La présence des organisations d’habitation autochtone en milieu urbain remonte à 1970. Elles ont lutté contre les privations disproportionnées dont souffrent les Autochtones en matière de logement et contre la discrimination dont ils sont victimes dans le secteur du logement tant public que privé, et leur ont procuré des habitations en tenant compte le plus possible de facteurs culturels appropriés dans le contexte des programmes publics de logements sociaux.

La présente étude examine la façon dont ces organisations se sont adaptées à l’évolution du contexte politique. Pour s’attaquer à d’autres aspects de la qualité de vie des Autochtones en milieu urbain, elles ont trouvé des façons innovatrices de réaliser leur mandat, agrandi leur porte-feuille d’unités de logement et élargi leur champ d’activité, notamment en mettant en place des programmes de formation à l’emploi, des entreprises sociales et des services de garderie. L’auteur se penche sur quatre études de cas (les sociétés Kinew Housing à Winnipeg et Lu’ma Native Housing à Vancouver, la Corporation Waskahegen au Québec et la Métis Urban Housing Association of Saskatchewan) pour proposer des moyens d’améliorer la politique de l’habitation de façon à relever la qualité de vie des jeunes Autochtones urbains, dont le nombre s’accroît de plus en plus. Le réseau des associations d’habitation autochtone possède des réserves considérables d’aptitudes et de leadership, mais ces organisations ont besoin de l’appui de l’État pour transformer leurs innovations en programmes viables à moyen et à long terme.

Les exemples des sociétés Lu’ma et Kinew servent à illustrer la présence de capacités vigoureuses d’innovation et de leadership au niveau local. Les responsables de ces projets ont montré qu’ils sont capables d’améliorer la qualité de vie en milieu urbain en fonction des propres besoins des Autochtones, mais leurs ressources financières ne leur ont permis de construire qu’un petit nombre d’unités de logement. Par contre, l’association d’habitation métisse de la Saskatchewan et la Corporation Waskahegen, qui relèvent d’organisations provinciales, font preuve d’une grande efficacité et peuvent influencer l’orientation des politiques et des programmes, ce qu’une association locale serait incapable de faire. Cependant, bien que des ressources additionnelles aient été consacrées au logement autochtone hors réserve en Saskatchewan et au Québec, on ne sait pas dans quelle mesure ces fonds serviront à construire de nouvelles habitations ou seront plutôt affectés à l’entretien du stock de logements actuel.

Au cours des 15 dernières années, les organisations d’habitation autochtone ont fait preuve d’imagination en s’attaquant aux défis soulevés par la réorientation de la politique de logement. Malgré cela, elles n’ont pas pu réaliser tout le potentiel d’ingénuité de leurs programmes, ou même mettre en place des activités répondant entièrement aux besoins des communautés, parce que le financement public ou bien était insuffisant, ou bien n’était pas rattaché à un programme national cohérent axé sur un ensemble précis d’objectifs et de cibles pour le logement social. Il importe que les gouvernements fournissent le cadre politique et les ressources dont ces organisations ont besoin pour construire des logements capables d’améliorer la qualité de vie des Autochtones en fonction de leurs propres besoins. En l’absence d’objectifs sociaux clairement définis et d’engagements financiers à long terme de la part de l’État, les associations de logement autochtone risquent de devoir consacrer une part trop grande de leur temps à solliciter des financements à court terme et à chercher des partenaires capables de renforcer leurs projets.

Les dirigeants des organisations de logement autochtone, les chercheurs universitaires, les leaders communautaires, les politiciens et les représentants du secteur public doivent accomplir deux tâches difficiles mais fondamentales pour marquer des progrès réels dans ce domaine : ils doivent préparer et mettre en œuvre un retour aux objectifs sociaux de la citoyenneté rattachés au droit au logement de tous les Canadiens, et ils doivent définir et mettre en pratique une vision inclusive de la citoyenneté qui stipule que, pour progresser, il faut que les Autochtones puissent contrôler eux-mêmes le contenu et le mode d’exécution des programmes ainsi que l’évaluation des résultats.

Over half of the 1,172,790 individuals who identified themselves as Aboriginal people in the 2006 Census lived in urban areas; their housing was, on average, significantly more crowded and in poorer repair than that of non-Aboriginal people (Statistics Canada 2008). Since as early as 1970, Aboriginal housing organizations have been operating in urban areas. They have combatted disproportionate housing hardship, fought discrimination in the private and public housing sectors and delivered housing in the most culturally appropriate ways possible within the parameters of state social housing programs. These organizations offer us one of the most successful examples of how Aboriginal community activism can effect urban policy innovation and transform a local experiment into a national program. They have survived changing policy regimes and — particularly in the past 15 years, which have seen reduced state investment in social housing as well as the growth of partnerships and competitive urban policy — they have managed to reorient their approach to developing new housing.

This paper looks at how Aboriginal housing organizations have taken innovative new approaches to their mandates, expanding their housing portfolios and range of activities to include employment training programs, social enterprises and daycare services. It draws on four case studies — Kinew Housing in Winnipeg, Lu’ma Native Housing in Vancouver, Corporation Waskahegen in Quebec and the Métis Urban Housing Association of Saskatchewan — to examine the ways in which housing policy could be augmented to improve the quality of life of young and growing urban Aboriginal communities. There is tremendous capacity and leadership in Canada’s network of Aboriginal housing organizations, but these bodies need state support to transform innovations into sustainable programs over the medium to long term.

The paper begins with a brief description of the housing situation of Aboriginal city dwellers. This is followed by an examination of related policy history and a theorization of transformations in the sector over the past several decades. Next, the four case studies are presented; and the paper concludes with a series of recommendations for increasing the scale and impact of local innovation.

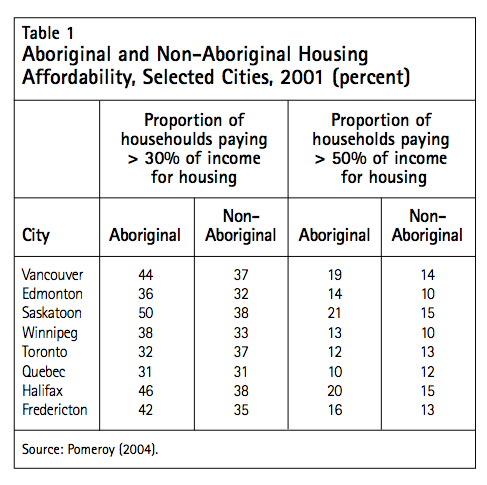

Studies conducted in 2001 of the housing circumstances of Aboriginal people in census metropolitan areas showed that 25 percent were in “core housing need”; this means that their housing was inadequate, unsuitable and, most commonly, unaffordable — that is, costing 30 percent of household income or more (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation 2004). The corresponding figure for non-Aboriginal households was 15 percent. Table 1 shows the corresponding figures for major Canadian cities. Severe rent burden, which occurs when a household spends 50 percent or more of its income on rent, was also significantly higher among Aboriginal households in 2001. Roughly threequarters of the off-reserve Aboriginal residents in core housing need lived in urban areas (Ark Research Associates 1996; Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation 2004). In 2006, the off-reserve Aboriginal population experienced crowding (that is, one or more people per room) at a rate of 11 percent, compared to a rate of 3 percent in the nonAboriginal population (Statistics Canada 2008). Crowding was particularly acute in many of Canada’s largest cities, especially on the prairies. In Saskatoon, 9 percent of the Aboriginal population lived in crowded conditions in 2006, versus 1 percent of the nonAboriginal population. The disparity was highest in Prince Albert, where the figure was 11 percent (Aboriginal) versus 1 percent (non-Aboriginal). In Winnipeg, 5 percent of the Aboriginal population lived in crowded conditions, versus 3 percent of the nonAboriginal population (Statistics Canada 2008).

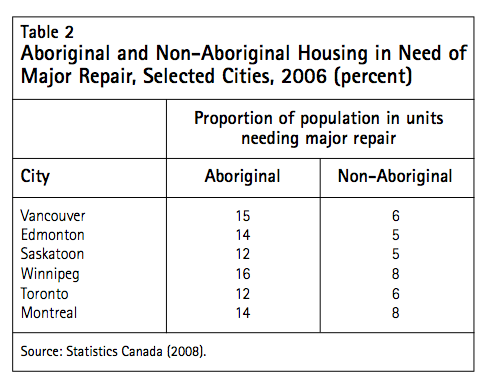

In 2006, 15 percent of Vancouver’s Aboriginal population was living in housing that needed major repairs; 6 percent of the non-Aboriginal population was in similar circumstances (Statistics Canada 2008) (table 2). The corresponding figures for Edmonton were 14 percent (Aboriginal) and 5 percent (non-Aboriginal). In Toronto, the figures were 12 percent and 6 percent; and in Montreal, they were 14 percent and 8 percent. The homeownership rate for off-reserve Aboriginal people was about 17 percent lower than that of the non-Aboriginal population (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation 2004), and homelessness and intra-urban residential mobility were considerably higher among urban Aboriginal people than among urban non-Aboriginal people (Distasio and Sylvester 2004). Mobility between urban areas and rural or reserve communities is also a notable issue in discussions of housing in the urban context because it is related to the way in which “home” is understood (Norris and Clatworthy 2003).

In examining the ways in which we can protect or enhance Aboriginal quality of life, it is useful to recall Salée, Newhouse and Lvesque’s study of the important role played by the state in such an endeavour: “quality of life hinges in part on what the state can or cannot or will or will not offer citizens, or on whether or not the state shields them from market inadequacies. It is a function of the guarantees that the state provides citizens that basic necessities will be covered and that protection from physical or material risks and psychological distress will be available” (2006, 6-7).

For a time, affordable and adequate housing for all Canadians was a social goal valued by governments and many citizens as a right; it was one of the pillars of the Canadian welfare state (Hulchanski 2002). Over the past few decades, as the welfare state has aged, housing has become its most dilapidated pillar. Yet there is no shortage of evidence that the proportion of Canadian low-income households experiencing housing affordability problems has increased remarkably over time — most notably, since the federal government stopped building new stock under its nonprofit and cooperative social housing programs in the 1990s (Hulchanski 2002; Moore and Skaburskis 2004). There is also no shortage of evidence that strong housing policy is central to, and interconnected with, beneficial outcomes in other welfare sectors, such as health, education and income security (Carter and Polevychok 2004; Dunn 2000; Kemeny 2001).

Most housing scholars agree that the only real way to address the shortage of adequate and affordable housing for those who cannot satisfy their needs in the diminishing private rental market or the highpriced home-buyers market is for the state to build such housing (Moore and Skaburskis 2004; Walks 2006). More specifically, the state needs to provide social housing organizations with adequate and dependable resources to do the job themselves. In some cases, assisted home ownership is desirable, and this option can also be facilitated by social housing organizations. Those organizations and the housing stock from earlier decades that they still manage are the greatest legacy of the period in which social housing was a solid pillar of social welfare — generally, the mid-1960s through to 1993. A significant part of Canada’s social housing provision infrastructure is the legacy of the urban Aboriginal housing organizations.

In 1973, changes to the National Housing Act (NHA) ushered in a series of new social housing programs. The minister responsible for housing, Ron Basford, declared upon amending the NHA that “It is the fundamental right of every Canadian to have access to good housing at a price he [s i c] can afford. Housing is not simply an economic commodity that can be bought and sold according to the vagaries of the market, but a social right” (Canadian Council on Social Development 1976, 13). These new programs addressed public discontent with the planning and design of public housing and urban renewal, which were seen as disconnected from community aspirations and in many ways destructive to existing community networks. Included on the list of new initiatives were the cooperative housing, nonprofit housing, rent supplements, neighbourhood improvement and residential rehabilitation programs. Tenants in the social housing programs would pay according to their income level — typically, rents amounted to between 25 and 30 percent of income.

The Urban Native Housing Program (UNHP) was one of the social housing programs delivered by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), with rental rates pegged to tenant incomes. It grew out of the distinct need among Aboriginal people in urban areas — many of whom had come from rural or reserve communities — for culturally appropriate social housing, and it was facilitated by the capacity of growing urban Aboriginal communities to articulate and address their priorities. Approximately 11,000 units of social housing were developed under the UNHP between 1970 and 1994 and administered by about 100 Aboriginal housing organizations; the total social housing stock was roughly 661,000 units (Pomeroy 2004; Wolfe 1998).

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples reported that culturally appropriate housing was of central importance to social, cultural and economic well-being in urban areas and, not surprisingly, the commission made reference in this context to the importance of housing provided by Aboriginal housing organizations developed under the UNHP (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996a). Urban Aboriginal housing corporations are run by boards of directors and staff comprised mainly of Aboriginal people. Many of the Aboriginal tenants they serve have come from rural or reserve communities and have little experience of urban home maintenance, or of urban life in general. In the 1970s, the UNHP recruited counsellors to help these tenants to adjust to their new environment. This initiative was unique to the UNHP; after several years of trying, Aboriginal housing advocates had failed to win recognition from the CMHC of tenant counsellors as a legitimate program expense (Fulham 1981; Lipman 1986). In 1996, the tenant counselling services were noted by the Royal Commission for their importance in building tenant self-reliance (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996a); and urban

Aboriginal housing organizations began to take a “softer,” more individualized approach to tenancy management issues (Walker 2003), as well as accommodating shifts in household composition as people moved between city, rural and reserve communities (Skelton 2002; Wilson 2000).

There is evidence suggesting that when social housing is provided to Aboriginal households by Aboriginal organizations, the outcomes are better than they are when it is provided by mainstream organizations. In an evaluation of its urban social housing programs, the CMHC found that the UNHP outperformed the mainstream nonprofit and rent supplement programs on a variety of well-being indicators (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation 1999). Compared with Aboriginal tenants in mainstream social housing, a significantly higher proportion of tenants in UNHP units had improved access to social services; they made more friends and felt more secure, settled and independent. The Royal Commission pointed out further benefits of the UNHP: the effect of family stabilization gave tenants a secure base from which to pursue education and employment; it created a domain of control where cultural identity could thrive (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996a, b). Despite this important, though limited, evidence, there has been virtually no research conducted on the provision of urban housing by Aboriginal organizations using culturally meaningful approaches (Walker and Barcham 2007). Research in the Australian Aboriginal housing sector suggests, however, that such approaches yield significant positive outcomes (Walker, Ballard and Taylor 2003), as do similar approaches used in other sectors pertaining to Canadian Aboriginal communities, such as health care (Minore and Katt 2007) and suicide prevention (Chandler and Lalonde 2004).

The way the state intervenes in the housing market has changed greatly since the 1970s. From 1970 to 1993, the federal government led the way in building a nonprofit and cooperative social housing sector; the state took an active role in program planning, implementation and long-term funding. From 1993 to 2001, the state stopped building new social housing. The consequences were soon noticeable. In 1999, after witnessing a rapid rise in the rate of absolute homelessness and inner-city socio-economic deterioration (see, for example, Toronto Mayor’s Homelessness Action Task Force [1999] and Winnipeg’s Inner City Housing Coalition [2000]), the federal government reentered the nonmarket housing sector through the back door. It began targeting the problem of homelessness rather than that of insufficient housing, and it used Human Resources and Social Development Canada (HRSDC) instead of CMHC. HRSDC launched the Supporting Communities Partnership Initiative (SCPI) in 1999 to provide one-time funding contributions to urban communities offering proposals to address homelessness; these proposals had to allow for sustainability and involve partnerships.

In 2001, the federal government launched the Affordable Housing Initiative (AHI) through the CMHC, officially marking its small-scale re-entry into low-cost housing provision. It avoided using the term “social housing,” which might have been associated with past social welfare programs. The initiative was remarkable for its much-reduced capacity for meeting housing needs and for its lack of a coherent goal. For example, the AHI’s purpose was unclear. It seemed to have no vision or measurable target, and the federal government demonstrated no commitment to leadership in the sector. The AHI was simply a five-year project in partnership with the provinces that provided a lump-sum capital subsidy to assist initiatives already underway or starting up in communities across Canada. In the end, it produced very few new housing units, and the funding it supplied was generally insufficient to reduce rents enough for those most in need of nonmarket housing (Pomeroy 2004; Shapcott 2006). It was also insufficient to allow for a sustained subsidy to housing providers to maintain rents at an affordable level over the medium to long term.

The federal government did not re-enter the offreserve Aboriginal housing sector until 2006, when it budgeted $300 million to be rolled out over a threeyear period: the Off-Reserve Housing Trust (OHT). The OHT resembles the AHI in many ways. It will not go very far toward addressing the need for affordable housing in urban Aboriginal communities. Neither the AHI nor the OHT provide a continuing subsidy for new units, and so it is unlikely that they will be affordable for those most in need, like many of those served by the UNHP.

The move from large-scale, state-led, goal-oriented social housing programs to programs like the AHI, SCPI and OHT — one-time commitments of capital funding to assist local initiatives in the voluntary sector — has been theorized differently by a number of scholars. Bob Jessop argues that the state must now, in contemporary times, be understood in a strategic-relational context as one actor among many (2000). He maintains that there is an increasing reliance on networks, partnerships and “reflexive self-organisation” across public, private and voluntary sectors to achieve societal goals (2001). It follows that the state makes strategic contributions to relational production processes in communities where voluntary sector partners are often those responsible for program sustainability.

A second and somewhat compatible way of theorizing the shift away from state-led social programs concerned with providing a strong foundation for common social citizenship is presented by Anthony Giddens and Jane Jenson and Denis Saint-Martin. They argue that in response to neoliberal critiques of the welfare state, social democratic governments have moved away from the progressive realization of social rights, such as affordable and adequate housing for all citizens. Social cohesion — the strength of social bonds in society — replaces social rights as the goal of policy-makers and decision-makers (Jenson and Saint-Martin 2003). Keeping people engaged in active citizenship, in producing their own welfare, is seen as a way to increase social cohesion. Giddens conceptualizes this turn as a new relationship between a “social investment state” and an “active civil society” in which both state and civil society actors are better able to adapt to shifting economic conditions, and to change priorities and policy directions quickly and strategically in response to market and social forces (1998). Long-term funding commitments, such as those embedded in the discontinued social housing programs (for example, 35-to-50-year operating agreements), are not highly compatible with this model of the social democratic state. The frameworks of the AHI, SCPI and OHT are much more so.

These theorizations characterize the state as a passive subject pulled in inevitable directions and driven by too-powerful market and social forces. Some authors have, appropriately, opted to envision the state as a powerful rather than a passive force, and they present a third way of contemplating the state’s role in stabilizing citizenship, addressing market inadequacies and enhancing quality of life. They argue that the dismantling of social welfare, such as Canada’s social housing programs, was at best the result of poor political leadership in the face of financial downturns and governance crises. At worst, they observe, it was a conscious move at a historic moment of opportunity to usher in an era of elite power consolidation, sacrificing the gains realized by the rest of society through a strong welfare state after the Second World War (Harvey 2005; Ralston Saul 2005).

The movement by Aboriginal peoples in Canada and internationally to advance self-determination by re-ordering relations between the state and Aboriginal society has been particularly strong since the 1960s (Cardinal 1969; Durie 1998; Green 2005). Finding good ways of “living together differently without drifting apart” requires self-determination in the context of treaty and constitutional partnership and the cohabitation of peoples (Maaka and Fleras 2005, 300). Roger Maaka and Augie Fleras have conceptualized a useful dichotomy of universal versus inclusive citizenship. The recognition of self-determination, with meaningful consequences in statute, policy and program practice, is a foundation of inclusive citizenship. It is the opposite of the one-size-fits-all, or one-size-should-fit-all, approach that characterizes universal citizenship in statute, policy and practice. The right of and aspiration for self-determination affects how social welfare goals such as housing are pursued. Such goals must be achieved largely by Aboriginal peoples themselves in partnership with settler governments. Self-determination in settler countries like Canada is not a right to separation and isolation — it is a right to fulfill community aspirations in partnership with non-Aboriginal communities through mutual recognition and respect.

Self-government in Canada can be understood as an approximation of self-determination that is roughly compatible with state structures and bureaucracies (Green 1997). Adhering to section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, the federal government has indicated its intent to enter into partnerships with Aboriginal communities (including urban ones) off land bases in order to further the implementation of self-government in meaningful ways (Wherrett 1999). Self-government can involve delegating to Aboriginal institutions administrative authority over state programs (for example, child and family services) or community governance — Aboriginal institutions maintain a circumscribed autonomy while the state retains power over the terms of Aboriginal development (Alfred 1999). In urban areas, the most pervasive model of self-government is based on associational communities (as opposed to land-based communities) characterized by self-governing Aboriginal institutions in sectors like housing, health, education, culture and justice (Barcham 2000; Peters 1992; Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996a).

The neoliberal project, which gives rise to a very different policy environment for social housing, is not incompatible with advances in Aboriginal selfdetermination and self-government. Self-governing urban organizations are the primary actors in the struggle for urban community self-determination. By facilitating their development, the state disposes of its responsibilities for administering social welfare; however, when it transfers responsibilities to these organizations, it provides inadequate resources to support programs yet demands accountability.

The following case studies provide insight into the ways in which the transformation in social welfare is affecting the urban Aboriginal housing sector. They show how urban Aboriginal housing organizations, which were established as a means for large government housing bureaucracies to deliver long-term programming, are now seeking their own innovative solutions and trying to find ways to support their initiatives with sporadic government funding in an environment characterized by competitive urban policy.

The case studies combine work undertaken in this policy field in 2008 (Walker and Barcham 2008; Walker 2008) with the work I did with these organizations in 2007. Case study data were gathered through one-on-one personal interviews with executive directors, managers and senior staff at each of the housing organizations; additional information came from agency documents given to me during the interviews. What follows is analysis of interview notes, although all interviewees were given the chance to suggest revisions to my representation. All but one participant submitted comments for revision, and these have been incorporated.

Kinew Housing today operates almost 400 units of subsidized (social) rental housing. Its story is inextricable from the history of the UNHP. The project, which Henderson refers to as “the Kinew Housing experiment” (1971), was the first urban Aboriginal housing development to derive from the community, and it was subsequently reproduced in other cities across Canada and taken up by the CMHC as a national model.

Kinew Housing was incorporated under the sponsorship of the Indian and Métis Friendship Centre in Winnipeg in 1970 to meet the need for culturally appropriate Aboriginal housing in the city. A group led by several Aboriginal women organized a housing committee at the Friendship Centre to serve as an advocate for Aboriginal tenants subjected to racism and discrimination in the public and private rental housing markets. The group determined that the best way to combat the problem was to establish an Aboriginal housing provider that could tailor its practices to the Aboriginal community.

Kinew Housing purchased the first homes with private funding and at low prices from the Winnipeg branch office of the CMHC. Among its objectives, Kinew included the provision of soft services — specifically, the services of a tenant counsellor. In 1971, its attempts to secure CMHC funding for such a counsellor failed, and the role was filled on a voluntary basis by a Kinew board member. Kinew’s objective of delivering a rent-to-own model of housing was not allowed under the section of the NHA within which it operated. But once Kinew had moved beyond the experimental phase, sustainable long-term government funding was orchestrated within section 15.1 of the NHA, which covered nonprofit (rental) housing. Several years later, tenant counsellors were recognized as a legitimate expense for Kinew Housing (and for the UNHP generally). This, along with the allocation of higher operating budgets (due to the pepper-pot nature of Kinew’s portfolio, the fact that it provided single or semidetached dwellings for larger families and its obligation to maintain its older stock) and a deeper subsidy (that is, rent was set at 25 percent of income rather than 30 percent), exemplified how autonomy or self-determination could work in response to Aboriginal community needs. Yet, despite these differences, the program parameters governing the UNHP were much the same as those governing other mainstream social housing organizations under section 15.1, and later section 56.1, of the NHA.

After 1993, when the period of unit construction and acquisition under the UNHP ended, over 10 years elapsed without Kinew adding to its unit portfolio. In late 2005, a commitment was made to develop 10 new units under the Affordable Housing Initiative agreement struck between the federal and Manitoba governments in 2002. The two governments each contributed $75,000 per unit, and the 10 three-bedroom, two-storey subsidized rental units of infill housing in the

Centennial (inner-city) neighbourhood are now occupied. A small company operated by a Métis family was contracted to build them. Over half of Centennial’s residents are Aboriginal people, and the neighbourhood’s community improvement association was deeply involved in this project. The Centennial Community Improvement Association selected tenants from among neighbourhood residents, who were then approved by Kinew Housing. A second phase of development, comprising 10 more units, was completed and tenanted in 2007. As Centennial has recently been categorized as one of Winnipeg’s improvement zone neighbourhoods, the second-phase development received a financial contribution from all three levels of government. In both phases of development, any leftover government funding was put in a reserve account to offset any year-end deficit. The Manitoba government has signed an agreement with Kinew to provide rental subsidies to make units affordable to their Aboriginal tenants.

As it did back in 1970 Kinew Housing is finding new ways to deliver social housing to its constituency using whatever means are available through government programs and community initiatives. While the development of new units is a positive thing, the rate of development is nowhere near the level it must reach to fill the growing need — in 2004, over 2,000 Aboriginal families were on the waiting lists at Kinew and other Winnipeg Aboriginal housing organizations (Simms and Tanner 2004). The greatest challenge is represented not only by the insufficient amount of new development, but also by the fact that the subsidy agreements attached to existing UNHP units will soon expire, since their mortgage loans are nearly paid out. Once this occurs, the social housing provider will own the housing asset, and rents will have to cover operating costs. The subsidy for many social housing organizations is linked to a low interest rate over the amortization of their mortgages. Given that mortgage repayment is the largest expense, and the reason for the subsidy over the repayment period, once the mortgage is repaid, the housing organization should remain viable — cash flow requirements will decline significantly. However, it doesn’t work that way for urban Aboriginal housing providers; due to their use of the rent-geared-toincome formula (rents are fixed at roughly 25 percent of tenants’ incomes) at a deeper subsidy, they have lower rent revenues. In 2007, 17 Kinew units came off subsidy. By 2008, that number will have increased by 83 units, and by 2010, half of Kinew’s units will be off subsidy, meaning that Kinew will need to charge its tenants higher (market) rents. Tenants on social assistance will go from paying $295 a month to paying roughly $500 a month.

Reports commissioned by the Canadian Housing and Renewal Association on the future of social housing after subsidy (operating) agreements expire note specifically that, with few exceptions, Aboriginal housing organizations will not remain viable as social housing providers unless new subsidy is extended to them (Connelly Consulting Services 2003; Pomeroy 2006). The Off-Reserve Aboriginal Housing Trust funds allocated to the Province of Manitoba will be used mostly for building new housing stock, although the number of units is still uncertain. At least some of the success — and probably a significant measure of it — that Kinew has enjoyed in adapting to a new and often competitive policy environment is due to the fact that its manager, who has been with the organization since its early years, has acquired a great deal of expertise and won much respect within the Manitoba housing and social services community.

Vancouver’s Lu’ma Native Housing Society, like most other Aboriginal housing organizations in cities across Canada, began operating under the UNHP and has struggled since 1993 to find ways of delivering new social housing that meets the needs and fulfills the aspirations of the Aboriginal community.

Lu’ma (“new beginnings” in Coast Salish) operates about 325 subsidized rental housing units and is the city’s oldest Aboriginal housing society — it was incorporated in 1980 under the name Vancouver Indian Centre Housing Society. About 95 percent of its units were developed under the UNHP; the other 5 percent were developed under a British Columbia Housing program. Since 1993, Lu’ma has developed 50 new units, including the Art Zoccole Aboriginal Patients’ Lodge, opened in 2004. The lodge was a response to the need expressed in the Aboriginal community for a supportive living environment for permanent residents and those in Vancouver temporarily for medical care. The furnished family units are complemented by a large common room on the ground floor. The building was designed by Nisga’a architect Patrick R. Stewart to reflect Aboriginal cultural elements. Services include resident transportation, daycare and housekeeping; there is also a lodge coordinator (Stewart 2007). This project was the product of a partnership between a number of agencies and funders, including several First Nations, the City of Vancouver, the Governments of Canada and British Columbia, several charities and philanthropic organizations and, primarily, the BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre.

In 2000, Lu’ma was granted the authority by the federal government and the Vancouver Aboriginal community to administer federal homelessness programming in Metro Vancouver. Lu’ma is the community entity for an Aboriginal homelessness steering committee comprised of over 20 Aboriginal serviceprovider organizations that cater to those who are homeless or at-risk of becoming homeless.

It has also extended its reach beyond its own social housing portfolio to provide property management services to BC Housing for an Aboriginal youth housing project and to act as a commercial landlord for other Vancouver Aboriginal organizations. Lu’ma has ventured into the commercial market in an attempt to become sustainable, given that operating subsidies are no longer offered by the federal government. Lu’ma is pursuing new projects to develop assisted home-ownership options for tenants who have exhibited the desire and potential to make the transition to that tenure type. Partnering with the Aboriginal Mother Centre Society, Lu’ma is also engaged in trying to complete the housing spectrum from emergency shelter units for the homeless, to transitional units, to social rental housing, to assisted home ownership. Proposals have been developed for 10 shelter units, 10 units of transitional housing, 10 units of social housing, and 20 units of assisted ownership and a variety of additional services and supports, like a food bank, a clothing exchange, daycare, retail space and a social enterprise centre.

With its full spectrum of tenure types built on a foundation of common cultural and social supports, Lu’ma aspires to see its clientele move from homelessness to home ownership in a supportive environment. It is several years into a large-scale project with numerous Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal partners to create a housing development in Vancouver that would include homes for Aboriginal foster children and families. The Aboriginal Children’s Village is conceived as a mixed-use, family-oriented site with over 20 units of apartment-style dwellings, office and retail space, and an Aboriginal longhouse for cultural uses.

Lu’ma has responded to the post-1993 operating environment by pursuing partnerships with other organizations; by undertaking revenue-generating projects such as contracting out its services as a property manager; and by seeking new sources of funding for the soft services that sustain community and culture in the housing process. It is also offering assisted ownership options to Aboriginal households. While Lu’ma sees the 2007 competitive proposal call by the Off-Reserve Aboriginal Housing Trust as an important source of funding for its new housing development plans,1 one challenge it faces in the post-1993 period is the relative scarcity of the financial resources required to meet the growing need for social housing in the Aboriginal community. The financial resources allocated to British Columbia under the trust are not substantial — they will scarcely make a dent in the roughly 5,000 names on Vancouver waiting lists for Aboriginal housing. A second challenge for Lu’ma is to find a way to continue subsidizing existing units after the expiration of its operating agreements with the CMHC, which have set rents at 25 to 27 percent of household income. In 2006, operating agreements expired on about 10 Lu’ma units; in 2007, about 10 more will expire, and the number will continue to grow. Lu’ma has had to respond by charging rents on these units that match normal market rents for comparable private sector units in comparable parts of the city.

A third challenge is that proposal development times under the OHT are short; there are only a few weeks between call and deadline. Proposal development funds are not provided upfront as part of the OHT administration budget, making it difficult for applicants to find qualified people to give technical assistance in drafting the proposals. Community groups may learn how to be more resourceful as they compete for scarce funds, but the situation lets governments off the hook. The pressure on the state to develop a clear set of strategies to eradicate homelessness and to ensure adequate and affordable housing for citizens is alleviated. A large part of Lu’ma’s success (like that of Kinew, in Winnipeg) in adapting to the changing policy environment is attributable to its chief executive officer, architect Patrick R. Stewart, and the organization’s professional affiliates. They have an impressive track record in Vancouver and throughout BC, and they have built a reputation for being innovative and visionary. The importance of such leadership capacity cannot be understated in a competitive urban policy environment.

Since 1972, Corporation Waskahegen (which means “shelter” or “house” in Algonquin) has been managing and delivering social housing and related services and supports to Aboriginal people living off-reserve. It is a service organization for the Native Alliance of Quebec. Its mandate derives from the alliance, and it works under a self-management agreement with the Société d’habitation du Québec. This relationship makes Waskahegen the primary social housing body for a potential clientele of approximately 26,000 First Nations and Métis people living off-reserve in six regions of the province. Waskahegen manages about 1,100 social housing units built under the UNHP, plus approximately 775 units developed under the Rural and Native Housing Program and 137 under other operating agreements.

While it is the province’s central self-governing Aboriginal housing organization, Corporation Waskahegen has expanded its role over the years. It also delivers, among other things, architectural and construction project management services, and employment and economic development programs. It has diversified its range of roles and responsibilities to reflect its belief that housing is a key element of an interrelated set of policy sectors that impact on people’s quality of life. Corporation Waskahegen is the largest, oldest and most well-established (though not the only) provincial self-government organization in Canada’s off-reserve Aboriginal housing sector.

Relatively few housing units have been built under programs such as the AHI and the OHT. For example, only eight new units were built by Waskahegen under the AHI, and the money transferred to the Province of Quebec under the OHT initiative has not been used by or allocated to Corporation Waskahegen to build new housing. At the time of writing, the $38.2 million in OHT funds allocated to Quebec had been in the provincial treasury for several months (a reference to the OHT is made in the province’s 2008-09 budget plan, in a table based on the schedule of federal transfers). At the August 2007 Katimajiit Conference, held in Nunavik, the Government of Quebec announced that it would invest an additional $25 million to build 50 housing units in Nunavik, but it did not indicate whether those funds would come from the OHT.2 Notwithstanding this announcement for Nunavik, Waskahegen needs an additional 1,500 units of social housing in order to meet the demand.

As they are in other parts of the country, operating agreements in Quebec on units developed under the UNHP are expiring, and with them the rent subsidies to those most in need of adequate and affordable housing. Despite Corporation Waskahegen’s status as one of the country’s oldest and best-established provincial Aboriginal housing organizations with a self-governing mandate, and despite the fact that it has a well-developed leadership, it is not benefiting to any great extent from new affordable housing policy frameworks since 2001.

The Métis Urban Housing Association of Saskatchewan (MUHAS) was established in 1992 to address common housing policy and program issues affecting its members — six independently owned and operated Métis housing corporations. In this way, it is very different from Waskahegen, a corporation that owns units across the province. In 1997, the Government of Canada, through the CMHC, implemented an agreement with the Province of Saskatchewan to transfer existing social housing from the federal to the provincial government; the Saskatchewan Housing Corporation (SHC) became the provincial agency responsible for delivering the housing. Shortly thereafter, the SHC became an associate member of the MUHAS. At this time of historic change in the social housing sector, the MUHAS articulated a vision of self-government in relation to the downloaded UNHP stock, which represented a large portion of the social housing portfolio that had been shifted to the province. Over a period of two years, the SHC and the MUHAS met several times to discuss common program issues and the need for a new operating agreement — one less cumbersome than that passed down from the CMHC. An agreement was worked out between SHC and MUHAS member housing organizations whereby Aboriginal urban housing would be placed under the relatively autonomous control of the organizations’ boards. Over a period of about 30 months, between 1998 and 2001, the SHC and the MUHAS conducted negotiations on that agreement. Each MUHAS member corporation signed a separate agreement, but they were virtually identical. The MUHAS, rather than acting as a self-governing body on the provincial level (like Corporation Waskahegen in Quebec), has continued to serve as a collective interest and advocacy organization.

Under the Métis urban social housing agreements, member corporations have greater autonomy, administrative flexibility and decision-making powers than they did under the CMHC agreements. For example, they have been able to negotiate new mortgage terms with lower rates, banking the savings to build a reserve fund for maintenance, new building and associated services. Their operating agreements with the CMHC had required them to transfer any savings back to the province. Maintenance decisions and annual budgets do not need SHC approval, as they did under previous federal agreements; instead, each corporation submits a cash-flow proposal stating how it wishes to receive its yearly subsidy allocation. Annual audits are still required by the province. Individual housing organizations, through their boards of directors, are otherwise able to govern their operations within the parameters of the agreement reached in 2001. Since organizations are able to bank savings achieved through operational efficiencies like finding better rates on work and maintenance, there is an incentive to reduce costs in order to build financial capital for new projects. The agreement ensures, however, that resources are dedicated to housing and related services.

Under the OHT agreement between Canada and Saskatchewan, the SHC must administer calls for proposals, although an agreement has been reached between the SHC and the MUHAS that the Métis pool of funding will go to MUHAS member organizations based on their existing portfolio sizes. The trust allocation is split by the SHC into three funding pools: Métis organizations; First Nations organizations; and the province — that is, the SHC itself — for proposals targeting Aboriginal peoples. Capital improvements to existing housing stock will be the focus of Métis applications to the OHT, although proposals for building new units can be considered for provincial funding. Review committees made up of Métis, First Nations and SHC representatives will advise on the allocation of funds from the provincial pool for building new units.

As they are elsewhere in Canada, units of existing urban Aboriginal housing are gradually coming off subsidy in Saskatchewan. When this occurs, rents rise above the rate of 25 to 30 percent of income to match rents for comparable units in the private market. Each housing organization determines its rate, however, and the goal will still be to provide housing that is on the affordable side of market rents in each city. As one Métis housing manager noted, units coming off subsidy rise from a rent of $300 a month with a utility allowance of $50 per household, to $400 without a utility allowance. This increase will compel those most in need of assistance to search for housing elsewhere — housing that is likely to be not adequate or suitable to their needs.

The working relationship between the MUHAS and the SHC is considered by both parties to be very strong and a considerable improvement over the arrangements that existed prior to the transfer of administrative responsibility for social housing from the federal government to the Province of Saskatchewan. The choice made by the MUHAS with the SHC to use the OHT funding to make capital improvements to existing stock shows the flexibility in implementation planning from province to province. Recall that the Government of Manitoba with its Aboriginal housing stakeholders decided to use the OHT funds for building new stock. New stock is the priority in BC, as well.

The Lu’ma and Kinew cases examined earlier are fine examples of strong local capacity for innovation and leadership, for creating a track record and for advancing quality of life in urban areas on Aboriginal people’s own terms, but in both cases there have been insufficient financial resources to build more than a handful of new housing units. Lu’ma is aggressively pursuing its goal to offer a spectrum of services and programs, ranging from shelters for the homeless and supports to assisted home-ownership opportunities for Aboriginal households, as well as a variety of other services and programs to improve urban quality of life. The organization has also taken on projects such as property management for other clients. Corporation Waskahegen undertakes construction management and offers architectural services to expand its resource base and viability. Increases in housing stock to close the gap between need and availability will nonetheless require significant government investment. The ingenuity of these organizations needs government support.

Aboriginal housing organizations, at both the local and provincial levels, have demonstrated over the past 15 years that they are able to respond innovatively and reliably to the challenges presented by a new housing policy environment. Government financial allocations to low-cost housing (for example, the AHI and the OHT) during this period have not been adequately resourced or directed toward a coherent goaland target-oriented national social housing program. This has stifled the ability of Aboriginal housing organizations to realize the full potential of their program ingenuity or match their activities to the needs of their communities. Looking at the Saskatchewan and Quebec cases, for example, it is

unclear what the federal government will achieve with its OHT funds. In Saskatchewan, they are primarily directed toward improving and maintaining units built under past programs, such as the UNHP. In Quebec, as I have mentioned, the funding at the time of writing had been in the provincial treasury for several months, and no clear indication had been given as to how it would be used for Aboriginal housing — with the exception of the announcement that 50 units will be built in Nunavik, but the funding source for that project was not specifically identified as the OHT. The Saskatchewan and Quebec cases contrast sharply with earlier cases; in the previous era, Aboriginal housing programs had annual building targets for new units, even though target numbers dwindled through the 1980s and early 1990s. In Manitoba and British Columbia, however, the OHT will be used to build new units of Aboriginal housing off-reserve. The number of units will be small, given the total amount of funding, and it is unclear how the program will address the imbalance between need (thousands on waiting lists) and response (short-term financial contribution without targets). All the provinces examined in this report have well-developed capacity in their urban Aboriginal housing sectors. It is still, however, the responsibility of the state to create clear goals and targets for the development of new housing units to meet the needs of Aboriginal urban residents. It has not done so with the OHT.

The pairing of a social investment state with an active civil society in order to achieve housing goals might work effectively in the future (Giddens 1998; Jenson and Saint-Martin 2003), but it will be necessary for the state to provide sufficient financial resources and maintain a coherent national vision based on equity and redistribution among citizens. When the state takes these actions, then the creative and promising advances that are being made at the local level by Aboriginal housing organizations will increase in scale. Governments must provide the policy and resources Aboriginal housing organizations need to build social housing that improves quality of life on Aboriginal people’s own terms — a task that these organizations are far better suited for than government bureaucracies. However, without clearly articulated state social goals and long-term financial commitments, Aboriginal housing organizations are destined to spend their time filling out applications for short-term competitive financing and trying to find partners to add value to project proposals.

Representatives of Aboriginal housing organizations, academics, community advocates, politicians and government officials will need to perform at least two basic but difficult tasks in order to effect real progress in the urban Aboriginal housing sector: they must articulate and implement a return to common social citizenship goals related to housing for all Canadians; and they must articulate and implement a vision of inclusive citizenship based on the understanding that the key to better outcomes is to ensure Aboriginal self-determination in program design, delivery and evaluation.

Aboriginal housing and other community-based organizations are upholding their end of the bargain in state-society relations around housing. Governments must fulfill their responsibilities to improve quality of life through goal-oriented housing policy, with adequate financial resources over a sufficiently long period of time, to allow the ingenuity of local actors to match the scale of need to response.

Alfred, T. 1999. Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto.Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Ark Research Associates. 1996. The Housing Conditions of Aboriginal People in Canada: Summary Report. Ottawa: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Barcham, M.S. 2000. “(De)Constructing the Politics of Indigeneity.” In Political Theory and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, edited by D. Ivison, P. Patton, and W. Sanders. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). 1999. Evaluation of the Urban Social Housing Programs. Ottawa: CMHC.

_____. 2004. “Revised Aboriginal Households.” Research Highlight, 2001 Census Housing Series 6, Socio-economic Series 04-036. Ottawa: CMHC.

Canadian Council on Social Development (CCSD). 1976. Social Housing Policy Review. Ottawa: CCSD.

Cardinal, H. 1969. The Unjust Society: The Tragedy of Canada’s Indians. Edmonton: M.G. Hurtig.

Carter, T., and C. Polevychok. 2004. Housing Is Good Social Policy. Canadian Policy Research Networks (CPRN) Research Report F/50, December. Ottawa: CPRN. Accessed April 29, 2008. https://www.cprn.org/ documents/33525_en.pdf

Chandler, M.J., and C.E. Lalonde. 2004. “Transferring Whose Knowledge? Exchanging Whose Best Practices? On Knowing about Indigenous Knowledge and Aboriginal Suicide.” In Aboriginal Policy Research: Setting the Agenda for Change. V ol. II, edited by J. P. White, P. Maxim, and D. Beavon. Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing.

Connelly Consulting Services. 2003. Guaranteeing a Future: The Challenge to Social Housing as Operating Agreements Expire. Ottawa: Canadian Housing and Renewal Association.

Distasio, J., and G. Sylvester. 2004. First Nations/Métis/Inuit Mobility Study: Final Report, March. Winnipeg: University of Winnipeg, Institute of Urban Studies. Accessed April 29, 2008. https://ius.uwinnipeg.ca/pdf/ Aboriginal%20Mobility%20Final%20Report.pdf

Dunn, J. 2000. “Housing and Health Inequalities: Review and Prospects for Research.” Housing Studies 15 (3): 341-66.

Durie, M.H. 1998. Te Mana Te Kawanatanga: The Politics of Maori Self-Determination. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Fulham, S.A. 1981. In Search of a Future. 4th ed. Winnipeg: Manitoba Métis Federation.

Giddens, A. 1998. The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Green, J. 1997. “Options for Achieving Aboriginal Self-Determination.” Policy Options 18:11-15. Montreal: IRPP. _____. 2005. “Self-Determination, Citizenship, and Federalism as Palimpsest.” In Canada: The State of the Federation 2003: Reconfiguring Aboriginal-State Relations, edited by M. Murphy. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Harvey, D. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Henderson, D.G. 1971. A Second Report on the “Kinew Housing Incorporated” Experiment. Winnipeg: University of Winnipeg, Institute of Urban Studies.

Hulchanski, J.D. 2002. Housing Policy for Tomorrow’s Cities. Canadian Policy Research Networks (CPRN) Discussion Paper F/27, December. Ottawa: CPRN. Accessed April 29, 2008. https://www.urbancentre.utoronto.ca/pdfs/ elibrary/CPRNHousingPolicy.pdf

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC). 2006. “Accountability and Reporting to Canadians.” In Operating Principles for the Off-Reserve Aboriginal Housing Trust. Ottawa: INAC.

Inner City Housing Coalition (ICHC). 2000. Inner City Housing Policy Platform: Federal Election. Winnipeg: ICHC.

Jenson, J., and D. Saint-Martin. 2003. “New Routes to Social Cohesion? Citizenship and the Social Investment State.” Canadian Journal of Sociology 28 (1): 77-99.

Jessop, B. 2000. Good Governance and the Urban Question: On Managing the Contradictions of Neo-liberalism . Lancaster, UK: Lancaster University, Department of Sociology. Accessed April 29, 2008. https://www.lancs. ac.uk/fass/sociology/papers/jessop-good-governance-and-the-urban-question.pdf

_____. 2001. “Bringing the State Back in (Yet Again): Reviews, Revisions, Rejections, and Redirections.” International Review of Sociology 11 (2): 149-73.

Kemeny, J. 2001. “Comparative Housing and Welfare: Theorising the Relationship.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 16 (1): 53-70.

Lipman, M. 1986. “Historical Review of CMHC’s Urban Native Housing Activity.” In Urban Native Housing in Canada, Institute of Urban Studies Research and Working Paper 19, by M. Lipman and C. Brandt. Winnipeg: University of Winnipeg, Institute of Urban Studies.

Maaka, R., and A. Fleras. 2005. The Politics of Indigeneity: Challenging the State in Canada and Aotearoa New Zealand. Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago Press.

Minore, B., and M. Katt. 2007. “Aboriginal Health Care in Northern Ontario: Impacts of Self-Determination and Culture.” IRPP Choices 13 (6).

Moore, E., and A. Skaburskis. 2004. “Canada’s Increasing Housing Affordability Burdens.” Housing Studies 19 (3): 395-413.

Norris, M.J., and S. Clatworthy. 2003. “Aboriginal Mobility and Migration within Urban Canada: Outcomes, Factors and Implications.” In Not Strangers in These Parts: Urban Aboriginal Peoples,edited by D. Newhouse and E.J. Peters. Ottawa: Policy Research Initiative.

Peters, E.J. 1992. “Self-Government for Aboriginal People in Urban Areas.” Canadian Journal of Native Studies 12 (1): 51-74.

Pomeroy, S. 2004. A New Beginning: The National Non-reserve Aboriginal Housing Strategy . Ottawa: National Aboriginal Housing Association.

_____. 2006. Was Chicken Little Right? Case Studies on the Impact of Expiring Social Housing Operating Agreements. Ottawa: Canadian Housing and Renewal Association.

Ralston Saul, J. 2005. The Collapse of Globalism and the Reinvention of the World. Toronto: Penguin Books.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. 1996a. “Urban Perspectives.” In Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Vol. 4, chap. 7. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services.

_____. 1996b. “Housing.” In Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Vol. 3, chap. 4. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services.

Salée, D., D. Newhouse, with the assistance of C. Lévesque. 2006. “Quality of Life of Aboriginal People in Canada: An Analysis of Current Research.” IRPP Choices 12 (6).

Shapcott, M. 2006. “Building Relations with the New Federal Government.” Paper presented at the National Aboriginal Housing Association conference, June, Vancouver.

Simms, T., and E. Tanner. 2004. “The Centennial Neighbourhood Project, Winnipeg.” Paper presented at the National Aboriginal Housing Association conference, June, Vancouver.

Skelton, I. 2002. “Residential Mobility of Aboriginal Single Mothers in Winnipeg: An Exploratory Study of Chronic Moving.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 17 (2): 127-44.

Statistics Canada. 2003. Initial Findings of the 2001 Aboriginal Peoples Survey: Housing and Water Quality. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services.

_____. 2008. Aboriginal Peoples in Canada in 2006: Inuit, Métis and First Nations, 2006 Census. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Stewart, P.R. 2007. “Art Zoccole Aboriginal Patients’ Lodge.” Paper presented at the Canadian Institute of Planners annual conference, June, Quebec City.

Toronto Mayor’s Homelessness Action Task Force. 1999. Taking Responsibility for Homelessness: An Action Plan for Toronto. Toronto: City of Toronto.

Walker, R.C. 2003. “Engaging the Urban Aboriginal Population in Low-Cost Housing Initiatives: Lessons from Winnipeg.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research 12 (1): 99-118.

_____. 2008. “Aboriginal Self-Determination and Social Housing in Urban Canada: A Story of Convergence and Divergence.” Urban Studies 45 (1): 185-205.

Walker, R., J. Ballard, and C. Taylor. 2003. Developing Paradigms and Discourses to Establish More Appropriate Evaluation Frameworks and Indicators for Housing Programs. Perth: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

Walker, R.C., and M.S. Barcham. 2007. “Understanding Indigenous Urban Housing Outcomes.” Centre for Indigenous Governance and Development (CIGAD) Briefing Notes, March. Palmerston North, NZ: Massey University, CIGAD. Accessed April 29, 2008. https://cigad.massey.ac.nz/documents/Briefing%20 Notes%201_2007.pdf

_____. 2008. Comparative Analysis of Urban Indigenous Housing in Canada, New Zealand and Australia. Ottawa: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, National Aboriginal Housing Association.

Walks, R.A. 2006. “Homelessness, Housing Affordability, and the New Poverty.” In Canadian Cities in Transition: Local through Global Perspectives. 3rd ed., edited by T. Bunting and P. Filion. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Wherrett, J. 1999. Aboriginal Self-Government. Current Issue Review 96-2E. Ottawa: Parliamentary Research Branch. Accessed April 29, 2008. https://www.parl. gc.ca/information/library/PRBpubs/962-e.htm

Wilson, K.J. 2000. “The Role of Mother Earth in Shaping the Health of Anishinabek: A Geographical Exploration of Culture, Health and Place.” Ph.D. diss., Queen’s University.

Wolfe, J. M. 1998. “Canadian Housing Policy in the Nineties.” Housing Studies 13 (1): 121-33.

This publication was produced under the direction of F. Leslie Seidle, Senior Research Associate, IRPP. The manuscript was copy-edited by Mary Williams, proofreading was by Francesca Worrall, production was by Chantal Létourneau, art direction was by Schumacher Design and printing was by AGL Graphiques.

Copyright belongs to IRPP. To order or request permission to reprint, contact:

IRPP

1470 Peel Street, Suite 200

Montreal, Quebec H3A 1T1

Telephone: 514-985-2461

Fax: 514-985-2559

E-mail: irpp@nullirpp.org

All IRPP Choices and IRPP Policy Matters are available for download at irpp.org

To cite this document:

Walker, Ryan. 2008. “Social Housing and the Role of Aboriginal Organizations in Canadian Cities.” IRPP Choices 14 (4).

Ryan Walker is an assistant professor of planning and geography at the University of Saskatchewan. Originally from Winnipeg, he has studied at the University of Lethbridge (BA), the University of Waterloo (MA) and Queen’s University (Ph.D.). One of his research interests is the comparative study of Aboriginal housing in urban areas across Canada, New Zealand and Australia.