Les tendances démographiques associées au vieillissement de la population sont connues depuis des décennies, pourtant, le Canada n’a toujours pas défini une stratégie globale pour faire face aux répercussions socioéconomiques à long terme de ce phénomène, et moins encore à ses conséquences immédiates pour ce qui est des soins aux personnes âgées. Cette étude de Harvey Lazar part du triple constat d’un déséquilibre entre la demande et la disponi- bilité des soins, d’une éventuelle aggravation de ce déséquilibre et d’une nécessaire réévalua- tion du rôle du gouvernement fédéral à cet égard.

En matière de soins, la responsabilité constitutionnelle appartient aux gouvernements provin- ciaux et territoriaux, mais le gouvernement fédéral lui aussi joue un rôle important. En effet, bien que les provinces planifient, gèrent et supervisent la prestation des soins de santé et des services sociaux, les programmes fédéraux de pension et de sécurité du revenu pour personnes âgées et les paiements de transfert aux provinces ont une grande influence sur la disponibilité des soins et leur accessibilité. À l’heure du vieillissement démographique, d’une pénurie appréhendée de main-d’œuvre et de l’accentuation des pressions sur le système de santé, Ottawa sera vraisemblablement appelé à faire davantage.

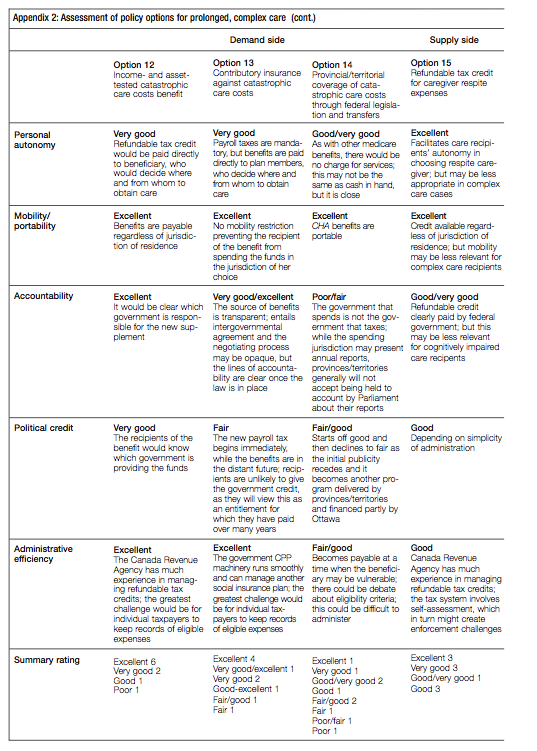

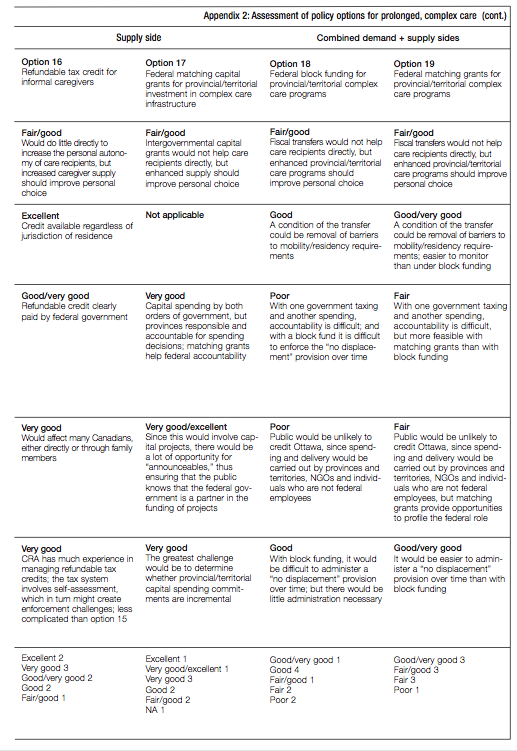

Harvey Lazar examine donc le rôle actuel et les possibilités d’action du gouvernement fédéral au chapitre des soins aux personnes âgées. Il propose un éventail de mesures qui permettraient d’intervenir à la fois du côté de la demande et de l’offre, et qui seraient adaptées aux particu- larités du continuum de soins. Il évalue ensuite ces options afin de déterminer si elles sont conformes : 1) au partage constitutionnel des pouvoirs législatifs et au bon fonctionnement de la fédération ; 2) à 10 critères et objectifs de « bonne » politique publique dans ce domaine.

L’auteur en conclut qu’Ottawa dispose d’une marge de manœuvre appréciable pour répondre aux besoins grandissants des personnes âgées et au sous-financement des soins sans empiéter sur le leadership des provinces et territoires. Bon nombre des mesures qu’il propose visent directement les aînés pour les protéger entre autres contre le coût prohibitif de certains soins et renforcer leur capacité financière afin qu’ils puissent se procurer les services dont ils ont besoin. Il met aussi de l’avant quelques mesures qui devraient accroître la capacité de presta- tion de soins partout au pays.

La prochaine occasion de prendre d’importantes décisions sur la question se présentera lors de la renégociation en 2014 des transferts fédéraux en matière de santé et de programmes sociaux. Or il revient à Ottawa d’établir un diagnostic clair sur les besoins futurs de soins aux personnes âgées à l’échelle du pays. Il lui faudra également mieux définir son propre rôle, tout en tenant compte de l’incidence de ses interventions sur l’efficacité des programmes de soins provinciaux.

Preparing for an aging society has long been recognized as an important multidimensional challenge for Canada. The prospect of this demographic transformation has prompted much research on the potential economic and social implications for individuals and society and has raised major public policy issues. In the 1970s and early 1980s, the main focus of research was on the retirement income system.1 In the 1980s and 1990s, the effects of popula- tion aging on health care expenditures began to garner much attention. Both topics remain on the policy research agenda to this day, but a third theme has been added in recent years: the availability and cost of care for seniors.

Seniors’ care is not an easy topic to research, partly because it involves informal interactions, financial and otherwise, within the family. Researchers have nonetheless made significant inroads in understanding the needs of care recipients and the sources of caregiving, which include the immediate and extended family, friends and neighbours, as well as community organizations, institutions (nursing homes, assisted living and complex care residences) and governments. There remain important research and knowledge gaps, however. For example, there is little information on the actual availability of informal caregivers for disabled individ- uals (e.g., the proximity of children or the health status of spouses), and there is still much to learn about the interaction between the formal and informal care networks and systems and how they might be affected by the ongoing demographic trends.

The issues related to the care system reach far beyond the front-line actors. All Canadians, regardless of age, are potential care recipients and caregivers. Once they reach their adult years they need to prepare for the contingency of receiving (as seniors or even younger) or providing (to a parent, spouse or friend) care. Like pension policy, care policy affects relations among generations, and what is considered to be fair among generations will differ depending on whether it is assessed within the confines of the family or at the level of society.

The object of this study is to spur a public debate about one aspect of care policy that has received little attention to date.2 I am referring here to the way in which Canadian federalism affects the adequacy and availability of care for seniors. More particularly, I will look at the role the federal government has played in seniors’ care to date and what its options could be, and should be, as the population aging process unfolds.

The division of powers in our constitution and the lessons from seven decades of practical experience provide a general guide to the respective roles of federal and provincial/territorial governments in regard to seniors. Looking at the issue through this wide-angle lens, we see that the federal government has the lead role in providing pensions and other forms of income support, while the provinces plan, manage and oversee the delivery of health care and social services, including nonmedical care.

Since the current income support/service split between the two orders of government is relatively harmonious, it would be legitimate to ask whether it might not be best to leave well enough alone and not risk stirring up a hornet’s nest. The fact is that this broad description of “who does what” is far from perfect. Examples that do not fit within this neat division of tasks include provincial/territorial responsibility for social assistance and the federal government’s traditional role in the field of health care. It also brushes over the complex and inefficient overlap between the two orders of government in providing income support to people with disabilities.

This big picture also excludes the several ways in which the two jurisdictions inevitably inter- sect in carrying out their roles. At the constitutional level, provincial powers to make laws relating to old age and disability pensions trump federal authority. Accordingly, federal legisla- tion in these areas requires the acquiescence, if not the enthusiastic support, of the provinces. At the operational level, Ottawa’s decisions can influence provincial governments through either the level of income support that it provides to seniors or the magnitude of its cash transfers to the provinces and territories. Indeed, access to care for seniors is heavily affected by the decisions of both orders of government, as well as by the way in which governments interact.

Governments loom large in the lives of retired people. Over three-quarters of the aggregate income of those aged 65 and older comes from pensions — 42 percent from public pensions and 34 percent from private pensions. Lower-income Canadians are even more reliant on pub- lic plans, which account for as much as 80 to 100 percent of their income. The elderly also receive a larger proportion of the services they require through governments or government- subsidized activities than do people of working age.

The federal government delivers almost all public pensions (the main exception being the Quebec Pension Plan), and it also plays a large role in supporting private pension plans through income tax incentives. The federal government does not, of course, view its major retirement income programs (e.g., Old Age Security, Guaranteed Income Supplement, Canada Pension Plan, Registered Pension Plans and Registered Retirement Savings Plans) as part of the care system. But the impact of these policies on how care is organized is nonetheless pro- found. For example, the extent to which provincial/territorial governments need to plan for and subsidize care for an aging population is linked to the income levels of retired people. The more income they have, the more they are able to pay for services — including many kinds of care — on their own.

Another way that federal policies can influence provincial care decisions is through health and social transfers to the provinces. For instance, through the Canada Social Transfer (CST), Ottawa provides direct cash contributions to the provinces and territories, “notionally” (a term used by the federal Department of Finance) for social services, including care services. However, under current fiscal arrangements, the CST and other large federal transfers will expire on March 31, 2014. During the 2011 federal election campaign, the Conservative plat- form stated that the government “would work collaboratively with the provinces and territo- ries to renew the Health Accord” (Conservative Party 2011, 30), but it failed to mention the CST. Nor was the CST mentioned in the subsequent federal budget, presented on June 6, 2011.3 The reality is that the nonhealth costs of aging involve large sums and they interact sig- nificantly with the health costs.

Overall, the current relationship between the two orders of government in respect of pension policy and care challenges is low key, notwithstanding concerns about distressing system fail- ures in the recent past (such as the insolvency of some big private pension plans). For the most part, intergovernmental differences are managed without serious tensions. Indeed, there are ongoing discussions among federal, provincial and territorial governments on adding a further tranche to the retirement income system.4

This study is thus not motivated by a sense of crisis in intergovernmental relations. Rather, the main concern is that Canadians and their governments have not been preparing sufficiently for the kind of older society that they will constitute less than two decades from now. The aging of the population guarantees that the Canada of tomorrow will be quite different than the Canada of today. Since desirable policy out- comes on this front will likely require long lead times, postponing decisions about how to best prepare until some murky date in the future would in itself be a decision about the nature of that future.

Both orders of government now play a direct and/or indirect role in meeting care needs. The fact that their decision-making processes function largely independently of one another is far from a bad thing, since federal-provincial processes are not known for their speed or efficiency. Given their interaction on care issues, however, it is essential that each order of government understand not only the direct effects of its decisions on citizens, but also the consequences of these decisions for the programs of the other order of government in relation to these same cit- izens. The social issues are too important and the amounts of money too large for governments to ignore these ripple effects. These effects are not symmetrical. Provincial/territorial decisions only occasionally affect federal policies related to seniors’ well-being, whereas federal decisions have large, ongoing, direct and indirect impacts on provincial care programs. It is essential, therefore, that the federal government take into account how its interventions might influence the success of provincial care programs and ultimately the well-being of those who require care.

This study has two purposes. Assuming that Ottawa continues to respect the constitutional and policy pre-eminence of the provinces in care policy, the first is to determine whether and in what ways Canada’s federal structure influences the strategic choices available to the federal government in responding to the growing care needs of seniors. The second is to examine what Ottawa’s role could be in the future, and assess it in relation to two sets of standards: those that pertain to federalism principles and functional intergovernmental relations, and those that take account of other public policy criteria such as efficiency, equi- ty and accountability.

To foreshadow my conclusions: Notwithstanding constitutional limits on what the federal government can do directly in the sphere of caregiving, and taking full account of the leader- ship role of the provinces, there are many degrees of policy freedom available to Ottawa in addressing the growing and severely underfunded care needs of seniors.5 Viable options include measures aimed at seniors with light or intermediate care needs, as well as measures designed to enhance access to and provision of prolonged, complex care, and they relate to both the demand and the supply sides of caregiving.

Demand refers to the volume and the complexity of the care services required by seniors to ensure their well-being.6 Demand for care is determined by individuals’ health and personal cir- cumstances. Supply refers to all caregivers who are willing and able to perform the tasks for which there is a demand. These caregivers include family, friends, neighbours and volunteers who traditionally have not been paid for the assistance they provide (although this has begun to change); professional caregivers who work for provincial/territorial governments or nonprofit organizations; and businesses and individuals who provide care services at a price.

Demand is linked to the idea of personal autonomy. Ideally, personal autonomy means there are minimal limitations on a person’s activity and minimal restrictions on her participation in society.7 In the context of this study, it also entails having choices and the ability to make one’s own decisions in terms of caregivers and living conditions. In practice, however, care recipients’ personal autonomy will be determined by their health status and the formal and informal support systems and services that are available to them. Some of the measures required to maintain or increase care recipients’ personal autonomy may be costly, some may actually save money. In any event, personal autonomy is an issue that must be considered in any debate about care policy, and it is increasingly reflected in health officials’ efforts to enable people who require care to receive it at home for as long as possible.

Another important theme in this study is intergenerational equity. This refers to fairness in financial and other relationships between different generations. In one idealized version of this concept, each generation would pay for its own benefits, requiring no transfers from other generations. However, achieving a modicum of fairness between generations is very dif- ficult in practice. This becomes apparent as soon as one begins to consider the details of a new seniors’ care benefit: Should it be phased in over several decades, or should it be implemented immediately? If the phase-in period is long — say, 30 or 40 years — there will be little or no reduction in current unmet care needs. If the benefit is implemented fully without any phase- in, it may well be unfair to current taxpayers and, most acutely, to the younger cohorts. They may end up “paying twice,” contributing through higher taxes or other levies to cover the costs of the incremental care services made available to current seniors, and also paying for their own future benefits (by either participating in a public contributory plan or saving on their own). These younger taxpayers cannot rely on the future workforce to subsidize them when they become seniors, because with population aging, the future workforce may be too small and the future elderly too numerous to sustain the intergenerational subsidy. Balancing these intergenerational transfers in an aging society is a crucial issue in decision-making and a fundamental consideration in my analysis.8

These two themes can be linked. To the extent that maintaining seniors’ autonomy reduces public costs, it also reduces the size of any intergenerational transfers. When these considera- tions are aligned, policy is likely to be on a positive course. When they are in tension, policy choices are more difficult.

The study is organized as follows. In the first section, I set out six research premises regarding the care needs of seniors, the capacity of individuals to plan for themselves and Ottawa’s potential role in this policy area that frame the subsequent analysis. I also present the federalism/intergov- ernmental relations criteria and 10 other policy criteria that will be used to assess each option.

To provide a context for the discussion of care policy options that follows, I then review what Ottawa is currently doing, directly or indirectly, in relation to caregiving in four areas: income security for retirees, financing of social programs through the spending power, support for informal caregivers, and knowledge and information dissemination, and I examine how these various initiatives affect federal-provincial relations.

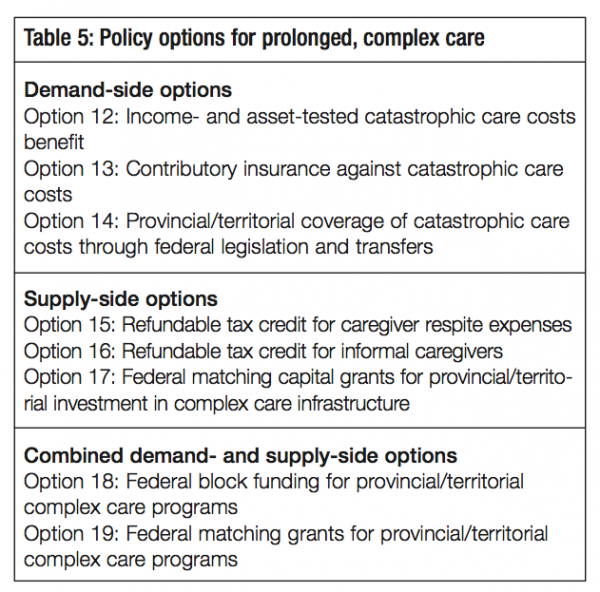

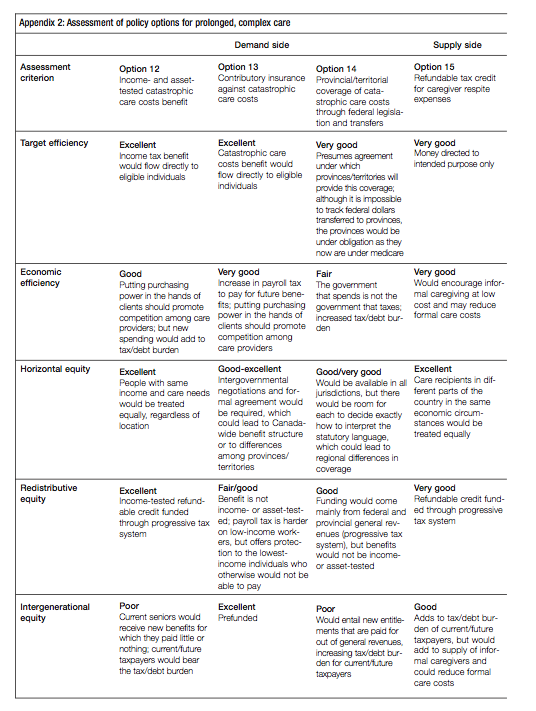

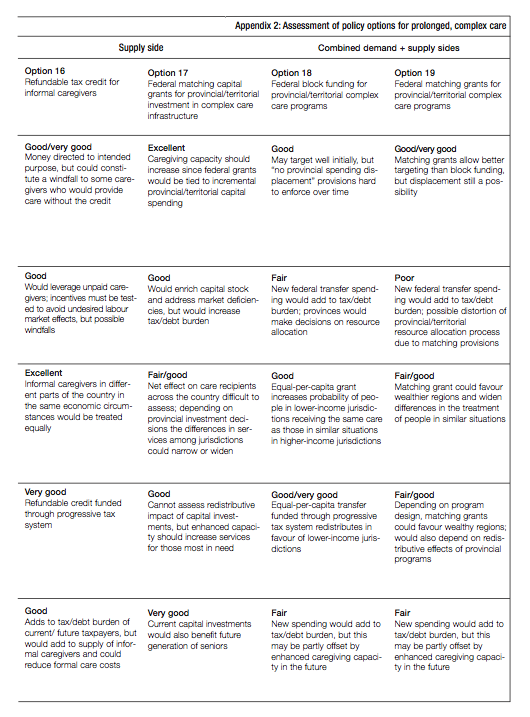

In the next two sections, I present a wide range of policy options available to the federal gov- ernment. The list of 19 options is not exhaustive, but it serves to illustrate the types of choices that could be considered. While some of the options are new, there is a precedent for most of them in current arrangements or post-Second World War history. A clear distinction is made in the analysis between the instruments that are suitable to address lighter and intermediate care needs and those that are more appropriate in the context of prolonged, complex care. Some options support the demand side of care, while others are meant to further develop the supply side. I then assess all of the options in terms of their probable effects on intergovern- mental relations and against the policy criteria referred to above.

It should be noted that the options are presented at a high level of generality, with little elaboration of design/costs and little reference to the current economic or fiscal environ- ment. The reasons for this are twofold. First, the purpose of this study is to explore the broad implications and trade-offs associated with different strategic directions, and more precisely to determine whether federalism will be a significant constraint on Ottawa’s strategic role going forward. Second, the time horizon for the issues examined in this study is years and even decades, not months. I conclude briefly in the final section.

The following premises frame the choice and assessment of possible options available to the federal government to support the provision of care for seniors.

First, the aging of the population will increase the need for care and the costs of care borne by governments. Like those of other industrialized countries, Canada’s population is aging, due to a persistently low birth rate and increasing life expectancy. The aging of the baby boom generation (those born between 1946 and 1965) adds a cohort-specific dimension to this situation (Schellenberg and Ostrovsky 2008). The first boomers turn 65 in 2011 and will reach 85 in 2031. At the same time, the working-age population is shrinking, and will continue to do so. Thus, beyond the increased demand for seniors’ care, the growth in the number of seniors relative to those of working age will lead to added pressure on provincial/territorial budgets.

But it is not just the growth in the number of elderly that will increase costs. There is also the fact that the demand for care is age related. A Statistics Canada study based on surveys conducted in 1994-95 and 2003 found that about 2.5 percent of those aged 18 and over received subsidized care, whereas the figure was around 20 percent for those aged 80 and over (Wilkins 2006, 39-42). With the aging of the population, current projections suggest that the number of elderly Canadians needing assistance will double in the next 30 years (Carrière et al. 2007, figure 6; Alzheimer Society 2010).

The unit costs of care services are also likely to increase, as the relative scarcity of caregivers will strengthen their bargaining position on wages and benefits. I use the word “likely,” because it is uncertain whether the labour market for caregivers behaves like a conventional service-industry market. If it does, wages will increase, and as compensation rises, the supply of caregivers will grow. If it does not, governments will need to consider supplementing care- givers’ compensation to increase their supply.

There are similar demographic concerns with informal care. Statistics Canada observes that “63 per cent of adults with disabilities who received help obtained it from members of their family living with them, 42 per cent received it from family members not living with them, 24 percent from friends and neighbours” (2003, 7). In 2007, 4.1 million Canadians aged 45 and over were providing some form of care to someone with a long-term health condition or physical limitation (Statistics Canada 2008a). However, socio-demographic trends suggest that the network of avail- able informal caregivers will be smaller in the future. And this, combined with greater demand for care, could lead to large and increasing shortfalls in informal caregivers going forward (Keefe, forthcoming). The magnitude of such shortfalls is difficult to project, but it is likely to be signifi- cant. The 2001 Participation and Activity Limitation Survey reported that roughly one-third of people with disabilities reported unmet care needs (Statistics Canada 2003, 7). Another survey found that while more people received subsidized home care in 2003 than in 1994-95, the pro- portion of people needing but not receiving help was also significantly larger (Wilkins 2006).

To sum up, growing shortfalls in the supply of formal and informal caregiving services in the future will put pressure on the provinces and territories to increase the amount of govern- ment-subsidized care they provide.

Second, there is great diversity in the care needs of seniors, and the range of services they require can be thought of as a continuum. At one end are people with mild disabilities and relatively easy-to-manage symptoms. At the other end are people with the most severe prob- lems and disabilities (MacKenzie, Hurst and Crompton 2009, 57). Accordingly, it is appropri- ate for governments to have different policies at different points in the care continuum.

People with lighter care needs will usually live in their own home or with family. Some may have a chronic condition that limits their mobility, in which case they may require homemaking and home support on a regular but infrequent basis. Others may be at home after spending time in a rehabilita- tion facility. They may need a range of homemaking and personal care services and perhaps further physiotherapy until their recovery is complete. Their need for care is thus likely temporary.

Those with intermediate care needs often have chronic conditions that have deteriorated to the point where their mobility is significantly limited. Others may be experiencing the first symptoms of cognitive impairment. (A study commissioned by the Alzheimer Society states that 55 percent of Canadians aged 65 and over with dementia live at home, and that the per- centage is expected to increase [2010, 7].) Individuals who are receiving post-acute care at home rather than in hospital may also be receiving intermediate care temporarily. Intermediate care services will, on average, be more numerous, more frequent and more spe- cialized than those required at the light end of the continuum. More often than not, people requiring this level of care are still living at home, although there are other options such as supportive housing and assisted housing. In either case, some of the assistance they receive may come from a provincial home care program, on either a subsidized or a nonsubsidized basis, depending on their income or that of a partner with whom they may be living.

The heavy end of the care continuum also encompasses a wide range of situations. The term “heavy” is used in this context to refer to the range and level of services required by individuals whose condition is both complex and of long duration, and thus very costly. This includes individuals who lack the physical or mental capacity to perform many of the activities of daily living without assistance; those whose cognitive impairment is severe enough to make communication difficult; those with severe behavioural difficulties; and those in end-of-life situations. Such individuals may reside in a tightly supervised group setting, a palliative care clinic, a long-term care facility or at home but with assistance readily available at all times. The term most often used by governments to describe the services required by people at this end of the continuum is “complex care” (see, for exam- ple, British Columbia 2010) or “complex continuing care” (see Ontario 2011). In a free- market setting, for people who require complex care for extended periods (years rather than weeks), the costs can be catastrophic, consuming all of their income and ultimately necessitating the sale of all their assets.

This diversity of needs is of course reflected in the types of care services required and the related costs. For some services the provider must have considerable education and train- ing. But many types of assistance require little specialized training and, as mentioned, tend to be provided by spouses, children, other relatives, friends, neighbours and volunteers on an unpaid basis. Some care recipients try to spare relatives and friends the time and effort of caregiving by purchasing services privately or obtaining them through public programs. Indeed, this may increasingly be the case as societal values and expectations begin to change (see Keefe, forthcoming).

Ultimately, there is a world of difference between the 65-year-old retiree with some modest limitations on her mobility married to a healthy man who takes on some of the physical chores that she previously performed, and the 90-year-old widow who has had advanced dementia for several years and is living in secure assisted housing with 24-hour surveillance. This suggests that government strategies should be flexible enough to respond according to the various needs at different points on the care continuum.

Third, individuals should plan their retirement with the expectation that they may need to pay for some care services, but planning for and financing catastrophic care costs is best done by pooling the risk at the societal level. Most people will require some form of care at some point in their later years, and in general there is no reason why they should not have planned their financial affairs during their working years such that they can pay for a moderate level of services in retirement. (This may not apply to the long-term unemployed or those with long- term dependence on social assistance or disability income supports.)

But that being said, it is impossible for most working-age individuals to know how much and what kinds of care they might need in their retirement years. This “unknowability” in terms of future care requirements raises important issues. It is unreasonable to expect indi- viduals to save enough during their working years to cover the relatively low probability but high costs of requiring prolonged, complex care.9 Yet we know that some individuals will face catastrophic care costs. The usual way for individuals to protect themselves against such a contingency is by pooling the risk through insurance. An important consid- eration is whether such insurance should be provided through the private market or social insurance.10

The Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association has estimated that 400,000 Canadians have long-term care coverage (CLHIA 2011). Given that there are about 18 million Canadians in the labour force and about 20 million between the ages of 20 and 64, it is clear that to date long-term care has been a relatively small market for insurers. Based on US studies, those who are most likely to need care in their postretirement years — those who develop chronic progressive illnesses or have permanent disabilities — are also least likely to be able to purchase insurance. High-income earners are also much more likely than low-income earners to purchase insurance for caregiving services.11

These and other particularities of long-term care and the market for private insurance sug- gest that social insurance is the best strategy (see Grignon, forthcoming). What is unknown in terms of risk and probability at the level of the individual can be estimated with much more certainty for the population as a whole. Available data make it feasible to estimate the longevity and morbidity of different cohorts. As new data become available, estimates can be revised and any resulting costs spread broadly rather than being absorbed by individuals. This social insurance role for public policy will be discussed more fully later in the study.

Fourth, notwithstanding provincial/territorial leadership in care policy, the federal govern- ment plays a useful, albeit almost exclusively indirect, role in this sphere. Various subsec- tions of section 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 12 make it clear that each province is responsible for deciding what kind of care system it will develop, regulating that system, certifying the credentials of caregivers, fostering or developing the supply side (caregivers, institutions, etc.) and helping to ensure that it is funded. But the federal government is far from irrelevant. Federal powers related to taxation and old age pensions have considerable influence on the demand side of the care system. The federal spending power may also have affected the supply side through transfers to provincial governments, although the magnitude of any such effect is unknown. In short, on both the demand and the supply sides, the federal government has for the most part been an indirect player in the care system. Yet the anticipat- ed shortages of formal and informal caregivers will generate pressure on Ottawa to contribute financially to a solution.

Fifth, in deciding on whether and how it responds to these calls for financial support, the fed- eral government will have to take into account the economic status of seniors as well as the costs of care. But in fact, Ottawa lacks much of the information and analysis needed to make an informed and considered decision on the extent of its financial commitment.

Two kinds of information are required as a starting point. The first relates to the income and wealth of seniors in comparison with those of the working-age population. The government should not only have such information on a current basis, it should also have projections for the next two to three decades. The second concerns the costs of various care services, again looking ahead two to three decades.

The argument about the relevance of income and wealth is straightforward. Hypothetically, if the income of today’s seniors were double what it actually is, the vast majority of seniors would probably have the purchasing power to pay for much, if not all, of the care services they need.13 This stronger demand for paid care services would create incentives for both the voluntary and the business sectors to expand supply. In this scenario, the funding role of gov- ernments in care provision would assuredly be much smaller than is the case today.14 The opposite would apply if the current income of the elderly were half what it is.

In fact, Canadian seniors are now better off economically than they have ever been relative to the working-age population. The proportion of seniors with incomes below Statistics Canada’s low income cut-offs (LICOs) is less than half that of the population at large (Statistics Canada 2006a, charts 11-13). The proportion of seniors with low incomes after taxes fell from 10 per- cent in 1996 to 5 percent in 2006 (Statistics Canada 2008b). The main reason why so few sen- iors have low incomes is that the federal government’s Guaranteed Income Supplement provides benefits for couples aged 65 and older that are above the LICOs, although in some cases just barely above, depending on where the couple is living.

LaRochelle-CoÌ‚teÌ, Myles and Picot (2008) found that the median income replacement rate for all seniors in a cohort that they studied was equal to 80 percent of preretirement income. This exceeds the 65 to 75 percent replacement rate usually cited as the rate needed to maintain a standard of living in retirement equal to that experienced during one’s working years. They found considerable variation around the median, however, with over 20 percent of 75-year-olds having replacement rates below 60 percent, while 23 percent of those aged 69 to 71 had replace- ment rates over 100 percent. They also expressed concerns about whether current outcomes will be sustained in the coming decades — concerns that Wolfson (2011) has strongly reinforced. With respect to wealth, Statistics Canada reports that in 2005 the median net worth of families aged 35 to 44, 45 to 54 and 55 to 64 was $135,000, $231,000 and $407,000, respectively (Statistics Canada 2006b). The median net worth of those aged 65 and over was $303,000 and had improved relative to those of the other age cohorts since 1999.

This suggests that current seniors are faring reasonably well compared with the working-age population, although how adequate their retirement incomes will be when care expenses start to accumulate is another matter. Given the large proportion of elderly Canadians with disabili- ties reporting unmet care needs, it is probable that virtually all seniors with incomes below the LICOs, and many of those with incomes at or just above them, are unable to pay for private care services after retirement, even if they need only modest assistance. What is not known is how much of the reported care deficiency overall is due to shortages of caregivers, to seniors’ inability to pay for or access care services, or to other factors. To my knowledge, there has been no systematic assessment of the adequacy of the retirement income system in relation to the costs associated with different levels and durations of care.15 Future cohorts of seniors may fare reasonably well economically relative to the working-age population and yet have difficulty funding their care costs, given the policy status quo and the likely increases in the costs of care due to population aging.

The key point here is that the traditional analysis of the retirement income system has focused on two issues: its ability to prevent poverty and its effectiveness in enabling middle- income earners to maintain their living standards once they retire. A third question needs to be examined given ongoing demographic trends: the anticipated effectiveness of the retire- ment income system for future cohorts of retirees in relation to the anticipated care needs. Without such analysis there is little basis for Ottawa to decide what the extent of its contribu- tion should be, if any, remembering that there are many calls on the public purse.

Sixth and finally, as part of its strategy, Ottawa should concentrate on ensuring a better bal- ance between the demand and the supply sides of the care market. Demand-side measures are those that increase the purchasing power of the elderly and therefore their ability to buy the services they need in the marketplace. These include cash transfers and income tax provisions targeting seniors.16 Supply-side measures are government initiatives designed to add to the pool of care services, including formal and informal caregivers and various types of seniors’ accommodation. An example would be capital grants to increase formal caregiver training or the stock of appropriate housing. Indirect measures might include grants or subsidized loans, typically for the same purposes, but channelled through provincial/territorial governments.17

As will be seen below, the federal government concentrates almost all of its activities on the demand side. It may wish to continue doing so, premised on the view that a demand-side focus is the most appropriate way of respecting the constitutional division of powers. Whether it pursues or modifies its demand-side role, however, Ottawa should at least consid- er whether it has the means to leverage improvements on the supply side, in consultation with the provinces/territories, in anticipation of the caregiver shortages described above.

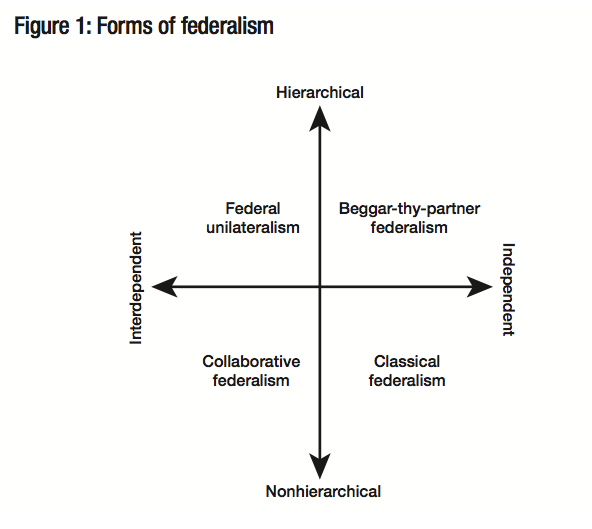

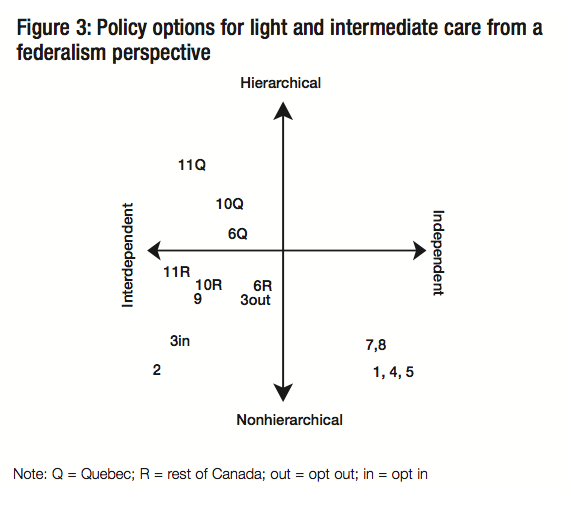

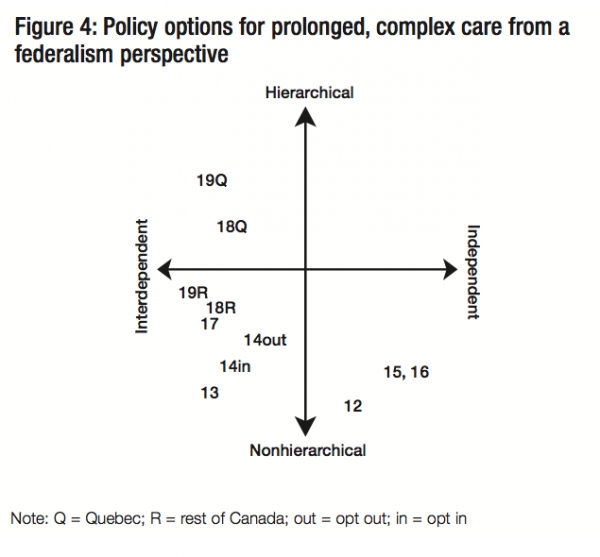

The classification of intergovernmental regimes is based on two sets of variables: the extent to which the federal-provincial relationship entails either independence or inter- dependence, and the extent to which it is hierarchical (coercive) or nonhierarchical (Lazar 2006). Figure 1 illustrates the classification system; each quadrant represents a distinctive form of federalism.

From the broad perspective of Canadian federalism politics, federal program initia- tives that fit within the two regime types below the horizontal axis tend to be rela- tively benign. Classical federalism occurs when one or even both orders of govern- ment are acting within their constitutional sphere, and the actions of one require little or no response from the other — this is sometimes called “disentangled” federalism. The federal role in defence and the provin- cial/territorial role in primary education are examples of governments acting within their areas of constitutional competence and requiring no response from the other order of gov- ernment. (This does not mean that these competencies are hermetically sealed from each other, as becomes clear when Ottawa closes a defence base or makes a major military purchase.) The advantages of this form of federalism are that it is consistent with the constitutional division of legislative powers, it makes accountability clear, and it avoids the heavy intergovernmental transaction costs that occur when there is extensive interaction between orders of government.

Despite these advantages, it should come as no surprise that in a world of growing functional interdependence, a lot of domestic program activity involves both orders of government. Collaborative federalism — when noncoercive federal-provincial/territorial relations are involved — can be very demanding. Examples over the last couple of decades include the Infrastructure Stimulus Fund, the National Child Benefit, and Canada Student Loans and Grants. Transaction costs are incurred in the form of heavy demands on the time of public ser- vants at both government levels and budgetary outlays for travel and communications. Collaborative federalism may entail negotiations that are never-ending, albeit with peaks and valleys, in much the way that the end of one round of collective bargaining in industrial rela- tions can lead almost immediately to the staking out of positions for the next round. Since collaborative federalism presumes no coercion, it is also analogous to efforts to manage inter- national relations without a hegemonic power.

While the effects of collaborative federalism on intergovernmental political relations are normally positive, and public opinion data frequently indicate that Canadians want their governments to cooperate, it is not uncommon to hear senior civil servants at both levels muttering privately that they would prefer the disentangled relationships that are more typ- ical of classical federalism.

Regimes above the horizontal axis are another story. They can create a lot of tension in the federation. Federal unilateralism arises when Ottawa exercises its spending power in an area of provincial/territorial constitutional competency without the uncoerced agreement of the provinces/territories. If Ottawa effectively coerces a province/territory to adopt a program that it otherwise would not have implemented through the incentives associated with matching grants, it is displaying federal unilateralism. The province/territory cannot afford to ignore the incentive, because if it does, its residents are effectively subsidizing Canadians in the rest of the country. Several provinces judged that Ottawa’s 2000 Affordable Housing Program, which was a matching grant program, entailed this kind of coercion. Of course, what some provinces/territories view as desirable federal uses of the spending power, others view as unde- sirable. The Quebec government has consistently rejected the idea that such a federal constitu- tional power exists (Quebec 1998), while the Alberta government has almost as consistently rejected its political legitimacy.

“Beggar-thy-partner federalism” is rare but not entirely absent from domestic intergovernmen- tal relations. It differs from federal unilateralism in that the initiative taken by Ottawa is within its constitutional competency. The coercion arises from the fact that the federal government’s action or inaction imposes costs on the provinces/territories with minimal discussion or con- sultation. For example, to the extent that the federal government does not provide or arrange for the provision of adequate services for “Indians, and lands reserved for the Indians,” for which it is constitutionally responsible (section 91 [24]), First Nations people who might have preferred to remain on reserve feel compelled to move off reserve to cities, leading to additional cost pressures on the provinces/territories for education, health and social services. It can also arise when Ottawa takes decisions to do more of something within its competency that effec- tively forces costs onto the provinces/territories. An example would be an amendment to the Criminal Code creating new offences, which adds administrative costs to provincial/territorial judicial systems without Ottawa negotiating to assume some share of those incremental costs.

The key objective of this study is to assess seniors’ care policy options for the federal govern- ment and their effects on Canadian federalism. But in the real world of government decision- making, many other assessment values or criteria are considered before a new social policy initiative is launched. Accordingly, potential policy options are examined from a broader pub- lic policy perspective, taking into account the following 10 criteria:

Notwithstanding the dominant role of the provinces/territories in legislating and regulat- ing care, Ottawa has had some influence on the way that caregiving arrangements have evolved in Canada since the Second World War. Although the federal role is significant, as noted above and as will be seen further below, it is almost entirely indirect. As the effects of population aging start to be felt in all regions of the country, the electorate will more than likely demand that the federal government do a lot more to manage the adjustments required. What in fact has Ottawa done historically, and what is it doing now?

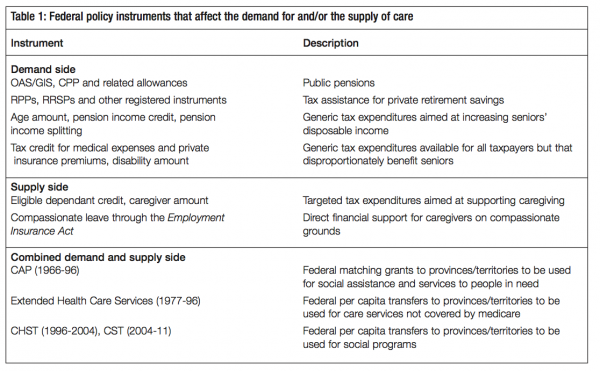

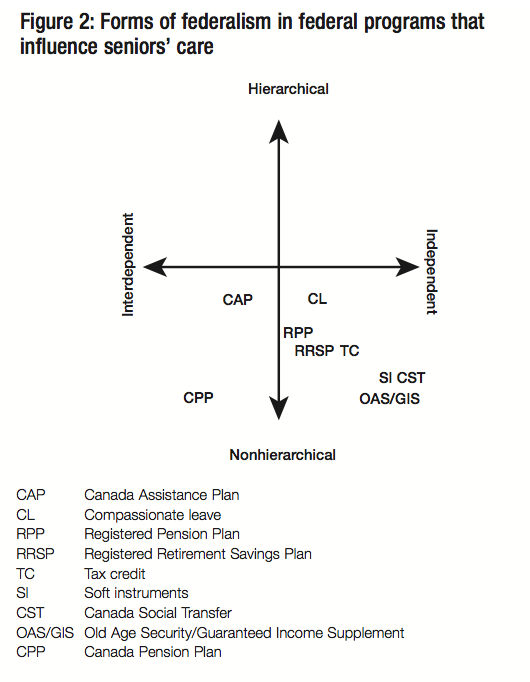

Although there are particular groups for which the federal government has special respon- sibilities, including the growing number of war veterans and First Nations people on reserves, this section focuses on the broader issue of what the federal government’s role in caregiving has been for elderly Canadians, writ large, and how much additional policy freedom it has within the federal system. Table 1 lists the main policy instruments that Ottawa has used for purposes related to care or that have impacted on care, even if they were not intended specifically for that purpose.

Ottawa influences the caregiving system chiefly by shaping the country’s retirement income system and administering most of its largest programs. Even though provincial laws in respect of old age pensions constitutionally trump federal laws (see section 94A), Ottawa has historically been the lead political actor in creating the retirement income sys- tem. A principal source of income for current retirees is the public pension system. This includes Old Age Security (OAS), which dates from the early 1950s; the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), both of which were enacted in the 1960s; as well as spousal and survivor allowances, which were developed mainly in the 1960s and 1970s. These are Canada’s largest statutory expenses and, including the Quebec Pension Plan (QPP), in 2008, they were paying out in the order of $60 billion annually (Finance Canada 2009, tables 10 and 39, adjusted to include CPP/QPP retirement pensions only). With regard to the CPP/QPP, it should be noted that these plans pay not only retire- ment pensions but also, and more significantly in terms of caregiving, disability pensions.

The federal government has also played a decisive role in encouraging private retirement sav- ings and pensions for current retirees, through income tax incentives for Registered Pension Plans (RPPs), Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs) and a number of related instru- ments. In the mid-2000s, these registered private plans provided over $40 billion annually in income to Canadian retirees and were growing more rapidly than the public plans. Gross fed- eral revenue forgone in 2009 for these two programs was close to $30 billion (Finance Canada 2009). The stock market sell-off in 2009 adversely affected this important source of retirement income, and the long-term effects of that event for future seniors remain uncertain.

Taken together, the public and tax-assisted private pension systems account for an estimated 60 percent of the income of people in their late 60s. This share rises to 70 percent for older seniors as the number of those still working dwindles.18 Compared with the situation in other OECD countries Canada’s public pension system has strong antipoverty characteristics, but it provides relatively weak earnings replacement for middle- and high-income individuals. While pension policy reforms are unlikely to focus on the highest earners, the middle-income groups are a potential target for improvements to the retirement income system.

Several provisions of the federal Income Tax Act also influence the income situation of seniors. The “age amount” can be viewed as a way of helping seniors fund their own care by recognizing that they must bear the added health-related costs of growing older, although, as with the OAS, the age amount targets low-income and low-middle-income taxpayers. The age amount was projected to reduce federal revenues by over $2.2 billion in 2009. The pension income credit (worth $945 million in 2009) and the relatively new pension income-splitting provisions ($730 million in 2009) have similar impacts in that they reduce the tax burden of retirees, leaving them better able to finance their needs (Finance Canada 2009).

There are other tax expenditures that are relevant to this discussion. For example, under the Income Tax Act, out-of-pocket medical expenses above a specified threshold for taxpayers or their spouses are eligible for nonrefundable tax credits. So too are the costs of private health insurance. Also, a “disability amount” can be claimed as a nonrefundable credit by persons certified as having a physical or mental disability that is severe and prolonged and requires care. The projected federal revenues forgone for medical expense tax credits and disability credits in 2009 were $945 million and $415 million, respectively (Finance Canada 2009). Obviously these two credits are not restricted to seniors, but they are more closely related to the demand for care services than, say, the age amount or the pension income credit.

Two small provisions have a clear supply-side focus. An “eligible dependant credit” is available to a taxpayer who supports and lives alone with a dependant in a home that the taxpayer maintains. Revenue forgone for that program in 2009 was projected at $765 million. There is also a targeted “caregiver amount,” which is a nonrefundable credit of up to just under $4,200 annually that a taxpayer can receive in respect of a close relative who is dependent on the tax- payer, if the dependant has a relatively low income. The projected cost of this provision to the federal treasury in 2009 was only $85 million.

In the context of this study, all but the last two of these tax provisions are generic in the sense that they are focused not on caregiving explicitly but on putting or leaving money in the hands of seniors or retirees, thus making it easier for them to purchase what they need, including care services. The fact that the current Conservative government has enriched these generic provisions by allowing for pension income-splitting and a doubling of the age amount suggests that its policy strategy has become increasingly focused on a demand-side approach. It is also a middle-class strategy, since essentially none of these credits is refundable (that is, they are of no value to low-income families and individuals who do not pay federal income tax), and they therefore do not help the poorest of the elderly.

While at first glance these tax expenditures, totalling about $5 billion annually, may seem sig- nificant, they pale in relation to the $60 billion annually in direct expenditures on public pensions and the more than $40 billion of private pension income derived from registered savings vehicles.

In summary, the federal government has a major impact on the demand side of the care sys- tem, even though its policies have not been established for that purpose. For all the big-ticket expenditures — and some of the smaller ones — in the retirement income system, federal poli- cy has not been designed with reference to probable care needs. Indeed, in a retirement income system that directly and through tax assistance provides roughly $100 billion of income annu- ally to Canadian seniors, perhaps 1 percent can be thought of as having some direct link to the demand side of caregiving. Yet, regardless of intent, Ottawa’s policies have a large influence on the size and distribution of the demand side of the care system for the elderly.

As for the supply side, historically the federal government has played at best a marginal role. (It may have had some indirect effect through the matching grant provisions of the Canada Assistance Plan [CAP], which will be discussed below, but with the disappearance of CAP in 1995, any such influence ended.) As with the demand side, the tax expenditures that current- ly target the supply side equal less than 1 percent of federal outlays for retirement income.

With regard to the effects of these federal programs on the federation and on intergovernmen- tal relations, one should bear in mind that while in the case of old age pensions Parliament has the explicit constitutional authority to legislate, provincial law prevails if there is a con- flict between the two orders of government. In this sense, Ottawa’s spending and tax expendi- ture programs for the current retired population are not coercive toward the provinces/territories. Indeed, apart from the intense intergovernmental negotiations in the 1960s that resulted in the CPP and the parallel QPP, the provinces/territories have generally looked to Ottawa to provide leadership in this area.19 This may be in part because the federal government has operational responsibility for public pension programs, but it is also because it has to concur with the provinces on CPP amendments.

The federal government has thus had a major indirect impact on the demand side of the care system for current retirees, and the situation can be expected to be the same for future retirees. The benign effect of federal retirement income programs on intergovernmental relations could remain unchanged as well. This is because the federal programs that underpin the incomes of all but the oldest of the current elderly are the same ones that will underpin the incomes of the future elderly. The CPP and the QPP are now mature programs and, in relative terms, their future growth will be linked mainly to population aging. The OAS and the GIS are not funded contributory schemes, and the statutory commitment to maintain the income they provide relative to wage growth is weaker than that for the CPP/QPP. But over the decades Ottawa has acted periodically to keep the real value of GIS benefits stable relative to wage growth (an easy task in recent years given the absence of real wage increases). In fact in the 2011 budget the government announced modest increases in the GIS. The key point here is that the federal government is acting within its constitutional powers in all of these pro- grams, which accounts for the benign intergovernmental relationship.

There are two reasons to think that this amicable relationship could change. The first is that over the past few years some of the weaknesses in the retirement income system have become more transparent. For people who were near their planned date of retirement when stock mar- kets tumbled in late 2008 (as a result of the international financial crisis), and who had been saving for retirement through RRSPs or defined contribution pension arrangements, their vul- nerability to the vagaries of the market became all too apparent. Deficiencies in supervision of defined benefit plans caused adverse effects on others when the pension plans of failed com- panies were terminated without sufficient assets to meet liabilities. At the same time, the low interest rates that have now prevailed for some time are having a drastic effect on the living standards of those seniors who draw a substantial portion of their retirement income from the interest on bonds and guaranteed income certificates.

These difficulties led some provinces to launch discussions with Ottawa with a view to enlarg- ing the CPP. In 2009 the Council of the Federation “called on the federal government to host a national summit on retirement income” (2009). In December 2010 six provinces requested that Ottawa “keep a modest CPP enhancement on the table as part of a package of reforms that would make saving for retirement easier, more affordable and more secure for Canadians” (British Columbia 2010). These provinces still appear to be interested in pursuing this idea, although the federal government and the other four provinces are seemingly less enthusiastic. In any case, if current concerns about declining RPP coverage and use of RRSPs and the diffi- culties with pension regulation are not addressed, the role of the CPP/QPP could be revisited (Ferley, Janzen and Onyett-Jeffries 2010; Baldwin 2011; Wolfson 2011). In such a scenario, intergovernmental tensions could arise due not to Ottawa intervening in provincial jurisdic- tion, but rather to provinces/territories pressuring the federal government to do more in an area of shared jurisdiction.

The second potential source of tension is the near certainty that rising care costs will put a strain on the budgets of the provinces/territories, causing them to pressure the federal govern- ment to help by transferring fiscal resources or otherwise absorbing part of the growing costs of care for seniors. This source of tension is of course linked to the first. If the deficiencies in the retirement income system prove to be more than transitory, the provinces/territories will be under even more pressure to increase their financial support of the care system.

The federal spending power is the main instrument Ottawa has used to provide assistance to the caregiving community. Historically, the most significant of its initiatives was the Canada Assistance Act, 1966. It authorized the federal government to enter into bilateral agreements with provinces to cost-share social assistance and social services on a 50-50 basis, provided that the assistance and services were for people “in need.” The initiative for CAP rested as much with the provinces as with Ottawa or more so (Osborne 1985). CAP was an improve- ment over the three categorical matching grant programs that preceded it. All provinces signed agreements with the federal government, which effectively left them free to define “need” as they saw fit, subject to commitments on interprovincial mobility, an appeal proce- dure and the requirement that the delivery agent of provincial programs be the province, a nonprofit agency approved by the province or a municipality. Ottawa’s basic role was to verify that expenses claimed by the provinces as eligible for cost-sharing were indeed eligible.

Seniors were not major beneficiaries of CAP. Relatively few persons aged 65 and over were considered in need, since federal GIS benefits generally assured them a higher level of income than that provided by provincial social assistance. As for CAP’s role in respect of services, this depended on provincial priorities. Given the age structure of the Canadian population in the 1960s and the fact that governments’ attention at the time was focused on establishing or developing medical insurance, post-secondary education and the retirement income system, care for seniors could not have been a priority for social service ministries.

Nonetheless, even though cost-sharing programs for seniors were but a small part of CAP, it was the main federal program for that purpose. Thus, Sherri Torjman points out that CAP cre- ated a “national legislative base for the support of social services,” including “essential support to help seniors and persons with disabilities to live independently in communities” (1997, 3). Yves Vaillancourt argues that CAP had a steering effect, in two ways: its cost-sharing provi- sions created incentives for Quebec and other provinces to focus their care policies on low- income families, possibly to the detriment of the middle class; and over time, CAP rules relating to delivery agents encouraged the growth of the third sector in Quebec, possibly at the expense of for-profit businesses (Vaillancourt 2003).

In terms of federal-provincial relations, it is safe to say that CAP, in and of itself, was relatively unobtrusive and less contentious than other matching grant programs of its era. But it was one of several federal matching grant programs introduced in the 1960s and, as we have seen, opinion was divided in the federation about the political legitimacy and, in the eyes of some, the constitutionality of using conditional grants to influence areas of provincial legislative competence under the Constitution (Tremblay 2000; Quebec 1998; Noël 2000a).

To address this concern, the federal government undertook not to introduce further programs of this ilk, and Parliament enacted the Established Programs (Interim Arrangements) Act, 1965 to remove some of the irritants of the conditional grant approach. This statute authorized Ottawa to enter into agreement with any province with which it had a cost-sharing arrange- ment, to enable that province to receive the federal share of costs in respect of certain estab- lished programs in the form of tax points instead of money. While opinions differ about the significance of this provision, at the time it enabled the federal and Quebec governments to deal with a political crisis in a manner that allowed both to claim satisfaction with the out- come (Kent 1988, 296; Vaillancourt 2003, 161). As is well known, only Quebec took up the tax-point offer at that time.

The 1977 fiscal arrangements saw the merger of federal transfers for hospital and medical insurance and post-secondary education into the new Established Programs Financing (EPF) block fund, with part of the federal contribution paid for in the form of a tax-point transfer. The 1995 federal budget merged CAP and EPF into the new Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST) block fund. The CHST was subsequently, in 2003, decomposed into the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) and Canada Social Transfer (CST), both block transfers. In fiscal year 2011-12, the CHT and CST cash transfers will total $27 billion and $11.5 billion, and they are legislated to grow by 6 and 3 percent annually, respectively, until 2013-14.

Often neglected in the recounting of this history is the fact that the 1977 fiscal arrangements included a new program to cover extended health services such as nursing home intermediate care, low-level residential care for adults, health aspects of home care and ambulatory health services not covered in the federal-provincial hospital insurance agreements. The payment consisted of a per capita amount and an escalator. This was not all “new money,” in that the Extended Health Care Services program replaced some services previously provided for under CAP. This arrangement is noteworthy in that the federal government explicitly took on a funding role in relation to provincial care programs. Extended care was rolled into the CHST in 1996, and thus disappeared as a separate program.

So, what does this familiar history say about the current federal role in caregiving through intergovernmental transfers? With the end of matching conditional grant arrangements and extended care, there no longer is a federal instrument that serves as an incentive for the provinces/territories to build up their care systems.20 In fact, without the matching grant, there is no link between the CST and provincial care programs for seniors. Once received in provincial/territorial treasuries, the federal transfer dollars become fungible.

The federal spending power can also be used to transfer payments directly to organizations for the purpose of providing care to seniors. The evidence suggests that this option is not being seriously pursued. Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC) currently administers New Horizons for Seniors, which acts as a clearing house for issues and ideas that pertain to caregiving, serves as an advocate for caregiving within the federal government, helps run the live-in caregiver program and transfers small amounts of money to community organizations that support a range of community-based initiatives to address social issues and barriers faced by people with disabilities (HRSDC 2009). The government announced in the 2011 budget that it was enhancing the New Horizons for Seniors Program with $10 million over two years to support projects that ensure seniors contribute to and benefit from activities in their communities (Finance Canada 2011).

In 2003 the Liberal government of Jean ChreÌtien amended the Employment Insurance Act to author- ize the payment of benefits to EI contributors for compassionate leave of up to six weeks to care for seriously ill relatives. To be considered seriously ill, a person must be “at risk of dying within 26 weeks,” as attested to by a physician. The benefits are aimed at caregivers involved in providing direct care, giving psychological support or arranging for care by a third party. Compassionate leave claimants in 2008-09 numbered just over 5,800. In total they received $9.9 million in bene- fits. This is a tiny program relative to retirement income programs and tax expenditures.

From a federalism viewpoint, this initiative is similar to the maternity benefits and parental leave provisions, whose constitutionality was challenged and which, notwithstanding their social poli- cy content, were ruled constitutional by the Supreme Court.21 There is little reason, therefore, to think the courts would view compassionate leave benefits differently. Thus it is appropriate, with- in the federalism classification system, to view this program as nonhierarchical, since it entails the federal government legislating in an area where it has constitutional authority.

All of the above federal policies, which entail legislation, regulation, spending or tax expendi- tures, can be viewed as hard policy instruments. The federal government also uses soft instruments, by commissioning reports, communicating information and research, and creating advisory bodies that may influence caregiving policies over the medium and long terms. The National Advisory Council on Aging is one example of a soft instrument. Established in 1980, it is mandated to assist and advise the minister of health (responsible for seniors) on all mat- ters related to the aging of the population and seniors’ quality of life. It issues periodic reports on matters of importance, but has little influence on federal policy. Its effects on the federal- provincial/territorial relationship are thus of no consequence.

The federal government also makes extensive use of task forces and commissions to structure debate on key issues. The reports of the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada (2002) (Romanow Report) and the Senate Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology (2002) (Kirby Report) raised the profile of home care and caregiving. Regular reports from Statistics Canada on the country’s demographic trends more or less draw public attention to the emerging care needs of our aging society. Such soft instruments may be influ- ential in the long run, helping to inform and structure the debate, even if they seem to have little impact in the short run. In themselves, they have not been significant sources of tension in the federation.22

What kind of intergovernmental regimes do these various federal programs represent? How do the programs compare in terms of their potential effects on the federation? Figure 2 summa- rizes the analysis.

All of the federal programs are nonhierarchical, with the great majority falling in the classical federalism quadrant. Given the benign effects that programs below the horizontal axis have on intergovernmental relations, it is no surprise that current federal programs that have an impact on caregiving are not a serious source of intergovernmental tension — either because they allow governments to act independently of one another or because their interdepend- ence is well managed.

The programs that have involved the provinces with the federal government are the CPP/QPP and CAP. The CPP can, by law, be amended only with the agreement of the government of Canada and two-thirds of the provinces representing a minimum of two-thirds of the Canadian population. This puts the CPP into the lower left quadrant: collaborative federalism. Efforts made by all governments to maintain parallelism between the CPP and the QPP are also collaborative.

In the days of CAP, there was considerable federal-provincial interdependence, if only because the provinces designed and delivered programs while Ottawa paid half the freight and audited provincial spending. On policy matters, including social services such as caregiving, the feder- al government did not meddle. In any case CAP no longer exists, and its putative replace- ment, the CST, is at best a distant relative. The difference between the CST and CAP from a federalism viewpoint is shown in figure 2. CAP was a collaborative, province-friendly pro- gram. The CST is even friendlier, given that it allows the provinces and territories to use CST funds as they choose. The CST fits into the classical federalism quadrant.23

In the case of the OAS/GIS, the tax incentives for RPPs and RRSPs, and the various tax cred- its, Ottawa acts independently of the provinces/territories.24 These federal programs therefore fall into the classical federalism quadrant. The tax credits under the Income Tax Act are within federal constitutional com- petence, and Ottawa acts in this sphere whol- ly or largely independently of the provinces/territories when it uses this power. RPPs are also in the classical federalism quad- rant. They are placed very close to the vertical axis only because the treatment they receive under federal tax law is, in the majority of cases, linked to the plans being registered under provincial law for regulatory purposes. But in fact there is little interaction between the federal and provincial administrations, as each has a distinct regulatory role.

The compassionate leave program is also close to the vertical line, since it is likely that a fami- ly facing the circumstances that make it qualify for these benefits will also be interacting with provincial/territorial social services agencies.

Finally, the way in which the federal government uses soft instruments is within its constitu- tional authority. And it uses them largely independently of the provinces/territories.

The federal government has implemented programs that have potentially influenced the care- giving field in recent years, and in a fashion that does not interfere unduly with provincial constitutional competence. The words “have potentially influenced” caregiving have been carefully chosen. The dollar amounts associated with these programs are in the tens of bil- lions. In no way, however, do the larger programs focus explicitly on caregiving; they simply provide money to seniors that can be used for that purpose. As for the federal transfers to the provinces, even under CAP and extended health care, these never involved the federal govern- ment in deciding how much the provinces should or could spend on caregiving or the design features of provincial caregiving programs. And with the demise of these two programs, the federal government broke all links between the funds it transfers to the provinces notionally for social services, including caregiving, and how the provinces use those funds.

In a sense, the benign impact that federal policies have had on intergovernmental relations is not surprising. Ottawa effectively recognizes the constitutional role of provinces/territories in caregiving and has not, by and large, participated directly in this sphere of activity. In spite of this, it has had an influence through its large retirement income programs, which have helped to shape the demand side of caregiving. From a federalism perspective, the demand side of the caregiver market is much less susceptible to intergovernmental tensions than is the supply side.

For those who attach primacy to the Constitution and the importance of harmonious inter- governmental relations, this is what they would expect to see. They prefer that the federal authorities not meddle in provincial/territorial legislative jurisdiction. Implicit in this position is that they would expect the provinces and territories to continue stepping up to the plate and to introduce and implement care policies as necessary.

For those who focus more on public need than on the niceties of the Constitution and expect Ottawa to lead in the event of a Canada-wide social challenge, the federal caregiving policy cupboard must look bare. This is simply because the federal government has in fact no real policy that impacts directly and purposefully on caregiving, beyond its tiny compassionate leave program and its few tax credits (the eligible dependant credit; the caregiver tax credit; and tax support for home-based caregivers and for medical and disability-related expenses). The feder- al government announced an additional family caregiver tax credit in the 2011 budget — a 15 percent nonrefundable credit on an amount of $2,000 to provide tax relief for caregivers of infirm dependent relatives. The 2011 Conservative Party platform estimated the costs of this additional initiative at $160 million annually — which indicates that this credit will make lit- tle difference to the lives of most caregivers.

Before presenting the policy options available to the federal government, it is worth not- ing one of the reasons for making a distinction between options for light/intermediate care and those for prolonged, complex care. Since many seniors require light or intermediate care at some point in their later years, it is reasonable to expect people to have anticipated some of these costs and to have saved during their working years for this purpose. Put differ- ently, some of the options related to light and intermediate care place the onus on the indi- vidual, whereas, for reasons explained below, all of the options aimed at the heavy end of the care continuum depend mainly on the state. For those concerned about the overall private- public balance in retirement-related programs, this may warrant extra consideration of the pri- vate options for light and intermediate care.

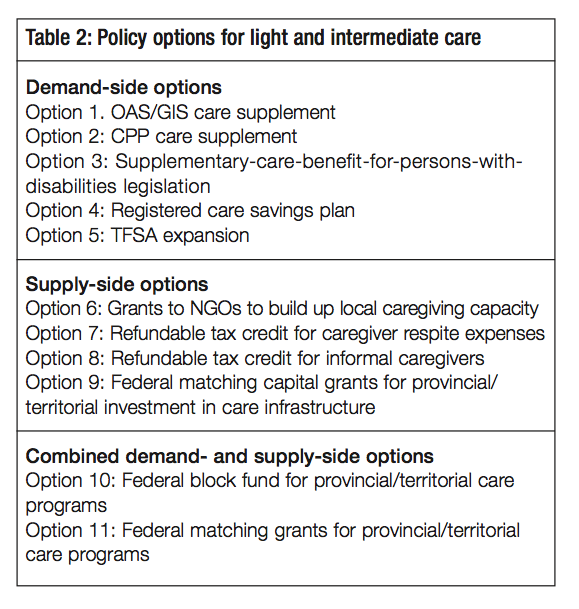

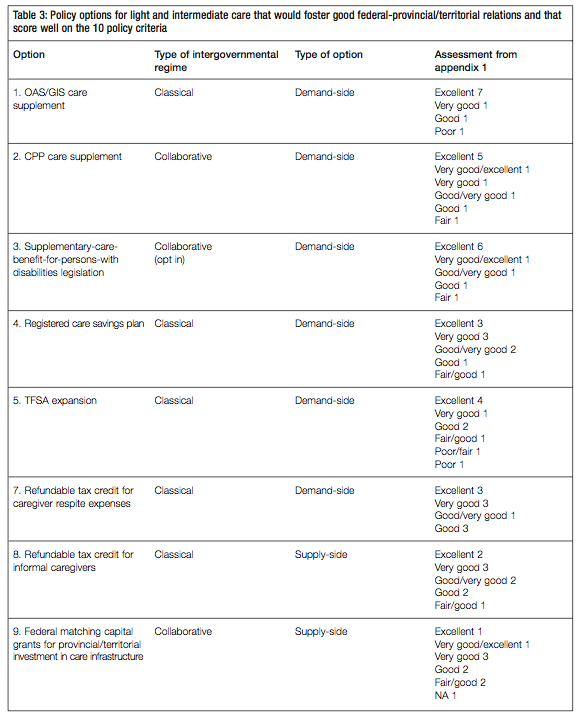

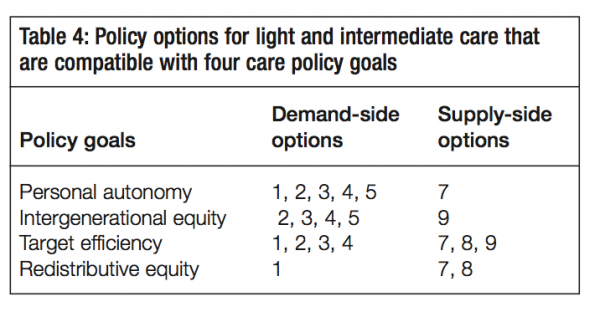

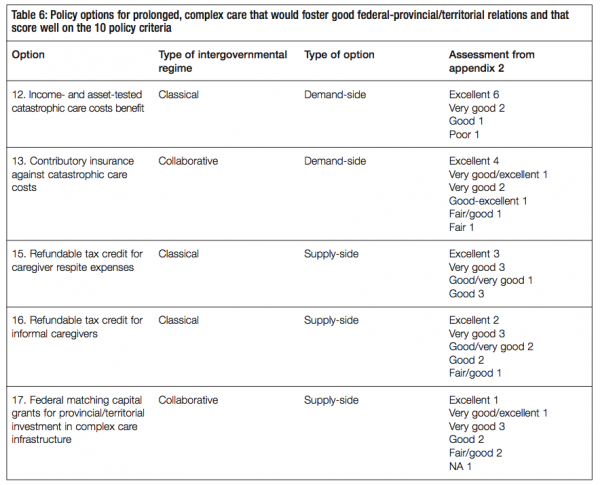

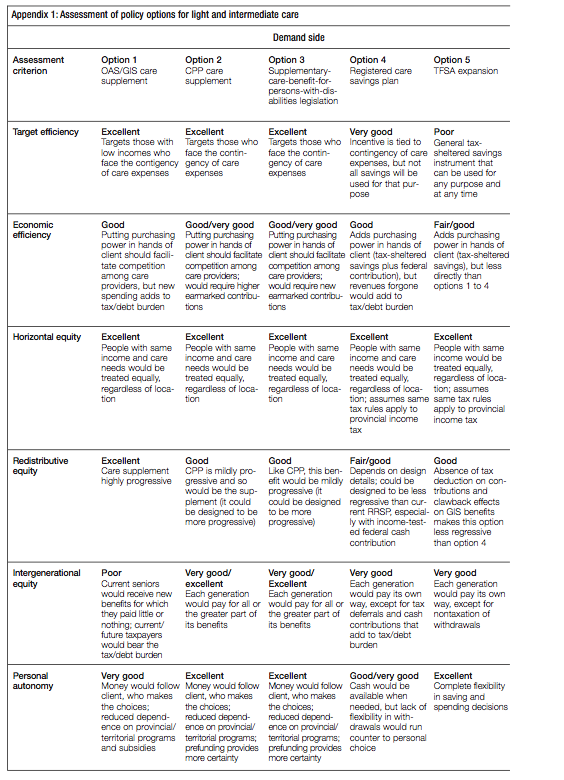

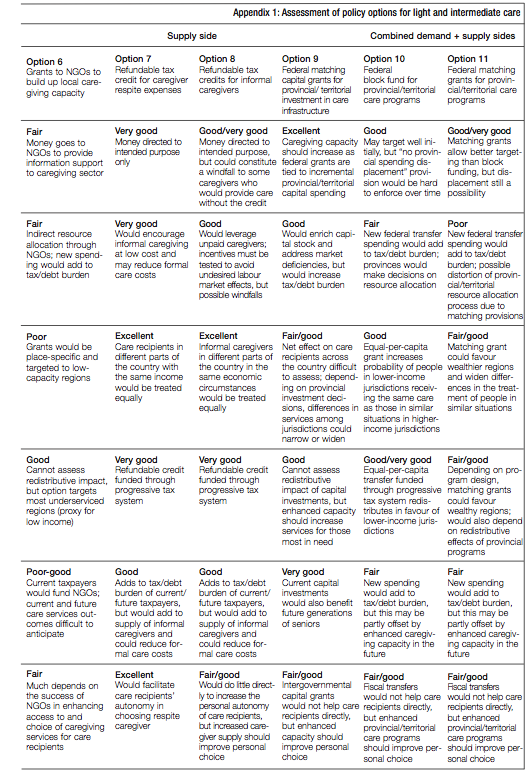

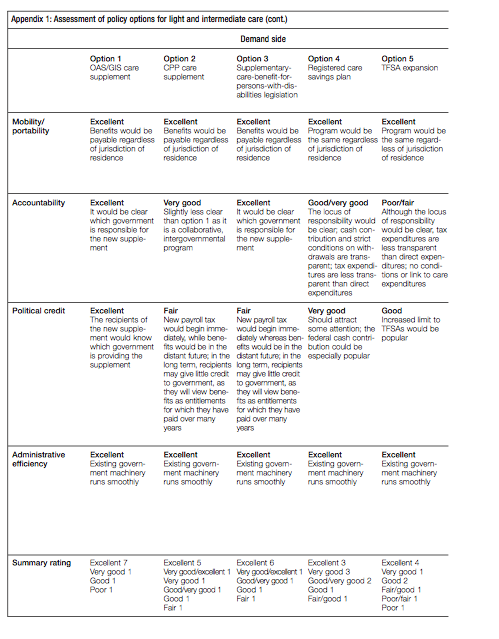

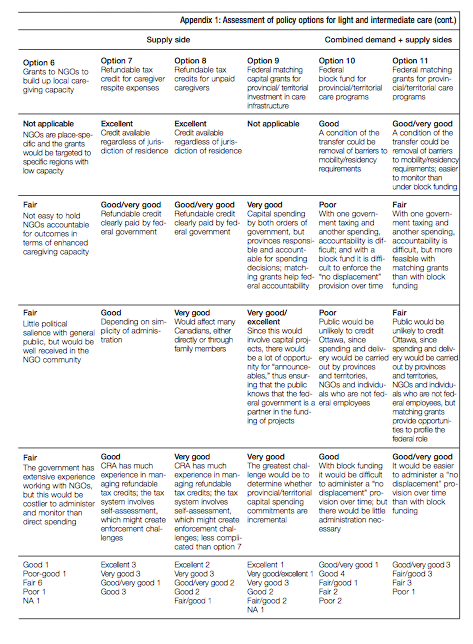

Policy options for the light and intermediate points of the care continuum are presented first. They include both demand- and supply-side measures. Here, the range of options includes con- tinuing with established programs, variations on these and some new ideas. They all anticipate a growing need for care, but they do not specify dollar amounts except for illustrative purposes.

Clearly, some of the policies I have laid out below are not priorities today. But these options are not straw men. They are set out to help explore alternative strategic approaches, using both a federalism lens and a broader policy perspective that includes familiar policy criteria like equity and efficiency. The objective is to encourage the federal government to think strategically about the range of policy choices that are possible looking to the future. The options are presented in table 2 and discussed in turn below.

This option would enable OAS/GIS recipients to qualify for a supplement to their current benefits if their care costs exceed some mod- est deductible — say, $500 annually for some- one eligible for the maximum GIS and $1,000 to $2,000 annually if they receive OAS only. The supplement would cover 100 percent of care costs in excess of the deductible for those receiving the maximum GIS, and the percent- age of costs covered would gradually decline to zero as income increases. A ceiling of, say, $5,000 annually would apply. In designing this benefit it would be important to avoid an overall tax-back rate that would be punitive (although since this measure would not

mainly be focused on workforce participants, incentive effects would be less of a worry than is the case for stacked programs for people of working age). The tax-back rate might also be more gradual for seniors living alone than for those with a partner, to reflect the probability that they would have less access to informal care. Like the OAS/GIS, the care supplement would be funded out of general revenues on a pay-as-you-go basis. It could also be implemented quickly.

One risk associated with this option is that provincial/territorial governments could increase the co-payments they require from people who are in long-term care residences or receiving other subsidized services in order to capture the federal supplement. Accordingly, consultations with the provinces and territories would be necessary before such a measure could be implemented. From a provincial/territorial viewpoint, it would simply mean that GIS recipients, and perhaps those slightly beyond that threshold, would have additional income to purchase services. Even without adjusting their co-payment rates, the provinces/territories would have fewer seniors to subsidize under this option.

The rationale for such a measure is threefold. While relatively few elderly couples’ incomes are below the LICOs, a substantial number are only modestly above these levels, suggesting that they have little discretionary income, including for the purchase of care. Second, the problem is greater for unattached individuals who, because they lack a partner, do not have the finan- cial benefit of sharing accommodation or immediate informal care support should the need arise. Finally, seniors who rely heavily on the OAS/GIS are also the most likely to require provincial/territorial subsidies should they need care. With this care supplement measure, far fewer seniors would have to plead their case with provincial/territorial officials; they would be more autonomous.

This option could also be delivered through the mechanism of a refundable tax credit under the Income Tax Act.

Unlike the OAS and the GIS, which are linked antipoverty programs, the CPP and the QPP are intended to replace a portion of pre-retirement earnings. The benefits are very modest in size in that they replace only 25 percent of preretirement earnings, and only on earnings up to the national average wage ($47,200 in 2010). The design of these public pension plans was premised on the assumption that, during their working years, people would also avail them- selves of RPPs and RRSPs in order to have a retirement income sufficient to maintain their standard of living after retirement.

Like option 1, this option would put more money into the hands of seniors, contingent on their annual care expenses exceeding a deductible amount. But since the CPP is an earnings-related program, this care supplement would effectively target people with a stronger employment history than those targeted under the OAS/GIS option. As with the first option, the maximum supplement might be $5,000 annually (adjusted by a wage index). It would be funded through mandatory increases in CPP contribution rates.

Unlike option 1, the CPP care supplement would not be income-tested. It would be earned and paid for by the beneficiary as a contingent entitlement in much the way that CPP contributors are entitled to a disability pension under certain conditions. In other words, it would become payable when the beneficiary begins to incur care costs and could be modelled on disability benefits (combination of base amount and a contribution- linked supplement). Since it takes many years of contributions to pay for and thus earn a full benefit in a contributory plan, another important difference from option 1 is that full benefits would not become available for decades (how many is a design detail with vast financial implications).