In September 1997, the Quebec government implemented a major reform of its family assistance programmes. This reform involved the creation of an Integrated Child Allowance to replace several financial assistance measures offered to families. With the implementation of the reforms, the government now provides direct financial support almost exclusively to low-income families. As compensation, the government undertook to assume the extra cost of new educational services and additional daycare places available at $5 per day. This reform radically changed the picture of government assistance to families: monetary assistance was reduced and applied more selectively, while assistance in the form of daycare services, universal in principle but largely benefiting families where both parents participate in the labour market, was increased.

It would be anticipated that a policy change of this importance would be supported by data and analyses that would contribute to an understanding of the nature and scope of the likely impact on different family types and, especially, on specifically targeted groups. However, at no time did the Quebec government publish any such research dealing with the consequences of this reallocation of benefits. This study aims to fill this void by providing thorough insight into various aspects of family assistance programmes in Quebec, both before and after the 1997 reforms.

The authors estimate that, compared with the pre-reform situation, 72 percent of families would receive less financial assistance from the provincial government in 1998 – findings in sharp contrast with the claim advanced by the Quebec Minister Responsible for Family Affairs that 95 percent of families would gain from these reforms. The families that gain from the reforms are those in the $10,000 to $25,000 income category. Families with middle or higher incomes are expected to pay for it. Large families and families with young children lose most under the new policy. Finally, families benefiting from social assistance neither gain nor lose, with the result that many children still grow up in poverty. Considering the Quebec government’s commitment to young children, these results are rather surprising.

A portion of the reduction of the direct financial assistance is being used to finance subsidized childcare services and the extension of educational services. However, the new services offered are not likely to compensate for the financial losses experienced by parents. Even though these measures can only have a positive impact on the development of young children, it is difficult to understand why child-care services are offered at the same price to all families, regardless of their income.

This paper also presents an alternative approach to government assistance for Quebec families, assuming the same funding levels from the federal and provincial governments. This approach involves the implementation of a nontaxable universal family allowance that grants a minimum equal social value to all children, whatever their parents’ income. Complementary measures such as work incentives, subsidized child-care services for lower and middle-income families and programmes specifically targeted at young children could also come into play. A universal allowance for the private cost of raising children reflects the importance that society attaches to children and the primary role that parents play in their education. The universal approach offers the undeniable advantage of being much simpler than the targeted approach. What’s more, it has the advantage of not passing any value judgment as to families’ lifestyle preferences since it provides the same financial assistance to families with one spouse at home as it does to those with both spouses working outside the home.

Issues relating to the future of family policy in Canada have received a great deal of attention from academia, governments and the media. Many analysts outside Quebec have concluded that the “Quebec Model” of family policy is the most ambitious and innovative in Canada and should form the basis of any new policy at either the federal or provincial level. Highlighted as a particularly significant achievement is the Quebec government’s decision to provide child care at a rate of $5 per day for all children aged two to four years irrespective of their parents’ income. This new government measure was accompanied by reduced and more selective monetary assistance to families. The new Integrated Child Allowance is targeted at low-income families and replaces several provisions that had previously been offered to all families.

Interestingly, the praise for the “Quebec Model” in the rest of Canada has come precisely at a time when recent analyses of the Quebec government’s initiatives have questioned whether or not families are actually better off financially under the new system. For instance, calculations by professor Claude Laferrière at the Université du Québec à Montréal show that families with an income of less than $32,000 were financially better off before the reforms when their payments of $20 per day for daycare services were eligible for federal and provincial income tax relief.

This Choices paper, originally published in 1997 by IRPP under the French title La politique familiale: ses impacts et les options, presents arguments that suggest that governments in the rest of Canada should not strive to emulate the “Quebec Model” too eagerly. At the time of its publication, this study had a marked impact on the policy debate in Quebec, even provoking a detailed public response from the Quebec Ministry Responsible for Family Affairs. We believe that this English version of the study will also make a useful and very timely contribution to the debate on family issues within the policy community across Canada.

The study, prepared by Robert Baril, a former research director at IRPP, and by Pierre Lefebvre and Philip Merrigan, professors of economics at l’Université du Québec à Montréal, provides great insight into various aspects of family assistance programmes, both before and after Quebec’s September 1997 reforms. The authors assessed the impact of provincial government programmes on the budget of Quebec families and estimated that, compared with the pre-reform situation, 72 percent of families would receive less financial assistance from the provincial government in 1998 — findings in sharp contrast with the claim advanced by the Quebec Minister Responsible for Family Affairs that 95 percent of families would gain from these reforms. The study also shows that the amounts allocated to families under Quebec’s family allowance programme are clearly inadequate in the fight against poverty: people receiving social assistance were allocated no additional benefits, and low-income families received no more than $60 per month in additional support.

Certainly, the authors endorse the government’s decision to invest more in child care, which they see as an essential element of any policy aimed at the development of young children. However, they strongly question the funding arrangements. In particular, they believe that the decision to offer all families, irrespective of income, access to daycare at a reduced rate was financially risky and is likely to lead to an increase in the overall cost of services as a result of wage parity demands and potential pressures in favour of unionization. The authors’ predictions were proven correct in the spring of 1999 when the Quebec government granted daycare educators a 35 percent increase in remuneration. This is not to say that the increase was not socially desirable but, from a fiscal point of view, it will exert considerable pressure on public resources as the promised number of places climbs to 200,000 by 2005. This commitment to daycare may become such a large financial obligation that it may eventually preclude any other efforts in family policy. In fact, in Quebec, every additional dollar coming from the federal National Child Benefit initiative will most likely have to be invested in the daycare programme.

Quebec’s new family programmes, with highly subsidized child-care services as their cornerstone, channel financial assistance primarily to families in which both parents work at regular 9-to-5 jobs and whose children are cared for in accredited centres. Supporting working parents is a worthy and necessary goal of a modern family policy. But family policy should be more neutral with regards to personal choices, provide more options to parents, and should not penalize those who do not follow a particular pattern. It would be more efficient to provide families with assistance that would not unduly influence their choices.

Considerations such as the long-term benefits of building women’s attachments to the workforce or the educational value of child care are often used as justifications for the Quebec approach. But if, for instance, the Quebec child-care programme does, in fact, aim to build female labour market attachment, it appears that the government is preaching to the converted by creating a subsidized daycare programme that supports even those educated professional women who already have a strong attachment to the labour market. Moreover, there is no strong evidence at this point in time that universal, subsidized daycare generates greater social and economic benefits than other possible government programmes aimed at the development of young children. Indeed, it is difficult to argue that the benefits generated by daycare services exceed those generated by parental care.

The Quebec government’s decision to provide universal child-care assistance (at least in prine ciple) but selective monetary assistance is questionable. There is a growing consensus that targeted programmes for children that focus primarily on the needs of lower-income families do not reach the majority of children in need. In fact, a high proportion of children who need assistance are not poor but come from middle-class families, as the middle class constitutes a larger segment of the population. As government officials all across Canada prepare to bring forth a new set of policies for children under the National Children’s Agenda, they must be mindful of the social and economic implications of the crucial policy choices they are making.

Carole Vincent

Research Director, IRPP

(This report has been translated from French.)

In September 1997, the Quebec government implemented a major reform of its family assistance programmes. The reform was significant in that it had implications for family policy as a whole. Direct financial assistance would henceforth be aimed almost exclusively at lowincome families, while indirect assistance, such as subsidized daycare services, would be offered gradually to all families in Quebec. In addition, the government was planning to create its own parental insurance programme. With the exception of this programme, the new initiatives were to be financed from within the same budgetary envelope that had been allocated to family policy programmes prior to the reforms. The government also opted to finance from within this same envelope the extension of access to pre-school to include part-time kindergarten for four-year-olds from disadvantaged backgrounds and full-time kindergarten for five-year-olds, at least for the first year of this programme.

With these reforms, it is clear that the government is pursuing several social policy objectives. Not only does it want to simplify government assistance to families and improve the accessibility of daycare services, it also wants to fight poverty, improve the incentive for work among low-income families and extend the school system to fourand five-year olds. To achieve these objectives, it has overhauled not only its family policy, but also its social assistance programmes and its education policy – changes that have all been financed out of the government’s family assistance budget.

The multiple objectives that the government has set and the numerous measures that it has introduced to meet them make it extremely difficult to assess the impact of these new provisions on the family budget. Thus, although the reforms have generally been well received in the press and by the government’s partners, they have become the cause of much concern among families that find it difficult to predict how these reforms will affect their budgets. Some analysts have argued, sometimes on the basis of information made public by the government in piecemeal fashion, that families with young children and families with modest incomes will be hardest hit financially as a result of these reforms. But, despite these warnings, the Minister Responsible for Family Affairs, insisted, after having made a few adjustments to the programmes, that 95 percent of families would benefit from the government’s initiative.

The federal government also embarked on a major reform of its family assistance policy in 1993 and created the Child Tax Benefit. The new initiative eliminated family allowances as well as the tax credit for dependent children, and replaced them with assistance aimed at low-income families. Thus, family assistance has changed dramatically over the past few years. Universal family assistance is, by and large, a thing of the past. Governments tend now to opt for policies aimed at low-income families. As a result, these reformed government assistance programmes are effectively creating winners and losers among Canadian families.

The first objective of this article is to provide an estimate of the impact of these new policies on the finances of Quebec families for 1998, and identify which types of families are gaining from them and which types are actually receiving less government support. The results show that families claiming social assistance are barely affected by the reforms. Families with an income ranging from $10,000 to $25,000 constitute the principal beneficiaries of the new programmes, while families with an income above $25,000 have become the programmes’ principal contributors. This means that almost 70 percent of families have had to deal with a reduction in governmental financial assistance to facilitate the increase in levels of support for approximately 30 percent of families. The results also show that the financial loss for families increases with the number of children.

Second, this article develops an alternative approach to government assistance for Quebec families, based on the same funds spent by the federal and provincial governments in Quebec. The proposed approach, largely inspired by Northern European models, would allocate universal family assistance averaging $3,000 per family annually. Estimates of the impact on family budgets of the targeted approach implemented by the governments in 1998 are compared with those of the impact of the proposed alternative. The results of the comparison enable us to demonstrate what could be an alternative family policy based on societal choices other than those favoured by the federal and Quebec governments. We then propose modifications to the financial assistance that is allocated for child-care services as well as a new work incentive programme.

There is no well-defined consensus on what constitutes a family policy. However, we can identify a number of objectives that can be pursued through family assistance measures as well as certain principles that might be observed. But the first question is this: Why would the state intervene financially to assist families? On the basis of what logic are all taxpayers called upon to subsidize people who have made the private choice to have children?

From an economic standpoint, children are the source of renewal of the human capital of an economy. Society as a whole has an interest in seeing that this human capital is of the highest possible quality so as to improve the quality of life of the collectivity. However, the transformation of a child into an accomplished adult is an undertaking that is full of pitfalls and requires much investment of time and money over a long period of time. Given the difficulty of this task, in spite of all the good will of parents, there is an obvious risk of underinvestment in the human capital of children.

Investment in human capital begins well before school starts. Right from birth, children are exposed to various stimuli that will be determining factors for their academic, personal and professional future, which is why it is so important that the collectivity ensures that families have a minimum of financial resources and access to services to support them in their parental undertaking.

Thus society can choose to compensate families for the fact of having children, regardless of parents’ income, by virtue of the principle of defraying costs relating to children’s upbringing and education. In this case, society decides that it needs children, that families are in the best position to educate them, and, consequently, it partially offsets the private cost of raising children. The governing principle here is that of horizontal redistribution from individuals and couples without children to families with children.

Society can also choose to ensure the bare minimum and guarantee a minimal expenditure per family for children’s upbringing. This is the idea of equal opportunity of children. Regardless of the size, income or structure of their families, children have the right to a minimal upbringing. The dominant principle here is that of vertical redistribution from rich families, individuals or couples to poor families. The selective nature of the assistance contributes to the objective of redistributive justice by reducing monetary poverty and income inequality.

Finally, the collectivity can choose to remove some of the obstacles to family life by facilitating the reconciliation of work and family life. Policies can attempt to encourage work-family reconciliation by subsidizing daycare costs or off setting the loss of income from the actions of a parent who devotes more time to child rearing. It can also favour labour market involvement and work incentives as a means to improve families’ standards of living.

Most of these objectives are complementary and, as such, no one is better than another. There are, for example, as many good reasons to favour the objective of vertical redistribution as that of horizontal redistribution. It is all a question of values: the choices have to reflect the type of society one wants to build. For several years now, Canada and Quebec have elected to completely remodel their assistance to families. While before the recent reforms the objective of horizontal redistribution was relatively important, governments now favour vertical redistribution; the government of Quebec has even described these changes as a “modernization” of its approach.

In 1995, the two levels of government paid a total of almost $4 billion in direct and income tax assistance to Quebec families.

Since 1986, the Quebec government has regularly increased its financial support to families by improving existing measures or implementing new ones like the allowances for newborn children (“bébé-bonus”) and young children. In December 1987, the Quebec government issued a statement of direction on family policy that provided the basis for increasing the budget allocated to families. This budget consisted of several programmes and numerous fiscal measures. In total, the cost of the Quebec government’s 1995 family assistance measures was estimated to be $2.7 billion. The whole package combined horizontal redistribution and vertical redistribution measures as well as family-work reconciliation provisions. Nevertheless, the objective of horizontal redistribution was clearly dominant.

Before the reforms, Quebec offered three principal programmes of direct financial assistance to families, for an annual outlay of around $580 million in 1995:

These three family allowance programmes recognized a number of principles:

i) They were universal. Thus, they recognized that each child has the same social value and the same basic needs. The principle of horizontal redistribution very clearly prevailed.

ii) They increased according to the rank of the child. This choice can be interpreted in two ways. First, it may have reflected the objective of supporting or even increasing natality. Second, it may have recognized the fact that the cost associated with the birth of a second or third child is greater than the economies of scale resulting from an increase in family size. Thus, a second child can use the same crib as the first, play with the same toys and wear the same clothes. The birth of the second child is thus less costly (economies of scale) than that of the first. However, the birth of the second child increases the parental burden to the extent that one parent might decide to leave the labour market for an extended period or the couple might resort more frequently to outside help for domestic tasks, etc. When one considers the fiscal measures described below, the first interpretation seems to be operative here.

iii) They offered more money for young children. They thus acknowledged that young children have specific needs that involve additional costs.

In distributing the tax burden, the income tax system acknowledged that parents have specific costs that taxpayers without children do not have, thus decreasing parents’ capacity to pay taxes. Families can claim a nonrefundable tax credit for dependent children equal to 20 percent of the amount of the recognized essential needs, evaluated at $2,600 for the first child and $2,400 for the second. The tax credit is thus based on the assumption that the economies of scale are greater than the costs related to the birth of a second child. A specific tax credit is also offered to single-parent families and to the parents of children pursuing postsecondary education. In 1995, the cost of these three tax credits was $790 million.

Families in financial need received government assistance for their basic necessities, thus providing them with a safety net in the form of a guaranteed minimum income. Together with the family allowances and federal Child Tax Benefit, social assistance programmes financed the essential needs of children in cases where family resources were insufficient. The estimated cost of these social assistance programmes in 1995 was about $500 million.

The income tax system gave families an income tax reduction by increasing the taxpaying threshold. Not only did this measure lead to a reduction in the income taxes payable by low-income families (vertical redistribution) but, combined with the Parental Wage Assistance (PWA) programme, it also gave low-income families a financial incentive to work. The PWA programme provided benefits to working low-income families to compensate for their loss of social assistance benefits (a reduction in the underlying marginal tax rate). Once they no longer receive social assistance, families could benefit from a work-income supplement to boost their income up to the taxpaying threshold. In 1995, the cost of the family income tax reduction and the PWA programme was about $440 million.

The government also granted financial assistance for child care through two channels:

i) A refundable tax credit for child-care expenses that compensated for a portion of the child-care expenses incurred. The tax credit rate varied according to income: 75 percent for low-income families and 26.4 percent for families with income above $48,000. In 1995, the cost of this tax credit was about $160 million.

ii) The Office des services de garde à l’enfance (OSGE), the office responsible for child-care services, granted subsidies directly to daycare centres, particularly for their operations. It also offered a programme of financial relief and assistance to low-income families. In all, these measures cost around $210 million in 1995.

Before the introduction of the Child Tax Benefit, the federal government provided three forms of family assistance measures. Two were universal, the federal family allowances and the nonrefundable child tax credit, and one was targeted toward lowincome families, the refundable child tax credit. Between 1984 and 1994, the federal government reduced its family assistance budget by $810 million, after taking into account the loss of purchasing power due to inflation.

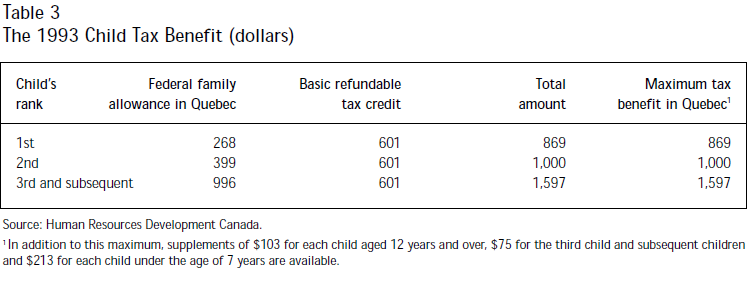

In 1993 these three provisions were replaced by the Child Tax Benefit, an assistance programme targeted toward low-income families. The goal of vertical distribution had completely replaced that of horizontal redistribution. Through its tax benefit, the federal government offered a basic benefit of $1,020 per child, which the Quebec government elected to vary according to the rank and age of the child. A working-income supplement of $500 per family was also offered. The benefit was reduced at rates of 2.5 percent for families with one child and five percent for families with two children and more when family income exceeded $25,921. In 1995, the cost of the federal government’s Child Tax Benefit in Quebec was $1.2 billion.

The Quebec government’s White Paper on the new family policy, published in January 1997, proposed the creation of an Integrated Child Allowance (ICA) to replace the following financial assistance measures offered to families:

With respect to tax measures, the White Paper proposed to

The government estimated that the ICA would cost $955 million in 1995.1 Following the implementation of the ICA, the Quebec government’s direct financial support to families with children would decrease by around $295 million from the pre-reform amount.2 As compensation, the government undertook to assume the extra cost of the new educational services and additional daycare places that were available at lower cost. As these new expenditures would be spread out over time, the new family policy still implied, in the short term, a decrease in financial assistance to families. The government estimated that from its introduction to the year 2002 or 2003, the new family policy would require additional overall funds of $235 million. This proposition radically changed the picture of government assistance to families: monetary assistance would be reduced and applied more selectively in favour of assistance in the form of services, universal in principle but for the most part benefiting families where the parents were participating in the labour market.

The ICA has come under some criticism, notably with respect to its effect on the income of families receiving social assistance and those with low-incomes. According to some impact studies, these families would experience a decrease in their disposable income, and those with children under five would lose the most.3 The government has thus pledged to adopt transitional measures by granting an entitlement to families receiving social assistance: as long as they are claimants, they will not be penalized.

The new family policy should be seen within the wider context of changes to the income security programme, the goal of which is to increase the benefits provided to low-income workers relative to social assistance recipients.4 The new policy explicitly pursues the objective of increasing the financial incentive to work and encourages labour market participation by offering more accessible child-care services, both through the number of places available and the cost to parents.

At the federal level, changes were made in 1998 to the system of benefits for children through the conversion of the Working Income Supplement into an income-tested supplement to any source of income (not only from employment) paid to families whose net family income is below $25,921. Thus,

Under the National Child Benefit initiatives, federal and provincial governments agreed that additional funds spent as part of the federal benefit and clawed back by the provincial government from families that live on social assistance will be allocated to other programmes essentially targeting low-income working families.6

The federal government’s change of direction forced the Quebec government to review and adjust the amounts and conditions of the ICA as outlined in the White Paper, even before it was implemented. The increased amounts provided by the federal government gave the Quebec government financial room to manoeuvre. The implementation of the reforms was postponed from July to September 1998 and, on the basis of the federal proposal, a system of new family allowances with transitional arrangements from September 1, 1997 to July 1, 1998 was implemented. The conditions governing this new family allowance are essentially the same as those proposed for the ICA; only the amount of the maximum allowance was reduced to take into account the federal government’s new measures.7 The government estimated that for 1998 the new allowances would cost $790 million annually instead of the $955 million announced in the White Paper.

For this new family policy, the Quebec government is making three policy choices which pursue very specific objectives:

i) The policy emphasizes assistance to families with very young children (parental leave, subsidized child care and full-time kindergarten). The government is thus aiming to establish infrastructures that promote the development of young children.

ii) The policy targets monetary assistance toward low-income working families. The government thus wants to reduce the monetary poverty of families (and children) and increase the incentive to work, pursuing vertical redistribution objectives.

iii) The policy favours families with working parents. The government thus intends to “modernize” its policy and to promote the incentive to work, principally among mothers.

The goal of horizontal redistribution is only preserved through the nonrefundable tax credit for dependent children. The new Quebec family policy is thus sacrificing its main universal component and placing the emphasis on selectivity. These are now the social choices promoted by our governments: limited responsibility on the part of society for children. Within this responsibility, priority is given to low-income families and families using child-care services. This choice is not without consequences for the family budget, which is the subject of the next section.

But first, we should note that the government is also explicitly pursuing the objective of simplifying the system of financial aid to families. Thus, the White Paper on the new family policy states that “over the years the government’s public assistance measures have been piled on top of each other and have also been affected by adjustments to taxes or transfer programmes. This has increased the complexity of the whole system and sometimes created situations of inequity.” The government concluded that “several elements of the current public system of assistance to families must be improved in order to make financial assistance simpler, more coherent and better adapted to needs.”8 Finally, the report of the Commission sur la fiscalité et le financement des services publics (Commission on taxation and public service financing) also underlined the low visibility of Quebec assistance, considering that it is spread over many programmes and tax-related provisions.9

As can be seen in Table 5, the selective nature of the assistance makes for a rather complex approach. Reducing the number of programmes certainly gives the impression of simplicity. But the makeup of the new family allowance is actually quite complex. The allowance is reduced in four distinct phases: the first three act very rapidly with reduction rates of 50 percent, 30 percent and then 50 percent again. Subsequently there is a plateau up to income of $50,000, and then the allowance is reduced again at a rate of five percent. With this calculation method, it will be difficult for families to understand how their level of assistance has been determined and, above all, they may feel that they have been unfairly treated when they compare their family allowances with those received by other families which they consider to be in a comparable situation.10 It is clear that simplicity is a rather subjective notion: is it better to have several small programmes with objectives that are easy to understand, or one programme with many objectives and a sophisticated system of allocating assistance?

Despite this subjectivity, it also seems clear that simplicity meshes better with the objective of horizontal redistribution than with that of vertical redistribution. To illustrate, if the government had truly wanted to simplify assistance to families, all it had to do was maintain a universal allowance by, for example, merging together the three types of family allowances and the nonrefundable child tax credit. Together, these four provisions would involve spending $1.3 billion in 1995, that is, an average annual amount of nearly $800 for every child in Quebec under the age of 18. This gives one just a small idea of the potential presented by the budgetary envelope that the government of Quebec allocates to families.

Finally, the government has stressed that the objective of vertical redistribution will generate considerable financial incentives to low-income families entering the labour market. It is now accepted that, compared with the situation prior to the reform, the work incentive will be better for families with an income that is slightly higher than the level of income-security benefits. For lowincome working families, the new family allowances combined with the new federal benefit provide an assured and stable income in comparison with the previous situation, because the benefit is paid automatically. Thus, the new allowance enables the government to reach its whole clientele, which was not the case under the Parental Wage Assistance programme, for which only a small proportion of families filled out the application. Therefore, in principle, the objective of inciting people to work should be easier to achieve. This is a significant improvement, because this is a critical group that is sensitive to changes in income.

Nevertheless, the work-incentive effects of the new family allowances will be less important for families with incomes above $15,000 (single-parent families) and $22,000 (couples with children). At these income levels, for each additional dollar earned, 50 cents or 30 cents will be clawed back by the Quebec government, depending on the type of family and the number of children. When the integrated allowance reaches the level of the pre-reform family allowances, families begin to pay taxes on their earnings. At higher levels of income, the Child Tax Benefit is clawed back and eventually, the entire integrated allowance is clawed back. For family income between $20,000 and $50,000, the underlying marginal tax rate can be relatively high, such that it is not clear whether the financial structure of assistance to families will offer more of an incentive to work than that under the pre-reform programmes. In recent calculations, Ruth Rose11 produces results that confirm these concerns. For example, she shows that the net disposable income of a family with two children in daycare is just about the same whether the family earns $20,000 or $15,000. Thus, the result of any additional effort to work would be a decrease in the integrated allowance or an increase in taxes with no working income supplement.

It is rather surprising that the Quebec government has not published any analyses of the global impact of its reform on families. It did not publish an exhaustive critique of the approach taken in its family policy before proceeding with the reform. Nor did it make public any analyses dealing with the consequences of this reallocation of benefits for vertical redistribution (between rich and poor families) and horizontal redistribution (between families according to the number and age of their children). Finally, no study of the projected impact of the new policy on the fight against poverty or the work incentive has been made public.

One would think that a policy change as important as this would be supported by data and analyses that would contribute to an understanding of the nature and scope of the impact on different types of families and, especially, on specifically targeted groups. The Green Book on income security, the first document to present the Integrated Child Allowance (ICA), was limited to a calculation of the benefits to be paid to certain families of a given type, earned income and number of children. The White Paper on the family policy was restricted to a presentation of the ICA scales according to families’ working income. Finally, as it announced the latest changes, the government presented only the amount of the new family allowances according to net family income. At no time did the government present pertinent information about the financial impact of the new policy on the family budget compared with the situation before the reform.

All we know is according to the Minister Responsible for Family Affairs, 95 percent of Quebec families would come out as winners in one way or another from this reform. In addition, the Régie des rentes du Québec, responsible for the administration of the Quebec Pension Plan, has let it be known that about 225,000 families will not be eligible for the new family allowances, that is, 23 percent of all families. It is hard to believe that despite the exclusion of 23 percent of families from financial assistance, 95 percent will still come out as winners as a result of the reform. Our own estimates, described below, present very different results.

Since government figures are not available, we used simulations that allowed us to estimate the impact of the new measures implemented by both the Quebec and federal governments. We cannot claim to achieve the same level of accuracy as the governments, especially considering we do not have complete information on net (after tax) family income. It is, nevertheless, a useful exercise because it allows us to tackle the issue from an angle that has, until now, been neglected because of a lack of information. Beyond the question of the percentage of families that are gaining or losing, it is interesting to pinpoint the types of families that are benefiting from the reforms and those that are experiencing an adverse economic impact. Given the objectives being pursued, notably by the Quebec government, one would expect that low-income families with preschool-aged children would benefit the most and that high-income families would be the contributors.

For our simulations we used the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), which is the dataset used by the Quebec government to conduct its (unpublished) impact analyses.12 On the basis of a representative sample, the SCF provides information on the various sources of revenue of Canadian households and families. It is released every year by Statistics Canada; the most recent survey available was conducted in 1995 and pertains to 1994 data.13

For Quebec, the SCF provides information on financial indicators for 949,000 families with children under 18 years of age14 according to specific socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., type of family, number and ages of children). Statistics from the Régie des rentes du Québec indicate that around 960,000 families were eligible for family allowances in December 1995, which is 11,000 families higher than Statistics Canada’s figure.15 (For a complete description of the estimation and simulation procedures, see the Appendix.)

Our results for all types of families are presented according to net family income class in Table 6. The first result is striking: compared with the pre-reform situation, 72 percent of all families receive less financial assistance from the Quebec government. This result is far from the figures announced by the government, to the effect that 95 percent of Quebec families would benefit from the new family policy. The differences in the results are large enough to prompt the government to disclose the methodology of its simulation. For the moment, we can only hypothesize as to explanations for this difference:

i) We underestimated the assistance coming from the Quebec government by $115 million in 1998. Moreover, for some programmes, no amount could be attributed. (Details are provided in the Appendix.) Therefore, part of the difference in the results can be explained by the fact that we underestimated the number of families that are benefiting from the reform.

ii) Since the scope of our analysis is to measure the impact of the new family allowances on the finances of families, we did not incorporate in our simulations elements of the tax reform announced in the Quebec budget speech of 1997. It seems that the government did include in its analysis the income tax reduction but did not take into account the increase in the Quebec Sales Tax (QST). Recall that from 1998 the tax reform applies to all taxpayers and not just to families. This reform is evidently completely independent of the family policy: it aims to shift a portion of the individual income tax burden onto consumer taxes. It is a tax reform based on principles of economic efficiency. To include a portion of this tax reform (the reduction in income taxes proposed for all taxpayers) without taking into account the increase in the QST gives a misleading impression of the impact of the new family policy.16

iii) In our simulations, we took into consideration all the tax-related measures, such as the tax reduction for families and the nonrefundable tax credit for children. It is also possible that the government limited its analysis to a comparison of direct financial assistance in the form of family allowances.

iv) It is possible that the government’s analysis includes the reduction in the costs of daycare services to a wide range of families, which would counteract the negative effect of reductions in family allowances. Our simulations do not take into account this element of the reforms; this issue is the subject of the next section. We will see that the impact of lowering the costs of daycare services does not quite make up for the effect of the decrease in direct financial assistance.

Taking into account the financial assistance from the federal government does not change the picture of which families gain or lose. As shown in Table 6, it is not surprising that the families that gain are those with a net income between $10,000 and $25,000, since the new programmes specifically target them. Families with a net income below $10,000 are only benefiting marginally from these reforms, when one takes into consideration what is being clawed back from those claiming social assistance. Families with middle or higher income are being expected to pay for it. In fact, families with income between $25,000 and $30,000 are contributing more than those in the $30,000 to $40,000 income bracket. This can be explained mainly by the fact that under the reform, the income tax reduction for families are now less generous.

These results show to what extent the new family assistance policy will now pursue an objective of vertical redistribution. The financial assistance formerly paid to families with a net income above $25,000 has decreased in two ways. First, the assistance they received for their children has been reduced, in part to finance the net additional support of $115 million paid to families with lower incomes. This decrease in transfers is the equivalent of an income tax increase, a financial demand that is not being made of other Quebec taxpayers. Second, the net financial support they received has been cut by at least $215 million. This “net loss” (everything else being equal) implies that families who have children under 18 and who are in this income category deserve less financial support from society, despite the fact that they had already embarked on the responsibility of parenthood, believing that there was still a collective commitment toward parents.

However, even in its vertical redistribution, the new policy does not, in fact, respect the principle of equity. Vertical equity and the objective of fighting severe poverty suggest that low-income families should be able to count on additional funds for their children. This is not the case with the reform. In addition, for families with net incomes above $25,000, one can barely differentiate average total loss between income classes. The average total loss is

Because they have higher average income than all other families, two-parent families are most affected by the new family assistance policy. Of this group, 81 percent have a net family income above $25,000 and nearly 20 percent have a net family income of about $45,000, which is the average for two-parent families. As shown in Table 7, two-parent families with a net income between $40,000 and $50,000 lose more than those in the $50,000 to $75,000 class, and nearly as much as families with incomes of $75,000 or more. (Tables A.4 to A.6 in the Appendix present the financial impact of the reforms on two-parent families according to family size.)

The Quebec government’s decision that the federal Child Tax Benefit, paid in Quebec, would no longer vary according to the rank of the child (as was the case from 1993 to 1997), produced undesirable redistributive effects. For instance, two-parent families with incomes between $25,000 and $30,000 were losing out under these new federal Child Tax Benefit parameters, even more so than two-parent families with higher incomes. Note also that the main beneficiaries of this change in policy have been families with two or more children and an income over $30,000 (see Table A.8 in the Appendix for details).

It must be recalled that one of the objectives being pursued by Quebec before the 1997 reforms was to encourage a higher birth rate. To accomplish this, it gave strong financial incentives to parents of a third child by virtue of three provisions: the allowance for newborn children, increased allowances for young children and a substantially higher federal Child Tax Benefit for the third and each subsequent child. By eliminating these provisions, the government has inevitably created horizontal inequities. This does not necessarily suggest that the changes were not desirable, especially if one considers that they enhanced vertical equity while proving ineffective in increasing the number of births.17 Nevertheless, the problem of horizontal equity posed by the transitional phase between the two systems cannot be ignored, especially since families relied on the existing measures in the course of their family planning.

For a given income class, the financial loss generally increases with the number of children. For example, two-parent families with a net family income above $75,000 would lose an average of $189 if they have one child, $457 if they have two children and $2,704 if they have three or more children. On average, two-child families with an income between $40,000 and $50,000 would lose $476, compared with $392 for one-child families in the same income class. Their loss would be even higher than that of one-child families in the next income class (between $50,000 and $75,000), where the loss, on average, would be $235 (see Tables A.4, A.5 and A.6 for details.) Clearly, these results contradict the principles of horizontal and vertical equity.

We note also that the financial gains decrease considerably with the number of children. This reflects the fact that the reforms assume economies of scale that increase rapidly with the number of children. However, as mentioned before, this approach does not recognize the increase in parental tasks as a result of a greater number of children. The two-parent families who are most affected are those that have three or more children, since 77 percent of them have family income above $25,000 and over 55 percent of them will not receive, whether in part or in whole, the minimum allowances because their family income is above $40,000.

Families with one child or more of six years of age and under represent 36 percent of all families. Their average net family income is lower than or equal to that of all families and markedly lower than that of all two-parent families in all other categories. However, most of them are not considered “poor” since 63 percent of one-child families and 62 percent of families with two or more children aged six years and under have net family incomes above $25,000. Our results presented in Table 8 show that, on average, families with an income ranging from $25,000 to $40,000 incur a financial loss due to the reforms. Considering the Quebec government’s significant policy commitment to young children, this result is rather surprising.

Families with young children and a net family income under $10,000 are mostly income-security claimants, and a considerable proportion of them are female-headed single-parent families. Their average financial gain is minimal if one takes into account the clawback from families claiming social assistance.

Only 15 percent of families with young children are in the $10,000 to $25,000 income class. When one combines financial assistance paid by the two levels of government, it is these families who are benefiting from the reform among all families with young children. Their financial gain amounts to $23 million. Families with young children also gain from the extension of low-cost child-care services, to the extent that parents in these families work outside the home. But they are also contributing significantly to the funding of this new provision through a decrease in direct financial assistance. The aggregate loss for families with young children with an income of more than $25,000 is as high as $190 million.

We should note once again that principles of horizontal and vertical equity are given short shrift in the case of families with young children. On the one hand, families with one child under six years of age and income between $40,000 and $50,000 are losing more than families with higher income. On the other hand, for any given level of income, families with two young children or more who are losing out under the reforms are losing much more than families with only one child. This is particularly true in the case of families with an income of $50,000 or more.

In our sample, female-headed single-parent families represent 18 percent of families. Their average net family income is 34 percent of that of two-parent families. For 42 percent of femaleheaded families, the principal source of income is social assistance. As a group, single-parent families are benefiting the most from the new family policy as they are gaining, on average, $419 from the reforms (see Table 9).

However, single-parent families on social assistance are neither gaining nor losing since the reforms were designed precisely to be financially neutral for them. Single-parent families with a net family income of up to $25,000 gain financially in the amount of $85 million. Finally, families with an income above $25,000 face an aggregate loss of $15 million. Considering the fact that single-parent families have relatively low income, the financial assistance from the reforms remains quite modest. In particular, many children of such families, in which the mothers’ only source of income is social assistance, still grow up in poverty.

An evaluation of the impact of the reform should take into account the fact that a part of the reduction of the family allowances is being used to finance subsidized child-care services and the extension of educational services (full-time kindergarten for five-year-olds and part-time kindergarten for four-year-olds from disadvantaged backgrounds).

Since these measures can only have a positive impact on the development of young children, one can only praise the government’s decision. A child’s initial learning comes from the family, and it appears that children from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds or from families that present serious psycho-social problems are more likely to have weak academic results.18 This result can be explained by the relatively strong relationship between a low income and a family environment that is not conducive to children’s development (e.g., the absence of the father, conjugal violence, little reading, little stimulation).19

Evaluations of the impact of daycare (or kindergarten) infrastructures on the development of young children is still at a preliminary stage in Canada, mainly due to a lack of data on the subject. Fortunately, Statistics Canada recently conducted a longitudinal survey collecting information on the type of care children receive and their subsequent academic results. A few American studies have shown that early contact with school (or with daycare centres offering an educational programme) can attenuate, if not eliminate, the differences in academic results attributable to differences in socio-economic status.20 However, it appears that, for this to occur, a certain number of conditions must be met, such as the availability of highly qualified staff whose time is devoted to an extremely limited number of children.21 In this respect, the government’s objective of promoting children’s development through universal daycare appears much too ambitious considering the resources allocated. Moreover, for disadvantaged families with children under four, there should be a follow-up programme all through primary education and a significant reduction in the educator/ child ratio at daycare centres.

Nevertheless, the government’s decision to invest in child-care services is understandable. The availability of subsidized, high-quality childcare services may constitute an essential first step toward a policy of investing in the development of young children from disadvantaged backgrounds. The impact of child-care services on the development of children from families of relatively high socio-economic status has not been extensively documented, but intuitively, it would seem to be marginal.22 There are, however, several other good reasons to favour the expansion of child-care services, regardless of the socio-economic status of the children, if only to facilitate the reconciliation of work and family life for families with young children.

However, the funding arrangements are much less clear. First, with respect to the financing of new kindergarten services, it is difficult to understand why they are being financed uniquely from within the budgetary envelope devoted to families. Why are families alone financing this new service? By virtue of what logic are all taxpayers expected to finance the whole educational system except for the expansion of kindergarten services? Clearly, the expansion of kindergarten services should be financed straight out of the budget of the Ministry of Education and therefore by all taxpayers.

Second, it is difficult to understand why childcare services will be offered at the same price to all families, regardless of their income. Two recent Canadian studies23 came to the identical conclusion with regard to the impact of variations in salaries and the cost of child-care services on the probability of participating in the labour market. They con clude that on average a 10 percent decrease in the cost of child-care services increases the probability of one parent participating in the workforce by 3.9 percent, and a 10 percent increase in the mother’s salary results in a two percent increase in the probability of using child-care services.24 These studies also indicate that the cost of child-care services has a considerable impact on the probability of working, an impact that is particularly important among low-income families. For given costs of child-care services, higher income increases the probability of using child-care services.

One cannot therefore conclude that, prior to the reform, the cost of child-care services constituted an obstacle to their use among high-income families. Lisa Powell25 shows that spousal income, as soon as it reaches $50,000, becomes the most important factor in determining participation in the labour market. In this respect, one could criticize the government’s plan: why be selective in monetary assistance but universal in child-care assistance? The argument for this choice has not been clearly made, and on the basis of simple equity criteria the opposite choice seems much easier to defend and much more attractive from the standpoint of its potential results.

Moreover, Powell reminds us very astutely that cost is not the only issue that has to be taken into account in the analysis of the impact of child-care services on labour market participation. If the goal is to reduce barriers to labour market entry, the flexibility of child-care services is just as important as their cost. An examination of data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) conducted by Statistics Canada in 1994-95 on 22,000 children aged up to 11 years confirms this need for flexibility on the part of Quebec families.26

Table A.10 in the Appendix indicates that the parents of about half of Quebec children aged up to five years were unlikely to use child-care services, simply because one parent did not work. In Table 10 we show the types of care used by all families and by two-parent families in which both parents work. It reveals a surprising variation in parents’ preferences and broad heterogeneity in child-care needs. Parents are looking for flexibility, and they show great adaptability in reconciling work and parental tasks. A majority of parents do not make use of formal kinds of child-care, and less than 20 percent of children aged three and four attend daycare centres or receive regulated home care.27 Looking at four-year-old children, less than 20 percent (around 20,000) attended formal types of child care in 1994-1995.28

In the case of two-parent, two-earner families, we note that the older the children, the more likely they are to attend regulated child-care services. Nevertheless, a greater proportion of parents elected to take care of their children at home. In addition, we should emphasize that there is still a high proportion of families (around a quarter) who do not use any type of care.

In these circumstances, can one measure how taking account of newly available subsidized child care would affect which families are benefiting from the reform and which are being made to contribute? It is difficult to answer this question, principally because the statistics that would enable outside observers to do the calculations are deficient. In addition, the distinct time horizon that characterizes child-care assistance and financial assistance makes such an analysis very complex. Childcare services are offered for the first four years of a child’s life, whereas the family allowances cover an 18-year period.

However, a simple calculation reveals that the new services offered are not likely to compensate for the financial losses experienced by parents. According to figures provided by the government, in 1998 there would have been 30,000 regulated child-care places for 90,000 four-year-old children. We can thus assume that 60,000 children did not have access to subsidized child-care places. In the best-case scenario, parents using regulated childcare services would have saved a total of $35 million after the implementation of $5-per-day daycare, which seems relatively low when one considers the overall reform.29 Recall that families with young children and an income falling in the $25,000 to $40,000 category were subject to a financial loss of $50 million ($39.5 from the Quebec government) following the government reforms.

We have seen that the two levels of government have adopted an approach favouring financial assistance for low-income families. In compensation for reduced financial assistance, the government of Quebec has offered new low-cost child-care services and the extension of educational services. An analysis of the impact of the new federal and Quebec government proposals showed that they had undesirable redistributive effects.

This approach is based principally on the willingness to redistribute sums of money from rich to poor families in the pursuit of two objectives: fighting poverty and providing incentives to work. We propose an alternative approach, using the resources from the same budgetary envelope as that used by the two levels of government. Our proposal is based on the following features:

1) All children have an equal “minimum value” to society. Their parents’ income does not determine the support provided for their development by the collectivity.

2) The time devoted to the care of children has an equal value for society. In this sense, the collectivity recognizes the various modes of care, including that by a parent at home, and does not favour one mode of care over another.

3) The parental task requires investments of time and money throughout a child’s development. While it is true that more assistance should be extended in the first years of a child’s life, it is also undeniable that parents need support through all the different stages of their children’s development.

The welfare states in developed countries have at least one feature in common: they include a mixture of direct financial assistance, tax relief measures and services intended to assist families with dependent children. However, the objectives of these systems, their structures and the levels of assistance they offer vary from one country to another.

In general, the objectives of the services offered are clear. Child-care services for preschoolaged children facilitate parents’ work and support the development and socialization of young children. In addition, social, health and educational services are investments in the future of children that promote the development of society’s future human capital. The whole of society is expected to contribute to the financing of health and educational services, regardless of who the recipients are.

The objectives pursued by financial assistance programmes, whether they are paid directly to families or whether they are provided through the tax system, are more varied. These measures may be aimed at promoting natality or contributing to the cost of children’s education. Alternatively, they might have the objective of redistributing income horizontally and vertically over the family life cycle, taking into account families’ needs or size. They might be tax deductions to promote the financial autonomy of mothers or care-giving parents, to ensure the economic security of children when the parents terminate their conjugal lives or to reduce child poverty. Or, they might aim to supplement low incomes, increase the incentive to work by allowing other social benefits (such as employment insurance) to be paid regardless of family responsibilities30 or contribute to the social contract where salaries, which do not take into account parental responsibilities, are concerned.

The result of this multiplicity of objectives has been that industrialized countries do not have uniform public policies in this field, even though they are all preoccupied with families’ living conditions. Each articulates varying degrees of horizontal and vertical income redistribution and varying priorities regarding, for example, targeted assistance to single-parent families and measures to encourage mothers to pursue professional activities.31 Table 11 summarizes the common model of public support for children in Scandinavian countries. In the three examples here, Denmark, Norway and Sweden, the support strategy is very simple: nontaxable family allowances are paid for all children, with a supplement for young children (in two out of the three countries); there is no tax relief for children; and there is a guarantee of public support for single-parent families when the non-custodial parent does not contribute financially to the support of the children (or there is none). Our proposition of a universal family allowance is directly inspired by this model.

On the basis of the principles that we have outlined, we propose, as an illustration, the implementation of a nontaxable universal family allowance. This financial assistance measure constitutes the cornerstone of a family policy that grants a minimum equal social value to all children, whatever their parents’ income. Such compensation for the private cost of raising children, would be an indication of the importance that society attaches to children and the primary role that parents play in their education. Our proposition is clearly oriented toward the principle of horizontal redistribution: taxpayers, regardless of their family status, should pay taxes on the basis of their financial ability to contribute to the financing of government assistance to families. This redistribution in favour of families allows differences in the ability to pay to vary according to periods in the life cycle where taxpayers do or do not have parental responsibilities.

This approach is also based on the economic view that without state intervention there is a risk of under-investment in the human capital of children, particularly due to the size of the investment in time and money required and the duration of the investment. An adequate investment that provides high quality human capital for the future will produce benefits for all of society.

The universal approach to family assistance offers the undeniable advantage of being much simpler than the targeted approach, since the latter has to establish thresholds and reduction rates that take into account the particularities of each family. What is more, the universal approach has the advantage of not passing any value judgment as to families’ lifestyle preferences.32 It provides the same financial assistance to families with one spouse at home as it does to those with both spouses working outside the home.

To illustrate our proposition, we use the same budgetary envelope as that devoted to families by the two levels of government in 1995. (See the Appendix for a more detailed description of the methodology used.) In total, a budgetary envelope of $2.9 billion is available, that is, a little less than the $3.1 billion spent in 1995 and the $3 billion which would be spent in 1998 after the reduction in the expenditure on social assistance. The funds dedicated to families as part of other targeted programmes are not brought into the calculation, that is, approximately $200 million for the Parental Wage Assistance programme and the sales tax credits.

We illustrate our proposition with two family allowance systems. In the first system, a family allowance of $1,752 per child is paid for all children under 18 years of age. In the second system, the allowance is more generous for young children. Thus, we suggest that a supplement of 40 percent be paid for children aged six years and under, compared with that for children aged seven to 15 years,33 and that no allowance be paid for children aged 16 and 17 years. The allowance would be $2,754 for children aged six years and under and $1,377 for children aged seven to 15 years. The exclusion of children aged 16 and 17 from family allowance benefits may seem harsh to families, as was the elimination of the nonrefundable tax credit for children pursuing post-secondary studies and the additional credit for single-parent families. This choice was made for three reasons:

1) Parents of children aged four years and under devote an enormous amount of time to their children, which most often translates into a significant reduction in paid work time or the withdrawal of one of the parents from the labour market.34

2) The parents of children aged 16 and 17 years are generally not at the beginning of their professional lives but more likely at the peak, and are thus in a better position to provide for their children’s needs.35

3) Quebec subsidizes post-secondary education to a much greater extent than do the other Canadian provinces. Considering the fact that the private profitability of post-secondary education is relatively high, it did not seem excessive to reduce assistance for it.

The universal family allowance would not be a substitute for the “child portion” of social assistance. We are making the judgment that social assistance for families should cover essential needs, while taking into account the assistance paid as universal assistance to families. This does not imply that the levels of social assistance should not be revised. However, if they are, it should be to fulfill other objectives. It will become clear later how we propose to mitigate the disincentive effects on labour market participation of social assistance.

The results of the two propositions are presented in Table 12. If we look separately at the age-dependent universal assistance,36 which appears to be the best proposition, we note the following:

1) On average, families would receive a family allowance payment of nearly $3,400 per year (slightly more than $280 per month).

2) Families with net income under $10,000 would see an increase over the amount they received in 1995.

3) The families who would be losing the most, compared with the situation in 1995, are those in the $10,000 to $40,000 income category. This is particularly true of families with an income between $25,000 and $30,000, because they no longer benefit from the income tax reduction for families. It is in these income classes, as well as those of $10,000 and less, that a combination of complementary programmes such as work incentives, highly subsidized child-care services and programmes specifically targeted at young children, could come into play.

4) The pursuit of the objective of horizontal equity means that families with the highest incomes would gain the most from this approach. However, child-care assistance, which could vary according to income, would compensate for this effect. Note that more than any other income class, higherincome families are indirectly financing part of this assistance through their income taxes.

5) Tables A.12 to A.20 in the Appendix present similar results. Families with income levels between $20,000 and $40,000 would incur a financial loss under this universal family allowance programme. However, they would be targeted by a complementary workincentive programme. Also, families with three children or more would receive less, on average, compared with the 1995 situation. This is because our proposition does not include variation of allowances according to the rank of the child, as was the case in 1995. Finally, families with children aged six years and under are definitely the big winners in this proposition, particularly those with two or more children: at all income levels, the financial assistance they receive increases.

This proposition illustrates the potential offered by the budgetary envelope devoted to families by governments. In particular, the funds available provide for a relatively generous universal approach, if one compares it with the approach proposed by the government and even with the amounts paid by the Scandinavian countries. However, any additional proposition will reduce the amount paid in family allowances. For example, reducing the agerelated allowance by $400 generates an additional $340 million annually to finance other programmes directed at families.

There are two arguments in the economic literature that justify the need for a government child-care policy.37 The first argument is one of imperfect information: the quality of child-care services is difficult to evaluate, making it hard for parents to make good choices. The government can improve this situation by regulating and subsidizing these services. In principle, such intervention would ensure that there is a minimum quality of services and, in the interest of children, encourage parents to use child-care services of a certain quality.

The second argument rests on the efficiency of choices between work, domestic production and leisure. As we have seen, the cost of child-care services could be a barrier to labour market entry, especially for those whose qualifications and professional experience are not well paid. People with lower levels of education and few professional qualifications have to turn to social assistance to meet their needs and those of their children. In the long term, this involves social and economic costs for society. It is in society’s interest to reduce the cost of entry into the labour market in order to facilitate labour market reinsertion or attachment, especially for those women with few professional qualifications. For more educated people and those with high professional qualifications or labour market experience, the cost of child-care services has much less of an effect. Other variables such as spouses’ income appear to be more important in determining labour market participation. Nevertheless, the cost of child-care services is one of the fixed costs of having a paid job, and, in general, the tax system recognizes the existence of these costs by allowing them, at the very minimum, to be deducted from taxable income.

The creation of a regulated system would encounter many more obstacles than would a policy of reducing the costs of entering the labour market. While it is desirable and easy to establish hygiene and safety standards, it is more difficult to establish standards with respect to the requirements of care, types of activity, quality of educators or desirable child-educator ratios. In short, why should we expect the government to know more about children’s needs than parents do? Parents have shown themselves to be more interested in having child-care services that meet their requirements in terms of the type of care that they want in their absence. For example, some parents want their children to be cared for according to their religious preferences. Others are opposed to any religious culture in the daycare centre. Some want emphasis placed on cognitive development, others on emotional development. Some are more interested in the proximity of the daycare centre, others in the child-educator ratios. Therefore, it would likely be difficult for governments to meet the requirements of all parents.

The picture drawn earlier of types of care chosen by Quebec parents for their young children shows that they are looking for diversity and flexibility and seem to be ready to pay for it. By the same token, they are not looking for the lowest possible cost but the availability of daycare centre places that fit in with their employment. In its reform, the government placed all the emphasis on regulated care at the expense of other potential types of care. This approach introduces a significant distortion in the child-care services market. Through the reduction in price, parents will be attracted to a type of care that does not necessarily correspond with their needs. From the economic and social points of view, it is more efficient to let parents express their preferences through the market. As we have seen, our universal family allowance proposal does precisely that: it allows parents to express their preferences and does not discriminate against families where one parent chooses (or is forced as a result of a difficult work situation) to stay at home.

The objective of allowing low-income parents to return to or stay in the labour market when their children are young is relatively simple to meet. It is not necessary to institute some form of nationalization of daycare centres as chosen by the Quebec government. This approach is probably going to involve a substantial increase in the cost of offering the service as a result of demands related to pay-equity and increased unionization. From a social perspective, this is undoubtedly justified considering the salaries paid to daycare centre educators, but from a budgetary standpoint it will exert enormous pressure on public resources. The refundable tax credit for child-care expenses that existed before the reform provided very appropriate financial assistance to parents. This assistance enabled government to better control the resources they deployed by sharing the cost of child-care services with parents, notably by assuming a more reasonable portion of the childcare costs of higher-income parents.

Our proposition consists of putting in place a system of subsidies for parents that varies according to their income (in the form of a refundable tax credit), similar to the one that existed before the reform and still applies for children who are not covered by the $5-per-day programme. The zero-fee policy would be extended to working families with very low income and parents who want to go off social assistance. Cleveland and Hyatt38 show that such an approach, even if it appears to cost a little more than what existed before the reform, is likely to bring about an important reduction in social assistance payments and significant gains in labour market participation. They estimate that if a single mother who seeks employment could earn $20,000 annually, a fully subsidized child-care programme would pay for itself. It would be difficult to estimate the costs of the measures we suggest since they depend heavily on its impact on labour-market participation for families who depend on social assistance. Nevertheless, it is realistic to suppose that such a measure can be financed from within the budgetary envelope that is currently dedicated to families without appreciably reducing the universal allowance. An amount of $400 million, almost equivalent to the value of the tax credit for child-care expenses and the financial assistance for child-care services before the reform, would be sufficient. To finance it, the age-dependent allowance would have to be reduced by around $470.

Finally, in addition to providing financial assistance to child-care services, society would benefit from offering various prevention programmes to disadvantaged families, particularly those directed toward isolated young mothers. As with the financing of education, the whole of society, not only families, must be called upon to contribute to financing these programmes. There are social advantages to these programmes, such as a reduction in the school drop-out rate or less social problems related to growing up with a disadvantaged background (e.g., drug addiction and delinquency).