Craig Forcese rappelle que le Parlement du Canada a adopté la Loi antiterroriste (LAT) de 2001 à toute vitesse (en un peu plus de deux mois), réagissant sans attendre aux événements du 11 septembre et à l’adoption de la résolution 1373 du Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies.

Or, de nombreux événements qui se sont produits depuis suscitent les mêmes préoccupations que celles qui ont animé le débat sur la LAT.

Le Parlement et les parlementaires n’ont ni le temps, ni les ressources, ni, parfois, l’inclination voulus pour saisir pleinement la complexité et les répercussions éventuelles de toutes les dispositions comprises dans un projet de loi omnibus. Ils ne sont pas toujours à même de prévoir toutes les difficultés ou de parer à toutes les lacunes qu’il peut présenter.

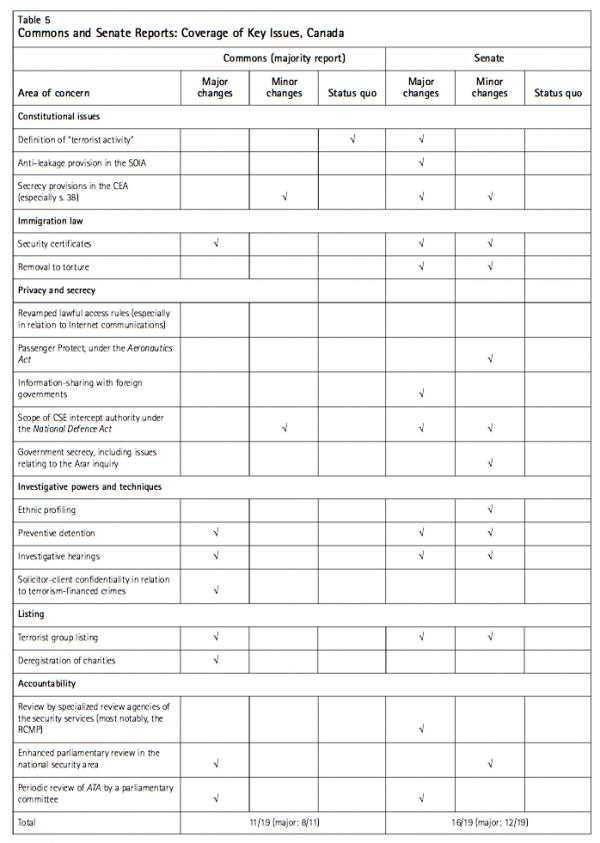

Il semble bien, ajoute l’auteur, que l’examen parlementaire de la LAT mené de 2004 à 2007 ait confirmé cette conclusion. Les deux comités chargés de cet examen — l’un rattaché à la Chambre des communes, l’autre au Sénat — ont produit de longs rapports qui, à l’occasion, traitent même des questions de fond, mais avec un retard de plusieurs années. La composition du comité des Communes, en particulier, a sensiblement changé entre le moment où la plupart des témoignages ont été déposés et la rédaction du rapport du comité. Contrairement au rap- port du comité sénatorial, le rapport majoritaire du comité des Communes ou bien passe sous silence un certain nombre de questions qui ont soulevé des polémiques depuis le 11 septembre, ou bien ne formule aucune recommandation à leur égard. Les délibérations des deux comités n’ont guère influé sur les débats âpres et parfois simplistes qui ont eu lieu en février 2007 à propos de la prorogation de deux dispositions de la LAT assorties de clauses de temporisation, soit celles concernant les audiences d’investigation et la détention préventive.

Le Parlement canadien n’est pas le seul à devoir composer avec ces problèmes. L’expérience d’autres démocraties « à la Westminster » offre des leçons utiles en ce qui a trait aux examens parlementaires des mesures antiterroristes. Le Royaume-Uni et l’Australie, notamment, ont mis en place des mécanismes qui semblent bien supérieurs au système canadien.

Un élément crucial qui distingue l’approche adoptée par ces deux pays de celle qui est en vigueur au Canada est ce qu’on pourrait appeler une « expertise préalable », c’est-à-dire une évaluation publique de la loi antiterroriste par un expert ou un comité indépendant, soit avant son adoption, soit sur une base périodique après l’adoption, dans le but d’aider à encadrer et focaliser les délibérations parlementaires. Un second élément réside dans la création, au Royaume-Uni et en Australie, de comités statutaires spécialisés, composés de parlementaires (il ne s’agit pas ici de comités parlementaires au sens habituel du terme), qui ont pour mandat de passer en revue la législation nationale sur la sécurité.

Les procédés d’évaluation employés à Westminster et à Canberra présentent un intérêt certain lorsqu’on les compare au bilan plutôt pitoyable du dernier examen de la LAT au Canada. Une expertise préalable, si elle est suivie d’une analyse par un comité parlementaire stable qui dispose de ressources adéquates, pourrait aider à éviter certaines des difficultés qui ont surgi au cours de l’examen de la LAT, en particulier au niveau de la Chambre des communes.

L’auteur estime qu’un examen mené de cette façon éliminerait les problèmes soulevés par la complexité et la portée des lois antiterroristes. Une instance d’évaluation indépendante dotée d’un vaste mandat pourrait signaler des lacunes et des difficultés qui, sans cela, risqueraient d’échapper à l’attention des comités parlementaires.

La publication de rapports annuels ou spéciaux d’un évaluateur indépendant sur plusieurs années pourrait également contrer la « normalisation » graduelle des lois et pouvoirs antiterroristes, c’est-à-dire la possibilité que ces lois en viennent à disparaître peu à peu du discours public et à ne plus faire l’objet d’un examen attentif dans le recueil de lois canadiennes. Ces rapports pourraient en outre susciter une réflexion politique plus fréquente (et plus transparente) au sein de la branche exécutive de l’État, comme cela semble s’être passé au Royaume-Uni.

En mettant en exergue les principaux enjeux de la législation antiterroriste, l’expertise préalable pourrait également atténuer l’impact des changements de la composition des comités parlementaires : quelle qu’en soit la composition, en effet, les comités pourront difficilement passer sous silence les observations formulées au cours de l’examen.

L’expertise préalable pourrait par ailleurs aider à soustraire les délibérations parlementaires sur les questions antiterroristes aux querelles partisanes. Il sera difficile de ne pas tenir compte des avis d’un évaluateur indépendant et crédible, ou de lui attribuer des motifs partisans.

Tout compte fait, on voit difficilement quels pourraient être les inconvénients d’un système d’expertise préalable établi sur des assises crédibles. Les délibérations politiques portant sur la législation antiterroriste ne pourront que profiter d’une information et d’une évaluation plus abondantes.

In many areas of government, parliamentary committees play a key role in holding ministers (and, de facto, their officials) to account. The Canadian Parliament has powers to summon and even compel the appearance of officials,1 including ministers.2 Likewise, committees may “send for persons, papers and records”3 and Parliament and its committees may administer oaths requiring truthful responses.4 Parliament (and by extension its committees) also possesses contempt powers.5

All this suggests that parliamentary committees can be potent review bodies in the area of national security. To date, however, parliamentary review of national security matters has been largely perfunctory. Both the Senate and the House of Commons have national security and defence committees.6 The Senate committees in particular have been active in holding hearings and producing reports on various aspects of Canada’s national security and defence policy. Most recently, the Commons national security committee held hearings examining the role of the commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in the Maher Arar matter, a focus precipitated by the findings of the Arar inquiry and fuelled by apparent contradictions in the commissioner’s testimony. Controversy sparked by these hearings culminated in the commissioner’s resignation in late 2006.

Parliamentary committees — and Parliament as a whole — have not, however, played a systemic or concentrated role in reviewing Canada’s national security and defence policies. Indeed, some critics describe their performance as utterly inadequate (see, for example, Bland and Rempel 2004). The 2004-07 parliamentary review of the Anti-terrorism Act (ATA)7 does little to alter this conclusion. While the reports issued by the two committees — Commons and Senate — charged with reviewing the legislation are lengthy and in many places substantive, they were delayed by years. The Commons committee in particular underwent a turnover in membership between the point at which most evidence was heard and the drafting of the report. The majority report of the Commons committee, unlike that of its Senate counterpart, ignored or failed to articulate recommendations in a number of controversial areas since the attacks of September 11, 2001 (9/11). The deliberations of neither committee proved influential in the acrimonious and at times simplistic February 2007 debate over the extension of two sunsetting provisions of the ATA.

The impact of the reports on future government and parliamentary action in relation to antiterrorism law remains unclear.8 While the government responded to the Commons report in July 2007, its response was unenlightening, both because it reacted to recommendations that were themselves often minor and technical and because it cited the need for further consideration in relation to the major proposals. Even at this early juncture, however, one can draw conclusions from the process surrounding the ATA review about the future of parliamentary review in the national security area. In his exhaustive analysis of this process, Kent Roach concludes that “parliamentary and public debates about national security matters should be becoming more sophisticated and nuanced as we move away from 9/11 and devote more resources and thought to national security matters. Unfortunately they seem to be getting less substantive” (Roach 2007, 29).

Roach’s conclusion raises the question of whether parliamentary participation in national security decision-making can be enhanced in such a way as to contribute meaningfully to policy development. This article takes up the question in three parts. In the first part I examine in detail the ATA review, building on Roach’s review and comparing and contrasting the Commons and Senate reports. I evaluate the quality of these assessments by gauging the extent to which each grappled with a series of flaws and uncertainties in the terrorism law that have emerged since 2001. In the second part I analyze the comparative experiences of the United Kingdom and Australia with regard to parliamentary participation in national security policy-making. Drawing on this analysis, in the third part I suggest a revamped Canadian parliamentary review role with respect to national security policy and law-making.

Parliament’s scrutiny of the average bill occurs during its promulgation as a statute. In Canadian practice, government bills are devised and drafted within the executive and are tabled in Parliament in the form that is most pleasing to the government. In majority Parliaments, a government bill typically passes through both houses with few changes. In minority Parliaments, outcomes are less certain and government bills are recrafted, sometimes dramatically, by parliamentary committees (typically after second reading, but more aggressively in cases where the bill is routed directly to committee after first reading).

Parliamentary committees are subsets of Parliament tasked with the detail work. In the Commons, their terms of reference are established by standing orders and special orders. While there are six different types of standard committee, standing committees are the most important vehicle for committee work in the Commons.9 Pursuant to the Commons standing orders, for example, standing committees are “empowered to study and report on all matters relating to the mandate, management and operation of the department or departments of government which are assigned to them from time to time by the House.” Among other responsibilities, they are charged with reviewing “the statute law relating to the department assigned to them.”10

In most cases, parliamentary scrutiny ends with the enactment of the bill as a statute. There is nothing to stop parliamentary committees from subsequently scrutinizing statute law lying within their mandate, assessing its performance and utility. In practice, however, unless and until amendments to (or repeal of) a law are considered desirable (usually via another government bill), at some point in the future, Parliament has no further role to play in relation to the statute. There are two notable exceptions to this pattern. One is that the law may include sunsetting provisions, automatically terminating some or all provisions of a statute by a particular time unless there is further parliamentary intervention. The other is that the law itself may oblige Parliament to reconsider its provisions by a given date, by mandating a parliamentary review. As we shall see, both of these exceptions were incorporated into the 2001 Anti-terrorism Act.

National security law — including anti-terrorism law — presents special challenges to the conventional parliamentary process.

First, anti-terrorism law is sometimes promulgated in times of crisis and with a sense of urgency. This can serve to create a poisonous political environment. As Lynch observes of the Australian experience, “The stakes are always raised in respect of counterterrorism laws because to oppose or seek amendment of these Bills is to risk being portrayed as exposing the community to unnecessary danger” (2006, 776).

Further, debate over terrorism laws may be coloured by perceived or real external political or legal pressures. For example, Parliament promulgated the ATA at dizzying speed, in just over two months, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 and UN Security Council resolution 1373.11 This resolution, issued via the Security Council’s potent UN Charter chapter VII powers, effectively imposes the substantive obligations of the 1999 international terrorist financing convention. Its writ is even broader, however, and in some respects it constitutes a universal, comprehensive anti-terrorism instrument. It requires states to “ensure that any person who participates in the financing, planning, preparation or perpetration of terrorist acts or in supporting terrorist acts is brought to justice and ensure that, in addition to any other measures against them, such terrorist acts are established as serious criminal offences in domestic laws and regulations and that the punishment duly reflects the seriousness of such terrorist acts” (emphasis added).

Resolution 1373 was, clearly, the impetus behind the ATA. The deputy prime minister told a parliamentary committee in 2002, “The Anti-terrorism Act is an unprecedented piece of legislation and brings Canada into full compliance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1373.”12 Likewise, Canada’s justice minister told a parliamentary committee in 2005 that specific offences were included in the ATA to comply with the Security Council’s dictates.13 In its reporting to the UN Security Council’s Counter-Terrorism Committee, Canada has characterized the ATA as responsive to resolution 1373 (Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada 2001).

It is doubtful that the general language of resolution 1373 called for all the minutiae of the ATA, especially given the absence of a definition of “terrorist act” in the resolution. Nevertheless, the ATA represents an extraordinary law — one motivated and designed at least in part to comply with the specific instructions of the Security Council.

Second, anti-terrorism is complex. The ATA is sweeping, creating a new definition of terrorist activity in Canada’s Criminal Code14 and barring multiple terrorism-related financial activities and assorted (sometimes arcane) inchoate offences. More than this, the law includes significant new government secrecy laws — most notably a revised and partially updated Security of Information Act15 — and makes concordant changes to more than a dozen other federal laws. Meanwhile, the omnibus Public Safety Act16 of 2004 enhances the powers of several ministers to respond to emergencies under a large number of statutes. The Public Safety Act also facilitates the sharing of passenger information between airlines and government and fulfils Canadian obligations under the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention. For its part, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA),17 in force since 2002, contains a number of provisions with respect to national security, including the revamped security certificate process that has attracted sustained public and court scrutiny. When these newest laws are added to existing national security provisions in statutes such the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act,18 the Security Offences Act,19 the Nuclear Safety and Control Act,20 the Emergencies Act21 and the National Defence Act,22 the legal terrain encompassed by anti-terrorism takes on mammoth dimensions, compounding the problem of complexity.

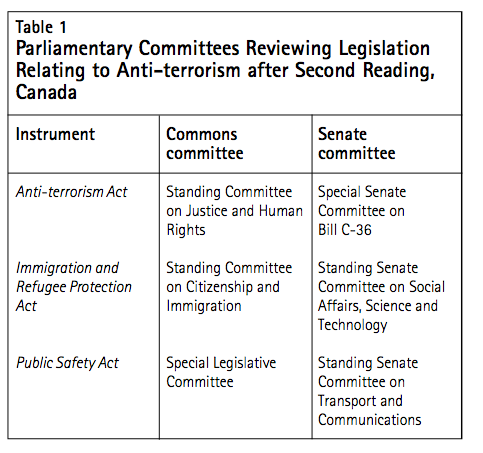

Third, anti-terrorism law responds to uncertain dangers while at the same time straddling conventional divisions in the policy and parliamentary communities with regard to subject matter. The Commons, for example, has a (relatively new) national security committee, but also separate committees dedicated to justice, immigration, and privacy and access to information. As table 1 shows, different committees may be charged with examining different anti-terrorism-related statutes during their respective legislative processes.

At the bureaucratic level, the development of different statutes grappling with specific anti-terrorism issues is centred in different departments. Meanwhile, operating independently of these departments are the auditor general and the privacy and information commissioners — officers of Parliament whose mandate extends to several areas of law affected by anti-terrorism statutes. There is, however, no officer of Parliament whose writ reaches across all national security law or even antiterrorism law. Within the security/intelligence community itself, arm’s-length review responsibilities are “stovepiped” between the Security Intelligence Review Committee (for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service — CSIS) and the commissioner of the Communications Security Establishment (CSE). Currently, no equivalent body exists for the RCMP.

Turning to academia, only a handful of scholars specialize in national security or anti-terrorism law, and only a handful of law schools offer courses on these subjects. Academics tend to have more expertise in criminal, privacy or immigration law.

All these actors are asked to grapple, in a democratic policy-making environment, with a threat that is often inchoate in nature. As Lynch notes, “It is extremely difficult for parliamentarians to know the true extent of the threat to the nation’s security when trying to insist either upon a more consultative, careful process or the inclusion of specific powers and safeguards” (2006, 778).

For all these reasons, anti-terrorism law is an area in which trees may attract scrutiny more readily than the forest — that is, attention is drawn to a handful of particularly controversial areas, leaving the bulk of anti-terrorism measures unexamined.

The process by which the ATA was enacted reflects this challenging policy environment. As we have seen, the ATA is an enormous and complex statute, amending or creating from whole cloth a host of unusual statutory provisions. It would be an exaggeration to suggest that the immediate post-9/11 context, the speed of enactment or the Security

Council impetus for the ATA precluded voluminous debate over the Act and its content. As Roach notes:

Books were written about the Bill and the media produced extensive analyses of its potential effects on civil liberties. Groups representing Aboriginal people, unions, charities, refugees and lawyers, as well as watchdog review agencies such as the privacy and access to information commissioners and the Canadian Human Rights Commission, all voiced their concerns about the Bill, as originally drafted, to committees in the Commons and the Senate. These committees made some important recommendations, many of which were later adopted by the government. (Roach 2007, 4)

Nevertheless, it is also true that the “complex, omnibus nature of the ATA made it difficult for interested persons and parliamentarians to assess all parts of the Act” (Roach 2007, 5). The debate over the ATA focused on the definition of terrorist activity, the Act’s impact on charities and the two unusual law-enforcement powers introduced by the Act: investigative hearings, and the colloquially labelled “preventive detention.” Almost lost in the shuffle were the “implications of the more technical parts of the Act relating to signals intelligence, terrorist financing and government secrecy” (Roach 2007, 5).

In hindsight, the Act overreached, adopting, for example, a definition of terrorist activity that was more sweeping than strictly necessary and that has since attracted negative judicial treatment on constitutional grounds. It also under-legislated, leaving intact, for example, the anti-leakage provision of the renamed Official Secrets Act (a provision ultimately struck down on constitutional grounds). It left for another day a number of issues in public safety law and immigration law ultimately dealt with in the Public Safety Act and the IRPA. None of these instruments, moreover, addressed questions of organization and structure in national security matters. Executive government was ultimately reorganized under the Martin administration with the creation of Public Safety Canada. This was a response to concerns raised in an auditor general’s report examining Canadian anti-terrorism spending from 9/11 through 2003 (Auditor General of Canada 2004, chap. 3). The report noted a lack of coordination and information sharing on public security issues between government departments as they then existed, with various security-related agencies reporting to an array of ministers. However, this Martin-era shuffling of the bureaucratic deck left intact the review mechanisms later questioned by the Arar Commission (in 2006).

In fact, since 2001, certain lacunae and shortcomings of the ATA and related instruments have created a number of uncertainties and controversies in the area of Canadian anti-terrorism law, the most notable of which involve several constitutional rulings. Despite its evident provenance in the horror of 9/11, the ATA is quite emphatically not emergency legislation. It is a regular statute of Parliament, not an extraordinary executive branch regulation issued under the Emergencies Act. Nor does the ATA invoke the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms23 section 33, the notwithstanding clause. It is therefore subject to exactly the same constitutional discipline as any other piece of legislation.24 The most important constitutional rulings in relation to anti-terrorism law at the time of writing include:

Meanwhile, the I R PA security certificate regime has also attracted negative constitutional scrutiny, in the form of a successful Supreme Court challenge to the security certificate procedures (particularly, the reliance by government on secret information never disclosed to the interested party)28 and controversy over the legality of removing an alien when there are grounds for believing he or she will be tortured.29

Other controversies that have emerged since 2001 relating to the ATA or national security procedures and law include the following:

These developments supplement the list of complaints and concerns that animated the original ATA debate, including questions of ethnic profiling, the impact of anti-terrorism law on charities and the legal profession, and an overarching concern about the erosion of civil liberties (as manifested most controversially in the preventive detention and investigative hearing provisions).

While not all of these specific concerns and developments could have been anticipated in 2001, Parliament was alive to the controversies that antiterrorism legislation was likely to provoke. After all, the ATA marked a departure for Canadian criminal law, both in the reach of its substantive offences and in the extraordinary powers it extended to lawenforcement agencies. Moreover, this exceptional legislation would be potentially permanent.

The parliamentary response to the unease caused by the ATA among civil libertarian and Muslim groups in particular came in two forms: a provision requiring a three-year parliamentary review of the Act, and provisions automatically sunsetting the preventive detention and investigative hearing powers after several years unless revived by motions in both houses of Parliament. It is fair to say that neither of these parliamentary review mechanisms operated in the fashion hoped by its proponents.

The ATA specifies that “within three years after this Act receives royal assent, a comprehensive review of the provisions and operation of this Act shall be undertaken” by either joint or separate committees of the Commons or Senate.31 The Act further specifies that the resultant report be tabled in Parliament within a year after the review is conducted. The Act received royal assent on December 18, 2001. The three-year review was begun before a special subcommittee of the Commons national security committee on December 7, 2004, and in a special Senate ad hoc committee on December 15, 2004.

The ATA review was notable for two qualities: its breadth and its duration. In relation to breadth, both parliamentary committees went beyond their strict mandate, incorporating into their deliberations scrutiny of anti-terrorism provisions not part of the ATA itself; both committees, for example, examined the security certificate process housed in the IRPA.

In terms of duration, the review process was greatly prolonged. Under the provisions of the ATA, the findings of the two committees were to be tabled by the end of 2005. In reality, the reports were not completed until February (Senate) and March (Commons) of 2007 (Senate of Canada 2007; House of Commons Subcommittee on the Review of the Antiterrorism Act 2007). The three-year review became almost literally a review that took three years.

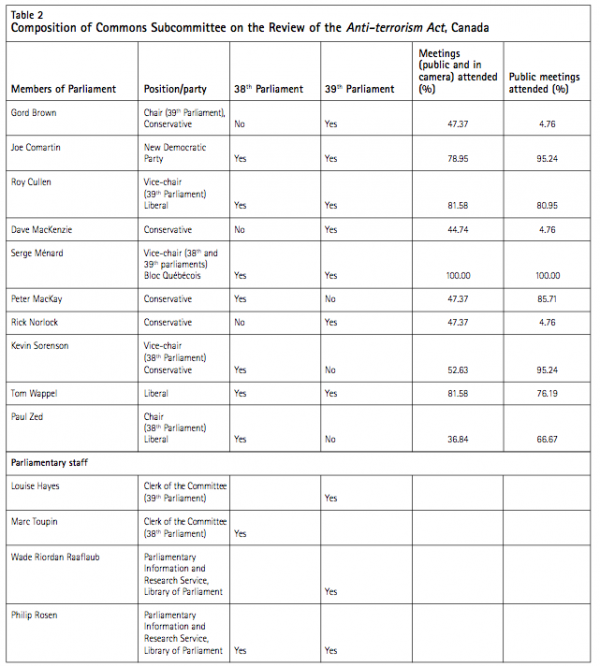

These delays had implications for the continuity of at least the Commons review. Between the review’s commencement and its conclusion, one minority government ended and another took office, producing considerable turnover on the roster of committee members in the Commons. A total of ten MPs sat on the subcommittee during one or both of the two sessions of Parliament over which the review took place (table 2). However, only four of these ten individuals were subcommittee members in both sessions. Four of the seven subcommittee MPs whose names appear on the final report were, therefore, theoretically present for the 38 substantive sittings that included testimony and consideration of the report.32 The public meetings, conducted over 21 sittings, included testimony by 91 witnesses.

The three other members who joined the subcommittee for the 39th Parliament would have been available for the small portion of the public sittings that took place during the 39th Parliament.33 The vast majority of the meetings in the 39th Parliament were in camera and concerned the drafting of the final report and its recommendations. While witnesses during the 38th Parliament included many non-officials, those few who appeared before the subcommittee during the 39th Parliament were all government office-holders. The MPs added to the subcommittee roster during the 39th Parliament would have had access to the transcripts of testimony by (and often written submissions from) earlier witnesses. It is unlikely, however, that they would have had the same level of exposure to — and time to reflect on — the issues at play in the review as did their colleagues who had participated in the full vive voce process.

The net result is that only a bare majority of the MPs who drafted the Commons final report were present to hear from the vast majority of the witnesses who appeared during the review process. Two of the MPs, Joe Comartin (New Democratic Party) and Serge Ménard (Bloc Québécois), dissented from the final report. The majority final report, as a result, was drafted by five MPs, only two of whom were subcommittee members throughout the review process.34

Given this procedural backdrop to the subcommittee proceedings, it is perhaps not surprising that the recommendations formulated in the majority Commons report make a very modest contribution in addressing areas of uncertainty in Canadian antiterrorism law, a point to which I return below.

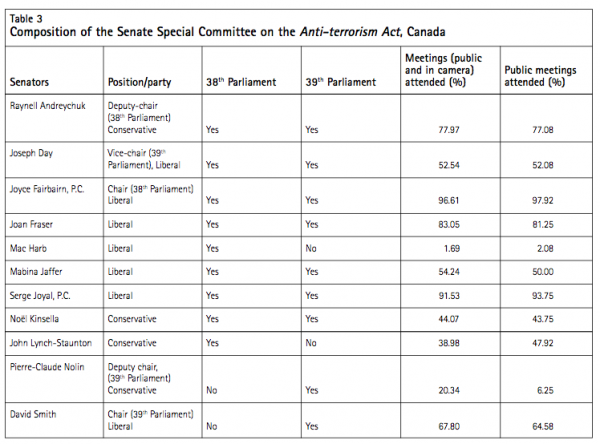

The experience of the special Senate committee was quite different. A majority of senators on the committee had reviewed the ATA when it passed through the legislative process in 2001. They therefore brought considerable expertise to the review process (Roach 2007, 12). Moreover, turnover was less dramatic in the Senate committee than in the Commons subcommittee (table 3). By the time of the report’s release, only two senators who were not members of the committee when it began meeting in the 38th Parliament had been added to the committee. One of these, Senator David Smith, began attending sittings very early in the 38th Parliament and thus was present during most of the public sessions in which evidence was heard.

Therefore the vast majority of members were theoretically available during the 59 sittings during which the Senate committee heard or reviewed evidence.35 The committee heard from some 140 witnesses (several of whom appeared more than once). Not every member was present at every sitting, and attendance rates for the Senate committee were on the whole no better than those for the Commons committee. However, by most measures — membership turnover, number of sittings, hours of deliberation and number of witnesses — the Senate committee outperformed its Commons counterpart. As discussed below, the recommendations included in the Senate committee’s final report also tend to be more comprehensive in assessing the status quo in Canadian anti-terrorism law.

I will not rehearse in detail here the substantive legal issues addressed in the committees’ reports. The purpose is simply to measure the legal significance and policy relevance of the recommendations made by each committee. To this end, I will sort the recommendations into three classes: affirms status quo, proposes minor changes and proposes major changes. A recommendation that affirms the status quo is one that expressly endorses the existing law. One that proposes minor changes supports modifying the existing law but in a manner that does not alter its reach or likely effect, or that does so in ways that are of limited legal significance. A recommendation that proposes major changes supports a modification that would alter the reach or likely effect of the existing law; examples of such changes are new criminal offences or defences and adjustments to existing systems of adjudication, review or oversight that deviate significantly from the status quo.

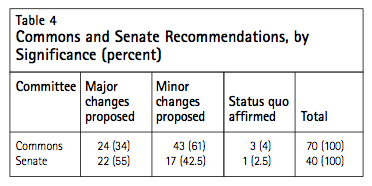

Given these definitions, the partition of recommendations into major and minor is a subjective exercise. However, since the same subjectivity was applied to both the Commons report and the Senate report, this categorization may usefully be employed for comparative purposes. Table 4 shows the results of the comparative analysis.

Caution is advised against making too much of this comparison of recommendations.36 In addition to the qualitative nature of the distinction between major and minor changes, the comparison is influenced by the manner in which recommendations are packaged. For example, one committee might try to effect a major change with a single recommendation while the other committee might try to do so with several recommendations, thereby inflating the number of recommendations labelled major.

Further, this methodology would serve to devalue the significance of a committee report that is content with the status quo, an attitude that vitiates the inclination to make recommendations of any sort.

The data in table 4 do nevertheless permit a comparison, however imperfect, and they also capture the flavour of each report: The Senate report is unquestionably more assertive in proposing significant changes to the functioning of Canadian anti-terrorism law, and is less preoccupied with line editing and redrafting. Specifically, the Senate report grapples with many of the key legal disputes and uncertainties that have arisen in anti-terrorism law since 2001. Moreover, many of its recommendations in these areas are indeed “major.”

The Commons report is silent on several of these matters, and where it is not silent (as with the Canada Evidence Act37) it proposes a series of minor changes. In other areas it canvasses the controversy but fails to recommend a course of action. Particularly notable in this respect is its failure to propose any reaction to a court ruling (which the government chose not to appeal) invalidating the anti-leakage provisions of the Security of Information Act. One might reasonably expect parliamentarians to show an interest in proposing some course of action, thus filling a legal vacuum. To be fair, the Commons report does focus much attention on areas not thoroughly canvassed by the Senate, most notably the security certificate process under the Charities Registration (Security of Information) Act.38 Moreover, it does propose a new criminal offence (albeit the highly dubious crime of glorifying terrorist activity). Nevertheless, the Commons study does much less overall than its Senate counterpart to advance policy discussion on areas of controversy in anti-terrorism law.

Table 5 summarizes 19 key areas of controversy and uncertainty in anti-terrorism law and the extent to which each committee addressed them by making recommendations (as opposed to simply engaging in discussion about them). These issues had been well covered in the media and by the academic, nongovernmental and policy communities, and all were within the purview of the two committees. It is reasonable to expect, therefore, that each would attract scrutiny (and a recommendation of some sort, even one merely defending the status quo).

In July 2007 the government responded to the Commons report (but not the Senate report) (Department of Justice 2007). For many of the Commons recommendations, the government was dismissive or simply noted the recommendation and proposed further study. On the issue of further parliamentary review of anti-terrorism law, the government’s response was particularly ambiguous. Noting that the focus on the ATA is artificial, given the extent to which national security and anti-terrorism legislation is spread across the statute books and the fact that these laws do not fit neatly into any existing subject-matter basket, the government indicated that “reviews should be conducted when they are needed, as opposed to having a pre-set timetable.”39 This statement implies that periodic, repeat reviews are not on the government’s agenda.

The delay in completing the three-year review had implications for the second form of parliamentary reconsideration anticipated in the ATA. Two unusual law-enforcement powers established by the ATA — “preventive detention” and investigative hearings — included sunsetting provisions. In practice these powers would expire in March 2007 unless rescued beforehand by a resolution in both Houses of Parliament. Before turning to the parliamentary debate on sunsetting, I will outline the content of the provisions.40

Formally titled Recognizance with Conditions, the socalled preventive detention provisions clearly were designed to foil terrorist plots on the cusp of execution. Stanley Cohen describes their purpose this way:

The whole scheme is designed to disrupt nascent suspected terrorist activity by bringing a person before a judge who would then evaluate the situation and decide whether it would be useful…to impose conditions on the person. The purpose…is not to effectuate an arrest but merely to provide a means of bringing a person before a court for the purposes of judicial supervision. (Cohen 2005, 218)

With the consent of the federal attorney general, a peace officer could lay an information before a provincial court judge if he or she believed on reasonable grounds that a “terrorist activity” was going to be carried out and suspected on reasonable grounds that the imposition of recognizance with conditions or arrest was needed to prevent that terrorist activity.41 The judge could then order that the person named in the information appear in court.

Under exigent circumstances, where there were grounds for laying an information (or where information had in fact been laid) and a peace officer suspected on reasonable grounds that the person must be detained in order to prevent a terrorist activity, the person could be arrested without warrant. Subsequently, an information would be laid and the person brought before a provincial judge within 24 hours or, if a judge was not readily available, “as soon as possible.”

Whether the person was arrested with or without warrant, when he or she ultimately appeared before the judge, the judge would order his or her release unless the peace officer showed cause for detention, including the likelihood that a terrorist activity would be carried out if the person were to be released.

Alternatively, where the judge declined to order release, the judge could adjourn proceedings for up to 48 hours pending a full hearing on the peace bond issue. The effect of these provisions was theoretically to enable preventive detention on suspicion of terrorist activity for an initial period of up to 24 hours (longer if a judge was not available within that period) and then, if the judge agreed to an adjournment but did not release the detainee, detention for another 48 hours. Preventive arrest could last, in other words, for some 72 hours.

When a full hearing was held, the judge would consider whether the peace officer had reasonable grounds for suspicion. If the officer had reasonable grounds, the judge could order the person to enter into a recognizance of up to 12 months’ duration, a limitation on liberty equivalent to the still existing peace bond power in the Criminal Code.42

Investigative hearings were a tool grafted onto the Criminal Code by the ATA to facilitate the investigation of actual or anticipated terrorism offences. A peace officer investigating a terrorism offence could apply, with consent of the federal attorney general, for an order from a provincial or superior court judge on the “gathering of evidence.” A judge could then compel the presence of the person at a hearing in which the police could question the individual.43 A person named in such an order was obliged to “answer questions put to the person by the Attorney General or the Attorney General’s agent, and shall produce to the presiding judge things that the person was ordered to bring, but may refuse if answering a question or producing a thing would disclose information that is protected by any law relating to non-disclosure of information or to privilege.”44 Fear of self-incrimination was not a ground for refusing to answer a question, but the provision included derivative use protections; that is, no answer made and no thing provided by a person pursuant to the order and no evidence derived from it could be employed in a prosecution against that person, except for perjury.45

In 2004 the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the investigative hearing provisions as constitutional under the Charter. In Application under s. 83.28 of the Criminal Code,46 a majority of the Court rejected arguments that investigative hearings violated judicial independence by enlisting judges in a police investigation. However, the Court interpreted the protections against self-incrimination liberally, extending derivative use immunity beyond criminal proceedings to administrative matters such as immigration and extradition hearings.47

Canadian law generally does not enlist judges to play a supporting role in criminal investigations. Likewise, preventive detention is alien to the Canadian criminal law tradition. For this reason, investigative hearings and preventive detention were controversial features of the ATA.48

Concern about the reach of these provisions prompted Parliament to impose a reporting obligation on the government, requiring annual disclosure of the number of times the power had been used.49 By 2007 neither power had ever been used.50 As noted, Parliament also inserted an automatic sunsetting provision, with the effect of terminating both powers in early 2007 unless overridden by vote in Parliament.51

In the end, a majority on both the Commons committee and the Senate committee recommended, in 2006 and 2007 respectively, that these provisions be extended (House of Commons Subcommittee 2006; Senate of Canada 2007). Because of the delays in finalizing its review, the Commons committee issued its recommendation as an interim report, long before the final review was carried out. However, a motion to renew the provision was defeated by the opposition parties in February 2007, following an acrimonious debate in the House of Commons brimming with political innuendo.

Opponents of renewal on the opposition benches invoked civil liberty concerns in justifying their views. In the case of the Liberals, however, the party was divided between those who now believed the provisions should sunset and those — including several MPs who had been among the chief proponents of these same provisions during Liberal governments — who wished to see the measures left intact. Parliamentarians who opposed the extension were portrayed as soft on terrorism and (in one notorious instance at least) had their personal integrity questioned, usually by government MPs and occasionally by the prime minister himself. In a more policyrelevant objection, expiry of the investigative hearing provision was painted by supporters as a blow to the ongoing Air India criminal inquiry.

Nuance vanished in the debate. Lost in the political fog were recommendations by the Commons committee majority (comprising both Liberals and Conservatives) in its 2006 interim report (House of Commons Subcommittee 2006) proposing changes to a renewed investigative hearing provision that would prevent its use in relation to past (as opposed to anticipated) terrorist offences — including the Air India bombing. Nor did parliamentarians apparently dwell on the fact that even with the expiry of preventive detention, parallel anti-terrorism peace bonds would persist,52 allowing detention (albeit under warrant) pending adjudication of the peace bond issue.53

A number of observations about parliamentary review in the national security area may be extracted from this brief overview of the ATA’s enactment and review process.

The Canadian Parliament is not alone in its vulnerability to these problems. Other Westminster democracies may have useful lessons to offer regarding parliamentary review of anti-terrorism measures. In this second part of the article I consider what guidance might be drawn from the approach to national security policy-making taken by the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. The systems developed in the United Kingdom and Australia, in particular, appear to represent a net improvement over the Canadian approach. This section focuses on two issues: “precursor expert review,” and the approach applied by parliamentary committees in national security matters.

Both the United Kingdom and Australia have developed systems in which arm’s-length experts are asked to review anti-terrorism law. The resultant reviews inform parliamentary assessments and scrutiny. This practice will be referred to below as “precursor expert review.”

Precursor expert review of modern anti-terrorism law in the United Kingdom has come in two forms. First, review has been conducted by a committee of privy councillors appointed by the secretary of state.54 This practice was employed for the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (ATCSA), which required a privy councillor report within two years of passage. The net result was a report by the Newton Committee (the privy councillor committee) submitted to the government and then tabled in Parliament in 2003. The ATCSA review process was linked to repeal provisions: Sections of the Act specified in the report would sunset within six months of the report’s being tabled in Parliament unless debated in both houses.55

In their 2003 report, the seven members of the Newton Committee expressed concern over the breadth of the ATCSA and the pace at which it had been enacted (Privy Councillor Review Committee 2003). The Committee urged the repeal of provisions in part 4 of the ATCSA, namely sections that permitted the indefinite detention of foreign terrorist suspects who could not be deported. It also made a number of other, often very detailed, policy and legal recommendations. However, the Committee went beyond mere suggestions and criticisms and recommended that the Act be allowed to expire, subject to renewal by Parliament. In so doing, it was not signalling disapproval of the entire Act but advocating that the legislation be treated as emergency law and subjected to full parliamentary debate and reconsideration (Privy Councillor Review Committee 2003, 9).

Subsequently the government prepared a discussion paper on the ATCSA, released in February 2004, responding to the Newton Committee report and essentially defending the statute (United Kingdom 2004). The matter was debated in the House of Commons in February56 and in the House of Lords in March.57 As a result, the Act was maintained in force.

Parallel to these review processes mandated by statute, the parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights58 produced a number of reports on the ATCSA and anti-terrorism law generally. On balance, the reports were critical of part 4 of the ATCSA and endorsed recourse to a standard criminal law prosecution model.59 In framing their critiques, the parliamentary reports often relied on the findings of the Newton Committee and of Lord Carlile, the independent examiner of British terrorist laws discussed below. Ultimately, part 4 was repealed and replaced by a system of “control orders” pursuant to the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005 (also discussed below). This change followed a ruling by the law lords of the House of Lords (the country’s highest court of appeal) declaring part 4 incompatible with the United Kingdom’s obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights.60

The second type of precursor expert review in the United Kingdom comes in the form of an independent examiner of terrorism legislation. Prior to its repeal, part 4 of the ATSCA required that the secretary of state appoint an individual to conduct periodic reviews of its anti-terrorism removal and detention provisions. This report was to be then tabled in Parliament.

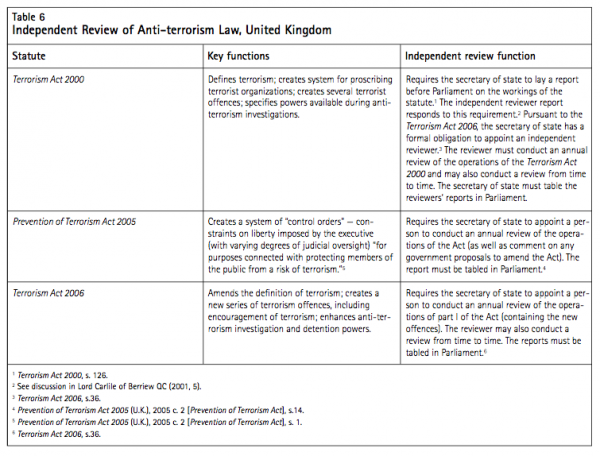

While part 4 no longer exists, equivalent individual examiner functions are found in (or have been applied in relation to) all of the country’s key antiterrorism laws, as summarized in table 6.

Since autumn 2001, the independent examiner has been Lord Carlile of Berriew QC, a Liberal Democrat peer in the House of Lords. By spring 2008, Lord Carlile had prepared nine reports under the Terrorism Act 2000,61 three reports under part 4 of the ATSCA (before its repeal)62 and at least five reports under the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005, including a response to the legislative proposals that ultimately culminated in the Terrorism Act 2006.63 Lord Carlile had also prepared a special report on the definition of terrorism at the request of the Home Secretary (Lord Carlile of Berriew 2007c), in turn responding to a request from the chairman of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Home Affairs. At the time of writing, no annual reports have been issued in relation to the Terrorism Act 2006.

These expert reports have figured prominently in parliamentary deliberations on anti-terrorism legislation. Lord Carlile’s studies are a key source of information for parliamentarians and for witnesses appearing before parliamentary committees.64

Australia has employed a different form of precursor expert review. Pursuant to the Security Legislation Amendment (Terrorism) Act 2002, the attorney general was required to order a review of key anti-terrorism laws enacted by Australia within three years of their adoption.65 The Act specified the composition of the review body, namely “(a) up to two persons appointed by the Attorney-General, one of whom must be a retired judicial officer who shall be the Chair of the Committee; and (b) the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security; and (c) the Privacy Commissioner; and (d) the Human Rights Commissioner; and (e) the Commonwealth Ombudsman; and (f) two persons (who must hold a legal practising certificate in an Australian jurisdiction) appointed by the Attorney-General on the nomination of the Law Council of Australia.”66

The statute charged this review body with receiving public submissions and holding public hearings, then filing a report within six months with both the attorney general and the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (JCIS). The latter was obliged to take account of the report in its own statutory review process (discussed below).

In keeping with these provisions, the expert review body — the Sheller Committee — was established by the attorney general in October 2005. During its public inquiry, the Sheller Committee received 29 submissions and heard evidence from 18 witnesses over five days of hearings in four metropolitan areas. The Committee filed its report with the attorney general and the JCIS in April 2006 (Security Legislation Review Committee 2006). The JCIS considered the report “an important part of the evidence” in its own study. Among the recommendations subsequently made by the JCIS was the creation of a standing independent examiner of anti-terrorism law (analogous to the British system). This independent examiner would respond to the proliferation of increasingly fragmented anti-terrorism law “by providing a consistent and identifiable focal point for the community and the executive agencies” and his or her reports would feed into parliamentary reviews of anti-terrorism law (Security Legislation Review Committee 2006, 20).67

Internal parliamentary review of anti-terrorism law in other Westminster democracies has come in two forms: review by regular parliamentary committee, and review by specially created national security committees.

As we have seen, anti-terrorism law straddles many more conventional areas of law, not least civil and human rights law. Not surprisingly, parliamentary committees with specific subject-matter jurisdiction affected by anti-terrorism law have studied the implications of this legislation for their areas of responsibility. In so doing, they have often acted on their own motion, without formal statutory obligation to do so. This tendency is particularly strong in the United Kingdom. The Commons Constitutional Affairs Committee68 and Home Office Committee69 and the House of Lords and House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights70 have all conducted studies on anti-terrorism issues, in addition to issuing reports as part of the process of enacting relevant bills.

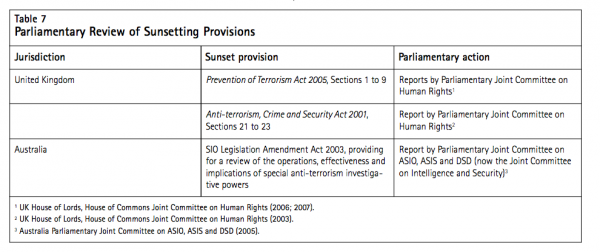

In other circumstances, general committees have conducted studies in response to sunset provisions in antiterrorism laws. The United Kingdom has a long-standing practice of including sunsetting sections in its antiterrorism laws.71 These provisions limit the lifespan of the legislation, unless it is renewed by Parliament. Sunsetting in modern British anti-terrorism statutes is more uneven, with sunsetting provisions existing in some but not all statutes.72 The ATCSA, for example, did include sunset provisions. Sections in part 4 of the Act, permitting the indefinite detention of foreign terrorist suspects who could not be deported, were to sunset in 2006 and could expire before that time if not renewed annually by the secretary of state by statutory instrument, a draft of which had been laid before and approved by resolution of each House of Parliament.73 As we have seen, these provisions have since been replaced by the control order system under the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005. That instrument, too, includes sunsetting rules: The control order regime will expire after renewable periods of 12 months unless the government tables a regulation renewing the system in Parliament and the regulation is approved by resolution in each House.74 These sunsetting provisions have all sparked reviews by regularly constituted parliamentary committees, as shown in table 7.

Anti-terrorism laws in Australia, like those in the United Kingdom, include sunset rules tied to certain, specific state counter-terrorism powers.75 However, in Australia, unlike in the United Kingdom, committee deliberation on these provisions usually takes place within the JCIS, a highly specialized, statutorily created national security committee mentioned above and described more fully below.

In still other cases, general committees have been tasked by statute with conducting periodic reviews with no link to sunset provisions. Specific provisions in British law, for example, require that reports be laid in front of Parliament, sparking committee review.76 For its part, the New Zealand terrorist law required review by a regular select committee of the country’s House of Representatives. Completed in 2005, the review was conducted by the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee (New Zealand House of Representatives 2005). The resultant report was the most perfunctory of the parliamentary reports studied for this article. The committee’s deliberations were interrupted — and obviously impaired — by an election.77

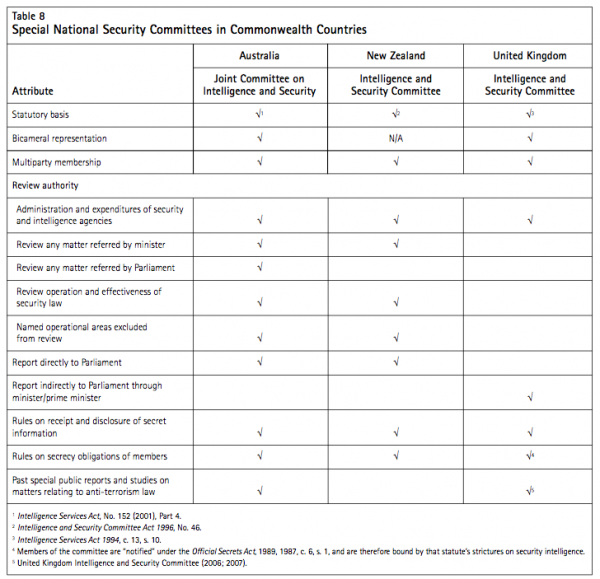

In the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, general committee review of anti-terrorism law is supplemented with review of security and intelligence matters by special, statutorily created and mandated statutory committees comprising parliamentarians. The composition and powers of these committees are summarized in table 8. The committees issue annual reports and, at least in the case of the United Kingdom, occasionally publish reports on antiterrorism and other matters.

Because these bodies have statutorily-prescribed powers and responsibilities, they differ from a regular parliamentary committee. The former reports to Parliament through the prime minister while the latter is a subset of Parliament itself, whose powers and immunities flow from parliamentary privilege. The Martin government proposed an analogous statutorily created national security committee of parliamentarians for Canada in 2005. That Bill died on the order paper.

Australia has deployed the statutorily created JCIS in a key policy-shaping role. Often, this is the parliamentary committee charged with reviewing sunsetting provisions or undertaking statutorily required periodic review of anti-terrorism laws. For example, pursuant to the Intelligence Services Act 2001, the JCIS was required to review the operation, effectiveness and implications of key anti-terrorism legislation78 as soon as possible after the third anniversary of its enactment. Thus it was charged with taking into account the expert Sheller Report, discussed above. In addition to the Sheller Report, the JCIS received 29 submissions and heard evidence from 13 witnesses in a session extending over approximately a day and a half in summer 2006. Its report was tabled in December 2006 (Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security 2006).

Other periodic reviews have focused on the terrorist organization listing provisions in Australia’s Criminal Code,79 as well as assessments of individual listing decisions.80 The JCIS has also conducted parliamentary inquiries in response to extraordinary anti-terrorism powers slated for sunsetting in Australian law.81

In the United Kingdom in particular, the reports generated by precursor expert review and then parliamentary committees usually draw a formal response from the government.82 There is therefore a rich corpus of material explaining and justifying government policies. The British government has also adopted the practice of circulating regular and often quite detailed discussion papers to float anti-terrorism law proposals before tabling legislation.83 Discussion papers and government responses appear to be less common in Australia, but they do exist (e.g., Attorney-General of Australia 2007).

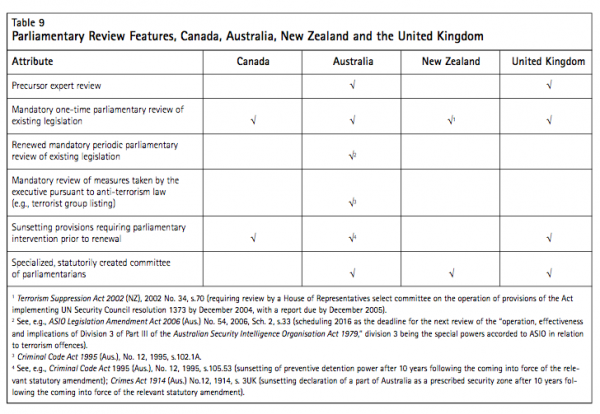

Table 9 provides an overview of anti-terrorism law with respect to the features of parliamentary review in the four Westminster democracies covered in this article. As this table and the above discussion suggest, the key features that distinguish the United Kingdom and Australia from Canada are, first, precursor expert review and specialized, statutorily created committees of parliamentarians with national security law review functions. In the United Kingdom, annual precursor expert review by an independent reviewer, coupled with short, renewable sunset periods for some antiterrorism provisions, means that there is a steady supply of assessments and studies of anti-terrorism provisions, now numbering in the dozens. In Australia, one-time precursor expert review fed into deliberations by a specially empowered and specialized committee of parliamentarians, tasked in turn with making its own report. Australia may now be moving towards a system of more regular precursor expert review.

In fairness, Canada has employed its own form of precursor expert review — public inquiries such as those into the Arar matter and the Air India bombing. These processes have, however, run in parallel to executive and parliamentary policy deliberations, and at times have resembled adversarial judicial proceedings more than broad-ranging policy inquiries. They have also been ad hoc, rather than periodic, and relatively narrowly focused by virtue of specific terms of reference. These inquiries are therefore not analogous, in function or form, to the independent reviews conducted by Lord Carlile in the United Kingdom.

In sum, the British and Australian assessment procedures appear attractive when contrasted with the rather dismal experience of the recent Canadian ATA review. Precursor export review, when coupled with subsequent consideration by an adequately resourced and stable parliamentary committee, might help to overcome some of the difficulties encountered in the ATA review process, especially at the Commons level. In keeping with the recent Australian JCIS observations, a regular precursor expert review could serve to resolve problems of complexity and scope in anti-terrorism law. With a wide-ranging mandate, an independent evaluator would be able to identify lacunae and difficulties that might escape the attention of parliamentary committees and to place them on the official agenda. The independent evaluator would therefore function in a manner analogous to existing officers of Parliament, able to bring matters lying within their subject-matter jurisdiction to the appropriate parliamentary committees.

Repeated annual or special reports by an independent reviewer also militate against the gradual normalization of anti-terrorism laws and powers — that is, the prospect that these laws will fade from public consciousness and lurk unquestioned in Canada’s statute books. Anti-terrorism provisions are too radical to be left unscrutinized. Independent reporting may also serve to galvanize more regular (and transparent) policy thinking within executive government, as it appears to have done in the United Kingdom. British government responses to independent review have produced a corpus of documents and discussion papers, many of which are much more informative than the cagey government reaction to Canada’s ATA review process.

By publicly benchmarking key issues in antiterrorism law, precursor expert review may also reduce the impact of turnover on parliamentary committees; whatever a committee’s membership, it will be difficult to ignore observations made in the precursor expert review. In addition, it may be worth contemplating the Australian model, and the primacy accorded its JCIS in the review process. Whether a statutorily created parliamentary committee is more stable and expert than a regular parliamentary committee depends on design. It should be possible, however, to create a body whose membership is less fluid than that of the Commons committee in the recent ATA.

Precursor expert review might also take some of the high politics out of parliamentary deliberations on anti-terrorism issues. A credible, independent evaluator will be difficult to ignore, or to paint in a partisan light. One wonders how the carefully considered views of such an evaluator might have affected the disappointing and superficial parliamentary debates on preventive detention and investigative hearings in February 2007.

Precursor review could prove to be especially valuable in periods of crisis or their aftermath, or in periods of intense partisanship (such as minority governments). It would prepare Parliament for responding to crises and could also serve to eliminate partisanship from parliamentary debate on complex issues such as human rights protection. A stable system of precursor review, coupled with executive response and parliamentary examination, might generate broad expertise in the area of national security law. Ideas would be tested and debated in public, laying the ground for rapid but carefully vetted responses to possible future crises. Policy actors (well versed in legal and policy matters through the precursor review process) might focus not only on clearly controversial issues that arise in legislated responses to crisis, but also on the more detailed and complex matters that, if the enactment of the original ATA is any indication, may otherwise escape scrutiny. Put another way, precursor expert review could address a number of the challenges that arise in the antiterrorism policy environment.

Finally, precursor expert review followed by study by a parliamentary committee would combine expert consideration with more democratically legitimate investigation. Such a combination could serve to overcome the weaknesses of, respectively, legitimacy and expertise under which each would labour if one is done without the other.

All this is not to suggest that the product of precursor expert reviews would necessarily be endorsed first by parliamentary committees and then by governments — indeed, Australia’s Sheller Report was rejected by the Howard government (Nicholson 2006). Further, this discussion may exaggerate the extent to which precedents drawn from the United Kingdom and Australia would cure some of the ills plaguing the recent ATA review. On the other hand, it is difficult to see a negative side to a credibly constructed precursor expert review system. Policy deliberations in the area of anti-terrorism law can only benefit from more information and assessment.

Attorney-General of Australia. 2007. “Material That Advocates Terrorist Acts: Discussion Paper.” Canberra: Attorney-General’s Department. Available online: https://www.ag.gov.au/nas/content/live/irpp/agd/agd.nsf/AllDocs/10AE 457C710B1085CA2572CE0028849F?OpenDocument.

Auditor General of Canada. 2004. “Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the House of Commons.” March. Accessed April 23, 2008.. https://209.71.218.213/inter- net/English/aud_parl_oag_200403_e_1123.html

Australia. Parliamentary Joint Committee on ASIO, ASIS and DSD. 2005. “ASIO’s Questioning and Detention Powers: Review of the Operation, Effectiveness and Implications Of Division 3 of Part III in the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979.” Accessed May 28, 2008. https://www.aph.gov.au/house/ committee/pjcaad/asio_ques_detention/report/ fullreport.pdf

Bland, Douglas L., and Roy Rempel. 2004. “A Vigilant Parliament: Building Competence for Effective Parliamentary Oversight of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces.” Policy Matters 5 (1).

Bronitt, Simon, and James Stellios. 2006. “Sedition, Security and Human Rights: ‘Unbalanced’ Law Reform in the ‘War on Terror’.” Melbourne University Law Review 30 (3), 923.

Cohen, Stanley. 2005. Privacy, Crime and Terror. Markham, Ontario: LexisNexis Butterworths.

Commission of Inquiry into the Actions of Canadian Officials in Relation to Maher Arar. 2006. A New Review Mechanism for the RCMP’s National Security Activities. Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services Canada.

Communications Security Establishment Commissioner. 2007. Annual Report 2006-2007. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada.

Department of Justice. 2007. “Government’s Response to the Seventh Report of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security — Rights, Limits, Security: A Comprehensive Review of the Anti-Terrorism Act and Related Issues.” Accessed April 28, 2008. https://cmte.parl.gc.ca/Content/ HOC/committee/391/secu/govresponse/rp3066235/ 391_SECU_Rpt07_GR/391_SECU_Rpt07_GR-e.pdf

Forcese, Craig. 2007. National Security Law: Canadian Practice in International Perspective. Toronto: Irwin Law.

Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. 2001. “Report of the Government of Canada to the Counter- Terrorism Committee of the United Nations Security Council on Measures Taken to Implement Resolution 1373.” Ottawa: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. Available online: https://www.dfait-maeci. gc.ca/trade/resolution_1373_dec14-en.asp.

House of Commons Subcommittee on the Review of the Anti-terrorism Act. 2006. “Review of the Anti- Terrorism Act Investigative Hearings and Recognizance with Conditions.” Ottawa: House of Commons. Available online: https://cmte.parl.gc.ca/cmte/CommitteePublication.aspx?COM=10804&Lang=1&SourceId=193467.

House of Commons Subcommittee on the Review of the Anti-terrorism Act. 2007. “Rights, Limits, Security: A Comprehensive Review of the Anti-terrorism Act and Related Issues.” Ottawa: House of Commons. Available online: https://cmte.parl.gc.ca/cmte/Committee Publication.aspx?COM=10804&Lang=1&SourceId=199086.

Lee, Derek. 1999. The Power of Parliamentary Houses to Send for Persons, Papers and Records. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Lord Carlile of Berriew QC. 2001. “Report on the Operation in 2001 of the Terrorism Act 2000.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available online: https://security.homeoffice. gov.uk/news-publications/publication-search/terrorism- act-2000/operation-ta-2000/tact-report.pdf? view=Binary.

_____. 2002a. “Report on the Operation in 2002 of Part VII of the Terrorism Act 2000.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/ news-publications/publication-search/terrorism-act- 2000/terrorism-act-2002.pdf?view=Standard& pubID=482240

_____. 2002b. “Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 Part IV Section 28 Review 2002.” United Kingdom: Home Office.

_____. 2003a. “Report on the Operation in 2003 of Part VII of the Terrorism Act 2000.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/news- publications/publication-search/terrorism-act-2000/tatc- report-2003.pdf?view=Standard&pubID=482242

_____. 2003b. “Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act, Part 4 Section 28, Review 2003.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/ news-publications/publication-search/anti-terrorism- crime-securityact/atcsa-review-part7.pdf?version=1

_____. 2004a. “Report on the Operation of the Terrorism Act in 2002 and 2003.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/news- publications/publication-search/terrorism-act-2000/ter- rorismact-rpt.pdf?view=Standard&pubID=482234

_____. 2004b. “Report on the Operation in 2004 of the Terrorism Act 2000.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/news- publications/publication-search/terrorism-act-2000/ter- rorism-act-report.pdf?view=Standard&pubID=482238

_____. 2004c. “Report on the Operation in 2004 of Part VII of the Terrorism Act 2000.” United Kingdom: Home Office.Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/ news-publications/publication-search/terrorism-act- 2000/terrorism-act.pdf?view=Standard&pubID=482236

_____. 2005a. “Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 Part IV Section 28 Review 2004.” United Kingdom: Home Office.available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov. uk/news-publications/publication-search/anti- terrorism-crime-securityact/part-iv-feb-05.pdf?version=1

_____. 2005b. “Report on the Proposals for Changing the Laws against Terrorism” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/news- publications/publication-search/prevention-terrorism-act-2005/carlile-review-121005?view=Standard&pubID=480264

_____. 2006a. “Report on the Operation in 2005 of the Terrorism Act 2000.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/news- publications/publication-search/terrorism-act-2000/ tact-2005-review?view=Standard&pubID=480250

_____. 2006b. “Report on the Operation in 2005 of part VII of the Terrorism Act 2000.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice. gov.uk/news-publications/publication-search/terrorism- act-2000/part-7-report?view=Standard&pub ID=480262

_____. 2006c. “First Independent Review of the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/ news-publications/publication-search/prevention- terrorism-act-2005/laws-against-terror.pdf

_____. 2006d. “Review of the Home Secretary’s Quarterly Reports to Parliament on Control Orders.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security. homeoffice.gov.uk/news-publications/publication- search/control-order-statements/pta-review2-06.pdf

_____. 2007a. “Report on the Operation in 2006 of the Terrorism Act 2000.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/news- publications/publication-search/terrorism-act-2000/ TA2000-review06.pdf?view=Standard&pubID=480246

_____. 2007b. “Second Independent Review of the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice. gov.uk/news- publications/publication-search/prevention- terrorism-act-2005/Lord-Carlile-pta-report-2006.pdf

_____. 2007c. “Report on the Definition of Terrorism.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/news-publications/ publication-search/terrorism-act-2000/carlile- terrorism-definition.pdf.

_____. 2008. “Third Independent Review of the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005.” United Kingdom: Home Office. Available at: https://security.homeoffice.gov.uk/news- publications/publication-search/general/report-con- trol-orders-2008?view=Binary

Lynch, Andrew. 2006. “Legislating with Urgency.” Melbourne University Law Review , 30 (3), 747. Available online: https://search.austlii.edu.au/au/ journals/MULR/2006/24.html.

Maingot, Joseph. 1997. Parliamentary Privilege in Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

New Zealand House of Representatives, Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee. 2005. “Review of the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002.” Available online: https://www.parliament.nz/NR/rdonlyres/55E46F9D- 3598-492A-89DF-88FFB78F8886/15214/DBSCH_ SCR_3274_2303.pdf.

Nicholson, Brendan. 2006. “Rights ‘Breached’ by Anti-terror Laws, But Government to Ignore Findings of Review Committee.” The Age (Melbourne), June 16. Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Terrorism Legislation.” Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/ house/committee/pjcis/securityleg/report/report.pdf.

Privy Councillor Review Committee. 2003. “Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 Review: Report.” London: The Stationery Office Available online: https://www.statewatch.org/news/2003/dec/atcsReport.pdf.

Roach, Kent. 2007. “Better Late Than Never? The Canadian Review of the Anti-terrorism Act.” IRPP Choices 13 (5). Montreal: IRPP.

Security Legislation Review Committee. 2006. “Report on the Security Legislation Review Committee.” Canberra: Attorney-General’s Department. Available online: https://www.ag.gov.au/nas/content/live/irpp/agd/rwpattach.nsf/VAP/ (03995EABC73F94816C2AF4AA2645824B)~SLRC+Rep ort-+Version+for+15+June+2006[1].pdf/$file/ SLRC+Report-+Version+for+15+June+2006[1].pdf.

Senate of Canada. 2007. “Fundamental Justice in Extraordinary Times: Main Report of the Special Senate Committee on the Anti-terrorism Act.” Ottawa: Senate of Canada. Available online: www.parl.gc.ca/39/1/parlbus/ commbus/senate/Com-e/anti-e/rep-e/rep02feb07-e.htm.

Stewart, Hamish. 2005. “Investigative Hearings into Terrorist Offences: A Challenge to the Rule of Law.” Criminal Law Quarterly 50 (4) 376-402.

United Kingdom. Intelligence and Security Committee. 2006. “Report into the London Terrorist Attacks on 7 July 2005” (May 2006). Available at https://www.cabinet office.gov.uk/intelligence/ special_reports.aspx.

_____. Intelligence and Security Committee. 2007. “Rendition” Available at https://www.cabinet office. gov.uk/intelligence/special_reports.aspx.

_____. Home Office. 2004. “Counter-terrorism Powers: Reconciling Security and Liberty in an Open Society (February). London: Stationery Office. Available at https://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/documents/ cons-count-terror-powers-310804?version=1

_____. House of Lords, House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights. 2003. “Continuance in Force of Sections 21 to 23 of the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001.” Fifth Report of Session 2002-03. Available at https://www.publications.parliament. uk/pa/jt200203/jtselect/jtrights/59/59.pdf

_____. House of Lords, House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights. 2006. “Counter-Terrorism Policy and Human Rights: Draft Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005 (Continuance in Force of Sections 1 to 9) Order 2006.” Twelfth Report of Session 2005-06. Available at https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt200506/jts- elect/jtrights/122/122.pdf

_____. House of Lords, House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights. 2007. “Counter-terrorism Policy and Human Rights: Draft Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005 (Continuance in force of sections 1 to 9) Order 2007.” Eighth Report of Session 2006-07.” Available at https://www.publications.parliament.uk/ pa/jt200607/jtselect/jtrights/60/60.pdf

Craig Forcese is an associate professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of Ottawa, where he teaches public international law, national secu- rity law, administrative law and public law and legislation; he also runs the annual foreign policy practicum. Much of his present research and writ- ing relates to international law, national security and democratic accountability. He is the author of National Security Law: Canadian Practice in International Perspective (2007). Prior to joining the University of Ottawa law faculty, Mr. Forcese practised with Hughes Hubbard and Reed LLP, a Washington, DC, firm specializing in international trade law. He has law degrees from the University of Ottawa and Yale University, a BA from McGill University, and an MA in international affairs from the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, Carleton University. Mr. Forcese is a member of the Bars of Ontario, New York and the District of Columbia.

This publication was produced under the direction of Mel Cappe, President, IRPP, and Wesley Wark, Fellow, IRPP. The manuscript was copy-edited by Jane Broderick, proofreading was by Wendy Thomas, production was by Chantal Létourneau, art direction was by Schumacher Design and printing was by AGL Graphiques.

Copyright belongs to IRPP. To order or request permission to reprint, contact:

IRPP

1470 Peel Street, Suite 200

Montreal, Quebec H3A 1T1

Telephone: 514-985-2461

Fax: 514-985-2559

E-mail: irpp@nullirpp.org

irpp.org

All IRPP Choices and IRPP Policy Matters are available for download at www.irpp.org

To cite this document:

Forcese, Craig. 2008. “Fixing the Deficiencies in Parliamentary Review of Anti-terrorism Law: Lessons from the United Kingdom and Australia.” IRPP Choices 14 (4).