenu est plus élevé afin de réduire le taux d’imposition appliqué à ses revenus de retraite.

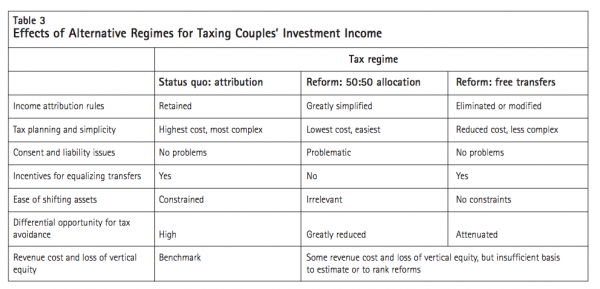

Les considérations liées à l’équité et au respect des lois fiscales militent en faveur d’une forme quelconque de partage entre conjoints pour les revenus de placement, ainsi que d’un assouplissement important des règles d’attribution de ces revenus. Cela permettrait à un plus grand nombre de couples de bénéficier d’avantages fiscaux dont se prévalent déjà les couples bien nantis et bien conseillés. L’auteur présente deux options, soit l’attribution obligatoire à parts égales de l’ensemble des revenus de placement du couple, soit la possibilité de transférer des actifs d’un conjoint à l’autre, sans attribution des revenus. C’est cette seconde formule qui respecte le mieux le critère de l’égalité des sexes.

Pour ce qui est du partage des revenus d’emploi, l’étude examine différentes situations : les couples à revenu unique par rapport aux couples à deux revenus ; les couples à deux revenus ; et les couples à revenu unique mais où un conjoint aide l’autre dans son travail. Divers facteurs entrent en jeu dans cette analyse : les préférences en ce qui concerne le travail, la valeur des biens et services produits au foyer et les coûts liés au travail à l’extérieur du foyer. Dans les trois cas, l’imposition des revenus d’emploi sur une base individuelle s’avère l’approche la plus appropriée.

L’égalité des sexes est un critère particulièrement pertinent dans toute cette analyse. Le choix de l’entité fiscale peut avoir des conséquences importantes pour le bien-être et l’autonomie des femmes mariées et des conjointes de fait. L’imposition conjointe ou le partage des revenus d’emploi aurait tendance à renforcer le rôle traditionnel des femmes qui restent au foyer, se spécialisent dans l’éducation des enfants et prennent une part moins active au marché du travail.

Cette étude préconise le maintien de l’unité fiscale individuelle pour ce qui a trait aux revenus d’emploi, assorti de dispositions permettant le partage des revenus de retraite et de placement. C’est là l’approche qui correspond le mieux aux critères d’équité horizontale et à l’égalité des sexes. Bref, la politique fiscale canadienne devrait favoriser des formes limitées de partage des revenus mais s’en tenir par ailleurs à l’entité fiscale individuelle.

The introduction of tax splitting for pension income has provoked debate over whether Canada should extend splitting to other types of income. Indeed, some of the same people who advocated pension splitting are leading the call for broader income splitting for couples. As once Tory, then independent and, as of writing, Liberal MP Garth Turner asserted, “Now that we’ve opened the door to pension-splitting for seniors, it’s only a matter of time before this principle extends through society” (Bailey 2007). Similarly, economist Don Drummond remarked, “I can’t see any particular logic of why, as a concept, it would be accepted for pension splitting and not be viewed as acceptable for general income splitting” (quoted in Whittington 2006). Popular debate over income splitting has been lively, with newspaper editorialists weighing in both strongly favourable1 and clearly opposed.2 Similarly, columnists and media commentators have taken positions both supportive (see Coyne 2006; Taylor 2006; Mrozek 2007) and critical (see Drache 2006; Philipps 2006; Cayo 2006; Weir 2007) of general income splitting.

The most common popular arguments for general income splitting are twofold. First, splitting would recognize the contribution of — and provide tax relief for — a one-earner couple’s at-home spouse3 who is caring for young children. Second, splitting would apply taxes more equitably between the spouses in two-earner couples who have the same total income but a different division of earnings. An additional, recent argument for general income splitting is that it is unfair to allow senior couples to split their pension income while prohibiting other couples from splitting other types of income. Others have pointed to the inconsistency of applying taxes on an individual basis while using joint income for income security programs.4 Thus, the arguments advanced most frequently to promote income splitting fall under the heading of fairness or equity.

These arguments might, at first blush, be appealing, but income splitting also raises intriguing political issues. In 1999, the Reform Party provoked sufficient concern over the asserted “unfair taxation” of one-earner couples to spur a Liberal government to undertake a parliamentary investigation (Canada 1999b).5 In 2000, Reform’s successor, the Canadian Alliance Party, advanced a flat tax proposal as a way to resolve the two main equity issues cited above. The Conservative Party’s 2005 inaugural policy declaration committed to income splitting as a way to eliminate inequities between dualand single-income couples, including senior couples with a single pension. Official approval of pension splitting in 2006, driven by the Harper government’s need to placate seniors riled over the imposition of a tax on income trusts, has encouraged advocates to push for broader income splitting. There is no denying the potential electoral appeal of general income splitting. Liberal finance critic John McCallum has conceded that income splitting “would be highly beneficial” to an important segment of voters, and Green Party leader Elizabeth May has endorsed the policy as pro-environmental.6 One observer has asserted, “As a green, tax-cutting, family-friendly policy, income splitting has the potential to become the 21st-century equivalent of a chicken in every pot” (Taylor 2007).

While recent events seem to be leading Canada toward the adoption of more general income splitting, there are good reasons to pause for careful scrutiny before proceeding. Income splitting, or some form of joint taxation of couples, is not a minor policy shift. Rather, it is a fundamental change to a basic design element of the direct personal tax system: the definition of the tax unit (the other elements being the tax base and the rate schedule). Income splitting would have a significant effect on the distribution of the tax burden, particularly for many top-income households. Extensive analyses of the behavioural effects and policy implications of alternative definitions of the tax unit are already available, mostly from US and European research and, to a lesser extent, from Canadian studies. Foreign experience with income splitting and other methods of joint taxation can be instructive for the Canadian situation. The issues involved in defining the tax unit are more complex and cross-cutting than most income-splitting advocates realize. Moreover, experience elsewhere suggests that general income splitting would raise even more controversial issues than it would resolve.

In this study, I provide a comprehensive assessment of the appropriate tax unit in Canada, whether the individual or the couple,7 with particular attention to income splitting as a special case of joint taxation for couples. My central criterion for assessing these choices is fairness, or equity — the focus of most popular dialogue. I also consider other major policy criteria, such as incentives for paid and unpaid work, marriage and separation; ease and costs of tax compliance and financial planning; economic efficiency; and revenue implications and distributional effects across income groups. I begin by carefully exploring the “horizontal equity” concept needed to give substance to “fairness”; I further consider gender equity and vertical equity and their relation to horizontal equity. I then examine alternative definitions of the tax unit and the associated issues of tax equity between couples and single persons. The heart of my analysis investigates each of three types of income — from pensions, investments and labour earnings — to assess what equity and the other criteria imply for the choice of tax unit and income splitting.8

Assessing the equity of any public policy requires an objective criterion, since “fairness,” like beauty, hinges on the beholder. The horizontal equity concept provides such a standard — one that economists, tax law scholars and policy analysts have long used. Many synonymous formulations exist for horizontal equity, but the most common is “the equal treatment of equally situated individuals” or, in brief, “the equal treatment of equals.”9 A more pointed statement of the horizontal equity principle is “that those who are in all relevant senses identical should be treated identically” (Atkinson and Stiglitz 1980, 353; emphasis added). This version emphasizes the rejection of any arbitrary discrimination in public policies, although intentional differentiation in policy treatment (taxes or benefits) based on relevant characteristics might be acceptable. The appeal of the horizontal equity principle stems from a basic notion of fairness. As stated long ago by eminent economist Arthur Pigou, horizontal inequity creates “a sense of being unfairly treated [which is]…in itself an evil” (1949, 50).10

Horizontal inequity typically is not an intended part of tax legislation, but it is difficult to avoid, given the diversity of taxpayers, the complexity of economic and financial arenas and the multiplicity of tax policy objectives. Moreover, reforms that seek to improve horizontal equity among some “equals” often worsen it relative to other “equals.” For example, assume that individuals A, B and C are equally situated for taxation purposes but various differences among them mean that A pays more tax than B, who pays more tax than C. A prospective policy reform might reduce the horizontal inequity between B and C by reducing the tax on B, but if it cannot address the situation of A, it will simultaneously increase the inequity between A and B. If no feasible policy reform exists that can remove inequities across all these “equal” taxpayers, then whether the partial reform improves or worsens horizontal equity overall hinges on a value judgment.11 This problem becomes manifest in my later analysis of specific income types. Given that tax policy has multiple objectives, any prospective gain in horizontal equity has to be weighed against other effects (Ravallion 2004, 18).

Before I apply the horizontal equity concept, let me dispense with one common misconception. Many advocates argue that income splitting for couples is implied directly from horizontal equity, since only under splitting (or a joint taxation variant) will couples with equal incomes be taxed the same. Yet, as an early analyst of this issue observed, “‘taxing [equally] families with the same incomes’ is not a criterion at all, but merely one of the possible conclusions that may or may not be reached after analyzing the basic principles” (Dulude 1985, 85). That is, taking the couple, rather than the individual — whether a single person or a spouse — as the unit of analysis predisposes the answer as to horizontal equity in the taxation of couples. Analysis of public policies must focus on the well-being of individuals, and the well-being of couples is simply some aggregation of the well-being of the partners.

The most challenging aspect of making the horizontal equity concept operational is to find a standard for gauging when individuals are “equals.” Economists tend to prefer a utility measure of individual well-being, but that poses implementation problems since utility is not observable. What we require is a broad measure of total economic resources or real living standards — something that is both measurable and a good proxy for economic wellbeing. For purposes of the personal income tax, a natural candidate is pretax income: two individuals are thus deemed “equal” if they have the same amount of income before taxes are imposed.12 However, while the income measure is commonly applied in assessing horizontal equity for income tax policies, it has major deficiencies. For individuals to be equal “in all relevant senses,” they must not only have the same realized incomes but also confront the same costs and opportunities and possess the same preferences.

Income can still serve as a useful starting point for assessing “equals,” so long as we can adjust for factors that vary across individuals in converting money income into real living standards. That is, we need methods to account for the heterogeneity of individuals in key dimensions. Exactly which characteristics should be recognized and which discounted for tax policy purposes entails value judgments that ultimately reflect society’s priorities at a particular time and place. For both pragmatic and ethical reasons, I ignore differences in individual utilities that are either idiosyncratic (such as a miser versus a bon vivant) or arise from personal status (such as the intrinsic utility of being married versus living alone). With appropriate adjustments to pretax incomes to account for relevant factors, a useful metric emerges for assessing when people can be regarded as “equals.” Various tax provisions are employed to refine the use of income as a measure of equals; as one analyst has stated, “[s]urely the aim of the tax-transfer policies whose horizontal equity is being assessed…is precisely to correct at least some of those inequities in the original income distribution?” (Le Grand 1987, 434).13

I focus here on three key respects in which individuals can differ: (1) in family size and, hence, in the size of their household budgets; (2) in preferences, in particular for market goods versus home-produced goods and leisure; and (3) in tax-saving opportunities that are open to some but not to others having the same income. Another important respect in which individuals differ is their gender; such differences enter my analysis later as another aspect of horizontal equity.14

Any measure of “equals” has to adjust nominal incomes for factors that affect needs or living costs, the most prominent of which is variation in family size.15 When can we say that a family of size X with income IX is “equal” to a family of size Y with income IY? If two households differ in size, and thus in the number of members that their income needs to support, they will not be economic “equals” when they have identical nominal incomes. Economists have devised a solution to this problem in the concept of “equivalence scales.”16 By studying the budgets of households of different sizes, they have derived measures of the relative income needed for families of different sizes to achieve the same real living standard. These measures are stated as adult-equivalence scales, defined as the ratio of income a family of a given size needs to achieve the same real living standard as a single person. Equivalence scales provide useful guidance in setting the relative size of personal exemptions or credits — and the rate schedules — for families of varying sizes.

For two adults living together, the adult-equivalence scale is less than 2, because of the scale economies from such items as rent, utilities and furnishings. That is, two people living together have lower total costs than if the two lived separately. But the adult-equivalence scale for a couple is greater than 1, because scale economies are not unlimited. Typical estimates for the adult-equivalence scale of a couple range between 1.4 and 1.7; accordingly, I use a figure of 1.5, so that, in the jargon, a household of two contains 1.5 “adult-equivalents.” These scale values are used to convert the incomes of families of different sizes into a measure of adult-equivalent incomes. For example, the income of a two-adult household is divided by 1.5, which can be directly compared with a single person’s income. Households of differing sizes but with the same adult-equivalent incomes are taken as “equals.” This issue clearly is relevant to the issue of income splitting, since horizontal equity for taxpayers requires not only fairness among couples but also fairness between couples and singles17 — a theme I develop later in the study.

One important, and common, way in which individuals and households can differ is in their relative preferences for work. More specifically, this choice is between paid work and the market goods and services it affords versus home-produced goods and services and leisure time. Two individuals with the same wage rate who allocate their time differently between the labour market and the home will have different levels of income, but they might still be regarded as “equals” insofar as their potential income would be the same if both worked for pay full time.18 Another way to look at it is that someone who chooses to spend more time at home tends to generate more income in kind than in cash. In its broadest sense, income is the consumption of real goods and services — both marketand home-produced — and leisure. Hence any attempt to measure real living standards across individuals, and thus gauge “equals,” ideally should adjust incomes for differences in working time.19

In practice, the income tax does not adjust for differences in working time across individuals. That goal could be achieved, but it would require additional reporting on employees’ work hours (or wage rates) as well as their total earnings. Pursuing that route would eliminate the largest economic distortion of income taxation, the bias between work and leisure, which yields disincentives to work. In a related context, one can approach more closely the economic ideal of measuring potential, rather than actual, income. For instance, when comparing one and two-earner couples, we can choose to recognize or we can choose to ignore the value of the additional home-produced goods and services and leisure of one-earner couples. But if we do the latter, we will underassess their real living standards relative to those of two-earner couples. My later analysis shows how this factor enters into evaluating the proper tax unit for couples.

Individuals with identical incomes can differ in yet another dimension that is relevant to assessing horizontal equity. Some people are simply better able to avoid paying tax because of their sources of income or their superior knowledge about or access to tax planning. Taxpayers, in fact, vary widely in their circumstances and ability to transfer assets or taxable income and thereby split their income with a spouse. Canada’s complicated tax system has unintentionally created numerous horizontal inequities in the pursuit of other tax policy goals.20 If similar tax-avoidance opportunities were easily and equally accessible to all tax payers, they would not constitute horizontal inequities; it is the differential access to tax avoidance that makes for unfairness.

What should be done about tax-avoidance opportunities that give rise to horizontal inequity? The first-best policy response is to close off the opportunity directly through legislative or regulatory changes, if it can be done at an acceptable cost in terms of tax agency administration and enforcement and taxpayer compliance burdens. If this course of action is technically infeasible, too intrusive into people’s lives or unacceptable at the political level, then it might be possible to enhance horizontal equity by extending comparable tax-reduction opportunities to other groups similarly situated to those who are already avoiding tax. Often, this approach brings the further benefits of a simpler tax system, with cost savings for both administration and compliance. The risk here is that allowing one leaky tax provision might spawn others. The choice of policy response will also hinge, technically and politically, on whether the particular tax-avoidance practice has exceeded some critical threshold.

Gender equity clearly is a relevant criterion for assessing income-splitting proposals, since splitting involves the tax treatment of women as spouses and cohabitants rather than as single individuals.21 Although not conventionally viewed in this way, gender equity can be regarded as analogous to the horizontal equity concept. Horizontal equity entails equal treatment of equals, but it also allows for situations where individuals do not possess the same tastes, needs or opportunities. Similarly, most formulations of gender equity also contain both a formal and a substantive dimension of equality (for official sources, see Canada 1998, 3; 2003, 8-9; 2006a, 13). For formal equality, public policy should treat women the same as men as long as their situations do not differ in “relevant respects.” For substantive equality, policy should recognize the different needs of women and men in overcoming barriers to equality of opportunity, such as institutional, cultural and biological factors that affect women’s educational, occupational and work/domestic/parental opportunities; their employment, training and promotion prospects; and their full equality and individual autonomy in conjugal relationships. That is, differential treatment is sometimes justified to provide women the same realworld opportunities as men to realize their full potential. This is similar to the adjustments for differing needs, tastes and opportunities in applying the conventional horizontal equity concept.

Gender equity is properly concerned with the opportunities and well-being of all women, but many proponents of gender equity stress the barriers to full equality faced by the most vulnerable groups. These include women with lower education, skills and earnings as well as visible minorities, single parents and the disabled. Proponents of gender equity argue that income splitting would do nothing for single women or for those who are part of a lower-income couple, since splitting requires the presence of two partners, at least one of whom earns above the bottom rate bracket ($37,178 for federal tax purposes in 2007). From this perspective, income splitting could never be desirable since it would benefit some married women at higher incomes but do nothing for those who are most needy. However, that is a very limited view of gender equity. A broader conception would have room for policies that augment fairness for women at middle and higher incomes as well as for needier women. No one policy can achieve both goals, and assorted measures in the tax, expenditure and regulatory realms are needed to address gender equity for women in diverse situations.

Vertical equity relates to the distribution of economic resources, the benefits of public spending and the burden of taxes across income classes. The optimal degree of vertical equity reflects both objective evidence on behavioural effects, such as incentives, and value judgments about inequality. Both gender-based analyses and “progressive” policy analyses often accord a higher priority to vertical equity than to horizontal equity. In a logical sense, though, horizontal equity must come prior to vertical equity, since horizontal equity concepts guide the metric for measuring relative real incomes of individuals, without which vertical equity is nonoperational. If a policy that brings greater horizontal equity to individuals at higher incomes also happens to worsen vertical equity, the ideal response is to pursue horizontal equity and to adjust the benefit or tax rate schedule to restore the desired degree of vertical equity. If the latter step is deemed to be politically infeasible, then a conflict can arise between the two types of equity. This conflict can be resolved only by reference to judgments about the prospective gains to fairness in the horizontal equity sense relative to the associated losses to fairness in the vertical equity sense.

Tax law scholars have used two different approaches in assessing the fairness of taxing couples: the “control” approach and the “benefit” approach.22 Under the control approach, the individual who earns the income or has accumulated savings is the one who should bear the tax, so that spouses should be taxed individually, and the income on assets transferred from one spouse to the other should be attributed to the transferor. Under the benefit approach, the tax system would recognize the sharing of material resources within the family, which would justify some form of joint taxation of couples or income splitting. Unlike the benefit approach, the control approach — in common with the gender equity approach — is concerned with which spouse has effective control over the use of a couple’s economic resources.

Both control and benefit approaches, however, are difficult concepts to translate into observable criteria that tax authorities can use in the operation of a real-world tax system (see Head 1996, 201-2). Couples vary widely in their control of resources and in how they share the benefits of their combined resources; I present evidence of these varying patterns later in the study.23 For now, the key point is that tax policy cannot assume either that a couple’s joint resources are fully shared or that the spouse who earns the income or has legal title to an asset exerts full control without influence by the other spouse. Moreover, the Canadian personal “income” tax is, in fact, much closer to a tax on consumption, since it exempts or taxes lightly most savings and capital income for the overwhelming majority of taxpayers, and therefore is more attuned to a benefit approach to the well-being of couples.24 As a result of these crosscutting considerations, neither the control nor the benefit approach is decisive in the choice of tax unit, even if each can usefully inform the discussion.

In addition to the horizontal, vertical and gender concepts of equity, we need to understand the mechanics and properties underlying the choice of tax unit in order to assess income splitting. The alternatives for defining the tax unit for the members of a couple are:

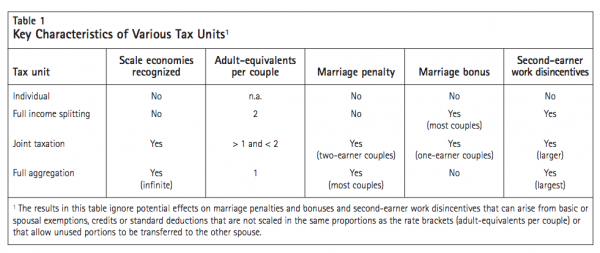

Other issues related to the tax unit include combined versus separate filing of tax returns and provisions for the transfer between spouses of various tax benefits.25 Table 1 summarizes the key properties of the various choices of tax unit, which I next examine in detail.

The simplest approach is to treat all taxpayers as individuals and subject them to the same tax rate schedule based on their own incomes. This approach regards everyone as an autonomous individual and his or her marital relationship as irrelevant for tax purposes. Individual taxation is the most common approach within member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), most of which recognize marital status only to the extent that one spouse’s income falls below the taxable threshold. With a progressive tax rate schedule, individual taxation means that the two spouses’ total tax liability depends not only on their total income but also on how that income is divided between them. Since they are taxed individually, each spouse’s marginal tax rate and related incentives are unaffected by the other’s income level. In contrast, income-splitting and joint taxation systems confront the lower-earning spouse with a higher marginal tax rate based on the couple’s joint earnings, which can pose disincentives for the lower earner (usually the woman) to enter the labour force or work more paid hours. Conversely, individual taxation provides spouses with divergent incomes and marginal tax rates an incentive to shift income to the lower-earning spouse, which the tax system requires special provisions to thwart.

Alternatively, couples can be taxed as two individuals who fully share their incomes. As tax analyst Joseph Pechman has stated, “[t]he classic argument in favor of income splitting is that husbands and wives usually share their combined income equally…[T]he tax liabilities of married couples should be computed as if they were two single persons with their total income divided equally between them” (1987, 103). Technically, this could be accomplished in either of two ways: (1) by using the same tax rate schedule as for single individuals and allowing the spouses to shift incomes between them until they are equalized; or (2) by providing couples with a special tax rate schedule for their combined income, but with the level of exemptions and all tax rate brackets twice as large as in the individual rate schedule.26 The former approach could apply mandatory splitting or allow the couple to choose how much income to shift notionally for tax purposes. Unless there were interactions with other tax or benefit provisions, the spouses would normally choose to shift at least enough income to put them both in the same marginal tax bracket. This choice would yield them the same tax savings as full splitting — that is, shifting to the point that their taxable incomes were equalized.

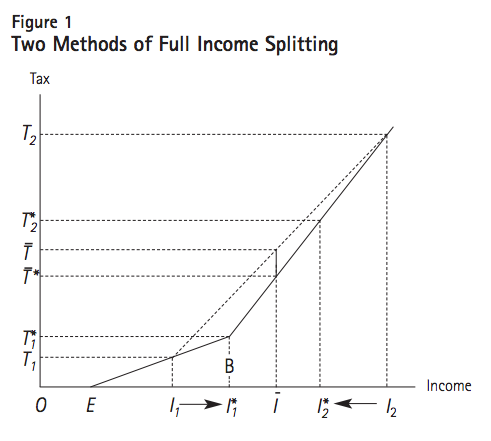

These and other properties can be illustrated graphically for general income splitting — where all types of incomes can be shifted or fully split. For simplicity, I assume that the rate schedule for all taxpayers has just two positive marginal rate brackets above an exempt level (E), although the results could easily be generalized to Canada’s federal schedule of four rate brackets. I also assume that the higher-income spouse’s income (I2) is further removed from the boundary between the two tax brackets (B) than the lower-income spouse’s income (I1). Figure 1 shows the respective taxes on the two spouses, T1 and T2, in the absence of splitting.

Their average tax burden (T) arises at their average income (I), at the midpoint of the dotted line connecting the points of their original tax levels.

If the spouses were given the option of splitting by shifting part of their incomes, they clearly would shift income from the higher to the lower earner. To minimize total taxes, the couple would shift at least enough to bring the income of spouse 1 up to I1 andthat of spouse 2 down to I2. The couple’s resulting average taxes would thereby be reduced to T*, with average savings per spouse of T — T* (the solid vertical line at I). Twice that amount is the couple’s total tax savings relative to the nonsplitting case, which is called a marriage bonus.

Alternatively, a special tax schedule could apply to the couple whereby all brackets are twice as wide as for a single taxpayer. This can be viewed in figure 1 as equivalent to requiring the two spouses to average their incomes and using the singles’ rate schedule. That would yield an average income for each spouse of I and the same total taxes per couple as the spouses would face if they could choose how much income to shift.27 Hence, with full splitting, the results would be the same whether couples were allowed to choose how much income to shift or were required to split their total income equally.

In the illustrated situation, with the higher-income spouse further from the bracket boundary than the lower-income spouse, income splitting raises the lower earner’s marginal tax rate and leaves that of the higher earner unchanged. In the converse situation, splitting could reduce the higher earner’s marginal rate and leave the lower earner’s rate unchanged. If both spouses’ incomes placed them in the same tax bracket, however, there would be no gain from splitting and no effect on the marginal tax rate either spouse would face. With more than two tax brackets, splitting might even increase the lower earner’s marginal rate and decrease the higher earner’s rate. Moreover, with multiple brackets and many couples with substantially divergent incomes, the marginal tax rate on the lower-earning spouse is more likely to increase. In no situation would splitting decrease the lower earner’s marginal tax rate; it could only increase the rate or leave it unchanged.28

Of the two cited methods for income splitting, only the shifting method would be feasible if splitting were limited to certain types of incomes, such as pensions. In the case of the restricted splitting that the tax system now permits, the logic also differs substantially. Now, the benefits of splitting hinge on which spouse has most of the income type that can be split. If that is the lower-income spouse, the couple might gain little benefit from splitting any of the eligible income even if the two spouses are in very different tax brackets; if a 50:50 mandatory split were imposed, the couple would suffer a penalty. And if the income that can be split belongs to the higher-income spouse, splitting might no longer put the two spouses in the same tax bracket if their other types of income are large relative to the income that can be split.

The full-income-splitting approach has several notable attributes. First, as Pechman notes, it assumes that the spouses fully share their individual incomes for common consumption purposes (1987). Second, while treating the couple as a sharing entity, it completely ignores the scale economies of living together. Third, with this approach to taxing couples there is no need to measure or track the separate incomes of the spouses. Fourth, full income splitting yields tax savings only when, and to the degree to which, the spouses’ own incomes place them in different marginal tax brackets under the individual rate schedule. Fifth, this approach to incomes splitting could produce only tax bonuses for marriage (or other recognized forms of union); it could never produce tax penalties. Finally, for most couples who would benefit from full splitting, the lower-earning spouse would face a higher marginal tax rate than would arise under individual taxation, which could exert adverse effects on labour force entry, work hours and economic efficiency. I examine these important issues in more detail later in the paper.

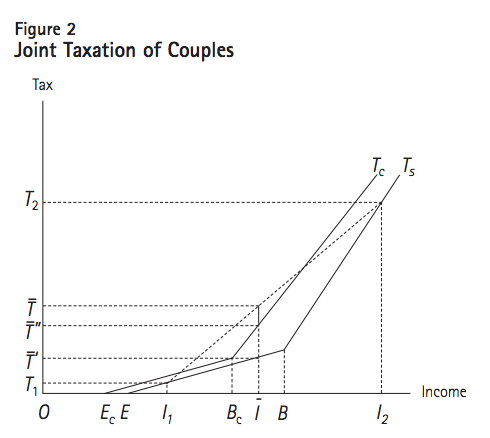

Joint taxation is a more general form of income splitting that taxes the couple’s combined income using a rate schedule reflecting the scale economies a couple enjoys. The tax rate brackets are less than twice as wide as those for individual taxes — such as the 1.5 ratio suggested earlier as the number of adult-equivalents for a couple. Joint taxation shares all the other attributes described above for full income splitting, with the notable exception that it can produce marriage tax penalties as well as marriage tax bonuses relative to individual-based taxation. If the two spouses have identical or very similar individual incomes, they would gain little or nothing from the splitting feature, but joint taxation’s recognition of their scale economies would mean they would be taxed more heavily than if they were not together. Couples with large tax savings from the splitting feature would have their savings partially offset by the recognition of their scale economies.

Figure 2 illustrates these effects of joint taxation of couples. This time, I distinguish between the tax schedule facing singles (Ts) and a schedule used to assess couples (Tc). Schedule Tc is presented as half the actual schedule for joint married filers and applies to half their combined income.29 Assuming 1.5 adult-equivalents per couple, the exempt level (Ec ) and tax-bracket boundary (Bc ) are each three-quarters their size in the singles’ schedule. Consider a couple in which each spouse has the same income I. Each pays taxes of T“ (on the T schedule), whereas each would pay only T’ (on the T s schedule) as a single. The difference, T “ — T ’, is the marriage penalty tax for each of the equal-earning spouses; the total marriage penalty for the couple is twice that amount.

Now consider a couple in which the spouses have divergent incomes of I1 and I2. If they were unrelated, their tax burdens (on the Ts schedule) would be T1 and T2, respectively, and their average taxes would be T (at the midpoint, or average income of I, on the dashed line connecting their individual tax liabilities). As a couple, the two individuals could combine or average their incomes using schedule Tc. This would yield a tax of T“ per spouse, which is less than the average taxes of T those individuals would pay if they were unrelated. The resulting tax savings per spouse, T — T“ (the solid vertical line at I), reflects the gains from income splitting offset in part by the scale economies in the joint rate schedule. Twice this amount is the couple’s marriage bonus. If the spouses’ incomes diverged but by not too much, they could still incur a marriage penalty.

To sum up, joint taxation of couples has great similarities to full income splitting; in fact, it is a more general case of splitting that recognizes the scale economies couples enjoy. As a result, joint taxation would provide couples less tax savings than full income splitting, and it would increase taxes on couples with spouses who have identical or not too divergent incomes. Hence, joint taxation produces marriage penalties as well as marriage bonuses. The bottom line in fiscal terms is that joint taxation would be considerably less costly than full splitting. If splitting were restricted to particular types of income, joint taxation would not be appropriate since it would apply a modified tax schedule to the couple’s entire income from all sources. Even with restricted splitting, however, one could contemplate introducing a device to account for the couple’s scale economies with respect to the income that can be split.

Full income splitting is one polar case of the joint taxation of couples, in which couples are assumed to enjoy no scale economies relative to singles. At the other extreme is full aggregation of couples’ incomes using the singles’ tax rate schedule, which assumes that couples’ economies are infinite. That is, full aggregation assumes that “two can live as cheaply as one,” in effect deeming a couple to contain only 1.0 adult-equivalents. While full aggregation might not have much appeal today, some European countries once used this system (Ireland, before 1980; the United Kingdom, at least until 1971), and it was proposed as a reform to the US system in the 1940s, before that country’s move to full income splitting in 1948. Full splitting can produce only marriage bonuses, while full aggregation can produce only marriage penalties. All systems for taxing couples other than individual taxation can produce disincentives for paid work by raising tax burdens on labour force entry and extra earnings by the second earner, most often the wife.

Whether couples should be taxed on an individual, fully split, joint or fully aggregated basis is a logically distinct issue from whether spouses should be required to submit separate or combined tax returns. Some Canadian advocates of income splitting contemplate continued individual filing of returns but would give spouses the option to shift part of their income from the higher to the lower earner. More typically, countries that tax couples on a fully split or joint basis require the filing of a joint return that combines the reporting of the spouses’ income receipts. Common jargon for this practice is “joint filing,” but here I wish to distinguish clearly between forms of joint taxation (including the full-splitting and aggregation cases) and combined or separate filing of returns.

With joint taxation, several considerations arise in the policy choice between combined and separate filing. With combined filing

On the other hand, separate filing

Similar considerations also affect the choice between individual taxation, which typically entails separate filing by spouses,30 and various forms of joint taxation.

Almost all systems for the individual taxation of couples provide for the transfer of basic tax exemptions, allowances, deductions and/or credits. Typically, this arises when the lower-earning spouse cannot fully use the provision to offset his or her own taxes and transfers the unused portion to reduce the tax liability of the higher-earning spouse. Such transferability constitutes a form of “jointness” in the taxation of couples but differs considerably from the ability to transfer or shift income to the spouse.31 In small measure, transferability recognizes the additional living costs of a couple relative to those of a single person, but it affords relatively little relief compared with most variants of joint taxation for one-earner couples, especially at median and higher incomes. Nevertheless, these provisions do engage issues arising for the choice of the tax unit, which I later discuss for Canada’s spousal and equivalent tax credit.

In this section, I provide an overview of past and present practices in the tax treatment of couples in the United States — the most important tax comparator for Canada and a country where the taxunit issue has been extensively debated and assessed. I also briefly describe the diverse methods used for taxing couples in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Spain and France. This institutional material offers valuable background for understanding my subsequent analysis of the equity and other properties of tax splitting for the three types of income. Almost all the issues for the tax treatment of couples in Canada have been confronted and addressed, one way or another, in foreign policies.

The United States offers an essential case study for the taxation of married couples. From its inception in 1913, the US income tax has traversed a tortuous course from the original system of individual taxation to the adoption of full income splitting in 1948 and subsequent reforms that reduced splitting to joint taxation and later restored full splitting only for low to middle-income earners.32 Here, I deal solely with the rate schedule and income-splitting aspects of the tax unit; I do not address other US tax provisions33 or transfer programs34 that also affect marriage penalties. The US experience is rich in both legal and economic studies on the tax treatment of couples, from which valuable policy guidance can be drawn. Even more instructive is the political lesson that initiating income splitting opens a Pandora’s box of interminable controversy over the equitable tax treatment of various family types.

At the outset, all US taxpayers, whether single or married, filed an individual return using a common rate schedule. Couples also had the option of filing a combined return using the full-aggregation method with the same rate schedule as singles; this allowed one-earner couples to access the personal exemption for both spouses. With the rising tax rates of the First World War, however, some couples residing in the eight community-property states of the Southwest and the Pacific Coast began filing separate returns in which each spouse claimed half the couple’s combined income. This “self-help” income splitting was justified by those states’ legal provisions deeming both labour earnings and investment income vested half in each spouse. The practice was challenged by the Congress and the Treasury Department but ultimately was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1930. Couples in the common-law states also sought to achieve income splitting by placing income-producing properties in joint tenancies or family trusts and by converting business proprietorships into corporations or family partnerships.35 Those manoeuvres often did not succeed legally, so that from 1939 to 1947 several of those states switched to community-property regimes to assist their residents in reducing their federal tax burdens. Since the gains to splitting for one-earner couples, the norm in that period, rose with tax rates, the mounting tax revenues needed to finance the Second World War compounded all of these pressures.36

Members of Congress were hard-pressed to respond to the growing horizontal inequities in tax burdens for couples, both among states with different property regimes and between couples with income from labour earnings as opposed to income from property and investments. In 1941, in an attempt to override the community-property states, the Treasury Department persuaded the House Committee on Ways and Means to advance a bill for mandatory joint filing with full aggregation by all married couples, using the same rate schedule as for single persons. This bill was attacked as “a tax on morality” for encouraging unmarried cohabitation and divorce and failed to gain political support.37 The ultimate resolution, in 1948, was a reform that permitted all married couples to file a joint return with full income splitting, in effect validating what the shift to community-property regimes was achieving.38 Congress passed this “far-reaching change in the income taxation of the family” and sustained it over a presidential veto (Surrey 1948, 1105). Married taxpayers filing a joint return computed the tax on one-half of their combined income, using the same rate schedule as for individual filers, and this figure was doubled to obtain their total tax liability.39 As my earlier analysis of full income splitting showed, this system could create only marriage tax bonuses, and bonuses were far more common than no changes in tax liability because of the rarity of equal-earning spouses at that time.

No sooner had the United States introduced full income splitting than critics observed the new system’s tax penalties for single individuals. By its nature, full splitting implied that a single individual would pay substantially more tax than a married couple with the same income; this point was most salient when the couple’s income derived entirely from one earner. The first legislative response addressed the situation of unmarried individuals who had financial responsibility for dependants by using the same treatment as that accorded to a married individual with a dependent spouse. In 1951, a new tax rate schedule was introduced for “heads of households,” a category that initially covered single taxpayers who were supporting one or more dependent children; the schedule was extended in 1954 to include support of dependent parents. The head-of-household rate schedule roughly split the difference between the tax burden on single individuals and that on married couples at the same income levels.

With time, criticism also arose over the tax penalties for single individuals without any dependants. This included the growing numbers of unattached individuals plus unmarried cohabiting couples who in most states lacked the status of a common-law marriage.40 These individuals could face a tax burden as much as 42 percent higher than that of a married couple with the same income. Congress eventually responded, in 1969, with another major rejuggling of the tax system that increased the number of rate schedules from two to four. Becoming effective in 1971, the new provisions reduced the basic tax rate schedule used by all filers other than heads of households so that the singles’ tax penalty could never exceed 20 percent of taxes paid by a married couple with the same income.41 Simultaneously, it reformulated the existing rate schedule by doubling the tax-bracket widths for use solely by married couples and applying them to the spouses’ combined income; this simplified their tax computations but left their tax burden unchanged. Married couples could not use the new, lower singles’ rate schedule but could opt for filing separately under the original but less advantageous rate schedule. In that way, Congress forestalled the ability of couples in community-property states to access the singles’ lower rate schedule and secure differential tax relief compared with couples elsewhere.

By preventing couples from using the singles’ rate schedule, the 1969 reform both reduced marriage bonuses and, for spouses with incomes not too divergent, created marriage penalties. Two-earner couples faced a marriage penalty when their incomes were more evenly divided than 20:80.42 Given the predominance of one-earner couples, however, marriage bonuses were much more frequent and in aggregate much larger than marriage penalties during this period. Even 10 years after the reform, the Treasury Department reported that marriage penalties constituted US$8.3 billion on 16 million joint returns, while marriage bonuses constituted US$19 billion on 24 million joint returns (Gann 1980, 22-3). In the ensuing years, with the ongoing rapid rise in married women’s labour force participation and growth in their relative earnings, the balance was destined to tilt much more toward marriage penalties and away from marriage bonuses. The measurement and assessment of marriage tax penalties and bonuses became a veritable cottage industry for US tax policy analysts.43 Additionally, the adverse effects of joint taxation on wives’ work incentives attracted increasing scrutiny.

To address both marital bias and work incentive issues, a bill was introduced in Congress in 1974 to revert to individual taxation with a single rate schedule for all taxpayers. Despite its being sponsored by a politically diverse group of more than 150 congressmen and senators, the bill failed passage. In 1981, a provision for a second-earner deduction was approved to permit a married couple’s lower earner to deduct 10 percent of earnings up to US$30,000 per year beginning in 1983 (5 percent in 1982). The second-earner deduction provided substantial but incomplete moderation of both marriage penalties and work disincentives for two-earner married couples.44

Although it enlarged marriage bonuses, it left the wife’s marginal tax rate tied to her husband’s income and did not relieve marriage penalties resulting from nonlabour income. The deduction was repealed in the sweeping 1986 tax reform, whose sharp rate cutting and bracket broadening directly moderated those problems but did not eliminate them.

Marriage penalties and work disincentives for married women grew again in 1993 with the Clinton administration’s income tax hikes for higher earners. These issues continued to attract political heat through the decade and, in the 2000 election campaign, the Republicans promised to address them. As of the 2000 tax year, the married joint rate schedule had an adult-equivalence scale for couples of 1.67 for the bottom two tax brackets, applying up to a combined income of US$105,950. For couples with higher incomes, the brackets’ implied adult-equivalent values were much smaller, so that the single and married joint rate schedules both reached the top marginal rate of 39.6 percent at an income of US$288,350. With the Bush administration’s tax cuts of 2001 and 2003, the married joint brackets were expanded to restore full splitting for low-to upper-middle-income couples; as of 2007, couples enjoy full income splitting for combined income up to US$128,500.45 For couples with higher income levels, marriage penalties still exist. Doubtless, the cycle will turn once again, with pressures for reform likely centring on the growing singles’ tax penalty. As one prescient observer, an advocate of individual taxation, remarked in 1980, “legislative attempts to determine the appropriate relative tax burdens of single and married persons will continue to be what they have been: temporary, uneasy compromises that must yield to ever-changing legislative modifications passed in response to taxpayers’ complaints” (Gann 1980, 3).46

Earlier analysts of the tax unit in the United States formed a near-consensus on the propriety of using the couple or family. In 1947, noted economist and future Nobel laureate William Vickrey wrote: “it is neither possible nor, in fact, desirable to attempt to consider each individual as an independent unit for tax purposes” (274). This view was later echoed by Groves, who stated that “[s]tudents of public finance with few exceptions regard the family rather than the individual as the proper unit for income taxation” (1963, 62). In an influential 1975 article, tax law scholar Boris Bittker acknowledged the advantages of separate filing by spouses but was unwilling to forego the principle of equal taxes for couples with equal total incomes.

Scholarly thinking on this issue has changed sharply over time, driven by major shifts in US demographic and economic patterns — rising labour force participation rates of married women, the increasing incidence of divorce and growing numbers of unmarried couples, single parents and other nontraditional family units. In 1977, economist Harvey Rosen stated that “if joint filing were eliminated, the federal income tax would become both more equitable and more efficient” (423). In subsequent years, support for individual taxation in the United States has swelled across a broad range of analysts.47 Even conservative analysts, who tend to be most favourable to using the couple as the tax unit, have identified deficiencies in the existing US tax treatment of couples. Their solutions include adopting a flat rate income tax, replacing the income tax with a national sales tax and giving spouses the option of filing individual tax returns or joint returns (Bartlett 1998; Strassel, Colgan and Goodman 2006).48

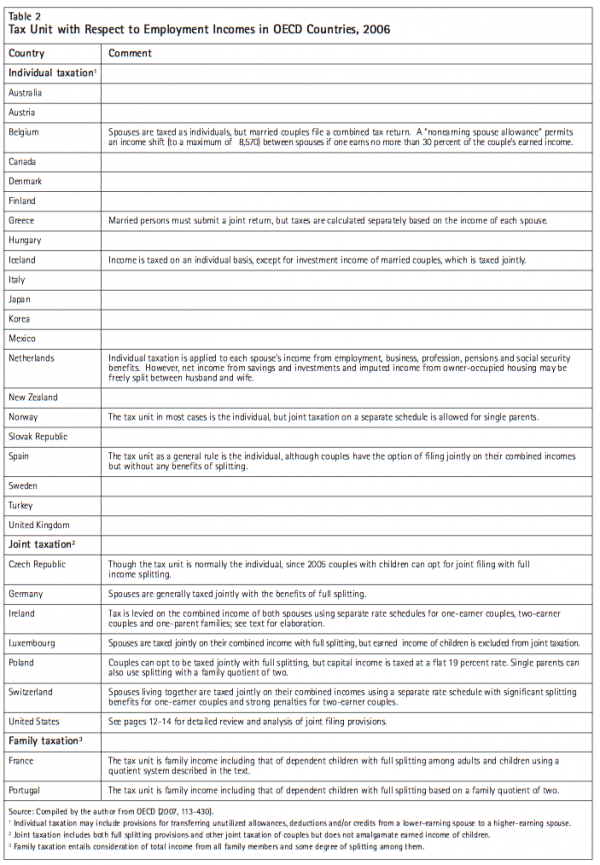

The tax systems of the 30 member countries of the OECD are the most comprehensively documented in the world. Table 2, which groups those systems according to how they define the tax unit with respect to employment income,49 clearly shows that individual taxation of couples is the predominant approach. Moreover, the trend since 1970 has been to move from various forms of joint taxation to individual taxation, as has occurred in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom (OECD 1993). Ireland’s tax system, while still classified as joint, has also moved toward lesser jointness in the taxation of couples. Gender equity has been an important policy consideration in many countries that have moved closer to individual taxation.50

Several OECD countries that apply individual taxation to income from employment use special forms of joint taxation for self-employment and/or investment income. In the Netherlands (and previously Belgium), investment income is assessed to the spouse with the higher earned income. The Netherlands and Belgium also permit a portion of self-employment income to be attributed to a “helping spouse.” Denmark attributes investment income over a specified threshold as taxable income to the higher-earning spouse (O’Donoghue and Sutherland 1999, 574). In 1991, Sweden adopted a dual tax that combines progressive rates on labour income with a flat rate of tax (equal to the corporate income tax rate) on investment income; Norway and Finland adopted similar schemes in the following two years (Sørensen 2007, 563).51 Since moving from joint to individual taxation in 1990, the United Kingdom has allowed couples to shift investment income between spouses to minimize their tax burdens, as I detail later.

Since its inception, Ireland’s income tax system has applied three different methods of taxing couples (see Callan 2006; OECD 2007). From 1922 to 1979, the method was to aggregate spouses’ incomes but to offer no splitting benefits in the rate schedule — the same as that used for single taxpayers — although there was a “married man’s allowance.” A legal case in the 1970s attacked the resulting “marriage penalty” for two-earner couples on constitutional grounds and led to the adoption of full income splitting for couples in 1980. Over time, income splitting came to be seen as providing large benefits to many families not engaged in child care and no benefits to many families with heavy child care burdens. As analysts noted, full income splitting was an inefficient way to target fiscal resources at child care undertaken by married women in the home. In 2000, the system was modified toward a more “individualized” system with limited splitting; this greatly reduced the extent to which the benefits of the standard tax rate bracket were transferable when one spouse had low or no earnings.52

At one time, the United Kingdom used the aggregation method, under which the wife’s income was added to the husband’s and taxed on his return.53 There was also a “married man’s allowance” and a “wife’s earned income allowance,” the latter similar to the second-earner deduction once provided in the United States. In 1971, the UK introduced a “wife’s earnings election” that allowed a married woman to be taxed as a single person on her own labour earnings, but both spouses had to choose this option and the husband had to forego the married man’s allowance. In 1990 came a major switch to the individual taxation of couples, offering great flexibility in splitting investment income by transfers of assets between spouses. Such transfers could be made either as a gift (which incurs no capital gains tax) or by holding assets jointly with an option to divide the asset holding and associated income flow in any desired proportions.54

Belgium’s system is essentially the individual taxation of married couples (although they file joint returns), an approach that reflects reforms implemented between 2002 and 2004.55 Prior to 1988, Belgium used the full-aggregation method for married couples. Dual-earner unmarried couples were not required to aggregate their incomes, so that the system created a steep marriage penalty for dual-earner couples. In 1988, the system changed to individual taxation, with a special provision for lower-earning spouses with earnings less than 30 percent of the couple’s combined earned income; this provision also applies to one-earner couples. This “nonearning spouse allowance” allows a notional transfer to the lower earner of up to 30 percent of the couple’s aggregate earned income, less the lower earner’s earnings and in 2006 subject to a 8,570 limit. This limited provision for splitting is akin to other countries’ provisions for transferability of a spousal allowance.

In Spain, the basic unit for taxation is the individual. Married couples can opt for either separate filing by spouses as individuals or joint filing as a couple on their combined income. Currently, married couples who file jointly face the same rate schedule as single filers, so that their only gain is the exempt amount for a nonearner spouse, similar to Canada’s provision for transferability of unused marital credits. In earlier years, however, many couples found joint taxation more attractive because it offered a separate tax rate schedule with partial income splitting.56 The previous scheme constituted a variant of taxation of couples that differs from both full splitting (where only marriage bonuses can arise) and conventional joint taxation (where both marriage bonuses and marriage penalties arise). Spain’s earlier scheme allowed only the limited splitting of joint taxation but also avoided marriage penalties.

France offers an interesting variant on income splitting whereby the number of children as well as adults affects the splitting calculation.57 Its “family quotient” (quotient familial) system divides a family’s total taxable income by a quotient that depends on marital status and the number of children.58 This “split” income is then used to calculate tax with a standard rate schedule, and the family’s total tax is the computed tax multiplied by its quotient. The quotient for couples is 2 (1 for each adult) plus 0.5 for each of the first two children and an additional 1 for each of the third and further children. For a single-parent family, the first child obtains a quotient of 1. The maximum tax reduction from the child part of the quotient in a two-parent family is limited; in 2005, the limit was 2,159 per half-quotient.

From its inception as the Income War Tax Act of 1917, Canada’s income tax system has always used the individual as the tax unit, with the same rate schedule for everyone, whether single or married. Initially, the finance minister of the day proposed to give all individuals the same personal exemption level irrespective of marital status or presence of a dependent spouse. This proposal was attacked in parliamentary debates as an unfair benefit to single men and “spinsters,” who would be taxed relatively “too lightly” (Lahey 2000, 1-2). In the end, the 1917 legislation provided tax exemptions for one-earner couples that were double those for single filers. A variant of this tax provision offering linkage between spouses has survived to this day — as a marital exemption through 1987 and since 1988 as a nonrefundable spousal tax credit. This provision, which operates only when one spouse has income below the taxable level, is now called the “spouse and equivalent-to-spouse tax credit” and is also available to single parents.

An interesting Canadian contrast to the US experience with community-property states arose in Quebec, which once had matrimonial property laws similarly derived from French law (Dulude 1985, 82). Under the standard Quebec regime, the spouses were nominally equal partners in their combined property, even though the husband typically wielded effective control. However, high-income Quebecers usually opted out of the community-property regime through prenuptial agreements, so that attempts at income splitting for tax purposes were not common. Then, in 1957, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in the Sura case that spouses under the community-property regime could not each declare half of their combined income for tax purposes, arguing that the wife did not “have the exercise of the plenitude of rights which ownership normally confers…[T]he result is that the wife receives no income from community property,” so that the income could not be split to reduce the couple’s total tax burden.59

The most focused early assessment of Canada’s taxation of couples was that of the Carter Commission (Canada 1966). The commission assumed that the appropriate unit for taxation was the family, not the individual, and it cited the administrative and compliance gains from not having to attribute investment incomes to each spouse in order to contain tax-motivated shifting. It recommended a system of joint taxation of couples that allowed for both income splitting and recognition of the scale economies enjoyed by families. The commission’s proposed system entailed a different rate schedule for married couples than for individuals. The government of the day rejected this component of the commission’s report, however, on the grounds that it imposed a tax on marriage and a barrier to the wife’s participation in the paid workforce by confronting her with the husband’s marginal tax rate (Canada 1969, 15).60 Those concerns have recurred in subsequent research on income splitting, particularly with respect to labour income. Joint taxation under an elective scheme was supported by Canada’s Royal Commission on the Status of Women in 1970, but was officially rejected.

Further interest in joint taxation for couples in Canada arose in the mid-1970s with the federal Interdepartmental Committee on the Taxation of Women.61 Some committee members, led by those from the Department of National Revenue, supported joint taxation on the grounds of equity and administrative simplicity; other members opposed it on the grounds of its marriage penalty and work disincentives for wives. The latter group predominated, its views captured by the federal coordinator for the status of women:

Joint returns are an idea whose time has passed. During the 1950s and ’60s when most wives worked in the home, it would perhaps have been a better tax system than individual returns. In the 1970s, however, when government is making such efforts to improve the status of women by recognizing them as individuals outside the family unit, it would seem a retrograde step. (Quoted in Dulude 1985, 84-5)

The next hint of a policy change in the taxation of couples came in 1983, when the Minister Responsible for the Status of Women proposed to abolish the spousal exemption and use the funds to enhance child care — putatively the first step toward joint filing. Public backlash was quick and severe, suggesting concerns that the proposal failed to value women’s nonmarket work (Lahey 2000, 43-4). Then, after a relatively dormant period, political and scholarly interest in the issue of how to tax couples was renewed in the latter 1990s.62 Research published by Canadian think tanks from a wide range of perspectives has almost uniformly found individual taxation to be most appropriate.63 Outliers in this body of research are studies by the Fraser Institute; for example, Veldhuis and Clemens assert that the Canadian “tax system is biased…against single income families,” but their preferred solution is a flat tax rather than income splitting (2004, 11-12).64 Recent popular support for general income splitting has come predominantly from “family values” and faith-based advocacy groups.65

Opposite-sex common-law partners and same-sex partners cohabiting for more than one year have been treated the same as married couples for tax purposes since 1993 and 2000, respectively. In addition to the spousal or equivalent credit, tax credits for charitable donations and medical expenses can be amalgamated between spouses in a way that is often favourable relative to single taxpayers (because thresholds for credits or credits at a higher rate need to be satisfied only once for the spouses jointly). Various nonrefundable tax credits not used by a nontaxable spouse can be transferred for use by the taxable spouse. Canada’s tax system also contains provisions that can operate against couples, such as the exemption of capital gains on a single principal residence for couples. Indeed, Lahey reports that the tax system has “some 100 provisions” in which marital status affects tax liabilities (2005, 33). The system seeks to apply tax to the individual incomes of spouses with rules to restrict income splitting, although sizable options for splitting exist, especially for savings and investment income, as I discuss later.

In the 2006 tax year, the spousal tax credit was a maximum of $7,505, while the basic personal credit was $8,839, which each filer with income above the taxable threshold could claim.66 A low-earning spouse generated a spousal credit amount for the higherearning spouse equal to $8,256, less his or her net income up to a maximum of $7,505.67 In effect, the lower earner could earn an initial $751 (that is, $8,256 minus $7,505) tax-free; any incremental earnings were deducted from the maximum amount and therefore faced the bottom marginal tax rate. This system for taxing couples, which is common in some variant to most countries that use individual taxation, poses a barrier to labour force entry and market earnings by a couple’s second worker, most often the wife. If spouses were taxed in a truly independent manner, each would be able to earn the full basic amount before facing any positive tax rate. However, the cited barrier for second earners is less severe than that arising under joint taxation; there, the initial earnings of the lower-earner would face the higher marginal tax rate of the primary earner.

For the 2007 tax year, the basic personal credit amount was indexed to rise to $8,929 and the 2007 federal budget raised the spousal tax credit to equal the basic personal credit amount. The finance minister asserted that he was “ending the marriage penalty for single-earner couples” by equating the two credit amounts (Canada 2007a, 13); most media coverage repeated the claim uncritically. Yet, the spousal credit provides a benefit to a couple for having a low or nil earner that would not arise if they were not married, since the credit is nonrefundable and can reduce the amount of tax owed only by the primary earner. Thus, it would be more correct to state that the budgetary initiative was “increasing the marriage bonus” for single-earner couples; it would be even more accurate to refer to the “marriage and cohabitation” bonus. With the raising of the spousal credit to the basic credit amount, all earnings of the lowerearning spouse now offset the spousal credit. That change has removed the tax-free range of initial earnings by the second earner, so that even the first dollar of earnings faces the bottom marginal tax rate. One could argue, however, that a lower spousal credit than basic credit is justified, given the scale economies that a couple enjoys relative to an individual. The fall 2007 federal economic statement boosted the basic and spousal credit amounts to $9,600 retroactively for the 2007 tax year and for 2008 (Canada 2007c).

Canada’s system of individual taxation aims to assess separately all the economic resources of each filer to ensure the application of progressive rates. Typically, labour earnings of employees (the largest income source) are not susceptible to splitting with the earner’s spouse for tax purposes. Nevertheless, for incomes derived from sources other than employment, significant opportunities for splitting exist within couples. Two types of labour earnings are prone to splitting. First, individuals with unincorporated self-employment income can hire their spouses and thereby divert some of their earnings for tax purposes, although the tax regulations require that such payments be reasonable relative to the work performed by the spouse and at a rate that would be made to an arm’s-length employee.68 Second, individuals with control over an incorporated business can similarly employ their spouse or alternatively divert their own returns to labour within the enterprise via dividend payments to their spouse as a shareholder. The tax authorities can contain only the more blatant abuses of excessive payments to spouses.

Greater income-splitting opportunities arise for Canadian couples in the areas of savings and associated investment income. Some of the more common methods are:69

All of these methods are fully legal and can yield large splitting benefits if pursued over an extended period. The latest addition to this list is the 2007 budget’s provision of pension income splitting for couples, which I describe in detail later.

Higher-wealth couples with different incomes often seek faster and larger income splitting through interspousal transfers of income-producing assets.

From its inception, Canadian income tax legislation has contained rules to attempt to thwart such splitting. These income attribution rules, which deem the income taxable to the transferor of the asset rather than to the transferee, have become more complex over the years through the accretion of legislative changes and court rulings. Nevertheless, one generation ago, an expert remarked, “[a]ny person with income from business or property, notwithstanding the attribution rules, is able to arrange his or her affairs so as to income split with family members” (London 1979, 7). Despite subsequent legislative tightening, most current observers would still find much truth in this statement. For example, income attribution rules are constrained in their application to the transfer of business interests as against financial assets. Among countries that use individual taxation, Canada is almost unique in the extent to which it seeks to curtail income splitting via asset transfers. Many analysts — including Donnelly, Magee and Young (2000); Young (2000); Philipps (2002); and Samtani (2006) — have critiqued the income attribution rules but with varying conclusions. I address this issue in my analyses of splitting for pension income and investment income.

As part of its Tax Fairness Plan announced in October 2006, the federal government allowed couples to split their pension-type incomes beginning with the 2007 tax year. Incomes eligible for the pension income credit can be split, but the precise types depend upon whether the transferor has attained age 65. Annuity payments from a Registered Pension Plan (RPP) can be split regardless of the transferor’s age. A spouse age 65 or over can also split annuity payments from an RRSP or Deferred Profit-Sharing Plan and payments from a Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF), locked-in RRIF (LRIF) or Life Income Fund (LIF).71 There is no age restriction for the spouse who receives the pension income allocation. A couple can jointly elect for a spouse to split up to one-half of his or her qualifying pension income with the other spouse; typically, these notional transfers will be from the higher-income to the lower-income spouse. Since nine provinces operate their income taxes using the federal definition of taxable income, pension income splitting will apply to them as well. While Quebec runs its tax system independently, it has introduced pension income splitting to parallel the federal provision.

At tax-filing time each year, a couple will have the option to engage in pension splitting. The chosen sum will be deductible to the spouse who makes the transfer and taxable to the other spouse. Therefore, both spouses must agree to the transfer. The amount transferred retains its character as income eligible for the pension income credit, so that where one spouse has little or no pension income the couple will now be able to tap the pension credit twice. Income splitting will usually be beneficial only when the spouse with the pension income to be split has larger taxable income and is in a higher marginal tax rate bracket. However, the split income can affect each spouse’s claim for the age tax credit and clawback of Old Age Security (OAS) payments, each of which is conditioned on the net income of the individual, not the couple.72 Therefore, many possible scenarios for splitting choices can arise depending on which spouse has more pension income, on the amount of each spouse’s nonpension income and on interactions with other provisions of the tax and benefit system. Some couples may even choose to transfer pension income from the lower-income to the higher-income spouse, where both were originally in the OAS clawback’s income range and one can be pushed above that range.73 Although the calculations are complex, taxpayers will easily optimize their choice at filing time with tax preparation software.

The horizontal equity concept has been central in support for pension income splitting. Prior to the Tax Fairness Plan, the advocacy group Canadian Activists for Pension Splitting74 argued:

We consider it unfair that some taxpayers are able to reduce their taxes by such means as spousal RRSPs or CPP splitting, while others do not have these available. Allowing splitting of all pensions would eliminate that unfairness. Our request is not merely another plea for a tax break. We consider this to be an issue of fairness, especially with respect to horizontal equity. (2006)

Spousal RRSPs are a major way for one-earner couples and spouses with divergent earnings to engage in tax splitting. Yet some workers — those with employers offering generous RPPs — have little or no access to RRSPs of any kind.75 In contrast, other workers with similar earnings — the self-employed, business proprietors and employees with little or no RPP savings through their employer — have large opportunities to split incomes via spousal RRSPs. That discrepancy clearly gives rise to horizontal inequity that could justify pension income splitting. The ability to have CPP/QPP retirement benefits split between spouses, in contrast, does not create horizontal inequity because those plans cover all kinds of employment, regardless of their RPP coverage, as well as self-employment.76

The new pension–income-splitting provisions will reduce substantially the incentives for using spousal RRSPs to split incomes. Some observers have even suggested that the spousal RRSP has become redundant. Yet, some circumstances will still favour couples who can access spousal RRSPs, such as:

To correct the remaining horizontal inequity, several measures could be considered. A minimal policy would be to attribute back to the contributor any withdrawals from spousal RRSPs until both spouses are at least age 60; this would eliminate the shortterm splitting advantage. A stronger policy would be to disallow any further contributions to spousal RRSPs.77 Yet, dismantling existing spousal RRSPs and merging them with the contributor’s own RRSP would be politically difficult, and many would deem it unfair in view of savers’ long planning horizons.