L’encadrement du pouvoir de dépenser du gouvernement fédéral dans les domaines relevant de la compétence des provinces — les politiques sociales, en particulier — était à l’ordre du jour de la plupart des négociations constitutionnelles qui ont eu lieu à partir de la fin des années 1960. L’enjeu revêtait une importance toute particulière pour le Québec, mais d’autres provinces critiquaient également la façon dont le pouvoir de dépenser avait été utilisé dans le passé. Tous les gouvernements avaient accepté qu’il soit assujetti à certaines limites dans les accords du lac Meech et de Charlottetown, mais le rejet de ce dernier en 1992 a mis fin aux tentatives visant à imposer des limites constitutionnelles au pouvoir de dépenser.

Au cours de la campagne électorale de 2006, le Parti conservateur a promis d’adopter une approche axée sur le « fédéralisme d’ouverture » dans ses relations avec les provinces. C’est dans ce contexte que la question du pouvoir de dépenser est revenue à la surface : dans le discours du Trône de 2007, le gouvernement fédéral a annoncé qu’il entendait présenter un projet de loi visant à limiter le recours à cet instrument pour les nouveaux programmes à frais partagés touchant les domaines relevant de la compétence exclusive des provinces. C’est ce qui a amené l’IRPP à commander deux études sur le sujet et à organiser une table ronde, qui s’est tenue à Ottawa le 12 juin 2007.

Cette rencontre a réuni des universitaires, des hauts fonctionnaires et des représentants de plusieurs organismes nationaux actifs dans les secteurs de la santé, de l’enseignement postsecondaire et d’autres domaines de politique sociale. Hamish Telford et Peter Graefe ont présenté des versions préliminaires de leurs études respectives, tandis que Keith Banting y a joué le rôle de rapporteur des débats.

Comme le gouvernement Harper n’a pas déposé de projet de loi avant de déclencher l’élection de 2008, la question de l’ampleur du pouvoir de dépenser n’est toujours pas résolue. L’IRPP espère que la présente publication apportera un éclairage nouveau sur toute tentative visant à en restreindre l‘utilisation à l’avenir. Les études de Telford et de Graefe abordent également des questions plus générales qui se répercutent sur les relations intergouvernementales, y compris les moyens employés par Ottawa pour influencer les politiques et les programmes sociaux, et le rôle que jouent les processus intergouvernementaux à cet égard.

Dans son étude, Hamish Telford examine d’abord le fondement des démarches visant à restreindre le pouvoir de dépenser. Il évoque deux théories de la citoyenneté qui aident à comprendre pourquoi cette question continue de soulever la controverse. Les gouvernements qui se sont succédés au Québec ont considéré le pouvoir de dépenser comme une intrusion compromettant les efforts de la province en vue de préserver le caractère singulier du Québec au sein de la fédération canadienne, tandis que le gouvernement fédéral s’en est servi pour favoriser l’application universelle de la citoyenneté, ce que Telford appelle universality of citizenship. Il examine deux options qui pourraient concilier ces positions opposées : 1) l’insertion dans la Constitution d’une « charte sociale », qui éliminerait la nécessité pour le gouvernement fédéral de se servir de son pouvoir de dépenser pour promouvoir l’application universelle de la citoyenneté ; 2) un accord intergouvernemental aux termes duquel le Québec pourrait se retirer des programmes à frais partagés et recevoir une compensation inconditionnelle. Il est peu probable, estime Telford, que le gouvernement fédéral se fasse le promoteur de l’une ou de l’autre dans un avenir prévisible, de sorte que la question de l’imposition de limites au pouvoir de dépenser risque de rester sans solution.

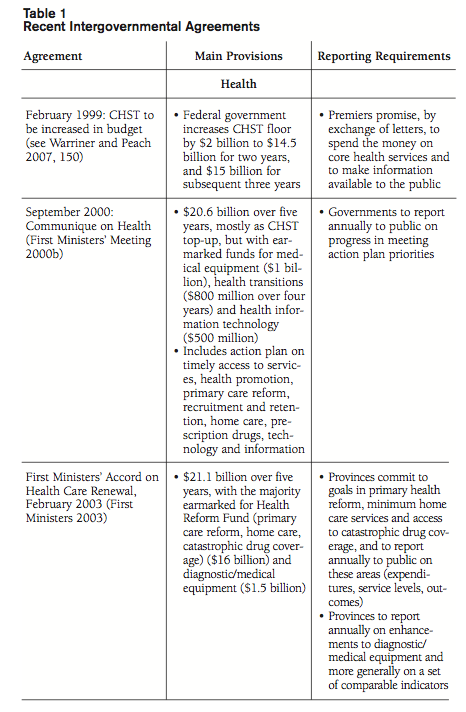

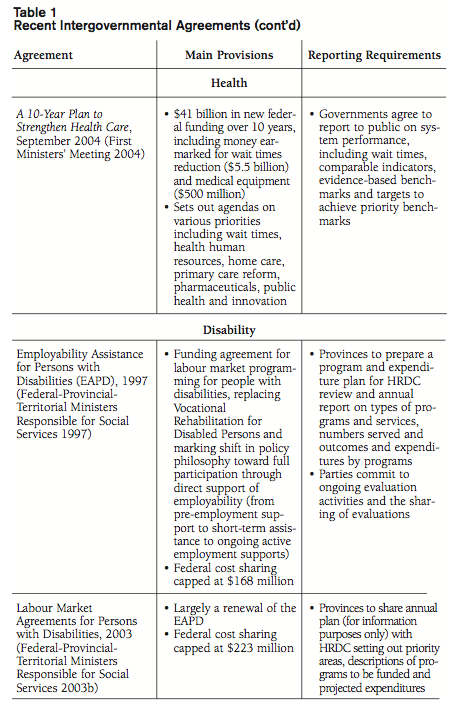

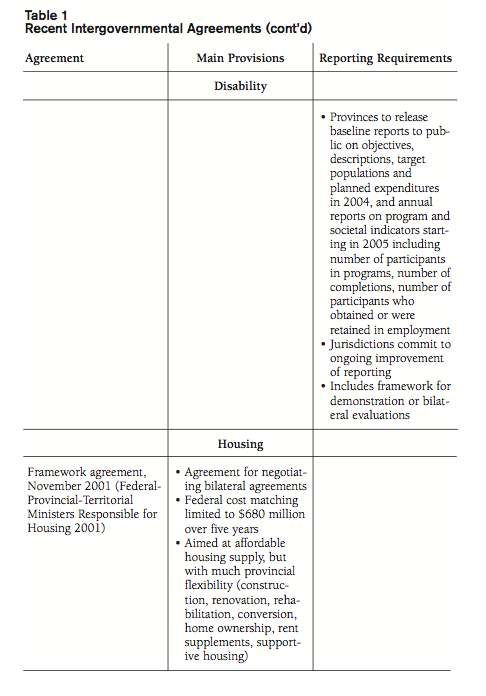

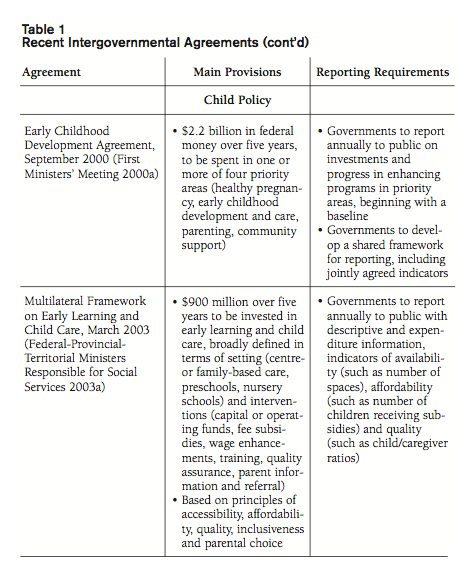

Peter Graefe rappelle lui aussi l’engagement pris dans le discours du Trône de 2007 et conclut que si cette proposition avait été mise en pratique, elle n’aurait pas changé grand-chose, car il est difficile de trouver même une seule initiative prise par le gouvernement fédéral au cours du dernier quart de siècle qui correspond aux critères envisagés. L’étude de Graefe examine le leadership exercé par Ottawa dans le domaine des politiques sociales et constate que le fédéral privilégie aujourd’hui les transferts directs aux particuliers et aux organisations, au détriment des programmes à frais partagés. Au niveau des relations intergouvernementales, Ottawa demande depuis plusieurs années que les provinces s’engagent à élaborer des indicateurs sociaux communs, à s’échanger des renseignements sur les pratiques les plus efficaces et à faire rapport à leurs populations respectives. Certains nationalistes québécois continuent de considérer les initiatives fédérales trop intrusives, tandis que les partisans de la centralisation jugent qu’Ottawa a perdu une part importante de l’influence qu’il devrait pouvoir exercer, compte tenu des montants transférés. L’auteur termine en montrant comment les processus intergouvernementaux pourraient être modifiés à la lumière de ces critiques, notamment en accentuant la dimension asymétrique des programmes en faveur du Québec et en mettant en place des lieux de rencontre plus efficaces pour la mise en commun des priorités et des innovations.

Finalement, dans la dernière partie, on peut lire le compte rendu de la table ronde préparé par Keith Banting. Ce texte s’inspire du sommaire très perspicace que Banting a présenté à la fin de la rencontre. En plus de résumer les débats qui ont suivi les exposés de Telford et de Graefe (chacun avait fait l’objet d’une séance distincte), Banting commente l’allocution liminaire prononcée par le sénateur Hugh Segal. Banting articule ses observations autour de quatre questions : 1) Y a-t-il vraiment un problème ? 2) Quels critères faut-il utiliser pour faire un choix ? 3) Quelles options se présentent à nous ? 4) Quelles sont les perspectives de changement ? En réponse à cette dernière question, Banting décrit les conclusions générales de la discussion dans les termes suivants : si le gouvernement du Québec n’appuie pas la législation proposée par le gouvernement fédéral, il est peu probable qu’une telle loi accroisse la légitimité du fédéralisme au Québec ; une proposition qui irait au-delà de l’engagement pris en faveur des provinces dans le discours du Trône risquerait de déclencher une forte opposition parmi les défenseurs du rôle du gouvernement fédéral dans le reste du pays. C’est pourquoi, conclut Keith Banting, la recherche d’une formule qui aiderait à concilier les points de vue d’un bout à l’autre du pays continue de poser un défi qu’il sera difficile de surmonter.

The spending power has been one of the most intractable problems in Canadian federalism over the past half-century. The dispute over its constitutionality and political legitimacy has been waged primarily by the governments of Canada and Quebec. This study argues that the dispute stems from two different conceptions of the federal principle and, ultimately, two theories of citizenship. In brief, the government of Quebec has resisted the spending power in the name of provincial autonomy and from a desire to promote the province’s particularity, while the government of Canada has employed the spending power to facilitate the universality of citizenship. Historically, efforts to address the problem politically have been less than satisfactory, while all attempts to resolve it constitutionally have failed.

The Conservative government led by Stephen Harper promised to place statutory limits on the spending power as part of its program of open federalism. The study argues that this prescription – as it was articulated by the Harper government – will not go far enough to satisfy the government of Quebec, and it may not do enough to reassure Canadians outside Quebec that the government of Canada is still committed to the universality of citizenship.

The last section of the study advances two alternative schemes to resolve the problem of the spending power. The first is a constitutionally entrenched “social charter,” which would effectively terminate the need for the federal government to employ the spending power to achieve the universality of citizenship, while still reassuring all citizens that the governments of Canada are still committed to the social programs that materially support the idea of universal citizenship. The second is a suggestion that the federal and provincial governments of Canada formulate an agreement under which Quebec would be afforded the right to opt out of shared-cost social programs with unconditional compensation, thereby ensuring Quebec’s political autonomy.

The study concludes that neither of these options is likely to be embraced by the government of Canada in the foreseeable future, thus ensuring that the problem of the spending power will continue for quite some time yet.

In its 2006 election platform, the federal Conservative Party promised a new era of open federalism. After years of intergovernmental conflict over transfer payments (not to mention the sovereignty referendum, the secession reference case, the Clarity Act, and the Social Union Framework Agreement), the Conservatives promised to establish a more harmonious relationship with the provinces, “while clarifying the roles of both levels of government within the division of powers of the Constitution” (Conservative Party of Canada 2006, 42). More specifically, the Conservatives promised to move toward an elected Senate, grant the provinces a role in foreign affairs (when their jurisdiction was affected), rectify the “fiscal imbalance,” fix the equalization program and limit the spending power by ensuring that “any new shared-cost program in areas of provincial/territorial responsibility have the consent of the majority of provinces to proceed, and that provinces should be given the right to opt out of the federal program with compensation, so long as the province offers a similar program with similar accountability structures” (43). Although the concept of open federalism was fairly vague, it was a carefully crafted double entendre, designed to resonate with Quebec’s historical demands for recognition and autonomy (Noël 2006), while sounding fresh and positive to the rest of the country (R. Young 2006).1 The Conservatives’ program for reshaping the federation had no impact in most provinces, but it helped the party win 10 seats in Quebec, enabling it to eke out a minority government.

Now that the Conservatives have completed their first term of office, what is the status of open federalism? The record is mixed. Prime Minister Stephen Harper has been extremely wary about meeting with the premiers — he has met them collectively only twice for working dinners at 24 Sussex2 — and he has openly feuded with some, notably Danny Williams of Newfoundland and Labrador and Dalton McGuinty of Ontario, and there have been tensions at times with others as well. While the Prime Minister is not solely responsible for these disputes, this level of animus is presumably not what the premiers expected when the Conservatives promised in their 2006 election platform to “establish a new relationship of open federalism with the provinces” (2006, 42). Yet the Harper government introduced a historic motion in the House of Commons in November 2006 recognizing that “the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada”;3 it also introduced legislation to reform the Senate.4

On the fiscal front, the new Conservative government pledged in the 2006 budget to honour the 10-year plan for stable federal health transfers negotiated by the previous Liberal government of Paul Martin, and in the 2007 budget it revamped the equalization program largely in accordance with the recommendations advanced by the Expert Panel on Equalization and Territorial Financing appointed by the Martin government. These measures entitled Finance Minister James Flaherty to boast that the Conservative government had delivered “an historic plan worth over $39 billion in additional funding to restore fiscal balance in Canada,” although he obviously got carried away when he declared that “the long, tiring, unproductive era of bickering between the provincial and federal governments is over” (2007, 2). In the October 2007 Throne Speech, the Harper government announced its intention to advance open federalism further with the introduction of statutory limits on “the use of the federal spending power for new shared cost programs in areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction. This legislation will allow provinces and territories to opt out with reasonable compensation if they offer compatible programs” (Government of Canada 2007).

The spending power has been one of the most contentious issues in Canadian politics over the past half-century, and solutions for it have been elusive. Although the term is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution Act, 1867, the federal government historically has maintained that the spending power provides it with the authority to extend grants to the provinces to create and support programs that are matters of exclusive provincial jurisdiction. In this manner, the federal government was able to initiate a health care system with “national” standards, as well as a variety of assistance programs and support to families, among other things. Canadians cherish these programs. Quebec, however, has never accepted the constitutionality of the spending power, and it has long sought to limit — not to abolish — its use, at least with respect to that province.

The dispute over the spending power stems from two different conceptions of federalism espoused by the federal government and Quebec and ultimately two theories of citizenship. Many Canadians outside Quebec believe that “national” social programs are an integral element of universal citizenship. Many Quebecers, however, view the pursuit of universal citizenship, in part through the creation of social programs established with the spending power, as a threat to their particularity — their language, culture and political identity.5 In short, the debate over the spending power has frequently been viewed as a zero-sum game: universality at the expense of particularity or particularity at the expense of universality.6 The Conservatives’ plan to place statutory limits on the spending power does not adequately address the concerns of Quebecers or the majority of Canadians outside Quebec, and as such it likely will not be viewed as a lasting solution to the problem by either solitude.7

The last part of this study considers various options for resolving the spending power issue. In general, there are two options: constitutional and nonconstitutional. Nonconstitutional options — such as intergovernmental agreements, parliamentary resolutions or federal legislation — are easier to obtain, but generally are not viewed by Quebec as sufficient safeguards for its particularity. Constitutional options are more likely to meet Quebec’s concerns, but they are more difficult, if not impossible, to obtain, largely because they are viewed by many Canadians outside Quebec as a threat to universal citizenship. The federal government’s promise to introduce legislation to place statutory limits on the spending power is the most robust nonconstitutional option for resolving this long-standing issue, but it is still unlikely to achieve broad support in Quebec; even the Quebec Liberal Party ultimately would like to see limits on the spending power placed in the Constitution. At the same time, some Canadians outside Quebec fear that the legislation is a threat to social programs. I attempt to determine if there is any possibility for a mutually satisfactory agreement between the two solitudes on the spending power.

The debate over the spending power stems from two very different conceptions of federalism, both of which were forcefully articulated in the Confederation debates. Sir John A. Macdonald — anxious to avoid the perceived “defects” of the US constitution — was determined to ensure that the federal government would have sufficient powers to prevail over the provinces. In Canada, he said, “we have strengthened the General Government. We have given the General Legislature all the great subjects of legislation…We have thus avoided that great source of weakness which has been the cause of the disruption of the United States” (Parliamentary Debates 1865, 33). With respect to the division of powers, Macdonald explained that “all matters of general interest are to be dealt with by the General Legislature; while the local legislatures will deal with matters of local interest, which do not affect the Confederation as a whole, but are of the greatest importance to their particular sections” (30). Here, Macdonald seemed to imply that the federal powers are circumstantial: if “local” matters take on a “general” importance at some point in the future, they would become matters of legitimate concern for the federal Parliament.

This interpretation of the division of powers was later advanced by some very prominent constitutional scholars, particularly in the 1930s. For Frank Scott, a “clear and definite” conception of the division of powers emerged from the Confederation debates: “The basis for the distribution of legislative powers was to be this — all matters of national importance were to go to the national parliament, all matters of merely local importance in each province were to remain subject to exclusive provincial control” (Scott 1977, 36).8 Elaborating, he added, “The effect of these clauses will be that beyond the subjects attributed to each, the central legislature will have jurisdiction over all general matters, whatever they are, and the local legislatures over all local matters, whatever they are. The specifically enumerated powers in each case are examples merely of the sort of power contained in the residues” (38-9). Scott maintained that this was universally understood by all participants in the debate: “Both the opponents and the supporters of Confederation agreed upon what sort of federal arrangement was being made; they differed only about the outcome and the value of the arrangement” (36). While Scott’s interpretation of the division of powers is theoretically plausible — it certainly has been embraced by Ottawa — his characterization of the Confederation debate is overly simplistic. It was a considerably more complex affair, with supporters and opponents of Confederation motivated by different concerns and interpretations of the proposed Constitution.

Antoine Aimé Dorion was the leading opponent of Confederation, and he was adamant that the proposed scheme was unacceptable to Quebec. In the Confederation debates, he was scathing in his condemnation of the proposed Constitution: “The whole scheme, sir, is absurd from beginning to end,” he scoffed (Parliamentary Debates 1865, 255). He was primarily concerned with the broad residual power afforded to the federal government: “I find that the powers assigned to the General Parliament enable it to legislate on all subjects whatsoever…because all the sovereignty is vested in the general government” (689). As such, he argued, Parliament would be able to “trespass upon the rights of the local government without there being any authority to prevent [it]” (690). While Dorion rejected the proposed Constitution for the same reasons that Macdonald supported it, other Quebecers endorsed it because they believed that the interpretation advanced by Macdonald and Dorion was wrong.

One of the strongest supporters of the Constitution was Joseph Cauchon, a government backbencher and “one of the most powerful Conservative figures in Quebec” (Vipond 1991, 34), but he utterly rejected Macdonald’s interpretation of the division of powers. Under the Constitution, he argued,

there will be no absolute sovereign power, each legislature having its distinct and independent attributes, and not proceeding from one or the other by delegation, either from above or from below. The Federal Parliament will have legislative sovereign power in all questions submitted to its control in the Constitution. So also the local legislatures will be sovereign in all matters which are specifically assigned to them. (Parliamentary Debates 1865, 697)

In this conception of federalism, the responsibilities of the provinces are not dependent on external circumstances; they are contractually allocated to the provinces unless and until they are transferred to the federal realm by formal amendment of the Constitution. In this interpretation of the division of powers, the federal government cannot involve itself in matters that have been assigned by the Constitution “exclusively” to the provincial legislatures, irrespective of how important those matters might become over time. This theory of federalism has become an article of faith for successive Quebec governments. It offers a stronger guarantee that the province will possess the powers that are essential to ensure its cultural particularity and that it will not be overwhelmed by an expansionary federal government supported by the majority community in the federation.

Although the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, the highest court of the British Empire, seemingly endorsed Cauchon’s theory of federalism in a succession of judgments running from the 1880s to the 1930s, these mutually exclusive theories of federalism have continued to reverberate through Canadian politics as if these judgments had never been made. They were certainly on display when the issues of hospital and health insurance were being debated in the 1950s and 1960s, along with most of the other shared-cost programs that constituted the postwar social union. At the October 1955 federal-provincial conference, Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent stated that health insurance “is a matter, of course, which under our constitution falls squarely within provincial jurisdiction,” but, he argued, “there may be circumstances in which it would be justified” for the federal government “to assist provincial governments in implementing health insurance plans designed and administered by the provinces” (Conference of Federal and Provincial Governments 1955, 9). Under what circumstances would federal involvement in provincial jurisdiction be justified? “In the view of the Federal government,” St-Laurent answered, “the condition prerequisite to federal support of provincial programmes in respect of health insurance is that it can reasonably be shown that the national rather than merely or local section interest is thereby being served” (11). For St-Laurent, if a “substantial majority of provincial governments, representing a substantial majority of the Canadian people,” were in favour of federal involvement in the establishment of a provincially administered system of health insurance, he would conclude that the matter was in the now in the national interest and no longer merely local (11).

Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis reacted angrily to St-Laurent’s proposals. Like Cauchon, Duplessis argued that “the Canadian constitution consecrates the exclusive right of the provinces to legislate respecting matters of very great importance, notably in regards to education, hospitals, asylums, institutions and charitable homes, public works within the province, administration of justice and all which touches on property and civil rights” (Conference of Federal and Provincial Governments 1955, 38), and he insisted that the “federal authority and the provincial authority are both sovereign within the limits of their attributions” (36). In closing, he stressed the link between legislative and fiscal autonomy: “Of what use would it be for the provinces to have the right to build schools and hospitals,” he asked rhetorically, “if they are dependent on another authority in order to obtain the necessary funds? Their sovereignty with respect to education and hospitalization would be meaningless” (36). It has been suggested that Quebec’s decision to introduce a personal income tax in 1954 “had everything to do with creating a source of taxation revenues in order to thwart the exercise of the federal spending power” (Courchene 2008, 5; emphasis in original).

Notwithstanding Duplessis’ objections, Health Minister Paul Martin Sr. announced the federal government’s proposed hospital insurance plan in January 1956. Ottawa offered to pay for half the cost of a province’s hospital services, on the condition that the services be universally available to all citizens of the province (Taylor 1978, 217). British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Alberta accepted the proposal immediately and, in March 1957, after much hard bargaining, so did Ontario and Newfoundland. With half the provinces on board, the Hospital Insurance and Diagnosis Services Act was presented to Parliament in April 1957. John Diefenbaker brought the plan into effect on July 1, 1958. Newfoundland and the four western provinces initiated their hospital insurance plans on that date; Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia followed in January 1959; Prince Edward Island joined in October 1959; and Quebec began its hospital insurance scheme in January 1961 (2334). In 1966, Ottawa passed the Medical Care Act, which provided Canadians comprehensive health insurance. It took effect on July 1, 1968, with only Saskatchewan and British Columbia on board. “Unlike the case of hospital insurance,” interestingly, “there was no minimum requirement of a majority of provinces agreeing to the program before federal contributions could be made” (M. Taylor 1987, 374-5). Quebec did not join the scheme until November 1970, after it became apparent that the province would not be able to opt out with compensation even though it was committed to operating a comparable program. While the provinces were free to reject federal transfers, there was a political imperative to accept them, as Premier Jean-Jacques Bertrand explained when Quebec decided to accept the Act: “Either Quebec joins the programme, and thus flies squarely in the face of the Canadian constitution, or else we do not join up and thus deprive our people of a lot of money to which they have the right. What does one do in a case like this?” (Quebec 1998, 18). While Quebec accepted transfers for health, it continued to reject the constitutionality of conditional federal grants.

As the federal government proceeded to create the postwar welfare state, it recognized that it had a political problem with Quebec, but it was not moved by Quebec’s objections. After the war, Ottawa was anxious to establish new social programs to avoid the dislocation that had occurred during the Great Depression. The federal government’s plans were detailed in a series of documents known as the Green Books. “In familiar terms,” the government declared, “our objectives are high and stable employment and income, and a greater sense of public responsibility for individual economic security and welfare. Realization of these objectives for all Canadians, as Canadians, is a cause in which we would hope for national enthusiasm and unity” (DominionProvincial Conference on Reconstruction 1945, 7). Ottawa acknowledged that many of its proposed initiatives fell in areas of provincial jurisdiction, but it suggested ambiguously that the “division of responsibilities should not be permitted to prevent any government, or governments in co-operation, from taking effective action” (8).

The federal proposals were discussed with the provinces at conferences on reconstruction in 1945 and 1946. The conferences “had to decide,” Keith Banting has written, “whether there would be a panCanadian welfare state or a series of distinctive provincial welfare states. The social union that emerged in those years was a compromise between these two poles” (1998, 40; emphasis in original). While the federal government championed a pan-Canadian welfare state, it was forced to retreat in the face of stiff opposition from Maurice Duplessis and the government of Quebec, as well as from some other provinces. When the Conference on Reconstruction ended in failure, Ottawa decided to pursue its policy objectives incrementally. It eventually secured the “cooperation” of the provinces with strong fiscal incentives — usually 50-50 cost sharing. This was the era of cooperative federalism, although it was more like “follow-the-leader” federalism: intrinsically hierarchical. The Duplessis government objected to almost every element of the new social union, but the federal government simply dismissed him as a reactionary. As far as Ottawa was concerned, justice required the establishment of robust social programs that would ensure a reasonable measure of vertical and horizontal equity across the federation.

Although the federal government found it easy to dismiss Duplessis, it was more difficult to ignore similar complaints from Jean Lesage, a progressive Liberal and former federal cabinet minister; the pressure increased when Daniel Johnson and the Union Nationale won the 1966 provincial election. Under relentless demands by successive Quebec governments to provide a constitutional justification for conditional grants, the Trudeau government advanced the doctrine of the spending power. Indeed, Trudeau defined the spending power for the very first time as “the power of Parliament to make payments to people or institutions or governments for purposes on which it [Parliament] does not necessarily have the power to legislate” (1969, 4). Simply put, the federal government claimed that an unlimited power to spend was a natural corollary of its unlimited power under the Constitution to raise revenue “by any mode or system of taxation,”9 even though this argument was seemingly refuted by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the 1937 Employment and Social Insurance Act reference case, and arguably was not consistent with Trudeau’s own writings on the subject before he entered politics (Trudeau 1968). Ever since the federal government unilaterally defined the spending power, its constitutionality has been debated vigorously by academics and governments alike.10

As prime minister, Trudeau justified the spending power as being in the general interest of the federation, just as St-Laurent had done with hospital insurance. Trudeau reasoned that “because the people of Canada will properly look to a popularly elected Parliament to represent their national interests, it should play a role with the provinces, in achieving the best results for Canada from provincial policies and programmes whose effects extend beyond the boundaries of a province” (Trudeau 1969, 34; emphasis in original). While Trudeau accepted that Parliament could not legislate on matters of exclusive provincial jurisdiction, he insisted that it could spend money on such matters if it deemed them to be in the “general” interest of the federation. Trudeau’s defence of the spending power was entirely consistent with Macdonald’s circumstantial theory of the division of powers and completely inimical to Quebec’s contractual understanding of the federal principle.

Quebec’s theory of federalism is inspired by its desire to maintain its particularity. When the federal government spends money in areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction — either directly on individuals or through provincial governments with conditional grants — Quebec believes that its ability to protect its particularity is jeopardized. Quebec’s opposition to the spending power is thus fundamental. For the other provinces, the primary concerns are that the spending power can distort provincial policy priorities and the reliability of the federal government as a fiscal partner. These problems can be handled through effective intergovernmental relations, and since the late 1990s the provinces have tried to engage Ottawa in a more horizontal form of collaborative federalism (Cameron and Simeon 2002). Jean Chrétien refused to enter into a partnership of equals with the provinces, but Stephen Harper showed a receptiveness to it when he called for a more “open” form of federalism with the provinces.

The dispute over the spending power entails more than the definition of federalism. Ultimately, the debate stems from two distinct conceptions of citizenship and two associated theories of justice. In the latter half of the twentieth century, Canadians came to value the redistributive policies of the social welfare state, premised on a particular conception of equality, and to embrace cultural diversity in the form of official bilingualism and recognition of multiculturalism. Indeed, for many Canadians outside Quebec, these principles constitute core elements of universal citizenship. The universality of citizenship, however, may undermine particularity if care is not taken to protect minority groups. Because the intent of universal citizenship is positive, many Canadians outside Quebec cannot grasp how threatening it can be — but it is probably not coincidental that the sovereignist Parti Québécois was formed after Quebec had vigorously resisted the social policies the federal government had advanced (through the spending power) for more than two decades. While most Quebecers support the principles of redistributive justice, Quebec has (implicitly) advanced a theory of differentiated citizenship, which places greater emphasis on the preservation of the particularities of minority groups. This notion of citizenship has not been well received outside Quebec, because it appears to contradict the conception of equality on which the universal conception of citizenship is premised. Most Quebecers and many Canadians outside Quebec want to see a high degree of redistributive justice and the preservation of cultural differences, but they balance these values differently. If there is to be a solution to the spending power, it will have to balance these values to the satisfaction at least of political majorities in each community.

Citizenship in liberal societies initially was premised on a set of civil rights, such as life, liberty and the protection of private property. The freedoms initially ensured by the liberal state were essentially negative: the state promised not to interfere with a man’s thoughts, beliefs, religion or ability to express himself. This was freedom from the state, and as this sort of freedom had never been enjoyed before, liberal citizenship was inherently progressive, even though it was restricted initially to property-owing men. As that political class possessed comparable financial means, the liberal state felt no obligation to provide anyone the means to realize a good life or the freedom to do things — also known as “positive” liberty (Berlin 1969). As equality was self-evident, the state’s only obligation was to apply the laws of the land to each citizen in the same way so as not to provide anyone an unfair advantage. This was the principle of procedural equality, and at a time when most states routinely played favourites with their subjects, it too was a progressive development.

While liberal citizenship was progressive, its exclusionary nature was difficult to reconcile with the belief that, as the US Declaration of Independence puts it, certain “truths” were “self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Very slowly, over time, women and minorities were granted civil and political rights — in other words, liberal citizenship was made universal. Unfortunately, the Great Depression made the idea of universal citizenship based only on civil and political rights look hollow. With the realization of universal citizenship, citizens no longer had comparable means. As such, the liberal state was required to take positive measures to ensure that all citizens possessed at least the basic means for subsistence. After the Second World War, social programs were introduced to provide some substantive meaning to the idea of universal citizenship. This gave rise to the notion that citizens should possess social rights alongside civil and political rights (Marshall 1950). In Canada, the federal government stated explicitly in the Green Books that it hoped social security, including health care, “would make a vital contribution to the development of our concept of Canadian citizenship and to the forging of lasting bonds of Canadian unity” (DominionProvincial Conference on Reconstruction 1945, 28).

The inclusion of all individuals was clearly an advancement in the history of citizenship, but it was also more problematic than most people anticipated. The principles of citizenship that had existed for more than two centuries prior to the realization of universal citizenship — negative liberty and procedural equality — were premised on a culturally homogeneous society of property-owning men, not a heterogeneous society of men and women, rich and poor, and a multiplicity of cultural groups. In a heterogeneous society, if the state applies one standard for all in its application of the law, those with more means likely will benefit more from the state than those with less. In other words, the principle of procedural equality serves to perpetuate the advantage held by some. Any attempt to differentiate among citizens, however, raises concerns that the state is deviating from its commitment to equality. More fundamentally, the objective of universal citizenship is to “turn” the people into “one”: it is inherently assimilationist, which was not an issue when the political class was culturally and economically homogeneous, but it is problematic in a heterogeneous society. The assimilationist tendencies of universal citizenship are further exacerbated if social justice is comprehended exclusively in redistributive terms.

Iris Marion Young has argued that, in heterogeneous liberal societies, universal citizenship should give way to a differentiated conception of citizenship. She contends, “Modern political thought generally assumed that the universality of citizenship in the sense of citizenship for all implies a universality of citizenship in the sense that citizenship status transcends particularity and difference” (I. Young 1989, 250). While Young clearly supports an inclusive conception of citizenship, she maintains that the pursuit of universality through redistributive justice has tended to favour generality over particularity, often to the disadvantage of minority groups. As such, she argues, “where social group differences exist and some groups are privileged while others are oppressed, social justice requires explicitly acknowledging and attending to those group differences in order to undermine oppression” (1990, 3). Young does not want to forgo redistributive justice, but she very much wants to ensure the cultural particularities of a heterogeneous society: “A goal of social justice, I will assume, is social equality. Equality refers not primarily to the distribution of social goods, though distributions are certainly entailed by social equality. It refers primarily to the full participation and inclusion of everyone in society’s major institutions” (1990, 173).

While Quebecers are well represented in Canada’s political institutions, simple inclusion is not sufficient to overcome fears of assimilation. Many minorities will still want a space to call their own, and as far as many Quebecers are concerned, this was the bargain of Confederation. As Peter Russell has written, “If English Canadians and French Canadians were to continue to share a single state, the English majority could control the general or common government so long as the French were a majority in a province with exclusive jurisdiction over those matters essential to their distinct culture” (1993, 18). For many Quebecers, the pursuit of universality through the spending power has transcended the division of powers in the Constitution and thereby threatened Quebec’s power to maintain its particularity.

Young believes that “group representation” in governing institutions is the best way to ensure that minorities are adequately incorporated in the policy process (1989, 263). Curiously, for an American, she makes no reference to the federal principle, but, when culturally distinct groups are situated in territorially defined clusters, federalism can be a useful instrument for the preservation of cultural differences (Livingston 1952). In federal societies, citizenship cannot be universal in the sense that it should not be an instrument for “turning the people into one”; rather, it must allow for a multiplicity of identities and loyalties (Vernon 1988). Relatedly, national social programs are deeply problematic in federations, particularly if the responsibility for social programming lies with provincial or state governments. If this is the case, the pursuit of universality through social programs overwhelms the division of powers in the Constitution and consequently threatens the particularity of minority communities in the federation. Although many Canadians outside Quebec believe that redistributive justice is culturally neutral, Young argues that “people necessarily and properly consider public issues in terms influenced by their situated experience and perception of social relations. Different social groups have different needs, cultures, histories, experiences, and perceptions of social relations which influence their interpretation of the meaning and consequences of policy proposals and influence the form of their political reasoning” (1989, 257). Redistributive justice is obviously desirable, but the pursuit of universality can overwhelm particularity. Therefore, as Young argues, we must think beyond redistributive justice and recognize the importance of difference. I am confident that most Canadians do, in fact, value both redistributive justice and Quebec’s particularity, but I am not so sure that Canadians outside Quebec realize that these values sometimes interact in a zero-sum fashion.

The differentiated and universal conceptions of citizenship are closely connected to the contractual and circumstantial theories of federalism espoused, respectively, by Quebec and the rest of Canada. For many Canadians outside Quebec, the principles of universal citizenship require Ottawa to pursue policies of redistributive justice and social equality, and these can be achieved only through the spending power and a circumstantial understanding of the division of powers. For many Quebecers, this raises the prospect of the majority community’s determining the policy priorities of the minority community. For the government of Quebec, the province’s particularity can be assured only if it can exercise the powers accorded to the provinces under the Constitution without external interference. The theories of federalism and citizenship are deeply rooted in the political cultures of Quebec and Canada outside Quebec respectively. It is too much to ask either community to abandon its long-standing understanding of social justice. If the federation is to survive, it must find a way to reconcile these conceptions of justice without giving priority to one over the other.

There have been numerous attempts to limit the federal spending power, with only modest success at best. In general, Quebec has rejected nonconstitutional measures because they do not adequately protect the province’s particularity, while these same measures find favour in the rest of Canada because they are not viewed as a threat to federally supported social programs and the universality of citizenship. At the same time, Quebec has viewed constitutional solutions as effective safeguards of its particularity, while Canadians outside Quebec generally have rejected these solutions out of fear that they would compromise the Canadian social union. To date, governments in Ottawa have not been able to square this circle; instead, they have muddled through with a series of ad hoc arrangements and one-off deals, interrupted by the occasional referendum on Quebec sovereignty.

The first solution to the spending power was the 1965 Established Programs (Interim Arrangements) Act, under which provinces were entitled to opt out of shared-cost programs and receive fiscal compensation (either cash or additional tax room), so long as they provided a similar program with comparable standards. For some, this arrangement eliminated the problem associated with conditional grants (Black 1975, 56), but opting out was a very modest solution as far as Quebec was concerned. Peter Hogg explains:

All that opting out really involves is a transfer of administrative responsibility to the province. It does not give the province the freedom to deploy resources which would otherwise be committed to the programme into other programmes. The province gains little more than the trappings of autonomy: the federal government “compensation” to an opting-out province is really just as conditional as the federal contribution to participating provinces. (1985, 123)

While recent opting-out agreements, such as the Martin government’s child care plan, have provided Quebec with more policy autonomy, most provinces have still opted not to opt out, leaving Quebec as the only province that has made extensive use of the procedure. The terminology of opting out is problematic, for, as Courchene notes, “it is not opting out to operate a program within one’s own constitutional jurisdiction. The institutional/constitutional reality is that the rest of the provinces are ‘opting-in’ to federally-run (or jointly-run) programs” (2008, 21; emphasis in original).

Opting out was envisioned only as an interim arrangement until such time as a permanent — constitutional — solution could be found. In Federal-Provincial Grants and the Spending Power of Parliament, which was published in advance of the constitutional negotiations that culminated in Victoria in 1971, Pierre Trudeau proposed that the spending power be entrenched in the Constitution, with the proviso that the federal government would henceforth introduce a new conditional grant only if there was “a broad national consensus in favour” of the program (1969, 38). He suggested that a “national consensus” would exist if three of the four Senate regions supported a particular program initiative. By this formulation, a consensus could exist if as few as five provinces agreed to the initiative. As a gesture to Quebec, Trudeau indicated that any province would be able to opt out without fiscal penalty (34-6). Trudeau’s proposals, however, were unacceptable to Quebec: the spending power would be entrenched in the Constitution and majority rule would prevail, while opting out would provide only the illusion of autonomy. Not surprisingly, the first ministers did not reach an agreement on the spending power in the Victoria round of constitutional negotiations.

Later, in anticipation of another round of negotiations, Trudeau declared that “the division of powers between the two authorities must be clarified and made more functional” (1978, 11). And, he stressed, “some powers of the federal Parliament, such as the spending power, have a very broad scope and could be more carefully delineated in order to better ensure the internal sovereignty of the two orders of government” (23). However, the Constitution Act, 1982 did not include any limitation on the spending power, while the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was a universalizing document par excellence and completely inimical to Quebec’s theory of citizenship. In 1984, the Canada Health Act effectively elevated the spending power to a statutory provision in Canadian law. The federal Liberal Party was viewed as the “natural governing” party of the twentieth century because it so effectively brokered a political coalition between Quebec and other parts of Canada, but its commitment to redistributive justice through the spending power was completely at odds with Quebec’s theory of federalism.

Whereas Pierre Trudeau had always resisted Quebec nationalism, Brian Mulroney was eager to satisfy the province’s “minimum” constitutional demands. In a meeting with premiers in April 1987 at Meech Lake, Mulroney secured unanimous consent to amend the Constitution to address Quebec’s concerns. The Meech Lake Accord recognized Quebec as a “distinct society,” and it proposed to limit the federal spending power by inserting a new section (106A) in the Constitution Act, 1867 that read:

The Government of Canada shall provide reasonable compensation to the government of a province that chooses not to participate in a national shared-cost program that is established by the Government of Canada after the coming into force of this section in an area of exclusive provincial jurisdiction, if the province carries on a program or initiative that is compatible with the national objectives.

Quebec premier Robert Bourassa was delighted with the new provision: “The new section…is drafted so that it speaks solely of the right to opt out, without either recognition or defining the federal spending power…So Quebec keeps the right to contest before the courts any unconstitutional use of the spending power” (quoted in Trudeau 1988, 139-40). In conjunction with the recognition of Quebec as a “distinct society,” Bourassa believed he had obtained a constitutional settlement that would protect the province’s cultural particularity. On the other hand, many Canadians outside Quebec feared that limiting the federal spending power would undermine Canada’s social union or at least prohibit its expansion, and were relieved when the Meech Lake Accord finally failed. Mulroney then asked Joe Clark to resolve the constitutional impasse. While Clark was sympathetic to Quebec’s concerns, he also believed that Meech had been too narrowly focused on Quebec (1994, 5). Clark thus resolved to address the constitutional grievances of all Canadians in one fell swoop: the Charlottetown Accord.

One insider intimately involved in drafting the Charlottetown Accord has described the final agreement as a “dog’s breakfast.”11 Ronald Watts — also deeply involved in the process as assistant secretary to the cabinet (constitutional affairs) in the Federal-Provincial Relations Office — disputes this notion. In his opinion, “The agreement was not, as some have described it, a grab-bag of sixty items, but rather represented an attempt to arrive at a coherent framework” (1993, 17). Virtually everything in Meech was carried over to Charlottetown, except that these concerns were now embedded in a more pan-Canadian vision. This led to concerns in Quebec that Charlottetown was “less than Meech,” with the inference that Charlottetown should be rejected.

With respect to the spending power, would Quebec have gotten less with Charlottetown than with Meech? Arguably, yes, but in some respects Charlottetown might have gone further. For example, there was some clarification of the roles and responsibilities of each order of government. In keeping with current practices, tourism, forestry, mining, recreation, housing and municipal/urban affairs were recognized as areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction in a new section 93A of the Constitution. Like Meech, Charlottetown promised to provide reasonable compensation to any province that chose not to participate in a national shared-cost program in an area of exclusive provincial jurisdiction as long as the province offered a comparable program. Indeed, the new section 106A in Charlottetown was identical to that in Meech. Furthermore, in Charlottetown, the federal government committed itself to establishing a framework for the future use of the spending power:

A framework should be developed to guide the use of federal spending power in all areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction…The framework should ensure that when the federal spending power is used in areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction, it should: (a) contribute to the pursuit of national objectives; (b) reduce overlap and duplication; (c) not distort and should respect provincial priorities; and (d) ensure equality treatment of the provinces, while recognizing their different needs and circumstances. (“Consensus Report” 1992)

This framework was to be developed by the federal government as an intergovernmental agreement after the Constitution had been amended with the new section, although the framework agreement would receive constitutional protection, as per the provisions of the accord.

While Premier Bourassa (reluctantly) accepted Charlottetown, other Quebecers concluded that it did not meet Quebec’s concerns. Jacques Frémont described the spending power provisions in Charlottetown as a “Trojan horse” (1993, 98). While I am not persuaded by Frémont’s legal analysis, I tend to agree with him that the context of the Charlottetown negotiations may have re-established the political legitimacy of the spending power. Certainly, the spending power provisions in the accord cannot be understood without considering the provisions for the “preservation and development” of the social and economic unions. The federal and provincial governments agreed to a variety of measures to enhance the economic union, including “the free movement of persons, goods, services and capital; the goal of full employment; ensuring that all Canadians have a reasonable standard of living; and ensuring sustainable and equitable development.” Correspondingly, they also adopted a social charter as follows:

The policy objectives set out in the provision on the social union should include, but not be limited to: providing throughout Canada a health care system that is comprehensive, universal, portable, publicly administered and accessible; providing adequate social services and benefits to ensure that all individuals resident in Canada have reasonable access to housing, food and other basic necessities; providing high quality primary and secondary education to all individuals resident in Canada and ensuring reasonable access to post-secondary education; protecting the rights of workers to organize and bargain collectively; and protecting, preserving and sustaining the integrity of the environment for present and future generations. (“Consensus Report” 1992)

Most of the policy areas mentioned in the proposed social union were areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction, although neither the economic or the social union was justiciable. In the October 2007 Throne Speech, the Harper government resurrected the idea of an economic union, but presumably it would prefer to avoid a social charter.

Although there were internal tensions in the Charlottetown Accord, it was, as Watts (1993) has suggested, an honest attempt to establish a coherent response to concerns of all Canadians. It contained a framework for the spending power designed to protect Quebec’s particularity, while the social charter was included to assure Canadians outside Quebec that the federal and provincial governments were committed to universal social justice. It is possible that Charlottetown did not get the balance right, but it is also conceivable that Canadians rejected the accord more from constitutional fatigue and a palpable distrust of the country’s political leaders, most especially Prime Minister Mulroney. As we face these issues again, it might be helpful to reconsider the Charlottetown model, although the pattern of Ottawa’s social spending over the past decade arguably has moved the debate on the spending power beyond the terms of Charlottetown (see Graefe, in this volume).

After the Mulroney government failed to secure constitutional change, the new Chrétien government resolved to reform the federation through nonconstitutional means. After the 1995 referendum, Prime Minister Chrétien moved a parliamentary resolution to recognize Quebec as a “distinct society.” His government also passed the Constitutional Amendments Act, in which Ottawa agreed to lend its constitutional veto to each of the five regions of Canada, effectively giving Quebec a veto over constitutional change, along with Ontario and British Columbia. Ottawa also agreed to transfer responsibility for labour market training to the provinces along with appropriate fiscal resources, thereby meeting one of Quebec’s long-standing demands. When these initiatives failed to mollify the Parti Québécois government, the Chrétien government launched a reference case on the constitutionality of secession and ultimately adopted the Clarity Act, which specifies the conditions under which the federal government would be prepared to negotiate the terms of a province’s secession.

With respect to the spending power, Chrétien sought to restore a federal role in social programs in the Social Union Framework Agreement (SUFA), which was signed by the federal government, nine provinces and both territorial governments in February 1999. Quebec refused to endorse SUFA, although it participated in the negotiations that led to the final agreement. SUFA permits Ottawa to use its spending power to establish new social programs in areas of provincial jurisdiction. Indeed, it declares, “The use of the federal spending power under the Constitution has been essential to the development of Canada’s social union.” As a sop to the provinces, Chrétien agreed that new programs would be negotiated with the provinces, but under SUFA the federal government requires the support of only a majority of provinces to proceed with a new program. While the provinces were evidently seeking an opting-out provision with full fiscal compensation, including direct payments to individuals and organizations, the final agreement did not include a formal opting-out provision. The federal government was able to persuade the English-speaking provinces to drop that demand in exchange for enhanced health transfers, much to Quebec’s displeasure. In sum, the spending power provisions in SUFA are much more in accordance with theories of federalism and citizenship held by Canadians outside Quebec.

SUFA was a setback for Quebec and a missed opportunity for Canada. Claude Ryan — the former leader of the Quebec Liberal Party — noted that it was “the first time, to my knowledge, that a PQ government declared itself ready to accept the principle that the right to opt out should be accompanied by a commitment from the province involved to put into place a program or measure in the same area as the national program” (1999, 29). Alain Noël has argued that Quebec made two other significant concessions in the SUFA process: “It accepted much of the inter-provincial — and pan-Canadian — discourse on the social union; and it recognized implicitly a legitimate role for the federal government in social policy” (2000, 8). For Christian Dufour, it is telling that the whole project was cast as a “social union” rather than “social federalism” (2002, 7). The spending power provisions in SUFA were inconsistent with Quebec’s theory of federalism, and consequently the agreement was rejected by the Parti Québécois government with the support of the opposition Liberal Party led by Jean Charest. Although Quebec refused to endorse the agreement, Noël notes that the “new rules nevertheless apply to Quebec, and the collaborative process goes on as if, or almost as if, all agreed” (2000, 4).

How does the Conservative plan to limit the spending power compare to the efforts described above? In many respects, it would appear to be a case of “back to the future.” The statutory approach favoured by the Conservatives seems highly reminiscent of the 1965 Established Programs (Interim Arrangements) Act. While the new legislation might play well in Quebec in the short term, the government of Quebec likely will view it only as an interim solution. In the longer term, Quebec likely will pursue its historical objective: a constitutional solution to the spending power, with the right to opt out with unconditional payments for all federal initiatives that fall in areas of provincial jurisdiction.

In order to understand the Conservative plan more fully, it is necessary to parse the language of the October 2007 Throne Speech very carefully:

Our Government believes that the constitutional jurisdiction of each order of government should be respected. To this end, guided by our federalism of openness, our Government will introduce legislation to place formal limits on the use of the federal spending power for new shared cost programs in areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction. This legislation will allow provinces and territories to opt out with reasonable compensation if they offer compatible programs. (Government of Canada 2007)

First, the word “new” indicates that the impending legislation on the spending power will not apply to old shared-cost programs in areas of provincial jurisdiction, such as health care and social assistance. Indeed, the Conservatives promised in the 2006 election campaign to establish a patient wait-times guarantee even though health care is a matter of provincial jurisdiction. Furthermore, the Conservatives have been quite anxious to maintain the five principles of the Canada Health Act. Presumably, they do not want to set off alarm bells with potential voters in the centre of the political spectrum, but at the same time they presumably have no plans to introduce new shared-cost social programs.12 As such, the plan has been greeted with yawns in some quarters in Quebec. As Alain Noël writes, “Or, Ottawa a cessé d’introduire de tels programmes depuis déjà quelques années et il est hautement improbable qu’il recommence dans l’avenir. Au Québec, les réactions sont donc demeurées tièdes, et la question est plus ou moins disparue de l’ordre du jour” (2008, 80).

Second, the emphasis on shared-cost programs does not preclude new programs in areas of provincial jurisdiction where costs are not shared, such as family allowances, grants for university students and financial support for municipalities. These are examples of the direct use of the federal spending power to benefit individuals and organizations. While previous federal governments reserved the right to use the spending power directly in aid of initiatives in areas of provincial jurisdiction on the grounds that they were matters of “national” or “general” importance, it is not clear how the current Conservative government reconciles this use of the spending power with its stated goal to respect “the constitutional jurisdiction of each order of government” or with open federalism more generally, which, according to the Conservative election platform, was supposed to entail “clarifying the roles of both levels of government within the division of powers of the Constitution” (Conservative Party 2006, 22).

While some Conservatives may view open federalism as a program of “disentanglement” from the provinces, the Harper government’s willingness to use the spending power directly in areas of provincial jurisdiction belies this belief. The direct use of the spending power avoids the problem of compelling provinces to abide by various conditions in order to receive transfer payments and thereby compromising provincial “sovereignty,” but it still creates a problem of intergovernmental policy coordination. With Harper’s reluctance to meet the premiers, it seems that the federal government has become involved in new areas of provincial jurisdiction without the benefit of coordination at the highest levels of government, even though the Conservatives promised in the 2006 election campaign to “support the important contribution the Council of the Federation is making to strengthening intergovernmental and interprovincial cooperation” (Conservative Party 2006, 22). Consequently, all the attendant problems of entanglement are exacerbated: a general lack of coordination, policy duplication, distortion of provincial priorities and provincial uncertainty about long-term federal spending commitments in these areas. If this is to be the reality of open federalism, the provinces will likely not tolerate it for very long. If open federalism also entails federal hectoring of provincial budget decisions, as Finance Minister Jim Flaherty seemed to indicate at the time of the last Ontario budget, Canada might be headed for a period of highly strained federal-provincial relations.

The Conservatives evidently have decided to pursue a statutory limitation of the spending power, on the assumption that constitutional options are not currently possible. But even if that is true, is the statutory approach the best alternative? It is not clear. The statutory approach is both more and less robust than an intergovernmental agreement such as SUFA. On the one hand, the new limits — however minimal — will be enshrined in law and therefore cannot be ignored like intergovernmental agreements when convenient. On the other hand, Parliament can change this law when convenient, whereas it cannot unilaterally change an intergovernmental agreement. As it stands, SUFA is not acceptable to Quebec because it did not contain a formal opting-out provision, but amending SUFA arguably might be a better solution to the problem. A revised SUFA would be more consistent with the principles of collaborative federalism and presumably with those of open federalism as well, but Stephen Harper has shown little inclination to meet with the provinces collectively. The statutory approach is simply more compatible with his unilateral management style.

While the federal Conservative Party and Quebec have similar visions of federalism, they have different conceptions of citizenship. The Conservative Party adheres to a theory of universal citizenship, albeit one premised on negative liberty as opposed to the theory of positive liberty underlying the Canadian social union. By contrast, Quebec embraces a differentiated theory of citizenship, which is completely inimical to the populist reform origins of the new Conservative Party (Telford 2002), notwithstanding the party’s surprise decision to support a parliamentary resolution recognizing Quebec as a nation. The ideological overlap between the Conservative Party and the political culture of Quebec is at best only partial. It would thus seem that the Conservatives’ efforts to win support in Quebec on the federalism axis can go only so far, and it may have already reached its limit.

In sum, it would seem that the principles of open federalism — as presently articulated — are not sufficient to reconcile the competing claims for particularity in Quebec and universality in the rest of Canada. A mutually satisfactory agreement on the spending power will require a more robust solution. I propose two possibilities for discussion. In the past, Quebec has tended to favour constitutional solutions to the spending power, while the rest of Canada has preferred nonconstitutional options. In contrast, I advance a constitutional option that might appeal to Canadians outside Quebec and a nonconstitutional approach that might find favour in Quebec. The first option may err on the side of universality, while the second option leans toward particularity. Both options are problematic and potentially riskier than the status quo, and they would require the expenditure of considerable political capital before they could be adopted.

For the past 60 years, federal governments have defended the spending power as the only available instrumentality for the establishment and maintenance of pan-Canadian social programs with comparable standards, in the belief that any limitation to the spending power would dampen their ability to instill vertical and horizontal equity in the federation.13 This is why federal governments have insisted that any province that chooses to opt out of a shared-cost program must offer a comparable program in order to receive fiscal compensation. As such, opting out with compensation is just as conditional as opting in: Quebec opts out in principle, while the other provinces see no advantage to opting out. On paper, the federation appears to be asymmetrical, but it is a soft asymmetry: it has little, if any, substantive meaning.14 If the federal government ever offered unconditional compensation, as Quebec has demanded, the other provinces would presumably avail themselves of the opportunity to opt out, eliminating the federal government’s ability to instill equity in the federation. So we appear to be stuck. Solutions that satisfy Quebec are unacceptable to the federal government and many Canadians outside Quebec, but solutions that receive favour in the rest of Canada leave Quebec unsatisfied.

But is the spending power really the only instrument available to ensure pan-Canadian social programs? Perhaps it is time to reconsider the idea of a social charter. There is a relatively high degree of consensus in Canada on the principles of redistributive justice. Indeed, the federal and provincial governments drafted a fairly coherent vision of the social union in the Charlottetown Accord, committing themselves to providing Canadians the basic necessities of life, ensuring high-quality primary education and access to post-secondary education, labour rights, protection of the environment and the five principles of the Canada Health Act. As noted above, these provisions were to be nonjusticiable. If, however, the provisions of a social charter were justiciable, the provinces would be constitutionally obligated to offer broadly comparable social programs, although perhaps with a greater degree of diversity than currently exists. While a justiciable social charter undoubtedly would be difficult to codify, such a charter would largely terminate the need for the federal spending power. Federal transfers could thus be made unconditionally, in the form of either tax points or continued cash transfers. The latter would be more conducive to tax harmonization, as they would grant less fiscal space for interprovincial tax competition (Boadway 2006, 44). They would also enable the federal government to redistribute revenue more easily across the provinces to address horizontal equity concerns. The constitutionalization of the equalization program in 1982 might be viewed as a precedent for the constitutional entrenchment of social policy.15

It is admittedly paradoxical to employ a universalizing instrument to ensure Quebec’s particularity, but it might square the circle. A social charter would assure Canadians outside Quebec that the federal government was still committed to the social union, particularly with respect to established programs, but it would not necessarily preclude new programs.16 It would also conform to the theory of universal citizenship, including the procedural notion of equality. Would it meet Quebec’s concerns? Admittedly, it would subject Quebec’s social programs to possible challenges in the courts, including the Supreme Court of Canada, but Quebec is not currently immune from such challenges.17 While courts have been widely criticized for policy-making (see, for example, Morton and Knopff 2000; Manfredi 2001; Brodie 2002), they have a broad obligation under section 24.1 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to hear just about every case that entails an unresolved point of law, including those from citizens who believe their rights have been infringed by the legal statutes enacting the various social programs in the country. As such, it might be helpful to give the courts a framework to work with — such as a social charter. While theory suggests that charters have centralizing effects, there is reason to believe that the Supreme Court has been more sensitive to provincial particularity when interpreting the Charter of Rights than it has been in federalism cases (Kelly 2005). Moreover, a social charter enacted with the consent of Quebec would go some way to thwarting a domineering federal government’s interfering in areas of provincial jurisdiction. Ultimately, Quebec will have to make some sort of concession to obtain unconditional federal transfers, and this option might maximize its political autonomy.

The prospects for a social charter, in the short run at least, are dim. It was presumably fairly easy for the federal and provincial governments to negotiate a nonjusticiable social charter in Charlottetown, but they would be much more wary of a justiciable charter. And any attempt to negotiate a social charter would likely open up the whole Pandora’s box of constitutional reform, which would entail special recognition and a veto for Quebec, Senate reform for the West, a provincial role in Supreme Court appointments and Aboriginal self-government, among other things. The process might also trigger referendums in some provinces and likely a national referendum, too. And there would be no guarantee of success — it would require a political leader with considerable courage to launch a national conversation on the Constitution at this time. As such, Canada is destined to address an essentially constitutional issue through ad hoc intergovernmental processes for the foreseeable future.

While it may not be possible to have truly harmonious intergovernmental relations in Canada, everyone would surely agree that the process could be improved. For starters, it has been noted that there is “a serious lack of coordination among first ministers at the peak of the intergovernmental hierarchy” (Meekison, Telford, and Lazar 2004, 25). Indeed, first ministers’ meetings have been described as “the weakest link” in Canadian intergovernmental relations (Papillon and Simeon 2004). The demand for an annual meeting of first ministers dates from at least 1940, when the Rowell-Sirois Commission concluded that “DominionProvincial conferences at regular intervals with a permanent secretariat…would conduce to the more efficient working of the federal system” (Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations 1954, 71).18 Exactly 45 years later, in the Regina Accord, Brian Mulroney committed the federal government to an annual meeting of first ministers, and attempted to entrench this commitment in the Constitution in both the failed Meech and Charlottetown accords. The scale and frequency of first ministers’ meetings declined under Jean Chrétien, and they show no sign of rebounding under Stephen Harper. Admittedly, federal-provincial conferences frequently have been opportunities for the provinces to gang up on the federal government, but the irregularity of the conferences exacerbates the problem.19 “If [first ministers’ conferences] were built into the normal political calendar,” Martin Papillon and Richard Simeon contend, “officials and ministers could set their activities around them, the agenda could be developed more co-operatively, effective preparation could be carried out, and it would be much easier to develop regular delegation and reporting relationships with ministerial councils and others” (2004, 132). In short, a regular meeting would allow first ministers to meet in a more relaxed atmosphere and for trust ties to develop between federal and provincial officials and elected representatives. It would also give them the opportunity to settle upon effective decision-making rules before the onset of a crisis. The provinces moved in this direction with the creation of the Council of the Federation in 2003, and Stephen Harper promised in the 2006 election to work with it, but he has not followed through on this commitment.

A regular meeting of first ministers would be a useful practice, however, only if effective decision-making rules were established. Canada has been criticized for relying on the unanimity rule. Nicole Bolleyer argues that a “core feature of strong [intergovernmental] institutionalization is a formal decision-making rule that deviates from unanimity because the capacity to bind the substates to common positions or plans to which they did not agree demonstrates that the [intergovernmental agreement] is thought to represent more than the sum of its parts” (2006, 474). In the Canadian context, however, it would be unjust for the majority to bind a minority group to a plan over its objections. Indeed, it was precisely the application of the majoritarian principle during the establishment of the social union and ultimately the patriation of the Constitution that caused so much consternation in Quebec.

If the unanimity principle is too rigid and the majoritarian principle unjust, what other alternatives might be employed? At this juncture, it might be helpful to examine political practices in other democracies, particularly the consociational form of multi-party coalition government found in many diverse European countries. While some highly experienced players have indicated that party politics plays little role in the intergovernmental process (Segal 2002; Meekison 2004), Kenneth Carty and Stephen Wolinetz (2004) suggest that the federal-provincial management of the federation is akin to a coalition government. Consociationalism and federalism are the principal instruments for governing culturally divided societies; both have been successfully employed in Switzerland, and Canada’s system of brokerage politics arguably represents a form of intra-party consociationalism. But, as Canada’s intergovernmental “coalition” is multi-party, the brokerage model of conflict management does not seem apropos. The principles of consociationalism, on the other hand, are specifically designed for multiparty coalitions.20 Under these principles, the intergovernmental decision-making process in Canada ought to operate under the “concurrent majority” principle, with Quebec afforded a veto. While this might be appropriate for many intergovernmental decisions, it is not quite what is needed with respect to the spending power. Quebec does not want to participate in any shared-cost programs, but it has never had any desire to prevent the other provinces from opting in to such programs if they wish. As such, Quebec does not want a veto in these instances; it simply wants to be able to opt out with unconditional fiscal compensation.21