Five Canadian provinces are in the process of changing the way they elect their legislatures. And, given the NDP’s determination to bring the question to Parliament, it is highly unlikely that the Liberal government, given its minority situation, will be able to sweep the issue under the rug. In this paper, Henry Milner analyzes the progress and prospects of these developments. As he shows, two provinces are leading the way: Quebec and British Columbia. If, as expect- ed, the British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly proposes a new voting system, it will be taken to the people of the province in a referendum on May 17, 2005. In their proposal, expected in December 2004, the 160 Assembly members may be influ- enced by a Bill to be tabled by the Quebec government in the coming weeks.

Quebec has already set out the principles for its proposed voting sys- tem. It is based on a German proportional representation (PR) model that combines lists with single – member constituencies. Known as mixed-mem- ber proportional representation (MMP), it was recently adopted in New Zealand, Scotland and Wales because, unlike other forms of PR, it allows peo- ple to retain their constituency representative – something, the author notes, Canadians would also expect.

Under MMP, the voter casts two votes – a party vote for the list of a party, and a district vote for a constituency representative. Constituency winners are decided by plurality – just as in our first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system – and then the party vote determines the total number of seats to which each party is entitled. The number of constituency seats a party has won is subtracted from that total in order to establish the number of MPs drawn from its lists. The MMP system is far more proportional than FPTP, and, as Henry Milner explains, the extent to which the outcome under MMP diverges from perfect proportion- ality is affected by three variables: the percentage of overall seats available for purposes of compensation from the party lists, the size of the territory covered by the lists, and any minimum vote requirements used to discourage the prolif- eration of small parties.

Professor Milner reviews the experiences in Scotland and New Zealand, both comparable in size, and in their Westminster traditions, to Canadian provinces. He finds that, on the whole, the adoption of MMP has proven suc- cessful. There are two caveats, however. First, “party hopping” by list MPs should be discouraged – but not by making the rules unnecessarily rigid, as is the case in New Zealand. Second, provinces considering MMP would do well to adopt measures taken in Scotland to avoid possible friction between list and con- stituency MPs.

After looking at those international experiences, Professor Milner sum- marizes the evolution of the electoral reform process in British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and New Brunswick. In the last part of his paper, he critically examines the proposed Quebec variant of the “Scottish model” and argues that this proposal will make it harder both for small parties and for women to win fair representation. He concludes by proposing modifications that would rectify this situation and bring Quebec’s system into line more with the Scottish model.

Among mature democracies, only the United States and Canada use the first- past-the-post (FPTP) system for electing state and provincial, as well as national, lawmakers. The FPTP emerged as part of what is known as the Westminster sys- tem of political institutions, developed in Britain and passed on to its colonies. Only Canada, however, has remained fully faithful to the FPTP system. But not for much longer, it would appear.

The debate over Canada’s electoral system, which began in earnest after the 1997 federal election, has moved from the university and think-tank seminar rooms to the floors of several provincial legislatures. In a forthcoming book edited by the author (Milner 2004), observers present up-to-date accounts of developments in British Columbia, Quebec, Prince Edward Island and Ontario. They show these four provinces moving at different speeds toward the goal expressed in the mandate given to a commission set up at the end of 2003 in New Brunswick: to propose a “specific model of proportional representation” that, among other things, “ensures…a continued role for directly elected MLAs representing specific geographic boundaries.”

Only one system of proportional representation (PR) ensures such a role: mixed-member proportional representation (MMP). A term coined in New Zealand, MMP is a system of representation based on principles developed in postwar Germany. It was the MMP model’s ability to ensure that continuing role that caused the system to be selected over other PR modalities in the 1992 New Zealand referendum and, a few years later, for the new assemblies in Scotland and Wales. Given their size, composition and, especially, their Westminster insti- tutions and traditions, these are the most relevant examples for Canadian provinces to draw upon.

Historically, Canadian federalism has fostered policy and institutional innovation at the provincial level. And we expect this to apply to electoral sys- tem reform as well, much as electoral system innovation in the United Kingdom paralleled the process of devolution. Yet recent events in federal politics suggest that developments in Canada could conceivably follow along the lines of New Zealand, where an unusual combination of political events and electoral out- comes triggered nationwide institutional changes no one had anticipated. In Canada, until early this year, it was universally assumed that Paul Martin’s Liberals would coast to a majority victory in the upcoming federal Canadian elec- tion. However, weakened by the revelations of the auditor-general, the best the Liberals could do was a minority government dependent on NDP support – support that its leader, Jack Layton, had stated would be contingent on organizing a commission and referendum on changing Canada’s electoral system. In the new minority context, the report of the Law Commission of Canada (2004), which in March recommended that the House of Commons adopt a system of elections most closely resembling the form of MMP used to elect the Welsh Assembly, takes on added significance.

In this article, I first briefly set out the main arguments for electoral system reform, basing them on recent election outcomes and focusing on the provinces considering change. I pay special attention to the relationship between electoral systems and voter turnout, a matter of acute concern in Canada given the dismal numbers in recent years. I turn next to recent developments in Scotland and New Zealand, communities with Westminster-style parliaments comparable to those of the Canadian provinces used to single-member electoral systems but now electing their members of Parliament through the MMP model. Has implemen- tation of the system lived up to the expectations of the MMP’s proponents and critics? And what lessons can those Canadian provinces considering electoral sys- tem reform draw from these experiences?

This section is followed by a brief description of the situation in each of the four provinces and a more detailed focus on Quebec, where the first concrete proposal for replacing FPTP will soon be tabled by the Charest Liberal govern- ment in the National Assembly. After setting out this proposal – it can be described as a variant of the “Scottish model” – and the plans for implementing it, I consider its advantages and disadvantages. I conclude that it is an advance over the FPTP, but one that includes elements that run counter to the overall logic of the MMP system. I then propose specific changes that would bring it more in line with that logic. Such a system, I conclude, once custom tailored, would be the best fit for the legislatures of the provinces as well as the Parliament of Canada.

Because of the uncertainly over its outcome, the 2004 federal election was quite different from the three that preceded it. Yet turnout was still lower than in 1993, 1997 and 2000, when it was clear who would form the government in an elec- tion and, for the great majority, who would win in their districts. To take the case of the 2000 election, one assessment found that only 48 of 301 ridings were too close to call (Leuprecht and McCreery 2000, 286). Undoubtedly, this finding is related to the fact that just under 70 percent of eligible voters under age 30 is estimated to have stayed home on election day in 2000 (Pammett and Leduc 2003, table 14). Part of the explanation for the fact that a more competitive fed- eral election in 2004 did not stem the decline in turnout lies in the fact that some young voters have developed habits of abstention and inattention to politics that will carry through later life.1

Canadian citizens in noncompetitive districts are in a situation analogous to that of most Americans when choosing their congressman or congresswoman. The overwhelming majority of our neighbours to the south live in gerrymandered, sin- gle-member districts that have reduced legislative competition to historically low levels. In the three national elections for the US House of Representatives since 1996, more than 98 percent of incumbents were returned to office. In some 20 per- cent of districts, the other party did not bother to put up even token opposition.2

Although Canadian institutions are very different,3 we do elect the members of our lower house in exactly the same way. In Canada, as in the US, votes only count if they can result in someone being elected in a district. In the 1993, 1997 and 2000 federal elections, 59.2, 61.6 and 59 percent of electors voted for parties other than the Liberals, but in each case, because of the party’s lead over each of the other four parties, a Liberal government was a foregone conclusion well before election day.

Moreover, our political experience strongly suggests that even if we were to attain the level of competitiveness needed for a non-Liberal federal govern- ment, it would likely be short-lived and – unless the electoral system were changed – we would return to the one dominant party system of the 1990s. The uniting of the Alliance and Progressive Conservative (PC) parties took place, fortuitously, at the same time as the outbreak of the sponsorship scandal, creat- ing a situation where a growing desire to “throw the bums out” coincided with the arrival of a more or less viable instrument for doing so. Yet even that failed to produce a non-Liberal government.

Canada skipped the mid-twentieth-century process in which welfare state consolidation in the Westminster countries produced a two-party system with lib- eral/conservatives on one side and social democrats on the other. Instead, unlike Britain, Australia and New Zealand, success came to the Canadian parties that best played regional brokerage politics: usually the Liberals, but occasionally the Tories. Moreover, once the level of redistribution reached a point of being more or less fixed, somewhere during the 1970s and 1980s, the emergence of a class-based two-party system was rendered even more difficult. In normal circumstances, therefore, the logic of the system favours the hegemony of the party that best expresses whatever national consensus exists. In Canada, given its composition, resources and experience, this is undeniably the Liberal Party. The other parties, associated as they are with differing regional aspirations and operating in a first- past-the-post electoral system that exaggerates parties’ regional strengths and weaknesses, cannot hope to permanently replace the Liberals as the “Canada party.” Even if Paul Martin’s heroic efforts to simultaneously kick the bums out and keep the Liberals in power had failed, they would likely usher in only a brief inter- regnum, as certain to be shattered by regional contradictions as was the last such interregnum – Brian Mulroney’s arranged marriage of the West and Quebec.

Any improvement in turnout fostered by greater competitiveness – and uncertain proposition as shown by the failure of the competitiveness of the 2004 election to boost turnout, – is likely to be short-lived unless the intereg- num is seized upon to produce electoral system reform. Here the role of the New Democratic Party (NDP) may yet prove crucial. For much of its history, that party took it for granted that, like the Labour Party in Britain, it was des- tined to replace one of the two “business” parties and take over the “levers of power” in Ottawa. Even the party’s most successful recent leader, Ed Broadbent, failed to persuade his colleagues to look instead to the continental model in which PR assured social democratic parties a stable representative base from which to build their support.

Fortunately, the NDP appears finally to have learned its lesson, if we are to judge by the fact that the party seems to be firmly behind the position of its current leader, Jack Layton: to make support of a minority government con- tingent on action to change the electoral system. While the NDP is closer to the Liberals on most domestic and foreign policy issues, the latter, given their long- term electoral prospects, are likely to be less open to such a deal than would a minority Conservative government led by Steven Harper. The question now is thus whether the NDP can and will assemble the opposition behind electoral system reform in the face of a minority Liberal government’s foot dragging. A major factor will be the evolution of informed public opinion. Will a compet- itive federal election resulting in a minority government be interpreted as pre- cluding the need for such a reform? Or will the actual experience of a minori- ty government serve to dispel the fears of instability raised by opponents of electoral reform?4 Looking back over developments in recent generations, dem- ocratic governments seem to have functioned reasonably well when no party had a majority (see Lijphart 1999). This is because, in minority or coalition government situations, the large parties must work harder to assure support for their policies – which hardly induces them to favour PR. Supporters of reform both inside and outside the NDP will nonetheless be able to point to past expe- rience, which suggests that Canada could do worse than be governed by a (usually Liberal) minority government.5

Moreover, proponents of electoral system reform will not be without resources. With its very practical and detailed proposal for an alternative electoral system, the report of the Law Commission, which was greeted perfunctorily by Justice Minister Irwin Cotler as he passed it to the Commons Committee on Procedures and House Affairs, could yet serve to stimulate the first genuine discus- sion of electoral system reform in Parliament (Law Commission of Canada 2004).6

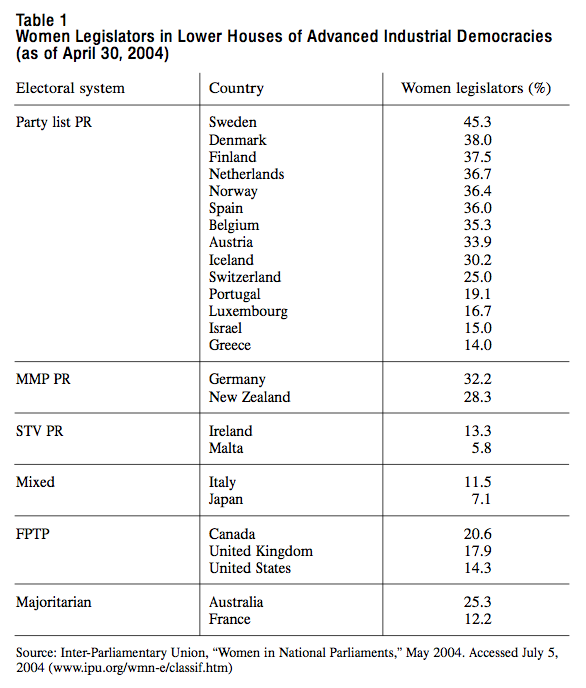

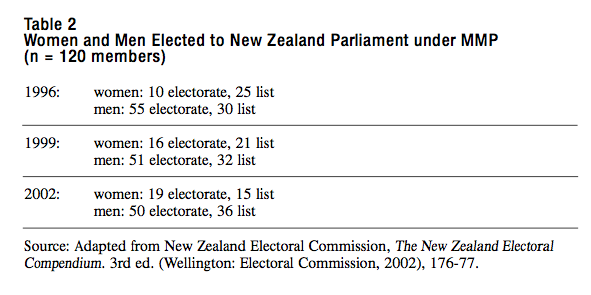

Electoral system reformers have an important weapon in their arsenal: PR’s relationship to the representation of women (table 1). At 21 percent, the pro- portion of women MPs in Canada7 is lower than that in most comparable countries with proportional systems (though still higher than most FPTP leg- islatures). The reason for this is well known: for parties that have some desire to improve the representation of women, PR systems, unlike FPTP systems, are conducive to putting that objective into practice. This is because all PR systems – with the partial exception of the single transferable vote (STV) used in Ireland and Malta – use party lists.8 Where there are lists, parties can act to ensure that women are positioned to be elected. Indeed, not to do so in the face of public pressure would make the party vulnerable, unlike in the FPTP system, where the nomination decision under normal circumstances lies with local party members. As shown in table 1, women do better in most of the European countries where PR systems are used. In New Zealand, in the three elections using the MMP model, women’s representation averaged 29.4, compared to 17.4 in the three previous elections under the FPTP system (Nagle 2004, table 5.2). The improvement, as seen in table 2, is due to the list element in the MMP system. To understand why this should be so, a brief explanation of how the MMP model functions is in order at this point.

In the MMP system, the voter casts two votes: a party vote for the list of a party, and a district vote for a constituency representative. After constituency winners are decided by plurality (just as in the FPTP system), the party vote determines the total number of seats to which each party is entitled. Then the number of constituency seats won by the party is subtracted from the overall total to which the party is entitled, thereby establishing the number of members of Parliament (MPs) drawn from its lists. Thus a party’s parliamentary represen- tation is made up of both district MPs and list MPs, the total of which makes up a proportion of MPs that reflect the party’s level of popular support. While the MMP system is far more proportional than the FPTP system, the extent to which the outcome under the MMP model diverges from perfect proportionality is affected by three factors: the percentage of overall seats available for purposes of compensation from the party lists, the size of the territory covered by the lists, and any minimum vote requirements used to discourage the proliferation of small parties. The effect of lists on women’s representation can be seen in the different gender distributions of list-elected and district-elected New Zealand MPs under the MMP model in table 2. The same logic, it should be added, applies to visible minorities.9

In New Zealand, as in Germany, the Green Party uses the “zipper system,” in which male and female candidates alternate on its list – a practice common in Scandinavia where all candidates are elected from lists. These are decisions made by the parties themselves. In New Zealand’s parliamentary revision of the MMP model in 2001, for example, all its parties rejected a feminist proposal to place a legal obligation on the parties to impose quotas to achieve gender equi- ty. France, however, has chosen to do just that. Yet legal impositions only work where there are lists, as Bird demonstrates in her study of France, where gender parity has been realized only in local elections (Bird 2004).

Although the possible effects on turnout and women’s representation have been part of the discussions on voting system reform taking place in the five provinces, these were not the issues that initially provoked the discussions. The spur was rather the party representation distortions in the legislatures witnessed in recent electoral outcomes and which, together, manifest the pathologies to which the FPTP system can give rise. We have already seen three pathologies manifested at the federal level in recent years – namely, one-party dominance (by the Liberals), the destruction of a party (the Progressive Conservatives), and the hyper-regionalization of politics10 – making the term “Ontario MP” effectively synonymous with “Liberal MP.” To these we must add three more phenomena – an enfeebled opposition, the loser wins, and hyperpolarization – all of which have been especially char- acteristic of the provinces in which action to change the electoral system is being initiated.

The policies of Mike Harris were reminiscent of those of New Zealand’s National (conservative) Party between 1990 and 1993. Let us look, then, at New Zealand, perhaps the most British of the former British colonies and the least likely, one would have said, to abandon the venerable FPTP system. When given the choice, New Zealanders found MMP the most appropriate representation system, not necessarily because it is intrinsically better than other PR systems – pure list sys- tems work well in many European countries that have never experienced single member districts – but because they preferred a system that allowed them to maintain representation by a single MP. As noted earlier, Canadian voters, if they were willing to consider a proportional electoral system, would likely choose MMP over one-vote list-based PR systems because, like voters in New Zealand and Britain, they would insist on continuing to have a single MP represent them. And they would not be mistaken, according to Faure and Venter’s analysis of the effects of imposing pure-list electoral systems under the new South African Constitution of 1996. These two leading South African political scientists describe a situation in which MPs are effectively cut off from the constituents they represent – a situation, they argue, that would be alleviated by the MMP model (Faure and Venter 2004).

The majority of New Zealanders came to understand that electoral insti- tutions need to be changed if they wish to avoid the narrow, ideology-driven agendas imposed by a governing party with a majority of seats but a minority of votes; they had already experienced that situation in the latter 1980s under the neo-liberal policies of the Labour party. A New Zealand Royal Commission proposed, and the people in the 1992 and 1993 referenda ratified, an MMP system. In the initial referendum, citizens were asked, first, whether FPTP should be kept and, second, if it were changed, which of four alternatives they preferred. In the wake of the apparent failure of 10 years of radical economic- restructuring policies, 84.7 percent rejected the FPTP model. Electoral reform- ers had successfully argued that the “elective dictatorship” resulting from FPTP was part of the problem. In the choice of reform options, the MMP model won 70.5 percent (Aimer 1999). Next, in the binding referendum that coincided with the 1993 election, the options were narrowed to two, and the MMP sys- tem triumphed 54 to 46 over the status quo (with an 83 percent turnout). This occurred despite a pro-FPTP campaign supported by business and the two main parties, which overspent FPTP’s opponents by 8 to 1 or more – money largely spent on a campaign that warned of the dire consequences of govern- ment instability under the PR scheme (Nagel 2004, 127-8).

Indeed, as does any form of proportional representation, the MMP system effectively makes single-party majority government a thing of the past.11 But how well has it fared? Clearly, the MMP model did not – and indeed could not – live up to the exaggerated expectations of its proponents (Nagel 1999); but it also did not live up to the fears of its opponents. For example, although turnout did rise as predicted in the first MMP election in 1996, it turned out to be a “spike”: the decline begun in the 1980s resumed in 1999.12 Electoral reform proved not to be a shelter against the wider forces driving down turnout in the democratic world.

The 2001 conclusions of the parliamentary select committee, required under the law setting up the MMP to review its performance, bear witness to the evolution of opinion in New Zealand. The failure of the committee to propose any major changes in the MMP, or to hold a new referendum on whether to keep the MMP, reflected not only the presence of the smaller parties, which owed their parliamentary existence to MMP, but also the change of heart of the ruling Labour Party’s leadership that, once anti-MMP, now realized their party could actually thrive under the proportional system (Nagel 2004, 130).

In two important articles, Nagel portrays how New Zealanders, severely disappointed by the first MMP-produced coalition (Nagel 1999), became some- what more comfortable with the subsequent ones. In his recent, careful exami- nation of the record of the MMP model in practice, Nagel concludes, “Overall…MMP impresses this observer as a dramatic improvement over the FPTP system it replaced. As one would expect from a list PR method, it has pro- duced equitable translation of votes into seats for political parties, plus much bet- ter representation of women and minority groups. It has also delivered virtues commonly, but mistakenly, attributed to FPTP-majority rule, moderation, and even (after a false start) accountability. Beneath the froth of volatile minor parties and precarious coalitions, MMP has fostered stabler policies, incremental reform and economic progress” (Nagel 2004, 140-1).

From New Zealand, the MMP system travelled to Britain, most importantly to the new Scottish Parliament, as well as to the Welch Assembly and the Greater London Council.13 Unlike the latter two, which have limited powers, Scotland’s status as a real regional government operating within wider Westminster institutions makes it especially interesting for Canadian provinces looking at electoral system reform.

Although no referenda specifically on the electoral system occurred during the process of devolution, the modalities of election to the newly devolved Scottish Parliament were very much a part of the overall transformation, the details of which were worked out at a months-long constitutional convention. After considering different proposals, the convention opted in 1992 for an MMP system (in the United Kingdom the term is AMS [additional member system]) that uses a dual ballot and a closed list of regional candidates. To resolve detailed issues, especially disagreement regarding parliament size and the balance between constituency and list members, a constitutional commission was estab- lished in 1993. The final compromise established a 129-member parliament, consisting of 73 FPTP members and 56 (43 percent) list members of the Scottish Parliament (MPs: 7 for each of the 8 electoral regions) elected proportionally. Unlike in New Zealand, where the idiosyncratic decision of a third party, New Zealand First, resulted in a centre-right rather than the expected centre-left coali- tion government in the first MMP election, the first MMP Scottish Parliament produced the expected “Liblab” (Labour-Liberal Democrat) coalition. In the recent (2003) Scottish election, the big winners were the smaller parties: with a combined 22.6 percent of the regional list vote, they won 17 seats in all (Jeffery 2004). In that election, despite losing 7 constituencies, Labour still dominated the constituency battleground with 46 of 73 district seats; because of that dom- inance, however, Labour was entitled to only a handful of “top-ups” at the regional level, thereby exacerbating the “two types of MPs” tension inherent in the MMP model (see below).

In his survey of the new Scottish Parliament under the MMP system, Lynch concludes that the main fears about how MMP would work were misplaced. Voters do not seem to perceive any of the shortcomings critics have associated with proportional representation systems, such as government instability or excessive power being given to small parties. Even in the most recent period, with the Liblab majority cut to just 5, a fragmented opposition ensures a contin- ued, stable government. In addition, there is little evidence that voters have found the two-ballot system unduly difficult (Lynch 2004, 156-7).

As noted, the working out of the system in Scotland did produce one problem: a certain level of conflict and tension between the two different types of Scottish Parliament members. This problem stemmed largely from the Labour Party’s strength, which assured it of most of the FPTP seats and, thus, very few com- pensatory ones from the lists; this, in turn, left few FPTP seats for the other par- ties, which generally depended on election from the list seats (Lynch 2004, 155). This brought to the surface a problem often cited by critics of the MMP system, but which, in reality, seldom manifests itself; namely, the different responsibili- ties of list and district MPs.14 The exception appears in a country or province where one party is clearly dominant “on the ground” (i.e., in the districts). If Alberta adopted MMP, for example – hardly a likely eventuality – we could anticipate a situation comparable to that of Labour in Scotland and Wales,15 except that it would be the Conservative caucus that would be made up largely of constituency MLAs, with the opposition members being elected almost entire- ly from the lists. Nevertheless, party support patterns in the other provinces and the regional voting pattern for Canada’s Parliament mean that Alberta would be the exception; that is, in most elections the party caucuses would have a fair number of representatives of both types of members. That said, provinces would do well to examine, in advance, the measures taken in Scotland to balance the responsibilities of the district and list MPs (Lynch 2004).

Another unanticipated problem – “party hopping” by list MPs – emerged in New Zealand early in the implementation of the MMP system. Many people were outraged by the visible shopping around for another party label by some MPs elected on the idiosyncratic New Zealand First (NZF) party’s list dur- ing the first MMP Parliament. Unfortunately, the cure proved worse than the dis- ease. That is, the Electoral Integrity Act introduced in the second MMP Parliament to outlaw the practice was so draconian in its sanctions of transgressors – it was designed to secure the support of the volatile NZF leader Winston Peters – that it proved perverse in its effects. This manifested itself in 2001, when the law blocked a split in the left-wing Alliance Party; New Zealanders were then treated to the sad spectacle of two hopelessly estranged factions compelled to continue cohabiting in the shell of their former party home to avoid facing the sanctions resulting from leaving an existing party. Legislators are now working to enact a more flexible formula when the Act expires in 2005, one that will prevent oppor- tunistic party hopping but will also allow for party dealignment based on funda- mental matters of principle. This is a formula the Canadian provinces planning to implement the MMP model could well take on board.

On balance, the overall record of the MPP model in the two jurisdictions most applicable to Canada and its provinces has proved reasonably good. Given the strong regional identities in Canada, the Scottish-Welsh system of regional lists should make that version of the MMP system especially attractive. For its part, the New Zealand experience should prove to be an important referent for methods of deciding upon and instituting electoral system reform. But it is the way the referenda debate took place in New Zealand rather than the use of the referenda per se that should prove especially helpful to provinces engaged in the reform process. Observers were highly impressed with the effectiveness of the cit- izen education campaigns that accompanied the process. Indeed, one reason that money did not determine the outcome – as it typically does in California refer- enda – was that an objective presentation of the relevant facts levelled the play- ing field. Conducted under the direction of an ad hoc, independent Electoral Referendum Panel chaired by the chief ombudsman, the panel teamed the com- munication skills of an advertising agency with the expertise of academic spe- cialists to produce “lucidly informative and sometimes entertaining TV and radio spots, videos, booklets and pamphlets. While scrupulously neutral, to the point of not even mentioning the Royal Commission’s endorsement of the MMP model, the panel’s work helped produce an impressive level of public awareness and understanding” (Nagel 2004, 129-30).

By comparing the workings of the MMP model in the UK and New Zealand, as well as Germany, we can begin to formulate guidelines for apply- ing the system to Canada. How best, for instance, can we take advantage of MMP’s unique preserving of single-district representatives in a list-based PR system? It is clear that if and when those considering electoral system reform in each of the relevant provinces choose the MMP system as the principle for allocating seats, they will need to address several specific aspects, taking into account local conditions and expectations. The first aspect is the percentage of overall seats available for purposes of compensation. The Law Commission of Canada has endorsed the Welsh Assembly’s split of one-third list, two- thirds district. In Germany, the formula is 50-50; in New Zealand and Scotland, list seats run between 42 and 43 percent. Other things being equal, it is clear that the greater the proportion of list seats, the more easily full pro- portionality can be attained.

The next aspect, not unrelated to the first in its effect, involves the territory from which the lists are drawn. With the same proportion of list seats, New Zealand’s outcomes are more proportional than Scotland’s; that is because the territory covered by the party lists is much larger (the entire country) than that covered in Scotland, where each list includes a regional district of approxi- mately one-eighth of the population. Hence, in Scotland, an effective regional vote threshold emerges that somewhat reduces overall proportionality. On the other hand, using regional lists means that Scotland need not employ, as must New Zealand and Germany (where the lists are statewide), an overall legal threshold to discourage the proliferation of small parties. In New Zealand, unless a party wins a district seat (in Germany it is three district seats), it must receive at least 5 percent of the list votes to qualify for any list seats. Canadians will and should insist on a real or effective threshold to limit the number of parties able to win seats. Similarly, the electoral law could and should specify, as it does in Germany, that placement on the list is determined by party members (or their elected delegates) and not by party officials.

Because its list is national, New Zealand has not had to add temporary list seats, something Germany has done to restore proportionality in “overhang” sit- uations. Such scenarios occur in the smaller regional districts on those rare occa- sions when a party is able to win more than twice as many district seats as its proportion of the regional party vote entitles it to, thus requiring an additional (usually only one) list seat in that region to bring the total to full proportionali- ty. It is difficult to imagine Canadians – any more than Scots – accepting a practice that makes regional representation disproportionate in order to make party representation fully proportional. Without such a provision, using region- al lists for, say, 40 percent of total seats, as Quebec is moving toward doing, mean the sacrifice of a small measure of proportionality. To me, however, this seems legitimate in the Canadian context, as it does in the Scottish. Unlike in New Zealand where, despite its location on two separate islands, regional identities are weak, in the larger Canadian provinces – and, of course, in Canada as a whole – strong regional identities make the Law Commission’s endorsement of the Scottish-Welsh region-based system appropriate.

Another matter raised by the Law Commission is the opening of the list ballot, a variation not used in any MMP country. Open ballots are used in certain list systems, such as that of Belgium, to give the voter greater input into candi- date choice in those countries using pure list PR systems; the consensus in the MMP countries is that the first ballot gives individuals sufficient choice to justi- fy not adding in the complexity of open lists. Nevertheless, perhaps some merit exists in considering – as the Law Commission suggests – the Swedish system, in which a locally popular candidate low on the party’s regional list is moved to the top if he or she receives the “personal vote” of more than 8 percent of the party’s supporters. These aspects, and other more technical ones such as the actu- al mathematical formula for allocating seats (Scotland uses the “D’Hondt divisor method”),16 can be tailored to local circumstances.

Let us begin with New Brunswick, the last province to act. In December 2003, New Brunswick Premier Bernard Lord appointed a nine-member Commission on Legislative Democracy, chaired by Mount Allison political scientist William Cross, to make recommendations on proportional representation and other dem- ocratic reforms; thus he lived up to the Conservative Party’s electoral promise to examine proportional representation. The commission’s mandate is to make rec- ommendations on strengthening and modernizing the electoral system and dem- ocratic institutions and practices; the goal is to make them more fair, open, accountable and accessible to New Brunswickers. Regarding electoral reform, the commission’s terms of reference are to propose a specific model of PR, including the number of constituencies to be represented in the Legislative Assembly, which would ensure fairer representation, greater equality of votes, an effective legislature and government, and a continued role for directly elected MLAs rep- resenting specific geographic boundaries. To fulfill its mandate, the Commission on Legislative Democracy is seeking the views of New Brunswickers through public hearings and submissions and is conducting research. Its report is due December 31, 2004. As noted at the outset, the terms of reference effectively invite the commission to endorse the MMP model.

The victory of Dalton McGuinty’s Liberal Party in the October 2003 Ontario election made real electoral system reform possible. A Liberal policy document had promised a “full, open public debate on voting reform,” holding out the possibility of a referendum pitting the status quo against “some form of proportional representation, preferential ballots or mixed system” (Pilon 2004). Electoral reform was even more strongly endorsed by the provincial New Democratic Party, which was not the case when it governed Ontario in the early 1990s, and by the Green Party. The process moved forward when the new pre- mier announced the formation of a Democratic Renewal Secretariat, reporting to Attorney General Michael Bryant and headed by Queen’s political scientist Matthew Mendelsohn, with a mandate that extends to investigating fixed elec- tion dates, campaign finance reforms, an increased role for backbenchers, and internet voting. Its main task, however, is “spearheading a public consultation and referendum on Ontario’s voting system” (Pilon 2004, 249).

Somewhat as occurred in British Columbia (discussed below), the Ontario Liberals proposed using “citizen juries,” chosen at random, to research, deliberate and present their findings in this area, among others. The juries’ mandate is to give the public a clear choice between two distinct options in a referendum, should jury members find change to be justified. Regarding voting system reform, then, if a citizen jury recommends change, it is required to present a single alternative to FPTP for a public referendum, as happens in BC. But, unlike in BC, the Cabinet can review the citizen juries’ decisions before they are presented in a referendum. It remains to be seen if the Ontario Democratic Renewal Secretariat will be able to move the process forward rapidly enough for the Ontario Liberals to live up to their promise to institute changes in time for the next provincial election.

Although progress in the third province, Prince Edward Island, started quite early, it has since slowed. The lopsided election results led to a number of public discussions and inquiries, culminating in the appointment of a one-man commission. In December 2003, the PEI Commission on Electoral Reform – in the person of Commissioner Norman Carruthers, the retired chief justice of the province – proposed that FPTP be replaced by a system incorporating an ele- ment of proportional representation, preferably something akin to the MMP model. Rather than bringing his proposal to the government for action, the commissioner stated that any reform must be preceded by a public information campaign, a “citizen’s assembly” and a referendum. He nevertheless made the outcome he expected clear, since PEI could obviously benefit from voting-system reform (Cousins 2004).

The commissioner’s conclusion that the reform process ought to be carried fur- ther raised the real possibility of an unprecedented change to the PEI electoral sys- tem. An MMP-based legislative assembly, the report notes, would represent a radical shake-up of political life in the province. If nothing else, it would ensure the presence of a respectable number of opposition MLAs. It might also increase the number of women in the assembly and enhance the position of third parties. Early in his report, the commissioner compares the debate over electoral reform to the campaign to win the secret ballot in the nineteenth century – something initially regarded as a “crazy old question” and a hopeless cause, but which voters now take for granted.

The PEI government reacted cautiously to the Carruthers Report, stressing the need for public discussion and debate before any consideration of specific recom- mendations for an alternative electoral system. While Premier Binns noted the absence of a “driving need amongst average Islanders today to change the electoral system,” he did give some weight to the Report’s assertion of that there was indeed room for improvement to ensure that the elected members better reflect the will of the voter than FPTP was producing (Cousins 2004). On May 21, 2004, The CBC reported that (with the support of opposition leader Gary Robichaud), Premier Binns planned to appoint a commission to draft a new electoral model for the province, teach Islanders about the new model, and draft a referendum question on whether to switch to proportional representation. The commission would also propose a date for the referendum, which he anticipated would take place as early as fall 2005.

The clearest path, though, is being carved out by British Columbia. It is a path likely to be followed at least in part by Ontario, but perhaps also by PEI and New Brunswick. It involves a method for undertaking institutional reform in areas beyond voting systems. Though not without raising misgivings, the pro- posed innovations – among the most original and ambitious in deliberative democracy17 ever undertaken in Canada and elsewhere – turn the process over to a “citizen’s assembly” of ordinary citizens, who decide what, if anything, to bring before a binding referendum.

The BC Citizens’ Assembly is mandated to “assess models for electing Members of the Legislative Assembly and issue a report recommending whether the current model for these elections should be retained or another model should be adopted.”18 That assessment must “take into account the potential effect of its recommended model on the system of government in British Columbia,” and any new system recommended must be “consistent with both the Constitution of Canada and the Westminster parliamentary system.” If the assembly does rec- ommend against retention of the FPTP model, it must present an alternative, which will then be presented to the citizens in a referendum (Ruff 2004).

After his defeat in 1996 (despite winning more votes than his oppo- nents), BC Liberal leader Gordon Campbell promised that, if elected, he would bring electoral system reform before citizen review. After sweeping to power in 2001, his government mandated former Liberal leader Gordon Gibson to explore the means of doing so. Gibson’s proposals for a citizens’ assembly were, after some delay, amended and then endorsed by the BC legislature, which named Jack Blaney, former president of Simon Fraser University, as the assem- bly’s chair. The composition of this assembly reflected the commitment to keep the process of electoral system reform out of the hands of politicians, with their inevitable vested interests: anyone directly involved in party politics was excluded. An invitation “to consider doing something very special for British Columbia” was then sent to a random sample of 200 eligible voters from each constituency (prepared by Elections BC), stratified by gender and age. From those who accepted, 10 men and 10 women per riding, selected at random, were invited to attend regional information meetings; among those who chose to continue, one man and one woman were selected by lot for each district. The last (158th) selection was made on December 8, 2003; two First Nations members were added from among those who had made it through to the final random pool (none had emerged “from the hat”).

With members receiving reimbursement for their expenses and child care assistance, as well as an honorarium of $150 per sitting day, the Citizens’ Assembly began its learning phase over six alternate weekends in Vancouver. A hearing phase followed, involving 49 hearings in regional centres throughout the province in May and June. In preparation, the assembly released an eight- page “Preliminary Statement to the People of British Columbia,” setting out arguments for and against reform and inviting input from citizens. After a summer break, the final deliberation phase will continue through the fall, with several weeks to prepare recommendations to be delivered to the attorney gen- eral by December 15, 2004. Assuming the report calls for change, the legisla- ture and Cabinet are required to set in motion a mechanism for a public debate on the issue leading to a referendum to take place on the date of the next elec- tion, May 17, 2005.

The Assembly’s final report is likely to propose a real change, judging by observers’ reports of the assembly members’ enthusiasm for their work. Indeed, it is hard to imagine so much effort culminating in an endorsement of the status quo. Reports suggest, moreover, that assembly members want what- ever emerges from their long-combined efforts to be implemented; that entails submitting a proposal likely to be endorsed by the 60 percent of voters com- prising a majority in 60 percent of the districts, as required by the referendum law. These requirements preclude aspects likely to provoke additional opposi- tion, such as increasing the number of members of the legislature or quotas for women candidates.

Assuming a form of PR is proposed, there is real uncertainty over the form it will take. In principle, the odds should favour the selection of a form of the MMP model, since only the MMP allows retention of single-member districts. Nevertheless, one cannot ignore the strong case for the STV mount- ed by BC’s most prominent proponent of electoral reform, Nick Loenen. In his 2003 brief to the Citizens’ Assembly, Loenen proposed a hybrid “Preferential-Plus” system that envisages the preferential vote for nine rural, single-member districts, allowing them to preserve links with a single repre- sentative, combined with 14 STV multimember districts consisting of 3 to 7 seats. As well, BC citizens associate the MMP alternative with the Green Party, which, early on, embraced it so intensely that some assembly members may shy away from it as somehow partisan. In my view, this would be unfortu- nate since STV can play into a populist distrust of partisan politics, a distrust apparent in BC – the only province that allows for the recall of deputies. In such circumstances, the STV model encourages candidates to, in effect, run against their own party. A candidate-based system, we should also note, is less conducive to augmenting women’s representation (as the numbers for Ireland and Malta in table 1 illustrate). Given these considerations, Ruff’s prediction that “a made-for-BC” adaptation of some of the regional features of the German and Scottish models, “including perhaps a preferential open- party list vote may…muster Citizens’ Assembly and voter support” (Ruff 2004, 241)19 may yet prove accurate.

The first to enter the legislative arena will be Quebec.20 Although western provinces, including BC, experimented with different electoral systems in the mid-twentieth century, in recent years Quebec has been the most interested and involved in the process of change. No less a figure than René Lévesque was committed to bringing in the PR model, although his effort during his second term of office (1981 to 1985) ultimately aborted. Lévesque asked the Commission de la représentation électorale, chaired by Quebec’s chief electoral officer Pierre-F. Côté, to conduct public hearings and report to the National Assembly. In March 1984, Côté recommended the province adopt a “territori- al proportional” system that resembled one proposed by the government the previous year. Yet despite leading a majority government, Lévesque could not win sufficient support to overcome the opposition of the Liberals who, given the Parti Québécois (PQ)’s drop in the polls, were able to portray the effort as an opportunistic attempt by an unpopular government to save its skin. Without sufficient support in his own caucus, Lévesque was forced to with- draw the proposal. Electoral-system reform was not to reappear on the Quebec political agenda for another fourteen years.

The November 1998 election saw the PQ win a parliamentary majority – 76 seats – with only 42.9 percent of the vote; the PLQ, on the other hand, with 43.5 percent, won only 48 seats, while the Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ) won only one seat with 11.8 percent of the vote. Both opposition parties called for electoral reform, though the PQ was less than enthused. In October 2001, a new group, le Mouvement pour une démocratie nouvelle (MDN) pre- sented a petition signed by 125 prominent citizens – among them former PQ cabinet minister Claude Charron, former Liberal leader Claude Ryan and Jean Allaire, co-founder of the ADQ – calling on the government to hold public hear- ings immediately. By chance, the sudden departure from politics of two ministers led Premier Bernard Landry to elevate National Assembly Speaker Jean-Pierre Charbonneau to the Cabinet in January 2002, giving him responsibility for the reform of democratic institutions. Charbonneau then engaged André Larocque, a key architect of Lévesque’s proposal, as his deputy minister.

In June, in response to the MDN petition, the chairs of the National Assembly Committee on Institutions announced that the committee would hold public hearings on electoral reform in 10 cities, beginning in October 2002.21 Soon afterwards, Charbonneau announced plans for an “Estates General” on democratic reform to be held in early 2003. According to a discussion paper entitled “Citizen Empowerment: A Paper to Open Public Debate,”22 system reform was only one of a wide range of reforms to be examined. At the Estates General held in Québec City in February 2003, over 900 delegates, seated in workshops of 10 to a table, took up each of the items in turn. On the last day they voted for the proposals of their choice. Over 90 percent favoured a reform of the electoral system: 66 percent called for adding elements of pro- portionality to the existing system, while 24 percent preferred a pure PR system.

The Béland Committee released its report on March 10, 2003, two days before Premier Landry called a general election. On the main question of vot- ing-system reform – and despite limited support at the Estates General for this model – the Béland Committee endorsed the territorial-list system proposed by the Côté Commission in 1984. Responding to requests sent by the MDN during the election campaign, the large majority of Liberal Party candidates, including the leader Jean Charest, stated that they were ready to act on elec- toral reform. True to his word, the new premier named Jacques Dupuis minis- ter for the reform of democratic institutions, giving him a mandate to change the voting system.

In September 2003, before an Institute for Research on Public Policy con- ference on democratic reform, Dupuis reiterated his party’s commitment to introducing a law to establish a mixed compensatory (MMP) system for electing the 125 MNAs. The most likely breakdown is 75 from individual ridings and the remainder at-large regional representatives. These numbers, which have become a kind of accepted wisdom, correspond to Quebec’s 75 federal ridings and a ratio of regional representatives approaching that used in New Zealand and Scotland.23 Yet the minister took many observers by surprise when he said that the statuto- ry requirements of the Elections Act made it unlikely that the new voting system could be implemented before the next election.

The minister also took some observers by surprise when he stated that a single-vote version of the MMP model was an option. During detailed briefings with various specialists (including the author of this paper) and interested par- ties, he set out his preferred system in which voters cast only one vote (i.e., for a candidate), so that the total vote received by a party’s candidates in an electoral region could be used to determine the number of overall seats to which the party is entitled. This differs from the method used in the UK, New Zealand and Germany, where party support is measured via a separate second vote (although in German state elections, 2 of 16 states, namely North Rhine-Westphalia and Baden-Wurtemberg, use a single vote). Using a single vote reduces the electors’ range of options, by making it impossible to vote for the “best” candidate irre- spective of party preferences.

When combined with the second wrinkle, the proposal as envisaged by the minister – with its absence of party lists – begins to deviate from the overall principles that make MMP a system of proportional representation. The minister’s project envisages the compensatory, or top-up, seats being assigned to the “best losers”; i.e., candidates for parties entitled to such a seat who came out on top in a losing cause in a district contest in the electoral region. For example, in an electoral region with six district seats and four top-up seats, the total votes of the party’s six candidates would be added up and that number used to calculate the party’s percentage of the overall vote. If, say, that total was 30 percent, entitling the party to three of the ten seats, and if that party had won (by its candidate placing first) one of the six district seats, it would then be entitled to two compensatory seats. In the absence of lists, these seats would be allocated to the party’s two (of five) district candidates who had the highest percentage in a losing cause.

The MDN has been working to mobilize its members with an eye to changing the government’s position on these two aspects of the proposal, as well as on the replacement of regional districts by a New Zealand-style single- national-list system. This latter idea, which flies in the face of the strong regional identities so clearly expressed at the Estates General, reflects the posi- tion of the powerful feminist lobby within the organization. In my view, this is a strategic error. Alienating the regions will only weaken the organization’s abil- ity to mobilize support in order to change the other aspects of the reform (especially the absence of lists) that most impede its capacity to increase the representation of women and minorities.

Let us look at the two aspects in more depth. The argument for two votes and, especially, lists is linked to the overall goal of adopting a propor- tional electoral system. Proportionality is not merely a mathematical concept: it is an application of the principle of fairness. And a fair electoral outcome reflects the real – not just the strategic – choice of voters. The two aspects are not the same because there are two distorting characteristics under the FPTP system. The first is purely mathematical: votes cast are not fairly reflect- ed in party representation. But, as Paul Martin’s plea to NDP supporters in the 2004 election illustrates, voters under FPTP are incited not to waste their votes but to vote for the candidate of a party that can win the district, espe- cially in a close election, even if that party is not one’s favourite, if the effect of voting in this way would be to block the candidate of a less acceptable party from being elected.

A system with a single vote and no lists makes it harder for small par- ties (through their candidates) to attract a number of votes equivalent to the party’s actual support; under-representation is thus assured. If there were but a single vote and the allocation of compensatory seats was done on the basis of lists, the disadvantage would be reduced. But this would depend not only on the visibility of the lists but on the public’s understanding of the workings of a complex system that transfers their candidate vote to a party vote for allocation of the list seats. A two-vote system makes the allocation much more transparent.

If one seeks more equal representation, the absence of lists is of even greater concern. Only the German state Baden-Wurtemberg does not use lists, and this is something the victorious coalition in the 2001 election promised to correct (see Massicotte 2003). I have already noted how the list systems of PR and the list element of the MPP model are the factors most conducive to a fair representation of women and visible minorities. It is the use of lists that gives the proportional element its public face. Simply by comparing party lists with the names (and often pictures) of the candidates, the voter can gain a sense of the overall representativeness of the party’s message.

Minister Dupuis justified his preference for a single vote and no lists as the most concordant with the electoral habits of Quebec voters and, therefore, the most acceptable reform. Such a system, he insisted, would be easy to sell: the voters would feel they were operating in a known system, but with fairer out- comes. The other side of the coin, however, is that genuine reform should allow voters to act differently, not simply vote in exactly the same way but with differ- ent outcomes. Clearly, it takes the presence of a second vote and a party list (as well as the kind of campaign that took place in New Zealand) to provide voters – not just a sophisticated minority – with the information needed to take full advantage of reform possibilities.

The minister also referred to the danger the use of lists has posed in Italy, with its partial and idiosyncratic version of the MMP system, noting instances of parties dominant in regions gaining top-up seats by running phantom lists.24 Can we imagine something similar in Quebec? I suspect not: there is no indica- tion of this practice emerging in Germany, New Zealand, or Scotland and Wales, despite, in the latter two cases, the Labour Party’s incentive to secure list seats in this very way.

Here in Quebec, the MDN insists on closed lists, which allow parties to place women and minorities high on the list (and allow interest groups to pres- sure them to do so), thereby practising a kind of affirmative action. In the con- text of region-based lists, closed lists serve to balance the personal element in the district seats. This seems to me to be justified, although it may be neces- sary, should there be public distrust of regional party nominating bodies, to fol- low the Law Commission’s endorsement of the Swedish “personal vote” system described above.

These questions will be part of the public debate that is to focus on the hearings of a commission of the National Assembly in the fall. The drafting of a final Bill and its adoption, if all goes as planned, could occur before the end of the December session. Incidentally, this would coincide with the tabling of the BC Citizens’ Assembly Report. Of Quebec’s three main parties, the ADQ, as the most obvious immediate beneficiary, will be certain to support the Bill. If the ADQ’s votes in 2003 had been proportionally translated into seats, that almost invisible party of today would now have 20 or 21 deputies (rather than the current 4) and, hence, official party status. The left-wing Union des Forces Progressistes (UFP) may benefit as well: it could receive sufficient support to elect one MNA (in east- end Montreal) – even under the single-ballot set-up and the absence of lists, both aspects it vehemently opposes. The same could be said for the Green Party and perhaps also for an anglo-rights party.

As for the two major parties, the Liberals’ stand to gain from reducing what Massicotte (1995) calls the “gerrymander linguistique” that has had the PLQ wast- ing many thousands of votes in the nonfrancophone majority districts of Montreal. Under the current system, Massicotte estimates that the PLQ must receive at least 5 percent more popular votes to win as many seats as the PQ. Yet the extent to which reform will change things depends on the size and location of the regional districts. Overall, larger districts shrink the gerrymander (i.e., help the PLQ) better than do the smaller ones. And it is here that the PQ’s strategy of keeping out of the debate – using the flimsy pretext of insufficient public con- sultation, even after 22 years of public debate leading up to the Estates General – might backfire. By insisting that true democracy requires respect for the relatively small electoral regions that reflect the profound regional identities of Quebecers, the PQ could maintain some of its advantage in nationalist parts of Quebec.25

A major factor in the Péquistes’ reticence to endorse voting-system reform is their fear of its effect on the sovereignty option. Clearly, it will be harder for sovereignists to form majority governments with only 40 to 45 percent support for parties backing sovereignty. But if and when the majority of Quebecers are ready to consider sovereignty, the chances of their being able to take advantage of the situation under the envisaged system could be enhanced, depending, of course, on the parties’ ability to build and maintain a pro-sovereignty coalition. Although the “pur et dur” nationalists in the PQ might split from the party’s mainstream under a proportional electoral system, that does not preclude a coali- tion government composed of these two factions and supported by both the UFP and the Greens. It is worth noting that the 2003 Scottish election outcome showed that the MMP system can favour the independence cause. Both the Labour and the Scottish National Party (SNP) lost seats, the main winners being the smaller parties with 17 (of 129) seats; of these, 7 went to the Greens and 6 to the Scottish Socialist Party, both of which are pro-independence like the SNP. As a result, the total pro-independence grouping grew significantly to 41 MSPs, including one Independent (Jeffery 2004).

What will the PQ do once the National Assembly committee takes up the Bill and it becomes increasingly uncomfortable to duck the issue? Perhaps the PQ deputies hope that Liberal colleagues fond of the system that elected them will block the proposal. This is unlikely, however, especially now that the PLQ is low in the polls and needs any advantage electoral reform can bring. Indeed, though still a long shot, this factor just might influence the government to try to advance implementa- tion so the new system is in place for the next election (probably in 2007).

If opponents of change in the PQ envisage a scenario in which they win power and repeal the law, they are likely to be disappointed. Clearly, the context is quite different from 20 years ago, when Lévesque’s plan fell short. Whereas Quebec was acting very much alone in 1983-84, it is now part of a wider move- ment that has had success in New Zealand and the British Isles and has become firmly planted on Canadian shores – with parallel initiatives taking place in Victoria, Charlottetown, Toronto, Fredericton and perhaps Ottawa. While we cannot predict the speed of change, we can reasonably conclude that once change has begun there will be no going back.

Aimer, Peter. 1999. “From Westminster Plurality to Continental Proportionality: Electoral System Change in New Zealand.” In Making Every Vote Count: Reassessing Canada’s Electoral System, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Bird, Karen. 2004. “Lessons from France: Would Quotas and a New Electoral System Improve Women’s Representation in Canada?” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Cousins, John A. 2004. “Prince Edward Island’s Cautious Path toward Electoral Reform.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Doody, Brian, and Henry Milner. 2004. “Twenty Years after René Lévesque Failed to Change the Electoral System Quebec May Be Ready to Act.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Faure, Murray, and Albert Vente. 2004. “Electoral Reform in South Africa: An Electoral System for the Twenty-First Century.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

Franklin, Mark. 2003. “The Generational Basis of Turnout Decline in Established Democracies.” Paper presented at the World Congress of the International Political Science Association, July 2003, Durban, South Africa.

––. 2004. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jansen, Harold J., and Alan Siaroff. 2004. “Regionalism and Party Systems: Evaluating Proposals to Reform Canada’s Electoral System.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

Jeffery, Charlie. 2004. “Voting on Devolution: Recent Elections in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.” Inroads 15, Summer.

Law Commission of Canada. 2004. Voting Counts: Electoral Reform for Canada. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services. https://www.lcc.gc.ca

Leuprecht, Christian, and Chris McCreery. 2000. “When Fraud Comes of Age: Libations and Legitimacy in Canadian Electioneering.” Public Integrity 4, no 4: 273-289.

Lijphart, Arend. 1999. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performances in Thirty-six Countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lynch, Peter. 2004. “Making Every Vote Count in Scotland: Devolution and Electoral Reform.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Massicotte, Louis. 1995. “Eclipse et retour du gerrymander linguistique québécois.” In L’Espace Québécois, edited by Alain-G. Gagnon and Alain Noël. Montreal: Editions Québec Amérique.

––. 2003. “To Create or to Copy? Electoral Systems in the German Länder.” German Politics 12, no. 1.

––. 2004. “That Bleak? Fathoming the Consequences of Proportional Representation in Canada.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Milner, Henry, ed. 2004. Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Nagel, Jack H. 1999. “The Defects of its Virtues: New Zealand’s Experience with MMP.” In Making Every Vote Count: Reassessing Canada’s Electoral System, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

––. 2004. “Stormy Passage to a Safe Harbour: Proportional Representation in New Zealand.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Pammett, Jon, and Larry Leduc. 2003. “Explaining the Turnout Decline in Canadian Federal Elections: A New Survey of Non-voters.” Ottawa: Elections Canada.

Pilon, Dennis. 2004. “The Uncertain Path of Democratic Renewal in Ontario.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Plutzer, Eric. 2002. “Becoming a Habitual Voter: Inertia, Resources, and Growth in Young Adulthood.” American Political Science Review 96: 41-56.

Richie, Robert, and Steven Hill. 2004. “The Fair Election Movement in the United States: What It Has Done and Why It Is Needed.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and Its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Ruff, Norman J. 2004. “ Electoral Reform and Deliberative Democracy: The British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly.” In Steps to Making Every Vote Count: Canada and its Provinces in Comparative Context, edited by Henry Milner. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

FPTP: First past the post

Majoritarian system: This voting system involves a single member district (France and Australia) and either a preferential-ballot (Australia) or a two-ballot system (France)

Mixed system: A system that is partially FPTP and partially PR without substantial compensation

MMP: Mixed-member proportional representation

PR: Proportional representation

STV: Single transferable vote

For immediate distribution – Thursday, September 9, 2004

Montreal – Canadian provinces could learn important lessons from Scotland and New Zealand, two communities that have adopted mixed proportional systems, says Henry Milner. The Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP.org) today released a study by Henry Milner entitled “First Past the Post? Progress Report on Electoral Reform Initiatives in Canadian Provinces.”

The author, a Strengthening Canadian Democracy visiting fellow at the IRPP, looks at current electoral reform initiatives undertaken in five Canadian provinces. He concludes that two provinces are leading the way, namely Quebec and British Columbia. But, his analysis, which identifies weaknesses and innovations in the Quebec proposal, reveals that the province is at the forefront of reform based on the legislation it will table this fall.

Milner says that the provinces engaged in this electoral reform debate wish to devise a model of proportional representation that ensures a continued role for directly elected MLAs or MPPs representing specific geographic boundaries. And, he is clear in arguing that a mixed member proportional representation system (MMP) would ensure such a role.

The study looks at recent developments in Scotland and New Zealand, two communities with Westminster-style parliaments similar in size to the larger Canadian provinces, which have adopted MMP models to supplant their single-member electoral systems.

The study finds, that on the whole, adopting an MMP system redresses the main pathology manifested under the current first-past-the-post system, namely the distortion in popular vote to seat conversions. This often cited problem contributes to other phenomena raised by advocates for reform. For instance, the “loser wins” scenario in which parties that garner most votes do not necessarily win the corresponding seats and hyperpolarization whereby no room is left for parties representing the middle group of electors.

Drawing from the lessons learnt under the Scotland and New Zealand models, Milner says we can devise guidelines for applying the MMP system to Canada in order to minimize divergences from proportionality and yet enhance the functioning of the system, such as:

“First Past the Post? Progress Report on Electoral Reform Initiatives in Canadian Provinces” is the latest Policy Matters study to be released as part of the Strengthening Canadian Democracy series. It is now available on-line in Adobe (.pdf) format on the Institute’s Web site (www.irpp.org).

The media is cordially invited to attend a French-language conference sponsored by the Mouvement démocratie et citoyenneté du Québec on September 15, 2004 at 7:00 p.m. at which Dr. Milner will be discussing the results of this study. The free event will be held in room D-R200 of the Pavillon Athanase-David of the Université du Québec à Montréal (1420 Saint-Denis Street in Montreal).

– 30 –

For more information or to request an interview, please contact the IRPP.

To receive IRPP media advisories and news releases via e-mail, please subscribe to the IRPP e-distribution service by visiting the IRPP Web site (www.irpp.org).

Founded in 1972, the IRPP is an independent, national, nonprofit organization based in Montreal.